As my grandmother would tuck us in, she would perform a little ritual. On those lucky nights when we had sleepovers at her small, whitewashed house in Burton, nestled into feather beds with air-freshened sheets and quilts cozied under our chins, my sister, my cousin, and I would wait for her to complete the last rite of the day. While murmuring in Slovene, she would bless us in the same way that her own mother had done to her and her siblings. It was a meaningful act; it was my grandmother’s way of passing on part of our family’s immigrant culture, a thing that defined us, a thing that created a common memory and a bond. I have many cousins across the country that hail from this same line in my family tree; many if not most of them aren’t familiar with this very old prayer. For whatever reason, it wasn’t something that was passed on—forgotten in only one generation. Recently, two of the Wisconsin clan created a Tomažin Family Facebook page, where we’ve begun sharing stories and photos—a wonderful reconnection— and I’ve had the opportunity to relate Grandma’s nightly custom.

This disappearance of common history isn’t relegated to just families. It happens in communities, large and small, if stories are not repeated, and if it isn’t obvious why they are important to us. The history becomes lost knowledge. Memories can be short, humans move on; this is how entire civilizations have curiously been buried under time, dust, and earth. "How could that have happened?" we wonder. Contemporary communication has changed drastically, as well, accelerating the speed at which we digest our information, which is highly curated—narrowed—to suit our tastes. Along the way, we are losing our connections. Where ancient man had the tribal bard, contemporary man has the written word. But…our once main local “watering holes” of information—our strongly identifiable local newspapers—have been replaced with an endless variety of websites, blogs, social media pages, YouTube channels, etc. There also seems to be a lack of emphasis on our local history being taught in schools, where the imaginations of the young are lit, where the early bond and pride in our community is tied. The institutions where “oldtimers” verse the “youngsters” seem to be fading. We at the GCHS are trying to do a bit of course correcting.

We’re all very excited to get this second edition of The Historian out. After the premiere issue, we had an amazing response from thirsty readers. Our writing staff has, again, provided terrific content, and you can hear their enthusiasm through their words. Thoughtprovoking, informative, touching, colorful stories—you will find all of that in the articles found between this issue’s covers.

Unless our stories are being told, they very easily can be swept into the Dustbin of Forgotten Things. By picking up this magazine, you—our reader—have become part of something bigger. You are the bard, you are the old-timer. Spread the word, pass on our common local culture. It is a meaningful act.

Tracy Leigh Fisher Editor-in-Chief

Thought to be the first hardware store in Flint, opened by George W. Hubbard and Charles H. Wood in 1863. Man in door is Louis P. Church. Located in the 400 block of Saginaw Street.

Photo courtesy the Sloan Museum Archives

When the airline industry needed a reliable plane for domestic travel, they turned to him.

When Adolph Hitler’s Luftwaffe was destroying London, they turned to him.

When President Dwight D. Eisenhower needed an answer to the growing threat posed by an increasingly aggressive Soviet Union, they turned to him.

When America needed technology that could catapult and safeguard the nation for the next half-century against increasingly asymmetrical danger, they turned to him. He answered the bell each and every time.

His legacy will endure as long as humans take to the skies

By Gary L. Fisher

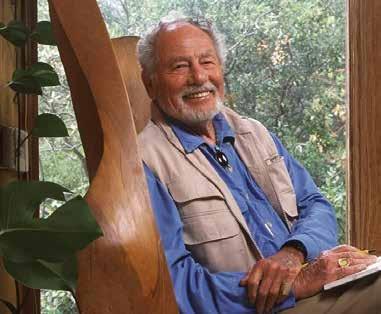

‘He’is Clarence ‘Kelly’ Johnson, considered one of the most important people in the entire human history of aviation, second only to the Wright Brothers. Naturally, he hails from the cradle of innovation, Flint, Michigan. Born in Ipsheming, his family moved to Flint when Kelly had just finished elementary school, living first at 355 Stewart Avenue, and then East Moore Street.

Yet, who he is, and how he achieved this lofty status has remained a secret story in Flint, a city that has the unique ability to forget its heroes. Johnson shouldn’t be one of them. In truth, Flint’s proclivity to easily and quickly lose track of the people who hail from her neighborhoods, is only part of the reason his story is hidden. The other part is the nature of the work he would come to be engaged in. Much of it was secret and hidden by design.

It was in Flint where he was bequeathed the name he would be known by for the rest of his life. ‘Kelly’ was a nickname. When his family moved to Flint he was greeted in a style that wouldn’t change much over the years in Flint Town. He was tested. As the new kid, he had to prove himself.

Tough Flint kids allowed no quarter. To make it worse, Kelly was a book worm. In truth, he was a genius. An outsider from the Frozen North, he was entering a blast furnace of

the surging industrial powerhouse, filled with multiple ethnicities, races, and hard-bitten street-smart sharks.

The name ‘Clarence' became a source of derision—and constant bullying and teasing. Clarence became ‘Connie’ and the torture continued unabated until one day he responded. Finally, in the lunch room, he fought back against a tormentor by breaking his leg. From that day forward, the Flint boys renamed him “Kelly” after a popular song of the day, Has Anybody Seen Kelly?

“Has anybody here seen Kelly K-E- Double - L- Y…. Kelly from the Emerald Isle…"

With the notion that the Irish were hard fighters, and Kelly was a tough name, the kids sang the song to him and his reputation was forever changed from nerd to roughneck. Indeed, it was a far cry from ‘Connie” and it stuck…despite that fact that he was Swedish.

Johnson credits the move to Flint with far more than a nickname. Indeed, Flint provided the impetus and support that accelerated and amplified his quest for success and excellence. “Flint had an excellent public school system, and an even bigger library than Ipsheming, and I became a regular visitor.”

By the time he started at Flint Central High School he had memorized the path to the Clifford Street Carnegie Library downtown. Between that and the Flint Central library, he immersed himself in to all of the available aviation books and knowledge he could get his hands on.

By the time he was a senior at Central, he was firmly ensconced in the aviation culture. During his sophomore year the Flint Kiwanis Club sponsored a model airplane building contest, and Johnson landed second place, winning the mighty sum of $25.

Even though he had never actually flown in an airplane, he knew that aviation was his destiny. “I knew from the time I moved to Flint that I wanted to build and design airplanes”, he said. On his senior picture in the Central yearbook he indicated his interests as “Mostly aviation”.

He thought he might take some time off after graduation to travel and see the world but one of his teachers at Central, Bertha Baker, intervened and that would alter history. She counseled him on how going to Flint Junior College would be a smarter move, helping him enroll. Kelly later said this completely changed the trajectory of his life.

That summer he headed out to Flint Bishop Airport and paid $5 for a 3-minute flight—his first—and it solidified his fate and future. Later that summer, he went back to sign up for a flight training course. The encounter would be the

second most important one of his life at that point. “I was prepared to hand over my entire fortune at the time of $300 for 10 hours of flight instruction”, Kelly remembered. He was meeting with the instructor, the same man who had taken him up for his maiden voyage, Jim White. Much like Bertha Baker, White asked lots of questions about what Kelly’s aspirations were. “He spent a considerable amount of time really getting to know me”, Kelly recalled. Instead of selling him the flight package, he counseled him to carry on with his formal education at the University of Michigan.

According to Kelly, White said “You have good grades. You will go a lot farther if you go on to University. I won’t take your money. You don’t want to end up an airport bum like me.” Kelly said, “He was a big man.” And hardly an airport bum. This advice would be the next plot point to catapult Kelly in to the stratosphere.

Kelly would go on to the University of Michigan where his talents would lead him to a fledgling aviation firm in California called Lockheed. The firm was forward thinking and valued Kelly’s work in design, including his five Indianapolis 500 racing qualifiers while still in school.

To say that Kelly Johnson’s career at Lockheed was ‘legendary’ would understate the fact by magnitudes of order. When Johnson started work there he promptly informed Chief Engineer Hale Hubbard that Lockheed’s premier product, the Electra, was “dangerously unstable.” To prove it, he produced research from the Michigan wind tunnel that confirmed his assertion, and included new designs that fixed the problems completely. The iconic legend of Kelly Johnson was born quickly as the Electra became an early solution to world commercial airliner progress.

During these heady early years he worked closely with a variety of iconic personalities. This included work with billionaire mogul Howard Hughes. Kelly actually grounded Hughes because of his out of control and dangerous piloting of a test plane. Hughes was not pleased, but such was Kelly’s power that Lockheed stood behind him. Charles Lindbergh was a regular visitor at Lockheed and Kelly met with him to discuss aviation design frequently.

Later, he would work closely with Amelia Earhart. “The two of us, she as pilot, and I as flight engineer, would fly her Electra with different weights, different balance conditions, different engine power settings, different altitudes.” When Earhart decided to fly around the world using the Electra, Kelly worked with her to determine fuel loads, operational advice, and take-off and landing procedures.

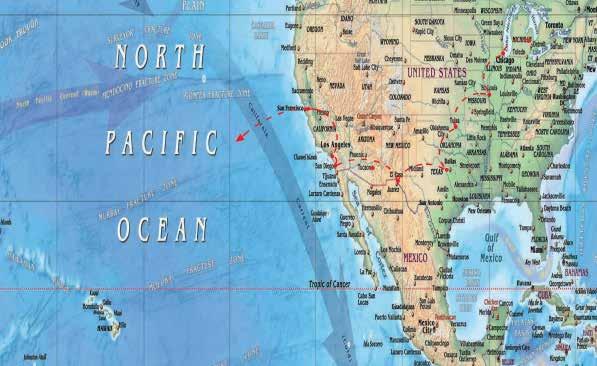

Earhart’s ill-fated journey included a tricky landing at Howland Island, a tiny island barely rising above sea level. Severely overcast skies prevented her and her navigator, Fred Noonan, from seeing checkpoints from the air, and as they flew around trying to gauge a location their fuel dwindled. No one knew this better than Kelly Johnson. “They had been in the air for 23 hours and, so help me, that’s all the time they had fuel for.” No one would have known that better than him.

The warning rumbles and drum beats of war were pounding loudly when England’s Neville Chamberlain took a Lockheed Electra to meet with Germany’s Führer Adolph Hitler. After he returned to infamously proclaim “peace in our time”, war commenced. With it another important and ultimately secret and deadly serious chapter would begin for Flintstone Kelly Johnson, as the world would turn to him.

He was already working with the British on the Hudson plane, used at the Battle of Dunkirk, when the US government came looking for an answer to Hitler’s Luftwaffe. Kelly produced the P38 fighter jet, a workhorse plane that set the stage for his new role as Chief of Secret Projects at Lockheed.

After America’s entry in to WW2, Kelly would work closely with the American military, including Jimmy Doolittle, who engineered the bombing of Tokyo, as a first response to the sneak attack at Pearl Harbor.

As the war dragged on, the Nazi’s began flying jet-powered aircraft that were unmatched in the skies. When the Messerschmitt Me-262s joined the Luftwaffe arsenal, the game was changed forever, and so was the urgency to respond.

On June 8, 1943 General H. H. ‘Hap’ Arnold approved a contract for an American jet fighter. They gave Kelly only 180 days to do it. This led Kelly to invent a unique work environment and think tank at Lockheed that came to be known as the ‘Skunk Works’. They produced the first American fighter to exceed 500 mph. Ultimately named the Shooting Star, it became America’s first tactical jet fighter.

During the Cold War, the Skunk Works continued to produce one breathtaking innovation after another. In 1959, Kelly and his team produced the F104 Starfighter, later the SuperStarfighter. It became the first plane to fly twice the speed of sound. It won the prestigious Collier Trophy for the “Greatest Achievement in Aviation” that same year.

By 1962, tensions with the Soviet Union had redlined. Nuclear war seemed like a very real possibility, if not a likelihood. Kelly and the Skunk Works team had developed a plane for such times called the U2. A U2 took the pictures of Soviet missiles in Cuba that led to a near nuclear showdown in 1962's ‘Missiles of October’. A Russian missile would shoot one down and pilot Francis Gary Powers would

Clarence "Kelly" Johnson, CONTINUED on page 46

By Colleen Marquis

The first person struck by an automobile in Flint was Order of the Eagle member A. F. Coddington of 310 2nd Street at 6:30 AM in July 1908. He stepped off a streetcar before being struck by the vehicle and run clean over. He suffered injuries to his ribs and fractured an ankle. This is all according to the Flint Journal which, apparently, is the best and only record we have.

When I began looking into traffic laws and history in Flint, I thought it was going to be easy! Surely, this would be something so well known I’d just need to cite a long-forgotten article or paper somewhere, add some academic language, and clean my hands of the whole thing. When I dug a little though it wasn’t the traffic history that grabbed me, it was the lack of City history in general.

I started with the Flint Police Department hoping for a historicallyminded captain to have done the work for me but no, records were lost in a fire in the 1930s. From there, I went to City Hall to have a look around. Maybe I’d be able to find something, though I was told that was very unlikely as the City of Flint has never had a records manager. Never employed an archivist. Never wrote up a records retention schedule.

The majority of the city’s records sit under the small domed amphitheater in the back of the City Hall building. Now in my line of work as an archivist, I have gone into some questionable, moldfilled, non-OSHA-approved places but those were generally private spaces and businesses or abandoned buildings--not an operational City Hall. Aside from the obvious preservation issues of a leaky old basement, the records had no organization, no assigned location, no description, and were completely overwhelming. I was on a wild goose chase.

I put the problem of the City’s collection in my back pocket, picking

up some wonderful historic photos along the way, and started searching the Flint Journal with all kinds of early terminology for motor vehicles (from the common horseless carriage to the more exotic sounding autometon and motorig) to try to scare something up.

There were a couple of other notable incidents which are worthy of mention. Oddly, the first Flintstone to be hit by a motor vehicle happened almost exactly one year prior to Coddington’s brush with death, but occurred in Detroit. If I am being honest, I was looking for evidence of early vehicle pioneers getting into bang ups, and I was not disappointed. Ralph Dort, physician and son of J. Dallas Dort (one if the founders of General Motors, Chevrolet, and Dort Motors) hit a bicyclist in June, 1909 with his car at the corner of MLK (then Detroit St.) and Saginaw. He clobbered William Gillipsie of Mundy Township so well that the man was unconscious and suffered a broken collarbone along with bruises and wounds to his face and hands. Though Ralph claimed he was driving the vehicle at a “slow rate” he said the accident was unavoidable. Gillespie, for his part, couldn’t remember what had happened at all, most likely suffering from a concussion

Finally, I came across A.F. Coddington, who went on to recover from his injuries. Apparently not scared off from the idea of motor

vehicles, he was one of three commissioners who evaluated homes, buildings, and land in downtown Flint in order to complete a massive paving and curb project on Church Street from Court to Kearsley in 1912.

But I can’t get that damp, dirty basement out of my mind. It’s small projects and simple questions that unearth the massive problems that exist in the record-keeping of organizations. The history of the City of Flint is rotting and it has nothing to do with apathy or ignorance, but simply with survival. Dusty old records tend to stay on the back burner when there is a crisis and Flint has been in crisis mode for so very long. Like I tell people who come to Flint and criticize the crumbling Nash House or other historic homes in disrepair, people are more important than piles of brick and mortar, no matter who owned it. People are more important than the photos, maps, and records hiding under City Hall. As Flint emerges from the Water Crisis, and now the Pandemic, our thoughts can finally turn to preserve these neglected gems. Hopefully soon.

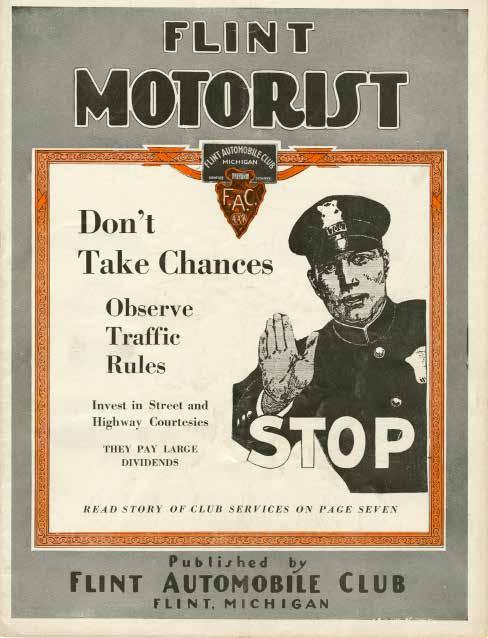

Above: Table of Contents of the Flint Automobile Club's "Flint Motorist" guide

Top right and center: One of the neglected places our Intrepid Archivist trekked, hunting for records

Bottom right: The article from the Flint Journal that Colleen located covering the first auto accident in Flint

Photos and Images courtesy of University of Michigan Flint Archives

By Bob Campell

For seventeen years, current residents, former residents, and descendants of residents of Flint’s Elm Park-Lapeer Park neighborhood have gathered every August at Brennan Park for the Southside Reunion. The park is adjacent to Stewart Elementary School, which opened in 1955 to educate the Black families that would flood it as Flint rode the wave of a surging automobile industry and closed in 2009 after years of falling enrollment and a receding population citywide.

I grew up in the old neighborhood, so you can find me there. These get-togethers are like a multigenerational tailgate, where fond memories and old childhood and teenage rivalries alike have aged well. Even those who have had a tougher row to hoe since the days when we played in the fields and ran those streets—men and women

who may have done some time, fallen victim to substance abuse, or some other misfortune—are embraced for the history that we cherish, and for having made it through to the other side.

Over the years, the annual tailgaters have grown to include other current and former city residents, most notably people from the neighborhoods east of Elm Park-Lapeer Park, across the major northsouth thoroughfare of Dort Highway. Over in the Evergreen Valley and the Evergreen Estates—or “the Valley” and “the Estates”—where the houses of our sometimes-hated rivals were newer and the median household income higher. They also attended a different elementary school (Scott), and later different junior high and high schools, when the district was rearranged in 1976 as part of a federal desegregation order, and to address shrinking enrollment.

The re-drawn school boundaries would keep our neighborhoods separate past grade school, but we remained loyal Southsiders. And, whether we still resided in the Flint area or merely back in town to visit (many of us now living out-of-state), we were home again at the Southside Reunion.

“The Southside” is a holdover from the days when the city’s Black residents defined their identities based on geography. Here or there? Northside or Southside? You were either one of us or one of them. The division was handed down by great-grandparents, grandparents, and parents who lived in the neighborhoods where the city’s first Black dwellers resided—on the Northside, bordering the sprawling Buick Motor Division complex, the St. John Street area, in particular; and on the Southside, mainly in the Floral Park area. (The St. John Street and Floral Park areas were razed in the early 1970s to make way for I-475 and the I-475/I-69 interchange, respectively.) Southsiders were naïve and stuck-up; Northsiders the streetwise rogues. Or so it went.

"...most of us were the offspring of a great mass of people—some six million Blacks who, between 1916 and 1970 decided to leave the rural South for better lives..."

In truth, the connections were richer, deeper, and far more complex. For most of us were the offspring of a great mass of people—some six million Blacks who, between 1916 and 1970, decided to leave the rural South for better lives in the West, Midwest, and urban Northeast, that historic movement of American citizens known as the Great Migration.

if there were a physical line of demarcation for the division, it was the Flint River, whose reputation of late is tied unjustly to the Flint water emergency. The waterway meanders seventy-eight miles south from its headwaters, northeast of Flint, and through the city’s downtown before eventually turning north again to connect with

the Shiawassee River in neighboring Saginaw County. It formed the eastern boundary of the long-vanished St. John Street neighborhood. This multicultural community—on streets named Michigan Avenue, St. John, and Easy (yes, there was an Easy Street)—was home to an array of transplants: European immigrants from Hungary, Poland, Italy and Croatia, as well as Black migrants from the cotton and tobacco fields, the pine forests and orange groves “down South.”

That neighborhood, St. John, is where my maternal grandparents— Ernest (b. 1901) and Rosa (b. 1903) Holliday—made their home. Unfortunately, I never had the chance to meet them; both died before I was born. But here’s what I know:

Sometime in the early 1920s, the Hollidays left tiny Okolona in the heart of Mississippi’s cotton region for Dee-troit, as the southern old-timers pronounced it. They likely settled in Paradise Valley, also known as Black Bottom, joining thousands of other Blacks who had flocked to Detroit, where the Black population had exploded by more than six-hundred percent between 1910 and 1920. My mother, Rose, was born there in 1925.

By 1927, Ernest, Rosa, and their two daughters were residents of Flint, living on St. John Street in the vicinity of the Ukrainian Club, the Croatian-Slovenia Club, Dom Polski Hall, Eastern Orthodox churches, and Black Baptist and African Methodist Episcopal churches. St. John Street became the main thoroughfare of a thriving Black community, not unlike Paradise Valley in Detroit. My grandfather and his brothers were barbers, and frequently serviced Black entertainers of the day who performed in Flint as part of the “Chitlin’ Circuit.” One of the venues was the Golden Leaf Club in Floral Park, which still operates today—one of the very few remnants of that long-vanished neighborhood.

Meanwhile, Grandma Holliday was a homemaker and domestic, and later worked in armaments production, along with mama, at AC Spark Plug, on Industrial Avenue, during World War II. Rosa and Rose—two true-to-life Rosie the Riveters.

Sometime before the Hollidays’ arrival, my paternal grandfather, Hardwick Campbell (b. 1898), came to Flint in search of work. He hired into Buick and was assigned to the foundry—the only area where Blacks could work for the carmaker. Once settled, he sent for my grandmother, Eula (b. 1904), who, along with their two-year-old son, Clarence, and infant daughter, Essie, joined Grandpa in 1923. They lived on Grant Street, just north of the Buick complex. It, too, was a multi-ethnic neighborhood “across the tracks”—the rail line used to ship in raw materials and ship out new Buicks from the plant—and a step up from the St. John Street area.

They had come from the pitch-tree forested area near Montezuma, Georgia, on the eastern banks of a different Flint River, which snakes 344 miles from a region south of Atlanta to the marshlands of the gulf coastal plain in the southwestern corner of the state. Other family members would leave Georgia, too, for destinations in Ohio (namely Steubenville and Akron) and Weirton, West Virginia, to labor in the steel mills.

Grandpa Campbell would spend twenty-five years in the Buick foundry. Meanwhile, Grandma took in laundry for additional income during the Great Depression. Clarence, my father, would deliver the finished laundry to customers. Later, the robust laundry service prompted Grandpa to buy daddy a 1925 Chevrolet to use for pickup and delivery.

winding country road on the way to Montezuma. He had decided on a whim, to take a brief detour off southbound I-75 for a quick drive through of the place of his birth. (If I had to guess, I would say that route taken into town was GA-224.)

Sherry was no country girl. None of us were, even though my parents had a summer cottage on a small lake in Michigan’s thumb region. We are city folk, by and large, born and bred like our mother, a Detroit native, in urban spaces. Moreover, the gulf between my Flint upbringing and my southern roots is as vast as the Atlantic Ocean, as disconnected as the two Flint Rivers that flow through my family’s history.

Around 1940, Grandpa bought a Mobil gas station on Pasadena and Industrial avenues, across the street from Buick. The signage at Campbell’s Service Station featured the iconic Mobil Pegasus. Buick eventually needed more space for parking, so Campbell’s Service Station relocated to Pierson Road and Selby Street—the location I remember—where it remained until the mid1970s, when clearing began for the coming of I-475. That’s when Grandpa retired.

Back in December 1942, the year my parents got married, and not long after Grandpa opened his business, daddy was inducted into the U.S. Army. He had been working as a janitor at AC Spark Plug on Industrial Avenue when the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. He would go onto serve more than three years in the segregated 92nd Infantry Division and brave combat in Italy, earning both a Combat Infantryman Badge and Bronze Star. After the war, my parents resumed their lives in Flint. Daddy went back to AC while mama, who left the factory job to make room for the returning veterans, was an elevator operator at the Citizens Bank headquarters downtown. By 1948, they began building a ranch-style brick house off a dirt road in a lightly populated part of town, a little southeast of Floral Park, and down the street from the future site of Stewart School.

Ihavenever been to Okolona, Mississippi. I have never visited Montezuma, Georgia, although I do recall driving through there late one night with the family on the way to Delray Beach, Florida. I was asleep at the time but was awakened during a refueling stop by an older sister’s sobs. “I’m tired of seeing my life pass before my eyes,” Sherry cried, clearly unnerved by daddy’s speeding through the dark

In that regard, I’m not alone. There is a silent lament about the historical detachment to our family histories that is more common among Black people than other groups, I think, though it’s rarely discussed. About a year ago or so, my wife casually noted that the knowledge of her family tree extends only to her maternal grandparents, for the most part. I have heard similar comments from friends and relatives. As for myself, I know only the names of some of my paternal ancestors extending back to a slave sold and bought in Virginia; even less is known about my mother’s side. (My sister, Carole, has begun researching our family tree and is slowly uncovering some of our roots buried in Georgia and Mississippi.)

That separation, that break in the lineage of our families is part of the appeal of gatherings like the Southside Reunion. Beecher, a small water district that shares a common border with the northern Flint city limit, also has a large tailgate gathering each summer. That community, which was nearly wiped out by a devastating tornado in 1953, used to be all-white. Today, it’s virtually all-Black and remains a deep source of pride for everyone I know who grew up there, including my wife. They call it “Buc-town”—shorthand for Buccaneers, the high school mascot. (It’s also worth noting that, in some cases, the descendants of those who decades ago fled Jim Crow and sought economic opportunity elsewhere are returning to their southern homelands.)

I feel that separation deeply in my own life. To my knowledge, I do not have any immediate family remaining in Okolona and Montezuma, no bridge to that ancestry. What I do have is a tradition of Black reunions that connect me to my community and family and fulfills that longing for meaningful attachment. In fact, my siblings and I, and our offspring, held our first family reunion this past June. Our parents are now deceased. With the 2021 Campbell family reunion in the genealogy record books, I now look forward to stopping by the old neighborhood again for a couple of beers, laughs and updates at the 18th Annual Southside Reunion on August 21, postponed from last year during the height of the pandemic.

(This essay went into pre-publication prior to the 18th Annual Southside Reunion. An earlier version of this essay was published in Belt Magazine in December 2019.)

We’re big fans of people who look out for people.

Thank you to the Genesee County Historical Society for all you do to preserve and remind us of our great past, and to educate and inspire us as we move toward a greater future. Hard work doesn’t always get the recognition it deserves, so when it makes a community better, we take notice. We appreciate all your efforts, and keep making us stronger

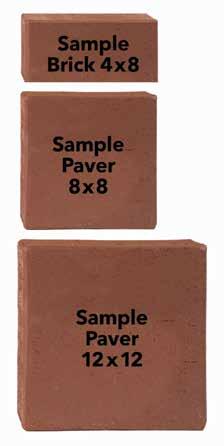

played an important part of everyday life for centuries. Perhaps the first sign ordinance appeared in England in 1389 when King Richard II ordered every tavern to display a sign outside their premises. But it is in American history, within the last 100 years, that signs have advanced more than in the previous 5000 years. We rely on signs everyday to direct us, inform us and persuade us. So, we decided to look at signs that have been part of our daily lives. Signs that most County residents would recognize; the historic iconic signs of Genesee County that we have come to know and would reminisce about if they were gone.

by Ron Campbell and Jackie Hoist

Above: Sign today at Vic Canever Chevrolet dealership in Fenton, Michigan

Left: The Battle of the Running Bulls, January 11, 1937

monumental ‘Chevrolet’ neon sign once topped the overpass in ‘Happy Valley’ also known as ‘Chevy in the Hole’, tying plants on either side of Chevrolet Avenue together. It was this sign that stood sentry as the “Battle of the Running Bulls” played out in the street below during the 1936-37 Sit-Down-Strike. There are a few stories out there about the design of the Chevrolet logo. Lawrence R. Gustin, GCHS member, Flint Journal writer, and author of the seminal book on William C. "Billy" Durant, Billy Durant: Creator of General Motors, met several times with Catherine Durant, Billy’s wife. She once told Larry that she and Billy were on a trip to a spa in West Virginia when he saw an ad for a local coal company called “Coalettes’. The ad inspired Billy to sketch out a similar shaped backdrop for his ‘CHEVROLET’ logo. Another story cites Durant's daughter, Margery, who holds yet another theory. In her 1929 book, My Father, she says Durant would often sketch ideas and designs at the dinner table. She says: "I think it was between the soup and the fried chicken one night that he sketched out the design’. Even yet another theory suggests Durant was inspired by the wallpaper of a Parisian hotel he was staying in. Whatever the inspiration was, it made for an iconic image that impacted the community and the world; it’s been placed on over 215 million cars since it was first seen in 1913. A visit with Dan Crannie of Crannie signs revealed that when the fateful day came to remove the ‘Chevrolet’ sign it was lifted from the overpass by helicopter, but the sign was heavier than anticipated and the helicopter started to lose control as it hovered over the plant. In an effort to avoid crashing, the helicopter had to drop the sign, and it smashed through the roof of the plant, shutting down operations for hours. Today the iconic historic sign can be seen at the Vic Canever dealership in Fenton, where is still glows with its colorful neon and ‘slanted bow-tie’ design. GCHS is grateful that Vic Canever recognized the importance of this historic sign and has preserved it for the public to enjoy.

by Harriet Lay

County history is most notable for the advent of the automobile, but there are dozens of other offshoot industries that are worth exploring. One such short lived, unique and hugely successful business was the Flint Faience and Tile Company. Only in business from 1921-1933, it produced tens of thousands of beautiful artisan tiles and ceramic pieces that are coveted by collectors everywhere. These decorative and beautiful tiles can be found in automobile showrooms, hotel lobbies, store entrances, swimming pools, fountains, and private homes all over the country, to name just a few of their numerous uses. Many are very colorful and depict dozens of different images and patterns. Popular themes include animals, botanicals, sea life, fruit, holiday themes, religion and nursery rhymes. Others have beautiful geometric designs and put together, create exquisite patterns and pictures. Still more products include vases, lamps, serving dishes and ashtrays.

The term “faience” is derived from the town of Faenza, Italy and was used to refer to tinglazed earthenware. In the 1920s, the term faience was popularly used to describe glazed tiles that “looked” handmade and rustic. In fact, many of these tiles were created in a spark plug factory in Flint, Michigan.

It was 1921, and there were periods during the production of ceramic spark plugs that the kilns remained empty. The many ceramic experts, research engineers and technicians began making decorative tiles to fill that void. The Champion Ignition Company hired Ralph E. Stoneburger, in 1918, to supervise the kiln and sagger (a ceramic container used to protect the product being fired from open flame, gases, smoke and debris) department. His resumé was rich in tile and pottery experience and he became the first general foreman of Flint Faience and Tile Company in 1921. In 1925, a Belgian ceramic artist named Carl Bergman was then hired as first head designer. In 1928, the original site of the company on Harriet Street in Flint became insufficient to handle the growing demand and a new factory was built on Davison Road and Dort Hwy. Within a year, the company outgrew that site adding new building space, kilns and loading docks. During its most successful years, it had sales offices all over the United States, including New York City, Detroit, Chicago and Boston to name a few.

During this time, The Champion Ignition Company changed its name to AC Spark Plug, using Albert Champion’s initials because of confusion with a spark plug company in Toledo, Ohio named Champion Spark Plug Co. Albert Champion died in 1927; two

years later General Motors acquired AC Spark Plug stock from the Champion estate, adding AC Spark Plug as a new division of General Motors. Harlow H. Curtice became General Manager and under his leadership, in 1933, it was decided that an automobile company should not be in the tile business. It is also thought that as the demand for automobiles grew, the need for kiln space grew, limiting time and resources for tile-making.

Though Flint Faience and Tile Company was only in business for 12 years, it’s impact on design and architecture in the 1920s-30s cannot be disputed. The Company took pride in their ability to cater to their customer and to design and implement whatever the customer envisioned. Ken Galvas writes in his book Flint Faience Tiles A-Z, “Flint wanted to bring your vision to life.” If you have visited Halo Burger in downtown Flint, you have seen Flint Faience tiles. They include the decorative blue and green tiles installed on the building’s exterior and the interior tile floor. If you have visited St. Paul’s Episcopal Church on Saginaw St., you will have seen Flint Faience tiles on the chancel and on the floors. If you have visited St. Matthew’s Catholic Church of Flint, you may have noticed the beautifully decorated alter, all done in Flint Faience tile. You may live in or have visited a home built in the 1920s in the city and chances are that the foyer or the bathroom could very well be Flint Faience tile. Many of us remember the old I.M.A. (Industrial Mutual Association). Built in 1929, a series of athletic themed tiles were created for its interior. When it was razed in 1997, some of those tiles were salvaged and are now in the Sloan Museum collection.

In the early spring of 2014, the Genesee County Historical Society had the opportunity to purchase 19 Flint Faience vases from the collection of author Ken Galvas. Most are small, simple and functional, but many more were larger and could be made into lamps. The GCHS collection also includes two change dishes and a bronze door sign on loan from Tim and Angie Buda. The bronze sign (pictured) could have been used by dealers or on the office doors at the manufacturing plant. It is very rare and shows two arrowheads, the company logo. The Flint arrowhead was announced as the company trademark in 1929 and was stamped on tiles, stationery, signage, and promotional products.

The display also showcases five tiles on loan from Jim and Harriet Lay, depicting some of the amazing, diverse, and beautiful motifs. Flight into Egypt, designed by Howard B. Burton, is considered one of his premier works. A smaller tile depicting a starry night

From the collections of Harriet and Jim Lay; Tim and Angie Buda; The Genesee County

with Joseph walking next to Mary and Jesus seated on a donkey, is surrounded by 24 smaller border tiles. An architect by profession, Burton was the Art Director for the company and is credited with designing Flint Faience Tile murals and Art Deco designs in numerous commercial buildings built in the 1920s. Though we don’t know the titles of the other four tiles, they represent different themes and artistic approaches to tile-making. The clown tile, identical to the

one photographed in Ken Galvas’ book, was not a popular theme but was most probably placed with other similar subject matter in school classrooms or on nursery walls. The clown and ship tiles (pictured) are modeled in relief as opposed to Flight into Egypt which has the design carved into the clay. These pieces as well as the rest of the GCHS collection can be seen at the Durant Dort Office Building at 316 Water St. in Flint.

and Preservation

by Gary L. Fisher

Igot the call to head over to my alma mater Flint Central from a friend who saw the fire trucks heading there. Sure enough, when I arrived it was on fire. Luckily, the Flint Fire Department isn’t too far away and they were able to extinguish it. Before this a landscaper doing some work at my house had volunteered that he could get my personal records from the school if I wanted them. Apparently the were turned over and strewn around the floor on one of the abandoned offices. I could hardly believe it until he showed me pictures he had acquired.

The State Championship banners still hang on the wall. The trophies and awards, photos and history have been stolen, sold, or given away. Even now I am offered ‘memorabilia’ from the school that somehow wound up in the hands of former school employees and others. Despite years of trying, no one can say (or is willing to admit) where the valuable trophies and evidence of the long and storied history of the school is. It’s hard to wrap your head around the malfeasance.

Even now with offers of financial and manpower assistance in protecting, salvaging, or even saving what is left are ignored or denied. Smoke clouds of psychobabble surround the conversation,

and in the end nothing is ever done. The latest communication from the Flint School Board announces its intent to demolish the building. That’s if it doesn’t collapse or burn down first. It’s an ever-changing and chaotic story, and there might be a new one in play by the time you read this. To call what has happened to Flint Central High School shameful would be to understate the fact by magnitudes of order. It’s difficult to imagine such a disregard for a building and architecture that holds such history and import.

The building has been part of the community for nearly 100 years, but the architecture is only a small part of the story. In truth, it’s the comprehensive story of the school and its people that ought to matter. The institutional disregard for it is a sad reminder that when a community ignores or abandons its own history it can easily be forgotten forever. With that loss go the lessons, and institutional knowledge. It just dies. So while we can’t save the building, we can save the history, and most important of all, we can save the stories, wisdom, and honor the people.

Flint’s first high school stood where the McCree Court Buildings are today on Saginaw Street. In 1874, the new Flint High was built for a cost of $125,000 and situated at Second and Beach. The new Flint High School was designed to replace it for a cost of $500,000 (7.6 million today). Conceived in 1917, land was procured in 1919, and it was built in 1922 on 57 acres situated between Kearsley, Crapo, and Court Streets. It was a masterpiece of architecture constructed by Malcomson and Higginbotham, opening for classes in 1923.

The new layout included part of the old Oakgrove Sanitarium, which would be used as classrooms until it was razed in (the late 50s ) to make room for the new Flint Cultural Center. That only enhanced the Central location as it was nestled in its bosom. The school included its own radio station WFBE, along with a companion junior high school right next door. It quickly became the center of education for the rapidly growing city, fueled by the runaway success of one of its own alumni William C. “Billy” Durant.

A

When a new school was built in 1928 called Flint Northern to handle the massive overflowing student population, half of the students transferred to the new school. Meanwhile, at Flint High, the school became known formally as Flint Central, although it had been called Flint Central alternately and synonymously with Flint High School since at least 1917. Regardless, the school would maintain the iconic and classic block ‘F’ on varsity jackets, and letter sweaters. The athletic teams were known as the ‘Red-Blacks’ until 1930, when they became the ‘Indians’. That gave way to ‘The Phoenix’ at the end of the school’s run.

Talk of a new Flint Central abounded in the late 50s early 60s. Sites considered included the location of The Eastland Mall (now Courtland Center) on Court and Center, and further west on Center near Lippincott. However, the failure of Flint to annex or merge with Burton Township as part of the “New Flint” initiative, led to a decision to improve the existing building. A new Flint Northern was built instead, and Central ultimately received a new field house, plus other improvements. The traditions and the building continued on.

The block ‘F’ would come to symbolize the litany of world-shaking people who would craft the legacy of Flint Central. The list is undeniably headed by the aforementioned William C. ‘Billy’ Durant, who rescued Buick, invented General Motors, Frigidaire, Chevrolet, AC Spark Plug, mentored, managed, or partnered with J. Dallas Dort, Walter Chrysler, Charles Nash, C.S. Mott, David Buick, Louis Chevrolet, Alfred Sloan, Charles Kettering, among scores of others. He is considered by most to be one of the two most important people in automotive history with Henry Ford, and some name Durant #1.

By the end of the 20s another Flint Central student was focusing on his dreams in aviation. His name was Clarence ‘Kelly’ Johnson (see story on page 6). He would reinvent American aviation in much the same way Durant reinvented American corporate culture, structure, and economics. His work would lead to the first American fighter jet, the first commercial plane the Constellation, the U2 spy plane, the SR-71 Blackbird, the Stealth technology and the Stealth Bomber, and more. His work at Lockheed with Amelia Earhart, Howard Hughes, Charles Lindbergh, Jimmy Doolittle, Hap Arnold, and the development of stealth technology, Area 51 and the Skunk Works is absolutely legendary. Considered the second most important person in world aviation history, behind only the Wright Brothers.

Dallas Dort, the son of community icon, business leader, and Durant partner, J. Dallas Dort. Dallas’s own skills were exceptional and polished at Central as President of the Student Council among other leadership roles. In his professional career, President Harry S. Truman called on him to help craft the Marshall Plan that was the strategy to save Western Europe from being overrun by Soviet Communism during the Cold War. Dort’s work saved millions from a fate of unthinkable misery. A genuine Flint Central hero.

Don Coleman, Flint’s own version of Jackie Robinson was also a once-in-a-generation athletic talent, and barrier breaker. Coleman played high school football at at Flint Central, was also a swimmer, and played in the band. After leading Central to a State Championship in football, he played college ball at Michigan State, where he remains a legend. Coleman was an unanimous All-American in 1951, the first African American All-American football player at Michigan State. He was also the first Michigan State player to have his jersey number retired by the school. He was the first African American coach at Central, and in 1968, Coleman became the first African-American to serve on the coaching staff at Michigan State. Coleman was elected to the College Football Hall of Fame in 1975.

Frank Price was a standout student at Flint Central, member of the Saginaw Valley Champion Debate team, Editor of the school newspaper “The Arrowhead”, the Shutterbugs photography Club, Mohawk Hi - Y Secretary and Treasurer, Student Council Class President, acted in theater, starred in plays, and edited the yearbook Prospectus photographs. That was all good training for his career in Hollywood.

By the time he was 21 he was working in the entertainment industry. On the television side he produced or developed and supervised: The Virginian, The Six Million Dollar Man, Battlestar Galactica, The Rockford Files, and Columbo. He also invented the television mini-series.

Moving to the Motion pictures side of the ledger he became President of Columbia Motion Pictures. His work there was epic. His body of work running the studio included Kramer vs. Kramer, Tootsie, Gandhi, The Karate Kid, Ghostbusters, and E. T. The Extra Terrestrial. Price was responsible for turning out 9 of the top 10 grossing films in Columbia history. He moved to Universal in 1983 and there he saved Back To The Future, green lit Out of Africa, and then in the early 90s was responsible for Boyz ’n The Hood, The Prince of Tides, Bram Stoker’s Dracula, and Groundhog Day.

Price was also the Chairman of the Board of Councilors for the USC School of Cinema and Television. His team included Steven Spielberg, George Lucas, Robert Zemeckis, and David Geffen.

David Blight - A standout pitcher at Central he established a record for wins and also played basketball. Following a stellar career as an Indian, he went on to play baseball for Michigan State University. David was awarded the Pulitzer Prize in history for his book on Frederick Douglass Prophet of Freedom, and he currently heads the History Department at Yale.

Craig Menear

A fantastic swimmer at Central he set several school records that were never broken. He went on to a phenomenal business career and is the current CEO of The Home Depot

Bill Minardo Leader of the implantation and management of the legendary Flint Community Education Program

Herb Washington ‘Worlds Fastest Man’, Major League Baseball Player, Oakland A’s World Series Champion, Business Leader with McDonalds

Jim Blight

His professional work includes having created, refined, and applied an innovative research method called critical oral history

Coquese Washington WNBA player, President of WNBA Players Association, Head Coach at Penn State, and Associate Coach at Notre Dame

Jimmy Abbott Sullivan & Golden Spikes Awards, Olympic Gold medalist, Major League Baseball player

Clarence Peaks Heisman Trophy contender went on to a stellar career in the NFL with the Philadelphia Eagles

Andre Weathers U M football star, National Champion, NFL with the NY Giants

Catrice Austin

Named one of America’s top 100 Dentists

Genora Johnson Flint Sit-Down-Strike icon, and leader of the famed Women’s Brigade

Lynn Chandnois Michigan State football legend, and NFL Star with the Pittsburgh Steelers

Anthony Dirrell 2x WBC Super Middle Weight World Champion boxer

Dana Roberson Peabody Award Winning Journalist

Mildred Doran

One of America’s First female aviators, and the very first woman to attempt to reach Hawaii by air

Lloyd Brazil

Considered the greatest college football player of his era with only Red Grange as a contemporary

Daryl Gilliam Ins Agency Inc

Daryl Gilliam, Agent

30400 Telegraph Road Bingham Farms, MI 48025

Bus: 248-213-0091 Fax: 248-213-0092

In this column we talk to a variety of history professionals to answer your questions about history, archives, city records, genealogy, and more!

University of Michigan archivist, Colleen Marquis answers your most common preservation questions for your family documents and photographs. She is a professional with almost ten years worth of experience in document preservation and works at the Genesee Historical Collections Center at the University of Michigan - Flint.

records have made a surprising comeback in the last few decades. Hipsters, audiophiles, and

records unplayable, temperatures make

There are methods

Unwarping records, which are just likely to ruin the record as help with the warp - especially if

Another way records warp is by stacking them.

Vinyl records are HEAVY, as anyone who has had to move a robust collection up and downstairs will tell you, and the weight of vinyl on

vinyl can push the records into funky shapes over time. Vinyl records should be stored as upright as possible with no angles. Speaking of weight, make sure you store them somewhere that can handle that heft and use smaller boxes that are easier to lift. You also want to store the records off the floor (in case of flooding) and I strongly recommend a box with a lid to keep out sunlight, bugs, and dust.

Dust and dirt will also destroy your vinyl, especially if you are using paper sleeves. Dust and dirt collect in these sleeves and creates abrasions every time the record is removed and used. If you are a serious collector and player of vinyl records, invest in some polypropylene sleeves. Sure, they are more expensive but they keep dust out much more effectively and are much easier to use (rounded edges/stiffer material makes record access a breeze).

Finally cleaning. You should do a cleaning before and after every play with a carbon fiber brush. Run the brush over the record twice, once to discharge the static of the attached dust and once with the inner soft cloth portion of the brush to wipe the dust away. This should be done very gently and it’s a good idea to use gloves. The oils in your hands will destroy the vinyl so, just like with compact disks, do your best to not touch the playable section.

If you a record needs a DEEP clean as sometimes is the case with donated or vintage records use this little trick. Carefully coat one side of the record with wood glue (yes, wood glue) avoiding the paper label in the center. Wood glue is so similar to vinyl that it will only stick to dust/debris on the record. Wait for it to dry and then you have the incredibly satisfying job of peeling the wood glue off the record. The second verse is the same as the first, flip, wood glue, wait, peel.

The final piece about loving, preserving, and owning vinyl records is how you play them. A Crowsly record player might be $20 bucks at Meijer but the cheap stylus will start breaking down after as little as forty plays (and sounds terrible even with a new stylus). A damaged stylus is going to start skipping and taking chunks out of the records, sometimes so small you don’t notice it until it’s a problem. Archivallevel record players are actually not that bad ($300-$500+) when compared to what a DJ spends on professional turntables.

Vinyl records are very sturdy and have wonderful longevity. If properly handled, you and your descendants could enjoy these records well into the next few centuries.

by Ron Campbell

Itmay not have been the final straw, but then again something had to be done. It was the Spring of 1947, and sure it was just a quirk in nature. A series of spring storms that dumped, according to some accounts, 11” of snow on frozen ground on March 25th, followed with 48-degree temperatures and heavy rains on April 1st. With a quick thaw, the ground was saturated and there was little place left for the waters to go. By April 3rd the flood was on and would peak two days later, the worst in Flint’s history. The Flint River had flooded before, but back then there was far less development and the water could dissipate without much damage. Not now, not with the growth Flint had experienced in the last forty years. Now there were homes and businesses along the river. In one 24-hour period the river rose 32” and it was still raining. What was predicted to be a 2” rise in water every hour turned out to be 5” rise per hour. The river finally peaked on April 6th at more than 5 feet above flood stage leaving damage at a cost of over $121 million in today’s dollars and untold suffering and heartache to thousands of people.

The next day, Ford surveyed his Greenfield Village to see if the was damaged. Finding no damage, he returned home planning to inspect the auto plants the next day. Retiring after complaining he wasn’t feeling well, Henry Ford passed away at his home that evening, ironically in much the same surroundings of kerosene lamps and candles giving light and a fireplace giving warmth as when he was born.

"We just couldn't let them run a concrete ditch through the middle of downtown."

Meanwhile, back in Flint, talk turned once again to flood control along the river. The cost of human suffering, lost days of work, lost production and the damage caused was just too great not to do something. Enter the Army Corps of Engineer. The Corps is a branch of the U.S. Army established in 1802. They provide design and engineering services for the federal government. Since the early 1900s the Corps have served thousands of communities across the US with, dam designs, hydroelectric plants, and flood control. It would take Flint another 27 years for everything to come together for flood control to actually get started. Construction for their design for the Flint River Flood Control project began west of Downtown, in “Chevy in the Hole”. However, once city leaders saw the finished product, a halt was placed on the work. One local environmentalist told me at the time, “we just couldn’t let them run a concrete ditch through the middle of downtown.”

Flint was not the only community affected. All across the Midwest and Michigan similar stories can be told. In Dearborn, on April 6th, the floods knocked out the power to Henry Ford’s factories and to his estate at Fair Lane. Ford's home was without heat, except for the fireplace, and without lights except candles and kerosene lamps.

So ‘who are ya gonna call?’ How about one of the most talented and revered landscape architects of the 20th century, Lawrence Halprin. Halprin was educated at Cornell University, University of Wisconsin, Frank Lloyd Wright’s Taliesin and Harvard earning degrees in Science, horticulture and landscape architecture. He and his fellow

Title photo: Girl walking along cascading wall when park was operational

Above: The same "room" in the park, today, in disuse; Photo: Jenny Lane Studios

Left: Tiered, grassy area with water feature and shade trees used for public events

Below left: The riverbank as it was originally constructed by the Army Corps of Engineers; This section was near the "Chevy in the Hole" plant, and was planned to extend through the city, bisecting Flint with a "concrete ditch"

Photo: Jenny Lane Studios

Below Right: Lawrence Halprin

students at Harvard School of Architecture and Design included Catherine Bauer, Philip Johnson, I.M. Pei, and were taught by Walter Gropius and Marcel Breuer. All people recognized with the Mid-Century Modern movement.

By 1974 Halprin’s office, in San Francisco, was involved in designing Flint’s flood control project. For me, it would be one of those by chance life changing moments as my path would cross with Halprin and design philosophy. It was an experience which would influence the rest of my career. As a third-year graduate student at the University of Michigan School of Architecture and Urban Design, I was able to talk three fellow students and Professor Himes into allowing us to do an independent study project in my hometown, Flint. Our project was the redesign of several blocks either side of Saginaw Street from

Union Street north to the river. Hence, my path was destined to cross with Halprin and his studio.

Halprin’s firm was commissioned to create a linear public park on narrow strips of land either side of the Flint River based upon the Army Corps requirements. The design approach, which Halprin pioneered, was a” Take Part Design Workshop”. It was a unique way of gathering design input by actively engaging citizens from all walks of life. The two-day experience was eye opening for me and one which I carried into my own practice for the design of churches, schools and the development of cities and neighborhoods. It is now a widely used design technique by architects and planners throughout the US.

design that was sensitive to the environment and embraced it in the design. The design was a series of canals that created five interconnecting block long parks containing an amphitheater, market stalls, steppingstones for the brave, a fountain, a cascading wall of water powered by an Archimedes Screw and a fish ladder. Normally Halprin designs were inspired by natural forms and features, Flint Riverfront Park was inspired by the urban environment and architecture of Flint. Angular walls, trapezoidal concrete walks and canals are interrupted and softened by manicured lawns and shade trees.

Just as amazing, was Halprin’s approach to the solution and the criteria he placed on the program that initiated the design. Halprin, “… not only used an Army Corps of Engineers flood control project as its foundation, but also deliberately provided access to and connections with the river itself, seeking to represent and celebrate the natural function and form of the river in its urban setting.” Like many of Halprin’s other designs, the park is separated from the surrounding urban environment by terraced landscaping. The final design blended the manmade environment into the natural environment. A natural environment that was so much more than trees, animals and water. It includes the force of nature that if not accounted for would eventually destroy what ever man would create. Halprin along with designers Satoru Nishita, Steven Holl and John Cropper tapped the power of the river and nearby run off to create an early example of green infrastructure, a

Years later I would visit this marvel of artistic design and engineering skills with the Illinois State Preservation Architect whose one request on his visit was to see “Halprin’s greatest work.” Preparing him that we would only see a shadow of what it once was we were unexpectedly, and mistakenly, included in the” Back to the Bricks” parade down Saginaw Street when we, in my mature Miata, were directed to the parade lane. He enjoyed every minute of the slow procession down Saginaw laughing and taking photos all the way. But the best part of his visit was at the end of the parade route where we found our destination in full operation mode with people enjoying the urban park as it was envisioned so many years earlier. Later it was discovered that this was the work of a local resident, through his own ingenuity, was able get the fountains and water walls in the park running.

Today the park stands idle and visitors miss the magic that a Halprin’s design and nature brings, via the river, into Downtown Flint. We can only hope that future generations will experience this iconic design of the 1970s. History shows that at one time we did think about the environment and searched to design ways of bringing it into our daily lives. It now falls to this generation to preserve this history and to save what remains of Halprin’s Masterpiece before it is too late.

Ron Campbell, AIA, is a Principal Planner/ Preservation Architect for Oakland County Economic Development

By Michael G. Thodoroff

It has developed into as venerable establishment as there is in Genesee County. Working on its 66th year of operation, the Auto City Outdoor Event Center continues to provide family entertainment while launching the professional careers of many aspiring racers –and a national champion. Its story witnessed the track rise from a farmer’s field to a facility overflowing with crowds, eventually gaining the reputation as the “fastest half-mile in the state.”

Before the Auto City Outdoor Event Center came into being, the only game in town for local car racers was a track located just north of Flint called Dixie Motor Speedway that had been running race car programs since 1948. A young man by the name of Al Kukla was working for his boss, Joe Grabenhorst, at his State Automotive Supply business in Flint during the early 1950s. Kukla was racing at Dixie under Grabenhorst’s sponsorship. Joe, a race fan himself, went

out to watch ‘his’ car in action anytime he could. One particular Saturday night saw Kukla clean the field in every event he entered. When Al and Joe went to collect the winning purse at the end of the night’s racing, promoter Bill Shimler handed over a miniscule amount of money. Unflinchingly, Grabenhorst quickly gave the prize back adding that Dixie needed that token more than his race car did. Shimler only replied that if he didn’t like the payouts, then “go build your own racetrack!” That, fellow Genesee County historians, is exactly how the originally known Auto City Speedway came into being.

Grabenhorst joined forces with his brother, George, and they began in earnest to find some land to start their project. They eventually discovered an old 37-acre farmer’s field located at 10205 N. Saginaw St owned by Frank Lovejoy. With the support of a handful of other investors, Joe sealed the deal and started construction in 1954. On April 16, 1955, the first green flag dropped, signifying the official opening of Auto City Speedway.

winning another race before a packed grandstand, circa 1962; Photos courtesy of John Doering, Jr.

While construction was taking place, a young Jack Doering, future promoter, was racing around Dixie Motor Speedway in his 1937 Ford flathead V8 engine modified stock car. He was typical of a weekend racer who would hold down a day job and then after hours would work on his race car to get it ready for the weekend races. Doering’s journey into the life of a racetrack promoter was different than most others who came into race track promoting. Not having his car ready to race one night in 1958, Jack instead decided to go Auto City as a spectator. While he was roaming the pits, a track employee by the name of Fred Wright asked Jack if he could help with the spectator head count (done manually in that era) as he needed this info for bookkeeping purposes. It was then that he was also introduced to Joe Grabenhorst. Doering agreed but that job didn’t last long, as Joe talked him into staying on as the pit steward (a.k.a. supervisor of the pit area).

Even though Auto City’s 1958 season ended in bankruptcy, Joe Grabenhorst scraped up enough capital to buy out the remaining assets of the seven original partners. Since Joe and his brother George had business commitments in Milwaukee, they leased the track to Bob George. Doering stayed on as the pit steward, with the added responsibility of preparing the track’s dirt surface.

Bob George was no stranger to the racing game, as he was already the promoter of a sizable drag strip in McBride, Michigan. One 4th of July, however, he was faced with a conflicting schedule with McBride, and was unable to attend Auto City’s program. As the parking lot filled up, Doering, wondering where his promoter was, finally placed a call to Joe Grabenhorst in Milwaukee to ask him what to do. Without hesitation, Joe said, ”You run it!” With that, George decided to focus on his drag strip as the racetrack promoting career of Jack Doering waived the “green flag.”

around 30 “street stocks.” Slowly but steadily, the purses grew from approx. $380 in 1959 to--an unheard of at that time--$3000 by 1961! Ever since, Auto City Speedway has run the most successful Saturday night racing program in the state of Michigan. Ironically, Grabenhorst and Doering purchased Dixie Motor Speedway from Jones and his partners in 1969. Jack Doering became half owner of Auto City in 1962 which led to an amazing 23 years of partnership with Grabenhorst.

Auto City underwent a year of rebirth in 1986, the year Doering made the decision to resurface the track with asphalt. Previous to 1986, all local racing venues were dirt tracks and there was a “religious hope” the wind would be blowing away from the grandstands. However, when daylight savings came to Michigan, it fundamentally devastated dirt racing. It used to be at 8:00p.m. it was getting dark allowing the track to be watereddown again right after car qualifying. With DST it’s 9:00 – or 10:00p.m. and the sun is still out. As a result, halfway through the racing program it became “dustbowl city”!

By this time, the competition between Dixie and Auto City was apparent, but Doering wanted to start off his promoting tenure on a good note. He went to Dixie’s promoter, Ed Jones, and introduced himself as Auto City’s new boss. Until then, Auto City always ran on Fridays and Sundays. Jones informed Doering “he” was running on Friday and Sunday nights, and Jack could have what was left. Of course, Jack Doering left Dixie smug and undaunted.

Doering knew a number of car dealers in the area and got them involved in running sponsored cars at Auto City, eventually landing

Although going to asphalt was a risky – and expensive – move it paid off because the crowds soon doubled, which necessitated the addition of more grandstands. Plus, the program could start on time since the asphalt surface obviously does not need the preparation that dirt requires.

Jack Doering earned the respect of his peers over the years, due in part to his sincere dedication to the sport of racing. He was the catalyst behind the organization of the Michigan Speedway Promotors Association which was founded on 1972 with the purpose of helping racing promotors throughout the state with their concerns. Instead of being competitive with one another, this association encourages the promoters to cooperate to make the sport more enjoyable for not only the fans, but for the race teams as well.

Because he was a lifelong resident of the Flint area he believed in his community and did his part to help out. He initiated a practice of allowing various charitable organizations to come in and put on their own programs to help raise funds for their cause. Organizations from the boy scouts to the area’s local fire departments have taken advantage of this courtesy for years. He watched his two sons get involved with the track with Jason earning the responsibility for all of the track’s concession activity while John Jr. actively raced in the premier Super Stock class and handled some of the organizational duties.

However, the one element all businesses must experience in order to survive is change. The decade of the 1990s saw a tremendous shift in not only socioeconomics but in business, as well, in the form of the internet, smart phones, web sites, social media, chat rooms and the like. After 40+ successful years of promoting, “Racetrack Jack” decided it was time to pass on the opportunity to the next generation.

Joe DeWitte, owner of Edgecraft Construction Company, was a car racing enthusiast and got involved in the sport by sponsoring a car driven by good friend Dr. Bob Ducharme, an Oakland County practicing chiropractor. After a couple of successful seasons in Auto City’s Pro Stock division, Joe and Dr. Bob (everybody called him “Dr.” Bob!) worked out a purchase agreement with Jack Doering in 2000. While a legend gracefully bowed out, the enthusiasm of DeWitte and Ducharme combined to keep Auto City’s legacy growing. “Jack Doering was one of the greatest local racetrack promoters of his time,” DeWitte affirmed. “He gave me some insight on how to streamline the operation of running the facility of which I still refer to today.” Later that year the new business partners created Auto City’s first web site. While it was a great “ride” running the track with Joe, after a few years, Dr. Bob’s growing family and thriving chiropractic business required that he keep his priorities in order.

DeWitte continued the operations with tremendous support from Marketing and Promotions Director Sharon Fischer. Because of the national economic downturn after 2009 and a declining car count, they strategically looked at creative opportunities for the track. By 2014 after much thought and calculation, they decided to re-brand the facility as an outdoor events center. Now, the grounds at the historic Auto City Speedway have been found to be perfect for corporate outings, concerts, festivals, car shows, trade shows, family reunions, outdoor movies, and sporting events, including driving and ride-along schools. It can also serve as a host for automotive original equipment manufacturers, tire manufacturers, race teams,

advertising agencies and media. And remember, they can host charity walks or runs on the same ¼ or 1/2-mile paved oval that host stock car racing’s finest. Expanding on the outdoor event center is a large infield which provides an excellent surface for most events. With electrical access and 20 acres of parking plus another area (35 acres) adjacent just south of the track can be used for camping, parking, etc. All-in-all, the facility lends itself to hosting events with thousands of attendees.

Through all the recent years of re-defining the Auto City Outdoor Event Center, Joe DeWitte and Sharon Fischer have diligently worked – and continue to work – to put on the best show possible, all while giving their loyal fans something new to look forward to. Joe repeatedly says, “I take pride in continuing the legacy of the "Pure American Pastime.”

Speedway Alumni

Tommy Maier - 1993

Mike Eddy - 1995

Jay Woolworth - 2003

"Ten-Grand" Tommy Bowles - 2003

Tony Brabbs - 2010

John Doering, Jr. 2011

Sam Faur - 2018

Jack Doering - 1987

by Tracy Leigh Fisher

The1920s were a time of unhindered speculation, daring-do, and wild and reckless behavior. Women had finally won the right to vote, and tearing off their constricting corsets of the past, many of the young chopped their tresses, adopted the heavy makeup, scandalously short dress, and cigarettes of the flapper personae. Prohibition was in full swing; the speakeasy and gin joints were frequented by those who flaunted the law, and their liquor was provided by gangsters.

Air travel was still in its early days. Folks visited dirt air strips to observe daredevils, called “flying gypsies” or “barnstormers”, who performed terrifying stunts to stun and amaze onlookers. Without safety ties, men walked on wings in mid-air, dangled from wheels, turned their engines off thousands of feet in the sky, or dove straight at the earth just to pull up at the last minute. Often, these feats ended in wasteful tragedy, but the thrill continued to draw crowds.

It was an age of euphoric and often foolhardy optimism.

Four days after Charles Lindbergh completed the first solo, non-stop, transatlantic flight from New York to Paris, amidst the worldwide excitement of his accomplishment, James D. Dole, Hawaiian pineapple magnate, wanted in on the action. On May 25th, 1927, he announced that he would award a new prize of $25,000 ($370,000 in today’s 2021 dollars) for the first person to fly from the mainland to Honolulu, and $10,000 to the second, completion within the year. While the big fish he wanted, Lindbergh, wasn’t interested, there were more than 35 inquiries. It became clear it should be a race

A $100 entry fee weeded out the big talkers (including a dirigible hopeful) and the count dropped to eighteen, still a surprising number. The “Dole Race”, a 2,400 mile trip, almost exclusively over deep ocean without landmarks and much of it at night, would start at Oakland Field in Oakland, California, taking an estimated 24 hours. A full moon would assist the fliers in their quest, so August 12th was chosen. This narrow window presented a challenge for the entrants to both find an aircraft and properly outfit it for the trip.

Twenty-two year old Mildred Doran, born in Ontario, Canada, had lived on the south side of Flint, Michigan since the age of three. At sixteen, her mother died and her father was unable to continue raising her and her three siblings, so their care fell to an aunt and uncle. After graduating from Flint Central High School in 1923 with honors, Mildred obtained a teaching degree by twenty from Eastern Michigan University, known at the time as Ypsilanti Normal School. She then began teaching fifth grade in Caro, Michigan. Previously, when she had been nineteen, she and a friend had attended a “flying circus” at Grand Blanc Township’s Lincoln Airfield, an airstrip on the corner of S. Saginaw Street and E. Maple Avenue. It was common for barnstormers to offer patrons a ride for a price; one was proffered to a hesitant Mildred. Because her friend was eager, and with the encouragement of the airfield’s owner, William Malloska, Mildred— not wanting to appear cowardly—agreed. That ride changed the trajectory of her life. “…After we began rushing through the air, twisting and turning, it seemed like some particularly glorious ride, on some miraculously smooth highway.” Every spare minute she could allot was spent at the airfield, and whenever she had a chance to take control of the planes she went aloft in, she snatched it up.

When the “Dole Derby”—as it was dubbed by the papers— made headlines, William Malloska, who owned Lincoln Petroleum Company with 70 gas stations throughout mid-Michigan along with the airfield, saw his chance to sponsor an entry. Upon announcing his plan, Mildred, a favorite of Malloska’s, perked up, asking if she could go. A woman had never attempted to cross the Pacific by air, and Malloska, a colorful promotor, knew a choice opportunity when he saw it. While Mildred had not accumulated enough hours to obtain a license, it was determined that she would ride along. Augie Pedlar, 24, won the pilot’s position in a coin toss in the offices of the Flint Journal against “Slonnie” Sloniger, two of the aviators who flew in and out of the Lincoln Airfield. Entries closed on August 2nd, so with little time to spare, Malloska went in search of a plane. His first choice, a Lincoln Standard Aircraft giant monoplane could not be completed in time, so he settled with a Michigan-made Buhl Air Sedan sesquiplane (commonly confused with a biplane). Known for its quality, the Buhl was fitted with a Wright Whirlwind J-5 Engine, similar to Lindbergh’s. The sponsorship “Lincoln Oil” was painted plainly on the side of the white fuselage, wings and nose in bright red, with blue on the tail. At the unveiling, the Miss Doran was christened with a bottle of ginger ale.

Because Lincoln Airfield’s dirt airstrip would be too short and rough to accommodate a clean takeoff for the fully loaded Air Sedan, Pedlar, Malloska, Doran, and her great dane puppy, Honolulu, left from Grand Blanc, planning to prep and depart for California from Detroit’s Ford Field. On the way, their flight was waylaid by a wicked storm, which flung the plane’s door open, almost throwing its passengers out, and forcing them to reroute to the Selfridge Field in Mt. Clemons. From there they puddle-jumped their way across the continent. At each pitstop, the press and throngs of thousands were enamored with the brave “flying school marm” with the cap of wavy brown hair, olive complexion and wide-set blue-gray eyes. She made news coast-to-coast, “There isn’t a thing nowadays a man can do that a woman can’t…I want to be the first woman to make a long, non-stop flight.”

The 18 Dole Racers made their way to Oakland, California. More of them dropped out due to financing or were disqualified for safety, inspection, or testing reasons by the Department of Air Commerce. The start date was moved to August 16th due to lack of time for entrants’ qualifying. The monoplane, The Hummingbird, qualified, but on the way to Oakland, near Los Angeles, it crashed into a fog-covered embankment, burst into flames and killed the crew. Spirit of Los Angeles, the plane sponsored by Hoot Gibson, Hollywood cowboy star, met its fate in the bay; the crew was saved but the craft was junked. The Miss Doran’s first navigator’s skills were deemed insufficient, so a last minute replacement, the highly competent Cy Knope, joined the team. On the way to the starting field, Augie Pedlar crash landed in a wheat field due to spark plug malfunction, but was able to complete repairs and fly onward. By the day of the race, only eight planes lined up.