UNDER THE SKIN

An artistic response to species extinction

RANGER FROM A TOWNSHIP

Inspiring conservation with the Ubuntu Philosophy

THE AFRICAN AQUATIC CONSERVATION FUND

Preserving the endangered African Manatees

Protecting the only bear species in Southern America with textile making

MAGAZINE Issue 5 | Spring 2023

www.ubuntumagazine.com YOUR NATURE CONSERVATION STORIES

JUCUMARI PROGRAM

@ubuntu.magazine.official @ubuntumagazineofficial @ubuntumagazine @ubuntumagazine JOIN US ONLINE Transform Your Perspective on Nature: Follow Ubuntu Magazine’s Social Channels!

YOUR NATURE CONSERVATION STORIES

Ubuntu Magazine transforms your perspective on the natural world. Our aim is to create awareness around the beauty of the world, by putting a spotlight on the conservationists working day and night to conserve our surroundings. Only with thorough research and sharing knowledge, we can assure ourselves of a bright, biodiverse future.

With Ubuntu we broaden our perspective in living together with nature, instead of alongside it.

Emerge yourself in the articles and become inspired.

CONTENTS

Eveline Gerritsen |

Protecting the planet with the Ubuntu philosophy?

Introduction

Let’s live Ubuntu.

Australian Wildlife Conservancy (AWC)

Rewilding Australia: the run for undoing human mistakes.

The Jucumari

Protecting the only bear species in Southern America with textile making.

Frank Landman

How to accelerate the SDGs with the IDGs.

Eveline Gerritsen

Protecting the planet with the Ubuntu philosophy?

African Aquatic Conservation Fund Protecting Africa’s endangered manatees.

Jucumari Program

Protecting the only bear species in Southern America with textile making

Interactive Table of Contents: Click to Jump to Articles Instantly! 07 08-19 20-29 30-33 34-41 42-51

20

08

5

fairGROVE UG Combining Science and Conservation of Mangrove Forests Sea Shepherd Fighting against illegal fishing in Africa Stargazer Wessel Veenbrink Under the Skin An artistic response to species extinction. 52-59 60-69 70-77 78-85

Sea Shepherd |

60 70

“I am, because we are.”

52

Stargazer | Wessel Veenbrink

Fighting against illegal fishing in Africa

fairGROVE UG | Mangrove Forests

UBUNTU LIVE LET’S

A victory worth mentioning!

Last December, the 30x30 pledge was made at the UN Biodiversity Conference. The pledge stated that we should protect 30% of land and 30% of the world’s oceans by 2030. Now, we finally put a critical step forward in achieving this pledge. At the beginning of March this year, the High Seas Treaty was signed to protect the high seas – the international waters where all countries have a right to fish, ship, and do research. It is a true achievement that 196 countries have now agreed on the protection of these waters after decades of talking. The treaty will play a vital role in establishing MPAs (marine protected areas) in these waters.

To many of us, the high seas are as remote as it gets. Therefore, they are often forgotten – which is why for a long time they didn’t get the attention they deserved. Luckily for us, we are able to observe the beauty of the oceans closer to shore which brings us one step closer to those majestical high seas so far away. To honor the world’s water, we included three diverse, but all just as intriguing articles, about water-based ecosystems. With Peter Hammered from Sea Shepherd, we talk about their work to combat illegal fishing along the West African coast. With Martin Zimmer and Véronique Helfer from fairGROVE UG we dive deeper into the world of mangroves. And we talk to Lucy Keith-Diagne from the African Aquatic Conservation Fund about the conservation of

African manatees. Although all of them work in different water-related environments, there is a lot to discover about the conservation efforts needed in those areas.

Talking to these conservationists, I am reminded of my earliest memories at the beach. Once a year we would visit the coast to enjoy the crashing of the waves and hunt for treasures along the shore. Finding a shark egg was the highlight of those days. Although visiting the coast became less frequent, the attracting force of the ocean remained. It brought me up to Iceland, where I was able to work with humpback whales, which ignited an even bigger flame to discover the unknown world of the oceans and deep sea. I hope that the articles in this issue will ignite curiosity in you, a curiosity to discover more about the underwater world that surrounds us.

Whilst we have this huge High-Seas Treaty to celebrate, we cannot forget about the beauty of our flora and fauna on land as well. Did you know that the Andean bear, which lives high up in the Andes mountains, faces several threats in its daily life? And did you know that the Australian Wildlife Conservancy works on creating safe havens for Australian wildlife? It’s a good thing that people like Elmonique Perterson are working on conservation with an Ubuntu perspective, and that people like Ed and James Harrison put their skills, in this case in printmaking, to good use by sharing unique prints of endangered species.

6

It is clear that once again, you can find a varied set of interviews in this issue of which I am very proud. With the High Seas Treaty signed and the knowledge that there are countless inspiring conservation organizations to discover, – both on land and at sea – I remain hopeful that we will succeed in our 30x30 pledge to protect 30% of the planet by 2030.

- Manon

- Manon

7 INTRODUCTION

www.ubuntumagazine.com

@ubuntu.magazine.official

Website

Instagram

8

REWILDING AUSTRALIA: THE RUN FOR UNDOING HUMAN MISTAKES

Life can be complicated. How many times have you left home in the morning prepared to solve problems that haven’t even happened yet? The worst part is that you really believe they will materialize, and it often leads to another dilemma – “what if they don’t?” If these imaginary problems don’t come true, your itinerary may change radically and, maybe, you find yourself in trouble anyway.

This is just one of the reasons why social networks are so convoluted. However, ecological communities can be far more complex. If you think that trying to understand your own life path is enough of a headache, try to imagine how it would be to solve a giant puzzle that encompasses a whole ecosystem that literally contains billions of life forms. As a bonus, also try to anticipate the path this ecosystem will take with the addition of new species and individuals. That’s pretty much what the Australian Wildlife Conservancy (AWC) must handle in its sanctuaries.

9

Newhaven Wildlife Sanctuary is located hours outside of Alice Springs and home to a 9,540-hectare feral predator-free fenced area, one of the largest on mainland Australia.

AUSTRALIA

Photo Credit: Brad Leue/Australian Wildlife Conservancy

“We actually run the largest and most ambitious Australian translocation program.”

The AWC is a non-government agency founded in the early 90s by a British businessman called Martin Copley. Even at that time, he was aware of the species’ decline that took place around the world. After falling in love with Australian wildlife and learning about its problems, he thought there must be a way to prevent local extinction. Keeping in mind that most of the damage was caused by exotic species, he had to keep domestic cats and red foxes away to native species. In his way, most of his visionary ideas became a reality – the creation of safe havens. These wildlife sanctuaries encompass thousands of square kilometers of natural landscapes, and some of them are completely surrounded by electrified fences over six feet high. It started with the purchase of a property in Western Australia

and, with the help of some of Copley’s associates, culminated in the Australian Wildlife Conservancy. However, as simple as Copley’s idea seems to be, this is not just about building a fence, a kind of “ark” on dry land. These species must be chosen carefully, and their populations are monitored over the long term.

“We actually run the largest and most ambitious Australian translocation program. In central Australia, where we have a sanctuary called Newhaven, there are up to 20 native mammals missing from that landscape that were there about 150 or 200 years ago. For some of those, there are some populations elsewhere,” says Joey Clarke, Senior Science Communicator at AWC. Among the species that have been successfully

10 AUSTRALIA

A Bilby reintroduced into a 9,540-hectare feral predator-free area at Newhaven Wildlife Sanctuary in Central Australia.

Photo Credit: Brad Leue/Australian Wildlife Conservancy

reintroduced by the AWC are the Brush-tailed Bettong or Woylie (Bettongia penicillata), the Central Rock-rat (Zyzomys pedunculatus), the Greater bilby (Macrotis lagotis), the Mala or Rufous Hare-wallaby (Lagorchestes hirsutus) the Red-tailed Phascogale (Phascogale calura), and many others, all of them are endangered and threatened by invasive species and extensive wildfires. Some individuals are then brought from remaining populations in coastal islands to sanctuaries (where feral invasive species have been eradicated), for reintroduction. “There are two reasons behind the translocation program. The first reason is that these species were heading toward extinction, and the second is that they do a job in the ecosystem,” says Clarke.

The set functional roles played by species regulate the ecosystem and dictate how the landscape will look. Those species called “ecosystem engineers,” for example, are constantly modifying the environment and creating opportunities for other species to thrive. Bilbies and bettongs, and other burrowing mammals, for example, provide important contributions to the ecosystems including higher rates of water infiltration, increasing soil stability, and even shelter for other animals (e.g., snakes). “We watch that happening, you go back there and there are burrows throughout this area, there are plants springing out of those burrows, it is really fantastic to see,” says Clarke.

11

A Brush-tailed Bettong taking in its new environment in the Pilliga State Conservation Area where Australian Wildlife Conservancy works in partnership with NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service.

Photo Credit: Brad Leue/Australian Wildlife Conservancy

A Critically Endangered Central Rock-rat reintroduced to Newhaven Wildlife Sanctuary in Central Australia in July 2022.

Photo Credit: Brad Leue/Australian Wildlife Conservancy

12

Strath Barton carrying out a North West Fire Management Program.

Photo Credit: Brad Leue/Australian Wildlife Conservancy

13

Unfortunately, as tall and sturdy as the fences surrounding the AWC sanctuaries are, they fail to prevent another major threat to Australian biodiversity: the extensive or “hot” wildfires. “Australia has been managed by aboriginal people for tens of thousands of years, probably 60 to 80 thousand years. That involved a lot of use of fire in a patchy and low intense way. However, when aboriginal people were taken away from their land, this kind of management ceased. The problem with that is that if you don’t have these ‘cool’ fires happening every two or three years, you get very big (‘hot’ fires). Although the ‘hot’ fires are less frequent, they can be much more harmful,” says Clarke. In certain regions of Australia, it has been demonstrated that open vegetation managed by aboriginal people until the 18th century (pre-colonial period) limited the availability of biomass fuel loads. Additionally, this problem seems to be aggravated by climate change and eventual climatic anomalies. “We know that extreme weather events and heat waves are getting more extreme, and in Australia, there is a climate system called El niño/La niña, in which El niño represents the dry part of the cycle

and La niña is the wet one. We know that El niño years are becoming hotter and drier and that’s why we get those big bushfires like the ones we saw three years ago (in southern Australia). This is very scary because we can improve fire and vegetation management but when conditions are getting that extreme, towards 50°C, it is very hard to manage that. On the other hand, there are a lot of species in Australia that are used to fire so it might not be as devastating compared to other continents., As always, it is just more complicated than what we hear in the news”, says Clarke.

Fire management represents a major challenge that is faced not by AWC but by other entities around the world. Not only because of the

14

“If you don’t have these ‘cool’ fires happening every two or three years, you get very big ‘hot’ fires.”

AUSTRALIA

Kirsten Skinner and Jennifer Anson, Australian Wildlife Conservancy Ecologist.

Photo Credit: Brad Leue/Australian Wildlife Conservancy

complexity of this type of activity but also because of the conviction of the part of the population and the government that in some situations this is the best solution. “I think this is quite a complex issue, and even within Australia, most people think that bush fire is bad. It is really important to tell the other part of the story, which is that fire has been part of the Australian landscapes for thousands of years. Especially in north Australia, where there is a grassland/savanna ecosystem, we don’t have big herds such as zebra, bison, or buffalos, it is actually fire which is the biggest herbivore. The landscape has evolved with fire as a regular part of the cycle in the same way as floods and rain. The AWC has been working on restoring a healthy fire regime. They’re doing so through a partnership with aboriginal Australians, which has been fantastic”, says Clarke. In addition to the danger posed by the excessive biomass fuel load, there are other consequences for such abrupt changes in the landscape. The phenomenon known as “woody encroachment” can be defined by the gradual increase in the density and cover of vegetation in open ecosystems such as grasslands or other kinds of savannas. While this process can be advantageous for forest dwellers, it poses a threat to open habitat specialists.

Although a considerable amount of information about landscape ecology and the effects of fire on biodiversity has accumulated during the last decade, little effective action has been taken toward conservation. “I think there are lots of people studying the decline of species; they measure it, write reports, and publish papers about it. However, what we need are people on the ground that intervene. In Australia, we have a good network of national parks run by the government, but we are still seeing animals disappearing from those national parks. The approach that our organization takes is the following one: science is important, but land management is just as important. We have got both scientists and land managers in the sanctuaries doing their jobs at the same time. They are learning how fire affects different species, which makes the job very practical”, says Clarke.

Dr Vicki Stokes, Australian Wildlife Conservancy Senior Wildlife Ecologist, releases a Brush-tailed Bettong into the 580-hectare fenced breeding area.

Photo Credit: Brad Leue/Australian Wildlife Conservancy

Dr Vicki Stokes, Australian Wildlife Conservancy Senior Wildlife Ecologist, releases a Brush-tailed Bettong into the 580-hectare fenced breeding area.

Photo Credit: Brad Leue/Australian Wildlife Conservancy

One of the Numbats reintroduced to Mallee Cliffs National Park, where Australian Wildlife Conservancy works in partnership with NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service.

Photo Credit: Brad Leue/Australian Wildlife Conservancy

One of the Numbats reintroduced to Mallee Cliffs National Park, where Australian Wildlife Conservancy works in partnership with NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service.

Photo Credit: Brad Leue/Australian Wildlife Conservancy

The AWC is an organization that leads the conservation of entire ecosystems. This is a complex and ambitious task that must be seen as equally beneficial to human beings. The resumption of the healthy functioning of these landscapes should contribute to greater stability of human-nature relationships. “The systems that we work with here are complex and we don’t know everything about ecosystems, but I do think we know enough to manage them well and improve how we are looking after these landscapes,” says Clarke.

You can help AWC restore Australian wildlife through donations and by spreading the news about their work. “In conservation, we tend to hear about things disappearing, going extinct, and the decline of ecosystems. So rather than just saying that other species have gone extinct, sharing good news and having a sense of optimism is really helpful,” says Joey Clarke.

18

Australian Wildlife Conservancy’s field team carried Brush-tailed Bettongs from a chartered flight for a reintroduction to Mallee Cliffs National Park, where Australian Wildlife Conservancy works in partnership with NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service.

Photo Credit: David Sickerdick/Australian Wildlife Conservancy

Instagram

@australianwildlifeconservancy

Linkedin

@australian-wildlife-conservancy

Facebook

@AWConservancy

Website www.australianwildlife.org

19

20

THE ONLY BEAR-SPECIES IN SOUTHERN AMERICA THE JUCUMARI

High up in the Andes, hidden from plain sight, the Jucumari roams the mountains during the night. This bear, also known as the Andean Bear or the Spectacled Bear, is quite unique as it is the only bear species on the South American continent. People in the Andes once believed the Jucumari was half-human, half-bear, able to make connections with ancestors. Nowadays, this myth is rarely believed. The Jucumari, once so beloved and mythical, is now in severe decline and in need of help.

21

SOUTH AMERICA

Andrea Fuentes Arze, the founder of the Jucumari Program, works on the conservation of Andean Bears in Bolivia. She is an environmental engineer, which gives her the ability to look at environmental issues from a broad perspective. She combines that ability with her understanding of small, local communities in order to work on a delicate topic – the human-bear conflict.

With the Jucumari Program, Andrea combines research about the species with so-called community conservation.. Andrea explains: “Our

aim is to create co-existence between the bears and local communities. To do so our program is multi-layered. On the one hand, we carry out research on the bears and their habitat, and on the other hand, we try to understand the core problem of the human-bear conflict and work with communities to find a solution.”

LIFE OF AN ANDEAN BEAR

Found in the cloud forests which are high-altitude ecosystems, the Andean Bear is a diurnal species. During the day they roam around their habitat in search of plants, seeds, and fruits to consume. To reach the food they climb in trees and upon rocks, making this bear a true athletic forager. Although it sounds like a calm and serene life high up in the Andes, the current situation is rather different for the Jucumari.

Currently, deforestation, illegal trafficking, and human-bear conflict are the top three threats the Andean Bear faces. The latter of those – the human-bear conflict – is the largest in Yungapampa, the region where Andrea works. Here, communities live at the same altitude and in the same habitat as the Andean Bear. Many

22

SOUTH AMERICA

“For local communities, the only direct solution is to kill the bear to prevent it from threatening their livelihood again.

of the communities in Yungapampa depend on their crops and their cattle for a living. Crops and cows, which can usually be found close to their homes, are unfortunately a great source of food for the Andean Bear. Crop raiding is therefore the number one cause of the humanbear conflict. However, being an opportunistic species, the Andean bear feeds on whatever might be available – especially when a wandering cow is the easiest catch of them all. So instead of being fully herbivorous like most bears, the Andean Bear is actually omnivorous as it will catch a cow whenever the opportunity arises. It, therefore, poses a threat to the communities’ crops and cattle. For local communities, the only direct solution is to kill the bear to prevent it from threatening their livelihood again.

COLLABORATING WITH LOCAL COMMUNITIES

One of the difficulties they face is a language barrier. The people high up in the Andes speak Quechua, a language that Andrea is learning but does not speak fluently. Luckily, her team member Veronica does, which enables them to communicate with the locals. Nevertheless,

sharing their message about why they want to protect the Andean Bear remains difficult. For locals, the first impression and big takeaway of the general message is that it will restrict their livelihoods. To change this perspective, it is important to work on a genuine relationship with these local communities.

Since 2021, Andrea has been in contact with some women from these communities. Knowing that the human-bear conflict increases financial pressure within the communities, Andrea first helped in the search for a solution. Creating different opportunities and means of income – opposed to solely focusing on crops and cattle – is a great way to relieve this pressure. Of the many options Andrea gave them, creating textiles appealed most to them. Kanti Andino, as this textile project is called, has worked out great so far. Besides the fact that this project has created an additional source of income for these communities, it has also opened doors for Andrea and her team into other local communities. The positive results of Kanti Andino have enabled them to further expand their conservation area.

23

SOUTH AMERICA

24

RESEARCH IS THE FIRST STEP IN SAVING THE JUCUMARI

Research is a big part of the conservation approach. Andrea explains: ‘’Our ecological research, studying the life of the Andean Bear, starts right away. Studying a species such as the Andean Bear is difficult, so we need to take our time there. We want to know where the bears live, what they eat, and what their general life looks like.’’

Besides studying the bear itself, it is equally important to research the way of living of local communities. Talking to the people – which is possible now that we have established a relationship through Kanti Andino with them –is needed to understand where they leave their cows when they are grazing without supervision, what the cows do while grazing, and what they mean to the people in terms of money. This all adds to our community conservation approach.

LOOKING FOR BEAR-TRACKS

In the past years, many of Andrea’s days have been spent in the field to answer her research questions about the Jucumari. That does not mean, however, that she sees the bears daily. During her long and strenuous days at high altitudes, it is rare to spot it in real life. Therefore, her team members, and a local guide and Andrea focus more on signs that the bears have been there. Nests in trees or high up in the mountains are great examples of a bear that has been there. Their local guide is one of the most important assets while doing fieldwork.

25

SOUTH AMERICA

“Besides studying the bear itself, it is equally important to research the way of living of local communities”

Andrea adds, “Our guide is our masterpiece in the mountains. We are learning so much from him, as he sees all these amazing details in the landscape. Even though we use GPS, camera traps, and more, it is always his knowledge that brings us to the bear – or to remnants of his passage. The interesting thing is that our guide, who comes from a local village, is also the hunter of that village. Since we have been working with him, we have seen a change. Instead of being a hunter, he is now becoming a conservationist more and more. I wonder who is learning more –we or him.”

THE EFFECT OF COMMUNITY CONSERVATION

Alongside her days working in the field, Andrea has been in many conversations with local men and women. Overall it is clear that community conservation is working. It is a long process, but a change is noticeable. The relationship established through Kanti Andino has proven to be very effective and the bulk of information that she and her team have already gathered about the local way of living should be enough to mitigate the conflict between these people and the bears. Although co-existence might not have been reached yet, the past three years have been great in further understanding the core of the conflict. Andrea is positive about a solution and the protection of the Andean Bear. She is full of plans which she will conduct with her team in the coming years.

26 SOUTH AMERICA

27

Are you curious yet about the Jucumari and Andrea’s work on the Jucumari Program? Then take a look at their social media! And don’t forget that Program Jucumari could always use passionate volunteers in the field.

28

Linkedin @programajucumari Instagram @programajucumari Facebook @programajucumari SOUTH AMERICA

29

FRANK LANDMAN

HOW TO ACCELERATE THE SDGS WITH THE IDGS

In 2015, the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) provided us with a comprehensive plan to create a sustainable world by 2030. This list, comprised of seventeen goals, covers a wide range of issues that involve people with different needs, values, and convictions.

in a slower process than initially expected. An inventory of our inner skills and capacities is exactly what we need to encourage us to grow –and to accelerate our progress.

Previously, I wrote about the balance between the five types of intelligence in order to make the

Now that we have passed half of our time toward this goal, it is clear that progress is slow. In order to succeed, we have to accelerate. What can we as individuals and organizations do to be more effective in the work towards greater sustainability and well-being?

Interestingly, we can find the answer to this question within ourselves. In essence, the world is a reflection of us and the choices that we make. So, something must have been missing, resulting

right decisions. These five types of intelligence – ecological, physical, spiritual, emotional, and cognitive – should be applied in perfect balance to make them work. However, when stating this I was faced with criticism based on the fact that people mainly make cognitive decisions without including the other types of intelligence. So how do we reach an effective equilibrium?

The key lesson that we have to learn – and apply – is the fact that everything starts and ends with

30

us as human beings and our abilities to make long-term decisions. We possess the ability to make decisions directed toward success, yet we still have to do so.

First of all, the goals don’t become a success by themselves, people will have to do it. Secondly, the targets are approached quite technically without adding depth to the core of the goals. Lastly, the coherence between goals is hardly sought nor found. Neither of these reasons has anything to do with the goals themselves, as the goals have been well thought through. There is simply very little to argue about. Yet as stated before, it is about the human being who fails to interpret them the right way.

It is clear that if we want to achieve the goals in 2030, it requires enormous commitment and devotion, but also certain qualities and talents from everyone. In 2021, a movement – named the Inner Development Goals Community -- arose in Sweden to focus on this. The question arose regarding what qualities, competencies, and talents you need to make the SDGs a success so that we can achieve the UN’s SDG agenda in 2030. It was clear that it had to be about deepening and developing ourselves so that we can better understand the core of the SDGs.

Questions like “How do you relate to nature?”, ‘How do you place the SDGs in a holistic context?’ – realizing that they are global issues that must

be tackled through collective leadership and ‘How do you translate these global issues to the local level?’ were present in the development of the Inner Development Goals (IDGs). Answering these questions, amongst others, will result in the ability to increase awareness about the importance of the goals among others.

The IDGs consist of five categories, subdivided into 23 skills that you can develop. The five categories are:

1. Being. The relationship with yourself. How do you relate to yourself? Competencies: inner compass, integrity and authenticity, openness and learning mindset, self-awareness, and presence.

2. Thinking. Cognitive skills for focus: critical thinking, complexity awareness, perspectives skills, sense-making, long-term orientation, and visioning.

3. Relating. Caring for others and the world. Competencies: appreciation, connectedness, humility, empathy, and compassion.

4. Collaborating. Social skills: communication skills, co-creation skills, inclusive mindset and intercultural competence, trust, and mobilization skills.

31

This collection of goals has become the accelerator to reaching the Sustainable Development Goals to create a prosperous future for all of humanity. So let’s dive into this to see how personal development and self-management can be achieved. As there are multiple ways to work with the IDG framework, you can easily choose what fits you best.

One simple way to start, would be to ask some of your friends, colleagues, or children: “If I were to develop one skill from the IDG framework, which one would probably make the biggest difference in my life?” This is one of the simplest ways because you are challenging yourself – yet the task at hand is not too difficult or large to start working on.

Another option is to challenge yourself. Take a look at the following questions. They can help you think about your own behavior and your position in the world. There are a few examples in every domain.

Being:

• What are your three most important values?

• How do you stay open when you have a different opinion?

Thinking:

• Are you nurturing your habit of asking inquiring and critical questions in relation to significant assertions?

• What three things are most important in a 5, 10 and 100 year perspective?

Relating:

• Do you nurture and sustain a keen and deeply felt sense of belonging to a much larger whole such as humanity and the global ecosystem?

• Are you working on your ability to feel empathy and compassion even towards people who are very different from yourself and who may act in ways of which you disapprove?

32

5. Acting. Driving change. Competencies: courage, creativity, optimism, perseverance.

Collaborating:

• Do you feel that you are willing to make an effort to understand and include people and mentalities that are very different from what you are used to?

• What is the best motivation for achieving common goals?

Acting:

• When did you last do something daring?

• What real challenge has helped you to grow?

Although contemplating these questions will surely give you more insight into the SDGs, only real change will accelerate our progress. We need to assess and change our behavior into something that contributes to the SDGs. That

example, think about how “critical thinking” and “knowing your inner compass” will influence your long-term decisions. If you want a future on a livable, flourishing planet, developing ourselves is the only way to reach that. The expectation is that self-development through the IDGs will automatically siphon through to reaching the Sustainable Development Goals.

In the end, it’s humanity that makes the difference, not the system. It would be fantastic if these IDGs could contribute to lowering our global footprint from 1.75 earths per year below 1.0 as soon as possible. It does require a certain humility from us as humans towards nature, but as nature has given us so much beauty, the most beautiful thing we can give nature back is to stop exhausting it and to become one with nature again.

means we need to shift from “what do I want to buy” to “what do I need to buy”. Alongside that, it is important to understand what our position is in relation to nature and to others. Thinking collectively instead of individually is another one of these mental shifts. And, to bring us full circle to the beginning of this column, we have to apply all our types of intelligence - ecological, physical, spiritual, emotional, and cognitive – to our skill of decision-making, so it is important to know which ones of the types you are currently using and which you are currently neglecting.

What makes the Inner Development Goals (IDGs) valuable is that with these skills we are able to think long-term – including our own future, the future of generations to come, as well as the future of society and ecology as a whole. For

FRANK LANDMAN Owner Everlast Consultancy

33

34

PROTECTING THE PLANET WITH THE UBUNTU PHILOSOPHY?

Her love for nature started when she was a teenager, now she has been working in the conservation field for over eleven years. Elmonique Petersen became a ranger at the South African National Parks because she wanted to educate people from her community about nature.

35

SOUTH AFRICA

“I AM, BECAUSE WE ARE”

WHY DO YOU LOVE NATURE?

Nature is the basic necessity of human life. It is the air we breathe, water and food that sustain us, the very element of survival. Nature brings tranquility and serenity, and that is what I love so much about it. It adds so much value to our human life in multiple forms like medicinal importance, sustainable harvesting, biodiversity value and eco-tourism. Without nature, we cannot exist.

WHAT DOES THE UBUNTU PHILOSOPHY MEAN TO YOU?

Coming from South Africa, I grew up with the Ubuntu philosophy, but it can have multiple meanings to different people. The core value of Ubuntu is “I am because you are,” but for me, it means much more. Ubuntu represents diversity, working together as one, and acceptance of all. People are unique, we are all different from each other, but as long as we are self-aware about that concept, and we educate ourselves and the next generation around our differences, we can work together and celebrate our diversity.

SHOULD WE LIVE IN HARMONY WITH NATURE?

I grew up in the suburb East River, a 45-minute drive from Cape Town and known as a more industrial area. So I didn’t grow up with the thought that humans and nature should live in harmony. There was nature around us, like the gentle slopes of the Stellenbosch Mountains and Jonkershoek, but we would never explore any of that. Thanks to programs on TV, like “National Geographic” or a South African program called “Fifty/Fifty”, I became more aware of the impact we humans have on nature and that we cannot survive without it. In high school, I had a very passionate biology teacher, who exposed us to nature in the form of field trips. That really inspired me to be more aware of nature around me. Nowadays, in my work, I see that children are easier to shape through conservation.

36

SOUTH AFRICA

“Nature is the basic necessity of human life.”

Photo Credits: Eveline Gerritsen

Photo Credits: Eveline Gerritsen

Photo Credits: Eveline Gerritsen

Photo Credits: Eveline Gerritsen

WHY DID YOU BECOME A RANGER?

I always had an interest in the conservation field, especially wildlife conservation. So I decided to study Nature Conservation at the Cape Peninsula University of Technology. While I was studying, I noticed the lack of knowledge and awareness about nature within my own community. In Cape Town we have mountains, the ocean, beautiful forests, and we should be proud of that. It is very important that we preserve the beauty of our natural heritage for the future generations.

In my chosen career path, I have pledged to conserve nature. So for the past six years I have been working as a section ranger at the Table mountain National Park, which is part of the South African National Parks (SANParks). While working here, I gravitated to environmental education, due to the lack of awareness in the many communities in Cape Town. SANParks, is the body responsible for managing South Africa’s national parks, and its core values are transformation and social development through providing people with opportunities and exposure. My daily motivation in my work is the positive impact I may have on current and future generations. I believe in the philosophy that the seed we plant today, will be the harvest we reap in the future.

Also, in my personal life, I like to share my love for nature with my family and friends. We go for hikes and some of the friends I grew up with also went camping with me, something that is absolutely not common for people from East River. I see my friends become more considerate with regard to our impact on nature. They become more aware about saving water, for example, and that improvement makes me very happy. It shows me that they have become more educated when it comes to conserving nature.

39 SOUTH AFRICA

WHAT WOULD YOU LIKE TO TELL THE FUTURE GENERATION?

Conservation is vital in terms of the future preservation of our biodiversity, natural heritage sites, protected areas and conservation assets. At SANParks we have various programs that create employment, provide people with natural resources, and we create access to recreation like hiking. Our ranger teams are very diverse, and that gives us the opportunity to understand each other. Everyone at SANParks works hard to protect nature and educate people about it. So for the future, it is important for conservation to be prioritized in terms of funding and resource allocation to ensure future sustainability. For example, environmental crime is as important as general crime and people should be more aware of that.

My message for the future generation is to be aware of your environmental footprint and reflect an environmental ethos in your daily lives. For us rangers, the Ubuntu philosophy is a principle in our daily lives, but I strongly believe that Ubuntu is a way of living for every South African. In South Africa, we are surrounded by so much beauty and diversity. Think about all the species and fauna in our national parks, people from individual backgrounds and the eleven different languages. I believe if we want to protect our natural heritage, the parks and all the beauty within South Africa, we need to start accepting and respecting each other’s differences and be polite in our interaction with other people. Only then we can protect our nature and our planet for all the future generations to come.

40

Photo Credits: Eveline Gerritsen

41

SOUTH AFRICA

“I believe in the philosophy that the seed we plant today, will be the harvest we reap in the future.”

42

Photo Credits: Lucy Keith-Diagne / AACF

PROTECTING AFRICA’S ENDANGERED MANATEES WITH THE AFRICAN AQUATIC CONSERVATION FUND

The African Aquatic Conservation Fund (AACF) is a small, non-profit organization based in Senegal, West Africa. Since it was founded in 2014, the AACF has dedicated itself to the preservation of African turtles, manatees, and cetaceans (dolphins and whales).

Manatee specialist Dr. Lucy Keith-Diagne has now been working with these animals for over 30 years. She founded the AACF with her husband, Tomas Diagne, after seeing drastic declines in aquatic species. At the time, there were no other organizations focusing on African turtles and manatees, and very little was known about them. The organization has grown over the years and now has projects in 11 African countries.

43

SENEGAL

THE AFRICAN MANATEE

There are three species of manatees – the West Indian manatee, the Amazonian manatee and the African manatee, which is the least studied species. The African manatee lives in 21 different countries, where it can be found in rivers, lagoons and the nearshore coastal environment. As long as the species has access to freshwater, they can live in the ocean, where they go to feed on seagrass. Although a lot is unknown about the African manatee, Dr. Keith-Diagne is changing that with her research. In recent years, she and her research colleagues have been able to learn more about the manatees’ lifespan, for example. The oldest one she has found is 39 years old (based on ear bones which have annual rings), but she and her colleagues believe the species can live even longer as manatees have been aged up to 70 years in Florida. By collecting DNA samples, Dr. Keith-Diagne is learning a lot about manatee populations as well. She was able to determine that there are at least four populations of manatees in Africa and they’re working on finding more. They’re estimating that there are around 10,000 manatees in West and Central Africa! Manatees mainly eat plants, but the African species has also been seen eating fish and mollusks (clams and mussels). This is learned behaviour, however, as they don’t catch fish themselves, but take them from fishing nets.

WHY THE AFRICAN MANATEE IS ENDANGERED

Sadly, manatees are facing many threats –illegal hunting being the largest threat in Africa. Although it is illegal in every country where the species can be found, this is rarely enforced by the authorities. In Nigeria, for example, over a hundred manatees are killed by hunters every year. This is something Dr. Keith-Diagne and her Nigerian colleagues want to change to ensure that manatees don’t go extinct in Nigeria.

Another threat is accidental catching with fishing nets: when manatees are caught in fishing nets, they’re not released but get eaten instead. Dams are also a threat to this species, as they get crushed in dam structures or trapped behind dams. If there are rice fields near rivers, manatees can get into rice fields and often end up being killed for damaging these fields. Finally, there are also conflicts between people and manatees. For example, the African manatee eats fish that they take from fishing nets. This causes conflict with fishermen, who kill them in retaliation.

HOW THE AACF IS HELPING MANATEES

Manatees face a lot of challenges, but the AACF is trying to find peaceful solutions for both humans and wildlife. Dr. Keith-Diagne spends time meeting with governments and wildlife agencies who have the task of enforcing the laws to protect the species in order to try to encourage them to protect manatees. In the past, some of these agencies asked Dr. KeithDiagne to prove to them how many manatees were being killed, so she developed a study in five countries to document every manatee that dies from a human cause. This study includes nine African colleagues who work in the different countries, and they have discovered that the threats are quite different in each country. In Nigeria, for example, illegal hunting is the largest threat, but in Senegal it is bycatch in fisheries and mortality in dams. Dr. Keith-Diagne documented dam structures that caused fatalities and worked with the dam management authorities to bring changes to these structures so that manatees will no longer be killed. Knowing what the largest threats are in each country helps the team know where to target their energy to reduce them.

44 SENEGAL

“Manatees are facing many threats – illegal hunting being the largest threat in Africa. ”

Photo Credits: Tomas Diagne / AACF

Photo Credits: Tomas Diagne / AACF

An example of a manatee net in Angola.

Photo Credits: Lucy Keith-Diagne / AACF

Photo Credits: Lucy Keith-Diagne / AACF

Photo Credits: Lucy Keith-Diagne / AACF

Photo Courtesy of the Senegal River Basin Authority

Photo Credits: Lucy Keith-Diagne / AACF

Photo Credits: Lucy Keith-Diagne / AACF

Photo Credits: Lucy Keith-Diagne / AACF

Photo Courtesy of the Senegal River Basin Authority

Photo Credits: Lucy Keith-Diagne / AACF

Whenever Dr. Keith-Diagne and her colleagues gain information on areas where there is hunting, they share it with wildlife authorities. However, getting them to do something about it is slow going. Their goal is to work with these authorities to make arrests and publicize them in the media. They believe this would make poachers think twice before killing the species.

There is hope, however. Dr. Keith-Diagne and her colleagues are raising awareness about the protected status of manatees and have seen the first dam in Senegal altered so that it no longer kills manatees. They also hope to work with The Eagle Network, an organization that works with government wildlife agencies to stop illegal killing and trade of protected species.

EDUCATING LOCAL COMMUNITIES

Apart from this, the AACF also organizes educational programs to make people aware of the fact that manatees are a protected species and should not be killed. They have programs in primary and secondary schools in Senegal that reach up to 4000 kids per year. Since 2008, Dr. Keith-Diagne has led training programs for biologists from 17 different African countries, to teach them African manatee research and conservation techniques. Her current two-year long training program for 13 biologists in Guinea is her 14th training program. Dr. Keith-Diagne has partnerships with local communities too; she has trained local partners in Senegal how to take samples from dead manatees that help us understand their life cycle and to rescue manatees from fishing nets or from behind dams they’re trapped behind.

Dr. Keith-Diagne and her research partner

Dr. Dunsin Bolaji also worked on a successful aquaculture project in Nigeria in the past, where they offered to train communities in catfish agriculture while providing them with the necessary equipment on one condition: the hunters had to agree to get rid of their manatee traps and promise not to make more traps.

At first, the hunters weren’t very interested, but a few of them accepted the deal. These people became very successful and started making more money through catfish agriculture than they did by killing manatees, as catfish agriculture is much more predictable than waiting for the occasional manatee to enter their traps. When the remaining manatee hunters saw that, more and more started to join the program. They got rid of their manatee traps and went from killing 131 manatees a year to zero. Unfortunately, although other communities wanted to join this program too, the project ended when the initial funding was finished, but they hope to restart it again in the future. It is, however, a beautiful example of a very successful collaboration.

THE FUTURE OF THIS SPECIES

The African manatee is categorized as Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, but Dr. Keith-Diagne and her team are determined to find solutions so that manatees and humans can peacefully coexist so that populations can thrive. The species is an important part of the ecosystem, as their feces nourish juvenile fish, leading to more fish when manatees are present.

Right now, the team is working hard to gather more information about the species’ numbers and populations so that they can define which sub-populations are more vulnerable. This is important research as it will teach us where the most threatened populations are and where the species is thriving, so that threats can be mitigated effectively. Dr. Keith-Diagne has also recently recorded the first vocalizations of manatees in Senegal which will help her better understand manatee habitat use, she continues her study of African manatee food resources throughout the countries she works in, and she is mentoring four graduate students studying manatees in Senegal, Nigeria and Cameroon.

49 SENEGAL

At Ubuntu Magazine, we think it’s important to spread the word and give a platform to beautiful projects like the AACF. Thanks to them, hundreds of African manatees are saved every year.

Make sure to check out their website and socials if you want to learn more about this organization.

Instagram

@africanaquaticcf

Facebook

@AfricanAquaticConsFund

Website

www.africanaquaticconservation.org

50

SENEGAL

51 The West Indian manatee.

COMBINING SCIENCE AND CONSERVATION OF MANGROVE FORESTS

The coasts of the tropics are covered in forests unlike any other on earth: mangrove forests. These forests are vital for the stability of coastlines, the health of marine life, and for the well-being of local communities. They are even crucial in the fight against climate change. Yet these unique forests are one of the most threatened habitats on the planet. Despite this, they remain relatively understudied.

In this article, we talk to Martin Zimmer and Véronique Helfer, two of the leading mangrove ecologists at the Leibniz Centre for Tropical Marine Research (ZMT), who have taken their research a step further to better help these imperiled ecosystems.

52 WORLDWIDE

53

Photo Credits: Callum Evans

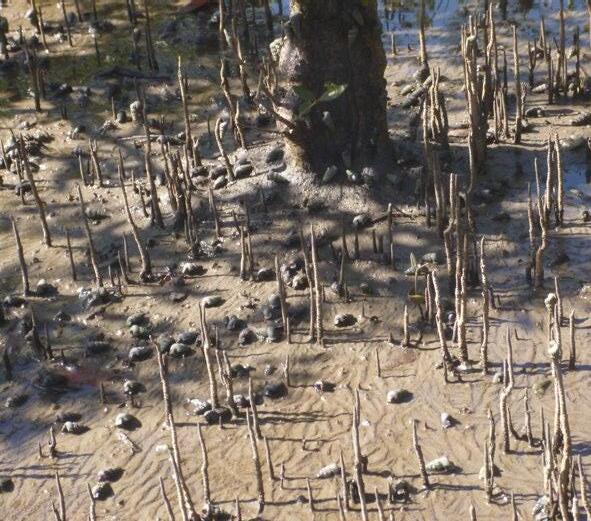

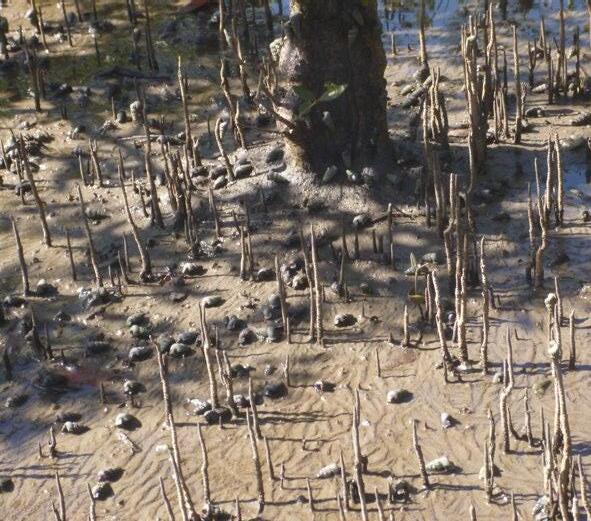

Mangrove forests are a truly unique habitat. They are found in many of the world’s tropical and subtropical coasts, from Southern Australia to Northern Florida, forming a transition zone between land and sea. Worldwide, you can find about 80 different mangrove species. What makes mangrove trees recognizable to many is their tangled prop root systems. These root systems, which make the trees look like they’re standing on stilts, are an adaptation to help the trees cope with the changing tides. When the tide goes out, these roots are exposed to the receding water helping the tree take in oxygen. However, the type of roots and their specific tide adaptations differ per mangrove species. In addition to coping with daily flooding, mangrove trees also have to cope with nutrient and oxygen-poor sediments and high levels of salinity. Surviving in such an environment requires the best adaptations possible.

The importance of mangrove forests cannot be overstated, not just in ecological terms but also in terms of climate change mitigation and the socioeconomic needs of local communities. The roots of the mangroves slow incoming waves, allowing sediments to be deposited around them. This helps build up the coastline and prevent erosion. These sediments also contain large amounts of carbon that will be stored upon deposition, adding to the amount that the trees themselves sequester and store in their biomass, thereby also helping in the fight against climate change. The combination of this sediment trap and the productivity of these ecosystems, renders mangrove forests among the most efficient carbon sinks. In fact, they are the most effective at absorbing carbon on a unitarea basis (even more so than rainforests, though mangrove forests lack the large-scale impact that rainforests have). This makes understanding the science behind mangrove forests crucially important.

54

They also offer coastlines protection against storms, which helps protect communities living around the mangroves. They provide a safe nursery for many species of fish, including a number of shark species, whose juveniles hide among the tangled roots and narrow channels to avoid larger predators. These nurseries also help to preserve the livelihoods of local fisheries. Mangrove forests are a very important habitat for land-based animals as well as marine life. In mangrove ecosystems, animals from both worlds live side-by-side. In the Sundarbans (the world’s largest mangrove area that extends from India into Bangladesh), Bengal tigers swim across the same rivers that are home to the Ganges River Dolphin. In Gabon, red-capped mangabeys clamber through the tangled maze of branches

while hippos and crocodiles swim in the estuaries. Nothing like this can be seen in any other habitat on Earth.

Considering their importance, mangroves are a habitat that we cannot afford to lose. And yet they are one of the most threatened ecosystems on earth. Although the rate at which mangroves are being lost has decreased drastically in recent years, they are still more threatened than rainforests. The biggest threats come from clearcutting (deforestation) and pollution. Various types of pollution can also impact mangroves, including the physical and chemical impacts of plastic pollution, organic pollution from sewer runoff, chemical pollution from factories, and eutrophication, which is primarily caused by aquaculture ponds.

55

WORLDWIDE

Mangrove stand with high density of snails.

Photo Credits: Martin Zimmer and Véronique Helfer

Aquaculture ponds are also one of the reasons behind the clear-cutting of mangrove forests, as trees are cut down to make way for the ponds in which shrimp, fish, and crabs are cultivated and grown for food. Unfortunately, after 8 - 12 years the ponds aren’t productive anymore and so more ponds keep needing to be constructed (almost like slash-and-burn agriculture). The ponds also change the topography of coastal areas so much that mangroves cannot recolonize these areas by natural means. Integrated mangrove aquaculture, where mangrove trees grow in and amongst the ponds to improve their productivity and longevity, should become the reference if we want to ensure a more sustainable food production.

The Leibniz Centre for Tropical Marine Research (ZMT) is a scientific institute based in Bremen, Germany, that investigates tropical and subtropical coastal and marine ecosystems, with a key focus being their importance to both humans and nature. Their researchers work in partnership with scientists and local stakeholders in various countries, with the aim to ensure the protection and sustainable use of natural resources in these ecosystems, notably coastal vegetated ecosystems (including mangroves) or coral reefs. Both Martin Zimmer and Véronique Helfer work at ZMT, specifically in the Mangrove Ecology Group. By working to understand the ecology of mangrove ecosystems and their effects on people and the climate, as well as the potential impacts of pollution and other threats, they can help to create a basis for the sustainable use and management of mangroves on a global level.

56

WORLDWIDE

“Our aim is to restore an area with as many trees as needed and as possible.”

57

Photo Credits: Jonas Geburzi

Véronique describes working at ZMT as being incredibly rewarding. Not only is she excited by the research she is doing, but crucially that research is also making a meaningful difference to society. Martin reiterates this by saying: “What we are doing is relevant to society because we are doing it for society.” A prime example of this concept is that the research that Martin and Véronique do within ZMT then feeds into the work they carry out with their not-for-profit organization, fairGROVE UG.

fairGROVE UG works with both local partners and investors, providing a vital link between the two parties. It aims at finding investors to financially support mangrove conservation and afforestation that is carried out by local NGOs, that are partners with fairGROVE, and the development of ideas and models for the sustainable use of products derived from mangroves. Whatever

profits fairGROVE makes is then reinvested into local projects that will benefit people and their communities, or into research projects relevant to sustainable mangrove management. As Martin states, they are “investing in the science” so as to make a difference and take action.

Martin and Véronique state that there are two main pillars to fairGROVE. The first is afforestation, along with reforestation, of mangrove forests.

Afforestation involves identifying new areas that are suitable for mangrove forests (not necessarily areas where they were growing before) and implementing new forests in these areas. By doing this, the range of the forests is expanded. Afforestation of mangroves can be done in a way that local communities are able to benefit from it. This can be described as ecosystem codesign, whereby people plant the species that are best at providing the ecosystem services that the people living in that area need the most, whether that be coastal protection or food provision. An example of eco-system co-design could also be the creation of ecologically sustainable aquaculture ponds, with mangrove trees being left to grow around the ponds or otherwise be planted around the ponds (as mentioned above). The second pillar is the sustainable use of products derived from mangroves. This pillar is specifically aimed at empowering women from local communities surrounding mangrove forests (helping to develop some independence if they so choose) and helping people develop alternative livelihoods.

58

WORLDWIDE

“The more we grow, the more impact we can have.”

For such an important habitat, there is still so much we don’t know. This mystery that still surrounds these forests is part of what draws in scientists like Martin and Véronique. Martin describes the mangrove forests as “mystic”, in the sense that the misty mornings and the sounds in the air create “a feeling there that is magical.” Martin noted that this was an emotional description but as he rightly pointed out “We are humans so we’re allowed to be emotional.” Mangrove forests, like many places on this planet, have the ability to draw people in with their unique beauty, amazing biodiversity, and simply with just their extraordinary existence. Surely you cannot truly save something without getting emotional about it.

59 Website www.leibniz-zmt.de/en

60

SEA SHEPHERD’S FIGHT AGAINST ILLEGAL FISHING IN AFRICA

Protecting ecosystems and keystone species is vital for the survival of ocean wildlife. All species are connected, as they are dependent on one another to survive and thrive – from the tiniest phytoplankton in the world to the largest mammal alive, the blue whale. We as humans can have a massive impact on ecosystems and the complex web of species within them. Fishing, especially when unregulated, can have a large-scale impact.

Even if we don’t see it directly, there is a connection between the world of illegal fishing and the whales roaming the oceans. While Peter Hammarstedt, Director of Campaigns of Sea Shepherd, once started his volunteering years to combat whaling in Antarctica, he is now focused on illegal fishing in African waters making a greater impact than ever before. This is his story, and the story about Sea Shepherd’s mission to combat illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing and fisheries crimes in Africa.

61

The African waters are known for their rich diversity and high abundance of fish. It is therefore no surprise that many countries take their fleet to the Atlantic Ocean to reach their fishing quota in time. Unfortunately, unregulated and illegal fishing is carried out on a large scale. Many vessels fish without the right paperwork, whilst also trespassing borders and breaking national laws. With the African Campaigns, Sea Shepherd has been supporting several African countries in combating this IUU fishing. But, how does it work?

Unlike many other conservation organizations, Sea Shepherd works in the field of Conservation Law Enforcement. Peter explains to us: “We partner with governments that have the political will to stop IUU fishing, but who have stretched economic resources. They might not have vessels to control and patrol their waters. So Sea Shepherd provides the ship, crew, and fuel for the ship, while our government partner provides the law enforcement such as coast guard personnel, fishery inspectors, or rangers. These are the people with the authority to board, inspect and arrest vessels.” He also adds, “our general mission is to stop illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing, to stop destructive fishing, and to protect endangered species. Supporting African governments in tackling IUU fishing is the first step to achieving this.”

Strategically it is logical for Sea Shepherd to tackle this first, as law enforcement is already on their side. Besides that, it is estimated that IUU fishing is responsible for 20% of global fisheries, so taking this approach enables them to create a large impact in a relatively efficient way. Tackling destructive fishing can be a more difficult task, as these fishing methods are oftentimes not illegal – and these vessels can therefore not be arrested solely for fishing destructively. He recalls a patrol in Gabon about a year ago, “We boarded a shrimp trawler that was legally licensed to fish there. However, when the net came up on deck, only 0.2% of their entire catch was shrimp. The other 99.8% were other marine creatures of whom almost all were thrown overboard dead. It was a visual scenery for me as they were killing tens of thousands of sea creatures to create one shrimp cocktail. It was a clear example of destructive fishing, but we couldn’t do anything about it. Ultimately, it was determined that this vessel had been fishing with an illegal net – its mesh size was too small – so it was arrested. But had it not been for the boarding and inspection at sea, the authorities would have never known about it.” This case is a great example of how boarding and inspecting legally licensed vessels can still be effective when fighting illegal fishing.

62

Currently, already eight country partners cooperate with Sea Shepherd to do these patrols, all on the African continent. “With these eight partnering countries, we have already assisted with the arrest of 84 vessels for illegal fishing and other fisheries crimes. Every day that one of these vessels stays stuck in court is tens of thousands of sea creatures saved – from shrimps to whales,” says Peter. So, although this is the mere beginning

Besides that, it has been wonderful to see the Rogues Gallery – a list of all the arrested vessels – come to life with the help and accordance of all these partnering countries. The Rogues Gallery acts as a database for fishery agencies across the world, in order for them to look up arrested and suspicious vessels. Besides that, it showcases Sea Shepherd’s success, but more importantly, it helps a greater cause as it contributes to the United Nations Agreement on Port State Measures. This agreement targets IUU fishing by preventing previously arrested vessels from using ports and landing their catches. It has been a true improvement already, says Peter, as a number of countries outside the African campaigns have already reached out to gather additional information. Logically, all necessary details are then provided so that organizations, ministries, or fishery agencies can get in touch with each other.

With the campaign clearly being successful, it would be logical to start collaborations with other countries as well. Although this expansion is already in progress, it has to be noted that Sea Shepherd’s fleet is not endless. Their new approach, which is still a work in progress, tackles this.

of all the work that can be done in African waters, there have already been great results. A remarkable thing within the African Campaigns is the individuality within each country in terms of marketing and promotion. All national campaigns have their own name as well as their own logo, which has shown to be very successful in recent years. By using them, each and every country has a way to promote the operation nationally, including towards their citizenry. Logos usually consist of colors of national flags, names of partners, and the operation title itself. Peter’s words showcase that he is proud of Sea Shepherd’s campaign: “I think it is extremely inspiring that this international leadership comes from African countries. And it is these countries that are taking control of their own waters, and it is these countries that are leading on conservation initiatives.”

63

“I think it is extremely inspiring that this international leadership comes from African countries. And it is these countries that are taking control of their own waters and it is these countries that are leading on conservation initiatives.”

AFRICA

64

65

66

Peter explains to us, “First of all, there has been an ongoing trend in reshaping our approach from national to regional. For example, we now have patrols in Gabon in which we also include law enforcement from São Tome and Principe. That allows the ship to control a larger stretch of water, instead of being restricted to certain national coastal waters. Additionally, most of these countries do not have suitable vessels today, but they might have them in the near future. Our ships are a training platform where people from law enforcement learn what to do and how to do it so that once they acquire their own ship, they have years of experience on a similar-sized vessel.”

Besides that, it is good to notice that ships are not needed full-time. Some operations, like Operation Albacore in Gabon, are seasonal. Operation Albacore is mainly focused on the tuna fishery and as tuna migrates, they are only present in Gabon’s waters between June and September, so patrolling is only needed during those months. Additionally, there is a tactic element to leaving a country to itself for a while. When you return to waters where you haven’t patrolled in a while you create the element of surprise. By coming and going irregularly, vessels will never know if they have a chance to be arrested, so they will most likely stay away. Although this also includes the possibility that they will go elsewhere, it is good to know that the ecosystem at stake gets the chance to recover.

Looking at the scope of Sea Shepherd’s work, including Peter’s lifelong dedication to the organization, there is no doubt that one day, illegal fishing in African waters will be a thing of the past. Nevertheless, a lot has changed in 20 years’ time. After dedicating more than half of his life to the world’s oceans, he has seen a lot. Peter adds: “It is not easy to see the oceans becoming depleted over time. You can visually see the difference in biodiversity. I feel lucky to stand on ships where I know I can take action to make a difference, instead of simply watching the destruction from a vessel passing by. So while it can be dispiriting on the one hand, it can be invigorating and encouraging on the other hand. With Sea Shepherd, I have the possibility to shut down illegal fishing on the spot.”

He continues, “Within conservation in general it can oftentimes be difficult to see what the impact of your work is. You go up against the industrial space and people’s consumer lifestyle choices. It feels so daunting sometimes. Although a longterm goal will get you to where you want to be, you also need a short-term goal like ‘we’re going to end illegal fishing in Liberia’ to keep the momentum going. If we’re able to achieve just one short-term goal in a lifetime, it is pretty darn good. If we just focus on the big picture all the time, it doesn’t allow our activism to be sustainable.”

67

AFRICA

“If we just focus on the big picture all the time, it doesn’t allow our activism to be sustainable.”

Peter’s story, which started when he was fourteen years old, was initiated by an image of a whaling ship where a whale was pulled up by its tail. Eight years after seeing that image for the first time, he saw the vessel in real life during a campaign. After that, it took ten years of chasing them until they suspended their whaling program. The moment the fleet ceased its activities Peter himself was in New Zealand. His memories of that moment are extremely vivid, as he recalls: “I was on an ecotourism boat in Milford Sound when the captain of the ship stopped the engine to turn on the radio. Everyone was cheering and celebrating the good news, as was I. To me, it was a beautiful place to receive the news. The waters which had been hunted for so long had now become just as calm and peaceful as the fjord I was currently in.” This might be just one example of how seeing one single picture evolved into a successful chase and shutdown of a whaling ship, but it proves that having achievable short-term goals can make a large impact and keep your motivation high at the same time.

Nevertheless, Peters’ career shifted from the whaling industry to the illegal fishing industry right after that victory. And although that seems like a big, unexpected shift, he is now exactly in the place he wants to be. By fighting overfishing, destructive fishing, and illegal fishing, Peter is now able to save many more whales and other sea creatures than ever before. By stopping IUU fishing in Africa he is protecting entire ecosystems, including its fish, whales, and turtles. As you can see, there are hidden connections everywhere; in ecosystems and in the ways humans interact with them.

What the future beholds for Peter is yet unknown, but according to him, he has no intentions of doing anything else soon. “What else could be more rewarding than saving thousands of animals every day?”

Instagram

@seashepherd

Facebook

@seashepherdglobal

Website

www.seashepherdglobal.org

Linkedin

@seashepherdconservationsociety

68

AFRICA

69

70

STARGAZER WESSEL VEENBRINK

Uncovering the hidden world of wildlife

71

72 Instagram @wesveenbrink_photography

73

PHOTOGRAPHY AND CONSERVATION

I’m a 22 year old Applied Ecology Masters student, currently living in Norway. Through my photography, I try to portray the beauty of our natural world. My main focus is the aspects of nature that are mostly invisible to other people. As most of my studies revolve around nature conservation, wildlife management, and the human-wildlife relationship, I am able to include photography in my ecological research. Through my imagery, I try to inform people about the importance of nature conservation.

I have grown up spending a lot of time in nature, and from the moment I held my first camera – around the age of 12 – I have focused on nature photography. I am a self-taught photographer, so it has taken years to learn how to use a camera, take better images, and build my portfolio. To me, a good photograph tells a story, sometimes in a bigger series, sometimes on its own, and sometimes it is up to the viewer to imagine the story. Now that I am more confident as a photographer, I can start telling those stories. Through my studies, I am able to come close to wildlife, which enables me to showcase their beauty as well as the problems they are facing. To me, that is how photography can be a very powerful tool in conservation ecology.”

74

E-mail wesselveenbrink@hotmail.com Website www.wesselveenbrink.wordpress.com Instagram @wesveenbrink_photography

75

76 Instagram @wesveenbrink_photography

77

78

UNDER THE SKIN

It is 2015 when brothers Ed and James Harrison go skiing together. After days of descending the slopes, some rest is much needed. Soon, the conversation develops into talking about both their creative endeavors to merging their passions and skills to make an impact in conservation. Within hours, the business idea unravels itself and the two brothers find themselves eager to go back home, to get their new-found project underway.

79

Photo by Alex Sedgmond

ED, JAMES, THANK YOU FOR TAKING THE TIME TODAY. LET’S START OFF WITH AN INTRODUCTION, SHALL WE? CAN YOU INTRODUCE YOURSELF AND YOUR PROJECT UNDER THE SKIN?

Ed: Hi, I’m Ed Harrison, co-founder of Under the Skin. I’m a designer and illustrator.

James: Hi, I’m James Harrison, the other cofounder. I’m a designer and the printmaker of the team. Under the Skin is our company in which we make interactive screenprints to help save endangered species.

Ed: Everything we do – from a brand perspective – is in line with the artwork and the initial idea. We create the animal in a simple, playful, and illustrative way. Beneath that you can see the more complex, intricate skeleton which visually communicates the heavier and more serious underlying topic of species extinction. By using bold shapes and bright colors we are able to celebrate nature without putting too much attention on the underlying thought – without denying it either. So even though we keep it playful and fun, we are able to share the full story

of these endangered animals through our unique way of printing.

THAT SOUNDS GREAT. WE WANT TO KNOW ALL ABOUT IT. HOW DID YOU GET STARTED?

Ed: We grew up in the outdoors in South Wales, so ever since we – my three brothers and I – were young, we would go into nature. We love skiing, rock climbing, and surfing, so we got to spend a lot of time outdoors. During those years of being outside, however, we experienced some of the negative impacts on the natural world. We witnessed a rise in ocean plastic while surfing and noticed the warming weather patterns while going skiing year after year. This really got us thinking about the environment, climate change, and species extinction.

James: It was our skiing trip in 2015 when things fell into place. Ed had been working in the corporate world of graphic design and branding, while I had built up experience in the print studio. When we were talking during that ski trip, we had the idea to create a series of illustrations about endangered species. At that time, I was experimenting a lot with interactive inks, and I came up with the idea to incorporate that into the designs. And here we are now.

80

Photo Credit: Alex Sedgmond

CAN YOU TELL US MORE ABOUT THE INTERACTIVE INK AND WHAT IT ADDS TO YOUR PRINTS?

James: Yes, so what we do is we use phosphorescent ink – which cannot be seen in normal daylight – to add an extra layer to our print. After creating the animal illustration, which Ed will tell you about, we add a final hidden layer in the shape of the species’ anatomically correct skeleton. We want to highlight the fact that only the skeleton will remain after they go extinct.

Ed: Just like the skeletons which you can see on display at the Natural History Museum.

James: Exactly. So, you can’t see the skeleton unless you shine a UV light onto your print.

SO ED, JUST TO DIVE INTO PRINTMAKING, HOW DOES IT WORK?

Ed: Simply said, we make the prints layerby-layer, color-by-color. The illustrations are very geometric, precise, and clean, so it is very technical and a lengthy process in itself.

James: We go back and forth with the process. Ed starts in a sketchbook, he then sends it to me to digitize it and to separate the layers of the design, and then I begin the screen printing process. It goes from handmade to digital to handmade, and that process of working together produces really interesting results. The fact that Ed’s illustrations are so neat and precise has really honed my skills in screen printing.

Ed: And we should not forget the fact that even before we put a pen to paper, we do a lot of research about each species and its habitat. James often researches the biological and evolutional aspects of species, while I dive into the anatomy. For example, I look a lot at the different postures of the animals, because we want to capture the iconic characteristics of the species in each illustration. We always select a bright, playful background color based on the habitat in which the species lives.

81

Photo Credit: Gabriella Jackson

WORLDWIDE

82

83

Photo Credit: Alex Sedgmond

ALL THAT RESEARCH THAT YOU DO BEFOREHAND GOES INTO THE DESIGN, WHICH IS VERY INTRIGUING. DOES THIS INFORMATION ALSO REACH THE CUSTOMER WHO BUYS THE PRINT?

Ed: Yes, it does. First of all, we include a leaflet within the package that visualizes information about the species and the threats it faces. In this leaflet, we also include information about the charity which works specifically on that species to inform the customer about what they do –and about what happens with their money as 20 percent of our proceeds go directly to that charity.

James: It is important to us to carefully research and learn about each animal. We want to know where they live, which threats they face, and why they are in decline. But over time, for every species we illustrate, we have found it can become quite heavy and overwhelming.

They say “action is the antidote to despair.” Without having Under the Skin as an outlet for this information, I would find it difficult to sit down to delve into all of this information. So being able to translate these negatives into something positive and impactful to digest feels meaningful to me. Under the Skin makes it all worth it.

As artists we have the opportunity to learn about each animal, the threats they face, process it and then visualize it in a simple and easy way for people to understand.

When we have an exhibition we also try to educate the people by adding infographics alongside our prints. When People will look at the artwork and reveal the skeletons we can see their reactions as they realize “Wow, these species won’t be around for much longer unless something is done about it soon.” There is a lot of “show and don’t tell” in our work. We don’t tell them directly, but let them figure it out when they see our artwork.

84

“Wow, these species won’t be aroundfor much longer unless something is done about it soon.”

Photo Credit: Ed Harrison

WORLDWIDE

IT IS CLEAR THAT YOUR IMPACT ON THE PLANET IS VERY IMPORTANT TO YOU. DOES THAT COME BACK IN THE PRINTING PROCESS ITSELF AS WELL?

Ed: We create everything as environmentally positive as possible. We print on carbon-neutral paper and we only work with water-based inks. We want to have longevity in what we do, so everything has to be either biobased, recycled, or recyclable.

WITH ALL THE KNOWLEDGE THAT YOU GAINED ABOUT THE ENVIRONMENT, CLIMATE CHANGE, AND SPECIES EXTINCTION, DID YOU CHANGE THINGS IN YOUR PERSONAL LIVES AS WELL?

James: We are both vegan, which I think is one of the biggest things you can do to have a positive impact on the planet. Everything that we do with Under the Skin feeds back into our own lives, from avoiding single-use plastics to sourcing local organic food.