Monuments and memorials have been the focus of contentious national conversations due to, at least in part, who and what they honor, and how their design memorializes the truth or fiction of our collective past. Professors and students from the Tulane School of Architecture and Department of Psychology collaborated to share research methods and develop new courses that focus on public space and memory. This publication highlights our investigation of existing monuments and exploration into more just and equitable spaces in New Orleans and beyond.

Public Space & Monuments

Copyright 2025

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without prior consent of the publishers.

The views and opinions expressed in the content of this book are those of the contributors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the publisher, the SOM Foundation, or Tulane University.

Every reasonable attempt has been made to identify owners of copyright. Errors or omissions will be corrected in subsequent editions.

PUBLISHER

DISTRIBUTION

Cover Design: Tiffany Lin

Cover Illustration: Malina Pickard

Memorial, Monument, Public Memory

Layered Histories, Conflict

Commemoration

Vestige, Testament

Renaming, Removing, Dismantling

Toppling, Mourning, Healing

Tragedy, Atrocity, Grief

Guilt, Morality, Fragility, Emotion

Reconciliation, Renewal

Public Space & Monuments

Diversity, Activism, Engagement

Fragility, Emotion, Community

Bias, Prejudice, Discrimination

Racism, Stigma

Affirmation

Authority, Power

Oppression

Freedom of Speech

Social Justice

Reconciliation

Citizenship

TIFFANY LIN, AIA

Associate Professor of Architecture

Design Program Director

LISA MOLIX, Ph.D

Associate Professor of Psychology

Department of Psychology

EMILIE TAYLOR WELTY, AIA

Architecture Professor of Practice

Architecture Program Director

Introduction | Sue Mobley

Project Overview

Research Seminar

National Survey

Research Studio

Exhibition

Precedents

Local Transformation

Typologies

Nola Monument Catalog

Reflection | Edson Cabalfin

| Emily Captiville

Introduction

As Director of Research and co-author of Monument Lab’s National Monument Audit, I often joke, when presenting our findings, that the American monument landscape is overwhelmingly statues of white, wealthy men, which you already know, if you’ve ever been outside. More seriously, I point to the Audit as a snapshot, a starting point for understanding the monument landscape we’ve inherited, but one which requires a much broader range of research to engage local conditions and imagine new monument landscapes. Which is why I was thrilled to see, and to participate, in this research, which offers new insights into New Orleans’ monuments and the spaces they occupy in our city and society, as well as the perspectives of those who are being educated to shape those spaces. Through experiment and investigation, Public Space & Monuments draws on far more than our recent interrogations into monuments and memorials; connecting threads of all three authors’ exceptional bodies of work in their respective fields to engage more deeply with how we understand, inhabit, and shape the places around us.

The How Do We Remember exhibit was an innovative approach to refining students skills and playing to their strengths while also challenging standard models for public engagement. We understand monuments and memorials differently when we

remove them from their pedestals, as is clear from the flurry of interest around each statue removed or altered in recent years, there are no points in a monument’s existence where we are more interested in the people and politics represented through its presence in our public spaces than when it is erected or when it is removed. When you line them up on the wall, monuments are no longer static and silent objects signaling veneration, and can be engaged with a far greater range of response, evoking curiosity, concern, compassion, and even contempt. If, as one survey respondent posited, “the monument bears the memory of

the city and the will of the nation,” curiosity might lead us is to questions of why the city’s memory is borne in the celebration of those who overthrew the municipal police and government, and what nation’s will venerates the president of a treasonous insurrection against it? Concern might raise questions of how our nation’s will is shaped by the preponderance of war and violence celebrated in our public spaces. Compassion wonders what inspiration might we be expected to take, what lessons might we learn or not learn from standing so persistently and overwhelmingly in awe of singular white men? And contempt, whether there is any hope for repair or progress within a landscape so marked?

Those are questions about monuments, but they are questions about design and design education as well, for those who take on the vocation of shaping our built environment are also shaped by it. If we need our landscapes: natural, built, social to evolve, then there are lessons that must be unlearned. As the authors found, students who were, “able to witness and participate in true dialogue with the community that resulted in a necessary outcome—a pause on the project—rather than a short-sighted move to barrel forward without considering the consequences.” How might our built environment benefit from more pauses like this? From occasions of dialogue outside of

formal processes? How might humility, reflection, and inclusion serve as guiding principles for a design education that serves a broad and complex network of publics?

The differences between non-designers and designers on what is important in public space is a pain point, and an area for growth. That designers surveyed high on measures of social hierarchy and dominance should come as no more surprise to anyone who’s ever entered an architecture school then the prevalence of statues of white men on war horses should to anyone who’s ever entered an American town square. Traditional design education selects for and reinforces social dominance, but engaged design and interdisciplinary research offer approaches to design education that better meet our collective needs. If we want public memorials that reflect a multiracial democracy, then we need diverse participation in their making and democratic processes in their design. As the Audit was a launching point for research into the monument landscape, I hope that Public Space and Scrutiny serves as a model for interdisciplinary design education that can challenge a growing politics of hostility towards diversity, equity, and inclusion.

Sue Mobley urbanist, organizer, and advocate Director of Research at Monument Lab

Across the United States, monuments that honor racist or socially inequitable histories are being toppled as communities imagine more inclusive public spaces. Within this context, an interdisciplinary team of researchers, comprised of two architects and a social psychologist from Tulane University, collaborated to improve our understanding of how perceptions of existent monuments can influence the design of new forms of commemoration in New Orleans. This project, originally titled, Public Space and Scrutiny: Examing Monuments through Social Psychology, was sponsored by the 2020 SOM Foundation Research Prize. The team conducted a national survey to investigate public opinions of existing monuments, and led a research seminar and design studio to explore new forms of collective memory on a local site historically marked by racial injustice. The research team and students wove the data and design speculations into a public exhibition entitled:

How Do We Remember?

We were inspired by the rising movement to question the relevance and legitimacy of monuments and memorials in public spaces, particularly in the context of protests against racial injustice. National Geographic photographer Kris Graves has powerfully documented these monuments as public stage sets— sites of both resistance and rallying points for those advocating their preservation or removal.

1. Christopher Columbus statue. Richmond, VA. Photo by Kris Graves

2. Francis Scott Key monument, Baltimore, MD. 2017 Photo by Eli Pousson

3. Abram Ryan monument. 2017 Photo by Bart Everson

4. Robert E. Lee monument removal. 2017 Photo by Information of New Orleans

5. Confederate General Stuart statue of. Richmond, VA. Photo by Kris Graves

6. Jefferson Davis monument. New Orleans, LA. 2004. Photo by Bart Everson

Overview

Monuments have been the focus of national conversations and contention because of who and what they honor, and how their designs memorialize or elide the truth of our collective past. Monuments and memorials in public spaces, particularly those that honor a legacy of racial injustice, have become public stages on which communities have expressed the need for social change. They are the backdrops for rallies to either keep or remove these contested objects. Protesting, vandalizing and monument removal has taken place throughout the city of New Orleans. The city now has the opportunity to reimagine, reframe, and recontextualize its collective history.

This research team identified a need in both the data collection and the practical work governing these opportunities. Although conversations surrounding public memory and social justice are becoming integrated into design pedagogy and practice, very little of the empirical work on the recontextualization of public spaces has included the voices of the communities in which these spaces exist. Furthermore, the architecture profession does not typically reflect the communities for whom public spaces are designed. This interdisciplinary research project examines differences in perceptions of public monuments and aims to equip designers with the skill set to engage with communities

to create equitable, inclusive, and historically accurate forms of collective commemoration. With the support of an SOM Foundation research grant, the team conducted: (1) a research seminar, (2) a national survey, and (3) a design/ build studio with a community partner that resulted in a public exhibition.

Our team collaboration draws from each of our existing programs of research and teaching, extending our expertise in the areas of social identities, bias and intergroup stress (Molix), design pedagogy (Lin), and community engagement and design/build implementation (Welty).

Project Timelie

Research Seminar

Through the execution of this project, the research team defined, as a key outcome, the cooperative development of a set of tools for use in the reconceptualization of contested public spaces. To this end, we conducted an architecture seminar in the fall of 2021 that invited students to examine existing public spaces, monuments, and memorials and to collaborate on developing a framework for future design. The course introduced students to the diverse interdisciplinary perspectives necessary to inform and then create such a framework. For example, students learned fundamental scientific methodologies and protocols used in social psychological research including the ethics and compliance training required by the Institutional Review Board for working with human subjects. They also learned about intergroup relations theory and research with a focus on explicit and implicit bias.

The course paired this theoretical foundation with practical components, such as field trips and site visits to relevant spaces. Locally, students visited such contested locations as Jackson Square, the Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Monument and the Plessy v. Ferguson Marker. In addition to these local museums and monument sites, the students and instructional team traveled to Montgomery, Alabama to visit the National Memorial for Peace and Justice. We included this site in the course in order to offset

students’ sometimes narrow references and expectations for what a monument/memorial should be. The abstract spatial experience choreographed by MASS Design Group provides a stark contrast stark contrast to the typical object-on-plinth typology common to existing monuments and memorials, challenging students to reorient their previous conceptions about monuments and memorials. This prescribed, designed experience exposed students to an alternative way of remembering. During the visit, we traversed a vast array of steel figures engraved with accounts of lynchings cataloged by counties. As the circumambulatory ramp dropped down, the steel boxes became suspended in mid-air relative to the viewer, evoking the visceral atrocity in our collective memory. The decidedly sequential experience, with a clear and intentional beginning and end, ultimately informed the group’s speculative design proposal for the exhibit described above. Inspired by this experience, students also identified a need to develop an awareness of other contemporary monuments and memorials that challenge existing typologies of the monument landscape in order to effectively incorporate diverse perspectives into an understanding of the current landscape. They then created a catalog of those monuments and memorials as part of their work in the course.

Left and next pages: National Memorial for Peace and Justice. MASS Design Group. Montgomery, AL. 2021 Photos by Tiffany Lin.

Enriching the interdisciplinary perspectives of our team, guest speakers were instrumental in extending our frame of reference for discussing monuments and memorials and leading class discussions in the context of the national movement.

Seminar guest speakers included:

• Jha D. Amazi

Co-director of the Public Memory and Memorial Lab at MASS Design Group

• Rachel Breunlin

Ethnographer and co-founder of the Neighborhood Story Project

• Jose Cotto

Local artist and photographer

• C.J. Hunt

Comedy writer and director of The Neutral Ground documentary

• Bryan Lee

Architect and founder of the Design Justice Platform and Colloqate Design

• Sue Mobley

Senior Research Scholar at Monument Lab

• Dr. Ibrahima Seck

Historian and research director at the Whitney Plantation Museum

Researchers & Designers at Tulane

Researchers & Designers at Tulane University are seeking participants

Who: Adults (18 and older) are eligible

What: Participate in a 45-minute to 1 hour discussion with other community members on the design and use of public spaces and monuments This discussion will help shape the content of a future survey that gathers the voices of community members and design professionals After participating in a small focus group session (5 people), participants will be paid $20 for their time

Where: Focus groups sessions will be held in-person at socially distanced locations: The Albert and Tina Small Center for Collaborative Design or at Tulane’s University Square Virtual sessions (in the participants’ own space) via Zoom can also be hosted

When: Focus groups will be scheduled based on participant availability

For more information, please contact us at: 504-314-7543

socpsy@tulane.edu

SPACEANDMONUMENTSTUDY.ORG

Please sign up online!

QR Code to online form:

Building upon the distinct perspectives of each invited speaker, along with exposure to social psychology and racial justice literature, the team generated the framework for community discussions and the content for public surveys. Students of the class combined input from these sources to complete a number of assignments, putting into practice the necessary considerations of the impacted community. In concert with the development of the research materials (e.g., survey, recruitment posters, community talking points), students produced a catalog of existing monuments/memorials/rituals and analyzed each case study in terms of formal and perceptual characteristics. They worked in groups to diagram and catalog existing monuments and memorials in terms of type, subject matter, formal characteristics, and temporality. These studies generated an index of existing monuments and memorials in the Greater New Orleans region in order to expose students to the multiplicity of monuments and the associated potential complexities of community opinions.

This exercise was both educational and practical, informing the students about memorials while providing a collaborative and educational design opportunity for the class that could help to address the previously identified knowledge gap among architecture and design professionals.

The culminating exhibtion included an interactive catalog of existing monuments exhibited at the American Institute of Architects Design Center in New Orleans.

Engaging a wall of operable panels, participants were invited to note whether they had seen the monument, whether they knew what it was about, and whether or not they liked it—which served as additional data on perceptions of public spaces, monuments, and memorials. The location of these case studies were marked with red dots on a city map adhered to the ground, with a prompt asking participants to indicate their own awareness of other monuments by inviting them to extend this catalog to areas our team has yet to include. In addition to educating the visitors, this installation project prompted self-reflection as well. A catalog of each of the fifty individual monuments and a summary of exhibition responses can be found on pages 98-305.

Left: How Do We Remember? Exhibition wall of case studies: Each monument/ memorial presented as an operable panel that invited visitors to share their opinions of the piece.

Our team believes that a significant gap exists between designers and community members, particularly in spaces that may be contested. We sought to be self-aware, teaching the students the importance of community input when work, as in our case, would result in an exhibition in a contested space. The team identified one way to fill this gap, through a survey to gather the data that should inform a project such as ours. We relied on this survey data to inform our work and posit that the survey itself can also serve as a template for data collection that may be done by future architects and designers as they embark on similar projects. We identified important questions to be answered that would be vital in helping us design our project. The primary research goal of our national survey study was to quantitatively examine the relationship between social group memberships, individual differences in social dominance orientation (attitudes toward social hierarchies and beliefs about whether one’s groups should dominate other groups),color-blind ideology (denial of racial differences by emphasizing sameness and denial of racism by emphasizing equal opportunities), community esteem or a sense of community, and participants’ opinions about which elements of design are relevant or desirable in community spaces. Over four hundred participants completed the thirty-minute survey as of April 2022. The survey data contains perspectives from across the

United States, including people who self-identified as designers and those who do not identify as designers.

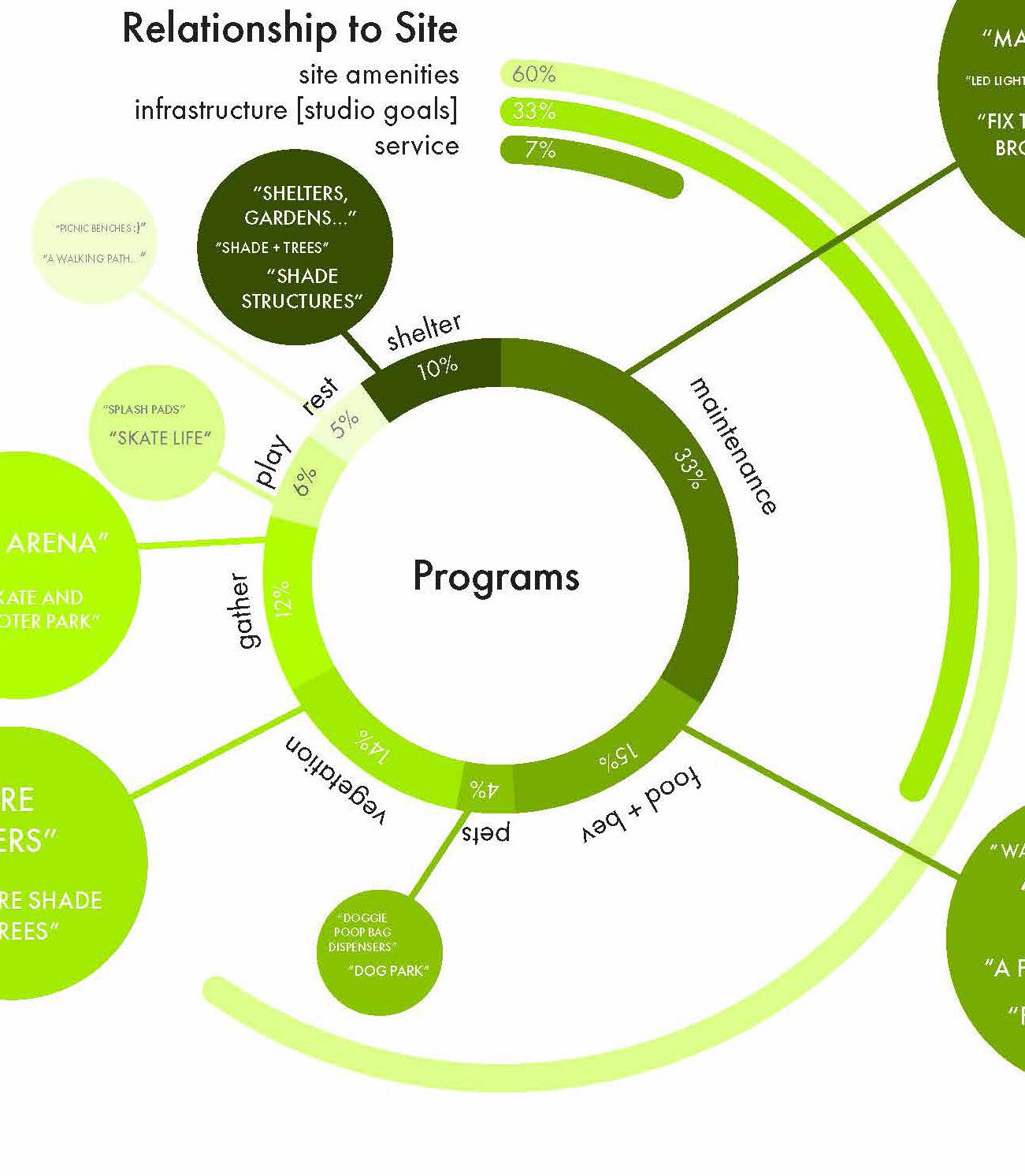

Although participants generally endorsed all objects as important (M =4.05 on 7 point Likert scale), the initial data suggests that there are differences in opinion between nondesigners and designers on what elements of design are ideal in public spaces. For example, those who did not self-identify as designers rated trees/bushes/flowers/objects, shade, parking, playgrounds, and art as being more important than those who self-identified as design professionals. In addition, both those who did not selfidentify as design professionals and design professionals strongly endorsed the idea that public monuments and memorials should reflect the communities where they exist. Most participants (89%) reported that they would enjoy public spaces and monuments more if they participated in creating it.

The graphic representations in the following pages highlight some findings from the survey, including initial data showing statistically significant differences between designers and nondesigners. Specifically, nondesigners reported lower social dominance orientation (SDO), endorsement of color blind ideology, and esteem for their community when compared to

design professionals. To date, no previous empirical research exists that examines the personality or worldviews of those who identify as design professionals. Due to the novelty of this data, the pattern of results elicits more questions than answers. Why are the worldviews of the design professionals in this data set different (e.g., less egalitarian, endorse colorblind ideology) from the nondesigners? Are these differences related to their choice of vocation or training? Despite an increased focus on equity, diversity, and inclusion across the discipline remains homogeneous.8 Indeed, increasing representation at all levels and improving the effectiveness of architectural education and accreditation via best practices will be necessary to achieve a more equitable, diverse, and inclusive field. Future research should aim to examine these relationships, the relationship between individual differences in worldviews, representation, and inclusive training practices.

In an effort to collect more qualitative data, our survey asked several open response questions such as: “Are there any personal thoughts you want to share related to the topic of public spaces/ monuments in your city?” Several participants took time to write in comments in these open fields. (Sample questions from the national survey can be found in the Appendix of this publication.)

Design Studio

The research seminar and studio associated with this project offered our students an opportunity to put theory into practice. Through the courses, students reconsidered design pedagogy and had a chance to welcome a broad coalition of stakeholders to collaborate on a community-engaged or participatory action research method of marking memory in public space.

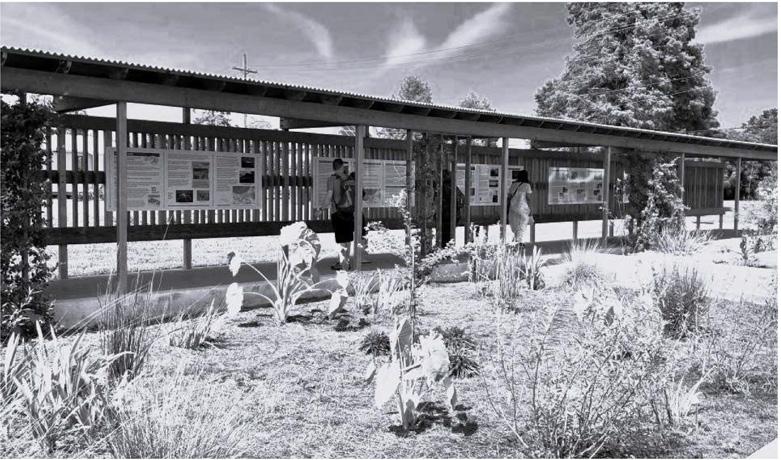

Our team led a group of architecture students through the process of prototyping a public memorial for the Lafitte Greenway—a linear park that transverses six urban neighborhoods of Central City, New Orleans. We collaborated with a community partner, Friends of Lafitte Greenway, a nonprofit organization with the goal of generating a community-engaged process that would inform the design of a new public memorial. Our team took every opportunity to incorporate relevant data and community input in the conceptualization of the project in order to develop a template for other designers doing similar work.

The specific site we selected is a public park that used to house a segregated playground.9 Currently the park is frequented by adults, children, locals and tourists of all races, enjoying the space for recreation and fitness. However, there exists recognition of its history in the location’s online presence or physical space.

The work required students to generate design proposals that acknowledged this divided history, and advance conversations regarding the need to codesign public spaces and memorials that reflect the communities in which they are situated. We coached our students through conversations with local elders and helped them understand how to use this qualitative information as well as the data from the survey to help the team shape the program for this site-specific proposal and translate the desire for communicating layered community histories.

We worked with a community partner with deep-seated knowledge of the site and its conflicted history, which allowed our design studio to test strategies for more inclusive site engagement and designs. For example, we erected temporary panels asking passersby to write what they thought would “make this place better” and whether they had a “story to share” about the site. The following pages show engagement with the panels that were designed by students, erected on site, and left for three weeks, during which time our team hosted activities to encourage conversations with those who frequent the park. We also held design process reviews on these site panels, inviting community input and critique. Students working in our social psychology lab transcribed and coded the data from these boards, which is

Site engagement boards erected for 3-weeks to collect community feedback.

Top: Graphic summary of park use as observed by team during site visits.

Right: Summary of responses from leave-behind site engagement boards.

graphically summarized on the following pages. Beyond this indirect input, students gained exposure to the complex nature of community opinion and the possible tensions or synergies between community engagement and survey data through direct connections with stakeholders. During conversations with community elders who grew up adjacent to this park, stories of important local leaders, social activists, and cultural events were shared. These meetings helped us better understand community members’ strong desire to have a space to recall their memories of this park and to contend with the stark, and relatively recent, transformations along the Lafitte Greenway. Many community members expressed a clear sentiment that the families who inhabited the housing complexes near the park were displaced due to gentrification. They also lamented that the current conditions of the park no longer reflected the community who helped build and care for it. The compilation of this feedback marked an important lesson for our students. While a project may be well-researched and a designer well-intentioned, information may become available that thwarts forward progress.

We realized that, in order to fully recognize and respect this history—and properly record and preserve these stories—the timeline to collect and appropriately incorporate personal stories

into a public monument was in conflict with the short calendar of an academic design/build studio and iterative IRB processes. Students were able to witness and participate in true dialogue with the community that resulted in a necessary outcome—a pause on the project—rather than a short-sighted move to barrel forward without considering the consequences.

Rather than crafting a design in the space, our team pivoted to the creation of an exhibition which aimed to share and extend our collaborative process with the public at the semester’s end. We invited community stakeholders to this space as an opportunity to critique our work and the process in order to further the conversation. Designing the exhibition and a physical prototype offered a pause to reflect upon the design process, and further design development conversations and decision making processes with our community partners. To this end, our team designed a series of abstract folded modules as a point of departure, able to adapt to the content desired by the community and be arranged into various different configurations. These placeholder modules can be aggregated in various orientations to create sculptural gateways. In the proposed scenario presented at the exhibition, the gateways align to connect the historic gate of the Black-only playground to the iconic oak tree on the site.

With branches spanning over 100-feet in diameter, this tree served as a natural landmark and shaded destination to culminate the folded gateways. These spatial frames were also designed to support benches and tables—informal gathering spaces desired by the community as we learned from our site conversations and data-collection boards. The proposal consisted of eight folded Corten steel panels that outline profiles of local figures to be honored, inscribed with local histories, and serve as a physical timeline that records the park’s transformation. Renderings and models of this speculative design proposal served as a vehicle for advancing conversations about what could be an appropriate

Landscape module studies inscribed with historical site data.

Unfolded Elevations

View of site proposal showing path and remembrance modules that are situated in a formerly segregated playground. The path runs from a neighboring historic housing complex to an active park.

design memorializes the truth or fiction of our collective past. Over the last academic year, professors and students from the Tulane School of Architecture and Department of Psychology have collaborated to share research methods and develop new courses that focus on public space and memory. This exhibition highlights our investigation of existing monuments and exploration into more just and equitable spaces in New Orleans and beyond.

How Do We Remember ?

How Do We Remember ?

Monuments and memorials have been the focus of contentious national conversations due to, at least in part, who and what they honor, and how their design memorializes the truth or fiction of our collective past. Over the last academic year, professors and students from the Tulane School of Architecture and Department of Psychology have collaborated to share research methods and develop new courses that focus on public space and memory. This exhibition highlights our investigation of existing monuments and exploration into more

Monuments and memorials have been the focus of contentious national conversations due to, at least in part, who and what they honor, and how their design memorializes the truth or fiction of our collective past. Over the last academic year, professors and students from the Tulane School of Architecture and Department of Psychology have collaborated to share research methods and develop new courses that focus on public space and memory. This exhibition highlights our investigation of existing monuments and exploration into more

5.20.22 Friday 5pm–8pm

Please join us for the opening reception

5.20.22 Friday 5pm–8pm

5.20.22 Friday 5pm–8pm

Please join us for the opening reception

Please join us for the opening reception

Exhibition

The culminating event of this project was the exhibition of this body of work at the AIA New Orleans Design Center—a charged venue that is in front of an approximately seventy-fivefoot empty pedestal that held a 16’-6” statue of Robert E. Lee until it was removed on May 19, 2017. Its storefront windows also face the city’s Civil War museum. Interactive panels invited visitors to contribute to the content of this exhibit and engage in conversations surrounding the design of monuments and memorials. Photos from the event show the final exhibition which incorporated content from the national survey, research seminar, and design studio—weaving together precedent analysis, monument typologies, our speculative proposal, and data from the National Monument Audit by Monument Lab.11 A full-scale mock-up in the exhibition space serves as a prototype for the landscape modules. It is inscribed with our overarching aim for the design proposal:

What if a MONUMENT is an experience: something you can walk through; and see yourself in; and sit with; that teaches you the history of the place?

While the exhibition was not the original goal of the course, students learned that if they sincerely wish to incorporate community feedback, they may need to shift their goals to better align them with the feelings of impacted citizens. This lesson is vital if design professionals wish to incorporate equitable practices into their public work. Please use the QR Code above to navigate a 360 documentation of this exhibition.

Right: Silhouetted hanging panels represent the four monuments removed in New Orleans, installed to frame the view toward the Civil War Museum.

Next Page: Graphic of data sourced from the Monument Lab’s National Monument Audit Sponsored by the Mellon Foundation-- fabricated into exhibition panels

of 48, 178 U.S. Monuments Studied, only 0.1% mention Confederate defeat; only 0.1% mention slavery in the Civil War.

of 48, 178 U.S. Monuments Studied, only 0.5% represent enslaved peoples and abolition efforts; 0.6% were removed in 2020-21.

of the top 50 individuals memorialized in the United States, only 6% are of women; only 10% are of black and indigenous people

for every 1,300 U.S. Monuments of ward, only 100 are about peace.

As educators who work to teach design values and practices that build a more equitable future, we hope that projects such as this can help both students and professionals in design fields gain a deeper understanding of and commitment to the relationship between design and social justice. Our work strengthened our belief in the need for interdisciplinary collaboration to gather data and the buy-in of community members if we want to create meaningful public monuments and memorials. Through this process, our design ambitions were tempered by the challenges and complexities (logistical, emotional, safety, budgetary) of completing a public memorial project in one academic semester. However, we were heartened by the flexibility and adaptability of our students as they developed an appreciation for the voices that informed our pivot. From speaking with the community elders, we were humbled by the extensive personal histories that preceded us and the need for more time and vested engagement to truly respect the immediate community input and craft a process for deciding which stories are told and how. We revealed that the time needed for this thoughtful engagement was at odds with academic and grant cycles, creating some internal friction between the desire to act and the need for more conversation and collaboration.

Previous spread and right: Exhibition wall presenting 50 case studies of monuments and memorials in New Orleans, each displayed as an operable panel that invited public commentary. A map of the Mississippi River through New Orleans indicated the location of each site.

Although the design/build project paused, we hope the gathering of this information will inspire design proposals that bridge the gap between architects and the general public when creating spaces marked by racial injustice. In addition, we hope the survey results and engagement tactics we used can be referenced by other practitioners, artists, and academics working on similar projects in the future.

Looking through the window at the empty pedestal on former Lee Circle, visitors envision and draw the future “monument,” contributing to this exhibition.

Precedents

How do we remember is not just a local question . . .

People across the world have been reckoning with how to mark, memorialize, and learn from past injustices. As we think about new ways to make monuments and memorials in New Orleans and beyond, it's useful to see the range of approaches employed by others wrestling with similar questions. These are a few of the projects our research team has been looking at to understand how designers, historians, and social justice workers are thinking anew about memory in public space.

1997

Dakar, Senegal

Artist: Ottavio Di Blasi

The Battle is Joined Goree Memorial

Located on the Island of Goree in Senegal, a UNESCO World Heritage site marking the largest slave-trading center on the African coast, the Goree memorial marks the highest point on the island and symbolizes those who were deported across the sea and those who remained in Africa.

May 1–November 16, 2017

Vernon Park, PA

Artist: Karyn Olivier Olivier’s temporary installation in Vernon Park was an acrylic mirror encasement that covered a twenty-foot-high Revolutionary War monument. The casement intended to bring people closer to one another, their surroundings, and their living histories.

Nelson Mandela "Release" Sculpture

2012

Nelson Mandela "Release" Sculpture

2012

Apartheid Museum, South Africa

Apartheid Museum, South Africa

Artist: Marco Cianfanelli

Artist: Marco Cianfanelli

Marking the South African site where Nelson Mandela was arrested in 1962, this sculpture is made of 50 steel columns whose arrangement appears random from most angles but aligns to form an image of Mandela’s face about 100 feet in front of the sculpture .

Marking the South African site where Nelson Mandela was arrested in 1962, this sculpture is made of 50 steel columns whose arrangement appears random from most angles but aligns to form an image of Mandela’s face about 100 feet in front of the sculpture .

Camp Barker Memorial

2019

Camp Barker Memorial

2019

Washington D.C.

Washington D.C.

Artist: After Architecture

Artist: After Architecture

In response to the landscape of American monuments to battle, the Camp Barker memorial is comprised of three entry gateways to an elementary school which reveal the site ’s complicated history as a Civil War-era contraband camp. The project takes the monument off its pedestal and makes it visually accessible to the public.

In response to the landscape of American monuments to battle, the Camp Barker memorial is comprised of three entry gateways to an elementary school which reveal the site ’s complicated history as a Civil War-era contraband camp. The project takes the monument off its pedestal and makes it visually accessible to the public.

Raise Up

2018

Raise Up

2018

National Memorial for Peace and Justice

National Memorial for Peace and Justice

Montgomery, AL

Montgomery, AL

Artist: Hank Willis Thomas

Artist: Hank Willis Thomas

Nkyinkim

Inspired by a 1960s photograph by Ernest Cole of South African miners, Thomas ’s sculpture, located at the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, suggests police suspects lined up at gunpoint. It references police brutality against African Americans and racial bias in the criminal justice system.

Inspired by a 1960s photograph by Ernest Cole of South African miners, Thomas ’s sculpture, located at the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, suggests police suspects lined up at gunpoint. It references police brutality against African Americans and racial bias in the criminal justice system.

2018

National Memorial for Peace and Justice Montgomery, AL

Artist: Kwame Akoto-Bamfo

This sculpture is dedicated to the memory of the victims of the Transatlantic slave trade at the entrance of the National Memorial for Peace and Justice. Its title

“Nkyinkyim” means twisted and references the proverb “life’s journey is twisted.“

Gun Violence Memorial Project

2019

Chicago, IL

Artist: MASS Design Group

Nkyinkim

2018

Nkyinkim

2018

National Memorial for Peace and Justice Montgomery, AL

National Memorial for Peace and Justice Montgomery, AL

Artist: Kwame Akoto-Bamfo

Artist: Kwame Akoto-Bamfo

This sculpture is dedicated to the memory of the victims of the Transatlantic slave trade at the entrance of the National Memorial for Peace and Justice. Its title

This project is a space of remembrance and healing for individuals impacted by gun violence. It features four houses built of 700 glass bricks, representing the average number of lives taken due to gun violence each week in America. Families can contribute remembrance objects within the glass bricks to honor loved ones that were lost to gun violence.

This sculpture is dedicated to the memory of the victims of the Transatlantic slave trade at the entrance of the National Memorial for Peace and Justice. Its title

“Nkyinkyim” means twisted and references the proverb “life’s journey is twisted.“

“Nkyinkyim” means twisted and references the proverb “life’s journey is twisted.“

memory references

and Justice the memory Transatlantic slave National Justice. Its title and references twisted.“

Gun Violence Memorial Project

2019

Chicago, IL

Gun Violence Memorial Project

2019

Chicago, IL

Artist: MASS Design Group

Stumbling Stones

Artist: MASS Design Group

Stumbling Stones

1992–present

1992–present

European and Russian Cities

This project is a space of remembrance and healing for individuals impacted by gun violence. It features four houses built of 700 glass bricks, representing the average number of lives taken due to gun violence each week in America. Families can contribute remembrance objects within the glass bricks to honor loved ones that were lost to gun violence.

European and Russian Cities

Artist: Guenther Demnig

Artist: Guenther Demnig

Landmark

1995

Stumbling Stones

Stumbling Stones

1992–present

1992–present

European and Russian Cities

European and Russian Cities

Artist: Guenther Demnig

Artist: Guenther Demnig

Known as “Stolpersteine ,” or “stumbling stones,”

This project is a space of remembrance and healing for individuals impacted by gun violence. It features four houses built of 700 glass bricks, representing the average number of lives taken due to gun violence each week in America. Families can contribute remembrance objects within the glass bricks to honor loved ones that were lost to gun violence.

Known as “Stolpersteine ,” or “stumbling stones,”

70,000 memorial blocks laid in more than 1,200 cities and towns across Europe and Russia each commemorate a victim of the Holocaust outside their last-known freely chosen residence.

70,000 memorial blocks laid in more than 1,200 cities and towns across Europe and Russia each commemorate a victim of the Holocaust outside their last-known freely chosen residence.

Known as “Stolpersteine ,” or “stumbling stones,”

Known as “Stolpersteine ,” or “stumbling stones,”

70,000 memorial blocks laid in more than 1,200 cities and towns across Europe and Russia each commemorate a victim of the Holocaust outside their last-known freely chosen residence.

70,000 memorial blocks laid in more than 1,200 cities and towns across Europe and Russia each commemorate a victim of the Holocaust outside their last-known freely chosen residence.

Indianapolis, Artist: In 1968, campaign, news of was dedicated to honor for their to raise eliminate

Violence Memorial Project

Design Group is a space of remembrance and individuals impacted by gun features four houses built of 700 representing the average lives taken due to gun violence America. Families can remembrance objects within the to honor loved ones that were violence.

Landmark for Peace

Landmark for Peace

1995

1995

Indianapolis, Indiana

Indianapolis, Indiana

Artist: Daniel Edwards

Artist: Daniel Edwards

Stumbling Stones

1992–present

European and Russian Cities

Artist: Guenther Demnig

In 1968, Robert F. Kennedy visited this site to campaign, however instead had to deliver the news of Dr. King’s assassination. The memorial was dedicated by former President Bill Clinton to honor both Dr. King and the late Mr. Kennedy for their contributions to the nation. It is meant to raise awareness and inspire action to eliminate division and injustice.

In 1968, Robert F. Kennedy visited this site to campaign, however instead had to deliver the news of Dr. King’s assassination. The memorial was dedicated by former President Bill Clinton to honor both Dr. King and the late Mr. Kennedy for their contributions to the nation. It is meant to raise awareness and inspire action to eliminate division and injustice.

Known as “Stolpersteine ,” or “stumbling stones,” 70,000 memorial blocks laid in more than 1,200 cities and towns across Europe and Russia each commemorate a victim of the Holocaust outside their last-known freely chosen residence.

Landmark for Peace

1995

Indianapolis, Indiana

Artist: Daniel Edwards

Ralph Ellison Monument

Ralph Ellison Monument

2003

2003

Ralph Ellison Monument

2003

Riverside Park NY

Riverside Park NY

Riverside Park NY

Artist: Elizabeth Catlett

Artist: Elizabeth Catlett

Artist: Elizabeth Catlett

This monument honors writer Ralph Waldo Ellison, who is best known for writing the epic novel , about an African American man and the tumultuous civil rights issues of the 1950s, who ultimately recedes into “invisibility. ” The monument features two granite panels that are inscribed with Ellison quotes and a biographical panel.

In 1968, Robert F. Kennedy visited this site to campaign, however instead had to deliver the news of Dr. King’s assassination. The memorial was dedicated by former President Bill Clinton to honor both Dr. King and the late Mr. Kennedy for their contributions to the nation. It is meant to raise awareness and inspire action to eliminate division and injustice.

This monument honors writer Ralph Waldo Ellison, who is best known for writing the epic novel , about an African American man and the tumultuous civil rights issues of the 1950s, who ultimately recedes into “invisibility. ”

The monument features two granite panels that are inscribed with Ellison quotes and a biographical panel.

This monument honors writer Ralph Waldo Ellison, who is best known for writing the epic novel , about an African American man and the tumultuous civil rights issues of the 1950s, who ultimately recedes into “invisibility. ” The monument features two granite panels that are inscribed with Ellison quotes and a biographical panel.

Shoes on the Danube River

Shoes on the Danube River

2005

2005

Shoes on the Danube River

2005

Budapest, Hungary

Budapest, Hungary

Budapest, Hungary

Artist: Gyula Pauer

Artist: Gyula Pauer

Artist: Gyula Pauer

This memorial honors the Jews who were massacred in Budapest during the Second World War. They were ordered to take off their shoes and were shot at the edge of the water so that their bodies fell into the river and were carried away. The memorial represents their shoes left behind on the bank.

This memorial honors the Jews who were massacred in Budapest during the Second World War. They were ordered to take off their shoes and were shot at the edge of the water so that their bodies fell into the river and were carried away. The memorial represents their shoes left behind on the bank.

This memorial honors the Jews who were massacred in Budapest during the Second World War. They were ordered to take off their shoes and were shot at the edge of the water so that their bodies fell into the river and were carried away. The memorial represents their shoes left behind on the bank.

Ralph

2003

Riverside Artist: This Ellison, novel man 1950s, The monument are inscribed biographical

Transformation

As the National Monument Audit highlights, the American monument landscape is constantly changing. Whether by conscious choice (i.e., when societies evolve and their values, priorities, and power dynamics change) or by entropy (i.e. materials degrade and places change), public monuments and memorials in our city can be understood as existing, but ever-changing in their relationship with the public. In addition to the "stump" at the center of the urban circle in which you stand, another clear example of this transformation can be seen in the plinth that once held a pedestal and monument to Jefferson Davis, former President of the Confederate States.

1911

A monument of Jefferson Davis is installed on the neutral ground at the intersection of Jeff Davis Parkway and Canal Street in New Orleans, Louisiana.

Jefferson Davis monument anonymously graffitied with the words "slave owner".

TRANSFORMATION

TRANSFORMATION

Jefferson monument graffitied "slave

TRANSFORMATION

Jefferson Davis monument anonymously graffitied with the words "slave owner".

2017

2017

Armed promonument protesters verbally spar with antimonument protesters at Jefferson Davis monument in response to news the statue would soon be removed.

Under heavy police presence, Jefferson Davis statue and pedestal are removed in the early morning on May 11, 2017, leaving only the foundation.

2017

2020

Under heavy police presence, Jefferson Davis statue and pedestal are removed in the early morning on May 11, 2017, leaving only the foundation.

The Jefferson Davis Parkway is renamed for Norman C. Francis, former Xavier University of Louisiana president.

The Jefferson Parkway is for Norman former Xavier University of president.

Davis renamed Francis, Louisiana

2020

The Jefferson Davis Parkway is renamed for Norman C. Francis, former Xavier University of Louisiana president.

police Jefferson Davis pedestal are early 11, 2017, foundation.

2021

Demond Melancon's Big Chief of the Young Seminole Hunter tribe Mardi Gras Indian suit is displayed on the foundation.

2020

The Jefferson Davis Parkway is renamed for Norman C. Francis, former Xavier University of Louisiana president.

2021

2021

Demond Melancon's Big Chief of the Young Seminole Hunter tribe Mardi Gras Indian suit is displayed on the foundation.

The “Freedom Drum” sculpture by artist Rontherin Ratliff and the Level Artists Collective was unveiled during the “Juneteenth Freedom Ride, “ a symbolic bus tour of three new public art works in New Orleans on June 18, 2021.

2021

The “Freedom Drum sculpture by artist Ratliff and the Level Collective was unveiled during the “Juneteenth Freedom Ride, “ bus tour of three art works in New June 18, 2021.

2021

The “Freedom Drum” sculpture by artist Rontherin Ratliff and the Level Artists Collective was unveiled during the “Juneteenth Freedom Ride, “ a symbolic bus tour of three new public art works in New Orleans on June 18, 2021.

Typologies

The Design Language of Memorials and Monuments

What do you think of when you hear the word “monument”? Chances are you are thinking of something large and iconic made of stone or bronze or some material that projects permanence. Monuments and memorials tell stories—some true, some not—about moments in our collective history. Historically, monuments tell their stories through sculptural figures, materials, borrowed classical languages, or styles. More recently designers have been questioning the established language of monument making toward more experiential and personal forms of commemoration. These drawings attempt to break down the language of monuments over time to understand what design approaches and elements are used in telling stories in public space.

Nola Monument Catalog

How Do We Remember? is a larger question of this research project, extending beyond specific objects and places. The following catalog is divided into the shifting categories of monuments, memorials, symbols, rituals, and informal recognitions. This collection of monuments is an ongoing effort to create a broader frame of reference for artists, architects and the public as we continue to think and create means of marking – and unmarking – significant people, times, and spaces.

In addition to well-know landmarks, this catalog of monuments also showcases familiar rituals (second lines) to lesser-known memorials (remembrance orbs) and a wide spectrum of spaces we commonly pass by but rarely stop to see (Al Davis Park, Newman Bandstand, the Martin Luther King monument). This list is, of course, non-exhaustive and we invited visitors to contribute their own monuments that may not have been included in this collection.

Have

Installation Date: 1856

Installation Date

Location Inscription 1856

Jackson Square at Decatur Street and St. Peters Street

CHARTRESST

ST.ANNEST

ST.PETER

FRENCH QUARTER

DECATURST

Have you SEEN this monument? no yes

Did you KNOW what it memorialized? no yes

Do you LIKE this monument? no yes

NEW ORLEANS MONUMENT CATALOG

Andrew Jackson Memorial

Installation Date

1856

Location

Jackson Square at Decatur Street and St. Peters Street

“Major General Andrew Jackson” “The Union must and shall be preserved”

Bronze Sculpture, Stone Pedestal

Inscription Material(s) Information

The focal point of the central urban square in New Orleans’ historic French Quarter, the Jackson equestrian statue was sculpted by Clark Mills. Three other identical statues are located in Washington. D.C., Nashville. Tennessee. and Jacksonville. Florida. Many praised the artist for the manner in which he succeeded in balancing such a mass of metal - 20,000 pounds - without any support or prop beneath. Mills, appearing at the dedication, described his statue as depicting General Jackson on horseback as he reviewed his troops on the morning of January 8, 1815 before the Battle of New Orleans against British forces. The lines present arms in salutation to their commander and Jackson lifting his plumed hat: the customary manner of returning a salute in those days. His high-spirited horse, aware of the next movement, is making strenuous attempts to dash down the line but is restrained by the superb horsemanship of its rider. The statue represented Jackson. who “with a handful of men, proved himself the savior” of New Orleans.

The inscription on the granite base of the monument was cut by General Benjamin Butler’s orders during the federal occupation of New Orleans during the Civil War. In 1830. at a celebration for Thomas Jefferson’s birthday. President Andrew Jackson made the following toast: “Our Federal Union: It must be preserved!” In 1862. General Butler changed Jackson’s famous statement. whether intentionally or unintentionally. to read: “The Union must and shall be preserved.”

2

Installation Date

Installation Date: 1978

FRENCH QUARTER

POYDRAS ST CANALST

Have you SEEN this monument? no yes

Did you KNOW what it memorialized? no yes

Do you LIKE this monument? no yes

Installation Date Location

1978 377 Poydras Street

Piazza d’ltalia

Inscription

None

FONS SANCTI JOSEPHI. HVNC FONTEM CIVES NOVI AVRELIANI TOTO POPULO DONO DEDERUNT.”

Translation: The Fountain of St. Joseph: The citizens of New Orleans have given this to all the people as a gift

Material(s)

Concrete, Plaster, Water, Stone, Marble

Information

The Piazza d’ltalia is a monument to the Italian-American community and their contribution to the City of New Orleans. Designed in 1878 by renowned architect Charles Moore, The Piazza gained public attention as a symbol of late Post-Modernism and is one of Moore’s best-known and influential works. The Piazza d’Italia is a gathering place for the New Orleans Italian community as well as a symbol of the cultural contribution to architecture that is so unique to the ambiance of New Orleans.

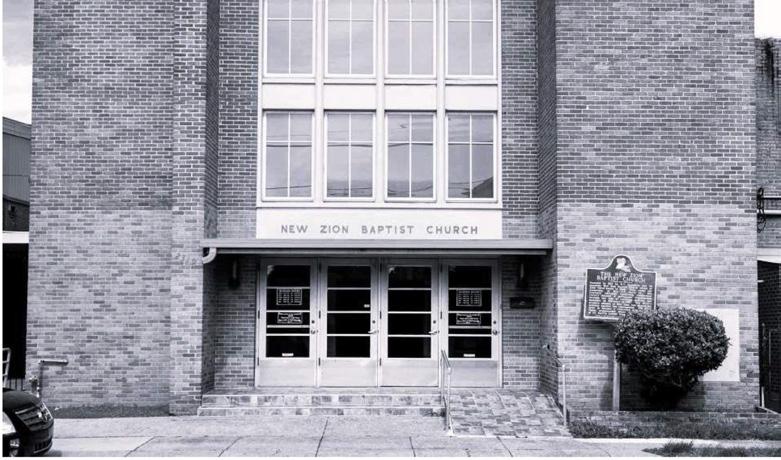

3 New Zion Baptist Church

Installation Date: 1957

Installation Date

Location 1957 2319 Third Street Corner of Lasalle Street and Third Street

THIRDST

A.L. DAVIS PARK

LASALLEST

SLIBERTYST

Have you SEEN this monument? no yes

Did you KNOW what it memorialized? no yes

Do you LIKE this monument? no yes

SECONDST

New Zion Baptist Church

Installation Date

1957

Location

2319 Third Street

Corner of Lasalle Street and Third Street

Inscription

Founded in 1921 by R.C. Matthews and 45 members, New Zion Baptist Church moved to 2319 Third Street in 1949. Here, under the leadership of Rev. A.L. Davis Jr., the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) became a permanent organization through the vote of Louisiana activists and ministers on February 14, 1857. The SCLC grew to became a renowned national civil rights organization under the directorship of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

Material(s) Information

Various On February 14. 1957. a group of Baptist pastors and activists from across the South met at the New Zion Baptist Church at the earner of Third and LaSalle streets. It was here the group farmed the Southern Leadership Conference. which later that year would rename itself the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). Later that year, members elected Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. as president, who had been in attendance that day. The organization would coordinate nonviolent action to desegregate bus systems across the South and later would take on bigger issues of segregation nationwide.

4 Chalmette Monument

Installation Date: 1908

Installation Date

CHALMETTE

JEAN LAFITTE PARKWAY

Have you SEEN this monument? no yes

Did you KNOW what it memorialized? no yes

Do you LIKE this monument? no yes

ORLEANS MONUMENT CATALOG

ST.BERNARDHIGHWAY

Chalmette Monument

Installation Date

1908

Location

I Battlefield Road, Chalmette, LA

Chalmette Battlefield and National Cemetery

Inscription

Monument to the memory of the American soldiers who fell in the Battle of New Orleans at Chalmette. Louisiana. January 8th. 1815. Work begun in 1855 by Jackson Monument Association. Monument placed in custody of United States Daughters of 1776 and 1812 an June 14. 1884. Monument and grounds ceded unto the United States of America by the state of Louisiana on May 24. 1807.

Completed in 1808 under the provisions of an Act of Congress approved March 4th. 1807.

Material(s)

Brick Base, Marble Spire

Information

Marking the site of the Battle of New Orleans in 1815. Chalmette Battlefield contains a reconstructed American rampart, an 1830s house, 100-foot-high Chalmette Monument. and outdoor exhibits for self-guided tours. Visitor center films and exhibits share the battle and the site’s later history. Ranger talks are offered daily. Chalmette National Cemetery was established during the Civil War and holds more than 14.000 graves of Americans from the War of 1812 to the Vietnam War.

5 Monument to the Immigrant

Installation Date: 1995

Installation Date Location 1995 Woldenberg Park. New Orleans Riverfront

DECATURST

CONTIST N PETER ST

Have you SEEN this monument? no yes

Did you KNOW what it memorialized? no yes

Do you LIKE this monument? no yes

Monument to the Immigrant

Installation Date Location

Woldenberg Park. New Orleans Riverfront

Inscription

Monument to the immigrant dedicated to the courageous men and women who left their homeland seeking freedom. opportunity and a better life in a new country March I9. 1995 commissioned by the Italian American marching club. Sponsored by private citizens, businesses, and organizations.

Material(s)

Marble

Information 1995

Located by the Steamboat Natchez Station on the Mississippi River, this statute commemorates the cultures that contribute to the vibrant development of New Orleans. The piece depicts a family of immigrants on one side and a female figure shaped like the front of a ship on the other. The Italian American Marching Club in New Orleans commissioned Franco Alessandrini to sculpt this monument. Alessandrini. an Italian immigrant. came to the United States in the 187Os. making Louisiana his home. The strategic location of this monument along the waterfront adds to its narrative and serves as a powerful reminder to visitors of the immigrants who helped to establish New Orleans.

Thomy Lafon Elementary Memorial Promenade

Memorial Promenade

October 2013

Installation Date Location

Installation Date: 2013

Magnolia Street

Here on this ground are the Locust Grove Cemeteries. Locust Grove I became operational in 1858.

Grove II opened in 1876. These burial grounds marked the final resting place for African

SIXTHST

MAGNOLIAST

SEVENTHST

Have you SEEN this monument? no yes

Did you KNOW what it memorialized? no yes

Do you LIKE this monument? no yes

Thomy Lafon Elementary Memorial Promenade

Installation Date

October 2013

Location

Magnolia Street

Between Sixth Street and Seventh Street

Inscription

Here on this ground are the Locust Grove Cemeteries. Locust Grove I became operational in 1858. Locust Grove II opened in 1876. These burial grounds marked the final resting place for African Americans, indigents, immigrants, and victims of epidemics such as the cholera outbreak of 1866. For these pauper cemeteries, officials duly recorded the names, ages, gender, color, and cause of death. The files tell the final stories of those who died from aneurysms, cancer, typhoid fever, and other maladies of the 1860s and 1870s. While the majority of those interred were born in New Orleans, others had roots in faraway locales such as Germany, Prussia, and Ireland. The last burials occurred in 1878 when the Locust Grove Cemeteries were closed due to poor sanitary conditions On these hallowed grounds, the Orleans Parish School Board built three schools dedicated to native son and philanthropist Thorny Lafon. During construction on the site in the 1850s and 1880s, workers found human remains and cypress coffins. In 1885 archaeologists recovered items associated with the burials like buttons and a clothing buckle. Various historical panels on site.

Material(s)

Concrete, Bronze

Information

Thorny Lafon Elementary School was named for Thorny Lafon (1810-1883), a free Creole man who was at one time the wealthiest free Black man in the nation. Lafon was self educated and accumulated his wealth as a merchant. He dedicated much of his time and money to philanthropy and activism and outlined various financial donations in his will for after his death. In addition to the school, Lafon founded or donated money to help found Lafon Home for Boys, Charity Hospital, Sisters of the Holy Family, The Tribune, and other charities which helped both blacks and whites of New Orleans.

7 Flood Marker

Installation Date: 2008

NEW ORLEANS RECREATION DEVELOPMENT COMMISSION

Have you SEEN this monument? no yes

Did you KNOW what it memorialized? no yes

Do you LIKE this monument? no yes

ORLEANS MONUMENT CATALOG

Flood Marker

Installation Date

2008

Location

Neutral ground of Franklin Avenue North of Mithra Street, Gentilly

Inscription

Floodwaters rise and recede, and those who survive mark the event and continue. “Flood-marker continues this in a literal but also conceptual vein. Rather than a small plaque and waterline attached to any wall, this “flood-marker” is an 8,000 lb freestanding and monumental granite block of water.

Material(s)

Carved Granite

Information

The stone is elevated on a series of processional rollers not unlike those that ancient stonecutters used to move large stone blocks into place on the pyramids. The great block of water becomes a nomadic monolith at rest. It has the potential to be moved but only through extreme human effort. The rollers also serve as benches, a place for the public to sit on and reflect. The extreme effort it would take to roll the monolith is no longer needed, the viewer’s job is done, the burden is over and a welldeserved rest is offered as is a place to reflect on this catastrophic event. This sculpture is intended to memorialize the New Orleans Flood of 2005 without overt judgment. The hope and strength of the work are presented in the purposeful carving of a timeless material. This public sculpture is not a literal flood marker; it does not tell us how high the waters rose in any specific part of our city. Instead it is the aesthetic expression of a defining event in time. 1,836 waves are carved into the stone, one wave for each life lost to the water.

Artist: Christopher Saucedo

MAGAZINEST

Have you SEEN this monument? no yes

Did you KNOW what it memorialized? no yes

Do you LIKE this monument? no yes

ORLEANS MONUMENT CATALOG

Sara Lavinia Hyams Memorial Fountain

1921

Installation Date Location

6500 Magazine Street, New Orleans, LA

Inscription

By bequest Mrs. Chapman H Hyams left her jewels to Audubon and City Parks, the proceeds of which were to build a testimonial of her love for her home city. This fountain was erected March 1821 in a faithful endeavor to realize her wishes. She loved the beautiful and gave that all might enjoy.

Material(s)

Bronze Sculptures, Concrete Base, Wading PooI

Information

The Sara Lavinia Hyams Memorial Fountain in Audubon Park is one in a set of two fountains in the name of Sara Lavinia Hyams, a New Orleanian philanthropist who passed on an estimated $30,000 worth of jewelry for the youth of New Orleans, funds that would later be utilized in the creation of these fountains. The fountains were originally used as shallow pools for children to play in during the hot summer months. In its current, less inviting state, warn by weather and time, the fountain is less frequented.

Palmer Park (Marsalis Harmony Park)

Renamed 2021

9 Palmer Park (Marsalis Harmony Park)

Installation Date Location

Renamed 2021

Installation Date: 1902, Renamed: 2021

Installation Date Location

South Carrollton Avenue and Claiborne Avenue

South Carrollton Avenue and Claiborne Avenue

SCLAIBORNEAVE

SCARROLLTONAVE

NERONPL

UPTOWN/CARROLLTON

Have you SEEN this monument? no yes

Did you KNOW what it memorialized? no yes

Do you LIKE this monument? no yes

Palmer Park (Marsalis Harmony Park)

Renamed 2021

Installation Date Location

South Carrollton Avenue and Claiborne Avenue

Inscription

Palmer Park (temporary yard signs noting new name: Marsalis Harmony Park)

Material(s)

Stone Archway

Information

Previously named after infamous secessionist, Pastor Benjamin Palmer, Marsalis Harmony Park is a very large urban park now named after Jazz musician Ellis Marsalis. This name change occurred in the summer of 2021, a year after the social movements that roiled the United States. Currently, the park contains a shaded playground, measured walking path, and a monument to the city of Carrollton, with dedications to its annexation and to WWII veterans of Carrollton. The walking path and monument divide the park into two sections,. excluding the large archway that defines the entry to the park at the eastern edge where the walking path meets the street.

10 Tomb of the Unknown Slave

2004

Installation Date Location

Installation Date: 2004

St. Augustine Catholic Church 1210 Governor Nicholls Street

On this October 30, 2004, we, the faith community of St, Augustine Catholic Church, dedicate this shrine

LOUIS ARMSTRONG PARK

ESPLANADEAVE

HENRIETTEDELILLEST

GOVERNORNICHOLLSST

NRAMPARTST

Have you SEEN this monument? no yes

Did you KNOW what it memorialized? no yes

Do you LIKE this monument? no yes

ORLEANS MONUMENT CATALOG

Tomb of the Unknown Slave

Installation Date

2004

Location

St. Augustine Catholic Church

1210 Governor Nicholls Street

Inscription

On this October 30, 2004, we, the faith community of St, Augustine Catholic Church, dedicate this shrine consisting of grace crosses, chains and shackles to the memory of the death in Faubourg Treme. The Tomb of the Unknown Slave is commemorated here in this garden plot of St. Augustine Church, the only parish in the United States whose free people of color bought two outer rows of pews exclusively for salves to use for worship. This St. Augustine/Treme shrine honors all slaves buried throughout the United States and those slaves in particular who lie beneath the ground of Treme in unmarked, unknown graves. There is no doubt that the campus of St. Augustine sits astride the blood, sweat, tears, and some of the mortal remains of unknown slaves from Africa and local American Indian slaves who either met with fatal treachery, and were therefore buried quickly and secretly, or were buried hastily and at random because of yellow fever and other plagues. Even now, some Treme locals have childhood memories of salvage/restoration workers unearthing various human bones, sometimes in concentrated areas such as wells. In other words, the Tomb of the Unknown Slave is a constant reminder that we are walking on holy ground. Thus, we cannot consecrate this tomb because it is already consecrated by many slaves’ inglorious deaths bereft of any acknowledgment, dignity or respect. But ultimately glorious by their blood, sweat, tears, faith, prayers and deep worship of our creator.

Donated by Sylvia Barker of the Danny Barker Estate

Material(s)

Bronze

Information

Coming upon this shrine, as the plaque calls it, a casual visitor will find themselves in an historic neighborhood on a quaint street in Treme. The monument is set back from the street and is adjacent to an entrance to the church. The dark steel cross itself is striking partly because it sits against a white stone church. Even more attention-grabbing is the juxtaposition of shackles hanging from various parts of the cross. In contrast to the violence they suggest, they hang like delicate ornaments.

11

Monument

Martin Luther King, Jr. Monument Installation Date Location

CENTRAL CITY

SRAMPARTST

MARTINLUTHERKINGJR.BLVD

Have you SEEN this monument? no yes

Did you KNOW what it memorialized? no yes

Do you LIKE this monument? no yes

Dr Martin Luther King, Jr. Monument

Installation Date

1976

Location

Martin Luther King Blvd. Neutral Ground Between Oretha Castle Haley Blvd. and South Rampart St.

Inscription

“I have a dream. Let it ring from every city. I have a dream that one day every valley shall be exalted, every hill and mountain shall be made low, the rough places will be made plain. I have I have I have a dream. I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin. Free at last free at last thank God almighty I’m free at last. I say to you even though we face the difficulties of today and tomorrow I still have a dream.”

Tribute to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

In 1876, the City of New Orleans dedicated the Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Walk, a pathway created on the Melpomene St neutral ground between Dryades St. and S. Claiborne Ave. The city commissioned artist Frank Hayden to create a sculpture for the foot of the walkway. In 1877, mast of Melpomene St was renamed Martin Luther King Jr. Blvd., and in 1888, the commercial section of Dryades St. was renamed to honor New Orleans Civil Rights Leader Oretha Castle Haley. In 2018, the area surrounding the sculpture was redesigned to improve accessibility and provide historical context.

Sculptor Frank Hayden (1834-1888).

Information

This sculpture was created by Frank Hayden in celebration of the Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Walk. Hayden was a distinguished professor of fine arts at Southern University and a Xavier University graduate. As an artist, Hayden’s style was contemporary and abstract. The piece symbolizes the coming together of all people in brotherhood and understanding, which was Dr. King’s aspiration. Hayden cast the sculpture in bronze using the 4,000 year old “last wax” technique. The interior features spiral shaped excerpts from Dr. King’s 1863 “I Have a Dream” speech as well as a symbolic bullet hole to represent the assassination of Dr. King in 1868.

Material(s)

Bronze, Concrete, Stone

12 Music Tree

Installation Date

Installation Date: 2004

MOSS ST MOSSST

ORLEANSAVE

Have you SEEN this monument? no yes

Did you KNOW what it memorialized? no yes

Do you LIKE this monument? no yes

ORLEANS MONUMENT CATALOG

Installation Date

2012

Location

Moss Street and Orleans Avenue

Music Tree

Inscription

Carved images of Snakes, a Fleur-de-lis, a Phoenix-like Eagle, Guitars, a Piano Keyboard, and a Pelican

Material(s)

Tree Carving, Paint

Information

The Music Tree, created by Marlin Miller, pays homage to New Orleans music culture. The original tree that stood at this location survived the water and wind of Hurricane Katrina only to be struck and killed by a bolt of lightning in 2012 during Hurricane Isaac. After being approached by the organizers of the Mid-City Bayou Boogaloo, chainsaw artist Marlin Miller was tasked with transforming the tree into the landmark that sits along the bayou today.

13 Plessy V. Ferguson Marker

Installation Date: 1921

Installation Date Location 1921 Homer Plessy Way, New Orleans, LA

NEW ORLEANS CENTER FOR CREATIVE ARTS

Have you SEEN this monument? no yes

Did you KNOW what it memorialized? no yes

Do you LIKE this monument? no yes

ORLEANS MONUMENT CATALOG

Plessy V. Ferguson Marker

Installation Date

1921

Location

Homer Plessy Way, New Orleans, LA

Inscription

Homer Plessy was born Homere Patris Plessy on March 17, 1863 in New Orleans. His parents were carpenter (Joseph) Adolphe Plessy and seamstress RosacDebergue, both classified as people of color. Homer Plessy died on March 1, 1825. He is entombed in St Louis Cemetery No. 1.

John Howard Ferguson was born in 1838 in Martha’s Vineyard. MA. He was appointed Judge in Section A of the Orleans Parish Criminal Court in 1882 and ruled against Plessy in November of the same year. He is buried in Lafayette Cemetery.

Material(s) Information

Bronze, Aluminum, Paint

Plessy v. Ferguson was a landmark 1886 U.S. Supreme Court decision that upheld the constitutionality of racial segregation under the “separate but equal” doctrine. The case stemmed from an 1882 incident in which African American train passenger Homer Plessy refused to sit in a car for Black people. The Supreme Court ruled that a law that “implies merely a legal distinction” between white people and Black people was not unconstitutional. As a result restrictive Jim Crow legislation and separate public accommodations based an race became commonplace.

The Marker in this location, near the train tracks that separate the Marigny from the Bywater neighborhoods of New Orleans, commemorates this case.

14 Allen Toussaint Mural

Installation Date: 2018

Installation Date

ESPLANADEAVE

Have you SEEN this monument? no yes

Did you KNOW what it memorialized? no yes

Do you LIKE this monument? no yes

KERLERECST

Allen Toussaint Mural

Installation Date Location

2018 1441 N. Claiborne Avenue. New Orleans, LA, 70116

Inscription Material(s) Information

None Paint, Concrete Wall

Painted by New York-based artist Brendan Palmer-Angell in 2018, this mural of Toussaint was produced through the NOLA Mural Project to honor Toussaint, one of the most important figures in postwar New Orleans music culture. Toussaint was the man behind Ernie K-Doe’s No. 1 hit “Mother-in-Law,” Jessie Hill’s “Doh Po Pah Doo,” and Chris Kenner’s “I Like it Like That.” He assembled the Meters as a studio band, produced Dr. John’s acclaimed “Right Place. Wrong Time” album, and wrote LaBelle’s smash “Lady Marmalade.” Shortly after Hurricane Katrina he recorded “The River in Reverse,” a collaboration with Elvis Castello, and began performing more frequently. He was on tour in Spain when he passed away unexpectedly at age 77 in 2015.

The mural, in which Toussaint is pictured smiling, wearing a brightly colored suit and tie, is situated near the controversial 1-10 overpass which devastated the economy of a historically black community. The site is now an important location for second line parades, Mardi Gras Indians, and other culturally significant celebrations.

15 Gen. G. T. Beauregard Monument

Installation Date: 1915-2017 Beauregard Monument

Installation Date

1815-2017

Location

Entrance to City Park

Junction of Esplanade Avenue and Wisner Boulevard

G.T Beauregard, 1813-1883, General C.S.A. 1861-1865.

NCARROLLTONAVE

CITY PARK

WISNERBLVD

LELONGDR

ESPLANADEAVE

Have you SEEN this monument? no yes

Did you KNOW what it memorialized? no yes

Do you LIKE this monument? no yes

ORLEANS MONUMENT CATALOG

Gen. G. T. Beauregard Monument

Installation Date

1815-2017

Location

Entrance to City Park Junction of Esplanade Avenue and Wisner Boulevard

Inscription

G.T Beauregard, 1813-1883, General C.S.A. 1861-1865.

General Beauregard equestrian statue has been placed on the National Register of Historic Places by the United States Department of the lnterior, 1888.

Material(s) Information

Bronze Statue, Stone Pedestal

The General Beauregard Equestrian Statue, honoring P. G. T. Beauregard, was located in New Orleans, Louisiana at the intersection of Carrollton Avenue and Esplanade Avenue at the main entrance to City Park, on Beauregard Circle. The statue was added to the National Register of Historic Places on February 18, 1888. On December 17, 2015, the New Orleans City Council voted 6-to-l to remove the Gen. Beauregard Statue. The statue’s removal began on May 16, 2017 and was completed on May 17.

After the statue was removed, its pedestal remained in place. On July 25, 2018 after the base of the statue was removed, a time capsule was discovered to exist. The capsule was opened on August 3, 2018 and found to contain Confederate memorabilia, including photos of Confederate General Robert E. Lee and Confederate President Jefferson Davis, along with flags, currency, medals, ribbons and other paper items related to the city.

16 Congo Square

Installation Date

Installation Date: 2010

LOUIS

ARMSTRONG PARK

NRAMPARTST

ORLEANSST

BASINST

Have you SEEN this monument? no yes

Did you KNOW what it memorialized? no yes

Do you LIKE this monument? no yes

ORLEANS MONUMENT CATALOG

April 2010

Installation Date Location

Congo Square

Louis Armstrong Park, New Orleans, LA

Inscription