I. Executive Summary

Background

Conducting a Community Health Needs Assessments (CHNAs) once every three years became a Federal requirement of not-for-profit hospitals when the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act became law in 2010. Northern Cochise Community Hospital (NCCH) and Benson Hospital (Benson) along with other parties including Cochise Health and Social Services, Copper Queen Community Hospital and the Legacy Foundation of Southeast Arizona last conducted a joint Countywide CHNA in 2016. Using the infrastructure created through the Healthy Cochise Initiative, the 2016 CHNA’s five-month process was robust and ultimately engaged more than 2,400 County residents through a community needs survey, community meetings and stakeholder engagement. The process utilized a modified Mobilizing through Planning and Partnership (MAPP) framework.

Consistent with federal requirements, both NCCH and Benson adopted the CHNA as their own in 2017, and each independently developed its own Implementation Plans. These Plans were also adopted in 2017.

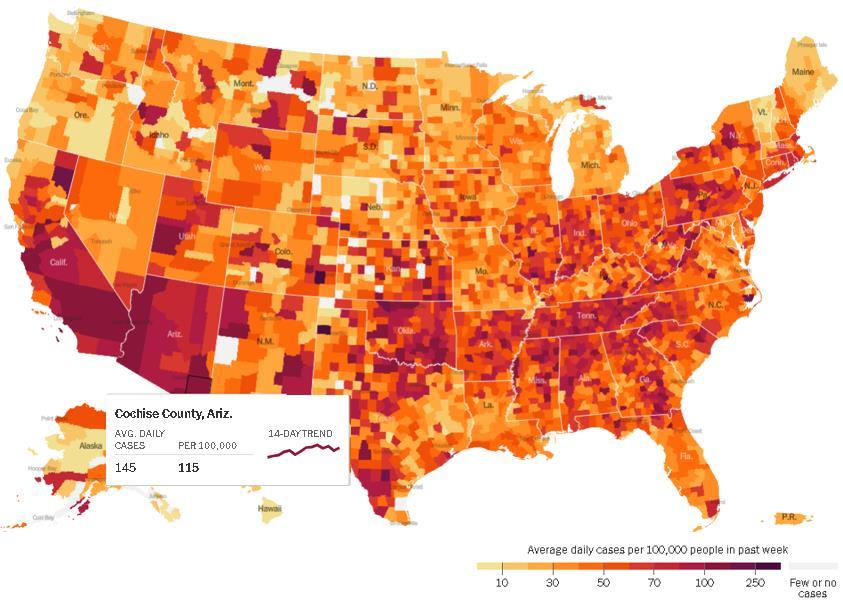

Source: New York Times 2020

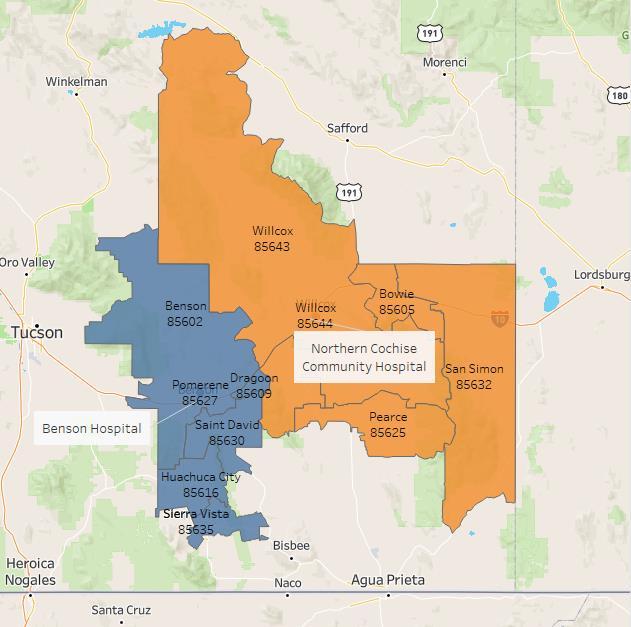

Because the process made possible by the Healthy Cochise Initiative infrastructure was not replicated in 2019-2020, NCCH and Benson elected to move forward with a joint CHNA that assesses the contiguous communities they serve. This CHNA process was commencing as the COVID 19 pandemic was worsening in our communities, and it was being finalized for adoption as vaccine distribution plans were being prepared and implemented: resulting in a slight delay in Board approvals. As the Map 1 depicts, Arizona in general, but Cochise County in particular (the Service Area for the joint CHNA) has some of the highest COVID rates in the Nation.

This 2021-2023 CHNA is comprehensive and builds off the 2016 effort. Consistent with IRS requirements, each hospital will separately adopt the joint CHNA and then develop its own Implementation Plan.

Map 1: COVID Hot Spots

Our Hospitals

Northern Cochise Community Hospital NCCH’s mission is to provide for the healthcare needs of the greater Willcox community and surrounding communities in Southeast Arizona.

NCCH is rich in history and culture, contributing significantly to the progress and direction of medicine in Arizona. More than ever NCCH is committed to continuing the great tradition of providing quality healthcare close to home.

The Municipal Hospital was the first hospital in Willcox, built in 1952 with 12 patient beds. As the facilities at the Municipal Hospital became outdated, and it was becoming increasingly difficult to provide needed care for patients, NCCH was established in 1968 to provide updated and more modern hospital services and facilities.

The hospital opened with 25 beds and was one of only 23 hospitals in the State of Arizona, not including hospitals owned by the mines. NCCH ultimately served as a model for the development of other Arizona community hospitals. NCCH also carries the distinction of being the first hospital in the State to grant privileges to Doctor of Osteopathic Medicine (DO), creating a culture and environment that, to this day, has DOs and MDs working side by side in the hospital setting, to the direct benefit of patients served.

A nursing home was opened in 1972, four years after the hospital opened its doors. Unfortunately, due to high costs and dwindling reimbursements, the nursing home, was closed in 2016.

NCCH is a federally designated Critical Access Hospital (CAH) meaning that the federal government has designated it as an essential community provider and reimburses based on allowable costs NCCH operates a Level IV trauma Emergency Department and also offers a range of primary and preventive health care services including senior services, a pharmacy and rehabilitation services In addition to the Hospital, NCCH operates both Rural Health Clinics and specialty clinics

Northern Cochise Community Hospital

Our Mission: We are here to ensure the people of Willcox and the communities we serve have access to exceptional patient care that is close to where they live.

Our Vision: To be your choice for healthcare resulting in healthier communities for the people in our district and beyond.

Our Values: We care about the people we serve and will attend to their individual needs in a timely manner. We will work together to keep and maintain the health, comfort, and safety of the communities we serve.

Compassion

Integrity

Community

Trust

Benson Hospital

Benson Hospital has been serving the San Pedro Valley community since 1970. The original hospital was privately owned and was located where the current public library is today. In 1963 the San Pedro Valley Hospital District was formed, and in April of 1966, plans began to build a new hospital at the present location. The new hospital opened in early July 1970.

Today, Benson is a 22 bed CAH. It serves the entirety of the San Pedro Valley Hospital District region, the surrounding communities of southeast Arizona and the influx of winter visitors each year to the community.

Our Mission: Our mission is to provide exceptional health care with compassion.

Our Vision: We aspire to serve our community by being the best health system as measured by the quality of the care we deliver, the experiences we create and the value we bring.

Our Values:

Compassion

▪ We have heart

▪ We respect diversity and individuality

▪ We honor body, mind, and spirit Dedication

▪ We work hard for our patients and each other

▪ We are committed to professionalism and excellence

▪ We listen, we learn, we grow Community

▪ We are welcoming and friendly

▪ We practice kindness in all our relationships

▪ We reach out as teachers and as leaders Integrity

▪ We tell the truth

▪ We are responsible in how we use our resources

▪ We have the courage to uphold our values

Along with inpatient and skilled nursing care, the hospital operates a number of outpatient services including infusion therapy, wound care treatment, mammography, and rehabilitation. Benson also operates two primary care/specialty clinics and a retail care clinic embedded in a local supermarket.

The Hospital provides Level IV Trauma Emergency services staffed with physicians 24/7. The Level IV Emergency Department is the gateway for most admissions to the hospital or, when necessary, a transfer to another area hospital. Benson is one of only 13 Level IV Trauma designated emergency departments in the State.

Benson Hospital

2020 Community Health Needs Assessment Process

What is a Community Health Needs Assessment?

A Community Health Needs Assessment (CHNA) is a process designed to better understand the health needs of the local community and to provide direction to community organizations public health, healthcare, and social services regarding identifying gaps and adopting demonstrated best practices to close them.

Per Federal regulation, the CHNA process must include input from community members, organizations, and health care providers.

For our CHNA, data from a number of federal and State level sources were used to better understand the demographics, health behaviors, social & economic factors, physical environment, and clinical care characteristics of the two hospital services areas and the County Specific data sources included:

▪ Centers for Disease Control, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Survey

▪ American Community Survey (ACS), US Census Bureau

▪ Robert Wood Johnson County Health Rankings

▪ Department of Health and Human Services National Vital Statistics

▪ Arizona Youth Survey

▪ UDS Mapper HRSA Data Warehouse

▪ Arizona Department of Health Primary Care Statistical Area Profiles

▪ Arizona Department of Economic Security Point in Time Homeless Survey

When possible, data was analyzed at the individual hospital Service Area level, and if not, data from the Arizona Department of Health Service’s Primary Care Statistical Areas (PCSA) was used as a very close proxy (the Sierra Vista and Benson PCSAs most closely resemble the Benson Hospital Service Area and the Willcox and Bowie PCSA align with the NCCH Service Area). Where Service Area or PCSA data were not available, it is reported at the County level.

NCCH and Benson had planned to additionally undertake a robust in-person community convening process to assess, identify, and prioritize community needs. After much discussion, this year, due to COVID, we chose to use a combination of online surveys and one-on-one phone interviews with Service Area and County community members and organizations serving the vulnerable.

II. 2017 Community Health Needs Assessment and Accomplishments

The 2017 Countywide CHNA culminated with a Community Health Improvement Plan (CHIP) that adopted the following priorities:

1. Mental Health and Alcohol/Substance Abuse: Medicaid utilization data revealed that mental health and substance use disorders are a major contributor to the poor health of Cochise County residents. Mental health and physical health are inextricably linked, and research has shown a link between depression and chronic diseases and health conditions, including diabetes and cancer, which are two of the leading causes of death in Cochise County.

2. Good Jobs and a Healthy Economy: Health is influenced by a number of factors including social and economic and where people live. People who live in rural areas are at a higher risk of poor health. Cochise County is one of two counties in Arizona with a declining census; all other counties are experiencing population growth. In addition, approximately 28 percent of the County’s children are living in poverty, which is an indicator for increased mortality, increased prevalence of medical conditions and disease incidence, and poor health behaviors.

3. Healthy Eating, Obesity and Diabetes: Unhealthful individual behaviors like smoking, lack of physical activity, and poor eating habits are major contributors to the leading chronic diseases. The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) catalogs communities with limited access to healthy food by determining what percentage of low-income residents live close to a grocery store (within 10 miles in rural areas). The lack of healthy food choices, lack of physical activity and obesity all contribute to the County’s high rate of diabetes.

Starting with these priorities, both NCCH and Benson, after considering their resources, and the availability of other organizations within their specific Service Area or Countywide to lead an initiative, developed their own Implementation Plans focused on improving the health of their respective Service Areas. The Implementation Plan for each, along with accomplishments to date is below:

Northern Cochise Community Hospital, 2017 Implementation Plan and Accomplishments

Prioritized Need Objectives

Aging Concerns

Substance Abuse/Misuse

▪ Provide education and support services on aging for seniors, greater healthcare options, and opportunities and resources for living well.

Accomplishments

▪ Sponsored, housed, and helped manage the Rose C. Allan Senior Learning Center, where area seniors have a place to socialize, attend presentations on health, and join classes. Classes have moved to virtual during the COVID-19 Pandemic, including chair exercise classes and BINGO.

▪ NCCH Certified Diabetes Educator provided free presentations at the senior center quarterly, including diabetes and healthy living and eating.

▪ Advertised NCCH specialty clinics in the local newspaper to encourage local utilization.

▪ Published articles weekly about health issues including depression, weight loss, prostate cancer, COPD, Alzheimer’s and much more.

▪ Provide education and best practices to assist in decreasing opioid misuse and abuse in Southeast Arizona.

▪ Build relationships with Mental Health Providers to increase coordinated care for Southeast Arizona residents.

▪ Provided training to NCCH medical providers re: reducing unnecessary opioid prescribing.

▪ Southern Arizona Opioid Consortium (created through a federal grant) provided naloxone training and informational meetings on opioid misuse to schools, the public, and workplaces

▪ Partnered with Willcox Against Substance Abuse, and Sonoran Prevention Works and provided trainings for naloxone use for opioid overdose and on opioid misuse in schools throughout the County for teachers and students, public safety workers and the public. Trainings were in Spanish and English.

▪ Worked with Cochise Addiction Recovery Partnership to increase numbers of addicted people who turn themselves and their drugs into police in exchange for treatment instead of arrest.

▪ In partnership with SAOC updated opioid treatment cards every year. The card includes Cochise, Graham and Pima counties. Provided cards to schools, workplaces, fire departments, police, EMS, etc. throughout Cochise County.

▪ Worked directly with Community Bridges Treatment Facility to address behavioral health needs.

Diabetes and Obesity, including Healthy Eating

▪ Provide education and care that is safe, timely, effective, efficient, equitable, and patient-focused.

▪ Hosted quarterly free presentations including breakfast at the senior center on diabetes health and wellness.

▪ Published diabetes and other health-related articles weekly in the local newspaper.

▪ Held the annual NCCH 5k trail run/walk in 2019 with 54 participants and in 2020 with 31 participants.

▪ Implemented Steps Forward to Healthy Living Class in 2020. Has moved to virtual classes due to COVID-19.

▪ Held health fairs in 2017, 2018, and 2019. Several healthy eating vendors joined us in 2019.

▪ Donated turkeys for Thanksgiving to the Willcox food pantry in 2017-2019.

Benson Hospital, 2017 Implementation Plan and Accomplishments

Prioritized need Objectives Accomplishments

Good Jobs and Healthy Economy Future State

▪ Maintain the hospital's financial position to ensure its continued role as a leading employer in the community.

▪ Continue collaborations with businesses, schools, and elected officials to grow the local economy.

▪ Expanded services and hired new staff. This adds to the direct job impact of Benson hospital in the community as well as adding to the indirect economic impact.

▪ Hired a dedicated community development specialist to work with community partners. This includes working with the Chamber of Commerce, elected officials and the schools to help address economic growth from a collective impact position.

Prioritized need Objectives

Mental Health and Alcohol/Substance Abuse

▪ Support substance use education in the schools.

▪ Collaborate with community addiction and treatment services.

▪ Provide mental health training to hospital and community partner staff.

Accomplishments

▪ Formed a collaboration with Concert Health to implement the collaborative care model in our Rural Health Clinics. To date 85% of patients with behavioral health issues have experienced a significant reduction of symptoms

▪ Actively partnering with the Cochise Addiction Recovery Partnership to work with community law enforcement to identify non-punitive ways to address the opioid crisis.

▪ Partnered with CleanSlate Treatment Center. Meetings have been delayed due to Covid-19 but will start-up again in 2021.

▪ Mental health trainings by NAMI for hospital and community partner staff are planned and will be implemented when Covid-19 permits

Healthy Eating, Obesity and Diabetes

▪ Collaborate with community partners to design a path focused on obesity and diabetes prevention, selfcare, and wellness.

▪ Work with community partners to provide for the nutritional needs of elderly patients.

▪ Connect patients to nutritional specialists and resources in the community.

▪ Planned the return of Produce on Wheels Without Waste to Benson. This program brings in over 10,000 pounds of affordable fresh produce a month for people in the community. In 2020 the hospital took over as the anchoring sponsor for the event.

▪ Helped sponsor and continue to support food pantries located in the local schools.

▪ Collaborated with the Benson Food Pantry to ensure discharging patients have access to healthy food.

▪ Arranged for a podiatrist to hold office hours in town to provider diabetic foot care.

▪ Expanded telehealth program to bring new services to the community including endocrinologists, nutritional counseling and Tucson Bariatric.

III. Our Communities

Cochise County

Founded in 1881, 31 years before Arizona achieved Statehood, Cochise County has a rich and diverse history. Located in the southeast corner of Arizona and covering nearly four million acres, it is larger than the States of Connecticut and Rhode Island combined. The County’s namesake, the legendary Apache Chief Cochise, waged battle with U.S. Cavalry units in the Dragoon mountains, while Geronimo was pursued deep into the Chiricahua Mountains.

Today, people of diverse cultures, with varying socioeconomic and health status conditions call Cochise County home. The communities comprising the County including Tombstone, the copper town turned artistic community of Bisbee, Sierra Vista, Fort Huachuca, the vineyards, and farms of Willcox, the natural beauty of the San Pedro Valley and the cross-border bustle in Douglas each serve to create a diverse lifestyle and geography as well.

Cochise County’s population is nearly 127,000 today. It has declined by nearly 4% between 2010 and 2020. Growth by 2025 is expected to be virtually flat (+1%). Collectively, the Service Areas of NCCH and Benson cover about 80% of the land area of Cochise County, and the populations of the two combined Service Areas represent about 53% of the County’s population.

Each hospital’s Service Area was determined based on actual patient origin data and are reflected in Map 2.

Map 2: NCCH and Benson Service Area Map

The NCCH Service Area (referred to as Northern Cochise) includes six zip codes. These zip codes represent the area from which 85% of NCCH’s hospital’s patients reside, and include:

85643 Willcox

85625 Pearce

85644 Willcox 85606 Cochise

85605 Bowie

85632 San Simon

The Benson Hospital Service Area (referred to as Benson) also includes six zip codes. 83% of Benson’s patients reside in these six zip codes:

85602 Benson

85630 Saint David 85616 Huachuca City 85635 Sierra Vista 85627 Pomerene 85609 Dragoon

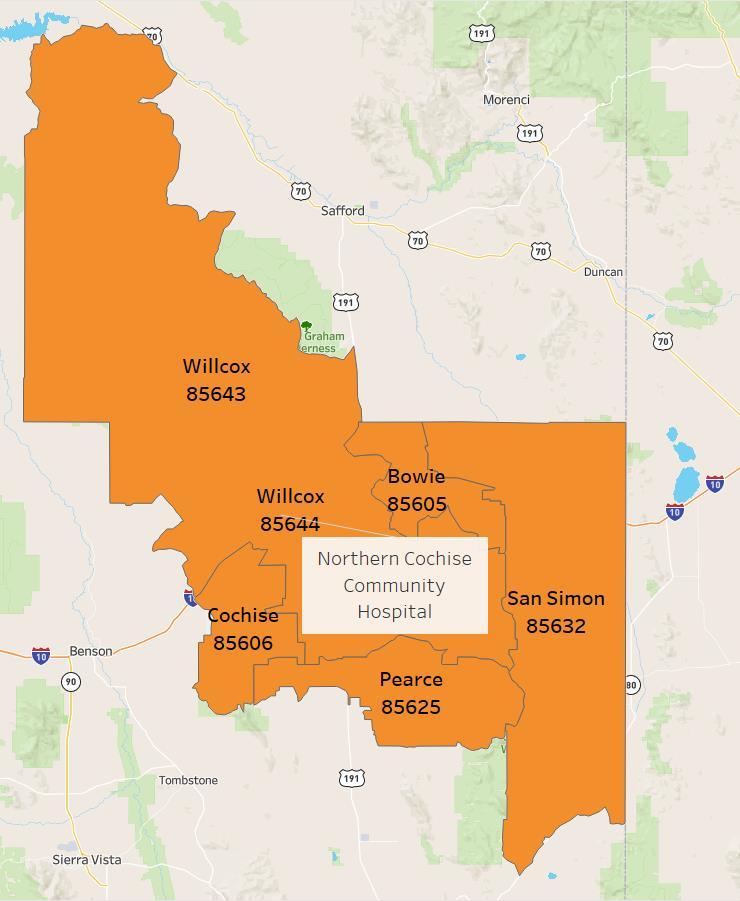

Northern Cochise Service Area and Demographics

Map 3 shows the NCCH Service Area. As shown in Table 1, the population of the Northern Cochise Service Area is nearly 13,700. The Service Area’s population declined by about 6% between 2010 and 2020 and is expected to remain relatively flat between 2020 and 2025. Of interest is the fact that the population age 0-64 actually declined by 14.4% between 2010 and 2020 while the 65+ grew by nearly 30% over the same time frame. The same pattern is expected between 2020 and 2025: the under 64 will contract by another 2.5% while the 65+ is expected to grow by almost 10%. Today, nearly 27% of the population is over the age of 65, and by 2025, this percentage will grow to 29%.

Comparatively, in 2020, 23% of the County’s population is age 65+, while only 18% of the State’s population is age 65+.

American Indians represent about 1.4% of the total population while Hispanics represent about 42%. The Hispanic population is expected to grow nearly 4% by 2025 while the American Indian population is expected to remain relatively flat.

Map 3: NCCH Service Area

Table 1

North Cochise Community Hospital Service Area Population, 2010-2025

Source: Nielsen Claritas

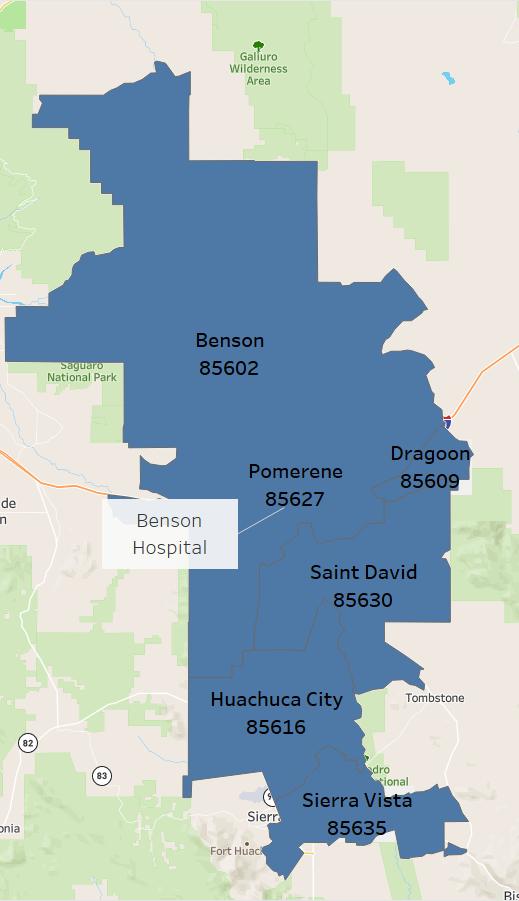

Benson Service Area and Demographics

Map 4: Benson Service Area

Map 4 shows the Benson Service Area As shown in Table 2, the 2020 population of the Benson Service Area is nearly 53,300. The Service Area’s population declined by nearly 2.5% between 2010 and 2020 but is expected to grow almost 2% between 2020 and 2025. As with the NCCH Service Area, the population age 0-64 declined, by almost 9% between 2010 and 2020, while the 65+ grew by 26% over the same time frame. By 2025, the 0-64 population will be virtually flat, while the 65+ is expected to grow by about 8%, which is slightly less than County’s rate (+10%). Today, 24% of the population is over the age of 65, and by 2025, this percentage will be 25%.

American Indians represent slightly less than 1.5% of the total population while Hispanics represent nearly 26%. The Hispanic population is expected to grow by about 14% by 2025 and the American Indian population is also expected to grow slightly.

Source: Nielsen Claritas

Benson Hospital Service Area Population, 2010-2025

IV. Community Health Needs Assessment Methodology

This joint CHNA included both primary and secondary data collection. In addition, the two hospitals closely reviewed the focus and priorities developed by several health and social service organizations in Cochise County that undertook robust visioning and planning for improved health in the County within the past year or so. Generally, the identified unmet needs/gaps identified by these entities across the board supported the priorities of each Hospital’s 2017 CHNA and included the following identified needs:

▪ More mental/behavioral health services

▪ Better access to transportation to health and social services

▪ Better access to healthier foods

▪ Improved information and referral to health and social services

▪ Improved access to primary care

▪ Improved local access to specialty services

▪ Economic development

▪ Wellness

Benson Willcox Sierra Vista

Good Jobs, Healthy Economy Aging Problems Good Jobs/Healthy Economy

Drug Abuse Mental Health Substance Abuse

Mental Health Healthy Foods Mental Health

NCCH and Benson also evaluated the communityspecific priorities identified through the community engagement process for the 2017 CHNA focusing specifically on priorities identified by communities that fall within the Northern Cochise and Benson Service Area boundaries. As can be discerned in Table 3, the individual communities helped focus both 2017 Implementation Plans.

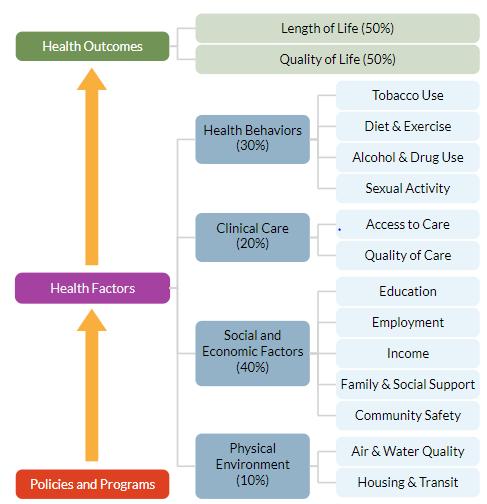

To guide the data collection efforts for this CHNA, NCCH and Benson used the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s (RWJF) model of community health. This model emphasizes the many factors that influence how long and how well a community lives by using more than 30 measures that help communities understand how healthy their residents are today (health outcomes) and what will impact their health in the future (health factors). One real value of the RWJF model is that it demonstrates the role of factors beyond clinical care that affect the health of a community and its residents.

As identified in Figure 4, clinical care represents only 20% of the factors influencing health outcomes, while social and economic factors and health behaviors account for 40% and 30% respectively.

Table 3: 2017 CHNA Service Area Priorities

The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute jointly publish an annual report of health data for every County in the United States, called ‘County Health Rankings’. Data from County Health Rankings was used throughout this CHNA.

The data in Table 4 track Cochise County’s progress on the RWJF metrics when ranked in comparison to the other 14 counties in Arizona. While the County shows slight improvement overtime related to health outcomes, it still ranks lower (8th out of 14) for this overall metric than it does for the ‘health factors’ metric (6th out of 14). Importantly, across the composite ‘health factors’ measure, Cochise shows a worsening overall over the last 10 years, with specific declines in social and economic factors and physical environment indicators. The RWJF process encourages that the critical work, the work to evaluate and influence each of these modifiable health factors, be undertaken. This process will be reflected in each hospital’s Implementation Plan.

Figure 4: RWJF Health Model

Source: 2020 RWJ County Health Rankings

Table 4: Cochise County Health Rankings, 2011-2020

V. Health Behaviors

In the United States, the leading causes of death and disease are attributed to unhealthy behaviors. For example, poor nutrition and low levels of physical activity are associated with higher risk of cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, and obesity. Tobacco use is associated with heart disease, cancer, and poor pregnancy outcomes if the mother smokes during pregnancy. Excessive alcohol use is associated with injuries, certain types of cancers, and cirrhosis.

Addressing health behaviors requires strategies to encourage individuals to engage in healthy behaviors, as well as ensuring that they can access nutritious food, safe spaces to be physically active, and supports to make healthy choices.

Chronic Disease and Related Behaviors

The most common behavioral contributors to chronic disease morbidity or mortality include diet and activity patterns, and the use of alcohol, drugs, tobacco, and firearms. Importantly, the social and economic costs related to these behaviors can all be greatly reduced by changes in an individual’s behaviors.

The burden of chronic disease is greater in the joint Service Area and the County than in the State as a whole. As can be seen in Figure 5, the self-reported rates of being overweight or obese or having diabetes and high blood pressure are significantly higher. People who have obesity, compared to those with a normal or healthy weight, are at increased risk for many serious diseases and health conditions, including the following, to name a few.

▪ All-causes of death

• High blood pressure

• Diabetes

• Coronary heart disease

• Stroke

Chronic disease indicators are closely connected and can result in a significant personal and community burden. As

WHAT ARE HEALTH BEHAVIORS?

Health behaviors are actions individuals take that affect their health. They include actions that lead to improved health, such as eating well and being physically active, and actions that increase one’s risk of disease, such as smoking, excessive alcohol intake, and risky sexual behavior.

Key Findings:

▪ The Northern Cochise and Benson’s Service Areas as well as the County have higher rates of chronic disease indicators than the State, including diabetes, high blood pressure and obesity.

▪ Cochise County is less physically active and, has less access to exercise opportunities than the State as a whole.

▪ 1 in 5 children in the County do not have access to nutritious food.

▪ The County has higher rates of poor mental health days than the State.

▪ Adult and youth smoking are of significant concern in the County, as is binge drinking among youth.

identified in Table 5, in Cochise County this burden is expressed in the fact that 4 of the 5 top leading causes of death are related to chronic diseases According to the Centers for Disease Control, chronic diseases are among the most common, costly, and preventable of all health problems.

Figure 5: Chronic Disease Indicators

Cochise County Arizona

Source: 2019 UDS Mapper

Rates per 100,000 for Selected Leading Causes of Death, Cochise County and Statewide, 2019

Source: Arizona Department of Health Services

Diet and activity patterns are closely correlated with chronic disease. Not surprisingly, and as shown in Table 6 the percent of the population in the County that is physically inactive (25%) is higher than the State (22%) and the top U.S. County performers (20%). Importantly, the percent of adults who live reasonably close to exercise opportunities in the County is over 50% lower than the percent Statewide.

Evidence suggests teen pregnancy significantly increases the risk of repeat pregnancy and of contracting a sexually transmitted infection (STI), both of which can result in adverse health outcomes for mothers, children, families, and communities.

The number of teen births in the County exceeds that of the State or top U.S. performing counties (34 per 1,000 females ages 15-19) compared to 27 and 13, respectively.

Alcohol impaired driving deaths significantly contributes to unintentional injuries (the only top cause of death in the County that is not directly related to chronic disease). A third of all trafficrelated deaths involve alcohol, and drunk driving is the number one cause of death among teenagers. The potential for death is much higher for drunk driving incidents compared to other types of alcohol-related injury. The percent of alcohol impaired driving deaths is significantly higher in the County (31%) than the State (25%) – and importantly 180% higher than top performing counties.

Table 5:

Told they Have Diabetes Ever told they have High Blood Pressure

Benson Northern Cochise

Table 6: County Health Behaviors

Adult physical inactivity (% of adults ages 20+ reporting no leisure-time physical activity in the past month)

Access to exercise opportunities (% of adults who live reasonably close to exercise activities)

Alcohol-impaired driving deaths (% of motor vehicle crash deaths with alcohol involvement)

Teen births (# of births per 1,000 female population ages 15-19)

Source: 2020 RWJ County Health Rankings

Table 7 identifies that adults in Cochise County have a higher rate of premature death than the State. Years of Potential Life Lost (YPLL) is a widely used measure of the rate and distribution of premature mortality. Measuring premature mortality, rather than overall mortality, focuses on deaths that could have been prevented. The County also has a slightly lower life expectancy than the State, again reflecting the burden of chronic disease and accidents affecting Cochise County.

Poor or Fair Health measures the percentage of adults in a County who self-report that they consider themselves to be in poor or fair health. Poor Physical Health Days measures the average number of physically unhealthy days reported in past 30 days. Table 7 also identifies that the County has similar rates of these health status measures as do adults Statewide.

Access to Healthy, Sufficient Food

Poor physical health days in last 30 days

Source:2020 RWJ County Health Rankings

The lack of consistent access to a nutritious, balanced, sufficient amount food is called “Food Insecurity”, and is related to negative health outcomes such as weight gain and premature mortality. In addition to assessing the consistency of food availability in the past year, the food insecurity measure also measures the access of individuals and families to balanced meals.

Table 7: Health Status

Food insecurity among children is more common in Cochise County than the State as a whole with 1 in 5 children being food insecure. In the overall population (children, adults, and seniors combined), Cochise County’s rates are comparable to the State. As shown in Table 8, the Food Environment Index ranges from a scale of 0 (worst) to 10 (best) and equally weighs indicators of food insecurity and limited access to healthy foods. For this metric, Cochise County is slightly better than the State.

Behavioral Health

Table 8: Access to Healthy, Sufficient Food

Source: 2020 RWJ County Health Rankings

Cochise County Arizona Top U.S. Performers

Source: 2020 RWJ County Health Rankings

Behavioral health is an umbrella term that includes mental health and substance abuse, life stressors and crises, and stress-related physical symptoms. Behavioral health issues can negatively impact physical health, leading to an increased risk of some conditions. Unmet needs related to behavioral health services were identified as a priority in the 2017 Countywide CHNA. As seen in Figure 6, Cochise County adults report more poor mental health days than the State and the top U.S. performing counties, with County adults reporting on average 4.3 poor mental health days in the last 30 days, up from 3.7 in 2016.

Figure 7: Total Opioid Deaths Arizona, 2008-2018

Source: Arizona Department of Health Services 2018 Opioid Deaths & Hospitalizations

Opioids are a class of drugs that include the illegal drug heroin, synthetic opioids such as fentanyl, and pain relievers available legally by prescription, such as oxycodone (OxyContin®), hydrocodone (Vicodin®), codeine, morphine, and many others. When used correctly under a health care provider's direction, prescription pain medicines are helpful. However, misusing prescription opioids risks dependence and addiction.

Figure 6: Poor Mental Health Days

As can be identified in Figure 7, Arizona’s rate of opioid attributed deaths increased steadily between 2012 (454 deaths) and 2018 (1,167 deaths). This equates to a rate per 100,000 in the State of 15.67. Per Figure 8, Cochise County’s death rate is lower than the State at 11.51.

In 2019, Cochise County experienced a total of 78 drug overdose deaths (all types) or a rate of 21 deaths per 100,000. The State’s rate was 22 per 100,000. Both the County and State rates were significantly worse than the nation’s top performer counties at 10 per 100,000. For these measures, no NCCH or Benson Service Area data is available.

Figure 8: Total Opioid and All Drug Death Rate Per 100,000

Total Opioid Death Rate All Drug Death Rate

Cochise County Arizona

Source: Arizona Department of Health Services 2018 Opioid Deaths & Hospitalizations; 2020 RWJ County Health Rankings

While the numbers are low, the percentage of County students reporting heroin use in the last 30 days is higher than the State (see Figure 9), and this number is largely driven by use by 12th grade students (which has increased from 0.4% in 2016 to 1.7% in 2018). On a more positive note, and as identified in Figure 10, the students reporting prescription opioid use in 2018 is significantly less than the Statewide rate. Of concern is that the percentage of 8th graders reporting prescription opioid use has increased slightly since 2016 from 3.9% to 4.3% while use has declined among 10th and 12th graders.

Figure 9: % of Students Reporting Heroin Use in Last 30 Days, 2018

Figure 10: % of Students Reporting Unauthorized Prescription Opioid Use in Last 30 Days, 2018

Grade 8 Grade 10 Grade 12 Total

Cochise County State

Source: 2018 Arizona Youth Survey

Grade 8 Grade 10 Grade 12 Total

County State

Source: 2018 Arizona Youth Survey

Cochise

Smoking and Alcohol Use

Adult smoking is a critical component of the burden of chronic disease and should be a key focus of prevention. Cigarette smoking harms nearly every organ of the body, causes many diseases. Cigarette smoking is the leading preventable cause of death in the United States. Smokers are more likely than nonsmokers to develop heart disease, stroke, and many forms of cancer. As can be identified in Figure 11, smoking is more prevalent in the Northern Cochise and Benson Service Areas and the County than the State.

Binge drinking, defined as males having five or more drinks on one occasion, females having four or more drinks on one occasion, is the most common, costly, and deadly pattern of excessive alcohol use in the United States.

Binge drinking is a risk factor for a number of adverse health outcomes, such as alcohol poisoning, hypertension, acute myocardial infarction, sexually transmitted infections, unintended pregnancy, fetal alcohol syndrome, sudden infant death syndrome, suicide, interpersonal violence, and motor vehicle crashes.

Binge drinking is less prevalent in the Service Areas and the County; however, and as can be identified in Table 6 on page 20, alcohol impaired driving rates are significantly higher in the County (31%) than the State (25%), and far exceed the nation’s top performing counties (11%)

Source: UDS Mapper

Similar to the data for the adult population, Cochise County youth smoking and vaping data is concerning. Cigarette smoking during adolescence causes significant health problems among young people, including an increase in the number and severity of respiratory illnesses, decreased physical fitness and potential effects on lung growth and function. Most importantly, this is when an addiction to smoking takes hold, often lasting into and sometimes throughout adulthood. Among adults who have ever smoked daily, 87% had tried their first cigarette by the time they were 18 years of age, and 95% had by age 21. Figure 12 shows that student vaping usage is up across all grades since 2018.

Binge Drinking Smoking

Figure 11: Service Area Health Behaviors

Benson Northern Cochise Cochise County Arizona

Figure 12: Cochise County Student Electronic Cigarette (Vaping) Usage, 2016-2018

Figure 13: Cochise County Student Cigarette Usage, 2014-2018

Grade 8 Grade 10 Grade 12

Source: 2018 Arizona Youth Survey

Grade 8 Grade 10

Source: 2018 Arizona Youth Survey

Grade 12

As can be seen in Figure 13, while general cigarette smoking is down since 2016 in the 8th grade, it is increasing again in grades 10 and 12 after a decline between 2014 and 2016. For both types of cigarette usage, student use in the County is above the State level for all grades. Most significantly, electronic cigarette usage in the 12th grade is at 36.4% compared to 26.1% in the State, and general cigarette usage in the County is at 19.8% compared to 7.4% in the State

While adults in the County have lower rates of binge drinking than the State, there is a significantly higher rate of student binge drinking (defined as having had 5 or more drinks in a row at least once during the previous two weeks) in the County than the State. Binge drinking is the most common pattern of alcohol consumption among high school youth who drink alcohol and is strongly associated with a wide range of other health risk behaviors. Per Figure 14, over 26% of 12th grade students in Cochise County reported binge drinking While not shown in Figure 14, since 2016, this rate has increased significantly for students in the 10th grade (from 10% to 18%) and 12th grade (from 18% to 26%).

8

14: Student Binge Drinking, 2018

10

Source: 2018 Arizona Youth Survey

Figure

VI. Clinical Care

Access to affordable, quality, and timely health care can prevent disease by detecting and addressing health concerns early. Understanding clinical care in a community helps in understanding how the community can improve the health of its neighbors.

Advances in clinical care over the last century, including breakthroughs in vaccinations, surgical procedures like transplants and chemotherapy, and preventive screenings have led to significant increases in life expectancy. Clinical care and practice continue to evolve, with advances in telehealth and care coordination leading to improved quality and availability of care.

Those without regular access to quality providers and care are often diagnosed at later, less treatable stages of a disease than those with insurance, and, overall, have worse health outcomes, lower quality of life, and higher mortality rates.

WHAT IS INCLUDED IN CLINICAL CARE MEASURES?

Clinical care includes what people view as medicine: primary care providers, vaccines, screenings, surgery, etc. Access means making sure all people can get these services in convenient, timely, and affordable ways. There are many barriers to accessing health services, from financial to geographic limitations. Provider ratios per 1,000 residents and rates of insured are also important factors.

Key Findings:

▪ 1 in 4 residents in the Service Area are without a usual source of health care.

▪ Over 50% of Service Area and County residents have not seen a dentist in the last year.

▪ The Service Areas and Cochise County are designated as health professional shortage and medically underserved areas and have worse resident to provider ratios than the State

▪ A significantly smaller percentage of Medicare recipients in Cochise County receive flu vaccines and mammography screenings than in the State.

Primary Care Access Measures

Having a usual source of care defined as a personal doctor or other health care provider like a health clinic where someone would usually go if they were sick is seen as a strong indicator of health care access. Figure 15 shows that 1 in 4 residents in the Service Area, County and State are currently without a usual source of care. This is concerning as patients with a usual source of care are more likely to receive recommended preventive services such as flu shots, blood pressure screenings, and cancer screenings. For patients without that, disparities in access to primary health care exist, and patients face barriers that decrease access to services and increase the risk of poor health outcomes.

Figure 15: Access to Care Measures

Aduts with No Usual Source of Care

Adults Who Have Delayed/Not Sought Care Due to Cost

Adults with No Dental Visit in Past Year

Source: UDS Mapper

The high cost of health care can also be a barrier to access for both insured people (particularly those with high deductibles) and the uninsured, and costs can be particularly burdensome for people in worse health. As seen in Figure 15, Benson and Northern Cochise Service Area residents are slightly more likely than State residents to have reported not seeking or delaying care due to cost.

The majority of adults who have not seen the dentist in the past year reported cost as the reason. A higher percentage of adults in both Benson and Northern Cochise Service Areas have not seen the dentist in the past year as compared to the County. The difference is even more significant when compared to the State (56% in Benson and 55% in North Cochise compared to 30% in the State).

Data from the Arizona Department of Health Services’ Primary Care Statistical Areas (PCSA) was used to drill further down on access. These PCSAs areas describe communities in Arizona where the local residents primarily obtain their health care and provide detailed information on the demographics, resources, hospital utilization, and health status. Cochise County is divided into five primary care statistical areas. Three of the areas have been used in this CHNA due to their

alignment with the defined Service Areas of Northern Cochise and Benson. The Willcox and Bowie PCSA aligns with the Northern Cochise Service Area and the Sierra Vista and Benson PCSAs combined mirror the Benson Service Area. There are two additional PCSAs to the south (Douglas and Pirtleville PCSA and Bisbee PCSA).

Low birthweight is a valuable public health indicator of maternal health, nutrition, healthcare access and poverty. Factors such as early intervention services, education, employment and economic opportunities, social supports, and availability of resources to meet daily needs influence maternal health behaviors, pregnancy outcomes and infant and child health. As can be seen in Figure 16, when comparing low birthweight by Arizona’s primary care areas, the Sierra Vista and Benson PCSAs (the Benson Service Area), have a low birthweight ranging from 69.6 in Benson to a high of 85.6 in Sierra Vista (which is significantly higher than the County and State).

Figure 16: Low Birthweight

Source: 2019 Arizona Department of Health Services Primary Care Area Statistical Profiles

Figure 17: Prenatal Care

Source: 2019 Arizona Department of Health Services Primary Care Area Statistical Profiles

Late prenatal care (defined as starting in the 3rd Trimester of pregnancy) and no prenatal care are both indicators of a lack of access to care and also lead to increased maternal and infant health risks, including lower birthweights and infant mortality. As Figure 17 suggests, the Willcox and Bowie PCSA (Northern Cochise Service Area) have a higher percentage of mom’s receiving late or no prenatal care than the Sierra Vista and Benson PCSAs (Benson Service Area) and the County and State.

Sierra Vista Benson Wilcox and Bowie

Low weight birth/1000 live births Teen Births/1000 females 14-19

Sierra Vista Benson Willcox and Bowie Cochise County Health Planning Region Arizona

Health Professional Shortages

The Federal Health Resources & Service Administration (HRSA) deems geographies and populations as Medically Underserved Areas (MUAs), Medically Underserved Populations (MUPs) and/or Health Professional Shortage Areas (HPSAs). Similarly, a HPSA designation identifies a critical shortage of providers in one or more clinical areas.

There are also several types of HPSAs depending on whether shortages are widespread or limited to specific groups of people or facilities including: a geographic HPSA wherein the entire population in a certain area has difficulty accessing healthcare providers and the available resources are considered overused; or a population HPSA wherein some groups of people in a certain area have difficulty accessing healthcare providers (e.g., low-income, migrant farmworkers, Native Americans).

Once designated, per Figure 18 below, HRSA scores HPSAs on a scale of 0-26, with higher scores indicating greater need. HPSA designations are available for three different areas of healthcare: primary medical care, primary dental care, and mental health care.

Figure 18: HPSA Scoring Criteria

Three scoring criteria are common across all disciplines of HPSA:

▪ The population to provider ratio,

▪ The percentage of the population below 100% of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL), and

▪ The travel time to the nearest source of care (NSC) outside the HPSA designation.

The following figure provides a broad overview of the four components used in Primary Care HPSA scoring:

Source: Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA)

These designations are important as more than 30 federal programs depend on the shortage designation to determine eligibility or funding preference to increase the number of physicians and other health professionals who practice in those designated areas. Table 9 reflects the County’s HPSA designations and scoring for the areas within the Northern Cochise and Benson Service Areas.

Table 9: Northern Cochise and Benson Service Area HPSA Designations

Source: HRSA Data Warehouse – HPSA Find

Communities to the south of our Service Areas - Bisbee and Douglas/Pirtleville –have much higher HPSA scores and are identified as high need, with scores as high as 25

HRSA’s MUAs and MUPs identify geographic areas and populations with a lack of access to primary care services. MUA/P score is dependent on the Index of Medical Underservice (IMU) calculated for the area or population proposed for designation. Under the established criteria, an area or population with an IMU of 62.0 or below qualifies for designation as an MUA/P.

MUA/P Indicators

• Provider per 1,000 population ratio

• % Population at 100% of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL)

• % Population age 65 and over

• Infant Mortality Rate

Source: Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA)

As seen in Table 10, both the Northern Cochise (Bowie/Willcox) Service Area and the Benson (Sierra Vista/Benson) Service Area are designated as Medically Underserved Areas by HRSA. Again, the Douglas/Pirtleville Service Area in southern Cochise County has a lower (worse) score than both the Northern Cochise and Benson Service Areas with a score of 53.9 compared to 61.0 and 58.9,

Source: Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA)

Table 10: Norther Cochise and Benson Service Area

Figure 19: MUA/P Scoring Criteria

respectively. The other Service Area in southern Cochise County, the Bisbee Service Area, is also designated as a Medically Underserved Population.

Figure 20: Resident to Provider Ratio (# or Residents to 1 Provider)

0 500 1,000 1,500 2,000

Primary Care Physicians

Dentists

Mental Health Providers

County Arizona Top U.S. Performers

Source: 2020 County Health Rankings

Further, the County as a whole has worse ratios for primary care providers, dentists, and mental health providers than the rest of the State, as can be seen in Figure 20; and Arizona as a whole also does not fare well against the rest of the nation. Arizona ranks 38th in the nation in the number of primary care providers per 100,000 population, 28th in number of dentists, 47th for mental health

Preventive Care

Key markers of access to health care in a community are the rates of preventive screenings and vaccines. Getting vaccinated prevents many life-threatening illnesses from ever occurring, and preventive screenings catch disease processes early so that treatments are more effective. Yearly influenza outbreaks can prove deadly to seniors, children, pregnant women, and people with asthma or who are immunocompromised, and vaccines prevent people from getting severe flu.

As can be identified in Figure 21, the rate of Medicare recipients in Cochise County who receive flu vaccines compared to the State is significantly lower (33% vs. 44%) as is the rate of mammography screening (37% compared to 41% Statewide). This is important as even the State’s rates for these preventive care measures are significantly lower than the U.S. top performers.

Figure 21: Preventive Care Measures

Mammography Screening Flu Vaccinations

Additional disparities in these rates arise when broken down by race. Per Table 11 below, among Medicare recipients in Cochise County, the flu vaccine rate for American Indian/Alaska Natives is 33% compared to 52% for the white population.

Cochise County Arizona Top U.S. Performers

Source: County Health Rankings

Disparities can also be seen with mammography screening rates when broken down by race. Only 33% of the American Indian/Alaska Native and Hispanic populations in Cochise County received recommended mammography screenings, compared to 38% of the white population.

Cochise

Source: County Health Rankings

Preventable Hospital Stays

Preventable hospital stays are hospitalizations for ambulatory-care sensitive conditions These are conditions that if diagnosed and treated in outpatient setting could have prevented a hospitalization. Preventable Hospital Stays can be classified as both a quality and access measure, as some literature describes hospitalization rates for ambulatory care-sensitive conditions primarily as a proxy for access to primary health care This measure may also represent a tendency to overuse hospitals as a main source of care. As shown in Figure 22, the Willcox and Bowie PCSA (Northern Cochise Service Area) is doing worse than the County and State in terms of the rate of preventable hospital stays with a rate of 67.3 per 1000 compared to 50.2 for the County and 42.4 for the State. The PCSAs within the Benson Service Area ranged from below the County and State (35.6 preventable hospital stays per 1000 residents) to a rate above the County State and Northern Cochise Service Area (68.1).

Source: 2019 Arizona Department of Health Services Primary Care Area Statistical Profiles

and Bowie Benson Sierra Vista County State

Figure 22: Preventable Hospital Stays/1000 Residents <65

Table 11: Preventive Care Measures by Race Cochise County

VI. The Social Determinants: Social and Economic Factors

Our basic social and economic supports good schools, stable jobs, and strong social networks are foundational to achieving long and healthy lives. For example, family-wage employment provides income that shapes opportunities around housing, education, childcare, food, medical care, and more. In contrast, unemployment limits these choices and the ability to accumulate savings and assets that can help cushion in times of economic distress.

Social and economic factors are not commonly considered when it comes to health, yet strategies to improve these factors can have an even greater impact on health than many strategies traditionally associated with health improvement.

As can be identified in Table 12, according to measures of social and economic supports, Cochise County is in-line with the State in terms of income inequality (measured as the ratio of household income at the 80th percentile to income at the 20th percentile) and in terms of children in single parent homes. Importantly, both the County and State are performing worse than the top U.S. counties, with 1 in 3 children living in single parent households. Children in singleparent households are at higher risk for social isolation, have an increased risk for illness, and mental health problems, and are more likely to engage in unhealthy behaviors than their counterparts. The County fares relatively well on violent crime rates (the number of reported violent crime offenses per 100,000 population).

WHAT ARE SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC FACTORS

Social and economic factors, such as income, education, employment, community safety, and social supports significantly affect how well and how long we live. These factors affect our ability to make healthy choices and to afford medical care and housing.

Key Findings:

▪ Both Service Areas and the County have higher rates of unemployment and lower median household income.

▪ The Benson Service Area and the County have more people living in poverty than the State.

▪ The Northern Cochise Service Area has a significantly higher percentage of uninsured individuals.

The Service Area and County are doing worse than the State in terms of unemployment and median household income.

▪ Cochise County youth exhibit more risk factors than in the State including high family conflict, low commitment to school and perceiving that drugs are easily obtainable.

Table 12: Social Indicators

The Benson Service Area and the County have a higher percentage of the population living below the federal poverty level than the State, but the NCCH Service Area is faring better (15.7% compared to 16.1% Statewide and around 17% in the Benson Service Area and County). There are also discrepancies at the Service Area level related to health insurance coverage with the Northern Cochise Service Area having a much higher percentage of the population with no health insurance than the Benson Service Area and the County

Table 13: Socioeconomic Status

Source: 2014-2018 American Community Survey, * Statistics not available for 85644 (Willcox)

Poverty is defined by family size and income and is the primary measure of financial stability. However, many families living above the poverty line still cannot make ends meet. Using the Arizona Department of Health Services PCSAs, we were able to also look at the percentage of people within these areas that are at 200% of the poverty level and children (under age 12) in poverty. As seen in Figure 23, the rates for both in the Benson PCSA (a portion of the Benson Hospital Service Area) is higher than the other PCSAs, the County, the region, and the State in terms of both indicators. All of the PCSAs representing the hospital Service Areas except Sierra Vista are faring worse in terms of poverty level than the County, region, or State, with Benson the highest at 44.2%. below 200% percent of poverty. At 26.9%, children in poverty Cochise County are doing better than the region (27.4%) and worse than the State (24.2%).

Source: 2019 Arizona Department of Health Services Primary Care Area Statistical Profiles

As seen in Figure 24, other social indicators at the PCSA level show that the Willcox and Bowie (Norther Cochise Service Area) have higher percentages of the population whose highest degree is high school (35%) than the other areas, and that again the two PCSAs within the Benson service are significantly different with Sierra Vista with the lowest percentage at 19% and Benson higher than the County or State at 28%. High school success is an important marker of community health and wellbeing

Source: 2019 Arizona Department of Health Services Primary Care Area Statistical Profiles

Figure 23: Poverty Level

Sierra Vista Benson Willcox and Bowie Cochise County Health Planning Region Arizona

Figure 24: 2018 Socioeconomic Indicators By Arizona Primary Care Areas

Sierra Vista Benson Willcox and Bowie Cochise County Health Planning Region Arizona

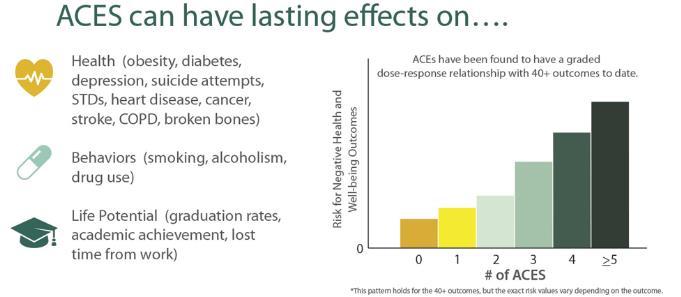

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) and Trauma

Adverse Childhood Experiences, or ACEs, are traumatic events that occur in childhood and cause stress that changes a child’s brain development. Exposure to ACEs has been shown to have adverse health and social outcomes in adulthood, including but not limited to depression, heart disease, COPD, risk for intimate partner violence, and alcohol and drug abuse. ACEs include emotional, physical, or sexual abuse; emotional or physical neglect; seeing intimate partner violence inflicted on one’s parent; having mental illness or substance abuse in a household; enduring a parental separation or divorce; and having an incarcerated member of the household.

Source: Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, “Association Between ACEs and Negative Outcomes”

The relationship of ACEs to adult physical and mental health outcomes in Arizona was explored using the 2008 Arizona Health Survey. A random sample of more than 2,400 Arizona residents was given a form of the ACE Survey. The findings were consistent with the initial ACE Study and other States ACE studies. Data from this survey shows that ACEs are common in Arizona. In fact, more than half (57.5%) of Arizona adults have experienced at least one ACE. The number of ACEs is tied to income level, family structure, ethnicity, insurance status and the educational attainment of adults in the household.

Beyond this, ACEs frequently occur together. A separate study found that one in four Arizonan has experienced one ACE. One in three has experienced two or more. The fact that significantly, more Arizonans report multiple ACEs than those who report just one has potential implications because the higher the ACE score, the greater the risk for numerous health and social problems throughout a person’s lifetime. For example, Arizonans with more ACEs were more likely to rate their health as fair or poor, to report smoking, to have been diagnosed with gastrointestinal or autoimmune disorders, to have been diagnosed with depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, or other mental disorder, and to have serious employment problems.

According to the 2011-2012 National Survey of Children’s Health, ACEs are common in Arizona’s children as well. Over one-quarter (26.4%) of children ages 0 to 17 experienced one adverse

Figure 25: Association between ACEs and Negative Health Outcomes

family experience and nearly one-third (31.1%) have experienced two or more. This is significantly higher than the national average of children experiencing two or more ACEs (22.6%). Even worse, in Arizona children ages 12 to 17, 44.4% have experienced two or more ACEs, compared to the national average of 30.5%.

Youth Risk Factors

Risk and Protective Factors (RPF) are personal and environmental factors that influence a person’s likelihood of engaging in problem behaviors. Risk Factors increase the chances of participation in problem behaviors, while Protective Factors decrease this likelihood. The RPF scales included in the Arizona Youth Survey are grouped into four domains: peer/individual, family, school, and community. Figure 26 combine these factors to determine the percentage of children exhibiting any of these risk factors. In Cochise County as compared to the State, youth exhibit slightly more risk factors overall.

Grade 8

Grade 10

Grade 12 Total

Figure 26: % of Students with risk factors

Cochise County State

Source: 2018 Arizona Youth Survey

VII. Physical Environment

Clean air and safe water are necessary for good health. Air pollution is associated with increased asthma rates and lung diseases, and an increase in the risk of premature death from heart or lung disease. Water contaminated with chemicals, pesticides, or other contaminants can lead to illness, infection, and increased risks of cancer.

How Does the Physical Environment Affect Health?

The physical environment is where individuals live, learn, work, and play. People interact with their physical environment through the air they breathe, water they drink, houses they live in, and the transportation they access to travel to work and school. Poor physical environments affect our ability and that of our families and neighbors to live long and healthy lives.

Key Findings:

▪ 1 in 6 individuals in the County face severe housing problems, and 1 in 3 renters spend more than 30% of their gross income on rent.

▪ An estimated 357 people experience homelessness on a given night in Cochise County (58 are unsheltered and another 299 are sheltered).

▪ With the exception of emergency shelters, all other homeless shelter options in the County are at capacity.

▪ Air quality fares worse in the County than the State.

Stable, affordable housing can provide a safe environment for families to live, learn, grow, and form social bonds. Housing is often the single largest expense for a family, and when a large proportion of a paycheck goes to paying the rent or mortgage, the high housing cost burden can force people to choose among paying for other essentials such as utilities, food, transportation, or medical care.

Our collective health and well-being depend on opportunity for everyone, yet across and within communities there are stark differences in the opportunities to live in safe, affordable homes, especially for people with low incomes.

Housing

RWJF County Health Rankings data provides estimates of individuals who have ‘severe housing problems,’ meaning individuals who live with at least 1 of 4 conditions: overcrowding, high housing costs relative to income, lack of a kitchen, or lack of plumbing. Similarly, RWJF defines a “cost burdened” household as a household that spends 50% or more of their household income on housing.

While Table 14 identifies that the County’s costburdened households and severe housing problem rates are lower (better) or in-line with the State, the reality is that many families in the County are still struggling; with 1 in 6 individuals facing severe housing problems. Importantly, and also shown in Table 14, 1 in 3 renters in Cochise County are spending more than 30% of their household income on rent. Households experiencing these cost burdens have to face difficult trade-offs in meeting other basic needs. When the majority of a paycheck goes toward the rent or mortgage, it makes it hard

to afford health insurance, health care and medication, healthy foods, utility bills, or reliable transportation to work or school. This, in turn, can lead to increased stress levels and emotional strain.

Table 14: Housing Issues

Severe Housing Problems

Housing Cost Burden (spend more than 50% of household income on housing)

Cost Burdened Renters (spend more than 30% of household income on housing)

Source: County Health Rankings, ACS 2014-2018

Being homeless puts an individual at increased risk of multiple health issues including psychiatric illness, substance use, chronic disease, musculoskeletal disorders, skin and foot problems, poor oral health, and infectious diseases such as tuberculosis, hepatitis C and HIV infection. As seen in Figure 27, the Arizona Point in Time Homeless Count identified 58 homeless residents in Cochise County in June of 2020. Of these 58 individuals, over 60% identified that they had been homeless for over a year, another 34% for over three years. As shown in Figure 26, 45% of the 58 homeless residents were from the Benson Hospital Service Area, with 38% from Sierra Vista and 7% from Benson. None of the respondents identified as being from the NCCH Service area. Over 40% were facing substance abuse or serious mental illness and almost 25% identified challenges with chronic disease or chronic illness.

Figure 27: Cochise County 2020 Point in Time Homeless Count

Source: Arizona Department of Economic Security Point in Time Homeless Survey

In addition to the identified 58 homeless (non-sheltered) in Cochise County, an additional 299 individuals were identified who are experiencing homelessness but are currently sheltered in an emergency shelter, transitional housing, permanent supportive housing, or rapid rehousing. Rapid rehousing places a priority on moving families and individual into permanent housing (3-24 months) as quickly as possible and assists in paying rent until the individual or family can pay on their own. Figure 28 identifies the State of the housing crisis by demonstrating that all of the housing options other than emergency shelters in the County are currently at capacity.

Sheltered County Capacity

Source: Arizona Department of Economic Security

Air and Water Quality

RWJ’s County Health Rankings measures air pollution by the particulate matter in the air. It reports the average daily density of fine particulate matter in micrograms per cubic meter. Fine particulate matter is defined as particles of air pollutants with an aerodynamic diameter less than 2.5 micrometers (PM2.5). As seen in Figure 29, Cochise County fares worse than the State on this measure of air quality.

Ensuring the safety of drinking water is important to prevent illness, birth defects, and death. One method for measuring the safety of water in a community is to evaluate drinking water violations (defined as at least one community water system in the area receiving at least one healthbased violation in the last year).

Cochise County is one of 12 of the State’s 15 counties that received at least one drinking water violation in 2018.

Source: 2020 RWJ County Health Rankings

Cochise County Arizona U.S. Top Performers

Figure 29: Air Pollution - Particulate Matter

Figure 28: Point in Time Shelter Count

VIII. Community Convening

In prior CHNAs, the hospitals undertook robust community convening processes that included a community needs survey, community meetings and stakeholder engagement to assess, identify, and prioritize community needs. After much discussion, this year, due to COVID, the two hospitals chose to distribute an online survey to community leaders in each hospital Service Area and County-wide as well as to organizations that serve the vulnerable and to Public Health. 62 total surveys were sent, and survey responses were received from 26 individuals, for a 40% response rate. Surveys were received from the following organization types:

▪ City Government

▪ Schools

▪ Higher Education

▪ Community Service Organizations

▪ Senior Service Agencies

▪ Active Living and Nutrition Organizations

▪ Local Parks and Recreation

▪ Community Health Centers

▪ Hospital Providers

▪ Local Businesses

▪ Local Utility Organizations

▪ Theater and Arts Associations

Given that many recipients were working remotely during this timeframe and given the alignment of the responses from those we received, we are confident that we received valid input.

The survey was designed to solicit feedback on perceived improvements in the areas prioritized in the 2017 CHNAs for each hospital. It also requested input on other potential health needs and gaps.

Separate surveys were sent to each hospital’s Service Area. While there was overlap in questions, this allowed for analysis of differences between the Service Area respondents. Specific questions on the 2017 strategies included:

Northern Cochise Community Hospital 2017 CHNA Prioritized Needs:

▪ Aging Concerns

▪ Substance Abuse/Misuse

▪ Diabetes and Obesity, including Healthy Eating

Benson Community Hospital 2017 CHNA Prioritized Needs:

▪ Good Jobs and Healthy Economy Future State

▪ Mental Health and Alcohol/Substance Abuse

▪ Healthy Eating, Obesity and Diabetes

On a scale from 1 (no improvement) to 5 (much progress), please indicate the improvement you have experienced either personally or within the community over the past three years in relationship to the priority

Do you think the priority should continue to be a CHNA priority action in the coming years?

As shown in Figures 30 and 31, mixed responses were received regarding whether improvement was shown on priorities from the 2017 Implementation Plans with results leaning towards little to no improvement. Importantly 20-30% of respondents felt they did not have enough information to weigh in on whether improvement had been made, suggesting an opportunity for hospitals to do more to inform the community about their efforts and to measure change.

Figure 30: Community Survey Response

Improvement on NCCH Priorities

1=No Improvement; 5=Much Progress

Figure 31: Community Survey Response

Improvement on Benson Priorities

1=No Improvement; 5=Much Progress

1 or 2 3 4 or 5 Don't Know

Aging Concerns/Resources for Healthy Aging

Substance Abuse/Misuse Healthy Eating Resources

Good Jobs and a Healthy Economy Mental Health and Alcohol/Substance Abuse

As identified in Figures 32 and 33, the vast majority of respondents concluded that the priorities identified by each hospital should continue to be priorities in the upcoming years.

Substance Abuse/Misuse Aging Concerns

Healthy Eating, Obesity and Diabetes

Figure 32: NCCH Community Survey Response Should the Priority Continue to be a Focus? Don't Know No Yes

Figure 33: Benson Community Survey Response Should the Priority Continue to be a Focus?

Good Jobs and a Healthy Economy

Mental Health and Alcohol/Substance Abuse

Healthy Eating, Obesity and Diabetes

Through the data collected in preparing the 2020 CHNA, and after participation in, and/or close review of the Community Needs Assessment and Health Improvement Plans produced by other entities, the survey asked respondents to prioritize all of the identified needs The combined list included the priorities from the 2017 CHNA and: (1) Access to Transportation for Health and Social Services; (2) Information & Referral to Health and Social Services; (3) Improved Access to Primary Care; and (4) Improved Local Access to Specialty Care.

The majority of respondents felt that all of these priorities should be a focus in the coming years. However, when asked to rank the priorities by importance, the 2017 CHNA priorities continued to rise to the top.

Specifically, the survey asked respondents:

Of the priorities referenced in this survey which three do you identify as the top three priorities?

Combined results from both hospital’s Service Areas are depicted in Figure 34. When ranked compared to other priorities, Mental Health and Substance Abuse/Misuse (70%), Good Jobs and a Healthy Economy (62%), and Aging Concerns, Resources for Healthy Aging (53%) rose to the top.

For NCCH, Mental Health and Substance Abuse/Misuse and Aging Concerns were tied for the top priority (64%) with Good Jobs and a Healthy Economy at 57%. No other priorities received over 30% of responses. Healthy Eating (a 2017 CHNA priority for NCCH) was only identified as a top three priority by 7% of NCCH respondents.

For Benson respondents, Mental Health and Substance Abuse/Misuse was the top priority (75%) with Good Jobs and a Healthy Economy close behind at 67%. Healthy Aging (a NCCH 2017 priority) and Healthy Eating tied for the third priority at 42%.

Figure 34: All Survey Respondents Top 3 Priorities

Improved Local Access to Specialty Care

Improved Access to Primary Care

Information & Referral to Health and Social Services

Access to Transportation for Health and Social Services

Good Jobs and a Healthy Economy

Healthy Eating and Diabetes

Mental Health and Substance Abuse/Misuse

Aging Concerns. Resources for Healthy Aging

Respondents were also asked if there were other areas of health needs that were not addressed in the survey. The majority of “other” responses were actually related to existing priorities, with the majority focused on behavioral health including the need for additional mental health and substance use disorder services. Other needs identified included dental services for low-income adults, additional OB providers, additional gerontology providers, focus on whole person care, and more active living resources. One respondent provided a particularly in-depth response, as follows:

Services are needed for youth and young adults: after school programs, daycare, summer camp, enrichment activities, internships, healthcare (including mental health services) directed at the younger populations, child-friendly areas in stores and healthcare centers, etc. It is important that younger populations feel like they are part of the community so that they see opportunities for them to stay and/or return after they graduate. The local schools do this well, but beyond the schools I am not aware of many services offered in the community specifically for youth and young adults. If the services do exist, we need to find ways to make those more publicly known.

IX. Implementation Strategy

Consistent with 26 CFR § 1.501(r)-3, NCCH and Benson will both independently adopt an Implementation Strategy on or before the 15th day of the fifth month after the end the taxable year in which the CHNA is adopted, or by May 15, 2021. Prior to this date, the Implementation Plan will be presented to each hospital’s board for review and consideration. Once approved, the Implementation Plans will be appended to this CHNA and widely disseminated. It will serve as guidance for the next three years in prioritizing and decision-making regarding resources and will guide the development of a plan for each hospital that operationalizes their individual initiatives.