NARRATION OF CONTESTED CULTURE

The role of narrative structures in the renewal of cultural identity

Author: TRISHA SARKAR

Affiliation:

ARCHITECTURAL ASSOCIATION, SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE, LONDON, UK.

INTRODUCTION

“The history of heritage is a history of the present, or rather, a historical narrative of an endless succession of presents, a heritage of heritage that can have no terminal point ” 1

The creation of narratives manifests as an assemblage crafted through linear and relative sequencing that represent heritage as both retrospective and prospective forms of cultural memory. The process entails the consolidation of evidence from disparate sources to concoct a realistic account of the history of cultures, their evolution, struggles, and triumphs Multiple perspectives converge and diverge, celebrate and eviscerate cultures through their process of narration, evidenced through disagreement, divergence and subversion. In the context of cultural heritage and for the purposes of crafting national legacies, narratives have been employed as tools which have often adversely affected authenticity, representation and intent Culture and narrative, in this regard form two distinct pathways into heritage discourse that occasionally collide to illustrate discordance and the deliberate manipulation of the latter to suit the former. The manipulation of national histories which narrate social and cultural evolution through events have often been orchestrated by governments to a preserve a monocultural and hegemonic national image. The obliteration of cultural influence, and a denial of historical precedent has contributed to the production of counter-heritages. These processes represent an institutionalization of cultural heritage which has contributed to Authorized Heritage Discourses (AHD) - the state sanctioned approach to discourses on heritage constructed through public policy in archaeology and management practices. The modernization of the national narrative relies on the degree of dissonance officially acceptable in the course of its formation. “Because there are always several, often conflicting, meanings, which are bestowed on heritage, it is always dissonant.” 2 The contrast between “cultures” and their “narratives” has been defined further through restrictions imposed by means of legal regulation and statutory control, and alternatively, contestations in relation with urban renewal schemes in rapidly developing metropolises. The historic environment counters these contestations and restrictions through narratives that seek to reinstate authenticity, and create a diversified perception of cultural history

Linear Trajectories

Employment and Critique

David Harvey has argued against a linear narration of the history of heritage as it becomes difficult to date this process following a logic that implies a sequential unraveling of events with a precedent influencing the immediate antecedent. The author suggests alternate modes of envisioning the historical evolution of heritage as product and practice that can be constructed through a history of power relations in the form of a socio-political paradigm. The governance and administrative mechanisms that deploy heritage practices have collectively crafted the direction and course of heritage in an effort to preserve specific cultural forms and craft national identities. In addition, both processes exist and are governed through a reciprocity. Heritage through history has been influenced by “technological advancement, new modes of representation and levels of access and control.” 3

Archaeologists have emphasized the significance of time and its employability in the discernment of “archaeological record” in addition to its role in the creation of “archaeological phenomenon”. 4

Cremo states that the study of these records has suggested that linear-progressivist conceptions of time have hindered the objective evaluation of records and rational theory building in the discourse of human origins and antiquity. In addition, with the emergence of new evidence that disproved biblical record, for instance the date of creation, the role and reliability of linear sequencing was questioned and required revision thereafter.

Cremo critiques the linear conception of time in the context of the archaeological record that has related classical antiquity with the Judeo-Christian tradition contained in the Bible, which have, in his opinion rendered them areligious. Additionally, he has stated that without an examination of the roots of Modern Anthropology, which are arguably religious, distinct and definitive in terms of their predictions, the discipline should not assume to offer a universal understanding and method of practice with regards to the creation and classification of historical records. Modern Anthropology, not unlike Archaeology has suffered the consequences of selective prioritization and the distortion of historical records as a result of a poor understanding of time and causality.5

Relative Sequencing

More recently an expanded focus on postmodern theory in the social sciences has altered perception with regards to the time, order and the nature of sequencing. The notion of historical time has transformed from an objective to a subjective form. Concurrent historical events have demonstrated an absence of causal links which have prompted a revisioning of the historical narratives. The construction of a narrative that bridges non-linear historical events draws on processes of relative sequencing to present an argument for cultural heritage. The role of narration in this context is to extract and assemble historical events and processes in the interest of representing disjointed periods in history. Distinct from a direct cause and effect relationship, the relational structure of historical events indicates the existence of a “historical space” 6 or paradigm that has been transformed over time and is disjointed structurally and in configuration. In this way, it redefines the traditional notion of causality, which is configured on a framework distinct from a linear sequence This juxtaposition of events and processes seeks to represent holistic and diverse cultural and national narratives through the attribution of values on the future in relation to a past.

“ Thinking of heritage as a creative engagement with the past in the present focuses our attention on our ability to take an active and informed role in the production of our future.” 7

The present must be contextualised within a relationship with the future and the past. This is inevitable in terms of historical production, however, what remains to be seen is the specific nature of this correlation and the ways in which it informs historical analysis and cultural production. The present contributes to the sequence of historical timeline through its role and relevance as a reference for current architectural and urban conditions. The influence of the present time, in this regard, is factored into historical timeline reinstating the present as a valuable entity. This narrative sequence and form proposes a revised model of history8 as a structuring of dynamic and transformative trajectories. It re-conceptualizes causality and evolutionary trajectories introducing the possibility of multiple pathways. It reorients the perception of time and space in the renewal of archaeological ontology and the historical narrative. The non-linearity of historical narration often falsely attributed to the insufficiency of information9, has enabled dialogue and discussion on heritage, culture and national image. In addition, this form of narration creates a platform that encourages alternative perspectives to emerge, with a shift in centrality within communal and social histories. Historians and heritage specialists have employed the use of non-linear narratives to relate and analyze cultural arguments created by diverse groups and collectives composed of governmental and nongovernmental actors and networks. As a result, it can be stated that non-linear histories are essential for the sustenance of heritage discourses and time nurtured narratives of traditions integral to social and ethnic groups. ‘Counter-heritage’, ‘refugee heritage’, ‘dissonant heritage’ and ‘difficult heritage’ are derivatives based on non-linearity that embody a wide range of approaches that historicise culture specific arguments within distinct borders.

Case Study : The Bevis Marks Synagogue

The role of the narrative as a form of prospective memory has emerged however, as a product of retrospection and its particular interpretation. This has enabled a form of narration drawing on diverse physical environments and across time periods.

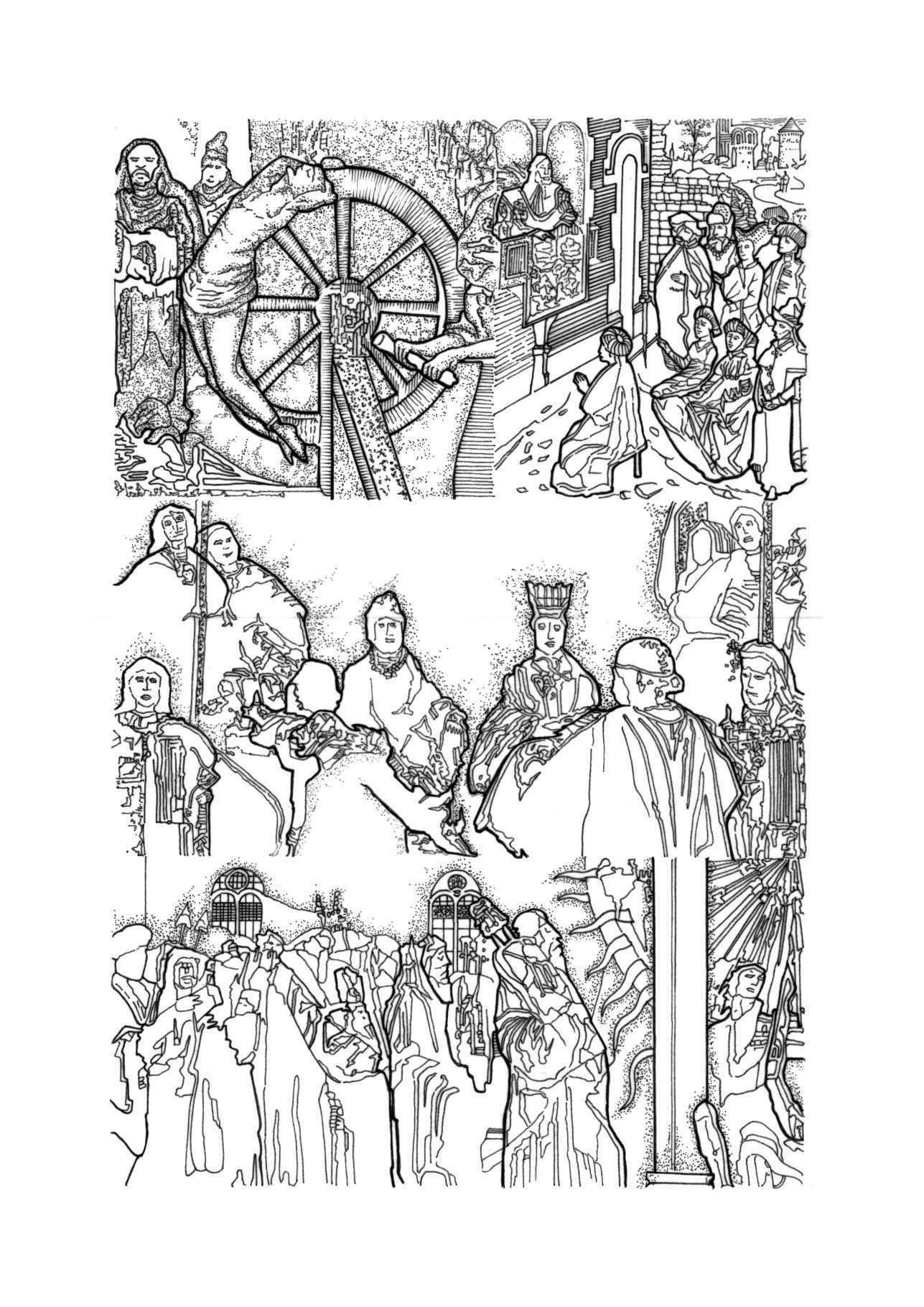

Figure 1. Eviction, Resettlement and contestation of Jewish practices across Europe and the United Kingdom : A historical narrative drawing on narrative styles and sequence of the Golden Haggadah

The Bevis Marks Synagogue

Jewish houses of worship in the City of London, from a perspective external to the community, can be characterized as significantly subdued in nature. This is primarily owing to the segregation of a community as a consequence of migration, disproportionate distribution of financial resources and the demolition of synagogues.

The Bevis Marks Synagogue is the oldest synagogue in the United Kingdom and is located in the City of London in the eastern City Cluster. The Synagogue is officially known as the “ Qahal Kadosh Sah’ar ha-Shamayim ” the Hebrew translation for “ Holy Congregation Gate of Heaven ”. Built on its current site in 1701 following the relocation of the congregation from the site of the first synagogue built on Creechurch Lane, it served as a refuge for crypto-Jews10 from Spain and Portugal, and the Sephardi Jewish community from Amsterdam in the mid-17th century. At present, the synagogue enjoys an international membership and support, invested in its maintenance, care and preservation of historic identity and cultural capital within the city. Over the last few years, however,

as a result of threats of eviction and the sale of land in addition to issues of encroachment and overshadowing, the Jewish house of worship has been engaged with expansion, renewal and public accessibility seeking to reinstate national and international ties to envision a sustainable future for the community

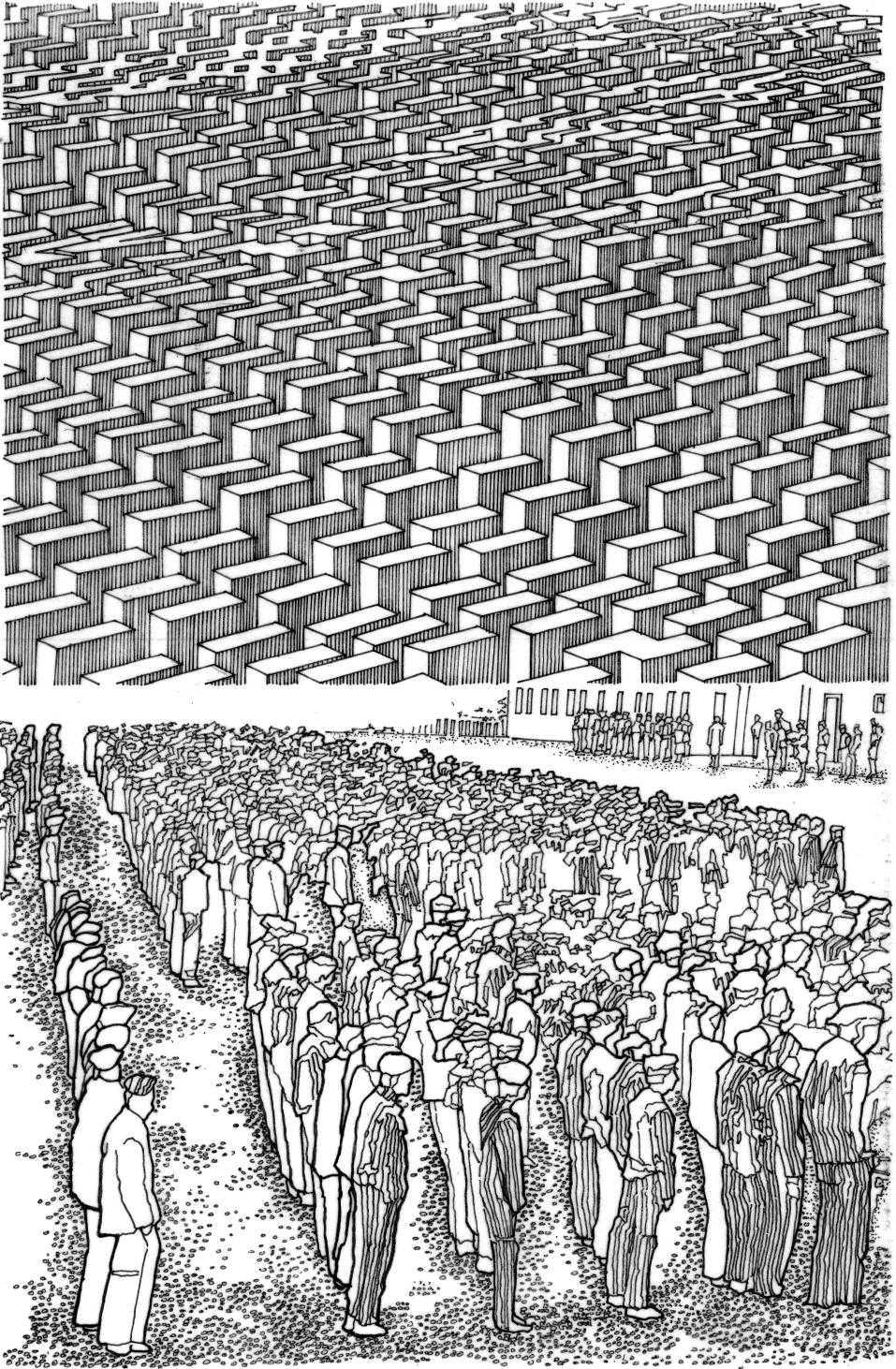

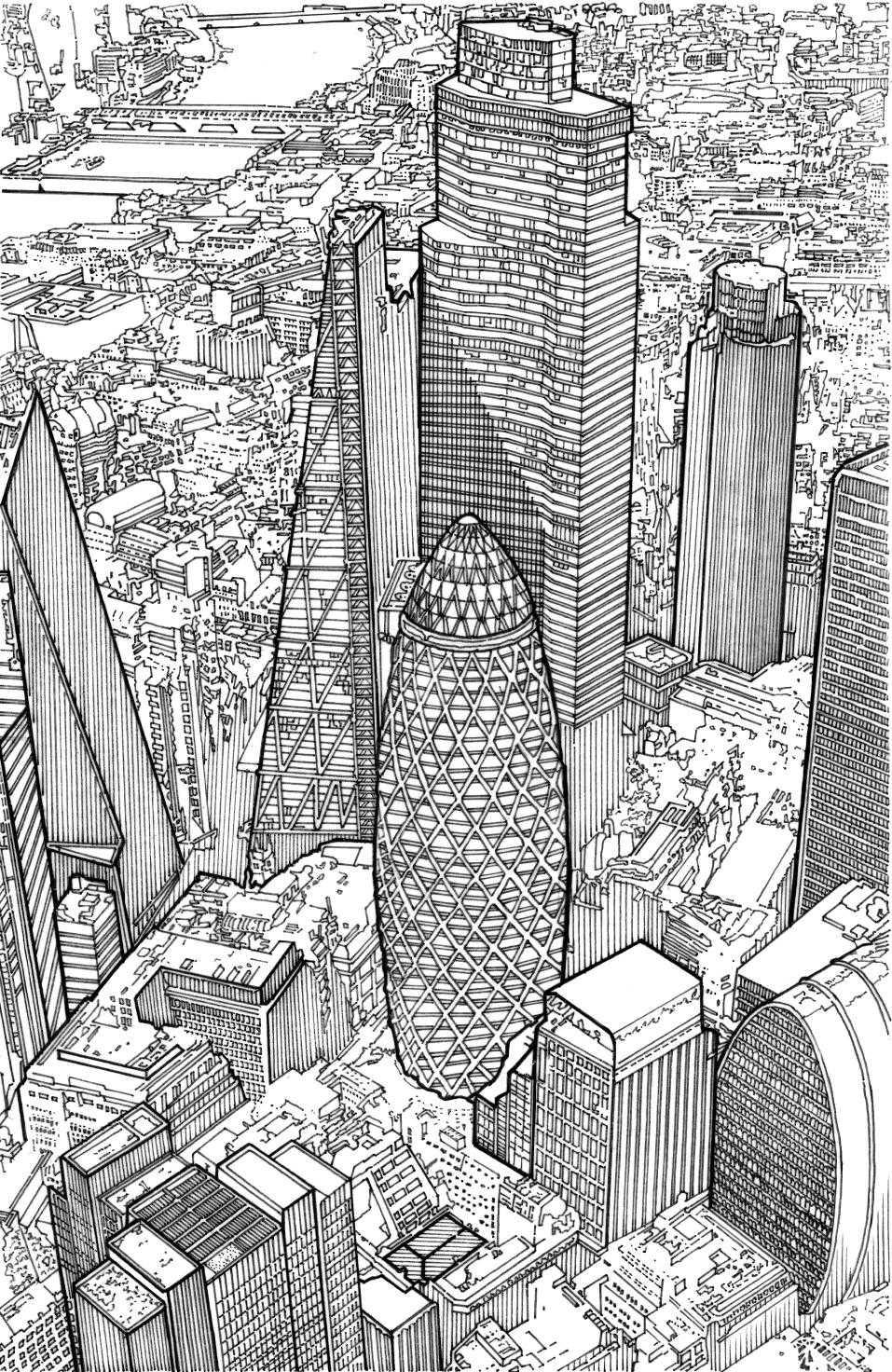

21st Century Threat of overcrowding

The site of Bevis Marks has been at risk over the last couple of years due to plans of building high rise towers in its immediate context. The development proposal including two towers of 48 and 21 floors would have potentially blocked natural light from reaching the synagogue. Among high rise commercial and business complexes, the area is dotted with a few remaining churches and the only synagogue that has been in use for the last 300 years. The listed buildings in this context including the Grade-I listed Synagogue are few and primarily situated in areas protected by a conservation cover. The remaining listed and non-designated heritage buildings in the vicinity of the synagogue that are not protected by a conservation cover face a similar threat from the construction boom in the Eastern City Cluster.

The Jewish Community have been concerned with high-rises proposals which, on approval, would result in the infringement of the religious rights of the community. The sky view from the house of worship being integral to religious practices of the community is governed by the appearance of the sun, moon and celestial bodies which determine prayer timings, the duration of Sabbath day, the Jewish calendar, and the new month according to the lunar cycle. A restriction of views to the south and east of the synagogue would prevent the recital of certain prayers and affect the context that situates Jewish religious practice in relation with the cosmos. Alternatively, a proposal to protect sky views from the synagogue will in the future, contribute towards the preservation of the intangible heritage of the synagogue and the Jewish community.

The impact on the operation, cultural significance and accessibility to the Synagogue would have been irreversible if the planning proposal were approved. Despite recent proposals being withdrawn, the community remains vigilant with regards to future potential risks of encroachment.

Eviction and Resettlement ; Dispersion and Damage

The Bevis Marks Synagogue was constructed after Jews resettled in England in the mid-17th century following their eviction in the 13th century (1290) through the edict issued by King Edward I The Migration of crypto-Jews or Marranos from Spain and Portugal, in addition to a growing Jewish community in Amsterdam have contributed to a shift in population and the growth in congregation in England. The practice of Judaism was permitted only after the Jewish resettlement in England under the rule of Oliver Cromwell. However, the steady influx of Portuguese Jews in 1735 began to diminish by 1790, after which the principal language for sermons changed from Portuguese to English.

Concurrently, following the Alhambra Decree in 1492, the eviction of Jews from Spanish and Portuguese territories sought to eliminate their influence on the significant converso population in both territories. Sections of the community comprising primarily of crypto-Jews emigrated to Dutch provinces The collective expulsion of the Jewish communities from both the Iberian region and England have led to the resettlement in diverse contexts including North Africa, Italy, Turkey, Greece

and the Mediterranean Basin. The period between 1391 and 1415 witnessed the massacre of the Jewish community that was particularly defined through events of eviction and conversion that evoked the rights of Jewish worship. A disregard of rights was especially evident through intolerance both with regards to the synagogue and the prayer book. Fueled by a fluctuating sense of antiSemitism, the cultural object and artefact evidence a heritage that has been defined by instability and risk over the course of history.

In Spain, the resettlement of evicted Jews and the reinstatement of their citizenship was ensured in 1924 under the regime of Miguel Primo de Rivera seeking to compensate for the losses the community had to endure in the past. The following years did witness a return of Jewish communities to Spain; however, the edict was only officially invalidated by 1968 following the second Vatican Council. The lack of prudency and religious intolerance did not however prevent sections of the community to establish synagogues and persist through their own initiatives of religious sustenance and practice. The synagogue, in this regard, symbolizes a sanctuary for refuge, and a cultural object which has survived and thrived in the face of adversity.

Jewish resettlement and the reinstatement of cultural and religious practice led to the establishment of the first synagogue built on Creechurch Lane, in the City of London, which began service in 1657. The synagogue was subsequently moved as the congregation grew. On completion in 1701, the interior décor and furnishing of house of worship that exists today as the Bevis Marks Synagogue reflected the influence of the Great Portuguese Synagogue of Amsterdam and the designs of Christopher Wren, commissioned with the reconstruction of churches in the London during this period.

In 1738, the roof of the synagogue was damaged by fire and was subsequently reconstructed in 1749. The synagogue suffered minor damage during the London Blitz. In addition, it suffered some collateral damage in 1992 from the IRA and the 1993 Bishopsgate bombing. In the following years, as the congregation segregated owing to differences based on their socioeconomic status, the West London Synagogue was built to accommodate the wealthier sections of the dispersed community from both Bevis Marks and Ashkenazi Great Synagogue to form a congregation dedicated exclusive to British Jews. Subsequently, in 1886, the site of Bevis Marks Synagogue was considered to be sold. In response, a “Bevis Marks Anti-Demolition League” was formed under the stewardship of H. Guedalla and A.H. Newman which halted the sale of the property inspiring future efforts towards the preservation and sustenance of Jewish cultural rights in the context.

Post - War Jewish Migration ( Early 20th Century)

Migration of Jewish communities became especially pronounced in the aftermath of the Second World War. Most countries in Europe denied access to more Jewish refugees citing problems of overpopulation, and a further rise in unemployment and anti-Semitism. Refugees emigrating to Great Britain had to provide proof of employment or financial resources that would support them in Britain. “Kindertransport” 11 or children’s transport established in 1938 facilitated the emigration of 10,000 Jewish children and the children of other Nazi victims to Great Britain. In a conference held in Evian, France in July 1935, the refugee crisis was discussed among 32 countries including Great Britain.

Ariella Azoulay presents a compelling argument that illustrates social and cultural dynamics, and relevant to the discussion The author examines the socio-political conditions by means of which the

individual refugee and the displaced community were rendered “stateless”, an internationally recognized political category that had been known to transgress borders and occupy territory within and beyond the confines of the nation state. The progression, represented through the existence of the refugee and the refuge has, as the author observes, suppressed and neglected past cultural narratives that discuss the dispossessed community and his native territory. Furthermore, Azoulay challenges the linear historical narrative that situates the human condition succeeded by the posthuman, similar to the process of colonization and displacement. The selective inclusion of historical events within the narrative has consciously eliminated records of violence in the progression of the displaced community to the modern state appropriated citizen. The author states that the process of “unlearning imperialism”12 indicates a need for the unlearning of the dissociation that initiated an irreversible movement of people and objects through forced migration to forge relations and networks in alternative contexts.

CONCLUSION

The relational sequencing of historical events in the 21st , 13th and 17th , 15th and 20th centuries and their lasting impact have been instrumentalized to concoct a narrative of contested culture. The cultural narrative, specific to the Jewish community serves to function as the basis for supporting arguments that seek to defend the preservation of the Bevis Marks Synagogue as a Grade I listed building and a collective refuge for a migratory and displaced community in the City of London.

In this paper, I have presented an analysis of cultural narratives that aim to bridge history and heritage, with a critical assessment of the cultural product by means of a twofold argument – the immediate building, and the theoretical and political context it is situated within. The distinct forms of narration and chronological sequencing seek to amplify the role of this theoretical instrument in establishing causal relationships, and in their absence, illustrate correlation between distinct historical events. Heritage is posited as a palimpsest of cultural arguments that collectively advocate for, in some cases the preservation, and in others, the reinstatement of cultural value inscribed in the materiality of the architectural object and historical built environment. Furthermore, the process of Heritagization, as elucidated by Turnbridge and Ashworth, emphasize the need for a “periodic renewal” which offers infinite potential with regard to the crafting of cultural narratives for the future. The narration of contested cultures, therefore, instrumentalizes the role of heritage as a discursive phenomenon and seeks to project the inconsistencies within Authorized Heritage Discourse(s) to create an accurate, non-linear and diversified images of national identity and cultural legacy.

NOTES

1 David Harvey, The History of Heritage for the Ashgate Research Companion to Heritage and Identity, Edited by Graham, B and Howard, P. Ashgate Research Companion to Heritage and Identity, (London: Routledge, 2008), 23

2 J.E.Turnbridge and G.J.Ashworth, Dissonant Heritage: The Management of the Past as a Resource in Conflict (Chichester, New York : John Wiley and Sons,1996),

3 David Harvey, The History of Heritage, 1.

4 Tim Murray, Time and Archaeology London and New York, Routledge, 1999, 1.

5 Michael A. Cremo, Puranic Time and Archaeological Record. Time and Archaeology (London and New York : Routledge, 1999), 1.

6 James McGlade, The Times of history: archaeology, narrative and non-linear causality Time and Archaeology (London and New York : Routledge, 1999), 139

7 Rodney Harrison, Heritage – Critical Approaches (Oxon, New York: Routledge. 2013).

8 James McGlade, The Times of history : archeology, narrative and non-linear causaility, 147

9 The construction of order in relative chronologies was based to an extent on the reduction of difference which led in its turn to the consolidation of similar entities and processes which have been perceived to create coherence and clarity. Relative chronologies for instance, created through typological frameworks1 (Cremo, 1999) that priviledge some attributes and categories of material culture or aesthetic criteria over others, have resulted in a loss of information and diversity of material; processes of simplification known to assist ordering and cataloguing have distorted reality through reductionist approaches. Alternatively, McGlade observes that the employment of such approaches have also created chronological orders through preference and priority based on a few attributes, have led to the creation of faulty records which have been further instrumentalized to produce cultural change, especially in late colonial and post-colonial contexts. McGlade emphasizes the fallacy in the reasoning, however, stating that the drive to establish order through the eradication of discontinuity has morphed the reading of archaeological record, once more ignoring diversity in the data and producing biased narratives.

10 Sections of the Jewish population who had converted to Catholicism but privately practiced Judaism

11 Sephardi Voices UK, sephardivoices org.uk, 1969.

12 Ariella Aisha Azoulay, Potential History, Unlearning Imperialism (London and New York : Verso, 2019), 8.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Azoulay, Ariella, A. Potential History, Unlearning Imperialism, London and New York, Verso, 2019. Cremo, M.A. Puranic Time and Archaeological Record Time and Archaeology London and New York, Routledge, 1999.

Foucault, M. Of Other Spaces : Utopias and Heterotopias, Diacritics 16:1 (Spring, 1986) pp 22-27. Translated from Des Espaces Autres in Architecture-Mouvement-Continuite, October 1984.

Harrison, Rodney. Heritage – Critical Approaches. Oxon, New York: Routledge. 2013

Harvey, David. The History of Heritage for the Ashgate Research Companion to Heritage and Identity. Edited by Graham, B and Howard, P. Ashgate Research Companion to Heritage and Identity, London : Routledge, 2008.

Herscher, Andrew. “Counter-Heritage and Violence”, Future Anterior, Vol. III, No. 2, 2006.

Jolles, Frank German Romantic Chronology, Time and Archaeology London and New York : Routledge, 1999

McGlade, James The Times of history: archaeology, narrative and non-linear causality. Time and Archaeology London and New York, Routledge, 1999

Monk, Daniel B. and Andrew Herscher “The New Universalism: Refuges and Refugees between Global History and Voucher Humanitarianism” Grey Room 61, Grey Room Inc. and Massachusetts Institute of Technology, pp 70-80, 2015.

Murray, Tim. Time and Archaeology London and New York, Routledge, 1999

Nora, Pierre. “Les Lieux de Mémoire” Representation. Spring 1989, No.26, Memory and Counter-Memory University of California Press, 1989, pp 7-24

Rodenberg, Jeroen and Wagenaar, Pieter Cultural Contestation: Heritage, Identity and the Role of Government. Cultural Contestation, Palgrave Studies in Cultural Heritage and Conflict, Cham: Palgrave McMillan, 2018

Turnbridge, J.E. and G.J.Ashworth, Dissonant Heritage: The Management of the Past as a Resource in Conflict Chichester, New York : John Wiley and Sons,1996

savebevismarks.org/the-campaign/ Sephardi Voices UK, 1969 sephardivoices org.uk