bopeep junction AND TUNNEL

At Bopeep Junction the SER and LBSCR routes from Tunbridge Wells and Lewes respectively converged for the final 1½ miles eastwards to Hastings. Located on what is now the East Coastway line, just beyond the junction is the 1,309-yard Bopeep Tunnel, then St Leonards Warrior Square station (qv). The tunnel, cut into the side of a hill known as Bo-Peep on an 1804 map, was built in 1851 by the SER, and suffered many problems with geology and underwater springs. From 1885 until 1906 it contained only a single track due to reduced clearances; it was reconstructed in 1906, and again in 1950.

The location was named after the Bo-Peep public house in Bulverhythe, a Hastings suburb also known as West St. Leonards and Bo-Peep. Until the late 18th century the pub was the New England Bank; it subsequently had four name changes and was rebuilt at least twice. As a pub it was associated with smuggling

along that section of coast. In 1815 it was described as ‘a wretched public house by the roadside’, and in 1828 as a desolate spot midway between Hastings and Bexhill. The location was marked by an ‘evil-looking inn’ to which were attached still more evil-looking Pleasure Gardens.

It is suggested that the well-known nursery rhyme ‘Little Bo Peep’ is not about a careless shepherdess, but that ‘Bo Peep’ refers to Customs & Excise men. ‘Bo-peep’ was an early 16th century term denoting a game of hiding and reappearing, more usually rendered today as ‘peep-bo’ or ‘peekaboo’; it had described the action of ‘looking out for’ since the 14th century. Certainly the location’s cliffs offered an uninterrupted view along the coastline between Hastings and Bexhill, and

particularly the beaches at Bulverhythe, which were a popular landing spot for contraband.

The ‘sheep’ are the smugglers and the ‘tails’ are the smuggled items, notably two gallon kegs of brandy smuggled from France, which would be dropped along the coast to avoid detection. The kegs would be tied together with ropes, then when ‘the coast was clear’ they would be raised from the sea and brought ashore by the smugglers, ‘wagging their tails behind them’.

When the railway arrived along the coast from Brighton in 1846, the original pub was demolished to make way for St. Leonards West Marina station. The landlord was compensated by the SER and in 1847 built a new establishment, just east of the new station, which today is a lively family- and dog-friendly pub. It was initially called the Railway Terminus Inn, but the name reverted to Bo-Peep when the tunnel was dug through the cliffs behind.

The Bo-Peep pub, Bulverhythe, West St. Leonards. One side of the inn sign shows the traditional nursery-rhyme image (left), while the other depicts smugglers rowing ashore (right). The hide-and-seek activities of the smugglers in the area resulted in a bloody battle with Excisemen in 1828.

The Great Exhibition of 1851 took place in Hyde Park, London, accommodated within the remarkable castiron and plate-glass structure that became known as the ‘Crystal Palace’. The name arose supposedly as a result of a remark by playwright Douglas Jerrold in Punch magazine in 1850, who described it as a ‘palace of very crystal’. It covered 990,000 square feet, was 1,851 feet long and 128 feet high, and within it were exhibited ‘the Works of Industry of All Nations’.

The building was famously designed by renowned gardener Joseph Paxton. Famous for his work for the Duke of Devonshire at Chatsworth, Paxton later became a director of the Midland Railway. He was in London for a meeting with MR Chairman John Ellis when he mentioned an idea he had for the hall’s design, and Ellis encouraged him to produce some plans.

CRYSTAL PALACE

A few days later, at a board meeting in Derby, he sketched out his preliminary design on a sheet of blotting paper (now preserved in the Victoria & Albert Museum), based on his Lily House at Chatsworth.

When the Exhibition closed after six months, two board members of the LBSCR proposed that the building be dismantled and moved to Penge Place, at the top of Sydenham Hill, and it reopened there in 1854.

To cater for the many visitors to the new ‘Crystal Palace’, two railway stations were opened. The first was provided by the West End of London & Crystal Palace Railway, operated by the LBSCR, in 1854. This was reached via the 746-yard Crystal Palace Tunnel, and had the suffix Low Level added in 1898. That was followed by Crystal Palace High Level, constructed by

the Crystal Palace & South London Junction Railway in 1865, with ‘High Level & Upper Norwood’ added to its name in 1898 by what was by then the LCDR (later the SECR). This was the terminus of a branch from Nunhead and was an impressive building, connected to the Palace by a subway.

Sadly, in November 1936 the Crystal Palace was destroyed by fire, after which the High Level station fell into disuse, and was finally shut in 1954. The Low Level station survives as just Crystal Palace (since 1955). Recently much redeveloped, the sixplatform station sees trains from London Bridge and London Victoria, and since 2010 has been the terminus of the East London Line of London Overground.

‘Southern Electric’ branding from the 1930s, photographed on 18th September 1954. Note that one needs to descend to the High Level station! Photo: Milepost 92½, Transport Treasury (MC10052C)

This area was named in honour of Prince George of Denmark, husband of Queen Anne (they married in 1683), who had a house on the east side of the hill, and hunted there.

Denmark Hill station, between Peckham Rye and East Brixton, was built in 1864-66 in the very decorative Italianate style. Unfortunately, a century later the building had become

DENMARK HILL

neglected and in 1980 was targeted by arsonists and the roof was destroyed. Happily it was saved from demolition, and the restored station included a pub, initially called the Phoenix and Firkin to commemorate the fire; it is now known simply as the Phoenix.

In 2011-13 the station underwent a further redesign, with a new ticket office, walkways and lifts. In 2021 a second entrance

opened on the north-eastern side, and that year the station was in the news as Europe’s first ‘carbon positive’ station, i.e. it produces more energy – via a new type of photovoltaic film on the roof – than it uses, the surplus being fed to the National Grid. The upgraded station was ceremonially reopened by local resident Sandi Toksvig.

Above: The decorative station building was restored after a fire in 1980, and now accommodates the Phoenix pub; in 1986 it was given a Civic Trust award.

The ticket office is now in Champion Park, on the right.

Photo: Marathon, Geograph

Right: A 1706 portrait of Queen Anne and Prince George of Denmark. Wikipedia Commons

Cricklewood-based 8F 2-8-0 No. 48410 heads what is presumably an inter-regional down freight eastwards through Denmark Hill station on 5th April 1955. The running-in board advertises that this is the station for King’s College Hospital, which moved to Denmark Hill from central London in 1909. Photo: R. C. Riley, Transport Treasury (RCR6002)

This has been an important meeting of roads south of the Thames since at least the 17th century, especially following the building of Westminster Bridge in 1751, Blackfriars Bridge in the 1760s, and improvements to London Bridge.

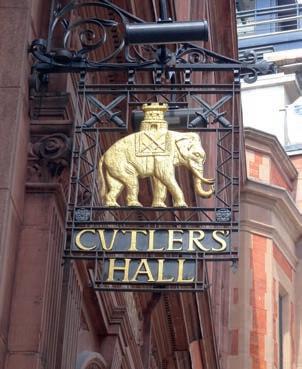

The original premises at ‘Elephant & Castle’ were that of a blacksmith and cutler, and it is suggested that the name derives from the crest of the Worshipful Company of Cutlers, which features an elephant with a castle on its back (the connection with cutlers being the former use of ivory for handles). Another explanation, now considered less likely, is that the name is a

ELEPHANT & CASTLE

corruption of ‘Infanta of Castile’, as there have been several associations between Spanish princesses and English royalty, one such being Maria Anna of Spain, unsuccessfully courted by King Charles I. In general, the image of an elephant with a castle on its back is fairly common in heraldry.

Whatever the origin, in about 1760 the smithy became a coaching inn, the earliest surviving record of the ‘Elephant & Castle’ in this context appearing in 1765. In time the name came to be applied to the district as a whole, in the absence of a distinctive geographical feature or saint’s name – another example already encountered is Bricklayers Arms. During the

Georgian and Victorian eras the area was swallowed up to became a teeming south London suburb.

The inn was rebuilt in 1816 and again in 1898, while the present pub dates from the rebuilding of the area in the 1960s after extensive damage during the Blitz.

The SECR’s Elephant & Castle station was opened in 1863. A station on the Northern Line followed in 1890, built by the City & South London Railway, and the Bakerloo Line station (originally the Baker Street & Waterloo Railway) was added in 1906; Elephant & Castle is the southern terminus of the line.

The arms of the Worshipful Company of Cutlers might provide a clue to the origin of the location’s name. Cutlers’ Hall is in Warwick Lane in the City of London. Photo: WA

SECR Class E1 4-4-0 No. 31506 passes through Elephant & Castle on 21st March 1959. The train is the RCTS ‘London and North Kent Rail Tour’, which used no fewer than five locomotives to take the train north from Liverpool Street to Finsbury Park, south of the river via Blackfriars to Gravesend and Hither Green, then back via New Cross to Liverpool Street. A diesel was used for the first time on an RCTS special, when No. D8401 (then less than a year old) undertook the last leg back to Liverpool Street. The ‘E1’ took over the train at Blackfriars.

Photo: R. C. Riley, Transport Treasury (RCR13059)

The bustling road junction and Elephant & Castle pub are seen in around 1900. To the left of the pub is Walworth Road, and to the right Newington Butts.

Photo: WA Collection

Martello Tunnel (Folkestone)

This location owes its name to South Coast fortifications in much the same way as Fort Brockhurst and Fort Gomer (see page 52).

A line of 74 Martello towers – small defensive forts – was built along the Sussex and Kent coasts in 1805-06 in response to a threat of invasion by France during the Napoleonic wars. Their design was inspired by a similar circular tower at Cape Mortella, Corsica, which gives the towers their common name; the British Navy had attacked that tower in 1794, and it had proved difficult to capture. A total of 103 towers appeared not only along the Kent and Sussex coasts, but also in Suffolk and Essex, and protected beaches that were potential invasion points; they were located so that adjacent towers could provide interlocking fields of fire. The towers eventually became obsolete during the latter part of the 19th century, although some found further use during the Second World War.

Tower No. 1, located on cliffs 200 feet above East Wear Bay, about a mile east of Folkestone, is one of only 26 of the original 74 South Coast towers to survive (in total 47 still exist).

Although Grade II listed, it has been altered over the years, and is now in domestic occupation. Nevertheless, its distinctive form and structure remain intact. It is brick-built with its sides sloping inwards towards the top; inside it is circular, but outside it is elliptical, the thicker walls facing the sea; this makes the towers resistant to cannon fire. It now has additional windows and a door at ground level, although originally it would have been entered at first-floor level via a retractable ladder. An extra floor has been added to the top.

The South Eastern Railway arrived at Folkestone from the west in 1843. The builders then faced a headland of greensand and gault, a stiff blue clay, through which a tunnel, originally 636 yards long and now about 530 yards, was bored with

Right: The original ‘Martello Tower’.

This is what is left of the Torra di Martella, Corsica, dating from the 1560s. The attacking British were impressed by the tower’s effectiveness, so copied the design for the English versions, although they misspelled the name as ‘Martello’. When the British withdrew from Corsica in 1796 they blew up the tower.

Photo: M. Colle, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Left: No. 1 Tower is seen here as converted into an attractive and most unusual dwelling, with its additional upper storey. Note the ‘No. 1’ plaque above the original first-floor entrance door. Photo: WA

difficulty; opening the following year, it took its name from Martello Tower No 1, which stood just seaward of its centreline, about halfway along. East of the tunnel is the treacherous and hummocky Folkestone Warren, through which a long and very deep cutting was made. Then followed three chalk headlands, Abbott’s Cliff, Round Down Cliff and Shakespeare Cliff (qv).

Land movement of the chalk, usually caused by heavy rain, was an ongoing problem for the line’s engineers, making this stretch one of the most expensive parts of the railway network to maintain. In 1877 100 yards of the tunnel partially collapsed, killing two people and closing the line for three months. In 1896 the western portal cracked, and was rebuilt further west as a precaution. In 1915 a major landslip in Folkestone Warren, east of the tunnel, closed the line for four years; another, albeit shorter, closure occurred in 1939.

Fifteen-month-old ‘Battle of Britain’ Class 4-6-2 No. 34071 601 Squadron heads east towards Dover in July 1949 while working a Victoria-Dover Marine boat train via Maidstone East. It has just left Martello Tunnel, just east of Folkestone Junction station. The top of Martello Tower No. 1 can just be seen on the left horizon. The depth of the cutting through the treacherous chalk is clear to see. Photo: Les Hanson, David Hanson Archive, Rail-Online