CARA & DIEGO ROMERO

Bearing Witness to the Anthropocene

October 12 - December 8, 2024

Landmark Arts, Texas Tech School of Art Lubbock, Texas

This publication accompanies the art exhibition titled CARA & DIEGO ROMERO: Bearing Witness to the Anthropocene which was organized by Landmark Arts, the Exhibitions and Speakers Program of the School of Art, Lubbock, Texas and presented in the Landmark Gallery of the School of Art October 12 – December 8, 2024. The exhibition was curated by Klinton BurgioEricson, Ph. D., assistant professor of Art History of the Americas at Texas Tech University. The exhibition and catalogue are presented in collaboration with the Humanities Center of Texas Tech’s 2024-2025 theme: “Celebrating Indigenous Resilience and Cultural Survival: Commemorating the 150th Anniversary of the Red River War."

Published by:

Landmark Arts in the School of Art Texas Tech University Lubbock, Texas 79409 www.landmarkarts.org

Copyright 2024 by the authors, artists, and Texas Tech University. All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may reproduced in any manner without permission from Texas Tech University.

Major support for the exhibition and the catalogue comes from the Still Water Foundation, Austin, Texas. Additional support comes from the Ryla T. & John F. Lott Endowment for Excellence in the Visual Arts administered through the School of Art, and from Cultural Activities Fees administered through the J.T. & Margaret Talkington College of Visual & Performing Arts.

ISBN: 979-8-9909856-2-9

Design: Grant Carter

Printing: Slate Group, Lubbock

Foreword

Joe Arredondo 04

“Rising Floods and Crackling Skies: Rereading the ‘Man Scape’ through Indigenous Eyes”

Klinton Burgio-Ericson, Ph.D. 05-14

Artwork Plates

Cara Romero Diego Romero Exhibition Checklist 36

October 12 - December 8, 2024 Landmark Arts, Texas Tech School of Art Lubbock, Texas 25-35 16-23

Landmark Arts in the School of Art is proud to present CARA & DIEGO ROMERO: Bearing Witness to the Anthropocene during the fall semester of the Humanities Center of Texas Tech’s year of “Celebrating Indigenous Resilience and Cultural Survival: Commemorating the 150th Anniversary of the Red River War." This exhibition brings together the artworks of Native artists Cara Romero (Chemehuevi) and Diego Romero (Cochiti Pueblo), partners in both life and artistic dialogue.

Curated by Klinton Burgio-Ericson, PhD, assistant professor of Art History of the Americans, the exhibition presents a selection of works that reflects the many hours spent over the summer collaborating with the artists to identify the subjects and themes that inform the organization of this exhibition. Klint’s essay in the exhibition catalog provides well considered assessments of Cara’s and Diego’s artworks within the theme of the exhibition. We are grateful for the assistance of the Cara Romero Gallery staff for their support in lending Cara’s photographs for the exhibition. We especially wish to extend our heartfelt thanks to Mark

Boardman and Olga Vidiaikina of Lubbock who generously loaned the Diego Romero pieces in the exhibition from their private collection.

Landmark Arts is grateful for the generous grant from the Still Water Foundation of Austin, Texas providing major support for this exhibition. Additional support comes for Cultural Activities Fees administered by the J.T. & Margaret Talkington College of Visual & Performing Arts. A special grant from the Ryla T. & John F. Lott Endowment for Excellence in the Visual Arts administered through the School of Art makes it possible to host Cara and Diego Romero in a special evening of conversation as part of the Humanities Center of Texas Tech series of events.

Joe Arredondo Director of

Landmark Arts

...human industry, environmental degradation, and climate change have irreversibly transitioned our environment into a new geological era in which human impacts dominate.

“Rising Floods and Crackling Skies: Rereading the ‘Man Scape’ through Indigenous Eyes”

By Klinton Burgio-Ericson

Amidst unprecedented weather, new temperature records, and rising sea levels, the “Anthropocene” has become ubiquitous: a label that seems like an explanation and yet never satisfies our need to understand the changes in which we find ourselves. This concept developed in the 1980s to describe the fundamental alterations that we have wrought on the earth while indexing human anxieties over these impacts. Although contentious among some, it expresses the perception that human industry, environmental degradation, and climate change have irreversibly transitioned our environment into a new geological era in which human impacts dominate.

Growing awareness of these changes provokes responses from denial and panic, recriminations and internalized guilt, to resignation and fatalism. For some, human technology is causing this crisis, while others hope technological solutions will rescue us from generations of human choices. The Anthropocene is more than an objective description of changing epochs; it is also a challenge to the imagination as we seek to comprehend what we have made, wrestle with our responsibility, and understand our place in a world transforming around us.

Definitions vary, but some date the advent of the Anthropocene to the dawn of the Industrial Revolution in the eighteenth century, when carbon pollution began increasing exponentially. Not incidentally, this timeline overlaps with the expansion of settler-colonialism and assimilationism across North America, as settlers no longer sought treaties recognizing Indigenous priority, but rather to displace and erase their presence. Reflecting these entangled histories, the Anthropocene often looks quite different from Indigenous perspectives. Universalizing narratives of the Anthropocene frequently overlook Native experiences, while customary concepts have tended to diverge from mainstream ecology, positing an animate cosmos and relational philosophies in which humankind is essential to nature rather than apart from it.

As partners in both life and artistic dialogue, Cara Romero (Chemehuevi) and Diego Romero (Cochiti Pueblo) address the quandary of the Anthropocene not by passing judgement or despairing, but rather by bearing witness to the complexities of life in this period of radical transition. They view the Anthropocene through the lens of cultural landscapes, their histories, and the futures that might inform them. This show brings together nineteen works by the Romeros featuring their artistic dialogue and shared consideration of the Anthropocene and is the first exhibit to focus on their artistic partnership in itself.

Both have honed distinct styles that predate their relationship. Cara’s large-scale, carefully staged, and vibrant archival pigment prints draw on her training in studio and commercial photography at the University of Houston, the Institute for American Indian Arts (IAIA), and Oklahoma State University. This style contrasts the objectifying ethnographic essentialism of Edward Curtis, as she seeks a more ethical and Indigenous approach to the medium, collaborating with her models to develop the final images.

Diego also studied at IAIA, as well as Otis Art Institute and UCLA. While his roots came out of traditional Pueblo pottery, he has chosen to pursue an experimental approach after learning from Otellie Loloma (Hopi) at IAIA from 1984-1986. He emphasizes carefully designed and rendered imagery painted on ceramic bowls and tiles, combining Mimbres-style figures, comic books, Greek vase painting, and pop culture. Diego has harvested and processed Cochiti clay, but since 2003 most of his work is commercial material fired in an electric kiln. It sits somewhat apart from customary Pueblo pottery, in which processes and materials are definitive characteristics, rather than form or style. Yet Diego’s work also belongs to his Pueblo context, drawing on ancestral imagery and design conventions, especially in his borders, as well as his care to honor cultural standards for appropriate imagery.

Today, much of Diego and Cara’s work arises from their mutual dialogue, and they share an ability to speak to greater human issues from the specificity of their cultural perspectives. Both come from mixed race backgrounds (like many Native artists today), and wrestling with this positionality has lent an honesty and critical edge to their work. Variously approachable, disarming, fallible, empathetic, and uplifting, their works assert resilient Native perspectives on and amidst the Anthropocene.

While predictions of climate change and rising sea levels are sobering, they are not unprecedented. Arguably, the Anthropocene is rooted in the Early Modern period, as European colonizers sought to fulfill the Christian origin story and take dominion over every living thing (Genesis 1:28). Conceptualizing the earth and its residents as resources to be exploited, this Imperialism led to human catastrophe as violence, labor coercion, and waves of disease reduced the Indigenous population of the Americas as much as ninety-five percent by the 1650s. Invasive new species wrought ecological havoc, while extractive industries produced widespread deforestation, desiccation, and pollution. Indigenous people who endured these hardships experienced the radical transformations of landscape presaging what is yet to come.

Diego’s early work looks back at this history of New Mexico’s colonization. In Agents of Oppression (1994, page 25), an Ancestral Pueblo man with dark skin, diamond-shaped eyes, long hair in a traditional bun, and a loin cloth barely covering his muscular physique kneels sullenly between a Franciscan priest and Spanish conquistador. His pursed lips and furrowed brow portend the rejection of Spanish governance during the 1680 Pueblo Revolt. With characteristic humor, Diego calls the Anthropocene the “manscape,” an ironic pun combining serious environmental concerns with a play on words about male grooming and narcissistic selfcenteredness. Inspired by early covers for Max Frisch’s novella Man in the Holocene (1979) that juxtaposed human and dinosaur skeletal remains, Diego manifests temporal consciousness through groundlines and cross-sectioned stratigraphy containing dinosaur bones, human skulls, ceramics and other traces of past occupants. Thus, the Pueblo man in Agents of Oppression kneels on ground full of his ancestors remnants.

Conceptualizing the earth and its residents as resources to be exploited, this Imperialism led to ... violence, labor coercion, and waves of disease

Since 1492, Native peoples have witnessed waves of colonialism and ecological devastation. For the Chemehuevi of the eastern Mojave Desert, U.S. territorial expansion initiated colonial violence, genocidal legislation, and landgrabs that have effects to this day. In 1848, California became a US territory, following the invasion of the Mexican American war. This subjected Cara’s ancestors to assimilationism that sought to strip them of their land, language, and culture. In the 1930s, Chemehuevi people witnessed the construction of the Parker Dam and Lake Havasu on the Colorado River, flooding 7,000 acres of their land. Displacement from their homes and wetland resources caused great sadness and urban relocation to centers such as Los Angeles, where Cara was born.

The Chemehuevi Indian Tribe reorganized and achieved federal recognition in 1970. Cara’s family returned to the reservation along the Havasu lakefront, with her grandmother serving as a tribal chairperson. Jackrabbit and Cottontail (2017, page 16) is set on the reservation with Lake Havasu in the background. A tattooed, mixed-race woman leans against a Volkswagen with her hand to her forehead, seemingly peering into the future. Her children wear black feathered headdresses, one gazing over the haunted waters, the other looking at us quizzically. They represent the Chemehuevi warrior twins, who made the world habitable for the first people in tribal origin stories. The washed-out color evokes late-century vernacular family photography, creating both nostalgia and also a sense that “we are Indigenous as we ever were in these modern times.”

Cara’s recurrent flood references are particularly relevant as sea level rise and flooding are anticipated with climate change. For Chemehuevi people, memories are fresh of the Army Corps of Engineers forcibly removing them from homes standing in rising lake water. Their experience presaged those of Indigenous people today in Alaska, who are relocating due to sea level rise, or Southwestern communities where climate-changefueled forest fires have denuded mountain valleys, allowing unprecedented flash flooding. Yet the Indigenous temporalities underwriting Cara’s photograph offer a counternarrative to the Anthropocene. Jackrabbit and Cottontail are cultural heroes and protectors of sacred sites, time travelers who “have returned to remind us of our deep connections to the land.” Her work contrasts the Eurocentrism of the Anthropocene concept, which imagines time as a linear progression, and humans as distinctly apart from the natural realms on which they act.

Cara seeks to change stereotypes locking Indigenous people in the past, decolonizing imagery by asserting the presence, agency, and diversity of Indigenous women, as for example in 2023’s Temiki (Little Death) (page 22) A Danza Azteca performer looks at us in skeletal calavera face paint and radiant quetzal blue-green headdress, while gripping two ears of New Mexico blue corn. In collaboration with makeup artist Dina DiVore (Jemez/Kewa) and model Crystal Clara Xochitl Zamora (Mexica/Azteca), this photograph asserts the continuity of Indigenous cultural practices in Mexico, where el Día de los Muertos draws on millennia of history to celebrate ancestors, feed the dead, and observe the passing seasons. By featuring

Cara seeks to change stereotypes locking Indigenous people to the past “

a dancer from Albuquerque, NM, Cara also calls attention to the international diaspora of Indigenous people and the continuity of their cultural observations in distant locales. Zamora’s father titled this piece, noting that for Nahua people, temiki means “little death,” describing the dream time of the afterlife. Zamora’s confident gaze through her makeup asserts the persistence of Indigenous people and their creative adaptations amidst colonization.

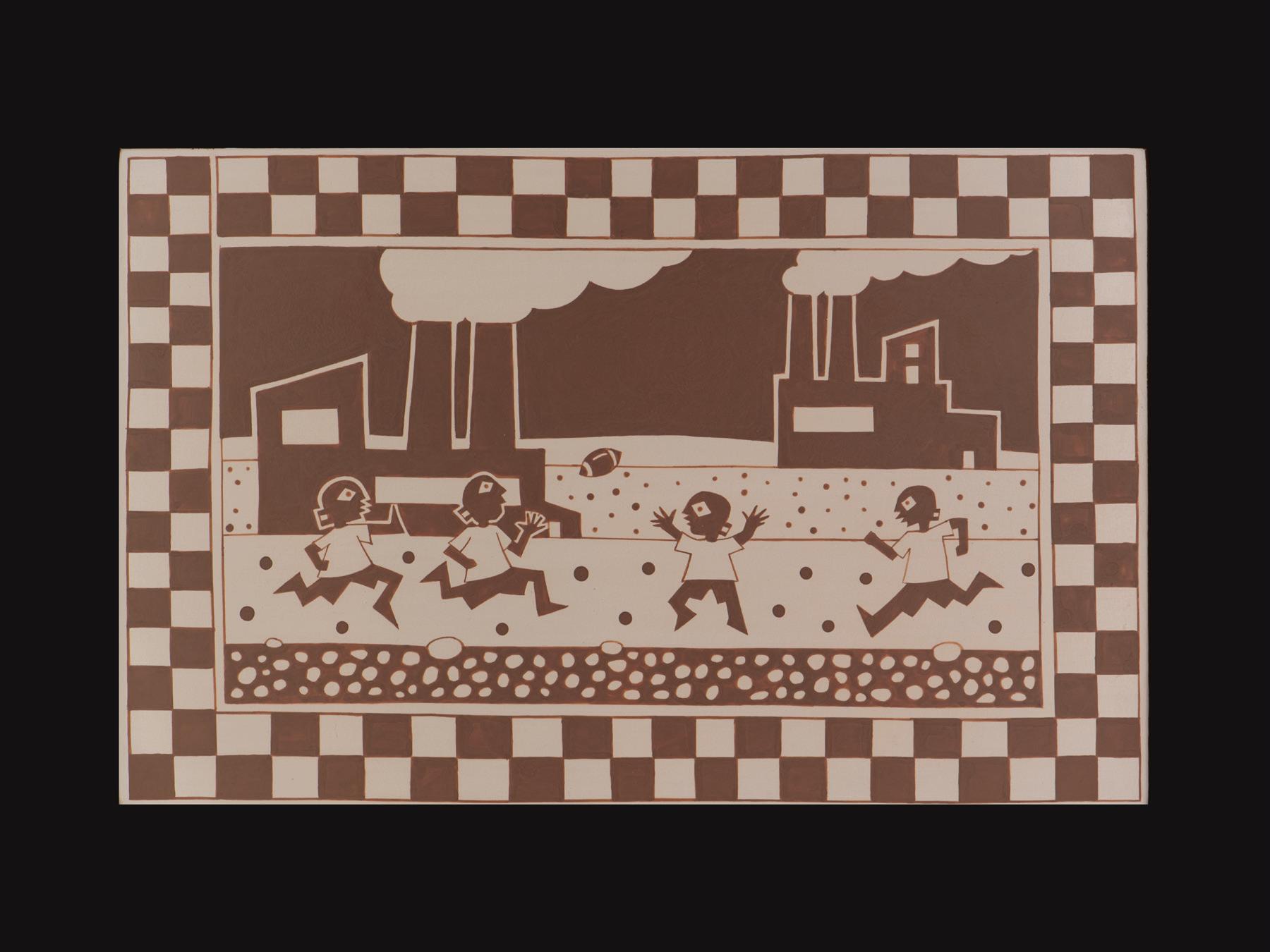

The challenges and resilience of Native people feature in Diego’s work as well. He derives his characteristic black-on-white silhouette figures with diamond eyes by fusing Mimbres style with Greek black-onred vase painting, while adding pop culture and comic book elements to create a unique visual language. In Man Scape 2018 (page 28), for example, Mimbres-style youths play American football in front of industrial factories belching out pollution from their smokestacks, symbols of environmental racism and settler dominance of the landscape. Occurring within a checkerboard pattern from Ancestral Pueblo pottery with associations of still water, corn, and plenty, these vivacious players stand upon a stratified ground and focus with the intensity of Ancient Greek athletes. Yet the scene suggests the precarity of many Native communities, where pollution from mining, the defense industry, and nuclear colonialism have produced unsafe living conditions and health disparities. The game is frozen in a moment of indecision, the football hanging in the air as the players rush to catch it, emblematic of the undecided outcomes for these children growing up on polluted ground.

Diego’s use of personal mythology is part of his strategy to lure viewers into contemplation of harder truths. Most important are the Chongo Brothers, stylized representations of himself and his brother Mateo (also an important painter) as timetravelling Mimbres explorers on an aimless quest through the pitfalls of modernity. Through this narrative projection, Diego renders the Anthropocene as an object of subversive critique, guiding us through its perils, heartbreaks, mundanity, and moments of beauty. Dead Chongo (c. 1994, page 26) is strikingly confessional, recalling Diego’s personal struggles with addiction by depicting Evangelo’s bar in Santa Fe, a local haunt for relaxing after the annual Indian Market. Drinking alone, the isolated Chongo Brother is a self-portrait, slumped over a bar, habitually seeing Mimbres eye closed in stupor, isolated and numb, drinking himself to death. The wider histories of alcohol as an insidious tool of settler colonialism and addiction in contemporary society become deeply personal, and Diego makes no excuses for his own fallibility. This unflinching honesty departs from the picturesque romanticism characteristic of Western and Indian art markets, while Diego’s sobriety since 2003 has facilitated the growing breadth of his artistic thought.

Diego renders the Anthropocene as an object of subversive critique, guiding us through its perils, heartbreaks, mundanity, and moments of beauty.

The Chongo Brothers reappear in American Highway (c. 2004-2005, page 27), wideeyed in disbelief as their pickup navigates an interstate amidst desert mesas, a steaming powerplant, and a semi-truck, the lifeblood of modern commerce, chugging in the opposite direction. The highway symbolizes wider economic factors of the global economy as the ultimate mark of the Anthropocene. Yet spiraling stepped-fret designs compress this panel, as if through the lens of a camera or video screen. The interlocking positive and negative frets form a swastika-like motif that symbolizes both the whirling logs of Navajo cultural stories and Pueblo migration accounts. This life-affirming frame thus seems to counterbalance the economic forces that the center panel puts in motion.

Cara envisions more conceptual roadways in Ty (2017, page 18). Diné model Ty Harris stands in crisp profile before the bold geometric patterns and brilliant colors of a Navajo blanket. She wears a necklace comprising numerous strings of rare Olivella shells, evoking the reverence that Harris and other Diné hold for White Shell Woman, one of their Holy People associated with the creation of humans near the Pacific coast. Cara worked with Harris and her frequent collaborator, Leah Mata Fragua (Northern Chumash) to design the custom necklace of cascading shells that Mata Fragua had collected over the past decade. Working on this project together reinvigorated ancestral trade routes, starting with Fragua’s coastal peoples, through the Mojave desert of the Chemehuevi, to the Southwest where the Navajo and Pueblo people live. As a portrait, Ty bears witness to these historical intertribal connections and serves as a reminder that environmental wellbeing

is intertwined with human relations, and hardships for Indigenous people adversely affect the lands they serve as caretakers. The concept of the Anthropocene separates humans from nature as inherently antagonistic, as its pressures have often tried to separate Indigenous people from their ancestral places and networks.

The road as signifier returns in Diego’s King of the Night (2023, page 33). Within an energetic double border of checkerboard and lightning patterns, this bowl contains a night scene of Coyote standing atop a mesa overlooking an industrialized desert. In his personal mythology, Diego draws upon diverse tribal mythologies presenting Coyote as equal parts trickster, troublemaker, clown, and conman. Here Diego eschews the howling canine of Southwestern kitsch to paint Coyote instead as bristling, one-eyed quadruped with pretentions of grandeur, lording over a cultural landscape increasingly strained by its own systems of productivity and the consequences of climate change.

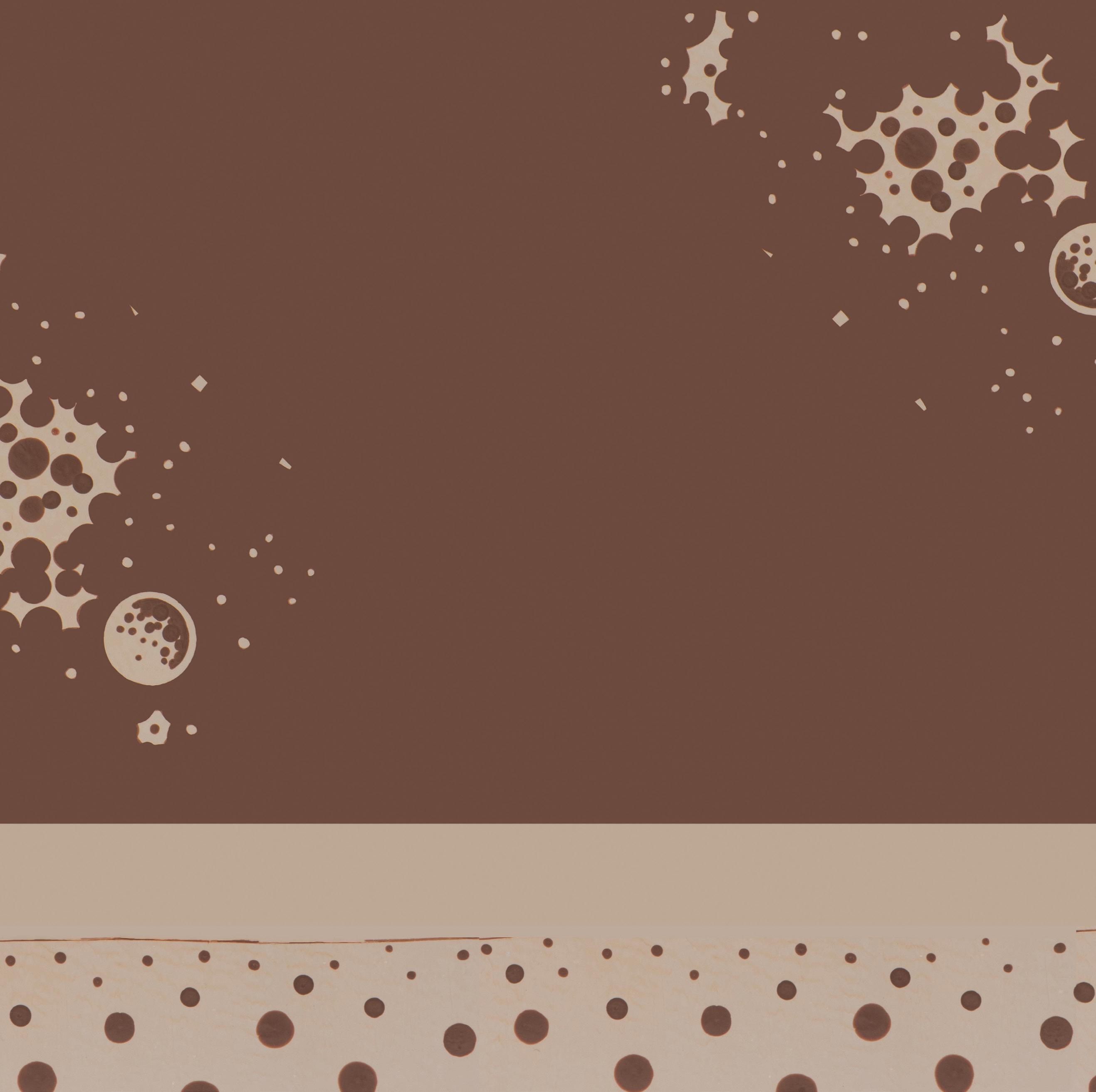

A busy interstate passes beneath Coyote, while smokestacks break the horizon, indexing reliance upon extraction and fossil fuels. And yet, Diego’s critique is rarely one-sided, and these highways also reactivate the vast network of Indigenous trade routes across changing landscapes, reflecting persistent human impulses to travel and explore. As if echoing the voyagers below, the heavens above roil with the energy of a comic book convention known as “Kirby Krackle,” after Jack Kirby. In works such as the Fantastic Four, Kirby popularized a dotted field of black to represent an unspecified source of cosmic energy through the interplay of field and ground. Here the sky’s energy reflects the stratified earth below, suggesting unrealized potential inherent in the landscape, and the mystery of a land in which ancient Indigenous mythoi remain present and potent. Coyote is still here among us, not separate from the modern tumult, but experiencing the same impacts on the landscape and hinting at hidden powers that remain immanent.

“We feel and believe that our DNA emerges from these landscapes and so we are ontologically tied to the landscape ”

Diego’s real-life hero appears as In Loving Memory of Otellie Loloma Traditional Pottery Instructor Institute of American Indian Art (2024, page 34). He regards Loloma as probably his most important mentor, transforming her into an icon. At the center of a swirling double-frame of golden luster, she appears in three-quarters view with a blanket around her shoulders and the calm sagacity of a presidential portrait, but the radiance of the Virgin of Guadelupe. Although Diego went on to study at UCLA under noted ceramicist Adrian Saxe, his initial experience at IAIA set his course in motion, and he was not alone in this. IAIA played an important role in midcentury Native arts, instigating an artistic revolution of Native artists with the stylistic freedom to speak out on broad social issues, comprising a vibrant and growing contemporary Native art movement.

The resurgence of Native arts and alternative perspectives on our present era reflects generational resilience in the face of colonial hardships, a theme that Cara dramatizes in her NDN Summer (2023, page 21). Two young women wearing coastal regalia and carrying an original Chemehuevi basket step delicately, hand in hand, through a red-tinted landscape. The models, Crickett Tiger (Muscogee Creek/Cochiti) and Naomi Whitehorse (Northern Chumash/Sicangu Lakota), wear regalia based on the shell and fiber traditions of California’s coast by Leah Mata Fragua. The regalia points to deep connections of the people to their landscape through art. “We feel and believe that our DNA emerges from these landscapes and so we are ontologically tied to the landscape,” Cara asserts. Indigenous people are bound to ancestral lands and each other as a community, which gives “maximum human value” to place. This place-based ontology and kincentric notion of relations contrasts mainstream western ecology, which posits the essential antagonism of humans to the health of nature.

Cara does not romanticize this scene. Alongside cultural signifiers such as abalone shell and woven baskets, the ground is littered with elements of the contemporary cultural landscape of Native communities: cell phones; tribal enrollment forms; and money hinting at both casinos and the genocidal 1849 gold rush. The red glow suggests wildfires and warming temperatures that now threaten California. These multiple and complex signifiers coexist as a minefield of intermingled popular and customary culture that the girls navigate with ginger confidence.

The even-handed and clear-eyed observations of these works are part of what makes them disarming. They render no easy judgement on the entanglements of the Anthropocene, nor romanticized versions of “authenticity” that would set Indigenous people apart from the worlds in which they live. Rather than proposing grand narratives of epochal shifts, their witness is in the particular and the local, representing experiences based in families, landscapes, and cultural communities they know best.

It is easier to critique what has been, than predict what the future holds. Yet Cara and Diego have both launched Indigenous futurisms that re-envision what the Anthropocene may become. If this is to be a new epoch, we stand at its beginning and our choices seed its future. Through their dialogue and complimentary artistic practices, the Romeros visualize alternatives shaped by Indigenous cultural values, perspectives, and philosophical contributions to counterbalance the negative heritage of becoming the Anthropocene. Theirs is an optimistic and aspirational view of humanity in relation to our environment, one not yet nor fully realized, one that is yet becoming.

Shivering with constrained energy, Cara’s Shameless (2017, page 17) is the starter pistol for this new vision. The sleek aerodynamic convertible seems less a gas-guzzling landship causing anthropogenic climate change, and more like an imaginative rocket poised for flight. Four Chemehuevi youth, brothers and relatives of the artist, sit atop the car dressed in feathers and urban streetwear of their choice. They lean towards the right, the wind catching their feathers and the palm fronds behind them, sweeping them forward. Even the contrail-like clouds above seem to be in motion. Like a mirage, the glossy blue finish of the car comes into and out of focus, filling the foreground and yet fusing with the blue lake behind it. Likewise, its mix of nostalgic and contemporary signifiers create a moment of time-traveling fantasy, with her father’s custom 1972 Cadillac rez car sitting dreamlike amidst a vision of flooded earth that is his backyard and our future all at once.

The Romero’s futurism carries a certain retrospective quality. Indigenous Futurism is a recent movement interweaving Native culture with pop and sci-fi references, based partly on earlier Afrofuturism. Rooted in black music and literature of the 1970s and 1980s, Afrofuturism comprises diverse artistic expressions of speculative fiction, aesthetics, and historical perspectives drawing on diasporic experiences to envision new futures through science fiction and fantasy. Diego pays tribute to this legacy with a tile dedicated to Uhura (c. 2018, page 29), Nichelle Nichols’s Star Trek character.

Indigenous Futurism is a recent movement interweaving Native culture with pop and sci-fi references

“over time, Indigenous identities fuse, and our histories are now woven together to become shared cultural experiences. ”

As communications officer for the USS Enterprise, Uhura was one of the first black characters in American television to have a major role equal to white counterparts. This small work looks backwards to commemorate the transcendence of racial barriers in American society, while also envisioning more equitable futures.

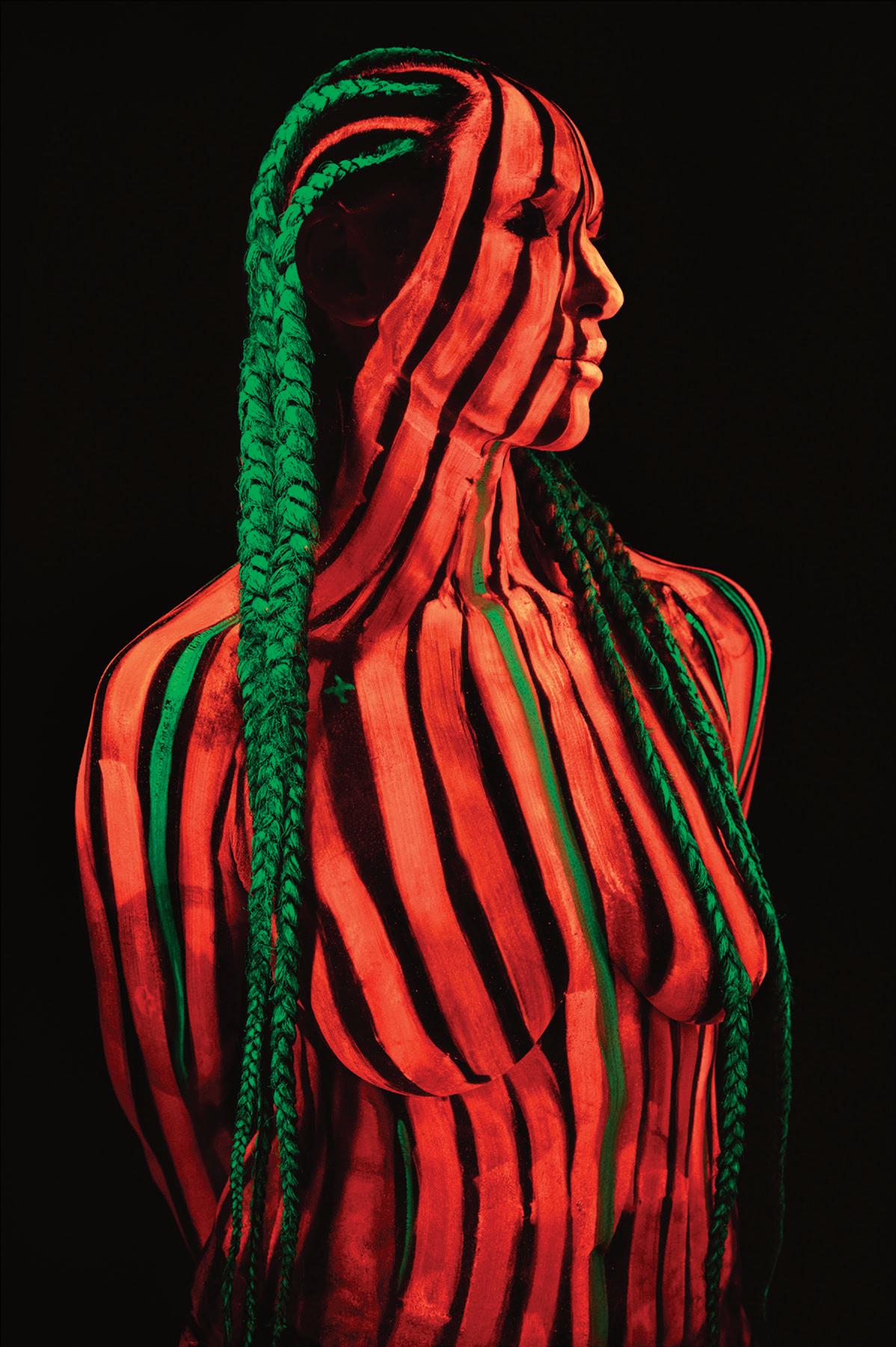

At a larger scale, Cara’s Alika No. 1 (2024, page 23) engages similar Afrofuturist aesthetics. Model Alika Sheyahshe-Mteuzi (Albkebu-lan, Africa/Kadohadacho, Caddo/ Cheyenne and Arapaho) appears nude from the waist up. Fluorescent stripes of red and green body paint define her contours, glowing vividly under blacklights against a tenebrous background, while the vibrant green details of her cornrows cascade down from her brow and off her chest. These radiant colors become an embodied panAfrican flag that directly references the cover art of A Tribe Called Quest’s second album, The Low End Theory (1991), while also suggesting futuristic aesthetics of works such as Marvel’s Black Panther, filled with glowing tech and body ornament, or Nigerian American photographer Mikael Owunna’s cosmic blacklight imagery. At the same time, the stripes represent more spectral and historical presences, referencing both Kadohadacho (Caddo) body paint, and the bodies appearing in T.C. Cannon’s paintings of Three Ghost Figures (1970). As with Cara’s other timetravelers, Alika envisions simultaneous temporalities bridging past and future, while foregrounding Black Indigeneity through an interracial Native model. As Cara explains, “over time, Indigenous

identities fuse, and our histories are now woven together to become shared cultural experiences.” Such complex, mixed-race stories and global histories are still rare within the field of Native art, despite their frequent reality among artists themselves. Alika’s futuristic intersectionality creates space for greater awareness, acceptance, and cross-cultural understanding of diverse subjectivities.

Diego’s recent work also embraces a more cosmic orientation after the historical and confessional qualities of earlier work. Kirby Crackle frequently replaces the stratified landscapes with an expansive field and deep potential, as for example in Cosmic Parrots (2023, page 32). Two rigid macaws float amidst galaxies, exploding stars, and drifting planets, facing opposite directions in a yin-yang configuration. Together, the parrots represent a cosmological vision of the terrestrial and spirit worlds existing side-by-side but never actually touching. These same crackling star fields encircle a globular jar entitled Gods, Demigods, and Heros (2021, page 31), with the rambunctious composition straining its golden borders. Diego’s creatures cavort weightlessly in these dazzling heavens. Here again is the cyclopean coyote, kicking back with his one eye fixed upon us. Here too the cosmic parrot, overseeing supernovas and speckled nebulae. Between them is the powerful, writhing body of Avanyu (or Awanyu), the Pueblo horned serpent and guardian of the world’s interconnected waters. He passes through a worm hole from one side of the pot to the other, suggesting that the more-thanhuman beings of Pueblo cultures not only survive, but already belong amongst the futuristic and speculative worlds that we call science fiction.

Occupying the same glittering void, Cara’s dreamy photograph of The Zenith (2022, page 20) pictures an astronaut in blue jumper and helmet floating weightlessly amidst a cloud of unshelled white corn. The zenith is a sacred direction for many Native cultures, and among the Pueblos, each of the six directions is coded with particular colors of corn. While it is not necessary to match the white corn of this photograph with specific cultural symbolism, its juxtaposition with the “highest point on the celestial sphere” evokes a distinctly Indigenous imaginary, as Cara reflects upon the place of Native heritage varieties—themselves timetravelers through millennia of careful cultivation—in our collective futures. Muscogee-Creek painter George Alexander modeled for this photograph in his iconic astronaut helmet, which he adopted after watching the 2014 Christopher Nolan film Interstellar. The helmet appears in his paintings as a metaphor for the expansive perspective that comes from reaching the zenith and looking back. Here Alexander in turn becomes part of playful scene, with the reflection of studio lights visible in his visor. Interstellar’s plot driver was the imminent failure of maize, that great Indigenous American contribution to the world, as its genetic mutability reaches its adaptive limits; Cara’s photograph instead expresses faith in Indigenous peoples’ collective ability to adapt and meet the challenges of the future.

This futurism comes full circle in one of Diego’s most recent works, Masewa and Oyoyewa (2024, page 35). A large olla or water jar sports two cosmic panels, with hatchured pairs of four-pointed stars and checkerboard bands separating them. Named after the hero twins of Keresan oral histories, Diego none-the-less imagines these as pan-Indian protectors. Similar mythologies occur widely, from the Yucatan to the Northern Plains, recounting the adventures of these brothers personifying the Morning and Evening stars, responsible for slaying primordial monsters, making the world habitable, and doing amazing things on a heroic scale. Diego paints them with mixed ethnic signifiers, including Apache moccasins, Ancestral Pueblo war caps, and the muscular, athletic bodies of Greek vase paintings and comic book superheroes. Flying through space in active poses leaping to the protection of the people, one carries a bow and arrow, and the other a sharp thrusting spear. Around them, the intergalactic fields of Diego’s Kirby Crackle push out against the bulging sides of the olla, while golden luster borders crown its neck and foot. This is a rare form in Diego’s oeuvre, drawing upon Pueblo history in which similar vessels were used for water and purportedly (somewhat larger) ollas measured the fanegas of grain that New Mexico’s colonizers demanded as tribute. He reinvests this customary form with new meaning through his own version of Batman and Robin. Their adventures echo those of Cara’s Jackrabbit and Cottontail, the Chemehuevi hero twins. As Diego asserts, these celestial superheroes are still up there, traveling the cosmos, ready for whatever new adventures and adversaries the future may bring.

Cara’s photograph instead expresses faith in Indigenous peoples’ collective ability to adapt and meet the challenges of the future.

This work visualizes ... seeking passage through these difficult times together, rather than fantasizing about colonizing other worlds to escape our own mess.

When Coyote looks out over his domain and witnesses the changing landscape, he imagines himself to be the king of the night. Coyote is a trickster, a cagey fellow who gets by on wit and cunning. Yet he is also a foolish creature, often ensnared by his own devices and hubris. He is an avatar for the Anthropocene, in which human foibles and overconsumption have ensnared us in the cascading consequences of our own actions. Wrestling with this unfolding reality is a recurrent concern for both Cara and Diego and their complimentary artistic practices, epitomized in two final examples, each pictured at the edge of worlds.

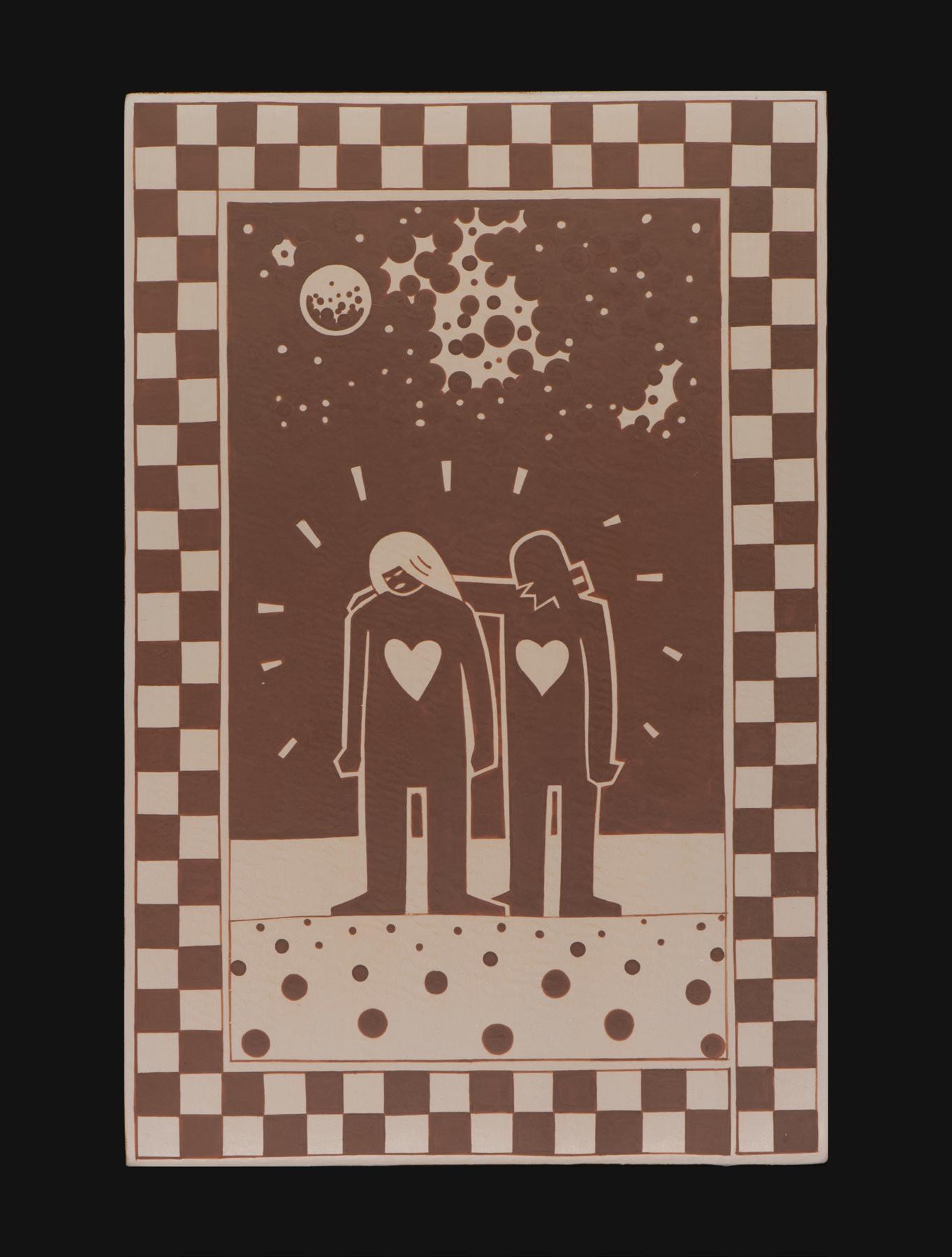

Within the checkered border of Diego’s Two Hearts One Love (2018-2019, page 30), silhouetted lovers stand on the brink, looking down at their earth while the electrical crackle of galaxies and planets churns above them, bearing witness to what the future might hold. Their embrace radiates energy with a Keith Haring directness, while their large feet seem firmly rooted in the layered groundline, perhaps a beach. This work visualizes a partnership rooted in love and reciprocity turning back to the earth and seeking passage through these difficult times together, rather than fantasizing about colonizing other worlds to escape our own mess.

In Gaea (2021, page 19), Diego and Cara’s daughter Crickett rises in a graceful ballet pose on the edge of the California seashore as the sun sets behind her. She wears a feathered corset with abalone shell and willow bark and tule skirt by Mata Fragua, using materials indigenous to California. As the homelands of the Tongva/Gabrielino peoples, the coast is also sacred to the Chemehuevi and their origin accounts of creation by Hutsipamamow (Great Ocean Woman). Seemingly levitating above the landscape and yet tied to the water by the horizontals of her leg and arm, Crickett becomes something more than an individual, invoking archetypes of creation and the Earth Mother. And yet she is also a contemporary Indigenous woman in a particular time and place. Cara shot this series during Covid-19 quarantines in Los Angeles. With the goldenpink tones of the peach sky, the moment of frozen balance, and the evocations of creation, the water surface acquires a different valence here: not the threat of anthropogenic flooding that appears elsewhere in Cara’s work, but rather the lifegiving blessings of origin and renewal.

As Diego’s stratigraphies and Cara’s cultural landscapes indicate, the origins of anthropogenic climate change are rooted in larger dynamics of colonialism, industrialization, assimilationism, and settler economies of the past five centuries. At the same time, they identify deeper substrates of Indigenous trade routes, intertribal relations, customary symbols, and agency in the face of these challenges. Their witness to the Anthropocene is equal parts humorous, self-effacing, elegant, and sincere. Embedded in this work is a note that rarely surfaces in popular discourse around the Anthropocene: hope. In the imaginative leap of their futuristic work, Diego and Cara point out that this epoch is yet becoming, and not fully determined. The histories of survivance, the exemplars of resilience, the cultural memories and enduring connections of Indigenous people offer perspective on the apocalyptic rhetoric of the Anthropocene, as well as to imagine other narratives while not discounting the grave stakes.

For recent debates around the term, see Dino Grandoni, “This word was rejected by geologists. But its already taken over the world,” Washington Post, June 10, 2024, accessed June 19, 2024, https://www.washingtonpost.com/climateenvironment/2024/06/10/anthropocene-epoch-human-climate-impacts/ .

See Kaela Waldstein, Cara Romero: Following the Light, Mountain Mover Media Production (video), 2023, available at https://www.pbs.org/video/cara-romerofollowing-the-light-lk0dbg/ ; and Emily Withnall, “In Conversation with the Sea: Cara Romero’s Photographic Counterpoint to the Dominant Narrative,” El Palacio (Fall 2021).

Garth Clark, Free Spirit: The New Native American Potter (Hertogenbosch, Netherlands: Stedelijk Museum, 2006), 15-16, 105; RoseMary Diaz, “Cochiti Potter: Diego Romero,” First American Art Magazine 9 (Winter 2015): 68.

Diaz, “Cochiti Potter,” 70.

Mark A. Burkholder and Lyman L. Johnson, Colonial Latin America, 9th ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), 84-88.

Diego Romero, personal communication to the author, May 29, 2024.

Isabel T. Kelly and Catherine S. Fowler, “Southern Paiute,” in Handbook of North American Indians, Vol. 11, Great Basin, ed. Warren L. D’Azevedo (Washington D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 1986), 390-392. The Chemehuevi Reservation was originally founded in 1907 (ibid., 389).

Cara Romero, “Artist Talk with Cara Romero in Conversation with Prof. Gregory Levine and Talia Dixon,” UC Berkeley Arts Research Center, April 11, 2023, accessed August 12, 2024, https://arts.berkeley.edu/news/artist-talk-cara-romero.

For example, see PBS News Hour, “As water levels rise, this Alaska town is fleeing to higher ground,” PBS News, November 27, 2019, accessed September 16, 2024, https://www.pbs.org/newshour/show/as-water-levels-rise-this-alaska-town-isfleeing-to-higher-ground ; and Tammy Webber and Martha Irvine, “Tribe seeks to adapt as climate change alters ancestral home,” AP News, November 1, 2022, accessed September 16, 2024, https://apnews.com/article/wildfires-business-newmexico-forests-climate-and-environment-bbe8930abed9107b8d2c35cfe4a573cd.

“Cara Romero,” Desert X, accessed August 12, 2024, https://desertx.org/dx/ archive/jackrabbit-cottontail-spirits-of-the-desert.

Cara Romero, personal communication, May 29, 2024; and “Temiki (Little Death), 2023,” Cara Romero Gallery, accessed August 12, 2024, https://www.cararomero. com/temiki.

Clark, Free Spirit, 104-105. The Mimbres people were part of the larger Mogollon cultural expression in the mountains of Southwestern New Mexico and along the Mogollon Rim in Arizona. Archaeologists identify the “Classic” Mimbres phase as lasting from 1000-1130 CE. For an introduction, see Margaret C. Nelson and Michelle Hegmon, eds., Mimbres Lives and Landscapes (Santa Fe, NM: School for Advanced Research Press, 2010).

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, with Joy Harjo, heather ahtone, and Shana Bushyhead Condill, The Land Carries Our Ancestors: Contemporary Art by Native Americans (Princeton: National Gallery of Art with Princeton University Press, 2023), 118.

For the checkerboard pattern, see Francis Harlow, Matte-Paint Pottery of the Tewa, Keres, and Zuni Pueblos (Santa Fe: Museum of New Mexico, 1973), 137-138; Scott G. Ortman and Joseph Traugott, Painted Reflections: Isomeric Design in Ancestral Pueblo Pottery (Santa Fe, NM: Museum of New Mexico Press, 2018), 31-33, 56; Alex Patterson, Hopi Pottery Symbols (Boulder: Johnson Books, 1994), 244-246; Watson Smith, Kiva Mural Decorations at Awatovi and Kawaika-a (Cambridge, MA: Peabody Museum of American Archaeology and Ethnology, 1952), 132, 225-231; and Edwin L. Wade and Allan Cooke, Canvas of Clay: Seven Centuries of Hopi Ceramic Art (Sedona, AZ: El Otra Lado, 2012), 66.

David Revere McFadden and Ellen Napiura Taubman, eds., Changing Hands: Art without Reservation, Vol. 1 (New York: Merrell Publishers with American Craft Museum, 2003), 123; Diego Romero vs. the End of Art, curated by Tony R. Chavarria, Museum of Indian Arts and Culture, Santa Fe, NM, October 6, 2019-January 2, 2021. Virtual tour available at https://fivedmedia.com/3d-model/ diego-romero-vs-the-end-of-art-miac/skinned/.

Margaret Moore Booker, Southwest Art Defined: An Illustrated Guide (Tucson, AZ: Rio Nuevo Publishers, 2013), 157-158.

Diego Romero vs. the End of Art.

Harry Mendryk, “Evolution of Kirby Krackle,” Jack Kirby Museum and Research Center, September 3, 2011, accessed August 12, 2024, https://kirbymuseum.org/ blogs/simonandkirby/archives/3997.

Diego Romero vs. the End of Art; Diego Romero, personal communication, May 29, 2024.

California Stars/Huivaniūs Pütsiv, curated by Andrea Hanley (Navajo), Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian, Santa Fe, NM, February 11, 2023 to January 6, 2024.

Christopher T. Green has referred to this implied motion as “transmotion” in the tradition of Gerald Vizenor, a concept of motion and active presence that asserts sovereignty and freedom both through space and the imagination. See Green, “Tacit, Visionary, and Natural Motion,” in Larger than Memory: Contemporary Art from Indigenous North America (Phoenix: Heard Museum, 2020), 22-27.

See Indigenous Futurisms: Transcending Past/Present/Future (Santa Fe: IAIA Museum of Contemporary Native Arts, 2020).

See Kevin M. Strait and Kinshasha Holman Conwill, eds., Afrofuturism: A History of Black Futures (Washington, D.C.: National Museum of African American History and Culture and Smithsonian Books, 2023).

Cara Romero, personal communication to the author, September 10, 2024.

Will Riding In, “Work in Progress with George Alexander,” Southwest Contemporary (Oct. 27, 2023).

Examples and variant stories of Masewa and Oyoyewa in ethnographic accounts can be found in Ruth Benedict, Tales of the Cochiti Indians, Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 98 (Washington, D.C.: US Government Printing Office, 1931).

Booker, Southwest Art Defined, 103; Diego Romero, personal communication to the author, September 10, 2024.

“Hermosa, 2021,” Cara Romero Gallery, accessed August 12, 2024, https:// cararomero.squarespace.com/hermosa; Withnall, “In Conversation with the Sea.”

“Gaea, 2021,” Cara Romero Gallery, accessed August 12, 2024, https://www. cararomero.com/gaea.

Withnall, “In Conversation with the Sea.”

Gods, Demi-Gods, and Heros (2021) earthenware with slip and luster, 12" diameter x 9.5" height.

On loan from the Collection of Mark Boardman and Olga Vidiaikina, Lubbock, Texas.

credit: Matthew Mishevski.

King of the Night (2023)

earthenware

On

Masewa and Oyoyewa (2024) earthenware with slip and luster, 12.5" diameter x 15" height. On loan from the Collection of Mark Boardman and Olga Vidiaikina, Lubbock, Texas. Image credit: Cara Romero Gallery.

Jackrabbit and Cottontail (2017)

archival pigment print, 38 x 50 inches.

Loan courtesy of Cara Romero Gallery, Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Shameless (2017)

archival pigment print, 30 x 44 inches.

Loan courtesy of Cara Romero Gallery, Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Ty (2017)

archival pigment print, 38 x 41 inches.

Loan courtesy of Cara Romero Gallery, Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Gaea (2021)

archival pigment print, 51 x 41 inches.

Loan courtesy of Cara Romero Gallery, Santa Fe, New Mexico.

The Zenith (2022)

archival pigment print, 42 x 47 inches.

Loan courtesy of Cara Romero Gallery, Santa Fe, New Mexico.

NDN Summer (2023)

archival pigment print, 55 x 41 inches.

Loan courtesy of Cara Romero Gallery, Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Temiki (Little Death) (2023)

archival pigment print, 46 x 43 inches.

Loan courtesy of Cara Romero Gallery, Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Alika No. 1 (2024)

archival pigment print, 60 x 40 inches.

On loan from the Collection of Mark Boardman and Olga Vidiaikina, Lubbock, Texas.

Agents of Oppression (1994)

Cochiti earthenware with slip, 12" diameter x 6" height.

On loan from the Collection of Mark Boardman and Olga Vidiaikina, Lubbock, Texas.

Dead Chongo (1994)

Cochiti earthenware with slip, 8.5 x 4 inches

On loan from the Collection of Mark Boardman and Olga Vidiaikina, Lubbock, Texas.

American Highway (ca. 2004-2005)

earthenware, slip, luster, 9" diameter x 3" height.

On loan from the Collection of Mark Boardman and Olga Vidiaikina, Lubbock, Texas.

Man Scape 2018 (2018)

earthenware with slip, 6.5 x 10 x 0.5 inches.

On loan from the Collection of Mark Boardman and Olga Vidiaikina, Lubbock, Texas.

Uhura (ca.2018)

earthenware with slip, 6.25 x 5.25 x 0.5 inches.

On loan from the Collection of Mark Boardman and Olga Vidiaikina, Lubbock, Texas.

Two Hearts: One Love (2018-2019)

earthenware with slip, 10 x 6.5 x 0.5 inches.

On loan from the Collection of Mark Boardman and Olga Vidiaikina, Lubbock, Texas. .

Gods, Demi-Gods, and Heros (2021)

earthenware with slip and luster, 12" diameter x 9.5" height.

On loan from the Collection of Mark Boardman and Olga Vidiaikina, Lubbock, Texas.

Cosmic Parrots (2023)

earthenware with slip, 14" diameter x 3.5" height.

On loan from the Collection of Mark Boardman and Olga Vidiaikina, Lubbock, Texas.

King of the Night (2023)

earthenware with slip, 14.5" diameter x 5" height.

On loan from the Collection of Mark Boardman and Olga Vidiaikina, Lubbock, Texas.

In Loving Memory of Otellie Loloma, Traditional Pottery Instructor, Institute of American Indian Art (2024)

earthenware with slip and luster, 14" diameter x 5" height.

On loan from the Collection of Mark Boardman and Olga Vidiaikina, Lubbock, Texas.

Masewa and Oyoyewa (2024)

earthenware with slip and luster, 12.5" diameter x 15" height.

On loan from the Collection of Mark Boardman and Olga Vidiaikina, Lubbock, Texas.