Engineered for the most extreme conditions, the new Swiftcurrent® Expeditions deliver unmatched durability, features and comfort. Advanced materials and innovative patterning reduce bulk, minimize seam stress and enhance maneuverability. They move effortlessly in and out of the water, efficiently carry gear and can easily transition from chest-high to waist-high. Plus, their durable water repellent finish is made without intentionally added PFAS.

NEW LIGHT-LINE AND DRY FLY SPECIFIC RODS FROM WINSTON.

THE INCREDIBLE NEW PURE 2 SERIES utilizes new NanoParticle graphite materials, making these rods delicate and lively. From fishing large tailwaters, to technical spring creeks, and small streams, these light-line presentation rods give anglers the upper hand by flexing evenly, recovering quickly, and maintaining the iconic smooth and balanced Winston Feel.

Discover perfected presentation at your local Winston dealer and at winstonrods.com

Chair of the Board

Terry Hyman, Washington, D.C.

President/Chief Executive Officer

Chris Wood, Washington, D.C.

Secretary

Linda Rosenberg Ach, san FranCisCo, CaliF

Treasurer

Larry Garlick, Palo alto, CaliF.

Chair of National Leadership Council

Rich Thomas, starlight, Pa

Secretary of the National Leadership Council

Paul McKay, Wheeling, W.Va

Trustees

Stewart Alsop, sante Fe, n.M.

Tony Brookfield, Park City, Utah

John Burns, neeDhaM, Mass

Amy Cordalis, ashlanD, ore.

Josh Crumpton, WiMberley, texas

Mac Cunningham, basalt, Colo

R. Joseph De Briyn, los angeles, CaliF

Paul Doscher, Weare, n h

Larry Finch, Wilson, Wyo

Susan Geer, gilbert, ariz

Peter Grua, boston, Mass

Chris Hill, Washington, D.C./haines, alaska

Gregory McCrickard, toWson, MD

Phoebe Muzzy, hoUston, texas

H. Stewart Parker, ChaPel hill, n.C.

Al Perkinson, neW sMyrna beaCh, Fla

Greg Placone, greenVille, s.C.

Candice Price, kansas City, Mo

Donald (Dwight) Scott, neW york, n y

Kathy Scott, norriDgeWoCk, Me

Judi Sittler, state College, Pa

Joseph Swedish, silVerthorne, Colo

Blain Tomlinson, long beaCh, CaliF

Terry Turner, glaDstone, ore

Leslie Weldon, benD, ore

Jeff Witten, ColUMbia, Mo./elkins, W.Va

Geofrey Wyatt, santa barbara, CaliF

Chair Rich Thomas Secretary

Paul McKay

arizona, Tom Goodwin

arkansas, Ron Blackwelder

CaliFornia, Trevor Fagerskog

ColoraDo, Greg Hardy

ConneCtiCUt, Beth Peterson

georgia, Steve Westmoreland

iDaho, M.E. Sorci

illinois, Hans Hintzen

ioWa, Tom Rhoads

Maine, Tammy Packie

MassaChUsetts, Bill Pastuszek

MiChigan, Greg Walz

MiD-atlantiC, Noel Gollehon

Minnesota, Randy Brock

Montana, Mark Peterson

neW haMPshire, John Bunker

neW Jersey, Peter Tovar

neW MexiCo, Jeff Arterburn

neW york, Jeff Plackis

north Carolina, Mike Mihalas

ohio, Matt Misicka

oklahoMa, Levi Poe

oregon, Peter Gray

ozark (ks/Mo) Jeff Holzem

PennsylVania, Russ Collins

soUth Carolina, Mike Waddell

tennessee, Mark Spangler

texas, Joe Filer

Utah, Eric Luna

VerMont, Travis Dezotell

Virginia, Tom Benzing

Washington, Andrew Kenefick

West Virginia, Paul McKay

WisConsin, Scott Allen

WyoMing, Jim Hissong

State Council Chairs

arizona, Alan Davis

arkansas, Michael Wingo

CaliFornia, Trevor Fagerskog

ColoraDo, Barbara Luneau

ConneCtiCUt, Richard Mette

georgia, Rodney Tumlin iDaho, Tyler Hallquist

illinois, Dan Postelnick

ioWa, Dave Klemme kentUCky, Mike Lubeach

Coldwater Conservation Fund Board of Directors 2025

President

Jeffrey Morgan, neW york, n y

Executive Committee

Joseph Anscher, long beaCh, n y

Philip Belling, neWPort beaCh, CaliF

Stephan Kiratsous, neW york, n y

Stephen Moss, larChMont, n y

Directors

Peter and Lisa Baichtal, saCraMento, CaliF

Bill Bell, atlanta, ga

Daniel Blackley, salt lake City, Utah

Douglas Bland, ChesaPeake City, MD.

Stephen Bridgman, WestFielD, n.J.

Mark Carlquist, los gatos, CaliF

Gregory Case, PhilaDelPhia, Pa

Benjamin Clauss, greenVille, s.C.

Bonnie Cohen, Washington, D.C.

James Connelly, neWPort beaCh, CaliF

Jeremy Croucher, oVerlanD Park, kan

Matthew Dumas, Darien, Conn

Rick Elefant and Diana Jacobs, berkeley, CaliF

Glenn Erikson, glorieta, nM

Renee Faltings, ketChUM, iDaho

John Fraser, norWalk, Conn.

Matthew Fremont-Smith, neW york, n y

Bruce Gottlieb, brooklyn, n y

John Griffin, brooklyn, n y

Robert Halmi, Jr., neW york, n y

William Heth, eaU Claire, Wis

Kent and Theresa Heyborne, DenVer, Colo

Kent Hoffman, oklahoMa City, okla

Frank Holleman, greenVille, s.C.

Braden Hopkins, Park City Utah

James Jackson, hoUston, texas

Tony James, neW york, n y

Jeffrey Johnsrud, neWPort beaCh, Cali.

Jakobus Jordaan, san FranCisCo, CaliF

Matthew Kane, boUlDer, Colo

James Kelley, atlanta, ga

Peter Kellogg, neW york, n y

Andrew Kenefick seattle, Wash

Steven King, Wayzata, Minn

Lee Lewis, PhilaDelPhia, Pa

Cargill MacMillan, III, boUlDer, Colo

Ivan & Donna Marcotte, asheVille, n.C.

Michael Maroni, bainbriDge islanD, Wash

Jeffrey Marshall, sCottsDale, ariz

Tim Martin, henDerson, neV.

Heide Mason, yorktoWn heights, n.y.

Paul McCreadie, ann arbor, MiCh

Gregory McCrickard, toWson, MD

J. Thomas McMurray, JaCkson, Wyo

Daniel Miller, neW york, n y

Robert & Teresa Oden, Jr., hanoVer, n h

Maine, Matt Streeter

MassaChUsetts, C. Josh Rownd

MiChigan, Gabe Schneider

MiD-atlantiC, Randy Dwyer

Minnesota, Brent Notbohm

Montana, Lyle Courtnage

neW haMPshire, Michael Croteau

neW Jersey, Marsha Benovengo

neW MexiCo, Marc Space

neW york, Cal Curtice

north Carolina, Brian Esque

ohio, Scott Saluga

oklahoMa, Bridget Kirk

oregon, Mark Rogers

ozark (ks/Mo) Bill Lamberson

PennsylVania, Lenny Lichvar

soUth Carolina, Tom Theus

tenessee, Ryan Turgeon

texas, Chris Johnson

Utah, Scott Antonetti

VerMont, Jared Carpenter

Virginia, Jim Wilson

Washington, Pat Hesselgesser

West Virginia, Eugene Thorn

WisConsin, Myk Hranicka

WyoMing, Kathy Buchner

Kenneth Olivier, sCottsDale, ariz

H. Stewart Parker, ChaPel hill, n.C.

Anne Pendergast, big horn, Wyo

Michael Polemis, olD ChathaM, n y

Adam Raleigh, neW york, n.y.

Margaret Reckling, hoUston, tx

John Redpath, aUstin, texas

Brian Regan, neW Canaan, Conn

Michael Rench, CinCinnati, ohio

Steven Ryan, Wilson, Wyo

Leigh Seippel, neW york, n y

Paul Skydell, bath, Maine

Gary Smith, st loUis, Mo

Robert Strawbridge, III, Wilson, Wyo

Paul & Sandy Strong, lakeMont, ga

Daniel Seymour, staMForD, Conn

Margeret Taylor, sheriDan, Wyo

Robert Teufel, eMMaUs, Pa.

Andrew Tucker, larChMont, n y

Andrew Tucker, Vero beaCh, Fla

Deacon Turner, DenVer, Colo

Jeff Walters, sCottsDale, ariz

Maud and Jeff Welles, neW york, n y

Tyler Wick, boston, Mass

Geofrey & Laura Wyatt, santa barbara, CaliF

Daniel Zabrowski, oro Valley, ariz

The Gulf Collection is a master of the art of adaptation. Our softest weather resistant layer, it provides comfortable protection from sun, wind, rain and boat spray, when you need it. And when you don’t, it packs down effortlessly for easy stowing, so you can always have it on hand if (and when)

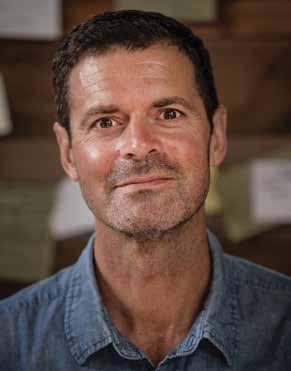

[ Chris Wood ]

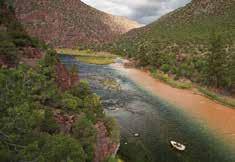

Not long ago, I awoke to the news of a late-night amendment that passed through a committee of the House of Representatives to allow for the sale or transfer of thousands of acres of public land in Nevada and Utah.

Like cicadas emerging from the earth every 15 or so years, these harebrained ideas to sell or transfer public lands arise. Like cicadas, their proponents create a mess before eventually crawling back into the earth.

I discovered the wonder of America’s public lands when I was 25, having spent several years managing an ice-cream factory in New Jersey, and coaching at Saint Peter’s Prep in Jersey City, N.J.

After we won the state championship that year I decided to “look for America.” Setting out in my used Mercury Lynx with my beloved hound, Gus, we travelled fewer than 200 miles per day as we made our way west to California, travelling blue-line roads and camping on National Forest, Bureau of Land Management, or National Park Service land.

Public lands are the backyard of the little guy. Places where a kid from New Jersey can camp his way across America with his dog. Places where families who cannot afford to fly to fancy resorts can be together and find solace in nature. For most of us, public lands are the only lands we will ever “own.” If America sells or transfers our public lands to the highest bidder, these places will become the playground of the wealthy.

Public lands provide an abundance of multiple uses that help local communities and support the national interest. Timber, oil and gas, coal, forage for livestock, important archaeological sites, recreational access, are just a few of the many benefits that flow from our public lands.

When it comes to trout and salmon, the value of public lands—especially public lands without roads—cannot be overstated. Consider:

• Over 50 percent of blue-ribbon trout streams in America flow across National Forests.

• Public lands provide access and opportunity to 70 million American hunters and anglers.

• 70 percent of remaining habitat for all native trout in the West are found on public lands.

In recent years, the push has been to “return” public lands to the states. This is a fallacious idea. At no time did Western public lands belong to the states. They were acquired through treaty, conquest or purchase by the federal government acting on behalf of all the citizens of the United States.

It is also a bad idea for keeping public lands public. Western states have historically sold their public lands—Utah has sold 55 percent of its state trust lands; Nevada 99 percent; and Colorado 38 percent. We should expect nothing different if public lands are managed by the states.

Public lands are the anvil upon which the character of our nation was hammered as we made our way west. They demonstrate we are not a desperate nation; having to scratch and claw every ounce of gold, suck every gallon of oil or turn every tree into a piece of lumber.

Public lands demonstrate the inherent optimism of America. They affirm that we believe in passing on a healthier land and water legacy to our kids than the one we inherited from our parents.

To intone Macbeth, Americans hear so much “sound and fury” from Washington, D.C., instinctively we become tone deaf to the noise. Cynical people are counting on our passivity. Don’t let them win. Act today to keep public lands in public hands.

EDITOR

Kirk Deeter

DEPUTY EDITOR

Samantha Carmichael

EDITOR-AT-LARGE

Erin Block

Trout Unlimited 1700 N Moore Street Suite 2005

Arlington, VA 22209-2793

Ph: (800) 834-2419

trout@tu.org www.tu.org

DESIGN

grayHouse design

jim@grayhousedesign.com

DISPLAY ADVERTISING

Nick Halle nick.halle@tu.org (703) 284-9425

TROUT UNLIMITED’S MISSION:

TROUT published four times a year in January, April, July and October by Trout Unlimited as a service to its members. Annual individual member ship for U.S. residents is $35 Join or renew online at www.tu.org.

TU does occasionally make street addresses available to like-minded organizations. Please contact us at 1-800-834-2419, trout@tu.org or PO Box 98166, Washington, DC 20090 if you would like your name withheld, would like to change your address, renew your membership or make a donation.

Postmaster send address changes to:

TROUT

Trout Unlimited 1700 N Moore Street Suite 2005 Arlington, VA 22209-2793

[ Kirk Deeter ]

Asking me (the editor) about favorite stories I’ve run in TROUT, is akin to asking a parent to talk about their favorite children. TROUT runs tons of amazing stories from the best writers connected to fishing and conservation in the entire world, and I’m extremely proud of the vast body of work I’ve led as editor, now 52 issues and counting. That said, I’d encourage you to take an extra-meaningful gander at “Somewhere South of Fairplay,” Tom Reed’s contribution to this issue. And also think hard on the rest of the stories contained in these pages, because it’s no coincidence that we made the theme of this issue of TROUT “Public Lands.” Every few years, it seems, the pavement-dwellers propose divesting of public lands, and each time, TU CEO Chris Wood and many others eloquently show how public lands are the very fabric of what we all care about—and the absolute short-sighted, tragic folly that would result if we lost public access to the land and waterways on which we hike, fish and recreate. As someone who has made a career of going all around the world and writing stories about fishing for trout, I can tell you that I am always—always—left with the immense pride of being an American, because no matter where I go, I inevitably feel the envy of people who are absolutely awe-struck by the notion of what we Americans can share and experience by virtue of access to public lands. If you genuinely care about access and fishing, there should be a clear line in the sand. Draw it… and defend it.

F REE-RANGE CERTIFIED.

A destination isn’t measured in miles, but in moments.

It’s the freedom to roam, to wade, to drift into something bigger.

No ticket required, just the will to wander.

BY T.J. DEZOTELL

There are rivers you visit and rivers you experience. The Nulhegan River, which quietly winds through Vermont’s Northeast Kingdom, is undeniably the latter. As a fly-fishing guide and the president of our local TU chapter, I’ve witnessed firsthand the subtle beauty and wild character of this river. To those who’ve ventured deep into the Nulhegan’s remote stretches, it remains one of the finest wild brook trout fisheries in New England.

A River Rich with History Long before fly rods and waders, the Abenaki people roamed the banks of the Nulhegan. The name “Nulhegan” itself originates from the Abenaki language, roughly translating to “river where the fish dwell.” This nod to abundant life was no exaggeration; the river historically teemed with brook trout, Atlantic salmon

and other native species. For the Abenaki, the river represented sustenance, spirituality and survival. As modern stewards, understanding this heritage enriches our connection to the water.

European settlers arrived in the late 18th century, attracted by the fertile forests and wildlife. Logging then predominated, and although it brought economic prosperity, it also disrupted the delicate ecological balance of the river. Decades of conservation efforts have begun to heal these wounds, and today, the Nulhegan once again thrives, its waters clean, clear and vibrant with native fish.

The Nulhegan Division of the Silvio O. Conte Wildlife Refuge

One of the greatest conservation success stories in the Northeast Kingdom is the establishment of the Nulhegan Basin Division of the Silvio O. Conte National Fish and Wildlife Refuge. Spanning over

26,000 acres, this refuge represents a profound commitment to land and water protection, creating one of the most significant contiguous forest blocks in the Northeast.

Throughout Conte’s political career, he was a champion for the environment, and the refuge embodies his vision of landscape-scale conservation. The Nulhegan Division protects key headwaters that feed the river, safeguarding critical brook trout spawning habitat. As a result, the waters here remain pristine, providing a haven not only for fish but for rare species like Canada lynx, moose, pine marten, boreal birds and an incredible diversity of amphibians.

Wild Brook Trout:

Jewels of the Northeast Kingdom

Wild brook trout (Vermont’s state fish) dominate the river, providing challenging, spirited action. Each season, my

clients marvel at the brookies’ brilliant colors—fiery reds, striking blues and vibrant greens. Unlike stocked trout, wild brook trout possess an undeniable toughness, shaped by survival in a dynamic wilderness environment. Landing one requires patience, skill and an appreciation for the subtleties of the sport. They remind us why we fish: to experience nature authentically.

Fishing the remote stretches of the Nulhegan is no easy task. While a few accessible spots provide entry points, the majority of the river snakes through remote, densely wooded areas. Trails are scarce, roads even scarcer. Here lies both challenge and opportunity; those willing to explore are rewarded with solitude and untouched waters.

In our fishing expeditions into its headwaters, we pack personal portable rafts into an extremely remote put-in, where we then work through gentle riffles, tight bends and dense vegetation, accessing pools and runs seldom visited by others. Rafts not only make remote fishing possible, but help us fish more sustainably, minimizing our footprint in sensitive areas.

Fishing the Nulhegan isn’t just about trout—it’s a full wilderness immersion. Moose emerge silently from dense forest cover, a doe and her fawn come down to the bank for a drink, and ospreys soar overhead. Bird enthusiasts find paradise here, too. Boreal species like spruce grouse, blackbacked woodpeckers, grey jays and boreal chickadees inhabit the refuge. Hearing their distinct calls while casting dry flies on a tranquil morning amplifies the sense of remote wilderness.

of TU actively supports conservation projects along the Nulhegan, partnering with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Vermont Fish & Wildlife, Memphremagog Watershed Association and many other organizations. Projects like riparian buffer restoration, culvert replacement, habitat chop-and-drops and fish passage improvements enhance habitat and ensure brook trout populations remain robust.

Planning a trip to fish the Nulhegan requires preparation. Given the remote nature of the river, it’s wise to hire a guide or join a guided trip to ensure total enjoyment of the experience.

Essential gear includes 3- to 5-weight fly rods, floating line and classic brook trout patterns like Elk Hair Caddis, the Royal Wulff and bead-head nymphs. Don’t overlook terrestrial patterns during summer months. Always pack for changing weather—rain gear, layers and bug spray are crucial.

Rafts not only make remote fishing possible, but help us fish more sustainably, minimizing our footprint in sensitive areas.

As anglers, we carry the responsibility of stewardship. The David & Francis Smith Northeast Kingdom Chapter

Every angler who visits carries the responsibility of protecting this exceptional place. By practicing catch-and-release, minimizing impact and supporting local conservation, we ensure future generations will experience the Nulhegan’s magic.

Note: Vermont Senator Peter Welch recently introduced legislation to proceed with a study of the Nulhegan River and Paul Stream and their tributaries in order to designate them as National Wild & Scenic Rivers via Congressional recommendation.

T.J. Dezotell is a northern Vermont fly-fishing guide, photographer and conservationist based in Island Pond.

BY SAM DAVIDSON

It’s hard to exaggerate the importance of public lands for fishing and hunting in America. In the West, the vast majority of good stream and upland habitat we have left is found on lands managed by the USDA Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management (BLM). Most of these lands are open for development of mineral, energy and timber resources.

Such development can compromise aquatic, riparian and upland habitat if not done responsibly, with careful consideration of fish and wildlife needs. And some places are so important as strongholds for fish and game that protecting their habitat values should be prioritized.

One such place is the Sáttítla Highlands, a rugged landscape not far from Mt. Shasta in northern California. This region, the remnants of a geologic formation called a shield volcano—the largest in North America—is part of three national for-

ests. Ironically, the Sáttítla Highlands have very little surface water. Yet this region is vital for a fistful of famous trout streams, including California’s largest spring-fed stream system: the Fall River.

That’s because the porous landscape of the Sáttítla Highlands absorbs and filters significant amounts of rain and snowmelt and collects it into a vast aquifer, which some studies suggest contains as much water as California’s 200 largest surface reservoirs combined.

And wow, this water. It’s so cold and clean that you can drink it straight from

the springs where much of it emerges from the ground—60 miles or more from the crest of the Highlands—at the head of the Fall River Valley. This spring system is the sole source of the Fall River. Thanks to its unique hydrology and water quality, the Fall River is incredibly fecund. A distinctive population of native rainbow trout has evolved here which spawns in two different seasons and churns out steelhead-size fish. Even in periods of prolonged drought, the Fall River springs deliver an impressive volume of water to the Fall, and to the Pit and Sacramento rivers downstream. Legendary trout streams, all.

The aquifer under the Sáttítla Highlands—and the trout and fishing experiences that depend on it— are extraordinary. That’s why Trout Unlimited worked closely with the Pit

Expand the possibilities and enter a new era of ne-tuned shability with the latest progressions in freshwater multipurpose y lines from RIO – new Gold XP, new Gold MAX and Classic Gold STANDARD.

Continued from page 12 River Tribe and other conservation partners over the past 18 months to permanently protect 224,000 acres of this region of public lands as a national monument.

The Sáttítla Highlands are the homeland of the 11 bands of the Pit River Tribe. The Tribe has been fighting for decades to protect this remarkable landscape from proposed development projects. The Sáttítla Highlands have extraordinary cultural, geologic, hydrologic, recreational and water values and in every way deserve national monument status.

President Biden acknowledged this in January of this year, when he honored the long struggle of the Pit River Tribe by establishing the Sáttítla Highlands National Monument.

Over the last century, the creation of national monuments and other protective designations for deserv-

ing areas of public lands has helped create a bulwark against habitat loss and sustain some of our best hunting and fishing opportunities. Examples include the Hoover Wilderness in California, the Rio Grande del Norte National Monument in New Mexico, the Copper-Salmon Wilderness in Oregon and Browns Canyon National Monument in Colorado.

Trout Unlimited has strongly supported such designations for public lands and waters with high habitat and sporting values. In fact, Trout Unlimited played a lead role in establishing or expanding all special designations in the preceding paragraph.

Since 1904, 18 presidents—nine Republican and nine Democrat, including President Trump—have used their authority under the Antiquities Act to establish new national monuments.

Productive habitat is critical for

species viability and sporting success. Without large areas of undisturbed, healthy waters and lands, our fish and game species start to go away—as do our fishing and hunting opportunities. Literally. We have lost a lot of wild country over the past 200 years, and many fish and game populations, tags and lengths of seasons reflect this loss.

Of the 28 trout species and subspecies native to the Lower 48, for example, three are now extinct and six are listed as threatened or endangered. More than half now occupy less than 25 percent of their historic range.

The Sáttítla Highlands are a great monument if, to paraphrase Benjamin Franklin, we can keep it. Conservation is a long game, and the game never really ends. For anglers and hunters, protecting habitat and sporting opportunity is just part of the deal—now more than ever.

The Sáttítla Highlands have extraordinary cultural, geologic, hydrologic, recreational and water values and in every way deserve national monument status.

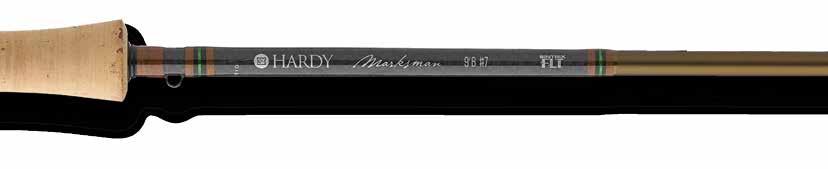

craft, the demands we place on little more than a couple of ounces of carbon fibre are considerable. We expect featherlight touch and feel in close, backbone enough to drive a long, fast and accurate loop but with the durability to fight and land that fish of the day, season or even a lifetime. Designed in Alnwick England during Hardy's 150th year our new flagship rod "The Marksman" has been developed and tested with this incredibly varied challenge in mind. A strong, yet considerably lighter blank has been matched with an all new reel seat that further accentuates the weight reduction and promotes an almost weightless in hand feel. Fitted with titanium guides and dressed in a subtle non-flash golden olive, its understated looks hide a capability that needs to be experienced to be understood.

BY COREY FISHER

Controversy over public lands is nothing new. From the Sagebrush Rebellion in the 1970s, to state legislatures considering cookie-cutter legislation in the mid-2010s demanding federal public lands be transferred to states, to recent litigation questioning the constitutionality of public lands, there is a long history of proposals to sell, transfer or otherwise dispose of lands that belong to all Americans.

Most recently, Congress is considering the sale of federally managed public lands as one way to raise revenue to pay for tax cuts. At the same time, the Department of the Interior is evaluating public lands that may be offloaded to address housing shortages. Regardless of the current justification or public relations pitch, schemes for large scale sell-off of public lands are shortsighted and unpopular among hunters and anglers across the political spectrum.

Thankfully, forward-thinking lawmakers have introduced legislation to limit the disposal of public lands that “can be accessed by public road, public trail, public waterway, public easement, or public right-of-way.”

Championed by Representatives Ryan Zinke (R-MT) and Gabe Vasquez (D-NM), the Public Lands in Public Hands Act (H.R. 718) is bipartisan legislation that would restrict the sale or transfer of most public lands managed by the Department of the Interior and the U.S. Forest Service except under specific conditions and where required under previous laws.

Public lands are vital for wild and native trout. Nearly 70 percent of the remaining habitat for native trout in the Intermountain West and more than 50 percent of the nation’s blueribbon trout streams are found on public lands. Public lands are also the backbone of an outdoor recreation economy that generates $1.2 trillion in economic output and supports five million jobs.

Moreover, the 640 million acres of public lands in our country also support a multitude of uses that produce

goods and resources society needs, as well as ecosystem benefits for communities—national forests alone provide drinking water for over 60 million people!

Regardless of the current justification or public relations pitch, schemes for large scale sell-off of public lands are shortsighted and unpopular among hunters and anglers across the political spectrum.

The value of public lands isn’t just about economic output and statistics, however. Arguably, the greatest value of our public lands is personal. These are the places where millions of kids learned to fish. It’s where we go to ‘get lost’ and find a piece of ourselves. We all have our own fishing spots, hunting honey holes and places of respite that we like to think of as our own, and that—for now—belong to us all. These are not just places on a map, these are places in our hearts. The Public Lands in Public Hands Act will help keep them there, for all Americans. Scan the QR code to act in support of this important legislation.

By car:

90 minutes from Philadelphia

2 hours from New York City

~ 4,000 Gated Acres, Surrounded by 62,000-Acres of State Forests, to be Owned Collectively by Never More Than 73 Homeowners

3 & 12 Acre Homesites ra nging from $595,000 - $975,000

Onsite Property Manager

Three-Mile Spring-Fed Stream

Waterfalls, Bald Eagles

Fitness Center, Pool, Tennis

9 Luxury Suites, Gun Club

Southern Expansive Views

2,500+ Acres to be Conserved

BY MAGGIE HEUMANN, TU DIRECTOR OF ENGAGEMENT PARTNERSHIPS

I’ve known I wanted to be an entomologist since I was three years old. Bugs never scared me—they fascinated me. My first “real” data collection gig was as “Junior Caddisfly” for the Fort Payne High School FFA Water Monitoring Team. I was maybe seven or eight, tagging along thanks to Mr. Blanton, an FFA sponsor with a serious fly-fishing habit.

When I started looking at colleges around 2004, I was surprised to find that not every school had an entomology program—and some even called it “Pest Management,” which definitely wasn’t the vibe I was going for. I just wanted to study insects, teach others about them and fill every Cornell drawer and vial I could get my hands on. Eventually, I followed family tradition to Auburn University, where I technically majored in Poultry Science but took far more entomology courses than I needed to for my “minor.”

After graduation, the job market was still reeling from the housing crisis. I headed west and pursued a Master’s in Entomology, assuming—naively—that all the public lands I loved had full-time entomologists doing regular inventories and surveys. I thought we must surely be tracking the biodiversity of Wild & Scenic Rivers, national forests and parks. What I found instead was a huge opportunity. I had learned about ATBIs (All Taxa Biodiversity Inventories)—specifically the ones done in Great Smoky Mountains National Park and the rich diversity waiting to be discovered on our public lands. I just couldn’t figure out how to get more people to care about this.

During that time, I started working part-time (then full-time) in a fly shop, which turned out to be the start of a long, winding road that led me to Trout Unlimited. Somewhere along the way, I stumbled across a group of grad students from the University of Montana asking the same questions I was: Why do we run annual fish surveys but skip the bugs? Where have all the salmonflies gone? Could communities be trained to collect

real data and help fill in the gaps and answer questions?

Enter The Salmonfly Project. This grassroots initiative is bringing citizen science to the rivers, empowering volunteers to collect and identify aquatic macroinvertebrates—those stoneflies, mayflies and caddisflies that hold up the base of the food web. These insects are more than fish food. They’re indicators of stream health and red flags when things go wrong.

The truth is, aquatic insect populations are in trouble. Habitat loss, development, pollution and a rapidly changing climate are reshaping their life cycles and shrinking their range. The Salmonfly Project is flipping that challenge into a solution—by putting tools in the hands of anglers, students, conservationists and anyone who cares about their local stream.

Volunteers get trained to sample bugs, record environmental data like temperature and fine sediment, and upload photos to platforms like iNaturalist. That info gets used to track trends and inform

restoration work. Even small observations matter: a photo with a GPS tag, a shift in emergence timing, a new stonefly in an unexpected place. All of it helps scientists see a bigger picture.

What I love most about The Salmonfly Project is that it’s deeply personal and deeply scientific all at once. You don’t need a degree—you just need curiosity and a little time on the water. And in return, you get a better understanding of your home watershed, a new appreciation for the little critters that make trout fishing possible, and a chance to be part of something bigger. When things go awry in your watershed, you now have a dataset to use as leverage.

We’re in an age where conservation can’t be left to the professionals alone. Citizen science is how we close the gaps. It’s how we connect people to places and remind them that the river’s health doesn’t begin or end with fish—it starts with the bugs. That’s what flies are imitating, after all.

As I like to say, if you care about trout, you better care about what trout eat. And if you care about that, you’re already halfway to being a bug nerd like me.

Want to help care for the bugs, too? Join me and The Salmonfly Project by sharing your observations or participating in their community surveys. Your time on the water can help fuel better conservation and restoration decisions across the West. www.salmonflyproject. org/. Let’s get some boots in the water—and eyes on the bugs!

BY BEN MOYER, CRTU PRESIDENT

Trout Unlimited’s Chestnut Ridge Chapter (CRTU) in southwestern Pennsylvania got an unexpected financial boost last fall. When the PA Dept. of Environmental Protection (DEP) cited a Marcellus shale gas extraction firm for violations, a court ordered the firm to donate a specified large sum to a credible conservation organization in the region. The firm found CRTU through the chapter website and mailed a check to the treasurer earmarked for CRTU’s Glade Run Project.

Glade Run is a mountain stream with a tragic history that sparked CRTU’s founding in 1995. From its inception, the chapter committed to Glade’s restoration and has upheld that pledge through three decades.

Glade Run begins in a high wetland, then plunges through a remote gorge in Chestnut Ridge, the westernmost flank of the Allegheny Mountains, flowing eight miles over falls and through boulder-studded pools within the 16,000 wild acres of State Game Land. Downstream, it joins Dunbar Creek and the Youghiogheny River.

Once known for its native brook trout, Glade Run suffered the fate of countless Appalachian streams. Surface mining for coal from the 1940s through the early 1980s unleashed acid that wiped out trout and the food chain that supported them.

“We considered it unacceptable that such a beautiful stream, flowing through public land, could not support the native wild trout of these mountains,” said Eugene Gordon of Mt. Braddock, Pa., who first envisioned a Trout Unlimited chapter to nurture Glade Run’s recovery.

Early on, the chapter collaborated with environmental scientists from California University of PA to establish baseline data. Surveys confirmed the absence of brook trout and found only insects tolerant of acidic pollution.

Beginning in 1998, CRTU experimented with limestone sand dosing,

a low-tech approach to acid mine drainage treatment well suited to the Glade Run watershed. Members sought technical help from the Western Pennsylvania Coalition for Abandoned Mine Reclamation and calculated the amount of limestone sand needed to achieve short-term improvements. They worked with the Pennsylvania Game Commission, which owned the land, to improve

truck access on old logging roads and placed loads of limestone sand on the streambank in three locations, where high-flow events could wash the fine particles into the stream to dissolve and raise alkalinity and pH.

Limestone dosing achieved marked improvements in Glade Run’s chemistry, and CRTU placed hatchery-raised brook trout in cages in Glade Run. The trout survived, and CRTU applied to DEP and won a $300,000 grant to construct a passive acid mine drainage treatment system on Glade Run’s headwaters, outside the state land boundary.

Contractors finished construction in 2002. The system worked well but members continued to find more acidic discharges from the poorly reclaimed mine site. To address untreated dis-

Once known for its native brook trout, Glade Run suffered the fate of countless Appalachian streams. Surface mining for coal from the 1940s through the early 1980s unleashed acid that wiped out trout and the food chain that supported them.

charges, the chapter began twice-yearly treatments with limestone sand purchased from approved quarries. CRTU has continued this schedule for 23 years, spending as much as $15,000 per year to place limestone sand at three treatment sites in the Glade Run basin. The chapter raised this money at its annual banquet, and won grants from the Pennsylvania Coldwater Heritage Partnership, Pennsylvania’s Growing Greener program, Foundation for Pennsylvania Watersheds and the Miller Brewing Company.

As water quality improved, CRTU worked under California University of PA’s Scientific Collection Permit to electro-shock wild brook trout in a different Dunbar Creek tributary and carried them overland in water-tight backpacks to reintroduce brook trout to Glade Run, where they had been absent throughout the lives of CRTU members.

Three years later, the chapter and its California University partners documented young-of-the-year brook trout spawned in Glade Run.

CRTU’s commitment to Glade Run attracted the attention of the more financially robust Western Pennsylvania Conservancy, which designed and constructed additional treatment systems in the Glade Run headwaters. Wild brook trout are again thriving.

CRTU also does regular litter cleanups, and has worked with American Rivers, Western Pennsylvania Conservancy and California University of PA Partners for Fish and Wildlife to remove obstacles to fish passage throughout the watershed.

In 2022 DEP designated the Dunbar Creek watershed, including Glade Run, as “Exceptional Value Waters,” and acknowledged CRTU’s work in its justifying narrative.

“I’m so proud of our chapter for what it’s accomplished here for wild trout,” Gordon said. “And it’s rewarding to see our achievements noticed by others.”

“There are many ways we can go with this new money,” CRTU secretary John Dolan said of the gas firm’s check. “We can continue our limestone dosing, though water quality is improving with the new systems. Or we can improve

habitat or work to protect hemlock trees there from hemlock woolly adelgid. We may even use part of the money to leverage a grant for the final treatment systems that will enable Glade Run to again be all it can be.”

In our ongoing series profiling ambassadors of FOAM’s Guiding for the Future (G4F) program, we sit down with Micah Fields, a seasoned guide based in Helena, Montana. Micah shares his experiences, insights on conservation and how G4F has shaped his approach to guiding.

Russell Parks: Micah, thanks for joining us. Let’s start with your home waters. Where do you primarily guide?

Micah Fields: The Missouri River is my home water these days. I started in Missoula, so I cut my teeth on the Blackfoot, Rock Creek and the Bitterroot. But the Missouri River keeps me pretty busy.

Russell Parks: You’ve been guiding for about six years now. What’s your guide number?

Micah Fields: 45029.

Russell Parks: Where did you come from originally?

Micah Fields: I grew up in Houston and around Texas. After high school, I served four years in the Marine Corps. I ended up in Montana after wanting to go to college and being drawn to the proximity to fishing. I met my wife in Missoula, and that sealed the deal.

Russell Parks: How did you first hear about Guiding for the Future?

Micah Fields: Through guide friends like Taylor Todd, and Matt Hargrave and outfitters who recommended it. I also saw stickers and heard about it through FOAM. I’m a sucker for continuing education and certifications. Guiding for the Future seemed like something many people I respected had done and recommended.

Russell Parks: Speaking of conservation, you’ve been involved in the recent legislative session. What are your current conservation efforts focused on?

Micah Fields: One thing that always bugs me is the paradox of working in the outdoor industry. We’re inherently adding pressure to the resource. I have a bit

of guilt about that. I try to be a conscious participant in the outdoors. Having a kid lit a fire under me. I’m on the board for Backcountry Hunters and Anglers, Montana Chapter, as the Stewardship Leader. I help manage fence pulls, habi-

A lot of clients come to Montana expecting just to catch fish. I try to enlighten them that there’s more to a day of fishing. I want clients to expect a well-rounded, courteous guide who teaches them about the landscape, history and entomology.

tat and trail improvement projects. I believe every guide should be concerned about the future of our resource. My conservation priorities are access and maintaining stream access. We’re the envy of the country with our forwardthinking access model and abundant public land, water and wildlife.

Russell Parks: What was one of the most compelling parts of the G4F course for you?

Micah Fields: The conservation history coursework was intense and appropriately hard. It’s not just about catching fish; it’s about how we got where we are today, the North American Model of Conservation, and the heroes of conservation. It informs every guide trip for me. G4F is not just a glorified fishing trip. It’s a difficult course with a lot of knowledge packed into a short amount of time.

Russell Parks: How has the G4F course impacted your daily guiding?

Micah Fields: I’m a teacher by trade, and guiding is primarily teaching. G4F taught me a lot more and gave me tools to talk about bugs, the impact on the river and explain the environment. Interpreting the surroundings for people is huge. I try to teach people to be conservationists. Being able to explain complex issues like the Smith Mine situation tactfully and informatively is crucial.

Russell Parks: What does a client get out of a guide who has gone through G4F?

Micah Fields: A lot of clients come to Montana expecting just to catch fish. I try to enlighten them that there’s more to a day of fishing. I want clients to expect a well-rounded, courteous guide who teaches them about the landscape, history and entomology. Ultimately, I’d love for clients to look for the G4F label when booking a guide trip.

Russell Parks: If there was one key takeaway for you from G4F, what would that be?

Micah Fields: We should think about guiding as a community rather than a lone wolf industry. We’re stronger as a community and better conservationists together. It’s easy to think about you against the world, but it’s crucial to understand we’re all on the same team.

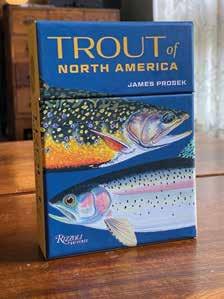

BY JAMES PROSEK ($24.95; rizzoliusa.com)

At the age of 19, James Prosek published Trout: An Illustrated History, prompting the The New York Times to call him “the Audubon of the fishing world.” He’s lived up to that reputation, having now published a dozen other books and exhibited his art throughout the world.

His latest offering is a uniquely beautiful, detailed collection of cards—slightly larger than playing cards and just a bit smaller than index cards—featuring all his paintings of North American trout, char, etc. Each of 60 cards features a detailed color painting on one side, then information on the back including where the fish are found, what are their identifying marks, and then some interesting factoids about each fish. For example, did you know that Arctic char have an average lifespan of 15 years, and some live as long as 30 years?

It’s like having an encyclopedia of all things trout in a package the size of your fly box. Beautifully produced by Rizzoli Universe, which is known for high quality production of artistic books and such, this is an ideal gift… a flash card primer

We are excited to announce that Trout Unlimited’s new online store is officially live at shop.tu.org! Now you can show your support for cold, clean water with high-quality, sustainably sourced apparel and gear from ethical and environmentally responsible brands.

What’s in the Store?

• Classic TU Styles – Always available, always stylish.

• Limited-Edition Drops – Exclusive gear released throughout the year.

• Sustainable, Ethical Apparel –Because fish (and your conscience) deserve better.

Enter TROUTMAG at checkout for a 10 percent discount through August 1, 2025!

Pursuant to the provisions of Trout Unlimited’s bylaws, the 66th Annual Meeting of the members will be held on Wednesday, October 22, 2025 at 8:00pm Eastern via live video-conference to elect and re-elect trustees and to take up any other business that comes up properly before the meeting. Accordingly, voting at the annual meeting will be restricted to active TU members only. The form to vote by proxy at the meeting, the meeting agendajj and video-conference access information will be available at tu.org/annualmeeting25 at least 45 days in advance of the meeting.

BY THOMAS REED

Much has been written of the most remote place in the Lower 48, a place so far back there it is a two-day ride on a fast-gaited saddle horse. Much has been written of Alaska’s wild and lonesome Brooks Range, a great east-west chain of mountains that shoulders the Arctic Ocean on one side and the vast tundra of the Far North on the other. Tales of adventure have been born in these places and upon the anvil of these wild landscapes, great art has been shaped. These are places that test the boundaries of the English language, that cause humans to invent words as if there are no words available at a writer’s behest for such magnificence. Places of remote adventure rife with adrenaline-pumping risk, places of escape, places of connection with soil and sky, water and wildlife.

A few summers back, I stood in one of these places under a harlequin night, slack-jawed at the river of stars in the Milky Way, the constellations familiar and not, an occasional shooting star breaking our upward gaze. We were gathered on the banks of a great river to fish a famous early summer run of native trout, to laugh, sleep on fragrant pine needles, ride good horse friends, sit before pine-popping fires, eat fabulous meals flavored by long days and outdoor experiences. We had a collective thought that traveled osmotically from friend to friend: This, this is what it is all about.

Then across the sky came a belt of strange lights, all in a row, soaring silently up there in the darkness across our night, across our adventure. A few of us wondered what we were seeing, but one among us identified this as a satellite network in the heavens, available

to any one of us for a price. If we wanted to, we could tap into social media right there beside the campfire in the deep woods. We had not really gotten away from it all, after all, and two days in on a fast-gaited horse did not seem that far. What, another of our group wondered, must the Sentinelese—the most isolated people on our blue marble who live by hunting, gathering and fishing by preference far away from the modern world—think of such an affront? Was this not the world’s sky? Their sky as much as ours? Was this not a version of stealing from them, stealing their night? What about all of the other satellites orbiting our tiny lonely planet—estimated to be as many as 25,000—did those machines somehow degrade the experience of those whose lives were not made better by such technology?

These are the kinds of topics that travel around campfires late at night, deep in remote wilderness where humans seek connection to something greater, larger, deeper than our shallow day-to-day routines.

The Internet age has added many definitions to our ever-evolving dictionary, not the least among them new meanings for the words “remote” and “connection.” Ours was a campfire in grizzly bear country, far from hospitals, airports, working telephones and many other modern conveniences. We were as far back in there and as away from it as we could be in 21st century America. But we had not escaped modernity. Indeed, we had used it. We each had cell phones that doubled as cameras in the pockets of our snap button Western shirts. We had tapped into a computer mapping program that showed us our real time

location on these same phones. We had driven fancy diesel pickups pulling deluxe horse trailers to the trailhead. We fished not with bamboo rods and silk line, but with the latest graphite fine-tuned to our individual casting styles. We were anything but Luddites, anything but the Sentinelese isolated on their tiny island off the coast of India.

Yet our experience was somehow downgraded from the raucous adventure we had imagined. Saddened. No longer could I write “back home in civilization” because civilization could be found in every corner of our planet if a string of satellites offering network connection

is our litmus test for the advance of said society.

Technology has brightened our lives considerably. I started a career in journalism using an IBM Selectric typewriter. That sounds horrific to me now. Technology has helped to stop pollution in some cases; think of the photographic chemicals made obsolete by digital photography, for example.

But technology has also sired a complacency and a need-to-be-served attitude. Legend in the National Park Service is the true story of a father-son hiking trip a decade and a half ago in the Grand Canyon in which the group carried a personal locator beacon that could be activated to alert authorities in the case of an emergency. Early in the trip, search and rescue teams were alerted by the beacon and launched a dangerous helicopter rescue mission into the canyon. When they arrived, rescuers found that the group had triggered the beacon because

they had run out of water, but by the time the rescue team arrived, they had found water and were just fine. They sent the rescuers away. That night, the dads and sons triggered the beacon again. Up went the helicopter again. Using night-vision, the SAR team again arrived to “rescue” the hapless hikers. But they were found alive and well. They had triggered the beacon because the water tasted “too salty.”

After the third non-emergency beacontriggering, the rescuers forced the men and their sons aboard the helicopter and out of the canyon altogether. Of course, there are those who would not suffer such fools gladly at any cost, but the other side of the equation is that at least they went, at least they tried for a great adventure in the outdoors. They could have stayed at home and explored it online.

The good news of all this is that technology has advanced since that 2009 incident. I learned by watching a commercial during last winter’s Super

Bowl, that if I had a cell phone of a certain provider, I could tap into that string of satellites and just make a phone call if the water tasted too much like it came from the sea. If that were the case, the poor ranger on the other end could just tell me to eat dirt rather than launch an airborne mission.

Nevertheless, a bit of sorrow hangs over all this change. When is all of this enough? I cannot help but think that the horseman being passed by the Model T had a similar lament. I cannot help but think that we have stolen the night sky from our children. Never again will a human be born on this planet without some man-made device slicing through the night sky. My son will never see a sky where the only belt of light in the heavens will be Orion The Hunter’s.

Thomas Reed ranches and writes outside Pony, Montana. He is the author of Blue Lines, A Fishing Life

These are the kinds of topics that travel around campfires late at night, deep in remote wilderness where humans seek connection to something greater, larger, deeper than our shallow day-to-day routines.

WORDS BY JOHN GIERACH PAINTING BY BOB WHITE

I first laid eyes on Missoula during a fishing trip to Montana sometime in the 1970s, shortly after Noman Maclean’s book, A River Runs Through it and Other Stories, made the region in general— and the nearby Blackfoot River in particular—even more famous among fly fishers than it already was. That was 40 years ago, so I don’t actually remember, but we probably came into town for the usual reasons: to pick up provisions and, as long as we were there, to get a good café breakfast at a place with a counter and stools, booths along one wall and a waitress who addressed us individually as “Sweetie” and collectively as “Boys.”

You didn’t have to look hard to see that this was a fishing town. Trailered drift boats were a significant feature of what passed for morning rush hour and although there wasn’t actually a fly shop on every corner, if you needed a fly shop, you wouldn’t have to go far to find one. Not all that surprising for a place within easy range of not only the Blackfoot, but the Clark Fork, Bitterroot, Rock Creek and their tributaries—some 300 miles of fishable water within an hour’s drive from town, all of it good if you knew what you were doing and your luck held.

Without quite realizing it at the time, I was making the regular stops on the American fly-fishing pilgrimage—at least those places that drew the most attention with guide services, destination fly shops and good press from the magazines. There were plenty of these distinct neighborhoods with place names that evoked adventure for visiting fishermen and another day at the office for local guides. People talked a lot about golden triangles back then and when these fisheries were in their prime it was easy to imagine the Mountain West as a series of interlocking golden triangles scattered across the landscape like spilled jewelry from

northern New Mexico to the Canadian border and beyond.

I was out to see as many famous rivers as I could (maybe I had a premonition that this might not last) and at the same time was already developing a soft spot for what have been called “second class waters:” rivers, creeks, ponds and lakes that held trout, but, for one reason or another, weren’t fashionable or crowded yet and maybe never would be. They were scattered around haphazardly in trout country and in the days before the Internet, social media and hand-held GPS units, certain sweet spots could still be held close to the vest by locals and a reputation as someone who wouldn’t kiss and tell could sometimes get you a solid gold tip.

Some time later I began to swing through Missoula every few years on book tours where the independent Fact & Fiction Bookstore was a regular and welcome stop, but I rarely tried to fish. Often it was in the spring when conditions weren’t ideal anyway, but the real reason was that combining activities as disparate as book promotion and fishing has a way of sucking the life out of one or the other if not both, especially when the schedule is tight. Previous experience had taught me that the things you have to do should be done with due diligence and the things you love should never be rushed, especially when rushing is so antithetical to the soul of the thing. Thomas McGuane nailed it once and for all when he said, “Fishing is extremely time consuming; that’s sort of the whole point.”

But fishing was always in the wind and impossible to ignore. One time I was walking off my pre-event jitters on a bike path along the river when I saw an osprey catch a nice-sized trout—maybe 14- or 15-inches—manhandle it while he was still airborne until it was pointing straight ahead instead of sideways for better aerodynamics, and then flap off, presumably to hungry chicks waiting in the nest. I felt the twin stabs of envy and admiration that are so familiar to fishermen and my nerves quieted down.

Another time, I was having lunch in a restaurant overlooking the Clark Fork with Susan, the woman I’d lived with for two decades then and would eventually marry. The river was a little high and off-color, but still fishable and the big picture windows along one wall offered a widescreen view of a man nymphing an inside bend as diligently as a heron working the shallows of a pond but still coming up blank. I asked our waitress if this stretch of river fished well and she said, “Yeah, I think so. There’s an old man we see here a lot who just hammers fish.” After the waitress left Susan said, “If she’ll describe him to you as an ‘old man,’ he must be ancient.”

I was out to see as many famous rivers as I could (maybe I had a premonition that this might not last) and at the same time was already developing a soft spot for what have been called “second class waters:” rivers, creeks, ponds and lakes that held trout, but, for one reason or another, weren’t fashionable or crowded yet and maybe never would be.

More recently I went to Missoula in September to accept the Writers on Water Award from the creative wiring department at the University of Montana. I’d never heard of this award, but this was the first time it was being given, so no one else had heard of it either. No matter, I was happy to accept. Once at a book fair I heard a not terribly well-known writer say of so-called “minor” literary prizes, “If it’s not a National Book Award or a Pulitzer, you’re just a big frog in a little pond,” and I remember thinking, What’s wrong with little ponds?

I didn’t ask a lot of questions when I got the call, so didn’t get the lay of the land until I got there. I knew this was a fundraiser for the department—the graduate-level equivalent of an elementary school bake sale—and I knew there’d be two days of float-fishing beforehand as part of the festivities, but it was only at a gathering of donors the first evening that I learned it was a fishing contest. Or at least that was the idea. We were all presented with fancy wooden fly boxes containing the handful of flies we were supposed to use—a couple dries, a couple of nymphs and a streamer—and someone explained the rules. And that’s the last time I heard much about the contest. As far as I could see, most of the donors politely declined to compete and just went fishing.

I recently dug out that fly box to remind myself of the name of the event— “Hooks for Books,” the kind of title a committee might come up with— and found that it was empty. The flies weren’t patterns I’d normally use and I wonder what I did with them. They were beautifully tied and as a fly tier myself, I wouldn’t have let them go to waste.

Whenever I travel in the West I’m struck by changes that were inevitable in hindsight, but that I didn’t see coming. Once, the typical pickup you’d see in Missoula was a working ranch truck: old and mud-spattered with its bed filled with unromantic but useful things like steel T-posts, rolls of barbed wire and a post driver. Now, the average pickup is late model and freshly washed with a bed so pristine it looks like it’s never hauled

anything more serious than groceries from the nearest Whole Foods Market. And where once most businesses were recognizable banks, bars, cafes and hardware stores, you’ll now see establishments like REVOLVR, which I’d have once assumed was a gun store owned by someone who didn’t know how to proofread, but now recognize as some kind of ironic boutique.

But there are still comforting remnants of the old Missoula. For instance, there are still plenty of fly shops (11 at last count) and there’s a prevailing attitude that’s recognizable. That first morning, when some of us from Hooks for Books tromped through the hushed eggshell and chrome hotel lobby wearing waders, carrying fly rods and feeling a little out of place, no one even looked up. Likewise, out front it was business as usual as trailered drift boats pulled up in the valet parking lane to collect the fishermen.

That morning we drove out of town, turned up a dirt road and followed it a long slow way through sparse and sunny

But there are still comforting remnants of the old Missoula. For instance, there are still plenty of fly shops (11 at last count) and there’s a prevailing attitude that’s recognizable.

pine woods to an unimproved put-in on the upper Blackfoot, possibly as far up in there as you can get towing a drift boat. Once there we dawdled a bit on this chilly morning and I thought maybe our guide, Tony, was killing time to let the water warm up a little before we started fishing. I didn’t ask. On trips like this the guide sets the pace and impatient clients with other ideas are usually wrong. It turned out that Tony was studying creative writing—as were some of the other guides—and it made perfect sense. Guiding is more interesting, better paying and more flexible than most student jobs and if you’re a writer, there are worse places to observe the varieties of human behavior than on a trout river.

I’d never floated the Blackfoot this

far upstream and all kinds of things go through your mind on new water. A fisherman’s brain automatically crackles with tactics. Where are the fish? What are they doing? How can I get a drift over there? But a river exhibits something like body language and I like to think that if I take in the whole scene and dip a hand in to see how cold the water is, I can begin to sense its mood, which on that morning struck me as indecisive. My partner in the boat that day was a man who went by “C.J.”—a quiet and diligent fisherman—and although I landed a 19-inch bull trout on my third cast, the rest of the day passed at a slow, steady pace for both of us. Some trout fed in small pods and singles here and there along the river and we’d pick one up

now and then on hoppers and droppers, Mahogany Duns, Flying Ants, swung soft hackles and such; each fish briefly interrupting a meandering conversation that would then pick right back up again. I learned that although some still fish the Blackfoot as a bucket list river for literary reasons, by now many have never heard of Norman Maclean or A River Runs Through It—either the book or the movie that was later made of it. That film did make a splash in its time (early 1990s) and some said it put fly fishing on the map, but I’m not so sure about that. Fly fishing was already clearly marked on the maps of everyone I knew then and although the movie had plenty of fly fishing in it, that’s not really what it was about. I heard it was especially puzzling

to anglers in England who were expecting an instructional video.

The next day I floated a stretch of the lower Bitterroot with a guide named Nick and Chris Dombrowski. I first met Chris when I gave his book, Body of Water, a favorable review during my extremely short stint as a book reviewer for The Wall Street Journal. Since then we’ve corresponded some, fished together a time or two and just generally joined each other’s loose network of writers and fishermen.

When we met he was a poet with an MFA working as a fishing guide; now he’s the Assistant Director of the Creative Writing program and presumably on a trajectory with the happy ending of tenure somewhere downrange, but we’ve never really talked about it and even as an

undergraduate 54 years ago I never quite grasped the intricacies of the academic track. All I really knew was that, viewed from a distance, it seemed to move too slowly and had way too many moving parts for my taste. Meanwhile, my friends and I were interested enough in our courses to do reasonably well, but we still had time to eagerly gave in to all the distractions available to college students in the late 1960s, including political activism, music, certain controlled substances and the burgeoning sexual revolution that made those years such a fine time to be alive and young.

There were more fish up working the surface on the Bitterroot than there’d been on the Blackfoot the day before and I managed to hook and land a few,

but distraction had thrown my timing off and I wasn’t fishing well. The event was that evening and although I’m not generally prone to stage fright, I was aware that when you’re asked to read from your work in front of a tough crowd of other writers on the occasion of winning an award, you had better damned well bring the goods.

I especially remember one fish from that day. Nick spotted him first and pointed him out. He was feeding quietly toward the bottom of a pod of risers and slightly off to the side. He had a bigger head than all the rest and moved more water with what you imagine were wider shoulders. He seemed larger by half than any other fish we’d seen, which would put him firmly in the 20-inch class. It was a judgement made on the thinnest of clues, but I was so convinced that I could almost feel the weight of the fish against my bent rod, dead as a tree stump on the set, and then going all lively and electric. When we got in range I was happy enough with my cast and even happier once I’d thrown a small mend to adjust the fly’s position and straighten the leader. Then I followed the drift and waited. When the fish took Nick yelled, “Set!” and when I did I came up with nothing but the appalling finality of a slack line as if the fish not only wasn’t there, but never had been. There wasn’t even that telltale bump as the hook almost catches, but then doesn’t. In the immediate aftermath, Nick said something to Chris about not wanting a fish more than the client does and I thought that missing a big trout because you were distracted by other matters was proof of concept for not mixing fishing with book business. Back in town, when we were asked how we did, I said “Okay,” which is angler’s shorthand for “we caught fish, but let’s not size each other up by comparing body counts.” Each fisherman has his own ideas about what constitutes success and mine was formed during a time in my 30s when I tried to live as much by subsistence as the realities of the late 20th century would reasonably allow. I remember my surprise at learning that

That film did make a splash in its time (early 1990s) and some said it put fly fishing on the map, but I’m not so sure about that. Fly fishing was already clearly marked on the maps of everyone I knew then and although the movie had plenty of fly fishing in it, that’s not really what it was about. I heard it was especially puzzling to anglers in England who were expecting an instructional video.

even partial subsistence was a full-time job and by how much time and effort went into not all that much in the way of fish, game, backyard chickens and eggs, home-grown vegetables, foraged mushrooms and raspberries and local pine firewood. For as long as it lasted the struggle seemed worthwhile and instructive and it also taught me to see success not as a bonanza akin to winning the lottery, but as something incremental, modest and hard-won. Ever since then people who crow too loudly about how many fish they caught or complain too loudly about what they’d call a bad day of fishing have seemed to me to be missing the point. I once heard the story of a man who was fishing in a war-torn region of Africa when he was captured by insurgents who killed him, skinned him and hoisted his hide on a pole like a flag. Now that was a bad day of fishing.

The event went well. I did my reading to a few laughs in the right places and what I thought was more than just polite applause (you imagine you can tell the difference) and then took a seat as the fund-raising auction began. I sat through the bidding on the first few items and got the sense this would be interminable, so at what I thought was an opportune moment I grabbed my hat and quietly made for the door. Outside it was past dusk, with store lights and headlights burning and the air cool enough to zip up the fleece vest. There were a few people out driving or walking, but not many and no one seemed in any hurry to get where they were going. It was another September Sunday evening in a small western city.

I took a breath. Everyone appreciates recognition, but as a native Midwesterner who was raised to measure up, but not stand out, it was a relief to be back out of the spotlight again; just another anonymous baby boomer in comfortable shoes and a shapeless hat.

Back at the hotel I arranged for an Uber to the airport in the morning, packed my duffle and turned in early, only to be awakened with a start when my cell phone rang at three in the morning. The caller ID said it was Susan, who I knew was out of the country traveling in Greece and Turkey, so I answered, imaging the kind of trouble you only get into when you’re far from home; the kind that results in calls to the American consulate, international money orders and that vast sense of helplessness brought on by distance.

But it was only a butt dial. There was no reply when I answered, just the sound of calm, muffled conversation—although I couldn’t make out the language—and something that might have been the clinking of silverware. So, a meal, but which one? I thought about time zones, the international date line and the rotation of the planet that makes the sun seem to move through the sky, but in the middle of the night, in a hotel room in Montana, I couldn’t work out if it was still yesterday where she was calling from, or already tomorrow.

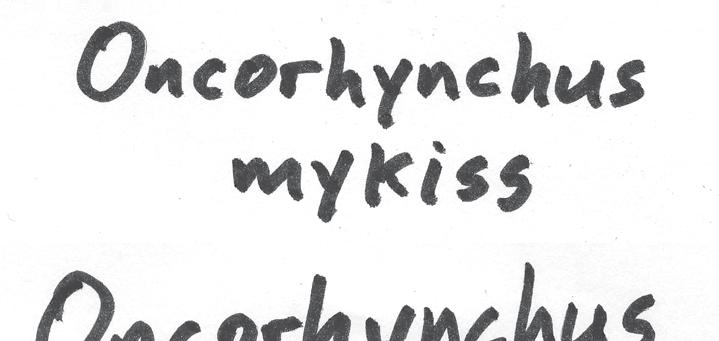

It may seem “all Greek” (or Latin) to many of us, but there are good reasons to learn the scientific names of insects, fish and more…

BY J.W. MARTIN

It’s fairly common to encounter, in fly-fishing magazines, books and podcasts, the sentiment that you don’t need to know the scientific names of bugs. And that’s undeniably true. You don’t need to know these names. The fish certainly don’t know them. In fact, nobody knows all of them. That’s partly because in many parts of the world, even well-known parts, new insect species are still being discovered and named on a regular basis.

I was listening to a podcast about fly fishing in the Great Smoky Mountains (the Orvis Fly-Fishing Podcast , February 4, 2024), and the person being interviewed, well-known Great Smoky Mountains guide Charity Rutter, noted that even there, in the most visited national park in the United States, there are undiscovered and undescribed aquatic insects, insects whose name nobody knows. In the last 20 years, Rutter estimates, nearly 200 new species of aquatic insects have been named in that park alone. What does this tell us about more remote rivers and less explored parts of our planet?

clarity, no assurance that we are all talking about the same thing. And if we want to protect something, whether it is a species or a microhabitat or an entire drainage, we need to know what we are talking about in order to make cogent arguments for increased stewardship and conservation.

Additionally, these scientific names can be, on their own, extremely informative; the names by themselves tell us things and speak to the fascinating

IF WE RELIED SOLELY ON THEIR COMMON NAMES, THIS INFORMATION, AND WISE CONSERVATION DECISIONS BASED ON THIS KNOWLEDGE, WOULD NOT BE POSSIBLE.

which was mykizha. Thus, we can tell from the name alone that Oncorhynchus mykiss is “the hook-jawed fish from the Kamtchatka Peninsula.” This binomial name sets it apart from all other species of fish on the planet. Marine fish are also sometimes named this same way, telling us not only what they look like but also where they are found. The Atlantic tarpon’s name makes perfect sense: Megalops atlanticus tells us that it has big eyes and lives in the Atlantic. So do a lot of other species, but tarpon were given this name first, so they get to keep it.

But that’s different from saying that scientific names are unimportant, and I want to dissuade anyone from thinking that knowing these names is something reserved for fly anglers with nothing better to do with their time. Scientific names are critically important, and they are one of the vital tools we employ in freshwater and marine conservation.

I work as a curator in a large natural history museum, and my research is in the field of systematic biology, the study of the relationships of organisms. The organisms I study are crustaceans, mostly crabs and shrimps, and from time to time it has been my job (thoroughly enjoyable) to name some new species. You could argue (and you would be correct) that I have a vested interest in promoting the importance of scientific names. But it’s far more than that. Without scientific names, there is no

history of our study of life on Earth. Let’s look at a couple of examples related to fly fishing.

The rainbow trout is a nice starting point. Rainbows have the scientific name Oncorhynchus mykiss, a mouthful to be sure, pronounced like “ON-co-RINK-us MY-kiss.” The first name (Oncorhynchus) is called the genus, a higher category to which this species belongs, and the full name Oncorhynchus mykiss is the name that is unique to this species and to no other species on Earth. We always italicize the names because they are not English words (in this case both genus and species names are derived from ancient Greek). Oncorhynchus comes from the Greek words onkos (meaning “hook”) and rynchos (meaning “nose”), and it refers to the hooked jaws of the males, commonly called the kype, during the mating season. Thus, the genus name refers (in this case) to the morphology of the species. This genus Oncorhynchus includes several Pacific species of salmon and trout. The specific name in this case (but not in all cases) has a geographical history behind it. The species O. mykiss was first named by the German naturalist Johann Walbaum back in 1792, based on specimens from Russia’s Kamchatka Peninsula. Walbaum’s original name, mykiss, referred to the local Kamchatkan name for these fish,

Fish can also be named after people. Cutthroat trout, for example, are Oncorhynchus clarkii, named in honor of William Clark of the famous Lewis and Clark Expedition, who recorded these fish in his journal from the Missouri River near Great Falls, Montana. Today we know that there are several subspecies of cutthroat trout, all with their own unique names, habitats and biological requirements. The fact that cutties are in the same genus (Oncorhynchus) as rainbows lets us know that the two species are closely related. Using common names alone obscures this kind of information. Brown trout, for

example, regardless of where they are found today, are Salmo trutta, which tells us that, biologically speaking, they are not as similar to rainbows and cutthroats as they are to the marbled trout of the Balkans, Salmo marmoratus, or Atlantic salmon, Salmo salar. If we relied solely on their common names, this information, and wise conservation decisions based on this knowledge, would not be possible.

In the world of insects, I have always loved the fact that mayflies are in the order Ephemeroptera. “Ptera,” at the end of the name, is from the ancient Greek ptera or pteron, meaning wing, and is seen in other names of insect

groups: Lepidoptera (scale-winged) for the butterflies and moths, Diptera (two-winged) for the true flies, Coleoptera (shield-winged) for the beetles, Plecoptera (folded-winged) for the stoneflies, etc. The front part of the name Ephemeroptera comes from the same root as ephemeral, meaning brief or temporary, an allusion to the very short adult life of a mayfly. What a great name for the group that includes these wonderful insects that are with us for such a brief time.

How many different species of mayflies are there? More than 3,000 currently, grouped into more than

400 genera (the plural of genus) in 42 families. According to the website, “Mayfly Central,” at Purdue University, there are 23 families and 108 genera in North America alone. I don’t suggest that you try to learn all 3,000 species names or even the 400 genera worldwide or the 108 in North America. But, on the

other hand, if we lump them all together as just “mayflies” we run the risk of losing important information about individual streams, lakes, insects and their complex interactions. If we want to protect a population of Hexagenia, which are burrowers (and there are several species of Hexagenia in North

America), we might want to know how they differ from species of Ephemerella, the larvae of which are crawlers. Using just the common names does not give us the information we need to distinguish them.

In the marine realm, the situation is in some cases worse because many

marine species are so widespread that they’ve been given common names wherever they are found. Bonefish are a good example. The scientific name for bonefish is Albula vulpes (based on the Latin for “white fox,” as cool a name for bonefish as you could ask for). But some of their common English names include bananafish, ladyfish, round jaw, salmon peel, tarpon, tenny and more. In other languages—and the following list is only about a third of the total number that I found on the website of the Florida Museum of Natural History— they are called albula (Polish), albule (French), albulid (Swedish), banane (French), banang (Malay), beenvis (Afrikaans), bending curut (Javanese), bidbid (Tagalog), bonouk (Arabic), bulat daun (Malay), carajo (Spanish), chache (Swahili), colepinha malabu (Creole), colvino (Spanish), conejo (Spanish), damenfisch (German), far al bahar (Arabic), frauenfisch (German), gatico (Spanish), gato (Spanish), hermaanchi (Papiamento), inliaula (Spanish), ioio (Tahitian), juruma (Portuguese), kifimbo (Swahili) and many more. With so many common names referring to the same species, how will we ever know what we’re talking about? How will we know what we are trying to protect? We need an agreed-upon, specific name that is unique to this species, hence the use of scientific names.

labeled as snappers and sold in local grocery stores, with their heads and skins removed so that you cannot tell what they looked like when they were alive. Some need to be protected by more stringent fishing regulations. But how can we ever hope to protect them if we cannot even tell them apart, if we just call them all rockfish? With more than two million species described and named so far by taxonomists, and countless more still awaiting discovery and description, it’s clear that there are many, many more examples I could have chosen.

Knowledge of scientific names and classification can even have an effect on how some flies are tied. If you want to tie