Volume 14, Summer Issue

Que faut-il à ce cœur qui n’était que silence, Sinon des mots qui soient le signe et l’oraison,

Et comme un peu de feu soudain la nuit, Et la table entrevue d’une pauvre maison ?

Yves Bonnefoy, ‘Qu’une place soit faite...’

The

Trinity Journal of Literary Translation (JoLT)

This publication is funded by the DU Trinity Publications Committee.

The publication claims no special rights or privileges,.

All serious complaints may be directed towards chair@trinitypublications. ie or Chair, Trinity Publications, House 6, Trinity College Dublin, Dublin 2. Appeals may be directed to the Press Council of Ireland.

Get involved with Trinity Publications through Facebook, Twitter and Instagram or email secretary@trinitypublications.ie

Volume 14, Summer Issue

“REFUGE”

‘I know the world is bruised and bleeding, and though it is important not to ignore its pain, it is also critical to refuse to succumb to its malevolence,’ wrote Toni Morrison in a 2015 feature in The Nation, discussing the role that art and literature play in the face of despair. With the theme of ‘refuge’, my aim was to encourage reflections on that same refusal to succumb, on the way we find comfort as we navigate moments of crisis both at a personal and a collective level: not turning a blind eye to hardship but seeking environments that restore our faith and allow us to exist freely. Where do we go, to whom do we turn when sorrow and hopelessness overwhelm us?

The term ‘refuge’ derives from the Latin fugere, ‘to flee’: a space that wards off danger, a safe haven into which one can escape. The works featured in this issue invite us into their many sanctuaries, from communities and tranquil landscapes to the intimate realms of memory and imagination, where hope is found amidst fear, grief, and uncertainty. Several translations consider the crucial theme of migration and forced displacement, construing the act of taking refuge as one of exceptional courage and resilience. The unifying thread is a deeply rooted willingness to persevere despite and against adversity, to survive and find replenishment.

I am immensely grateful to all the people whose thorough work and enthusiasm brings JoLT to life. Above all, to the editorial team, whose patience, creativity, and skill I can always count on. To our faculty advisor, Dr Peter Arnds, for his support and good counsel. To Keith Payne, Hao Yang, Giorgia Carli, and Dr Jana Van Der Ziel Fischerová, who helped us review submissions in languages we didn’t know. To my predecessor, Julianna, who eagerly imparted her invaluable knowledge. A very special thank you to the translators and artists who contributed to this issue.

I hope that JoLT, too, can be a place of refuge for you.

Ioana Răducu

Editorial Staff 2025/26

Editor-in-Chief

Ioana Răducu

Deputy Editor

Monica Elena Grigoraș

General Assistant Editors

Nina Stremersch

Jes Paluchowska

Layout and Design Editor

Odhran Killally

Art Editor

Hanna Lujza Molnár

Language Editors

Helena Gelman

Jules Nati

Maike Bergfeld

Ruairí Goodwin

Douce d’Andlau

Nell Gardiner

Lukian Pudliak

Faculty Advisor

Dr Peter Arnds

Sophie Quinn, Outskirts

Cover Art by Hanna Lujza Molnár

Editorial Outskirts

Photograph by Sophie Quinn

‘The Lake Isle of Innisfree’

English-Irish Translation by Pól Ó hÍomhair

‘Recueillement’

French-English Translation by Alyssa Salzberg

‘Carmen XXXI’

Latin-English Translation by Charlie Judd

‘Hospoda u cesty’

Czech-English Translation by Maria McChrystal

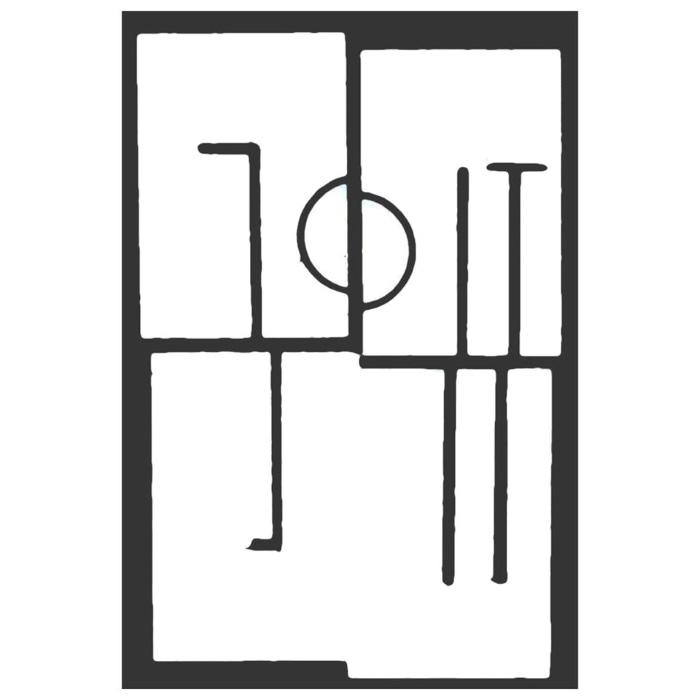

Spontaneous

Photograph by Maja Hamidovic

La Luna e i Falò

Italian-English Translation by Jules Nati

‘Fremde’

German-English Translation by Laura Marmion

‘[Resumir o traçado dos mapas]’

Brazilian Portuguese-English Translation by Alice Osti Magalhães and Jenny Marshall Rodger

A Green Procession

Photograph by Emily Spangler

My Sister

Photograph by Emily Spangler

Yiddish-English Translation by Aodhán Murphy

‘Things You May Find Hidden in My Ear’

English-Irish Translation by Aaron Groome

‘Mapa’

Polish-English Translation by Jes Paluchowska

‘El Hombre Imaginario’

Spanish-English Translation by Natalia Chotzen

‘Adiós, ríos; adiós, fontes’

Galician-Irish Translation by Nathan Harpur

Achill Island

Photograph by Martha Downes

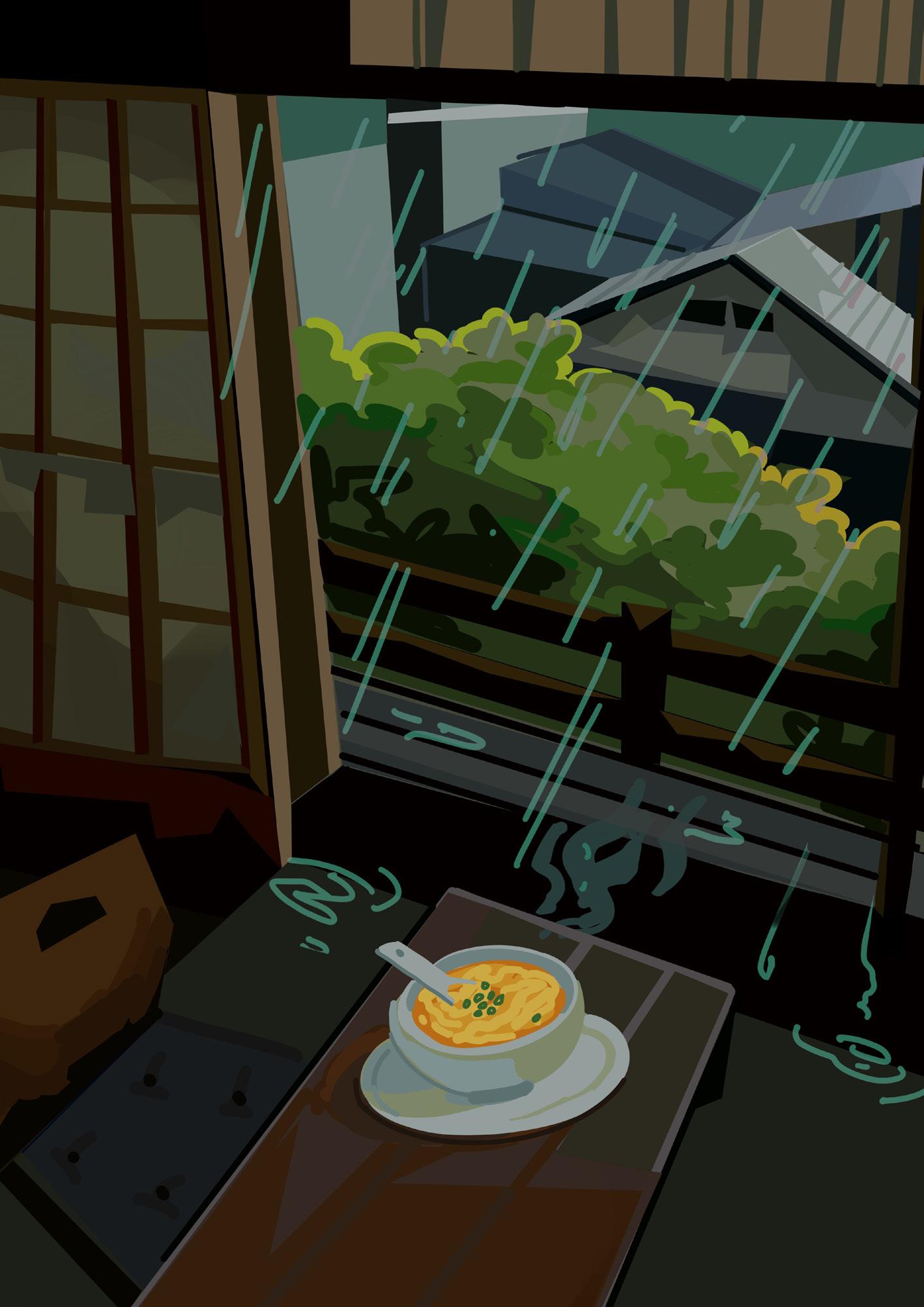

Solace in the Rain

Art by Hanna Lujza Molnár

‘房間’

Chinese-English Translation by Fion Tse

‘Daidža Bahro mislio da četnici ne ubijaju ribolovce’

Bosnian-English Translation by Ena Selimović

‘Cafè-refugi’

Catalan-English Translation by Richard Huddleson

Aeneid VI lines 134-155

Latin-English Translation by Dr Kevin Kiely

‘Mondnacht’

German-English Translation by Cem Heckmann

‘De scólzh’

Venetian-English Translation by Greta Chies

‘Только детские книги читать’

Russian-English Translation by Greta Chies

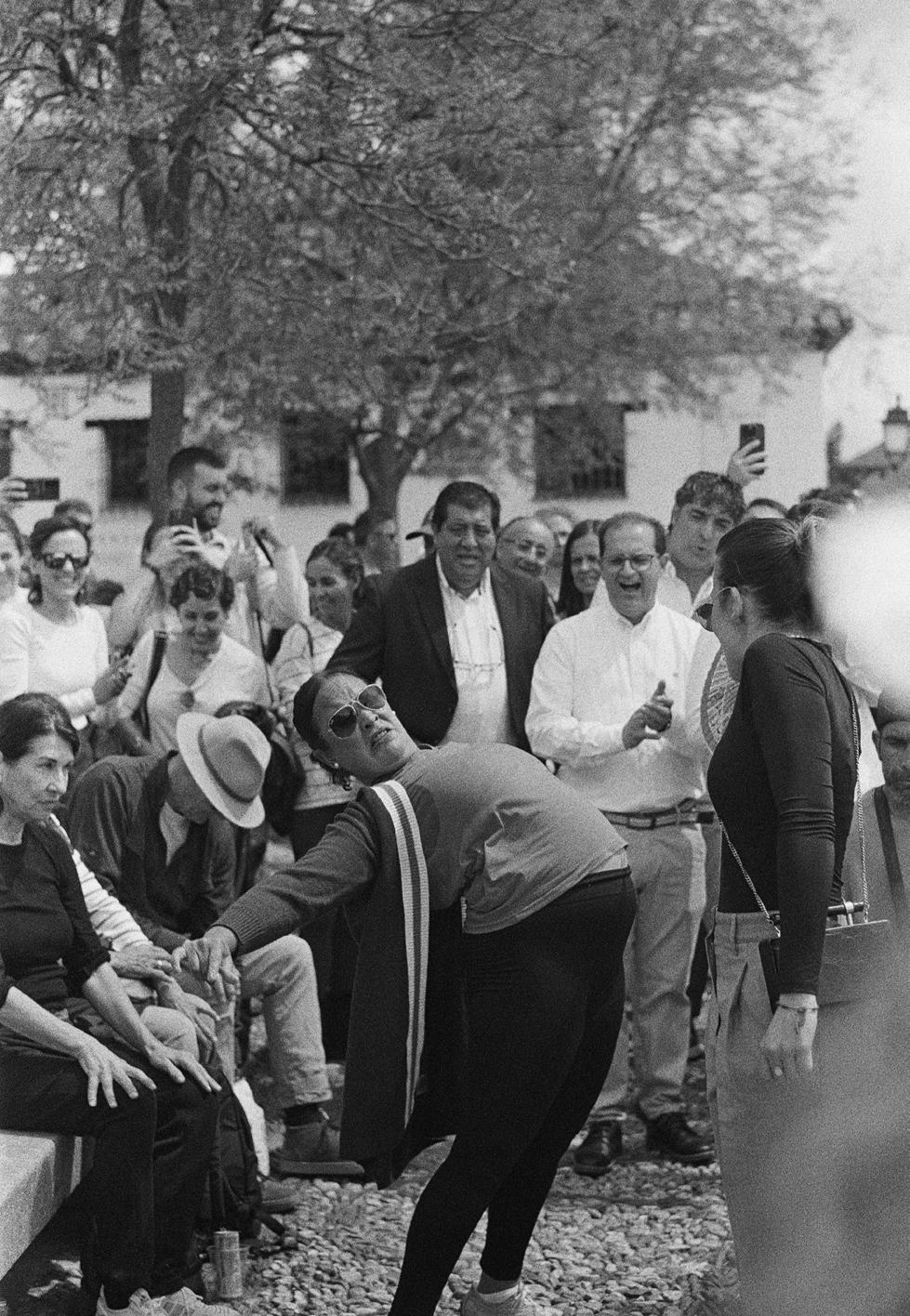

Retiro Park

Photograph by Maja Hamidovic

Together

Photograph by Maja Hamidovic

‘BALANG ARAW, IUUWI KITA SA AMING BAYAN SA NEGROS, SA PANAHON NG ANIHAN’

Filipino-English Translation by Eric Abalajon

‘IL GELSOMINO NOTTURNO’

Italian-English Translation by Martina Stoilovska

Two Poems by Henri Meschonnic

French-English Translation by Gabriella Bedetti and Don Boes

Contributors

The Guardians of Peace

Photograph by Emily Spangler

The Lake Isle of Innisfree

W. B. Yeats

Dán é seo a chuireann síos ar an dtearmann a aimsítear i bhfad ón mbaile, agus an tsíocháin a eascraíonn ó néalta na n-áiteanna seo a shamhlaítear. | This is a poem which describes the refuge found far from home, and the peace which comes from visions of these imagined places.

I will arise and go now, and go to Innisfree, And a small cabin build there, of clay and wattles made; Nine bean-rows will I have there, a hive for the honey-bee, And live alone in the bee-loud glade.

And I shall have some peace there, for peace comes dropping slow, Dropping from the veils of the morning to where the cricket sings; There midnight’s all a glimmer, and noon a purple glow, And evening full of the linnet’s wings.

I will arise and go now, for always night and day I hear lake water lapping with low sounds by the shore; While I stand on the roadway, or on the pavements grey, I hear it in the deep heart’s core.

Oileán Loch Inis Fraoigh

Translated by Pól Ó hÍomhair

Anois éireod is raghad, amach go hInis Fraoigh, Is bothán beag a thógaint ann, de dhéantús cré is caolaigh; Beidh naoi líne pónairí agam ann, coirceog do bheach na meala, Agus cónód i m’aonar i bplásóg na mbeach glórach.

Agus beidh ruainne suaimhnis agam ann, óir is mall a shileann é, Ag sileadh ó chaille na maidine go dtí a gcanann an criogar;

Ansan tá breacsholas sa mheán oíche, agus luisne corcra sa mheán lae, Agus tráthnóna lán le sciatháin na gleoisí.

Anois éireod is raghad, toisc gur de ló is d’oíche

A chloisim uisce locha ag slaparnach le fuaimeanna ísle cois cladaigh; Agus mé im’ sheasamh ar an mbóthar, nó ar na cosáin liatha Cloisim é i smior domhain an chroí.

French

Recueillement

Charles Baudelaire

In this poem, the listener (Sorrow) is urged to take refuge from the cacophony of the day and rest safely in the night. This translation retains the syllable count and rhyme scheme of Baudelaire’s alexandrine verse.

Sois sage, ô ma Douleur, et tiens-toi plus tranquille. Tu réclamais le Soir ; il descend ; le voici ; Une atmosphère obscure enveloppe la ville, Aux uns portant la paix, aux autres le souci.

Pendant que des mortels la multitude vile, Sous le fouet du Plaisir, ce bourreau sans merci, Va cueillir des remords dans le fête servile, Ma Douleur, donne-moi la main, viens par ici,

Loin d’eux. Vois se pencher les défuntes Années, Sur les balcons du ciels, en robes surannées, Surgir du fond des eaux le Regret souriant ;

Le soleil moribond s’endormir sous une arche, Et, comme un long linceul traînant à l’Orient, Entends, ma chère, entends la douce Nuit qui marche.

Translated by Alyssa Salzberg

Be softer, o! my Sorrow, come, fall still at last. Your Evening has returned; he drifts; see, here he sleeps; Shadow-laden mist holds the city in its grasp, Deliv’ring some their nightmares, gifting others peace.

Meanwhile the mortals, staggering and loud, Cringe beneath the whip of that torturer, Pleasure, Go, gather your penitence from the servile crowd My Sorrow, take my hand, come away, farther

far from them. See how the Years bend, now retired, on the balconies of the sky in their robes so tired; Regret surges smiling from the deepest rivers;

The sun goes dying to sleep beneath an arch, And, like a shroud trailing West, coming hither, Listen, my dear, to the sweet Night’s march.

Latin Carmen XXXI

Gaius Valerius Catullus

Song 31 was written to celebrate Catullus’s homecoming from the eastern province of Bithynia, where he worked on the staff of a military commander. He celebrates returning from faraway labor to his family home on the beautiful Lake Garda, no longer homesick or stressed, but finally safe and comfortable.

paene insularum, Sirmio, insularumque ocelle, quascumque in liquentibus stagnis marique vasto fert uterque Neptunus, quam te libenter quamque laetus inviso, vix mi ipse credens Thyniam atque Bithynos liquisse campos et videre te in tuto. o quid solutis est beatius curis, cum mens onus reponit, ac peregrino labore fesi venimus larem ad nostrum desideratoque acquiescimus lecto? hoc est, quod unumst pro laboribus tantis. salve, o venusta Sirmio, atque ero gaude gaudente; vosque, o Lydiae lacus undae, ridete quicquid est domi cachinnorum.

Sirmio, my darling of all insulae and peninsulae, of all Neptune’s offerings in clear lakes or open sea, so freely, so happily I gaze upon you, barely myself believing I’ve left behind Thynia and Bithynian fields, nor that I’m safely seeing you. Oh, what’s better than worries released when my mind lets go its work and I come home from foreign labor and stretch out on my long-desired bed? This and this alone is worth such exhaustion. Hello at last, gorgeous Sirmio; rejoice in your rejoicing master. Oh, Lydian lake-waves, laugh every laugh you’ve got in store.

Translated by Charlie Judd

Czech Hospoda u cesty

Ivan Wernisch

In this poem, the author finds refuge in the form of an al fresco pub, allowing him to bask in the summery atmosphere. I translated the short verses in the form of two limericks, which both emphasize the poet’s desire for refuge, and remain overarchingly loyal to the source text.

V altánu u potoka, Ve vůni borové smůly a zvětralého piva, Chtěl jsem jen posedět

Navždycky

V lese skřípal strom V mechu a mateřídoušce kotvila má lod.’

© Druhé město, 2014

English

Pathside Pub

Translated by Maria McChrystal

In the summer-house by the creek I wanted to sit and to steep in pine-scent sap-secretions and beer scents- well-seasonedwhile in the forest, a tree creaked.

Forever and for all of time I simply wanted to recline while likewise, my boat (now ashore, not afloat) lay anchored in moss and in thyme.

Maja Hamidovic, Spontaneous

Italian La Luna e i Falò

Cesare Pavese

The author describes what it feels like to return to where you grew up after having been abroad. It perfectly encapsulates the sense of refuge only a hometown can give: the security of being able to leave, knowing there will always be a place to go back to.

Tutti quegli anni bastava che alzassi gli occhi dai campi per vedere sotto il cielo le vigne del Salto, e anche queste digradavano verso Canelli, nel senso della ferrata, del fischio del treno che sera e mattina correva lungo il Belbo facendomi pensare a meraviglie, alle stazioni e alle città.

Così questo paese, dove non sono nato, ho creduto per molto tempo che fosse tutto il mondo. Adesso che il mondo l’ho visto davvero e so che è fatto di tanti piccoli paesi, non so se da ragazzo mi sbagliavo poi di molto.

Uno gira per mare e per terra, come i giovanotti dei miei tempi andavano sulle feste dei paesi intorno, e ballavano, bevevano, si picchiavano, portavano a casa la bandiera e i pugni rotti. Si fa l’uva e la si vende a Canelli; si raccolgono i tartufi e si portano in Alba. C’è Nuto, il mio amico del Salto, che provvede di bigonce e di torchi tutta la valle fino a Camo. Che cosa vuol dire? Un paese ci vuole, non fosse che per il gusto di andarsene via. Un paese vuol dire non essere soli, sapere che nella gente, nelle piante, nella terra c’è qualcosa di tuo, che anche quando non ci sei resta ad aspettarti.

The Moon and the Bonfires

Translated by Jules Nati

For all those years it was enough to look up from the fields to see under the sky the vineyards on the Salto river, and these too faded towards Canelli, in the same direction as the iron path, and as the whistle of the train that evening and morning ran along the Belbo river making me think of wonders, of stations and cities.

So for a long time I thought that this town, where I was not born, was the whole world. Now that I really saw the world and I know it is made up of many small towns, I do not know if, as a boy, I was much far off from the truth.

One travels over land and sea, like the young boys of my time went to the fairs and parties of the neighbouring towns, and danced, drank, threw punches, brought home the bacon and their broken fists. They treaded grapes and sold it in Canelli; they gathered truffles and brought them to Alba. There is Nuto, a friend of mine of the Salto river, that supplied tubs and presses to all of the valley down until Camo. What does that mean? A town is necessary, even only for the thrill of leaving it. A town means not being alone, knowing that in its people, in its plants, in its soil there is something that belongs to you, that even when you are gone it is waiting for you.

German Fremde

Rose Ausländer

Rose Ausländer’s ‘Fremde’ imagines the experience of the thirty-six righteous ones mentioned in the Jewish Talmud. It also mirrors the experience of modern day refugees travelling to safety by sea, and the question of belonging that comes with leaving your homeland.

Unser Schiff ohne Fahne gehört keinem Land kommt nicht an

Wasserbürger wir reisen in den Tag in die Nacht

spähn Land am Horizont Wellenland unsere Fata Morgana

Manchmal träumen wir ein Schiff fährt in entgegengesetze Richtung erwachen allein mit dem Wind

© Rose Ausländer Gesellschaft e.V.

Our ship without flag hails from no country never arrives

Water citizens we travel through day through night

Spy land on the horizon Waveland our mirage

At times we dream a ship sails in the opposite direction

Only to wake alone with the wind

Translated by Laura Marmion

[Resumir o traçado dos mapas]

Prisca Agustoni

Agustoni’s poetry successfully conveys migrants’ suffering and constraints in a world that so often gives more importance to borders than to human lives. Agustoni’s poem ‘Summing up the outline of maps’ quotes Walter Benjamin and it is inspired by his attempt to escape from the Holocaust.

Resumir o traçado dos mapas, as passagens de Paris ou de Calais num gesto trágico de uma noite qualquer

A bagagem dos prófugos é no fôlego e nos pés que superam distâncias é no ímpeto em migrar no coração do algoz

o cerco está fechando diante de mim escrevia o filósofo numa carta-epitáfio:

o humano recusa o humano expele de si os ácidos da espécie

“o novo decreto revoga o direito de asilo: a fronteira acaba de fechar”

[Summing up the outline of maps]

Translated by Alice Osti Magalhães and Jenny Marshall Rodger

Summing up the outline of maps, the tickets from Paris or Calais in a tragic gesture of any given night

the fugitive’s baggage is in their heavy breathing and feet that overcome distances, is in the impulse of migrating deep into the heart of the tormentor

− the fence is closing in front of me the philosopher wrote in an epitaph-letter:

humans refusing humans expelling from themselves the acids of the species

“the new decree revokes the right to asylum: the border has just been closed”

ser um apátrida, mais um nesse hospício inóspito inexato dessa máquina mortífera que é o continente

com seu extenso perímetro de alpes e mortos um arquivo de túmulos silenciados

© Editora Quelônio, 2020

as a stateless person, just one more in this inappropriate inhospitable asylum of this killing machine which is the continent with its vast perimeter of the alps and the dead an archive of silenced graves

Emily Spangler, A Green Procession

Emily Spangler, My Sister

Mordechai Gebirtig

In the midst of the barbarism of the German-Soviet invasion and subsequent partition of Poland in 1939, Mordechai Gebirtig describes the solace he sought in a portrait of his daughter, who found herself in the Soviet zone. Mordechai Gebirtig was shot in the Krakow ghetto on June 4th, 1942.

On the wall left of my bed Hangs my daughter Shifrele’s portrait. Oftentimes, at midnight, When I yearn for her and think, I see how she looks upon me, I hear how she speaks, ‘Dear Father, I know it brings you pain, The war will not last long, To you, I soon shall come, The spring raps readily upon the door. Smiling dearly to me,’ so speaks —Shifrele’s portrait.

Shifrele’s portrait

Translated by Aodhán Murphy

English Things You May Find Hidden in My Ear

Mosab Abu Toha

Mosab Abu Toha is a Palestinian poet and Pulitzer Prize winner. He was evacuated from Gaza in 2023 and now resides in the US. In this poem, he seeks refuge from the sounds of death and destruction hidden in his ear.

For Alicia M. Quesnel, MD i When you open my ear, touch it gently.

My mother’s voice lingers somewhere inside. Her voice is the echo that helps recover my equilibrium when I feel dizzy during my attentiveness.

You may encounter songs in Arabic, poems in English I recite to myself, or a song I chant to the chirping birds in our backyard.

When you stitch the cut, don’t forget to put all these back in my ear. Put them back in order as you would do with books on your shelf.

Rudaí a Aimseofá Ceilte i Mo Chluas

Aistrithe ag Aaron Groome

Do Alicia M. Quesnel, MD

i

Nuair a osclaíonn tú mo chluas, leag lámh air go séimh.

Maireann guth mo mháthar áit éicint inti.

‘Sí a guth an macalla a chabhraíonn liom teacht chugam féin arís nuair a bhíonn mo chloigeann ag dul thart le linn m’aire.

Seans go dtiocfá ar amhráin in Araibís, dánta i mBéarla a aithrisím dom féin, nó amhrán a chanaim do na héin ag bíogarnach inár gcúlchlós.

Nuair a chuireann tú greamanna sa ghearradh, ná déan dearmad iad seo go léir a chur ar ais i mo chluas.

Cuir ar ais iad in ord mar a dhéanfá le leabhair ar do sheilf.

The drone’s buzzing sound, the roar of an F-16, the screams of bombs falling on houses, on fields, and on bodies, of rockets flying away— rid my small ear canal of them all.

Spray the perfume of your smiles on the incision. Inject the song of life into my veins to wake me up. Gently beat the drum so my mind may dance, with yours, my doctor, day and night.

© City Lights Publishers, 2022

Seabhrán an dróin, Búiríl F-16, Scréach buamaí ag titim ar thithe, ar ghoirt, is ar chorpanna, de roicéid ag teitheadh— Ruaig canáil mo chluaise díobh go léir.

Steall cumhrán do mheangaí gáire ar an ngearradh. Insteall amhrán na beatha i m’fhéitheacha chun mé a dhúiseacht. Buail go séimh an druma ionas go ndamhsóidh m’intinn, le do cheannsa, a dhochtúir, de lá is d’oíche.

Polish Mapa

Wisława Szymborska

Wisława Szymborska is a 20th century Polish poet, and the laureate of the 1996 Nobel Prize in Literature. She received education in the Polish Underground during the war and was politically active throughout her life, advocating for intellectual freedom and democracy. In ‘Mapa’, she considers the false comforts offered by artificial boundaries that let us look down on the real world.

Płaska jak stół, na którym położona. Nic się pod nią nie rusza i ujścia sobie nie szuka. Nad nią – mój ludzki oddech nie tworzy wirów powietrza i całą jej powierzchnię zostawia w spokoju.

Jej niziny, doliny zawsze są zielone, wyżyny, góry żółte i brązowe, a morza, oceany to przyjazny błękit przy rozdzieranych brzegach.

Wszystko tu małe, dostępne i bliskie. Mogę końcem paznokcia przyciskać wulkany, bieguny głaskać bez grubych rękawic, mogę jednym spojrzeniem ogarnąć każdą pustynię razem z obecną tuż tuż obok rzeką.

Puszcze są oznaczone kilkoma drzewkami, między którymi trudno by zabłądzić. Na wschodzie i zachodzie, nad i pod równikiem –

Flat as the table, on which it’s laid. Nothing stirs under its surface, Seeking escape. Above it – my human breath does not stir whirlwinds, it leaves the broad surface undisturbed.

Its lows, valleyed are ever green, its highs, mountainous - yellow and maroon, and the seas, the oceans are an amiable pale blue along the torn edges.

Everything here is small, available close by. I may press onto volcanoes with my fingernails, stroke the poles barehanded. With one glance I can behold every desert, along with each river, just off to the side.

The jungles are marked with scarce trees, Among which I’d struggle to get lost. From the east to the west, Above and below the equator –

Translated

by

Jes Paluchowska

cisza, jak makiem zasiał, a w każdym czarnym ziarnku żyją sobie ludzie.

Groby masowe i nagłe ruiny to nie na tym obrazku.

Granice krajów są ledwie widoczne, jakby wahały się – czy być czy nie być.

Lubię mapy, bo kłamią.

Bo nie dają dostępu napastliwej prawdzie.

Bo wielkodusznie, z poczciwym humorem rozpościerają mi na stole świat nie z tego świata.

All Works by Wisława Szymborska © The Wisława Szymborska Foundation www.szymborska.org.pl

Silence, as if you sowed poppies and people lived quietly only in the black little seeds. Mass graves and sudden ruins are not here.

Borders are barely visible, Hesitating – to be or not to be.

I like maps because they lie. Because they keep me guarded from the truth. Because kindly, with good grace, They stretch upon my table a world From another world.

Spanish El Hombre Imaginario

Nicanor Parra

El Hombre Imaginario is a poem by Chilean poet Nicanor Parra, featured in his collection of poems Hojas de Parra (1985). It provides a somewhat melancholic, yet oddly comforting insight on how the mind creates imaginary worlds to take refuge in and find solace from our painful realities.

El hombre imaginario vive en una mansión imaginaria rodeada de árboles imaginarios a la orilla de un río imaginario

De los muros que son imaginarios penden antiguos cuadros imaginarios irreparables grietas imaginarias que representan hechos imaginarios ocurridos en mundos imaginarios en lugares y tiempos imaginarios

Todas las tardes tardes imaginarias sube las escaleras imaginarias y se asoma al balcón imaginario a mirar el paisaje imaginario que consiste en un valle imaginario circundado de cerros imaginarios

Sombras imaginarias vienen por el camino imaginario entonando canciones imaginarias a la muerte del sol imaginario

The imaginary man lives in an imaginary mansion surrounded by imaginary trees on the banks of an imaginary river

On the imaginary walls hang old imaginary paintings irreparable imaginary cracks representing imaginary events that occurred in imaginary worlds in imaginary times and places

Every evening, imaginary evening he climbs the imaginary stairs and walks out to the imaginary balcony to look at the imaginary landscape which consists of an imaginary valley encircled by imaginary hills

Imaginary shadows come up the imaginary path singing imaginary songs to the death of the imaginary sun

The Imaginary Man

Translated by Natalia Chotzen

Y en las noches de luna imaginaria sueña con la mujer imaginaria que le brindó su amor imaginario vuelve a sentir ese mismo dolor ese mismo placer imaginario y vuelve a palpitar el corazón del hombre imaginario © Nicanor Parra, 1985

And during the nights of imaginary moon he dreams of the imaginary woman that gave him her imaginary love he feels once more the same pain the same imaginary pleasure and it starts to beat again the heart of the imaginary man

Adiós, ríos; adiós, fontes

Rosalía de Castro

Nochtann an dán seo conas a mhothaítear faoi chiach agus daoine ag fágáil d’áite dhúchais. Ní aimsítear an tearmann in áit nua, ach i seanchuimhne, sa nádúr, agus san Ghailísis. Mar gheall go mbíonn an dán á casadh sa lá atá innu ann, maireann an tearmann seo trí ceol. Cosúil le roinnt amhráin as Éirinn, coinnítear guth muintir na háite beo ar neamhchead d’achar.

Adiós ríos, adiós fontes adiós, regatos pequenos; adiós, vista dos meus ollos, non sei cándo nos veremos.

Miña terra, miña terra, terra donde m’eu criei, hortiña que quero tanto, figueiriñas que prantei.

Prados, ríos, arboredas, pinares que move o vento, paxariños piadores, casiña d’o meu contento.

Muiño dos castañares, noites craras do luar, campaniñas timbradoiras da igrexiña do lugar.

Amoriñas das silveiras que eu lle daba ó meu amor, camiñiños antre o millo, ¡adiós para sempre adiós!

Slán, aibhneacha; slán, fuaráin

Aistrithe ag Nathan Harpur

Slán, aibhneacha; slán fuaráin; slán, srutháin beaga; slán, m’amharc, n’fheadar cathain a bhualfaimid le chéile athuair.

Mo thír, mo thír, tír ina thógadh mé, garraí beag dá raibh grá mór agam, crainn figí beaga a chuir mé ag fás.

Cluainte, aibhneacha, fáschoillte, coillte giústa a chroitheann an ghaoth, na héiníní bíogacha, teachíní fuinte fáiscthe mo shonais.

Muileann i measc na gcoillte, oícheanta glana faoi sholas na gealaí, ceolánacht na gclog, ón séipéal an fhích.

Sméara dubha beaga óna dreasa a thug mé do mo mhuirnín dílis, ródáin i ngoirt arbhair, slán go deo, slán!

¡Adiós, gloria! ¡Adiós, contento!

¡Deixo a casa onde nacín, deixo a aldea que conoso, por un mundo que non vin!

Deixo amigos por extraños, deixo a veiga polo mar; deixo, en fin, canto ben quero… ¡quén puidera non deixar!

Adiós, adiós, que me vou, herbiñas do camposanto, donde meu pai se enterrou, herbiñas que biquei tanto, terriña que nos criou.

Xa se oien lonxe, moi lonxe, as campanas do pomar; para min, ¡ai!, coitadiño, nunca máis han de tocar.

¡Adiós tamén, queridiña…

Adiós por sempre quizáis!…

Dígoche este adiós chorando desde a beiriña do mar.

Non me olvides, queridiña, si morro de soidás… tantas légoas mar adentro… ¡Miña casiña!, ¡meu lar!

Slán, glóir! Slán, lúcháir!

Fagaim an teach ina rugadh mé, fágaim an gráigbhaile, áit aithnidiúil, chun dul go alltar nach bhfuil feicthe agam!

Fágaim cairde chun bualadh le strainséirí, fágaim an chluain is mé ag dul chun farraige, fágaim, i mbeagán focal, achan rud dá bfhuil grá agam… ó, dá bhfeádfainn fanacht!

Slán, slán, téimse, luibheanna beaga na reilige, áit ina bhfuil m’athair curtha san uaigh, luibheanna a phóg mé an oiread sin, an tír ina d’fhásamar aníos.

Cloistear na cloig i bhad ó bhaile cheana féin, clogarnach an úllgharraí, ach mo léan domsa, an dhúil bheag bhocht, ní cheiliúrfaidh iad a thuilleadh

Slán agatsa fosta, a rúnsearc…

Slán go deo, b’fhéidir!

Fágaim slán agat agus mé ag gol, ó cladach na farraige.

Ná déan dearmad ormsa, a stóirín, má fhaighim bás le uaigneas… domhain i bharraige as do radharc… Mo theachín!, mo bhaile!

Martha Downes, Achill Island

Hanna Lujza Molnár, Solace in the Rain

Mimosa Lam

Mimosa Lam’s ‘room’ conjures up a childlike wonder at the everyday joys that provide refuge from the friction and exhaustion of daily life. Through simple, approachable language, she evokes a utopia in which one provides tenderness and care for others and, at the end of the day, for oneself.

用母親的溫柔飼養生活 替每一隻碗,找一隻匙羹做朋友 為枕頭穿上合身的枕頭套

把洗澡毛巾晾在曬到太陽的位置 每天早上,按照太陽的形狀煮雞蛋 雨天:煮水波蛋

在雨天心懷敬畏地出門散步

穿上水靴,帶一把漂亮的雨傘 觀察葉子,如何在雨水裡變翠綠 把不知險惡的蝸牛挪到路邊

把被暴雨從山坡上沖下來的 青苔碎屑,裝進玻璃瓶裡 想念雨天時,為它下毛毛雨

我的生活也是如此細小 如地磚裡的大樹般生長,卻細微得 無法被任何偉大的念頭發現 挑一個有很多暗格的背囊 放不喜歡的事物,也藏下 喜歡的事物 —— 青蔥餅乾、彩色糖果、毛絨絨的鎖匙圈⋯⋯ 留下一格,放撿到的楓香樹種子 它們常掉在不適合的地方

Translated by Fion Tse

care for life, tenderly as a mother does: give every bowl a spoon to be its friend help your pillow into a snug case that fits drape the towel where sunlight warms it each morning, cook an egg in the shape of the sun on rainy days: egg drop soup

on rainy days, go for a walk with awe in your heart wear your rain boots, carry a bright umbrella look at the leaves, how they turn emerald in rainwater deliver the naïve snail to the side of the road place the bits of moss, washed down the mountain by storms into a glass jar. when you miss the rain give it a light sprinkle

my own life, just as minute, growing like trees from concrete, yet so delicately hidden from any high-flying ideas

pick a backpack, one with many pockets put away the things you don’t like. and the things you like, too— scallion crackers, colorful candies, fluffy keychains— but save one pocket for the fragrant maple seeds you find. they often land in the wrong places

不想與人交談的時候,就回到 心裡的小房間 —— 我在這裡種滿了樹 地板鋪蓋著金黃色的地毯 烤箱時常飄出烘麵包的香氣 窗台按季節盛開不同的野花 牆上掛滿手工藝品、葉脈書籤、小畫卡⋯⋯ 我一直悄悄地佈置著這裡

when you’re tired of small talk, just return to the little room in your heart— where I’ve planted a forest of trees there’s a golden rug on the floor whiffs of freshly baked bread waft from the oven seasonal wildflowers bloom on the balcony on the walls hang art projects, pressed-leaf bookmarks, coloring cards… I’ve been decorating quietly, in secret

Daidža Bahro mislio da četnici ne ubijaju

ribolovce

Excerpt from Otkup sirove kože

Abdulah Sidran

Born during the Second World War in fascist-controlled Sarajevo, Abdulah Sidran began life at a running pace, inheriting what he would come to call a ‘Sidranian fear.’ His work gives form to this fear, bearing witness to a long history of refuge sought—as a Muslim, Communist, Yugoslav, Bosnian, and Sidranian.

Vogošća, april 1992. Kaže daidža svome ženskom čovječanstvu, ženi i kćerima, Safiji, Muberi i Almiri:

„Vi hajte u Sarajevo, ja ću ostat u Vogošći, ja sam ribolovac, penzioner, meni neće ništa, znaju da se ne bavim politikom.“

U Komandi Vojne policije, kod Ismeta Bajramovića Ćele, njegov savjetnik, a moj gimnazijski poznanik Fahrija Karkin, motorolom doziva glavnog vogošćanskog četnika, Branu Vlaču, da pokuša izvaditi daidžu. Ljeto, 1992. Pratim promjene u izrazu njegovoga lica i ništa ne primjećujem. Fahrija mi govori nešta okruglopanaćoše, a meni se čini da sve razumijem.

„Nikad ne smijem kazati da nekoga neko važan traži. Odmah podignu cijenu. Pa hoće dvadeset četničkih oficira za jednog našeg borca. Nego moram izokola. Vidjeću još, sa Jojom Tintorom. Navrati.“

Ćelo mu naredio pa mi Fahrija iz ogromne metalne kase sa kormilarskim točkom na vratima izvadio bocu nekog dobrog vinjaka, da ponesem kući. Priznaće mi, desetak godina poslije, u bircuzuRafaelo, kako mu je tada, toga jutra, odmah bilo u motorolu rečeno: „Nema ništa od toga!“, dakle, mrtav čovjek, ali je on procijenio da to meni ne treba kazivati. „Nisi bio zreo za istine!“ Slažem se, Fahrija je svakako, i višestruko, pametniji čovjek od mene. Nije to naročito teško, ali ipak...

Daidžinica Safija je, sve do novog milenija, sva mavi u licu, osam godina pričala sa svojim Bahrudinom. Sjedi, prekrila se dekom preko krila i koljena, gleda uprazno, i u to prazno priča. A u tom praznom ona vidi svoga čovjeka. I čuje njegove odgovore. Priča, priča, ponekad se, od nečega, i nasmije. Dobra moja daidžinica Safija!

Daidža Bahro je iz Sarajeva otišao u Vogošću čim je završio tokarski

Uncle Bahro never thought Četniks would kill a fisherman

from Scraps

Translated by Ena Selimović Excerpt

Vogošća, April 1992. My uncle says to his womenkin—his wife and daughters, Safija, Mubera, and Almira:

“You go on to Sarajevo, I’ll stay in Vogošća, I’m a fisherman, a pensioner, they won’t do anything to me, they know I don’t get involved in politics.”

In the military police command of the Bosnian Army overseen by Ismet “Ćelo” Bajramović, his advisor—and my high school classmate—Fahrija Karkin sends out a communication via walkie-talkie to Vogošća’s head Četnik, Brane Vlačo, in an attempt to get my uncle out of there. Summer, 1992. I track the changes in his facial expressions and notice nothing. Fahrija talks to me roundabout-and-sideways, but I feel like I’m getting every word.

“I can never say that someone’s being sought by anyone important. They immediately raise the price. Then they want twenty Četnik officers for one of our civilian fighters. So I need a different angle. Let me see with Joja Tintor, too. You stop by.”

On Ćelo’s order, Fahrija walked over to an enormous metal safe with a ship’s-wheel spinner on its door and removed a bottle of good brandy, for me to take home. He will admit to me, some ten years later, at the café bar Raffaello, that that morning, the immediate response that came through on the walkie-talkie was: “Forget about it!”—i.e., he’s a dead man—but he’d assessed it wasn’t something I should hear.

“You weren’t ripe for the truth!”

I agree. Anyway, and in many ways, Fahrija is a smarter man than I am. Not that my intellect is particularly difficult to surpass, but.

For the next eight years, until the new millennium, my aunt Safija spoke to her dear Bahrudin with her face mavi. She would sit, with a blanket over

zanat. Pretis vapio za dobrim majstorima. Oženio se i brzo dobio stan. Zavolio Vogošću, i u Sarajevo dolazio samo kad mora. Kazivalo se da je umio „proučiti mašinu“, i znao sâm, za svojim tokarskim strojem, napraviti njen neispravni dio, da se zbog toga ne bi moralo ići u Njemačku. Ionako se gubilo vrijeme, i predugo čekalo da iz Njemačke dođu potrebni dijelovi. (Malčice smo se uzdali i u to: da će i četnicima trebati takav znalac mašina i postrojenja u Pretisu, da ga, barem zbog toga, neće likvidirati!) Kazivao mi, uz naše rijetke šahovske seanse, kako se godinama poslije kajao što se dao nagovoriti da vanredno, uz posao, završi mašinsku tehničku školu. „Tad sam zijanio živce! Šta imam od tog što sam posto mašinski tehničar? I sad mi je moj drebang najdraži!“ Tako se, dakle, moj Bahrudin pretvorio u ribolovca. Valjalo je smirivati nerve, a to se ne može bolje nego uzvodu, kakvu bilo, uz potok, rijeku il’ jezero.

Tijela šestorice ubijenih Vogošćana pronađena u masovnoj grobnici na Vlakovu! Zašto na Vlakovu, kako to objasniti? Evo kako: četnici su otprve znali da će, kadli-tadli, „muslimanima“ „ustupiti“ prostor sjeverno od Sarajeva, kako bi se (za predviđenu muslimansku fildžan-državicu) napravila veza sa Zenicom i Tuzlom, pa sklanjali dokaze o zločinima na tome prostoru. A bili sigurni da prostori zapadno od Sarajeva trajno ostaju njihovi, i da se dokazi o njihovom zločinstvu na tome teritoriju mogu skrivati do Sudnjega dana!

Skupna sahrana, groblje Ugorsko, kod Vogošće. Petak, 11. jula 1997. godine. Trojica-četvorica mladih hodža: Safajte se, safajte se! Ko nema avdesta, ko ne umije, ne zna ili neće, neka se izdvoji... A vi, dolje, niste trebali ni dolaziti... Te se raspriča, sve sama krupna politika, onaj glavni, sa crnom bradicom. Sluša narod, sluša, zgledaju se ljudi, zgledaju – jesmo li došli na dženazu il’ na političko predavanje? – kad iz trećega reda, od „onih dolje“, ateista i gostiju, iskoraknu nekakav visok plavkast mlađi čovjek, krupnoga glasa:

„Prekini tu priču, hodža! Radi svoj poso!“

Pogledam bolje, jaštaje nego on, onaj ters, daidžić mi, Omer Jukić iz Kaknja. Hodža mu nešto otpovrnu, sijekući zrak lijevim kažiprstom, Omer dreknu još jednom, a uto iz prvog safa iskoraknu mršav mladić, neobrijan, još na njemu maskirka, te kao da stade između dvojice „posvađanih“. Kazuje hodži:

„U pravu je čovjek. Ja sam bio u rovu, nisi ti. Radi svoj poso i pusti politiku!“

Primaknem se teti Veri, daidžinoj komšinici. Vogošćanska starosjedilačka katolkinja, briše oči damskom maramicom:

„Je li ovo tjeraju nas inovjerce?“

„Izgleda, izgleda. Danas vas, a sutra će i nas.“

her lap and knees, staring into space, and speaking into it. And in that emptiness she saw her husband. And heard his responses. She talked and talked, and sometimes she laughed. My dear aunt Safija!

Uncle Bahro moved from Sarajevo to Vogošća as soon as he finished his apprenticeship to become a lathe operator. The company Pretis was begging for skilled craftsmen. He got married and was quickly given an apartment. He came to love Vogošća, and went into Sarajevo only when he had to. It was said that he could read a machine forwards and back, and knew how to make any defective part by himself using his lathe, no longer requiring trips to Germany, or losing precious time waiting for the needed part to arrive. (We even put some trust in this: that the Četniks would need someone so well-versed in the machines and mechanisms at Pretis and, at least for that reason alone, spare him from extermination!)

He would tell me, during our odd chess match, how years later he came to regret convincing himself to complete his degree at the technical school for engineering, which he attended part-time while keeping a job. “It frayed my nerves! What good did it do me to become a mechanical technician? My Drehbank is still my favorite lathe!” And so my dear Bahrudin became a fisherman. He had to find a way to calm his anxiety, and there’s no better salve than water, whatever shape it takes—creek, river, or lake.

The bodies of six murdered Vogošćans were uncovered in a mass grave in Vlakovo. Why Vlakovo? What could explain that? Here’s what: the Četniks knew from the get-go that they would eventually “surrender” the area north of Sarajevo “to the Muslims” in order (for this envisaged Muslim fildžan-state) to connect Zenica with Tuzla, and hide evidence of crimes on that land. And they were sure the areas west of Sarajevo would permanently remain theirs, and that the evidence of their crimes on that territory would be concealed until Judgment Day!

A mass burial, Ugorsko cemetery, near Vogošća. Friday, eleventh of July, 1997. Three or four young hodžas: “Take your positions, everyone, take your positions! Whoever hasn’t performed their ablutions—whoever can’t, doesn’t know or want to—please stand to the side… As for you all, down there, you shouldn’t have even come…”

He leans heavily into this politically charged nonsense, the one leading the pack, with his little black beard. People listen, looking at one another, listening, looking—have we come to a funeral or a political lecture?—when from the third row, from among those “down there,” atheists and people of other faiths, a tall young man with blondish hair steps forward and bellows out:

Napokon, krenuše hodže sa „svojim“ poslom, s molitvom, a u zraku osta da visi nekakva mučna napetost. Zabijem kišobran u mokru zemlju, oponašam kretnje onih koji čine molitvu, a mislim samo jedno: Biće dobro ako ovo prođe bez belaja!

© Abdulah Sidran, 2011

“Stop with that talk, hodža! Do your job!”

I get a better look, and sure enough it was him, my ruthless cousin Omer Jukić from Kakanj. The hodža retorted, cutting the air with his left pointer finger, Omer barked back once more, and then, from the first row, a skinny young man, unshaven and wearing camouflage, stepped forward as though to break up the quarrelers. He says to the hodža:

“The man’s right. I was in the trenches, not you. Do your job and leave politics alone!”

I approach Ms. Vera, my uncle’s neighbor. A longtime Catholic Vogošćan, dabbing a handkerchief to her eyes: “Are they trying to drive out those of us with a different faith?”

“It appears so, it appears so. Today it’s you, and by tomorrow it’ll be us too.”

The hodžas proceeded with “their” work, with prayers, but an agonizing tension was left hanging in the air. I shoved my umbrella into the wet ground, mimicked the gestures of those praying around me, and thought only: Please let this pass without incident!

Cafè-refugi

Artur Bladé i Desumvila

Artur Bladé i Desumvila (1907-1995) was a Catalan journalist. Cafè-refugi captures a comforting routine carved out of the paralysing confusion and ever-present worry that consumed so many at the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War. A refuge does not have to be idyllic, comfortable, or permanent.

Cafè-refugi de les hores lentes d’aquells dies primers... Amb els amics hi anàvem tots els dies... Les tardes eren llargues. les tardes i les nits.

Llegíem els diaris àvidament. Mai no s’ha llegit amb tan delit. Després nosaltres fèiem comentaris: ... La guerra... El front... «La Rambla» diu...

Estava sempre ple. Ens posàvem en un replà de dalt. Hi arribava el brogit confós de les converses. De tant en tant observàvem els nostres veïns.

Venien militars —no gaires—. Milicians. Buròcrates. Algun cop, en un racó, vèiem Diego Ruiz amb una verge pàl·lida. També hi venien les noies del «Sanghai» amb flors al pit.

Si la nostra conversa decandia, compràvem «Farias» a aquell home trist que hi havia a la porta... Fumàvem i escoltàvem els plors dels violins.

Cafè-refugi de les taules de fusta, i aquella llar del fons amb plats antics... Cafè-refugi de les hores mortes d’uns dies infinits.

Translated by Richard Huddleson

Café refuge of the slow-trickling hours in those first few days… Went there every day with friends… Long were the afternoons. The afternoons and the nights.

We hungrily devoured the newspapers. Never has reading been done with such delight. Afterwards we chatted amongst ourselves: … The war… The front… The Rambla…

It was always packed. We’d sit on a landing upstairs. From there we could catch the muddled din of discussion. Every so often we took in those around us.

There were soldiers – not many. Militia. Bureaucrats. Once, in a corner, we saw Diego Ruiz with a pale young girl. There we’d see the dancing girls from the Shanghai club with flowers across their chests.

If our conversation went stale, we bought the rag from that sad man that hung around the door… We smoked and listened to the wailing violins.

Café refuge, with the wooden tables, and that hearth in the back, stacked with old plates… Café refuge of the dead hours that filled never-ending days.

Latin Aeneid VI lines 134-155

Virgil (Publius Vergilius Maro)

Virgil (70-19 BC) in the Aeneid is also prophesying the fall of Rome through his ‘narrator’ Aeneas, derived from Homer’s Iliad. The wand or golden bough is the symbolic and redolent myth as to how the poet becomes a poet, prefiguring descent to the Underworld and meeting Anchises.

Tenent media omnia silvae, Cocytusque sinu labens circumvenit atro. Quod si tantus amor menti, si tanta cupido est, bis Stygios innare lacus, bis nigra videre Tartara, et insano iuvat indulgere labori, accipe, quae peragenda prius. Latet arbore opaca aureus et foliis et lento vimine ramus, Iunoni infernae dictus sacer; hunc tegit omnis lucus, et obscuris claudunt convallibus umbrae. Sed non ante datur telluris operta subire, auricomos quam quis decerpserit arbore fetus. Hoc sibi pulchra suum ferri Proserpina munus instituit. Primo avulso non deficit alter aureus, et simili frondescit virga metallo. Ergo alte vestiga oculis, et rite repertum carpe manu; namque ipse volens facilisque sequetur, si te fata vocant; aliter non viribus ullis vincere, nec duro poteris convellere ferro. Praeterea iacet exanimum tibi corpus amici—heu nescis—-totamque incestat funere classem, dum consulta petis nostroque in limine pendes. Sedibus hunc refer ante suis et conde sepulchro. Duc nigras pecudes; ea prima piacula sunto: sic demum lucos Stygis et regna invia vivis aspicies.

(The) Sanctuary of Poetry

Translated by Dr Kevin Kiely

The flood waters of lamentation encircle the deepest forest— it is not only intellectual love and headlong desire that brings you across the river Styx where you don’t have to look twice at Tartarus irrationally plunging into the work, the phantasmagoria— into the pursuit of absolute achievement. There she is— Goddess Proserpine among the sacred grove of shadows so dense you will not immediately find the shaft of gold leaf— these shadows are layered as to make it impossible to tell the wood from the trees. Impossible for just anyone to enter the underworld unless you find this golden shaft and prize it off the tree. The shaft or wand is your highest gift, and owed to her. Don’t be alarmed at your dismay for another shaft will grow into pure leafy gold similar to the one you’ve taken.

Yes, it’s daunting as your eyes dart over and back but go for it fearlessly until the golden bough is yours. Remember, that your destiny prefigures the gaining of this wand of gold— of course, it’s complicated what you feel. To others who seek this— no amount of labour can rend it from the sacred tree. They might try every possible force but no chance

This is your fate because one has gone before you into the land of the dead. You mourn and juggle with fate— Have the greatest reverence towards the dead one, obey every sacrificial rite, offer total humility of the self. It is difficult to purify your pride—and this, once done to perfection— you shall tiptoe through the Elysian fields which are vast territories shut off from human beings.

Mondnacht

Joseph von Eichendorff

In “Mondnacht”, written during his time in Berlin, Eichendorff expresses his yearning for a home lost long ago. The loneliness he faces and his desire to be at one with the world give rise to one of the most striking poems of German Romanticism.

Es war, als hätt’ der Himmel Die Erde still geküsst, Dass sie im Blüten-Schimmer Von ihm nun träumen müsst’.

Die Luft ging durch die Felder, Die Ähren wogten sacht. Es rauschten leis die Wälder, So sternklar war die Nacht.

Und meine Seele spannte Weit ihre Flügel aus, Flog durch die stillen Lande, Als flöge sie nach Haus.

Moonlit Night

Translated by Cem Heckmann

It felt like heaven Had kissed the earth goodnight That she, amidst her flowers, Still thought of him, so bright.

The air went through the fields, The ears leaped for the light. The woods were rustling deep, So starry was the night.

And my soul Spread its wings to fly Through the quiet country To its home somewhere up high.

Venetian De scólzh

Guido De Carlo

Using the rural dialect of his homeland, the poet imagines escaping with his beloved deep into nature, far from the burdens of life. The ending echoes Virgil’s Bucolics: “Here are cool springs, here soft meadows, Lycoris, here a grove; here, with you, I would let myself be consumed by time itself.”

Se te fóse ađès co’ mi a varđar l’amor del merlo che fràzha tra le fóje, a gòđer quel tut che frème atórno co’ ‘na raſon precisa da le rađìs fin su dove ‘l cucù méte le piume nóve. A spiàr ‘sto mondo che nàse e more parché cusì l’é scrit. Un pas drìo n’altro sénzha balegàr un fior, dentro ‘l sentiér, drìo ‘na farfala. Là, dove lontan resta tut ‘l pensar, ‘l sfađigar, le caſe, i campanìi, dove le ore no’ bate mai. Se te fóse co’ mi, ađès, no m’inportarìa gnànca de morir.

© Kellermann Editore, 1995

If you were here now with me, watching the blackbird’s love that rifles through the leaves, savouring this “all” which quivers around us with a precise purpose from the roots all the way up where the cuckoo grows new feathers. Peering at this world which is born and dies because so it is written. One step after another without trampling a flower, into the path, trailing a butterfly. There, where one is far from all the thinking, the toiling, the houses, the bell towers, where the hours never strike. If you were with me now I would not care even to die.

Translated by Greta Chies

Osip Mandel’štam

In this poem — written when he was only seventeen years old — Mandel’štam evokes a retreat into childhood as a form of refuge from the weariness of grown-up life. Through dream-like and melancholic images, he expresses a longing for innocence, memory, and the familiar consolation of a distant, unspoiled past.

Только детские книги читать, Только детские думы лелеять,

большое далеко развеять,

глубокой печали восстать.

Я от жизни смертельно устал, Ничего от нее не приемлю,

люблю мою бедную землю Оттого, что иной не видал.

Я качался в далеком саду На простой деревянной качели, И высокие темные ели Вспоминаю в туманном бреду.

To read only children’s books

Translated by Greta Chies

To read only children’s books, To cherish only childish dreams, To cast away all that looms too vast, And from deep sorrow rise again.

I am mortally tired of life, I receive nothing from it, But I love my poor homeland For I have seen no other.

In a distant garden I swayed On a simple wooden swing And in a misty, fevered dream I remember tall, dark firs.

Maja Hamidovic, Retiro Park

Maja Hamidovic, Together

BALANG ARAW, IUUWI KITA SA AMING

BAYAN SA NEGROS, SA PANAHON NG

ANIHAN

Jaku Mata

Jaku Mata’s poems in Filipino often describe precarious living conditions in the Philippines, both in the urban and rural context, but always point to a way of making do and persevering, both in a political and intimate manner. Refuge is something being created and already here at the same time.

Mula Dangwa hanggang sa batok ng mga kanyang mga kabukiran. Hihimlay tayo sa mga parang ng mga haciendang nabawi ng ating mga magsasaka. Bubungkal hindi lamang sa lupa kundi pati na rin sa isipan ng bawat tao. Itanim ang mga bagong kaisipan, ang katotohanan, at ang hangad para sa kalayaan. Palangga, hayaang berdehin ng lupa ang iyong mga balat. Tantanan mo ang kakahawak sa iyong mga labi dahil mamumulaklak ito sa umaga. Huwag mo nang takpan ang iyong mga tainga dahil wala nang bombang magbibigay sugat sa lupa. Hihintayin na lang nating bumunga ang panganay na ani sa palad mong malamlam. Na ang nagpataba nito ay ang mga bala ng mga nakaraang digmaan na pinulbo ng panahon. Gagaling tayo sa mga kwentong mabubuo habang umiinom ng sariwang katas ng tubo. Nakatitulo ang puso ko sa ilalim ng iyong pangangalaga. Iuuwi kita dito, sa aming bayan sa Negros, kung saan tayo’y mamahalin ng araw at ulan. Gigisingin ng hangin sa panahon ng anihan, hinog sa aking lingap.

© Jaku Mata, 2023

SOMEDAY, I TAKE YOU TO MY VILLAGE IN NEGROS,

IN TIME FOR THE

HARVEST

Translated by Eric Abalajon

From Dangwa up to the peak of its mountains. We will rest in the haciendas taken back by peasants. Cultivate not just the earth but also the minds of each individual. Plant new ideas, the truth and the aspiration for freedom. My love, allow the earth to turn your skin green. Avoid touching your lips for it will bloom in the morning. Do not cover your ears anymore because there will be no more bombs hurting the land. We will just wait for the first harvest to bear fruit in your tender palms. Whose fertilizer were iron bullets crumbled into ash by time. We will heal through the stories formed while drinking fresh sugarcane juice. My heart is titled under your care. I will take you here, in my village in Negros, where the sun and rain will cherish us. Be woken up by the wind in time for harvest, made ripe in my embrace.

Italian IL GELSOMINO NOTTURNO

Giovanni Pascoli

Pascoli contrasts the nest, where young ones can find refuge under adult care, with the house, a symbol of the family he is unable to form. Though a safe haven for some, the house and what it represents are unattainable for him, and he remains trapped in his childhood nest-cage.

E s’aprono i fiori notturni, nell’ora che penso ai miei cari. Sono apparse in mezzo ai viburni le farfalle crepuscolari.

Da un pezzo si tacquero i gridi: là sola una casa bisbiglia. Sotto l’ali dormono i nidi, come gli occhi sotto le ciglia.

Dai calici aperti si esala l’odore di fragole rosse. Splende un lume là nella sala. Nasce l’erba sopra le fosse.

Un’ape tardiva sussurra trovando già prese le celle. La Chioccetta per l’aia azzurra va col suo pigolio di stelle.

Per tutta la notte s’esala l’odore che passa col vento. Passa il lume su per la scala; brilla al primo piano: s’è spento...

È l’alba: si chiudono i petali un poco gualciti; si cova, dentro l’urna molle e segreta, non so che felicità nuova.

THE NOCTURNAL JASMINE

Translated by Martina Stoilovska

And the night flowers start to dance

At a time when I think of those I hold dear.

Among the viburni plants

The crepuscular butterflies have appeared.

All sounds have been silent for a while: There, only one house still whispers around the ashes. Underneath the wings, dormant nests pile Like eyes beneath eyelashes.

From the open chalices a smell exudes

Of ripe red strawberries drifting in waves. In the room a light still brightens the moods. Grass covers the freshly-dug graves.

You can hear the buzz of a tardy bee

Looking for a cell, but finding each gate sealed with bars. In the sapphire blue yard the Mother Hen roams free Along with her chirping of stars.

Like an elegant dress, the wind wears A sweet smell all throughout the night. The light travels up the stairs; It shines on the first floor, then goes out without a fight.

It is dawn: the petals must now shut, Though a little wrinkled; I am certain in my knowing That in the cosy and hidden hut A new delight, mysterious to me, is growing.

French Two Poems by Henri Meschonnic

These poems explore refuge not as a physical location, but as an embodied state of being. Through themes of memory, shared experience, and the profound bonds between individuals, the translations illuminate how we find safety and resilience in our connections with others and within ourselves, even amidst displacement and loss.

I.

pas de stèle pas de mémoire pour le vivant inconnu que nous avons en nous à chaque coup que reçoit un autre

nous respirons la même ombre tous les mots disent la mêlée de ce qui n’a pas de mots chaque instant lève un soleil dans d’autres yeux qui sont nos yeux II.

une vieille photo une enfance je suis dans ton passé comme tu es dans mon avenir tu n’as jamais pu savoir que ton enfance est en moi comme je suis dans mon enfance comme on est dans ses amours

© Arfuyen, Et la terre coule, 2006

© Bernard Dumerchez, Je n’ai pas tout entendu, 2000

I. no stone no memorial for the living unknown that we carry within us with every blow that another receives we breathe the same shadow all words tell the fray about what has no words each moment a sun rises in other eyes that are our eyes

Translated by Gabriella Bedetti and Don Boes

II. an old photo a childhood I am in your past as you are in my future you could never have known that your childhood is in me as I am in my childhood as we are in our loves

Contributors

Cainteoir sách dúghafach Gaeilge é Pól Ó hÍomhair ar tógadh é i dteaghlach i dTuaisceart Chontae Átha Cliath a labhraítear an Béarla agus an Fhraincis ann. Tá sé ina thríú bhliain ag déanamh staidéir ar an Nua-Ghaeilge agus an Teangeolaíocht i láthair na huaire.

Alyssa Salzberg is a PhD student researching themes of trauma and sexuality in the work of French Surrealist René Crevel. She got her MA in Translation Studies from University College Cork and her BA in English literature from Mount Holyoke College.

Charlie Judd is a second-year Latin and Linguistics student whose work includes English and Latin poetry. Her favorite pastimes include thinking about the Locked Tomb series, waxing poetic about the nature of desire, and trying to square her radical politics with her classical studies obsession.

Fion Tse (she/they) is a translator working between English and Chinese (Cantonese and Mandarin). She is currently pursuing an MFA in Literary Translation at the University of Iowa, and her work has been published in Asymptote, World Literature Today, and Cha, among others.

Maria McChrystal is a graduate of the M.Phil in Literary Translation. Having studied abroad in both Spain and Czechia, she has produced extensive volumes of poetry in both Czech and Spanish. Maria is currently enrolled in her second Master’s program with a view to furthering her literary productions.

Jules Nati is a third year English Studies student. She has just recently discovered coffee and now roams the Arts Block like an addict.

Laura Marmion is a 2nd Year Ancient History and Archaeology major, minoring in Classical Civilisations. She’s trying her best.

Alice Osti Magalhães is a Brazilian poet and translator. She received a Master of Philosophy (M.Phil) in Literary Translation from Trinity College Dublin (2013).

Jenny Marshall Rodger is a British translator and lives in Brazil. Rodger holds an MA in Translation from the University of Westminster (1994).

Aaron Groome is a fourth year Computer Science student. He speaks Irish and English.

Originally from Poland, Jes Paluchowska is a final year English Major angry at the modernist movement. For their recent work, check out the Abyss, Midnight and Village magazines, as well as the Delicate Migration anthology.

Natalia Chotzen is a Chilean translator, writer and illustrator based in Dublin since 2023. She recently completed her M.Phil in Literary Translation at Trinity College. She works in Spanish and English and is currently working on what she fondly calls her “cringey little fantasy novel that refuses to cooperate”.

Nathan Harpur is a second year Biological and Biomedical Sciences student that has a massive passion for languages and how we are connected by them. He will be the Irish language editor for Trinity News this academic year. His love for literature provokes him to translate to reach wider audiences.

Ena Selimović is a Yugoslav-born writer and translator. Her work has appeared in Words Without Borders, The Paris Review, Asymptote, and elsewhere. Her latest full-length translation—Maša Kolanović’s Underground Barbie—is out with Sandorf Passage. She holds a PhD in comparative literature.

Aodhán Murphy swims gladly in the Danube, but would probably sink in the Liffey.

Richard Huddleson is Assistant Professor at the National University of Ireland, Maynooth, where he specialises in Translation and Catalan Studies.

Dr Kevin Kiely, Poet, Critic, Author; PhD (UCD) in the Patronage of Poetry at the Edward Woodberry Poetry Room, Harvard University; W. J. Fulbright Scholar in Poetry, Washington (DC); M. Phil., in Poetry, Trinity College (Dublin); Hon. Fellow in Writing., University of Iowa; Patrick Kavanagh Fellowship Award in Poetry; Bisto Award Winner.

Cem Heckmann is a fourth-year undergraduate from Cologne, Germany, studying Middle Eastern and European Languages and Cultures – a degree with a name so long that it leaves no room for further detail.

Greta Chies is an Italian teacher and translator, a graduate from the M.Phil in Literary Translation at Trinity College. She previously graduated in Interpreting and Translation from the University of Trieste. Within this field, she is particularly interested in studying the translation and rendering of dialects and minority languages.

Eric Abalajon’s translations have appeared in Asymptote, Modern Poetry in Translation, Firmament Magazine, Exchanges: Journal of Literary Translation, and Tripwire: a journal of poetics. He has poetry collections forthcoming from FlowerSong Press and Atomic Bohemian. He lives near Iloilo City.

Martina Stoilovska is a second-year undergraduate in English Studies. She loves reading (who would have guessed?) and occasionally dabbles in writing and translating poetry. When her nose is not inside a book, she enjoys embroidering and solving crossword puzzles.

Gabriella Bedetti’s translations of Meschonnic’s essays and other writings have appeared in New Literary History, Critical Inquiry, and Diacritics. She and Don Boes are seeking a publisher for The Butterfly Tree: Selected Poems of Henri Meschonnic. Their translations appear in Puerto del Sol, Asymptote, RHINO, The Southern Review, and elsewhere.

Don Boes is the author of Good Luck With That, Railroad Crossing, and The Eighth Continent, selected by A. R. Ammons for the Samuel French Morse Poetry Prize. His poems have appeared in The Louisville Review, Painted Bride Quarterly, Prairie Schooner, CutBank, Zone 3, Southern Indiana Review, and The Cincinnati Review.

Artists

Sophie Quinn occasionally finds cats in hedges.

Maja Hamidovic is a final year English Literature and Spanish student. Although not a professional photographer, her photographs have been exhibited and appeared in a magazine. Maja’s photography captures candid, authentic moments that convey raw emotion and a sense of solitude, often featuring strangers in everyday street scenes that create a feeling of timelessness and community.

Emily Spangler is a second year Business, Economics, and Social Studies student with a particular interest in language and poetry. She loves the French language but has recently given up studying it academically after taking French Language and Civilisation. R.I.P.

With a newly found interest in photography, Martha Downes’s preferred medium is mainly film but also her phone camera. She is based in Dublin and studying European Studies.

Hanna Lujza Molnár is a 3rd year student pursuing Art and Architecture History at Trinity and this year’s Art Editor for JoLT. She wishes for all art enthusiasts to share their work in JoLT. Also, it has been four months since she last had a spice bag, so she very much wishes to eat one soon.

Emily Spangler, The Guardians of Peace

What does the heart that dwelt in silence need But words that serve as a sign and as a prayer,

Like a small fire lit swiftly through the night Or a table caught glimpse of in a home however bare?

Yves Bonnefoy, ‘May a place be made...’ Translated by Ioana Răducu