Tufts Observer

Sadie Schmitz

Nora Bitar

Jules Zinn-Rowthorn

Miles

Valdebenito

Madison Clowes & Rachel Li

Anastasia

James Urquhart

Lily

Ishaan Rajiv Rajabali

Emilia Ferreira

staff

Editor-in-Chief

Miles Kendrick

Editor Emeritus

Ashlie Doucette

Managing Editors

Caroline Lloyd-Jones

Sofia Valdebenito

Creative Directors

Madison Clowes

Rachel Li

Feature Editors

Anna Farrell

Mia Ivatury

News Editors

Wellesley Papagni

Chloe Thurmgreene

Arts & Culture Editors

Siena Cohen

Talia Tepper

Poetry and Prose Editors

Demi Ajibola

Peaches Wright

Voices Editors

Devon Chang

Veronica Habashy

Crossword Editors

Max Greenstein

Elanor Kinderman

Lead Copy

Editors

Andrea Li

Laxmi McCulloch

Copy Editors

Abilene Adelman

Isabella Tepper

Meredith Boyle

Elissa Fan

Taryn Morlock

Whitney Turner

Art Directors

Maria Sokolowski

Leila Toubia

Staff Writers

Abilene Adelman

Samira Amin

Emma Castro

Ishana Dasgupta

Eylul Karakaya

Emilia Ferreira

Elanor Kinderman

Jason Lee

Nina Nehra

Alec Rosenthal

Selin Ruso

Addy Samway

Sadie Schmitz

Lecia Sun

James Urquhart

Gigi Appelbaum

Rohaan Iyer

Jules Zinn Rowthorn

Designers

Opinion Editors

Lucie Babcock

Ela Nalbantoglu

Campus Editors

Henry Estes

Kerrera Jackson

Emma Dawson-Webb

Meg Duncan

Ahmed Fouad

Anya Glass

Ella Hubbard

Joey Marmo

Ruby Offer

Katie Ogden

Emma Selesnick

Meera Trujillo

Publicity Directors

Carson Komishane

Alexa Licairac

Publicity Team

Sophia Caro

Caleb Nagel

Radhika Yeddanapudi

Staff Artists

Amanda Chen

Cherry Chen

Sophia Chen

Jaylin Cho

Meg Duncan

Ella Hubbard

Isabel Mahoney

Ruby Marlow

Khrystyna Saiko

Yayla Tur

Elika Wilson

Felix Yu

Paola Silva Lizarraga

Dena Zakim

Lead Website Managers

Andie Cabochan

Dylan Perkins

Website Managers

Vina Le

Madoka Sho

Treasurer

Andrea Li

Refuse (verb) [Ri-fyuz]: To express oneself as unwilling to accept.

Refuse (noun) [Re-fyus]: The worthless or useless part of seomthing.

Contributors

Nora Bitar

Ishaan Rajiv Rajabali

Lily Rogers

LETTER FROM THE EDITORS

Dearest Observers,

Lately, we’ve been thinking a lot about the second law of thermodynamics. It states that disorder or randomness in an isolated system can only increase over time. Entropy, the scale that measures that disorder or randomness, can only be reduced by force. It doesn’t require effort to shatter a glass, but it does to put it back together again. Dictated by this fundamental physical principle, the universe perpetually descends into chaos, an exponential amalgamation of clutter, trash, and refuse.

This semester has been our best attempt at pushing back against this death spiral into disarray. Every three weeks, this group of writers, artists, designers, and visionaries comes together and puts energy into the creation of something much bigger than us. Amidst a universe of expanding chaos, we refuse to accept the natural flow of entropy, opting instead to keep on fighting to make sense of the sometimes (often) insensible.

Indeed, this issue grapples with many of the seemingly insensible cases of refuse. We explore the body’s rejection of our own essential organs, the devaluation of women in sports, and the resistance to modern technological norms that confine us. We ask, how can refusal subjugate or empower, and who falls victim to Earth’s entropic embrace of the discarded? Throughout it all, we stay true to the Observer’s mission, aiming to uplift marginalized voices through the use of journalism, art, and creative writing.

This volume of the Observer has been a testament to us staff members and to the greater Tufts community on the power of long form journalism and clever issue themes. We began this semester examining our Function as an outlet of discourse, fed by the Soup of a staff that kept us warm entering the frigid midterm-autumn air. Then, we revisited our Root(s), as we have been all year (it is our 130th birthday, you know). Although this chapter is coming to a close, we Refuse to view it as the end—because, dear Observers, we are just getting started.

Until next semester…

Observantly yOurs, Miles, Caroline, and Sofia

Dear reader,

Refuse has an overlooked second definition, a noun meaning “matter thrown away or rejected as worthless.” I think this noun form is so compelling because what is the aftereffect of refusal if not precisely what its noun describes? Refuse is such a beautiful manifestation of its typical definition—that which has been refused—and reminds me how delightful the English language can be sometimes.

Evidently, this issue makes me think a lot about trash: what we consider to be trash, how we experience it, what we do with it. In this way, refuse is more relevant now than ever before: we produce an ever-multiplying amount of material, a lot of which becomes waste for someone to deal with.

Recently, I had an overwhelming urge to declutter everything in my room. Old birthday cards from names I don’t recognize anymore, piles of books accumulating dust, homework assignments dating back to elementary school. All of these things just weighing me down. After amassing a comical amount of refuse from my years of hoarding, it all suddenly seemed so silly to me. Why do we keep things that are just things? Why do we buy, consume, hoard, buy again? Why do we always feel like we lack something, as if a purchase is going to solve all our problems?

I think we’re overdue for a reckoning with our patterns of consumption and discard, yes, to be a little more thrifty in the face of Shein landfills, but also to change the way we even conceptualize garbage.

Everything we refuse still has to be accepted by someone or something else, and this acceptance always looks different. One of the ways this acceptance manifests is through ruderal ecology. Anthropologist Bettina Stoetzer discusses how the term ruderal ecology was initially used in Berlin to describe the ecologies which emerged organically from and amongst the rubble of World War 2. In their recovery from war,

the government recycled rubble to rebuild roads and landscaped them to build rubble mountains. The government tried to manufacture the greening of these mountains, but the rubble had its own life: new plants from around the world, travelled on army wagons or the boots of refugees, found homes in the rubble mountains and persist today as enduring members of the Berlin landscape. I find the ruderal to be so relevant maybe because of how it challenges refuse; that a city could embrace its own rubble and seeds left by passersby to create something larger and more meaningful than the sum of its parts.

It makes me wonder, if we left things with the space to grow, change, self-determine, what would they look like? The back cover of this issue depicts the Nakagin Capsule Tower, which was at the center of the Metabolist architectural movement in Japan, a movement which believed buildings should be able to adapt and evolve like living organisms: to metabolize. The capsules in the tower were supposed to change every 25 years to adjust to the needs of its residents, so as it became obsolete, its components could be modified. Unfortunately, the tower’s metabolism was never fully realized. It was demolished recently and became, too, a part of our growing rubble. I think the Metabolists were onto something, but I also don’t know how important it is for a building to be able to act like a living organism when there are already plenty of living organisms deciding its fate. People are who really self-determine, who refuse. I guess we have some choices to make.

Always refusing, Madison & Rachel

Tufts Tackles Tuition:

Progressive or Performative?

By Jason Lee

On an otherwise typical September day, junior Silas Summers received a phone call from home. “Have you heard of this? Do you know how the application works?” his mom inquired. She was referring to the blockbuster announcement that had just appeared in every Tufts student and parent inbox: “Tufts Will Be TuitionFree for U.S. Families Earning Less Than $150,000.” The news spread quickly around campus—Tufts, ranked the eighth most expensive college in the US, with a $93,000 cost of attendance, would be going tuition-free.

“Consequently, keeping up with commitment to affordability is necessary to survive in the elite college market.”

trary.” This uncertainty is rooted in Tufts’ long-standing commitment “to meeting 100% of demonstrated need for all admitted students.” Under the current system, a student would submit the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) for federal aid, and the College Scholarship Service Profile (CSS) for institutional aid, which is financial assistance provided directly from the university. Around 40 percent of students currently receive grants, which do not need to be repaid, but loans remain a component of financial aid packages for families earning above $60,000. Now, families with typical assets earning under $150,000 can follow a simpler premise: their child’s tuition will be fully covered by aid packages consisting of grants, loans, and work-study, which provides eligible students with part-time jobs to cover expenses.

The Tufts administration presented the Tufts Tuition Pact as a stride toward improved higher education accessibility.

“Through the Tufts Tuition Pact, families making less than $150,000, with typical assets, will—at a minimum—have tuition waived,” wrote Dean of Admissions JT Duck, in a statement to the Tufts Observer Though Tufts’ definition of “typical assets” is not publicly available, the $150,000 cutoff presents an eye-catching appeal to affordability. Duck explained, “A key goal of the Tufts Tuition Pact is to send a strong, simple message that cost should not deter talented students from applying.”

Tufts students are both hopeful and critical. “I’ve always been a fan of the Tufts financial aid system, because they will meet 100 percent of your needs once you get accepted,” said Summers. Despite this approval, the new policy “just seems arbi -

In the past couple of years, an array of top private universities have announced similar tuition commitments, including MIT and Harvard, which, starting last fall, are tuition-free for families making less than $200,000. In this landscape, the Tufts Tuition Pact appears neither particularly unique nor bold. With college affordability at the forefront of conversations surrounding the worth of a university degree, the messaging surrounding affordability has become essential and turned into an arms race among prestigious schools. This competition is characterized by tuition discounting. Like Tufts, many private universities charge high tuition prices but heavily offset them with aid. The national average tuition discount rate for private universities has peaked at 56.3 percent, meaning that over half of the listed tuition is not actually charged. As tuition sticker prices increase, so do discount rates.

Tuition-free policies serve as a simple way to cut through pricing complexities and emphasize affordability as an institutional ethos. With an endowment of $2.6 billion—tiny relative to Harvard’s $53.2 billion or MIT’s $27.4 billion—Tufts lacks its peers’ financial safeguard and ability to provide aid. As Tufts Profes-

sor of Entrepreneurial Marketing Gavin Finn explained, “Announcing the policy helps Tufts keep pace and also puts itself in that group of top-tier universities, while signaling that it is committed to access and affordability on par with its other choices that applicants have.” Consequently, keeping up with commitment to affordability is necessary to survive in the elite college market.

Unlike Harvard or MIT, which are need-blind, Tufts’ admissions practices are need-aware, meaning that admissions officers have access to whether an applicant requires aid, which can influence acceptance decisions. With Tufts’ relatively smaller endowment, this access can help the administration allocate financial aid funds more conservatively. Need-awareness engenders an unspoken trade-off: everyone who is accepted will have their demonstrated need fully met, but admission to low-income applicants may be reduced.

Junior Damian Curt factored in Tufts’ financial aid system in his college decision. “[Tufts’ financial aid promise] was a huge determining factor in how affordable it was,” he said. Still, he remains suspicious of trade-offs. “On the surface, [the Tufts Tuition Pact] is good, but it begs the question of if [the admissions office] is going to start accepting more people who make over [$150 thousand annually] and marginalize against medium- to lower-income families.”

This would explain why the Tufts student body is skewed towards wealthy backgrounds. 77 percent of Tufts students come from families in the top 20 percent, with 46 percent of the newest Tufts class having attended private high school, compared to only 9 percent of American K-12 students who attend private school. Given Tufts’ more prominent relationship with private and boarding schools, students from public high schools may have a tougher time even discovering Tufts. Curt, who attended public high school in Chicago, experienced this difficulty himself, saying,“I heard about Tufts because my

mom’s friend went here. I had the privilege of personal exposure to this smaller school that I wouldn’t have known about otherwise.” However, Curt believes the new policy could broaden access and better position the university to receive applications from less privileged groups.

Duck concurred, stating, “Tufts has expanded its school counselor and college access advisor mailing list to include more schools in the South and Southwest and schools in rural communities across the country that might not have previously sent applicants to Tufts.” Outreach to more communities could result in a more diverse applicant pool, but ultimately, the admissions office determines who is accepted.

“The Tufts Tuition Pact erects a tradeoff: a hard cutoff allows for simple, brand-friendly messaging, but disproportionately harms those just above it. ”

Beyond bias against lower-income families, this policy can disproportionately harm those above the threshold—more specifically, those just above the threshold. Consider two families: one earning $149,000 a year, the other $151,000, both having typical assets. They are virtually identical, but according to the Net Tuition Calculator, the family earning $149,000 can expect to contribute $24,500, while the family

earning $151,000 might contribute closer to $48,100.

“When my mom introduced it to me, I was already skeptical, because I felt like the school would then just accept fewer people whose families make under the $150,000 mark,” said Summers. The $150,000 threshold makes the policy marketable, but also creates a hard cutoff, resulting in a benefit cliff, which is the sudden decrease in benefits received as a result of a small increase in earnings. Cliffs are contentious because, in this case, they could disincentivize upward mobility and pressure parents to manage their income such that they receive the benefits. Under the previous system, the Expected Family Contributions increased gradually as income rose, so a $2,000 raise in income might’ve led to a couple of hundred more dollars in tuition, not tens of thousands. The Tufts Tuition Pact erects a trade-off: a hard cutoff allows for simple, brand-friendly messaging, but disproportionately harms those just above it.

While the new policy shines a flashlight on domestic affordability, it casts an equal shadow on inaccessibility for international students, who comprise 13 percent of the undergraduate population. For them, the financial reality of Tufts remains unchanged. Unlike US citizens, international students cannot file the FAFSA to receive federal aid. Although international students are included in Tufts’ promise to meet 100 percent of demonstrated financial need, and Tufts can provide them with institutional aid, it can only be requested during the initial application process, not after admission, leaving a Tufts education prohibitively expensive for middle-income international families.

“Right from the start, it’s just an entirely different process,” said Luisa Garciarramos. A sophomore from Mexico City, Garciarramos came to Tufts to study cognitive and brain science, a discipline not widely available in her home country. Studying in the US comes with limited financing options. “International

students have to earn more meritocracybased scholarships to stay in the US for college if they can’t afford it,” she explained.

These constraints polarize the socioeconomic background of the international student body. “It’s not a rare thing to see a US citizen with financial aid,” Garciarramos said. “Whereas with international students, [they] are almost always upper class. Or, you see lowerclass international students who are here with special scholarships. But I definitely don’t think it’s a super common thing to see middle-class international students on financial aid here.”

If the Tufts Tuition Pact aims to bolster access for lower- and middle-income families, its impact is imbalanced. Tufts maintains its aid commitment to all students, and Duck noted that the Tufts Tuition Pact’s message “will enable us to be more effective in reaching new geographic communities.” Still, international students express doubt that this outreach will convert into meaningful financial accessibility for them.

The optics surrounding higher education accessibility are especially pertinent following the 2023 Supreme Court ruling against the use of affirmative action in college admissions decisions. A spotlight has shone on elite colleges to showcase their continued commitment to diversity, and affordability for the middle class is one politically palatable way to do so.

In response to the Supreme Court decision, the Department of Justice released guidance for universities navigating the pursuit of diversity, with one statement reading, “Colleges and universities may also choose to focus on providing students with need-based financial support that allows them not just to enroll, but to thrive.” Income-based thresholds are cut and dry, and tangibly demonstrate a concern for underadvantaged groups. Beyond the realm of financial aid, tuition commitments function, in part, as a risk management strategy to protect a university’s reputation.

A recent example comes from the University of Michigan, whose Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion office and programming have been discontinued following political pressure. The Guardian reports, “Since the supreme court [sic] ended affirmative action in 2023, programs geared towards diversity have been targeted by conservative groups … The university said that it will now focus on student-facing programs, including expanding financial aid.” With the Tuition Pact, Tufts may be following a similar protocol.

“‘These actions demonstrate a commitment beyond mere rhetoric, differentiating schools that talk about access from those that actively invest in it.’”

Many students, like Otávio Vieira, a sophomore from São Paulo, are optimis tic about the new policy. He sees value in the initiative, especially relative to the higher education model in Brazil. “The best university in South America for many consecutive years was the Univer sity of São Paulo, … completely tuitionfree and allow[ing] people to go to school from all parts of the world and get a world-class education for free.” He noted the limits of a fully free model, “Because people who can pay are not paying, it’s really, really underfunded.” He expressed that, in his opinion, the fairest system is one that charges those who can pay and subsidizes the rest.

For Curt, the Tufts Tuition Pact is “a step in the right direction.” He acknowledged how the optics factor in, saying, “It is naturally going to be alluring in a media sense. But at the end of the day, I think it is more accessible.” Finn also expressed his support of Tufts’ mission. “These actions demonstrate a commitment beyond mere rhetoric, differentiating schools that talk about access from those that actively invest in it.”

Summers, who agreed with the policy at face value, remains skeptical. “When my mom called me about this, she was really excited … I’m just fully believing that we will see more of a wealth inequality at Tufts—that was the first thing that came into my mind.”

As a whole, these perspectives suggest that the Tufts Tuition Pact is both exciting and unnerving. It may ease the burdens for some families, but it also leaves structural inequities untouched. Citizenship, need-aware admissions, school pipelines, and an income cliff will continue to determine who applies to Tufts and who can enroll. Whether the Tufts Tuition Pact will become more than an enticing headline will depend on the work that follows. The

DESIGN BY JOEY MARMO, ART BY JAYLIN CHO

Waste

By Sadie Schmitz

turning it on, turning it back off again. Wear dirty socks. Register for classes. Apply for a job. Scrub at my teeth. Home for the holidays. Slog on. I wish that it was September again.

I call my mother. Turn on the oven. Read the news. Walk to class. I have done nothing that I want to do. Melting into the asphalt. Sinking into the tar. Can’t walk fast enough.

Winter wraps around me like Irish ivy, tangling over my ribs. Autumn has once again ebbed into December and the rhubarb stain coating the earth has gone brown. The incessant passage of time. Spidery and grayed. Withered and listless. My nose starting to run at night.

DESIGN BY EMMA SELESNICK, ART BY YAYLA TUR

PUTREFACTION

By Nora Bitar

Te obsidian sky was bleeding lazily into the mahogany of dawn as she stood in a pile of lifeless autumn debris. A light breeze cut across her face, her eyes tearing up as a piece of her hair caught in her lips, chapped and faky. She spat out the strand, a brief moment of resoluteness.

As she stood planted in the dirt, her body felt heavy, like the weight of a depraved soul doggedly gripping the last pathetic ledge of daylight before his impending fall. She was flled with a sense of impending dread that threaded its way up the back of her spine and weaved its way into her head.

Pine branches extended all around her, swaying back and forth like the arms of a scarecrow seesawing in the wind. Te trees’ colossal limbs caged her small body in a macabre shadow. She shivered, and her teeth rattled against each other like a snake was slivering up her throat and tickling her mouth. Tat same sense of dread circled around in her head, dizzying her. But she ignored it. Te buzz of the cicadas drummed in her ears, vibrating obnoxiously and silencing her thoughts.

It was midday. Her shoes were rooted in the dirt, frozen, unmoved. She could feel the soles of her shoes digging into the ground like a rake, penetrating deeper and deeper, forming an indent that burrowed her whole body down a few inches. Te harsh, beating rays of the sun peaked through the trees, lacquering her tender face with a blinding red membrane. Her burnt skin peeled of her in repulsive chunks that slid down her cheeks like bloody tears. She was unanchored from her body, shaking, unsure if three or four or more days had passed. She could feel her arms falling asleep, hanging in a state of precarious paralysis. Her fngers were still

viable, shaking haphazardly from the cold, convulsing, seizing. Her thoughts were unmoored, aimlessly ricocheting around in her skull, impossible to decipher except for one voice begging her:

Don’t move. And she would not. It did not matter that her heart was still beating. To move would be to resuscitate a dead body that had already begun to fuse with the earth beneath it. To move would mean to decide. ***

Te sky was pitch black, inky, charcoal. And it was cold. Bullets of hail incessantly pelted her faky, dead skin. Te ends of her frozen fngers were hardened, completely blackened, burnt ash.

She had ceased to exist as a person. She was a shadow, a whisper, layers of sinew and bone that took up a few feet of space, incarcerated in a farfung pine tree forest that was nowhere, or nothing, really. If someone did come by, what would they see but a taxidermist’s mount? Every moment that she did not move, she melted more and more into the mud and the dirty snow on the forest foor. Chained, trapped, crumbling.

***

A frigid breeze coated her skin, as the blinding green pine needles and fower petals sparkled with a sickly vibrancy. Spring had fnally beaten the stubborn chill of winter. But what winter, she was clueless. How many springs had passed since she set her feet down? Two, three, ten? She was unsure. Her body had molded into a cast with the muddy earth. Tufs of hair and dead skin scattered across the ground. As the merciful cover of snow melted, there she remained: decomposed, decayed, disintegrated. Weeks, months, years, an eternity. Degenerated. Corroded. Withered. Spoiled. Deceased. She would exist in this catatonic state forever—her rotting mind in her rotted skull underneath her rotted skin. She had made only one decision her entire life: to perish while air still escaped from her lungs. And now, her ultimate decay was nearing.

***

It was dawn again. Te sky was stained with blood. Dead leaves shrouded the forest foor. On the ground, there was a deep hole covered with leaves, hidden. It would remain there, just below the surface. Forever.

The Aesthetic Trap

CBy Samira Amin

lean girl, mob wife, boho chic, co quette, cottage core. It’s 2025, and nothing exists outside an aesthetic anymore. Every outfit, playlist, and person ality can be neatly labeled, hashtagged, and sold back to you as belonging. You don’t just dress a certain way; you subscribe to an entire genre of self. is obsessed with having the next new thing—a demand the fast-fashion industry is all too happy to satisfy. Nowhere is this clearer than in the relentless turnover of aesthetics on social media. Microtrends, the tiny aesthetic fads built around one lip combo, one hairstyle, or one oddly specific color palette, rise and fall so fast that by the time your Sephora order arrives, the look that inspired it can already feel embarrassing or overdone. What used to feel like gradual cultural shifts now feel more like algorithmic spikes, with style treated as clickbait for content, rather than a form of creative expression. Fast fashion slots neatly into this rhythm, churning out new iterations of microtrends so fast you

lighting. This is described as a beauty paradox: women are expected to meet very high appearance standards but must do so while pretending not to try, because putting effort into one’s appearance is often misread as insecurity or vanity. The language of ‘clean’ adds another layer. If some girls are ‘clean,’ others must, by default, be dirty. Girls with acne, textured hair, or fewer resources are positioned outside the ideal.

fall into the trap, too. One TikTok ‘must-have’ is often all it takes for me to hit ‘checkout.’ Half my closet now reads like an archive of microtrends that expired before I even wore them. But the real issue isn’t just personal regret or overconsumption. The problem is that every time a new aesthetic goes viral, certain bodies, identities, and cultures are quietly marked as outda-

clean girl aesthetic, often attributed to figures like Sofia Richie and Hailey Bieber, crystallizes this algorithm-driven beauty standard in one deceptively simple look. On the surface, it is minimalist: slicked-back hair, dewy skin, neutral tones, tidy athleisure. Online, she is framed as natural, low-maintenance, and disciplined—a girl whose life is uncluttered, whose pores are invisible, whose wardro-

Despite appearing universal and clean, the clean girl aesthetic is built on racialized aesthetics that have been selectively validated and repackaged for mainstream consumption. Many of its features—sleek buns, gold hoop earrings, thick brows—have long histories in Black, Latina, and South Asian communities. For years, these same styles were policed as “unprofessional,” “ghetto,” or “too ethnic” when worn by women of color, attracting school dress codes, workplace penalties, and social stigma. Now, when co-opted by thin, affluent, predominantly white influencers, they are rebranded as chic and elevated. The cultural roots are flattened into a stolen aesthetic, and the original wearers are sidelined or erased.

This is not just a matter of credit or inspiration. When a look moves from stigmatized on a Black or Brown body to aspirational on a white one, it reveals how trends can reinforce existing power structures. How can my hair-oiling routine be dismissed as greasy or unprofessional, but become a wellness ritual when a white influencer rebrands it? Trend cycles do not merely evolve; they choose which bodies get to be seen as stylish and which remain policed, even when wearing the same hoops and the same bun.

exclusion doesn’t stop at race; it appears in who can afford to participate. Conforming to a trend is a social shortcut: an instant way to signal that you are part of the cultural conversation, that you “get it.” Clothes and makeup become proof of fluency in the language of the cost of that fluency is disproKeeping up with constantly shifting looks requires disposable income, time to watch and interpret trends, and access to the ‘right’ shops and products. For people working multiple jobs, saving money, or caring for families, the demand to update one’s wardrobe every few weeks is not just impractical but impossible.

Fast fashion becomes the place you turn to when the expectation to refresh your look never stops. Their business model depends on producing huge volumes of trend-driven garments at very low costs, shortening design-to-shelf timelines so that TikTok aesthetics show up on the high street almost in real time. Cheapness lets consumers keep playing catch-up without fully going broke, but it also normalizes rapid disposal and constant replacement. A dress bought for one microtrend is rarely expected to stick around for the next.

This is not accidental waste; it is the engine of consumer capitalism. The fashion and beauty industries do not profit when people feel satisfied with what they own or how they look. They profit when people feel just behind the curve, just shy of the ideal, just one purchase away from being fully ‘in.’ Microtrends turn that feeling into a weekly subscription.

For most of history, though, trends did not move like this. Fashion theorists have long described a five-stage lifecycle of trends: introduction, rise, peak, decline, and obsolescence, a process that historically played out across years or even decades. Classic styles—from 1950s hourglass dresses to 1990s minimalism—once defined eras. Trends were filtered primarily through fashion shows, magazines, and red carpets, with cycles that tended to last around 20 years. When I was growing up, my grandmother kept a corkboard in her bedroom covered with clippings from ma-

gazines and newspapers—her own analo gue version of Pinterest. She still adds to it today. Trends on that board move at a hu man pace: they arrive slowly, overlap, and linger. Today, social media feeds function as real-time, personalised trend pipelines, dictating what’s ‘in’ and ‘out at a pace no print editorial schedule can match.

matically, the impact isn’t confined to our closets; it seeps into how we think about our bodies, our faces, and what we believe we should look like. Psychological studies link heavy social media use to greater in ternalization of narrow beauty ideals and increased body dissatisfaction. When your TikTok “For You” page is a never-ending reel of ‘perfect’ skin, curated neutral wardrobes, and surgically precise faces, it’s easy to mistake an algorithmic pattern for a universal standard.

Influencers sit at the centre of this machinery. A single viral video can sell out a product or silhouette within hours, turning individual taste into mass behaviour. But the logic cuts both ways: the moment an aesthetic saturates the feed, it can flip from aspirational to cringe, and the people who bought into it are most literally left holding the bag.

So how do we step off the treadmill without pretending trends don’t exist? One starting point is critical literacy: learning to see curated images as constructed scenes, not natural baselines. The shift from “why don’t I look like that?” to “what work and money went into making that image?” can loosen society’s chokehold on aspirational aesthetics. When we recognise how speed, race, and class shape what feels aspirational, it becomes easier to resist the pressure to constantly update ourselves in response. Style doesn’t have to be a race to keep up; it can be a way of speaking in your own voice, not the algorithm’s. The goal isn’t to opt out of trends entirely—it’s to stop letting them dictate who belongs and who doesn’t. In slowing down our pace, even a little, we make room for an aesthetic culture that feels less extractive and more honest, one where expression matters more than performance.

WW

Paychecks, Stadiums, and Respect:

Inequity in Women’s Sports

By Jules Zinn-Rowthorn

At the close of the 2025 Women’s National Basketball Association season, one player’s press conference caught the attention of basketball fans and gender equality advocates alike. Napheesa Collier, a star player for the WNBA’s Minnesota Lynx and one of two 2025 WNBA All-Star team captains, spoke to the media on September 30, 2025 regarding her discontent with the league’s accountability and treatment of its players.

Collier detailed a conversation she had with WNBA commissioner Cathy Engelbert, in which she asked Engelbert “how she planned to fix the fact that players like [Caitlin Clark, Angel Reese, and Paige Bueckers], who are clearly driving massive revenue for the league, are making so little for their first four years.” According to Collier, Engelbert responded that “[Clark] should be grateful she makes $16 million off the court, because without the platform that the WNBA gives her, she wouldn’t make anything.” Collier reiterated, “[Us players] go to battle every day to protect a shield that doesn’t value us. The [WNBA] believes it succeeds despite its players, not because of them.”

These comments echo a larger problem in the WNBA, which has seen incredible growth in recent years. According to ESPN, the WNBA is in “its best financial shape since launching in 1997.” In March 2025, shares of the New York Liberty were sold at a “record valuation” of $450 million. Despite increasing enthusiasm for the WNBA, player salaries have yet to reflect the league’s recent growth. As mentioned by Collier, star players earn their money largely from off-court business ventures. Regarding Clark, the top WNBA draft pick

in 2024 and star player of the Indiana Fever, Sportico revealed that 99 percent of her $11.1 million net worth was earned outside of her estimated $100,000 WNBA salary.

Much of the frustration of WNBA players stems from the disparity between their league salaries and those paid to their male counterparts in the NBA. The total cash earned by the top NBA player in 2025 is $59,606,817 (Stephen Curry), whereas the total cash earned by the top WNBA player in 2025 is $269,244 (Kelsey Mitchell), as reported by Spotrac. Indeed, the New York Times estimated that if pay equity between the NBA and WNBA were based on the fraction of “eyeballs per game” and “total attendance” that the WNBA received versus the NBA, “the average [WNBA] salary should be roughly one-quarter to one-third of the average [NBA] salary.” However, the average WNBA salary is about one-eightieth of the average NBA salary.

Currently, the WNBA and the Women’s National Basketball Players Association— the league’s player union—are negotiating a new Collective Bargaining Agreement for the upcoming 202 6 season. The objective of the CBA is to reach the best financial deal for WNBA players, and its terms are renegotiated every four years. This agreement determines the maximum and minimum salaries teams are allowed to pay their players. By January 9, 2026, the WNBPA and WNBA will decide whether players should expect upgraded salaries, adjustments in benefits, league rules, and officiating changes. For players to see meaningful changes next season, it is crucial that the WNBPA gain more support from league officials.

These problems do not only exist at the national level. While the WNBA makes national headlines, this pattern is also evident in the collegiate sphere. In 2021, the National Collegiate Athletic Association voted to allow student-athletes to be compensated for the use of their name, image, and likeness (NIL). This meant that collegiate athletes could profit from their

talent. As of December 1, 2025, of the 100 highest earning college athletes by estimated NIL valuation, LSU basketball star Flau’jae Johnson and UMiami golf commit Kai Trump are the only women.

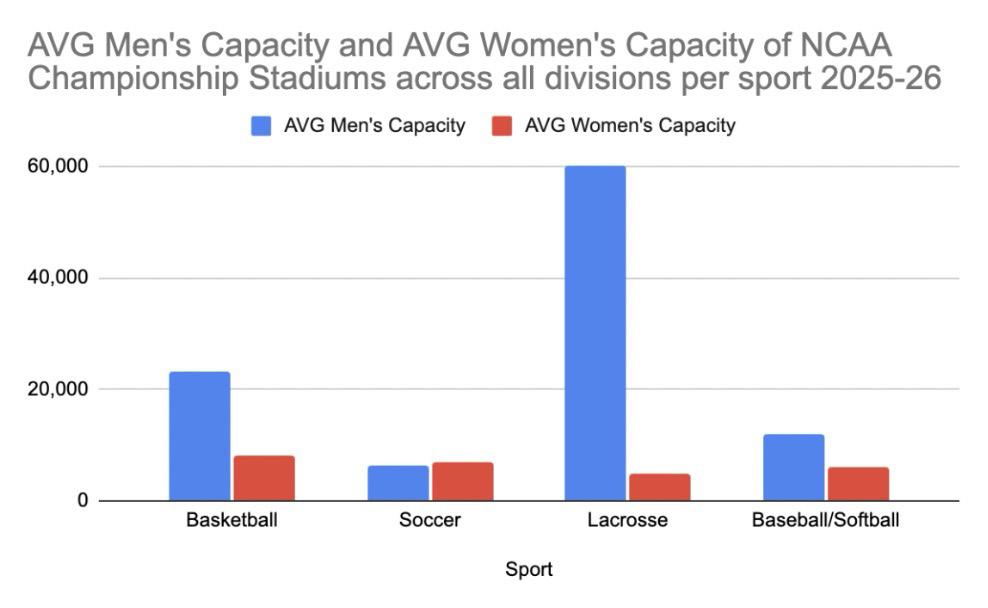

NIL earnings aren’t the only way to measure gender disparity in collegiate sports. Women playing in NCAA championships receive less media coverage and often play in lower-capacity venues than men. In March 2019, ESPN’s SportsCenter spent 2 hours and 13 minutes covering the men’s March Madness basketball tournament, whereas the women’s tournament was covered for 3 minutes and 43 seconds. But the disparities don’t end with screen time.

Elsa Schutt, a senior on the Tufts women’s lacrosse team, spoke to the Tufts Observer about her experience at the 2025 NCAA Division III women’s lacrosse national championship game. Schutt explained that while Division I, II, and III men’s lacrosse championships were held at Gillette Stadium in Foxborough, Massachusetts, only the Division I women’s championship was held at Gillette, while the Division II and III women’s lacrosse championships were held at the Donald J. Kerr Stadium at Roanoke College in Salem, Virginia. While Gillette Stadium has a general capacity of 65,878 seats, Kerr Stadium only has a capacity for 1,400 fans.

Schutt emphasized that although her team was grateful for the opportunity to play in the national championship game, there was a sense of frustration regarding this difference in venue. “We put in the same amount of work to get there,” Schutt expressed. “I think it was really frustrating for all of us because, you know, we put in just as much work as the men’s team.” Schutt continued, “[The men’s team] is really accomplished and they get to the national championship [game] a lot. And for us, we’ve made it a couple times and we’ve never won. So, we have really put the work in.”

“When you’re young and you’re playing lacrosse you look up to [the national championship] as the ultimate feat just to make it there and get to play in a game like that. And the stakes don’t feel as high when you’re playing at a small college in Virginia versus Gillette Stadium where the Patriots play… where Super Bowl champions play.” For Schutt and other seniors on her team, the discrepancies

feel discouraging. “It’s not like we get to redo this year, you know? It definitely feels like we’re just not valued as much.” Players weren’t alone in their concern. Schutt wanted to emphasize her appreciation for the leadership of Courtney Schute, the head coach of Tufts women’s lacrosse. “[Coach Schute] used her voice. She got interviewed after the game, and she really spoke up for us, and no coach has ever done that.”

Schutt’s observations remain relevant for the 2025-26 school year. In 2026, the NCAA men’s lacrosse championships for all three divisions will be held at the University of Virginia’s Scott Stadium, with a capacity of over 60,000. The Division I women’s lacrosse championship will be held at Northwestern University’s Martin Stadium, with a capacity of 12,000. In contrast, the Division II and III women’s championships will be held at the Rochester Institute of Technology, which can accommodate 1,180 people.

Based on NCAA records of 2025-26 division championships, the Observer compared the average capacity of men’s versus women’s championship stadium size across the top team sports of basketball, soccer, baseball and softball, and lacrosse. Men’s basketball, lacrosse, and baseball teams are scheduled to play in larger-capacity stadiums than the women’s teams. Soccer is the only sport where women’s championships will be played in stadiums larger than men’s.

When asked whether this type of inequity between men’s and women’s sports translated to her experience at Tufts, Schutt said, “I don’t think we feel that much of a difference. We’re really lucky as a high-competing team to have a lot of resources. But of course, the men’s team is double our size and so therefore they have more alumni to give money.”

Alexis Mastronardi, the deputy director of athletics at Tufts, said in a written statement to the Observer that “The Department of Athletics is committed to gender equity at Tufts and actively works with the Office of Equal Opportu nity and the university’s Title IX Coordinator to uphold the principles of Title IX, addressing concerns as appropriate and taking steps to promote and foster fairness and equity in the athletics program.” Mastronardi directed those with concerns to file an anonymous complaint through the OEO’s EthicsPoint platform. “We will continue to support efforts that aim to prioritize fairness and equity for student-athletes both at Tufts and across the NCAA.”

Time will tell whether women’s teams will get to play on the same stage as men’s. From professional salary caps to collegiate stadium capacities, women in sports are asking for the same respect and value given to men. For now, the work towards gender equity in sports continues, and the game must go on. Schutt affirmed, “We want to keep the conversation alive.”

The NCAA did not respond to a request for comment on this matter.

I’m Winning This Game of Tug of War

the dirt.

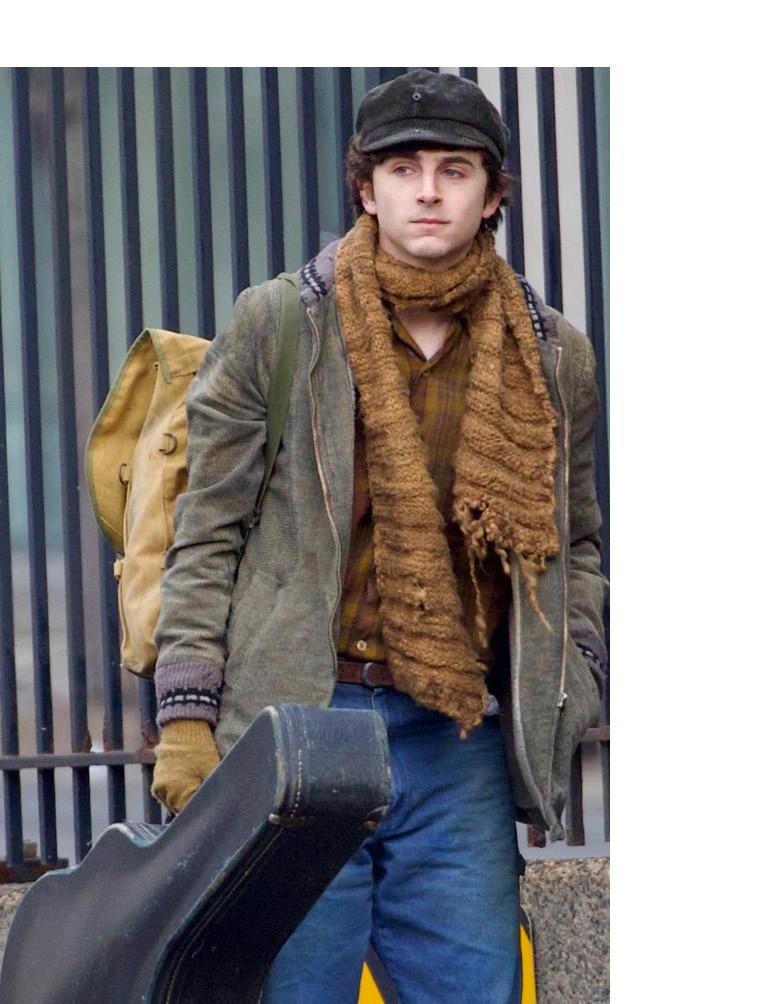

By James Urquhart

How long does it take before the body breaks down?

One of my friend’s aunts has been—for the better part of the last year—facing problems with her kidney. After it finally failed, she was placed on the endless list of people eagerly waiting for a suitable match. Moving up this list takes many years, so to expedite the process, her husband donated one of his to someone else in need. Not too long after, she found a suitable match and underwent kidney transplant surgery. Her problems, like many others before her, did not end there. The new kidney was already beginning to fail. It may have been complications from an inadequate surgery, unpredictable changes in blood antibodies that arose from past transfusions, or just pure misfortune. Her body simply refused to accept exactly what it needed to survive.

This is one of countless examples in which the body’s greatest enemy is itself. Nature’s most beautiful and intricate creation has one tiny problem: cooperation. It seems like sometimes the body has nothing better to do than to tear itself down, to poison itself with defunct cells and strange diseases, eventually becoming weak enough that its only choice is to give up and wither in

Somehow, the thing closest to us is the thing most likely to kill us. Our mortal enemy comes into this world at the time of our birth and leaves after our death, leeching off of our souls until it decides that enough is enough.

It would be typical to write in place of this sentence a thesis that summarizes why it’s okay that the body acts the way it does. Perhaps that sentence and the paragraph that follows it would be littered with scientific explanations about just how hard the body fights to keep us alive, or how one tiny slip up is nothing but an eventuality when looking at the immeasurable complexity of our machinery, so on and so forth. Perhaps that would be encouraging.

Or—let’s be action-oriented. The ideas in the first few paragraphs aren’t meant to be thought-provoking, complex, or nuanced. They’re taken as facts of life, the obvious knowledge that the clock is always ticking. It is one of the cornerstones of what it means to be human, and we’re all aware of this from our first experiences with death to Wour own. OK, we know this. What’s next? I hope I don’t sound terribly French, but the answer is nothing. Sure, we like to stay in shape and eat healthy, but none of these things give us joy for their own

sake. Unless you’re Bryan Johnson, the man willing to spend millions of dollars a year on living as long as possible, you don’t really care about how long you live or a detailed scientific analysis of your body’s health, and that’s a good thing.

At a party, nobody wants to eat the fruitcake over the chocolate. At a bar, everybody actually wants another drink, and some people want a cigarette after the drink and then maybe just one more drink after the cigarette. Not to mention a cigarette on the way home from the bar. At a restaurant, everybody likes food with butter in it and pretends like it’s not the butter that makes it taste good. (I’m sorry to tell you, it’s the butter in the green bean casserole.) It feels good to want these things, and it feels good to enjoy these things. It feels good to poison the body.

With each day spent imbuing my body with countless toxins, it desires more and more to shut itself down. It keeps me aware that acts of war are met with retaliations; throwing up in the bathroom at seven in the morning after a long night out, I swear to remember that next time I won’t have that last drink. I always will. It begins to decompose faster, forcing my hand into treating it well for the next few days until the cycle repeats it-

self again. My process of repair is a minor defeat as much as it is a selfish endeavor. I drink the green juice from Whole Foods that looks the most disgusting not only because it is good for my body, but because I enjoy it. It makes me feel good, and as much as I’d rather be having the Strawberry Pineapple Explosion, I have to drink my horrifyingly delicious kale and ginger liquid fodder. My body is forced to heal, to delay its eventual demise for a little while longer. This tug-of-war is perpetual, save for these brief periods of restoration. Inevitably, I will revert to my passions and my body will continue to rust over. Does my unabashed love for poisonous things come from immaturity? We tend to tell ourselves that eventually we will kick our ‘bad habits’ as we grow up, that we will learn to choose the fruitcake over the chocolate and quit smoking. We accept the fact that our body will always win in the end, begin to wonder if calling a truce is the best course of action, and attempt to work in tandem with it. In that case, I will apologize for forcing it to digest so much crap and it will apologize for all those

terrible mornings spent cold, shivering in my bed.

This agreement is nothing more than a surrender hidden in the subtext of a peace treaty. The body will continue to rot. That is its nature and it cannot be changed. If accepted, I would lose my greatest loves, I would never taste the sweetness of revenge, and I would be forced to conform to the malignant whims of my rival. This would be a sorry state of affairs, and I refuse to concede. If I die, let it be with a large cigar in my mouth and a spoonful of flourless chocolate cake in my hand, and a crossword puzzle on my lap.

Maybe these desires don’t come from places of immaturity, but rather from youthful freedoms that slowly fade away as life goes on. My impulses will shift and perhaps those changes will make me more averse to the mouthwatering desserts and more sincerely keen on the less mouthwatering

desserts. When that happens, please blame my gut microbiome, not me.

Should I hate my body for forcing me to question if I should enjoy the things I enjoy, or if I should be doing the things I do? My body and I are constantly pitted against each other, the only brief ceasefire of our endless war comes while having sex, and if that’s the only thing we both enjoy then so be it—I’d rather it be that than something stupid like swiss chard. Maybe beauty comes out of conflict, and what’s more beautiful than the fact that in spite of my knowledge that all the things I enjoy doing are contributing to the slow decay of my body, I still choose to do them? I am a little kid in an old garden shed playing with defunct landmines. Maybe the landmine blows up, and maybe my body rejects an organ transplant. Only then will it get the bitter taste of victory after a life well spent doing things to spite it.

By Lily Rogers

ORiding theWave: Democrat AmbitionsPost-2025 Elections

Riding theWave: Democrat AmbitionsPost-2025 Elections

n November 4, 2025, over two million voters cast ballots in the New York City mayoral election, the highest turnout since 1989. Te electorate ultimately chose democratic socialist Zohran Mamdani to become the 111th mayor of New York City. Set to take ofce on January 1, 2026, Mamdani will make history as the frst South Asian and the frst Muslim man to hold the position. But New York City was not the only city in the country holding an election, and far from the only place to paint the electoral map blue. Te Democratic Party clinched key victories in New Jersey and Virginia gubernatorial races, Californians passed Proposition 50, and two Georgia Democrats fipped seats on the state’s Public Service Commission, the frst to do so in nearly two decades.

Taken together, the results signal coast-to-coast backlash against the frst year of President Donald Trump’s second term. Tough some have deemed these election results “historic,” anti-presidential backlash in interim and midterm voting is a common refex in American politics. As Political Science Professor Brian Schafner explained, “Voters ofen use [of-cycle elections] as a way of expressing their … frustration towards the current administration, especially when the administration isn’t particularly popular.” A backlash, however, is still just one rejection; a ‘no,’ not an ideological realignment. True realignments—the kind that rewire the nation’s political circuitry for a generation— require more than a single rejection. Tey demand acceptance—a durable, new ‘yes,’ usually in the form of a coalition.

Take, for example, the Democratic waves of 2006 and 2018. Te 2006 midterm election was a referendum on the Iraq War. It delivered a distinct ‘no’ to George

W. Bush’s foreign policy, but did not forge a new, lasting Democratic coalition. Te party’s gains were wiped out in the 2010 Tea Party wave, which returned the House to Republicans by a wide margin.

Te 2018 blue wave was more complicated. It was a ‘no’ to President Trump, but it also activated a durable new component of the Democratic base: collegeeducated suburban voters, particularly women. And this coalition didn’t dissolve afer a single cycle. It helped to deliver unifed Democratic control of Washington in 2020. Tough it may not have been a generational realignment, 2018 demonstrated that a backlash could lay the groundwork for a more lasting shif by attaching the ‘no’ to a specifc, mobilizable demographic group that allowed a momentary refusal to become a multi-cycle alliance.

Te current blue wave carries a tension between distinct visions of power in the Democratic Party: the Democrat of Now versus the Democrat of the Future. Te former plays the board, making use of cold, procedural machinery, and the latter seeks to fip the table with movement energy—the grassroots mobilization of new voters surrounding a transformative ideological vision. Tis divergence means the party must now navigate a shif from opposing a common foe to governing a divided self. As Schafner noted, while it’s “easier for a party to unify against an enemy,” it’s “much harder to … maintain power, because that’s when you see more of these fractures.”

Te Democrat of Now channels backlash into a procedural ‘yes,’ or a realignment secured through cartographic leverage. Te passage of California’s Proposition 50 is a prime example. Te ballot measure allows the state’s independent redistricting commission to redraw district lines

ahead of the 2026 midterms. Once these new lines take efect, the Democratic Party could gain up to fve seats next November by targeting areas with vulnerable Republican incumbents.

Tis strategic preemptive counterstrike is not an anomaly, but an escalation, responding to similar Republicanled redistricting eforts in states such as Texas and Missouri. It makes use of the very map-drawing process that has long been the quiet engine of political power in the US. “We’ve been in the hardball era for a long time,” Political Science Professor Deborah Schildkraut observed, “this is just a new manifestation.” It is an act of electoral chess that answers the GOP’s gerrymandering playbook in kind, signaling a political landscape where future majorities may be secured not only at the ballot box, but in the mapmaking rooms, where lawyers and cartographers vie to secure partisan terrain.

Yet, alongside this backroom calculus, a parallel political evolution has been unfolding in plain sight. Tis proceduralversus-ideological tension is not an abstract debate that exists only in theory, but something lived by students on campuses like Tufs. For freshman Lourdes Ronquillo, a New Jersey native who canvassed for Mikie Sherrill and phone-banked for Mamdani’s campaign, the motivation to get involved with the recent election was a form of resistance: “I see [involvement] as a statement that we are not allowing ourselves to hop on the train of the current administration.” For students like Ronquillo, the party’s internal confict translates into a personal choice: invest time in grassroots action, or accept that power is ofen decided by distant mapmakers. Ronquillo’s choice was clear. Her hands-on work was a

rebuttal to that cynicism. “It demonstrates that our vote actually matters,” she said.

Te Democrat of the Future seeks an ideological ‘yes,’ a realignment built on movement energy. Teir most potent expression to date is the victory of Mamdani, whose campaign ran on a platform of transformative politics that championed housing as a human right and a rent freeze for rent-stabilized units, representing the antithesis of the strategy used in California. Mamdani, a former housing counselor, energized a coalition of young voters and newcomers who won him the Democratic ticket and achieved record mayoral election turnout. In other words, where Proposition 50 sought power through cartography, Mamdani found it through mobilization, demonstrating the energy of progressive, movement-driven politics that operate outside traditional party machinery.

If Proposition 50 is the blueprint of a new Democratic strategy, Mamdani’s victory and subsequent coalition may be evidence of its most powerful ideologi cal core. Tis energy is formidable, but it is also inherently polarizing, creating something easy for opponents to exploit. As Schafner noted, fgures like Mamdani become prime targets, “Maybe [Mam dani] is going to be the newest version of this, where [Republicans are] going to use him as sort of a scare tactic… who you should be scared of.” In this light, Mamdani’s coalition is not just a new base, but also the Democratic Party’s greatest liability—a force that could realign the pri orities of the party or provide the wedge that fractures its budding coalition.

Te 2025 election has delivered a clear verdict but an uncertain future. of the anti-Trump coalition remains a po tent, nationwide force, capable of deliver ing both historic victories and cold, proce dural advantages. But history’s pendulum

warns that backlash begets backlash. Te true test is no longer whether Democrats can mobilize a ‘no,’ but whether they can unite their two competing ‘yes’s’ into a durable whole. Can the party that masters the mapmakers’ rooms also inspire the volunteers making calls in dorm rooms? Te 2026 midterms will answer this, serving not merely as a referendum on the president, but as a stress test for the strategy of the opposition. Te wave has receded,

DESIGN BY RUBY OFFER, ART BY LEILA TOUBIA

Thanks, I Made It Myself!

By Lecia Sun

Last week, as I was shopping, I saw a cute sweater in the storefront window. I thought, “I can make that, so I’m not going to buy it.” As the occasional DIYer, I’ll elect to make something on my own rather than buy from the store. It’s always satisfying to start and complete a project, and when someone asks, I can proudly say: “I made it myself.” Is this desire to show off my DIY abilities pure vanity, or is there more to making do with your scraps?

niture guide. From working on ancient buildings to making DIY sourdough starters in the kitchen during quarantine, the history of human society and growth of civilizations are innately tied with the selfsufficiency DIY promotes.

itself and initiate change. These main principles—chiefly those of freedom of expression, the importance of creative outlets, and the formation of community—held steadfast throughout DIY history.

The idea behind “do-it-yourself” has been around for as long as the tools to do so have existed. Archaeologists discovered remains of a 6th century BCE Greek building with detailed assembly instructions for reproduction—an ancient equivalent to an IKEA do-it-yourself fur-

DIY popularity grew throughout the 1960s and 1970s counterculture movement, as young people called for radical change in identity, family structures, sexuality, and the arts. People during this time challenged capitalism by making their own goods and rejecting the profitoriented values of mainstream America. The 1970s “punk” counterculture movement reshaped the values of nonconformity and individualism championed during the 1960s. Punk grew out of this resistance, calling for individuals to embody a DIY mentality to bypass traditional gatekeepers of the music and art industries. In the article, “Punk Builds a Greener Future,” writer Grace Dougan comments how punk uses “what others throw out—stitching new life into castoffs, scavenging beauty from dumpsters, turning waste into resistance.”

The use of DIY in this countercultural movement expressed rebellious sentiments that worked to challenge societal norms and emphasize freedom of expression. By being scrappy and thinking outside mainstream conventions, the punk movement cultivated the power to express

Consistent with the punk movement’s spirit, many DIYers of the 2000s sought to refurbish or repurpose unwanted items with a continued emphasis on selfsufficiency and sustainability due to growing environmental concerns. With the introduction of the internet, online platforms such as Craftster and Pinterest enabled the DIY movement to reach new heights among millennial and Gen-Z audiences. These sites allowed users to browse, share, and gain inspiration from fellow DIYers, particularly around interior design projects and life hacks.

In the 2010s, DIY continued to grow with further media content and channels such as HGTV Handmade and 5-Minute Crafts. On these platforms, it’s common to see innovative ways to use a rubber band or an old Tupperware container to

Lab. Shriyaa Srihari, a junior mechanical engineering student, relays her appreciation for the resources available on campus for DIYing. “There is a sense of pride when you make things yourself,” she notes. “We made these acrylic phone stands in one of my classes. The other day, I went into Nolop to make another just because I wanted a different color.” She plans on giving the other phone stand as a gift to her mom. “You get to show that you put your time and creativity into something personalized,” she remarked.

make a trendy vase. Viewers see how easy it is to make a small wooden table at home with a couple of wooden rectangular boards and wood glue. The content of this genre prompted viewers to replicate what they saw online because it looked doable. The accessibility of these crafts makes creativity approachable—all it takes to be creative is watching a video and seeing what scraps you have at home.

The DIYers of today find value in both self-sufficiency and in creating for the sake of engaging with the creative process itself. Senior Hannah Jiang, an avid DIYer, couldn’t find a Halloween costume to her liking and found satisfaction in making her own. “I decided to make the costumes myself exactly how I wanted them to look. It was also more fun to just do it myself rather than buy it.” She didn’t have to compromise her vision with what the market had to offer, and through this, she could also assert her creative independence. At Tufts, students have plenty of opportunities to delve into their creative visions at spaces like Craft Center, Nolop Lab, and the Bray

Shriyaa is like many others who opt to gift handmade items rather than storebought. According to Deloitte’s annual holiday retail survey, 41% of Boston respondents are considering homemade gifts instead of buying ones. Handmade gifts can save shoppers money, but when wanting to give their loved ones memorable gifts, there is value over a personalized, handmade DIY gift over a cheaply made store-bought item. With places at Tufts such as the Craft Center that have the necessities to sew, paint, and throw clay, the possibilities for DIYing are endless, both for personal fulfillment and that of others.

Another junior, Sydney Barr, shared her recent DIY experience in making her own decorations for her offcampus house. “My housemates and I saw that the decor was so expensive, and we thought, we can make this ourselves.” She used supplies from the Craft Center and Nolop to make paper chains, paper stars, snowflakes, and origami tassels to hang in her living room. “We made everything in one night. It was an amazing moment to bond with others and reconnect with our inner child.” Not

only is crafting a way to make something beautiful or useful, it also fosters community and friendships.

Through the art of creating something tangible, DIY is a way to champion individuality and expression in a world of convenience and conformity. The words “I did it myself” imply the hours you spent hunched over the sewing machine, playing around with the best way to thrift-flip old skinny jeans into a miniskirt. The act of DIYing is a bold declaration of both your creative independence and nods to the larger community of DIYers and those who DIYed before us.

DESIGN BY AHMED FOUAD, ART BY RUBY MARLOW

Caught between Yay and Nay The Art of Refusal

By Ishaan Rajiv Rajabali

ing of traffic is carried through the sharpness of the pani (or that may be your ears ringing from the spice). And yet, the puri retains its satisfying crunch. It’s all about the balance.

My refusal to assimilate to a more relaxed tread, to instead haphazardly dart through a slow-moving crowd, is integral to my cultural identity. It’s like my innate tendency to say achchha, a Hindi word meaning “good” but really ambiguously employed for anything. Got an A on your test? Achchha (accompanied by a beatific smile). Hesitantly tried some new food, only to find out that you like it? Achchha (wide-eyed). Woke up to find a meteor hurtling toward your immediate vicinity? Achchha and some pensive chin-stroking as you muse on the next course of action (cowering in fear). Despite its passive nature, the word gives me an enigmatic agency; it is up to the speaker to take away its hidden meaning.

Sometimes we choose to embrace our refusals. With midterms on my mind a couple of weeks ago, I stayed up and turned to a shuffle of songs I continue to catalogue for sleepless nights. One of my old favorites, a 1970s Hindi classic about a woman waiting for her lover to come to her, moved me for the first time to stop suspending my disbelief and wonder why she didn’t dump him. She laments that her beau has forgotten his promise and wonders if some mistress of his has waylaid him. Call it an early spin on “S(he) be(lie)ve(d).”

than love: academic validation. Sleeplessness won’t help the singer or me; tell that to our amygdalas. Only we can personally situate our concerns on the spectrum between stubbornness and reason. Until then, we stay up.

Refusal and rebellion; these philosophies are part and parcel of growing up. My preteen years kicked off with ringsmuggling hobbits and culminated in defiant runaway science experiments. From Katniss Everdeen’s subversive whistles in The Hunger Games to Winston Smith’s crimes of independent thought in 1984,

depending on your interpretation (I will offer no further spoilers). The challenge of the maze is to confront whether we control our denial, or it, us.

Refusal can be the key to answering confounding mysteries, such as in Olga Tokarczuk’s Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead. Seen through the eyes of Janina Duzsejko, an aging astrology and poetry enthusiast, the novel takes place amidst a series of murders in a village along the Polish-Czech border in Silesia. As it begins to emerge that the victims all share a bloody passion for hunting, Janina warns the skeptical community and her readers about nature’s anthropomorphic force that seeks retribution from those who commit violence against it. It is her persistent belief in this theory that leads us to the thrilling reveal. Janina’s stubbornness powers the narrative; reason waylays the reader from the truth.

my teenage years were (literally) bookended by literary figures resisting authority with varying degrees of success. Even the irritating angst of my least favorite protagonist, Holden Caulfield, embodies a rejection of the superficial atmosphere he feels caged by.

For decades, the Indians have been romanticizing situationships through songs about sleepless nights when all a deluded singer really needs is a copy of He’s Just Not That Into You. But these simultaneously innocent and self-aware lyrics do resonate somewhere, as she describes how slumber evades her. Suddenly, you’re waiting there with her, keeping the company of camphor lamps and an endless night, but only once you eschew your cynicism. How else can you appreciate her melancholia? I, too, have spent many a night worrying, in my opinion, about something more precious

Refusal is hidden around the corners of mazes, as we navigate choices at every turn and face the consequences at the end. Maybe it’s like Pan’s Labyrinth in the eponymous film (El laberinto del fauno), in your personal transposition of Guillermo Del Toro’s creation. Our heroine, Ofelia, deals with fairy-folk, giant frogs, and the gluttonous “Pale Man,” whose malevolence manifests in his disembodied pupils and child-eating tendencies. The madness of this fantastical maze parallels her reality in a village in Francoist Spain, where her stepfather, a guerrilla-hunting captain, commands his reign of terror. Her resistance to spill the blood of an innocent to complete her quest is both salvation and undoing,

I’d like to see refusal as the erratic citizens of Lewis Caroll’s Wonderland (or rather, Disney’s adaptation of it) do, as holding the promise of adventure and whimsy. As much as we think our “no’s” are marked by reason, they often aren’t. Taking one path leads you to a game of croquet with the Red Queen—further, if you refuse to concede to her strange rules, hang onto your hats (and heads), people! Maybe you can’t resist the cake labelled “eat me,” or the vial labelled “drink me,” a see-saw of transmogrification. As for me, I hope to find the perpetual tea party; I think I’d like to listen to the Mad Hatter and March Hare’s ruminations on the logic of refusal. They’d surely be less formidable than a snackwielding aunty.

…

“No, no, you must eat something,” my worthy opponent strikes. “Really, I couldn’t,” I parry. “Come on, at least one piece!” My shield is wearing down, and my stomach is grumbling. “Ok fine, I’ll have one.” A truce has been reached, until it turns out that it’s an armistice, when the next snack is brought out.

The Algebra of Rejecting

By Emilia Ferreira

Ivividly recall a friendship from years ago that ended in me cutting up a pair of shoes they had lent me. While certainly immature, I—for once in this fraught relationship—felt like I had finally said “no.” It was a rash decision, but the black heels, snipped in just the places that made wearing them impossible, embodied my refusal to forgive this latest transgression. It ended the cycle of half-baked apologies and forgiveness given only out of obligation. It was a final declaration that not only do I not accept your apology, but you will feel it as I pass my limit.

An apology, and its subsequent forgiveness, is at best a careful calculation. It is the weighing of your own self-respect against the value you attach to maintaining this relationship. You must consider the perceived integrity of the apology (Will they mess up again? How intentional were their actions?) and the damage done (How deeply did the situation affect the relationship? Affect you?), and assign to each a value to consider in the equation. But making a decision that holds so much weight is rarely that simple,

and so two pivotal variables come into play to make the algebra of rejection. The shoes caught in the crossfire of my own weighing of whether to forgive or not to forgive embody the passion tied to the calculation: the x variable, or the emotional attachment to this relationship or this person. The emotional tie you feel might be the tipping point, but it can’t dictate the equation alone.

Even given a textbook apology, there could still be that nagging feeling that the apology isn’t enough. It’s important that in your calculus, you factor in that feeling, no matter how by-the-book the apology is. Think of that knot in your stomach, the hesitation you feel, the anger, the simmering uncertainty, as the y variable. The issue with the x variable (the connection you share) and the y variable (the gnawing feeling) is that they are dependent on one another. Even once the other numbers in the calculus— weighing the apology’s quality and the damage done—have been squared away until they have been resolved, the x and the y variables still exist, even if abstractly. What may dictate the final push towards turning down an apology is a recognition that the y variable is meaningful and unable to be ignored,

even in the face of a strong x variable. One variable can outweigh the other, but can never negate it entirely.

Because of this, refusal to forgive is tough—not in the sense that it is unfeeling or unemotional, but that it is firm. There’s a certain amount of grit needed to turn away without looking back; or to use another term, self-respect. In her essay “On Self Respect,” Joan Didion calls it “knowing the price of things.” But to come to the right conclusion, Didion points to the need for character by saying, “character— the willingness to accept responsibility for one’s own life—is the source from which self respect springs.”

When it comes to refusing to forgive, there will always be a price: the relationship, the person you lose. If the x variable in the calculus represents the tie you have to this person that may be difficult to give up, Didion accepts it, and raises a challenge: accept that there may be turbulence when refusing to forgive, but do not back down to it. Accept that you may not know for some time if refusing to make amends was the right choice, and stand by your choice even in the face of uncertainty while the dust settles.

To be human is to live with the doubt of making the right or wrong choice, but to have self-respect is to accept that doubt, assume the risk, and still march on forward. If you choose to forgive, you have to accept the possibility that by inviting this person back, wrongdoings now forgiven, they may betray your trust again. To have

There’s a certain amount of grit needed to turn away without looking back; or to use anoth er term, selfrespect.

self-respect, it is important that you don’t flail about if that betrayal happens again, having known that was a possibility when giving out another chance. There are some cases where an apology, no matter how grand or genuine, cannot bring back what was lost. The damage done outweighs everything else; the gnawing feeling outweighs the attachment. A strong connection to someone else is a rare thing, but not singular. Of course, there will be doubt when refusing to accept an apology, especially from someone important to you, but the doubt exists for a reason. Malicious and purposeful or not, repeated transgressions (or one big one) can weigh on the relationship. The apology in question may be one of many; if it is, are we obligated to consider all the previous apologies, even if we have accepted them in the past? There’s no magic number. It’s that y variable feeling: if I accept this new apology, can I face myself again?

Swallowing your doubts about an apology for the sake of the relationship will grate away at the soul. To be truly mature is to know when to move on. It takes courage to rip off the Band-Aid and refuse to make amends. The mature thing to do when confronted with a lackluster apology is not to create a false harmony by accepting—if anything, it’s deceitful to the other person as well

as yourself—but to know when to walk away. That is not to say that we should be solitary; a life well lived is in the company of others. But, we owe to ourselves a certain amount of self-respect to not ignore the doubt over cutting ties if it could be, in the end, a path to a new you.

Harmony is a virtue that, while aspirational, cannot always be the end result. Not every relationship can be kept neat and tidy, with perfect apologies and perfect growth. Refusal to forgive is not a throwing up of the hands in defeat, as it can often be read, but a new chapter in the infinite search of selfhood. That sense of self is furthered by the develgopment of self-respect and the acceptance of messy ends and painful losses. Refusing to forgive is standing up for yourself, whereas infinite appeasement to others results in a sense of self that caters to others instead of the body you live in.

When refusing to forgive, you walk away from something you’ve built, something turned sour. Or perhaps, through the actions that they now have to seek forgiveness for, they walked away first. The refusal to make amends is not an instant gratification situation; the path forward is choppy and wayward. Grief comes relentlessly, but somewhere between mourning them and finding yourself, you forget to miss that dream house you built together. That x variable, the strength and authenticity of the attachment, starts to become smaller and more insignificant until it is fully invisible in the face of time. You can carry with you the courage of past mistakes, you can know the price of things. You can decide that the price is too great, that you are worth much more.

LUDDITES UNITE:

Disconnecting to Connect

By Gigi Appelbaum

To find myself at a dining hall in which nobody pulls out their phone is almost unheard of. If I’m hanging out with friends, it’s almost guaranteed that our phones are by our sides, poised to be picked up at a whim. A constant flurry of notifications fight for our attention, and, most of the time, they win. I can’t count the number of times that I’ve deleted social media just to redownload it months later, with no explanation other than a vague promise that I’ll have a better relationship with it this time. There’s no question that smartphones are addictive, and like any addiction, breaking away takes considerable effort and willpower.

Most smartphone users will admit to some level of addiction to their device. Phone addiction is so prevalent that Oxford University Press’ 2024 Word of the Year was “brain rot.” My peers complain of overstimulation, anxiety, and an inability to pull themselves away from the allure of their technology. But despite this acknowledgement of harm, it’s a novelty to find someone willing to take the leap to remedy their frustration.

In 2022, The New York Times profiled 17-year-old Logan Lane, who took matters into her own hands when she put her smartphone in a drawer, bought a flip phone, and didn’t look back. Committed to transforming her life by rewiring her relationship with technology, she branded herself a Luddite, founded a Luddite Club at her high school, and invited peers to weekly screen-free meetings promoting creativity.

A historically derogatory term referring to someone opposed to new technology, the term ‘luddite’ stems from a 19thcentury movement of the same name in which English textile workers led raids to destroy new automated machinery that they found to be problematic. The Luddite Club gave the word new significance, allowing it to represent a new way of life centered around a rejection of modern smartphones and a commitment to embracing the realities and complexities of the world without the crutch of a phone in one’s pocket.

In a follow-up, the New York Times reported that some club members, upon leaving for college, struggled to navigate the new demands of college life without a smartphone. Evidently, it’s hard not to question whether a life without smartphones is fully possible in a college setting, where phone ownership is presumed and even necessitated.

At Tufts, one of the first tasks asked of students is to download the Duo Mobile app, used for two-factor authentication when logging into essential services like Canvas and SIS. On-campus dining locations like Pax et Lox and Hodgdon require an app to place orders. At the club fair, students scan QR codes leading to online Google Forms and Slack channels for communication. College infrastructure relies on smartphones— is it possible to function without one?