THE UBYSSEY

EDITORIAL

Editor-in-Chief

Aisha Chaudhry eic@ubyssey.ca

Managing Editor Saumya Kamra managing@ubyssey.ca

News Editor Stephen Kosar news@ubyssey.ca

Arts & Culture Editor Julian Coyle Forst culture@ubyssey.ca

Features Editor Elena Massing features@ubyssey.ca

Deputy Managing & Opinion

Editor Spencer Izen deputymanaging@ubyssey.ca opinion@ubyssey.ca

Humour Editor Kyla Flynn humour@ubyssey.ca

Sports & Recreation Editor Caleb Peterson sports@ubyssey.ca

Research Editor Elita Menezes research@ubyssey.ca

Illustration & Print Editor

Ayla Cilliers illustration@ubyssey.ca

LAND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Photo Editor Sidney Shaw photo@ubyssey.ca

Digital Editor Sam Low samuellow@ubyssey.ca

BUSINESS

Business Manager Scott Atkinson business@ubyssey.ca

Account Manager Ben Keon advertising@ubyssey.ca

President Ferdinand Rother president@ubyssey.ca

CONTACT

Editorial Office: NEST 2208 604.283.2023

Business Office: NEST 2209 604.283.2024

6133 University Blvd. Vancouver, BC V6T 1Z1

Website: ubyssey.ca

Bluesky: @ubyssey.ca

Instagram: @ubyssey.ca

TikTok: @theubyssey LinkedIn: @ubyssey

The Ubyssey acknowledges we operate on the traditional, ancestral and stolen territories of the Coast Salish peoples including the xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam), Sḵwx̱wú7mesh Úxwumixw (Squamish) and səlilwətaɬ (Tsleil-Waututh) nations.

As I write this, my phone’s average screen time sits at 29 minutes per day — low compared to many of my friends. But if I were to add up the hours I spend across all my screens — phone, tablet, computer, TV — a pattern quickly emerges: I spend more waking hours a day on the screen than not.

Screens are everywhere I go: classrooms, restaurants, buses, libraries, washrooms, offices. For many students, screens are unavoidable as they are demanded by coursework, are a form of socialization, provide entertainment and offer navigation.

This year, The Ubyssey’s photo issue explored the presence of screens in our lives. In the first piece, Navya Chadha spoke to a game developer about the line between reality and virtual worlds. In the next piece, Zoe Wagner examined the use of technology in classrooms by interviewing Sauder instructors about their laptop “lids down” policy. In the article “the annotated screen,” myself and Ilia Rezaei Rad interviewed three UBC filmmakers about their use of the screen to convey meaning through cinematic techniques. Finally, in the photo series “behind the glow,” photographers created surreal images examining the glow that screens cast on our lives without confronting them directly.

Whether you love, hate, or resign yourself to screens, we hope this issue helps you reflect on your relationship with them.

We also hope that you are reading this in print.

Sidney Shaw Photo Editor

Words

In late November, in a quiet corner of campus, I spoke with team lead Kimiko Ngo from UBC Game Development. She is used to talking about games: how they’re built, how people use them, how they shape the worlds we escape into. But this conversation isn’t about code or mechanics — it’s about something more subtle. It’s about what it means to feel connected in a world where

digital realities fold so easily into the real one.

In his 1974 book, Anarchy, State and Utopia, philosopher Robert Nozick famously imagines an “experience machine,” a perfectly simulated world where nothing goes wrong and everything you want — friendship, romance, success — is guaranteed. Plug in, and you would never know it wasn’t

real. But most people, he argued, would refuse. We value more than pleasure; we value authenticity, struggle and freedom.

So the question becomes: in modern digital life — especially gaming, where connections can feel vivid — and worlds can feel immersive, how close are we to Nozick’s imagined machine? And how do people like Ngo navigate that threshold?

When asked whether relationships in games feel real — friendships, rivalries or even romance — Ngo thought carefully before answering. Her eyes flicked upward as if searching the ceiling for the right words.

“To a certain extent, they are real,” she said. “But not in the same sense.”

She split the question into two. In games with predetermined narratives, such as visual novels and story-driven role-playing games, the relationships are written in advance. They aren’t real people, but the emotions can be. Players get attached to characters, not because they believe those characters exist, but because the game explores personalities, fears, loyalties and vulnerabilities in ways that resonate.

“The emotions that they trigger do feel real,” she said. “Because it could be exploring certain personalities or certain events.”

Multiplayer games, though, are different. There, behind every avatar, is a human being.

“The experiences you share with people online are real because those are real humans on the other side,” she explained. People build guilds, teams and rivalries. Relationships are formed through hours of shared effort, failure, jokes typed into late-night chat windows and synchronized

attacks against impossible bosses. For many, these communities feel as substantial as anything offline.

Yet, she added, the line between the two kinds of relationships, online and in-person, is not the same for everyone. Ngo herself is someone who feels more grounded in faceto-face connections. “Most of my relationships are in-person,” she said. “But I can see another perspective, where someone else would [feel] there’s no difference.”

She keeps things grounded, careful not to romanticize the digital, but not to dismiss it either.

Ngo explained that some people can be more susceptible to this blurring of boundaries.

It’s not addiction she’s critiquing, it’s dependency. If someone’s best or only sources of support live in fictional worlds, or if their closest sense of belonging comes from behind a screen, the line between game and life can thin. There’s comfort in consistency. There’s comfort in a world that never rejects you unless the script demands it.

That’s where Nozick becomes disturbingly relevant. The philosopher argued that what we want is not a perfect experience, but a real one, shaped by uncertainty, failure and the possibility of change. A virtual world designed solely for pleasure removes all of that.

But modern digital spaces don’t need to be perfect to function like the experience machine. They only need to be preferable.

Ngo sees that. She doesn’t condemn it. She names it for what it is: human vulnerability expressed through technology.

When asked if long gaming sessions make her feel more or less connected to real life, Ngo laughed.

“I definitely feel more disconnected from life after a long gaming session,” she answered. “Because I think I have to be fully immersed into the game when I’m playing it. Especially if it’s a long session, then that means I’ve been engaging with this world more than real life.”

She described it casually, but the phenomenon is familiar to anyone who has played a game so absorbing that the real world feels flat when you return to it. The transition is jarring, the lighting is different, your body feels heavier, sounds seem wrong and time seems off. Reality feels ill-fitting until the mind re-centres itself.

It’s a reminder that immersion isn’t passive — it’s a temporary relocation of consciousness.

And for some, coming back isn’t as simple.

Toward the end of the interview, Ngo was presented with the question that animates Nozick’s entire argument:

Would you trade your real social life for a perfect simulated one, if you couldn’t tell the

difference?

“No,” she said. “Even if I couldn’t tell the difference.” She leaned forward slightly.

“Especially if it’s perfect, then I think it gets boring, like you run into a stalemate where there’s no challenge. There’s nothing that will change.”

That, she argued, is the fundamental flaw of simulated perfection. Real relationships are messy, inconvenient and surprising; they force you to expand. They hurt you, they test your boundaries and they reflect versions of yourself you might not want to see. Fictional ones, or artificially-tailored ones, can’t do that. They can only mimic struggle, not generate it.

“Real friendships teach you more about the world,” she said. “They push you to grow.”

This cuts to the heart of Nozick’s point. It’s not just that people prefer reality, people prefer risk. Freedom is not satisfying if everything is predetermined, even in your favour. Growth requires friction. A life without obstacles becomes hollow.

And yet, Ngo’s certainty is not universal.

There are people for whom the real world feels harsher, less forgiving, less rewarding than its virtual counterparts. She acknowledged that too. The world is not equally kind to everyone, and for some, the screen becomes a sanctuary rather than an escape.

As the interview wound down, she reflected on the people who might not feel the disconnection she experiences after gaming — those who step deeper into fictional or virtual communities because they feel more welcome there than in the physical world.

For them, she said, “that line between connection and simulation doesn’t disconnect.”

It’s not judgment, but recognition.

And that’s where the conversation settled: on the blurry threshold between two realities that increasingly overlap. Nozick imagined a machine that people would reject. But the world we have built — games, online communities, digital identities — suggests a different picture. Most people aren’t plugging into a machine; they’re drifting into something softer, more ambiguous, more porous.

A world not fully simulated. Not fully real. Something in between.

Ngo doesn’t fear that world. She simply navigates it with intention, with an understanding that screens can enrich life, but not replace it. Emotions felt in fictional spaces are real, but not always reliable and growth requires the risk that a simulated world refuses to give.

As the blue light dimmed and the camera lowered, the room felt more grounded again. The interview ended. The real world resumed — imperfect, unpredictable and, in its own way, worth choosing. U

Classroom rules have existed since we were in kindergarten. Maybe you needed to wear a uniform. Sometimes you couldn’t wear a hat in class. During high school, you might’ve had to hang your phone in a little pouch on the wall.

UBC policies are continuing to adapt to the digital age — computers, iPads and other technology, however, are unavoidable. Class resources, assignment submissions and exams all take place on Canvas, so how could anyone avoid it? At UBC’s Sauder School of Business, some undergraduate and graduate classrooms have a

‘lids down’ policy.

The policy is the default in most Sauder graduate classes, meaning students are not allowed to use electronic devices during class unless permitted by teaching staff. Instructors outline the specific requirements for their individual classes. Every use of technology should be for educational purposes.

Dr. Greg Werker, the senior associate dean of student experience at Sauder, explained how the lids down policy took shape in the Robert H. Lee Graduate School a few years ago.

“What they found was that

it made for a better feel in the classroom … more participation, more engagement in general, better class discussion,” said Werker. Nowadays, the graduate school has a lids down default for all classes, allowing professors to change their policies according to class-based needs.

“I know in my classes there’s often technology being used for an in-class activity,” Werker said. “Then it gets hard to say, ‘Okay, lids down, now lids up, now lids down.’”

There is currently interest from Sauder faculty, all the way up to the dean, to look into making this

a policy for undergraduate classes, some of which already discourage screens. COMM 101, an iconic first-year business fundamentals class, only allows paper or iPads for notetaking purposes, and laptops can only be used for in-class activities.

Dr. Zorana Svedic, former COMM 101 course lecturer, said that “because many people in high school are so used to using technology, when they come to university they expect they’re going to continue doing the same thing. But then, when we come to them with these policies, some people love it, some people hate it.”

Svedic acknowledges laptops can be a distraction. “Your eyes will automatically be looking [at] anything that moves — otherwise we would’ve been eaten by dinosaurs a long time ago.”

Svedic even brought back scratch-scantrons (multiple choice sheets where you scratch off a silver coating to select an answer) for her project management class, a testament to how the ‘best’ technology isn’t always necessary for learning.

Barbara Cox teaches commercial law, COMM 393, and is one of the few undergraduate professors that goes completely lids down in class. iPads are not available for notetaking, and laptops are only brought out when explicitly instructed.

Seth Feldhuhn, a current COMM 393 student, was “originally very against [the class policy]. I was like, ‘just let us go on them, we are in college.’” But upon reflecting on his own laptop use in other classes, he found that the lids down policy has helped him stay focused.

Anything that’s not class content can be distracting, from social media, to emails and even Slack messages — the world is at our fingertips at all times.

Some studies find “people do a better job remembering things

when they write things down using handwriting,” Werker said. Additionally, the distraction of seeing someone else’s screen can be equally detrimental.

“It’s like a secondhand smoke effect,” Werker said. “It does impact those around you. So it’s not that we’re just saying ‘put your own lid down because you’ll learn better.’ We’re saying ‘put your lid down because it’s distracting to those around you.’”

There is an element of convenience in notetaking on laptops. Notes are easier to go back and read through when you don’t have to decipher the chicken-scratch you wrote on the fly to keep up with your professor’s talking and textheavy slides. Finding a balance between engagement and letting students learn in the way that works best for them is the million-dollar puzzle.

Werker points out, “I’m a huge fan of technology, and at the same time, it is not always the right answer.”

When Werker holds activities on paper in class, he has learned to bring extra pens because many students don’t carry them around anymore. While change isn’t always good, professors need to remember to meet students in their reality. U

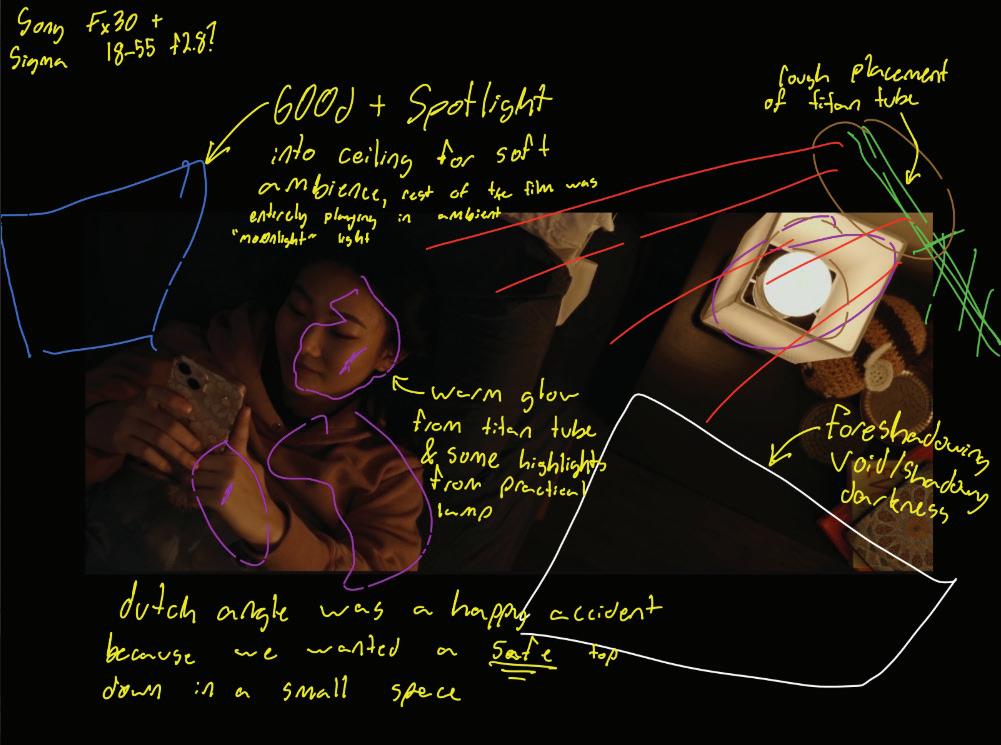

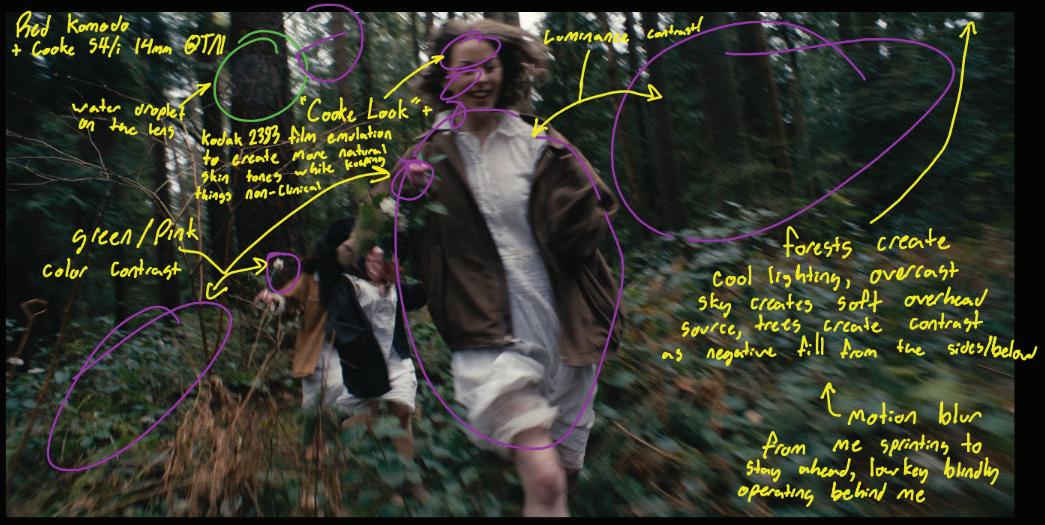

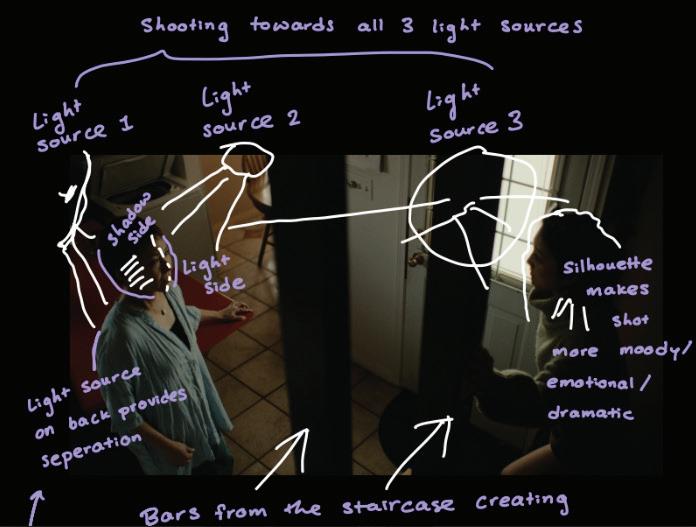

How do artists use the screen to convey meaning and emotion? We interviewed three UBC filmmakers about their approach.

For each filmmaker, you will find three parts: a section explaining their experience in the field and their relationship to the medium. Then, we asked them to annotate stills from their work to illustrate the process behind each one. Accompanying are direct quotes from the filmmakers further explaining the shot.

Interviews and annotations have been edited for length and clarity.

Words by Ilia Rezaei Rad & Sidney Shaw

courtesy of the filmmakers

Berkeley Reyes (he/they) is a fifthyear urban forestry student at UBC who started his artistic journey with photography and later transitioned into filmmaking. When he arrived at UBC in 2021, he joined a media club for fun, using a Roblox edit in place of a portfolio.

Now, Reyes primarily works as a chief lighting technician and gaffer, specializing in programming and board operating for productions. He also works as a director of photography and cinematographer.

In terms of storytelling, they prefer more grounded and character-driven narratives, with a dynamic yet cohesive visual language displaying

the emotions of each character. Reyes pointed to the universality of film in comparison to mediums like literature and visual arts.

“Even if I don’t have money for paint, I have a silly little camera on my phone, and I can make a movie out of that,” he said.

Reyes believes that, while filmmaking is about creation, it’s also about who you collaborate with and the stories you make together. “[Even if] the short doesn’t turn out great, it’s all about having fun, and I’ve been incredibly privileged to have fun at my job, make friends [and] do cool things,” they said.

Reyes’s artistic inspirations include

many artists — especially cinematographers. Adam Newport-Berra, who worked on a few episodes of Euphoria, is one of his biggest inspirations. A message that has stuck with Reyes is Newport-Berra’s emphasis on working as a team as opposed to individual skill. Another is Marz Miller, a commercial cinematographer who Reyes finds inspirational for his polished and pastel-coloured film shots.

Reyes also finds artistic influence in his academic life, particularly forestry’s language of design. In urban forestry, you’re “building a narrative around a site design,” they said. “Which I think correlates [to film], because you’re telling a story in

two different mediums. One is where you’re placing trees … and the other is telling a story with a camera and production design.”

Even though each of his works have different messages, Reyes’ broader philosophy in filmmaking is about embracing imperfection, and how the road to creating an image is equally as important as the final product.

“I was doing lighting design for a short film two years ago, and …. I was like, ‘What if I just put this 1.8 kilowatt lamp shooting right into [the subject’s] face?’” he said. “I made it messy, but messing it up helped drive the narrative.”

This was from a short film I shot in 2024, called Soles. Essentially, our lovely actor, Emily, gets a pair of shoes in the mail, and they turn out to be haunted. This scene is just before the power goes out. We wanted it to be calm and cozy, but you know that something is coming.

In the frame, we have a little practical light, which is motivating a lot of the light hitting her face, like this soft glow, but it’s just such a small light that can’t really wrap around the whole body. So in reality, we pulled out a four-foot light tube called a titan tube, and it’s basically just casting a really warm glow across the frame.

Compositionally, it is a bit of a Dutch angle. It may have just been a practical thing, because this was a shoebox basement suite. We had no room to set up, so we were like, ‘Oh, we can just do an angle.’ And it worked out, that sort of foreshadowing of ‘it’s gonna be spooky soon.’

This one is a short film; the current working title is Preachers of America. Essentially, you’re watching this preacher give a sermon that’s really dramatic, and then it’s revealed it’s an audition. The message of the piece is about the performative nature of a lot of things in modern society.

We just shot this in black and white from the get-go because we want it to have a timeless look and not feel too spectacular. Because oftentimes with colour, you’re adding a lot of elements, and all of that would distract from the main thing, which is the contrast of what’s being verbally said and what’s being metaphorically said.

Another part of that was the lenses I used. It has some amount of softness to it and I wanted that because it’s with black and white. There is the risk of having too much contrast or too much sharpness, and we want to take that sharp digital edge off of the film and make it more timeless.

This shot is from a short film called The Girls Before Us. Essentially, it is about three friends trying to bring their mothers back as younger versions of themselves so they can relive the wonderful, joyous, whimsical lives that they missed out on in adulthood. This is just before that ritual.

I love shooting in the woods because on overcast days, you get a very beautiful, soft, top-down light. So you get this beautiful wash over the whole thing, playing into that idea that less contrast is more whimsy and high energy and fun.

There are some shots where the subjects fall out of focus, but even that helps embrace the high energy, whimsical nature of the scene. Also, the contrast of reddish skin tones, flowers, white dresses, the dark forest and the sky create these pockets of attention that draw your eye and immerse you in the story.

Ryan Kwan (he/him) no longer tries to get the prettiest shot. Instead, every frame is designed to convey meaning — including all its imperfections.

Kwan’s filmmaking journey started when he was randomly assigned the role of director of photography in his first-year film production class. The following year, he continued to get involved through the film production club IndieVision — picking up information from YouTube, talking to other filmmak-

ers and working on set. Now in his fourth year, Kwan has worked in a range of roles from gaffer to grip, but he noted how his interest has shifted from the camera to lighting.

“Ninety per cent of how something you shoot looks is just the lighting, and maybe 10 per cent of it is what you’re doing with the camera,” he said.

Throughout our hour-long conversation, Kwan repeatedly came back to the theme of creating shots — not necessarily to look the most

aesthetic or realistic, but to convey meaning and the filmmakers’ version of reality. In his recent short film Jinsei No Toki (2025), this mindset became particularly clear.

The film follows the story of a mother and daughter who have a loving, yet sometimes clashing, relationship. The film opens with the daughter having been accepted into her dream school, and her mother finding out that she must return to Japan, perhaps forever, to care for her own elderly mother. In the week

leading up to her departure, both mother and daughter navigate the complexities of their relationship and leaving home.

As director of photography, Kwan spoke of the use of lighting and camera techniques to convey the story.

“A lot was thinking not, ‘How can I make this look the best I can?’ but more so ‘How can I serve the story the best I can?’” he said. “You’re portraying a version of reality that people could believe.”

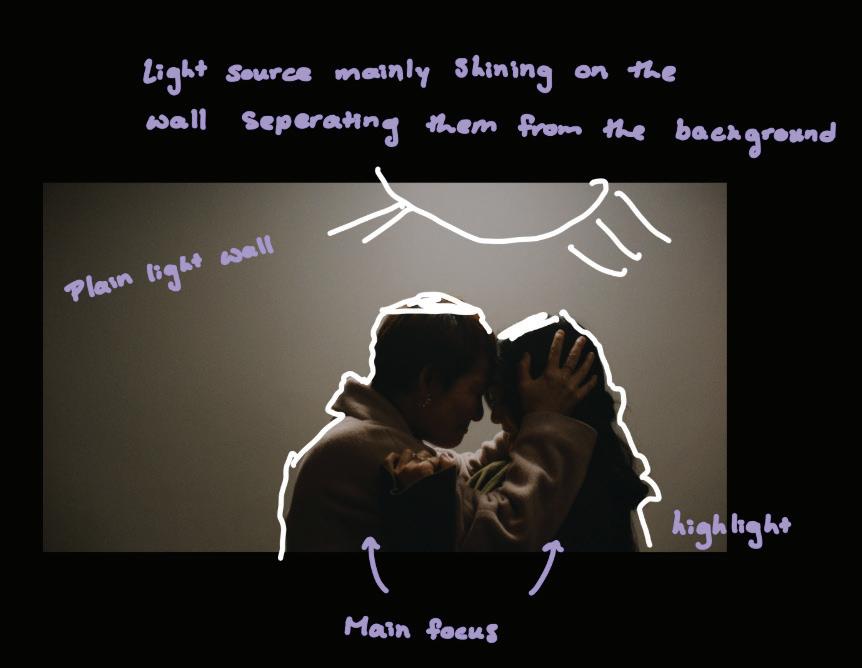

This shot is the peak of the conflict between the mother and the daughter. She’s gotten home after a night at her friend’s house where she didn’t tell her mom. This is a scene where she’s directly and clearly and evidently rebelling against her mom.

Originally, this scene was supposed to be in another room, but I really pushed for them to move to this room, just because how the stairs were laid out. I think it suited what was going on in the story really well because you have this very literal divide between them.

The mom is mad, but the mom is also trying to get her kid back because she’s leaving very soon. The daughter is silhouetted, so we’re more focused on the mom and how she’s feeling here. We already know how the daughter feels. We’ve established this already, but until this scene, we don’t really see how the mom is reacting to the way her daughter is.

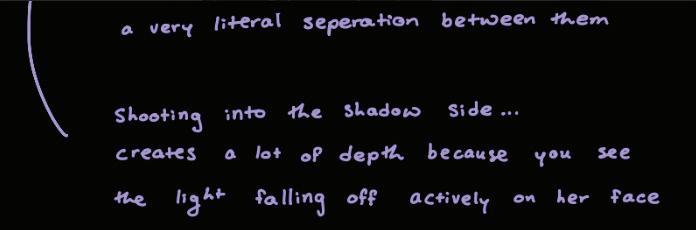

This is right at the end, right before the mom’s leaving.

This scene is probably the most emotional scene of the whole film. So what do you do? You silhouette them because when you put them into the shadows, that helps to convey emotion, that helps to convey drama, especially when you can barely see their faces but you can clearly see what they’re doing. You see their movement and their body language is saying more than their faces could.

This is the most stylistically-charged shot in the whole film, because I wanted it to feel a bit surreal. Because when you’re leaving people you’ve known your whole life, it feels weird, right? It feels a bit surreal. This concept is called emotional realism. So this is subjective in a sense that I’m putting the audience in their world, and I want them to feel the surreal emotions that they are feeling in this scene. For that reason, the lighting is more stylistic, and I’m almost silhouetting them, even though this is something you probably wouldn’t see in real life. So when you switch up the style like this, it makes it that much more impactful.

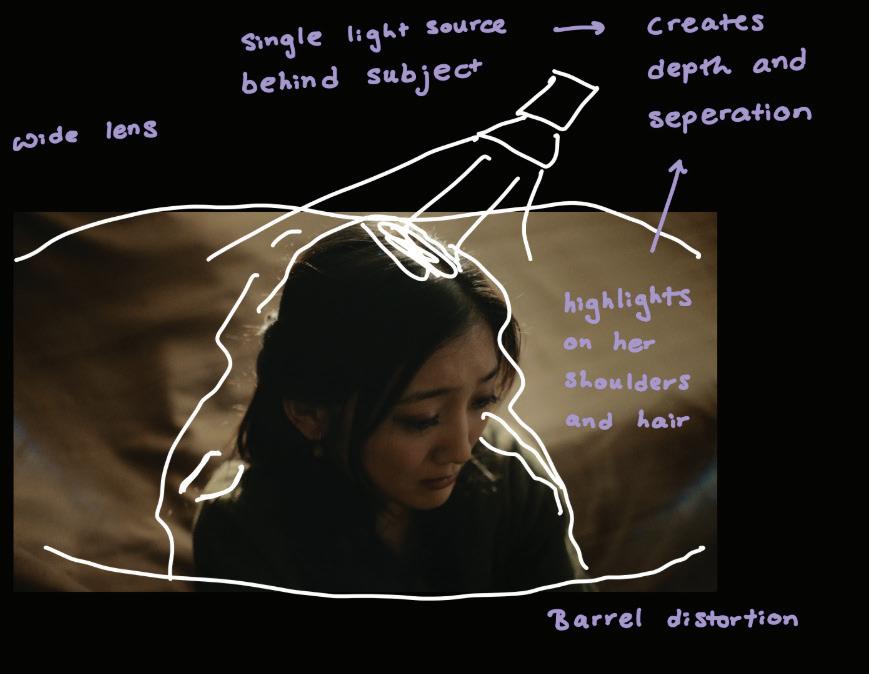

This is when she comes home to try to talk to her mother before she leaves. But she finds the house (spoilers!) looking like her mom has already left. So she’s feeling defeated here in that she didn’t really get to say goodbye to her mother.

This shot has more to do with the camera when you take a wide lens and put it really close to someone, you get an interesting effect, because a wide lens kind of distorts the field of view a bit. The cool thing about wide lenses is that they’ll often have really, really close focus ranges so you can put the camera much, much closer to someone and get focused on their face and get much closer than if you were on a longer lens.

In this shot we’re going for something that’s very subjective and we want to be intimate. We want to get as close with her as we can, to really get into her head and how she’s feeling.

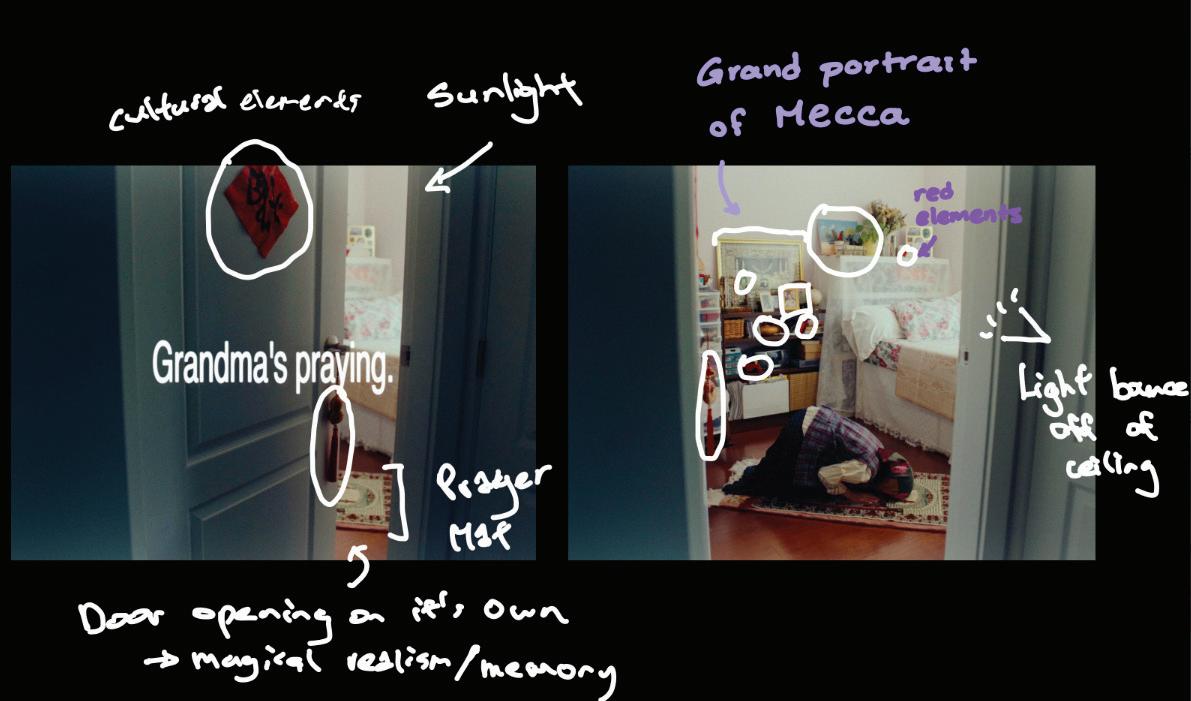

To Matthew Jin (he/they), a fourthyear BFA acting student, the screen is a way to encapsulate memory. So when they had the opportunity to create a film through the Vancouver Asian Film Festival’s Mighty Asian Moviemaking Marathon, they did just that.

In Jin’s semi-autobiographical short film, Grandma’s Praying (2025), a young child living in an interfaith household joins his Muslim grandmother as she prays. As Jin puts it, “the rule was, when grandma’s praying, you don’t disturb her.

But one afternoon … I did disturb her, but it was because I wanted to ask if I could pray with her.”

The film is less about religion and more so about a young child understanding that his grandma’s faith is different from his. Even at a young age, the protagonist understands its importance and wishes to be a part of it to be closer to his grandma.

“It was just a really meaningful experience that I’ve always remembered, and I think it really encapsulated my experience growing up in

an interfaith … household,” Jin said. Grandma’s Praying was shot in Jin’s family home and features his real grandma going through her daily prayers. Though supportive of Jin’s art, she initially refused to be in the film which, to her, was a form of entertainment that directly clashed with her extremely serious stance on religion. However, Vancouver’s Chinese Muslim population is small, and Jin was left at the last minute without a lead actress.

“I kind of broke down to my grandma … and really tried to make

This is the grandson’s hand here that’s sort of tapping on the grandma as she’s praying. When we shot it, she was more centred, but in the edit, we wanted to play around with empty space. Although it’s just his hand in the shot, the attention actually goes towards the hand rather than the [grandma] to have more of a mystery.

I spent the majority of my budget on the production design. Obviously it’s not grounded realism, but I think it’s little things in the background that adds the depth of a room. It makes a room have a bit more coziness and personality, which I think is reinforcing that intimate feeling that I wanted.

We added grain and the white vignette. I just found that those elements made it seem a little more nostalgic, and it almost takes you away from reality. And the lens that we chose was purposely a bit softer and mixed with the softness of the lighting as well. I think it just gave a really nice, dreamy kind of feeling.

her see, from my perspective, the value of media,” they said. “It is for entertainment, it is for a competition, but it’s also, for me, a way of capturing someone’s life and a moment that I want to remember someone else by.”

She agreed, and throughout the process, Jin took extra steps to ensure that he was sensitive to her religion. “Beyond a filmmaking experience, it was really a familial, personal journey that I got to have,” he said.

In the opening shot, there is audio of me saying the title card, which is “grandma’s praying,” but in Mandarin. It’s to show the sense of memory, that what I’m depicting is very subjective, and it’s very much at the presence of someone who’s looking back on the past. So the door is opening to my recollection.

The really interesting thing about this particular shoot was the sensitivity of capturing certain things, like religion, on film. Usually you place the camera, and then you see the backdrop, and then you put the actors in. It was actually the opposite, because in Islam you can only pray in one direction. Being that my grandma’s very sensitive to the meaning of media and trying to keep it as respectful as possible, we realized that if this is actually the direction that you have to pray in real life, then that’s got to be how it’s going to be in the film.

When it comes to colour, one thing that my director of photography actually asked me was, ‘When you think about your film and you close your eyes, what colour do you see?’ And for me, I thought of red. So my production designer found little things that we could put in the image to show that there’s red. Beyond emphasizing the cultural colours of Chinese Taiwanese culture, I think it does bring a sense of warmth and invitingness.

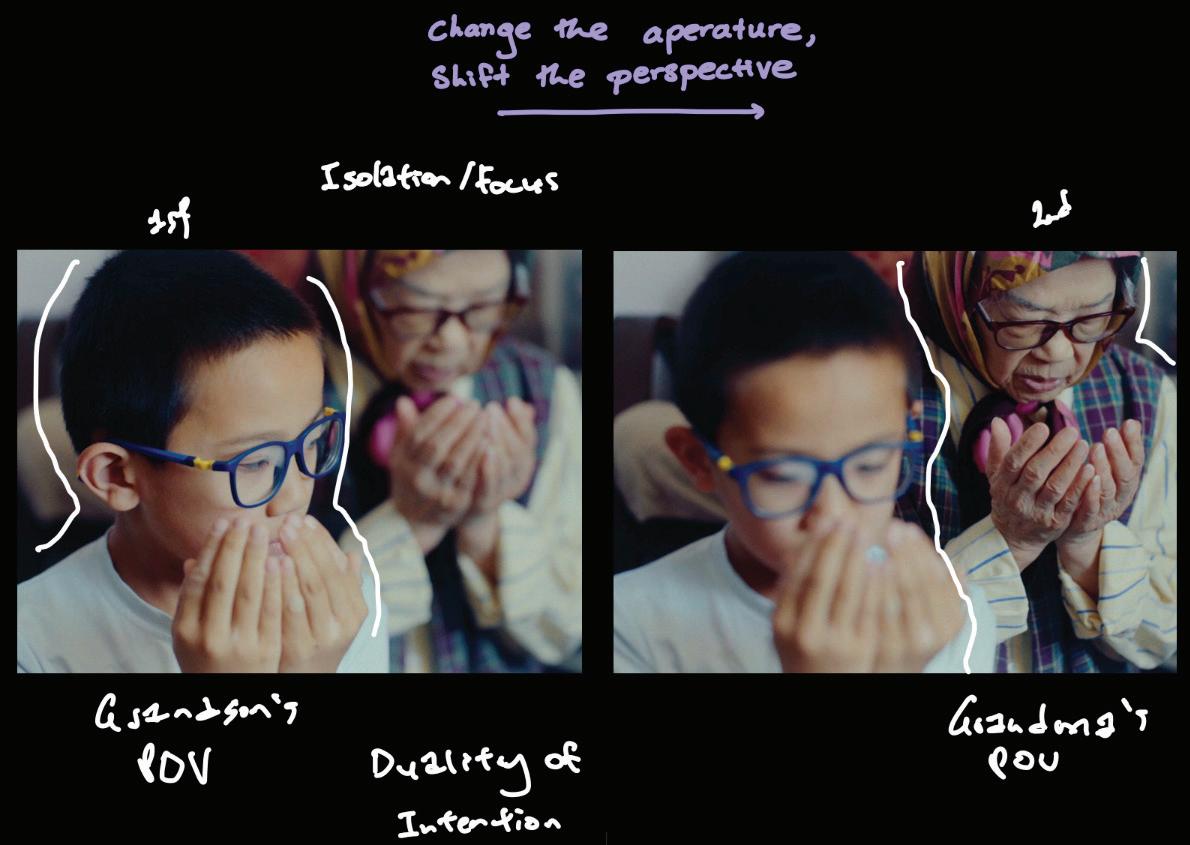

In these shots, the grandson brings in a sleeping blanket, which has elephants on it. It’s very childish, definitely not appropriate for praying on.

But I think using the child’s mind of like, ‘I just want to be with my grandma. I want to share this with my grandma,’ he brings this elephant blanket with him, and then she lays it down next to her, and then he kneels down in a praying position.

Praying together can almost mean more than sharing a religion. Actually, it’s sharing a moment of mutual understanding for something that the grandson cannot understand. And so with the grandson, as much as he’s looking down to his hands as he’s praying, he’s actually looking back towards his grandma. His intent is not to be one with God, or to speak with God. His intent is actually to share this moment with his grandma.

Once we get to this point, we shift the perspective, we change the aperture. And then we’re seeing the grandma, who is focused on the task. So it’s really to show the differences in the experience and the perspective between these two subjects. Ultimately, I think the film is still captured through the perspective of the child, but I just want to show that duality. These two people are doing the same task, but their experiences and reasoning for doing the task is very, very different. U

by Mayvelyn Bugh, Sidney Shaw & Zoe Wagner