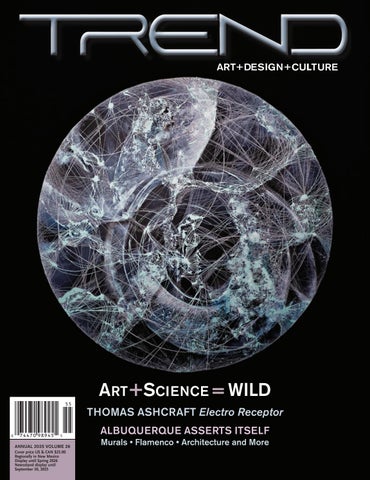

ART +SCIENCE = WILD THOMAS ASHCRAFT Electro Receptor ALBUQUERQUE ASSERTS ITSELF ANNUAL 2025 VOLUME 26 Cover price US & CAN $25.00 Regionally in New Mexico Display until Spring 2026 Newsstand display until September 30, 2025

Murals • Flamenco • Architecture and More