insights2021

Incorporating community-based and action-oriented advocacy methods into the SPHR conference

Harvesting our learning from the conference

Toward methods that center lived experiences in human rights practice

Toward a new advocacy paradigm

Part 3 part 6 Part 2 part 5 Part 4

Reimaging old spaces as new Reshaping human rights movement-making Part 1

CONTENTS Table of

INTRODUCTION

In this 2021 Insights, we share the learning and action that emerged from the Social Practice of Human Rights Conference (SPHR) 2021 - Between Peril and Potential. A signature event for the Human Rights Center, the 2021 conference responded to the multiple and overlapping crises we're experiencing with fierce urgency. SPHR engages biennially at the intersection of research and advocacy with a view to understanding better what it takes to make human rights a reality. Since 2013, this forum has brought together academics and practitioners to address critical issues through self-reflection, constructive critique and solidarity.

At SPHR21, we convened to tackle the question of what human rights advocacy looks like in the wake of the global pandemic. The pandemic altered the agenda for this SPHR in multiple ways:

First, the pandemic experience broke down artificial boundaries in society and revealed more clearly the inequitable systems that remain intact, heightening the need for structural change. While collaboration and mobilization have launched social movements for justice, long-standing inequalities have been exacerbated, leading to further injury and marginalization. Moreover, antirights movements, undemocratic norms and populist politics have gained considerable traction in the pandemic era.

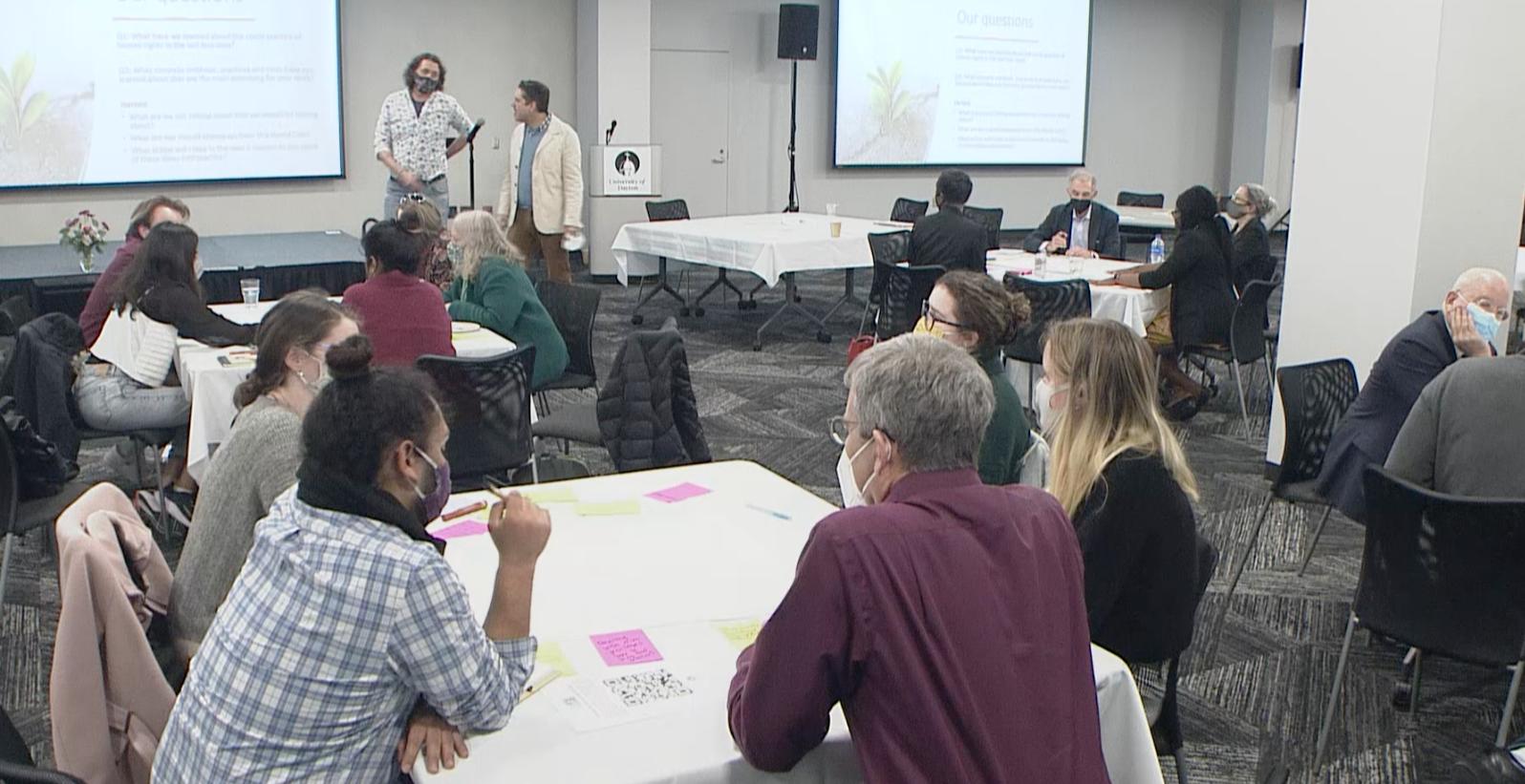

Second, the pandemic centered connections between local and global human rights practice. For this reason, SPHR21 spotlighted local voices, organizations and coalitions working on the issues that we are jointly addressing. We further embraced the call for innovation issued at SPHR19 by expanding our interactive and forward-thinking workshops focusing on local as well as global challenges. We integrated action research methods, including the World Cafe, reflections collected on Padlet and creative documentation of key conversations, into the forum.

Third, the format of SPHR was altered to reflect the times. We introduced a hybrid set-up which seized the potential of virtual engagement to harness insights from around the globe, while grounding our conversations in interpersonal and face-to-face dynamics. For the first time, all keynotes, plenaries, and panels are available to view on the SPHR21 website. This was also an investment in the future of the forum, based on our longstanding commitment to environmental and economic sustainability.

Finally, 2021 Insights captures our commitment to making SPHR a dynamic platform for continuous learning and collaborative action. We sought to innovate this year by analyzing and extracting the data collected and perspectives shared throughout SPHR21 in order to gain critical insights into current trends in human rights advocacy. This is a key part of our aim to progressively transform SPHR into an evidence-based learning process that, in every way, reflects our values.

We are living at a time when illiberal movements, antidemocratic norms, and reactionary politics are leading to a regression in human rights protections everywhere. As advocates and organizations face this current moment, we hope that the initial attempt to harness and communicate SPHR insights is a valuable contribution to our vision of “a diverse community developing transformational and sustainable social practices that address systemic injustice and advance peace, dignity and human rights.”

1

At SPHR21, we considered whether current human rights methods and strategies are comprehensive, deep, and bold enough to meet this moment and leverage it for increased justice and dignity.

INCORPORATING

CONFERENCE part 1

COMMUNITY-BASED AND ACTION-ORIENTED ADVOCACY METHODS INTO THE

SPHR

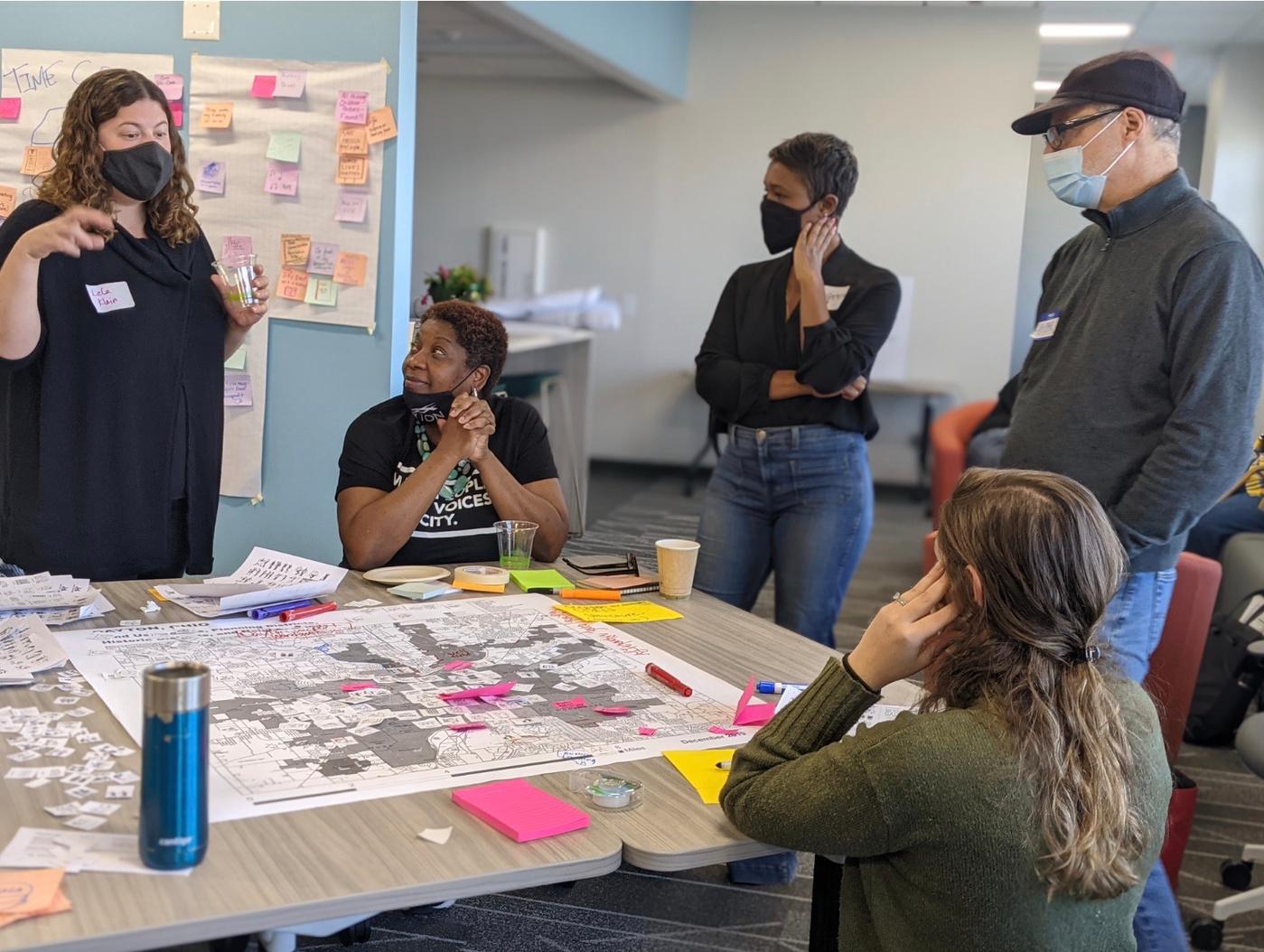

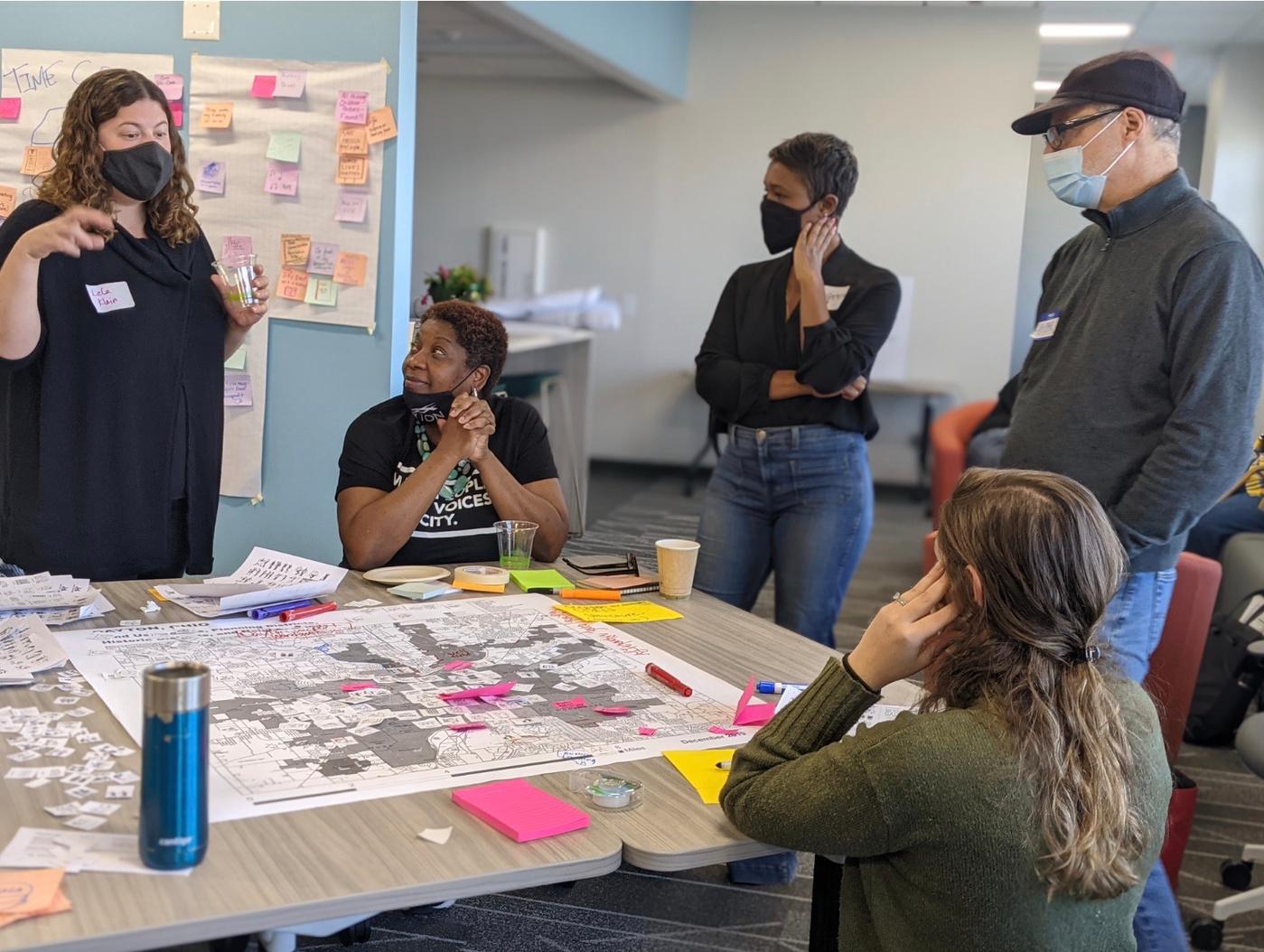

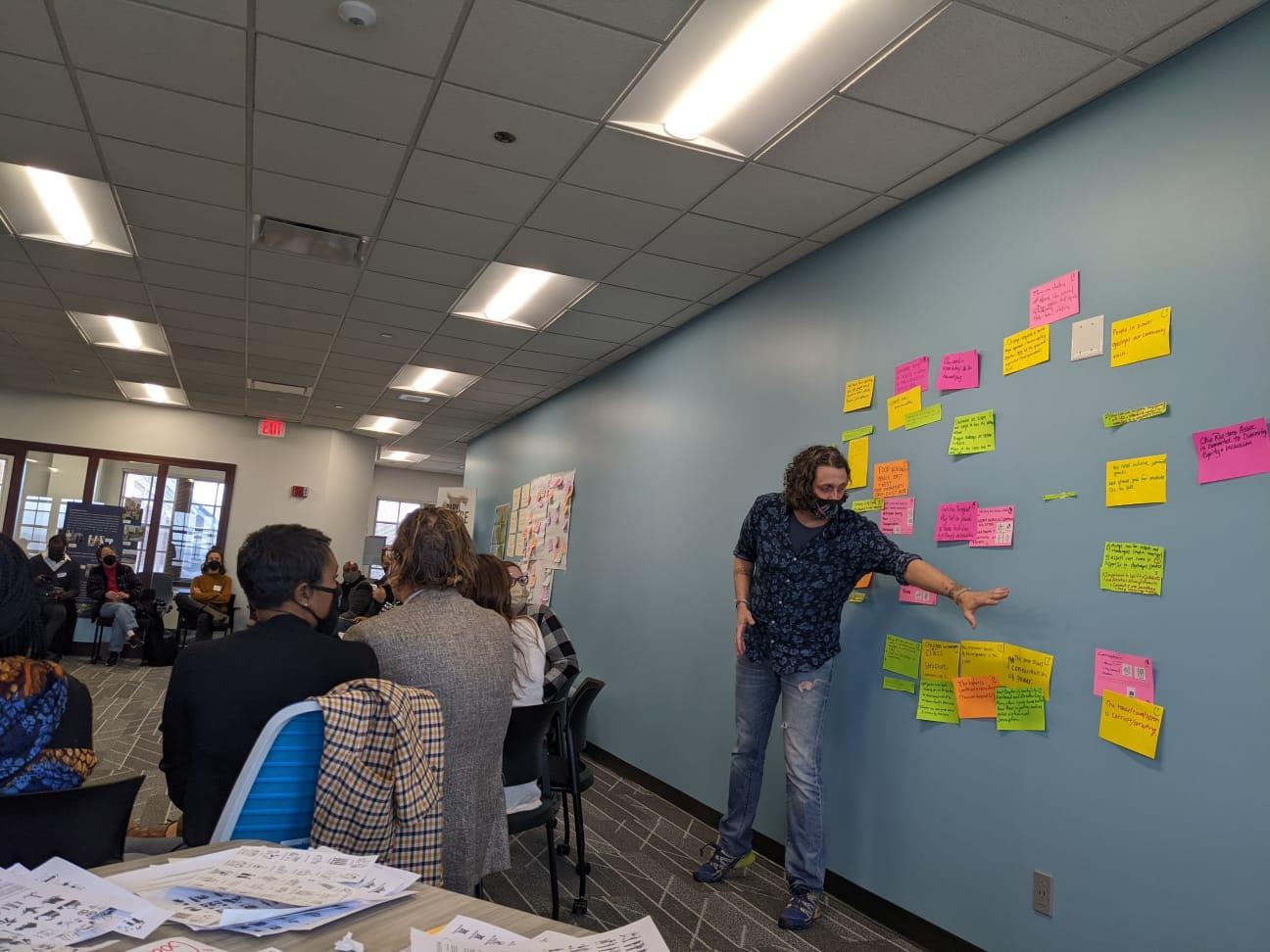

On a bright and brisk December morning in Dayton, Ohio, over fifty local activists shared half of their Saturday with one another to begin a collective process. The excitement of the morning reflected the fact that, for many participants, this workshop was their first inperson gathering in months if not longer, taking place at a moment in the global pandemic when people were willing to meet together in physical space.

As a city, Dayton is not without its problems, which range from food insecurity and maternal mortality to police surveillance and government transparency and, in a city like ours, there is a spectrum of activity long in motion to respond to these challenges. There is also a history of racial and other forms of discrimination, such as redlining in the housing and real estate business, that has substantially impacted the community today. The Covid-19 pandemic has exacerbated these challenges and brought key dimensions to political light, such as evictions, homelessness and unequal access to financial opportunities.

Despite how interconnected these issues are, individuals and groups put their heads down and do work, often without knowledge of what others are working on or how the issues are connected. In hosting this Saturday workshop as part of the 2021 Social Practice of Human Rights (SPHR) Conference, the UD Human Rights Center aimed to hold space for people from across our region to sit down together, learn about each other’s efforts, identify areas of overlap or gaps, and start to build a more unified way forward.

When we awoke on this particular bright and brisk morning, we had just concluded the traditional conference consisting of two-plus days of keynote addresses, plenary events, and research sessions. Building on the fourth SPHR conference, where we expanded the conference space with design

"THAT WE WORK IN SILOS IS NOT A SHOCK." JOEL PRUCE

2

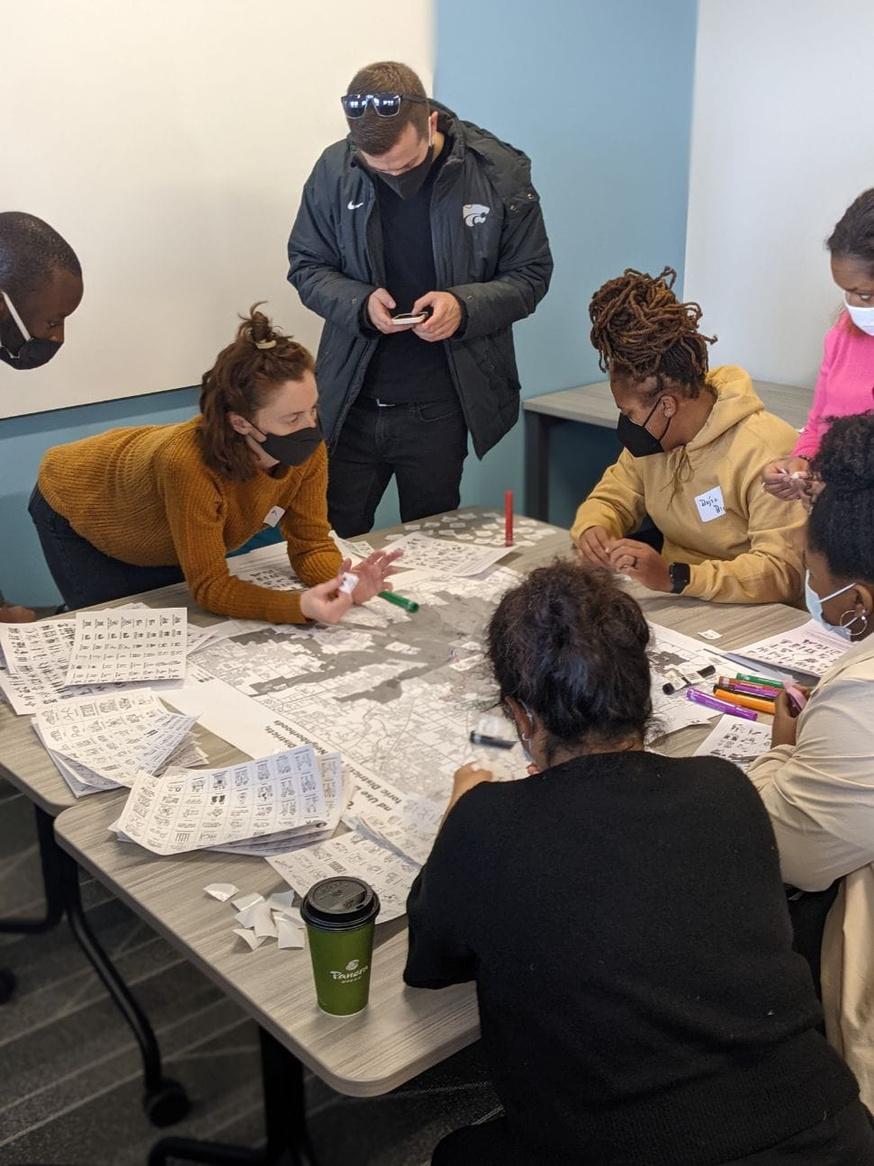

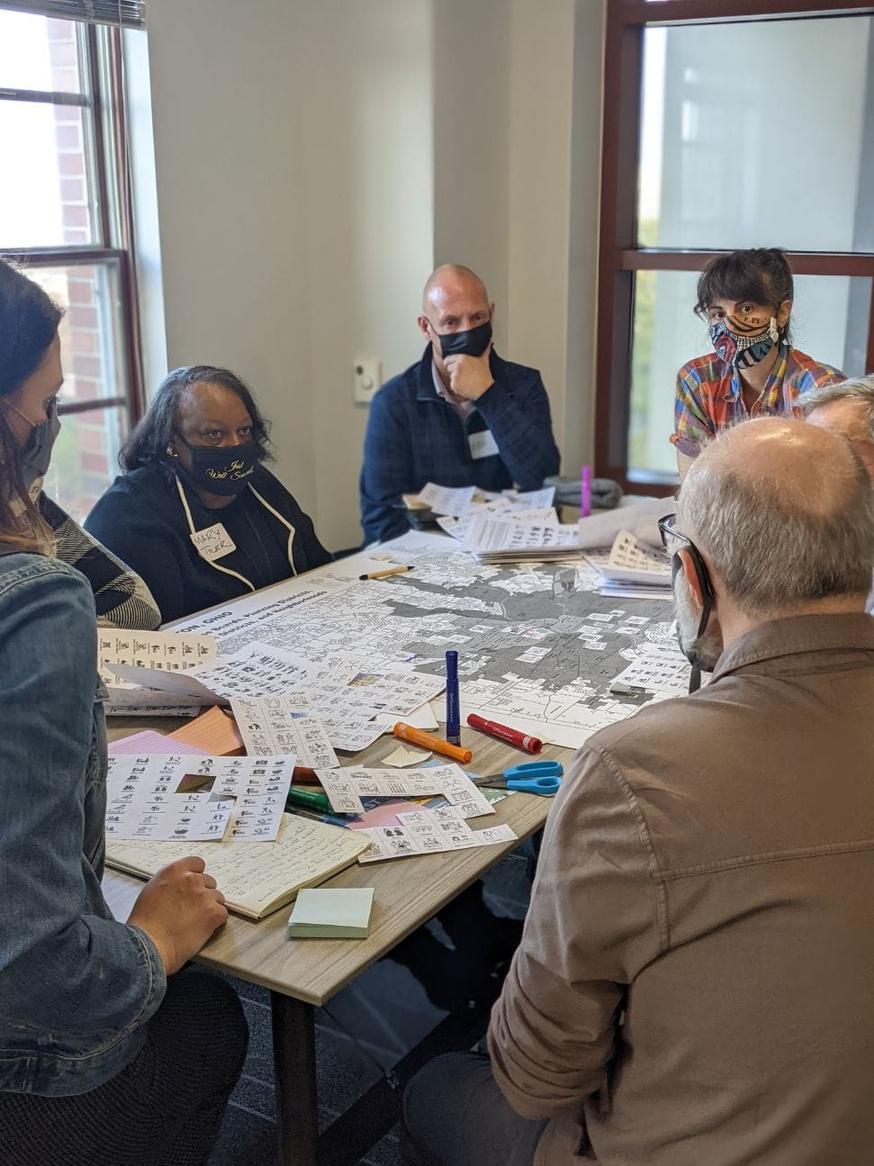

Our Executive Advisory Committee member, Rafael Hoetmer and colleague Alfredo Ortiz helped us design the workshop, which we called the “Dayton Human Rights Dialogue.” Through a dynamic social mapping exercise, participants shared their knowledge of our region by identifying issues, assets, and opportunities. With sharpies, highlighters, post-its, stickers, and scissors, the groups located sore spots and zones of hope on a map of the city. In the time since then, we’ve been working to aggregate all that we learned that morning and are currently creating an actual map to share with those who were in attendance and more widely as a document, a snapshot, of our city in this moment, as seen through the eyes of those who experience it, live in it, and work every day to make it a more equitable and just place.

But, these kinds of gatherings have happened before and occur all the time in cities like ours. That we work in silos is not a shock to anyone. That we have enormous challenges is also not a surprise. Coming together is a critical first step but it cannot be the only step. As a Center, we are conscious of the need to support an ongoing community-based process of collective action through which these advocates and others can work together with more holistic approaches.

With that in mind, the workshop provided a space to learn about what it would mean to declare Dayton as a “human rights city.” We were fortunate to be joined in person by Jackie Smith from Pittsburgh, Rob Robinson from New York City, and Crista Noel from Chicago—all of whom in a range of powerful ways utilize the international human rights framework in local activism. They attest to the capacity to organize and mobilize communities around a global language for dignity that broadens the imagination of ordinary people and provides a vocabulary with which to formulate their experiences of discrimination or violence. But, more than just words, human rights can also create tangible mechanisms for monitoring state behavior, making claims against governments, and seeking remedies. Human rights cities around the world have built resourced institutions in their municipalities that function to provide transparent processes for community members to articulate grievances and hold their public officials accountable. It’s inspiring, of course, and we know that feeling of leaving a gathering energized to get back to do the work…and then there remains the task of actually doing the work.

Since December, the effort to build a human rights city in Dayton has begun to gain momentum and we will remain engaged in this crucial initiative. The social practice of human rights, as a concept and not just a conference, demands that we come together often to devise ways to dedicate our varied skills and knowledge to put in service of rights and dignity We saw this working on that Saturday morning in our own city and look forward to future opportunities for community building through ideas in action.

3

HARVESTING OUR LEARNING FROM THE CONFERENCE part 2

At the heart of this process is an intention to utilize methods that reinforce the human rights values we espouse. We wanted to be able to learn from SPHR21 in a new and innovative way.

World Cafe

The World Café methodology is a simple, effective, and flexible format for hosting large group dialogue to reflect collectively. Our Executive Advisory Committee member, Rafael Hoetmer, and colleague, Alfredo Ortiz Aragón hosted the World Café. Their brief

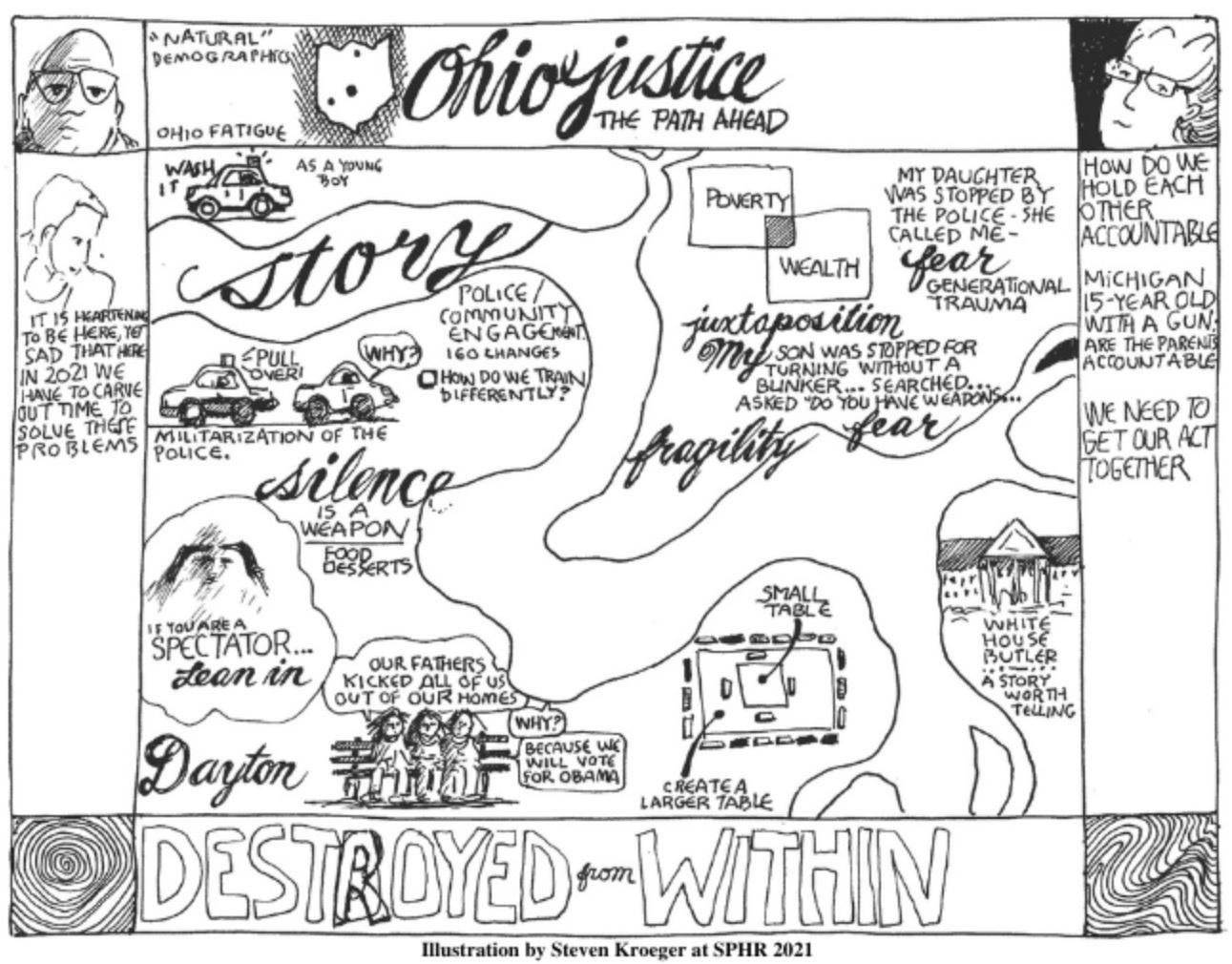

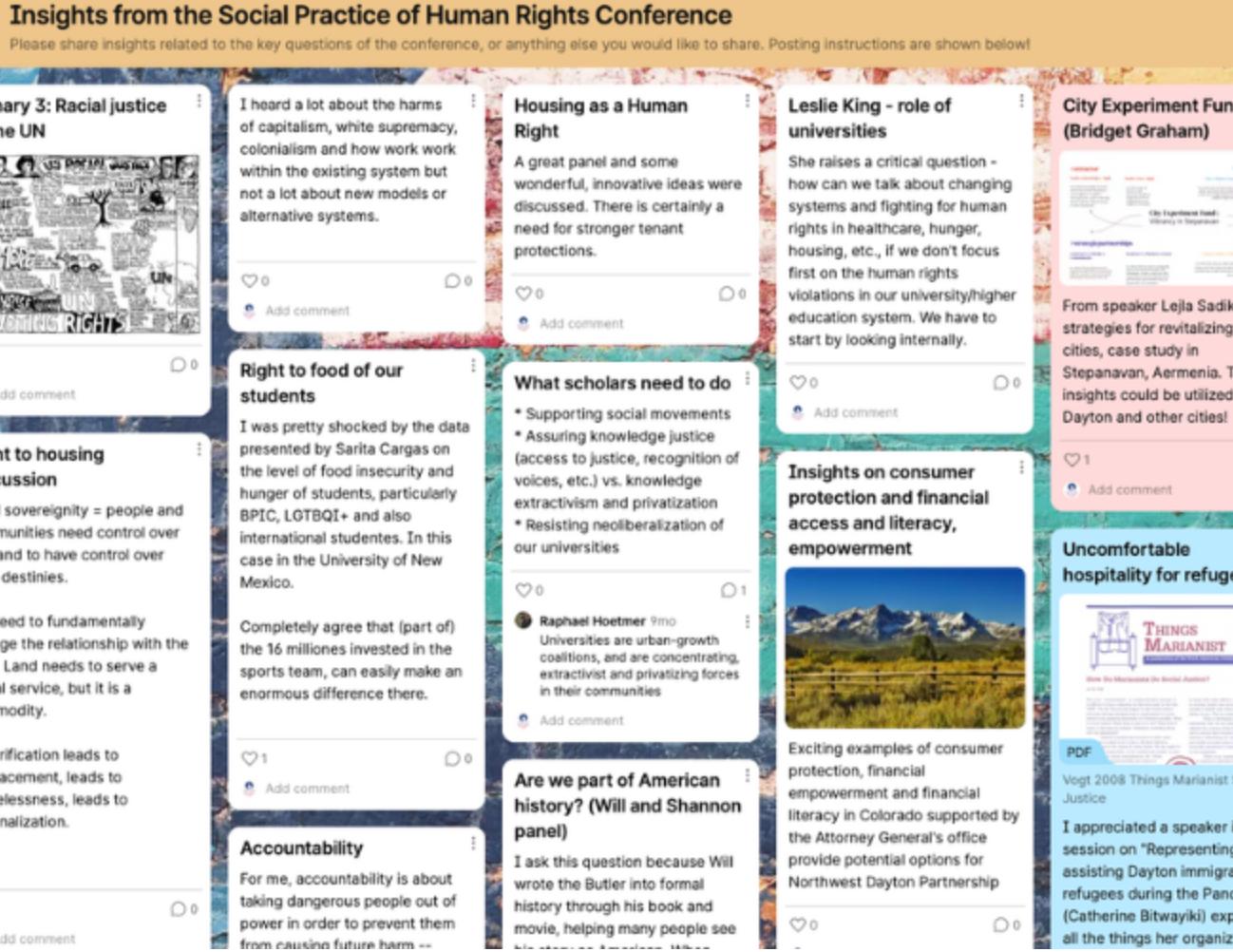

SPHR21 provided a space for compelling dialogue and conversations related to the conference theme in a hybrid format. For the first time, this year we also created moments to collectively interpret the ideas and knowledge being shared through action research methods, including using the on-line audience response system Padlet and hosting a World Café As another innovation, we also engaged Stephen Kroeger, a creative documentor, who simultaneously documented through drawing the key interactions and moments of our SPHR plenary conversations. The conference Padlet allowed us to capture immediate insights on peoples’ reactions to the various keynotes, plenaries and panels, while the World Café provided a space for collective reflection at the closing of the event. These methods structured our learning approach and enabled us to collect data that we synthesized using grounded theory into major takeaways.

Here we explain how we went from capturing reflections at the conference to learning from the information we collected, and distilling it all into new insights.

presentation covered the seven design principles of the dialogue: (1) setting the context: the purpose, the parameters of meeting, the themes or discussion questions, and defining the participants; (2) creating hospitable space or a welcoming physical setup of the meeting; (3) exploring questions that matter; (4) encouraging everyone’s contribution; (5) connecting diverse perspectives through “cross-pollination” of ideas, allowing participants to meet and engage with new people, actively linking the essence of one’s own discoveries to those of other participants; (6) listening together for patterns and insights; and (7) sharing, or gathering, collective discoveries.

Our World Café began on the last evening of SPHR2021, with two twenty-minute rounds of conversation. After twenty minutes, each group member moved to a different new table, leaving one person to serve as the “table host” for the next round. Round one of conversation focused on the question: What have we learned about the social practice of human rights in

4

Using grounded theory

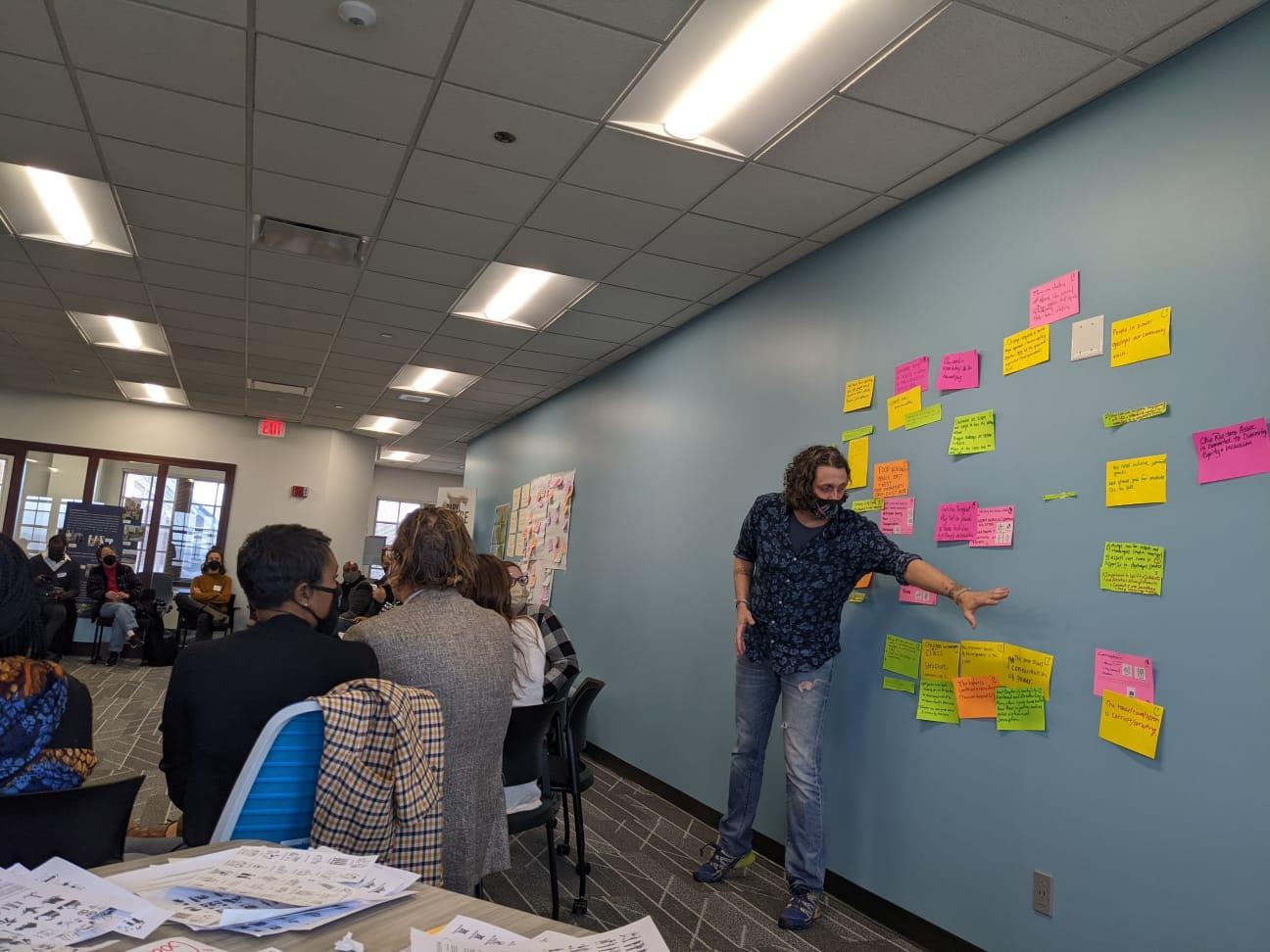

the last two days?, and round two responded to the question “What concrete methods, practices and tools have you learned about that are the most promising for your work?” Once the two discussion rounds ceased, the entire group met again in plenary. During the harvest period, group members summarized the findings from their table, focused on what we were not talking about, overall takeaways and how to put ideas into practice. In addition to discussions doodled on flip chart papers, or recorded on index cards after each round, we video recorded the final plenary discussion. After the data collection processes, a dedicated team got to work analyzing the ideas generated. 1

Grounded theory is a way of developing theory that is grounded in and derived from experience. Specifically, the constructivist grounded theory approach involves an inductive analysis of data using various techniques, including coding, categorizing, memoing, mind mapping and dialogue. The grounded theory approach enabled us to deepen our inquiry and analysis of the conference. As Kathy Charmaz encouraged, we “let the process emerge during the data analysis stage”. This process resulted in collaborative learning and collective reflection.

2

With the data mined using the World Cafe and Padlet during the conference, a two member team from the HRC worked individually to code the posts on the Padlet to describe or interpret the various inputs from a human rights and social practice of human rights perspectives, respectively. From the human rights perspective or “the what”, we used codes like “#racial injustice in institutions” and “#role of universities.” From a social practice of human rights perspective or “the how”, our coding used gerunds (“-ing” words), in order to place action at the forefront. For example, we used codes such as “#organizing for grassroots activism” and “#training students to document abuses”, each of these referring to ideas recorded as posts from participants in the conference. For instance, during the session on the human right to housing, a participant posted about how

the speakers active in various locations exchanged fresh and clever approaches each had taken to their work, which we coded as “#sharing innovations and ideas,” and this became a code we used elsewhere. Going beyond a summary of what people were reflecting on at the moment during the conference, we analyzed the implications of their inputs for the social practice of human rights or, in other words, defining the action that shapes or supports the data.

1

In the next stage, we wrote memos by assessing the initial comments we made while coding in terms of the salient points for the HRC’s work, in order to interact more extensively with the data. We chose at least five of the most important posts that resonated with us from the memo, based on at least two relevant codes we gave those posts in order to show evidence that supported our conclusion. These posts were integrated into two individual cluster concept maps that drew out the main insights and their connections to the original Padlet posts. Being able to trace our findings back to their origins speaks to “recoverability,” or the intentional practice of leaving bread crumbs as clues that provide audiences the option to engage with the inquiry itself by tracing back how the researchers arrived at their findings. Through a collaborative process, we then combined the two individual maps into one consolidated map from the Padlet.

We also used grounded theory to assess data from the World Café from flip charts, index cards, post-it notes and the recording. Transcriptions of the recordings of the conversations allowed for tracing the context in which statements were made and feedback given during the plenary. We combined these into a map of emerging concepts for each phase of the World Cafe. Through several meetings and iterations by the team, we created a consolidated map, informing our key takeaways from the conference. We were able to identify connections with the data and develop answers to the question of what we have learned about SPHR concepts, methods, practices, and tools.

3

5 5

4

Creating space for reflection and dialogue

Integrating these methods into SPHR2021 resulted in dialogue initiation and served as effective and practical communications tools to generate insights from the conference beyond the structured sessions of keynotes, plenaries and roundtable. This also created an opportunity for sharing stories as participants were able to engage on a more personal level using these methods.

More importantly, these methods which engaged scholars and practitioners highlighted the importance of dialogue and communicative spaces for reflection and critique, resulting in new insights and knowledge on the social practice of human rights.

We’ve all had the experience of sharing brilliant and fruitful conversations in class, at a conference, or at the coffee shop. Action research methods, as we used during this SPHR, seek to ensure that the knowledge production and understanding that occur in these spaces don’t just stay in these spaces. Instead, if we’re able to implement thoughtful practices for reflection, collection, and learning, we can preserve brilliance and put it to work in the service of human rights praxis.

Sources:

1 Charmaz, K. (2014), Grounded Theory in Global Perspective: Reviews by International Researchers.

2 Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide through Qualitative Analysis. London: Sage Publications.

3 Charmaz, K. (2003). Grounded theory: Objectivist and constructivist methods. In N. K. Denzin, & Y. S. Lincoln

Strategies for qualitative inquiry (2nd ed., pp. 249-291). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

4 Checkland, P., & Holwell, S. E. (1998). Action research: its nature and validity. Systemic Practice and Action Research, 11(1), 9-21.

5 Checkland, P., & Poulter, J. (2010). Soft systems methodology. In M. Reynolds & S. Holwell (Eds.), Systems approaches to 10 SAGE Open managing change: A practical guide (pp. 191-242). New York, NY: Springer.

London: Sage Publications.

(Eds.),

6

TOWARD METHODS THAT CENTER LIVED EXPERIENCES IN HUMAN RIGHTS PRACTICE part 3

"NEW TIMES CALL FOR NEWMETHODS.” ANN HUDOCK

This quote reminds us of the times we find ourselves in: a world where anti-rights movements, undemocratic norms, illiberalism and populist politics have gained considerable traction and exacerbated long-standing inequalities, leading to further injury of marginalized communities and regression in human rights protections.

While an aim of SPHR is to bridge the gap between scholars and practitioners, in the 2021 convening there was a recognition of the continuing divide between the academic community and practitioners, categorization of people into expert and non-expert actors, and a continuing binary of global versus local in the human rights movement.

During the session on Utilizing international human rights frameworks and treaties to advocate in local communities, for example, Michael Goodhart noted that the binary between global and local does not necessarily describe the real world. He stressed that the global is not “some place out there somewhere” but a set of processes that affects us wherever we are.

In order to transcend these divides, human rights proponents need to center the concerns and worldviews of those directly impacted by human rights, wherever

they are, by building relations and creating spaces that help co-produce knowledge and turn that knowledge into action collaboratively. We highlight four ways of doing so that emerged from SPHR21 here:

Community-based, action-oriented research

"Any human interaction that we participate in can be a source of knowledge production, a method of research if we are willing to reflect on it ” Padlet reflection

Collaborative research practices focus on research with communities instead of research about them. In human rights terms, the traditional split between the “researcher” and “subjects”, and the assumption of researcher “objectivity” is problematic and harmful. These conventions assume a fundamental separation reinforced by alienating research methods and reified by scholars who report on communities who hold the knowledge and expertise of which researchers see themselves as existing separate from their own lives.

7

As noted by Nicholas Sherwood, in human rights research, we must “stand in solidarity with instead of conducting research on” impacted communities. Relationships of trust and mutuality are key to incorporate contextualized and participatory knowledge of impacted groups. For example, the perspectives of communities in focus can be integrated into research design and research processes and outcomes can be open to critique by those communities.

The methods we utilize in conducting research and producing knowledge should also serve to change oppressive systems and injustice. “Research for and through action,” as Alfredo Ortiz Aragón so aptly describes it. From a social practice perspective, there are many spaces that provide opportunities for more equitable knowledge production and collaboration and collective action, including higher education, open technology, community organizing and art.

Dialogic methods

SPHR21 showed us that dialogic methods, such as convening and facilitating dialogues, can promote greater and more equal participation in knowledge generation and orient participants towards social transformation. As we experienced with the World Café, these methods expand our toolbox for reflection and action, working both through and for human rights values. By sharing experiences across diverse perspectives, those who engage in dialogue learn more about themselves and the world.

While not traditionally used in human rights advocacy spaces, dialogic methods demand that we ask better questions and engage in active listening with humility, particularly to those who have opposing views on human rights issues. They create avenues for people to come to the practice of human rights on their own terms and based on their own experiences. These methods require an openness to communication and really listening to others, letting all people be heard to share their stories.

In response to the practical question, how do we ensure dialogic methods during the SPHR conference?

Participants proposed organizing dialogic spaces more intentionally and being more experiential by having the World Café style throughout the conference to avoid oversaturation of formal panels and to promote less “academic preaching and more pragmatism.”

Story-doing

“Storytelling [is] an essential approach/method […] to develop, sharpen and spread. [But] how do we promote and protect storytelling without draining or exploiting those whose stories are most needed (or at least we assume those that are most needed)?”- Padlet

reflection

During the plenary Ohio, justice, and the path ahead, Shannon Isom and Wil Haygood exemplified the power of story-telling to speak truth to power and provide a personal means of justice and recognition. For example, Haygood’s award-winning book and film about White House Black butler, Eugene Allen, emerged from his own personal experience as a Black journalist and resulted in changing popular culture perceptions of whose experiences are acknowledged as important in American history.

8

But storytelling also raises concerns for human rights actors when it may impose emotional burdens and even exploit the storytellers. And simply telling and sharing stories may be inadequate on their own. For example, to “overcome systemic racism,” minority stories need to become part of mainstream history and shape discourse. Operationalizing stories in and through coordinated campaigns and movement building efforts can advance counter-narratives and truth-telling to weaken the discursive power of states and pernicious non-state actors, if experience and voice can be deployed intentionally and strategically; or what Alfredo Ortiz Aragón refers to as “moving from story-telling to story-doing.”

New tech & citizen science

The reduction of barriers to developing critical advocacy tools grounded in science and technology means that people can use and shape these tools and apply them to the issues that concern and impact them. At SPHR21, we explored examples of the innovative use of citizen science, cryptocurrencies, data analytics, search algorithms, blockchain, and geospatial technologies for advocacy across a range of issues, such as corporate accountability, forced disappearances, genocide, trafficking, refugees and protecting human rights defenders. For instance, examples of indigenous community science monitoring of pollution caused by mining or oil extraction in Peru was shared in the session, The climate crisis, sustainable development and new frontiers. While we acknowledge that these tools can be used to negatively impact human rights, the session Emergence of new human rights methods and tactics showed that the space for those impacted by human rights to shape and develop new science and technological methods for advocacy continues to grow and has become even more essential in the pandemic era. However, education to use these tools in human rights spaces is also required. As highlighted in the session, Developing a practice in remote sensing for next generation human rights researchers, there is an urgent need to expand the

community of practitioners who have training in the appropriate and responsible use of geospatial technologies for human rights research and documentation.

"...HOWEVER, EDUCATION TO USE THESE TOOLS IN HUMAN RIGHTS SPACES IS ALSO REQUIRED."

In sum, we discovered from this SPHR that methods that center lived experiences, amplify the voices of the most impacted and democratize knowledge generation are still underutilized. We identified four ways to redefine whose knowledge, needs, and methods are reflected in our models for generating and sharing insight and engaging in the social practice of human rights.

9

part 4RESHAPING HUMAN RIGHTS MOVEMENT-MAKING

At SPHR21, we sought to answer the question of how different movements, organizations and activists — who seek justice and dignity from various lenses, identities, and approaches — interrelate in this current era. In exploring this, we found that human rights advocacy is more impactful today when it is grounded in critical, intersectional and decolonial feminist approaches.

In this way, our actions are better anchored and equipped to directly address the root causes of structural violence and oppression.

Varying methods and tactics of campaigning

strategically

In the era of increasingly corrupt and authoritarian governance, non-violent civil resistance movements have been at the forefront of human rights struggles in the U.S. and many countries around the world. Through keynotes, plenaries and roundtables, we explored a range of these movements and the factors that make for successful campaigns. In their keynote, Erica Chenoweth explained that the ability to vary methods throughout the course of the civil resistance movement is a key factor in the movement’s success. These methods include, for example, boycotts, building parallel institutions, protests and other forms of noncooperation. They also noted that employing varying methods effectively requires high levels of strategic leadership which can be difficult to maintain in today’s social movements. The plenary on Civil resistance & social movements of 2020 showcased movements achieving various levels of success in place s like Belarus, India, Chile

and Sudan. A challenge is coordinating and sequencing various methods over time which requires strategic levels of community organizing and coalition building to maximize participation of people across a range of sectors in society. The extent to which movements draw in a diverse cross section of society, including those who are a part of repressive institutions, is critical to success. Human rights advocacy must more fully embrace the strategic use of varying methods and tactics of advocacy to build more effective campaigns.

Feminist leadership

In the current context where major regressions are being taking place across human rights protections, feminist leadership and lenses emerged as integral to understanding and defining human rights challenges. They also are essential to identifying effective responses across many issues, such as corporate accountability, human rights education, and civil resistance and democratic renewal. During the plenary on Civil resistance and Social Movements of 2020, for example, Margarita Maira pointed out how Chile had successfully established the first ever gender balanced constitutional convention because of the effectiveness of the feminist movement in organizing for and through the popular democracy uprising. As noted by another person in the Padlet, “feminist movement did its job! Tireless.”

“Are there any human rights issues that do not connect back to the politics of masculinist restoration?”

Natalie Hudson

10

In the session, Corporate accountability in transitional justice: reflections on an ongoing social lab, the question was posed, “What happens when transitional justice becomes feminist?” The work of the social lab is not simply about women-led leadership or the fact that women carry the disproportionate burden of corporate violations in conflict affected societies, but also about a “relational ethos” that is built, inspired by design logic, which creates a different space of mutuality that allows for the new strategies to emerge.

Also in the roundtable on Feminist Leadership, GenderBased Pedagogy and Educating Future Practitioners, scholar-practitioners explained how feminist practices like collaboration and facilitation are vital tools for deep cultural change in the human rights space. The strategy of sharing a vision based on reflexive learning and the willingness to unlearn counters restorative and revanchist patriarchy. This also requires examining and contesting expressions of oppressive power that feminists may reproduce, confronting them, and cocreating just and intersectional alternatives.

Intersectional organizing

Today it is common for rights and justice advocates to utilize an intersectional lens in their work: that is, a structural analysis of systems of violence and domination, like capitalism, patriarchy, and white supremacy, that recognizes the simultaneous ways that people experience multiple oppressions based on their multiple identities. Applying this to campaigning, organizing cooperatively to reach common aims across groups with multiple identities, priorities and experiences emerged as a critical strategy to create solidarity across issues, organizations, and communities. The Indian Farmers Protest, which sought to repeal controversial farm laws that would privatize farming, was an example shared that described how an intersectional approach to organizing centered the lives of the most marginalized. As a result, women have taken on an important role in this struggle, becoming more present as protesters in public, and galvanizing conversations about the space for and role of landless farmworkers, not just the landowners who started the movement.

There is a new urgency for social justice, human rights movements and grassroots organizing efforts to connect and support one another in response to the rise of authoritarian governance and revitalization of white supremacy, xenophobia and extreme nationalism. This encapsulates a way towards building solidarity across issues, organizations and communities, and utilizing an intersectional approach by centering the experiences and leadership of people affected by multiple forms of oppression. Indeed our resistance not only reacts against oppression but can, as Awino Okech in the Decolonizing Human Rights Education session noted, “build the type of

Critical self-reflection

“We all just assume that we're here […] we don't ask why. There's such a great missed opportunity to bring ourselves present to say why we care. And that would have been a great opening for all of this is just to begin to say, I really care, and here's why." World Café participant

This serves as a reminder to human rights advocates to not only know who we are and our strengths, but to also express the reasons why we care, which are deeply personal and often inspirational. In doing so, we must also deal with our own privileges which are often what enable us to do human rights work. For example, a participant critiqued how the “imperialist lifestyle” “challenges us to consider how the Western way of life, not only developed out of the extractive practices of imperialism and colonialism,” is also insufficiently explored in current discourses and research. Creating spaces for and engaging in critical self-reflection about our positionality and how it informs our advocacy methods is crucial for the social practice of human rights. Practically, spaces for collective reflection should become an integral part of our convenings as well as the academy, because, as Raphael Hoetmer recalled, “it's a way of building knowledge of doing research, of thinking, of action.”

[movement] we want to see!”

11

Critical self reflection can help position human rights actors to envision tactics and design strategies that are iterative, adaptive, and fluid by challenging routinized practices with new thinking. For example, a reflection in the padlet on ‘racial justice - nowhere near?’ reminds us that “those who are part of the system, those who benefit - that is, white people should do the work. [The] burden should not be on the oppressed.” Drawing on Chenoweth’s description of successful movements that peel away support from the parties within the state, in this case, would require more white people to relinquish their privileges and develop new tactics that draw on their specific positionality in the struggle for racial justice. There will be no change without self reflection, accountability and confrontation within human rights spaces.

12

REIMAGING OLD SPACES AS NEW

At SPHR, we directed significant critical attention to the roles played by elite spaces in the human rights ecosystem. Focusing particularly on universities and museums, speakers and attendees asked how we can repurpose the status, visibility, and resources of these institutions to better serve the interests of justice and dignity.

Museums

"Exhibitions that advocate for human rights and social justice are performances of ideology in the world When we acknowledge them as that, we can also locate what sits outside of them: human rights violations.”

Willhemina Wahlin

The museum and curatorial communities are currently in the process of reimagining their roles within society at large. Traditionally founded by civic elites and housing artifacts which only the most privileged can afford, observers within and outside museums have been forced to ask what purpose such institutions serve in times of severe civil and political unrest.

From a human rights perspective, museums provide spaces for representation, truth seeking, education, and awareness raising around critical issues. Whether through photography, historical artifacts, maps and models, or other media, museum galleries provide opportunities to showcase the history and evidence of atrocity, the stories of victims and those impacted, and pose provocative questions for audiences to reflect upon. But in order to rethink how visitors interact with content, museum professionals must break with longstanding traditions of curatorial control and didactic display.

During the Perils of Visualizing Advocacy session, Amy Sodaro highlighted how memorial museums in the United States can serve particular functions as both agents and catalysts for change. For example, the Legacy Museum: From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration in Montgomery, Alabama, was constructed near the site of one of the busiest slave auctions in the country. Honoring the history of this site of memory and tracing that history through to its modern manifestation in the U.S. prison system set the tone for the Museum. In tandem with the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, which chronicles the domestic terrorist violence of lynching, the installations cultivate a profoundly somber experience that challenges visitors to confront these pasts and make critical connections to the current moment.

Museums are working to transform their relationships with the public in creative ways. Calinda Lee emphasized the need to “model strategies for interpreting ‘difficult history’ truthfully and emphatically” through dialogue with all members of impacted communities. She described the development of a large new public park in Georgia’s capital which has provided the opportunity to tell the story of forced labor at the Chattahoochee Brick Factory during the Jim Crow era.

Artists are at the forefront of these transformations. Migiwa Orimo explained, for example, the “People’s Banner Workshops” that she convenes to offer local activists the chance to meet and collaborate on signs, banners, and posters that are used for advocacy purposes, and which may ultimately become part of collections of museums documenting our tumultuous present.

part 5

13

Visualizing advocacy at museums presents both peril and potential. Opening up interpretation and programming allows museum visitors to play a more active role in exhibitions and displays. It also creates the possibility for high-profile controversies within museums, as stakeholders with different interests or goals compete for influence over exhibitions and programming. As a social practice space for human rights, museums and their art and artists should be an increasingly central place for advocacy efforts.

Universities

“How can we talk about changing systems and fighting for human rights if we don’t focus first on our system.”

Leslie King

Universities are commonly viewed as gated and off limits–even and especially by communities closest to campus. They take up neighborhood space and resources, and are often vital players in local economies. As scholars seek to do more in the way of community-based projects with area partners, the baggage and weight of universities’ past actions burden attempts at bridge-building. So, how can higher education institutions acknowledge and repair their problematic relationships?

A promising point of departure is for universities to ask which human rights are promoted on their campuses as highlighted in the session, The Role of Universities in Promoting Human Rights in Cities and Communities. For example, research has found that while American universities are good at promoting freedom of speech, they are failing to ensure the socio-economic rights of their many students, particularly from communities of color or LGBTQIA, who are food or housing insecure. Food pantries and other partial measures on campuses are stigmatizing and ineffective.

A key dilemma, particularly for private institutions, is what Jackie Smith terms the “neoliberalization of our universities,” in which public goods (like access to education) are transferred and protected for private use by the rich. Increased emphasis on community partnerships and the branding imperatives of universities for social justice or the “common good” are in tension with the rising cost of higher education. In the absence of fair and equitable taxation and resource allocation, the private accumulation of wealth and resources facilitated by universities can directly conflict with public interest–a fact that people of lower socioeconomic status in campus communities know well.

Scholar-practitioners must confront the ideologies of their own institutions and be aware of how they represent and reproduce those ideologies and power when working in and with communities. Even deeply entrenched dynamics such as these are not insurmountable, though changing them demands rigorous and consistent intentionality in disrupting and destabilizing harmful power relations, while not reproducing binaries and inequities. Practically, scholar-practitioners can shift their approach to reorient research and community-engaged practice to better align with human rights principles.

14

Opening New Spaces, Creating New Places

“Great potential in bringing together different stakeholders, including artists, curators, and groups, to engage in community organizing for democratic renewal. Learning from each other is critical… Particularly, how to leverage creativity and imagination for creative action.”- Satang Nabaneh

By opening spaces historically restricted to privileged access, institutions like universities and museums can play critical roles as conveners and catalysts for change. In many places, universities do not enjoy independence from political authorities, as the recent dismissal of faculty and students from universities in Hong Kong makes clear. But even in those places, they can provide some space for youth-led activism against authoritarianism, which Nathan Law exemplified in his keynote address.

As Jackie Smith insisted, “Place-making is essential to change-making.” Convening and holding space can be powerful community building tools; respected institutions are uniquely positioned to serve in this way. Engaging strategically with broader movements and communities in new and existing spaces enables deeper learning and the elimination of silos.

Universities and museums generate and convey knowledge. Prioritizing epistemic justice or what we might call “knowledge justice” through the recognition of beliefs, voices and experiences from those who do not call these spaces home serves as an antidote to “knowledge extractivism” and the logic of privatization. “There is no social justice, without epistemic justice” as declared by Tspeho Madlingozi in the session, Approaches to Decolonizing Human Rights Education.

The promise of museums and universities is that they are essential to a thriving democratic society. It is not a given, however, that the resources and spaces of these often powerful and prestigious institutions are devoted to fuller articulations of the public interest, human rights enjoyment and the common good. Only by acknowledging the peril of reinforcing old hierarchies and entrenched privileges can these spaces be reimagined to achieve their full potential as spaces for social transformation.

IS NO SOCIAL JUSTICE WITHOUT EPISTEMIC JUSTICE.”

15

“THERE

TSPEHO MADLINGOZI

6

TOWARD A NEW ADVOCACY PARADIGM

The dire state of our moment loomed heavy over our convening at SPHR21 and remains in the fore of our daily thinking. Confronted as we are with multiple, overlapping, and reinforcing crises, the list of challenges feels infinite: coming ecological collapse, creeping authoritarianism, rising white supremacy, and capitalism’s assault on dignity have manifested in specific and tangible threats to democracy, women’s rights and LGBTQ rights, to name only a few. These are hard times for those who care about human rights. They force us to ask the question: how can we, as human rights advocates, shift away from a perpetually reactive posture and reposition ourselves to affirmatively envision and determine a just future?

From reactive to pre-figurative

“Our struggles and resistances do not only react against oppression or advocate for laws and protocols. They also build new institutions, relationships, economies. They actually build other worlds that can prefigure broader socialeconomic transformations that we want to see.” -

Raphael Hoetmer

When it’s an emergency all the time, actors do not have the time, space, or capacity to think, plan, and innovate. As emergencies mount and layer, advocates attempt to tourniquet the wound and slow the bleeding but cannot put together a preventative platform.

Many presentations at SPHR asserted that human rights provides a framework for guiding future-oriented political projects by setting minimum thresholds that must be met in order to guarantee a life of dignity. Such a forwardthinking approach applies human rights in their utopian mode, to outline what a decent society would look like and map out a way there. Too often, we affirm human rights

norms in the breach (that is, when they are clearly abused), but human rights can also be tools for galvanizing aspirational formations with eyes set out on the horizon, beyond the slog of the present. One commenter hit upon this theme from another angle: “I heard a lot about the harms of capitalism, white supremacy, colonialism and how to work within the existing system, but not a lot about new models or alternative systems.” Ideology, referenced here as “-isms” play a major role in mainstream discussions about power and politics in new ways not seen even a few years ago. This critique suggests that our grappling with the process of building new alternatives remains incomplete.

Creative and prefigurative thinking enables envisioning a future that does not yet exist and allows us to build a roadmap to get there. Seeding the future through a new human rights imagination emerges as essential in a moment fraught with despair and dead ends.

Holistic and pluralistic potential

“Human rights has the ability to highlight the overlap and intersections of struggle and provide a common vocabulary for diverse movements to unite around.”

- SPHR participant

When human rights are described as “universal” it can mean an all-encompassing enterprise, applying to all, overriding our divisions, while acknowledging our particularities. While this view appears to offer an answer to all of the world’s questions and address all of the world’s problems, it puts more weight on the shoulders of human rights institutions than they can bear. At the same time, especially at a time of extreme polarization and atomization, the search for a holistic program girded by human rights is appealing.

part

16

Though a universal agenda, fragmentation among progressive movements hinders the ability to build together a forward looking human rights movement. Identity-based movements leverage some degree of homogeneity among its supporters while, hopefully, appreciating the way in which an intersectional analysis opens space for differences within the whole. For example, social movements, including the movement for Black lives and the Women’s March in the US, have encountered dilemmas within their ranks as individuals with intersectional identities struggle to find their place.

One way to view human rights as a “unifying” or “foundational language,” is to view it not as maximalist but as minimalist, as a system of norms, values, and laws that only thinly constitutes or bounds a political community. But what is community? As explored by Art Jipson during the Workshop on White Nationalist Movements and Alt-Right pandemic-related methods, community is not only a place, space and feeling, but is also a system and process that can be undermined through creative opportunities curated specifically to cultivate extremists. Thus, it is important to not only see human rights as a useful organizing approach or tool, but also its holistic nature in motivating a politics of solidarity and cooperation amongst diverse constituencies.

While we acknowledge the immense complexities of human rights, we must also engage in a human rights project that generates hope. This project should be premised on the idea that mutual support and resilience implies recognizing pain, frustration and the loss of hope, and collectively trying to find ways out. Hope and promise are captured in the desire for “ a unified voice” to counter belligerent intolerance, as organizer Alwiyah Shariff of Ohio Voice reminded us: “It’s hard to imagine change. I probably won’t be free in my generation. But we are fighting towards it.”

Moving to concrete social practice

So what is the way forward, we ask ourselves. There are limits to conventional and fixed thinking: for example, instead of reactive, be proactive; instead of being divided, let’s be united is not innovative. But we found at SPHR new ways of describing a way forward that transcends binary thinking. Nathan Law, pro-democracy youth leader from Hong Kong and SPHR keynote speaker, described his approach: Be water

17

Famously, martial arts fighter and actor Bruce Lee put it this way:

This approach suggests that actors in human rights and justice struggles should plan to be adaptive through iterative actions shaped by immediate circumstances but informed by what’s come before. Nathan Law expanded, “Have the flexibility to modify as necessary to continue on your path.” Advocacy must be fluid, not static, and possess agility to respond to current circumstances thoughtfully and creatively.

This requires planning, creativity and flexibility that is easy to describe and difficult to cultivate. Traditional adversarial models of advocacy root our feet in the ground, digging in to face off. An individual in attendance captured this shift in thinking nicely:

“Nathan’s story challenged me to think about activism in a totally new way! We always have this certain perception of what activism is or how it should be. However, Nathan’s quote ‘Be Water’ helps in realizing that governments and societies are always shifting and changing; therefore, we must ensure that our activism is shifting as well.”

A new human rights advocacy praxis demands moving from thinking to acting and back to thinking to inform further action. As a participant in our World Café concluded: “Knowing better is not ALWAYS doing better, we MUST act.” The keynote of Erica Chenoweth raised the question of whether human rights activists are innovating at the same speed as authoritarian forces. The study of resistance movements is helping to share an evidence base about what works and can help keep movements ahead of the curve. As another participant remarked:

"Authoritarian governments and states are learning between them, sophisticated repressive tactics and criminalization of dissidence. New technologies for surveillance are used, and media and research journalists are repressed. It is crucial we learn between movements and realities on repression and on resistance.”

“Be like water making its way through cracks. Do not be assertive, but adjust to the object, and you shall find a way around or through it. If nothing within you stays rigid, outward things will disclose themselves. Empty your mind, be formless. Shapeless, like water. If you put water into a cup, it becomes the cup. You put water into a bottle and it becomes the bottle. You put it in a teapot, it becomes the teapot. Now, water can flow or it can crash. Be water, my friend.”

18

Contributors

Shelley Inglis

Shelley Inglis is the Executive Director of the Human Rights Center and Research Professor of Human Rights and Law. She comes from the United Nations Development Programme where she held various management positions working on peacebuilding, democratic governance, rule of law and human rights and the Sustainable Development Agenda at headquarters in New York and regionally based in Istanbul, Turkey

Satang Nabaneh

Satang Nabaneh is the the Director of Programs for the Human Rights Center at the University of Dayton She is a legal scholar and human rights practitioner Her expertise spans international human rights law and monitoring mechanisms; human rights in Africa, gender equality and women’s rights, democratization in Africa and comparative constitutionalism.

Joel Pruce

Joel R. Pruce is Associate Professor in the Department of Political Science and Director of Applied Research and Learning at the Human Rights Center, where he also coordinates the Moral Courage Project.

Paul Morrow

Paul Morrow is a Visiting Assistant Professor of Philosophy at the University of Dayton, cross-appointed in the University’s Human Rights Center. He has published essays and articles on Holocaust museums, children’s art in wartime, and human rights advocacy on TikTok His book Unconscionable Crimes: How Norms Explain and Constrain Mass Atrocities was published in 2020 by MIT Press.

Alfredo Ortiz

Alfredo Ortiz is an Associate Professor in the PhD Program in the Dreeben School of Education at the University of the Incarnate Word, and part time faculty at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies (MIIS), focusing on Nonprofit Management and Social Change. He is also an action-researcher and designer/facilitator of organizational change processes, working in international and local development contexts for the last 18 years

19