DIGITAL HEALTH HOLDS PROMISE FOR SUBSTANCE USE DISORDERS PAGES 02–03

HOW TO NAVIGATE MENTAL HEALTH APPS

PAGES 10–11

THE IMPACT OF COVID-19 ON MENTAL HEALTH IN AUSTRALIA

PAGES 16–17

DIGITAL HEALTH HOLDS PROMISE FOR SUBSTANCE USE DISORDERS PAGES 02–03

PAGES 10–11

PAGES 16–17

The third issue of Psychiatry focuses on the shift to technology and digital landscapes in the mental healthcare field. This movement towards digital mental healthcare has been perpetuated, over the last three years, by the COVID-19 pandemic and the several lockdowns experience by humanity on a global scale. The mental health of many individuals suffered during this time and as a means to seek help society was drawn into using technology, devices and social media. This issue details evidence to support novel treatments in a modern era and current and future perspectives from psychiatry experts with the intent to aid our clinician readers in implementing digital tools in their clinical practice and management of mental health.

We’d like to extend our appreciation to Professor David Castle and Dr Gillian Strudwick for their editorial support and contribution to this issue.

Dr Gillian Strudwick RN, PhD, FAMIA

Dr Gillian Strudwick RN, PhD, FAMIA

CHIEF CLINICAL INFORMATICS OFFICER & INDEPENDENT SCIENTIST, CENTRE FOR ADDICTION AND MENTAL HEALTH (CAMH); ASSISTANT PROFESSOR, INSTITUTE OF HEALTH POLICY, MANAGEMENT AND EVALUATION, UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO.

Technology is all around us and is a part of our everyday lives offering conveniences that were unheard of just a decade or two ago. Examples of these conveniences abound; shopping is done on the internet while riding the bus home from work, haircuts can be booked online without picking up the phone and socialising with loved ones on the other side of the globe can be done via a tablet in a matter of moments. The ease with which we perform these activities in our everyday lives has led many of us to have similar expectations in our roles as both healthcare providers and patients ourselves.

We expect that medical appointments can be booked swiftly and without much effort, that our providers (and that us as providers) can access

electronic health records from all sources in a comprehensive and simplistic manner, that treatments can be offered in virtual manners when there is evidence to suggest this is appropriate, and the list goes on. Overall, in healthcare, technology use is becoming more pervasive with increasing digitally enabled conveniences. That said, healthcare is often still considered to be decades behind in its uptake of digital technologies when comparing it to almost any other sector. For example, many organisations still document medical information on paper charts, whereas much of the banking industry went ‘paperless’ years ago. Mental healthcare delivery has often been described as one of the areas of healthcare that has been even slower to adopt technology into clinical care processes. However, in the broader healthcare community, this sentiment about mental healthcare is changing,

particularly with the stories many of us have heard of digital innovation that have come as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. A staggering amount of clinical care interactions in mental health went ‘virtual’ in March 2020 at the onset of the pandemic, putting a spotlight on the possible opportunities that technology could foster in this clinical area. In this issue of Inside Practice: Psychiatry, Neil Thomas provides an overview of the digital mental healthcare landscape specific to the Australian context, Susan Rossell provides an update on findings from the COLLATE (COvid-19 and you: mentaL heaLth in AusTralia now survEy) project and we see how education for clinicians shifted to new virtual avenues with Malcolm Hopwood as he consulted a real-life patient with depression in an online masterclass. Furthermore, utilising the digital format of this publication, an update on

agomelatine’s new indication in GAD is provided by David Castle. Digital innovation in mental healthcare delivery, however, is not new. In pockets around the globe, health systems, clinicians, researchers and patients in the mental healthcare delivery space have been developing and using technology for a variety of purposes that have ranged from supporting health information exchange and delivery to assessments providing psychological treatments and maintaining mental wellness. The technologies leveraged to perform these activities include websites, online portals for patients, digital groups, telehealth, virtual reality, video games, electronic health records, smartphone apps, chatbots and beyond. In this issue, Brian Lo describes how these technologies can be effectively evaluated. In addition, Jessica D’Arcey, Sean Kidd, Oskar Flygare and Lydia Sequeira shine a light on how technologies such as these

have been utilised for specific focused areas such as psychosis, substance use, obsessivecompulsive disorder and suicide prevention. Additionally, social media and some of its impacts and consequences as they relate to mental health are explored by Toni Pikoos in the featured article of this issue.

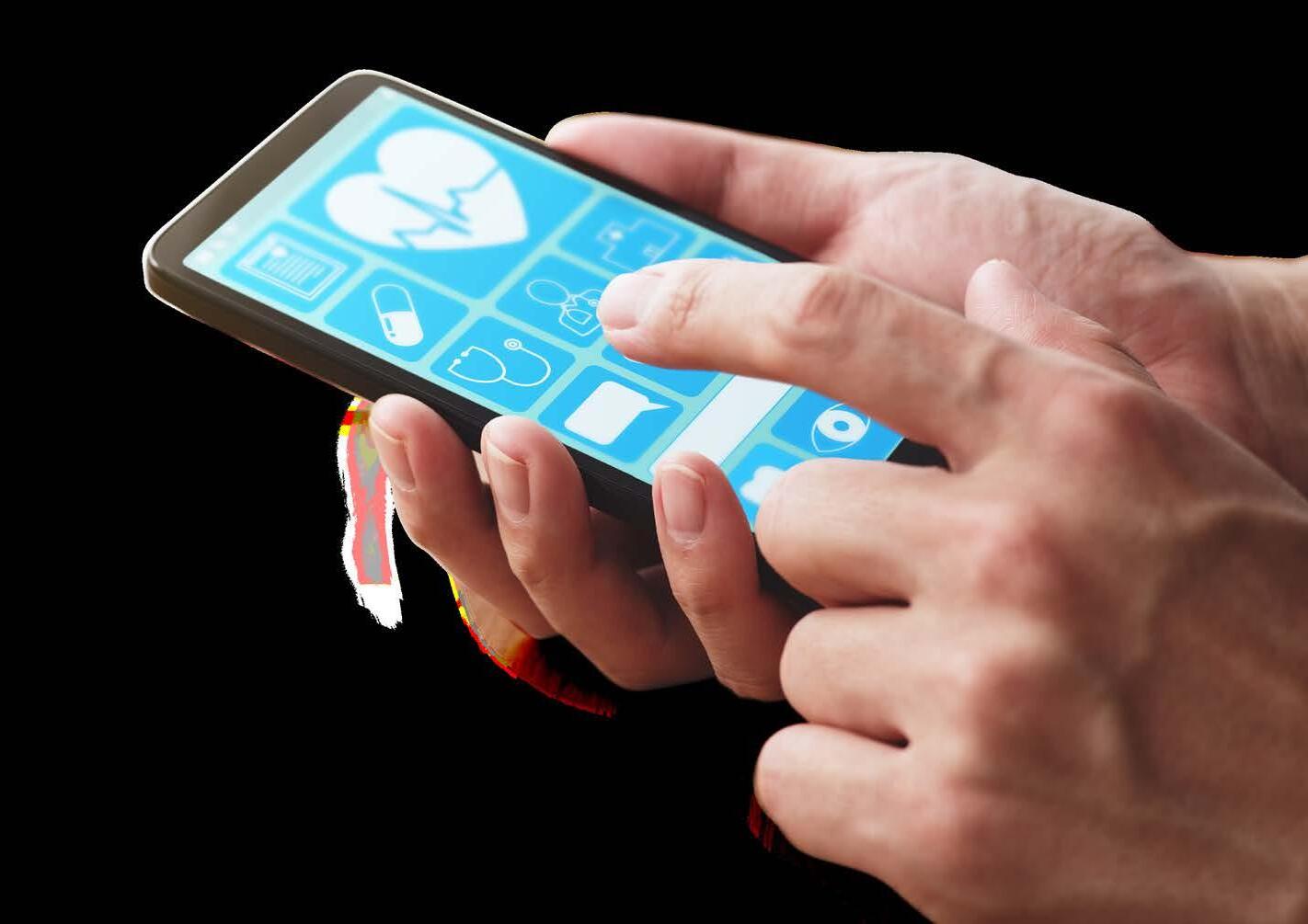

One particular kind of technology appears to hold promise for the mental healthcare field. According to the United Nations, mobile phone use globally is ubiquitous with an increasing number of these being ‘smartphones’ with access to the internet, apps and other functions that extend beyond a telephone. It is expected that an increasing amount of healthcare will be delivered via mobile phones in the future. This may provide an opportunity for the mental health field, especially as we consider several issues of equity such as providing care to those living in rural and remote locations, and supporting those who lack access to childcare as just a few examples. To date, there are already a significant number of mental health apps that exist and Iman Kassam discusses practical approaches for selecting an app, and why this matters, within this issue.

We hope that you enjoy reading this issue of Psychiatry and find it relevant to your own area of practice.

Alongside these challenges, the development of digital health technologies in mental health has increased exponentially in the past decade. In the UK alone, there are at least 21,000 health apps and 3,857 mental health apps on Apple and Google Play stores. 3 However, most of these apps and other technologies aren’t supported by any evidence. For example, recent systematic reviews examining technologies for SUDs report only around 20 studies.4,5

health-topics/drugspsychoactive#tab=tab_2

2. Hsu M, Ahern DK, Suzuki J. Digital phenotyping to enhance substance use treatment during the Covid-19 pandemic. JMIR Ment Health. 2020;7(10):e21814.

3. Organization for the Review of Health and Care Apps (ORCHA), 2021. Digital mental health and recovery action plans. orchahealth.com/wpcontent/uploads/2021/04/ Mental_Health_ Report_2021_final.pdf

4. Kazemi DM,

The COVID-19 pandemic significantly accelerated the use of digital health technologies. Not only did we observe a rapid shift to virtual delivery of mental healthcare across the globe, 3,6,7 we saw an unprecedented increase in recommendations from practitioners for patients to use mental health technologies. 3 Access to smartphones, cellular data and wireless internet is also rapidly expanding across the globe, including in rural areas

and low-income countries, though a digital divide still exists.8–10 However, concerns remain for populations that require consideration within these larger systems such as those challenged with poverty, homelessness, or severe mental illness.

“With growing access to digital health resources has come growth in investment.

From 2019 to 2020, global spending on mental health apps grew by 32%, with predictions that annual spending will reach $500 million by the end of 2022”

AUXIER B, et al . 2021As in other areas of digital mental healthcare, digital technologies that address substance use span a range of technologies from telemedicine to mobile technologies like smartphones and wearables.

Some are simple text message protocols and basic trackers while others involve tailored multi-feature and combined device approaches, facilitating asynchronous and real-time clinician engagement and integration with electronic medical records. Telemedicine has demonstrated feasibility and efficacy in SUD treatment, smartphone-based applications have been found to decrease substance abuse and improve quality of life across a range of addictions, and wearable sensor-based interventions hold similar promise.11

pharmacologic intervention, direction to reduce exposure to cues, and flags for clinician engagement.12 Effectiveness findings are mixed for these tools, with the most promising showing small–medium effects (the largest trials in alcohol addiction) with a preponderance of pilot trials.

Sustained engagement is also a significant hurdle in this field. While the initial engagement of help-seeking individuals is generally good, there are sharp dropout rates.13 In substance use, the most promising strategies for keeping end-users engaged are individualised tailoring of content, multimedia delivery of content, and reminders.14 As in other health domains, the framework within which digital health advancements have taken place has evolved rapidly. These tools have moved well beyond the selfhelp frame and into the realm of prescribable and billable digital therapeutics.15

Smartphones and wearables can also capture information on treatment engagement and effectiveness, risk trajectories, relapse and overdose – in the frame of ‘digital phenotyping’. Keystrokes can ascertain information such as reaction times, accelerometers can assess sleep, microphones speech coherence, text logs suicidality, and GPS activity levels. Wearable biosensors can monitor alcohol intake by detecting ethyl glucuronide in sweat and highly accurate (95%) algorithms can detect opioid overdose by using short-range active sonar to assess respiratory rate.2 These kinds of data, paired with other information (e.g., demographics) have demonstrated 77% predictive accuracy for alcohol relapse and a positive predictive value of 0.93 for opioid drug craving 90 minutes in advance, using machine learning.2

Such signals can prompt automated messages to patients such as warnings, recommended actions and motivational messages, suggest resources, and prompts to engage support. Digital platforms that facilitate clinician access to this information can also be used to triage clinical engagement and tailor interventions.

Across technologies, there is an emphasis on overcoming the lack of access to in-person support at moments when substance use and relapse risks are peaking. Referred to as “just in time adaptive interventions”, indications of risk on a device such as a smartphone can cue motivational prompts, craving management, coping assistance as well as prompt

9. Vogels EA.

Some smartphone apps are available by prescription. An example of this is the reSET-O® app by Pear Therapeutics, one of the first smartphone apps addressing substance use to be approved by the FDA. This is a CBT-based app designed to provide adjunctive contingency management for individuals involved in an outpatient care program for substance abuse with a connected platform for clinician use.16

11.

12.

that digital health could have on the global burden of substance abuse. These impressions are driven in no small part by the commercial opportunities that these technologies represent. While certainly well-founded, our current state should be considered one of ‘early days’. Most technologies lack evidence entirely, and those that are generating evidence are largely comprised of small pilot studies.4,5 Even larger knowledge gaps exist with respect to acceptability, patient engagement, coupling with clinical interventions and integration into clinical workflows. Further, with such a breadth of technologies being used for a range of purposes, it is important to note that the success of these technologies in the substance use space will have different lenses for interpretation. For example, technology designed to reduce overdoses may not reduce overall substance use.

A range of effective digital health interventions exist in substance abuse from telemedicine to mobile technologies (i.e., smartphones and wearables)

Digital interventions are moving towards a framework where clinicians can prescribe as a therapeutic

Apps have the ability to prevent relapse via various prompts for motivation, craving management, coping assistance, pharmacologic intervention, direction to reduce exposure to cues, and flags for clinician engagement

These ‘real-time’ assessments have also advanced our understanding of drug triggers, stress, cravings, and drug use.15 For example, in-the-moment technology-facilitated assessments in people with opioid use disorder have demonstrated a stronger association between craving and drug use, than stress and drug use. These patterns also differ as a function of the particular substance used. Such information is useful in targeting interventions based on individual and population risk and behaviour characteristics and can trigger clinician engagement and emergency responses.

Early outcomes – paired with rapid technological advances and access to technology –have created a great deal of optimism about the impact

Like the larger field of digital health, ethical challenges include those of privacy and personal health information being collected by commercial enterprises and equity implications with respect to technology access and literacy and underrepresented populations in technology development. The business and funding environments are also extremely challenging, with most technologies not moving beyond beta and pilot phases even when demonstrating promising outcomes.

As in any field of technological advancement, there are numerous challenges to be overcome. While harsh scepticism and unbounded enthusiasm are tempting paths to take while we await better evidence, we suggest careful optimism. Despite some growing pains, digital health holds a great deal of promise in the area of substance use. With underfunded services and systems alongside patient interest and access to technology, lives can be improved and saved and the global burden of substance use and addictions eased through these approaches.

Smartphones and wearables can ascertain a range of patient information for ‘realtime’ assessments: keystroke (reaction times), accelerometers (sleep), microphones (speech coherence), text logs (suicidality), GPS (activity levels) and biosensors (alcohol intake), further improving prompts for user engagement and prevention of relapse and overdose

Current barriers to use include lack of sustained engagement, limited evidence to support use, integration into clinical workflows, limited reductions in overall substance abuse and commercial exploitation of confidential patient data

Social media dominates our lives. Although there are several benefits to its use in maintaining social connectedness, the negative impacts of social media use on mental health are of great concern. Particularly in younger age groups, the most active users on several platforms, who have wide access to content where cognitive and identity development has the potential to be hindered. How do clinicians recognise such negative impacts? What are the strategies to prevent detriment to patients’ mental health in practice?

Dr Toni Pikoos

PHD (CLINICAL PSYCHOLOGY);

Dr Toni Pikoos

PHD (CLINICAL PSYCHOLOGY);

Iwrite this article, while simultaneously having one eye on Instagram and another on incoming Whatsapp notifications on my smartwatch. I’d hazard a guess that many of you can relate to this. And it’s no surprise –more than half of the global population are active social media users, including 82.7% of Australians.1 This number continues to rise each year with the advent of more social media platforms and increasing access to digital technology.

The most active social media users are aged 18–34 years, however, newer platforms like TikTok, are reaching an increasingly younger audience. TikTok’s most active users are between 10–19 years old,1 an age where cognitive and identity development are still in their infancy.

While social media use can have several benefits, such as social connectedness during the COVID-19 pandemic, maintaining close relationships with overseas friends and family, increasing confidence in shy or socially anxious individuals, and an educational resource, 2 there is accumulating evidence about the negative effects of social media on mental health. Greater engagement with social media has been linked to a higher incidence of depression, anxiety, loneliness, poor body image, eating disorders, and sleep disturbance. 3

The relationship between social media and negative mental health outcomes occurs primarily through three pathways:

1Social media use becoming ‘addictive’ or problematic

2Social media use as a maladaptive coping strategy

3Through the effects of ‘triggering’ social media content.

Up to 73% of teens and adults feel that they spend too much time on social media (the current global average is 147 minutes per day).4 Beyond the duration of use, problematic social media use (which occurs in 10–44% of young adults)5 is also characterised by:

1Thinking about social media frequently

2An inability to stop using social media, despite negative consequences (e.g., arguments with loved ones, or distraction from homework or work tasks)

3Persistent neglect of health (e.g., sleep) or interference with important life domains (e.g., work, school, social life) due to social media usage

Problematic social media use, as opposed to general social media use, has been more consistently linked to negative mental health outcomes including greater depression and loneliness, and lower self-esteem. This is partially mediated by the effect of problematic use on sleep, which in turn leads to poorer mental health functioning.3 Sleep can be affected in several ways, such as spending time on social media late at night leading to increased arousal, reducing the time available for sleep, and the bright screen lights disrupting melatonin secretion.6 Could you imagine trying to fall asleep in the middle of a

party? Social media use before bed is much the same.

Social media can also be used as a maladaptive coping method, including:

1Mindlessly scrolling as a distraction from difficult emotions or facing life problems7

2Reaching out to others for support via social media, in place of face-to-face emotional support. This has been associated with an increased perception of social isolation8

3Presenting an idealised image of oneself, which doesn’t fit with how we feel internally. In turn, this can fuel a disconnect between emotions and how we present to the world

4Seeking validation from others when feeling insecure, through posting videos, images or ‘selfies’

While many of these behaviours are aimed at reducing distress, they generally only provide a brief sense of relief, without addressing the underlying issue. They are also often used in place of healthier or more effective coping strategies, such as physical activity, relaxation or reaching out to loved ones for support. In turn, social media acts as a band-aid but not a cure.

Some argue that the most harmful aspect of social media is not the quantity of use, but rather the quality – the type of content that people may seek out or be exposed to while

Negative aspects of social media use

Distraction & reduced productivity

‘Addiction’ or compulsive behaviours

Sleep difficulties

Reduced engagement with friends and family ‘Triggering’ content

Avoiding difficult emotions

scrolling. In several reviews, consuming and posting imagebased content on social media has been linked to poor body image (our thoughts, feelings and perceptions of our body) and increased engagement in disordered eating behaviours.9

Social media is thought to contribute to appearance dissatisfaction and disordered eating by:

1Promoting unrealistic beauty standards, where users only post the best images of themselves, which are often digitally enhanced

2Facilitating comparisons to others on social

NEGATIVE IMPACT OF SOCIAL MEDIA

Problematic or ‘addictive’ social media use

Distraction and reduced productivity

Social media as an unhealthy coping strategy

Triggering social media content

Sleep difficulties

Reduced social connectedness

media, who we perceive as more successful, popular or attractive than ourselves

3The circulation of unhelpful advertising or trends, such as ‘fitspiration’ or ‘thinspiration’ where individuals share their fitness or weight loss journeys in the hope of inspiring others to do the same, inadvertently encouraging disordered eating or exercise behaviours.10

Content that reflects themes of suicide and self-harm also regularly gain traction on social media. While most platforms have safeguards in place to

block harmful content, many find ways to circumvent these limitations. Self-harm-related social media content has been criticised as normalising these behaviours and potentially sparking ‘contagion’. However, others argue that this content may have positive consequences in allowing affected individuals to find a supportive community or information about reducing self-harm when ashamed to discuss it in person.11

The short answer is; it depends. While a large body of evidence

POSSIBLE STRATEGIES

• A ‘digital detox’ i.e., an extended period away from social media which could include deleting apps or disabling certain accounts

• Cognitive-behavioural therapy to address the relationship between beliefs, emotions and dependence on social media

• Set time limits around social media usage, using in-built features in apps or on the device

• Have dedicated ‘phone-free’ times during the day

• Having intentional phone-free periods, particularly when feeling distressed

• Engage in other coping strategies e.g., mindfulness, journaling, relaxation or time with friends and family

• Report, unfollow, skip, or request to see less harmful or triggering content

• Develop social media literacy i.e., learning to challenge the unhelpful messages that may be propagated through social media

• Turning off screens a while before bedtime

• Engaging in sleep hygiene strategies to promote better sleep

• Put away phones when spending time with family or friends

• Practice mindful attention by remaining present and actively tuning into the conversation

indicates that social media can negatively affect mental health, imposing limits on social media use may be an unrealistic recommendation in an increasingly digital society.

The relationship between social media and mental health is a nuanced and personal one. For some, social media may distract and disconnect them from the world around them or act as a trigger for unhealthy behaviours. For others, it may provide a community that inspires, motivates and helps them to develop a healthier sense of self. As more research accumulates,

problematic social media use may well be recognised as an official diagnosis, along with other behavioural addictions.

Preliminary evidence suggests psychological treatments, such as cognitive-behavioural therapy can help individuals with problematic social media use break unhealthy patterns.12 Others may benefit from a personalised approach (for suggestions, see Table 1) to help turn social media into a friend, rather than a foe.

2021;92(2):761–779.

Suicide is a major concern within Australian society, with over 3000 deaths and close to 65,000 attempts every year. Given its prevalence, suicide prevention is a widespread national priority and can be carried out through implementing strategies across the continuum of care – early intervention, prevention, response and aftercare.1 Interventions can include those aimed at an individual level such as screening to identify those at high risk, safety planning, psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy or follow-up care. Other interventions are aimed at the population-level – education and awareness programs, increasing social inclusion, or improving media reporting guidelines.

Dr Lydia Sequeira

Dr Lydia Sequeira

Over the past decade, and more specifically since the onset of COVID-19, there has been a rapid increase in the use of technologies such as websites, smartphone apps, SMS texting, and videoconferencing technologies for delivering mental healthcare. When thinking about suicide prevention, in particular, the use of these digital technologies allows for interventions to have widespread reach even in rural and remote areas through relatively costeffective delivery, since a lot of the infrastructure (i.e., mobile phones, internet) is already present. Immediate crisis support offered through organisations like Lifeline Australia, Kids Helpline, Suicide Call Back Service and 13YARN are all examples of phone or online

counselling that can help expand geographical access to crisis counsellors.2

Digital suicide prevention interventions can also offer services that are tailored to specific preferences or languages and are culturally relevant. Suicide Prevention Australia reports that populations at highest risk of suicide across Australia include Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people (amongst others in the LGBTI+ community, individuals bereaved by suicide and those who have previously attempted suicide). To this end, the Black Dog Institute has created the iBobbly app, which can be downloaded and used on smartphones or tablets. This self-help app focuses on social and emotional wellbeing for

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, incorporating metaphors, images, videos and stories drawn by Aboriginal artists and performers. The creation, ongoing updates and implementation of this app are done in collaboration with an advisory group of individuals who identify as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander – an inclusive process known as “co-design” or “participatory design” where individuals who the digital intervention is meant for are included within the design and build. 3 This kind of active engagement with individuals with lived and living experience is, fortunately, becoming more common across digital health and healthcare more broadly, embodying the principle “Nothing About Me, Without Me”. Besides populationspecific interventions, there are also mobile and web apps

that incorporate suicide prevention strategies such as safety planning - a safety plan is a document that can remind an individual of their reasons for living, coping tools and other important pieces of information to avoid a state of intense suicidal crisis. This process can be done alongside a provider or a trusted care partner, and apps such as Beyond Now help make this process accessible through customisable safety plan templates and prompts. Digital safety planning can also help an individual easily share their plan with their care team, family and friends through e-mail or by texting over a screenshot. This act of sharing can increase awareness of warning signs amongst family and friends, and help them identify a possible crisis. Another suicide prevention strategy that has been translated into the

digital realm is brief contact interventions following a suicide attempt. Originally done through sending letters, ongoing research is looking to understand the usefulness of Reconnecting After SelfHarm (RAFT) - an automated text-message service that provides individuals with supportive messages and links to online therapeutic modules in the weeks and months after they have been discharged from the hospital.4

Beyond digital counselling, brief-contact and self-help interventions, the digital suicide prevention umbrella has also expanded to include exploration within the field of predictive analytics. Predictive analytics uses large data sets and complex data analysis techniques to “predict” future unknown events. Since suicide is a complex phenomenon with many risk factors and protective factors contributing

towards it, providers can sometimes find it challenging to assess whether their patient is at a high risk of attempting suicide, leading to potential missed opportunities in follow-up treatment or care. While the cognitive load involved in analysing more than 50 risk and protective factors is high for humans, this is a task done relatively easily by computers.

Researchers across the globe have started using clinical data found within electronic health records (EHRs) to develop algorithms that will make it easier to flag individuals at a high risk of suicide so that clinicians are supported in their treatment decisions. However, in order for the algorithms to make unbiased predictions, the data

sets need to be representative of the population. When these algorithms begin to get implemented into clinical care to support clinicians, it is important to also think about how individuals who are deemed high risk can access appropriate levels of follow-up care and treatment –whether this is through virtual or in-person modalities.

Moreover, while EHRs contain a wealth of routinely collected information, the regularity of this data collection depends on the person’s interaction with their providers. There can still be crucial periods within an individual’s life that are not captured within EHR data, and these points can be missed in clinical decisionmaking. An emerging concept called ecological momentary assessment is aimed at gathering behavioural data right when events happen

Several organisations offer digital support that expand geographical access to counsellors:

Lifeline Australia, Kids Helpline, Suicide Call Back Service and 13YARN

Population-specific digital suicide prevention interventions exist for patients who identify as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people (iBobbly app) or part of the LGBTI+ community, and individuals bereaved by suicide or have attempted suicide

Mobile and web apps incorporate customisable suicide prevention strategies with prompts i.e., digital safety planning ( Beyond Now), automated textmessaging services ( Reconnecting After SelfHarm (RAFT), online therapeutic modules. Patients can share data with their care team, friends or family to identify warning signs

Use of predictive analytics improves digital interventions by predicting future suicide attempts, allowing clinicians to provide follow-up care and treatment where needed

EHRs are being used to develop algorithms that flag high-risk individuals for suicide

within a person’s daily life through smartphone or web apps – tools that are able to capture the fluctuations of suicidal thoughts and behaviours. As with all digital suicide prevention technology, but especially with moment-to-moment data capture, considerations of the security and confidentiality of data are crucial. Even though we have had large advances in the conversation around mental health and illness, there is still stigma associated with reaching out for help, and any privacy violations through such tools can diminish patient trust within the healthcare system. All things considered, for technology used for suicide prevention to be helpful and not harmful, we must ensure that it is designed alongside individuals with lived experience, and be validated both clinically and technically.

Ecological momentary assessment is an emerging concept that captures moment-to moment behavioural data, but we need to consider the security of confidential patient data

1. Suicide Prevention Australia, 2020. Guiding principles of suicide prevention. Available at: www. suicidepreventionaust.org/wpcontent/uploads/2020/08/GuidingPrinciples-Policy-Position_Fnl.pdf

2. Reach Out Australia, 2022. Urgent help. Available at: au.reachout.com/ urgent-help

3. Black Dog Institute, 2022. iBobbly. Resources & support : digital tools & apps. Available at: www. blackdoginstitute.org.au/resourcessupport/digital-tools-apps/ibobbly/ 4. Black Dog Institute, 2022. RAFT: reconnecting after self harm. Research projects. Available at: www. blackdoginstitute.org.au/researchprojects/raft/

Digital tools are becoming more commonplace in our everyday lives and in the delivery of psychiatric care. Since the onset of the pandemic, patients are now being seen from the comfort of their own homes through platforms like, Zoom and Microsoft Teams. In addition, an overwhelming number of mental health apps are now available to support a range of functions related to treatment, management and support. At the click of a button, individuals can now instantly access libraries of patient education materials, record their daily symptoms, complete self-assessments, and message their clinicians.

While digital tools have undoubtedly changed the way clinicians connect with patients and deliver care in their practices, how do we know whether these tools are effective? In particular, which ones are effective and acceptable for various populations and for what purpose? Recent reviews on the evidence of digital health apps for use in clinical settings have found that only a limited number of these tools have been rigorously evaluated and based on scientific merit.1 This can be particularly problematic as we begin exploring the use of mobile apps and digital tools as part of psychiatric practice. By adopting tools with erroneous instructions and information that may not be conducive to patient care, it can lead to suboptimal adoption of the tool, jeopardise overall treatment progression/therapeutic relationship and ultimately cause more harm than good (or perhaps be a waste of time for a patient). As such, there is a great need to evaluate and understand which digital tools ‘work’ for

what population and for what purpose. In this article, I provide a brief overview of some of the initiatives and foundations on evaluating digital health tools and how this may be relevant for your practice.

Given the recent focus on reviewing and evaluating digital health tools, several healthcare organisations have launched their own initiative to evaluate digital health tools.

The American Psychiatric Association has launched their App Advisor program which aims to help clinicians and healthcare professionals select an app for patients to use. Using the associated Comprehensive App Evaluation Model developed by a panel of experts, mental health apps can be evaluated on a number of components including access, privacy, clinical evidence, usability and therapeutic goal. Based on these findings, clinicians can have practical guidance in selecting and recommending apps to their

patients in practice. In Australia, the Black Dog Institute is one of many organisations that are working on developing digital health apps with these components in mind.

However, with regards to evaluating digital health tools, there is currently no gold standard for digital technologies, as it largely depends on the purpose and question to be answered. Is the question about whether a digital tool is acceptable for a certain population, or are we curious about whether the tool is effective to support management of a certain psychiatric condition? While the approach towards evaluation will differ based on the question of interest, several frameworks can be used to guide the development and process (e.g., the outcomes to collect, the approaches). In particular, the Benefits Evaluation Framework and the Sociotechnical Model are popular frameworks that

outline the various components (e.g., people, processes) that should be considered in evaluating digital tools.2,3 Use of these frameworks can help inform the collection and analysis of data to produce a comprehensive view of how the technology works in a specific environment and population. Understanding these findings can be critical in uncovering the opportunities and challenges that hinder the safe and effective use of the tool. For example, in a recent evaluation on virtual care tools in Victoria, Australia, Gray and colleagues did a thorough investigation of the complex relationships using the sociotechnical model to better understand the deployment of the virtual care tools in their environment.4 These findings led to an understanding of its complex relationships with the environment, and the success factors and barriers of each tool. Thus, these frameworks can be useful to look at how

digital tools can be effective and support or hinder current practices, workflows and models of care. More notably, these frameworks can also be used in concert with co-design approaches and implementation science frameworks (e.g., the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research - CFIR) to help support the implementation of these tools in a meaningful and considerate manner.

Evaluating digital tools have become critical puzzle pieces for building models of care that encompass digital technologies. For example, with the widespread adoption of virtual care, evaluation studies have been useful to understand the circumstances and situations where virtual use of technologies may not be effective or useful. This has since led to guidelines that help clinicians decide when virtual care is suitable, and when in-person appointments are more appropriate. Likewise, for mobile apps, given the diverse range of tools that are available, the Stepped Care Model 2.05 is a novel model of care that focuses on untangling the diverse range of tools that are available for patients.5 Depending on the level of acuity of the patient, clinicians can select tools that match the needs of the patient and adjust the prescribed tools as patients improve or deteriorate in their condition. While these guidelines and models are still early in infancy, they are expected to pave the way for transforming psychiatric practice through and with digital tools.

Evaluating digital tools have become critical puzzle pieces for building models of care that encompass digital technologies.

The mental healthcare system is rapidly changing as it adopts digital forms and solutions in care delivery. With higher demand for apps to support patients’ needs and exponential growth in the tools available, how do clinicians navigate the plethora of resources at hands-reach?

Iman Kassam MHI

Iman Kassam MHI

With the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, healthcare systems globally shifted from in-person models to digital forms of care delivery. The rapid uptake and growth in digital health solutions during the pandemic has resulted in a plethora of solutions for providers and consumers to sift through and pick from.

While digital health tools designed to support or prevent a decline in one’s mental health and well-being come in a variety of forms, mobile health apps are most common.

Given the rise in demand for mental health support and services, mental health apps are increasingly being leveraged by individuals to support or augment various stages of

peer support group or chatbot, while others are more selfguided focusing on symptom tracking or self-care. This rise in demand has also resulted in what some describe as the ‘wild west’ of mental health apps.1 Prior to the pandemic, the mental health app space was growing exponentially with roughly 10,000 mental health apps available on app stores in 2017 (e.g., Apple App Store, Google Play Store, etc.).2

In 2021, this figure doubled with an estimated 20,000 mental health apps available for individuals to use on app stores. 3 Given the sheer number of apps available, a common concern among those wanting to use apps to support their mental health is: how do I choose an appropriate app?

To combat this issue, some organisations have developed curated lists of mental health apps, otherwise known as app libraries, to assist in selecting digital mental health apps. Common barriers to utilising mental health apps and other digital mental health tools include being unaware of what is available to use, and where to find such tools. App libraries aim to bridge these barriers by synthesising and categorising apps into large searchable, filterable, and sortable databases. There is a multitude

available for use, each containing thousands of apps that have been reviewed and curated. A UK-based app library, ORHCA , was launched in 2016 with the purpose of curating and evaluating health apps. Similarly, One Mind Psyber Guide, a US-based app library, specifically includes mental health apps that have been evaluated based on the app’s credibility, user experience, privacy policy transparency and availability of professional evidence. In Australia, a number of government health agencies and healthcare organisations have developed and published curated app libraries that can be accessed freely by the Australian public. Head to Health, a digital mental health service provided by the Australian Department of Health, has synthesised a searchable list of Australianbased mental health apps for the general population. Other Australian organisations with app libraries include Kids Help Line, ReachOut, and the Black Dog Institute These app libraries present several curated mental health apps and also include apps for specific Australian populations (e.g., youth and young adults, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples). App libraries

mental health; however, further consideration is needed when determining whether an app is well suited for the user.

While it may be convenient to choose an app that is highly rated or frequently advertised, going the extra mile in making an informed choice can help in selecting an app that’s best for you. Some app libraries (e.g., One Mind Psyber Guide, MindApps) have done the evaluation leg work for users by presenting information on various components and features of the app. These app libraries leverage app evaluation frameworks, such as the American Psychological Association App Evaluation Framework , to compile information that can, in some cases, be challenging for app users to navigate or gather themselves. They are frequently maintained and updated, providing users with the appropriate information to make an informed choice. App libraries and evaluation frameworks can be used by a variety of audiences, whether that be individuals wanting to support their mental health or clinicians wanting to recommend a tool to their patients. Mental health apps can aid individuals in better maintaining and sustaining their well-being. They may also

Beyond the use of app libraries or evaluation frameworks, when wanting to try out an app to support your mental health, keep the following in mind:

• Evidence & Credibility: Is the app credible? Is there evidence (e.g., research, reports) to support its effectiveness?

• App Developer: Who was the app developed by (e.g., not-for-profit vs. for-profit developer)?

• Ease of Use: Is the app usable and accessible?

• Privacy Policy

Transparency: How transparent is the app’s privacy policy? Does it outline how the app’s data is collected, used, shared and protected?

• Appropriateness: Who is the target population for this app? Is it geared towards the general population or specific cultural or clinical groups?

As apps become more pervasive in the mental health space, being able to identify the good from the bad is imperative. Choosing an app that supports your mental health and is also trustworthy and evidence-based, can be a daunting task. Using app libraries and app evaluation frameworks to navigate the

As apps become more pervasive in the mental health space, being able to identify the good from the bad is imperative.

Approximately 14% of Australians have an anxiety disorder, and around 1 in

individuals will experience generalised anxiety disorder (GAD) within their lifetime.1–3 Since our 10-year review of Agomelatine in the last issue of Inside Practice’s Psychiatry Publication, as of May 2022 the Therapeutic Goods and Administration (TGA) has approved the use of agomelatine (Valdoxan®) in GAD.4

GAD is characterised by frequent and excessive worrying over everyday things (e.g., family, work, relationships) to the point that it impairs the ability to the function in daily life. People with GAD are also troubled by somatic symptoms of persistent restlessness, feeling on edge, sleep disturbance and muscle tension. 5 Typically, the condition is diagnosed in the early thirties, albeit many sufferers say that they have ‘always been worriers’.

It is 2–3 times more likely to affect women than men.4,6 The chronic nature and burden of GAD is underlined by the fact that many patients are still affected by symptoms 10 years after initial diagnosis and 50% relapse after remission.7,8

Initial treatment for GAD should involve 8–12 sessions of cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT; via face-to-face with a psychologist or digital CBT) over 4–6 weeks. However, in patients with moderate-to-severe GAD (or those unable to engage with psychological treatment) CBT can be used in combination or switched with medications. 5 While antidepressants such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin–noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) have remained as first-line for the pharmacological treatment

of GAD due to established evidence supporting efficacy and safety, as well as low misuse potential,9,10 many patients have an inadequate response and are unable to tolerate adverse effects.11 Other treatments for GAD, such as benzodiazepines and pregabalin (not indicated in Australia but used off-label overseas and approved in Europe), also have proven efficacy but there are major concerns over side effects (i.e., cognitive impairment, falls and sedation) and the potential for long-term dependence (specifically when using benzodiazepines). 5,12,13 In such cases when a patient fails to respond or experiences adverse side effects to treatment, the need for a drug that improves tolerability and response to treatment is warranted.

Agomelatine is a melatonergic antidepressant which expands the therapeutic options for GAD.1,13 It is believed that the mechanism of action of agomelatine lies in it being both an antagonist at 5-HT2C receptors (anxiolytic effects) and agonism of melatonin (MT1 and MT2) receptors (improves sleep and circadian rhythms).14–16 Through targeting different receptors to SSRIs/ SNRIs, use of agomelatine avoids unwanted effects such as sexual dysfunction, emotional blunting and weight gain.16

The TGA approval of agomelatine in GAD comes after review of the efficacy and safety of agomelatine (25mg and 50mg) in treating >1,100 patients with GAD across several randomisedcontrolled trials (RCTs).4 This review focusses on the three relevant short-term (12 weeks) and one long-term (6 months) placebo RCTs.17,18

In a meta-analysis of the short-term RCTs, the primary outcome was assessed using the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A) total score, which

consists of 14 items to define severity of anxiety symptoms both psychic (mental agitation and psychological distress) and somatic (physical complaints related to anxiety).17,18 Results demonstrated statistically significant superiority of agomelatine compared to placebo in HAM-A at week 12 (between group difference: 6.30 ± 2.51, p = 0.012; Table 1).17 Significant effects were also found in observing HAM-A with better response rates by 32.6% and symptom remission by 21.7% for agomelatine when compared to placebo (Table 1).17

Additionally, these RCTs assessed functional impairment using the Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS) across various parameters (i.e., work/school,

social and family/home).17

Significant improvements in global functioning were found to favour agomelatine (25mg and 50mg) over placebo in SDS total score (7.6 ± 6.7 vs. 13.2 ± 7.7; 95% CI: [1.57; 8.66], p=0.005), response (79.1% vs. 43.2%; 95% CI: [15.41; 51.32], p<0.001) and remission (55.2% vs. 25.36%; 95% CI: [19.48;39.55], p<0.001)).17

Secondary analysis found agomelatine improved LSEQ ratings of getting off to sleep (p=0.002), quality of sleep (p<0.001) and integrity of behaviour (p=0.049).19

A subset population analysis of patients with severe GAD (HAM-A total score at baseline ≥25) found results to be consistent with those

found in the whole population for symptom (HAM-A) reduction and functional (SDS) improvement.17

Long-term efficacy and prevention of relapse was evaluated over a 6-month period in the long-term RCT, where patients responding to acute treatment (16 weeks) with agomelatine (25mg or 50mg) were randomised to agomelatine 25–50mg or placebo.18 For

agomelatine, the relapse rate over time was significantly reduced –by 41.8% – compared to placebo (95% CI: [0.341; 0.995], p=0.046) (Figure 1).18 A greater reduction in rate of relapse was also found in those with severe GAD – by 59.3% (p=0.006).18 An absence of discontinuation symptoms was also observed after abrupt cessation of agomelatine after week 42, with no apparent difference in symptoms between

those continuing treatment and those who had withdrawn.18

Across all RCTs reviewed here, agomelatine was well tolerated with low rates of adverse events.4,17,18 In the short-term RCTs, agomelatine and placebo showed similar risk of at least one adverse event (44.3% vs. 41.3%, respectively).17 Whilst for long-term tolerability, agomelatine had a higher occurrence of at least one adverse event than placebo (40.7% vs. 27.2%, respectively).18

The most common adverse events reported were headaches, nasopharyngitis, nausea and dizziness, which presented mostly during the first two weeks of treatment and were also frequently reported by placebo groups.4,17,18 Overall risk for serious adverse events for agomelatine was equivalent to placebo (1.2%) in the shortterm RCTs metanalysis,17 whilst no reports of serious adverse events were found in the long-term RCT.18

There has been concern over liver function impairment when using agomelatine due to increased levels of transaminases. Clinically significant transaminase

increases (ALT/AST ≥ 3ULN) were found in 13 patients during the short-term RCTs and 8 patients for the longterm RCT.17,18 However, these returned to normal ranges after discontinuation of treatment.17,18

Barriers still exist when using agomelatine to treat GAD in Australia, such as unavailability under the PBS, age parameters (18–64 years), and the requirement for liver function tests (LFTs) throughout treatment (baseline, 3, 6, 12 and 24 weeks after initiation and dose escalation).4,20 Some of these can be overcome, cost issues through private health reimbursement and in practice patient education to explain LFTs, whereby most patients are willing to accommodate additional monitoring. Others require further studies but there have been promising results from trials in elderly and younger patients,21,22 and direct comparisons to SSRI/SNRIs showing similar efficacy and better safety.23

1. Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2008. National survey of mental health and wellbeing: summary of results, 2007 (2008). Canberra: ABS.

2. Slade T, Johnston A, Oakley Browne MA, et al. 2007 National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing: methods and key findings. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2009;43: 594–605.

3. McEvoy PM, Grove R, Slade T. Epidemiology of anxiety disorders in the Australian general population: findings of the 2007 Australian National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2011;45(11):957–67.

4. Valdoxan® Approved Product Information, May 2022.

5. Andrews G, et al. Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of panic disorder, social anxiety disorder and generalised anxiety disorder. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2018;52(12):1109–1172.

6. McLean CP, Asnaani A, Litz BT, Hofmann SG. Gender differences in anxiety disorders: prevalence, course of illness, comorbidity and burden of illness. J Psychiatr Res. 2011;45(8):1027–35.

7. Newman MG, Llera SJ, Erickson TM, et al. Worry and generalized anxiety disorder: a review and theoretical synthesis of evidence on nature, etiology, mechanisms, and treatment. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2013;9:275–97.

8. Yonkers KA, Dyck IR, Warshaw M, et al. Factors predicting the clinical course of generalised anxiety disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;176:544–9.

9. Craske MG, Stein MB. Anxiety. Lancet. 2016;388(10063):3048–3059.

10. Ravindran LN, Stein MB. The pharmacologic treatment of anxiety disorders: a review of progress. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(7):839–54.

11. Craske MG, Stein MB, Eley TC, et al. Anxiety disorders. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3:17024.

12. Gale CK, Millichamp J. Generalised anxiety disorders. BMJ Clin Evid. 2011;2011:1002.

13. Strawn JR, Geracioti L, Rajdev N, et al. Pharmacotherapy for generalized anxiety disorder in adult and pediatric patients: an evidencebased treatment review. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2018;19(10):1057–1070.

14. de Bodinat C, Guardiola-Lemaitre B, Mocaer E, et al. Agomelatine, the first melatonergic antidepressant: discovery, characterization and development. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9(8):628–42.

15. Millan MJ, Brocco M, Gobert A, et al. Anxiolytic properties of agomelatine, an antidepressant with melatoninergic and serotonergic properties: role of 5-HT2C receptor blockade. Psychopharmacology. 2005;177(4):448–58.

16. Levitan MN, Papelbaum M, Nardi AE. Profile of agomelatine and its potential in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2015;11:1149-55.

Group Relapse Incidence of relapse at wk 26: SE [95% CI], p-value AGO (25–50mg) (n=113) n=22 (19.5%) 0.582[0.341; 0.995], 0.046 PBO (n=114) n=35 (30.7%)

AGO: agomelatine; CI: confidence interval; PBO: placebo; SE: standard error. Adapted from Stein DJ, et al. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73(7):1002–8.

At an individual patient level, the benefits of agomelatine for GAD include good tolerability as well as efficacy, extending to quality of life associated with improvement of symptoms (HAM-A) and functionality (SDS).4,17,18 Normalisation of function is particularly important for patients with GAD, as the disorder greatly impairs and restricts day-to-day life in multiple areas (work, family and social affairs).5,17 Furthermore, the side effect profile may be preferable to patients over SSRIs/SNRIs, which are commonly associated with sexual dysfunction, psychomotor agitation, poor sleep quality and discontinuation symptoms (after cessation of treatment).16–18 The TGA approval for agomelatine (Valdoxan®) in GAD, now provides a favourable treatment option, with simple dosing (one 25mg or 50mg tablet before bed), established efficacy and good tolerability.4

This article was made possible by Servier Australia. Servier had no editorial or writing input.

17. Stein DJ, Khoo JP, PicarelBlanchot F, et al. Efficacy of Agomelatine 25-50 mg for the treatment of anxious symptoms and functional impairment in generalized anxiety disorder: A meta-analysis of three placebo-controlled studies. Adv Ther. 2021;38(3):1567–1583.

18. Stein DJ, Ahokas A, Albarran C, et al. Agomelatine prevents relapse in generalized anxiety disorder: a 6-month randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled discontinuation study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73(7):1002–8.

19. Stein DJ, Ahokas A, Márquez MS, et al. Agomelatine in generalized anxiety disorder: an active comparator and placebocontrolled study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75(4):362–8.

20. The Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme, 2012. Agomelatine, tablet, 25mg, Valdoxan® - March 2012. pbs.gov.au/pbs/industry/listing/ elements/pbac-meetings/psd/201203/agomelatine

21. Heun R, Ahokas A, Boyer P, et al. The efficacy of agomelatine in elderly patients with recurrent major depressive disorder: a placebocontrolled study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(6):587-94.

22. Servier, 2015. Pharmacokinetics and safety of agomelatine in children (from 7 to less than 12 years) and adolescents (from 12 to less than 18 years) with Depressive or Anxiety Disorder. An open-labelled, multicenter, three-dose level, noncomparative study. clinicaltrials. servier.com/wp-content/uploads/ CL2-20098-075_synopsis_report.pdf

23. Dan J. Stein, Jon-Paul Khoo, Antti Ahokas, et al. 12-week double-blind randomized multicenter study of efficacy and safety of agomelatine (25-50 mg/day) versus escitalopram (10-20 mg/day) in out-patients with severe generalized anxiety disorder. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2018;28(8):970–979.

Issues remain in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), especially with regards to the lack of effective exposure and responsive prevention (ERP) treatment being utilised in patients. Traditional means of face-to-face treatment have become less accessible due to the events of COVID-19 and further contributed to this issue. There is a need to harness novel, safe and effective digital treatment approaches via the internet, smartphones and apps for OCD.

One of the longeststanding issues in psychological treatments for OCD is that of availability; too few patients receive effective treatment using ERP. This problem has been compounded in the past two years when social distancing and other measures to combat the spread of COVID-19 has meant that traditional faceto-face treatment has become less available in countries across the world. Safe and effective digital treatment options are therefore needed, and this article will take a closer look at current options in the treatment of OCD.

Internet-Delivered CBT Research on psychological treatments delivered via the internet has been ongoing for more than 20 years,1 internet-delivered cognitive behaviour therapy (ICBT) has been implemented into the regular healthcare systems in several countries.2 Compared to traditional face-to-face CBT, ICBT has multiple advantages in terms of accessibility. First, the treatment is delivered via an online platform that can be accessed from any device with an internet connection, and at a time convenient for

the patient. No longer do patients have to squeeze in psychotherapy sessions at a clinic into a busy schedule in order to receive treatment.

Further, many ICBT platforms enable patients to receive rapid feedback from their therapist via built-in messaging systems.

Current ICBT options for OCD resemble traditional faceto-face CBT and differ in mode of delivery rather than content.

The treatments emphasise ERP as the main component and include support from a therapist. 3–5 Since the first pilot trial was published in 2011,6 evidence for the efficacy of ICBT for OCD comes from multiple randomised controlled trials and meta-analyses which have found large improvements.7

However, ICBT treatments are typically deployed as standalone websites that are text-based, making them difficult to interact with from a smaller screen like a smartphone. The ubiquity of smartphones in many countries makes them a potentially important tool in further improving accessibility. Compared to a website that is best accessed from a tablet or computer, app-based treatments that are available on smartphones can be used throughout the day, as symptoms and difficult situations occur. Further, apps enable new data collection strategies, for example, using location and activity measurements to provide timely reminders (notifying patients about relevant exercises as they arrive at work or are at home), and monitoring mood to predict the course of a disorder.8 As promising

as these new approaches are, the evidence to date for using apps in the treatment of OCD is limited to using traditional ERP techniques, either in a smartphone-only treatment or in conjunction with traditional therapy.

One smartphone app called ‘nOCD’ has been designed to facilitate ERP exercises, and has been used alongside CBT delivered via face-to-face sessions or video calls with promising results.9,10 Another app, called ‘LiveOCDFree’ has been evaluated as a standalone treatment in a pilot trial, showing small reductions in self-rated OCD symptoms after 12 weeks of use.11 Thus, the evidence to date is limited to preliminary findings from uncontrolled studies. A meta-analysis of studies evaluating treatments for other disorders (mainly depression and anxiety disorders) found medium effect sizes, pointing to a reduced treatment effect compared to ICBT treatments with therapist support.12

There are several issues that need to be considered before recommending the use of smartphone apps in the treatment of mental disorders. First, many popular apps lack direct evidence of their efficacy. Although apps claim to use evidence-based techniques from CBT or other approaches, evidence for the

apps themselves is rarely available.13 Second, apps collect sensitive information about their users (such as responses to questionnaires, mood ratings and location data) which is sometimes shared with third parties. A survey of 36 popular apps for depression and smoking cessation found that 81% shared user data with third parties for advertising and marketing purposes.14 Unless explicitly stated in the app, clinicians should assume that data is being transmitted to third parties. Third, low user engagement remains a challenge with 6.7% of users reporting daily use of the app in the pilot evaluation of ‘LiveOCDFree’.11 This issue, however, is not unique to app-based treatments; for example, in large-scale implementations of ICBT, the module completion rates tend to be lower than in initial studies.15,16

In summary, research into ICBT for OCD has been ongoing for the past 10 years and the results have consistently shown that ICBT produces large improvements.

Implementation of ICBT into regular healthcare has taken place in several countries. There is burgeoning evidence for the use of app-based treatments, either as standalone treatments or in conjunction with face-to-face or video sessions. Evidence of efficacy from rigorous randomised controlled trials are however lacking.

Looking ahead, there are multiple exciting developments and unresolved questions relating to digital psychological treatments. First and foremost, there is a need for more rigorous studies of app-based treatments for OCD. This approach holds great

promise but we should not recommend apps before their effectiveness and data sharing practices have been properly vetted. The use of virtual reality (VR) in exposures has seen interesting applications in the treatment of other anxiety disorders, but studies in OCD are lacking.17 By using VR it is possible to create immersive environments which enable exposures that otherwise would have been difficult to complete. A separate remaining question is determining the optimal level of therapist support needed. While therapist support, in general, is associated with better outcomes in ICBT,18 patients in unguided ICBT treatments for OCD still benefit to some extent.19 As unguided treatments can be provided rapidly to a large amount of patients at a minimal cost, their role in a stepped-care pathway for OCD should be further studied.

Key Points for Practice

DIGITAL TREATMENT PROS CONS

Internetdelivered CBT

• Accessible from any device with internet connection

• Patients able to fit CBT into schedules

• Rapid feedback from therapists

• Evidence to support efficacy

Smartphone/ App-based treatment

• More accessible than ICBT

• Can be used when needed by patients throughout the day

• Possibility to collect more data (location, activity and mood monitoring) and predict disease course

• Notifications to help patients do exercises

• Can be used alongside faceto-face CBT

• Typically, website based making interaction harder via small-screen devices

• Patient may not be able to access throughout the day when difficult situations occur or symptoms worsen

• Lack of evidence to support apps themselves and newer approaches in OCD treatment (evidence only supports traditional ERP techniques)

• Apps currently available in treating OCD (without therapist support) are less effective compared to ICBT

• Confidential patient information can be shared to third parties

• Low user engagement

1. Andersson G. Internet interventions: Past, present and future. Internet Interv. 2018;12:181–8.

2. Titov N, Dear B, Nielssen O, et al. ICBT in routine care: A descriptive analysis of successful clinics in five countries. Internet Interv. 2018;13:108–15.

3. Andersson E, Enander J, Andrén P, et al. Internet-based cognitive behaviour therapy for obsessive compulsive disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Psychol Med. 2012;42(10):2193–203.

4. Wootton BM, Johnston L, Dear BF, et al. Remote treatment of obsessivecompulsive disorder: A randomized controlled trial. J Obsessive Compuls Relat Disord. 2013;2(4):375–84.

5. Mahoney AEJ, Mackenzie A, Williams AD, et al. Internet cognitive behavioural treatment for obsessive compulsive disorder: A randomised controlled trial. Behav Res Ther. 2014;63:99–106.

6. Andersson E, Ljótsson B, Hedman E, et al. Internet-based cognitive behavior therapy for obsessive compulsive disorder: A pilot study. BMC Psychiatry. 2011;11(1):125.

7. Wootton BM. Remote cognitive behavior therapy for obsessive compulsive symptoms: A metaanalysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2016;43:103–13.

8. van de Leemput IA, Wichers M, Cramer AOJ, et al. Critical slowing down as early warning for the onset and termination of depression. PNAS. 2014;111(1):87–92.

9. Gershkovich M, Middleton R, Hezel DM, et al. Integrating exposure and response prevention with a mobile app to treat obsessive-compulsive disorder: feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary effects. Behav Ther. 2021;52(2):394–405.

10. Feusner JD, Farrell NR, Kreyling J, et al. Online video teletherapy treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder using exposure and response prevention: clinical outcomes from a retrospective longitudinal observational study. J Med Internet Res. 2022;24(5):e36431.

11. Boisseau CL, Schwartzman CM, Lawton J, et al. App-guided exposure and response prevention for obsessive compulsive disorder: An open pilot trial. Cogn Behav Ther. 2017;46(6):447–58.

12. Linardon J, Cuijpers P, Carlbring P, et al. The efficacy of app-supported smartphone interventions for mental health problems: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. World Psychiatry. 2019;18(3):325–36.

13. Larsen ME, Huckvale K, Nicholas J, et al. Using science to sell apps: Evaluation of mental health app store quality claims. npj Digit Med. 2019;2(1):18.

14. Huckvale K, Torous J, Larsen ME. Assessment of the data sharing and privacy practices of smartphone apps for depression and smoking cessation. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(4):e192542–2.

15. Flygare O, Lundström L, Andersson E, et al. Implementing therapist-guided internet-delivered cognitive behaviour therapy for obsessive compulsive disorder in the UK’s IAPT programme: A pilot trial. Br J Clin Psychol. 2022;00(00):1–6.

16. Luu J, Millard M, Newby J, et al. Internet-based cognitive behavioural therapy for treating symptoms of obsessive compulsive disorder in routine care. J Obsessive Compuls Relat Disord. 2020;26:100561.

17. van Loenen I, Scholten W, Muntingh A, et al. The effectiveness of virtual reality exposure for severe anxiety disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder: Meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2022;24(2):e26736.

18. Musiat P, Johnson C, Atkinson M, et al. Impact of guidance on intervention adherence in computerised interventions for mental health problems: A meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2022;52(2):229–40.

19. Lundström L, Flygare O, Andersson E, et al. Effect of internet-based vs face-to-face cognitive behavioral therapy for adults with obsessivecompulsive disorder: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(3):e221967.

The COvid-19 and you: mentaL heaLth in AusTralia now survEy (COLLATE) project is an ongoing mental-health survey that continues to identify and track the mental health of Australian adults throughout the COVID pandemic. This article provides updated findings with regards to the mental health of the general public across the last 2 years, with particular reference to quality of life (QoL).

In April 2020, data from COLLATE established that in the general population (N=5,149), levels of depression, anxiety and stress were about three times higher than levels reported pre-pandemic.2

Modelling that examined possible factors that might predict levels of negative emotions established several risk factors of importance.

These included being young, female or having a mentalillness diagnosis. Increased negative emotions in our middle-aged respondents were associated with increased childcare duties and/or financial stresses. Given the current financial climate, further mental-health consequences are likely for those undergoing continued financial stresses.

In the general population, levels of depression and anxiety have remained relatively stable and high from April 2020 to April 2022 (NB a total of 8,843 individuals provided a total of 12,288 survey responses over the 2-year period, with approximately 1,000 individuals completing surveys on two or more occasions). However, over the same 2-year time period, stress levels have reduced by approximately 18%.

These trends can be seen in Figure 1 (unpublished data).

Further, specific Victorian analyses comparing negative emotion levels between strict lockdown periods with periods when restrictions were not so severe demonstrated that negative emotions, particularly depression, were exacerbated during these strict lockdown periods (NB analyses for this paper occurred between April 2020 and September 2020).3

Analysis from previous natural disasters and pandemics have emphasised that as the immediate stress and anxiety with regards to the event diminishes, depression can continue to worsen over time. The emergence of depression is a delayed response to prolonged extreme stress/ anxiety. The COLLATE project will allow us to examine whether such trends are evident in Australia as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

In addition, the COLLATE project demonstrated that high levels of negative emotions in the general population

of Australia were related to hallucination-like and delusionlike behaviours, especially in the context of continued loneliness.4 Indeed, the previous research literature has established a link between loneliness and the emergence of psychotic illness. Given the number of lockdowns and prolonged periods of social isolation and loneliness across Australia in the last 2 years, health professionals need to have increased awareness that this could exacerbate psychosis and psychotic-like illnesses. It also suggests the importance of public-health campaigns to tackle such negative psychological outcomes, and dedicated interventions

targeting loneliness, might be warranted moving forward.

QoL is an important factor relating to mental health. We measured QoL using the EUROHIS-QOL, a brief 8-item measure in which higher scores indicate better QoL. Normative data from the United Kingdom using the EUROHIS-QOL in 2006 reported mean scores of 32 (standard deviation=4.9). The COLLATE data demonstrated that QoL was approximately 8% (or 3 points on the EUROHIS-QOL) lower when the pandemic hit in April 2020 in Australia. However, what is more concerning is that from April 2020 to April 2022 there has been

Depression and anxiety levels have remained elevated for a 2-year period

Across 2022, stress levels have been gradually reducing

As might be expected, strict lockdowns do have a negative impact on depression, anxiety and stress levels

Careful monitoring for the emergence of psychotic symptoms is recommended, especially for individuals who have experienced continued loneliness during the pandemic

QoL, often referred to as life satisfaction, has continued to decline over the last 2 years. This might be compounding poorer mental health outcomes

Pet owners have reduced quality of life during prolonged lockdowns

People with higher levels of depression use few adaptive coping strategies. Thus, encouraging people with depressive symptoms to use self-help strategies like challenging negative thoughts, keeping busy around the house and reaching out for support from loved ones can help protect against negative mental-health outcomes6

a further 6% drop in QoL ratings (equivalent to 1.75 points on the EUROHIS-QOL). See Figure 2 for these data (unpublished data).

Pre-pandemic evidence has implied that owning a pet reduces depression and improves QoL. However, contrary to expectations, findings from COLLATE demonstrated that during the pandemic lockdowns, owning a pet reduced owners’ QoL. It was proposed that pets may contribute to increased burden among owners;5 strict lockdown restrictions may have disrupted both pets’ and pet owners’ regular routines (e.g. dog walking), thus diminishing QoL.

Lower QoL may underpin some of the poor long-term

mental health outcomes found among individuals most impacted by COVID-19. Thus, encouraging adaptive coping strategies may assist with improving QoL and ultimately improve negative emotions. There are a number of adaptive coping strategies that have shown to be useful, including reaching out to loved ones, exercising, focusing on what you are grateful for and challenging negative thoughts.6 It is lastly important to recognise that people with high levels of depression, anxiety and stress should be prioritised in terms of seeing a mental health professional, as they are often not able to use other adaptive coping strategies.

The past few years have led to a fundamental shift towards the widespread adoption of digital technologies in core mental healthcare delivery. Alongside COVID-19 fuelling the adoption of telehealth as a means of connecting with patients, there has been substantial growth in the demand for national services that deliver mental health interventions online or by telephone. Although accelerated by the pandemic, this is part of a long pattern of increased adoption of digital mental healthcare as a complement to traditional in-person provision.

The Australian Government has funded multiple digital mental health providers for over a decade, contributing to Australia’s status as an international leader in this area. Organisations such as Beyond Blue, Black Dog, Reach Out, Sane Australia and many others make mental health information readily accessible and help people with mental health problems connect on online forums. Alongside this, organisations such as Lifeline have had a critical role to play in crisis management by telephone or text chat. Recent policy has supported a continuing expansion of digital providers, with recent public inquiries into mental health service delivery concluding an integral role for digital mental health services in improving access and scaling the delivery of mental health treatment.1,2

The term digital health refers to any use of digital technology in healthcare, spanning areas such as electronic medical records, use of different types of software to provide assessment and treatment, new technologies such as virtual reality, and the application of advanced analytic methods to big data. However, in mental health treatment delivery, arguably the most well-evidenced type of digital mental health interventions are self-directed online mental health programs, and increased use of these was a particular recommendation of the Productivity Commission inquiry into mental health.1

Online mental health programs are typically modular courses that provide a structured therapeutic intervention completed over a series of weeks, most often based on cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), which, as well as being well established in the treatment of low prevalence disorders, involves materials and exercises that can be easily adapted to this format of delivery. Programs typically include interactive exercises, and video and audio material alongside text content. These are most often made available as web-based programs,

which means they can be accessed via a browser across different devices including computers and smartphones. Incorporation of guidance or support from a practitioner can have a role in encouraging engagement with the program, supporting application to daily life, and individual tailoring. Hence, practitioner guidance is often integrated via email (or similar asynchronous messaging systems), or real-time interaction via telephone, videoconferencing and/or text chat.

In Australia, key providers of therapist-supported online programs include Swinburne University’s Mental Health Online (MHO), Mind Spot, established by Macquarie University, and This Way Up, run by St Vincent’s Hospital Sydney (see Table 1 for details). These services each offer a range of courses for different presentations which are free to the user. MHO and Mind Spot each offer a remote therapist support option, with MHO using a combination of email support and (optional) real-time video sessions, and Mind Spot offering practitioner support by telephone. This Way Up, on the other hand, is designed for use in conjunction with the person’s existing primary care or mental health practitioner,

who can access information on how to support the person whilst using the program.

Effectiveness

There is substantial evidence for the acceptability and efficacy of guided online CBT programs in treating low prevalence disorders, with meta-analyses showing large effect sizes on depression and anxiety outcomes, 3-5 including in effectiveness trials in routine care settings.6 Furthermore, when contrasted with traditional therapy delivery formats, meta-analyses have found guided internet-delivered CBT to be at least equally effective as traditional CBT for depression, 5,7,8 and anxiety disorders.7,8 With Australian programs specifically, a recent independent evaluation of MHO, Mind Spot and This Way Up concluded that users were highly satisfied with these services, and that randomised trial data on their programs obtained effect sizes comparable with those observed for in-person therapy.9