$10.95 In the USA No. 183 Sept. 2023 1 8 2 6 5 8 0 0 4 9 9 6 IRV NOVICK A STAR-STUDDED SALUTE TO GOLDEN/SILVER/BRONZE AGE GREAT by JOHN COATES & DEWEY CASSELL FROM MLJ’s SHIELD & STEEL STERLING TO BATMAN, THE FLASH, & SOME OF DC’s MOST MEMORABLE WAR COMICS! IRV NOVICK Roy Thomas’ hangin’-Tough ComiCs Fanzine TM & © Archie Comic Publications, Inc.

Vol.

Editor

3, No. 183 Sept. 2023

Roy Thomas

Associate Editor

Jim Amash

Design & Layout

Christopher Day

Consulting Editor

John Morrow

FCA Editor

P.C. Hamerlinck

Mark Lewis (Cover Coordinator)

Comic Crypt Editor

Michael T. Gilbert

Editorial Honor Roll

Jerry G. Bails (founder)

Ronn Foss, Biljo White

Mike Friedrich, Bill Schelly

Proofreaders

William J. Dowlding

David Baldy

Cover Artist & Colorist

Irv Novick

With Special Thanks to:

Heidi Amash

Richard J. Arndt

Bob Bailey

Jean Bails

Sy Barry

Cary Bates

Jim Beard

Bonnie Biro

Dewey Cassell

Paul Castiglia

Mike Catron

John Cimino

Shaun Clancy

John Coates

Comic Book Plus (website)

Jon B. Cooke

Chet Cox

Brian Cronin

Stephen Donnelly

Michael Dunne

Mark Evanier

George Fears

Shane Foley

Leslie Novick Frank

Jeff Gelb

Jatinder Ghataora

Frank Giella

Janet Gilbert

Penny Gold

Grand Comics Database

Mike Grell

Paul Handler

Heritage Art Auctions

Mike Jackson

Sharon Karibian

David Karoll

Nick Katradis

Jim Kealy

Henry Kujawa

Paul Levitz

Art Lortie

Michael Lovitz

Jim Ludwig

Brian K. Morris

Mark Muller

Kim Novick

Wayne Novick

Denise Ortell

Joe Petrilak

Rune Rasmussen

Ralph Reese

James Rosen

Bob Rozakis

Randy Sargent

Pierangelo Serafin

David Siegel

Robin Snyder

Brian Stewart

Bryan Stroud

Dann Thomas

John Wells

Eddy Zeno

John Coates & Dewey Cassell’s in-depth coverage of a major comicbook artist.

Ralph Reese tells Michael T. Gilbert of his apprenticeship with the great Wally Wood. FCA [Fawcett Collectors Of America] #242 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 73

P.C. Hamerlinck showcases Shaun Clancy on “The Whiz Bang Life of Captain Billy.”

On Our Cover: Some years ago, our featured artist Irv Novick seems to have made a gift of his original cover art for Pep Comics #17 (July 1941)—the issue that introduced the sinister new masked hero The Hangman—to his fellow MLJ artist Ed Goggin. Far as we know, Irv even provided the coloring. While his work on Batman, The Flash, and DC’s war comics has reached more readers over the ensuing decades, authors/providers John Coates and Dewey Cassell and Alter Ego’s erudite editor conferred with TwoMorrows Publisher John Morrow… and the decision was made that the pulsating Pep cover should front this issue! Our thanks to Heritage Art Auctions for the pristine scan! [TM & © Archie Comic Publications, Inc.]

Above: Penciler Irv Novick, inker Dick Giordano, and writer Denny O’Neil restored Catwoman’s glamorous 1940s garb in this story done for Batman #266 (Aug. 1975). Of course, editor Julius Schwartz might’ve had something to do with that decision as well. [TM & © DC Comics.]

Alter Ego TM issue 183, September 2023 (ISSN 1932-6890) is published bi-monthly by TwoMorrows Publishing, 10407 Bedfordtown Drive, Raleigh, NC 27614, USA. Phone: (919) 449-0344. Periodicals postage paid at Raleigh, NC. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to Alter Ego, c /o TwoMorrows, 10407 Bedfordtown Drive, Raleigh, NC 27614. Roy Thomas, Editor. John Morrow, Publisher. Alter Ego Editorial Offices: 32 Bluebird Trail, St. Matthews, SC 29135, USA. Fax: (803) 826-6501; e-mail: roydann@ntinet.com. Send subscription funds to TwoMorrows, NOT to the editorial offices. Six-issue subscriptions: $73 US, $111 Elsewhere, $29 Digital Only. All characters are © their respective companies. All material ©their creators unless otherwise noted. All editorial matter © Roy Thomas. Alter Ego is a TM of Roy & Dann Thomas. FCA is a TM of P.C. Hamerlinck. Printed in China. FIRST PRINTING.

(website)

This issue is dedicated to the memory of Irv Novick Contents Writer/Editorial: Introduction By John Coates . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2 Irv Novick: A Heroes’ Ar tist . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3

Mr . Monster’s Comic Crypt! “My Life With Wood” (Part

65

1) . .

IRV NOVICK: A Heroes’ Artist

by John Coates &

by John Coates &

Dewey Cassell

Foreword

by Denny O’Neil

Hush, step over here, out of the light. I’ve a secret for you. But I won’t reveal it yet, not until I’ve compelled you to slog through about 462 words of questionable prose...

Our subject is M. Irv Novick. You may know him as an artist who draws Batman.

Elsewhere in this excellent volume, you can learn that Batman has been plying his trade, which is entertaining you by righteously, cleverly apprehending lawbreakers—call them “villains.” This he has been doing for, as I write this, 80 years, ever since his debut in 1939 in Detective Comics Popular guy? I’ll say! Listen, Batman has been featured in every medium that can be made to tell stories. Radio, television, movies, novels, drama, short fiction, roller coasters! (no kidding), bubble gum cards (still not kidding)! Did I mention theatre? Well, brace yourself for full disclosure: Although there hasn’t been a Batman Broadway musical yet, at least one has been proposed, and the day is young yet.

...Something I’m forgetting...

Oh yeah. Comicbooks. Batman’s corporate parent, DC Comics, has just published the one thousandth issue of Detective Comics. Let me lay that out in numbers: 1,000 consecutive comics! Has any other periodical, apart from news venues, achieved that record? And, beginning with issue #27, every one of them has featured a “Batman” story. Not exactly the same Batman: our hero, like the great literary characters—Hamlet comes to mind, as does Sherlock Holmes—is subject to interpretation; different creators see him different ways,

Which brings us to the true subject of these observations: Irv Novick, comicbook artist, and if you want to emphasize the “artist” part of that sobriquet, okay. Here’s something you may not understand: comicbook art is more than a collection of pictures sharing the same space. (Are you sensing a secret in the air?) It is integral to the story being told. The comics characters’ body language, expression, placement within the panel, distance from the imaginary “camera”—the reader’s eyes—all this and more is part of the information that shapes the story. Part of the narrative.

Together Again!

The earliest iteration of “The Bat-Man,” as he was sometimes known, was a tad effete, a bit soft around the edges, like Ellery Queen and such other fictional detectives as Hercule Poirot and Philo Vance. He evolved swiftly during the World War II years and although, back then, he wasn’t completely consistent from story to story, he was most often like the version Irv Novick and his collaborators presented to readers. In a word: hero. Tough, but never cruel or vicious, Smart, but never arrogant; responsible but not smug... a virtual tourist attraction. (”Mommy, can we go to Gotham City and see Batman and Robin?”) He was cheerful, but not a wiseacre, a good citizen who never cheated on his taxes. And not only was he all those commendable things—thanks to Mr. Novick, he looked like them. Excellent match of talents.

Recently, a Hollywood guy who has directed a super-hero flick or two told the world—smugly?—that Superman and Batman kill. He then advised us to “live with it.”

So: secret. No, they don’t. At least my Superman and Batman don’t. And I’ll bet that Irv Novick’s don’t, either.

3

—Denny O’Neil, 2019

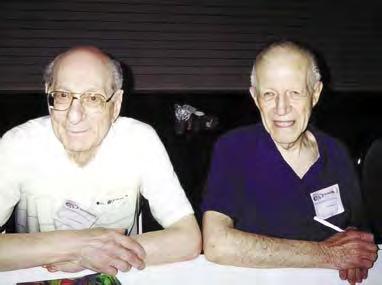

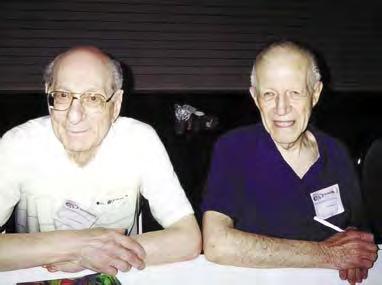

Although Denny O’Neil passed some months after writing the accompanying foreword, it’s more than fitting to feature his image along with those of two of his collaborators on this splash page from Batman #240 (March 1972). (Left to right in photos:) editor Julius Schwartz and penciler Irv Novick at a turn-of-the-century comics convention, and Denny O’Neil, circa 1971. They were aided and abetted by inker Dick Giordano. Thanks to Jim Ludwig & Jim Keally. Unless otherwise noted, all images accompanying this abridged book are courtesy of authors John Coates & Dewey Cassell. [Page TM & © DC Comics.]

Denny O’Neil

Julius Schwartz & Irv Novick

Chapter One Formative Years

There is no better place to start, especially for readers who may not be familiar with Irv Novick, than at the beginning. In his in-depth 1998 interview with Novick, which weaves its way throughout this issue, John Coates talks to the artist about his career in comics and elsewhere, including where he came from and how he got his start. (This interview was previously published in The Comic Book Marketplace #77, April 2000.)

JOHN COATES: Mr. Novick… I’d like to thank you for agreeing to this interview

IRV NOVICK: Mr. “Who,” John? Hey, rule #1 is that you can’t call me “Mr. Novick.” My name is Irv. Got it? [laughter]

JC: Forgive me. The curse of being brought up in the South. [laughter]. Now, let’s begin with your family background.

NOVICK: Well, I was born in New York City on April 11, 1916. My father was in the fur business and fairly wealthy. He had about 100 people working for him. He was a good businessman and a good father.

He even made money during the Depression, which was quite a feat. My mother was a very thoughtful, loving person. She always encouraged us to read when we were young, and both were very supportive of us getting an education. She used to read to us, and we had learned to read even before we were taught to do so in school. As far as my first interest in drawing, my mother used to say that I scratched her womb with a pencil! [laughter] My art inspirations were many: Alex Raymond, Rembrandt, Van Gogh, Winslow Homer, the classics, some contemporary artists, everyday life, etc.... Listen, if you’re an artist, you’re going to be influenced by a good many people and things. Anyone who says otherwise is a liar, or a fool!

Not Exactly Medical School!

JC: Did your family support your decision to be an artist?

NOVICK: Oh yes. However, I do remember

“The Shield Of The Mighty”

that my mother’s brother used to drag me down to the hospital to watch surgery. He thought I was going to go to medical school, but I took the exam for the National Academy of Design in New York City instead. Boy, was he surprised! [laughter]

The Academy was like a four-year college, but they didn’t give out degrees. No art schools gave degrees in those days. However, after four years, many graduates taught at universities without a master’s degree or having taken education classes. To get in, you had to first pass an art examination. If you passed, they would then make you come back and ask you to draw from casts/statues for about two weeks. If they still liked your work, then they offered you a scholarship. Around 1933 I received a four-year scholarship and an additional year for my master class. We were affiliated with Columbia University so we could take advantage of many of their resources.

JC: What was your first professional assignment?

NOVICK: While at the Academy, I saw an ad on the school bulletin board for someone to do “showcards” for an importing company which had consignment space in most of the large department stores throughout the country. The showcard was part of a department store floor display that showed a woman, usually a beautiful woman, well, always a beautiful woman, using whatever kitchen gadget the display was presenting. For example, a beautiful woman would be shown in a kitchen using a potato peeler, and an

4 A Star-Studded Salute To A Golden/Silver/Bronze Age Great

Irv Novick as a young man at his omnipresent drawing board… and his cover for MLJ’s Pep Comics #9 (Nov. 1940), nearly a year into “The Shield” but still some months before the debut of Simon & Kirby’s (and Timely’s) Captain America Comics #1. Thanks to the Grand Comics Database for the cover scan. [TM & © Archie Comic Publications, Inc.]

Life, as John Lennon famously said, is what happens to you while you’re busy making other plans. So Irv wound up first attending the National Academy of Design in New York City, instead of studying to become a doctor.

Irv Novick

as a child when I had rheumatic fever.

Anyway, during this time, MLJ would send me work at the Army base. Instead of playing cards like all the other guys did, I sat on my bunk and drew comicbooks. Sometimes the guys would stop playing cards for a minute or so, come by and look over my shoulder, ask questions, and then go back to playing cards. If any of the guys read my books, I never knew. At the end of each month, I would get this check from MLJ. Somebody from HQ always opened my mail, because you could see that it contained a check. Army pay being what it was, everybody on base was trying to borrow money from me. I was very popular, if you know what I mean. Some did borrow money, though I never got paid back. That was the end of that! [laughter]

The 1930s and ’40s proved a couple of things to Irv Novick. One, he clearly had the talent and creativity to be successful as a comicbook artist. But, two, being first out of the gate did not necessarily lead to long-term eminence. While noteworthy in its own right, the early success of The Shield would ultimately be eclipsed by the endurance and popularity of another patriotic hero—Captain America. So, the time came to move on to bigger and better things.

Chapter Three The 1950s

As World War II drew to a close and the soldiers returned home, it was a time of prosperity for the United States. The end of the war meant a fresh start for many veterans, among them Irv Novick. For him, the approaching decade of the ’50s ushered in a life-long friendship as well as a life-long association with National Periodical Publications, better known today as DC Comics.

It was also a time of branching out. Virtually every comicbook artist aspired to having their own daily newspaper strip. A strip meant much wider exposure and a good, steady income. Advertising and other forms of commercial art further broadened the horizon. But the lure of comics was still strong.

And, as the country geared up for entering another war in Korea, and then in the years that followed, DC Comics boasted the strongest stable of war-related comics, including what became collectively known as its “Big Five” in that genre: Our Fighting Forces, All-American Men of War, Star Spangled War Stories, G.I. Combat, and Our Army at War. They were a perfect fit for the realistic and detailed style of Irv Novick.

8 A Star-Studded Salute To A Golden/Silver/Bronze Age Great

“Let’s Get Together, Yeah, Yeah, Yeah…”

Team-ups were common on the covers of MLJ comics, if not inside the mags themselves. Novick drew the buddy shots on those of Shield-Wizard Comics #1 (July 1940) and Jackpot Comics #7 (Fall 1942). On the latter, the Supermanpowered Steel Sterling shared space with the Batman-like Black Hood. Courtesy of Comic Book Plus. [TM & © Archie Comic Publications, Inc.]

DC’s Manhattan offices]. When we lived in the Bronx, I got paid a quarter or 50¢ round trip to take the work downtown. I thought I was such hot s**t. I’d get dressed up. I must’ve been 10 or 11. I would get on the subway from the Bronx. Then, that area went through such devastation, but I never cared. I’d show up and Carmine was always gracious and so was Julie. “Where’s your father? Why isn’t he here?” “He couldn’t; he’s working.” [chuckles] “Where are the rest of the pages?” “I’ll bring them tomorrow.”

JC: Kim also mentioned the Kanighers. Bob Kanigher always said your dad was one of his favorite artists, and your dad said the same about Kanigher as a writer/editor.

LESLIE: They knew each other very well. Bob was particularly good-looking and charming. He was the first person I knew who had a convertible. I remember being aware of him in 1959 when we moved to Dobbs Ferry. He would take his kids for rides and they’d have to use the bathroom, so our house became the “Novick service station.” Bob was there every weekend. His wife Bernice became a mentor to me. I don’t think I would’ve gotten out of high school if it weren’t for her. She was really smart. She had been a high school principal in the Bronx. I think it was Grace Dodge, but I’m not sure. Our families were really, really close. I babysat for their kids. Actually, their daughter just died and their son is a policeman in New York state.

JC: Do you have any other memories of Carmine Infantino?

LESLIE: Some people said very negative things about him. He was a change agent—he mixed stuff up at DC. My dad liked him. And he

was always kind to me; he was always well dressed. He always gave me a hug. He was a good-looking Italian guy!

JC: Actually, he’s very well-remembered and respected, not only as an artist, but, looking back through the lens of reflection—he was a change agent. Some of the negative projected onto him when he was publisher was coming from his boss. As publisher, Carmine did a lot for artists’ rights and creativity, so there were a lot of people who were very happy with him.

LESLIE: I liked him.

JC: In the late 1950s/early 1960s your father left DC Comics for a short time for the Johnstone and Cushing advertising agency. To bring him back, DC offered him the unprecedented freelance agreement guaranteeing him work. Any insight?

LESLIE: I know Joe Kubert was involved, and somebody else—they brought an intellectual property lawsuit and got the rights to their original work. So, anytime any of Irv’s work is used, we get royalties. Yes, I think it must’ve been in the late 1950s or early ’60s, because he went from being a freelancer to being an exclusive-contract artist with a minimum guarantee of pages they had to give him. He was paid well by page or project and also given benefits and a pension.

JC: Unheard-of in the industry, even today.

LESLIE: Right. I think he and Joe Kubert and the other guy got it as part of the settlement. They [also] brought a lawsuit against the IRS because they were paying unincorporated business taxes. They weren’t incorporated. I remember something about that, but not the

16 A Star-Studded

To A

Salute

Golden/Silver/Bronze Age Great

This Means War!

Two Novick war covers that may have been produced under the regime of art director Carmine Infantino: All-American Men of War #117 (Aug. 1966), which may be a little early… and Our Fighting Forces #113 (May-June ’68). Courtesy of the GCD. [TM & © DC Comics.]

Carmine Infantino

Noted as a comicbook illustrator, Infantino became DC’s art director in late 1966, later becoming the company’s editorial director, then publisher, through the mid-1970s.

specifics. I thought it was a cool thing, and they eventually didn’t have to pay unincorporated taxes. They were also guaranteed X amount of work because they were exclusive.

Do you know Irwin Hasen? Irwin and my dad were very good friends.

JC: I had the pleasure of meeting Irwin a few years ago. He was made for the convention circuit. Fans embraced him. Did your dad encourage you to be creative?

LESLIE: Yes. I liked to draw. He sent me to the Museum of Modern Art to take art classes. He’d take me down every Saturday morning. We would go to the museums as a family. I took art classes at the local Y, and I majored in design in college. I guess I’m not as bad an illustrator as I thought I was. Somebody sent me a page from my high school yearbook that I had illustrated. I had no recollection of ever doing it. [chuckles]

JC: There’s a dedication; you have to have to sit and draw. You mentioned Cynthia . Did your dad ever mention any other jobs? People of my generation always call it a “comic” or “cartoon,” but people of his generation call it a “job.”

LESLIE: He always called it a “job.” He did Boy’s Life and the “Bible” page and a lot of stuff for them. He did a lot of illustrated ads. In the 1950s, when photography came in, illustration went out. That was the driver for him becoming solely a cartoonist, because there was no work for big illustrations.

JC: As far as his painting, is that something he did throughout his life?

LESLIE: He did it when he was in college. He didn’t have a place to paint when we lived in the city… and he didn’t go back to it for a long time. He missed it. Every once in a while, he’d do something in Dobbs Ferry. I think he was conflicted about where to go with it. He tried abstraction. I didn’t like it, but Kim has a big painting. He gave it to me and I gave it to Kim. It’s really, really big and I still don’t like it.

You know Con-Ed in New York? They do public works and work in holes in the streets. He did this Con-Ed painting, and it’s pretty powerful and illustrative, but he never went back to the portrait or landscape work he did. I have a painting of a kid down the block in the Bronx that he grew up on. The Frome family were his neighbors and he did a portrait of their son and I’ve got that. I think he was 17 when he did it. People look at it and go, “Oh, my God. That’s beautiful.” Even at Fort Shelby, he would do portraits, while sitting and waiting for something, of other soldiers. I found ten of them about six or seven years ago. They all have their IDs on them or their last names. I was able to locate, through Fort Shelby, some of the families. Two of them never came back. I sent the families copies of the originals. He was really good at portraits. It’s exemplified in the way he drew his characters.

JC: He has such a distinctive style. He was one of the first artists that, when I was reading a comic, I would say, “Oh, that’s an Irv Novick.” You mentioned his sense of humor and your mother, too. He seems like an open, humble person.

LESLIE: He was really the best parent to me. He didn’t have a mean bone in his body. They were both welcoming to everybody and we grew up color-blind. Didn’t matter who they were. They both had a sense of humor—not a quick sense, but they would say funny things. I can’t tell you how many of my high school and college friends—if they were in town, they would stop at my parents’ house to see them. We were long gone! They just wanted to see how they were doing.

When my dad was in a nursing home for the last two years, my friends would go visit him because they just adored him. He

was interesting, cantankerous; he was a liberal but he wanted to know. I would come into his studio when he was working and he’d be listening to Rush Limbaugh. “Why are you listening to this?” “I want to know.” If he was in a conversation and somebody started talking about something and it was getting boring, he would take the opposite side to mix it up and make it more interesting.

They were both curious about the world and encouraged us not to sit idle and to always give back. I broke my arm—fell off my bike at seven or eight. They took me to the doctor, got a hard cast and were told I had to do physical therapy. You didn’t go to an actual physical therapist then. I had to make potholders from these stretchy things you put on a loom and weave in and out. I made hundreds of these things. I wanted to get better fast. So I have all these potholders. My mother decided I’m going to sell them and raise money for March of Dimes. My dad makes the sign and he takes me down to Central Park West and the 81st Street entrance. He sat me on the bench with the sign. I had on a short-sleeve shirt so my cast showed. He sat a little farther down, and because I was this little kid, I sold these things. I was so embarrassed, John. I still have the letter from March of Dimes thanking me—I think it was $15!

JC: Great teaching moment! At the end of his career in comics, did he want to retire or was it more like DC saying, “We’ll help you out the door”?

17 Irv Novick: A Heroes’ Artist

Wash-ing Out The Sea Devils

Irv Novick’s “wash” cover for Sea Devils #14 (Sept.-Oct. 1963). That particular effect on DC’s cover in that era was usually added by production manager Sol Harrison and his crew. [TM & © DC Comics.]

A Star-Studded Salute To A Golden/Silver/Bronze Age Great

“Pop!” Goes The Weasel

A clockwise look at a pop art (and comicbook) controversy:

In this composite, pop artist Roy Lichtenstein is juxtaposed with his famous/infamous “WHAAM!” painting that utilized a comicbook panel drawn by Irv Novick. Photos from the Internet. [Art & photo TM & © the respective trademark & copyright holders.]

Irv Novick’s original panel, from the Johnny Cloud story “The Star Jockey” in All-American Men of War #89 (Jan.-Feb. 1962) Scripter uncertain. [TM & © DC Comics.]

artist Dave Gibbons’ visual comment on Lichtenstein’s “artwork,” done for a print. Note that Dave added Novick’s name to the art. [Based on artwork TM & © DC Comics.]

In his book Of Comics and Men: A Cultural History of American Comic Books (University Press of Mississippi, 2009, p. 350), author Jean-Paul Gabilliet calls into question the account of Novick’s interaction with Lichtenstein, saying that Lichtenstein had left the Army a year before the time Novick says the incident took place. However, as noted in the conversations in this book, Novick’s children substantiate the story as Irv told it.

John Romita, one of the DC romance artists whose work had been appropriated, recalled the furor in an interview conducted by Cefn Ridout and Richard Ashford for the book The Art of John Romita (Marvel Comics, 1996): “A lot of the guys—Bernie Sachs and a few others—wanted to get together and file a class action suit against Lichtenstein and some of the other artists. I was not too interested. I said, first of all, I don’t want to contribute money to lawyers. I didn’t want to get involved in it. I even foolishly told them that I was somehow flattered by the fact that they would consider these panels so good that they felt it was worthy of a painting. And, of course, they thought I was crazy. ‘‘Flattered?! They’re ripping you off!’ I never felt ripped off. I felt like it was a different art form. I wished they would say ‘from a drawing by…,’ but they never did.”

Three decades later, Romita imagined that he and his fellow artists might finally get a measure of respect when they were invited to an exhibition at New York’s Museum of Modern Art that contrasted their original art with the paintings. Instead, the group was faced with a show entitled “High and Low” and speakers who looked down on the entire comics form. “They invited me there proudly, never knowing that I thought I was insulted,” Romita

sighed. “I walked out of there right after dinner. I didn’t want to hear any more speeches. I was just so hurt by the whole thing.” (Ridout & Ashford, pp. 29- 30)

The end of the decade of the 1960s saw the end of the age of innocence. Between politics, the Vietnam War, and the civil rights movement, people were eager for a new way of thinking. Enter the Bronze Age of Comics.

24

Watchmen

A Conversation with WAYNE NOVICK

Wayne Novick is the oldest son of Irv and Sylvia Novick. In this candid interview, Wayne shares his own recollections about Irv and what it was like growing up with an artist for a father.

JC: It’s a real thrill for my co-author and me to discuss your dad with his family. We’ve been fans of your dad all our lives.

WAYNE NOVICK: I’ve met many people who are fans of my dad’s work and fans of other comic artists, as well. Where are you from?

JC: I’m from Columbia, South Carolina.

WAYNE: I know it well. After I was drafted, I did my basic at Fort Jackson [SC]. I made friends with people at the University [of South Carolina]. I would get a weekend pass, but I didn’t go to the bars and get drunk—I’d go to the library, which was a unique thing at the base. The base library was not really well-stocked. In 1968, the coffee shops were anti-war and leaned to the left.

JC: Small world! Leslie said you’re the second oldest of the Novick kids.

“Riding Through The Glen…”

WAYNE: Yes, I’m 72. My sister Leslie is the oldest by three years, and then my two brothers are each three years younger than each of us. Three down to Jan, and three down to Kim. Kim was the baby; Jan was the middle one. I’ve always said, “I’m proud to be part of a pair of middle children, so we have double the problems of middle children.” [chuckles]

JC: I can relate to Kim. I’m also the baby in my family! So, tell me a little about your father.

WAYNE: He was born in New York City in 1916. I honestly don’t know whether he was born in the Bronx or Manhattan. My [maternal] grandparents were both from Eastern Europe. Difficult to say Poland, Romania, or Russia—because of the Bolsheviks and the Red and the Whites—the border changed on a weekly basis. My grandmother identified not as a Polish Jew, but as a Jewish person who happened to live in Poland. My grandfather was the same, but he would speak about Russia. They were both from the border regions. My grandfather identified as a Menshevik, which was another fringe group at that time.

From all the stories I hear, which may not be true, they met in Central Park and were political activists. My grandfather leaned left (as do I) and was a labor activist. He owned his own business up until

25 Irv Novick: A Heroes’ Artist

Warhorse

An offbeat Johnny Cloud cover by Novick, this one for All-American Men of War #105 (Sept.-Oct. 1964). [TM & © DC Comics.]

When Robin Hood replaced The Golden Gladiator with The Brave and the Bold #12 (June-July 1957), Irv Novick was tapped to draw the cover, even though Russ Heath drew the new feature inside. Irv, of course, was still busy doing “The Silent Knight.” [TM & © DC Comics.]

Spotlight On… THE BATMAN

A common misperception is that it was writer Denny O’Neil and artist Neal Adams who first portrayed a darker version of the Caped Crusader. The truth is that the Batman that Bob Kane created with Bill Finger, who first appeared in Detective Comics #27, was already a dark character. That first story in 1939 depicted a man who was stabbed to death, and another man being shot and killed. At the end of the story, “The Bat-man” knocks the villain into a tank of acid, calling it “a fitting end for his kind.”

As the years progressed and Batman was joined by his sidekick Robin, the stories became lighter in tone. By the late 1960s, the Batman comics were as campy as their television counterpart. But it still wasn’t O’Neil and Adams who began the return to a darker interpretation of Batman. It was Frank Robbins and Irv Novick who ushered Robin off to college and closed up Wayne Manor and the Batcave in favor of a penthouse apartment at Wayne Foundation. So began the “creature of the night” era, in which Batman fought more common gangsters than costumed super-villains.

In their book The Batcave Companion (TwoMorrows 2009),

authors Michael Eury and Michael Kronenberg observed about Novick: “Starting in 1968 and running throughout the 1970s, the artist who drew the most stories in Batman and Detective Comics was veteran penciler Irv Novick. Novick penciled the first story in Batman’s continuity change, ‘One Bullet Too Many,’ appearing in Batman #217 (Dec 1969). Throughout the ’70s he illustrated some of the Caped Crusader’s most memorable stories. He drew the Bronze Age revivals of Catwoman and The Penguin and co-created the villains the Ten-Eyed Man, Colonel Sulphur, and The Spook. The prolific artist also worked on many of Robin’s solo stories in the back pages of Batman and Detective.”

Novick drew 17 covers and 15 stories for Detective Comics. By contrast, he drew 78 stories in the pages of Batman over the span of 13 years, but only 12 covers. He also drew Batman in other titles,

38 A Star-Studded Salute To A Golden/Silver/Bronze Age Great

Frank Robbins

was both an artist and a writer, originally on his popular newspaper strip Johnny Hazzard—and, in the later ’60s and early ’70s, wrote and/or drew “Batman” adventures as well. He scripted this one for Batman #236 (Nov. 1971), which was penciled by Novick and inked by Giordano. Seen here is the autographed original art of the splash page. [TM & © DC Comics.]

Put On A Happy Face!

such as Brave and the Bold. Combined, it represents thousands of hours spent drawing the Caped Crusader. It’s no wonder Batman is the character for which Novick is best remembered.

Novick’s art depicted a tall, imposing figure in Batman and his alter ego Bruce Wayne. He had a commanding presence, but could be vulnerable as well. Novick’s layouts were dynamic and creative, and action sequences seemed like they might leap right out of the page. It’s not a surprise that his style was well received by most fans.

Spotlight On… THE JOKER

The mid-1970s was the era of the comicbook villain. Marvel Comics launched the title Super-Villain Team-Up and Fireside

published Stan Lee’s Bring On the Bad Guys, while DC Comics debuted the Secret Society of Super-Villains and a solo title based on perhaps the most famous villain of all: The Joker.

Why all the focus on the bad guys? Well, truthfully, it was often the bad guys who made the heroes more interesting. The villains were complex characters, frequently with tragic origins that made them sympathetic. But while the Fantastic Four appeared in a comicbook every month, Doctor Doom sat idle between his battles with that quartet. So, when publishers were looking for new ways to leverage their stable of characters and expand their roster of titles, turning to the villains was a logical move, and none more so than The Joker.

When DC Comics decided to launch a bi-monthly comic headlined by “the Clown Prince of Crime”—the first comicbook series to feature a villain as the title character—they turned to veteran “Batman” artist Irv Novick to draw it. He had proven ability drawing the Caped Crusader and his nemesis, rendering The Joker in the style Neal Adams had popularized a few years earlier.

The debut issue featured The Joker escaping from Arkham Asylum and endeavoring to outwit fellow Batman villain Two-Face. The two bad guys end up knocking each other out at the end of the story and are

39 Irv Novick: A Heroes’ Artist

The Joker’s On Us!

The Novick full-art splash page for the previously unpublished story produced for The Joker #10 in the 1970s was first seen in The Joker: The Bronze Age Omnibus (2019). Script by Marty Pasko, with an assist from Paul Kupperberg. Thanks to David Karoll. [TM & © DC Comics.]

The final page from the final issue of the first DC The Joker series, printed from a copy of the original art: #9, Sept.-Oct. 1976. Inks by Tex Blaisdell; script by Elliot Maggin. [TM & © DC Comics.]

captured by the police. In the second issue, The Joker helps Willy the Weeper overcome his remorse from stealing, only to be caught again by Commissioner Gordon at the end of the story. While the premise is somewhat silly, make no mistake: This is not the Cesar Romero Joker of the Batman television show. The Joker uses acid on his enemies in the first issue, and in the second tosses someone who betrays him into an incinerator.

For reasons unknown, Novick did not draw the next two issues of The Joker, but returned as regular penciler with #5. Over the next several issues, The Joker squared off against a variety of characters, including the Royal Flush Gang, Lex Luthor, The Scarecrow, Catwoman, even Sherlock Holmes. But after nine issues, The Joker was canceled, presumably due to sales, or lack thereof. Some of the other comics featuring villains lasted longer, but all ultimately succumbed to the same fate.

Therein lies the challenge in having a comicbook starring a villain. DC couldn’t have The Joker fight Batman in every issue, or it becomes just another Batman comic. Nor did they want to turn him into a hero. And since he is ultimately a villain, he needs to face justice for his crimes, or so said the Comics Code. In the end, the villain needs the hero as much as the hero needs the villain. As The Joker said to Batman in the film The Dark Knight, “You complete me.”

There are two other contributions Irv Novick made to the annals of Joker history. First, a tenth issue of The Joker was completed but never published at the time, due to the title’s cancelation. According to the Grand Comics Database, the synopsis of the story is: “When an Arkham doctor orders that Joker undergo psycho-therapy to remove his pathological tendencies, the Joker makes a deal with the devil to avoid his fate. The deal he makes is to kill the JLA.” In notes about the story, which was written by Marty Pasko, the GCD adds: “This was to be the first part of a two- or three-part story according to Pasko, but only this first part was completed.” The tale was finally published in The Joker: The Bronze Age Omnibus.

Second, the sixth issue of Batman Family introduced “The Joker’s Daughter,” later revealed to be Duela Dent. Appearing to be a female version of The Joker, she uses gimmicks like a powder puff and lipstick bullets against Robin. (See p. 56.) She later takes

Keyed For Speed

the name Harlequin and joins the Teen Titans for a time. The character co-created by Novick has persisted over the years, in one form or another, though she is not actually The Joker’s daughter.

Spotlight On… THE FLASH

Having proved his capabilities illustrating Batman, Novick was given the responsibility of penciling another major DC super-hero: The Flash. The character’s Silver Age co-developer, Carmine Infantino, had been promoted to art director for DC Comics; and, after a brief stint in the hands of Ross Andru, the

40 A Star-Studded Salute To A Golden/Silver/Bronze Age Great

The Flash splash—for #223 (Sept.-Oct. 1973). Script by Bates; inks by Giordano. [TM & © DC Comics.]

Scarlet Speedster was handed off to Novick in 1970. One could argue this was as much a curse as a blessing. Infantino had co-created the Silver Age Flash, so following in his footsteps invited comparison, but Novick proved up to the task.

In the book The Flash Companion (TwoMorrows Publishing, 2008), Jim Beard notes, “Novick did not so much ape his popular predecessor, but most definitely emulated him. Novick’s feel for architecture and the skyscape of Central City, the Flash’s home, were very much inspired by Infantino, as was his eye for panoramic landscapes and creative panel structure. His figures were lanky at times, accurate in anatomy, yet also heroically proportioned. Novick created a look for Barry Allen and his wife Iris that would define them for years to come, yet also rooting them in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s as relatively ‘hip’ citizens of their fictional Central City. Their clothes and hairstyles were current to the times and felt ‘real,’ and the Allen home became a comfortable hang-out that inside and out would make Flash fans feel welcome.”

Over the nine years Novick penciled the comic, he often

41 Irv Novick: A Heroes’ Artist

Bates & Switch

(Above:) Cary Bates wrote the great, great majority of the issues of The Flash penciled by Irv Novick over approximately a decade—and even got himself included in the story in issue #228 (July-Aug. 1974). Inks by Tex Blaisdell.

(Right:) Splash page by Bates, Novick, & McLaughlin from The Flash #244 (Sept. 1976). [TM & © DC Comics.]

Cary Bates

illustrated The Flash taking on his Rogues Gallery of villains, including the Weather Wizard, Captain Cold, Mirror Master, The Trickster, Abra Kadabra, Captain Boomerang, Heat Wave, and The Pied Piper, among others. Novick is remembered for co-creating the beautiful Golden Glider, the younger sister of Captain Cold, in The Flash #250. She blamed The Flash for the death of her coach and boyfriend (and fellow Rogue) The Top. Novick also co-created The Clown.

65

(Above left:) Wally Wood self-portrait from Marvel’s “Flight Into Fear!” in Tower of Shadows #5 (May 1970). [TM & © Marvel Characters, Inc.]

(Above right:) Ralph Reese’s self-portrait featuring many of the characters he’s drawn, plus one of his mentor, Wally Wood. [© 2023 Ralph Reese]

My Life With Wood… (Part 1)

by Ralph Reese

Ifirst met Wally Wood in 1966 when I was a sixteen-year-old runaway, on the lam from a juvenile detention facility in New York. Two of my friends from the High School of Art and Design, which I had attended intermittently, were Larry Hama and J.D. Smith. We were all fledgling comicbook fans and had made a few trips together to King Features and places like that after school, where we would hang around and pester people and try to get an idea of how things were actually done. At that time, I had no great ambition to be a comic artist myself--I was actually more into mechanical drawing or maybe industrial design.

Anyway, when I got in some trouble and found myself needing a place to stay, Larry and J.D. introduced me to Larry Ivie, who at that time was in his mid-twenties and a sort of semi-pro artist who put together a magazine/fanzine called Larry Ivie’s Monsters and Heroes, published by Kable Pubs. Larry had an apartment on the West Side of Manhattan and was well known in the fan community, which was at that time quite small, and would sometimes let other fans from out of town crash with him when they came to New York. To make a long story short, he agreed to let me stay there for a little while, as I looked for some sort of work.

In

Ivie had quite an extensive comicbook collection, and introduced me to EC Comics, which I had never seen or heard of, as well as the whole world of comic fandom as it was then. I discovered all the classics: Raymond, Foster, Crandall, Frazetta, Williamson, and Wood. It was then that it occurred to me that real people were actually making a living at this, and that it might be something I could do. It was the Wood and Williamson science-fiction stuff that really inspired me. I liked super-heroes okay and read my share of FF and Spider-Man, but never had a great desire to draw them.

At this time Wood was still doing some inking for Marvel and had tried out Larry Ivie as an assistant. I’m not sure how they got to know each other, but at that time comics was a pretty small world and Larry had been a Big-Name-Fan ever since the EC days. For one reason and another, that assistantship didn’t work out, but I did manage to persuade Ivie to introduce me to Wood, who lived only a few blocks away and was at that time looking to expand his studio to take on more work.

“Don’t Call Me Wally!”

I was completely forthright with WW about my situation and of my great admiration for his work, and he offered to try me out

66 Mr. Monster’s Comic Crypt!

Monsters And Heroes

The Ivie League Reese’s pal Larry Ivie painted the cover to the first issue of his magazine Larry Ivie’s Monsters and Heroes, in 1967. [TM & © Larry Ivie.]

Joe Cool!

(Above:) A dapper Ralph Reese in 1966.

(Below:) A nerdier version, from 1968, as seen in Comic Book Creator #17 [© Estate of Bhob Stewart.]

Larry Ivie

The Whiz Bang Life Of CAPTAIN BILLY

by Shaun Clancy

Edited by P.C. Hamerlinck

by Shaun Clancy

Edited by P.C. Hamerlinck

FCA EDITOR’S INTRODUCTION: Without the Captain, there wouldn’t have been the Captain!

Wilford (Billy) Hamilton Fawcett of Robbinsdale, Minnesota, had launched an enterprise in 1919 that became a national sensation: Captain Billy’s Whiz Bang was a monthly magazine of suggestive jokes, anecdotes, and scantily clad (for the times) ladies—all for only 25 cents at newsstands. Fawcett Publishing [a.k.a. Fawcett Publications] was born!

By 1922, 400,000 copies a month of Fawcett magazines were being circulated worldwide. As the company continued to grow, they eventually relocated to the East Coast, where a new Captain would be created just a few years later.

Captain Billy Fawcett on the Empress of Australia ocean liner, as he takes a trip around the world during the 1930s— flanked by two of his greatest early successes, only one of which he stuck around long enough to fully appreciate: an early issue of the joke magazine Capt. Billy’s Whiz Bang, dated Aug. 1920… and C.C. Beck’s cover for the Fawcett company’s Whiz Comics #2 (Feb. 1940), the first issue having been a mere ashcan edition. [TM & © the respective copyright holders; Shazam hero TM & © DC Comics.]

On the following pages, Shaun Clancy dives into the details of Fawcett family history and Wilford’s remarkable life. At the age of 16, young Billy ran away from his Grand Forks, North Dakota, home and joined the US Army in time to see action in the Philippines Insurrection of 1899. He later joined the Minnesota National Guard, after being hired as a newspaper reporter at the Minneapolis Journal. When World War I came along, Fawcett again served his country overseas, being promoted from an enlisted man to the rank of Captain.

Captain Billy returned to civilian life, opening a Minneapolis nightclub before the arrival of Prohibition in 1919 put him out of business. (Prohibition would go into full force in January 1920, but apparently the Captain could read the handwriting on the

75 The Fabulous Fawcett Family – Part II

Captain Billy & A Pair Of Whiz Bangs!

saloon wall.) What venture could he try next? He wanted to give the doughboys of WWI something to laugh about. Why not a joke magazine? Taking his own name, and adding to it the sound of artillery shells rocketing through the skies over the trenches in France’s No Man’s Land before ultimately exploding, he christened the magazine

Captain Billy’s Whiz Bang

.

It took $500 in 1919 for Billy to produce Whiz Bang from his home in Robbinsdale. By 1923, the Captain’s income was $45,000 a month, with his magazine’s circulation closing in on half a million—all accomplished without ever carrying advertising within its pages. From Whiz Bang’s earnings, he released other magazines … True Confessions … Modern Mechanix … even imitations of Whiz Bang itself, such as Smokehouse Monthly, For Men, and Hooey.

His publishing company continued to grow, as did Captain Billy’s fame and prominence. He traveled the world and hobnobbed with statesmen, royalty, and celebrities. With his newfound higher social status, the Captain invited other elite friends and acquaintances to his luxury lakeside lodge at Breezy Point Resort in northern Minnesota. (Read about those tales of the Captain in our next issue.)

While dark days hindered American businesses during the Great Depression, Fawcett Publications thrived, and by 1936 had pulled up the stakes in Minnesota for larger headquarters in Connecticut and New York. However, in that same prosperous year, they did suffer one casualty: Whiz Bang. The magazine’s style of humor had run its course and the public began looking for new forms of entertainment… one being a new thing called a “comicbook.”

In December of 1939, Fawcett’s Captain Marvel debuted in Whiz Comics. Two months later in Hollywood, at the age of 57, a fatal heart attack marked Captain Billy’s final adventure. While he lived long enough to see the first appearance of the World’s Mightiest Mortal, he never got to witness the full triumphant success of the comicbook super-hero. Whiz Comics was, in essence, a wholesome extension of Whiz Bang. The “Whiz Bang Days” annual festival still held in Robbinsdale, Minnesota, is a wistful reminder of the Fawcett publishing empire from a bygone era … one that began with one big Whiz Bang from Captain Billy.

—P.C. Hamerlinck

—P.C. Hamerlinck

Wi lford (Billy) Hamilton Fawcett was born in Brantford, Ontario, Canada, to Maria B. Neilson (1859-1913) and John Fawcett (1849-1915), a physician, on April 29, 1885. The Fawcetts had a total of eight children, with the other seven siblings being: Roscoe Allan Fawcett, Clarence G. Fawcett, Harry (Harvey) R. Fawcett, John (Jack) W. Fawcett, and sisters Maria Eva Fawcett and Margaret (Peggy) F. Fawcett/Conner. They had a brother, Gordon N. Fawcett, who died at two years old (1881-1883).

The Fawcett Family—1902

Billy Fawcett married Claire Viva Meyers (b. 1886) in 1907; the couple eventually divorced in 1920. They had a total of five children: Wilford Hamilton Fawcett Jr. (1908-1970) and his twin sister Miriam (Marian) Claire Fawcett (1908-1993), Roger Knowlton Fawcett (1909-1979), Gordon Wesley Fawcett (1911-1993), and Roscoe Kent Fawcett (1913-1999).

After two years of marriage, the Fawcett family moved to St. Paul, Minnesota, where Billy worked as a clerk at the Railway Mail Service. He soon gave up that job to work as a cub reporter at the Minneapolis Tribune before once again joining the US Army on November 27, 1917, as a captain. He was stationed as a 3rd Instructor at the Officers Training School in Lyon Springs, Texas, before being transferred on December 19, 1917, to the 3rd Motor Mechanical Regiment at Camp Hancock, Georgia. He was once again transferred on May 20, 1918, to the Central Officers Training School in Camp Lee, Virginia. He was honorably discharged on November 25, 1918. While in the service, and because of his experience at the Minneapolis Tribune, he worked on the military Stars and Stripes and adopted the nickname “Captain Billy,” which he used for the remainder of his life.

Upon re-entering civilian life, he tried his hand at running a bar called the Army and Navy Club located in downtown Minneapolis. Unfortunately for Captain Billy, Prohibition was about to become the law of the land, and in 1919 he was forced to close the doors. His next business venture was one that was on his mind for a while. He had pitched the idea of a men’s humor magazine to several friends but could not convince others to invest in it, so the family of Fawcetts decided to fund it themselves. Here’s how Billy described that experience in his own words, which he published in Capt. Billy’s Whiz Bang, dated October 1920, in his “Drippings From The Fawcett” column:

(84-page

Three years after Wilford Fawcett, Jr., was born, they relocated to the United States in 1888 and lived in North Dakota. At age 16, Billy decided to run away from home and join the Army. According to his Military Record paperwork, he entered the US Army on January 25, 1902, and was discharged January 30, 1905. He re-enlisted on February 13, 1906 and was once again discharged on December 8, 1906. While in his first tour of duty, he spent two years in the Philippines during the Philippine-American War, where he was injured—undoubtedly the reason why he was not in the service for a year from 1905-1906.

Two years ago Capt. Billy’s Whiz Bang exploded pedigreed bunk, junk, or whatever you might wish to call it, with the idea in mind that Ye Editor might be able to inject a little more humor into our rural community of Robbinsdale. The printer told us it would be as cheap to

https://twomorrows.com/index.php?main_page=product_info&cPath=98_55&products_id=1689

76 Fawcett Collectors Of America

A turn-of-the-century family portrait. Front row: Mrs. John Fawcett (mother), Clarence Fawcett, Maria Eva Fawcett. Second row: Capt. Wilford H. Fawcett, Harvey Fawcett, Dr. John Fawcett (father). Third row: John (Jack) Fawcett, Margaret (Peggy) Fawcett, Capt. Roscoe Fawcett. Note: A brother named Gordon died at 2 years old.

IF YOU ENJOYED THIS PREVIEW, CLICK THE LINK TO ORDER THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DIGITAL FORMAT!

ALTER EGO #183

Golden/Silver/Bronze Age artist IRV NOVICK (Shield, Steel Sterling, Batman, The Flash, and DC war stories) is immortalized by JOHN COATES and DEWEY CASSELL. Interviews with Irv and family members, tributes by DENNY O’NEIL and PAUL LEVITZ, Irv’s involvement with painter ROY LICHTENSTEIN (who used Novick’s work in his paintings), Mr. Monster, FCA, and more!

FULL-COLOR magazine) $10.95 (Digital Edition) $4.99

by John Coates &

by John Coates &

by Shaun Clancy

Edited by P.C. Hamerlinck

by Shaun Clancy

Edited by P.C. Hamerlinck

—P.C. Hamerlinck

—P.C. Hamerlinck