®

by

Steven Alan Payne

Like many who clung from issue #1 to Marvel Comics’ Conan the Barbarian comic book which premiered in 1970, I had been a fan of the character since the late 1960s’ reprinting of the original Robert E. Howard tales. The path had already been beaten by Bantam Books, that served up hot-selling 95-cent reprints of the Lester Dent (nom de plume: Kenneth Robeson) Doc Savage and Avenger pulps. Sensing a good thing, failing Lancer Books issued a concurrent release of the Howard Conan tales, and the L. Sprague DeCamp and Lin Carter posthumous collaborations, with some pretty amazing Frazetta covers slapped onto them. I was hooked from day one. I was also repelled. This character from an age where distrust of your fellow man and fear of the unfamiliar was not paranoia but sound, defensive reasoning, often teetered on the brink of being something ugly. Being African American, I found the explicit and implicit racism a manifestation of everything that had limited me, and all that I railed against. It was an ugly reminder of the sensibilities that made my father’s life harder than it should have been, and made my mother fearful at times for her children. And there it was, in fantasy form, this Teutonic Nazi raging through his world with the power of life and death on the edge of his sword, decapitating, disemboweling, and venting a whole zeitgeist of rage on a race. Yet when brought to comic books, as a result of skillful writing, Conan never fell into the abyss. No mean feat, given the source material. Robert E. Howard was a storyteller. His writing style may not have the introspective clarity of a Don DeLillo, but he could compellingly spin a yarn and deliver a phrase that could chill to the bone. Conan’s world was a barbaric one, where kingdoms were formed out of fear of their neighbor, and trust was an often fatal weakness. Prejudice was simply common sense. Howard’s tales’ habitual and demeaning reference to Blacks was as insane beasts, cannibals, and leering lechers. In tales like “Shadows in Zamboula” or “The Vale of Lost Women,” or his opus, “The Queen of the Black Coast,” Blacks were there to lend the “barbaric splendor” at best, or at worse be the inhuman monsters slavering before the helpless, or sometimes bending to the dominating White female. To his credit, writer Roy Thomas kept the Conan comic-book adaptations true to the flavor of the original stories, in all their color, vibrancy, barbarism, chauvinism, and, yes, racism, while ameliorating the more offensive elements in a manner that didn’t dampen the stories’ intent or flow. Thomas had an Olympic-level sense of balance as he keep intact Conan’s world—the chief element that separated Howard’s barbarian from any of a hundred other bare-chested pre-historic swordsmen—while not offending the sensibilities of a world just coming to grips with its heterogeneous legacy. Marvel Comics in the 1960s had, in small and large ways, done a lot to distinguish itself as being ahead of the curve in racial awareness. Steve Ditko’s inclusion of Black characters in panel backgrounds of The Amazing Spider-Man—as police officers, as fellow students at Peter Parker’s school—were small gestures, but noteworthy for their casualness. And on the big side of the scale, how about the Black Panther, who, in his first appearance in Fantastic Four #52, took the FF to a sound defeat. The Panther was a liberal’s “missing link,” this cobbled-together Piltdown Man. He was the African Black, untouched by White genes, who was the equal of any White man. He was the justification of the civil-rights struggle. And he was the moral backbone that made Marvel Comics more than just another comic-book company.

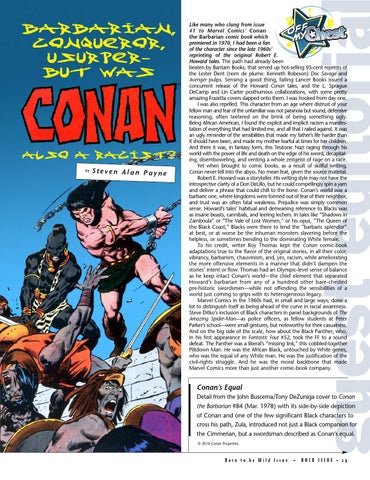

Conan’s Equal Detail from the John Buscema/Tony DeZuniga cover to Conan the Barbarian #84 (Mar. 1978) with its side-by-side depiction of Conan and one of the few significant Black characters to cross his path, Zula, introduced not just a Black companion for the Cimmerian, but a swordsman described as Conan’s equal. © 2010 Conan Properties.

Born to be Wild Issue

•

BACK ISSUE • 29