EARTHQUAKE

EARTHQUAKE

Written by Rian Paul

弟弟

Growing up is something every person experiences, and we develop the most as humans during our teenage years; from puberty, to school, to relationships. This is where the Coming-of-Age film comes in, a genre which can create a huge emotive response from viewers, as it depicts the good, bad, awkward, and embarrassing moments of growing up. Sean Wang’s film Didi (2024) hits all these notes. Following Chris, a young Taiwanese American Boy, and his summer before starting high school, where he clashes with his friends, talks to his crush, and develops his relationship with his family. This analysis of Didi looks at what makes this film so engaging to audiences of a certain generation and upbringing, and the storytelling techniques used. Nostalgia has never been more present in film as it is today, with Meta Modernism becoming the new movement amongst major studios, with geriatric sequels and remakes ruling the box office over the last few years. Didi however, focuses on a much simpler form of nostalgia. Wang could have easily decided to set this film in the modern day, however this film needs to take place in 2008, as the technology and social landscape of the time are

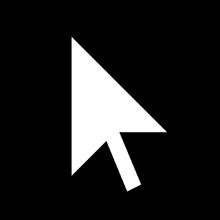

integral to the story and the choices characters make. Looking at social media platforms present in the film like MySpace and Facebook, Chris learns many things about his crush via her profiles, with her favourite movies and songs posted, leading to Chris pretending to like the same romantic films as Madi.A scene like this would not be possible if the film took place in the modern day, as social media profiles and users are more private about their life. The attitude around technology is also important here, as Chris’ use of his camcorder adds a further layer of nostalgia to the scenes he films with it, like the skateboarding or the opening scene. Wang could have decided to film these scenes with professional cameras, but by deciding to film the POV of Chris’ camcorder the audience are able to view his interests and activities through the specific mid-2000s lens; relating it to the viewer’s own experience with the rise of technology.On a similar note, the use of the computer screen throughout the film is both an impressive choice in cinematography and a way of portraying the character of Chris. Multiple scenes in the film feature Chris using his computer, but instead of filming the screen from a distance, Wang decides to use the screen recording of what Chris is doing, so during these scenes we only see the cursor and what is on screen. What impresses about this choice, is how the cursor portrays the character of Chris. Everything from the speed the cursor moves at, with slower movements communicating hesitation, to the amount of time spent between clicks and movements of the cursor, to communicate he is reading something or reacting emotionally, like when he decides to block his friends. The user interface of the computer also aids the depiction of his character, as we can see the multiple tabs Chris has open, further presenting him as a 2000s kid who is ‘chronically online’. Not always seeing Chris’ face in some of the more emotional scenes like the blocking scene can generate a more reactive response from the audience, as the audience need to engage and focus on what they can see to understand how Chris is feeling. It should be noted that Wang still does implement some reaction shots of Chris during these scenes (possibly to ensure that the audience are being communicated the right message of Chris’ emotive responses). It can be argued that the narrative of Didi does not give Chris just one point of contention, from trying to speak to his crush, to his falling out with Fahad, to befriending some older skaters, to his relationships with his sister, grandmother, and mother. What is impressive with the multiple focuses is Wang’s ability to juggle each of these simultaneously instead of formatting the narrative episodically, with a scene focusing on Chris’ new skateboarding friends becoming a scene about his relationship with his mother. Wang takes this further however, by creating this environment within the narrative where each of these focuses directly/ indirectly affects each other. An example of this is when Chris first goes to hang out with his older friends, his sister offers to drive him there because their mother and grandmother are arguing. Within one scene, Wang has

progressed multiple different plot points, by developing the relationship between Chris and his sister, showing the first time he is going to hang out with his new friends, and the strain of Chris’ father working overseas has put on his mother and grandmother’s relationship, which by listening too, Chris is able to further respect his mother (a point which will be revisited). There is nothing wrong with telling these smaller narratives episodically, however, the choice to interlink this narrative through cause and effect allows the audience to feel overwhelmed; relating to how Chris, and many at that age, felt, trying to navigate all these new things in his life.An important thing Didi does is normalise the way Chris feels and acts throughout the film. Many viewers could see Chris as a mirror to themselves when they were his age, and feelings of embarrassment or sensitivity are natural to experience. Wang utilises this to present a deeper message to the viewers; that by making them watch the way Chris acts throughout the film; being communicated to by a filmmaker who went through the exact same thing, Chris’ (and by extension the audiences’) struggle is justified. Didi does not ask the questions of if the actions of Chris are over exaggerated or if his interpretations are correct, even though many can look back at their past selves at this age and find moments when it was. Instead Didi focuses as much effort as possible in placing the viewer in the perspective of Chris, reflecting on their childhood. Like the scene where Fahad tells Chris to take a bus to join them whilst they all travel by car, here the camera zooms in and focuses on the POV of Chris; looking into the car and seeing his friends enjoying themselves and not appearing concerned for him. Through this, Wang is not asking the question of if Chris has a right to be upset by this, instead he presents why Chris is upset and allows the audience to relate that to their own experience by facing the sadness, isolation, and embarrassment a moment like this feels. The final aspect of Didi to be analysed is the development of the relationship between Chris and his mother. One of the themes within the film is the appreciation one should have for their mother and many viewers can relate to the development in the relationship they have with the people that raised them as they

become older. The relationship between these two characters is built through scenes where their can empathise and understand what the other is going through. But these scenes must be balanced with ones where they clash, to present the idea of progression within their relationship. Scenes like the dinner table argument between Chris and his sister where the mother is unsuccessful in deescalating the situation, to the emotional argument in the car which ends in Chris running away. These scenes depict the need for this mother and son relationship to develop, as Chris getting older is clearly clashing with Chungsing’s struggle of raising him on her own now. Because Wang allows time for us to see the struggle Chunsing is going through, he again does not ask the question of who is right during the argument scene, instead he presents a scene which, thanks to context, the audience can empathise with both and, instead of one being right, simply want them to understand each other. This understanding feels earned through scenes like the argument scene between Chungsing and the grandmother, where they argue about Chungsing’s parenting and Nai Nai argues that her son (Chris’ father) is the only one supporting the family. During this argument Chris is listening from another room, and through his facial expressions and body language, is it clear that hearing this is upsetting. A scene like this is necessary as this argument is unaffected by Chris or Vivian’s presence, which therefore means the audience (and Chris) can hear this argument authentically.

This therefore leads to the scene of understanding, as Chris spends the night wandering the streets and waking up in a park, he melancholily returns home to his mother sitting in bed, he enters and asks his mum why she did not go out and look for him. She tells this story about how Vivian did the same at his age and through that experience she learned that her children would come back to her and that she needs to give them the space to do so. What follows is a heartfelt conversation about how Chungsing has picked her children over her own desires as an artist, and how she will always be proud of Chris. This scene serves as the moment of understanding between these two characters, as Chungsing realises she must give her children space, and Chris can view his mother as an independent woman, an important thing for everyone to realise.

What director Sean Wang has been able to do is something so easily taken for granted with films which are able to connect with audiences on a deeper level. However, through this analysis of what elements of Didi make it such a great coming of age film, as well as why Wang decides on certain creative choices, helps us appreciate the effort it takes to generate a response like this from the audiences and the true thought and creative decision making necessary for a coming of age film to truly work.

“If only it could be like this always”

The tragic beauty of nostalgia in Brideshead Revisited.

Written by Hob

1981’s Brideshead Revisited is, for me, the apotheosis of nostalgic television. Even as the first episode begins - in classic 5:4 ratio - we are greeted with slow, simple opening credits accompanied by Geoffrey Burgeon’s wistful and bittersweet theme, slowly followed by slightly grainy, warmly lit cinematography. A time capsule in and of itself, the series is truly a throwback to the days of slow television; the sort of thing you stumble upon your Nan watching but become slightly transfixed with. Each hour-long episode takes its time to pan over beautiful English countryside, or have quiet, awkward conversations over a lavish dinner. Although set between the 1920s and 1940s, these long, laidback scenes and old-fashioned visuals have a remarkable 1980s feel, creating an atmosphere not unlike Maurice (1987) or Dead Poet’s Society (1989).

The series follows the recollections of WW2 Captain Charles Ryder, as a surprise re-encounter with Brideshead Castle - a stately home, important in his past, now commissioned by the army - prompts him to reflect on 20 years of history surrounding the house and the family who resided in it. Told through a series of memories, both fond and dark, the soul of Brideshead Revisited itself is nostalgia, with ‘present’ Charles providing voiceovers on how much he misses the past, as ‘past’ Charles, on the screen, is blissfully unaware that anything will change.

The theme of nostalgia continues within the memories themselves throughout, but first, and most prevalently, through the character of Sebastian. Sebastian is one of the middle children of the Flyte family, and the first of the family whom Charles befriends. The two meet at Oxford in 1920, Charles becoming enamoured with Sebastian’s eccentricity and ardour. Sebastian is a tragic character, who is plagued by his strained ties with his family and longing to be dissociated from them, as well as his struggle with his sense of self and belonging, his underlying sadness, and his penchant for alcohol to help cope with these feelings. However, among this lies perhaps the most charming aspect of Sebastian’s character - his childlike nature and innocence. Unable to deal with the responsibilities of upholding image and the expectations and judgements of his family, Sebastian escapes into childhood. He is especially attached to his teddy bear, Aloysius, who he brings everywhere with him and speaks on behalf of. Alongside his bear, Sebastian treasures his childhood nanny, Nanny Hawkins. Despite his initial impression of charm and playful innocence, Sebastian grows to represent an unhealthy obsession with nostalgia, using it as a mechanism of escape rather than source of joy.

The point at which his teddy and his nanny no longer provide enough comfort to soothe his anguish signals the beginning of the end for Sebastian - he simply cannot function in the present, as an adult, spiralling further into addiction and isolation. As Sebastian’s father’s mistress, Cara, confides to Charles earlier on, “Sebastian is in love with his own childhood. That will make him very unhappy.”

During the second episode, in 1920, Charles and Sebastian, joined occasionally by Sebastian’s sister Julia, spend a summer alone at Brideshead Castle, later travelling to Venice to see Sebastian’s father. The delicate beauty of the summer is perfectly shown through the cinematography; the golden haze of afternoon sunlight as the pair sunbathe by the fountain; the sultry purples and blues of the hazy nights in Venice. Charles and Sebastian spend the summer spending too much, drinking too much, and growing too close to each other; for just this moment they are allowed to be young, alone, and carefree.

‘Sebastian’s Summer’ (as it is named in the soundtrack) is the beating heart of the story and almost becomes representative of nostalgia itself as the series goes on. The central characters

spend the rest of the series constantly looking back, trying to mold his life into a recreation of the happiness they felt in that summer. This is how the story reveals itself as a tragedy; nothing the characters can do will ever retain the beauty and innocence of those days - they only exist in the past. Sebastian remarks, at this time, “If it could only be like this always” - the sadness sneaks in even here; even here we know this moment is not going to last.. At one point, Charles and Julia reach a point not too far removed from that first summer - the pair spend warm days at Brideshead alone, and whilst older, and with more worries, the characters manage to reach a level of contentment that we haven’t seen in them for a while. We see visual homages to the second episode - the return of the golden light; Charles and Julia by the fountain - a reflected image of Charles and Sebastian a few episodes earlier. It is through these visuals that we can share in the characters nostalgia, subconsciously connecting to the time period which has been sought after for so long. This time is different however - the characters are on edge. They know full well that this period of sanctity is impermanent, almost as if they are aware that their story is a tragic one. When the facade does drop, with Julia breaking down after a party and subsequently calling off the pair’s engagement, the visuals return to colder colours; the summer returns to being accessible only through memory. We, just like the characters, find ourselves yet again longing for the return of the summertime visuals and peace that they bring the characters we have grown to love and pity - but on this occasion, it will not return. The remainder of the show is, although still beautiful, largely coloured with greys and blues, the weather becoming colder, the costumes less colourful. Despite the somber tone this creates, it is not entirely miserable - the characters carry this first summer with them all the way, and echoes of it constantly sparkle through dialogue and cinematography. Even if it is only through longing, the beauty of the past radiates through the screen, even at the darkest moments. It is this beauty, the love these characters have for these memories, despite the grief that accompanies them, which is such a perfect portrayal of nostalgia - isn’t it sad to miss something we can no longer have - but wasn’t it beautiful that we got to have it?

By Bel Mellor

There’s someone else in the mirror, Someone shorter and quieter, Someone with baby hairs and wobbly teeth,

Away with the fairies, Somewhere in Neverland I lost her. I see her in in flickers of light dancing across the pond, And in notebooks saved, just in case.

I hear her in my laugh, And she sits with me when the sting of saltwater hits my nose, Floating along like seafoam grasping for each other.

She perches on my shoulder, As though a robin hiding from the cold,

I keep her safe.

Spring will come soon, and she will be gone.

A single feather floats into my palm, I tuck it into my jacket, Safe from the frost.

Gone from the nest, I’m left with her memories and softness. I’ll protect her kindness and keep her with me.

When I was a young teenager, the thought of outwardly expressing love for my favourite childhood films would make me cringe with embarrassment. I couldn’t imagine being able to admit I still loved them-I was terrified of being labelled “childish”, or even later on as an older teenager, being seen as having inadequate taste. It’s only now as an adult, that I’ve come to realise how important these movies were in shaping the person I am today, and how fulfilling it is to revisit them. I remember watching Hannah Montana: The Movie (2009) for the first time and being obsessed with learning all the steps to the complicated dance routine that accompanied Hoedown Throwdown (which frankly, I still have never gotten), rewinding over the extensive and glamorous makeover scene in Monte Carlo (2011) just to examine the vanity cases filled with make-up,

dresses and jewellery, or watching Aquamarine (2006) and wishing the titular mermaid-Aquamarine’s talking starfish earring studs were real.

Now, at the oldest I’ve been in my life, I find myself more and more wanting to reconnect with my younger self. Just recently I replaced my wallet with a Scooby Doo one, got a Moomin water bottle, and bought the complete series of Emily the Strange comics-all things I remember loving from my childhood. These past two years have seen a resurgence in people buying Sylvanian Families blind bags, and Sanrio figurines. So, what is this reversion to our younger selves? Could it be caused by the fear and uncertainty towards the growing instability within the world? A coping mechanism to deal with the many stressors of “adult” life? I know for me; it is

certainly for these reasons- The past provides comfort. Because, above all, you know how it happens. The present is unstable, constantly in flux, and the future is uncertain. As well though, I am simply able to reunite with every past version of myself again; and to do away with the idea of being “cringey” and feeling ashamed for enjoying the things I

More and more online we are seeing the death of individuality. People are dividing themselves into “Aesthetics”, thinking they’re “not allowed” to dress, listen to music, or express any interest in another style. But uniqueness is what makes us human! Originality is important. It’s what allows us to connect with each other- on a deeper level than just

In the words of Youtuber “the zurkie show”- you need to nerd out. At 21, I have never felt freer to

express my interests; to be excited about my love for the High School Musical movies, or even something so small- like comfortably wearing Hello Kitty shirts. “Nerd” is always used as an insult- but to be passionate, knowledgeable and to love something without any care to what people think, is inherently cooler than suppressing it.

By Katie Hall

Of all the long-running themes within Woody Allen’s extensive filmography, nostalgia might be the most fascinating. Allen certainly hasn’t been a stranger to this theme in various forms, whether through nostalgically soaked characters or expressing his own love for a bygone era of filmmaking and artistry. His early films often either allude to, or are entirely about, nostalgia. Manhattan (1979) begins with Allen’s character Isaac harking back to a better time in Manhattan’s history, talking about the “decay of contemporary culture”. Radio Days (1987), a film I regrettably haven’t seen yet, is explicitly about harking back to a golden age of radio during the 1930s. Shadows and Fog (1991) is a homage to the German expressionist cinematic movement of the early 20th century. Deconstructing Harry (1997) is full of literary and artistic references, as are most of Allen’s films, arguably signalling Allen’s genuine appreciation for older artists and artistic history. I could go on, but it’s his 2011 feature Midnight in Paris that I’m most interested in. The film stars Owen Wilson as Hollywood writer Gil, a man obsessed with becoming a novelist in Paris. He takes a trip to Paris with his fiancé Inez, before it takes a magical turn and Gil meets his favourite authors and artists from his favourite period, the 1920s, in the dead of night. Nostalgia is perhaps the most prominent theme of the film. Gil as a character is infatuated with the Paris of the 1920s, often remarking upon it to Inez, often to her dismay. He’s even in the process of writing a book set in the period. The wrestling of the merits of nostalgia is perhaps the central conflict of the film. Whilst Gil praises the period and is often genuinely wishing he lived in that time, Inez consistently disregards his longing. Her academic friend Paul also decries Gil’s nostalgia, calling it a denial of a “painful present” as the trio take a stroll through the city. Gil’s prayers are eventually answered when he meets the Fitzgerald’s, followed by Ernest Hemingway and other icons of the Lost Generation. After having met them and falling in love with Marion Cotillard’s Adriana, he eventually concludes that his nostalgia is a dead-end. His love for the period is never-ending, but Adriana believes the period before the 20s was greater. By the end of the film though, Gil’s love of the city and the period isn’t really condemned, more sidelined. As he begins to realise that his present is in fact his present, he arguably doesn’t forget his love for the period, he instead only sidelines it. Of course, Woody Allen is no stranger to introspection and nostalgia. His work is full of references to older filmmakers and artists, the most famous example being Ingmar Bergman.

In some sense, lots more of his recent work is soaked in nostalgia too. His 2005 offering, Match Point, is full of grand and nostalgic posturing. The perfectly manicured and peaceful tennis club, the grand aristocratic looking countryside mansion and the quaint apartments all serve to give a very particular view of English life and almost present a thematic tension between the established aristocracy of the past and the new money Thames apartment ideals of the new millennium. Allen’s work is connected to the past in a never-ending way. As I say, many of his literary references go back to the early 20th century and imply a fascination with the customs and traditions of the past, especially artistically so. In this regard, it’s interesting to think about how Allen feels about art in the context of the past. One thinks of the scene in Manhattan where his character Isaac, a TV writer, watches an episode of his show and berates it as anti-intellectual and too appealing to the masses. Since that film quite close to Allen’s early writing career, at least in how his job is portrayed in the film, this opens up questions about how Allen views art of the present versus the past. One gets the feeling that through his work, he frequently harkens back to a cultural landscape bereft of reality TV and full of interesting plays and novels instead. His idealisation of the writer, having been featured as a character archetype frequently in his films, is a key part of this. Having a cultural landscape whereby writers are idealised and celebrated, as they pontificate on philosophical issues as if they belong to the same meta-physical tradition as the great thinkers of history, is clearly important to Allen as a filmmaker. Just as Owen Wilson’s character in Midnight in Paris constantly belittles his Hollywood writing, and praises what he calls “real” literature, Allen’s character in Manhattan seems to believe the same notion, that high-brow literature should always be taken more seriously that popular television. It seems to me that through his characters,

Allen often harkens back to a somewhat imagined reality of the art-scene. An artistic culture bereft of easy jokes and full of sophistication is clearly what permeates much of Allen’s work, however realistic this vision actually was. There’s a magnificent scene in Celebrity (1998) where Kenneth Branagh’s character, a writer, is partially trying to pitch his new book to fellow writers in a house party. The essence of the scene may be the dialogue and conversation, but the real accessories of the scene are what make it come to life. The bookshelves, wine glasses and blazers help to exemplify the overall culture the characters are a part of. This romanticism of art and writing culture is, arguably, almost always connected to a kind of amalgamation of past and present in Allen’s films. Both the aforementioned Midnight in Paris examples and more recent films, like Café Society (2016) and A Rainy Day in New York (2019) support this notion that Allen is somewhat obsessed with a very specific vision of artistic culture. Even though one could argue that this vision is usually separate from reality, I wouldn’t say this hinders the result on screen. Allen’s scope is narrow, but his boundaries within this scope are wide and for this I commend him.

The places you knew never existed

Jack Froggatt-Cooper

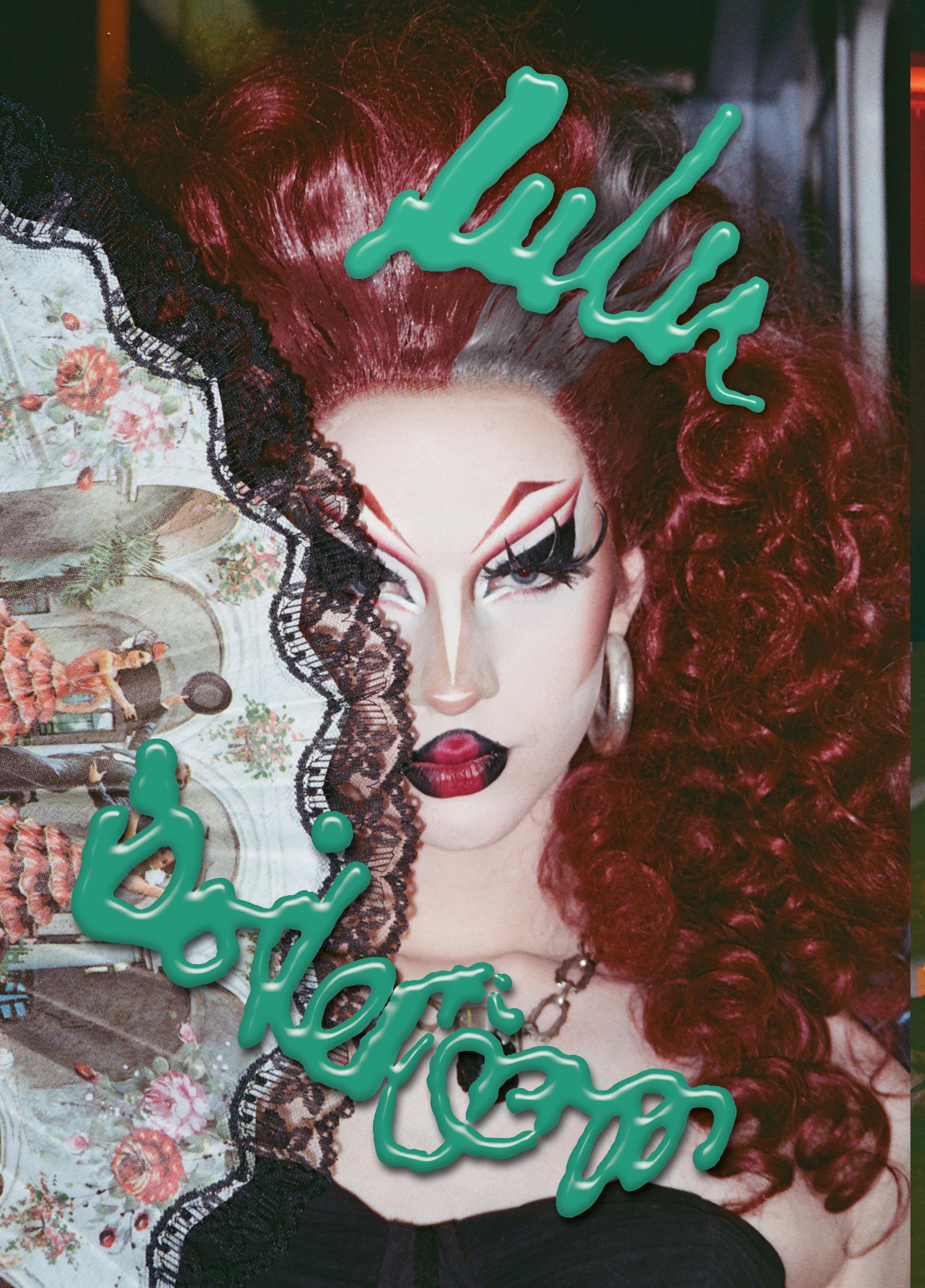

3-4 Lulu at Boileroom

Photography AVA CHILLINGWORTH

@avasanalog

Design AVA CHILLINGWORTH

Muse LILY KEFFORD @ewthatslulu

5-6 In the UK in 2010

Text FAITH WILLIAMS

Design FAITH WILLIAMS

Photography Bling Ring (2013)

7-12 DiDi: constructing the nostalgic coming of age film

Text RIAN PAUL @rian.paul_filmmaking

Design MARIAM AHOUESSOU @pozi.de

Photography DiDi (2024)

13-14

Nostalgia... Bulgaria Style

Photography AVIVA GENEVA @avgen.art

Design AVIVA GENEVA

15-16 The tragic beauty of nostalgia in Brideshead Revisited

Text Hob

Design MARIAM AHOUESSOU @pozi.de

Photography Brideshead Revisited (1981)

17-24 Who’s hiding in my reflection?

Photography BEL MELLOR

@belfilmsthings

Text BEL MELLOR

Design FAITH WILLIAMS @woodlousedude

25-26 Nerd Out

Text KATIE HALL @kat4evaaa

Design ELLA STEVENSON @ellas_art_design

27-28 remember

Illustration ALANA BAILEY @alanabea.art13

29-30 NOSTALGIA IN PARIS: The Longing of Midnight in Paris‘The Dazed Minded’

Text MILES FARROW @milesssfarrow2

Images Midnight in Paris (2011) Dir. Woody Allen

Design MADALYN WARDLE

31-44 The places you knew never existed

Images Jack Froggatt-Cooper

Design AVIVA GENEVA

45-46

Student Spotlight 03

Images Movie Star Planet (2025)

Design Faith Williams

47-48 Credits