6 minute read

Rooted in Research—Zoysiagrass, How Did It Get to the U.S.?

ROOTED IN RESEARCH

ZOYSIAGRASS, HOW DID IT GET TO THE U.S.? —PART TWO

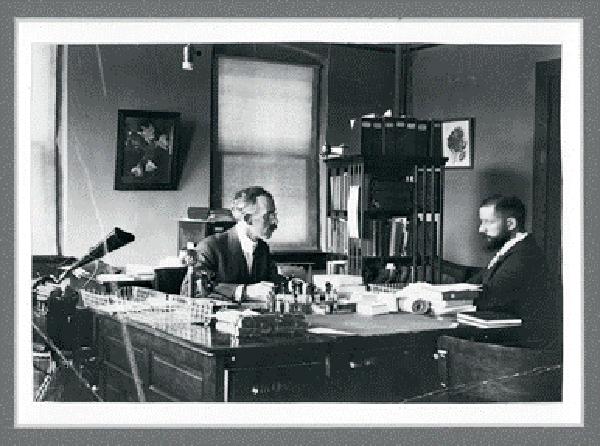

In 1898, Dr. David G. Fairchild was named the first head of the USDA’s Office of Seed Plant Introduction. In 1906, early in his Asian travels, Frank N. Meyer submitted two zoysiagrass varieties from North Korea to the U.S. Dr. Fairchild (left) hired Frank N. Meyer (right) as a plant explorer which led to Mayer’s 13 years of travel throughout Asia. In 1912, Charles V. Piper introduced Zoysia matrella to the U.S. from the Philippines.

By Mike Fidanza, PhD

Let’s continue our historical review of the plant explorers who first introduced zoysiagrass to the United States.

Dr. David G. Fairchild (1869-1954) was a botanist and was named the first head of the USDA’s Office of Seed Plant Introduction, in Washington, DC, in 1898. In 1902, he traveled to Yokohama, Japan, and collected what he listed as Zoysia pungens and described it as “very fine-leaved” and a “lawn grass which forms a most beautiful velvetlike turf.” The plant was sensitive to frost and may have originated from southern Japan. Therefore, it is speculated that what he may have collected was either Zoysia matrella or Zoysia pacifica.

Dr. Fairchild collected another zoysiagrass also from Yokohama, also listed as Zoysia pungens, and described it as having coarser (wider) leaves and better hardiness. It is assumed this meant cold hardiness, and therefore it is speculated that it was most likely Zoysia japonica. However, both submissions were labeled as Zoysia matrella in the U.S. National Plant Germplasm System as PI 9299 and PI 9300. Unfortunately, neither specimen is available today for further examination and correct identification. Of note, Fairchild was responsible for the introduction of more than 200,000 exotic plants and varieties into the U.S. including mangos, nectarines, dates, bamboos, flowering cherries, pistachios, kale, quinoa, avocados, soybeans, wheat, rice, and cotton. Fairchild wrote four books that described his work and world travels, including The World Was My Garden: Travels of a Plant Explorer, which was published in 1938. He used his own photographs and illustrations for his books, and from his travels, he was able to provide descriptions of native cultures before their modernization.

In 1916, Fairchild and his wife, Marian (daughter of Alexander Graham Bell), bought a winter home in the Coconut Grove neighborhood of Miami, FL. He named the home “The Kampong,” in honor of the place he lived in Java (Indonesia) where he spent time collecting plants. He established gardens on his nine-acre property that contained plants he collected from Southeast Asia, Central and South Americas, the Caribbean, and other tropical locations. Today the Kampong Garden is one of five gardens in Florida that form the National Tropical Botanical Garden, and it is open to visitors.

Fairchild was a member of the Board of Regents of the University of Miami from 1929 to 1933 and served as Chair in 1933. Also in 1933, he was awarded the Public Welfare Medal from the U.S. National Academy of Sciences “…for his exceptional accomplishments in the development and promotion of plant exploration and the introduction of new plants, shrubs, and trees into the United States; …in recognition of distinguished contributions in the application of science to the public welfare.” It is the most prestigious honor conferred by the Academy. In 1938, the Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden in Coral Gables, FL, was named after him.

Frank N. Meyer (1875-1918) was born Frans N. Meijer in the Netherlands, and was educated at the Hortus Botanicus, a famous and historical botanical garden in Amsterdam. There he worked as an assistant to Hugo de Vries. Of note, de Vries was a botanist and one of the first geneticists, known for suggesting the concept of genes, and for rediscovering the laws of heredity thus confirming Gregor Mendel’s earlier work on the subject. Meyer immigrated to the U.S. in 1901 and started working for the USDA in Santa Ana, California, and eventually became an American citizen. Fairchild hired Meyer as a plant explorer, which led to his relocation to Washington, DC. Of particular focus was finding drought resistant plant varieties suitable for dry land farming driven by agriculture expanding into the Great Plains at that time.

In 1905, Meyer began his 13 years of travel throughout Asia. The plants he sent back were distributed to various USDA plant introduction stations and incorporated into plant breeding programs. He sent back over 2,500 plant varieties including alfalfa, sorghum, citrus, stone fruits, nuts, and soybeans, including the first oil-bearing variety. He also sent tree and shrub specimens to Harvard University’s Arnold Arboretum. Fairchild reported that Meyer’s notes about the plants he collected “…are full of suggestions to plant breeders.” Early in his travels in 1906, Meyer submitted two zoysiagrass varieties from North Korea. The first he described as “a perennial grass growing but a few inches high, well adapted for lawn purposes.” The second he noted as “…excellent for golf links, lawns, etc.” In 1907, he submitted zoysiagrasses from Shanghai, Shantung, and Tainfu, China. All his samples from Korea and China were considered to be Zoysia japonica. During Meyer’s last expedition in 1918, he collected wild pears that were naturally resistant to fire blight disease. He was traveling down the Yangtze River, but a few days after boarding the boat, his body was found in the water. The cause of death was listed as accidental drowning, and he was buried in Shanghai. His unfortunate death and the circumstances of the incident are still a mystery, and a Hollywood movie about Meyer would probably sensationalize him as “plant explorer by day, secret spy by night.” His travels are chronicled in the book Frank N. Meyer, Plant Hunter in Asia (1984). Because Meyer was so well-respected among his peers and colleagues, The Frank N. Meyer Medal for Plant Genetic Resources was established in “recognition of his contributions to the plant germplasm collection and use in the United States and his dedication and service to humanity…” The award is presented annually by the Crop Science Society of America. In addition, zoysiagrass seed collected in Korea in 1930 was further propagated and eventually released in 1951 as the variety ‘Meyer’ zoysiagrass in his honor. Charles V. Piper (1867-1926) introduced Zoysia matrella from the Philippines in 1912. He described it as “… abundant near the seashore…” and “where closely clipped it makes a beautiful lawn.” Manila is the capital of the Philippines, and thus ‘manilagrass’ is a common named still used today for Zoysia matrella. Piper was an agrostologist with the USDA’s Division of Forage Plants. Later in his career, Piper shifted his focus from forages to turfgrass. In 1917, he coauthored one of the first turfgrass science textbooks, Turf for Golf Courses, with Russell A. Oakley. Piper’s career and accomplishments in turfgrass science warrant coverage in his own article for Rooted in Research. There have been others who collected zoysiagrass germplasm from far and wide, but these botanists, agrostologists, plant explorers, and adventurers were the first to bring zoysiagrass into the United States. Source: Patton, A.J., B.M. Schwartz, and K.E. Kenworthy. 2017. Zoysiagrass (Zoysia spp.) history, utilization, and improvement in the United States: A review. Crop Science 57:S37-S73. (doi: 10.2135/cropsci2017.02.0074)

Mike Fidanza, PhD, is a professor of Plant and Soil Science at Pennsylvania State University, Berks Campus. Cale Bigelow, PhD, is a professor of Turfgrass Science and Ecology in the Department of Horticulture and Landscape Architecture at Purdue University in Indiana. They are teaming to provide a Rooted in Research article for each issue of Turf News. All photos courtesy of Mike Fidanza, PhD.