CONNECTING ALUMNI, FRIENDS AND COMMUNITY

JACOBS SCHOOL OF MEDICINE AND BIOMEDICAL SCIENCES UNIVERSITY AT BUFFALO

CONNECTING ALUMNI, FRIENDS AND COMMUNITY

JACOBS SCHOOL OF MEDICINE AND BIOMEDICAL SCIENCES UNIVERSITY AT BUFFALO

At the Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences at the University at Buffalo, our mission is clear: transforming ideas into impact, advancing science, improving health and strengthening the well-being of Western New York and beyond. We know that lasting change happens through collaboration, and we’re proud to work in partnership with our community to drive progress.

In this edition of UB Medicine, we highlight how our faculty, learners and partners are bringing that mission to life in powerful ways. Our research enterprise isn’t just one component—it’s an entire ecosystem where basic science research, clinical trials and our facilities come together to create a robust environment for discovery. This interconnected approach is what allows us to translate scientific breakthroughs into real-world solutions that make a difference in our region.

This seamless pipeline is fueled by strategic investments in our people and infrastructure. You’ll read how our new facilities are more than just bricks and mortar; they are engines of innovation that support our full research enterprise.

We are equally committed to cultivating the next generation of scientific leaders, investing in STEM-focused outreach and providing strong support for junior faculty. This momentum is reflected in our enrollment growth in undergraduate and master’s programs, learners who are choosing UB as the place to begin their journey in science and medicine.

From foundational science to the bedside, we are translating discovery into action. These efforts underscore UB’s leadership in population-focused innovation and our commitment to improving lives through research that moves from bench to bedside.

As we implement Epic—the most widely adopted electronic health record system—across our clinical sites, we’re opening new doors to accelerate research, improve care and expand our impact. This is a transformative moment for UB and for the patients and for the people we serve.

Together with our learners, faculty, and partners, we are shaping a future defined by innovation, compassion and progress. Thank you for being part of our story.

With pride and gratitude,

Allison Brashear, MD, MBA

Dean, Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences Vice President for Health Sciences President and CEO, UBMD Physicians’ Group

UB Medicine is published by the Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences at UB to inform alumni, friends and community about the school’s pivotal role in medical education, research and advanced patient care in Buffalo, Western New York and beyond.

VISIT US: medicine.buffalo.edu/alumni COVER IMAGE

A look at the many different aspects of the Jacobs School research enterprise.

Photo illustration/Cover design: Ellen Stay

Medical schools, community organizations and local leaders join forces to confront a public health crisis

How the Jacobs School’s research enterprise enables discovery and enriches health

ALLISON BRASHEAR, MD, MBA

Vice President for Health Sciences and Dean, Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences

President and CEO, UBMD Physicians’ Group

Jeffry Comanici

Assistant Vice President for Advancement

Editor Patrick S. Broadwater

Contributing Writers

Dawn M. Cwierley

Keith Gillogly

Ellen Goldbaum

Dirk Hoffman

Copyeditor

Ann Whitcher Gentzke

Photography

Sandra Kicman

Meredith Forrest Kulwicki

Douglas Levere

Nancy Parisi

KC Kratt

Art Direction & Design

Ellen Stay

Editorial Adviser

John J. Bodkin II, MD ’76

Affiliated Teaching Hospitals

Erie County Medical Center

Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center

Veterans Affairs Western New York Healthcare System

Kaleida Health

Buffalo General Medical Center

Gates Vascular Institute

John R. Oishei Children’s Hospital Millard Fillmore Suburban Hospital

Catholic Health

Mercy Hospital of Buffalo Sisters of Charity Hospital

Correspondence, including requests to be added to or removed from the mailing list, should be sent to: Editor, UB Medicine, 955 Main Street, Buffalo, NY 14203; or email ubmedicine-news@buffalo.edu

Student numbers rise across undergraduate, master’s and PhD programs

A select collection of images from events happening at the Jacobs School over the past few months.

The Jacobs School had a large presence at this year’s Juneteenth parade and celebration events at Martin Luther King Jr. Park. Buffalo boasts one of the largest and oldest Juneteenth festivals in the nation.

Jian Feng, PhD, SUNY Distinguished Professor of physiology and biophysics, delivers the 2025 Stockton Kimball Lecture in the Dozoretz Auditorium. The lecture is paired with the school’s faculty and staff recognition awards ceremony each May, marking one of the final events of the academic year. Steven J. Fliesler, PhD, SUNY Distinguished Professor and Meyer H. Riwchun Endowed Chair Professor of ophthalmology, was named this year’s winner of the Stockton Kimball Award for outstanding scientific achievement and service.

Joy filled the air at the University at Buffalo’s Center for the Arts as incoming medical students donned their white coats for the first time. The event, held at the conclusion of orientation week in July, marked the ceremonial beginning of their medical careers for more than 180 new first-year medical students.

Jacobs School graduates of 2024 are a year removed from med school, but they’re still scoring high marks. According to the AAMC Resident Readiness Survey, 98.1 percent of Jacobs School alumni from the Class of 2024 are meeting or exceeding the overall expectations of their residency program. Scoring well on residency reviews is nothing new to Jacobs School graduates—our alumni consistently meet or exceed expectations at a high level, year after year—but the 98 percent mark is the school’s best result over the past five years.

As part of orientation week, Jacobs School medical students and faculty assisted local agencies with service projects across the city of Buffalo and Western New York. The projects not only helped out local nonprofits and service organizations, but the community engagement of our students is a built-in feature of the school’s new Well Beyond curriculum.

The University at Buffalo’s new Genetic Counseling Graduate Program has received accreditation from the Accreditation Council for Genetic Counseling (ACGC), the field’s national accrediting organization.

The two-year Master of Science program, which will be administered by the Office of Biomedical Education in the Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences at UB, will prepare students to become board-certified genetic counselors who help patients understand genetic risks and guide decision-making.

Applications to the program opened Aug. 1 and will run through Dec. 15. More information can be found at medicine. buffalo.edu/education/genetic-counseling.

The program has already received approvals from SUNY and the New York State Education Department. With the program’s start in fall 2026, UB will be the first public university in New York State to offer a master’s in genetic counseling.

“All patients in Western New York should have access to the health benefits of genetic and genomic medicine,” says Lindsey M. Alico, a board-certified genetic counselor and director of UB’s Genetic Counseling Graduate Program. The Orchard Park native joined UB in 2023 from Sarah Lawrence College, where she previously co-directed its genetic counseling program, the nation’s oldest and largest.

Laurie S. Sadler, MD, clinical associate professor of pediatrics and a clinical geneticist in Buffalo for over 30 years, is the UB program’s first medical director.

Genetic counselors don’t directly diagnose conditions or prescribe therapies. They instead offer guidance and information about inherited diseases that may affect patients and their families.

Genetic counselors help patients and providers understand the clinical implications of complex genetic test results in order to make more informed health care decisions. Expectant parents may see a genetic counselor after an abnormal

carrier screening test or ultrasound. Patients may also be referred to a genetic counselor to determine if a recently diagnosed disease has a genetic component.

“Sometimes we see someone who’s been diagnosed with cancer and has an unusual feature, like a rare type of cancer or diagnosis at a young age, and they want to know the chance that it was due to a hereditary cause,” says Alico, clinical assistant professor in the Jacobs School’s Office of Biomedical Education.

Most health care providers have received little genetics training while in school and would benefit from more support in genetic-related care, Alico says. While telehealth has improved access to genetic counselors, there’s demand for more counselors, both locally and nationally.

The idea for creating a genetic counseling degree program coincided with the 2015 launch of UB’s Genome, Environment and Microbiome Community of Excellence, or GEM, which promotes genetics, genomics and microbiome research and outreach to advance understanding of personal health issues. Jennifer A. Surtees, PhD, now the chair of the Department of Biochemistry, is GEM’s co-director and spearheaded the genetic counseling effort, shepherding the program through its curricular development and early approvals.

She worked closely with Carolyn Farrell, PhD, who directed the Clinical Genetics Service at Roswell Park

Comprehensive Cancer Center for over 15 years, and with Norma J. Nowak, PhD, professor of biochemistry and codirector of GEM.

Throughout the development process, Surtees says it was key to involve faculty from many schools—including medicine, nursing, public health, pharmacy, law, social work, education, and arts and sciences—to garner their

perspectives on genetics.

She adds that the launch of the program is a return to the region’s historical contributions to genetic and genomic research, noting UB researchers’ involvement with the Human Genome Project and achievements in neo-natal testing for PKU and for sickle cell anemia.

Applicants to genetic counseling programs participate in an admissions match overseen by the Genetic Counselor Educators Association that places them into accredited programs. Interviews will take place during the spring semester, with the first student cohort beginning classes in fall 2026. UB’s program will enroll four students initially, Alico says, but will expand to include six students per class.

Students in the program will complete 61 credits from classes taken over 21 months. In addition to completing a master’s thesis, students must complete clinical rotations with certified genetic counselors. Surtees and Alico acknowledge the commitment local genetic counselors have made to developing the master’s program and to supervising and teaching students.

Program graduates will be able to sit for the American Board of Genetic Counseling certification exam to become a Certified Genetic Counselor, a required credential to practice in most areas.

In New York State, genetic counselors do not have licensure and therefore cannot operate independently; they must be embedded within an existing hospital or practice. Thirty-five other U.S. states, however, issue licenses for genetic counselors.

UB’s new genetic counseling program was developed by (left to right) Carolyn Farrell, Lindsey M. Alico, who directs the program, Jennifer A. Surtees, and Norma J. Nowak.

Jennifer A. Surtees, PhD, professor of biochemistry in the Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, has been named chair of the Department of Biochemistry, effective July 1.

“Recognized for her outstanding scientific leadership, collaborative spirit and remarkable ability to mentor and inspire, Dr. Surtees brings both scientific distinction and a genuine passion for education and community outreach to this leadership role,” says Allison Brashear, MD, MBA, UB’s vice president for health sciences and dean of the Jacobs School.

Surtees is both internationally recognized in the fields of genome stability and genetic diversity and a passionate advocate for boosting scientific literacy in the general population.

Surtees’ groundbreaking research explores how cells maintain the integrity of their genetic material, with a focus on DNA repair, replication fidelity and the regulation of nucleotide pools. Her lab investigates how disruptions in these processes contribute to cancer and neurodegenerative diseases. She is particularly wellknown for her work showing how research into altered levels of DNA building blocks may inform future cancer therapies.

“Dr. Surtees brings both scientific distinction and a genuine passion for education and community outreach to this leadership role.”

- Allison Brashear, MD, MBA

A UB faculty member since 2007, Surtees is a prolific scholar, having authored numerous peer-reviewed journal articles, book chapters and scholarly reviews. She is frequently an invited speaker at national and international scientific meetings.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, she launched collaborations with UB colleagues and the Erie County Public Health Laboratory to sequence SARS-CoV-2 genomes, helping to track variants and guide public health responses—work that continues as part of the New York State COVID Genomic Sequencing Consortium. This work was a catalyst for Surtees to assemble a broad, interdisciplinary team focused on pandemic prevention through novel environmental monitoring and building trust through community conversations and STEM outreach.

As co-director of the Genome, Environment and Microbiome (GEM) Community of Excellence, she has led efforts to develop and foster interdisciplinary research teams at UB and to promote genome and microbiome literacy at UB and in the Buffalo community, earning the Jacobs School’s Community Service Award for Excellence in Promoting Inclusion and Diversity.

Surtees earned her Bachelor of Science degree in genetics from Western University (Ontario), and her master’s and PhD in molecular and medical genetics from the University of Toronto.

Asim Khan, PhD, a nationally recognized expert in digital technologies and strategic health care information leader, has been named the University at Buffalo’s health sciences chief data and information officer, effective Sept. 2.

Khan joined UB from the Allegheny Health Network, where he served as system director of IT business intelligence and interoperability. He also serves as chief data and information officer for UBMD Physicians’ Group and as executive director of UB Information Technology HIPAA Compliance.

In his new roles, Khan works to create and implement a unified information technology strategy across UB’s health sciences and UBMD’s 17 practice plans. In order to enhance patient care, research and education, Khan focuses on driving digital transformation, improving data governance, and enabling information systems to work in unison.

Khan will oversee implementation of the Epic electronic medical record across UBMD and its practice plans, a key initiative to enable a unified electronic health record system across UBMD, Kaleida Health and the Erie County Medical Center.

He also leads the university’s information security team and the Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences’ Office of Medical Computing, working to align IT strategies with institutional goals and regulatory requirements.

“UB is uniquely positioned as a leader in technology, research and education, and I’m thrilled to direct a digital strategy that will help keep the university at the forefront of health sciences innovation,” Khan says.

Khan joined UB with more than 20 years of experience in health care information systems. At Allegheny Health Network, Khan directed enterprise-wide data and digital services.

His previous work has involved the development of clinical data repositories, advanced analytics and reporting systems, artificial intelligence (AI) automation in clinical workflows, and other large-scale digital health initiatives. His research interests include federated health care data governance, shared data platforms and AI.

Khan holds a PhD in computer and information science and has also received master’s degrees in information quality, project management, and engineering management, and a bachelor’s degree in electrical and electronics engineering. He is an alumnus of the University of Arkansas at Little Rock and George Washington University. Khan has served as adjunct faculty at Colorado State University Global and the University of Arkansas at Little Rock.

After a combined four decades guiding their respective departments, two longtime chairs step aside

James D. Reynolds, MD ’78, earned his undergrad and medical degrees from the University at Buffalo and returned to join the Jacobs School faculty in 1988. Nine years later, he would become chair of the school’s Department of Ophthalmology, a position he would hold for nearly three decades.

John E. Tomaszewski, MD, a Philadelphia native, built a distinguished 30-plus-year career at the University of Pennsylvania before moving to Buffalo to become chair of the Department of Pathology and Anatomical Sciences in 2011.

Their roads to leadership positions at the Jacobs School were certainly dissimilar, but upon their recent retirements as chair of their respective departments, they leave with a shared legacy of respect, admiration and success.

“We extend our deepest gratitude for the service of both Dr. Reynolds and Dr. Tomaszewski. Their decades of exceptional leadership and their contributions to their respective fields have had a profound impact on the Jacobs School and have shaped and inspired the journeys of countless students, researchers, faculty, and staff,” said Allison Brashear, MD, MBA, dean of the Jacobs School and vice president for health sciences at UB. “We wish them both all the best in their well-deserved retirements.”

A renowned pathologist, researcher, educator, mentor and friend to many, John E. Tomaszewski, MD, stepped down from his role as Peter A. Nickerson, PhD, Professor and Chair of the Department of Pathology and Anatomical Sciences on July 1. His extensive research career has illuminated translational genitourinary pathology and led to new quantitative image analysis tools for digital pathology and predictive modeling of disease and therapy response. A SUNY Distinguished Professor, he played a pivotal part establishing and running the region’s most extensive COVID-19 testing program during the pandemic. Known for his steadfast leadership, Tomaszewski will stay on as interim chair during the search for the department’s new leader.

Academic degrees: Doctor of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, 1977; Bachelor of Arts in biology, LaSalle College, 1973.

Publishing numbers: Peer-reviewed manuscripts: 346; book chapters: 25; abstracts: 71; reviews: 5; and editorials: 3.

Most meaningful awards: The David B.P. Goodman Award, University of Pennsylvania Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine Service and Citizenship Award, 2010; Mastership Award, American Society for Clinical Pathology, 2014; SUNY Distinguished Professor, 2017; Peter A. Nickerson, PhD, Professor and Chair, 2017; Gold Foundation Champions of Humanistic Care Award, 2021; Dean’s Award, Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, 2016 and 2025.

One piece of advice for aspiring physicianscientists: Find a big bunch of the very best mentors in your field and communicate with your mentors clearly and regularly.

Favorite UB memories: Planning and openings of the new downtown medical campus buildings, especially the new Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences at High and Main Streets. Being honored as the inaugural Peter A Nickerson, PhD, Professor and Chair of Pathology and Anatomical Sciences.

How you would like to be remembered by your UB colleagues: Fully committed to the missions of education, research and practice in pathology and laboratory medicine and in anatomy. Building a graduate (PhD and MS) program in computational cell biology, anatomy, and pathology. Establishing early and continuous laboratory testing for SARSCoV-2 in Western New York during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Best thing about Buffalo: The lakes and the falls. The generosity and kindness of the people of Buffalo. THE BILLS.

First thing you plan to do in retirement: My wife Jane and I look forward to spending our days with our four children, their spouses, and our 11 grandchildren.

An active clinician-scholar for more than 40 years caring for all types of pediatric eye diseases, James D. Reynolds, MD ’78, retired July 1 as the Jerald and Ester Bovino Professor and Chair of ophthalmology. Much of his work has been seminal, especially in the field of ROP (retinopathy of prematurity), where he has been funded almost continuously by the NIH and industry for more than 25 years in ROP clinical trials. His 2002 paper on evidence-based ROP screening guidelines remains the standard to this day. “It has been a great run for me. My own career has been meaningful in so many ways, and the department has blossomed beyond any expectations,” he says.

Academic degrees: Doctor of Medicine, University at Buffalo, 1978; Bachelor of Arts in biology, University at Buffalo, 1974.

Publishing numbers: peer-reviewed articles: 81; non-peer-reviewed articles: 20; chapters: 9; and editorials: 2.

Most meaningful awards: The Al Biglan Medal awarded by my fellowship alma mater, the University of Pittsburgh, for excellence in the field of ophthalmology.

Research project/ discovery you are most proud of: Leading the NIH-funded LIGHT ROP trial and publishing the results in the New England Journal of Medicine and my work as one of the six world experts who led the RAINBOW trial that set the standard in Europe for ROP anti-VEGF treatment that was published in The Lancet.

One piece of advice for aspiring physicianscientists: Always say yes! This attitude leads to many expected and unexpected career advancements.

Favorite UB memories: The grand opening of the Ira G. Ross Eye Institute on the Buffalo Niagara Medical Campus in 2007; achieving top third status of ophthalmology programs at the NIH; and of course, ALL the people who helped me along the way.

How you would like to be remembered by your UB colleagues: As an honest hard worker who led by example and consensus, always supportive of my students, faculty and staff while maintaining a fierce sense of personal honor and always putting the patient first, regardless of circumstance.

Best thing about Buffalo: I would have to boil it down to the people. They are the salt of the earth, as my country family used to say. They have made the best patients in the world.

First thing you plan to do in retirement: I have already started my two first things: spending time with grandchildren and finding more work.

“We extend our deepest gratitude for the service of both Dr. Reynolds and Dr. Tomaszewski. Their decades of exceptional leadership and their contributions to their respective fields have had a profound impact on the Jacobs School and have shaped and inspired the journeys of countless students, researchers, faculty and staff.”

- Allison Brashear, MD, MBA

A prominent collection of community leaders and alumni have joined the Jacobs School, helping to steer and support the school as its new Dean’s Advisory Council. Members of the council serve the school in the core areas of advocacy and community engagement. Chaired by Jerry Jacobs, Jr. and Cindy Abbott Letro, the Dean’s Advisory Council meets several times per year and acts as an advisory board for Dean Allison Brashear, MD, MBA, and school leadership. Members of the council are appointed to threeyear terms.

“I’m

deeply grateful for the support of the alumni and business leaders who serve on the Dean’s Council. Their leadership, contributions and insight are invaluable resources to us and play a vital role in advancing the mission of

the Jacobs School.”

- Allison Brashear, MD, MBA

The council launched in 2024. Scott Bieler, CEO and President of West Herr Auto Group, served on the council during the 2024-25 term. Current members include:

Cappuccino works at Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center specializing in the surgical management of breast cancer and is an associate professor at the Jacobs School. She serves on the admissions committee at the Jacobs School and also serves as faculty advisor of CuMIN, the Jacobs School’s culinary medicine interest group. She was a founding board member for the UB Child Care Center and co-chaired UBreathe Free, the committee that made all university campuses smoke free. She was honored as one of 50 of America’s most positive physicians nationally.

A dedicated community volunteer, she is currently on the boards of the Buffalo AKG Art Gallery and the University at Buffalo Foundation and an emeritus member of the boards for the Western New York Women’s Foundation, and Chaîne des Rotisseurs Foundation. She previously served on the boards of Lockport City Ballet and the Kenan Center. She has chaired numerous charity events for schools and cultural organizations, including the Eastern Niagara United Way, the UB Scholarship Galas and Elmwood Franklin School.

She is a features editor and writer for Gastronome and Cuvee, food and wine magazines for the Chaîne des Rotisseurs. She and her husband have also participated in medical missions to Kenya, and they have produced five feature-length films with their son for Vertebra Film Development.

Internationally recognized as a leader in philanthropy, Dedecker retired as president and chief executive officer of the Community Foundation for Greater Buffalo in December 2022.

During her 17-year tenure at the Community Foundation working with individuals, families, foundations and organizations to steward their charitable assets, the Community Foundation grew to more than $870 million.

Dedecker is a member of the Generosity Commission—a blue-ribbon national panel focused on nurturing giving and volunteering. Her recent board service includes FSG and the Global Fund for Community Foundations. She is president emeritus of the Junior League of Buffalo, the Association of Junior Leagues International and the National Women’s Hall of Fame.

In recognition of her civic sector expertise, Dedecker was appointed to the White House Council on Service and Civic Participation and named co-chair of the U.S. Committee of the United Nations International Year of the Volunteer.

For her contributions, she was inducted into the WNY Business Hall of Fame in 2024 and was named the 2018 Buffalo Niagara Executive of the Year by the UB School of Management.

Feldstein leads Retail and Business Banking at M&T Bank, supporting local consumers and business owners across the company’s communities.

In Retail Banking, he oversees a team of more than 7,000 employees across over 900 branches that serve approximately 2 million customers.

In Business Banking, which includes about 800 employees, he collaborates with regional leaders and local business bankers throughout the Northeast U.S. to provide services and financial guidance to more than 330,000 small and mid-sized businesses.

Feldstein has nearly 30 years of experience in the financial and professional services industry. Prior to his current role, he served as M&T’s Western New York regional president.

He is a member of the executive committee for the Buffalo Niagara Partnership and serves on the boards of both the WNY Community Foundation Business Leaders Task Force and the Westminster Foundation. He also serves as the executive sponsor for M&T’s Hispanic/Latinx Employee Group.

Before joining M&T, he held positions at Skadden, Arps, Slate Meagher & Flom LLP in New York and Diamond Management Consulting in Chicago.

Higgins serves as president and CEO of Shea’s Performing Arts Center, where he aims to position the three-theatre campus to sustain and grow its centurylong tradition of delivering exceptional experiences and top performances to theatre goers. His work includes elevating Shea’s Buffalo by upgrading patron amenities and preserving the institution’s historic character, building on the theatre’s foundational standing as a magical place.

For over 19 years Higgins served as a member of Congress, maintaining a focus on targeted initiatives which addressed the needs and leveraged the strengths unique to Western New York. A member of the Congressional Arts Caucus and author of federal Historic Tax Credit legislation, Higgins has long recognized the social and economic value of investments in preservation and culture.

Before serving in Congress, Higgins was elected to the Buffalo Common Council and later the New York State Assembly.

As CEO for Delaware North, a familyowned, global leader in hospitality and entertainment, Jacobs oversees the company and its seven operating subsidiaries, focusing on strategic growth and planning, corporate governance and financial management. Jacobs has served several philanthropic, civic and business organizations, including as board chair for the UB Council, the primary oversight and advisory body to the university’s president and senior officers. He is on the board of The Corps Network, a national organization that engages young people and veterans through service programs, and board chair for biopharmaceutical startup Mimivax. He is a founding board member for the Say Yes Buffalo educational initiative. Jacobs’ service to the United Way of Buffalo and Erie County includes chair of the board of directors and annual fundraising campaign. He is a past member of the board of regents at Georgetown University and served three terms on the board for the UB Foundation. He is past chair of the Nichols School board of trustees, where he founded the Jacobs Scholars program for high-achieving students with financial need.

Jacobs completed a term on the U.S. Department of Commerce’s Travel and Tourism Advisory Board in 2015 and was named to the U.S. Secretary of Interior’s “Made in America” Outdoor Recreation Advisory Committee in 2018.

Letro is a community volunteer and marketing specialist with over 30 years of experience in the broadcast field. She currently serves as the chair of the Western District of New York State Parks, chairs Visit Buffalo Niagara, the region’s convention and tourism bureau, and is past chair of the Buffalo Niagara Film Commission. She currently serves or has served on the St. Bonaventure Board of Trustees, the Community Foundation of Greater Buffalo, the Kleinhans Music Board, and the Theodore Roosevelt Inaugural Site. She is the past chair of the Board of Directors of the Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra and the Burchfield Penney Art Center.

She is consistently listed in the Business First’s Top 200 Women of Influence and was listed in its Top Ten Women of Influence in 2022.

Letro is business manager of her husband’s law firm, Francis M. Letro Attorneys at Law, and makes her home in the city of Buffalo.

McGlynn is a distinguished leader in the pharmaceutical and biotechnology industries, with a career spanning over four decades dedicated to advancing global health.

McGlynn began her career at Merck, where she held various leadership roles from 1983 to 2009, culminating as president of Merck Vaccines and Infectious Diseases. She later served as CEO of the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative (2011–2015), leading global efforts in HIV vaccine research and advocacy.

Currently, she serves on the boards of Novavax, Inc., Amicus Therapeutics, and the University at Buffalo Foundation, contributing her expertise to organizations focused on innovative vaccines, rare disease treatments, and higher education. She is also president and board chair of the HCU Network America, a nonprofit dedicated to supporting families affected by homocystinuria and advancing research and policy for this rare metabolic disorder.

McGlynn’s contributions have been recognized with numerous honors, including a UB Honorary Doctorate (2017), Distinguished Alumni Award (2010), and the Leadership in Pharmaceutical Award (2003) from UB’s School of Management.

Roth was one of the original founders of Sharp Community Medical Group and has served on the board of directors since its inception in 1989, holding a number of council seats, including the executive committee. He also serves on the Sharp HealthCare Board of Directors. Roth was elected president of Sharp Community in July 2011. In 2008, he was named to the San Diego Magazine’s List of Top Doctors and in 2010, he was the recipient of the Sharp Memorial Hospital/Spirit of Planetree Award.

Roth began his private practice of medicine in 1986 at Sharp Cabrillo Hospital. He went on to found San Diego Internal Medicine Associates in Kearny Mesa, and subsequently San Diego Hospitalist Associates, where he practices internal medicine and leads the Metro Hospitalist team.

He completed his medical education and internship at the University at Buffalo. He completed his residency at UCSD Medical Center. Roth is Board Certified in internal medicine with a specialty in urology.

Walsh is the chairman of Walsh Duffield Companies, Inc., a family-owned insurance agency headquartered in Buffalo. Representing the fifth generation of leadership, he joined the firm in 1973 after gaining experience at Citibank in New York City and Aetna Life and Casualty Company in Hartford. His extensive civic involvement includes leadership and support roles with organizations such as the United Way of Buffalo & Erie County, the Darwin Martin House Restoration Corporation, the Albright-Knox Art Gallery, and the Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra, among many others.

Walsh is also deeply committed to higher education and athletics. He co-chaired the local organizing committee for the NCAA’s 2003 Frozen Four hockey finals in Buffalo and served as chair of the Yale Alumni Schools Committee of Western New York, interviewing over 900 applicants, and holding various leadership roles with the Association of Yale Alumni, Yale Alumni Fund and its Development Board.

He has received numerous awards for his professional excellence and community service, including the Galanis Award for Excellence in Family Business, the UB President’s Medal, and the NCCJ Citation Award. The United Way recognized him as Philanthropist of the Year.

Wilson currently serves as one of the three Life Trustees appointed to guide the Ralph C. Wilson, Jr. Foundation, a grantmaking organization established by her late husband, Ralph Wilson.

Based in Detroit, the Foundation began with a grantmaking capacity of $1.2 billion over a 20-year period. To date, the Foundation has distributed more than 1,000 grants across its five areas of focus: Active Lifestyles; Preparing for Success; Entrepreneurship and Economic Development; Caregivers; and Nonprofit Support & Innovation.

Mary Wilson has been an outspoken champion for the city of Buffalo and is a supporter of many Buffalo organizations. During Ralph’s ownership of the Buffalo Bills, Mary worked to establish the Western New York Girls in Sports program and continues to bring together more than 200 girls, ages 9-12, to participate in various sports taught by young athletes from local universities and sports clubs. She is a supporter of the Buffalo AKG Art Museum, Burchfield Penny Art Center, Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra, Hospice of Western New York, First Tee, Oishei Children’s Hospital, SPCA Serving Erie County and FeedMore WNY, among others.

She is a former board member of the USTA Tennis Foundation and played in the Wimbledon Championships in 1976. Wilson was also a past president of the National Senior Women’s Tennis Association.

Steven J. Fliesler, PhD, SUNY Distinguished Professor and Meyer H. Riwchun Endowed Chair Professor of ophthalmology in the Jacobs School, has been honored with the 2025 Schroepfer Medal from the American Oil Chemists’ Society (AOCS).

The medal is typically awarded every other year. This one-of-a-kind prize has been awarded to 12 internationally recognized academic scholars from the United States and Europe since its inception in 2002.

An internationally renowned vision scientist, Fliesler is considered the world’s leading expert on cholesterol metabolism in the retina.

His research was instrumental in describing for the first time the involvement of the lipid intermediate pathway in glycoprotein synthesis in the human retina and the importance of protein glycosylation for normal retinal photoreceptor cell differentiation. The lipid intermediate pathway shares some molecular constituents with the biochemical pathway used for cholesterol synthesis.

“I am extremely honored to have been recognized by the AOCS for my research over the past four decades in the area of cholesterol metabolism in the retina,”

Fliesler says.

“This lifetime achievement award is particularly meaningful to me, because I performed my PhD research under the guidance of Professor George J. Schroepfer, for whom this award is named, at Rice University in Houston, Texas, many years ago.”

“No one is more deserving of this award than Steve Fliesler. Steve has made important contributions to the understanding of Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome (SLOS), a devastating disorder caused by mutations in a gene in the cholesterol biosynthesis pathway,” says Ned A. Porter, PhD, professor emeritus of

chemistry at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine.

Indeed, there is now what is known as “the Fliesler model” of the disorder, a pharmaceutically altered rodent that has been important in understanding the consequences of the perturbed cholesterol biosynthesis found in SLOS, Porter notes.

Beth A. Smith, chair of the Department of Psychiatry, was accepted into the prestigious Executive Leadership in Academic Medicine (ELAM) program for 2025-26. The highly competitive fellowship prepares accomplished women professors for senior leadership roles across the health care landscape.

Beth A. Smith, MD ’00, chair of the Department of Psychiatry, has been chosen as a 2025-2026 fellow for the prestigious Hedwig van Ameringen Executive Leadership in Academic Medicine (ELAM) program.

Hosted by Drexel University College of Medicine, this highly competitive, yearlong fellowship builds upon Smith’s outstanding leadership and dedication to advancing psychiatry by her executive leadership skills.

ELAM prepares accomplished women professors at academic health centers for senior roles across the health care landscape, from academic institutions— medicine, dentistry, public health and pharmacy—to hospitals and health care systems, including C-suite positions. During the program, Smith, a clinical professor of psychiatry and pediatrics, will undertake online assignments, engage in community building and lead a collaborative Institutional Action Project focused on an institutional or departmental challenge.

This project will address an institutional

or departmental need or priority, further demonstrating her commitment to impactful leadership.

In a highly competitive selection process, Smith, was one of 100 ELAM fellows accepted into this year’s class. This cohort comprises exceptional leaders who are capable of making critical systemic change.

“I am deeply honored to be selected as an ELAM fellow,” says Smith. “This opportunity marks a personal milestone and a meaningful way to contribute to the future of academic medicine. I look forward to collaborating with leaders across the country, growing through the program’s curriculum, and bringing new perspectives back to Jacobs School to help strengthen our culture of collaboration, excellence and innovation.”

Two Jacobs School faculty members have been named SUNY Distinguished Professors, the highest faculty rank in the SUNY system.

Michael E. Cain, MD, professor of medicine and biomedical engineering; and Jian Feng, PhD, UB Distinguished Professor of physiology and biophysics, were appointed to the distinguished professor ranks by the SUNY Board of Trustees at its meeting on April 29.

The rank of distinguished professor is an order above full professorship and has three co-equal designations: Distinguished Professor, Distinguished Service Professor and Distinguished Teaching Professor.

Cain was named a Distinguished Service Professor in recognition of his “distinguished reputation for service not only to the campus and the University, but also to the community, the State of New York or even the nation, by sustained effort in the application of intellectual skills drawing from the candidate’s scholarly research interests to issues of public concern.”

Feng was named a Distinguished Professor in recognition of his international prominence and distinguished reputation within his chosen field.

Cain, who served as dean of the Jacobs School for 15 years, is an internationally recognized cardiovascular physicianscientist who specializes in the area of abnormal heart rhythms.

He has been recognized for his long-term leadership role in his field with numerous awards, including the Distinguished Service Award from the Heart Rhythm Society, the Stanley J. Sarnoff Spirit Award from the Scientific Board of the Sarnoff Endowment for Cardiovascular Science and the Arthur E. Strauss Award from the American Heart Association.

He is also the recipient of the UB President’s Medal for exemplary leadership, and the Legacy Award from the National Federation for Just Communities of Western New York.

Feng is a world leader in the molecular and cell biology of Parkinson’s disease. His research has centered on proteins and neurotransmitters in the brain that are pathophysiological elements in Parkinson’s.

He has identified the critical roles of the parkin gene in Parkinson’s disease. Feng developed the use of human-induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC) to generate patientspecific human dopaminergic neurons in vitro to study the role of parkin in the disease.

Among his numerous honors are designation as a UB Distinguished Professor, the Visionary Inventor Award, the Bridge Award for Translational Research, UB Exceptional Scholars: Sustained Achievement Award, the SUNY Chancellor’s Award for Excellence in Scholarship and Creative Activities, and the Stockton Kimball Award.

Teresa L. Danforth, a clinical associate professor of urology, has been named to the American Urological Association 202526 Leadership Class in recognition of her leadership and research achievements.

In recognition of her leadership, research achievements, and educational excellence, Teresa L. Danforth, MD ’07, has been named to the American Urological Association (AUA) 2025-26 Leadership Class.

Danforth is a clinical associate professor and residency program director in the Department of Urology and is also chief of urology at Kaleida Health.

A longtime board member of the AUA’s Northeastern Section, Danforth was elected to the organization’s leadership class this spring, in company with emerging top urologists across the country.

Danforth says that joining the leadership class could lead to making a larger, national impact on the field of urology.

“I think being a part of this leadership course will put me in a position to make more of an impact at that level and will provide me a better skill set and also provide communities and networking opportunities to meet with mentors,” she says.

Involvement has also meant being able to work with and be mentored by renowned urologists and AUA leaders, Danforth says, and collaborating with other inductees on a collaborative research project.

Danforth is co-investigator on two National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases grants: a $3.3 million grant focusing on pelvic pain management and a $1.6 million grant to study catheterassociated urinary tract infection (UTI).

Gary Iacobucci, a general psychiatry resident and research assistant professor in biochemistry at the Jacobs School, was selected as a 2025 Outstanding Resident by the National Institute of Mental Health.

Gary Iacobucci, MD, PhD, wasn’t one of those people who always knew they’d go to medical school. As an undergraduate at the University at Buffalo, his main interest was research. But as he headed into a biochemistry doctoral program at UB, he became more interested in the clinical aspects of what he was studying.

It was clearly the right decision. This summer, Iacobucci was notified by the National Institute of Mental Health that he was selected to receive its prestigious 2025 NIMH Outstanding Resident Award.

A general psychiatry resident and research assistant professor in biochemistry in the Jacobs School, he is one of just 12 residents nationwide chosen for this honor.

Iacobucci’s interest in clinical care began while doing doctoral work in the laboratory of Gabriela K. Popescu, PhD, professor of biochemistry. When he mentioned he was considering medical school, she connected him with a psychiatrist colleague he could shadow.

He began the MD program in the Jacobs School in 2019. And in his fourth year, as all medical students do, he began looking at residency programs.

Iacobucci started looking at the Jacobs School’s psychiatry residency for its strong, high-volume clinical program and emphasis on psychotherapy.

“What I appreciate most is how understanding and flexible the department has been in developing a program that helps me bolster my ability to be a good clinician while allowing me to develop my own unique vision as to what my research program will be,” he says.

David Cazares Dorantes, a secondyear medical student in the Jacobs School, has been selected as one of five recipients of the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) 2025 ACE Award for Advocacy, Collaboration and Education.

The award recognizes academic medicine champions who are honored for leading and collaborating with the nation’s medical schools and academic health systems to improve the health of patients, families and communities nationwide.

The AAMC cited Dorantes’ work at the Good News Clinics in Georgia and as a Spanish medical interpreter, experiences that reflect his commitment to serving vulnerable communities.

He is assistant program manager for UB HEALS, the Jacobs School’s student-run street medicine initiative, and he serves as class representative for Polity, the student

Renée Reynolds, MD, clinical associate professor of neurosurgery in the Jacobs School, has been installed as the inaugural recipient of the Kevin and Janet Gibbons Endowed Chair in Neurological Surgery.

Reynolds officially accepted the role at a ceremony on May 27 to recognize this appointment and to acknowledge the generosity of Kevin J. Gibbons, MD, and Janet Gibbons, who supported the endowed chair, along with UBMD Neurosurgery.

“This endowed chair represents more than just a prestigious title. It is a powerful investment in our future,” said Allison Brashear, MD, MBA, UB’s vice president for health sciences and dean of the Jacobs School. “Her growth will not only advance scientific discovery and advance clinical care and medical education, but her work also directly benefits patients, students and families in Western New York and beyond.”

Elad I. Levy, MD, MBA, the L. Nelson Hopkins III, MD, Professor and chair of neurosurgery, spoke about the Gibbons family’s generosity, dedication, and lasting

government organization. In Buffalo, he works at Jewish Family Services on refugee resettlement. A member of the American Medical Association’s Medical Student Section Committee on Civil Rights, Dorantes is also the UB representative for the Latino Medical Student Association.

“Even so early in his career, David is absolutely committed to putting patients first,” says Allison Brashear, MD, MBA, UB’s vice president for health sciences and dean of the Jacobs School, “whether that means being boots on the ground to help unhoused people get care, translating English to Spanish, or serving in our student-run free clinic. With this award, the AAMC is recognizing the powerful, positive impact his advocacy is having on our community.”

Dorantes takes absolutely nothing for granted. He says there have been multiple times in his life when things looked hopeless, but good people stepped in to help. Those experiences left him with an unwavering sense of responsibility to help improve similar circumstances for others. “When you watch your parents sacrifice

so much, there’s no way I can see those sacrifices and not do everything I can to help my neighbor,” he says.

“UB has a really big presence in the community and that’s huge for me,” says Dorantes. “The Jacobs School has provided me the resources to pursue my advocacy work and my need to serve the community that I live in. I think the school is really good at that, giving us avenues to serve others and not be alienated from the people we care for.”

David Cazares Dorantes is in his second year in the MD program at the Jacobs School. He has been selected as one of five recipients of the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) 2025 ACE Award for Advocacy, Collaboration and Education.

impact.

“It is with humility and gratitude that we acknowledge the support of Kevin, Janet and the Gibbons family, and our UBNS partners,” he said. “You’ve given us the gift of this chair, which will continue to inspire and shape the future of neurosurgery education for generations to come.”

Gibbons served as senior associate dean for clinical affairs and executive director of UBMD Physicians’ Group. He joined the Jacobs School’s neurosurgery faculty after completing his residency at UB in 1993 and would later serve as vice chair and program director.

Levy shared some of Gibbons’ research achievements, including development of the Gibbons classification, used to evaluate motor function in patients with spinal cord injuries. In 2017, Gibbons authored a widely read and cited paper in Neurosurgery assessing surgical headwear and its effects on infection rates.

Reynolds reflected on her journey through medicine and neurosurgery and now as an endowed chair recipient.

“Many of the accolades necessary to be considered for such a recognition can be counted—research papers, grants, selected abstracts, visiting professorships,” she

said, but was reminded of a favorite quote, that “not everything that can be counted counts, and not everything that counts can be counted.”

“There is no greater full-circle moment than watching a resident you have trained move on to independent practice, start to ascend the ranks of our national organizations, become assistant program directors or program directors themselves or, most meaningfully, picking up the phone just to tell you thank you for everything you’ve done to help them get there.”

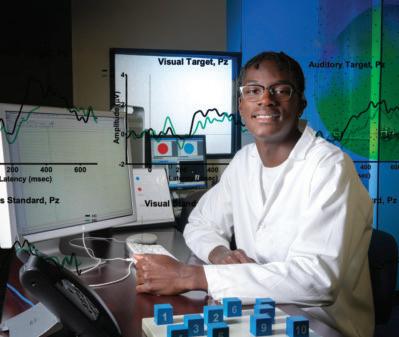

As they age, some people find it harder to understand speech in noisy environments. Now, UB researchers have identified the area in the brain, called the insula, that shows significant changes in people who struggle with speech in noise.

According to David S. Wack, PhD, first author and associate professor of radiology in the Jacobs School, a study published in the journal Brain and Language found that the left insula shows stronger connectivity with auditory regions in people who struggle with speech in noise, suggesting a permanent rewiring of brain networks that persists even when they’re not actively listening to challenging speech.

“When you have hearing loss, you are recruiting other areas of the brain to do more processing in order to decode what’s going on,” Wack says. “What’s interesting is that we found the insula working harder when the brain was supposedly at rest, when there was no speech in noise.”

The new molecule targets a protein called Magi-1, a scaffolding protein that brings specific proteins together at specific locations within the cell membrane. One of the proteins it interacts with is NaV1.8, an ion channel that plays an important role in transmitting pain.

Prediabetes, when blood sugar is higher than normal but not high enough to be considered diabetes, is more lifethreatening in people aged 20-54 than it is in older populations, according to a paper published in JAMA Network Open.

A vaccine under development at UB has demonstrated complete protection in mice against a deadly variant of the virus that causes bird flu.

The work, detailed in a study published in the journal Cell Biomaterials, focuses on the H5N1 variant known as 2.3.4.4b, which has caused widespread outbreaks in wild birds and poultry, in addition to infecting dairy cattle, domesticated cats, sea lions and other mammals.

In the study, scientists describe a process they’ve developed for creating doses with precise amounts of two key proteins— hemagglutinin and neuraminidase—that prompt the body’s immune system to fight bird flu.

It’s also a potential step toward more potent, versatile and easy-to-produce vaccines that public health officials believe will be needed to counteract evolving bird flu strains that grow resistant to existing vaccines.

“We obviously have a lot more work to do, but the results thus far are extremely encouraging,” says the study’s lead author Jonathan F. Lovell, PhD, SUNY Empire Innovation Professor of biomedical engineering.

That finding, he says, has implications for how dementia may develop, since the insula is also associated with early dementia.

“It’s not that hearing loss causes dementia,” Wack says, “but if we could find a way to preserve the fidelity of the signal coming in, then the brain wouldn’t have to start compensating for that hearing loss.”

A new molecule developed by Jacobs School researchers acts like a local, longlasting anesthetic, providing robust pain relief for up to three weeks, according to the results of preclinical studies reported recently in the journal Pain.

“Local anesthetics dramatically changed health care when first introduced into clinical practice during the turn of the 20th century,” notes Arindam Bhattacharjee, PhD, professor of pharmacology and toxicology and senior author on the paper. “The limitation with local anesthetics is that they aren’t very selective for your pain fibers—they block touch sensation as well— and they don’t last very long. In our new paper we showed that a single injection locally can relieve chronic pain behavior for three weeks.”

“The literature has been inconsistent, particularly when accounting for key modifying factors, such as age, race/ ethnicity and comorbidities,” says first author Obinna Ekwunife, PhD, assistant professor of medicine. “We wanted to explore whether these factors influenced the association between prediabetes and mortality in a nationally representative U.S. adult population.”

The researchers analyzed data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), the ongoing national survey run by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that measures the health and nutrition of children and adults.

The data showed a significant association between prediabetes and mortality before the researchers controlled for variations among demographics, lifestyle factors and comorbidities. But once they controlled for those factors, the association went away.

“However, we found that the significant relationship between prediabetes and mortality was maintained after adjustment when the analysis focused on adults aged 20-54,” says Ekwunife.

John C. Hu, MD, PhD, clinical assistant professor of medicine in the Division of Infectious Diseases, is a co-senior author on a study published in the journal Clinical Infectious Diseases on secondary bacterial pneumonia following viral infections.

The retrospective study design leveraged the VA’s internal Corporate Data Warehouse—a comprehensive national database that includes health records from VA hospitals across the country.

The researchers compared how often people developed bacterial pneumonia after having the flu, RSV, or COVID-19, helping them to see if COVID-19 leads to similar or different risks compared to these other respiratory viruses.

“We found that people who had the flu or RSV were more likely to develop a secondary bacterial infection caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae. However, this was not the case for people who had COVID-19,” Hu says.

“This may suggest that COVID-19 behaves differently from the flu and RSV when it comes to how it interacts with respiratory bacterial pathogens, and perhaps our immune system.”

Researchers have shown for the first time that intermittent fasting increases the efficacy of anti-androgen therapy in prostate cancer, according to a paper reporting preclinical results published in Cancer Research.

Proteins, carbohydrates and fats are necessary for the uncontrolled growth of cancer cells and the typical Western diet in particular, with its heavy animal fat and protein content, has been linked to increased incidence of cancer and poor prognosis.

Consequently, caloric restriction has emerged as a potential strategy for reducing the incidence of cancer and delaying cancer progression. It has been shown in preclinical models to reduce circulating growth factors and hormones that promote cancer.

“Diet can have a significant impact on the biology of prostate cancer and dietary interventions should be seen as an adjuvant tool,” says Roberto Pili, MD, corresponding author and associate dean for cancer research and integrative oncology in the Jacobs School.

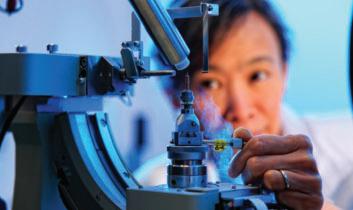

A breast scan for detecting cancer takes less than a minute using an experimental system that combines photoacoustic and ultrasound imaging, according to a study in IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging.

“Our system, which is called OneTouchPAT, combines advanced imaging, automation and artificial intelligence—all while enhancing patient comfort,” says the study’s corresponding author Jun Xia, PhD, professor in Department of Biomedical Engineering.

Xia and colleagues have been studying photoacoustic imaging, which works by emitting laser pulses that cause lightabsorbing molecules to heat up and expand. This in turn creates ultrasound waves that allow medical professionals to detect blood vessels that often grow more in cancerous tissues.

Typically, these systems require a sonographer to manually scan the breast, or they rely on separate devices for photoacoustic imaging and ultrasound imaging.

OneTouch-PAT combines both scans automatically. The device performs a photoacoustic scan first, followed by an ultrasound scan, then repeats this pattern in an interleaved way until the entire breast is covered. The system then processes the data using a deep learning network to improve image clarity. Ultimately, the research team found that OneTouch-PAT provides a more in-depth and clearer view of breast tumors compared to photoacoustic and ultrasound imaging systems that are operator-dependent.

Monica C. Pillon, assistant professor of structural biology, is senior author on a new study published in Nature Communications that provides a detailed structure of a human enzyme critical for antiviral defense and platelet function.

Monica C. Pillon, PhD, assistant professor of structural biology, is senior author on a new study that provides a detailed structure of a human enzyme critical for antiviral defense and platelet function.

Through biochemistry and advanced imaging, the research, published online in Nature Communications, uncovered the molecular principles underlying SLFN14’s RNA processing activity, Pillon says.

“Gene dysregulation is a hallmark and major culprit of disease. A central determinant of gene expression is RNA abundance, which is fundamentally the balance of RNA synthesis and RNA decay,” she says.

“Ribonucleases are the centerpiece to many RNA processing and decay pathways,” Pillon adds. “For this reason, my research program focuses on understudied ribonucleases, like SLFN14, to understand their vital role in defining eukaryotic gene expression and cell fate.”

During a viral infection, SLFN14 is activated to repress gene expression and limit viral replication. However, exactly how this happens is still an active area of research.

SLFN14 dysregulation is linked to human diseases, including ribosomopathies and inherited thrombocytopenia, a bleeding disorder that is often characteristic of low platelet count and low platelet activation.

By Ellen Goldbaum | Photos by Sandra Kicman

It was about trauma and pain and remembrance. It was about the stories behind the grim statistics. It was about honoring the lives of victims cut tragically short.

Those factors and more made the 2025 Remembrance Conference an equally moving experience whether participants traveled across town or across the country to attend.

The idea for the conference was sparked in 2023 in a conversation between Allison Brashear, MD, MBA, vice president for health sciences and dean of the Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, and Aron Sousa, MD, dean of the Michigan State University (MSU) College of Human Medicine. Both of their campuses had recently been impacted by gun violence. Soon thereafter, faculty and students from both schools began meeting annually to remember, to heal, to share their experiences and support each other.

in 2024. In June 2025, the Jacobs School hosted a three-day event focusing on the special role medical schools and health care in general can play in working to reduce firearm injuries and deaths through a public health approach.

“The trauma goes beyond the victim,” Brashear noted. “We need to be thinking about what we can do as health care professionals. We want to energize people to go back to their schools and communities and say, ‘What can we do?’”

In his opening remarks, Sousa noted that not all communities are affected by gun violence in the same way. “This is about racism. This is about domestic violence. This is about mental health. That’s why we’re here.”

From Friday afternoon through Sunday morning, 75 participants and speakers gathered at the Jacobs School. They came from UB and MSU, and from local and national universities and organizations including Yale, SUNY Downstate, the University of New Mexico, the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), Western New Yorkers Against Gun Violence, Most Valuable Parents (MVP), St. Joseph University Church, the 5/14 Oral History Project, Erie County Central Police Services, Erie County Medical Center, The Non-Violence Project, BRAVE, SNUG and many others.

They learned that in 2022, more than 48,000 people died from firearms in the U.S.; more than half of those were suicides. In the keynote address that opened the conference, Megan Ranney, MD, MPH, dean of the Yale School of Public Health, explained why public health is the appropriate approach for addressing gun violence.

“We need to be thinking about what we can do as health care professionals. We want to energize people to go back to their schools and communities and say, ‘What can we do?’”

-

Allison Brashear, MD, MBA

It begins with gathering data about the threat, identifying what puts people at higher risk or what protects them, developing and evaluating interventions, and then implementing the most successful interventions.

The Remembrance Conference is the offshoot of a 2023 conversation between medical school deans in the aftermath of deadly shootings at or near their respective schools. Since then, Allison Brashear, dean of the Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, and Aron Sousa, dean of the Michigan State University College of Human Medicine, have endeavored each year to bring together faculty, staff, students, community groups, elected officials and industry experts to remember, heal, share their experiences and advocate for safer communities.

She said that such a harm reduction approach has been remarkably successful in mitigating the harm caused by car crashes. A combination of drunk driving laws, public education, seat belts, airbags, speed limits and engineering improvements to cars, have all led to reductions in deaths due to vehicle crashes.

Ranney said that such an approach has not been tried, “partly because there was no funding for this type of work and because people like me were told not to work on this.”

She has not been deterred. She cofounded the American Foundation for Firearm Injury Reduction in Medicine (AFFIRM), a nonprofit committed to ending the gun violence epidemic through a nonpartisan, public health approach; it works with a variety of communityfocused organizations, such as 4H Shooting Sports clubs.

Rob Gore, MD ’02, an emergency medicine physician at University Hospital at Downstate in Brooklyn, the author of “Treating Violence: An Emergency Room Doctor Takes on a Deadly American Epidemic,” and a Jacobs School alumnus, is similarly focused on preventing gun violence.

Working as an emergency medicine physician at Brooklyn’s University Hospital at Downstate, he saw how many of his patients were young Black men with life-threatening wounds from gunshots or stabbings. It drove him to start searching for the roots of violence and ways to prevent it. He founded KAVI, Kings Against Violence Initiative, a violence intervention program in Kings County.

KAVI operates programs in schools and hospitals through a network of volunteers who work with patients and their families; they work on multiple levels to prevent acts of retribution, make referrals and ultimately establish support systems. “If your basic needs are not met, you’ll go back out to a volatile situation,” Gore said.

He adds that every health care worker who treats these patients is also affected. “There’s the stressor from trying to keep someone alive,” Gore said. “That’s its own special beast. The idea that ‘Wow, if I just had a little more time and a little more money, I could keep this person alive.’ This is the work. This is the challenge.”

‘Not anti-gun, anti-shooting-people’

Similar conditions working in his state’s only Level 1 trauma center prompted Richard Miskimins, MD, assistant professor of surgery and trauma medical director at the University of New Mexico, to become engaged in this work. New

Mexico, a very rural state, is among those with the highest violent crime levels in the U.S. as well as having one of the highest suicide rates. “It’s a blue state that loves guns,” said Miskimins, who adds, “I am not anti-gun. I am anti-shooting-people.”

His advice for working in this space: “Avoid being an absolutist. Are you unwilling to compromise? Then you’re part of the problem.” He works with organizations that might seem unlikely; he has a strong partnership with a local shooting range, for instance. He and his colleagues do Stop the Bleed events at local high schools, where they also teach conflict resolution and violence interruption.

“Avoid being an absolutist. Are you unwilling to compromise? Then you’re part of the problem.”

- Richard Miskimins, MD

He stressed the need to base firearm injury prevention on solid data and to tailor responses to specific communities. “We track the number of times kids have guns in schools,” he said, “we facilitate coordination between agencies.”

Miskimins has led numerous antiviolence initiatives through social intervention, education, mentorship and legislation. He has worked for the establishment of an Office of Gun Violence Prevention in New Mexico and a safe gun storage law that makes adults criminally liable if their negligence makes a firearm accessible to a minor.

Other legislative initiatives discussed included New York State’s Extreme Risk Protection Order (ERPO), also known as the “Red Flag Law,” which 21 states now have. Gale R. Burstein, MD, commissioner, Erie County Department of Health, and professor of pediatrics, Jacobs School, and

A panel of medical students discussed how relevant discussions about gun safety are to pediatrics, especially since firearm violence is the most likely cause of death for children in the U.S. The students, who established the UB chapter of Scrubs Addressing the Firearm Epidemic (SAFE), noted that so much attention is paid to safety features like bike helmets and seatbelts, it is essential to also include gun safety when talking to patients.

“Normalize the discussion,” said Kerryann Koper, a fourth-year student at

“We want to reach every single medical student,” she said, “and help them incorporate firearm safety into patient care conversations.”

Those conversations often don’t happen because clinicians don’t feel confident about bringing the topic up, a concern echoed later in the conference by keynote speaker Patricia Logan-Greene, PhD, associate professor in the UB School of Social Work and co-leader of the Grand Challenge in Social Work to Prevent Gun Violence. She said that social workers don’t typically bring up the subject because of a

Ryan Belka, JD, assistant attorney general, explained how ERPOs function. If a health care provider has concerns about a patient who has access to weapons, they should report their suspicions to law enforcement who may then choose to file an ERPO.

“We want to reach every single medical student and help them incorporate firearm safety into patient care conversations.”

- Kerryann Koper

the Jacobs School. “Say something like ‘I talk to all my patients about home safety.’”

The students work closely with Buffalo Rising Against Gun Violence (BRAVE) and Should Never Use Guns (SNUG), which also presented at the conference and which Koper said provide critical longitudinal follow-up care after a patient leaves the hospital.

They noted that fewer than 20 percent of medical schools include firearm safety in their curriculum, but Koper said that it’s relevant to every specialty, whether that’s geriatrics and a provider is concerned about a gun owner experiencing cognitive decline, or it’s pediatrics or OB-GYN. “Sixty percent of all homicides involve intimate partner violence,” she said, adding that homicide is the leading cause of death in the U.S. for pregnant women.

lack of training on how to do so.

That’s important, she said, because the majority of school shooters got the guns they used from their home or someone else’s home. She cited a recent study that found that a third of youths questioned said they knew how they could get their hands on a loaded gun in just five minutes.

Social determinants of health are always a factor, she continued. “Good research shows that anti-poverty programs are effective anti-violence programs,” she said, explaining that violence goes down when requirements for programs like the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) are loosened.

It was a point also made by HenryLouis Taylor, PhD, professor of urban and regional planning in the School of

Architecture and Planning and associate director of UB’s Community Health Equity Research Institute. He talked about how conditions in underserved communities contribute to gun violence. “We believe there’s an association between these conditions and Black on Black violence,” he said, “the relationship of neighborhood social determinants of health and adverse health outcomes.”

The importance of neighborhoods, especially those that are underserved, is a key factor, agreed Zeneta Everhart, Buffalo Common Council member representing the Masten District, and mother of Zaire Goodman, one of three people who

pervasiveness of violence in general. Participants learned of the physical, social and personal devastation that guns inflict. But by the conclusion of the conference, attendees said they also felt positive and hopeful about continuing to work together to prevent gun violence. They liked that the conference was small enough to be intimate and the fact that attendees came from diverse communities. They said that a remembrance service, led by Pastor Kinzer Pointer and featuring the extraordinary singing of Sasha Joseph, MD, a 2025 Jacobs School graduate, was particularly special. Participants also came away feeling empowered to share what they learned.

“The ripple effects of this disease extend far and wide. It harms our bodies, it harms our psyches, it harms our communities.”

- Megan Ranney, MD, MPH

survived the mass shooting at a Buffalo grocery store on May 14, 2022. “We’ve got to care about the poor people before we solve gun violence,” she said, adding that after a shooting, nobody comes to the neighborhood to help people heal. But that’s precisely when resources and programming are needed most, she said.

Everhart’s observations are borne out by studies showing that after a shooting, kids fare worse in school, even if they didn’t know the person who was shot. “The ripple effects of this disease extend far and wide,” said Ranney. “It harms our bodies, it harms our psyches, it harms our communities.”

The speakers dealt honestly and bluntly with the horror of gun violence and the

“Some people assume, ‘Well, I’m not going into surgery or emergency medicine so why care about this?’” Koper concluded. “But as students, we want to say ‘Open your eyes. It’s everywhere.’”

Sponsors of the 2025 conference included UB’s School of Social Work, Cindy and Francis M. Letro, the AAMC, M&T Bank, Erie County Medical Center, the University of New Mexico School of Medicine, The Ohio State University College of Medicine, Catholic Health, the Community Health Center of Buffalo, Kaleida Health and California Northstate University College of Medicine.

WATCH:

See a video recap of the 2025 Remembrance Conference here.

Mark Your Calendars:

The event will be returning to Buffalo in the fall of 2026.

Visit medicine.buffalo.edu/ remembrance-conference for more details.

Advances in patient care. Breakthrough treatments. Training tomorrow’s doctors. America’s teaching hospitals, academic health systems and medical schools form the foundation on which our health care system is built.

Institutions of academic medicine improve the health of our communities and serve as a vital economic engine, generating 7.1 million jobs and adding $798 billion to the nation’s economy.

The Jacobs School is proud to be among America’s academic medicine hubs. Across the nation—with 99,000 students in medical education programs, 162,000 resident physicians, and thousands of other critical health professionals—medical schools, academic health systems, and teaching hospitals are ensuring the health care workforce is prepared to prioritize patientcentered care. Today, and tomorrow.

The practice of modern medicine remains vastly complex.

Yet its fundamental goal hasn’t changed: improving human health.

Achieving that goal means continuously learning more about health, disease and the body’s myriad mysteries. Research is the process that unlocks these mysteries.

As a core component of academic medicine, scientific inquiry touches everything at the Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences. While all research centers strive for excellence, at the Jacobs School, excellence is defined not just by discovery, but by impact.

In Western New York, Jacobs School researchers are already changing lives. Their work and findings today fuel the promises of tomorrow—the discoveries that continue to ripple outward from the lab to the bedside and to communities across Buffalo and beyond.

Deep community engagement, investment in cutting-edge technologies, cultivating the next generation, and collaboration over competition all propel the research enterprise at the Jacobs School. While these efforts have provided great insight, the Jacobs School’s capacity for discovery continues only to grow.

At the Jacobs School, cutting-edge tools and smartly designed spaces provide the means to carry out research processes and transform ideas into discoveries.

Yet the tools and environments that enable scientific inquiry are always changing and evolving. It is through continued investment in this infrastructure that the Jacobs School

Halterman, MD, PhD, senior associate dean and executive director of the Office of Research. “The truest measure of impact is translating discoveries from the bench to the bedside and from the bedside to the community. That’s why we design research spaces with intent, co-locating cores, imaging platforms, biorepositories, and patient exam rooms to bring science and care together.”

Further, research environments themselves must foster collaboration; the Clinical and Translational Research Center (CTRC) is a prime example.

maintains a leading edge and will keep pushing frontiers of knowledge.

Using molecular, cellular, structural and computational biology approaches, scientists at the school are gaining new insights into the body and the function and dysfunction of its systems, cells and molecules every day.

Basic science at the Jacobs School spans genomics and bioinformatics, genome integrity and gene expression, microbial pathogenesis, and the molecular basis of disease, to name but a handful of research areas in focus.

Researchers have access to a full range of state-of-the-art facilities and equipment that power discovery. The university’s core facilities and those at affiliated institutions provide advanced capabilities in imaging, microscopy, tissue preservation, stem cell research and computational analysis.

“From deciphering protein structure and function to developing new drugs to finding the best ways to deliver treatments that improve human health, our research spans the full spectrum,” says Marc

Occupying floors five through eight above the Gates Vascular Institute, just blocks from the Jacobs School’s downtown facility, the CTRC puts clinical and translational researchers in shared space. Patient examination rooms, research labs and animal facilities that include a transgenic mouse facility, are all housed under the same roof.