February, 2026

PILOTSTUDY PROMOTINGDEMOCRACY THROUGHLOCALENGAGEMENT: REMOVINGBARRIERSTO IMMIGRANTS’INVOLVEMENT

INCIVICINITIATIVES

February, 2026

PILOTSTUDY PROMOTINGDEMOCRACY THROUGHLOCALENGAGEMENT: REMOVINGBARRIERSTO IMMIGRANTS’INVOLVEMENT

INCIVICINITIATIVES

Barriers and Solutions

Executive Summary

Introduction

Background

Methods Used

Preliminary Research Results

Connections to Long Beach

Sources of Support and Vulnerability

Barriers to Civic Engagement

Overcoming Barriers

Future Visions

Recommendations and Next Steps

Notes and References

Appendices

Feelings of Intimidation and Lack of Trust

Knowledge Gaps Adopt TraumaInformed Practices Codesign Processes

Practical Issues

At a time of heightened anti-immigrant sentiment at the national level, how do immigrant residents engage with city-level officials and services? Through a research-to-action planning grant from the Haynes Foundation, a team of researchers from the University of California, Irvine, and three community organizations – the Filipino Migrant Center, Latinos in Action California, and United Cambodian Community of Long Beach – carried out pilot research on this question in Long Beach, California, a highly diverse city committed to supporting immigrant residents. From January to June 2025, research team members met regularly to design a pilot study that would serve as a basis for a full-scale research project, and from July to December, they carried out the pilot study and wrote up the results. During the design phase of the pilot study, the research team consulted with staff in City Council Districts 1 and 6 For the pilot, in-depth interviews were conducted with 24 immigrant residents of Long Beach who identify as Filipino, Cambodian, or Latinx The interview sample was diverse in terms of gender identity, age, occupation, and languages spoken Interviews yielded approximately 500 single-spaced pages of transcripts with detailed accounts of study participants’ connections to Long Beach, concerns, experiences of city engagement, and hopes for the future. Transcripts were coded for themes and then sorted for a detailed analysis.

Our research documented the harm that immigrant residents are experiencing due to intensified federal immigration enforcement The participants in our study were people who had deep and varied connections to Long Beach Many moved to Long Beach because of the city’s diversity and subsequently raised families in the city Immigrant residents had multiple sources of support, such as family, community organizations, and religious institutions, that helped them cope with vulnerabilities that are common in immigrant communities, such as the traumas that led their families to immigrate, financial insecurity, and cultural and language differences. Yet study participants reported increased fear and insecurity due to the risk of Immigration and Customs Enforcement raids Some participants reported staying home whenever possible, avoiding government buildings or public settings such as parks, and relying on relatives for groceries

Our analysis revealed that this enforcement climate increased barriers to immigrant residents’ engagement in city services and processes. We identified three key barriers to immigrant incorporation:

1 Feelings of Intimidation and Lack of Trust: Numerous study participants reported that they were raised to avoid government institutions, and that the current enforcement context exacerbated this fear

2 Knowledge Gaps: Some participants did not know their representatives, were unaware that they could make public comment at City Council meetings, and did not feel knowledgeable about city resources. The current enforcement climate makes them less likely to seek out such information.

3.Practical Issues: Some interviewees stated that transportation challenges, work schedules, childcare responsibilities, and language barriers prevented them from accessing city institutions and processes These practical issues have intensified due to the impacts of enforcement activities

Analyzing instances when study participants successfully overcame barriers as well as their recommendations for future improvements made it possible to identify three strategies to reduce barriers. Identifying these strategies provides feedback on approaches that our study participants considered valuable in promoting inclusion:

Adopt Trauma-Informed Practices: Acknowledge and express empathy for the fact that immigrant residents and other members of the public may have experienced traumas; welcome and honor their contributions

Strengthen Communication Pathways: Support immigrant residents through trusted community institutions (eg, in neighborhoods, community organizations, schools); use flyers to reach those who may not be digitally active. Codesign Processes: Work with immigrant residents and immigrant-serving organizations to design processes that overcome practical challenges.

The barriers to local civic engagement identified in this report underscore the need for additional community-based research that more thoroughly examines the roots of these barriers and solutions to overcoming them In response to these findings, the study team hopes to seek additional funding to expand the project Doing so will help the team assess the prevalence of certain barriers and how to mitigate or overcome them. Additionally, a more expansive study will enable the team to examine how the City of Long Beach can serve as a blueprint for immigrant inclusion in other culturally rich and diverse cities, particularly during a period of adversity.

In this time of heightened immigration enforcement at the federal level, how do residents of immigrant backgrounds interact with city-level officials and processes?

UC Irvine researchers and Long Beach community organizations explored this question through a research-to-action planning grant from the Haynes Foundation’s “Democracy and Good Governance” program, which funds research on topics that promote democratic participation and improve governance in Southern California Research-to-action planning grants are meant to fund the design and piloting of research that involves impacted communities, speaks to policy makers, and yields actionable results In conversation with Long Beach Council Districts 1 and 6, the Filipino Migrant Center, Latinos in Action California, and the United Cambodian Community of Long Beach collaborated with UC Irvine researchers Professor Susan Coutin and doctoral student Jahaira Pacheco to develop and pilot a study of barriers to immigrant residents’ civic engagement and strategies to overcome these barriers Through in-depth interviews with 24 Long Beach residents of Cambodian, Filipino and Latinx background, the research team found that long-standing barriers such as not knowing how to share concerns or feeling intimidated by government agencies were exacerbated by the current heightened federal immigration enforcement climate. Recommendations to overcome barriers include adopting trauma-informed practices, strengthening communication pathways, and co-designing processes. This report details the research methodology, preliminary results, and plans for continued research.

Immigrant communities can be excluded from democratic participation by national political rhetoric that stokes government distrust. Immigration is typically thought of as a national policy area, but cities and counties are the places where people live and work, and therefore have great potential to promote immigrant integration. Local governments have increasingly been drawn into immigration policy-making, whether through directing police to collaborate in immigration enforcement or conversely, by adopting sanctuary policies to protect their residents Moreover, even lawful permanent residents and naturalized US citizens whose status theoretically reduces systemic exclusion may have family members impacted by national policies, discouraging their democratic participation

The lived experiences people have in their home countries matter in how they navigate life in the United States Lack of trust in government institutions can lead immigrants to practice “system avoidance” and “selective engagement,” which prevents them from accessing city services and participating in democratic processes Studies have found that families in which at least one person is undocumented are especially likely to avoid government institutions. Not only are immigrant residents who avoid institutions disempowered but, in addition, local communities are deprived of the good ideas that they could contribute to local governance.

Promoting immigrants’ engagement with local institutions is especially important in the Los Angeles region, which has the second highest number of foreign-born residents in the world, at 4,421,000 individuals. The foreign-born residents in the Los Angeles region are highly diverse. 52% are US citizens, 24% are lawful permanent residents, 21% are undocumented, and 3% have temporary legal status. As they settle in Southern California, immigrants – especially new arrivals – are more likely to have low-income jobs, face housing insecurity, experience labor abuses, and speak limited English These circumstances may shape how they interact with local governments Those who are undocumented or who have undocumented relatives may fear that their information will be shared with federal authorities Lack of transportation, financial challenges (such as having to work multiple jobs) or lack of childcare can make it difficult for immigrants to participate in local initiatives Those who have been traumatized or who had negative experiences with governments in their countries of origin may distrust governments here Language barriers can further limit access Therefore, identifying specific barriers to engagement, as well as grass-roots strategies to make city institutions and processes more inclusive will foster good governance and promote democracy

These issues are especially germane to Long Beach. According to a Long Beach city report, 26.6% of the Long Beach population is made up of immigrants, of whom 48.6% have naturalized, 37.5% are potentially eligible for naturalization, 24% are undocumented, and the remainder have other temporary statuses. The most prevalent countries of origin for immigrants in Long Beach are Mexico (475%), the Philippines (106%), and Cambodia (78%) These immigrant communities have faced language barriers, the trauma of leaving behind their homelands, the need to acclimate to a foreign culture, and challenges associated with immigration status Cambodians entered the United States as refugees fleeing the Khmer Rouge during the 1970s, and have been joined by more recently arriving relatives Long Beach is home to Cambodia Town, the largest Cambodian community outside of Cambodia Filipinos immigrated to the United States as US nationals during the 1920s and 1930s, and continued migrating during the 1980s and 1990s for job opportunities in Southern California Migration from the Philippines continues to this day A sizeable Filipino community settled in West Long Beach, unofficially known as “Little Manila” The Latinx community in Long Beach is made up of immigrants from Mexico, Central America, Venezuela, and other countries. Many arrived in the 2000s, long after the last major regularization program in 1986. These three communities have produced local leaders and thriving businesses, but also continue to face barriers in engaging with city government.

To develop and pilot research regarding barriers to immigrants’ civic engagement and strategies for overcoming these barriers, UCI researchers collaborated with three community-based organizations in Long Beach: the Filipino Migrant Center, Latinos in Action California, and the United Cambodian Community of Long Beach To elicit community members’ accounts of their own experiences, it was decided that indepth semi-structured interviews would be used as the primary method for pilot research. This approach enabled study participants to identify the key issues of concern, instead of using categories that were pre-determined by researchers. As well, working collaboratively built trust with participants. To protect participants’ privacy, no identifiable data was collected, and, in compensation for their time, each study participant was given $50 in cash.

Beginning in February 2025, a research team made up of two UCI researchers and six community members – two from each of the participating organizations – met biweekly to refine the research question, develop an interview guide, discuss research ethics, and plan participant recruitment A key approach that the research team adopted from the outset was to employ trauma-based methods Drawing on their collective expertise providing community-based services as well as on best practices identified in the published literature, researchers strove to promote healing and empowerment, treat research participants as whole persons, ensure that interview questions were sensitive, respect participants’ boundaries, pause if necessary, and carry out interviews in a calm and private setting In designing the pilot study, research team members consulted with the staff of Council Districts 1 and 6 as well as with the leadership of FMC, LIACA, and UCC

From July to November 2025, research team members interviewed 24 Long Beach residents of Cambodian, Filipino, and Latinx backgrounds. To preserve confidentiality, we identify participants by pseudonyms that they chose during interviews. Participants were diverse in language, age, race, ethnicity, gender identity, and occupation. All were current residents of Long Beach who identified as being of an immigrant background, whether due to having moved to the United States or being the children of immigrants. Interviews lasted 1-2 hours and covered settling in Long Beach, engagement with local processes and institutions, challenges, sources of support, and suggestions for improvement. Those who preferred to do so were able to speak Spanish, Khmer, or Tagalog during the interview. Interviews were transcribed and, if necessary, translated into English by research team members, resulting in approximately 500 single-spaced pages of transcribed text Research team members carried out a preliminary analysis by open-coding interviews, identifying key themes, and sorting coded material for a more in-depth analysis Research team members also drew on their expertise as affiliates of community organizations with a long history of working with immigrant residents of Long Beach

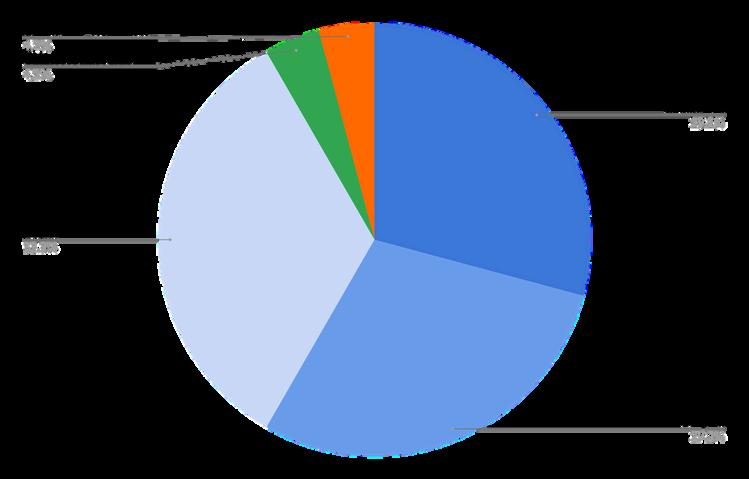

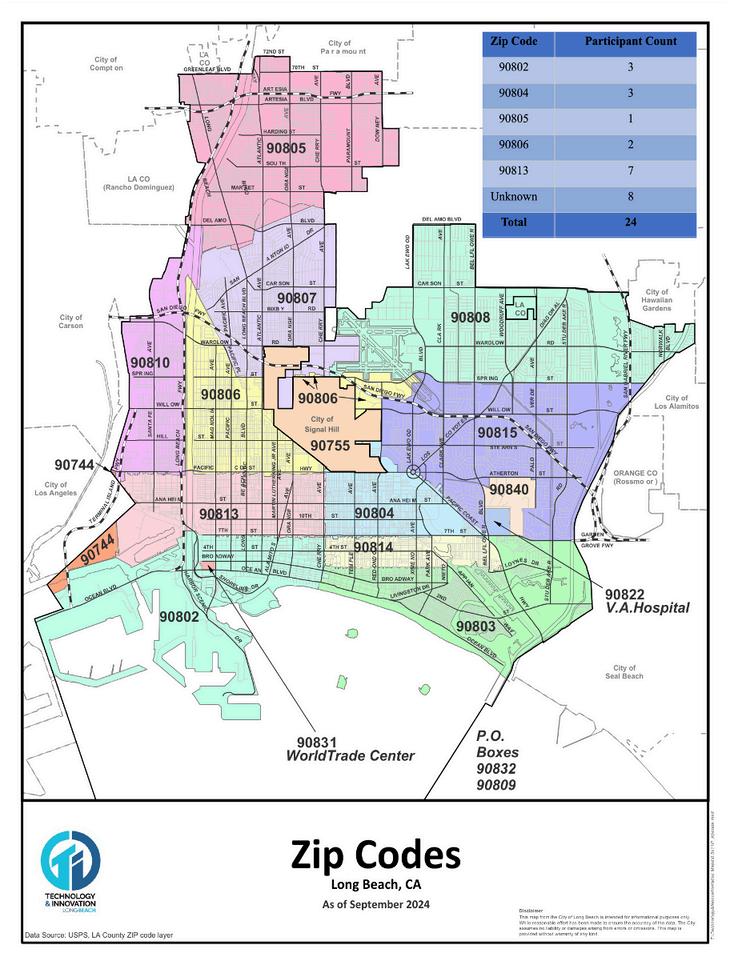

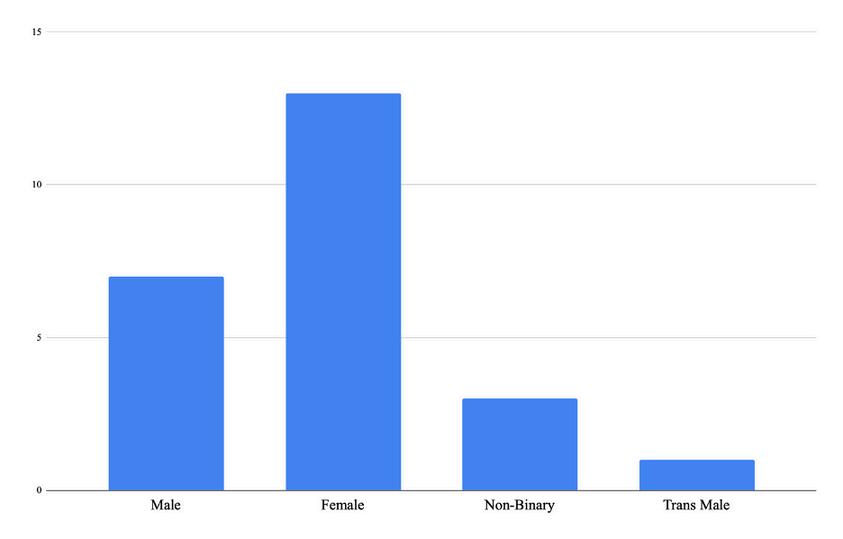

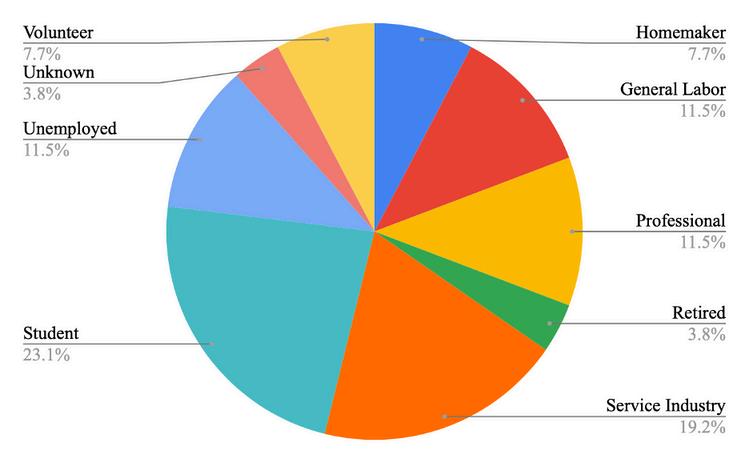

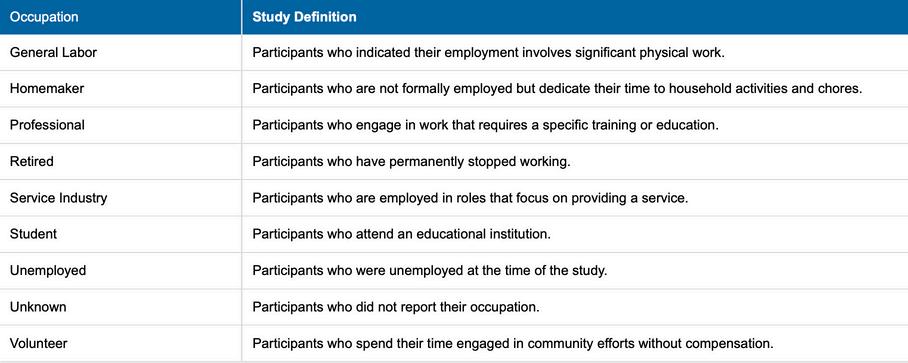

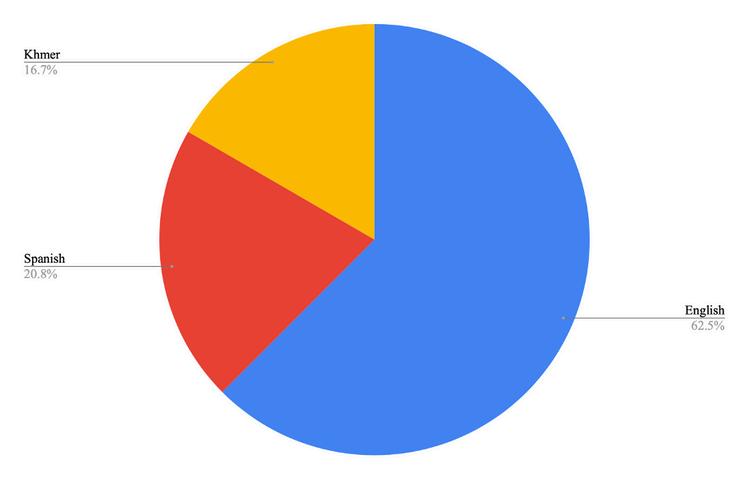

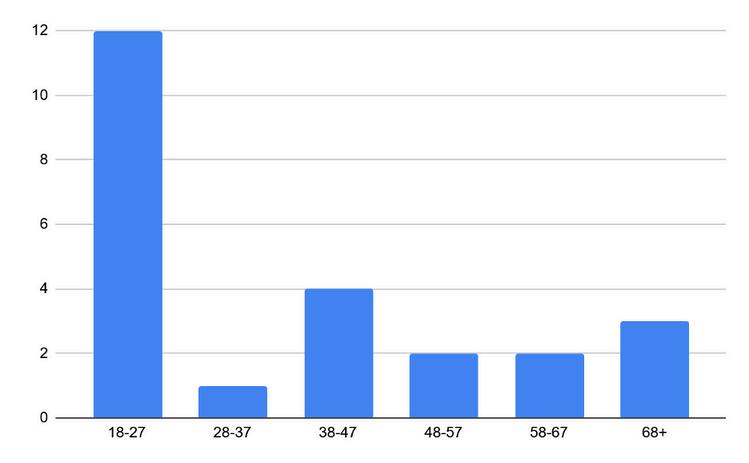

The following tables and figures display demographic characteristics of the study participants. Participants came roughly equally from Cambodian, Filipino, and Latinx communities, with two participants of mixed ethnicity (Cambodian-Vietnamese and Cambodian-Chinese) (see Figure 1). Participants lived in multiple zip codes within Long Beach. Eight participants did not disclose their zip codes, seven live in 90813, three each in 90802 and 90804, two in 90806, and one in 90805 (see Figure 2). A little over half of the sample (thirteen people) identified as female, seven as male, three as gender non-binary, and one as a trans male (see Figure 3) Occupations varied, with study participants working in the service industry (192%), as professionals (115%), or in general labor (115%), with 23% of participants going to school, and the remainder being volunteers, homemakers, retired, or unemployed (see Figure 4; note that some individuals had multiple occupations so these percentages total more than 100%) Most interviews – 625% – were conducted in English, with 208% of participants opting for Spanish and 167% in Khmer; no one requested an interview in Tagalog, as the Tagalog-speaking study participants were bilingual and opted to do the interviews in English (see Figure 5) The sample skewed young, with 12 participants who were between 18-27 Overall, participants ranged in age from 18 to 85, with a median age of 39 (see Figure 6) We did not collect information about legal status given the sensitivity of this topic, however, participants shared sufficient information for us to conclude that the sample included US citizens, lawful permanent residents, individuals with temporary status, and those who were undocumented.

Figure2.ParticipantZipCodeCount

Source: City of Long Beach 2024 “Zip Codes”

Figure3.ParticipantGenderDistribution

Figure4.ParticipantOccupationComposition15

Figure 4: Note that some individuals had multiple occupations so these percentages total more than 100%

Figure5.DistributionofInterviewLanguages

Figure6.ParticipantAgeDistribution

Interviewees’ motivations for participating in the study varied. The most commonly expressed motivation was the desire to improve the lives of immigrant residents in Long Beach who face similar hardships Alice, a Filipino student, told us, “I just feel like with this study, hopefully, more people can realize how difficult it is to actually just get basic needs as an immigrant, especially if you’re undocumented,” while Clara, a Latinx resident, commented, “when you said that it was to improve the service of Long Beach, I was interested in supporting that.” Equally significant, participants wanted to be interviewed to share their story. Another participant, who was of Cambodian-Vietnamese descent, explained, “It’s not a story that I feel is represented very often. So, the more I get to tell it, the more I feel I can keep my parents’ stories alive . ” Likewise, Johng, a Filipino resident, stressed, “just putting your voice out there is important, especially now that so many people are emboldened to silence your voice,” while Om Srey, a Cambodian elder, wanted to “let people know about living in Cambodia and let people know that it is important, that people that came to the United States, [and] what for” Other motivations included supporting the research team, learning about the interview process, and processing their own family’s history by talking about it Our sense was that interview participants felt empowered to share their stories and contribute to positive change, especially at a moment when they felt that their communities were being threatened

Just putting your voice out there is important, especially now that so many people are emboldened to silence your voice.

The in-depth interviews carried out for this project provide insight into the barriers to civic engagement that immigrant residents of Long Beach experience, as well as ways to overcome these barriers Across the 24 interviews that we conducted, there were significant themes and points of commonality Study participants had strong and multifaceted connections to Long Beach Study participants’ experiences were shaped not only by their background as immigrants, but also by gender identity, social class, occupation, age, and other factors. Their backgrounds gave them sources of support, such as language skills and family ties, but also exacerbated certain barriers. Our analysis details these connections, sources of support, forms of vulnerability, key barriers, and recommendations for overcoming barriers. We also share participants’ visions for the ideal city that they would like to see in the future Significantly, the community members we interviewed saw participating in this study as a means of working toward this ideal Study participants had deep and varied connections to the City of Long Beach Their families journeyed to the United States in search of safety, educational opportunities, and a better life These familial histories were reflected in the challenges, opportunities, and visions for Long Beach that participants described Participants’ families were drawn to Long Beach by the presence of sizeable Cambodian, Filipino, and Latinx communities, as well as by employment and educational opportunities Keo, who was born in the United States to parents who immigrated from Cambodia, moved to Long Beach as an adult He commented, “I was so surprised to see so many Southeast Asians, so many Cambodians, to feel at home, in a sense, to feel more rooted in my culture and my community. And it was inspiring, it was feeling very wholesome, and

I was so surprised to see so many Southeast Asians, so many Cambodians, to feel at home, in a sense, to feel more rooted in my culture and my community.

just very sentimental for me to come out here and to see the Cambodian community and to know that something like this exists.” Johng, who was born in the Philippines and immigrated to the Unites States in his twenties, shared that “the Westside is appealing because I see a lot of Filipinos there,” while Haze, who immigrated to the United States as a teenager, stated, “On the Westside, we would see a lot of Filipinos where they’re also recently migrated to the US, and they’re still very connected to their families back home, very connected to their culture So, I think it helped me transition a little better I wouldn’t say it was easy, but it also was able to help me continue to appreciate being who I am, like more connected to the Philippines” Mandy, the daughter of parents who immigrated to the United States from Mexico, appreciated the opportunity to be around Spanish speakers in Long Beach Mandy described living in Long Beach as “almost like a privilege in a way Because every time that I would visit different cities outside of Long Beach, I would see that it’s majority English-speakers, and not a lot of people that would look like me So, I felt like if I were to grow up in that situation, I would have felt a lot more left out Compared to here” Study participants also commented on other facets of diversity, such as being queer or trans and being able to find community in Long Beach.

Study participants appreciated the diversity of Long Beach not only because it connected them to those who shared their own background but also because they were exposed to others, an experience that they felt promoted open-mindedness. To again quote Keo, “I think it’s a melting pot of cultures and diversity and I think that’s beautiful too, and that Long Beach does promote creativeness and diversity and yes, there are parts that might not be as diverse as others, but I think in a sense overall Long Beach is one of the more accepting, open, diverse cities.” Johng agreed, describing Long Beach as “literally like the utopia of different cultures,” while Mandy remarked, “There’s Latinos, there’s Cambodians, there’s African Americans It’s just ¬ a lot of different types of communities living here So, it [makes] you very openminded to the people you are likely to encounter” Morena, who immigrated to the United States from Mexico as an adult, described how volunteering at her children’s school enabled her to transcend language differences:

“I spent time with people who were Hindu, people from the West, from China and Japan, and I don’t know how, they didn’t speak Spanish and I didn’t speak English much less their maternal languages, but even so, when we went to the [volunteer] room … they understood me and we would laugh, I hugged them, they hugged me…. And always, I’ve liked that part of the culture that is here, the culture that you can share despite not speaking the same language, the physical expressions, your smile, a hug, and making hand gestures, and they respond as well with hand gestures. And it is beautiful.”

Most interviewees also had deep connections to Long Beach, such as living in the city for decades, having children here or family ties to other households, belonging to churches or temples, going to school in Long Beach, working in Long Beach, and volunteering with community groups Alice, who moved to the United States from the Philippines as a toddler, described these deep ties: “I grew up in Long Beach, I've moved around Long Beach, I've gone to school in Long Beach, … I lived my whole life here,” while Patricia, who was also from the Philippines, moved to the area to attend college and then “stayed here because I actually found like a community here.” Not surprisingly, since they agreed to participate in a study, the immigrant residents with whom we spoke contributed their time to volunteer activities. Claudia, who had immigrated to the United States from Mexico in 2003 and who was raising a family in Long Beach, described her volunteer work donating back packs with school supplies to Long Beach students: “I feel like I’m doing something for my community. I feel generous, I feel abundant, I feel my heart full because that person possibly doesn’t have money to buy a backpack, much less a notebook or pencil Seeing the smiles of children, walking away happy I felt like, ‘Oh, wow!’ Very happy” Participants also appreciated some of the amenities that make Long Beach unique, such as the view from Signal Hill, the Museum of Latin American Art, the Grand Prix, the Queen Mary, and the canal area in Naples

I feel generous, I feel abundant, I feel my heart full because that person possibly doesn’t have money to buy a backpack, much less a notebook or pencil.

Their deep roots in Long Beach generated an emotional connection for many study participants Mary, who came to the United States from Mexico as a teenager during the 1990s, put it simply: “I love Long Beach,” while Tim commented that due to the existence of Cambodia Town in Long Beach, “I couldn’t see myself living in any other city” While most of our study participants had strong ties to Long Beach, we also interviewed “newcomers” who had immigrated to the United States recently, or who chose to live in Long Beach for convenience S H, who immigrated to the United States from Cambodia recently and who moved to Long Beach due to the sizeable Cambodian community

there, said that she did not yet feel that she was “from” Long Beach, while Haze, who eventually developed a sense of connection to the Filipino community on the Westside of Long Beach, originally moved to the city because she was able to find housing near where she worked Haze commented, “So that’s basically it There’s nothing big of a background about it It was the easiest one I could live in during that time I was looking for a place”

I grew up in Long Beach, I've moved around Long Beach, I've gone to school in Long Beach, … I lived my whole life here.

In addition to the ties that linked study participants to Long Beach, there were also factors that made them feel disconnected. Most prominently, many participants, especially female-identifying participants, remarked that crime, street traffic, trash (especially at bus stops) and the fact that some people live in the streets made them feel unsafe walking in their own neighborhoods, especially after dark Interviewees mentioned having cars broken into, hearing gunshots, having to walk next to people who were having mental health episodes, public drunkenness or drug use, and dangerous driving as concerns Tom, who was originally from the Philippines, mentioned a freeway entrance ramp where pedestrians encounter speeding cars He commented, “Because I spend a lot of time in the Westside, I guess, you know, similar thing, that people go fast, there’s like so many traffic accidents, deaths” Parking was another safety issue that emerged in interviews Mandy commented on her experience as a pedestrian, “When people park in the red spots, it’s just a blind spot for the pedestrians If pedestrians are crossing, you have to stick your head out first to see if there are any cars And if you’re good then you’re good But other cars just don’t see them and then immediately have to stop as you’re crossing the street” Haze, who lived in an apartment and did not have an assigned parking space, described parking as a constant challenge: “There are times that sometimes you would spend an hour just to find one. And you know you just keep circling around until someone leaves. And it messes up your schedule, whatever your plans are.” Gentrification and the rising costs of rent were also factors

that some participants felt might force them to leave Long Beach Tim observed that “There are conditions changing within Long Beach, where longtime residents are being pushed out of Long Beach itself and moving to completely different states or different cities It feels like the people who’ve made Long Beach Long Beach in my childhood are all no longer there or are being pushed out as more housing is being developed.”

It feels like the people who’ve made Long Beach Long Beach in my childhood are all no longer there or are being pushed out as more housing is being developed.

Although many participants associated Long Beach with openness, a few participants described microaggressions or instances of overt bigotry that made them feel that they did not belong in particular neighborhoods One participant who was originally from Mexico and who had lived in Long Beach for almost twenty years, said that when she went to wealthier parts of the city, she felt that residents there looked down on people from Mexico She commented, “There are some that look at us with contempt, they look at us as if we stink So, I don’t feel very comfortable passing by there again” This participant shared a story about friends who were working in a wealthy area on a hot day and who took a break in the shade on the strip of grass between the sidewalk and the street, only to have a resident hose them down and ask them to leave She commented, “We don’t belong in their world”

In sum, most interview participants had strong and multifaceted ties to Long Beach and hoped that the challenges that they experienced could be addressed in the future

Our preliminary research reveals that immigrant residents of Long Beach experienced multiple sources of support and vulnerability, potentially impacting their civic engagement. Sources of support included personal networks (family, friends, coworkers, employers, teachers), institutional connections (community organizations, church, school, community ties), and personal qualities (perseverance, self-reliance, language skills, cultural knowledge) Personal networks were key to study participants’ immigration journeys, success after arrival, and ability to withstand emerging challenges Numerous participants reported having a “pioneer” relative who immigrated to the United States first and then either petitioned for other family members or facilitated their travel Such relatives provided key resources, such as housing, employment contacts, and transportation Mandy recalled, “My parents, I think, I think it was fairly easy to just find work because they had a lot of family that was living here So, they just kind of went through connections” Friends and acquaintances also provided support, such as job opportunities and emotional support, a key resource in the transition process Alice related, “I kind of turn to my friends, just to kind of rant to them, because a lot of them are immigrants themselves.” Children, who acclimated to the United States and quickly learned English, served as both translators and cultural brokers for their parents . Tim explained that when he was a child, his peers not only translated from Khmer to English but also helped with “navigating the tax system and property ownership with their parents.” Tim eloquently described what it was like to grow up as part of a tightly knit immigrant community:

We have a lot of Cambodian neighbors too, so whether it was like my grandpa who did have a driver’s license at the time, or my aunt who was in the middle of city college also driving us, but also neighbors and family friends who had cars…. All of us kids who were around the same age, maybe we’d carpool to the same school or if one family wasn’t home one night … and needed kids looked after, just send all the kids to one family’s house or another.

Such community-based mutual aid also has proved essential as immigrant residents face increased immigration enforcement Study participants who felt at risk shared that friends and relatives were giving them rides to work, providing groceries, and running errands, to limit their exposure. One study participant commented that community members were “passing our voices, protecting ourselves, protecting one another.”

In addition to personal networks, local institutions were also key sources of support. Anthony recalled that the Cambodian community helped his parents overcome language barriers: “my parents didn’t know English. But they were in Long Beach, so they could at least speak Khmer.” Schools were important institutional connections, as these sometimes had social workers, scholarship opportunities for children, parenting groups to facilitate connections with other parents, and ethnic studies courses For example, Tom learned about the Filipino Migrant Center through a community college professor Religious institutions also provided important resources Samnang was grateful to her children for linking her to a Long Beach community leader who was fluent in Khmer and English Samnang’s church also provided food and support when Samnang was recovering from health issues Likewise, SH shared that her church provided a foundation of advice and support as

I should be experiencing these things that normal teenagers like me in this country should be experiencing.

her family moved to Long Beach and Claudia mentioned the importance of a church-based center where people would gather to study English. “I felt loved, like God never left me,” Claudia said. Multiple interviewees cited the Long Beach Public Libraries as an important institution that provided practical services such as printing, internet access, and homework help as well as culturally relevant programs and materials Lastly, study participants stressed the importance of community-based organizations in supporting them on a day-to-day basis In addition to the Filipino Migrant Center, Latinos in Action California, and United Cambodian Community, interviewees mentioned the Cambodian Association of America, Anakbayan, Órale, Los Angeles Alliance for a New Economy, YMCA,

Salvation Army, SBCC, Migrante, and cultural clubs in high school and college. Interviewees turned to community organizations for both community and practical assistance with transportation, groceries, and assistance navigating government programs One participant shared, “Filipino Migrant Center has been such a God send to me because while I’m able to find people there who I share the same beliefs with and who inspire me to love my culture and love where I came from, they also physically help me to get to and from work” Likewise, another recalled, “Latinos in Action has been a big part of my community because sometimes when I needed tutoring for a while, I asked if they had tutoring session, and they did, and I was able to bring my grade up.”

Ankot, a senior Cambodian speaker, expressed his gratitude for United Cambodian Community: “I don’t worry about completing any paperwork and am always warmly welcome to help our community members, which is different from the past in that we were not welcome and did not get support or respect as community members” Organizations also filled gaps when family were unavailable, as one participant explained, “My family can’t help me; I always get support from the organizations UCC helped me apply for EBT I can rely on the support from UCC and organizations in Long Beach”

It is important to note the many strengths of the study participants They had raised children as single parents, completed college degrees, founded businesses, navigated the US labor market and educational system, and performed volunteer work in their own communities Participants had rich cultural knowledge and multiple language

skills, as shown in Table 1. Through support from personal networks, institutional connections, and their own resources, study participants surmounted or coped with challenges, while also providing support to others Their accounts of perseverance highlight the critical role of local and culturally appropriate support networks in overcoming barriers, which were sometimes exacerbated by interviewees’ distinct lived experiences

I can rely on the support from UCC and organizations in Long Beach.

Although they had multiple sources of support, study participants reported experiencing vulnerabilities, some of which stemmed from being new arrivals who had faced language barriers, cultural differences, employment challenges, and traumas associated with immigration experiences, whether in their countries of origin, on their journeys to the United States, or after arrival. One participant had lost ten family members during the Cambodian civil war, while another had been shot at, beaten, and raped near the U.S.Mexico border while attempting to reunite with her relatives residing in Long Beach. Other participants experienced crimes, such as domestic violence or assault, in the United States. After arriving in Long Beach, some initially struggled due to a lack of connections. One participant, whose family eventually founded a successful business, recalled, “during the early years, it was hard to sustain a business because nobody knew us. We didn’t have a reputation or anything like that” while another, who immigrated as a teenager, told us “I remember growing up I would feel so left out I should be experiencing these things that normal teenagers like me in this country should be experiencing,” Lack of connections could lead to a sense of isolation A student participant shared, “Coming here, I thought about returning to my town because I didn't know anyone I felt weird I couldn’t talk to anyone about my problems because I didn’t know anyone” Such feelings of isolation were exacerbated by study participants’ separation from family members in their country of origin One participant, who immigrated to the United States just before the onset of the Cambodian civil war, recalled that it was “sooo hard thinking about my kids, thinking about my parents, thinking about us, what we have to do to survive Yes, it’s not easy So, so hard”

A key vulnerability shared among interview participants when they first arrived in the United States was the language barrier. Communicating in English was more challenging for those who immigrated as adults. A Cambodian elder shared that she had learned English in Cambodia, however, in the United States, she discovered that she still could not communicate verbally She shared, “You just learn at school how to write and read, but no speaking Over there, no speaking You just know how to write, read the book and everything” A participant who was originally from Mexico found that her initial lack of English language skills made her feel insecure: “I didn’t know what language to speak at the time I knew that everyone here spoke English So, I was scared to ask a question and have it be answered in English I was scared” Those who immigrated as children learned English quickly but sometimes found that the school system misjudged their abilities One study participant was of Cambodian descent but was born in France and is fluent in French When this participant started kindergarten in Long Beach, the school provided him with translation in Khmer, a language that he did not speak Others were sometimes not given credit for grades or courses that they had already completed 21 22

Financial insecurity was a common vulnerability among study participants, both due to hardships that their families experienced when they first arrived, and in some instances, due to labor practices in the sector where they worked. Many recalled living in crowded conditions when they first arrived, as they joined family members who were in the process of settling here themselves. Reina whose family immigrated to the United States from the Philippines when they were young, recalled living in “really cramped conditions” while Alice shared that “we also lived in a multi-generation household because our grandma was also living there, so, we’re all cramped in this one-bedroom, one-bath apartment.” Another participant described how financial challenges led to food insecurity: “I once visited a food market, but I didn’t have a lot of money I had to look through a trash can for any fruit or food, and yes, I found tomatoes, slightly gone bad I took them, got home, washed them, separated the bad, blended them, I made a salsa, I pureed them and put them in the freezer Throughout time, I would take them out and make soup” Similarly another participant told us, “I was living in a castle, but I wasn’t eating like a prince, or I wasn’t eating decently”

Some study participants faced limitations due to working in sectors that did not pay well or where abuses were common. A participant who now works in food service, discovered that his degree in the Philippines was not recognized in the United States, while some study participants reported that, due to their immigration status, it was difficult to find work Others had family members who faced abusive conditions Abby’s uncle, who immigrated to the United States from Mexico, “had a problem with the machine and he almost chopped off his fingers, so he had to stay home for a while” while Reina’s aunt “had to start working as a 13-year-old and has been working like pretty much full time her entire life” Another participant, who immigrated from Mexico, worked in the garment industry, where she was paid by piece rate instead of hourly wage “You worked a lot and didn’t earn much,” this participant r eported The high cost of living in California also led to financial challenges. One study participant, who had been a business owner earlier in her life, experienced food and housing insecurity as a senior due to the cost of rent and food on her limited income

Another Cambodian senior described how a lack of fresh and culturally appropriate food distributions inhibited her from preparing traditional Cambodian dishes

I once visited a food market, but I didn’t have a lot of money. I had to look through a trash can for any fruit or food, and yes, I found tomatoes, slightly gone bad. I took them, got home, washed them, separated the bad, blended them, I made a salsa, I pureed them and put them in the freezer. Throughout time, I would take them out and make soup.

Lastly, some study participants reported vulnerabilities associated with health. A newcomer to Long Beach described how the stress of immigrating to the United States had impacted her: “I just had a lot on my mind and I lost weight, I feel like, all of a sudden. ‘But why? Why I’m so small?’ Like even clothes I bring from Cambodia only two months is loose” One study participant was disabled, requiring continued physical therapy Another study participant suddenly became the primary breadwinner in the family when her husband suffered a stroke Health insurance was a primary concern for study participants, some of whom had to navigate complex insurance systems for other family members, particularly children Health care costs were another financial challenge, as a participant observed, “One of the reasons a lot of immigrants are having a hard [time] to go out and actually take care of their health, it’s because they’re not able to afford it, especially let alone, being able to afford rent or groceries” These vulnerabilities and sources of support impacted study participants’ abilities to engage city services and participate in local political processes

Our analysis of the preliminary interviews that we conducted as part of our research design process identified three key barriers to immigrant residents’ engagement in city processes:

1.Feelings of Intimidation and Lack of Trust: Some study participants reported that they were raised to avoid government institutions, and that they felt intimidated by officials.

2.Knowledge Gaps: Some participants did not know their representatives, were unaware that they could make public comments at City Council meetings and did not feel knowledgeable about city resources.

3 Practical Constraints: Some interviewees stated that transportation challenges, work schedules, childcare responsibilities, and language barriers prevented them from accessing city institutions and processes.

These barriers were exacerbated by current heightened immigration enforcement as well as political polarization It is important to note that while our preliminary research focused on Cambodian, Filipino, and Latinx residents of Long Beach who identified as being of immigrant background, these barriers may be experienced by other residents as well Moreover, even within immigrant communities of Long Beach, barriers are not evenly distributed For example, a single parent raising a family may face greater constraints than a member of a two-parent household, or someone without children

A common theme among interview participants was feeling intimidated by or a lack of trust in city officials Such sentiments were not universal, as some participants reported that they knew their city council members personally, had attended one or more city council meetings to give public comment, and had no qualms about approaching city officials to access services However, we also repeatedly heard concerns from those who felt disempowered Feelings of intimidation and lack of connection stemmed from multiple sources. Some participants noted that the traumatic histories of their communities made them inclined to remain invisible when possible. A participant commented regarding the Cambodian community, “there also is an undercurrent of trauma that leads to this mentality of wanting to be hospitable but also invisible.” This participant elaborated, “They conflate city and federal institutions with the police…. The idea of food services … requiring you to give your social security number or immigration status or even like, or even disclosing your

address or phone number when you’re signing up for things, it’s met with a lot of hesitation because the communities kind of have this inherent fear of institutions.” Another participant observed that such concerns can be transmitted from one generation to another: “they [youth] have a lot of inner trauma, childhood trauma that translated from those immigrant parents” Social hierarchy was another source of intimidation A participant remarked, “It is a little intimidating to speak to councilmembers in the sense of like, they are higher up in society than you Will they listen? Is what I’m mentioning worth it? Like how that is higher up and I’m just a normal citizen” Likewise, other study participants viewed city officials as members of a privileged social strata, with greater economic resources Such participants did not trust that city officials would listen to their concerns, devote resources to the issues they care about, or respond promptly and honestly One participant mentioned that it was challenging to find the correct person to whom one should speak: “I feel like it holds back because it’s having to like navigate through the different people that you have to talk to just to get to the person that you want to talk to directly for them to actually address like the concerns you’re raising” Mandy summed up this barrier succinctly, stating, “It takes a lot of courage” to speak to City council.

A question that generated insight into this sense of intimidation and lack of trust was “How do you feel if you go into a government office?” Some participants felt comfortable and had done so repeatedly. Yet, even if they had done so, participants often expressed deep anxiety about entering government buildings. Anthony recalled his experience, “I was nervous, definitely nervous. But I was also overwhelmed with the amount of people that were present. And I was overwhelmed, confused, nervous, but at the same time very anxious.” Some felt out of place in government offices For example, Clara commented, “I felt as if it’s a building only attorneys and professionals go into,” while another participant remarked, “I feel weird It feels, I don’t know, like, it feels, I don’t know how to explain it! It’s – yeah, I guess it feels like I don’t belong there? Yeah Yeah It feels like I’m out of place I guess it seems more powerful? It projects more powerful than it should Yeah And I think it’s just like people automatically wonder why you’re there” Reflecting on current anti-immigrant sentiment, one participant stated, “It’s only dawning on me now

There also is an undercurrent of trauma that leads to this mentality of wanting to be hospitable but also invisible.”

how twisted that makes, how, how dirty that makes me feel. I’ve never committed a crime in my life, but now I'm fearing entering a government building. That actually fills me with dread.”

Current ICE raids and political polarization greatly exacerbated study participants’ feelings of intimidation and lack of trust, even for US citizens Due to the sensitivity of this topic, we are omitting even the pseudonyms associated with comments about immigration enforcement and the current political context, but these comments do cut across immigrant groups, racial categories, and differences of immigration status Due to their importance, we include a series of representative comments below:

“Especially with ICE going on right now, it’s terrifying to be an immigrant here in the US and to share your voice because the consequence of doing that – and I think for me, being a citizen already and knowing that I wouldn’t be targeted by ICE because I’m a US citizen.”

“Some of the Cambodian immigrant parents are afraid to engage with the community, especially with ICE, that kind of makes them a little more timid and just downplay their proudness of being Cambodian.”

“Right now, in this administration, everything that would be considered a grey area or an okay area is now being labeled as red. It is now being villainized, demonized.”

“Never once in my life did I ever think I would have to be one of those people that has to look over my shoulder because ICE would be there.”

“I still don’t have my license, I'm about to take it [the driving test]. Which is actually a little fear of mine because apparently ICE works with different organizations in the government, so, there’s rumors they’re working with IRS, there’s rumors they are working with the DMV.”

“Now, it’s the government officials that I fear because I could just be taken off the streets, be sent to who knows where.”

“Hopefully, tranquility will return. But tranquility is over.”

“I was getting ready to go run with my friend when we all of a sudden see the immigration car pass by. We were like, ‘Damn! They’re here in Long Beach already.’ ”

“I was like overwhelmed and kind of scared because I have heard some cases where they even get, um, any person, like, they don’t even care if you are from here, they just grab you because you look Hispanic.”

“I cannot feel guaranteed that I’ll be safe if I enter this, like, federal building, especially seeing that, like, ICE is being allowed into like hospitals and other basic institutions that ICE should never be in, you know. Like, if ICE is allowed in a hospital, who is to say ICE won't be allowed into a government building?”

“With immigration today, you go out, but you don’t know if you’ll come back…. We don’t know how much longer we will be here.”

“I’m scared to go somewhere far and meet with ICE.”

“The entire community going through this great fear and insecurity that results from a loved one being detained is at the core of this suffering.”

These quotes demonstrate the dire impacts that immigration enforcement activities are having on Long Beach residents’ sense of well-being, self-worth, and belonging. Some study participants have stopped going to public parks, others are staying home from work and remaining in their homes as much as possible. Interviews also suggested ways that study participants and their families are supporting each other, for example, by sharing rides, running errands, and notifying each other about enforcement activities Participants also spoke of turning to community organizations for assistance and information The sense of caring for each other was palpable These quotes also demonstrate the breadth of those who feel targeted based not only on their immigration status but also their race, appearance, and country of origin

Increased immigration enforcement at the federal level also impacted study participants’ willingness to engage with city officials Some participants distinguished between the federal government and the city, noting that Long Beach is a sanctuary city and that immigration enforcement is a federal matter But others remained concerned One study participant told us, “there have been times where I really wanted to talk to a city official, but I think that it’s because, I know Long Beach is like a sanctuary city but still, like, coming face to face with like, law enforcement or anything related to the government kind of makes me like terrified. Like, just knowing that they know of my immigration status makes me scared to like, that’s why I try to avoid cops as much as possible, or anybody from any type of city government, just government in general.” Another participant related an experience approaching city hall to do paperwork and seeing people that she thought were immigration agents. She simply kept walking instead of entering the building, and has never gone back, despite having previously felt safe there. In such a context, intimidation and distrust are heightened.

One of the most significant barriers identified during our preliminary research was gaps in knowing what services and opportunities exist and how to access them Such gaps indicate that there are sectors that are not reached through current communication strategies. Most striking was that when we asked whether participants had met with their city council representative or gone to a City Council meeting to give public comment, some replied, “You can do that?” If someone does not know that an opportunity exists, they cannot take advantage of it, regardless of whether they feel empowered or intimidated. One participant who worked closely with a nonprofit and who was knowledgeable about resources observed of community members, “There are so many more resources that they could utilize, like food stamps, and that, in a sense, is getting involved with the government because it’s government funded But they don’t really know that and they don’t understand it”

We also asked participants to describe the city services they use, and were struck by the number of study participants who said that they did not use any city services

Because people who live and work in Long Beach of necessity, likely use some city resources, this response indicates that there may not be a general awareness of the services that the city provides Some study participants reported that they have not signed up to receive emails from the city, and therefore did not receive regular communications about events and opportunities One study participant tried to learn about the Westside Promise, but did not feel that people who lived on the Westside were kept informed about plans: “Like in my area, I don’t even know what’s happening I don’t get any news about what’s happening around me And because of

my work in the Westside, it’s the same for them”

Like in my area, I don’t even know what’s happening. I don’t get any news about what’s happening around me.

Participants identified schools, public transportation, and health resources as areas where they felt especially hampered by gaps in knowledge. Regarding schools, several study participants had experienced challenges as first generation students who had to navigate transferring course credits from their country of origin, applying to college, and understanding financial aid on their own. An interviewee who, at the age of 15, had had to educate her high school counselors about courses she took in the Philippines, said, “Unless you advocate for yourself and you actually have the firmness to make them understand, they will not do

anything.” Several study participants reported that public transportation was confusing and that the system to pay fares did not always work properly. One participant shared that because, as a new arrival, she did not understand the local bus system, she traveled on foot: “I walked because I wasn’t familiar with the bus stops, I didn't know the bus schedule, I didn't know that I needed to get off at a certain stop to get on another bus What I did was walk For my first job, I would clock in at 5 in the morning I would wake up at 2 because I would spend two hours walking. I would go and come back walking after I was off at 1:30, so I would get home at 5 in the afternoon.” Another participant felt that broken payment systems put him at risk of deportation: “The buses are kind of crappy in regards to just, you know, taking money because if that happens and some person goes, ‘he didn’t pay!’ and then, you know, I’m already a targeted person in regards to this whole, you know, stupid administration This, what I'm doing could be a misdemeanor to them Which, for some reason, any little thing that an immigrant does that is bad is already open for deportation” Several participants also mentioned that the process of applying for resources such as MediCal was confusing, leaving them or their children without health insurance One interviewee commented, “My son’s MediCal, I go, ask for help, ask for MediCal, and they deny it, they deny it But they don’t say why, they don’t say why They just tell me to submit the paperwork but they don’t explain why, such as, ‘for this and this, he needs this,’ [or] ‘you exceed the income requirement’” While MediCal is a state resource, not a city one, this comment suggests the importance of navigators to help residents access such support.

For my first job, I would clock in at 5 in the morning. I would wake up at 2 because I would spend two hours walking. I would go and come back walking after I was off at 1:30, so I would get home at 5 in the afternoon.”

In addition to intimidation and gaps in knowledge, practical issues, such as limited time, transportation challenges, or childcare responsibilities, made it difficult for some interviewees to participate in city processes. Practical constraints were linked to the vulnerabilities discussed above, but also sometimes resulted from the ways that opportunities are organized and offered. For example, several participants who had gone to City Council to give public comment complained that the meeting, which began at 5 pm, dragged on and their issue was not raised until after midnight. An interviewee recalled, “I actually found it extremely frustrating that not only was the meeting incredibly long, it started at 5:00 pm and it went all the way past midnight, actually, until 12:30, um, so I signed up for public comment but I wasn't even able to be present until anywhere close to when my name was called because I had things to do, and I didn't suspect that it would go on for like 7 hours” Some interviewees who sought assistance from local government offices had long waits A participant who was trying to register her child for MediCal noted, “It was complicated for me because I’d have to be there all day and without food On top of that, I had to go with my little girl who was a year old” Another participant shared, “I did feel nervous asking for their [social services] support I had to pack lunch/food because the wait time was too long”

Onerous documentation requirements were also cited as a barrier for accessing local services Some of the services that interviewees discussed were state or county resources, which is another indication that the boundaries of city services are not always clear to them We provide these examples regardless because they demonstrate the administrative burden that documentation requirements can impose, both for citizens and noncitizens of immigrant backgrounds:

“The DMV because I gave all of what I could give in regards to my documents. And they told me that they needed a second investigation … for me to take the permit test.”

“I was taking a [driver’s license] test with everyone else, my bar code won’t work, my thumbprint won' t work, they had me go back in line and they told me, ‘Oh, you need another parcel of identification.’ ‘I gave you everything, what do you mean?’ ‘Oh, your passport, um, is one of those countries where … it’s not exactly a valid piece of identification. A Filipino passport is not a valid piece of identification?! What are you talking about?”23

“I think a lot of the things that I’ve gone through with, in regards to like city resources, is just like a lot of like extra steps that people who are citizens wouldn't have to go through, like the amount of times that I’ve had to like prove that I actually live here, is, like, really annoying, like I have to bring the same documents every time just to prove that I live here, even though I’ve been living here for the past 18 years of my life. I don’t even remember my life outside of America, so the fact that I constantly have to prove that my life is here, is very like, annoying.”

“We were not in the system here at all. Like until our name was in the system, buying things, and things like that”

“I don’t qualify for it [food assistance]. Even the computer, you know, I got the letter that shows that my money, every month is that much, that much. I don’t qualify either. They ask for the income tax [statement]. And I did not file the income tax. Because I did not earn enough money to file the income tax.”

“Every semester, every time I had to apply for financial aid, I always had to send documents to the Philippines for my mom to sign, and she had to send it back for me to submit. And they’re not allowed to accept electronic signed things. It needed to be physically signed. And every year, I had to meet that deadline for it to be eligible. Because if my mom is not able to send it back on time or vice versa, then I would not have the financial aid support. So it’s one of those unique things that I have to navigate because no one else was going through it.”

These examples illustrate the documentary burden imposed by requirements to prove residency, and restrictions on acceptable documents and signatures Having to secure documentation sometimes required great effort

Financial constraints, childcare responsibilities, and work schedules also prevented some participants from engaging with local services. One participant was unable to register her child for daycare until she paid for expensive vaccinations herself, because she could not navigate the MediCal enrollment process. If services were only open during work hours, then accessing them would require missing work, a hardship for those on a limited income. Childcare also posed a barrier for single parents who would have had to bring children with them to speak at a city council meeting.

Lastly, language barriers were an issue for some study participants. Spanish speakers generally were able to access translation services, whether through formal translators, officials who spoke Spanish, or relatives who provided translation. Khmer and Tagalog speakers had greater difficulty. One Tagalog speaker told us that even when translation is provided, the quality is not always sufficient for understanding She related: “There are resources where they provide the language in Tagalog, but actually whenever we speak with other Filipinos, you would hear a lot that even though there are materials in Tagalog, it’s only translated using google translate or some kind of like AI or I don’t know, some kind of electronically translation So it’s hard to process and understand” Similarly, a 65-year-old Khmer speaker, shared the following when asked about language barriers he’s faced in the city, “The [written] translation is sometimes not understandable and sometimes unreliable For [oral] interpretation, it was good and understandable”

Together, feelings of intimidation and lack of trust, gaps in knowledge, and practical constraints served as formidable barriers to immigrant residents’ engagement in city services and processes. However, our interview material also included examples of overcoming these barriers as well as suggestions for how barriers could be removed or reduced in the future.

Study participants had creative ideas about how to address the barriers that immigrant residents faced in engaging with city processes. The suggestions that we highlight here were gleaned both from participants’ accounts of what worked, and from their ideas about new programs or policies that they would like to see. Some of their suggested practices may already be in place, in which case their recommendations highlight gaps in who these practices reach As well, accounts of existing practices that are working provide important positive feedback Each of these recommendations corresponds to one of the barriers identified above Thus, the barrier of intimidation and lack of trust can be reduced by adopting trauma informed practices, that is, by awareness that immigrant residents and other members of the public may have experienced trauma and welcoming and honoring their contributions The barrier of gaps in knowledge can be addressed by developing new forms of access and strengthening pathways to communication In particular, study participants advocated supporting community institutions in which immigrant residents are involved and using flyers or direct contact to reach those who may not be digitally active Lastly, the barrier of practical constraints can be addressed by codesigning policies and practices. Doing so would entail working closely with immigrant residents and immigrant-serving organizations to design processes that overcome practical challenges. We detail each of these recommendations below.

As noted above, immigrant communities are multidimensional, with strengths and sources of support as well as vulnerabilities. Adopting trauma-informed practices is a way to address these vulnerabilities through “an organizational change process centered on principles intended to promote healing and reduce the risk of retraumatization for vulnerable individuals.” Core principals of trauma-informed policies include ensuring safety, inspiring trustworthiness, being transparent, collaborating, empowering others, providing choices, and recognizing intersectionality, that is the multiple facets of identity and experience that make immigrant communities highly diverse. Study participants described existing practices that had enabled them to overcome lack of trust and intimidation to engage with city services One strategy has been to take collective action One participant, who had been discouraged from speaking to City Council by what he perceived as social hierarchies, successfully gave public comment as part of a group He explained, “When you go in with community, I feel like it’s more, you feel like at the same level Because you have a sense of other people with you, you have the community with you, and you’re not just worried about yourself” Likewise, a participant who was nervous about entering government buildings, commented, “I would be more confident if I was together with more people too, those who are experiencing the same feelings or agitation towards the current conditions that are happening”

Participants who had successfully reached out to city representatives or accessed local services stressed the importance of feeling safe. One participant who spoke to City Council, commented that council members “were all very openminded and willing to listen…. It was like a safer space to share your thoughts and to fight for your community” Another who had also given public comment described overcoming her fear: “You stand there and feel yourself falling but you sustain yourself because you’re there Once you say that you want to speak on behalf of your organization to support the community We went to go talk about the community center, we went to speak, we went to ask, it went well I felt good after speaking but before that, I was trembling” Other study participants emphasized that when they were made to feel welcome in city offices, they were more likely to return One participant who entered a government building to pay her gas bill reported, “they always help me with kindness and respect , the ‘Good morning, good afternoon, how are you, or have a good day’” Her words were echoed by another participant, who described positive interactions with the service worker who helped her apply for MediCal: “It depends on the type of person, that trust that they project, feeling as if you’ve known them for years That’s what I remember about her, her kindness, ‘Hi, mija, how are you?’ her facial expressions. I will remember her kindness…. ‘Hello, welcome, what can I help you with?’ That! It’s that empathy, joy, even enthusiasm that you get from meeting a new person.” Another participant appreciated when service providers were not “just looking at you just like a client, they actually see you as part of the community, as a person whose actually in need of those services or even like, um, leveling down to you, eye to eye, and like actually understanding the conditions you’re coming from.”

Having safe spaces to share their thoughts and experiences while being listened to without being judged was important to study participants.

Participants also reported that their hesitation to approach city leaders was reduced through language access, representative government, and a welcoming environment Interviewees appreciated Long Beach’s language access policies, which provide interpretation and translated materials One participant shared a story about the value of having multicultural and multilingual staff:

Even helping community members calling the Long Beach Department of Social Services, and I was helping a client apply for SSA or to do something about their SSA and when I called, she asked, ‘Does the client speak English?’ And I said, ‘No, they speak Khmer.’ And she was like, ‘Oh, I speak Khmer.’ … Because of that, she’s able to connect with the community member that she’s helping.

Study participants also remarked positively on the diversity of the Long Beach City Council and expressed appreciation for physical environments that were “open and inviting.”

In their feedback about what was working well to reduce intimidation and to build trust, study participants singled out the Long Beach libraries as an exemplary institution Interviewees mentioned that the libraries provided valuable and accessible services, with welcoming staff who assisted them with challenges As newcomers to Long Beach, they turned to the libraries for assistance studying Khmer, homework help, printing, computing, internet access, and information about community resources A participant recalled happily, “There were music events, where you learn about afro-music and their traditional dances There were also different programs for children’s books You could even go to do homework There were always important events, and I really liked it In fact, I’ve been very involved with the library” Study participants reported that the Long Beach libraries helped them integrate as newcomers Alice shared that her family “would like rent a bunch of their VCRs, like we’d rent like Pokémon, SpongeBob, Elmo’s World, because I was like five at the time. And that’s how my sister and I honestly, um, started learning English because we didn't have cable TV, we didn’t have cable TV unit … so, we’d go to the library a lot.”

Similarly, S.H. stated, “When we [were] newly here, let’s say before we had a car, before we had internet, we were at the library almost every day. We’d be [there] two, or three or four times a week. We’d go sit there, read, and use the internet [for] email, and my kid [would] study, [do] assignments and stuff.” Interviewees also shared that they found it easy to apply for a library card and check out books. Providing accessible, culturally diverse materials and practical resources in a supportive environment is a model for trauma-informed practices.

Study participants provided examples of outreach strategies that had connected them to the city, while also recommending additional practices that could strengthen communication pathways The most common way that participants had engaged with the City of Long Beach was through festivals, parades, and resource fairs They appreciated cultural events, such as parades celebrating the Cambodian New Year, Martin Luther King Day, and Pride Month. One study participant described Long Beach as a place where “There’s always some kind of community event going on. And I think that’s hard to find in some places. Downtown Long Beach, 2nd and PCH, multiple parks around this area of Long Beach, North Long Beach, fourth Fridays. There’s always something to attend and to feel a part of the community.” Participants sometimes met representatives at resource fairs or other events, and also appreciated the booths that gave out information. Social media was another key source of information. Participants reported learning about beach clean-ups through on-line postings, finding internships on the city website, encountering resources via Instagram, and reading city emails and newsletters. Flyers were also important, especially for downtown Long Beach residents Lastly, a small number of participants had experienced direct outreach Mandy recalled, “Nowadays, you have people knocking on doors saying, ‘We have this resource fair going on’ Or ‘The city is doing –like especially during Covid they would do the vaccine shots And not too long ago, they were doing a street clean-up so they knocked on doors to let people know”

There’s always some kind of community event going on. And I think that’s hard to find in some places.

Study participants had concrete suggestions about how to further strengthen communication pathways One suggestion was to work with parents and the older generation of immigrants to foster engagement One participant explained, “How their parents act translates to the youth’s willingness to do things and take initiative. Like even having them join our programs, it’s like, they tell their parents they want to join, and because we’re a Cambodian nonprofit, it’s like, ‘Okay, if they’re Cambodian, it must be okay.’ … helping those immigrant parents understand why civic initiatives are important will translate into youth being more leaders in our society and to continue fighting for our community and what Long Beach stands for.” Participants also recommended building networks through community ambassadors or

liaisons so that information could be shared through word of mouth. Some interviewees recommended organizing even more events, particularly focused on education, such as career fairs and programs to promote college readiness. One study participant, who had immigrated to the United States recently, advocated that the city create a workshop or orientation for newcomers She stated, “I wish they, like when I first arrived, if I wanted to know better how to start living here, where should I go?” Such an orientation could be recorded and posted so that it would be available online, and a hotline could be established to answer questions Participants suggested that even more social media would be helpful One participant recommended “Instagram because that’s where they basically post online posters, or online billboards, ads, or anything of that sort I would say TikTok too, but TikTok is more news of what’s happening rather than a party or an organized event” Participants suggested doing more to encourage community members to subscribe to city listservs, websites, and social media outlets Lastly, for those who were not on social media, interviewees recommended posting flyers at schools or parks, outdoors, on bulletin boards, as these locations are visited frequently by families and are trusted community resources. A participant envisioned “some sort of bulletin board, like at schools, or at organization buildings? I feel like it'll be better outside the building. Sure, there’s a risk there to having it outside. But people are too nervous to go in a building, so they probably won’t see resources. Like, they’ll probably walk past this building and say, ‘Okay, there’s a building there, but I’m not going to go in there, because I feel too nervous to go in there.’ But if they had resources posted outside or outside of schools or parks [it would be better.]” These experiences and recommendations demonstrate community members’ desires for greater engagement but also gaps in current outreach.

Codesigning processes is a key way for institutions and constituents to establish procedures that overcome practical challenges Codesigning builds egalitarian relationships, enabling community members’ experiences and ideas to inform not only policies but also ongoing practices of public engagement and service delivery. The agendas for codesign can be established jointly, thus furthering communication and trust while valuing the input of community members. As an example of what is already working well in codesign, participants stressed the important role that community organizations play as “brokers” between city agencies and community members. One study participant stated, “For UCC definitely, they foster a safe inclusive environment where community members always come back if they have something that they’re dealing with or a challenge” while another mentioned that “What I love about FMC is that they’re able to see, not just anticipate, they’re able to see the problems within the community” Study participants credited community organizations with helping community members navigate services, presenting information, and establishing a safe place where immigrant residents feel comfortable A study participant who volunteers with Latinos in Action California explained, “We provide people with information and resources about events that will be held and what help is available We also distribute event flyers The officials that come here are very kind because you can speak with them They help you if you need something They also bring resources” Community-based presentations featuring city officials or agencies were an especially successful approach to codesign

Participants also mentioned that opportunities to volunteer had connected them to organizations, thus enabling them to provide input Doing volunteer hours for school or completing school assignments such as writing to city council or attending a community event were especially valuable in forging such connections.