TUFTS OBSERVER

1 VOLUME CXXVIII

2023

ISSUE

SPRING

TABLE

CONTENTS 2 LETTERS FROM THE EDITORS melanie litwin & amanda westlake 4 WORDS ARE WIND, DEEDS ARE STONE FEATURE • ava vander louw 8 LEARNING TO GET ALONG WITH HYDRANGEAS III POETRY & PROSE • felipe campano 10 ACCOUNTABILITY & ACTION NEWS • edith philip 12 FOR THE LOVE OF LEBANON VOICES • nour el-solh 18 GREEN LINE GENTRIFICATION CAMPUS • tess robinson 20 SCENES FROM SOWA ARTS & CULTURE • sofia valdebenito 22 ONE EYE POETRY & PROSE • matilda yueyang peng 23 THROUGH THE STOMACH POETRY & PROSE • d gateño 24 REFLECTIONS ON COLLECTIONS ARTS & CULTURE • sage malley 26 LET’S DIRECT OUR ANGER ABOUT COVID TOWARD THE REAL ENEMY OPINION • leah cohen

OF

Editors-in-Chief

Melanie Litwin

Amanda Westlake

Editor Emeritus

Sabah Lokhandwala

Managing Editor

Juanita Asapokhai

Creative Directors

Angela Jang

Yimeng Lyu (Anna)

Feature Editors

Ruby Goodman

Emara Saez

News Editors

Rohith Raman

Layla Kennington

Arts & Culture Editors

Sophie Fishman

Millie Todd

Opinion Editors

Michelle Setiawan

Clara Davis

Campus Editors

Liani Astacio

Eden Weissman

Poetry & Prose Editors

Neya Krishman

Priyanka Sinha

Voices Editors

William Zhuang

Sarah Fung

Creative Inset

Ines Wang

FSTA F

Art Directors

Aidan Chang

Audrey Njo

Multimedia Director

Pam Melgar

Multimedia Team

Anika Kapoor

Megan Reimer

Juniper Moscow

Emmeline Meyers

Claudia Aranda Barrios

Brenda Martinez

Publicity Directors

Ava Vander Louw

Sofia Valdebenito

Publicity Team

Anthony Davis-Pait

Emma Iturregui

Aatiqah Aziz

Staff Writers

Edith Philip

Leah Cohen

Billy Zeng

Ava Vander Louw

Sage Malley

Lily Feng

Siona Wadhawan

Hanna Bregman

Erin Zhu

Felipe Campano

Veronica Habashy

Joyce Fang

Bella Cosimina Bobb

Designers

Madison Clowes

Hami Trinh

Anastasia Glass

Jasmine Wu

Anthony Davis-Pait

Aviv Markus

Anya Bhatia

Lead Copy Editors

Lucy Belknap

Eli Marcus

Copy Editors

Seun Adekunle

Kara Moquin

Lucy Jerome

Alec Rosenthal

Drexel Osborne

Nika Lea Tomicic

Phoebe McMahon

Ashlie Doucette

Podcast Directors

Noah DeYoung

Grace Masiello

Podcast

Emily Cheng

Ethan Walsey

Alice Fang

Megan Reimer

Soraya Basrai

Jamie Doo

Qinyi Ma

Eden Weissman

Staff Artists

Emmeline Meyers

D Gateño

Olivia White

Lydia Jiameng Liu

Heather Huang

Mariana Porras

Rachel Liang

Chileta Egonu

Zed van der Linden

Nour El-Solh

Soraya Basrai

Matilda Peng

Maria Cazzato

Katie Rejto

Adina Guo

Contributors

Tess Robinson

Nicole Garay

this scrap time?

retains all impressions. what to do with all

contemplation. hugs are like fossils. the heart

NOSTALGIA

hand, feelings unparsed by the comb of

unbraiding my memory with my left

COVER BY ANNA LYU, DESIGN BY ANGELA JANG

COVER BY ANNA LYU, DESIGN BY ANGELA JANG

DEAR READER,

Nostalgia is a fitting theme for this issue. It is a feeling I know well, a bittersweet knot in my stomach as I sit down to write this letter. I must confess I’ve laid awake at night thinking about my memories of this magazine so far, thinking about what story I should tell, how the words should unravel. Do I tell you about my high school journalism teacher who encouraged me to write, or perhaps about starting at the Observer 3.5 years ago as a freshman copy editor? What does this magazine mean to me? How do I take a feeling so profound, so BIG, and squish it down into neat lines of 10 point font?

As usual, I have more questions than answers. But I dare offer that is what this is all about. We ask questions, as writers and artists and students, yet that does not mean we always have the answers, nor should we.

Ths whole experience—the Observer, college—all of it will be a memory soon. I have a hard time with that, I’ll admit. I try to grasp moments of time between my hands, so hard that my knuckles turn white and my figernails leave crescent moons on my palms. But time does this funny thing where it keeps moving and I am left in he doorway, looking at the places I’ve been. The words I’ve written. The people I love.

But not yet.

I am grateful the Observer serves as such a fundamental piece of my memories from college. It has been the constant that has fulfilled and guided me throughout the past seven semesters. But there’s still one more to go. I am filled with excitement, love, joy, and anticipation of creating this magazine with the rest of the Observer staff or another semester. Somehow, it still feels brand new each time.

Writing and art—in other words, creating—is how we hold onto the present as it becomes the past. It is how we make sure there is a record. Record of the students and faculty at this school, of art created, of abuses of power, of people coming together, of people divided. These stories—carefully preserved and protected within these pages—matter so deeply. I am honored to help facilitate the creation and mission of this beautiful magazine of record, and I am honored to have you flp through the pages, reading its words and taking in its art.

Reader, please allow me a moment of indulgent nostalgic recollection: As a young child, I distinctly recall not understanding paragraphs. When assigned to write one for second grade spelling homework, I’d write a story, pages long. My parents laugh about it now, how long it would take me to do something that should’ve been so simple. But how could I just tell part of the story? My brain has always worked this way, bursting to write down every thought, leaving nothing uncompleted and nothing forgotten. I want this magazine to be that space for you, the Tufts cmmunity—a space to say everything you haven’t had the opportunity to say yet. A space to have your voice heard, completely.

So many people have poured themselves into this magazine before me, and so many people will continue to make the Observer what it is, and what it can be, after me. I am merely a footnote in its history. Thank you to Lena, Owen, Myisha, Bota, Josie, Aroha, and Sabah for doing this fist and so well. Thank you Juanita, Anna, and Angela for doing this alongside me now. You are so beautifully talented, and I am incredibly lucky to share this experience with you.

And of course, thank you Amanda—for being my co-editor-in-chief, the other half of my brain, and my best friend. We started this journey together freshman year as the quietest of the copy editors who found each other because we didn’t want to go to an Observer bonding by ourselves… Now our house is well-known to much of the O staff. You’ve made me a better writer, a better editor, and most importantly a better person. In all the memories I’ve created at the O, meeting you remains my favorite.

Thank you to the entirety of the Observer staff or your laughter and love. And to my friends for the same. And thank you, reader. Yes, you. For holding on to the memories with us.

With love, Melanie

2 TUFTS OBSERVER FEBRUARY 21, 2023

LETTERS

DEAR READER,

Picture this: 15-year-old Amanda. Wearing an Aéropostale T-shirt and skinny jeans, just a few years removed from braces. In a spiral notebook, she pens a long list of possible careers. Scrawls writer at the top.

When she hears her high school is starting a school newspaper, she is elated. She drags a friend to the informational meeting so she won’t be alone. But the classroom is empty. Nobody else is there. When the English teacher asks if she still wants to write, she hangs her head, quietly says no. There is no newspaper at her high school, no magazine of record. She wants to write, but she can’t do it alone.

I dreamed of being a journalist for a long time before joining the Observer, probably influenced by romanticized portrayals of the profession on screen. Thik Gregory Peck in Roman Holiday or Meg Ryan in Sleepless in Seattle. When you’re a fitional journalist, your job communicates complexity. You are curious, persistent, thoughtful. A little bit mysterious. I saw myself in this persona, or at least who I thought I might want to be.

But when I actually started to write for the Observer three years ago, I found journalism to be so much more. The act of writing true stories was unglamorous. It required tenacity, careful judgment, and a lot of late nights.

Thoughout the past several semesters, I’ve come to an understanding of journalism as a form of power. Writing, to me, is seizing power in a world that doesn’t want you to have any. At the Observer, we consistently tell stories against the better interests of incredibly wealthy, powerful institutions. There are many of these stories in this issue.

I know our magazine has power, because I see its impact everywhere. It looks like professors sharing a story on LinkedIn with their peers. A fist-year publishing their very fist Voices piece about an identity they’ve never spoken about before. A note from a reader who appreciated a reflction of themselves. The stories between these pages are discussed in classes, talked about at The Sink, and even posted in Tinder profiles.

There is a secret behind this power: It comes from the people. The 90-plus students who are committed to our mission, who write and edit so well, who create gorgeous art and designs. I didn’t have that community in high school. I’m glad I do now.

So here’s my promise for this semester: We will continue to tell the stories that must be told. We will pursue the truth, report with integrity, and never stop asking questions. We will uphold our publication’s mission to uplift arginalized voices and hold institutions accountable to the best of our ability.

And I’ll admit, the romantic notion of journalism is not entirely wrong. The Observer is not just powerful, but beautiful, too, both the painstaking process and glossy product. In “Goodbye to All That,” legendary journalist and essayist Joan Didion writes, “I liked all the minutiae of proofs and layouts, liked working late on the nights the magazine went to press, sitting and reading Variety and waiting for the copy desk to call.” Joan Didion always understands.

And now for some thanks: To Melanie, I am beyond thrilled to be working together this semester. When we sat next to each other that very fist evening as copy editors freshman fall and wrote our fist article together the next spring, I never dreamed that we would end up being co-editors-in-chief, housemates, and most importantly, best friends. I could not imagine these past four years without you; your dedication, brilliance, and strength inspire me every day.

To Juanita, the Observer is endlessly lucky to have you; your leadership is invaluable, and there’s nobody else I would rather spend layout with. To Anna and Angela, I am thrilled to see more of your beautiful designs this semester. To Josie, thank you for showing me how to run this magazine so long ago. To the rest of the Observer’s staff thank you for your passion, talent, and many missed hours of sleep. Each and every one of you brings something special to our publication. And fially, to our readers, thank you for everything. Without you, our work would mean nothing.

Love, Amanda

FEBRUARY 21, 2023 TUFTS OBSERVER 3

“WORDS ARE WIND, DEEDS ARE STONE”:

THE DISCONNECT BETWEEN DEIJ EFFORTS AND STUDENT NEEDS

By Ava Vander Louw

By Ava Vander Louw

R SEPTEMBER 28, 2020

4

R

21,

FEATURE

T UFTS OBSERVE

FEBRUARY

2023

Following protests in response to George Floyd’s murder by Minneapolis police, President Tony Monaco joined thousands of other universities across the country in condemning acts of racism in a message to Tufts University. In a statement released after the university’s fist observation of Juneteenth in 2020, President Monaco announced Tuft’ commitment to becoming an anti-racist institution. Since the commitment to “eradicate any structural racism” and prioritize creating a representative community in 2020, Tuftshas launched several anti-racist initiatives that have been praised by senior leadership as significant steps. However, many members of the Tuftscommunity, specifially marginalized students who are most greatly impacted by institutional and cultural racism, continue to voice that widespread anti-racist reform has been inadequate across the university.

Th Campus Climate Survey, conducted during February and March of 2022, reflcts these sentiments. The survey report, released on January 23, 2023, emphasizes that the survey results—which received responses from only 29 percent of all Tuftsstudents, faculty, and staff—ay not be representative of the opinions of the Tufts campus population overall.

According to the results, students of historically underrepresented racial, ethnic, and gender identities were disproportionately dissatisfid with Tuft’ campus climate. Further, these marginalized communities demonstrated a diminished sense of inclusion and belonging and experienced bias, harassment, and discrimination more frequently than their peers. As a result, Tuftshas committed to developing an actionable plan in order to address the survey results.

In April 2023, Monroe France will fill the newly created position of Vice Provost for Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Justice (DEIJ). According to a written statement to the Tufts Observer from Caroline Genco, the provost and senior vice president ad

interim of Tufts,“An important step in advancing [DEIJ] work is partnering with University Communications & Marketing to develop a DEIJ communications strategy,” which Monroe will help to implement. Genco went on to explain that the survey’s purpose is to open up more channels of communication about DEIJ issues across the university. “We know communication is critical,” Genco wrote. “We want to foster constructive and interactive dialogue that will help us meet our shared goals.” The administration plans to continue communicating their initiatives to the Tuftscommunity in the coming months. Regarding next steps, Genco said Tuftswill be “engaging the community to identify the targeted actions that we need to take to improve the campus climate. Following this engagement, we’ll develop an implementation plan and timeline.”

Hope Freeman, the senior director of the Women’s Center and LGBT Center, emphasized that, while only a small percentage of students took the survey, the results still reveal an unsurprising depiction of how marginalized students feel at Tufts.“Every other year there’s always a new diversity check or a new climate survey. But the results are always the same. We’re still not feeling seen, not feeling safe, not feeling supported,” Freeman said.

While the Provost’s officclaims this past survey was Tuft’ “fist university-wide DEI Campus Climate Survey,” Tuftshas received previous feedback that its attempts to foster an inclusive and equitable campus have been inadequate. According to a 2013 report from the Council on Diversity, “Data gathered indicate that students from historically marginalized groups disproportionately experience marginalization in and outside of the classroom and also experience incidents of bias on our campus.” Looking back even further, a 1997 report from the Task Force on Race highlighted, “Students of color have said that they often feel they are ‘guests’ at this institution rather than an integral, vital part.”

These past reports presented institutional recommendations to senior leadership to reduce inequality and discrimination at Tufts. The most recent DEIJ Strategic Plan released by the School of Arts and Sciences in May 2021 echoed similar ideas to both the 2013 and 1997 reports. Some initiatives from these past reports have been successfully implemented, such as the creation of the Chief Diversity Office and Associate or Assistant Dean of Diversity and Inclusion (ADDI) administrative roles, increased investment in fiancial aid, and the establishment of an Indigenous Center in 2022. According to Genco, “ The schools are all individually also making investments into DEIJ programming, focusing on faculty recruitment, ADDIs (Associate or Assistant Dean of Diversity and Inclusion), and academic programs and trainings, such as implicit bias training, for their communities.”

However, many of the recommendations from 2021 and earlier have yet to be carried out. An example of this is the initiative, outlined in the May 2021 Strategic Plan, to “compensate students who assume [DEIJ] roles and responsibilities at the school’s or department’s request.” According to the plan, the School of Arts and Sciences intended to realize this from 2021 to 2022. When asked about the May 2021 commitment to compensate and award students doing DEIJ work, Director of Media Relations Patrick Collins forwarded a statement from the School of

SEPTEMBER 28, 2020 TUFTS OBSERVER 5

FEATURE

“EVERY OTHER YEAR THERE’S ALWAYS A NEW DIVERSITY CHECK OR A NEW CLIMATE SURVEY. BUT THE RESULTS ARE ALWAYS THE SAME. WE’RE STILL NOT FEELING SEEN, NOT FEELING SAFE, NOT FEELING SUPPORTED,”

FEBRUARY 21, 2023 TUFTS OBSERVER 5

DESIGN BY AVIV MARKUS, ART BY ADINA GUO

Arts, Sciences, and Engineering that read, “As it pertains to DEIJ service activities performed for the university and/or specificschools, our policy is not to pay students because the effort is an act of service. However, if there are opportunities for students to be employed and work on DEIJ efforts, then they will be compensated.” Currently, graduate students within the GSAS Community Fellows and the Graduate Leadership in Inclusion, Diversity, and Equity (GLIDE) Fellows programs and researchers within the School of Engineering’s Data Analysis for DEIJ Action team are compensated; but many other community members outside of these programs continue to engage in unpaid DEIJ work.

Another important recommendation that has yet to be fully realized is the allocation of adequate funds and staffing for the Division of Student Diversity and Inclusion centers. In the 1997 report, Tufts community members articulated a need to remedy a historical pattern of underfunding and understaffing identity centers. “A statement of understanding that is contradicted by a lack of support demonstrates a lack of priority for these students’ needs and concerns, [and] staffshould be added to help the single staffassistant that serves five of the Centers,” the report stated.

Since 1997, community members have continually expressed that more resources and personnel are needed for the DSDI centers. Freeman, for example, mentioned that, for the majority of her time on campus as the LGBT Center Director, she was the only staff member. Originally hired as the director of the LGBT Center in 2017, she ended up volunteering to also head the Women’s Center less than a year later. After working with the previous Women’s Center director to transform both of the spaces to be more inclusive of students of color and trans students— as both centers were historically, “very cis, very white, and very upper class”— Freeman didn’t want the trajectory of the Women’s Center to regress.

“[My interim position] was only supposed to be six months. It turned into about three years,” Freeman said. It wasn’t until September 2022 that Freeman was offically recognized as the senior director of the Women’s Center.

An anonymous intern at the Asian American Center said that, although Asian-identifying students comprise around 20 percent of the Tuftscommunity—and they feel the university often touts this high percentage to promote the school’s image—the center is not equipped with enough resources to support those students. “ There’s a lot of things that we could focus more on, but we don’t necessarily have the funding or ability to [expand support for students],” they said. “ The only reason why I feel like I’m a part of a campus or community on this campus is because of the center.”

While working to implement changes within her DSDI centers, Freeman noted how challenging it was to advocate for herself and her students. “We’ve been doing a lot of kicking and screaming [to receive sufficit funding and staffmembers],” Freeman said. “If I were to look at other job descriptions and things like that across other universities, I would technically be in a dean position, right? Especially given all the breadth of the population of students that I’m supporting.”

his experience coordinating events for the Black Men’s Group, an organization run through the Africana Center, he mentioned that through conversations with alumni it was evident that underfunding has always been an issue. Nana said many alumni have told him things like, “‘we never had enough money for this’ or ‘Tuftsdidn’t let us do this.’” Nana underscored that, even though students and directors often petition upper administrators for more resources, the money has never followed. “It’s a broken record,” he said. According to Genco, “ The university has committed to doubling its investment in its anti-racist work, from $25 million to $50 million over five years.” Some community members have reservations about where these investments will go. Freeman touched on an ongoing issue with administrative budgeting decisions, stating, “ There’s a lot of gatekeeping around what’s important programming, what’s important work, what’s worth this money?”

According to Freeman, one reason marginalized communities have not experienced a structural or cultural shift,despite the initiatives that Tufts has worked on, is because students of color and the directors of DSDI centers are treated as an afterthought. “We’re interacting with students all the time, especially the folks within the DSDI program. So it’s disheartening [to work in] a very hierarchical place where we get the top down direction, but there’s no room for bottom up direction,” she said. Ths sentiment also resonated with Casasola.

Marvin Casasola, director of the Latinx Center, also expressed that DSDI directors are often overburdened in carrying out the institution’s DEIJ work. “I’m doing work here that’s already outside of the director’s job description,” he said. “We should be utilized for our expertise, meaning we’re not going to sit here and do the entire thing for the whole institution, but we expect to provide valuable input because our voices belong in the conversation,” said Casasola.

Junior Wanci Nana said that students who frequent DSDI centers have noticed their scarce resources. When speaking on

Genco stated the Campus Climate Survey was created “as a tool that would inform and further our anti-racism commitment.” At the same time, not all DSDI directors—whose expertise lie in advancing DEIJ and advocating for marginalized students—were consulted during the development of the survey. Casasola said, “I personally was not involved in how that survey was going to be developed. No one ever reached out to me directly to say, ‘Hey, Marvin, we’d love your input as to what questions we should ask [and] how we should release the survey.’” Freeman also expressed she was not consulted for the development of the survey.

UFTS

S FEATURE

OBSERVER

FEATURE 6 T UFTS OBSERVE R FEBRUARY 21, 2023

“WHAT DO ALL OF THESE NEW INITIATIVES , ALL OF THESE NEW ADMINISTRATORS … THIS DEEP STRATEGIC PLANNING , LIKE WHAT DO THOSE THINGS LOOK LIKE TANGIBLY FOR US STUDENTS ?”

Beyond this, some community members view Tuft’ messaging around antiracist initiatives—and even in the case of the Campus Climate Survey—as unclear at best. Nana, when asked his opinions on Tuft’ responses to racism on campus, commented, “It’s defintely a facade… People do appreciate the transparency and knowing what’s happening on campus [but] it’s just kind of copy, paste, copy, paste.”

In regards to what the university decides to comment on, Freeman said, “It’s really glaring around what the university prioritizes and what the university doesn’t prioritize.” Following the international outrage after the murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Ahmaud Arbery, the administration swiftly denounced racism and continued to regularly release pub lic statements regarding national acts of discrimination or injustice. Yet, overtime, these public statements on behalf of the administration have dwindled. “January was rough. And there were numerous Black people who were killed by police. Tyree [Nichols] was murdered by police,” Freeman said. “[And] all the anti-trans legislation, [Florida] is basically erasing black history… and so literally these com munities that I support and don’t feel safe in this center are being told nationally that they’re not important.” She continued, “I didn’t see [acknowledgement], and, if I did

in the Africana Center and co-founder of his own company W3, Nana is working to empower those “who may not necessarily have the resources to develop wealth, practice wellness, and obtain wisdom,” he said. While Nana also noted his involvement within the Black Men’s Group, which has proved to be an invaluable space for him, he questioned the administration’s direction. “What do all of these new initiatives, all of these new administrators… this deep strategic planning, like what do those things look like tangibly for us students?” When it comes to university-wide DEIJ initiatives, he said, “Words are wind,

FEATURE

FEATURE FEBRUARY 21, 2023 TUFTS OBSERVER 7

The streets are narrow in this part of Massachusetts, in front of each house a big bushel of hydrangeas. In the cool, start-ofAugust breeze passing through, they almost look like confetti, waving around as individual petals fall to the browning grass left flattened and scorched by the drought. They’re most usually that same creamy shade of white, with the occasional taste of blue that must hold some gentle secret or another; some suburban gossip, a blue which I’m sure could’ve felt nostalgic to me if I had grown up a bit further north. \

But it’s a special kind of confusion for the psyche to play this game, to learn to call two places home—this sort of oscillation between missing the familiarity and comfort of the sun you grew up with while being grateful for and excited by the sun you’ve come to know here. The sun back home was intense. It showed you its love through the choking humidity of your youth, nursed you on thunder, hibiscus, and sunburns; it lit in you a fire that told you to throw everything you had at what you wanted, to give every last bit of yourself to all of the things you admired. It was Sundays upon Sundays all spent with the family, kissing everyone goodbye at the ends of parties; lips touching skin in a cramped, hot car on the first date, or a much-needed movie after dark. Maybe it was fighting, a few slaps across the face, but a lesson learned each time nonetheless; it grew deep into you, gripping your lungs like mangroves rooting into peat. The sun rising over the New England coast is not like the one you left. It is gentler, more patient, less severe; it glows off the white blossoms on dogwood trees in spring, kisses your face when the cold air bites you to announce the arrival of snow. It’s Saturday road trips into small, nearby towns, morning-afters in sleepy cafeterias; going no further than a kiss and regretting it a week later anyway, but never wishing you’d done anything differently. But it often leaves you wanting more. Laying outside in the grass swallowing all the sun you can catch; in chasing that light, you never stop running, never fully know when to settle down. Moving, pulling up roots, becomes more than just what you take with you or what you leave behind; it’s always searching, learning more, but never being sure how long to stay.

And a lesson you learn all too quickly when you move across the country like this is to be careful of which sun you carry with you that not everyone was raised in that kind of heat. The same brightness that lovingly browned your skin, warmed the seawater enough to replace your blood, would kill most flowers up north. You find out the hard way, baptized headfirst and sizzling in the ruthless new chill of the sea. You stumble but, budding and bloody, you always get back up. Crashing through branches, you crack a few stems, give yourself time to break out into blossoms and let the light pour down your petals like nectar, like sweet opportunity, like joy. You learn to slow down, to take the Massachusetts summer for what it is and not what you’re missing; you learn to find that warmth you’re chasing in an overfilled shot glass passed around between friends, or in the huge, noble surface of a shoreline traced wholly in stone. And after some time, you learn to love the cool breeze that embodies early August in Rockport, or the bushels of hydrangeas shining pastel greetings across nearly every front yard you pass. See, this dance, this constant cycle of living between suns, isn’t easy; in the reconciling of two lives, trying hard not to let yourself prioritize one or the other, you border on hating one version of yourself to fully embrace the second, and it can feel like shattering. But in the moments when you move between them, transitioning between life under a hot Florida sky and a frigid dawn looking out at you from across the Salem Sound, you’re in love with both, so full of sunlight you feel like you could burst into a ball of fire yourself. So you sit back in that Jeep with the top thrown back and think about what to do next. \

And I’m nearing twenty now. I can almost taste it on my tongue like sugar water from the little red flowers we used to suck on outside of the church. And I wonder about the you that you were when we started out up here. What did you think of me then? Of yourself? Was I immature, too loud? Insecure, or a little too proud? Did you think I could stand up for myself, or am I still that person even now? And are we maybe more similar than either of us would like to admit? I have so many stories I wish I had the time to tell you, but instead of exhausting myself trying to find the right words as I too often try to do, I’ll follow the example I took from the hydrangeas and simply hide all of those memories in a very particular shade of blue. I’ll love this sky for the sun that shines in it, the kind that brings me flowers on sidewalks and leaves me begging for warmer weather all winter long, only to miss the snow a few days after I realize that suddenly I’m alone and it is June. And the growing up comes in time—maybe out on a paddleboard or under the fluttering leaves, that springtime rustle of a season’s rich forgiveness that finally covers the Lawn. And maybe in time, like me, you’ll find that home is more than just what you grew up on or where you end up living—that maybe it’s behind you, on the road somewhere, that maybe it’s somewhere up ahead. Maybe it’s hidden in goldenrod, or in the bits of seaglass we carefully picked out of the rocks. Maybe it’s in finding a way to like hydrangeas again, this time for nobody but myself. \\

POETRY & PROSE 8 T UFTS OBSERVE R FEBRUARY 21, 2023

“there has to be a better way of getting into cold water than just jumping in feet-fi rst, but I haven’t found it yet / learning to get along with hydrangeas III”

POETRY & PROSE 9 T UFTS OBSERVE R FEBRUARY 21, 2023

DESIGN BY ANASTASIA GLASS , ART BY MARIA CAZZATO

ACCOUNTABILITY AND ACTION

REMEMBERING SAYED FAISAL

By Edith Philip

n January 4, 2023, Cambridge Police shot and murdered UMass Boston student Sayed Faisal. According to the City of Cambridge’s website, after two officers spotted him with a machete-style knife while suffering from a mental health crisis, one officeadvanced to him with a “lessthan-lethal” form of ammunition, but the other took out his “department-issued fiearm” and opened fie. Faisal, who was lovingly called Prince by his family, was then taken to the hospital where he died from his injuries at the young age of 20.

Ths event has caused ripples through the South Asian community, as Faisal was Bangladeshi. His parents, Sayed Mujibullah and Mosammat Shaheda, spoke to the Massachusetts chapter of the Council on American-Islamic Relations in order to issue a statement. They wrote, “We are completely devastated and in disbelief that our son is gone. Prince was the most wonderful, loving, caring, generous, supportive, and deeply family-oriented person…We want to know what happened and how this tragic event unfolded. We will cooperate with law enforcement and the Middlesex District Attorney’s officas they investigate to have an understanding of this devastating event.”

The Bangladeshi Association of New England has also been involved in

4 T UFTS OBSERVER SEPTEMBER 28, 2020

10 T UFTS OBSERVE R FEBRUARY 21, 2023 NEWS

demanding justice. After the incident, they organized a protest in front of Cambridge City Hall. “We need to bring justice for this young brother. Police brutality needs to stop,” BANE said in a Facebook post on January 4. At the rally, the president of BANE called for more training of offics and said, “He’s a baby—you just can’t shoot.” Since then, BANE has been organizing more demonstrations and coordinating with other groups in the area.

Boston is still reeling from this tragic incident but has channeled grief into continued action. For example, the Boston Party for Socialism and Liberation (PSL) attended the Cambridge City Council meeting to demand the release of the names of the cops involved, as well as an unredacted police report. At this meeting, Mayor Sumbul Siddiqui, the fist Muslim mayor in Massachusetts history, said to the crowd, “Tonight, I share your distress, your confusion, your pain at your lowest point. As city leaders, we have a lot of unfinshed work to address and we have to do everything we can to make sure this never happens again.” However, for weeks, Cambridge representatives, including Mayor Siddiqui, have neglected the community’s concerns and refused to hear their needs. In fact, representatives leftthe room to continue the meeting virtually when PSL arrived. Community members have been enraged by this and are fiding new ways to force the council to listen to their demands. Before holding a moment of silence for those killed by police violence, MIT student Hannah M. Flores said, “It’s a moment of silence because their blood is on your hands. You guys are in actual positions to change something.”

Aneeqah Ahmed, an intern at Tufts Asian American Center, reflcted on hosting Mayor Siddiqui as a speaker in November. She said, “As a South Asian and Muslim myself, when I met Mayor Siddiqui…I was greatly inspired that someone like me was in a position of power.” However, she explained after hearing about Mayor Siddiqui’s behavior in council, “It was saddening to see the response from the Cambridge City Council. Our community deserves

DESIGN BY ANYA BHATIA, ART BY MARIANA PORRAS

Ahmed shares the sentiments of her South Asian peers, who are equally enraged by this example of police brutality. Suhail Purkar, a member of the Boston South Asian Coalition and UMass Boston alumnus, said, “It’s really outrageous how just the most basic of demands, [like to] release the name of the offics, release the unredacted police report, fie and prosecute these offics to the fullest extent on

an East Asian man, and the Police Commissioner is a Black woman, which just goes to show how different faces in higher places isn’t the solution, and the system is racist and rotten to its core.” Although there is a wide array of representation in Cambridge City Council, as Ahmed observed, just because there is someone of your background in officdoesn’t mean they will necessarily enact policies that will protect you.

the law [have not been done], and there’s been no traction regarding any of these demands.” The coalition held a communitywide meeting on January 12 to raise their concerns but were told by city leadership in front of hundreds that it was policy not to disclose names of those being currently investigated. Purkar expressed their shock when they later heard from City Manager Yi-An Huang at a Cambridge City Council Special Meeting held on January 18 that it was not policy, but rather Huang’s fear of “greater public scrutiny and transparency” that prevented the release of the names.

Like Ahmed, Purkar reflcted on the limitations of viewing diverse representation in government as the key to enacting political change. He said, “ The Mayor is a South Asian woman, the City Manager is

Cambridge City Councilor Quinton Y. Zondervan has been vocal about his disappointment with his colleagues’ reactions. He wrote in an email to the Harvard Crimson, “We must reject the racist system of policing that is failing our young people, failing our minority communities, and failing those experiencing a personal crisis.” He expanded on this in a written statement to the Observer, calling for the abolition of the police. He wrote, “We should not have lethally armed police offics responding to a person who is self-harming with a knife.”

The hunger for justice is strong in the Asian community, and activists are amplifying the power of communities to enact change. Purkar said, “ The police killed 12,000 people last year, only 2 percent led to criminal charges being brought, and 0.5 percent percent overall led to convictions. The deciding factor is mass community pressure that refuses to be sidelined.”

DESIGN

FEBRUARY 21, 2023 TUFTS OBSERVER 11

BY JOHN DOE, ART BY JANE DOE

NEWS

“OUR COMMUNITY DESERVES MORE THAN CONDOLENCES FROM POLITICIANS.”

FOR THE LOVE OF LEBANON

By Nour El-Solh

By Nour El-Solh

“Meet me at Riad El Solh,” my mother says as she passes my bedroom door. Holding high the magnificet Lebanese flag with my Canon camera draped around my neck, I head to the square dedicated to my ancestor, whose name is synonymous with to the country’s independence. My mother has joined the calls of the pulsing crowd. I raise my flag beside her. Enmeshed in the sea of our fellow citizens, we call for the return of the country to its people. Our stand is framed by the parliament on the right and the statue of Riad El Solh on the left. He stands with his back to the parliament, the malignant and divi- sive sectarian regime, as if challenging the politicians of today to answer us. His people. Our people.

“El Solh” means “the peacemaker” in Arabic. He was one of the founding fathers of Lebanon, serving as Prime Minister in the 1940s and 1950s. His efforts toward establishing Lebanon as a nation free from French domination made him an important leader for the country’s independence movement. In the political landscape, ElSolh advocated for pluralism and democracy and embraced the coexistence of the five diverse religions of Lebanon. As “the peacemaker,” he played a key role in the negotiations that ended the Lebanese Civil War in the 1940s.

I grew up feeling proud to share this man’s name and to carry its symbolic meaning. Though the luxury and comfort of peace

has evaded our country, El Solh’s statue has patiently watched over us through the “Cedar Revolution,” the War of 2006, multiple influxes of refugees fleeing neighboring conflicts, and the economic and public health crises of today. On August 4, 2020, a terrible explosion surrounded the statue with glass and the broken spirit of Beirut. His statue has watched it all. Attending the revolution as a descendent of this man was a powerful experience—one that both challenged and changed my very core. Something greater than my nationality bonded me to the revolution; I felt a sense of personal responsibility.

The Revolution started on the morning of October 17, 2019, when the Lebanese cabinet announced new unnecessary tax measures

12 T UFTS OBSERVE R FEBRUARY 21, 2023 VOICES

on WhatsApp calls. Ths act was seen as a symbol of ignorance and egocentrism that disregarded the actual needs of struggling Lebanese citizens. The country was facing several recurring economic and political challenges. A small group of powerful elites had been maintaining their grip on the government for over 10 years, turning the political system into their family business. The government was in the heart of deep-seated corruption, which created a sense of disillusionment in the political and economic system. Moreover, the country was also grappling with the aftermath of a devastating civil war which leftbehind social, political, and economic scars. Even 30 years later, Lebanon was still shaking from the war. Economically, the Lebanese poverty rate grew exponentially. Lebanese citizens were not living anymore—they were surviving. According to the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia, 74 percent of the population lived under the poverty line in 2021 on less than $14 per day. At the same time, Lebanon was facing a high level of debt, unprecedented rates of unemployment, and a Ponzi scheme worsening its already waning situation. The scheme, also called “Beirut Madoff,” was caused by the central bank, which was financing the wasteful spending of Lebanese politicians with ordinary bank depositors. Consequently, the Lebanese currency, the lira, plunged by more than 90 percent from the offial rate. The revelation of the Ponzi scheme along with the corrupt mismanagement of the government fueled people’s anger and frustration. Change was needed. Immediately. On the breezy afternoon of October 17, 2019, widespread hatred was articulated into protests all over Lebanon. Tens of thousands of protesters were on the streets, screaming for accountability at the top of their lungs. They were no longer willing to tolerate the status quo. Protesting and chanting became our daily routine from dusk till dawn.

, “ The people want to overthrow the regime!” is the sound that echoed nonstop in the square of Riad El Solh. With our wrists fimly raised, this chant became our anthem for the next few months.

On that fist day I joined my mother in the protests, I experienced, among other

feelings, a deep-seated sense of humiliation and disgust with myself. Before that day, I had been numb. My family’s legacy meant I’d grown up with great privilege, protected within a bubble whose membrane filtered the reality of the population around me so that it didn’t reach my attention. That day—the calls of the people and the looks in their eyes—was the needle that popped that bubble of illusion forever. It was an uncomfortable feeling, and yet I was sure I had never learned something so important and there was still so much I needed to learn. Day after day, I chased that complex feeling into Riad El Solh’s square: to breathe the air, join the calls, distribute manouchés, and hold the hands of people I had never met, but with whom I felt the most intimate bond.

I reflcted that this feeling must be what people refer to when they speak of belonging to something greater than themselves. I had never had that feeling before; now, I am determined I will never be without it again. While the Lebanese government remains as broken as ever, this revolution has changed my way of thinking. Profound gratitude for all I had been given was my fist lesson. I learned both how to use my own voice for the sake of others and the value of timely silence, such that the raised voices of others can be heard most clearly. The power of words, speech, photography, and solidarity—spoken and implicit—was my second lesson.

Protesting with my Canon Sure Shot camera attached to my neck gave me a way to immortalize this historical moment. My photographs are tiny windows into the Lebanese revolution. When I look back at each of them, I can still feel the goosebumps running on my skin while capturing each shot.

I was invisible. Protesters were so invested in making their voices heard that all they saw was their raised wrists and all they heard was their synchronous chants. My pictures inspired me to believe in hope. Looking into each other’s eyes was enough for me to understand that we were going to get through this together. It is with this scared yet hopeful, sad yet optimistic group of protesters that I regained my feeling of hope. With every cry, the feeling of desperation and melancholy slowly faded

away. With each shot, I cemented our impact in history.

The photograph published here takes me back to that place of revolution. It shows a bustling van making a spectacular entrance into the herd of protesters. Young and old, women and men, Christian and Muslim: They are all fihting for the same reason. Their chants and heroic protest are all fueled by their love for their country. In this revolution, the only colors we could see were white, green, and red.

Over the past year, at the base of Riad El Solh’s statue, in his shadow and humbled by the conviction of my fellow citizens, I feel that a question has been posed to me about the kind of person I want to be. And I have my answer. I want to be the peacemaker the Lebanese people have for so long called for and deserved—not just in name but also in humble and unrelenting action—such that one day I may see that ambition through. Armed with this ambition, I will remain dedicated to the project of peace in Lebanon until it is only on days of celebration that mothers tell their daughters: “Meet me at Riad El Solh.”

FEBRUARY 21, 2023 TUFTS OBSERVER 13 VOICES

DESIGN BY ANTHONY DAVIS-PAIT, ART BY NOUR EL-SOLH

NOST AL

noun

a sentimental longing or wistful affection for the past, typically for a period or place with happy personal associations.

DESIGN BY INES WANG

TOP LEFT: PHOTO BY OLIVIA WHITE

LEFT: PHOTO BY NICOLE GARAY

RIGHT: PHOTO BY D GATE Ñ O

DESIGN BY INES WANG

TOP LEFT: PHOTO BY OLIVIA WHITE

LEFT: PHOTO BY NICOLE GARAY

RIGHT: PHOTO BY D GATE Ñ O

DESIGN BY INES WANG

LEFT: ART BY AUDREY NJO

RIGHT: ART BY OLIVIA WHITE

DESIGN BY INES WANG

LEFT: ART BY AUDREY NJO

RIGHT: ART BY OLIVIA WHITE

GREEN LINE GENTRIFICATION

THE RISK OF HOUSING DISPLACEMENT IN MEDFORD AND SOMERVILLE

By Tess Robinson

This past December, the fist departure from the new Medford/TuftsMBTA station generated much excitement, with students and community members crowding the inaugural 4:45 a.m. train. Among those present were US Senators Elizabeth Warren and Ed Markey, Governor Charlie Baker, Somerville Mayor Katjana Ballantyne, and TuftsPresident Tony Monaco. The departure was widely celebrated on Twitter and on local Boston radio coverage, but some Somerville and Medford community members, including some from Tufts,are worried about being priced out of housing as a result of the opening. While some were praising the extension, demonstrators from the Community Action Agency of Somerville attended the unveiling of the new station with posters and banners protesting rent increases near Green Line stations.

At the same time, easier access to the city of Boston through the Green Line Corridor will make Somerville more attractive to potential renters and businesses. According to a 2014 prediction by the Metropolitan Area Planning Council, the resulting increase in housing demand in the area will allow landlords to increase rent by as high as 67 percent in certain areas of Somerville, with an average rent increase of between 16–25 percent in areas within walking distance to the T stations. Urban Studies Professor Justin Hollander explained, “ The owners in the area are able to benefit from the increased mobility and an appreciation in the value of their prop-

erty… Renters benefit in the short term from increased amenity, but also may be pushed out from the increased rent.”

Ths phenomenon has created pressure on low- and moderate-income renters in the city, with several evictions already underway. Somerville is a city with high housing turnover, and with rent increases bringing in a newer, wealthier population to the city and pricing lowerincome renters out, the face of the city could quickly change, potentially reducing cultural diversity. Hollander noted the areas around the T station will likely not have the income diversity of other areas in Somerville, and income also carries a correlation with racial diversity. According to the Metropolitan Area Planning Council, “While displacement is largely driven by income disparities, the fact that higherincome households are disproportionately White and lower-income households are disproportionately non-White means that displacement risk also carries implications for the racial diversity of the GLX walksheds and the community as a whole.”

The new transportation corridor will also affect Tuftsstudents and faculty who live in the area, especially low-income students and staffmembers. One student who lives near two Green Line stations, Claire Puranananda, said their landlord has been increasing rent for the past two years in anticipation of the new stations. They said he also plans to keep increasing the rent until he reaches an increase of almost 17 percent of Puranananda’s

original rent price. Puranananda said, “If he’d raised [the rent] initially [to the full increased price]... [the former tenants] would have found a different place to live.” But with new students renting every year, it’s less likely that people will object to the yearly rent increases. “[He’s] ensuring that people will be willing to pay,” they said. In other words, increasing the rent in small increments right now disguises the ultimate burden of the full rent increase in the future—the brunt of which they say will be felt by Tuftsstudents in future classes. As Tuftsdoes not guarantee on-campus housing for upperclassmen, many students will be forced to contend with these higher rent prices upon moving off-ampus in junior year.

Puranananda predicts some students, especially low-income students, will have to choose between housing close to campus and housing that is affordable. They claim these choices may result in increased stress if students’ commutes to campus become longer, or if they receive insufficit aid to make their monthly rent payments. Responding to the issue of increased rent pressure on students, TuftsExecutive Director of Media Relations Patrick Collins wrote in a statement to the Observer, “Room and Board components of the Cost of Attendance and the Expected Family Contribution are calculated the same way” for on- and off-ampus students, “meaning the fiancial aid award is the same regardless of whether a student lives on- or off-ampus.” It remains to be seen if the

18 T UFTS OBSERVE R FEBRUARY 21, 2023 CAMPUS

room and board allowance portion of financial aid for off-ampus students will increase relative to rent increases.

Students who move away from T stations in pursuit of lower rent will also be less able to capitalize on the newly unveiled access to Boston. Ths is the irony of improved transportation: The gentrification that follows it may exclude the users it was built to assist. For Puranananda, who is sandwiched between two stations, the GLX presents a much more convenient path into Boston than the mile walk to Davis, but they wonder if the increased rent is worth the convenience for the infrequent luxury of day trips. “It’s nice to not have to walk to Davis… but I don’t go that much so I don’t know if paying the difference in rent is worth that,” Puranananda said.

SMFA-Tufts

Dual Degree student Ava Sakamoto emphasized the trade-offsof the opening. “ The new Green Line extension has defintely made the commute to SMFA easier— instead of being late to class by a whole hour, you can shave that down by 30–40 minutes.” The increased convenience of their commute comes with the increased burden of fiding affordable housing, however. Sakamoto said because “some of my friends who live off-ampus are facing rent increases,” they “decided to live on campus instead of search[ing] for an apartment.”

The MAPC anticipated increased gentrifiation and housing displacement in the Somerville area as a result of improved transportation. As early as 2014, they emphasized the need for 6,000 to 9,000

housing units in Somerville by roughly 2030, including an “adequate supply for moderate- and low-income households” to address the risk of housing displacement. Hollander echoed the sentiments of this report, explaining that “floding the market” with new housing units could reduce GLX-related rent increases over a sustained period.

Ultimately, many of the Green Line Extension’s critics are responding to the

to “produce more affordable housing… jobs… and other amenities.”

In response to gentrifiation in Union Square—another location of a new Green Line station—Goldman and other Somerville residents formed a coalition to negotiate a Community Benefits Agreement, a contract that allows developers to use city land in return for resources and money paid back to the community. In this way, she said, residents can protect the aspects of the community important to them and use money from the new infrastructure to fiht displacement.

Other organizers near Tuft’ campus are calling for rent control as another way to prevent displacement and keep housing affordable.

resulting gentrifiation and looking to preserve affordable housing for low- and moderate-income residents. According to Urban Studies Professor Laurie Goldman, who is also an affordable housing organizer, preserving affordable housing can be done by “mobiliz[ing] to create new institutions that influence [the] market and capture value.” In other words, community members must come together and put pressure on public and private institutions, either through community agreements or public ordinances, and encourage them

Nicole Eigbrett of the Community Action Agency of Somerville spoke about reversing the Massachusetts rent control ban in an interview with GBH, “We’re really fihting to liftthat ban on rent control that was passed in 1994 so cities and towns can have their own options for rent stabilization.” Some other anti-displacement measures published by Policy Link and the Chicago Rehab Network include just cause eviction controls, which prevent discriminatory evictions, and inclusionary zoning, which requires a certain percentage of new housing units to be reserved for lowand moderate-income tenants. Now, facing transportation-based gentrifiation, the Tuftsand Somerville communities must decide if any of these avenues can protect their residents against the threat of displacement.

FEBRUARY 21, 2023 TUFTS OBSERVER 19 CAMPUS

DESIGN BY MADISON CLOWES, ART BY NOUR EL-SOLH

SCENES FROM SOWA ANALYZING THE EXPANSION OF ARTS MARKETS

Whether it’s under the summer sun or below thousands of sparkling Christmas lights, Greater Boston residents know the feeling of discovering something personal and useful to them while perusing hundreds of small businesses. Whether someone is looking at curated collections of vintage clothes, handmade jewelry, or homeware, local markets act as distinct communities that foster the exchange of ideas and goods while helping local residents avoid supporting unethical fashion and manufacturing practices. However, though vintage and arts markets act as an excellent alternative to fast fashion, the expansion of these markets cannot be separated from the fact that they o!en harm lowincome neighborhoods.

"e South of Washington province of Boston, a#ectionately known as SoWa, has recently been celebrated for its in-

$ux of creativity and artistic endeavors. From May to October, the SoWa Open Market is open to the Boston community with over 100 regional and local vendors. "ese unique small businesses sell items ranging from celestial-themed jewelry to statement home decor made of dri!wood. Additionally, the SoWa Winter Festival allows local businesses to seize holiday sale opportunities for three weekends at the end of November and beginning of December. Both market events are located near SoWa’s vintage market, which is open year-round.

At the same time, vintage and art markets—along with the arrival of boutiques, yoga studios, and breweries— have played a part in the gentri%cation of neighborhoods like the South End. Gentri%cation is the entry of new, wealthier tenants into improved housing units and the establishment of new businesses in

poor urban areas, which eventually displaces current residents. SoWa and its formerly a#ordable housing market has changed throughout recent decades, from inhabiting low-income immigrant families in the 1950s to becoming a hotspot for the moneyed, artistic, and trendy lifestyle. "is reputation, in addition to its proximity to Downtown Boston, continues to attract Bostonians to the South End.

"e district has a large number of vendors in both seasonal and year-round markets. Chrissie Edgeworth, owner of Ramblejoy Jewelry Co, sells earrings and necklaces throughout Boston at SoWa’s Winter Market, Boston’s Women’s Market, and through the Bloom Collective—which hosts unique pop-up shops throughout Boston to showcase local businesses. Although her Etsy shop, established in 2020, opens her product to

ARTS & CULTURE

20 T UFTS OBSERVE R FEBRUARY 21, 2023

buyers across the country, Edgeworth prefers selling her jewelry locally. She explained she feels most supported as an artist in markets like SoWa, and that she appreciates the ability to share the stories of her cra! with customers who browse her stall and purchase her products. “In terms of support and community, the energy in in-person markets is a much more enriching platform,” Edgeworth said.

Freshman Arianna Shalhoub particularly enjoys buying from local artists. She said, “I am always inspired by other artists’ work, and it makes me happy when I can support them and make an impact to help them create more art in the future.” She further emphasized the

supporting the o!en hidden but harmful e#ects of the fast fashion industry.

"e intention of the fast fashion industry is to keep prices low and be in tune with current trends. In turn, this makes it di&cult for consumers to be informed about the unethical labor used to create products behind the scenes. In contrast, Ramblejoy Jewelry’s website contains brief summaries of where Edgeworth obtains her patterns and fabrics. She believes in the importance of sharing “what the whole behind the scenes process looks like” for her products. Unlike major retailers, she gives recognition to the artists and the locations from which the patterns in her products originate. Not only does this enhance the story of her cra!, but it also points the spotlight onto the stories of these artists and their careers. Artist Janine Lecour creates vibrant tropical-esque textiles that are inspired by colors and wildlife and is a contributing freelance surface pattern designer for Ramblejoy. Not only is her name displayed next to her art, but also a short blurb of her background and passions, and a link to her website and social media. SoWa markets regularly receive praise, including a recent highlight from the as a “must visit” open market in Boston. Vintage markets allow consumers to reconnect with past eras of clothing and give them another chance at life instead of being thrown away.

In a written statement to the , freshman Sanaa Gordon emphasized why shopping at $ea markets is so appealing. “I love clothes and the story they tell. I think that shopping in $ea markets allows me to explore clothes of a di#erent time and wear them again,” Gordon said. “When you have a piece of clothing that you got ‘secondhand,’ you are telling a story long forgotten.”

Underneath the growing appreciation for the explosion of small businesses in SoWa is the forgotten history of the

region. "e gentri%cation of SoWa began more than 40 years ago. When Pine Street Inn, Boston’s biggest homeless shelter, continued its mission to expand a#ordable housing to and beyond Harrison Avenue and onto 38-42 Upton Street, petitioners expressed a concern with having too many low-income residents. "eir “appreciation” for economic and racial diversity in their neighborhood only existed if newcomers weren’t too visible and seemed to blend in among the gentri%ers.

Currently, Ink Block, luxury Boston apartments in the South End, %nished construction in 2018 and are located where the original Boston Herald newspaper company building was. Although they include 51 a#ordable units, Ink Block apartments begin their one-bedroom apartment rental rates at $2,000 and go all the way up to $6,500 for two-bedroom apartments. What used to be considered a “skid row” (an urban, impoverished area) decades ago is now home to luxury apartments that the tenants of the district in the past would not be able to rent today.

"e changing cost of housing in the SoWa district impacts not only residents of the neighborhoods, but consumers and creators as well. As vintage markets have become more common and approachable for upper-class residents, the prices of their items have risen to match what these speci%c consumers can a#ord. Additionally, the value of real estate in lowincome areas has increased with their gentri%cation, and studios and galleries in SoWa are becoming %nancially inaccessible for artists to begin and promote their work.

SoWa’s art and vintage markets have been applauded for their ability to combine a variety of vendors that o#er a bene%cial exchange between local business and consumers. However, it’s important to recognize the circumstances for how and why SoWa markets exist today. To allow SoWa to continue evolving for its current residents and local businesses, its entire history must be recognized. Development can occur without displacement if at-risk residents have the opportunity to bene%t from it.

ARTS & CULTURE FEBRUARY 21, 2023 TUFTS OBSERVER 21

DESIGN BY HAMI TRINH, ART BY AUDREY NJO

One Eye One Eye

What I remember with one eye: the severe pain already forgotten, a doctor’s creased scrubs, ÿ ve tiny cracks on white walls, my mother holding me in her arms hastily on the way, the gravel small enough to slip in between lids but large enough to corrugate the membrane on the surface of my retina. Families of cockroaches escaped everywhere once the lights turned on. ° e day sweated without air conditioning.

Waking up with ooze pervading my bandaged eye, remembering how I will remember the days like they performed in my head, and how great it was to only have one functioning eye, since childhood memories are like cotton candies anyway. What is le˛ there sticks to your ÿ ngertips, and you lick it to taste its salty sweetness. Indeed, I had too much fun playing inside with my busy mother in my red-dotted dress, with only my le˛ eye alive. I danced like a pirate, rolling around on the ground, the pleasantly cold light wood ˝ oor. My childish sea roared.

Random Ajummas always said “what a cute little girl” to me in a language I had not yet learned to unravel, but when they opened their mouth, magpies lined up on the wire with their high pitches, especially when I masked my eye. Bit by bit I learned to decipher, as the grinning Ajummas always repeated, uttering the same scripts over and over again. Poking my eyes in the mirror, I thought this might be why the right one has no folds, unlike the other, which is doubled. But I don’t remember how my eye looked before, just like how it does not recall its healing.

22 T UFTS OBSERVE R FEBRUARY 21, 2023 POETRY &

PROSE

DESIGN BY ANASTASIA GLASS , ART BY MATILDA PENG

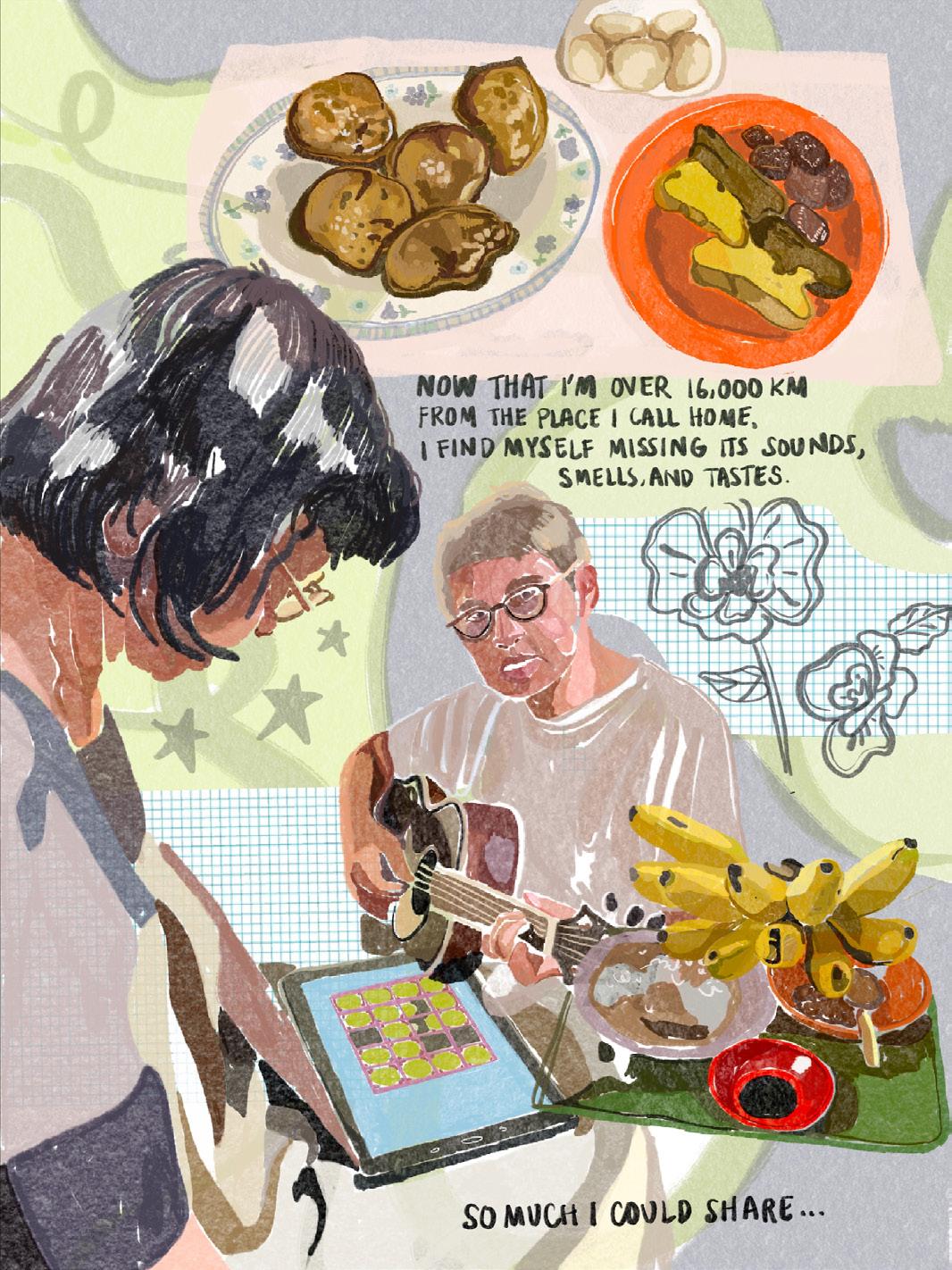

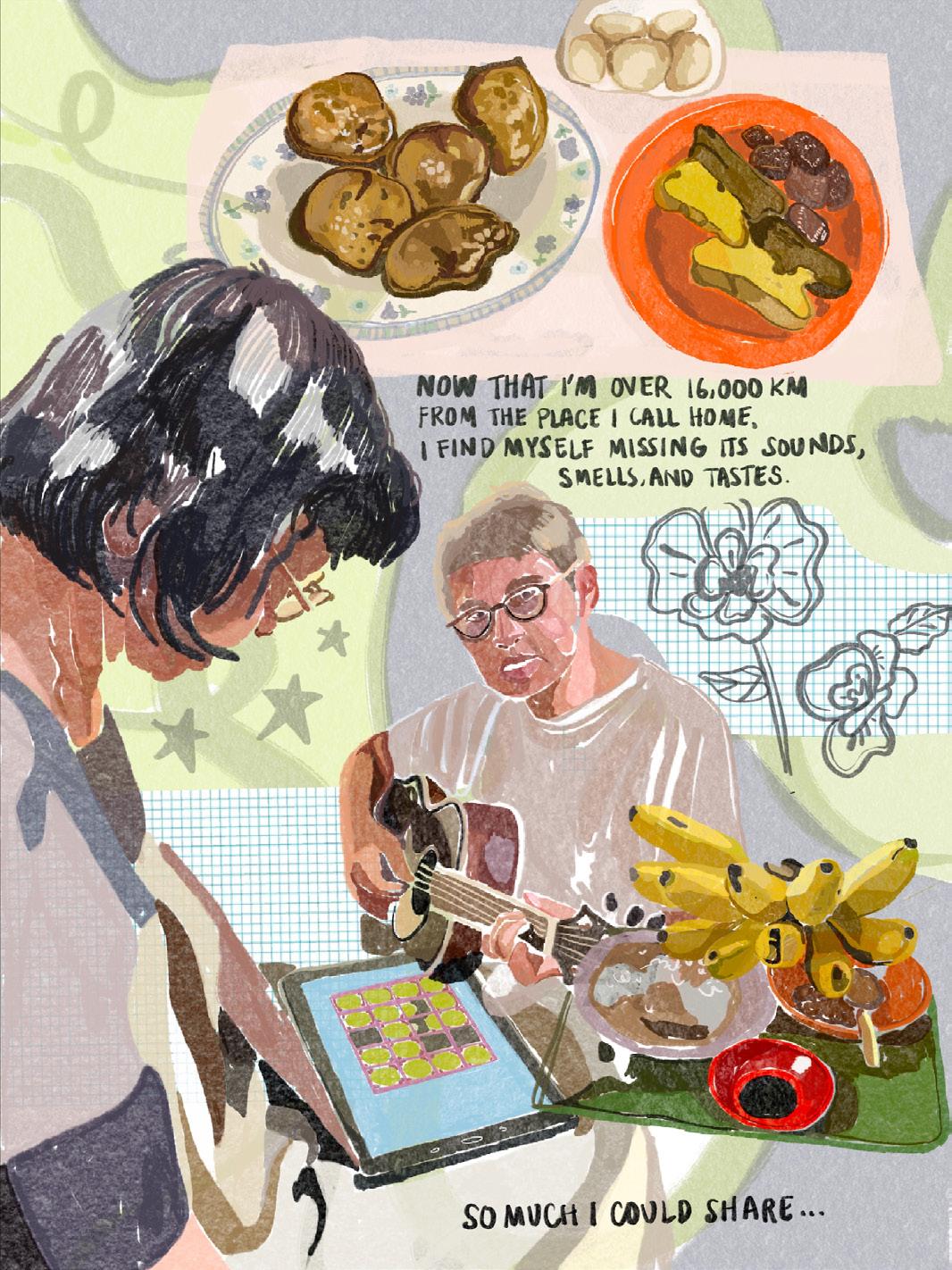

Through the Stomach

Warm-blooded animal brought to the cold— A snow-soaked Boston so unlike January in my hometown But new, too, is this warmth, Our foreheads tight together by the kitchen table—

You,

Once so far away, now Having crossed the continent, ° e shy season of ˝ irting, Even the shame, the fear of so˛ rejection, Here you stand Washing the dishes in my frigid dorm kitchen;

° e scene leaves a sweet taste in my mouth

Even more so than the bites

Of rainbow-sprinkled

Ice Cream

° at we shared, really more like ° e weight of

“Crema de Mariscos” stumbling Erred, between your lips

° e promise, open Pathway to your heart—

If only my skills

And Aui’s recipes Will su˙ ce.

POETRY & PROSE 23 T UFTS OBSERVE R FEBRUARY 21, 2023 DESIGN BY ANASTASIA GLASS , ART BY AIDAN CHANG

REFLECTIONS ON COLLECTIONS EXAMINING TUFT UNIVERSITY ART GALLERY’S SPRING EXHIBITION

The displays at the Tu!s University Art Gallery’s current spring exhibition take inspiration from items in one of the gallery’s lesser-known collections. Consisting of “some 200 objects that date from the "!h century BCE to the seventh century CE,” according to TUAG’s website, the antiquities collection hasn’t been displayed in the gallery since 1992. With the collection so historically underrepresented in exhibitions, the gallery has invited several artists to intervene—to produce artworks with the collection and Tu!s’ collecting practice as their focuses. Given the troubled history of the collection, the exhibition aims to encourage scrutiny and open conversations around TUAG and its collecting practices.

#e "rst display inside the door of the gallery is artist duo SANGREE’s work titled #e display incorporates pre-Columbian pieces from TUAG’s antiquities collection into their brand of modern-day clay work. From Nike slides made of marble to display platforms that resemble both Mayan temples and skatepark half-pipes, the entire display is rife with con$ations of the past and the present. Given that many of the pieces displayed don’t have their provenances listed, SANGREE plays with that uncertainty about the past to bring the collection objects into the present.

#e second display, titled , by artist Nicole Cherubini, encourages visitors to sit on intricately printed ceramic chairs and consider a collection of items on display. Cherubini selected her collection items by searching the

Tu!s collection database for items tagged as “vessels,” which includes a range of items from simple bowls to large amphoras and lamps. She juxtaposes the function of the chairs with the function of the “vessels” to direct attention not towards the objects’ histories or origins, but to their function and purpose in the collection.

The final display is NIC Kay’s , which features two larger-thanlife figures made of cloth and mats—one of a head and one of a faceless body. The collection pieces they’re based on, a minimalist stone head and a female figure made of terracotta, aren’t more than a few inches tall. Kay approached the collection looking for objects that resembled bodies and figures, and the display plays with the life objects take on (or lose) when removed from their cultural contexts.

At this point the exhibition appears to reach an end, but at the bottom of the stairs is the complementary part of the exhibition: the history of Tu!s’ permanent collection. #e walls of this room are covered in informative placards detailing the history of the collection, from the "rst painting of Hosea Ballou commissioned in

1874 to the digitization of the collection in 2019. It also tracks major legal and historical milestones in the world of antiquities collecting, situating Tu!s’

24 T UFTS OBSERVE R FEBRUARY 21, 2023 ARTS & CULTURE

antiquities within other historical discussions about museum and gallery collections. #is lower $oor, in conjunction with the upper level exhibition, brings to mind questions about the impact of Tu!s’ collecting practice and about collecting practices in general.

#e history of antiquities collection is fraught with cultural erasure and violence for the sake of national or scienti"c gain. #is results in many pieces being brought into museums and galleries with little to no record of ownership or even de"nitive place of origin. Craig Cipolla, Associate Professor of Anthropology at Tu!s, said, “#ose early collectors, their idea of what was valuable wasn’t the context that it was coming from, or sometimes even the country. #at wasn’t as important as the object itself … [and] the idea that motivated that o!entimes was that if they didn’t get it, someone else would.” As a result, art collectors o!en expressed this through violence towards colonized people, looting, and illegally selling deeply signi"cant objects to more a%uent, colonizing nations.

#e practice of looting and reselling art, despite major milestones like the UNESCO 1970 Convention, has remained under-regulated to this day—especially within antiquities markets. Antiquities dealers have historically been indicted for massive collections of stolen cultural objects, including, recently, infamous art dealer Michael Steinhardt.

In 2021, according to CNBC, Steinhardt “surrendered 180 stolen antiquities… valued at $70 million” which he

had been collecting for decades, including acquiring pieces from now-deceased patriarch of the Merrin Family, Edward Merrin. #e Merrin Family have been proli"c art dealers for decades, and members of the family have, throughout the years, donated the majority of the antiquities that are now in the Tu!s collection. Other pieces from the Merrins have repeatedly popped up in scandals like Steinhardt’s. According to CNBC, Steinhardt allegedly purchased a stolen antiquity from the Merrin Gallery for “$2.6 million in November 1991”—although it is not certain whether Merrin knew the nature of the piece he had acquired, and nothing illicit has been con"rmed about him or his gallery.

This level of systematic looting results in a violent disconnect between an object and its cultural context. According to Cipolla, the goal for art galleries then becomes to “reactivate these things in the living world, rather than being isolated from their relations with the rest of the world,” and that’s exactly what attempts to do. In a written statement to the Tufts Observer, Dina Deitsch, Director and Chief Curator at TUAG, said, “The installations are there to prompt questions and inquiry. It’s part of a long process of making this collection visible—the first was putting it online in 2019—so we can understand the histories around them better.” It has taken 10 years to put this exhibition together, and Deitsch and the dozens of others who worked on it aim to put as many eyes on the collection and the exhibition as possible.

For the past six years, Laura McDonald, Manager of Collections at TUAG, has focused on getting the collection on the radar of both students and scholars in the "eld. She said, “In order to get these objects out there into the conversations, we needed to display them.” As a result, McDonald has spent time coordinating research inquiries from interested scholars and students, and, according to a plaque within the exhibition, “enlisting faculty and students to help TUAG with provenance research is part of the due diligence e&orts that are critical if we hope to return objects to their rightful owners.”

Junior Kaitlyn Carril, who works on the Tufts Art Galleries Acquisition Committee and the Student Program -

ible to people. Carril said, “Just admitting that there’s faults in the Tufts collection of art objects and trying to redeem oneself—and not quietly too, very openly and publicly—I think that’s very courageous.”

#e conversations that this exhibition is raising are, to McDonald, a complement of more impactful changes within the institution. She said that the university no longer accepts items with unknown or uncertain provenances, and TUAG has switched its focus to exclusively contemporary art. McDonald has also encouraged the return of any objects in the collection that are claimed by other countries or groups. “We’re 40 years on from 1982 [when the UNESCO Convention was rati"ed in the US], so it’s a di&erent world now. #ere’s so much talk about repatriation,” she said. “My feeling would be that if there’s a country of origin that wants them back, we’re happy to give them back.”

Ultimately, the exhibition is a uni"ed push to create as much conversation around these issues as possible—especially since, according to McDonald, TUAG is “not going to have another exhibit like this for the foreseeable future.” From the con$ation of the past and present within SANGREE’s display to inquiries into function and provenance in Cherubini’s and Kay’s displays, the exhibition is already asking questions about the collection. However, moving forward, the implications of Tu!s’ collection and collecting practices is, according to McDonald, “an important conversation to have as an institution, not as the gallery or as a sta& member, but very much as an institution, because it’s all connected.”

FEBRUARY 21, 2023 TUFTS OBSERVER 25 DESIGN BY HAMI TRINH, ART BY D GATEÑO

THE OURANGER

LET’SDIRECT

Spoiler alert–it’s not each other.

By Leah Cohen

ABOUTCOVIDTOWARD REAL ENEMY. OPINION 26 T UFTS OBSERVE R FEBRUARY 21, 2023

About a month ago, Philadelphia-based socialist activist and writer Mindy Isser posted a since-deleted tweet which in part read, “covid is both serious and not ‘over’ but i’m not sure what the point is of all the fear-mongering posts about how permanently sick you’ll be if you get it. most of us have already gotten it!” While the tweet is no longer available on the platform, a litany of replies from a mixture of activists, high-profile media professionals (such as the Washington Post’s Taylor Lorenz), and members of the Extremely Online remain. They include accusations that Isser is an ableist, an anti-vaxxer, an anti-masker, a fake socialist, and even a eugenicist; outcries for the Philly Democratic Socialists of America chapter Isser works with to discipline her or formally expel her; and personal attacks on her, her husband and their ability to parent their five-month-old.

I’m going to say something that may be controversial: I have a hard time believing Mindy Isser is a eugenicist. The National Human Genome Research Institute defies a eugenicist as someone who believes they can “perfect human beings and eliminate so-called social ills through genetics and heredity. They [believe] the use of methods such as involuntary sterilization, segregation and social exclusion [will] rid society of individuals deemed by them to be unfit.” If you don’t like the government’s defintion, Merriam-Webster defies eugenics as “the practice or advocacy of controlled selective breeding of human populations (as by sterilization) to improve the population’s genetic composition.” I feel there is a crucial distinction between white supremacist bio-fascists and Twitter users who warn against the harm of fearmongering.

My stake in this conversation is primarily discursive in nature; as a college student who barely understands biology, I cannot even begin to define the proper way to handle COVID from a public health policy perspective, but what I can do, as a sociologist and digital scholar, is point out a pattern of aggression online that borders on abuse and is also entirely unproductive for the objectives of the public health movement.

Th online discourse surrounding COVID mitigation (or rather, the lack thereof) and the often-ignored pandemic has completely broken down into nuanceless shouting and name-calling, with no room for empathy or an understanding that there is no one-size-fits-all solution to this public health crisis. There are essentially two dominant factions with few in between (Mindy Isser and yours truly being two of those few). One faction believes that the pandemic is over, or at least functionally over, and that mitigation tactics such as masking, surveillance testing, limiting capacity in rooms, and avoiding indoor events are no longer necessary or effective in stopping the spread of COVID-19. Ths faction tends to believe vaccines are effective enough at mitigation. Ths view accounts for a majority of liberal Americans and is reflcted in the policy choices made by Tufts(not all of which I agree with). It’s important to clarify that this group is distinguishable from the early COVID deniers of the far right; the group I am referring to understands COVID was harmful and devastating, but believes it is time to move on.

Then there is the other faction, which seems to be a very vocal and Extremely Online minority: the group that remains highly fearful of catching COVID and essentially still lives their lives as if in the pre-vaccine era. Many people belonging to this group are immunocompromised, disabled, or live with someone who is at a higher health risk, and it is completely understandable they may feel a heightened level of anxiety given the failure of the government at every juncture to meaningfully halt this pandemic. However, some members of this group, who may or may not be medically vulnerable in this way, have taken it upon themselves to police the behaviors of everyone around them, as well as spread extreme rhetoric online that is incompatible with public health guidance. Ths sub-group has a tendency to read and share every study they come across that claims COVID causes irreversible and permanently disabling damage to the body, even for vaccinated individuals (sometimes citing studies that are in direct contrast with other research). Ths group also has a predilection for assuming ma-

licious intent of anyone who employs a different strategy than themselves. They tend to take their frustration out on those people through online harassment that borders on abuse. Ths is who Isser is addressing in her tweet—and who has now designated Isser as a eugenicist.

I was apprehensive to approach this conversation for two reasons: One, I do not like the idea of denying anyone—and particularly a group that is frequently marginalized by both public policy and society writ large, such as the disability justice community—the right to speak their truth and vent about their frustrations and anxieties living in a world that appears to have functionally abandoned them. I want to be very clear: I do not want my argument to be misconstrued as an attempt to silence disability justice advocates. COVID has devastated humankind in ways we still cannot begin to fathom and, like all epidemics, has disproportionately impacted those who already live at the margins. People should feel empowered to speak about that anxiety and frustration without fear.