Art,Design,Accessability.

Art,Design,Accessability.

Welcome to Triptych, issue one.

In the context of art lingo, Triptych refers to a an artwork composed of three panels that sit next to eachother. Within the context of Triptych magaznie, this translates to the three social and cultural initatives that Triptych aims to contirbute to.

These initatives are:

1.Encouragingtheengagmentinallartformsandexpandingthepreconcievedideasofwhatart includes.

2.Promotingtheimportanceofaccessabiltytobothcreateandengangeinart.

3.Highlightingthewonderfulworkofdisabledandneurodivergantcreatives.

Within issue one, we explore the world of art through disabled and neurodivergent designers, curators, DJs and more.

We hope that as a reader, you either find your new favourite creative or gain inspiration to engage more deeply in the world of art and design. I would like to thank everyone who contributed to the creation of this publication, wether that be the interviewees, contributors and illustrators.

Eloise Stephens. FindusonInstagramandTiktok,@triptychmag_

Page 4

Page 6

Cyber Cherry Clothing: a brand on a mission

Bonnie: a beautiful tribute to Scottish Heritage

Page 12 Celebrating queer art

Page 14 Big beat manifesto: neurodivergence and electronic music

Page 16 Disabled Cants’ show returns home to the Edinburgh Fringe

Page 17 Graeae opens applications for ‘BEYOND’ programme

Page 18 Conversations on: Chronic fatigue as a creative director

Page 20 A meditation on memory

Page 23 Imaginary friend by Daisy Riley

Page 24 Art therapy to artist: Jasmine Lockett

Page 26 Curating accessability: In conversation with Iris Sirendi

Page 28 “Touch some grass!”

Amelie Rule owns Cyber Cherry Clothes, a second hand and vintage clothing brand with a niche in sustainable living with autism and managing her own brand.

Eloise: When and why did you set up your brand and begin curating style bundles?

Amelie: So, about a year ago I bought a style bundle from another brand and upon receiving the clothes I realised they were from fast fashion places like Shien. I thought to myself, I could do this much better. Now I help people renovate their wardrobes but never using fast fashion even if its second hand. It’s a way to help people try out new styles in a more sustainable way.

Eloise: What is involved in the process of making a style bundle?

Amelie: Once someone places an order, I’ll send them a form to fill out with details about the type of aesthetic they like. It takes me about one to two days to make each bundle depending on the amount of clothes involved. I source items from Vinted, Depop and Ebay. I also go to charity shops. Then I’ll measure each piece to gauge whether they are actually the size they say they are. I’ll then send a picture to the customer to check they’re happy with it. You can find pretty decent stuff sustainably it just takes a while.

Eloise: What is your experience with being autistic and running your own brand?

Amelie: Running a company by myself is definitely better. I’ve found with previous experiences working in larger companies they can find it difficult to deal with autism which is unfortunate. That kind of spurred me on to make my own business. A lot of people have said to me autism is a superpower, which is an interesting statement because while it does have certain benefits, definitely 100%, it also has a lot of negative things. I tend to hyperfocus on orders I receive which can lead to burnout.

Eloise: Has your autism influenced your work in any way?

Amelie: I definitely want to make my brand accessible. I’ve had a few clients who are autistic and have sensory issues. So this means they may not like certain materials. I’m just I’m trying to reach more of the neurodivergent audience to try and provide them with, like, fashion that they want to wear, which is like not going to, like, freak them out when they put it on.

Eloise: What kinds of materials can act as triggers to those with autism?

Amelie: A common one I see is metal embellishments or itchy fabrics. Someone wanted a Gothic style bundle and gothic style clothing tends to feature metal accessories. I had a long chat with the person to see what we could do to work around it. I ended up taking a lot of metal bits off the clothing myself to make it work. Another time a customer did not like the feeling of three-quarter length items. In that case I went to charity shops with a tape measure to ensure all the lengths were suitable. I will never charge extra for this even if I have to edit the clothes myself. I just want to make it accessible because know when I was younger, that’s just the clothes that you buy. It’s like they’re great, but then it’s not. They’re not very comfortable and that obviously impacts everything you’re doing because you’re not comfortable in the clothing.

Eloise: How does it feel to be in a position to help people with the same things you have struggled with?

Amelie: It’s super fulfilling. I got diagnosed with autism quite later on in my life and ever since I got diagnosed, I want to make sure that people who many not have a diagnosis yet but have sensory issues are heard and can access

sustainable style bundles catering to neurodivergent fashion fanatics. Rule speaks on her experiences

the clothing they want.

Eloise: What do you think bigger industry brands could do to make fashion more accessible for those with sensory needs?

Amelie: High street brands like H&M or New Look could create lines that maybe don’t have tags in them and items with softer material. These are things that wouldn’t be difficult to do but also be accessible in price. Even with some sensory brands, their clothes are generally quite plain, which is fine but neurodivergent people like colours and patterns too. I think if the industry paid more attention, there’s definitely a niche they could access there.

Eloise: Do you have any future plans to expand your shop?

Amelie: By the end of the year, I hope to release my own fashion line that I’m working on. I’m super excited, but my whole idea with that is, again, to make it neurodivergent sensitivity friendly. But also, what I want to do is I want to make it affordable, because I see the problem with some brands which do amazing things, but they’re very expensive. Obviously, not everyone can afford that. So, what I’m trying to do is make it sensitivity friendly, sustainable, and not too pricey.

You can find Amelie’s style bundles at cybercherryclothes.com and on her Instagram @cybercherryclothes.

Triptych steps on set with Ellen Pritchard for the

BONNY, BONNIE, Bonie, Bony, Boannie, adj., adv., n 1. Beautiful, pretty, fair.

(The definition of Bonnie sourced from the Dictionaries of the Scots Language)

‘Beautiful, Pretty, Fair’; all extremely fitting adjectives for the Graduate Collection of Ellen Pritchard, a 22 year old London College of Fashion knitwear student.

Threads of wonderfully niche Scottish heritage tied together in an array of plaid and buckles. The collection consists of two tops, two skirts and a scarf all featuring intricate plaid patterning.

Pritchard’s inspirations for this project include Charles Rennie Mackintosh, the architecture of Glasgow and Scottish craft.

Pritchard wanted the final garments to be a reflection of herself. This certainly rings true, both in terms of aesthetics and detailing, even down to a pair of ruby gloves pulled from Pritchard’s childhood costume box and ankle socks with Ellen’s initials stitched on at the top. Pritchard says that a lot of her friends find her work very recognisable and often make remarks such as “yeah that’s Ellen!”.

Pritchard explains how her Scottish identity became a main theme throughout her work after moving to London and “reflecting on always being told that I’m not Scottish enough because my mum’s Irish and my dad’s English… people are like, you’re not Irish, you’re English, you’re not Scottish. What the fuck are you?”. Consequently, Pritchard uses knitwear as a vehicle to “rewrite the narrative” and connect with her Scottish roots.

Combined with this, a thread of heavy vintage influence runs through her work. Pritchard finds inspiration for patterns through items she has collected from charity shops and vintage shows, allowing her to “find little treasures then make them for the contemporary market”.

This ties in nicely with Pritchard’s aim to be ethical in terms of sourcing material. All material sourced for ‘Bonnie’ consists of natural fibres

such as deadstock yarn. Impressively, Pritchard acquired a “sponsor from Johnsons of Elgin”, a Scottish weaving mill who gave Pritchard yarn to use in her garments- a nod back to the theme of ‘Bonnie’.

In additon to being a talented knit designer, Pritchard also has short term and working memory which can present challenges for her practise. “You get good ideas and then if you don’t write them down straight away, it’s gone… its either do it right now, write it down or accept your losses” says Pritchard. Sometimes this manifests in struggles with time management which Pritchard says is when the element of mental health plays a role. She “gets really anxious and nervous about things” however, during her work on ‘Bonnie’ she has been experimenting not only with patterns but also with “little tricks” to manage stress. One particular method Pritchard has found to be helpful is “stopping, reflecting, not overworking and just keeping calm within”.

In the context of industry work, Pritchard has had experience managing mental health blips during internships. “it was an awkward conversation to have because you don’t want it to take away from you as a person but then you don’t want to be seen as unreliable” recalls Pritchard on the topic of her second year internship. This highlights the need for mental health to be a more spoken about topic within the fashion and arts industries. Pritchard notes that during this time she “neglected mental health and didn’t take time off when needed”.

When asking Pritchard about the common stereotype that knitting has as an effective stress and mental health soother, she reveals there is actually some truth to the matter. Pritchard describes the physical practice as being “very cathartic”. Where difficulties arise, such maths within the knitting process, Pritchard is able to be highly resourceful and implement tools such as an Excel spreadsheet that works out the maths for her. Pritchard notes that her “approach may be different to some other people” and not “always the way traditional designing goes” but it works for her.

You can find more of Ellen Pritchard’s work on her Instagram @ellenkatherineknit.

the shoot of her final degree collection.

“Reflecting on always being told i’m not Scottish enough”

Gemma Rolls-Bentley; curator and writer, to release new book on the 9th of May, titled ‘Queer Art; From Canvas to Club and the Spaces between’.

In this new release, Rolls-Bentley spotlights some of the most influential queer artists of our time.

From Hockney to Worhol, Tillmans to Bacon, and the stars of queer cinema and the up-and-coming Instagram icons, ‘Queer Art’ has been curated to combine all ends of the spectrum.

Readers will gain powerful insight into the contextual homes of LGBTQ+ art. This includes various chapters that focus on the spaces, bodies and powers that make up the queer art scene. Rolls-Bentley also covers influential socio-political events that have influenced queer art in any degree such as the HIV/AIDS crisis and gay marriage legalisation. Throughout the book, over 150 pieces of artwork are thoughtfully analysed.

Rolls-Bentley’s main practice lies in curation and creative consultancy and is based in London with her wife.

‘Queer Art’ is published by Frances Lincoln and is available from the 9th of May 2024 and retails for £25.

Triptych takes a look at the connection neurodivergent individuals have with electronic

Caroline Cooke (they/them) is a “DJ, music producer and creative practitioner” based in London. Cooke also has a combined diagnosis of ADHD and autism, yet was originally diagnosed with borderline personality disorder, a common misdiagnosis amongst neurodivergent women.

From a young age, Cooke displayed common traits associated with neurodivergence. This manifested itself in special interests. The National Autistic Society describes special interests as “intense interests and repetitive behaviours that can be a source of enjoyment”. Typically, in an autism assessment these are quantified in relation to “collecting rocks or post stamps”, however this is usually more tailored towards the male experience of neurodivergence. For Cooke, dance records proved far more captivating than a Russian stamp.

In the case of Cooke, dance music. Cooke describes this through an anecdote from a conversation with their friend; “I’ve known you for a really long time and the one thing that hasn’t changed is the fact you’ve always liked music; it’s always been your thing”- a lovely sentiment for any musician to hear.

Having always been an “avid collector”, Cooke acquired a “huge collection of music” which they would send to and from their friends during some of the most formative teenage years of their life.

This also resonates with Calem Breegan, a stylist with OCD, anxiety and ADHD who was introduced to Daft Punk through their uncle who DJs. Breegan says “he let me have his Daft Punk 2007 ‘Alive’ tour CD in addition to watching it online “thousands of

electronic music, including interview with up and coming ‘Caroline the DJ’.

Similarly, Benjy Coad, a neurodivergent barista had his first encounter with electronic music at a Zedd concert at legendary London venue ‘Printworks’ at age fourteen.

An intrinsic part of electronic music is the environments in which it is played. Clubs can be a sensory overload nightmare for some of the neurodivergent community.

Caroline feels that during their time behind the decks, they are able to read the room and gain “feedback between audience and artist”, noting also that sometimes it can be difficult for neurodivergent people to emotionally “tap in with the neurotypical world”.

In a practicality sense, being in a booth, away from the crowd can also be helpful to Caroline in order for them to not feel “overwhelmed”. Performing as a neurodivergent DJ can mean using an access rider. This is a document that can be given to a venue that outlines any access requirements. Caroline also feels that the music industry could benefit from encouraging the use of access riders more frequently.

Nevertheless, the actuality of dance music can provide a kind of utopia within otherwise overwhelming spaces. Breegan feels that electronic music can provide “comfort” when having moments of overthinking while trying to enjoy a night out. Likewise, Coad feels that when in a club setting, the music helps him “withdraw” from anything his “neurodivergent brain is doing”. This is most prominent within EDM music as Coad says it has the power to soothe any anxiety and curate a sense of “escapism from reality”.

As much as venues and promoters can try and create accessible environments and spaces for neurodivergent DJs, there are still certain spaces that have room for expansion of accessibility for all.

Just like in any creative industry, networking is a fundamental element to progression, something that Cooke describes as “actually painful” (relatable). As a result of this the “most valuable relationships creatively” for Cooke exist within their “closest creative friends”.

When in conversation to their peers, Cooke says that they can sometimes give what they “would consider constructive criticism might be considered really insulting to someone else”. Of course, this would never be intentional, the NHS states that a trait prevalent in adults with autism can be that they may unintentionally seem “blunt” towards others.

Using their combined autism and ADHD to their advantage, Cooke has a vast “auditory memory”. This comes in extremely handy when it comes to the creation of Cooke’s tracks as they can “hear a full song” in their head before putting pen to paper. While every individual with ADHD have varying experiences, according to a study by Europe PMC, music has the ability to increase levels of dopamine. Lack of dopamine can trigger distraction, therefore, Cooke finds once they start making music they “can do it for hours”.

Music has always been both entertainment and solace but as Cooke, Breegan and Coad explain, it is clear that it also interacts to a beneficial positive degree with the neurodiverse.

You can find out more about Caroline on their Instagram @carolinethedj.

Benny Shakes and Mark Nicholas to co-host critically acclaimed comedy show this summer at Edinburgh Fringe Festival.

‘Disabled Cants’, is described as “a revolving line-up of disabled comedians and friends present and irreverent comedy show” with its only goal being to “make you laugh and park in the disabled bays”. Originally founded in 2022 by Steve Day but now hosted by both Benny Shakes; podcast host and author and Mark Nicholas; comedian. Shakes and Nicholas toured around the UK throughout 2023, hitting hotspots such as Leicester Comedy Festival.

What makes this year’s run of shows particularly exciting is the venue. Bar 50 will act as a “designated hub for disabled shows and networking”. Shakes describes this as “game-changing” particularly as Edinburgh as a city can present “significant hurdles” in accessibility. Yet at these shows, the disabled community band together to have a laugh and “rekindle social connections reminiscent of the vibrant Phab Club gatherings from the 90s” (the Phab Club being a network of social clubs for disabled individuals across the UK).

Originally, Shakes’s goal within the realms of comedy was to be self-employed, yet he now gladly finds himself “aiding other disabled individuals in achieving their aspirations”.

‘Disabled Cants’ is running from the 1st to the 25th of August 2024 in the Laughing Horse at Bar 50 and tickets are available from tickets. edfringe.com.

Since its founding in 1980, Graeae has been a pioneer in the realm of accessible performing arts. Their work has combatted the exclusionary nature of the theatrical industry and now once again they are using their resources to further aid creatives whom are ‘facing barriers in the industry’.

On the 14th of May, Graeae announced the opening for submissions for applications for their Bespoke Artist Development Programme on their official Instagram. They aim to help “develop greater access to regional opportunities across the country” in partnership with eight different theatres across the North, North West, East Midlands and the East of England. Regardless of how far into your career you are, this is a great opportunity for deaf, disabled or neurodivergent theatrics to enrich your practice.

Speaking on the scheme, Laura Guthrie, the Artist Development Manager at Graeae says “creating theatre as performers, writers, directors, producers, technicians or designers is hard but for some of us facing additional barriers it can feel insurmountable. We hope BEYOND will find ways to remove those barriers and set a further 20 Deaf disabled & neurodivergent artists onwards and upwards in their creative careers”. In addition to the enriching support the artists will receive, they will also be able to build career long connections within their industry.

One previous participant in the programme, Gemma Lees commented on the social media post praising the programme as it helped her get stuck back into her career “after a big absence due to mental health” and is now “still working with and connected with people” she met during her time in ‘BEYOND’.

Applications are open until the 27th of June.

Visit Graeae.org for more information.

Hackney based accessible theatre company is looking for twenty deaf, disabled or neurodivergent candidates for their third artist support programme.

Issy Wynn-Carter, 21 year old Creative Direction graduate from London College of Fashion spend the majority of her most formative years struggling through two periods of Chronic Fatigue. According to the NHS, Myalgic Encephalomy or Chronic Fatigue (ME/CFS) symptoms include extreme tiredness that effects everyday activities and cognitive symptoms such as “problems with thinking, memory and concentration”.

Eloise: Can you tell me a little bit about your background as a creative?

Issy: I have an academic background in creative direction, but I’ve always been more into creative things over academic subjects. When I was young, I thought I was going to be a fashion designer. So I do like all these awful outfits and think like I was going to be the next big thing. But I’ve always known I’ve like been into fashion, art and everything. Recently I’ve gained more interest in film, which led me to make my own film.

Eloise: When your chronic fatigue begin?

Issy: A few months into secondary school I started getting really bad stomach pains and had no idea why. Every doctor I would visit would say different things like food poisoning or juvenile arthritis which was confusing because none of the symptoms I had matched up with that. It was sort of this mystery illness.

Eloise: How did you end up getting diagnosed?

Issy: My parents took me to a private doctor even though we couldn’t afford it. They carried out an endoscopy and found hundreds of ulcers in my stomach, which I was told if they hadn’t have found, they could have turned septic. As a result of the ulcers, I then got chronic fatigue.

Issy Wynn Carter shares her story of adolescence navigating chronic fatigue as a creative.

Eloise: How long did you suffer with chronic fatigue for?

Issy: Well there’s no definite timeframe that chronic fatigue and no cure. So it can span from three, five, ten to how ever many years. At first, my symptoms improved after about two years. However, I then relapsed at the beginning of my GCSEs.

Eloise: In what ways did this effect your development mentally and socially?

Issy: My social setting was just being at home and because of that my anxiety just got crazy. I also struggled with depression during this because I wasn’t interacting with people which was something I would normally love to do. It was a never ending cycle because I was too socially anxious to go into school because I was never in. I don’t think I would have bad anxiety now if I hadn’t have had chronic fatigue. Even when I was in a university setting it kind of took my back to that place mentally of being anxious in school.

Eloise: During this time in your life, what was your relationship with creativity like?

Issy: Art was my favourite thing to do. I enjoyed it so much because I think it was almost a way of dealing with the health side of things I couldn’t control. It also didn’t take as much out of me in comparison to maths and science-based subjects. My art teachers at the time always told me to use what I was going through to express your feelings surrounding it. I think that made me more experimental with what I wanted to do. I remember being the only one in my class who did a sculpture as a final outcome whilst everyone else did paintings, but it made me more determined to do what I wanted.

Eloise: What kind of emotions were you able to express through art?

Issy: At the time, I felt quite alienated and alone amongst my peers. I also didn’t know who I was because I spent some of the most fundamental years of my life in my room. Being creative was an amazing outlet and I started to use art as a way to portray messages that were important to me and that I was passionate about, which I’ve carried through to my practise today.

Eloise: Have you been able to reflect on your experience with chronic fatigue through your work now?

Issy: I think I have a tendency to push out that time in my life out of my brain. It’s almost as though those five years never happened. My sister will ask me ‘do you remember this?’ and I never really do. But I think it has changed my outlook on my creative practise.

Eloise: In what way?

Issy: I see life a little differently, like through a different lens. I don’t look at life like some magical thing where nothings ever happened to me. Sometimes this can hold me back because I can feel like I’m not good enough in the industry. I remember when I was doing an internship at Wonderland Magazine and I found myself overthinking things a lot or feeling like the work was too much for me.

Eloise: What advice would you give your younger self going through chronic fatigue?

Issy: I wish I didn’t care as much about what people thought. I was so wrapped up in what my peers were saying but in reality, they probably didn’t even care that much. I was going through something no one else my age I knew was and children are just not as empathetic then.

Eloise: Do you think there’s anything within the arts industries that could be done to help people going through similar things?

Issy: There definitely needs to be more knowledge about it, I still think its something a lot of people don’t know about. It’s weird how life works, I remember when I got diagnosed, a lot of adults thought I was making my symptoms up. One messaged my mum for advice years later as her daughter then got chronic fatigue. I think if there was more knowledge there wouldn’t be as much judgment, and I think that’s important within an industry context for people to understand.

You can find Issy’s work at @iwcprojects on Instagram.

In a city that is seemingly so focused on what lies ahead, the London art scene is looking back.

Three new exhibitions, ‘Pacing The Void’ at Alma Pearl Gallery, ‘Softer, Softest’ at Guts Gallery and ‘Travelling Memories’ at The Modern Showroom are showcasing the art of memory (quite literally). Across both exhibitions, contemplations of individual, collective and nostalgic memory are complimented by various themes of nature, spirituality, and human connection.

The act of memory is arguably more complex in this day and age. Intertwined with digital ephemerality of fleeting moments, it seems refreshing, almost comforting to have spaces that host these prisms of pondering memory in a world that is so future focused.

Nestled at the intersection of Regents Canal and the Kingsland Basin lies Alma Pearl, a female owned gallery that has hosted numerous beautifully eclectic exhibitions since its opening last year.

Showcasing a vast variety of different cultures and drawing on ideologies, the private viewing offers a unique viewing experience which is ideal for taking the time to bathe in the ethereality of the work.

’Pacing the void’ is a dual artist exhibition at Alma Pearl Gallery. Nai-Jen Yang and Xinran Liu both explore the themes of spirituality, nature and of course, memory. The ominous title, ‘Pacing the Void’ is a direct reference to the writings of Wu Yün whereby a transcendent place beyond heaven is considered and contemplated.

Gallery director, Celeste Baracchi tells Triptych about the artist, stating that “in their culturally hybrid practices, each develops a unique painterly vocabulary rooted in Asian philosophical and religious traditions, while combining Eastern and Western modes of abstraction”

One of the first paintings displayed as one enters the gallery is ‘We Sit Around

The Table’ by Xinran Liu whereby she recalls a still life-esque tablescape from memory. Through leaving areas of the canvas as negative space or filling parts with abstract brush strokes, a strong sense of disjointed recollection is conveyed poetically. Soft hues of pastel nautical blues and greens are combined effortlessly with a background of warm beige and greys. Where memory fails the artist, the lines of the brushstrokes become more frantic and sporadic yet continue to hint to what may have been without fading memory.

Towards the back of the gallery, ‘Listen’ an oil painting by Nai-Jen Yan hangs proudly on the wall. This abstract piece, described as ‘tranquil’ by one attendee, is anchored by soft brush strokes of different varieties of beingness. Depth is created through varying lengths and tones.

Thomas, a spectator at the opening describes the exhibition as a whole as “gentle”. ‘Pacing the void’ is a must visit for anyone looking to find the calm amongst the storm.

Guts Gallery, founded by Ellie Pennick is a Hackney based gallery with a desire to spotlight artists sometimes overlooked in the industry. In addition to the motif of memory, ‘Softer, Softest’ draws on themes of human connection in the physical sense. Beautifully diffused snapshots of moments are documented throughout the exhibition, each piece paying copious amounts of complements to the others. The exhibition opened on the 26th of April with a celebration boasting an outstanding turnout and runs for a little under a month until the 21st of May.

Laura Footes, a Margate based artist living with Crohn’s Disease exhibited her take on the theme of softness and memory through her painting titled ‘Spring Awakening With Two Entwined Trees’. The 120 cm x 120 cm canvas depicts a tranquil image of individuals in a bed. On first glance, it is unclear as to how many people are in the double bed with a large headboard, however, it is almost unclear where the tangled sheets end and the limbs of the subjects begin. This leans into the ambiguity as every second longer the viewer immerses themselves in the painting entranced, a new body appears.

If one were to picture a dreamscape in their mind, the colour purple would occur somewhere in their mind’s eye. Footes channels this through a gradient scale from the palest lilac to the deepest indigo. Combined with the bold brush strokes, the colours work together to create dimension and shadow, almost like a conversation that flows perfectly.

Speaking on her work, Footes says she “wants the viewer to see or feel something in this painting that resonates with them, perhaps it triggers their own memories” as she wants all her work to be an “open ended dialogue with the viewer, offering micro catalysts into their own memories and emotional landscape”.

Pink’ is a thoughtful study of nostalgia and reflection. Liem tells Triptych her inspiration was based upon her visits back home to Singapore and her “illusions” whilst there. Liem also notes that she wanted to “use this painting as a way to.. explore more fluidity and abstraction”. The abstract elements of the painting are brought in through the distortion of the buildings in the background and the ambiguous figure that takes centre stage.

Taking a less abstract route, Alexandra Rubinstein exhibits her painting titled ‘Bloody Mary’. Unlike the majority of pieces in ‘Softer, Softest’, ‘Bloody Mary’s’ medium takes inspiration from its name (or visa versa). Menstrual blood is used rather than oil paint like many of the paintings ‘Bloody Mary’ sits alongside. The use of menstrual blood aims to confront the audience by creating this paradox of the perceived uncleanliness and the contrasting softness and beauty that is created through the delicate and fuzzy texture created by a spray gun. The content of the painting is closely intertwined with the medium, this being a depiction of a woman in a style reminiscent of a Virgin Mary mural.

The third and final memory centred exhibition to grace the London art scene is ‘Travelling Memories’ at The Modern Showroom in Hoxton from the 16th to the 19th of May. Curated by Yanyi Chen and Qinle Jin from the Royal College of Art, ‘Travelling Memories’ showcases the work of eighteen artists from seven different cultural backgrounds in various mediums. Chen describes the goal of the exhibition as being to spotlight “how our root memories are recalled, adapted and evolved”.

Melodie Shi, exhibition goer tells Triptych about her personal favourite piece from ‘Travelling Memories’; “Cuckoo Clock by Qibai Ting is a unique, sculptural piece with artefactual qualities”. The piece is comprised of various familiar objects such as a small backgammon board and a ceramic chicken. Combined, these found objects come together to create a sense of home comfort and nostalgia. Artist, Qibai Ting describes her inspiration as being from “the visual impression of Vanitas ‘Still Life’ painting” yet her physical manifestation of this “creates a place where she can find memories”.

By nature, we are nostalgic beings. Human memory so clearly has such an influence in modern art today, as demonstrated by ‘Softer, Softest’, ‘Pacing The Void’ and ‘Travelling Memories’. Curator, Yanyi Chen believes that “art is just one of the ways we express ourselves, but it authentically captures how our root memories evolve”. This, I believe perfectly describes the role of memory in modern art.

I see an old familiar in the corner of the room Slow smile and enveloping arms outstretched.

My friends and family do not see it moving with me, Side stepping through crowds and stalking in my shadow. Invisible, To everyone but me.

No beeping machines or slow drawing needles can find a trace, It evades penetrating scans where it rests below the skin.

It’s my word against its, And it’s such a quiet creature.

It makes silent demands, my imaginary friend.

I see myself in the middle of the room, People all around me and ready to take my hands.

But I don’t feel myself in the middle of the room, Watching from afar I am on a different plane.

Present through a shimmer in time, Not in mind.

No gentle words or positive smiles clear out its fingers, It rolls like fog, wrapping around my life, turning every moment grey.

Round my brain, round my fists, Round my lungs, round my words,

It wants to take ownership, My imaginary friend.

I feel it settle down beside me in bed, Familiar whispers and warm darkness.

In the room next door I hear laughter and the TV, Roaring with life, people connect in the screens glow.

I can’t call out to them from in here, In my internal state.

No warriors or wizened friends can break the hidden chains, What refuge can I seek from it who lives inside.

It’s just us two together intertwined, Now I define myself in its image.

It is who I have become, My imaginary friend.

Words by Daisy Riley, @weak_wrists_r_us on Instagram.

Jasmine Lockett is an accomplished 20 year old second year fine art student at Liverpool Hope University.

In 2015, Lockett was diagnosed with a brain tumour. Despite the low-grade nature of the mass, the removal of it is not possible due to its location. Lockett spent three months in America undergoing treatment. As a result, Lockett lost her pituitary gland function and now has to take hormone replacements.

Alongside her treatment at age 12, Lockett had access to art therapy sessions. During these sessions, Lockett would be given an activity that involved ‘repetitive yet meditative’ processes. Elements of this has translated into Lockett’s practise today in forms such as mark making.

Lockett explains how her diagnosis “tapped into something” inside of her, making her realise she wanted to pursue art. After her treatment, Lockett found that some cognitive issues cropped up upon returning to school that made typically academic subjects more challenging. Lockett describes how not only was art the one subject she felt she could excel in, but it also helped her to process the trauma she had just experienced. Through painting and drawing she was able to translate how she felt mentally onto a page.

Since Lockett’s path into fine art began, her style and influences have evolved infinitely. In the beginning, Lockett focused heavily on hyper realism and “skill based” art. However, by the time she reached her final year of A Levels, Lockett had started to settle into her own personal style of art, still focusing on figurative art but combining some abstract elements such as experimenting with colours.

In her first year of university, Lockett began to dabble in more ambiguous styles of art. Lockett says she now likes to “keep things quite loose and gestural” to allow for the audience to make their own judgments about the work and relate it to their own experiences.

One piece in particular (and Lockett’s favourite artwork so far) encapsulates this perfectly. ‘Pushing Up Daisies’ is a 183x143cm acrylic painting that centres around Lockett’s experiences before, during and after her diagnosis with three figures. Lockett tells Triptych how in the painting, the first figure representation of her pre diagnosis during a time

where she was misdiagnosed; “she’s got like these weird hands pressing down on her head, which symbolizes like all the headaches that I had”. Referring to the second two figures, Lockett says “the one next to her on the left was me during treatment and her head is kind of floating away”, representing a sense of dissociation. Lockett says the third figure with six arms making daisy chains, “represents me now, keeping busy with my hands and working through everything”.

For Lockett, daisies represent regrowth and rebirth, therefore she chose to incorporate these as a tribute to friends she made and lost during treatment. She draws inspiration from one picture of her, her siblings and one of her childhood friends playing outside making daisy chains.

Touching on the topic of accessibility within the art industry, Lockett feels as though disabled people should be

more considered in the context of language accessibility. Lockett notes that particularly within exhibition spaces, elements such as “image descriptions” should be more heavily implemented in order to make the ”visual language” of art more available to everyone. Lockett aspires to make art spaces more accessible from inside the industry.

As Lockett enters the final year of her degree, she also sets her sights on giving back to the practice of art therapy that enriched her development so much. Lockett was primarily treated at Alder Hey Children’s Hospital and would love to work “hands on” in a capacity there. Lockett also notes the idea of providing art therapy to adults who may not have access to it.

To see more of Jasmine Lockett’s work, visit @jasminelockettfineart on Instagram.

Find the Triptych Podcast, linked on our Instagram, @triptychmag_ to listen to an exploration of art therapy with registered art therapist Katrina Hudson.

Neurodivergent curator, Iris Sirendi shares her experience with Curating For Change programme.

Curating for Change is an organisation based throughout England that facilitates leading roles for deaf, disabled and neurodivergent individuals within the gallery and museum curation sector. There is a dire lack of representation for these groups in the context of curation and Curating for Change aim to combat this. A study by Arts Council England found that only 4% of museum employees are disabled. Every eighteen months, Curating for Change offer a fellowship programme in partnership with various museums and galleries across the country.

First generation Estonian migrant and University of Manchester American Studies graduate, 23 year old Iris Sirendi has recently finished her placement at the Museum of Liverpool. Sirendi was first introduced to the idea of curation through a module on her undergraduate course where she studied the use of digital elements in museums and the ways in which they can aid accessibility. During this, Sirendi noticed that there is “a gap within arts provisions” whereby a lot of accessibility initiatives in museums and galleries “seem to be targeted towards kids”. While mostly well intended, this can create room for ableism in the form of infantilisation. This concerned Sirendi as having experience with OCD, ADHD and Dyspraxia.

Curating for Changed has opened Sirendi’s eyes to “how much disabled and neurodivergent curators are capable of and how much we can achieve when people just give us a bit of time and space”.

The programme really allows the excellence of disabled and neurodivergent curators to shine. Even down to the interview and training process, which Sirendi says can often be “quite isolating” and clinical.

In month one out of eighteen, Sirendi began sifting through the collection of archives at the Museum of Liverpool. This led to the discovery that there wasn’t enough that “spoke to the lived experiences of the disabled and neurodivergent”. However, as she delve deeper into the archives of the museum, more and more came to light and Sirendi was tasked with exhibiting her findings in “an accessible” manner.

Off the back of this, Sirendi started to curate and source items for an exhibition titled ‘Assistive Technology: What it means to us’.

A poignant example that Sirendi notes is a bright pink cane belonging to engagement manager Kelly Barton. Barton was born blind and Sirendi began to notice upon her visits to the museum as part as her role as engagement manager, that Barton would without fail match the colour of her cane to her outfit. Barton asks her family members which cane out of her “umbrella stand full of coloured canes” would go best with her clothing that day. Speaking to the Museum of Liverpool, Barton says she feels “so comfortable using a pink cane” as it is an “extension” of her and expression of her personality. To her it’s an “accessory not just a mobility aid”.

Sirendi feels that voicing the stories and experiences of disabled and neurodivergent people is one of the most important elements of encouraging accessibility and she was able to do exactly that. Through using objects from the museums archive, she created a trail throughout the exhibition voicing the stories of fourteen disabled individuals. This is now immortalised on the Museum of Liverpool’s website. Having a digital element people can digest from home is something Sirendi feels to be important in the context of accessibility.

Looking forward, Sirendi tells Triptych she would love to curate an exhibition focused on the “history of disability activism”, exhibiting events such as disability cuts protests. Additionally, Sirendi adds that she “loves the Moomins”, the fictional works of Swedish author Tove Jansson and would be interested in curating an exhibition all about them.

Visit Liverpoolmuseums.org.uk to see archival objects curated by Iris Sirendi.

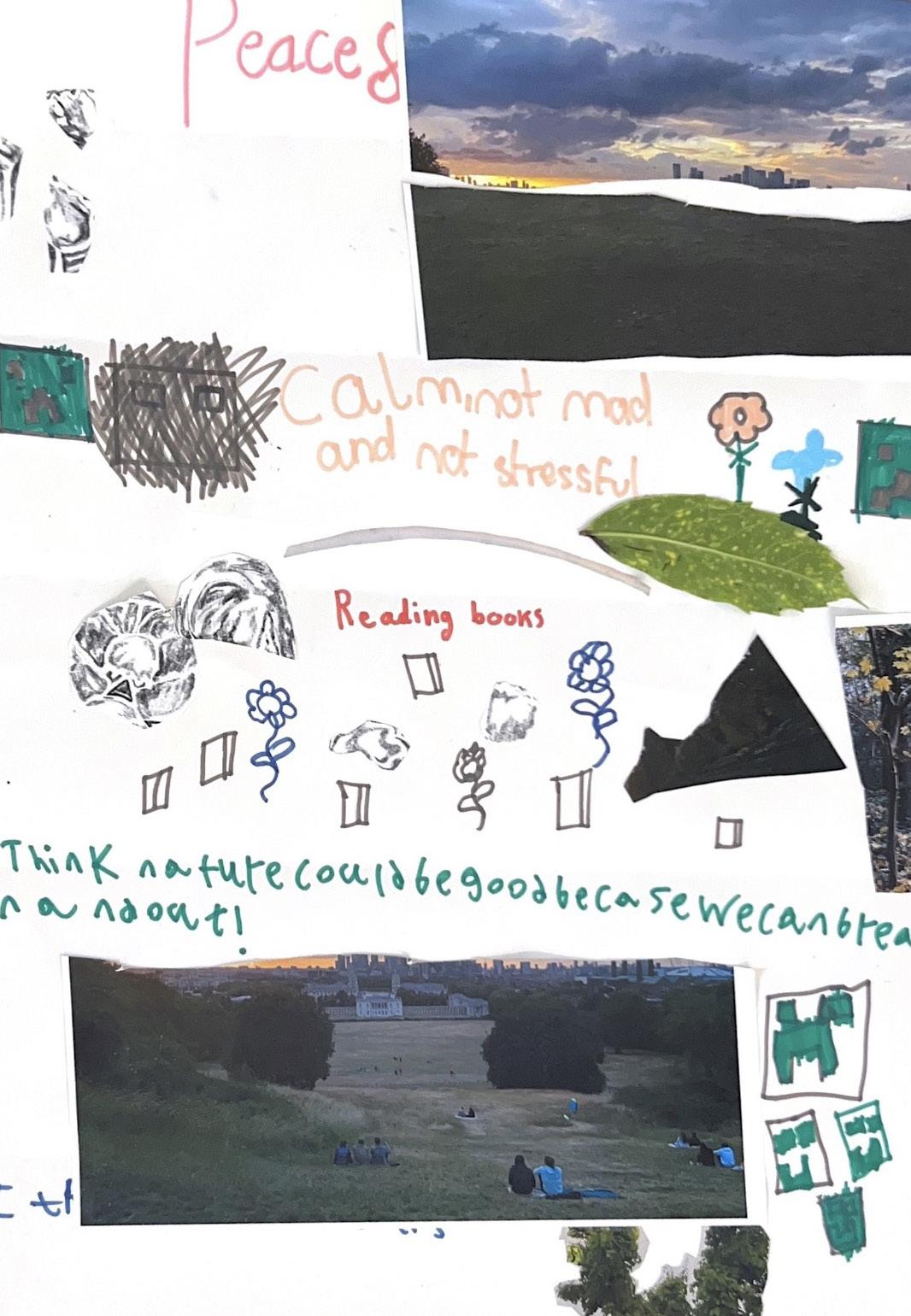

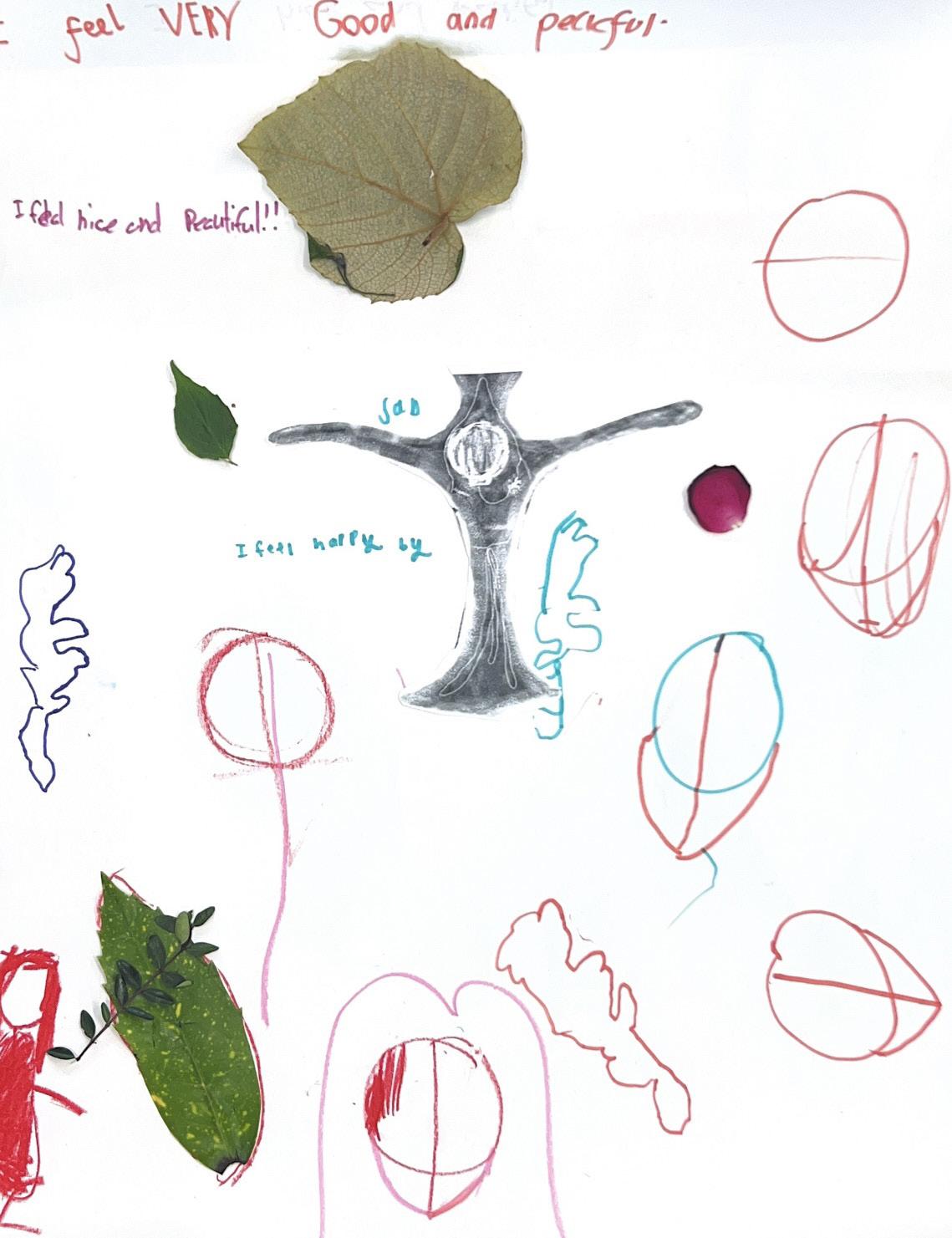

An exploration of the intersection between art, nature and human feelings through a workshop held by illustrator Camille Bolasco and Triptych magazine.

‘Touchsomegrass”, a common phrase circulated on the internet, anonymous Tiktok keyboard warriors telling a complete stranger to go outside from the comfort of their bed whilst completing their nightly doomscroll. But what were to happen if we took their advice and actually touched some grass?

Nature can be a powerful tool to expand creative horizons. According to Extinction Rebellion, research shows that “a four-day nature hike improved creative problem solving by up to fifty percent”. However, a study by the National Trust, accessibility to green spaces acts as a large barrier for children to get outside.

In an urban environment, such as the one where South Tottenham Primary School resides, finding nature dense areas can be challenging. Therefore, Triptych teamed up with illustrator Camille Bolasco to help demonstrate to school children the importance of connecting with nature and its relationship to art. Bolasco features the theme of nature throughout her work. “Most of my art acts as a way for people to escape, whilst appreciating simpler things, such as nature” says Bolasco, “living in a busy city nature brings me peace and inspires the imagery in my art”. Mrs Vara, a primary school teacher from South West London notes that through utilising the medium and themes of nature within art, “children can all enjoy the same thing and gives them something to relate to each other about”.

On Tuesday the 14th of May, we hosted a workshop combining the elements of art, nature and emotions.

The workshop consisted of three exercises (we encourage you to also try these at home).

1. Firstly, as a warm up task, we provided images of nature around London and told the children to draw their emotional responses to the images.

2. Secondly, we placed natural objects such as flowers, leaves and shells on each of the tables and simultaneously played a forest soundscape. Once again, we asked the children to draw their feelings towards the materials and sounds.

3. The third exercise on the list featured a collaborative element. We instructed the children to write on a large A1 piece of paper one word each to describe their connection to nature. Once written, they were told to fold over directly where they wrote and pass the paper to the next person to write on. The outcome of this was five different collaborative poems.

4. Finally, on the same paper as the poems, we gave the children free reign to draw, cut, stick using the array of images, flowers and some of Belasco’s’ own illustrations.

Some poinigont words from the poems created include:

“Calm,notmadandnotstressful.”

“Ithinknaturecouldbegood because we can breathe in and out.”

“IfeelVERYgoodandpeaceful.”

Sometimes, all we need is a reminder of the small treasures that surround us, wether that be in a local park or a remote nature reserve. So maybe there is some truth in touching some grass, at least in the context of fostering and enhancing creativity.

Find more of Camille Bolasco’s work on Instagram, @britegirl_.

The responses we received from the children echoed the importance of children to implement nature in their lives as a tool for creativity and well being.

As Bolasco and I bustled around the room, we guided the children through their drawings of arrays of natural elements such as rivers, trees, flowers, and rainbows.

Please draw how you feel after reading Triptych.