New Chancellor Dennis Assanis gets to work

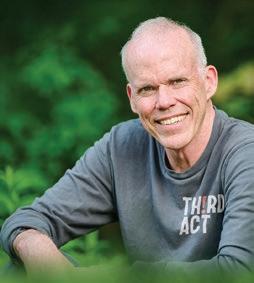

Ben Halpern asks us to prove him wrong

Ania Jayich journeys from tennis to tenure

New Chancellor Dennis Assanis gets to work

Ben Halpern asks us to prove him wrong

Ania Jayich journeys from tennis to tenure

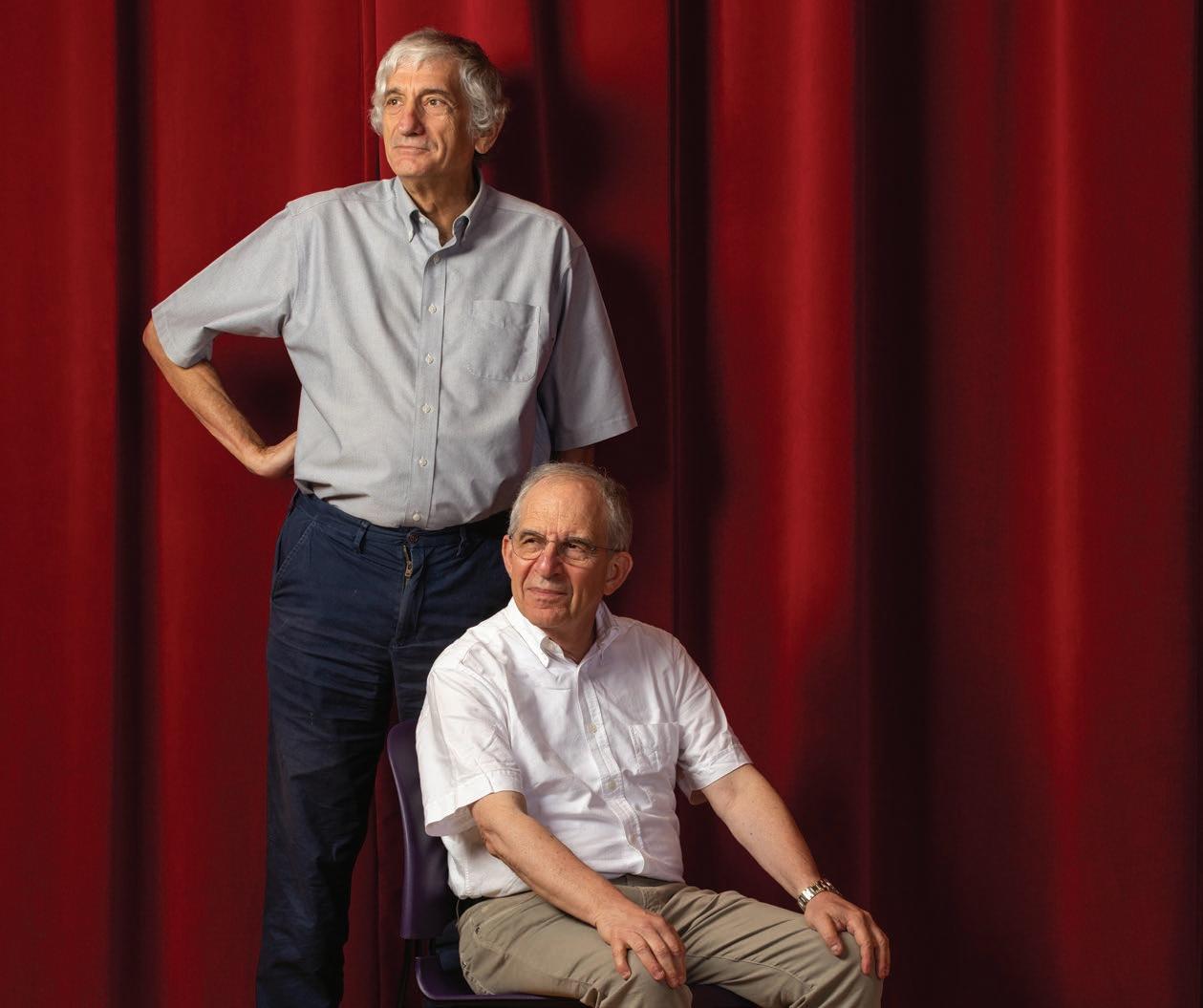

Professors John Martinis and Michel Devoret win the 2025 Nobel Prize in Physics

I feel incredibly honored to be a part of UC Santa Barbara, with its extraordinary community of scholars and prolific environment of discovery and creativity. UC Santa Barbara is recognized worldwide as an intellectual and creative powerhouse with faculty and alumni receiving countless honors, among them the National Medal of Humanities, National Medal of Science, the National Medal of Technology and Innovation, the Fields Medal, National Academy Memberships, Guggenheim and Fulbright Fellowships, Pulitzer Prizes, and Nobel Prizes.

Indeed, we just celebrated two Nobel Prize winners, our physics Professors Michel Devoret and John Martinis, who won the 2025 Nobel Prize in Physics! This is a very special moment for UC Santa Barbara, proudly marking our seventh and eighth Nobel laureates (nine Nobels counting alumna Carol Greider ’83).

The curiosity and perseverance inherent to such accomplishment epitomizes the work happening at UC Santa Barbara across all disciplines, from engineering and natural sciences to the arts, humanities and social sciences. What may begin with one inquiring mind can impact countless lives with the support of our academic community that nurtures the conditions for creativity to unfold.

The education, research and service happening on our campus helps us better understand the world we live in, advances our society, strengthens economies and improves our quality of life. I know that, together, we will stay open, stay curious and enlighten the world with brilliant thought, creativity and discovery.

As a community, we will always continue to work together to realize our shared vision and be true to our mission as a preeminent and leading institution in higher education, globally.

I hope you’ll join me in honoring the Gaucho spirit of curiosity and supporting our institution as we strive to be a continuous engine of discovery and make our world a better place for all.

Dennis Assanis CHANCELLOR

Professors John Martinis and Michel Devoret

U.S.

3 From the Chancellor ON

6

News & Notes

Top stories from around campus

Book Talk

Five books that matter

The Real World

Building an electric racecar

Then & Now

Cabin fever

Athletics

Olivia Howard ’27 has heart

Off the Clock

Ania Jayich's success in tennis and physics

Gaucho Giving

A family's legacy

Research Highlights

UCSB scientists are advancing knowledge in vital fields of research

Letter From the

Executive Director

Bright Spot

Dayna Quanbeck leans into her instincts, comes out on top

Gaucho Creators

Cutting-edge medical research from Angela Belcher ’91, ’97 and Deblina Sarkar ’10, ’15

Newsmakers & Milestones

Championship athletes

Business Spotlight

Andrew ‘AJ’ Rawls ’12 offers a community space for makers and dreamers

Noteworthy

Alumni successes

Global Gauchos

The global effort to stop plastic pollution at its source

Good Works

Gauchos running unique recycling efforts across campus

Fall/Winter 2025

Volume 5 No. 1

UC SANTA BARBARA MAGAZINE

Executive Editor Shelly Leachman ’99

Associate Editor Debra Herrick Ph.D. ’11

Art Director/Designer Matt Perko

Contributing Writers

Julia Busiek

Nora Drake

Sonia Fernandez '03

Keith Hamm '94

Nick Mathey

David Silverberg

Harrison Tasoff

Jillian Tempesta

Isabella Venegas '27

Copy Editor

Julie Price

Contributing Photographers

Jeff Liang

Matt Perko

UC SANTA BARBARA EXTERNAL RELATIONS

Vice Chancellor

John Longbrake

Executive Director

Alumni Affairs

Samantha Putnam

Editorial Director

Shelly Leachman

Chief Marketing Officer

Alex Parraga

UC Santa Barbara Magazine is published biannually by the University of California, Santa Barbara, Santa Barbara, CA 93106-1120.

Email: editor@magazine.ucsb.edu Website: magazine.ucsb.edu

The inaugural Gaucho Welcome spirit rally kicked off the new school year in festive fashion.

Faculty members Nina Miolane, an electrical and chemical engineer, and physicist Chetan Nayak, were both recognized in TIME Magazine’s Best Inventions 2025. Miolane, working with REAL AI and the Bowers Women’s Brain Health Initiative, created HerBrain, the first digital twin of the maternal brain. The tool illustrates how brain structures change during pregnancy and beyond, offering science-based insights into changes people experience during this time. A HerBrain app is set to launch by 2027. Nayak is director of UCSB-based Microsoft Station Q, innovators of Majorana 1, a first-of-itskind topological quantum processor that paves the way for a more fault tolerant quantum computer.

Teaching professor Tengiz Bibilashvili led the U.S. Physics Team to a historic, fivegold-medal victory at the 2025 International Physics Olympiad in Paris, France, besting 85 other countries. The team, comprised of five high school students from across the country, received intensive training at UCSB prior to their trip to France. Bibiliashvili, whose coaching staff includes UCSB students and alumni, has been the team’s academic director since 2021.

Professors Tamara Affifi, in the communication department, and Nancy Collins, in psychological and brain sciences, are working with virtual reality company Rendever to improve mental health and social connectivity for older adults through VR-based social interventions. With a new $3.8 million grant from the National Institutes of Health, they are bringing VR into homes across the U.S., and pairing with a home care provider to train health aides how to use the VR with older adults with and without dementia.

Iman Djouini, a teaching professor in UCSB’s College of Creative Studies and an artist working primarily in print media and public installation, was selected to present a solo exhibition at the upcoming Venice Art Biennale in Venice, Italy. The Biennale is widely recognized as one of the most prestigious and influential cultural events in the field of contemporary art, renowned for showcasing and launching the careers of leading artists worldwide.

4

Graduate student Jordan Thomas, a doctoral candidate in anthropology, was shortlisted for the 2025 National Book Award for Nonfiction for “When It All Burns: Fighting Fire in a Transformed World.” The book, which details Thomas’s harrowing experience battling wildfires as a Los Padres Hotshot, also deeply engages ecology, forestry and Indigenous history, “bringing readers to the front lines of the climate crisis.”

6 UC Santa Barbara baseball’s strikeout king is now the program’s highest-drafted player ever. With the second overall pick in the 2025 Major League Baseball Draft, the Los Angeles Angels selected Gaucho pitcher Tyler Bremner, making him both the first college player and the first pitcher chosen this year. Bremner joins Michael McGreevy and Dillon Tate — who was previously the program’s highest-drafted player as the fourth overall selection in 2015 — in the elite club of Gaucho pitchers taken in the first round.

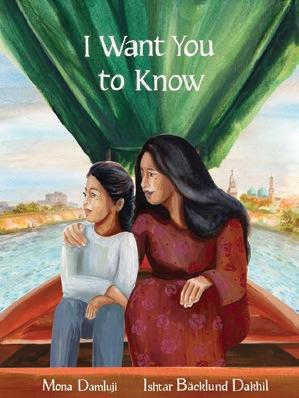

An assistant professor of film and media studies, Mona Damluji studies the power of storytelling across film, architecture and literature. Her research explores underrepresented media histories and the cultural politics of energy, cities and infrastructure in the Middle East and its diasporas. Her forthcoming book, “Pipeline Cinema” (UC Press), reveals how oil companies shaped visual culture in Iran and Iraq through film sponsorship during the 20th century.

Also the author of the children’s books “Together” and “I Want You to Know,” and a Peabody and Emmy Award-nominated producer of “The Secret Life of Muslims,” Damluji connects creative expression with social justice throughout her work.

Here, in first person, Damluji shares five books that continue to shape her perspective — and remind her of the power of story to bring light, laughter and understanding.

“It was hard to narrow it down,” she says, “but I’m so happy to share these five books. I turn to memoir for perspective and guidance — and to find ways back to laughter and connection, even in the darkest times.”

By Mira Jacob

Jacob’s graphic memoir is an original, insightful and laugh-out-loud funny examination of life, love and parenthood as a South Asian and Brown woman in the United States since 9/11. I’ve returned to this masterpiece many times over the years when feeling overwhelmed by the uncertainties, absurdities and cruelties of American xenophobia.

By Hala Alyan

Alyan’s second novel is an engrossing portrait of Beirut, Lebanon — a beautiful and complicated city close to my heart — told through the web of desires, fears, secrets and ambitions of one multigenerational family. These are characters I have wanted to continue to know and spend time with long after finishing this novel. It is the perfect book to draw you into Alyan’s satisfyingly deep and provocative oeuvre of prose, poetry and criticism.

By Safia Elhillo

Elhillo’s time travel odyssey — about a teenager searching for belonging, facing her demons and growing up with her mother’s decision to immigrate from Sudan to the American suburbs before she was born — captivated me from its first words. Written as a novel in poetic verse, this is a book that deserves to be heard aloud, and so I especially recommend listening to the audiobook, read magnificently by the author.

By Michelle Zauner

Zauner’s memoir about the anticipation of grief and the loss of a loved one shook something loose inside of me when I listened to it. The author, a singer-songwriter and vocalist of the indie band Japanese Breakfast, reads the audiobook with equal parts tenderness and fury. Zauner’s writing conjures a blueprint for how one’s heart can break open and expand infinitely while caring for an unwell parent, or any person who has devoted their life to caring for you.

By Ady Barkan

The late, great Ady Barkan was one of America’s most influential activists of the last decade. His memoir, written a few years after his ALS diagnosis, is an antidote to despair and a reminder of the strength we humans of conscience carry within ourselves to persevere and lift up others. I was lucky to have Ady as a dear friend for seven years and his words will forever act as my compass through dark times.

BY SONIA FERNANDEZ

FORMULA ONE (F1) is peak motorsport — speed, power, cuttingedge technology and teamwork. UC Santa Barbara’s Gaucho Racing taps into that spirit, building electric racecars for the Formula SAE Electric (FSAE-E) competition.

“It’s a national competition that happens every year at Michigan International Speedway,” says Thomas Yu, Gaucho Racing’s president this past year. “They have about 100 or so teams that compete at different events,” from car design to organizational skills and business acumen.

The goal: Give engineering students real-world experience in automotive design and teamwork.

At the center is a battery-powered drivetrain in a lightweight chassis, with systems to regulate power, safety, braking and temperature.

“Gas-powered formula cars are horrendously expensive,” says Kirk Fields, UCSB senior development engineer and Gaucho Racing’s faculty adviser. “Most teams that are successful could spend $500,000 to $1 million on their car.”

With fewer resources, Gaucho Racing focuses on electric vehicles, aligning with the industry’s future and UCSB’s engineering strengths. The team launched

its first EV in 2021 and now includes more than 60 students across disciplines, working on mechanical, electrical and business aspects of the project.

While the Michigan event lasts six days, preparation runs year-round. Teams submit reports, give presentations and build a car from scratch. In UCSB’s machine shop, members fabricate the frame, install components, apply the fiberglass body, add wheels and test.

Meanwhile, they juggle fundraising, presentations, classes — and limited time. Every engineering decision carries tradeoffs: Reuse parts from last year or design anew? Stick with one motor or risk complexity with hub motors at each wheel?

“In F1, you’re really trying to prove who’s the best of the best automotive engineers,” says Alex Fu, external VP and aerodynamics lead. “But in SAE, because we’re all new engineers here, we’re trying to develop our skills so we can get into the workforce.”

“None of the work they’re doing is ‘useless’ at all,” adds Fields. “That’s what we should be doing — learning and passing things along so that the team next year doesn’t have to do it again.”

The team studies other competitors, adopting ideas from brake systems to

steering wheels. Safety and comfort remain priorities, especially heat management. Lithium battery fires are harder to control than engine fires — something they witnessed last year when another team’s car caught on fire.

“We were doing ice water cooling before the race started,” says mechanical engineering student Curren Somers, describing this year’s strategy to keep temperatures manageable for the 20-minute endurance run in Michigan’s summer heat. Firewall design and molded bucket seats also boost driver safety.

Armed with its most advanced car yet, Gaucho Racing headed to Michigan in June, improving over last year’s performance and scoring the most points they’ve had to date.

For team members, the real win is collaboration and growth. They learn problem solving, big-picture thinking and how to balance innovation with humility. Some graduate into industry or higher education, while others stay on to mentor newcomers.

Even in tough moments, passion for the project holds the group together. “It’s because we’re each part of something bigger than ourselves,” says Diego Vasquez, internal VP, “and this thing is really special.”

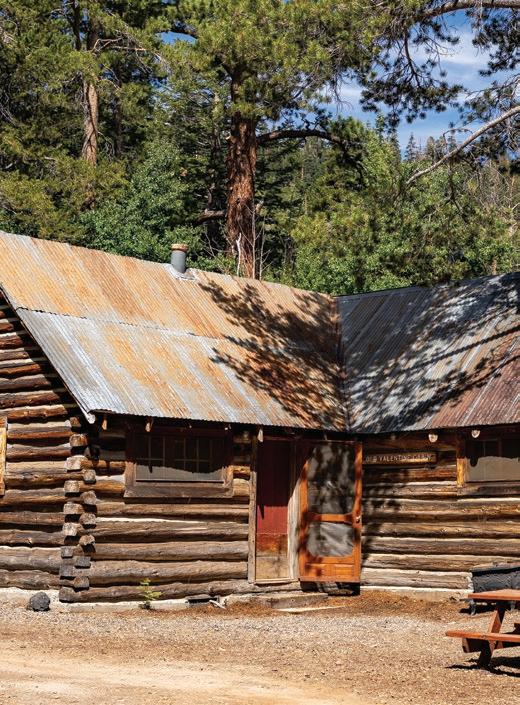

They’re not only straight out of the past, they’ve really never left. The historic cabins at UCSB’s Valentine Camp Reserve — forested property at the base of Mammoth Mountain — were built more than 100 years ago and haven’t changed a ton since then. Yet for decades they’ve hosted students, scientists and environmental stewards — and survived some massive snowstorms. Now, though, renovations are underway to fully modernize the facilities to ensure the cabins survive another century.

“They’re basically logs that are nailed and glued together,” Reserve Director Carol Blanchette says of the cabins. The string latches on their doors, mortar and hewn wood planks filling many of the gaps between logs, and cast iron stoves attest to their heritage.

Step inside and you will find the essential amenities of modern living, including electricity, propane and plumbing, with water piped in from one of the property’s many springs. But standing outside amongst the trees, you’d likely never know it.

A hidden heart condition couldn’t stop

Olivia Howard ’27 from her Gaucho debut

BY NICK MATHEY

, the first time you step onto the field in your school’s jersey is the moment you’ve dreamed about since you could first kick a ball. For UCSB’s Olivia Howard, that debut was more than the culmination of years of early mornings, late practices and countless games.

It was proof she had turned a challenge into a powerful new chapter in her soccer journey.

Howard began playing soccer at a young age and, like many of her teammates, fell quickly in love with the game. By middle school, her passion had sharpened into a goal: She wanted to compete at the college level.

In eighth grade, she attended the NCAA Women’s College Cup and watched Stanford battle in the Final Four. The pace, the skill, the intensity of that match left an imprint.

“This is it. This is what I want to do,” Howard remembers thinking.

Fast forward a few years, and there she was — wearing UCSB blue and gold, standing across from Stanford in the 2024 NCAA Tournament. It wasn’t just another game. It was a full-circle moment, facing the very program that had inspired her dream, now as a competitor.

Before she could step onto the field as a Gaucho, Howard faced an obstacle she never saw coming. During her incoming physical, the team’s routine

echocardiogram revealed WolffParkinson-White syndrome, a congenital heart defect that can trigger dangerous arrhythmias.

“I was in complete shock,” she says. “I felt fine. I had just trained all summer and didn’t think anything was wrong. Honestly, I didn’t want to believe it.”

Multiple doctors delivered the same message: If she wanted to keep playing soccer, she would need heart surgery.

“It was surreal,” Howard says. “I had been in Santa Barbara for just eight days, and suddenly, I was facing the possibility that my dream might be over.”

Surgery came quickly. When she woke, there was a chicken sandwich waiting, along with instructions that she could resume soccer activities in three days. Within a week, she was back on the field.

Though cleared physically, Howard still faced hurdles.

“It didn’t heal perfectly and was still a little painful,” she says. “The mental side of it was way more challenging. When you wake up from the procedure, nothing feels different.”

On her first day back, head coach Paul Stumpf pulled her out of practice early.

“Paul said, ‘You had a great first day. You’re good. Just sit and rest right now,’” Howard recalls. “I was emotional because I wanted to push through. I already felt three days behind.”

That reassurance became a turning point. If her coach believed she was ready, she knew she could still compete with anyone on the pitch.

Just 17 days after surgery, Howard suited up for her first collegiate match against Loyola Marymount. In the 45th minute of her first half of college soccer, she scored.

“That goal meant everything,” she says. “It was proof I had made it back — that I belonged here.”

From that moment, she played with gratitude. Every sprint, every practice, every game became a gift.

Her support system proved vital. Her parents navigated the medical process, while her coaches and teammates made sure she never felt isolated.

“They understood this was bigger than soccer,” she says. “They told me to focus on getting healthy first. I couldn’t have asked for a better support system.”

Her family has since turned the experience into advocacy, connecting with a Dallas-based foundation that provides affordable EKGs to young athletes and helps families detect hidden heart conditions.

Today, Howard is firmly rooted in Gaucho life. Long bus rides, pregame rituals and team dinners have become the backdrop of lasting friendships.

“I feel really at home here,” she says. “Being a Gaucho is something I was meant for. I can’t imagine being anywhere else.”

Her story is more than a comeback. It is a reminder that some of the toughest victories come before the whistle ever blows — and that the real triumph lies in the courage to keep playing.

“That goal meant everything. It was proof I had made it back — that I belonged here.”

– Olivia Howard

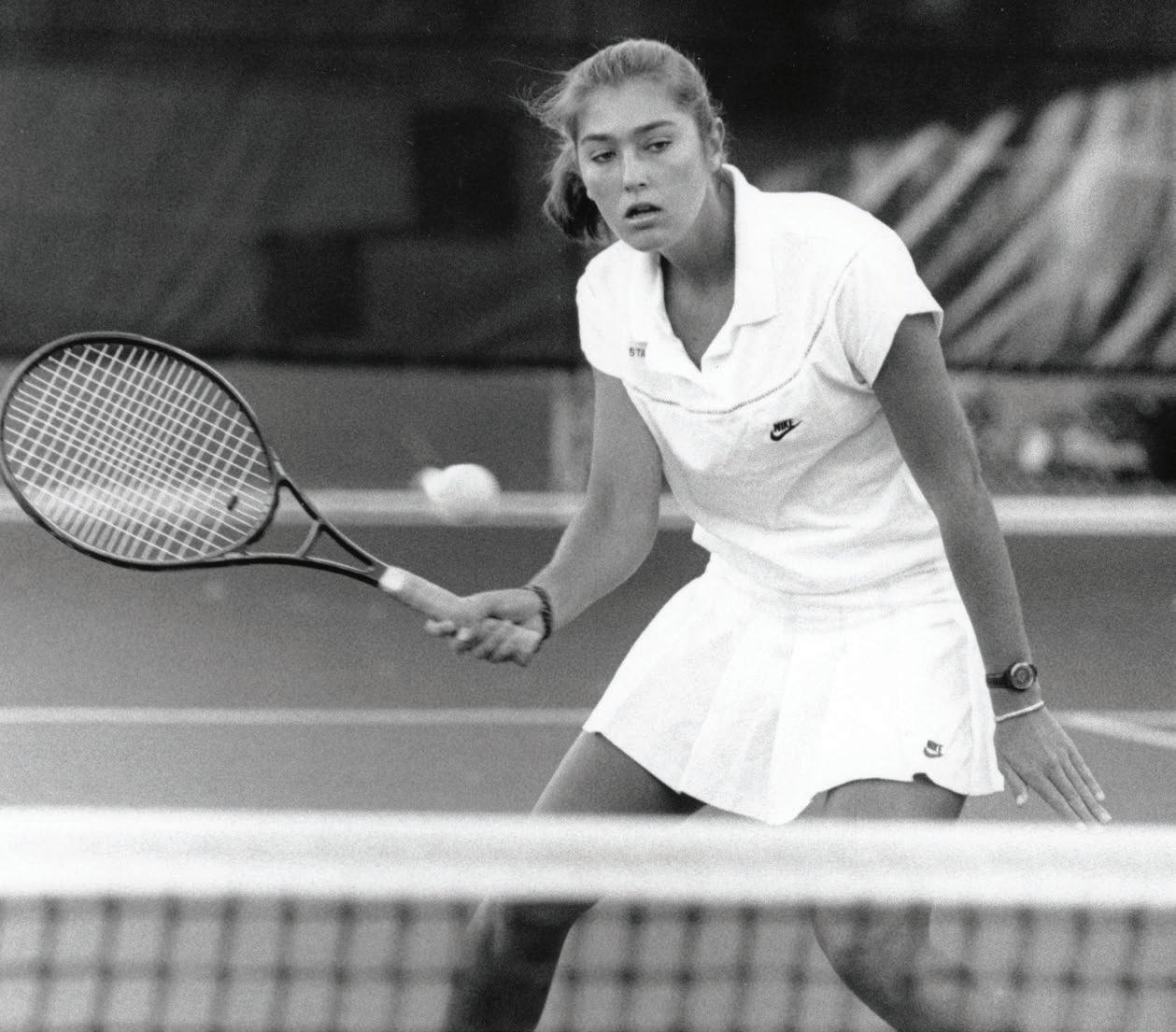

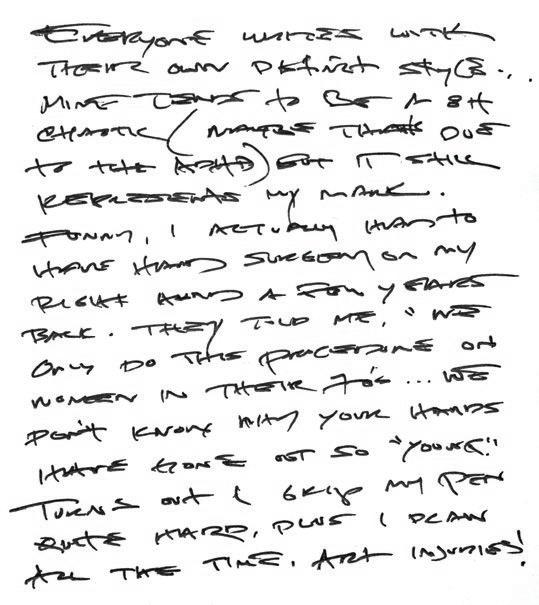

A former tennis prodigy, Ania Jayich brings the same grit and focus to physics that once powered her athletic success

BY NORA DRAKE

Ania Jayich has an athlete’s mindset when it comes to scientific innovation. She describes her competitive drive as inherent and internal, something that has motivated her for as long as she can remember. “Some of the things that drive me are, ‘I want to be the first one that does this,’ or, ‘I want to do it better,’” she says. “I think I was born a competitive person, and I try to leverage that in a positive way.”

A professor of physics at UC Santa Barbara and co-founder of the interdisciplinary Quantum Foundry, Jayich qualifies her ambition by noting that she doesn’t let it get in the way of successfully working with other researchers. “I think the way that I behave doesn’t reflect my competitive spirit, necessarily,” she says. “I have many collaborations.” It’s no surprise her drive carried her into academia; after all, she once held the No. 1 national ranking for women’s 18-and-under singles tennis.

Jayich’s parents were also physicists, who prized academics over athletics and were not shy about sharing their values — which meant sometimes having to make tough choices and have difficult conversations. “Growing up in my household, there was no way that I was going to be sacrificing anything academically for tennis,” she says.

Far from pushy sports parents living vicariously through their children, her mother and father were mostly disinterested in her athletic abilities. She recalls one match in Ojai in particular. It

was one of the few chaperoned by her dad, who generally preferred to leave those duties to her mom.

“After the match, I walked up to him,” she says, “and he was like, ‘So, how did you do?’” (She won.)

Jayich reached a crossroads when she was 18 and ranked No. 1 in the country: Go pro or play in college? She dipped her toe into the pro lifestyle by traveling to a few tournaments. “I distinctly remember feeling like, ‘This is not for me. I like it, but not this much,’” she says. “I realized at that point that the girls on the pro tour were very different from me. I didn’t feel like I fit in.”

Ultimately, she decided to attend Stanford University, which had both a top tennis team and a stellar academic reputation. She received a full scholarship that allowed her to take six years to complete her degree, so that she could double major in mathematics and computational science and in physics while still attending practices and traveling with the team. Her team won the NCAA team tournament in her junior year and she made it to the NCAA individual finals her senior year.

Again, she thought briefly about going pro. “At the time, the good female collegiate players were not really making it on the pro tour after college,” she explains. “I mean, a lot of them played on the tour, but you weren’t going to be in the top five.” She knew it wouldn’t be enough for her. She decided to transition to full-time academics.

Jayich got her Ph.D. at Harvard University, while volunteering as an assistant coach for their tennis team to stay involved in the sport. She considers herself lucky to have made it from age seven to age 24 playing a demanding sport and never experiencing any significant burnout. Her ambition never wavered. “I think it’s also because if I wanted to quit, my parents would have been super happy about it,” she says wryly. “My drive came from within.”

Not that she never experienced moments of doubt. “A couple of my friends did keep playing after college,” she says. “When I was in grad school, a good friend from Stanford was playing the tour and living in Boston, so I saw her life up close. She’d get up in the morning, eat some protein-filled breakfast, then she’d go work out for three hours, eat, lift, play tennis again, etc. Somehow, I missed that part.”

She remains grateful to the sport for teaching her skills that she still uses in her career, like time management and the importance of hard work. “To be good at something, you have to work hard and you have to train,” she says. “And it’s not always easy, and it’s not always fun.”

Now, Jayich works to discover quantum phenomena to create highly sensitive sensors from engineered defects in diamonds, with the goal of being at the cutting edge of imaging the atomic structure of individual proteins. There are many days that are neither easy nor fun.

“Our group works on developing quantum technologies or realizing quantum mechanical phenomena and controlling them,” she says. “We’re trying to build sensors that could be applied to imaging biological systems or new material systems. The real-world application would be, for instance, imaging the structure of a protein with high spatial resolution magnetic resonance imaging or performing high throughput proteomics.”

When she’s not in the lab, Jayich supports her three children in their burgeoning tennis careers (unsurprisingly, they are quite good), often helping them warm up before practices and matches. Ever her parents’ daughter, she is careful to remind them that school is still more important than sports.

In addition to preparing her to parent scholar-athlete children, Jayich says that the most important thing tennis taught her was how to lose.

“It made me resilient,” she says. “Early in my career, I would get grant proposals denied and it just bounced off of me. You lose a lot in tennis. So in my life now, if something doesn’t work, it doesn’t stop me. I think I have a pretty healthy approach to failure.”

BY

BY JILLIAN TEMPESTA

When David McDonald ’85 thought about how to honor the people who shaped his life, he turned to planned giving. His bequest will create four scholarships, establishing a legacy at UC Santa Barbara while extending his family’s values and stories.

McDonald’s approach reflects the personal nature of planned giving. By including UCSB in an estate plan, donors can provide lasting support for the causes that are dear to them. From bequests and charitable gift annuities to gifts of real estate or retirement assets, each commitment is a promise for the future.

“My father passed away in 2011; my mother is going strong at 90. They’ve been the most important people in my life, and I wanted to honor them,” McDonald says.

McDonald tailored each named scholarship to reflect that person’s life experience, which he hopes recipients will share.

His father, Mac, grew up abroad in a military family. Just before World War II, he was evacuated from China and the Philippines along with his mother and sister. Mac served as a Navy medical

“My grandmother would be honored to learn that a scholarship in her name will help a student realize his or her academic goals.”

— David McDonald

corpsman during the Korean War before attending college, earning a criminology degree from UC Berkeley while working nights as a Walnut Creek police officer. He went on to a 30-year teaching career.

Jan, McDonald’s mother, grew up in a middle-class family in Oakland during the Great Depression. She graduated from UC Berkeley in 1958 with a degree in social services. For over 40 years, she helped individuals and families as a foster care social worker in Contra Costa County, while at the same time taking care of her own family.

While his parents worked, McDonald and his grandmother, Josephine, would explore the city in pursuit of their passions. They would watch planes at the airport, root for the Oakland A’s baseball team, and visit the courts. Later, at home, McDonald would play judge — an early hint of his career in law.

“My grandmother would be honored to learn that a scholarship in her name will help a student realize his or her academic goals,” McDonald says. “She had only a sixth-grade education. She worked as a cafeteria worker in the Oakland school system and was the sweetest person you could meet.”

Josephine attended McDonald’s graduation from UCSB in 1985 and, in 1989, from the University of San Francisco School of Law.

Now retired from a career of civil litigation, McDonald serves as a judge pro tem in the California Superior Courts, where he adjudicates matters with people from all backgrounds.

“I want to keep the memory of my time, my parents and my grandmother alive through something lasting, rather than a one-time gift. College is much more expensive now than when I attended. Now, students face high housing and living costs,” McDonald says.

Some of McDonald’s happiest days were spent at UC Santa Barbara. He recalls the serene campus and the salty air, feeling deep contentment as he walked to Campbell Hall for class.

In addition to the four scholarships, McDonald’s bequest will create an endowment to support the UCSB Library, which was his second home while he lived on the Mesa in Santa Barbara.

In honoring his relatives, McDonald has built a bridge from his family’s past to countless students’ futures.

The future of biomaterials

BioPACIFIC MIP, led by UCSB’s Craig Hawker and Javier Read de Alaniz with UCLA partners, accelerates AI-driven biomaterials discovery with national impact. A new $19.8 million National Science Foundation award expands its work in sustainable materials, integrating chemistry, biology, robotics and AI while training the next generation of scientists.

AI, health care and environmental science are among the vital fields benefiting from UCSB research

Mechanical engineers David Haggerty and Elliot Hawkes have developed a soft robotic intubation device that autonomously guides a breathing tube into the trachea, offering a faster, safer solution in critical emergencies. Tested with medical professionals, the tool achieved up to a 100% success rate and could transform lifesaving care.

By creating chipscale versions of cold atom and trapped ion experiments, engineer Daniel Blumenthal and his team are shrinking tabletop quantum systems into palm-sized devices. Their work could bring ultra-precise sensing, timekeeping and even dark-matter searches out of the lab and into the real world.

Developing AI for all

Computer scientist Arpit Gupta is advancing lowcost network foundation models to make powerful AI systems more efficient, scalable and accessible. Recognized with two prestigious Google awards, his research bridges machine learning and computer networks to transform how large-scale AI infrastructure is deployed.

Pioneering molecular solar thermal energy storage, Grace Han — a 2025 Moore Inventor Fellow — is designing fuels that capture sunlight, store it in chemical bonds and release it later as heat, advancing clean, emission-free alternatives to fossil fuels.

Chemist Justin Wilson has developed a simple filter to extract rare earth elements from electronic waste, offering a cleaner, safer and more economical way to secure a domestic supply of these critical metals. His team’s method could transform recycling and reduce reliance on toxic processes.

Acoustic secrets of the sea

Geophysicist Robin Matoza and his team are decoding the surf’s hidden signals, using infrasound and seismic waves to trace where and how ocean waves break. Their findings could enable new ways to monitor coastal conditions and hazards.

With NSF funding, mechanical engineer Eckart Meiburg is studying how microscopic particles like silt and clay bind together to drive landslides, erosion and other large-scale sediment flows. The research could improve disaster prediction and help protect infrastructure worldwide.

BY DEBRA HERRICK

The future of technology isn’t about replacing human skill with machines but about designing tools that work alongside us. At UC Santa Barbara, Jennifer Jacobs is pioneering fabrication systems that adapt to human input, material behavior and domain expertise.

With support from a prestigious National Science Foundation CAREER Award, her research challenges the rigid workflows of digital fabrication — like 3D printing or CNC milling — by creating technologies that foster improvisation

and real-time feedback. The result is a vision of automation that honors creativity, craft knowledge and the unpredictable nature of materials.

Jacobs’ Expressive Computation Lab explores what happens when users adapt machines to specific contexts, from product design to construction and engineering. By blending manual and automated processes, her systems allow makers to intervene mid-fabrication, respond to shifting conditions and integrate centuries-old practices

into digital tools. Beyond advancing engineering, the work carries a human impact: expanding who can use fabrication technologies, how accessible they are and how innovation reflects the way people actually create.

“You can think of this as the next step in personal computing,” Jacobs says. “Just like software became customizable for musicians, writers or scientists, we want fabrication tools that adapt to specific professions and workflows.”

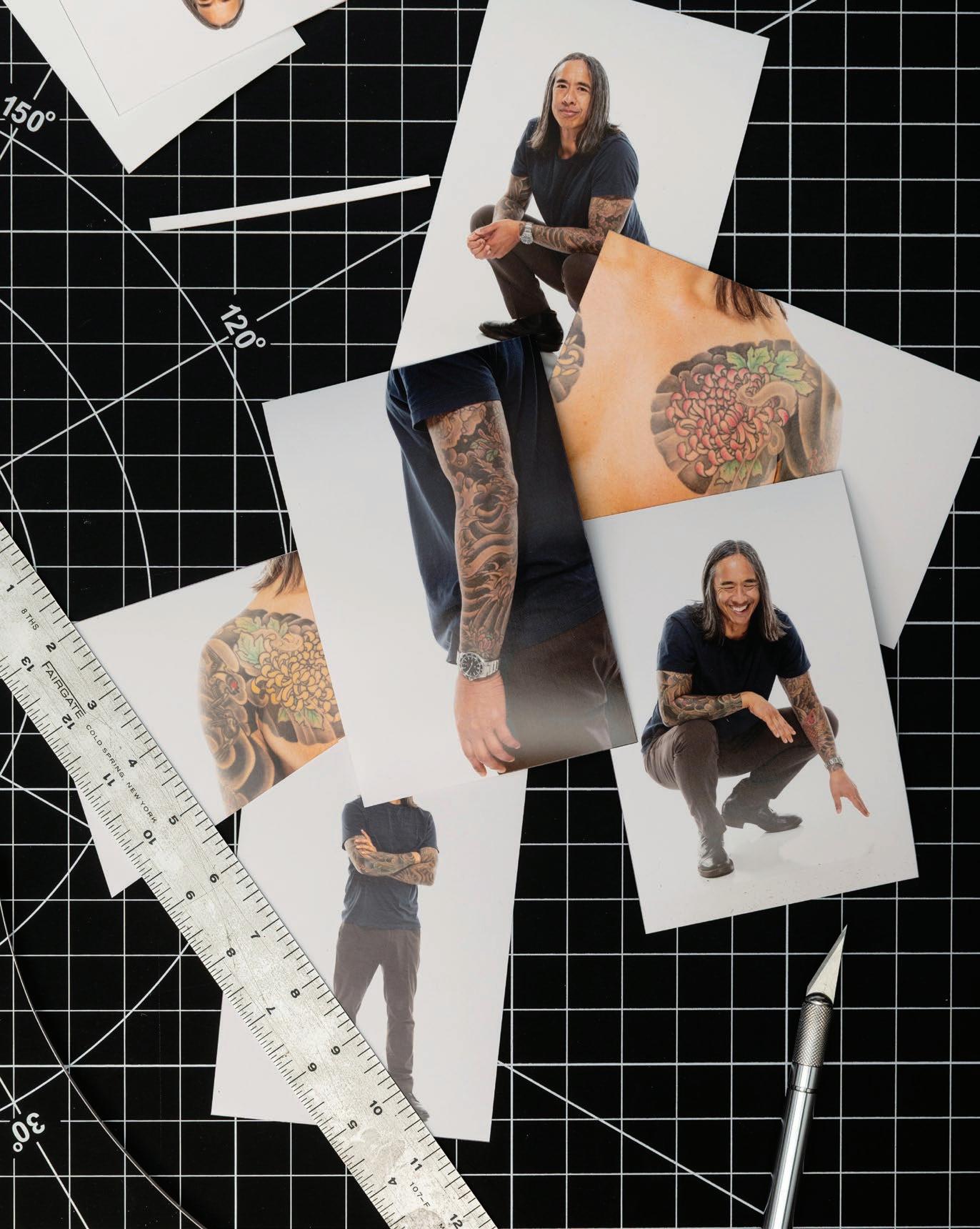

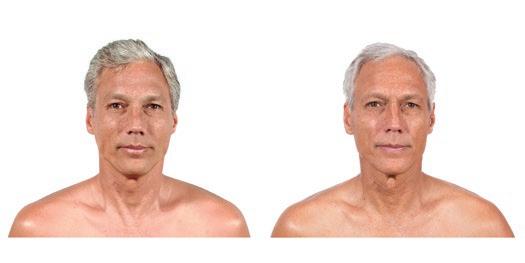

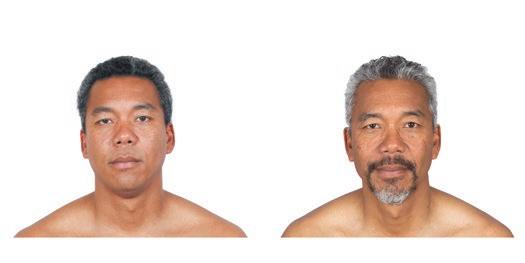

Kip Fulbeck’s ‘The Hapa Project’ brings together voices and faces that defy easy categorization, building community in the process

By Debra Herrick

When artist and UC Santa Barbara professor Kip Fulbeck first heard the word “hapa” in the early 1970s, it came from a cousin.

“I was the only mixed kid in my extended family,” he recalls. “My mother had immigrated from Taiwan with five children, all full-blooded Chinese. I was the outlier. To be told that I was ‘hapa’ — at the time, in Monterey Park, in what’s now called the First Suburban Chinatown — was both clarifying and complicated. My parents’ marriage itself would have been illegal in many parts of the U.S. just years before. Thinking of that now is bizarre by today’s standards, and rightfully so.”

The Hawaiian word “hapa” — a transliteration of “half” — originated in the phrase “hapa haole,” or “half foreigner.” It was used by Native Hawaiians to describe children of Islanders and settlers. Over time, the word migrated to the mainland, becoming a marker of identity and pride for Asian and Pacific Islander Americans of mixed heritage. For Fulbeck, it became the foundation of his life’s work.

In 2001, Fulbeck began photographing people who identified as hapa, pairing their portraits with handwritten responses to a single question: What are you? The results became the groundbreaking exhibition (Japanese American National Museum, 2006) and book “Part Asian, 100% Hapa” (Chronicle Books, 2006). The portraits were stark and unadorned — no jewelry, clothing or props — to strip away assumptions and leave space for self-definition.

“Participants pick their own photograph, handwrite their own statement, and — in the purest form — define themselves,” Fulbeck explains.

The answers ranged from matter-of-fact (“A very littel [sic] boy that has no friends”) to profound reflections on heritage, alienation or belonging.

The project resonated far beyond what Fulbeck expected. “For the original shoots, people just showed up,” he says. “In places like San Francisco or New York, there would already be a line outside before I’d set up. People wanted to be seen, to not be shoved into someone else’s box.”

Nearly 25 years later, Fulbeck has returned to the project with “hapa.me,” now showing at San Diego’s Museum of Us and the Museum of Chinese in America, New York. The exhibition pairs the original portraits with new ones of the same participants, alongside updated identity statements.

“I wasn’t prepared for the overwhelming response,” Fulbeck says. “One person told me, ‘I’ve been waiting 15 years to be part of this.’ That’s when I realized how deeply the work mattered.”

Reconnecting with participants was a challenge. “People had changed emails, moved or even passed away,” he says. “But every single person I found wanted to rejoin. That meant a lot.”

The exhibition also invites new participants and museum visitors to contribute their own photos and handwritten statements, extending the dialogue.

For Kate Clyde, senior director of exhibits at the Museum of Us, the project’s resonance is clear. “The response has been so overwhelmingly positive that our staff started calling Kip’s work ‘the people’s choice award,’” she says. “Visitors instantly connect with it. They see themselves — or their families — reflected in ways they rarely encounter in museums.”

The museum has long engaged in communitydriven conversations around race. Clyde notes that the project creates much-needed space for discussions of multiracial identity, particularly within Asian and Pacific Islander communities. “So much of the American narrative has been framed in Black-and-White terms,” she says. “But people told us they wanted more room for mixed-race stories. Kip’s work provides that.”

Curator Francesca Du Brock, who recently hosted Fulbeck for a residency at the Anchorage Museum in Alaska, sees his approach as both bold and disarming. “He’s very down-to-earth and not afraid to talk about difficult topics,” she says. “That confidence makes others comfortable opening up.”

In Anchorage, Fulbeck has photographed some 90 people, including Native Alaskans, Filipinos, Pacific Islanders and multiracial residents from across the state, as he prepares for an entirely new Alaska-driven version of “The Hapa Project” that will premiere at the Anchorage Museum in 2026. “The diversity here surprised him,” Du Brock says. “We have more than 100 languages spoken in Anchorage schools, and Kip felt it was important to include Native perspectives and broaden the project’s scope.”

The project’s enduring power lies in its pairing of past and present. Visitors see participants as young adults in 2001 and as middle-aged parents or professionals in 2025. “What we have now is both past and present identity statements side by side,” Clyde explains. “It’s a beautiful space to contemplate identity as fluid — something that grows and changes with us.”

For Du Brock, that layered storytelling builds community. “Some people in Anchorage had grown up with the ‘Hapa’ book,” she says. “Meeting Kip and participating in the project was thrilling; it gave them a sense of continuity between their personal lives and a larger cultural narrative.”

At the Museum of Us, visitors can even add their own portraits and statements, joining the dialogue in real time. “It’s not static,” Clyde emphasizes. “This is a living archive of belonging.”

“The Hapa Project” has also been transformative. In the 25 years since it began, he has lived through marriage and divorce, near-death illness and fatherhood. He continues to teach groundbreaking courses on spoken word and race at UCSB, and his artistic practice has expanded through projects like “Perseverance: Japanese Tattoo Tradition in a Modern World,” which, like "The Hapa Project," explores selfexpression and cultural identity through the body. “I’m more grateful now,” he reflects. “I have far less interest in arguing, especially online. What matters is giving people a place to define themselves.”

He also sees the project as a necessary antidote to today’s polarized media environment. “If someone is truly able to tell their story, and another is truly able to hear it, we can start solving our problems,” he says. “Algorithms reward outrage and tribalism. This work is about slowing down, seeing someone, hearing them.”

Standing in front of the portraits, Clyde says, is a disarming experience. “They strip away the usual markers — clothing, jewelry, background. You’re left with the person, their words, their vulnerability. It knocks you slightly off balance in the best way.”

For Fulbeck, that intimacy has always been the point. “It may or may not reach millions,” he says. “But when it does reach someone, it does so in a way that lasts. It’s more than a swipe, click or scroll. It’s about being seen — and realizing you’re not alone.”

View more of Kip's work on his website kipfulbeck.com

us

BY SONIA FERNANDEZ / PHOTO BY MATT PERKO

Ben Halpern hopes he isn’t right, not about this. When the time comes — a scant 25 years from now — the marine ecologist would much rather look back on this era as the moment we decided to band together and avert disaster. It could be remembered as the time we, through collective and consistent action, slowed the accelerating degradation of the ocean and helped prevent the environmental, economic and food security crises that might otherwise have followed.

“We’ll have gotten it wrong in the sense that we fixed it before this happened,” he says. “And I think that that’s possible.”

Alas, for now, we don’t have the luxury of such hindsight. And the data is sobering: In a recent study published in the journal Science, Halpern and fellow scientists at UC Santa Barbara’s National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis (NCEAS) predict that cumulative human impacts on the ocean could double between now and midcentury. In some places they could triple, driven primarily by ocean warming and heavy fishing, but also by other factors such as pollution.

That human impacts on the ocean were increasing was not surprising, given the current age of global warming and its myriad effects, such as habitat loss and sea level rise, Halpern says. What was a surprise is the accelerated rate of change between now and 2050. We’re at a dangerous threshold.

And yet, these threats are hard to fathom in large part because the ocean seems so big, so enduring. For tens of thousands of years, humans have leaned on the ocean for sustenance, for commerce and culture. And for tens of thousands of years, the ocean has been abundant. Its wild environs have yielded food and material, while regulating temperatures, providing oxygen and generally absorbing everything humans could throw at it.

However, below the surface, things are different.

Halpern first got a taste of these unsavory changes early in his career at UCSB, after following a circuitous path toward his discipline. “Growing up in Oregon, the last place I ever thought I would be was Southern California, let alone Santa Barbara, which from Oregon looked like Southern California to me,” he says. He attended the small, liberal arts Carleton College in the Midwest, and followed that up with a stint in Boston — a job at MIT that had nothing to do with oceans, but gave him Friday afternoons “to go do something different.” He spent that extra time at the New England Aquarium, where he fell in love with the institution’s mission of education and conservation.

“They have this center tank that’s three stories tall and something like 50 feet wide, and it’s all a coral reef system. It’s this really amazing, inspired place,” he recalls. “I thought, ‘This is what I want to do. I want to be involved in places and in work that helps save the oceans.’”

With this plan in mind, a 24-year-old Halpern set out to apply to graduate schools, and UCSB’s marine biology graduate program popped up on his radar. It was one of the best in the country, and he was fortunate enough to get accepted to work at UCSB’s Department of Ecology, Evolution, and Marine Biology with coral reef ecologist Professor Robert Warner.

That was obviously the main motivation, he says, but what cinched the deal was that oh-so-California thing that gets everyone who visits Santa Barbara: the weather.

He went on to complete his doctoral work in 2003, then joined NCEAS as a research scientist. It was then a young institute, tasked with the brand-new mission of synthesizing a growing body of disparate, scattered ecological data in search of global patterns and big-picture insights.

“Some oceanographers and atmospheric scientists were trying to build global models of how processes work,” Halpern says. “But from an ecological and a human impacts line of inquiry, this idea of being able to ask things at a global scale was pretty new.” While ecologists around the world had mastered the techniques behind studying local and regional processes and relationships, they were still limited in their ability to examine the entire Earth as a complex series of interlocking ecologies. In bringing scientists and data from all over the world together and leveraging the power of the internet and data science, it was now possible to ask and answer the burning big-picture questions.

“Once you start being able to look at things at a global

scale, all of a sudden your results become relevant to anyone on the planet,” he says. “The idea that you can pull back and see things on our whole planet at once is really both humbling and inspiring at the same time.”

It was with this new perspective that Halpern and collaborators first tackled the question of human impacts on the ocean, taking everything into account, from greenhouse gases in the air to pollution runoff from the land to habitat degradation and overfishing in the waters. The results of the landmark study, published in 2008, were a shock to everyone: Almost half of the world’s oceans were heavily affected by human impacts, and very little, if any of it, was untouched by human activity.

Halpern and team were unprepared for the level of attention their paper would receive. Even before the Feb. 14, 2008, press conference at the annual American Association for the Advancement of Science meeting in Boston to announce their findings, they were bombarded with media requests from all over the world. During the meeting and for days after, they did interview after interview after interview for stories that filled the global news cycle.

“Friends in Africa were hearing the news story during a taxi ride,” Halpern recalled. “Friends in London saw it on the front page of a newspaper. It was just everywhere.”

The paper itself made a huge splash in scientific circles, garnering citation after citation — illustrating the hunger the ecological community had for this global perspective and providing a foundation for a slew of research papers to build upon. Hundreds of papers have cited that study each year since it was published, for a total of 8,177 citations and growing. The work helped put NCEAS on the map, and cemented Halpern’s reputation as a leader in the field.

Fast forward to today, and Halpern, who became the executive director of NCEAS in 2016, continues his work following the effects of global human activity. His projects have unlocked the often difficult-to-discern impacts of and relationships within the global food system; assessed the health of the world’s oceans; mapped areas of biodiversity; and studied the effectiveness of marine protected areas. His research has painted a picture of how we humans, collectively, impact the Earth’s ecological systems.

To fulfill NCEAS’s mission and extract insights and tease out large-scale patterns that can’t be seen from individual

local or regional studies, Halpern leans on the power of inclusion, creating an environment of collaboration, away from the siloed science that is often conducted at research institutions. “I’ve put a lot of effort into building a community that embraces all types of people and all types of thinking, and supports an open mindset approach to do this really powerful research,” he says.

NCEAS is a destination for ecologists and environmental scientists who want to get together, master the data and gain deep understanding of the big issues (and also visit Santa Barbara). In turn, working with NCEAS, the global community of environmental scientists has become more open, collaborative, interdisciplinary and synthetic, changing the culture and practice of environmental science. To bring the momentum of big data team science into the next generation, Halpern has launched AI for the Planet, an initiative that teaches scientists how to harness the power of artificial intelligence to drive insight, while learning how to use it responsibly.

The 2025 paper on the accelerating human impact to the ocean is a continuation of the 2008 paper, using the latest data to get a sense of the speed and trajectory at which these impacts are accumulating. Just like the 2008 work, the more recent results are worse than initially anticipated, with important implications for food security, environmental health and global trade. The world’s coasts, where populations are increasing rapidly relative to inland areas, are expected to see most of the consequences of this human impact, whether it’s the sea level rise that’s claiming oceanfront homes, the diminishing ocean recreation opportunities thanks to habitat loss, or smaller catches due to overfishing. The tropics and the poles, meanwhile, will experience the most rapid rate of change.

For someone whose job it is to monitor the ocean as it bows under the weight of human activity, it can become a little much.

“I definitely have my difficult days,” Halpern says. “I don’t want to sugarcoat the challenges of this work. And it’s not just the ocean; other parts of the environment are experiencing severe impacts as well. So I’m not alone in this challenge, this journey navigating how to stay optimistic and positive despite a lot of evidence otherwise.”

But the oceans are different, he points out. Unlike with terrestrial systems, humans don’t live in the ocean, so while implementing large-scale strategies and solutions still requires a lot of work, doing so is typically easier in the ocean without the complications of property ownership and property rights that can impede land-based environmental projects.

“Also, ocean ecosystems have kind of a built-in resilience in the way that a lot of ocean species have evolved to interact with ocean currents,” Halpern says. Carried by the currents, he explains, most marine species’ larvae are spit out into the ocean and end up dozens to thousands of miles away from where they were born in a dispersal that makes it possible for even severely degraded, barren areas to recover, thanks to newcomers from far away.

The challenge, he says, is actually for humanity to pull back. “If we give the ocean a little space to breathe, I think it’ll come back. I think it’ll recover in a way that is much harder on land.”

So what does it mean for those of us who live near, love and rely upon the ocean? The seeds of the answer lie in the problem itself: If it took a series of relatively small actions in different areas all over the world to coalesce and create the degradation of the ocean, the same can be true for ocean recovery. In addition to targeted, large-scale projects, individuals can also assist in ocean recovery with the choices we make in our daily lives.

“Any individual action can feel so tiny compared to the scale of the problem,” Halpern says, “but if you collectively sum up thousands or millions of people's individual actions, it suddenly becomes a force of change that can make a really big difference at a global scale.”

Don't miss the video interview with Ben on our website.

By Julia Busiek, uC Newsroom

For as long as most of us have been alive, United States scientists have published more research, been cited more often by other scientists, earned more patents and won more Nobel Prizes than any other nation.

All that scientific expertise has helped make the U.S. the most prosperous nation on Earth and led to longer and easier lives here and around the world. But until World War II, the U.S. often sat on the sidelines of scientific progress. With national security on the line, the federal government, through policy and strategic investments, set about turning America into the world leader in science.

Now, amid federal attacks on university research and the government agencies that fund it, America is on the verge of relinquishing its scientific dominance for the first time in eight decades.

To learn more about how we got here, and what could happen next, we called up two experts who’ve dedicated their careers to understanding how America built itself into the most innovative nation on Earth: UC Santa Barbara history professor W. Patrick McCray, who studies science, technology and the environment in the postwar U.S.; and Cathryn Carson, chair of the History Department at UC Berkeley, who studies how 20th century physicists in the U.S. and Europe advanced disciplines including quantum theory and nuclear energy.

University of California: It’s hard to imagine a time when the U.S. wasn’t the global leader in science. But it wasn’t that long ago, was it?

Patrick McCray: Practically since the start of the United States, the federal government has invested in science. But for most of our history, those were investments of a very practical nature. So you have things like coastal surveys, research devoted to fisheries, and programs to map terrain or geology and to promote agriculture.

Through the early part of the 20th century, what we think of as basic science — areas like physics, astronomy, those disciplines that ask these fundamental questions about how things work — the U.S. wasn’t really strong in those areas. Some of it was being done at U.S. universities, mainly funded by philanthropic foundations like the Rockefellers or the Carnegies. But if you’re, say, Robert Oppenheimer studying physics in the 1920s, you’d go off to Europe, like he did, to get your Ph.D.

Cathryn Carson: Up through the 1930s, the idea that the federal government would put any money into either universities or industry science was actually anathema in some quarters. It was seen as inappropriate for the federal government to be tinkering with those parts of civil society by putting money in that served the government's purposes.

That obviously changed at some point, because in recent years the federal government has funded about 40% of basic research in America. What happened?

Carson: World War II completely changed the bargain. As the nature of the threat coming out of Nazi Germany became clear in the late 1930s, the government started scaling up its investments into aeronautics, aerodynamics and chemical engineering, and then into nuclear physics as it burst on the scene, including at Berkeley.

The progress these academic scientists were able to make with a little bit of federal funding got the heads turned around of some leading university-based scientists, who raised the alarm and persuaded President Roosevelt to build up an entire infrastructure of guiding and funding university-based science, purely for the purpose of winning World War II.

So it’s the national emergency of World War II that breaks with all past traditions of keeping the government separate from university or industry science and forges this new compact, this new relationship. The system we have now of federal contracts to universities to do basic research, and the continuing tight relationships and overlaps between university scientists and federal policymakers, was all set up during World War II.

How did the government transition from funding science for the war effort to this long-term commitment to university research?

McCray: The year before President Roosevelt died in 1945, he tasked his science adviser, a man named Vannevar Bush, to look to the future. Bush, who had been at MIT before taking over the management of America’s vast wartime science infrastructure, eventually oversaw the production of this famous report called “Science: the Endless Frontier.” It laid out a blueprint for what would become U.S. science policy in the years and decades following the Second World War.

Did Bush and his successors articulate any specific goals for these policies?

Carson: You might think that the federal government is most interested in applicable research that immediately leads to new weapons or new products. But federal leaders realized that they were actually not just investing in the products of research. They were investing in the people.

McCray: They recognized we needed to have a cadre of trained scientists and engineers and need to keep them fed and paid until the next conflict eventually breaks out. Scientists were seen as a resource to be stockpiled, like steel or oil, and that we can turn to in time of a national emergency.

By the 1960s, the federal government was spending about 2% of U.S. GDP on research and development. How have elected officials made the case for these investments to U.S. taxpayers?

McCray: Bush would say, “We need to water the tree of basic research.” The idea was that tree will grow nice little fruits we can come along and pluck, and those would benefit our health, economy and security.

Those three things — health, economy and national security — were part of the social contract that emerged between scientists and the federal government after the Second World War. The idea was that in some way, the research that the government is funding would contribute to the larger benefit of the nation.

What are some examples of those fruits of basic research?

McCray: I tell my students about Tom Brock, a microbial ecologist in the 1960s who was really interested in the microbes in the hot springs at Yellowstone National Park. The bacteria that he discovered became the key part in a biological technique developed in the 1980s called the polymerase chain reaction, which allows you to amplify sequences of DNA. PCR

was a huge step in the creation of the whole biotech industry, and it was ultimately a critical tool used in 2020 to develop a vaccine for COVID. You can’t predict that path, and the time frame for these government investments paying off is often measured in decades. But Vannevar Bush would have argued that that’s exactly why the federal government should be the one investing in basic science: because industry was never going to think or work that way.

Carson: Silicon Valley was built on microelectronics and aerospace, both funded by the Defense Department. Electronics weren’t initially for consumers. They were for ballistic missiles, jet aircraft, the next generation of radar. All this effort went into building electronics that would serve the military then got turned over to the consumer market in the 1970s and '80s.

Presumably the U.S. wasn’t the only nation that recognized the value of investing in science after World War II?

Carson: No, and in fact, other global powers, including the nations defeated in World War II, started to catch up. Power brokers in Washington in 1948 could never have imagined that the Soviets would get an atomic bomb by 1949. Germany and Japan both made strides in advanced manufacturing in the 1950s. In the 1960s, we had thought we had a semi-permanent lead in semiconductors, but by the 1970s, Japan emerged as a leader in microelectronics.

So that’s how the main concern of government-funded science expanded by the 1970s and 1980s, from maintaining national defense to maintaining U.S. global economic leadership. It became clear that any lead the U.S. might hold — in defense, in electronics, in biotech — has to be constantly defended.

For everyday Americans, why does it matter which nation’s scientists invent the technology or cure the disease, as long as someone somewhere is solving these problems?

Carson: There are two ways to think about that, and they both have to do with maintaining U.S. economic preeminence. One is the “first mover” advantage: Sure, a company from another country could go and commercialize a technology they didn’t originally develop, but they’d be doing that sometime after the originator, so the originator has the chance to build up a lead.

Also, so much of scientific research isn’t about just discoveries, but it's about making an initial discovery better, more marketable or more effective. And so having a system of innovation that can play at all stages, from invention through commercialization of the final product, helps keep domestic companies in the lead over global competitors.

How has the government decided what research is worth funding? Do you see that changing now?

Carson: Up until now, the consensus of the scientific community has governed what got funded, whether it was from high-energy particle physics accelerators to social science or environmental research. We’ve had a self-governing body of scientists, through peer review and through funding panels, who essentially direct government science funding to the places where the scientists thought it would do the most benefit.

I think the consensus that science was a route to national well-being and prosperity was widely shared by people across the political spectrum until very recently. It’s only been the past few years that we’ve seen a rising lack of trust in scientists being self-interested rather than finding truth through coordinating with each other. The surge of distrust for the people who have been steering the enterprise through peer review is pretty frightening, because it then leaves the space for all kinds of ideological interests to come in.

Since January, the federal government has paused or canceled billions in research grants to universities across the country. Now Congress is considering a federal budget for next year that could include cutting some agencies that fund research by as much as half. How could these cuts affect American families and communities?

McCray: This whole history isn’t just about the money, but the ambition behind it. The United States built big particle accelerators, big research vessels, big telescopes. Those were all attractive things for people in other countries to come here to get their degrees, and then maybe stay and start a company that builds U.S. prosperity. One way these cuts could hurt the United States economically is if it makes it so this is no longer a place where people from other countries can come to take advantage of our scientific resources.

But I think the more pernicious effect is to degrade the value of experts and expertise. Science is the production of reliable knowledge about the natural world. What makes it reliable is the fact that experts make this knowledge. This is not to say they are perfect or free from conflicts of interest. But modern science is an infrastructure designed to produce consensus — not certainty — about knowledge. This is what makes it powerful and, at the same time, fragile. The average citizen and politician want certainty but that is not what science is designed to give us.

It’s easy to forget that U.S. leadership isn’t some fixed, unchanging feature of the scientific landscape. It has a history, it’s developed and changed over time, and like any other system, it can be degraded. And sadly, that’s what’s happening now. And it’s going to be hard to build that system back, especially since, at least in this country, it took decades to create.

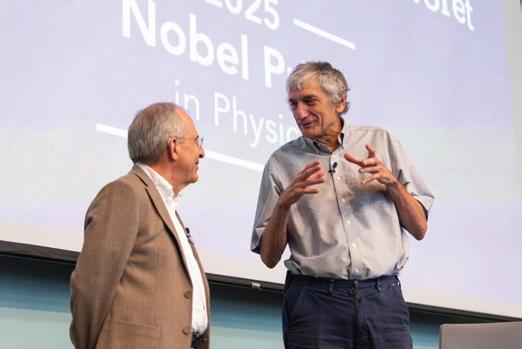

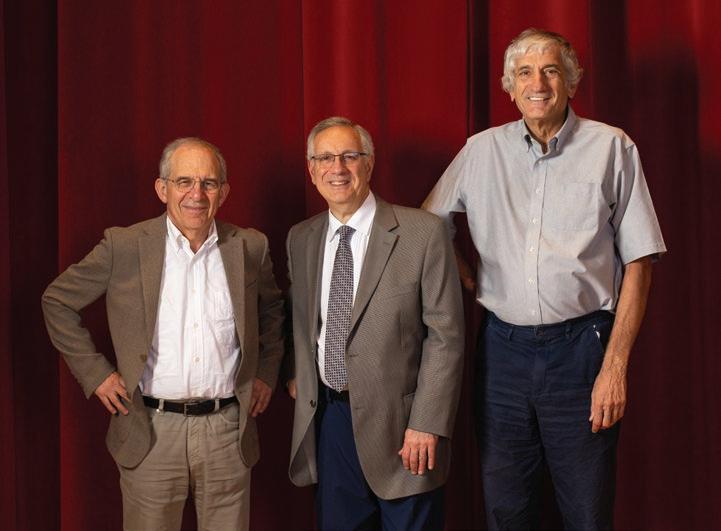

UCSB professors Michel Devoret and John Martinis win the 2025 Nobel Prize in Physics for discoveries in quantum physics

BY SONIA FERNANDEZ PHOTOS BY MATT PERKO

Professor John Martinis slept through the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences’ announcement of his Nobel Prize in Physics, and the subsequent deluge of phone calls to his Santa Barbara home in the wee hours on Oct 7, 2025.

“My wife was very kind to me and didn’t wake me up for a couple of hours because she knows that I need my sleep,” Martinis says. Eventually, though, the spate of calls did awaken him. That, and the reporter who showed up to their house at 6 a.m.

Similarly, his colleague, friend and fellow Nobel physics prize recipient Professor Michel Devoret noticed a flood of messages on his phone and computer throughout the morning and “thought it was a joke,” he would later say in an interview.

“I forgot October was Nobel Prize month,” he says. It wasn’t until he called his daughter in Paris that he ascertained that yes, he had actually won the prize.

Fortunately, by the time the pair realized they won — along with their erstwhile adviser, Professor John Clarke at UC Berkeley — they had had enough sleep to take on the whirlwind of interviews, calls and congratulations from family, friends, colleagues and former students.

Devoret and Martinis have brought the number of UC Santa Barbara faculty Nobel winners to eight since 1998; alumna Carol Greider, now a professor of biology at UC Santa Cruz, also received the 2009 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for work she accomplished at UC Berkeley.

“What a profound thrill, and a moment of exceptional pride for our campus, to congratulate our UC Santa Barbara professors John Martinis and Michel Devoret on winning this year’s Nobel Prize in Physics, alongside UC Berkeley’s John Clarke,” says UCSB Chancellor Dennis Assanis. Their wins, along with that of Cal’s Omar M. Yaghi, for chemistry, and UC San Diego alum Frederick J. Ramsdell, for physiology or medicine, bring the total number of Nobel laureates affiliated with the University of California to 49 — the most of any institution in history.

“These awards are not only great honors,” remarks UC President James Milliken, “they are tangible evidence of the work happening across the University of California every day to expand knowledge, test the boundaries of science and conduct research that improves our lives. I’m proud to see their work recognized.”

Devoret, Martinis and Clarke together were cited “for the discovery of macroscopic quantum mechanical tunnelling and energy quantisation in an electric circuit,” and lauded by the Swedish Royal Academy of Sciences for revealing “quantum physics in action.”

Little did the trio know their series of fundamental physics experiments 40 years ago would not only usher in an era of quantum science and engineering development, but also be recognized with the world’s most prestigious science prize. The application of their work to quantum processing and quantum information is undeniable, opening the door to breakthroughs in other realms such as cryptography and quantum computing.

It’s a long way from 1984 and 1985, when Devoret and Martinis were a postdoctoral researcher and a graduate student, respectively, in Clarke’s lab, seeking to answer a fundamental physics question: Do macroscopic variables obey quantum theory?

“Traditionally, and I still hear it often, quantum mechanics is the physics of small things, like atoms,” Martinis explains. “Normally, we think of how atoms work and how molecules bind together to form molecules.” The prevailing thought had been that quantum mechanical effects disappear at scales larger than atomic, in favor of classical physics.

However, theoretical research performed a few years earlier by Anthony Leggett explored the consequences of quantum mechanics being applied to collective variables inside a device spanning a very large number of atoms. This type of engineerable system could serve as a testbed for quantum mechanics.

“The idea that Tony Leggett had to test quantum mechanics was met with extremely strong criticism and skepticism,” Devoret recalls. “It was not the kind of thing you should be doing.”

But it was too enticing of a question for the trio to pass up. Armed with a burning curiosity, they turned to the Josephson effect. A phenomenon predicted in 1962 by theorist Brian Josephson, this effect occurs in a setup of two superconductors separated by a thin layer of insulating material, when electrons tunnel through the barrier from one superconducting layer to the other. The so-called Josephson junction would become a crucial part of their work.

At this frontier of new physics is where the gears began to turn. Devoret, Martinis and Clarke all fondly remember this time as an era of intense creativity, camaraderie and synergy among their diverse personalities and areas of expertise. And it led to groundbreaking problem solving as they devised a platform upon which to see if quantum effects — in this case, the collective quantum behavior of the current through the junction — could be observed via their cryogenic Josephson junction.

“It was marvelous,” says Devoret, who used his experience with cryogenics to design and build the dilution refrigerator that achieved the ultra-low temperatures required. Martinis would later credit his work with Devoret on the refrigerator with making him “fearless” to build the powerful and highly sensitive equipment needed to enable quantum mechanical effects in his later work.

Observing quantum tunneling on the macroscale had been attempted in a few experiments already, but Clarke, ever the adviser, challenged the junior researchers to find a way to make this experiment new, different and better.

“There had been some experiments, but they weren’t very complete and convincing,” Martinis recalls. “We figured out that we could measure the parameters entering in the theory more accurately than what had been done before.”

Their experiment afforded them the ability to finely control and tune their platform and precisely measure the phenomena that occurred when they passed a current through it. Importantly, while previous experiments involved only a few particles, the ones conducted by Clarke, Devoret and Martinis involved billions of electrons, bound together in pairs — “Cooper pairs” — that form when they are in a superconducting state.

The result? Evidence that the state of the circuit switched from being superconducting to dissipative, causing a voltage spike that appears across the junction. Additionally, the future laureates in their experiment were able to demonstrate the quantized energy states that define quantum mechanics.

“We had an oscilloscope and there was a trace on it that indicated when the junction switched (between voltage and superconducting states),” Martinis says. “I vividly remember at one point seeing this trace and seeing three dots on that trace.”

Classically, he explains, the graphical representation of voltage that the oscilloscope provides typically represents the change in voltage as a “smosh of a line.” However, the appearance of three dots indicates that the system absorbs or emits only certain specific amounts — “quanta” — of energy, true to prediction.

“When you see three little dots there, then you’re really seeing the quantum mechanics.”

In the decades since the laureates’ seminal experiments, quantum researchers everywhere grabbed the baton and ran with it, buoyed by the proven ability to see quantum mechanics on a macroscopic scale, in a controllable electronic setup.

“In retrospect after the experiment, what was clear was that we had made the first artificial atoms,” Devoret says. “These ‘atoms’ don’t exist in the natural world, but they are just as useful as atoms.”

The ability to generate, probe and exploit macroscopic quantum behaviors would open the door to advanced technologies, from quantum information processors to quantum sensors that enable highly precise measurement, to the highly anticipated quantum computers that will be able to rapidly solve enormous, complex practical problems. All these applications and more are part of multibillion-dollar global industries fueled by quantum research — and proof that fundamental science is a powerful activity for future benefits to humanity, economy and society.

After those fateful experiments, Martinis conducted his postdoctoral work at CEA Paris-Saclay, where Devoret had started his own research group. From there, he returned to the U.S. to work at the National Institute of Standards and Technology, while Devoret returned to the country to join the faculty at Yale University in 2002, where he and his team developed architectures for qubits (“quantum bits”) based on superconducting circuits and Josephson junctions.

In 2004, Martinis joined the UCSB faculty and, later, the emerging Google Quantum AI lab in a partnership between the tech giant and the university. In 2019, he and his team announced quantum supremacy in the form of a 53 entangled qubit system dubbed “Sycamore.” The next year he resigned from Google and spent a brief stint at Australian startup Silicon Quantum Computing before returning to the U.S. to start his own company, Qolab, to build a utility-scale quantum computer.

After teaching and conducting research at Yale for more than two decades, where he and his team performed the first quantum error correction beyond break-even, Devoret was named Chief Scientist for Hardware at Google Quantum AI in 2023. The next year, he retired from Yale and became a professor of physics at UCSB, where he continues to conduct research with and teach members of the next generation of quantum computing experts.

For Devoret and Martinis, the work continues to refine and develop quantum technology based on the superconducting circuits to, among other things, develop a practicable quantum computer — one that can be set to solving problems considered intractable for classical computers in a variety of fields, from drug discovery to encryption to artificial intelligence and machine learning. For that, according to the pair, work must be done to scale up the number of qubits (the basic unit of information for a quantum computer, analogous to classical “bits”) and make them more robust and fault-tolerant.

“It took all of these people working together to develop the science that made this possible,” Martinis says. “It was really all this basic research we all did for decades that enabled this to happen. So hopefully, in not too many years, we can talk about the useful quantum computer we have built and that’s the goal for the future.”

By Harrison Tasoff

So, why did they win? For their discovery of macroscopic quantum mechanical tunneling and energy quantization in an electric circuit — a finding that, in layman’s terms, showed that the strange rules of the quantum world can play out on a scale large enough to see and measure in the lab.

In the quantum world, particles are waves and waves are particles. So if a particle gets close enough to a barrier, its wavefunction will extend through the barrier. In other words, there’s a slight chance that, when measured, the particle will show up on the other side.

Tunneling is far from a theoretical oddity. Scientists harness it in scanning tunneling microscopes to image individual atoms; it can trigger mutations in DNA; and it plays a vital role in nuclear fission — the process that powers the sun and atomic reactors alike.

Smaller objects have longer wavelengths, which makes tunneling more likely. That’s why a racquetball can’t tunnel through the court wall. But, in the 1980s, John Clarke, Michel Devoret and John Martinis demonstrated this phenomenon in an object roughly a centimeter in size — proving the eerie behavior of the quantum world could extend into the macroscopic realm.

That insight — that quantum behavior could appear in something visible to the naked eye — pointed back to one of the earliest ideas in modern physics.

Decades earlier, in 1901, physicist Max Planck first proposed that energy may come in specific, discrete units. These “quanta” became the foundation and namesake for quantum mechanics. Over the century that followed, scientists discovered that many aspects of the universe are quantized, though this fine granularity is smoothed over at human scales, like a mosaic seen from across the room.

By demonstrating quantization in a human-scale object, Clarke, Devoret and Martinis showed that this underlying aspect of the universe extends well beyond the atomic level.

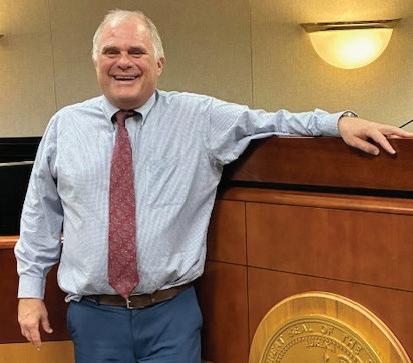

Chancellor Dennis Assanis brings global experience, academic excellence and a spirit of innovation to guide UC Santa Barbara into its next era of growth and discovery

WITH A DISTINGUISHED RECORD OF LEADERSHIP and innovation in higher education, Chancellor Dennis Assanis stepped into his role as the sixth leader of UC Santa Barbara. An accomplished scholar and engineer — and an elected member of the National Academy of Engineering — Chancellor Assanis brings a deep commitment to academic excellence, collaboration and transformative research.

In his first months on campus, he has focused on getting to know the Gaucho community — meeting students, faculty, staff and local stakeholders to listen, learn and build connections.

Before joining UCSB, he served as president of the University of Delaware, where he expanded research, strengthened interdisciplinary programs and fostered a culture of innovation. Born and educated in Greece and the United Kingdom, with advanced degrees from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Chancellor Assanis now looks ahead to advancing UCSB’s mission of teaching, research and public service — and to inspiring the next generation of Gauchos.

Energy filled the Thunderdome as Chancellor Dennis Assanis snapped a selfie with new Gauchos during UC Santa Barbara’s first-ever Gaucho Welcome rally — a spirited kickoff to Week of Welcome, an annual tradition that celebrates the start of the academic year with activities and events designed to build community and Gaucho pride.

Chancellor Assanis and his wife, Eleni, meet students during a campus tour, part of their first months connecting with the Gaucho community. Tours are among many events during UCSB’s Week of Welcome, which give new students a chance to explore campus landmarks, learn traditions and meet university leaders.

The Assanises join Kelly Barsky, the Arnhold Director of Athletics, on the field at Harder Stadium during a UCSB men’s soccer match against Grand Canyon University. Before kickoff, they received the Golden Scarf — a campus tradition welcoming them to the Gaucho community.

Joining the action during Move-In Weekend, Chancellor Assanis and Eleni welcome new students and families to campus. The annual event marks the start of the Gaucho journey and reflects UCSB’s commitment to a safe, supportive and memorable beginning to the academic year.

Chancellor Assanis, center, joins Nobel laureates Michel Devoret, at left, and John Martinis at a campus colloquium celebrating the pair’s 2025 Nobel Prize in Physics. The event honored Devoret and Martinis for their pioneering quantum research, recognized by the Nobel Committee for laying the groundwork for nextgeneration quantum technology.

At the fall New Faculty Orientation, scholars and educators beginning their UCSB journey meet with Chancellor Assanis and campus leaders to connect, share ideas and join the university’s vibrant community of learning and discovery. The annual event helps new faculty navigate campus life and access resources for success.

As Chancellor Assanis meets with community members across campus, he gains insight into the people, programs and partnerships that drive the university’s success. Collaborating and learning from faculty, staff, students and trustees alike, he joins a community whose innovation and dedication make waves far beyond the shoreline — shaping industries, inspiring change and earning recognition around the world.

The Assanises join State Senator Monique Limón (second from right) at an investiture event for Leah Stokes (right), the newly minted Anton Vonk Associate Professor of Environmental Politics.