1 8 2 6 5 8 0 0 5 0 1 6 $10.95 SPRING 2023 Mister Miracle, Barda, Oberon TM & © DC Comics. JACK KIRBY COLLECTOR EIGHTY-SIX

KIRBY COMPARISONS!

JACK FAQs 4

Mark Evanier’s 2017 Baltimore

Comic-Con panel, featuring Tom King, Walter Simonson, Mark Buckingham, Jerry Ordway, Dean Haspiel, John K. Snyder III, and Rand Hoppe

EULOGISTS 19

Superstars of comics pay tribute the day after Jack’s 1994 passing

GALLERY 24 cover comparisons

INCIDENTAL ICONOGRAPHY 32 the FF suits up

THINKIN’ ’BOUT INKIN’ 34 with Dave Stevens, William Stout, and Barry Windsor-Smith

KIRBY OBSCURA 38 don’t open the box!

FOUNDATIONS 40 the final S&K Link Thorne story

BOOM! 48 Jack’s influences and inspirations for the Fourth World and beyond

EYEDUNNO 68 spot the differences

KIRBY KINETICS 73 a career comparison

COLLECTOR COMMENTS 78

Front cover inks: WALTER SIMONSON

Front cover colors: TOM ZIUKO

Special thanks to: CHRISSIE HARPER

COPYRIGHTS: Ben Boxer, Big Barda, Demon, Dingbats of Danger Street, Dr. Canus, Dubbilex, Forever People, Four-Armed Terror, Highfather, House of Mystery, House of Secrets, Houseroy, Infinity Man, Jason Blood, Jimmy Olsen, Kamandi, Kanto, Merlin, Metron, Mister Miracle, Morgaine le Fey, My Greatest Adventure, New Gods, Oberon, Orion, Shilo Norman, Spirit World, Superman, Ted Brown, Witchboy TM & © DC Comics • Arnim Zola, Avengers, Black Bolt, Black Panther, Blastarr, Bucky, Captain America, Celestials, Crystal, Devil Dinosaur, Diablo, Eternals, Falcon, Fantastic Four, Galactus, Grottu, Hank Pym, Harokin, Hulk, Inhumans, Journey Into Mystery, Ka-Zar, Klagg, Lockjaw, Machine Man, Martian, Nick Fury, Orikal, Prester John, Primus, Recorder, Red Skull, Shadow Thing, Shagg, Silver Surfer, Spider-Man, Stone Man, Strange Tales, Tales of Suspense, Thing, Thor, Triton, Ulik, Wasp, Watcher, Wyatt Wingfoot, X-Men TM & © Marvel Characters, Inc. • Black of New Genesis, Collages, Faces of Evil, Ramses, Sky Masters, Sundance of Mars TM & © Jack Kirby Estate • 2001: A Space Odyssey TM & © Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc.

• The Fly TM & © Joe Simon Estate • Black Magic, Fighting America & Speedboy, Link Thorne, Sunfire TM & © Joe Simon & Jack Kirby Estates • Country Lion, Sorceror TM & © Ruby-Spears Productions • “Camelot” lyrics © MTI

Don’t STEAL our Digital Editions!

ISSUE #86, SPRING 2023

THE

The Jack Kirby Collector, Vol. 29, No. 86, Spring 2023. Published quarterly (see?) by and © TwoMorrows Publishing, 10407 Bedfordtown Drive, Raleigh, NC 27614, USA. 919-449-0344. John Morrow, Editor/Publisher. Single issues: $15 postpaid US ($19 elsewhere). Four-issue subscriptions: $53 Economy US, $78 International, $19 Digital. Editorial package © TwoMorrows Publishing, a division of TwoMorrows Inc. All characters are trademarks of their respective companies. All Kirby artwork is © Jack Kirby Estate unless otherwise noted. All editorial matter is © the respective authors. Views expressed here are those of the respective authors, and not necessarily those of TwoMorrows Publishing or the Jack Kirby Estate. First printing. PRINTED IN CHINA. ISSN 1932-6912 1 Collector C’mon citizen, DO THE RIGHT THING! A Mom & Pop publisher like us needs every sale just to survive! DON’T DOWNLOAD OR READ ILLEGAL COPIES ONLINE! Buy affordable, legal downloads only at www.twomorrows.com or through our Apple and Google Apps! & DON’T SHARE THEM WITH FRIENDS OR POST THEM ONLINE. Help us keep producing great publications like this one!

OPENING SHOT 2

[above] Splash page pencils from Mister Miracle #13 [April 1973]. Our cover this issue is an unused version of MM #13’s cover, inked on vellum from a Xerox of Jack’s pencils, and originally intended for the UK’s Jack Kirby Quarterly before it ceased publication.

Contents

Opening Shot I

Compare & Contrast

think we all can agree: Jack Kirby was fast! This issue, you’ll read Gil Kane commenting on seeing Jack draw a ten-page Boy Commandos story in one day. For comparison, you’ll also read about Dave Stevens taking two weeks to draw one cover. Both Jack and Dave were great artists, but I’m pretty sure Dave didn’t produce enough material to support an ongoing publication about him, like this one (almost 30 years and still going strong!). Check out this checklist of Dave’s art career: https://www.davestevens.com/gallery/checklist

It only takes a couple of seconds to scroll down through his checklist, whereas the now sold-out Jack Kirby Checklist: Centennial Edition is 272 pages, mostly documenting Kirby’s published work. However, that published work is just one facet of his output. As regular TJKC readers have seen since 1994, there’s a wealth of unpublished Kirby work out there as well—quantitatively more than Dave Stevens’ entire lifetime of work, published or not. That isn’t meant to cast aspersions upon Dave—no one in comics has ever rivaled (or likely ever will rival) Jack’s prolific output, and Dave and Jack approached comics very differently, with unique requirements for their respective work. So there’s really no comparison there.

But think about that: Jack created as much, or more, unseen work, as many artists produced, ever.

Granted, in many cases, there are compelling reasons why it was never published, and some of it saw the light of day, but with minor or major changes made to it. So this issue, I wanted to focus on more of that obscure material, much for the first time—and when it was altered, show side-by-side comparisons of what it looked like before changes were made for publication. Thankfully, there is still this paper trail of Kirby’s original intent and execution, before someone who felt they knew better than Jack, was able to monkey with it.

Comics is a commercial medium, and Kirby was pragmatic enough to know that he was at the mercy of inkers, editors, and publishers who could, on a whim, transform his work to their liking. Despite those “corrections,” I can’t think of an instance where his underlying storytelling was totally obliterated by someone else (although Stan Lee sure came close in a few instances!). Take this issue’s alternate version of Mister Miracle #13’s cover, for example Does the published version (or the splash page) tell the story any better?

With hindsight, many of the alterations seem arbitrary and infuriating. But since Jack cared first and foremost about telling stories, I suspect

we fans are a lot more upset about the changes you’ll see here, than Jack ever was. H

[right] Take two genres that Kirby knew well (sci-fi and westerns), add pop culture of the times, and you get 1972’s Sundance of Mars! 1971’s NASA probe Mariner 9 was the first to orbit Mars, and the hit film Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid was released on September 23, 1969. Jack had to be aware of both, and you can even argue this unused character resembles Robert Redford (who many thought would make a perfect film Captain America back in the day). A sci-fi western set on Mars, starring Redford? Sounds like something only Kirby’s imagination could come up with!

[top] Richard Kolkman commented: “I’ve recently noticed the unpublished concept Sunfire, Man of Flame in a whole new light. It’s from circa 1955—so it would stand to reason this character might be a reaction to Atlas’ 1950s Human Torch revival. If Fighting American was to counter Captain America... perhaps this one was too close to the Torch and was turned down by Crestwood? But it probably was shown to someone, as a masthead was created for this pencil art [same as Night Fighter, which was a concept reworked from an unused Fighting American cover].”

2

by editor John Morrow

JACK F.A.Q.s Mark Evanier

Jack Kirby 100th Birthday Panel

Held at the Baltimore ComicCon on Sunday, September 24, 2017

Featuring Tom King, Walter Simonson, Mark Buckingham, Jerry Ordway, Dean Haspiel, John K. Snyder III, and Rand Hoppe. Transcribed by Steven Tice, and copyedited by Mark Evanier and John Morrow

of people were not his equal, and he didn’t care. If you came up to Jack with the worst artwork in the world—and, believe me, I did [laughter]—he would give you encouragement. He would tell you, “Keep at it. Keep drawing.” The only two things that would make him give you a negative critique of your work was, number one, if he thought that it was derivative, that you were just copying other people. I tell folks that if I had emerged from my association with Jack able to perfectly replicate Jack Kirby artwork, he would have considered me a colossal failure, because I wouldn’t have created anything.

[above] Jack hard at work in his home studio in 1971, and a portrait of the artist as a young Thing [right]. Read the story behind this drawing at https:// kirbymuseum.org/ blogs/effect/2015/ 06/02/the-summerof-jack/

[next page, top]

Baltimore Con panelists: (back row, left to right) Tom King, John K. Snyder III, Dean Haspiel, Rand Hoppe, and Mark Buckingham. (front row) Walter Simonson, Mark Evanier, and Jerry Ordway. Photo by Kevin Shaw.

[next page, bottom]

Tom King has just embarked on a new Kirby-related project titled Danger Street, which combines all the characters that appeared in DC’s First Issue Special #1–13 into one mini-series— including Kirby’s Atlas, Manhunter, New Gods, and Dingbats.

MARK EVANIER: I have it in my contract that any place I go, I get to do a panel about Jack Kirby. [applause] We have some people here with lots of good things to say about Jack. I’m not going to waste any of your time telling you that Jack Kirby was a fabulous artist. There are only about 50,000 comic books downstairs that you can look at to come to that conclusion yourself.

I was privileged to know Jack, to work with him for a brief time. I was his utterly useless assistant for a couple of years, meaning that he didn’t need assistants, but he was nice enough to say, “Oh, here’s something to do, and here’s some money, Mark.” My two major contributions to his work were to get out of the way—and I think I deserve a lot of credit for that [laughter]—and to help him get a better inker.

He was an amazing man, and I’ll just tell you, those of who never had a chance to meet Jack, he was a darling man. He was polite, he was honest, he was a nice person. He stood on no ceremony. [He was] “Jack.” If you called him “Mr. Kirby,” he would correct you, and he treated everyone as an equal. Obviously, a lot

And the other thing is if you were lazy. Jack was a strong believer in hard work. One of the many things I learned from him—I learned lots of stuff from Jack about writing and drawing. I learned an awful lot of stuff from Jack about being a human being—not that I can always apply it. He was just such a decent man, being kind to people—in some cases, I thought too kind with people he shouldn’t have trusted—but I learned that he was a very, very hard worker. One day, a life-changing day, I thought to myself, “You know, you’re never going to be able to have the imagination of this man, but it might be possible to work just that hard, to be dedicated to producing work, and producing not just for the reason of getting a paycheck, or not just even for the reason of having people say, ‘Wow, you do great work’—for the self-satisfaction you get from creating something.” And all of these people up here write and draw, and they’re all very talented people, and they probably have that same quality of, they finish the work, and they go, “Wow, I did something I’m very proud of here.” And sometimes you finish it, and it gets mauled in the production process. It gets inked badly, or colored badly, or printed badly, or distributed badly. You can still get a certain pride in the fact that you did your part of the job right, to the best of your ability, and that was Jack all the way through. He was just an amazing man, whose presence I feel every time I go to a comic book convention; he’s all over the room. He’s everywhere. You look around and you see his influence. Not only do you see the characters that he launched, but you see people doing his style, and you see people who have picked up the

A

column answering Frequently Asked Questions about Kirby

4

superannuated storytelling that he popularized. Jack told exciting stories. They were all exciting, they were all interesting. This is the reason that we keep going back to his work again and again. You all go back to it and reread it and reread it, and the twelfth reading, you suddenly see something that wasn’t there before, and you go, “Wait a minute. Did somebody sneak in in the middle of the night and doctor my copy? That wasn’t there when I read this story before.”

I read the whole Fourth World series maybe twice a year or something, and every time through I go, “Wait a minute, I was in the room when that page was done, and I didn’t notice that.” His stuff is so rich and so exciting that people want to continue it. They want to draw his characters, they want to tell more stories of his characters, they want to try to blend their imaginations. Our imaginations get stimulated by Kirby stories. You want to take that to the next level, and it’s very exciting to just look at Kirby work for the first time, to see someone who just discovers him and is just enraptured by him. Since he passed away, I have had people come to me constantly and try to say to me the thing they wish they could have said to Jack, and it’s a very personal thing, usually. It’s not just, “Yeah, I thought the comic book was really neat.” It was always, “That story meant a lot to my life,” or, “That series caused me to become a writer, or an artist, or a sculptor, or a sign painter,” or whatever it was, because he inspired a lot of people. And I keep doing these panels because I want to keep on sharing this good fortune I had to know him with others.

These people are all going to talk about what Jack meant to them, and, if we have time, we’ll answer whatever questions you may have about him, and I bet there’ll be plenty. This is Mr. John Snyder, folks. [applause] This is Mr. Tom King. [applause] Mr. Walter Simonson. [applause and cheers] Mr. Jerry Ordway. [applause] Mr. Mark Buckingham. [applause] The mover and shaker behind the Kirby Museum, which is doing wonderful work to preserve Jack’s stuff, and you’ll undoubtedly have spent some time already in their booth picking through stuff, this is Mr. Rand Hoppe. [applause] Mr. Dean Haspiel. [applause]

Immediately following, in the same room we’re going to be talking about Len Wein. That will overlap with Kirby in some ways. Well, Tom, you get to talk first. I have this all programmed in my mind. Tom is doing the new Mister Miracle series for DC, which many of you have probably picked up, and the ones of you who haven’t, should. Talk to us. What does Jack mean to you?

WALTER SIMONSON: I haven’t seen that

series yet, but I will say I’ve met several people here at the convention who’ve said, “Have you seen the new Mister Miracle series? It’s great!”

EVANIER: Actually, [DC Comics] sent me Xeroxes or it. I haven’t seen a printed copy yet. How many issues are out—two? That’s all I’ve seen so far, because DC stopped sending me—if you’ve ever worked for DC Comics and you want them to stop talking to you and stop sending you free comics, testify against them in a lawsuit. [laughter] So, anyway, I’m back now working with them, so...

TOM KING: When I close my eyes and see comics, I see Jerry Ordway’s pictures, and Walt Simonson drew the first comic that brought me in. I have John’s work on the wall over my desk. Anyways—

SIMONSON: We’re all really boring. [laughter]

KING: So, confession time. When I was a kid and I read Kirby comics, I hated them. When I first came to Eternals, I thought, “This is big and blocky and—I want John Buscema or even Jim Lee.” I wanted stuff that was fast, and cool, and sexy. I was like, “I don’t get this.” And I didn’t understand Kirby until I went to college. When I was in college, I would cheat on things—don’t tell—but, by turning it into comics, I was taking classes and doing dinosaurs and Calvin and Hobbes and that kind of sh*t. So I was taking a class on World War II, and I was like, “Oh, comic books are in World War II; easy paper to write.” And so I went to the library and read every comic I could from the Golden Age during World War II, and after a while it was like The Matrix, where I could see the code instead of the comics, because there was a formula. You start to see the formula, and what they’re doing is like, “Oh, Batman’s at the circus again and they have to find the bad guy.” And it bored me. But I would notice that the comics that always sort of stopped the wheel from turning, that I’d have to stop reading, were always Kirby comics. There was something he was doing that was storytelling on another level. His comics were still interesting fifty years later. [baby in audience starts babbling] Yeah, that’s what I’m saying. [laughter] That kid gets it. Yeah, there’s something about that. So I sort of understood that there was something deeper here. It was the storytelling. And once I saw that, I started revisiting Kirby, and I realized that he’s just like the foundation of modern pop culture society or whatever, and we don’t understand that because we’ve been in pop culture, so when we see the foundations, it gets a little confusing, because it’s raw and it’s tough.

And then just, to talk about what I’m doing now, DC came to me and said—I was like, “I just want something to do,” and they

5

said, “How about the New Gods?“ I go, “Oh my God, the New Gods? Yeah, I can tell these stories.” And my first thought was, you can’t out-Kirby Kirby. You just can’t do it. It’s impossible. I don’t have better ideas than him. I don’t have better dialogue than him. I don’t have that in my head. So what I do is, I try to bring out what was always in the artwork, which is that Kirby told these great, grandiose, galactic stories, and yet somehow they were always a metaphor for some inner personal conflict or a metaphor for—that’s what I saw. They were trying to get at something deeper, so I try to aim at that—instead of going bigger, I went underneath to try to dig at that stuff, because I find that aspect of him to be fascinating.

EVANIER: Okay. Walt, where did you discover Jack?

SIMONSON: I read comics as a kid. Where I grew up in College Park, Maryland, there were virtually no Marvel comics anywhere, there were no Atlas comics. The first comic I ever saw by Jack was an Atlas comic, from I don’t know which one of the monster books in the mid-Fifties. I was visiting my grandmother in Albia, Iowa, which is a long way from here, and there was a drug store beneath her apartment, it had a spinner rack, and there was a story called, “The Glob” or “The Blob,” I can’t remember. [Editor’s note: It was “The Glob” from Journey Into Mystery #72, Sept. 1961,

left.] And I’d never seen an Atlas comic, and it was drawn differently. It was colored differently. It was probably Jack—maybe Dick Ayers, I’m not sure who actually inked it. But it was a big rock statue, and a painter was hired by a bearded mad scientist, to come paint the statue with certain magical paints that he had to stir up, and there was the muddy glop that Jack could draw so beautifully, and he painted the statue. He was supposed to be out of there by midnight, and at midnight the statue awoke, and it turned out it was an alien spy from the center of the Earth. And I was like, “Really?” [laughter] And, as a kid, I was like, “Wow!” The castle was like a Frankenstein sort of thing, but the big blob was dripping this paint as it was chasing him, and finally the guy managed to get back to the paint room and grab a bucket of turpentine and throw it on him like Dorothy threw water on the Witch, and the paint all melts off. It didn’t occur to me at the time—later, I went, “So this would be the easiest alien invasion to thwart, ever.” [laughter] Just throw turpentine on it. It’s gonna be fine. But the art was fabulous! There was this Blob guy walking around. First of all, the old Atlas’ were kind of orange and brown. They were so weird. It was unlike anything else I’d ever seen, but I don’t know if there were credits there or not. A million years later, I’m in college, my freshman year. I’m in a dorm room with all my

6

[above] Jack incorporated what looks to be a lot of Egyptian and Mesopotamian imagery in this striking collage, circa 1970.

at that time. Jack clearly saw this guy as a god or as somebody above everybody else, and he said that. And I remember reading that, and that actually impacted me as a reader of that book, but also in the way I look at Superman, and why I’ve always tried to humanize Superman so much, because, without that humanity, people would fear him. And I think, in just a couple of panels, Jack set the tone for how people, within his story, here’s how they look at Superman. And it was just a groundbreaking thing to read that and go, “Oh, I get that, but I’d never thought of it before,” because we had George Reeves, or we had just this genial kind of version of him.

SIMONSON: Something else that I’ve seen in Jack’s work, it’s not very often discussed, a little bit here and there—[Jack’s] characters acted brilliantly in his stories. Mostly we talk about the power and the energy and whatever, but the acting in those stories is phenomenal, in terms of gestural quality. They’re still bigger than life a lot of times, but the scene Jerry’s referring to—at one point the champ and Clark Kent are discussing Superman, and he shakes Clark’s hand, and he says—I might be misremembering this. What I remember is, “That’s quite a grip you’ve got there, Kent,” and I think he may even be holding his hand like it’s sore. He’s holding his wrist… it was really just fantastic. It was a whole scene, just a beautiful moment of quietness, and yet it was still very powerful and did set the tone for Superman that was very different from the way he was treated elsewhere. And I think of Kanto in Mister Miracle when Mister Miracle goes back to Apokolips and meets Kanto, and Kanto is this guy who’s dressed in Renaissance garb, and bows and doffs his cap. You could imagine Errol Flynn playing this guy, in some costumed drama. But it had that grace. Even

with all Jack’s power, it had that grace and that observation of individual movement that gives character. So a lot of the writing was in the drawing, as well as in the actual words.

KING: Mister Miracle #3 is called “The Paranoid Pill,” and that’s not the proper way to use English, right? You’d say “The Paranoia Pill,” right? It’s the wrong noun/adjective thing, but somehow the Paranoid Pill, that hard D hitting that P, suddenly it becomes poetry.

[below] Pencils from Mister Miracle #6, showing the irresistible last panel verbiage that Tom King utilized in his own Mister Miracle series.

17

Sample Headline Eulogists Testimonials: February 7, 1994

Dick Ayers (1924–2014)

I didn’t see him that often. When I was doing Sky Masters, sometimes I would meet him at Grand Central Station and we’d have coffee together, but I didn’t know him socially. He was a very talented guy, y’know? I enjoyed his work very much when I inked it, at the point when Stan Lee told me not to trace; not to ink it just as he penciled it. He told me to really let myself go, and “do my thing.” He said if he wanted someone to just draw exactly and ink over his lines, he’d just pick up anybody who could trace off the street. Then I got to enjoy it very much, because his initial concept was always very exciting. His concept was terrific, and his design, but you had to really stretch your imagination on his anatomy. And his guns; when I did Rawhide Kid, I used to get upset because I like my Colt .45s and I want them to look like that, and the Winchester rifles and all of that. His handles were so bad on the pistols, that I’d redraw them. [laughter] But as I say, his concept was always exciting. Creative and prolific. He saved the industry, with Stan. Stan did the choosing; he pitted me with Jack, and it went from there. At that point, it was so dead, Stan looked at me one time and said, “It’s time to get off the ship. It’s sinking.” I was in the process of taking the exams with the Post Office, and I actually worked there a couple of weeks. I called him and said, “Well, it’s all over.” And Stan said, “Let me try something.” And he sent me a cover to ink, and then he sent me a horror story, and we were off! There was one point where I was doing the inking, and I wanted to do everything he turned out. It got to be like a game; I think it was clocking myself at about 100 pages a month. And then in addition, Sky Masters: To keep up with him, I had to ink all six dailies—I forget whether

I squeezed in the Sunday in the same day, in order to keep up with the other stuff.

Jack was so dependable. The work would always come right on time. He and I worked very good together, because we were both the same mentality. We always meet deadlines. There were no hang-ups with Jack; it just came right on time.

Don Heck (1929–1995)

I was just thinking about it. It sorta leaves an emptiness in you. He was super, something special.

To me, it’s sorta like losing a big brother. I was lucky enough to go out there last May—first time I ever went across country. I got to be with him up on a stage, and we had dinner together. Topps had paid for it; Jim Salicrup was there too.

I’m still shocked about it. I know he was sick, but still, with somebody like that, it’s sorta like Walt Disney or one of the other giants, that you figure will last forever. He was just terrific, and such a great innovator. He was probably the greatest innovator I’ve ever known. He could take just a normal thing, and expand on it, and take it to the limits. It’s hard for me to put it into words; he was just great. There won’t be anybody like him again. Both he and Stan Lee did more for comics than anybody. There’s no question about that. And all the people who are suddenly making all sorts of money, owe a lot to him; [laughter] whether or not they realize that, I don’t know. Some of the ones who really knew what the score is, do.

19

[above & below] Newly discovered filler panels (circa 1960) from Sky Masters; upper inked by Kirby, lower by Ayers.

[right] The Wasp gets her powers in this Don Heck-inked art from Tales to Astonish #44 (June 1963).

Conducted by phone by Will Murray, the day after Jack Kirby’s passing on February 6 at age 77 [These comments were copyedited by Will Murray and John Morrow, and excerpts were originally used for Will’s article in Comics Scene #42 (May 1994)]

[right] 2001: A Space Odyssey #7 (June 1977)

Beautifully and faithfully inked by Frank Giacoia—with only a tiny piece of wreckage deleted near the corner box—it seems Kirby deemed this a powerful cover pic that needed no verbiage. Editorial obviously disagreed. To my mind, what finally appeared in the two blurbs is right on the money, and perhaps inspired some new readers to give the title a try, so no harm done there. Kirby either felt the image strong enough without words (fair call) or perhaps he didn’t care, since this was to be the last of the stories themed this way before “Mister Machine” took center stage.

[next page] 2001: A Space Odyssey #9 (Aug. 1977)

Another cover faithfully, if quite heavily, inked by Frank Giacoia— the only change for this cover is the copy. And personally, I think “From out of the Monolith—the most awesome creation of all! Mister Machine!” (which is what was actually published) is better than what Jack suggested. A powerful and wonderfully designed cover for the second issue of a great series by Jack!

COVER COMPARISONS

24

A look at some editorial changes to Kirby’s work, by Shane Foley

Gallery

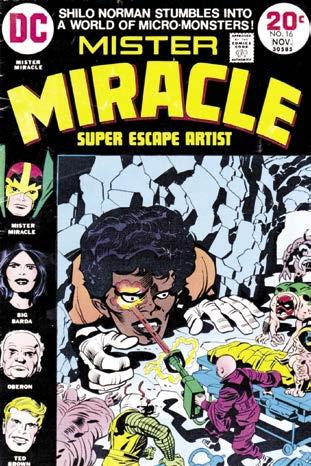

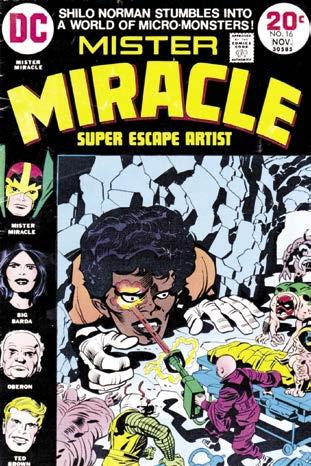

Mister Miracle #16 (Nov. 1973)

So what’s with Mister Miracle’s mask, Mister Kirby? I think it’s easy to explain. When an artist is producing a lot of product (as Kirby did), and when he’s going through an uninspiring period (as was happening here), these sorts of mistakes are bound to crop up. Why was Galactus wearing a Watcher-like toga in Thor #169 (page 14)? Surely because Kirby was jacked off with redrawing the whole thing (see TJKC #52) and his mind was only half on it. Look—the planet behind them isn’t even round!! Why is Mister Miracle’s mask wrong here? Because these Miracle stories were not what Kirby wanted to be doing, producing stories and characters (like Shilo Norman) that were shockingly inferior to the stories of a few months earlier. Sure, his art was still mostly great—but errors in detail like this slipped in. What other explanation could there be?

28

...from jumpsuits!

Incidental Iconography

largely came to Jack Kirby’s work in general via the Fantastic Four He had long since left the title when I first started reading it, but going through back issues, I found myself not only learning the

history of the characters, but also the power of Jack’s work. That said, though, I was immediately and strangely bothered by his drawing of the Invisible Girl right after she introduces the team’s new uniform. At the top of Fantastic Four #3, page [March 1962, left], she proudly displays her design for the first time, which is promptly followed by an extremely odd and uncomfortable close-up of her face. Why did Jack draw that? I didn’t like that panel at all, and it didn’t even make much sense from a design or layout perspective. It turns out there was a perfectly good reason for that weird close-up, and that’s what I’m covering in this issue.

As I noted last issue, Jack was surprisingly consistent with his Fantastic Four costume design once it was published, but there were a fair amount of modifications made while #3 was still being drawn! Some of this originally came to light when Greg Theakston was able to look at some of the original artwork to the issue back in the 1980s and, in his self-published Pure Images from 1990, included some penciled art he re-inked via a lightbox. The two stand-out revelations were that the costumes’ original chest insignia was two interlocked F’s instead of a number 4, and that the team also wore domino masks. That was why Jack included that strange close-up of Sue—she was putting on and showing off a mask!

Indeed, in reviewing the original art for the issue that has survived, page seven includes a fair amount of whiting out around Sue and Reed’s eyes for the entire page. However, none of the subsequent pages have this, or even indications that there were additional uninked pencils around the eyes. This would suggest that Jack drew masks on page seven, and had reconsidered the idea by page eight! (Theakston pointed out in his original notes about this that, indeed, masks would be useless for three of the four characters when using their powers, and may well have driven the decision.)

But that might not have been Jack’s idea. Throughout the art for the issue, there are plenty of notes from Stan Lee, well beyond his more typical suggestions in the margins for dialogue or minor art corrections. We have at least six pages in which Stan sketched page and panel layouts on the backs of the art boards. Obviously, these are very crude and quick sketches, but he was clearly providing some

I A big jump... 32

An ongoing analysis of Kirby’s visual shorthand, and how he inadvertently used it to develop his characters, by Sean Kleefeld

Approach Shots

by Dave Stevens, William Stout, and Barry Windsor-Smith

[There’s more than one way to skin a cat, as the saying goes. But doing so likely wouldn’t elicit as much outrage as a discussion of favorite Kirby inkers and their respective techniques in doing so. To wit: here are three artists who are masterful in their own work, discussing their own approaches to inking Kirby. Agree or not, we’ll bet the following will generate some vehement responses from fans reading this.]

Dave Stevens

“Jack really hasn’t changed his penciling since the 1950s, or as far back as you want to take it. His penciling’s still as good as it was then. He is one of these guys that has to have someone who under-

stands drawing. People assume all it takes is a technician to ink him. That anybody that can use a ruler can ink Jack, and that’s not true, I don’t think. They can ink him, but it’s not gonna look like anything. It’s gonna look like someone taking layouts and inking them straightaway, without any polish. Jack really deserves to have much better inking than he’s getting, to where people will round out his fingers, and will add a little to the hair and features and things like that, and get rid of all these [makes swishing sound] lines in the muscles, and things Jack doesn’t intend to have inked. Some of it, on metal and things like that, you add the sheen, naturally, but there’s all these jagged construction lines that people end up inking, and I’m sure Jack never intended to have that stuff inked. But it gets there; it’s all the way into the final stage.” [This was quoted from Dave’s 1980s video appearance at https://www.youtube. com/watch?v=tWqO83Zt3MM.]

William Stout

“I was asked to be one of the inkers for what is colloquially known as The Book of Roz. The Book of Roz (actual title Heroes and Villains) was a book of pencil drawings by Jack that he did for his beloved wife Roz. Jack drew just about every major character he ever touched in that volume—DC, Marvel, and all of the other comic book companies for which he worked.

“Most of the artists inked just one piece. I was asked to ink Devil Dinosaur (if you know my history, you know why I was picked for this character).

“Because of my previous work on The Demon (as a favor to my pal Mike Royer who wanted some much-needed family vacation time, I ghost-inked much of issue #15 of The Demon), I had previously inked Jack’s piece from Heroes and Villains illustrating The Demon just for fun and for myself.

34

[below] Fairly early in his comics career, a young Dave Stevens inked this Kirby drawing, utilizing many of the techniques he discusses here.

Thinkin’ ’bout Inkin’

Barry Forshaw

OBSCURA

by Barry Forshaw

DON’T OPEN THE BOX!

Which do you prefer: Jack Kirby’s work for Marvel or DC Comics? The former, of course, famously produced the Marvel superhero revolution, which continues to rule in terms of cinema adaptations, even today. But his DC work included the remarkable Fourth World series which may have sputtered out inconsequentially, but has proved as prodigious in its influence on both DC’s comics and their various film adaptations—with characters and concepts that are still doing service to this day (e.g. Darkseid), long after Kirby’s death. But let’s go back to the late 1950s and early 1960s, when the scenario was somewhat different. Before he began the series of Atlas/Marvel monster books that preceded the superhero period, Kirby was turning out a variety of exquisitely drawn fantasy and science-fiction tales for DC editors such as Jack Schiff in House of Secrets, Tales of the Unexpected, My Greatest Adventure, and others until the spectacular falling-out over a variety of issues that led to Kirby upping sticks and moving to the tender care of Stan Lee at DC’s rival—and drawing those gigantic worldtrashing creatures (mostly with inker Dick Ayers). In terms of the dramatic impact of his art, there is no denying the fact that the creatures that Kirby created for such titles as Tales to Astonish and Tales of Suspense allowed him to blossom in terms of striking, eye-catching creations with scenes that burst out of the panels in a way that was simply not possible in the more constrained environs of DC. However, there are those (including this writer) who actually prefer the DC SF fantasy tales, which largely avoided the deadening repetition that beset the Marvel monster books—each story at DC had

a different concept and didn’t simply end up in orgies of building-wrecking destruction and the death of the monstrous marauder. An example? Take “The Thing in the Box” from House of Mystery #61 (April 1957), the splash panel of which looks forward to the Marvel monsters: a gigantic green sea serpent, its mouth grotesquely extended, threatening a boat full of hapless sailors. This is classic Kirby, and not just for the bizarre monster of the kind that he always created so effortlessly—the human figure drawing has all the dynamism that we find in his DC work, such as his master shots of the Challengers of the Unknown Every member of that group was shown in a different energetic pose, and that’s the case with “The Thing in the Box”—but if you were to assume that the eponymous “thing” is the creature in the splash panel, you’d be wrong.

SPOILER ALERT!

Who is the typical reader of The Jack Kirby Collector? Is he or she familiar only with, say, Kirby’s lengthy run on Fantastic Four? Or his earlier work as discussed above?

I’m guessing we have a good mix of both, with a lot of readers like me who love all periods of The King’s career. But here’s another question: if you are reading an article like this, can I assume you are generally familiar with the stories being discussed? All of which is a preamble to my typing those two fateful words “spoiler alert,” as you may care to read the story before reading my following comments. The smallish chest which is dumped in the ocean at the beginning of “The Thing in the Box” issues forth a voice pleading: “N-no captain! Don’t do it! Don’t send me to the bottom! Please--I beg you!” The chest doesn’t look large enough to contain a human being, and the protagonist who retrieves the box from the sea is convinced that its occupant will be drowned. But in the process of retrieving it, there are some vividly demonstrated catastrophes—the green sea serpent mentioned above, and a plague of locusts. But what’s clever about the writing of this piece is that it’s discovered that the released horror is actually coming from a hole being drilled in the box—and the occupant of the container is no less than the legendary Pandora, whose box contains all the terrible evils of the universe. And it’s a particularly canny touch that the anonymous writer of the piece (might Kirby have been involved? Dave Wood?) chooses never to show us the occupant—Pandora is never released (no doubt good news for the world). The consummate skill in delineating this sixpage adventure is bristling with all the elements that would appear in Kirby’s later superhero work along with the giant monsters. But unlike those monsters, the reader is invited to think about what’s going on—and its more complex than Gagoom or Fin Fang Foom simply laying waste to all around them.

KIRBY’S FUTURISTIC CITIES

There is a recurrent theme in the work of Jack Kirby which admirers will be familiar with. It’s the futuristic city, crammed full of vertiginous angles, that makes an appearance in a variety of stories—perhaps the most spectacular version is the splash panel in the Challengers of the Unknown #4 story “The Wizard of Time”, in which the Challs take a trip to the far future. In that case, Kirby’s impeccable pencils were enhanced by the matchless inking

A regular column focusing on Kirby’s least known work,

38

Barry Forshaw is the author of Crime Fiction: A Reader’s Guide and American Noir (available from Amazon) and the editor of Crime Time (www.crimetime. co.uk); he lives in London.

Foundations

Here’s Simon & Kirby’s final “Flying Fool” story, “Peril Paradise” from Airboy Comics V4, #11 (Dec. 1947), with art reconstruction and coloring by Chris Fama. What would you like to see in future “Foundations” installments? Let us know!

Here’s Simon & Kirby’s final “Flying Fool” story, “Peril Paradise” from Airboy Comics V4, #11 (Dec. 1947), with art reconstruction and coloring by Chris Fama. What would you like to see in future “Foundations” installments? Let us know!

40

the Origins of Kirby’s Old New Gods Boom! THE SOURCE

[right] JFK and Jackie in a premonition of death from 1971’s Spirit World #1.

[below] Kirby’s original collage, and its disappointing printing in blue ink from Spirit World #1.

[next page, top] Yul Brenner and Charlton Heston from 1956’s The Ten Commandments meet Kirby’s Ramses and Highfather, alongside more Egyptian imagery from Spirit World #1.

THE SOURCE

by Richard Kolkman

[Editor’s note: The following essay served as a big part of the research that went in to producing TJKC #80’s “Old Gods & New” epic. I’m pleased to finally be able to present Richard Kolkman’s full work here, which does an amazing job of connecting and comparing Kirby inspirations and concepts throughout his career, and how they culminated in the Fourth World.]

T“The sky grew dark and the sun dropped to the horizon! From behind me, came the sound of a rifle shot!” his is how Spirit World #1 begins—with a breathless warning. For Jack Kirby’s entire career, he had the inscrutable knack for combining two diverse inspiration points and creating something timeless and uncanny. The Eternals is a perfect example: Kirby combined Greek mythology and Erich von Däniken’s book Chariots of the Gods (1968) into an epic of cosmic confrontation.

While researching the Jack Kirby Checklist for 25 years, it slowly dawned on me: Many aspects of Kirby’s Fourth World at DC Comics appeared to be steeped in ancient Egyptian history (The Hebrews) and the legacy of John F. Kennedy—in the aftermath of his untimely assassination.

The death of hope of the “New Frontier” was a cataclysmic shock to the American psyche—it affected everyone. Kirby admitted to Mark Evanier that the death of JFK had a profound impact upon his work. Instead of manifesting itself in the short-term, I believe it was a major thematic inspiration for Kirby’s Fourth World epic of the New Gods, and their battle to free themselves from oppression. The struggle of the ancient Hebrews to free themselves from Egyptian tyranny permeates the thematic ebbs and flows of the Hunger Dogs and New Genesis.

This deep dive into the headwaters of the Fourth World began when I read Robert Guffey’s essay “We All Live in Happyland” in Jack Kirby

Collector #57 in 2011. Mr. Guffey sensed that a JFK connection exists within Kirby’s Fourth World. I have come to second that notion. “The place to look for Kirby’s reaction to the JFK assassination lay not in his Marvel work of the 1960s, but in his most important work for DC Comics in the early 1970s.”—Robert Guffey

What I present here is all circumstantial evidence, but in its totality, becomes compelling. It begins firmly in the bedrock of the faithful... “There came a time when the old gods died.” (New Gods #1, March 1971).

In Spirit World #1 (Fall 1971), Dr. E. Leopold Maas’ premonition story is the nexus between spirits of ancient Egypt and the events in Dallas on November 22, 1963.

THE MOUNTAIN OF JUDGMENT

Ramses’ words ring out in righteous indignation: “It would take more than a man to free the slaves; it would take a god!” Indeed, Moses delivered the Jews from the tyranny of the Egyptian Pharaoh. With a staff like Highfather’s, Moses parted the Red Sea—an avenue of escape from Egyptian slavery. The mythos of the Hunger Dogs is grounded firmly in the Old Testament chapter of Exodus.

Slavery is an evil affront to life: “You’re dead as an individual. You have no choice. You can’t object and you

48

have no stature as a person. You’re dead. A slave is a dead man. That’s what Darkseid wants. Darkseid wants complete subjugation of everything at a word—his word. He wants every thinking thing under his control.” —Jack Kirby (Train of Thought #5, Feb. 1971).

Cecil B. DeMille’s epic film The Ten Commandments (1956) was screened for movie fans in a visually stunning new format: “Cinemascope has more dimension to it, more depth... the more lifelike it is, the more impressed you are with the image.”—Jack Kirby (1969). For years, The Ten Commandments was broadcast on ABC-TV every Easter. Watch it and listen carefully—it sounds and feels every bit like New Gods

The twin stone tablets brought down from Mt. Sinai by Moses were “commandments,” but they were always subject to man’s free will. The Source always represented the “Life Equation.” The hand of fire only guides us—it does not possess us. (Kirby’s character Dubbilex reminds me of the double-X: the two tablets that contain the Ten Commandments, X+X).

Ramses was Kirby’s original villain in his developing “New Gods” idea in 1966. Alternately known as the “Black Pharaoh” or the “Black Sphinx,” the concept art was ably inked by Don Heck. Kirby’s lineage of Pharaoh antagonists from the past can be laid out thusly:

• Challengers of the Unknown #4 (Nov. 1958). “The Wizard Of Time” features Pharaoh’s astrologer, Rhamis, his time machine, and a telescope he calls the “Cosmic Eye.”

• Tales of Suspense #44 (Aug. 1963)

“The Mad Pharaoh.” King Hatap comes out of suspended animation with his black arts knowledge to menace Iron Man. With a cover by Kirby and Ayers, the story art is by Don Heck, which gives him some rights to a Pharaoh villain in 1969’s X-Men.

• Fantastic Four #19 (Oct. 1963) “Prisoners Of The Pharaoh.” RamaTut descends in his time machine (The Sphinx) and rules ancient Egypt. His “Chariot of Time” also ties in with Dr. Doom’s time platform in issue #5 (July 1962).

• Ramses (concept art, 1966, above), Kirby’s original Fourth World villain (inked by Heck); Ramses wields an unidentified “Eye Weapon.” When Heck utilized the Pharaoh concept in X-Men #54–55 (March–April 1969) as the “Living Pharaoh”, he is diminished somewhat when Arnold Drake’s Iceman refers to Pharaoh as “Pyramid Poppa”! Perhaps this is why Kirby developed Darkseid as a serious replacement in 1969.

• And finally, Prester John [left] wields an “Evil Eye” after emerging from a centuries-long sleep in Fantastic Four #54 (Sept. 1966).

“I Am the Alpha and Omega” (Revelation 1:8 and 22:13). The beginning and the end of all things—Kirby played with this idea, first in Fantastic Four #82–83 (Jan.–Feb. 1969) when Dr. Doom’s “Alpha-Primitives” overwhelm the FF, and later as Highfather’s “Alpha Bullets” reclaim the Forever People in their issue #7 (March 1972).

The “Omega Effect” first occurs in Amazing Adventures #4 (Jan. 1971, right) when the Mandarin consigns his co-hort to oblivion—in exactly the same manner

49

Darkseid dispatches most of the Forever People in their issue #6 (Jan. 1972) and DeSaad in New Gods #11 (Nov. 1972). The leaping-off point to the juncture to everywhere was never more apparent.

When former Simon & Kirby Studio artist Carmine Infantino (who was then editorial director of National/ DC Comics) visited the Kirbys during Passover weekend in April 1969, he proffered a deal: Join us at National— all is forgiven (it’s a long story). Apparently, Infantino’s tastes didn’t align with his New York roots. According to Rosalind Kirby, “He came to the house on Passover, and I gave him matzo ball soup, and he hated it.”

Thematic parallels between Moses and Highfather

are apparent (a parent). They are the fathers and the deliverers of their people—as both tap into The Source.

THE OLD GODS

The rise of the Norse gods began with the Aesir! Buri, Borr, Odin, Thor, and Loki arose in the old world of Asgardian wonder.“Tales of Asgard” chronicled the rise and fall of Asgardian fortunes in Journey into Mystery #97–125 (Oct. 1963–Feb. 1966) and Thor #126–145 (March 1966–Oct. 1967).

From the beginning of his comic book career, Jack Kirby featured gods in his timeless tales: Mercury (later “Mokkari” in Jimmy Olsen), Hurricane (Son of Thor), Pluto, Apollo, and Diana the Huntress. Who can forget when Mercury addressed Jupiter (in street parlance), “It’s in the bag, all-wisest” in Red Raven Comics #1 (Aug. 1940)?

With the growing success of Marvel Comics in the 1960s, Kirby grew restless—he was never one to rest upon his laurels. In an endless cycle of re-invention, Kirby wanted to end and renew Thor. At Marvel, Stan Lee held to his editorial policy of “apparent” change—without actual change. Thor was one of the lucrative toy and product generators for the nascent Marvel, so Thor’s demise was out of the question.

Readers caught brief hints of Ragnarok in Journey into Mystery #119 (Aug. 1965) and #123 (Dec. 1965). When the end (and new beginning) finally unfolded in Thor #127–128 (April–May 1966), it was a speculative adventure. In “Aftermath,” we get a glimpse into New Genesis. A new golden age, a new rebirth is presented in Thor #128: “A life soon shared by the young, new race of gods which joyously takes domain over all it beholds... ”. The threat of Ragnarok again rears its deadly head in the legendary Thor #154–157 (July–Oct. 1968). When Kirby created concept art in 1966 for his re-imagined Asgard, he crafted Honir, Balduur, Heimdall, and Sigurd (Thor). [Enchantra] may have been part of this, also.

In 1966, Kirby stated, “... the characters of what I call the groovy Sixties... their trappings are different, they must be more showy.” Kirby was clearly ready to shake up the 1960s, and swing into a new decade. Since Kirby featured Ramses (Pharaoh) in his pantheon, how far behind were the other Egyptian gods? Ra—the Sun God, the God of Light—with a lineage to Balduur, and Lightray (of New Genesis)... was he a contender? Could Ra be the provisionally titled [Black of New Genesis]? (See TJKC #52’s cover.)

50

[below] Pencils from The Demon #16, page 17 (Jan. 1974).

legacy as a creator and storyteller is now assured—he now receives credit for his work. His family was compensated. There are no more funky roadblocks depriving Kirby of the credit that is his due. In his lifetime, he gained a large measure of respect from fan adulation, and the return of a portion of his original art from Marvel in 1987.

Captain Victory’s credo “Victory is Sacrifice,” I believe, is encoded in New Gods. Another of the archetypes from S.H.I.E.L.D.’s ESP division, is Victor Lanza. Victor is the befuddled, but brave insurance salesman who joins the others in “O’Ryan’s Gang.” Victor means victory. Lanza is German for Lancer. Lancer was the Secret Service’s code name for President Kennedy. Lancer was [a] sacrifice.

“Lincoln, Lanza, and company are not pawns of the gods. Instead, they are man’s sense of awareness of awesome and volatile forces around him.” —Jack Kirby (1974)

Finally—who is Harvey Lockman? A “lock” is the mechanism on a firearm that explodes the charge. He is Harvey Gunman. When the Warren Commission released their findings in September 1964 (at the same time “Millennium People” and New Gods were percolating), Kirby dove in: “I was given The Warren Report, which I read fully.” —Jack Kirby (Nov. 9, 1969). At 888 pages, it’s a lot to read. Perhaps there was an inspiration for “Harvey Gun(lock)man” somewhere in those pages?

Scott Fresina explained the members of O’Ryan’s Gang to Jerry Boyd: “... Jack’s group of humans that aided Orion—Dave Lincoln, Claudia Shane, Victor Lanza, and Harvey Lockman—were the types of enraged citizens that pay attention to events around them.” (TJKC #46)

I’m confident Kirby would also have read Death of a President by Manchester in 1967. Something fueled the sudden three-page saga of Jack Ruby in Esquire #402 (May 1967) by Berent/Kirby/Stone. (See TJKC #61)

(Do take this with a grain of salt: President Kennedy’s Lincoln Continental, in 1963, was given the designation “SS 100 - X” by the Secret Service; it’s in Manchester’s book. Ask yourself: why did Kirby’s first story for National/DC in 1970 [Forever People #1, March 1971] have the job number “X-100”? “In Search Of A Dream”—the Fourth World begs speculative interpretation.)

THE FALL OF CAMELOT

In Kennedy’s New Frontier, men seemed more efficient and brilliant, and the women more incredible and capable. It was a new beginn—er, Genesis. In relation to old Cold War thinking, the loss of President Kennedy was the loss of the country: “For a time, we felt the country was ours. Now its theirs again.” —Norman Mailer (1963)

“Don’t let it be forgot—that once there was a spot, for one brief, shining moment—that was know as ‘Camelot.’ —Alan Jay Lerner

Young heroes, against old odds. When the hope is pulled out from under you, you re-group and reformulate

65

[below] Big Bear does his part to fulfill the legend of King Arthur, in this pencil page from Forever People #7 (March 1972).

the narrative to fit the times ahead. “... .to shape or reshape [his] creations while their format is fluid.” —Jack Kirby (1972)

The loss of Kennedy weighed heavily on Kirby—it drove his major creation, as he explained to Mark Evanier. Spirit World #1 (Fall 1971) captures this unease (and again, it intersects with ancient Egypt on page five). How much stock do we put in our origins? The name “Kirby” comes from northern England. It’s two old Norse words “Kirkja” and “Byr”—meaning: “Church and Settlement.”

In the southwest of England, lies the county of Cornwall. It is here, that scholars have “chosen” as the site of the Castle Tintagel (the Roundtable) base of the legendary King Arthur. (Arthur was first mentioned in 800 AD by a historian named Nennius.) Arthur has never been exhumed—but what about his consort, Merlin?

According to Demon #1–2 (Sept.–Oct. 1972), Merlin’s Castle Branek is located in Moldavia (Moldova) in eastern Europe. Of course, it’s silly to treat this as an authentic, historic locale; but in the margins of history, lies the truth of authorship. If Kirby equated “Camelot” with the story of his Fourth World, its cancellation must

have been disconcerting. When Carmine Infantino called Kirby to cancel his most personal of books, it closed the book on a legendary mythology. In Demon #1’s text page “A Time To Build”, Kirby talks about his Fourth World characters coming back, after a period of stasis—in the future. This turned out to be true—Darkseid and the New Gods are a large part of DC’s current universe.

Check this out: If “Camelot” (Kennedy) is equated with (Orion) and the cancellation of the Fourth World, then its violent end in Demon #1 is especially noteworthy: “At a final sweep of Merlin’s hand, wondrous Camelot thundered, trembled, and departed from the pages of history.” Merlin’s “Eternity Book” is thusly sealed—until an opportune time in the future that it may be re-opened.

“Like the war between New Genesis and Apokolips, the character’s potential becomes locked in the tapestry, sinking and emerging and kept in static balance...” —Jack Kirby (Demon #1, Sept. 1972). Kirby understood that Darkseid and company would, one day, take center stage in the DC universe.

If Merlin’s body is ever exhumed—imagine he’s clutching the “Eternity Book,” and we know a fragment has been torn from that book: “Yarva Etrigan Daemonicus.”

“In the final analysis, the Fourth World could be about a nation coming to grips with its own Jungian shadow, a shadow that first reared its insubstantial visage for many Americans the day the old gods died on November 22, 1963.” —Robert Guffey (2011)

SACRIFICE IS CONTINUITY

The margins of history are written in by the few. We know Kirby wrote story notes in the margins of his Marvel stories, but what about the story notes Kirby wrote on the backs of his pages?

“I would write out the whole story on the back of every page. I would write the dialogue on the back; a description of what was going on.” —Jack Kirby (1989)

Margin notes could always be erased by the inkers, but what about the backs of the early Marvel original art pages? How much was created by Kirby? There are very few of these early pages in existence, so it’s hard to verify. Why was Atlas [Marvel] so close to shutting its doors until it exploded with success in the 1960s after Kirby and Ditko began “illustrating” stories? Often, in interviews, Kirby would make a verbal slip and refer to “my readers” when referring to the groovy Marvel comics loved by 1960s fandom.

At Kirby’s end at Marvel (with no hope of a contract with new owner Cadence), he was “conned and cajoled” into creating (and scripting) the Inhumans (Amazing Adventures #1–4, Aug. 1970–Jan. 1971). Ask yourself—when was Jack Kirby ever reticent to create comic book stories? Creating amazing stories was not the problem— receiving credit and major compensation for them, that was the problem.

When Kirby moved to DC, he had a voice. For the first time, the breadth of creation was his. It wasn’t until the ignominious cancellation of his Fourth World titles that his muse was interrupted. Kirby sacrificed his ego and his pride. America sacrificed its youthful leader—at the beginning of Winter, 1963.

Merlin takes center-stage on this Demon #5 splash page (Jan. 1973).

After the “Dog Days of Summer,” the Dog Star Sirius would rise in the night sky in ancient

66

Spot The Differences

by Dario Bressanini

Do you know the “Spot the differences” game? You are given two very similar images and you must find all the, however subtle, differences between them.

Avengers #1

September 1963 was the cover date for issue #1 of The Avengers cover and story art by Jack, of course. [above] Here on the left is its famous cover. Before going to print, Stan Lee ordered a small change in the cover art, as in countless other cases: he asked to hide part of Thor’s cape. The cover as originally drawn by Kirby was shown in an ad in Fantastic Four #18 [center] Fantastic Four at the time was Marvel’s flagship publication, and ads were meant to alert the readers to new comics coming out.

To me, Jack rendition of Thor’s cape seems better, showing its right side. Maybe Stan Lee wanted to leave some space around The Wasp?

When I was a kid, I used to read Marvel comics translated in Italian, starting in 1971. A few decades later I started reading the reprints of the original comics, and occasionally I was puzzled looking at the cover art. Something seemed wrong often there were small and sometimes subtle changes to the cover I had memorized, impressed in my mind by the countless times I reread those stories. At top right is the Italian print of the cover taken from my own collection. The Avengers in Italy did not have, at the time, their own book. Instead they were published as the second story of the book Il Mitico Thor (The Mighty Thor), a 48-page book with usually two fulllength stories and a short one, usually “Tales of Asgard.”

For this reason, the covers were often printed as the internal pages. And the version they printed in the Italian comic book was

the original cover as conceived by Kirby.

The same cover was later reprinted in the US in the Marvel Masterworks series.

Avengers #2

Below is Marvel’s house ad for The Avengers #2, and on the next page is the original cover (on the left) and the one reprinted in the Marvel Masterworks book (in the center). Can you spot the differences, apart from the different colors?

In the Marvel Masterworks cover (center):

1) The giant green arrow pointing at Giant Man is slightly bigger.

2) The blue sign above Thor is bigger, and touches the green arrow.

3) The right edge of the right window is slightly displaced to the right. It is hard to see, but notice that the bricks touching the window’s edge are shorter.

4) Although all the characters are identical, there is an additional shadow for the

Eyedunno 68

CAREER COMPARISON

Throughout a career spanning several decades, Jack Kirby maintained a level of high quality. Even though his style evolved and changed, the dynamism of his figures and his brilliant compositional abilities remained consistent.

For example, this 1941 Captain America #5 cover 1 is an fairly early usage of a combination of dynamic figure drawing and composition. Kirby’s work here is a bit primitive and cartoon-like, but underneath there is still a solid understanding of anatomy. He is also using somewhat realistic shading and has a clear grasp of the concept of light sources. Cap’s lithe and muscular figure dominates the page as he runs forward and down towards the Ringmaster and his minions. The shape and trajectory of his shield mirrors that of the Wheel of Death, and

IF YOU ENJOYED THIS PREVIEW, CLICK THE LINK TO ORDER THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DIGITAL FORMAT!

the sweep of that shape brings the eye to the sinister clown midget and the branding iron-wielding fiend with the swastika armband. The figures of the man in bondage and the bald knife holder behind him bring the reader’s eye back to Cap and Bucky, as Kirby is using the circular composition that he found to be so effective.

In 1954, still working with Joe Simon, Kirby brought us Fighting American. 2 On this page from the second issue, more than a dozen years after the first image, Kirby’s style is noticeably more realistic, both in its use of anatomy and shading. His use of the figure in space is much more adventurous at this point, as he has the body of the Fighting American moving contrapuntally. Notice that there is a slight difference between the torque of the rib barrel and that of the head and legs of this figure. The left arm is moving forward in forced perspective, while the right arm is stretching up and back. Kirby is using the orthogonal lines of the wall to accentuate the hero’s diagonal trajectory. In this instance, the artist uses the title lettering to bring attention to the figure, beginning with his right arm, while the left arm brings our focus to the man firing the machine gun. That character’s knee points to the figures on the table and then back again to Fighting American.

Two years later, Kirby was working for the company that,

73

1 2

(84-page FULL-COLOR magazine) $10.95 (Digital Edition) $4.99 https://twomorrows.com/index.php?main_page=product_info&cPath=98_57&products_id=1694

KIRBY COLLECTOR #86 VISUAL COMPARISONS! Analysis of unused vs. known Kirby covers and art, BARRY WINDSOR-SMITH on his stylizations in Captain America’s Bicentennial Battles, Kirby’s incorporation of real-life images in his work, WILL MURRAY’s conversations with top pros just after Jack’s passing, unused Mister Miracle cover inked by WALTER SIMONSON, and more! Edited by JOHN MORROW

Here’s Simon & Kirby’s final “Flying Fool” story, “Peril Paradise” from Airboy Comics V4, #11 (Dec. 1947), with art reconstruction and coloring by Chris Fama. What would you like to see in future “Foundations” installments? Let us know!

Here’s Simon & Kirby’s final “Flying Fool” story, “Peril Paradise” from Airboy Comics V4, #11 (Dec. 1947), with art reconstruction and coloring by Chris Fama. What would you like to see in future “Foundations” installments? Let us know!