through the haze: examination of hazing legislation | page 14

green lies, real crimes: why greenwashing deserves legal consequences | page 38

chiraag bains: reform and realizing the promise of democracy in the u.s. | page 54

The University of Chicago Undergraduate Law Magazine (ULM) is the College’s premier student-run legal publication. ULM is a pre-professional community committed to the exploration, analysis, and evaluation of issues pertaining to the law and seeks to demonstrate its role in shaping society’s agency, authority, and attitudes towards life.

Editor-In-Chief

Aya Hamza

Managing Editors

Senior Ryanne Leonard

Junior Ana Estupinan

Executive Editors

Ahmed Ahmed

Divya Mehrotra

Iman Snobar

Style Manager

Austin San Juan

Illustration Manager

Lia Yufei He

Staff Writers

Fimisokan Adesemoye

Isabel Alia Arias

Sebastian Arnal

Alia Bencheqroun

Jack Bourdeaux

Simon Camelo

Kimberly Chavez

Meghan Derby

Cyrah Gayle

Maya Gutierrez

Associate Editors

Elijah Bullie: Two Views

Michelle Du: Opinion

Samuel Espinal Jr: Legal Analysis

Aminah Ghanem: Interviews

Kevin Guo: Upcoming Chicago Policy

Rocio Portal: Upcoming Chicago Policy

Alejandro Sandoval Elizondo: Two Views

Nikulas Soska: Legal Analysis

Héloïse Vatel: Opinion

Jonathan Ji

Devon Jiang

Isabella Kelly

Letom Kpea

Yoo-Bin Kwon

Ashley Lee

Harris Lencz

Jennifer Li

Vincent Li

Jolin Liu

Scarlett Lopez Rodriguez

Social Chair

Lizbeth Herrera-Gomez

Treasurer

Kathryn Fang

Digital Content Managers

Doan Tran

Tejas Shivkumar

Community Relations Manager

Tomas Vallejo

Print Manager

Natalia Girolo

Addison Marshall

Jack Martinez

Samuel Morse

Sara Munshi

Zoe Nelson

Dat Nguyen

Nicole Ochoa

Zoë Parkin

Andrea Pita Mendez

Teddy Pitofsky

Christopher Rodriguez

Leena Sfar

Sanjay Srivatsan

Emberlynn St. Hilaire

Ovia Sundar

Maya Sundararajan

Rivka Tamir

Haley Thomas Ariel Trejo

Aparna Viswanathan

Megan Wei

Oscar Zhang

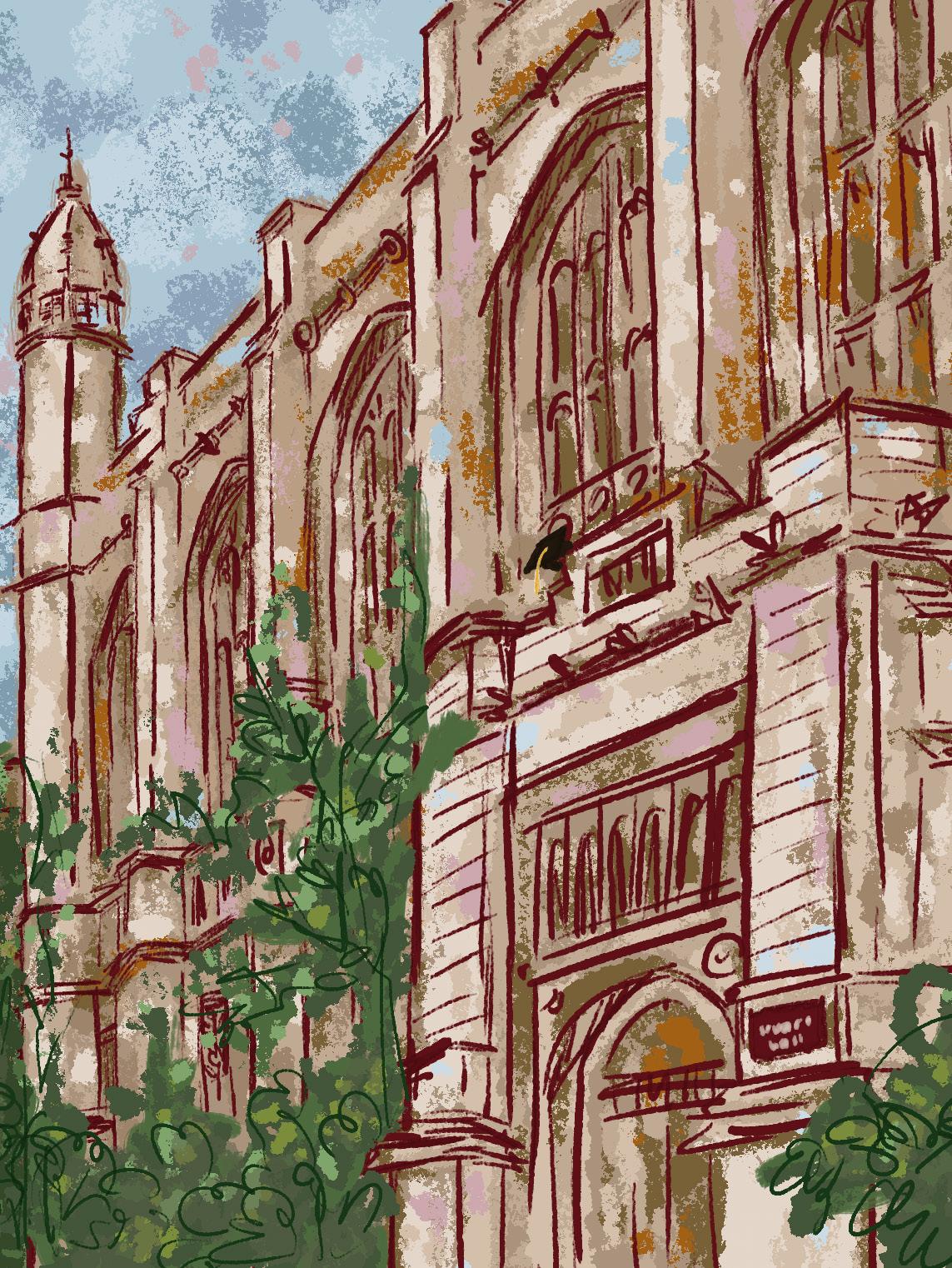

One thousand, one hundred, and eighty-five days ago, I positioned my laptop screen away from the door at the Philz Coffee on 53rd Street to avoid any familiar passersby’ gaze. Embarrassed, I was toying around on Canva designing a logo for an RSO I eagerly wanted to bring back. In the months prior, I shared my desire with various mentors and advisors, all of whom sternly advised against it. The brunt work required to revive an RSO would not be worth it and would ultimately distract me from my education. Besides, there were other legal RSOs in the University of Chicago sea.

Restless, I could not shake what ULM might have looked like. Too many hours later, I looked at the logo that graces the cover of this sixth issue. I was upset that I liked it. Feeling defeated yet motivated, the imagination of what might be if this were a real thing refused to release me.

Even eleven days before graduation, my heart still jumps when I spot a ULM sticker on a laptop at the Reg or read proud comments from new staff writers’ parents after posting their articles on LinkedIn right after a release. There are no lawyers in my family, but there is a whole lot of grit. Picking me up from middle school, Baba—my father—drilled the tired adage he always did: the importance of “the power of question.” Start off behind or lost. But whether we stay in place is up to us. I have since sought out spaces where I was confident that much of what I yearned to know lay in conversations to be—albeit nervously—had.

Though outside the Core Curriculum, within the walls of Stuart 101, ULM became not a source of distraction but a hallmark of my undergraduate education. Publication cycles that were never long enough kept me alert. Whenever I led an issue’s article ideation session, I never hesitated to ask new and veteran staff what new legal terms, topics, or cases intrigued them. In each “Good Idea Sheets” meeting, I intended to model my – and this magazine’s – commitment to learning by first proudly admitting to not knowing. Every turn of a page upon final layout review taught me something I didn’t even know was to be learned. The privilege—and pressure—of realizing all I knew ULM could be weighed on me each time I saw our logo. The promise I made more than three years ago to ULM’s early supporters and my mentors kept me on track through endless editing sessions, scheduling discussions, and print meetings. I owed it to them to ensure that every student who ever edited, wrote for, or even viewed a ULM article was equipped with the guidance and encouragement necessary to communicate the unique value of their knowledge and opinions effectively. Surely, volume after volume, there were fewer typos, tighter arguments, and broader outreach.

Mama, too, worked to instill moral sense in me at school pickup as early as third grade. She repeated, “Your degree is your weapon.” My friend’s mother substituted for our class once and urged us to focus on the assignment at hand if we hoped to advance to the next grade. I turned back to agree and parrot Mama’s sentiment. The tiger mom I came to know laughed, “Oh, sweetie, it is way too early for that.” Years have melded together. I carry the chattiness in my seat at Coconut Grove Elementary and restless ULM distribution nights in Reynolds Club with me forever, wherever.

With immense gratitude, I share the pride and joy of my time at the University of Chicago with every sentence and student who shaped ULM into the home I will desperately miss, one I will confidently leave in capable hands. As for mine, they look forward to receiving their long-awaited academic armor in a few short days.

For the last time,

Aya Hamza

Refounding

Editor-in-Chief

by MAYA SUNDARARAJAN STAFF WRITER

Manypeople who believe that society must rapidly regulate artificial intelligence (AI) have looked to federal agencies like the National Institute of Standards and Technology and the Copyright Office to take action. This makes sense because given the immense scope of possible change that AI may engender, regulating it isn’t just about creating new laws, but about appropriately reinterpreting existing laws in the context of AI. The Biden administration issued a series of executive orders urging agencies to shape new policies that anticipated and appropriately promoted or restricted AI development and use. With the reversal of the deference affirmed in Chevron U.S.A. v. Natural Resources Defense Council, the ability of federal agencies to reinterpret existing laws in our new technological context has been limited. The guardrails around AI and much of what governs this exciting yet unpredictable technology will now be shaped by litigation rather than regulation, delaying what may be considered necessary until long after it is needed.

“Chevron deference” refers to the selective prioritization of federal agencies over judicial bodies when ambiguous laws are being interpreted. The term stems from the precedent set by the case Chevron U.S.A. v. Natural Resources Defense Council, which involved a regulation passed by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)

under The Clean Air Act, and favored the EPA’s interpretation of the law.1 Beyond the specifics of the case itself, the decision thus established that courts must defer to agencies if the statute in question is ambiguous and the court finds that the agency’s construction of the statute is reasonable.2

Recently, however, in deciding Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo, the Supreme Court overturned Chevron deference, reasoning that the level of deference afforded to agencies under Chevron was arbitrary, unconstitutional, and in contradiction with the EPA.3

In this new era of post-Chevron deference, courts are no longer required to turn to federal agencies to the extent that they used to. Instead, when deciding whether to consider agency interpretation of ambiguous language, they will use “Skidmore deference,” from the case Skidmore v. Swift & Co. Under Skidmore, the burden on agencies to justify their interpretation is much more stringent than under Chevron, holding agencies to a higher standard of persuasiveness. Justice Kagan’s dissent in Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo stated that “in one fell swoop, the majority today gives itself exclusive power over every

1 Chevron U.S.A., Inc. v. NRDC, Inc., et al., 467 U.S. 837 (1984).

2 Barczewski, Benjamin M. “Chevron Deference: A Primer.” Congress.gov, May 18, 2023. https://www.congress.gov/ crs-product/R44954/.

3 Loper Bright Enterprises et al.v. Raimondo. Secretary of Commerce, et al., 603 U.S. 3 (2024).

open issue—no matter how expertise-driven or policy-laden—involving the meaning of regulatory law.”4

Given the unprecedented speed of progress we are witnessing with AI, federal agencies are the entities best positioned to swiftly respond to and adapt dated statutes that should, but fail to, address the newest and most pressing AI-related issues. Granted, an alternative to regulation and litigation is the passing of new AI legislation. However, the recent razor-thin Republican majority in the House coupled with increasing political polarization has led to legislative gridlock on emerging issues, making timely new AI laws highly unlikely. Further, if new legislation does emerge, some experts believe that the velocity of AI progress could render the legislation outdated by the time it is passed.5 The process of seeking and attaining consensus may also end up favoring legislative focus on the simpler and easier to understand issues such as watermarking AI-generated content rather than more complex yet more important challenges of AI fairness or copyright disputes related to training AI models.

Leaving our AI future in the hands of the courts rather than feder-

CONTINUED ON PAGE 8

4 Loper Bright Enterprises et al.v. Raimondo. Secretary of Commerce, et al., 603 U.S. 84 (2024).

5 Wheeler, Tom. “The three challenges of AI Regulation.” Brookings, June 15, 2023. https://www.brookings.edu/ articles/the-three-challenges-of-ai-regulation/.

TheDepartment of Government Efficiency (DOGE) was established through an executive order at the beginning of President Trump’s second term. According to the order, the purpose of the department is to “[modernize] Federal technology and software to maximize governmental efficiency and productivity.”1 The United States Digital Service (USDS) was refashioned into the United States DOGE Service through this order. USDS was established in 2014 as a technology unit within the Executive Office of the President to improve government technology, such as updating government websites and streamlining federal hiring processes. DOGE, also established in the Office of the President, has been given an even higher level of authority, with the executive order demanding that DOGE have access to “all unclassified agency records, software systems, and IT systems.”2 This includes personal information that was previously held by the USDS.

The Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) guarantees that the information used by government agencies is shared with the general public. This act allows citizens to request access to records from any federal agency, unless the agency falls under one of the nine exemptions, which protect more sensitive material (e.g. national security, personal privacy, internal practices, law enforcement investigations, etc.).

1 White House. “Establishing and Implementing the President’s Department of Government Efficiency.” January 2025. https://www.whitehouse.gov/ presidential-actions/2025/01/establishing-and-implementing-the-presidents-department-of-government-efficiency/.

2 Id.

by ZOE NELSON STAFF WRITER

DOGE does not fall under any of the exemptions listed by FOIA. For the information held by DOGE to be considered an exemption, it would have to qualify as information that could create a serious invasion of privacy (such as attorney-client privilege) or threaten a compelling government interest (such as trade secrets or national security). There is an exemption for financial information, but only if it is confidential or privileged information, not public fi-

“Although executive administrators have stated that Elon Musk is simply a ‘Senior Advisor to the President’ and not in charge of DOGE, based on Trump’s and Musk’s public statements, it seems as though Musk is entirely in charge of DOGE’s operations.”

nances. The government claims that because DOGE is an executive advising board, it does not qualify as an independent agency subject to FOIA. However, the First Amendment Coalition filed a lawsuit against the agency in March to enjoin the agency from withholding these records, declaring that DOGE records are public information under FOIA. The coalition’s complaint alleges that DOGE serves as more than an executive advising committee, and that it wields substantial power and authority completely independent of the president, making

it an agency in its own right. Organizing major cuts to federal funding and freezing foreign aid payments, for example, are not within the scope of authority of a mere advisory committee. It concludes, “[First Amendment Coalition] has a legal right under FOIA to obtain the information it seeks, and there is no legal basis for the denial by USDS [United States DOGE Service] of said right.”3 DOGE might be in direct violation of FOIA if it does not release these records.

Citizen protection regarding information obtained by the government has evolved a lot over the last few decades. FOIA was first passed in 1966 to promote transparency and accountability and to check government power, championed by Democratic representative John E. Moss. Its main objective at the time was to address the overuse of government files marked “confidential” that didn’t need to be private information. However, even after FOIA was passed, there was bureaucratic pushback from government agencies, such as excessive delays and fees. It wasn’t until after the Watergate scandal that Congress really cracked down on FOIA, passing a bill to strengthen judicial oversight of document classification through a process called in camera review.4 This meant that the courts had the power to ensure whether a document was properly classified through a judge reviewing

CONTINUED ON PAGE 9

3 Courthouse News. “MSW Media v. Doge Complaint.” March 2025. https:// www.courthousenews.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/msw-media-vdoge-complaint-1.pdf/.

4 National Security Archive. “Veto Battle 30 Years Ago Set Freedom of Information Norms.” November 2004. https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu/NSAEBB/ NSAEBB142/index.htm/.

FROM

al agencies with specialized expertise could have other important ramifications. A judge or jury can hardly be expected to acquire and stay current on the in-depth technical knowledge about AI that can be necessary to shape the right boundaries around this rapidly evolving technology. Unless Congress takes aggressive action to strengthen AI legislation, this creates an environment where there is a lower chance that laws are interpreted in a manner that promotes regulation.

6 Plaintiffs will have an easier time fighting against the regulatory actions of federal agencies,7 and other bodies that propose solutions and advise on

6 Quinn, Kelsey. “How the U.S. Should Regulate AI After the End of Chevron Deference.” New Lines Institute, July 11, 2024. https://newlinesinstitute.org/strategic-technology/ how-the-u-s-should-regulate-artificial-intelligence-after-the-chevron-ruling/.

7 Bullock, Charlie. “What Might the End of Chevron Deference Mean for AI Governance?”. Institute for Law & AI, May 2024. https://law-ai.org/chevron-deference/.

such matters may also exert more caution in their development of regulation because they are more likely to be successfully challenged.8

Chevron’s reversal makes it all the more important that we pay attention to the risks that can arise from unregulated AI. A key issue is of AI alignment, or whether the actions of the new generation of frontier models9 like the large language models (LLMs) that underlie popular tools like ChatGPT and Claude are aligned with what is good for society in order to avoid possible inadvertent AI-made or AI-driven decisions that

8 Gray, Stacey. “Chevron Decision Will Impact Privacy and AI Regulations.” Future of Privacy Forum, June 28, 2024. https://fpf.org/blog/chevron-decision-will-impact-privacy-and-ai-regulations/.

9 Bullock, Charlie, Suzanne Van Arsdale, Mackenzie Arnold, Cullen O’Keefe, and Christoph Winter. “Legal Considerations for Defining ‘Frontier Model.’” Institute for Law & AI, September 2024. https://lawai.org/frontier-model-definitions/.

are at odds with human values or interests.10 Other issues include the possible proliferation of algorithmic bias and a potential lack of AI transparency.11 In our era of frontier models, AI can have unpredictable capabilities that even the developers may not fully understand during the course of their development. The incomplete definition of such frontier models in the legal sphere coupled with the reversal of Chevron compounds their risks — it is now the courts rather than expert federal agencies that may end up defining these systems and resolving the uncertainty regarding how laws which involve AI will be interpreted.

10 Conn, Ariel. Francesca Rossi Interview. Other. Future of Life Institute, January 26, 2017.

11 Sundararajan, Arun. “How Corporate Boards Must Approach AI Governance.” November 01, 2024. https://ssrn.com/ abstract=5016014/.

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 7

the unredacted versions of contested records (to determine whether they were exempt from disclosure).

In Kissinger v. Reporters Committee,5 a 1980 Supreme Court case, the Court delimited the meaning of agency records within FOIA, holding that “While the FOIA makes the ‘Executive Office of the President’ an agency subject to the Act, the legislative history makes it clear that the ‘Executive Office’ does not include the Office of the President.”6 In this case, the FOIA requests were in reference to Kissinger’s telephone conversations while he served as an Assistant to the President for National Security Affairs, which had been recorded by his secretaries and turned into summaries or transcripts. Thus, because the Office of the President was exempted from FOIA, any notes Kissinger had made while serving as Presidential

5 Kissinger v. Reporters Committee, 445 U.S. 136 (1980).

6 Id at 138.

Assistant did not constitute agency records subject to FOIA.

This complicates DOGE’s role as an executive advising committee. Technically, since it is established in the Office of the President, it would be exempt from FOIA requests under this ruling. However, if the First Amendment Coalition is correct, and DOGE acts completely independently of the president, then it is subject to FOIA. Although executive administrators have stated that Elon Musk is simply a “Senior Advisor to the President” and not in charge of DOGE,7 based on Trump’s and Musk’s public statements, it seems as though Musk is entirely in charge of DOGE’s operations. For example, on February 19, Trump stated, “I signed an order creating the Department of Government Efficiency and put a man named Elon Musk in charge.”8 Shortly after,

7 “MSW Media v. Doge Complaint.”

8 Bower, Anna. (@annabower.bsky. social), Bluesky (Feb. 19, 2025 6:11 PM),

on February 26, he stated, “I’m going to ask if it’s possible to have Elon get up first and talk about DOGE… So Elon, if you could get up and explain where you are, how you’re doing, and how much we’re cutting.”9

The implications of this are that Elon Musk, though he appears to be a mere advisor to the president, is likely actually heading up DOGE and all of its operations on his own. This would make DOGE’s refusal to comply with FOIA requests illegal.

at https://bsky.app/profile/annabower. bsky.social/post/3likvkcjnr22h/.

9 Trump: People who didn’t respond to ‘what did you do’ email are on the bubble, Scripps News (Feb. 26, 2025), at https:// www.youtube.com/watch?v=Jd-MlbvYles/.

by NICOLE OCHOA STAFF WRITER

In the aftermath of the highly publicized Ruby Franke child abuse case, Utah has joined Illinois and California in passing legislation regulating child influencers, specifically, minors who appear in monetized content created by their parents, often on family vlogging channels.1 Popular on YouTube, Instagram, and TikTok, family vlogging has become one of the most popular social media entertainment genres and often involves parents documenting and broadcasting their children’s daily lives for public consumption. This law, signed by the Utah Governor in March of 2025, takes steps towards protecting minors from monetized digital exposure, addressing the growing legal gap between traditional child labor protections and the rapidly expanding world of influencer media, despite its limited nature with state-level enforcement.

Ruby Franke, a prominent “momfluencer” known for her YouTube channel 8 Passengers, was sentenced up to 30 years in prison after pleading guilty to four counts of aggravated child abuse in early 2024. This case shocked the nation as at the channel’s height, it had 2.3 million subscribers and over 1 billion cumulative views.2 Franke’s early content

1 Laude, Camille. “Family Vlogging and Child Harm: A Need for Nationwide Protection.” American Bar Association. https://www.americanbar.org/content/ dam/aba/publications/Jurimetrics/ spring-2024/family-vlogging-and-childharm-a-need-for-nationwide-protection. pdf/.

2 Giorgis, Hannah. “The Cost of Perfection.” The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/culture/archive/2025/03/ devil-in-the-family-review-ruby-fran-

showcased routine family moments: morning wake-ups, school drop-offs, and mealtime rituals. However, as the channel gained popularity, the tone and substance of her videos began to shift. Her content began to feature invasive footage that blurred the line between parenting and exploitation. Content included recordings of her children being punished, private discussions about puberty, and even scenes of bra shopping, all presented as family entertainment. This shift in content masked a disturbing escalation in Franke’s parenting tactics. Viewers later learned that she had subjected her children to extreme disciplinary measures, including removing her oldest son’s bed for seven months, withholding meals, canceling holidays like Christmas as punishment, and sending their oldest son to a troubled teens camp. Though Child Protective Services were called to the home in 2020 and 2022,3 no charges were filed at the time. The true extent of the abuse would only come to light years later, underscoring how deeply harm can be concealed under the guise of digital content creation.

When one of her malnourished children escaped and sought help from a neighbor in August 2023,4 the story quickly unraveled. Investigators found evidence that Franke and her ke/682229/.

3 Rivera, Daniella, and Lofton, Shelby. “Concerns about Ruby Franke’s Children Reported to Police, DCFS More than a Year Ago.” https://www.ksl.com/article/50724629/concerns-about-rubyfrankes-children-reported-to-police-dcfsmore-than-a-year-ago/.

4 “Utah vs Franke/Hildebrandt.” Washington County of Utah, Guilty Plea Verdict. February 20, 2024. https://www. washco.utah.gov/departments/attorney/ case-highlights-media/utah-vs-franke-hildebrandt/.

business partner, Jodi Hildebrandt, had subjected multiple children to isolation, food deprivation, and extreme disciplinary measures, some of which had been openly discussed or alluded to on their channel. The case became a grim example of how the pursuit of content and “discipline for the camera” can spiral into abuse, especially when legal oversight fails to keep pace with the influencer economy. In direct response to the growing concerns over child influencers, Ruby Franke’s oldest daughter, Shari Franke, and husband, Kevin Franke, advocated to Utah lawmakers for stronger safeguards to be put in place for child influencers. Shari Franke testified to the Utah Senate that, “When children become stars in their family’s online content, they become child influencers. It is more than just filming your family life and putting it online. It is a full-time job, with employees, business credit cards, managers, and marketing strategies.”5 Following these testimonies, House Bill 322 (H.B. 322) was passed and signed by Governor Spencer Cox, set to take effect May 7, 2025.6 The law defines participation in monetized digital content as a form of labor for minors, aligning them with traditional child performers. If a family earns over $20,000 per calendar year from content featuring their children, at least 15% of the child’s portion must be deposited into a trust account, accessible at age 18. Children also gain

5 “Business and Labor Interim Committee Hearing - October 16, 2024.” Business and Labor Interim Committee. https:// le.utah.gov/av/committeeArchive.jsp?mtgID=19498/.

6 “H.B. 322 Child Actor Regulations Bill.” Utah State Legislature. https://le.utah. gov/~2025/bills/static/HB0322.html/.

“When children become stars in their family’s online content, they become child influencers. It is more than just filming your family life and putting it online. It is a full-time job, with employees, business credit cards, managers, and marketing strategies.”

shari franke’s testimony to the utah senate

the right, upon reaching adulthood, to request the deletion of videos in which they appear. The requirement for the money to be set aside mirrors the structure of the Coogan account system, popular for child stars in movies and television. Named after Jackie Coogan, a child actor in the 1930s who found after he had turned 18, none of his earnings from his previous work were saved, the Coogan Law was established to prevent parents from mismanaging or spending a child performer’s earnings.7 California, New York, Illinois, Louisiana, and New Mexico all require some form of a blocked trust account for child performers. This development follows California’s recent laws AB 18808 and SB 764,9 expanding the Coogan Law

7 “California Child Actor’s Bill Section 6752 - Coogan Law: Full Text.” SAG-AFTRA, accessed May 6, 2025. https:// www.sagaftra.org/membership-benefits/young-performers/coogan-law/coogan-law-full-text/.

8 “AB-1880 Minors: Artistic Employment.” Bill Status - AB-1880 Minors: Artistic Employment., https://leginfo. legislature.ca.gov/faces/billStatusClient. xhtml?bill_id=202320240AB1880/.

9 “SB-764 Minors: Online Platforms.” Bill Status - SB-764 Minors: Online Platforms., https://leginfo.legislature. ca.gov/faces/billStatusClient.xhtml?bill_ id=202320240SB764/.

and redefining what constitutes a content creator.

Unlike traditional media industries, influencer content creation is incredibly decentralized, non-unionized, and driven by self-reporting financials. The law relies heavily on self-reporting and platform compliance. Key areas of ambiguity remain. For example, the statute does not clearly delineate how disputes over income allocation will be resolved, what penalties apply for noncompliance, or whether children are entitled to independent legal counsel in such cases. Also, there are some concerns about “regulatory flight”, the idea that content creators may relocate to less-regulated areas. For example, after California passed its legislation, creators such as The LaBrant Family, Cecily Bauchmann, and Brittany Xavier moved to Tennessee, a state without child influencer protections.10 However, these individual cases do not necessarily indicate a widespread trend. Even marginal reductions in exploitative family content would still represent

10 “‘Bad Influence’ and ‘The Devil in The Family’ Highlight the Dark Side of Kid Influencers.” The New York Times. https:// www.nytimes.com/2025/04/16/arts/ television/kid-influencer-ruby-franke-piper-rockelle.html/.

a meaningful gain in protecting children’s rights.

Ultimately, Utah’s law is a positive legal development that acknowledges the need to regulate children’s participation in monetized digital media. It represents an important recognition that children are not simply “extras” in family content, but workers entitled to protection. As the lines between private family life and public entertainment continue to blur, lawmakers, legal scholars, and child advocates face an urgent challenge: creating a digital rights framework that centers children’s autonomy, privacy, and long-term well-being, not just their earning potential.

by DEVON JIANG STAFF WRITER

You can’t have your cake and eat it too—but maybe you can.

Double-dipping is typically unethical. For instance, claiming the cost of losses from multiple insurers for the same incident is fraud and prosecutable.1 What happens when double-dipping benefits the parties on the other end of the dip? For distressed companies, double-dip transactions present a vital opportunity to raise capital.

When a company no longer has sufficient revenue to pay off its debt, it becomes distressed because it cannot meet its financial obligations. The company wants to avoid prolonging this state before creditors force it into bankruptcy, which causes lost assets and potential liquidation. At Home, a struggling home decor brand, faced this potential scenario and quickly needed cash in 2023.2 By creating a subsidiary company, At Home could take a loan from its subsidiary, which itself would take a loan from creditors, in exchange for an intercompany note. That loan comes from creditors, who now have a direct dip against At Home and a second indirect dip on its subsidiary. In other words, creditors now have two ways to recover their loan in bankruptcy proceedings. Large creditors found this arrangement attractive because it de-

1 See 18 U.S.C. § 1033 (“Whoever… knowingly, with the intent to deceive, makes any false material statement…shall be punished”).

2 See At Home Group Inc. Subsidiary Senior Secured Debt Rating Raised To ‘CCC’ After Error Correction. S&P GLOB. (Oct. 2, 2023) [hereinafter CCC]. https:// disclosure.spglobal.com/ratings/en/ regulatory/article/-/view/type/HTML/ id/3065440/.

creased the risk of not recovering their loan and credited $200 million to the subsidiary despite its parent company being distressed. Their two claims became pari passu (on equal footing) to existing senior loans if they needed to recover loans during bankruptcy. Double-dipping is controversial because it allows creditors to ‘jump the line.’ If a once high-ranking debt— known as a first-lien term loan—now has to share its seniority status with a double-dip creditor, its owner might recover less money during restructuring. In Chapter 11 bankruptcy proceedings, the law also makes clear that creditors are “entitled only to a single satisfaction.”3 At Home, therefore, could not develop a double-dip transaction if it were in Chapter 11 protection; courts would find the arbitrary duplication on a similar liability dubious. Even though double-dip transactions could take place outside Chapter 11 protection, there are other reasons why it may present ethical and legal problems. Bankruptcy courts can “inquire into the validity of any claim”4 and refuse to honor it if it is without lawful existence, made in bad faith, or is inherently unfair.5 Pepper v. Litton, 308 U.S. 295 (1939). By ruling that “substance will not give way to form,” the justices gave the bankruptcy courts flexibility because judges must focus on protecting multiple, often competing, interests.6 When an interested creditor leverages the debtor’s position to gain advantages in bankruptcy proceedings, such an agreement may not be in good faith. The courts can redress this imbalance by subordinat-

ing part of a claim.7

While senior creditors complain that double-dips are not good faith transactions, they may have to accept its existence. Debtors propose it to creditors in good faith for the survival of a company. When At Home needed liquidity, it had a CCC rating from S&P Global Ratings, meaning that At Home was nearly in default.8 Given the low rating, creditors need an attractive return to compensate for the risk. Double-dips helped Redwood Capital Management and other creditors justify extending the maturities of their debt, ultimately preventing At Home from entering Chapter 11.9 Courts prefer parties to find an agreement outside bankruptcy protection in order to avoid selling assets or liquidation, which would be “a disastrous result for…creditors.”10 In re General Motors Corp., 407 B.R. 403 (Bankr. S.D.N.Y. 2009). In the short term, injecting liquidity into a distressed company is in the best interest of mitigating the effects of Chapter 11 bankruptcy. It gives the company more time to relieve its liabilities when no other arrangement is tenable, making it a good faith act under 11 U.S. Code § 1129(a)(3). Existing creditors benefit, too, because they no longer face immediate risk of unrecoverable loans.

Senior creditors may push

7 See 11 U.S.C. § 510(c) (“the court may…subordinate for purposes of distribution all or part of an allowed claim to all or part of another allowed claim”).

8 CCC, supra note 2.

3 11 U.S.C. § 550(d).

4 Pepper v. Litton, 308 U.S. 295 (1939).

5 Id. At 306.

6 Id. At 305.

9 See Frumes, Max. Special Situations Insight: At Home Group Transaction May Be the First Intentional ‘Double-Dip’ Financing; It Won’t Be the Last. CREDITSIGHTS (Jun. 2, 2023). https://know. creditsights.com/special-situations-insight-june-2023/.

10 In re General Motors Corp., 407 B.R. 403 (Bankr. S.D.N.Y. 2009).

“While senior creditors complain that double-dips are not good faith transactions, they may have to accept its existence.”

back that multiple parties cannot assert claims on the same loans because it results in a forbidden duplicative recovery scheme.11 Double-dips, though, are different from the rulings against filing restitution damages and preference recovery on the same liability. The two dips collect from different estates—the parent company and its subsidiary—in the same way that a creditor can claim liabilities from two separate loans. In those circumstances, the creditor has the right to assert the full value of its claims.12 The debtor cannot force the lender to consolidate contractually-backed loans unless they recover more than their original loans. Similarly, a double-dip creditor is eligible to secure recovery through two claims. As long as the claims follow state laws and the U.S. code, the courts must honor and consider their underlying contract.13 The debtor can ensure it fulfills legal obligations by making its subsidiary unrestricted or non-guarantor restricted. By establishing either type of subsidiary, the company does not blend double-dip documents with the covenants of ex-

11 See In re Lyondell Chemical Co., 402 B.R. 596 (Bankr. S.D.N.Y. 2018).

12 See Ivanhoe Building & Load Assn. v. Orr, 295 U.S. 243 (1935).

13 See Travelers Casualty & Surety Co. of America v. Pacific Gas & Elec. Co., 549 U.S. 443 (2007).

isting credit documents.

Double-dipping is a novel and increasingly popular maneuver for both debtors and creditors. The practice began two decades ago as a fortuitous observation during the convoluted Lehman Brothers restructuring process.14 Now, distressed companies can engineer these loans as a hail mary to balance their sheets. Wheel Pros— an aftermarket for automotive wheels and accessories—recently became the first company to declare Chapter 11 bankruptcy despite its double-dipping efforts.15 In these restructuring proceedings, the company settled with first-lien term loan holders out of court over their objections. As complaints become more apparent with increasing double-dip transactions, bankruptcy courts should increase scrutiny on this issue. Similar to how debtors pushed the legal boundaries

14 See Declercq, Peter J.M.. Some Lessons Learned from the Lehman Brothers Insolvency – The LBT Notes. INSOL INT’L (2012). https://brownrudnick.com/ wp-content/uploads/2016/12/brown_ rudnick_some_lessons_learned_from_ lehman.pdf/.

15 See Hillier, Sam. ‘Double Dip’ Credit Structure Faces First Restructuring Test With Wheel Pros’ Possible Chapter 11. TRANSACTED (Sept. 6, 2024). https:// www.transacted.io/double-dip-creditstructure-faces-first-restructuring-testwith-wheel-pros-possible-chapter-11/.

with drop-downs,16 non-pro rata uptiers,17 and Texas Two-Step bankruptcies,18 distressed companies will create more complex transactions until the court rules that such innovation becomes unfair. For now, though, double-dipping can yield a mutually beneficial outcome: a direct benefit for debtors and an indirect benefit for every creditor.

16 See Ayotte, Kenneth, and Sully, Christina. J. Crew, Nine West, and the Complexities of Financial Distress. YALE L.J. (Nov. 10, 2021). https://www.yalelawjournal.org/forum/j-crew-nine-west-andthe-complexities-of-financial-distress.

17 See N. Star Debt Holdings L.P. v. Serta Simmons Bedding LLC, No. 652243/2020, 2020 WL3411267 (N.Y. Sup. Ct. June 19, 2020).

18 See Hu, Charlie. Court Rejects Johnson & Johnson’s Use of the “Texas TwoStep” to Tackle Baby Powder Liability. U. CHI. BUS. L. REV. (2023). https://businesslawreview.uchicago.edu/online-archive/ court-rejects-johnson-johnsons-use-texas-two-step-tackle-baby-powder-liability/.

by CYRAH GAYLE STAFF WRITER

Fraternities and sororities are as old as this nation.1 And though the first reported case of hazing in the United States is considered to be in 1838 with the death of John Butler Groves, it is nearly certain that fatal hazing incidents occurred much earlier but were never reported.2 With hazing being a tale as old as time, how will state and federal laws address the fatal consequences of hazing? In this article, I will examine current legislation to better understand the implications that these laws have on the future of fraternity and sorority organizations.

Only two months after former President Joe Biden signed the “Stop Campus Hazing Act” into effect, the unfortunate death of a Southern University student, Caleb Wilson, shook the world of fraternities and sororities once again. The federal act “requires institutions of higher education (IHEs) that participate in federal student aid programs to report hazing incidents” and defines hazing as any intentional, knowing, or reckless act committed by a person (whether individually or in concert with other persons) against another person or persons regardless of the willingness of such other person or persons to participate, that (1) is committed in the course of an initiation into, an affiliation with, or the maintenance of mem-

1 “History of Fraternities/Sororities.” Appalachian State University Fraternity and Student Life. Accessed May 21, 2025. https://fsl.appstate.edu/history-ofgreek-life/.

2 The Doan Law Firm. “History of Fraternity Hazing.” Accessed May 21, 2025. https://www.thedoanlawfirm.com/fraternity-hazing/history-of-fraternity-hazing/.

bership in, a student organization (e.g., a club, athletic team, fraternity, or sorority); and (2) causes or creates a risk, above the reasonable risk encountered in the course of participation in the IHE or the organization, of physical or psychological injury.3

Although an important legislative milestone, the “Stop Campus Hazing Act” has not put a stop to hazing on college campuses, in part, because it remains difficult to enforce. One of the deficiencies of the act is that it places the burden of responsibility on the university, which are often reluctant to chastise its charters due to the financial benefits from the fraternities.

The University of Chicago (UChicago) which boasts of only 21 fraternity and sorority organizations is incomparable to Greek-oriented universities such as the University of Alabama, which is home to over 70 fraternity and sorority organizations.4 If a smaller school like UChicago is tied into the politics of pleasing its Greek-life alumni, how much more so are larger public schools? Ultimately, this significantly decreases the likelihood that universities will hold these organizations responsible. Even if public universities were to hold their schools’ charters responsible, how could punishments

3 Congress.gov. “H.R.5646 - 118th Congress (2023-2024): Stop Campus Hazing Act.” December 23, 2024. https://www. congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/housebill/5646/.

4 “Chapters List.” University of Alabama Division of Student Life, Fraternity and Sorority Life. Accessed May 21, 2025. https://ofsl.sa.ua.edu/chapters-list/; Staff of the Maroon, “Sororities and Fraternities at UChicago.” Chicago Maroon, September 23, 2019. https://chicagomaroon. com/27132/news/greek-life-uchicago/.

be enforced? Most, if not all, national chapters of fraternities and sororities include rulebooks that strictly prohibit the use of hazing. And yet, when this rule is obviously violated, national chapters very rarely face repercussions for their lack of enforcement and their frequent permissiveness of hazing.5

In the case of Caleb Wilson, there is little evidence to suggest that the national chapter faced repercussions for the Southern University charter’s actions. In fact, the only consequence that can be easily located is that the university ordered the fraternity’s chapter to “cease all activities” and has “banned all Greek organizations on campus from taking in any new members at least through the remainder of the academic year.”6

It is apparent that local chapters suffer reputational damage and public backlash when these cases occur, but very rarely do they impact these organizations at the national chapter level, which arguably has the most power to change the dynamics of its local charters. For federal law against hazing to be efficient, it must be proactive (not just a reaction to another unfortunate event) and have an impact on the fraternity and sorority organizations in the local and international chapters. Lives truly depend on it.

5 Marcuccio, Elizabeth and McCollum, Joseph P. “Hazing on College Campuses: Who is Liable?.” 2011. North East Journal of Legal Studies: Vol. 22, Article 2. https:// digitalcommons.fairfield.edu/nealsb/ vol22/iss1/2/.

6 Brown Chau, Nicole. “Caleb Wilson Died after an Alleged Fraternity Hazing Incident. Here’s What We Know.” CBS News, March 13, 2025. https://www. cbsnews.com/news/caleb-wilson-hazing-death-omega-psi-phi/.

“SHAME

by CHRISTINE LEE STAFF WRITER

CONTENT WARNING: This material contains description of sexual assault and discussion of a court case involving sexual assault and abuse.

WhenGisele Pelicot unexpectedly suffered from memory lapses and lost hair and weight, she believed her husband, Dominique Pelicot, was supporting her by driving her to medical appointments. To her, they were a happy retired couple, living in Mazan, France, after raising three children and working in the Paris region. After specialists could not diagnose the cause of her experiences, her husband insisted she had early symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease. If a security guard had not caught Dominique recording under women’s skirts at a supermarket, an investigation may have never revealed that Dominique was secretly drugging and raping Gisele. Authorities found hundreds of images and videos of Dominique (and other men) sexually assaulting Gisele on Dominique’s hard drive. In the last decade, Dominique drugged and raped Gisele over 200 times, inviting 72 men he met in online chat rooms to their home in Mazan to join him. At the end of 2024, Dominique and 50 other men were on trial for rape. Gisele’s trial against the fifty-one men made it evident that she endured two types of preventable gender-based violence: the physical harm of being violated by so many men initiated by her husband, and the psychic harm of having to relive this violence while fighting for her dignity and autonomy in a public court case.

The sexual violence against Gisele marked an act of immense and irreparable physical harm, but by putting this act in the larger context of French

law and culture, it becomes clear that this extreme outcome does not necessarily represent an anomaly. While Dominique received the highest sentence of twenty years for aggravated rape, many of the other rapists received shorter sentences than prosecutors sought. A few received only suspended sentences, which meant they were put on probation instead, with the possibility of the original sentence being enforced if probation conditions are violated, allowing them to walk free.1 These lenient sentences are the result of the definition of rape in French law, which puts forward no concept of consent.

According to French law, rape is defined as a penetrative act or oral sex act committed on someone using “violence, coercion, threat or surprise.”2 The lack of a concept of consent deprives survivors of sexual assault of a legally defined, foundational understanding of bodily autonomy. Without a shared understanding of consent or recognition of humanity in sexual settings, the #MeToo movement, meant to empower survivors of sexual misconduct, experienced delays and faced fierce backlash in France after gaining initial global recognition in 2017, reflecting a culture that silences the stories of survivors.3 According to

1 Vandoorne, Saskia, Niamh Kennedy, Caroline Baum, Kara Fox, Charlotte Dotto, Eleanor Stubbs, Yukari Schrickel, and Byron Manley. “Interactive: How Dominique Pelicot Organized France’s Worst Sex Crime in a Generation.” CNN, December 17, 2024. https://www.cnn.com/ interactive/2024/12/europe/gisele-pelicot-france-case-messages/.

2 Directorate for Legal and Administrative Information (Prime Minister). “Viol commis sur une personne majeure (Rape of an adult).” August 10, 2023. https:// www.service-public.fr/particuliers/ vosdroits/F1526/.

3 Onishi, Norimitsu. “Powerful Men Fall, One After Another, in France’s Delayed #MeToo.” The New York Times,

France’s Institute of Public Policies, 94% of rapes between 2012 and 2021 were never prosecuted or never came to a trial.4 Without proper accountability, sexual violence becomes accepted and even enabled within society. The 50 men on trial who accepted Dominique’s invitation to come to his home to rape Gisele were not known criminals but ordinary men—people you could pass while buying groceries or stand behind in line for coffee. There is no pattern by age, job, relationship status, or social class. Yet, despite raping the unconscious woman, 36 of the men pleaded not guilty, claiming they were deceived and forced by Dominique because he told them that Gisele was pretending to be asleep. Moreover, not one of these men saw the helpless, drugged woman and sought to help her by leaving and going to the police. Even without the question of accountability, the effects of rape are devastating. As a result of her own experience in regards to the sexual assaults specifically, Gisele says, “I’ve lost ten years of my life,” adding that her life is a “field of ruins.”5 According to The Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network of the United States, 30% of women who survive rape report symptoms of Post Tramatic Stress Disorder nine

CONTINUED ON PAGE 17

April 8, 2021. https://www.nytimes. com/2021/04/08/world/europe/francemetoo-sandra-muller.html.

4 “Le traitement judiciaire des violences sexuelles et conjugales en France.” Institut des Politiques Publiques.” April 3, 2024. https://www.ipp.eu/publication/ le-traitement-judiciaire-des-violences-sexuelles-et-conjugales-en-france/.

5 Linder, Esther. “Victim Recounts ‘scenes of Horror’ as French Trial Is Told Husband Drugged and Raped Her for a Decade.” ABC News, September 6, 2024. https://www.abc.net.au/ news/2024-09-06/french-victim-ofdrugging-and-sexual-assault-speaks-attrial/104318494/.

Abigantitrust lawsuit has hit the sport of tennis. The Professional Tennis Players Association (PTPA) has brought forward an antitrust lawsuit against the governing tennis bodies in the United States, the United Kingdom, and the European Union: Association of Tennis Professionals (ATP) Tour, Women’s Tennis Association (WTA) Tour, International Tennis Federation Ltd, and the International Tennis Integrity Agency Ltd.1 Antitrust law is jurisprudence dedicated to fostering fair and competitive markets. In an antitrust lawsuit, the plaintiff argues that the defendant acted in a way that would restrict competition (e.g., a merger and acquisition that could potentially lead to a monopoly being created). That is exactly what the PTPA is arguing: the governing bodies that represent the defendants have made a collective effort to restrict professionally ranked tennis players from competing in tournaments not owned by the governing bodies,2 leading to a considerable loss in income for the affected players.

The antitrust lawsuit brought forward by the PTPA is the first of its kind. The ATP is the global governing body for men’s tennis,3 whereas the WTA serves as the global governing body for women’s tennis.4 One of the

1 Fuller, Russell. “Players v Tennis Tours: What Is the PTPA Lawsuit, What Does It Want and What Happens Next?” BBC Sport, March 19, 2025. https://www. bbc.com/sport/tennis/articles/c78ey959q64o/.

2 Pospisil et al v. ATP Tour, Inc. et al, No. 1:2025cv02207, Complaint. https:// www.ptpaplayers.com/wp-content/ uploads/2025/03/Pospisil-et-al.-v.-ATPTour-Inc.-et-al.-Complaint.pdf/.

3 “About ATP Tour Tennis.” ATP Tour. Accessed May 21, 2025. https://www. atptour.com/en/corporate/about/.

4 “About the WTA.” WTA Tennis. Accessed May 21, 2025. https://www. wtatennis.com/about/.

by SIMON CAMELO STAFF WRITER

complaints holds that both governing bodies essentially force their players to overcompete, given that both governing bodies have certain participation requirements in their respective rulebooks, leading to a strenuous schedule for affected players, and serving as an extra burden is penalties for failing to meet the participation requirements.5

Regarding the appropriate jurisdiction, the Southern District of New York was the legal governing body that received the complaint from the plaintiffs. Therefore, legal precedent exists that can favor both parties. On September 30, 2015, O’Bannon v. National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) was decided. This was the highly awaited lawsuit that allowed collegiate athletes in the United States to be compensated for their likeness and image. In specific, the panel found that the NCAA’s amateurism restriction towards collegiate athletes from receiving compensation on the basis of name, image, and likeness, or NIL, violates Section 1 of the Sherman Act.6 O’Bannon v. NCAA has some overlap with the current lawsuit at hand, as some of the complaints regard unfair prevention of player participation in outside tennis affairs, which restricts the players from utilizing their name to advance themselves, and thus sets up a massive barrier for entry.7 In addition, the governing bodies force the tennis players to sign non-compete contracts and essentially force the tennis players to give up NIL rights.8 However, a key factor in O’Bannon v. NCAA is that the NCAA

5 Pospisil et al v. ATP Tour, ¶177-187.

6 O’Bannon v. NCAA, No. 14-16601 (9th Cir. 2015). https://law.justia.com/ cases/federal/appellate-courts/ca9/1416601/14-16601-2015-09-30.html/.

7 Id.

8 Id.

was not granting NIL compensation as they saw the athletes under their jurisdiction as amateurs. Neither the ATP nor WTA use the same justification for their compensation efforts or scheduling efforts, so drawing parallels for the plaintiff may be a burden to overcome.

This is not the only sport where the athletes involved are complaining due to strenuous schedules. A coalition in Europe, comprised of some of the biggest soccer leagues in the world, filed a lawsuit against FIFA, the main governing body of worldwide soccer, alleging issues with their expansive match schedules.9 Although no legal decision has been made for either lawsuit, one potential implication is a restructuring of athletic contracts. For a sport like soccer, contracts are structured to last a certain amount of time and are valid until the expiration date, or when there is a bilateral agreement to terminate the contract, or when a party involved in the contract has breached the contract in a severe enough way to make the terminating party unable to continue the contractual relationship.10 In a world where the legal conclusion of the regarded lawsuits is in favor of the plaintiffs, this may allow athletes to limit their participation in their respective sporting events. If players are able to decide to play less, then there may be further implications regarding contractual negotiations between sponsors and players

A differentiating factor between ATP Tour and WTA Tour and Ameri-

9 “FIFPRO, Leagues to File Antitrust Suit vs. FIFA.” ESPN. October 11, 2024. https://www.espn.com/soccer/story/_/ id/41736531/fifpro-leagues-file-antitrustsuit-vs-fifa-monday/.

10 Alexandria Union Club v. Juan José Sánchez Maqueda & Antonio Cazorla Reche, award of 26, August 2014.” CAS 2014/A/3463 & 3464, ¶54.

can sporting bodies is the governing size. Leagues such as the National Basketball Association, the National Hockey League, Major League Baseball, and the National Football League are governing bodies over their respective sports, in which most of the teams involved are entirely American, apart from a few teams

“SHAME

that participate from Canada. Therefore, in a hypothetical scenario where the respective player’s association or union were to feel as though an injustice was committed against them, the plaintiff in those hypothetical cases would be able to simply refer to American antitrust laws and labor laws and claim that an injustice

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 15

months after the assault, 33% of women who are raped contemplate suicide, and 13% of women who are raped attempt suicide.6

Aside from the experience of a dehumanizing and annihilating assault, survivors of sexual violence who are able to take their case to court experience trauma from reliving their experience under public scrutiny. The issue of sexual violence embedded in culture extends beyond the act itself to scrutiny of the survivor and lack of access to resources to protect their dignity and health. A closer look into the trial reveals the obstacles and horrors Gisele had to face in order to reclaim her narrative and humanity. The experience of the trial proved to be gruelling, as Gisele says, “I understand why rape victims don’t press charges.”7 Defense lawyers displayed 27 intimate photos of Gisele that exposed her private body parts to the court. They reasoned that the sexually explicit photos of Gisele in Dominique’s invites led them to believe that Gisele was willing to have sex with them.8 In response, Gisele

6 “Victims of Sexual Violence: Statistics.” Rape, Abuse, & Incest National Network (RAINN). https://rainn.org/statistics/victims-sexual-violence/.

7 Clement, Megan. “Opinion: Gisèle Pelicot’s Horrifying Rape Trial Has Changed France.” New York Times. December 19, 2024. https://www.nytimes. com/2024/12/19/opinion/gisele-pelicot-rape-trial.html/.

8 Seckel, Henri. “Plaintiff Comes under Attack at Pelicot Trial: ‘I Under-

was committed under American jurisdiction. However, the lawsuit at hand regards a sole, worldwide governing body over tennis, consisting of players from countries all over the world. Therefore, it can be predicted that one of the main legal questions of this lawsuit is the proper jurisdiction.

GISELE PELICOT’S TRIAL AND CALL FOR. . .

remained defiant, saying “he still should have asked for my consent.”9 When asked about her decision to open her trial to the public at the cost of her privacy, Gisele expressed that she does not regret her decision, refusing to feel shame and protesting patriarchal society for stigmatizing survivors of sexual assault and trivializing their trauma: “I’m also thinking of the unrecognized victims whose stories often remain in the shadows. I want you to know that we share the same struggle.”10 To Gisele, justice would require more than just a guilty verdict. It would mean a cultural and legal paradigm shift toward mutual respect across genders, where there would be preventative measures to minimize gender-based violence from taking place and support systems to preserve dignity in the rare

stand Why Rape Victims Don’t Press Charges.’” Le Monde, September 19, 2024. https://www.lemonde.fr/en/france/ article/2024/09/19/victim-comes-under-attack-at-pelicot-trial-i-understandwhy-rape-victims-don-t-press-charges_6726617_7.html/.

9 Porter, Catherine & Ségolène Le Stradic. “France’s Horrifying Rape Trial Has a Feminist Hero.” New York Times, September 25, 2024. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/09/25/world/europe/ france-rape-trial-gisele-pelicot.html/.

10 Staff of Le Monde with Agence France-Presse (AFP). “Gisèle Pelicot ‘never regretted’ opening French mass rape trial to public.” Le Monde and AFP, December 19, 2024. https://www. lemonde.fr/en/police-and-justice/article/2024/12/19/gisele-pelicot-never-regretted-opening-french-mass-rape-trialto-public_6736257_105.html/.

case that such transgressions did occur. Gisele’s trial serves as a landmark case, strengthening the movement to include consent in French law. Members of the French Parliament Véronique Riotton from President Emmanuel Macron’s Renaissance Party and Marie-Charlotte Garin of the Ecologists Party spearheaded a panel advocating for the inclusion of consent in rape law.11 Fourteen other EU states, including Germany, Sweden, and Spain, already include the notion of consent in their legislation. Moreover, members of Parliament hope to address the culture that serves perpetrators of sexual violence in France. Updating the law is another step in the process toward dismantling a culture that accepts sexual violence. Nonetheless, empowering and supportive communal behaviors such as listening to survivors and providing mental health support are needed to rebuild the culture of justice that Gisele and other feminists envision. Today, Gisele’s face and words have been memorialized in murals on many streets of France as symbols of hope and courage. With more systemic and cultural change, Gisele Pelicot, along with every other survivor, may see justice.

11 Chrisafis, Angelique. “France Needs ‘Clearer’ Rape Laws That Include Consent, Report Finds.” The Guardian, January 21, 2025. https://www.theguardian. com/world/2025/jan/21/france-needsclearer-laws-that-include-consent-reportfinds/.

by OVIA SUNDAR STAFF WRITER

The California Consumer Privacy Act, or CCPA, is a landmark policy passed in 2018, giving “consumers more control over the personal information that businesses collect… provid[ing] guidance on how to implement the law.”1

Per the bill’s original text, consumers in California with the passage of the CCPA have the right to know how their information is used and shared, to delete their personal information, and to opt out of the sale of said information.2 Businesses are now held to these standards in their use and sale of private information, especially during privacy breaches, with the inclusion of a key private right to action clause that allows consumers to hold data security negligence accountable, among other things.3 Since the CCPA’s inception, various additions have also been made, increasing the bill’s scope and providing consumers with even more protections against the opaque use of their personal information.

The CCPA is particularly unique within the United States. Similar legislation on the global stage in-

1 “California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA).” State of California Department of Justice Office of the Attorney General. Last modified 2024. https://oag.ca.gov/ privacy/ccpa/.

2 CCPA, State of California Dept. of Justice Office of the Attorney General.

3 Id.

cludes the EU’s GDPR,4 or the General Data Protection Regulation, which regulates the sale, access, and use of personal data by companies inside the EU, as well as those handling the data of EU residents outside of the EU. The CCPA was the first policy in the US to regulate the use and sale of consumers’ data from within the US.

The CCPA passed with a unanimous vote from the California State Legislature. Proving to be a solid foundation for consumer privacy protections, the bill was further amended to add the California Privacy Rights Act, or CPRA,5 in 2020. The CPRA added consumers’ right to change inaccurate personal data that has been collected about them, and also to limit the use and disclosure of their collected personal data, among other things. The CPRA expanded on the CCPA’s foundation to be more comprehensive in its protections and the rights it provided.

Before the passage of the CCPA, consumers had no concrete way to manage the sale and use of their data once companies obtained it. The CCPA sought to change that dynamic. It gave consumers the right to request that companies disclose specific data collected, the category it belongs to, the

4 Wolford, Ben. “What is GDPR, the EU’s new data protection law?” GDPR.edu. https://gdpr.eu/what-is-gdpr/.

5 “CPRA Regulations: Unraveling the California Privacy Rights Act.” Scrut Automation. Last modified 2023.

category of the source from which it is collected, what the company intends to do with the data, why it was collected, and the categories of parties to which the data is shared.

Consumers in California now have the right to access their data. Under the CCPA, companies that have collected a customer’s data within the past year must comply with these requests if made by the consumer. This provides a pivotal opportunity for consumers to have grounds to challenge or question the use of their data, as the data sold is now visible. The demand for data, as well as the types of data collected, has exploded in the past few decades. Data collection and management alone is a multibillion-dollar industry,6 and the increase in personalized online and business experiences means data is becoming increasingly valuable to companies of all kinds.

Per the CCPA, personal data is data that can be “reasonably linked”7 to the consumer. This includes name, contact information, education history, and the like, but also location data, account numbers, browsing history, device IDs, and more. The definition

CONTINUED ON PAGE 20

6 “Data Collection And Labeling Market Trends.” Grand View Research. Last modified 2024. https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/data-collection-labeling-market/.

7 “Definition of Personal Data.” DLA Piper Intelligence. https://www.dlapiperdataprotection.com/?t=definitions&c=US/.

by JOLIN LIU STAFF WRITER

The California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA), enacted in 2018 and in effect since 2020, has been widely regarded as a landmark in U.S. privacy legislation. Modeled in part on the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), the CCPA grants California residents rights to access, delete, and opt out of the sale of their personal data. While the law represents a significant step toward better consumer privacy protections, this essay examines concerns in the law’s real-world implementation—limitations that, if addressed, could strengthen the CCPA and help it better fulfill its original promise.

One of the most pressing issues is the law’s low rate of consumer engagement. According to a 2020 survey by the Interactive Advertising Bureau (IAB), opt-out rates for data “sales” across websites, mobile apps, and connected television platforms ranged from just 1% to 5%.1 Likewise, most companies reported receiving fewer than 100 access or deletion requests per year. Although the number of data subject requests (DSRs) rose by 246% from 2021 to 2023—from 248 to 859 requests per million identities—this growth is relative to an

1 Interactive Advertising Bureau, CCPA Benchmark Survey, November 2020. https://www.iab.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/IAB_CCPA_Benchmark_ Survey_Summary_2020-11.pdf/.

already initially negligible base, and its absolute participation rate still remains low at approximately 0.08%.2 This indicates that even now, most consumers either are unaware of their rights or find the process too burdensome to pursue.

In fact, the procedures for submitting data requests can be opaque and discouragingly complex. Users may be required to fill out detailed forms, upload government-issued IDs, or navigate poorly designed interfaces to locate request portals. These barriers are not merely accidental. Businesses have strong incentives to limit data disclosures, as transparency could alarm users or prompt them to withdraw consent, while widespread requests also risk exposing internal practices to competitors.

In a recent university course titled Surveillance Aesthetics: Provocations About Privacy and Security in the Digital Age, co-taught by the Computer Science Department at the University of Chicago and the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, students were asked to restore their digital profile by requesting data from commonly used applications. We were advised to start a month in advance due to expected delays. Navigating company websites to find data request portals

2 Transcend, 2024 Data Privacy Trends Report. https://transcend.io/ research/2024-data-privacy-trends

proved frustrating: options were often hidden deep in menus, labeled inconsistently in different terms, or styled in faint gray text compared to other black, bold tabs. Companies also segmented data into opaque subcategories, making it difficult to know what each contained in advance; therefore, users have to select the subcategories manually one by one in order to receive a fuller version. Moreover, some firms required outdated communication methods, such as fax. Out of nine companies I contacted, only four responded within a month via email. Most entries of the data returned was information already visible in the app, with only a few revealing insights into targeted profiling, tracking of privacy, and digital surveillance. These points of friction appear strategically designed to deter requests or overwhelm users with irrelevant data. This is similar to how users routinely default to accepting lengthy “I agree to the terms” pages. While anecdotal, this experience highlights the broader structural barriers consumers face when attempting to exercise their data rights, which likely contribute to the CCPA’s persistently low engagement with data subject requests.

Another major weakness lies in how companies have reinterpreted the law’s language to avoid compliance. Industry groups such as the

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 18

of personal data itself is wide-reaching, and legislation that keeps up with the ever-expanding term is crucial to meaningful consumer protection. There is also a category of “sensitive personal information,”8 including sexual, race, and gender identity, Social Security Number and password information, genetic and biometric data, online correspondence, and more. This data, in other words, is unique to the consumer’s identity, and is often deeply personal or private. The CCPA’s reintroduction of the consumer as an individual agent with tangible control over their data is crucial when the consumer’s identity is intertwined with the data. Indeed, understanding how consumer data is being used is an important first step for consumers to gain awareness and agency over their information. Consumers also have the right to delete their personal data. This provides a tangential pathway for consumers to directly hold companies accountable, building on the right to access. Consumers now also have the right to direct a business to stop its sale of their personal data. This is another avenue through which consumers can now exert direct control over the sale of their information. This clause treats data as functionally the property of the consumer, and thus something the consumer has agency in the sale of. This framework was not broadly applied to data sales prior to the CCPA, and has forced companies to adjust accordingly. There has been a growing movement among tech policy advocates for policy that treats data as the property9 of the consumer. Property

8 “Definition of Personal Data.”, DLA. 9 Gesser, Avi, and Michelle Adler. “Should Protection of Personal Data Be Regulated Using a Property Model, Rather Than a Privacy Model? Probably Not.” Program on Corporate Compliance and

rights, in the American legal context, have provided a more robust foundation for protections and accountability on the individual front as opposed to privacy rights.

Pivoting to a property-based approach to data protection better centers the consumer. The CCPA is the most recent policy that maps onto the property model the closest. The direct avenues of action it affords consumers effectively render data their property; they have the right to action over it. Ultimately, the CCPA has successfully redefined privacy rights in the Big Tech landscape, benefiting consumers by granting them meaningful control over the sale of their personal information. Several lawsuits applying the CCPA’s multiple facets make this evident. Barnes v. Hanna Andersson and Salesforce10 was born from a data breach that occurred on Salesforce’s Commerce Cloud platform, a platform meant to serve as a one-stop shop for business needs. Hanna Andersson, a children’s clothing store operating through Commerce Cloud, suffered the extraction of payment information and personal data when the platform was hacked. The plaintiff cited the CCPA’s requirement of businesses to maintain security over personal information and data being held as grounds for the case. The case became one of the first after the passing of the CCPA to apply its private right to action, where consumers can hold businesses accountable for their failure to “implement reasonable security measures.”11

Enforcement at NYU School of Law. Last modified 2019.

10 Bernadette Barnes v. Hanna Andersson, LLC. and Salesforce, LLC. (2020). https://www.classaction.org/media/ barnes-v-hanna-andersson-llc-et-al.pdf/.

11 Ridgway, William, Meg Grismer, Dana Holmstrand, John King, and Lisa Zivkov-

It proves to be a key way in which consumers now have broader and more concrete authority over their data. Another lawsuit proving the efficacy of the CCPA is that of Ajay Kirpekar v. Zoom Video Communications Inc. 12 The plaintiff noticed the rollover of their device and other data from Zoom to their social networking sites, such as Facebook, even though they had not yet created a Facebook account. It was argued that this was in violation of the CCPA’s private right to action clause, requiring businesses to maintain security measures, as well as consumers’ rights to stop the sale of their data to third parties. This lawsuit demonstrated that the CCPA provides sufficient legal grounds for consumers to protect themselves from similar data sales occurring without their consent, thereby imposing stricter regulations on business data practices and also granting consumers greater agency.

In the seven years since its passage, the CCPA has redefined the privacy rights and consumer protections landscape of California and the broader nation. It has provided consumers with direct means of advocating for themselves and has held corporations accountable in ways not previously possible. Its numerous applications, including those above, show its necessity and significance as we usher in an age of ever-expanding data collection and usage.

ic. “District Court Rulings Could Signal Expansion of California Consumer Privacy Right of Action.” Skadden. Last modified 2025.

12 Ajay Kirpekar v. Zoom Video Communications (2020). https://www.classaction.org/media/kirpekar-v-zoom-video-communications-inc.pdf/.

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 19

IAB initially claimed that certain data-sharing arrangements, especially for targeted advertising, did not constitute a “sale” under the CCPA if no monetary exchange occurred.3 Their compliance frameworks argued that passing personal data to third-party advertising partners could be categorized as mere “sharing,” exempting it from opt-out requirements.

In addition, to preserve behavioral tracking capabilities under the CCPA restrictions, tech giants like Facebook (Meta) and Google introduced features that contractually reclassified them as “service providers” rather than “businesses” selling data. In 2020, Facebook launched its Limited Data Use (LDU) setting, which limits how Facebook can use Pixel data, restricting it to services provided to the business client, not Facebook itself.4 Similarly, Google’s Restricted Data Processing (RDP) mode narrows its use of personal data to essential functions like ad delivery and fraud detection.5 These tools allow both companies and their partners to continue data collection practices without

3 Californians for Consumer Privacy, Comments on IAB’s Proposed CCPA Framework. https://www.caprivacy.org/ californians-for-consumer-privacy-comments-on-iabs-proposed-ccpa-framework/

4 Molla, Rani. “Facebook is gearing up for a battle with California’s new data privacy law.” Vox. December 17, 2019. https://www.vox.com/recode/2019/12/17/21024366/facebookccpa-pixel-web-tracker/.

5 Hunton Andrews Kurth LLP.

“Google Updates Privacy Terms.” https://www.hunton.com/privacy-and-information-security-law/ google-updates-privacy-terms-to-shiftaway-from-offering-some-services-as-aservice-provider-under-the-ccpa /.

offering opt-out mechanisms, preserving the core functionality of cross-site tracking. While technically compliant with CCPA, it could be argued that such measures weaken the law’s spirit by exploiting definitional loopholes and preserving the infrastructure of cross-site tracking.

Compounding these issues is the sluggish pace and symbolic quality of the CCPA’s current enforcement. The first significant enforcement action under the CCPA, a settlement involving Sephora, occurred two years after violations began. Sephora was fined $1.2 million for failing to disclose its data-selling practices and for ignoring opt-out signals such as the Global Privacy Control.6 While the settlement sent an important signal, the penalty was modest compared to fines under the GDPR and likely insufficient to deter larger companies in the U.S.7 The delay and limited scope of enforcement thus speak to CCPA’s weaknesses in systematic design and deterrence power.

Finally, emerging technologies, particularly generative artificial intelligence (AI), further challenge the CCPA’s efficacy in implementation. These models are trained on massive datasets scraped from the internet, often including sensitive personal data embedded in ways that cannot

6 Office of the Attorney General. “Attorney General Bonta Announces Settlement with Sephora.” August 24, 2022. https://oag.ca.gov/news/press-releases/ attorney-general-bonta-announces-settlement-sephora-part-ongoing-enforcement/.

7 Data Privacy Manager. “20 Biggest GDPR Fines So Far [2025].” https:// dataprivacymanager.net/5-biggest-gdprfines-so-far-2020/.

be easily removed.8 In 2023, a class-action lawsuit, Doe v. GitHub, was filed against GitHub, Microsoft, and OpenAI. The plaintiffs alleged that the companies used copyrighted content without consent to train AI tools like Copilot and Codex.9 Although the current primary claims on it concern intellectual property, the case also raises serious questions about the limits of data control and deletion rights under the CCPA. Once personal data is absorbed into an AI model, it becomes nearly impossible to trace or erase, which directly undermines the rights of deletion and transparency governed by CCPA.

Certainly, the CCPA represents a critical milestone in U.S. data privacy regulation. Its ability to deliver on that promise, however, remains constrained by persistent issues—including low consumer engagement, corporate exploitation of legal loopholes, insufficient enforcement, and the massive yet irreversible AI training phases. Whether the law can rise to meet these challenges remains uncertain, but with continued reform efforts and growing public awareness, there is still hope CCPA will grow into the meaningful safeguard it was originally intended to be.

8 “OpenAI Accused of Privacy Breaches in Massive Lawsuit.” https://promptengineering.org/openai-accused-of-privacy-breaches-in-massive-lawsuit-2/. 9 Doe v. GitHub, Inc., Case No. 22-cv06823-JST, United States District Court, N.D. California. https://cases.justia.com/ federal/district-courts/california/candce/4:2022cv06823/403220/195/0. pdf?ts=1706027438/.

by SARA MUNSHI STAFF WRITER

“Disgust is not a valid basis for restricting expression.”

These words from Justice Scalia, in Brown v. Entertainment Merchants Ass’n,1 reverberate today as the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) reviews Free Speech Coalition Inc. v. Paxton. This case navigates the boundaries of free speech, privacy, and state power in a digital age. The point of contention in this case is Texas House Bill 1181 (H.B. 1181), a statute requiring websites with “sexual material harmful to minors” to verify user ages before granting access.2 At face value, the law frames itself as one of safeguarding and righteous intent regarding the protection of children. Yet, both logic and precedent show the law’s overreach. It is wanton in its disregard of adult expression, use of surveillance, and it attempts to rewrite decades of First Amendment jurisprudence. H.B. 1181 is an unconstitutional regulation cloaked in paternalism.

Let us first begin with the contested notion of obscenity and what it entails. Obscenity is defined as offensive material, as evaluated by federal and state courts using a three-part test (est. Miller v. California). To fail the test elicits a lack of protection under the First Amendment. The criteria

1 Justia Law. (2025). Brown, et al. v. Entertainment Merchants Assn. et al., 564 U.S. 786 (2011). https://supreme.justia. com/cases/federal/us/564/786/.

2 Golde, K. (2024). Free Speech Coalition, Inc. v. Paxton. SCOTUSblog. https:// www.scotusblog.com/cases/case-files/ free-speech-coalition-inc-v-paxton/.