PLEIN AIR ART | RAVINE

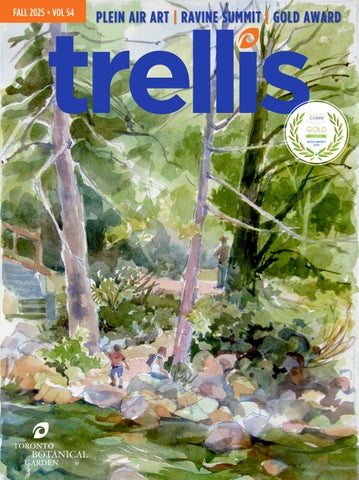

TRELLIS MAGAZINE has received the 2025 Media Awards Silver and Gold Laurel Medals of Achievement for Publisher/Producer: Magazine (Consumer Trade) presented by GardenComm Communicators International.

“This award is one of the top recognitions in garden writing, commented TBG CEO Stephanie Jutila.“An accolade from our peer circle of garden communicators— congratulations to the Trellis team of TBG staff and volunteers and Art Director June Anderson who are led by our Editor Lorraine Hunter who brings her love and passion for the garden into every issue.”

This international award acknowledges individuals and companies who achieve the highest levels of talent and professionalism in garden communications. The 2025 competition had more than 125 entries in 40 categories.

Trellis received the awards for the Fall 2024 issue. This is the second gold medal for Trellis which won the same category in 2023.

Congratulations also to Trellis contributors Sonia Day and Janet Davis who each won Gold Laurel Medals.

Sonia won for her book The Newfoundland Lunch Party: A Sisters of the Soil Novel with Recipes. Janet won for her article The Allure of Black in the Sept.-Oct. 2024 issue of The American Gardener magazine.

“These awards recognize the best of the best—communicators who inspire, inform, and elevate the gardening world through outstanding storytelling, imagery, and innovation,” says C.L. Fornari, president of GardenComm.

Since the early 1980s, the GardenComm Media Awards program has recognized outstanding writing, photography, graphic design, and illustration for books, newspaper stories, magazine articles, and other works focused on gardening.

The GardenComm Media Awards showcases writers, photographers, editors, videographers, social media managers, publishers and trade companies that have demonstrated excellence in garden communications in print or electronic communications.

GardenComm, Garden Communicators International, is an organization of professional communicators in the green and garden industry.

[4] FROM THE GARDEN Power of Immersion in Nature

[6] TONY DIGIOVANNI Time for Reflection and Celebration

[8] LEARNING Can Digital Tools Support the Planet?

[10] TBG GARDEN SHOP AND WELCOME NEW TEAM MEMBERS

[11] CELEBRATING 70 Years of Growing Together

[12] HISTORY OF TBG PHILANTHROPY

The Value of Giving Back

[15] HEARTS & FLOWERS

When you support TBG you support Community

[16] SUMMER FACES

Interns bring fresh enthusiasm to the Garden [18] CONFESSIONS OF A NEWBIE TTGG for the very first time [20] HISTORY OF GARDENING

Archival Library Display on view now [24] CHRISTMAS WITH MILNE HOUSE

25 Years of Holiday Tradition and Giving Back [26] DANDELION CAFÉ

New restaurant opens in Edwards Gardens [28] CONTAINERS

Give your imagination free rein

[32] WHEN TO BRING HOUSEPLANTS INSIDE

Some enjoy extended summer vacation [36] WHITE-TAILED DEER

Most numerous animals in North America [40] DEER PROOFING

How to protect your garden from urban wildlife [42] GUIDELINES-NOT RULES Canada releases new Plant Hardiness Zones [44] LISTEN AND LEARN

7 award winning ecological gardening podcasts [46] THE BOTANY OF BOUYANCY

Totoro reeds central to an entire civilization

[50] KYOTO GARDENS

Designed for serenity and year-round interest [60] BOOK SHELF

Three classics on the fine art of gardening [62] GOOD THINGS ARE HAPPENING [64] PUZZLE PIECES Garden Birds

COVER PHOTO: EN PLEIN ART EARLY MORNING ADVENTURE IN THE GARDENS BY ALEX SHARMA. SEE EN PLEIN ART EXHIBITION & SALE OCT. 4 TO 18 THE TBG

ABOVE PHOTO: DEER PROOFING. SEE PAGE 40. PHOTO: PEXELS

Stephanie with Lorraine Hunter, Trellis Editor

THE PAST few years have taught me new aspects of my relationship to gardens and nature, in ways I didn’t expect. Personally, I was navigating an unexpected health diagnosis that interrupted my capacity to maintain stamina for my regular gardening tasks.

Long defining my gardening and plant passion for the physical activity and resulting beauty of my labours, I found myself needing to slow down the physical aspects of gardening while I navigated medical care and related healing. And yet, my relationship with gardening and nature deepened, despite the slowing of the physical activity. And that is where I continue to experience awe and wonder.

The awe and wonder lead me to ponder the result of actively engaging with nature, versus when I choose to observe or reflect on it. And whether the observation and space to reflect on nature may be what is driving the deeper connection to gardening and nature, after all.

My active engagement with nature ranges from gardening to immersive nature-based experiences such as walking in the ravine, harvesting fresh flowers or herbs from my garden or taking in the landscape in big doses—all of which bring about a decent amount of physical vigour.

When I switch to observing mode, I am often sitting quietly on my patio, watching birds, listening to the sounds of nature colliding with the hum of the city; and even taking time to study the intricacies of the plants and the pollinators—insects and birds—in my midst.

At Toronto Botanical Garden we provide our community with all three aspects of connecting with gardening and nature—reflection, immersion and observation.

REFLECTION: A new awareness has been emerging for me—how vital reflecting on nature through art is to

filling my physical spaces, i.e., the books I read, or the images I hold in my mind’s eye. While these have long been aspects of my relationship with nature and gardening, it was only when I had to slow down the physical gardening that I could appreciate how vital reflection on nature is to my overall well-being.

IMMERSION: If you are all about the physical experience of immersing yourself in gardening and nature—the autumn days are full of splendour and horticultural beauty. From the physical labours of our horticulture volunteers to hands-on workshops with plants, simply walking and taking in the garden, to tours into the ravine or wellness programs that immerse one in the natural areas, TBG has many ways you can immerse yourself in gardening and nature.

For example, the Fall Ravine Festival on October 4th is a great opportunity to immerse yourself in the Ravine, while also learning from community partners.

OBSERVATION: From simply sitting in the garden, to taking a class on botanical drawing, or observing the abundance of horticultural inspiration in Trellis magazine or from the Weston Family Library collection.

This autumn, experience firsthand how the plein air painters skilfully observe nature with the TBG’s Essence of the Garden Plein Air Art Exhibition and Sale October 4 to18, showcasing 70+ works painted at Toronto Botanical Garden, reflecting and celebrating the Garden we all love.

Maybe you will find a painting that speaks to you and helps you reflect on nature when you are not physically at the garden!

Stephanie Jutila TBG CEO

04 12 to 4 p.m.

Whether you’re a nature enthusiast or looking for a fun family outing, you’ll enjoy hand-on learning while exploring the gardens and ravines.

This site-specific exhibition includes artwork created in the Toronto Botanical Garden, Edwards Gardens, and the adjacent ravine.

Our annual eco-minded, nature-inspired, relaxed shopping experience with over 60 local vendors, live music, festive workshops and food trucks. NOV 21 23 & 28 30

This intimate and interactive high-flying circus performance features aerial artistry and acrobatics. This feel-good show can be enjoyed solo or as a holiday outing with family and friends.

By Lorraine Hunter Trellis Editor

“PURPOSE

This phrase may not be original but that’s the mantra Tony DiGiovanni lives by. “My purpose is to enhance lives,” says the Chair of Toronto Botanical Garden’s Board of Directors. Tony may have retired three years ago as Executive Director of Landscape Ontario Horticultural Trades Association, but his passion for gardens and

dedication to the benefits of nature did not retire with him.

Tony has been associated with the Garden since well before it became the TBG. “I first visited as a horticulture student at Humber College 47 years ago. At that time, it was called the Civic Garden Centre,” he recalled during the TBG’s Annual General Meeting in June. “I used

the library to support an essay. Years later as a grower, horticulturist, garden communicator and teacher, I attended many inspirational events, seminars and conferences here.”

Not only was Tony connected to the Garden, professionally, throughout his career as a grower at Etobicoke’s Centennial Park Conservatory and then coordinator of the Landscape

“My purpose is to enhance lives.”

—Tony DiGiovanni

Thanks to the dedication, creativity and sacrifice of our amazing staff plus the thoughtful stewardship of the previous and present Boards’ Finance and Budget Committees and some incredible donors, we did not just weather the storm: we transformed it into a season of growth and hope for the future.”

Tony also gave credit to CEO Stephanie Jutila. “Under very difficult circumstances she developed fundraising and operational plans to change the Garden’s course…She was able to mobilize support from wonderful donors and community and to support her (our) amazing staff by her encouraging, nurturing and caring manner.”

He also had a special thank you for several unnamed TBG supporters. “There are people anonymously supporting us in so many ways and I believe there are more out there just waiting for the right time,” he said during an interview.

Tony’s hope for the future is that the City will embrace the TBG’s dream to become a major Toronto attraction.

“Since the idea of the Toronto Botanical Garden was first envisioned, it has served as a living legacy to the values of sustainability, education, beauty and community.

“It’s easy to measure success in numbers—in revenue, attendance or membership—but the true success of Toronto Botanical Garden lies in its deeper impact: the way it connects urban life with natural beauty, how it inspires environmental stewardship, how it cultivates wonder in every generation and how it enhances lives.”

Technology program at Humber College and Executive Director at Landscape Ontario, but personally, he has happy memories of bringing his daughter to Edwards Gardens during summer vacations.

As one of the TBG’s biggest cheerleaders, Tony was thrilled to announce at the AGM that the organization had been able to turn its

financial picture around over the past year from a substantial deficit to a healthy surplus.

“This evening is a time for reflection and celebration of resilience, renewal and the remarkable power of community,” he said. “Just one year ago, we faced a sobering financial reality. We were challenged to rethink, rebuild and reimagine.

Tony admits: “I was afraid of retirement. I had a great time during my career.” Not only is he Chair of the TBG’s Board of Directors but Tony also serves on four additional boards— Vineland Research and Innovation Centre, Canadian Trees for Life, Maple Leaves Forever and Ontario Horticultural Trades Foundation.

“They’re all connected,” he says. And they obviously offer him a fulfilling way to carry on enhancing lives.

By Natalie Harder Director of Learning

I’ve always thought of nature and technology as opposites.

Nature is where I go to unplug, slow down and feel rooted again. It’s where I don’t have to check my phone. So much of our language supports that idea—“getting away,” “disconnecting,” “off the grid.” I’ve leaned into that myself, especially when the pace and noise of tech start to feel overwhelming.

It’s also why I’ve been skeptical of the growing push to use technology in

environmental work. I’ve worried that it creates more distance, not less— that it adds layers between us and the living systems we’re supposed to be protecting. And in the back of my mind, I’ve often wondered: can we really justify using energy-intensive, resource-heavy digital tools to help the planet?

That’s why Dr. Nadina Galle’s work struck such a chord with me. Her book, The Nature of Our Cities, challenged my thinking in the best

possible way. She doesn’t ignore the tensions or trade-offs between tech and ecology—she names them. But she also asks: what might be possible if we used our tools in service of ecosystems, not in spite of them?

Dr. Galle, an ecological engineer, is the creator of the “Internet of Nature,” a term she coined to describe a growing field of technologybased tools designed to understand, monitor and support urban nature. That might sound abstract, but the

examples are grounded and real— like drones that map heat stress in tree canopies, sensors that monitor soil moisture, or apps that let you “adopt” a pollinator patch and contribute to citizen science while walking your dog.

What ties these tools together is not just technology—it’s connection. Not just data connection, but human connection. These systems help people leap over logistical hurdles—distance, funding, time—and take small but meaningful actions that add up. In that sense, technology becomes a tool not just for measurement, but for care.

“In the Internet of Nature,” Dr. Galle told me, “I focus on emerging technologies—sensors, big data, AI, robotics—that help us map, monitor and manage urban nature, while also helping people reconnect with it.” But she also stresses that these tools don’t stand alone. Many are inspired by or rooted in traditional knowledge systems. “It’s not about replacing those traditions,” she said, referencing the BurnBot, a robot modeled after Indigenous cultural burning practices. “It’s about scaling their wisdom with care.”

And crucially, she adds, not all tech needs to be high-tech. “Sometimes I highlight analog tools—like giving trees email addresses—not because they’re advanced, but because they’re emotionally resonant.”

That sense of emotional connection runs through her work. When I asked what first drew her to this intersection of ecology and technology, she told me: “I grew up in a typical Canadian suburb—people over here, nature over there. Subdivisions paved in, ecosystems cleared, and then given names like ‘Meadow Grove,’ as if naming could replace what was lost. People are wired for nature—but we’ve forgotten how to listen. I began asking: what tools could help us remember?”

What continues to motivate her are the small, local examples where that remembering is already underway: a student logging insect sightings, a city

arborist using sensors to care for trees, a community planting a native forest and sharing its story online. “These aren’t just technical feats,” she said. “They’re emotional shifts. That’s the real engine behind my work.”

Of course, many people still feel overwhelmed by the scale of environmental challenges—or skeptical of technology’s role in addressing them. “I understand that feeling deeply,” she told me. “But I always say, start small. Start close to home.” Whether it’s counting birds in your yard, joining a nature walk, or simply sitting under the same tree each week, she sees these as the real entry points to change. “You don’t need to be an expert—just observant, curious, and willing to engage. If you care, you’re already part of it.”

Her vision is grounded, but hopeful. She’s not advocating blind optimism—just thoughtful integration. And to me, that’s the most refreshing part of her message. It doesn’t ask us to abandon the analog world many of us love, nor does it ignore the urgency of innovation. It asks us to bring them together with care. To think of technology not as a barrier, but as a bridge. To use it to connect—community to community, person to place, data to action.

In a world where climate change, biodiversity loss and eco-anxiety can feel like impossibly big problems, Dr. Galle’s message is simple: connection is still one of our most powerful tools. Whether we’re planting trees, monitoring soil, or walking through the ravine with fresh eyes, that connection is something we can grow.

2025 AT TBG FRIDAY, NOVEMBER

Toronto Botanical Garden and Park People invite you to attend a day of learning, connection and collaboration during the Urban Ravine Summit on Friday, November 7. This one-day event brings together community members, practitioners and city-builders to explore the future of Toronto’s ravines—our city’s vital green arteries—and how we can care for them through stronger connections. Programming will include a keynote address, a moderated discussion with local partners and a variety of breakout sessions and hands-on workshops. We’re excited to welcome Dr. Nadina Galle as this year’s keynote speaker. An ecological engineer and creator of the Internet of Nature, Dr. Galle will share stories, tools and insights that explore how emerging technologies, used thoughtfully, can help deepen our relationship with the natural world woven through our cities.

By Emma Worley Marketing & Audience Engagement Coordinator

THIS FALL, the TBG Garden Shop will feature a curated selection of sustainable, nature-inspired goods from local artisans and makers. Discover thoughtfully crafted products, including jewelry, prints and other small-format works created by talented local artists—perfect for bringing a piece of the garden into your home.

Pictured are a pair of sterling silver earrings from Cecile Reichert, the designer/innovator behind the Bead Stackers Collection. This innovative line allows users to modify their earrings with interchangeable beads. Cecile, who has been creating jewelry since the early 90s, describes her process: “I’m a thinker/dreamer. A lot of my ideas come in the middle of the night. I love simplicity, not to mention functionality, and that’s what Bead Stackers is all about. Can’t imagine doing anything else. I love what I do.”

Cecile works and lives in Brockville, Ontario, where the beauty of the St. Lawrence River gives peace of mind and inspiration.

◗ EMILY ARMSTRONG

Development Associate, Sponsorship and Philanthropy brings a strong background in community engagement and a commitment to expanding public access to high-quality green spaces. With a degree in Environmental Chemistry, she combines strong analytical and research skills with a passion for plant and wildlife conservation. Her recent work in London, England focused on advancing green

JORGE VARGAS-LUJAN

infrastructure projects and leading volunteer and educational initiatives to promote the importance of urban natural spaces. Emily has experience in donor relations, event management and strategic fundraising, and is eager to grow the mid-to-major level donations and grant opportunities at TBG. Deeply aligned with TBG’s mission to foster resilient and inclusive communities, Emily is excited to apply her skills to support the organization’s work across all teams and con-

tribute meaningfully to its continued growth and impact.

◗ JORGE VARGAS-LUJAN Facility Lead/Supervisor

Jorge Vargas-Lujan brings a combination of technical knowledge and operational experience to his new role. A recent graduate from York University with a Bachelor’s degree in Information Technology, Jorge previously worked as a business analyst at Enbridge Gas and has supported building operations in both faith-based and nonprofit settings. His background in process improvement, facilities management, and data-driven decision-making equips him to oversee building systems and day-to-day operations with clarity and efficiency. Jorge also works closely with other departments to support event logistics and ensure the space remains functional for all. He is passionate about creating safe, efficient and welcoming environments, and is excited to bring that vision to life across the Garden.

THROUGHOUT 2025 AND 2026, TBG is celebrating the 70th anniversary of Rupert Edwards’ visionary gift—his sale of land to Toronto with instructions that it forever remain a free public garden and park.

As the city expanded around him, Edwards recognized the urgent need to preserve green space for future generations. His original gift planted the seed for what would eventually become Toronto Botanical Garden. To honor his legacy, TBG launched the Celebration

70 Fundraising Campaign this past summer. The campaign has already raised $19,166.55 and it’s not too late to join the Campaign.

We invite you to give to the Garden you love—just as he once did. Plus, donations are being doubled thanks to a generous donor who is matching contributions up to $20,000! It’s not too late to make your gift! Give your gift to the Garden you love at https://torontobotanicalgarden.ca/ donate-today/

By Svetlana Gorgievski

THE DON MILLS community is no stranger to me. My teenagehood consisted of flitting between my beloved high school, Don Mills Collegiate, the 54 Lawrence E. Bus and the Toronto Public Library, where I spent many mornings, afternoons and late nights.

I remember vividly a hot and humid June afternoon where I first found myself among the lush greenery of the Toronto Botanical Garden. In the months that followed, I spent my school-day lunches weaving between radiant floral beds and one of the most architecturally stunning buildings I’ve ever laid eyes on— unaware that, two years from then, I would be writing this article inside the very building I stood admiring.

TBG’s physical beauty and tranquil presence is an incredible gift to the community. The Garden turns 70 years old this year— that’s seven decades of community builders and plant lovers giving back! Knowing this has lent even greater significance to my teenage memories, from one rich in familiarity and nostalgia, to a new awareness of the Garden’s decadeslong social and environmental impact.

I learned a lot this summer. There is one fact that stood out—that the spirit of philanthropy is embedded deep within TBG’s foundation, and it

began the moment Rupert Edwards sold his land to Metro Toronto Parks for preservation purposes in 1955. His original gift safeguarded a vision for the property to always remain free, as “a place in the country…. with wide open spaces all around, with plenty of room to move and breathe.”

When Edwards Gardens opened in 1956, The Garden Club of Toronto (and later Milne House Garden Club founded in 1967) devoted significant time and money to creating an infrastructure that would share horticultural information with city goers, breathing even greater life into this massive civic project.

One of my favourite internship projects was a deep dive into past editions of Trellis , compiling clippings of memorable headlines and poignant articles that juxtapose our beginnings with our present. The Garden has evolved almost unrecognizably from the first edition of Trellis in 1974. I thought I was reading the wrong article after seeing the TBG referred to as the ‘Civic Garden Centre.’ Studying these past issues helped me witness the growth of the Garden from 1974 until now.

Donations helped erect buildings that continue to serve today’s community—creating a user-friendly horti-

cultural library, increasing the number of education and children’s programs, and stimulating a greater number of learning-based green spaces within the Garden. For example, I wrote this article from an office in the original building designed by the late Japanese Canadian architect Raymond Moriyama, who designed his most iconic buildings based on principles of civic inclusion.

Even the Gardens themselves are an ode to accessibility. Contemporary green spaces mirror the various types of gardens cultivated by Torontonians in space-limited, urban environments, making gardening an activity for all. Since arriving at TBG, I’ve been mentored by great minds, field experts, and the most down-to-earth (literally) staff ever. I learned more about public gardens and giving back than I ever thought I would—most of all, through example. You don’t have to read an essay to learn that TBG’s priority is the community. Come and see it for yourself—there is always something waiting for you in the garden, just like there was for me.

Svetlana Gorgievski is a second-year student at McMaster University, majoring in Environmental Studies and Political Science. She joined the TBG as a Guest Services Intern this summer.

Thank you to TD Bank Group for funding education at the TBG

LIVING WINTER IS A FULL-DAY experimental learning program for students from high-needs communities in Toronto. The free program aims to integrate hands-on outdoor learning with the Grade 4 curriculum (Habitats and Communities), introduces students to outdoor learning about nature, and empowers them to connect with and protect the environment.

Living Winter focuses on teaching students to be stewards of their environment, creating excitement about local ecosystems, and promoting responsibility in their communities.

“Time in nature instills wonder and awe in our natural world”, says Stephanie Jutila, CEO of Toronto Botanical Garden. “We are grateful for support in offering the Living Winter program free of charge to Toronto schools that may not have ready access to nature. “This funding support is not in a program alone, but also in helping TBG promote a positive connection between students and nature here and in our local communities”

THE HEARTS & FLOWERS Campaign is Toronto Botanical Garden’s largest annual fundraising effort. Once a year we pause, reflect, and take in the full scope of what the Garden gives back—to people, to the planet and to Mother Nature.

TBG is more than a Garden. It’s a love letter to Toronto—to its people, plants, pollinators, and even the curious critters who drop by for snacks.

It’s also a love letter to the community that nurtures it and that means you!

Strong communities grow together. They care, learn and celebrate together. And they plant seeds for the future, together.

In 2025, our Hearts & Flowers fundraising goal is bold: $300,000 to fund a year of free eco-education for kids in need, for sustainable horticulture, inclusive events and so much more.

This year, we’ll invite you to share your love letter to TBG. What will your love letter say? Follow the trail of letters in your email inbox and on social media. Hearts & Flowers launches this November.

–Melanie Lovering,

Director of Development

Interns bring fresh enthusiasm to the Garden By Sasan

IJOINED TBG in June of 2020, the spring of covid, when the world was locked down and most people were without work. I was grateful that gardening was deemed safe and essential—and even more so grateful that there was enough funding during that turbulent time to hire a second seasonal gardener... me.

The garden had lots of visitors that year, but our beautiful building was closed. There were no classes in the studios, no weddings in the Floral Hall. I remember hanging out in the empty library and seeing postings of past programspoetry readings, forest bathing, nature camps...

Back then, we had a couple of tropical plants in the building—two Ficus Benjamina ... it took about three minutes to water them both with a can.

Our visitor’s centre looks a little different now. This year,

every department at TBG bloomed with new summer faces, interns joining us for the season. I like to remind my colleagues, maybe a little too often, that there were only two of us here when I started. Now, you’re lucky if you find an empty seat in the staff lounge come lunch time.

As a gardener, I’m all too familiar with watching things grow, watching them change and adapt. It takes lots of patience, sure, to grow a dream from a handful of seeds. But when communities come together, the waiting becomes easier, the heaviness of our days becomes light when we dream and look forward together.

Thanks to the Canada Summer Jobs Program, this year we were able to recruit five summer interns—two for education, two for horticulture, and one for marketing and audience engagement. Not to mention the camp councillors

Rob Oliphant, MP of Don Valley West came to the Garden on Friday, July 18 to meet the Canada Summer Jobs Students to see how they are gaining work experience by leading guided tours, marketing initiatives, educational programs and day camps.

“This experience connects directly to what I study”

WHEN I FIRST started as a Horticulture Intern at the Toronto Botanical Garden, I thought most of my time would be spent watering plants and pulling weeds. I do a lot of that, but what I didn’t expect was how much I would end up learning every single day. For me, this experience connects directly to what I study. I’m Jackleen, a third-year Conservation and Biodiversity student at the University of Toronto.

• WORKING AT THE GARDENS has brought so much of what I’ve learned in class to life. Being out here is completely different from sitting in a lecture hall. Getting to apply my knowledge and actually see it happening in front of me is something I could never get from a textbook.

• TAKING CARE OF PLANTS has shown me how they fit into the bigger picture of an ecosystem. It’s not just about the plants. It’s about all the animals they support. Every day I see life around me, from bees and butterflies to birds, rabbits, groundhogs, and even minks.Honestly, one of the best parts is seeing the baby animals throughout the summer. It’s a constant reminder of how important these green spaces are in the middle of the city.

• WHAT REALLY STOOD OUT to me is the community here. The volunteers are amazing. So many of them have been coming here for years just so they have the chance to garden. They bring a level of care, experience, and passion that you can really feel in the work they do. They’re not just helping out, they’re fully part of what keeps the gardens thriving, and I’ve been lucky to learn from them.

• THIS INTERNSHIP HAS GIVEN me the chance to be part of something much bigger than I expected. I’ve grown my skills, deepened my understanding of biodiversity and met people who are just as passionate about these spaces as I am.

—Jackleen Katz, Summer Intern

in their TBG green tees sprouting all through the garden. I see their excitement and enthusiasm about working here and it takes me back to when I first entered this field, almost 10 years ago now. But enough about me and my old-man nostalgia. Here’s what our Horticulture intern, Jackleen (Jackie) has to say about her time at TBG.

• TBG 2025 SUMMER STUDENT INTERNS • Darwyn Chang, Avery DeMarco, Scott Gillespie, Svetlana Gorgievski, Kate Hennessey, Jackleen Katz, Jenna Kozlowski, Emma Marini, Julia Murphy, Nastasia Pappas-Kemps, Claire Timmins, Ella Woods. Ellen Kessler is a volunteer and seasonal summer staff member.

By Nastasia Pappas-Kemps Marketing and Audience Engagement Assistant

I’M ASHAMED

my thumb is more brown and shrivelled, than green. And it’s with this shame that I arrived in Hoggs Hollow for my first garden tour, feeling like an impostor.

Each homeowner was nervous as we entered. I have little reference to the vulnerabilities of sharing one’s garden, so I liken it to a filmmaker’s first screening or a painter at a gallery opening. One homeowner was shy about the stunning forget-me-nots pushing through cracks in the pavement and bleeding hearts weeping from her fence. I lost a friend whose headstone in PEI is littered with both and they reminded me of him.

Next door, a mourning dove kept cooing at us from its perch in a thriving dogwood. I was grateful for the imperfection—a reminder of the hours of work that go unseen in the soil. I didn’t mind the mulch.

The sheer size of some gardens enraptured me and one endeared me to it with a cherub fountain plopped in the middle of a manicured lawn. The large pink peonies there were so striking, I had to stop myself from touching every petal.

This is before the event even began, mind you, as the Toronto Botanical Garden team puttered from house to house taking videos and preparing for the weekend to come.

Which is why it was a huge relief when, on the Saturday, I was overjoyed to see just how many garden-lovers enjoyed themselves. On the bus, I heard my own excitement over the fortuitous weather and the proximity to the babbling ravine echoed by many eager explorers.

I went to find my good friends Deanna Petcoff and Claire Hunter who had parked themselves at one house overlooking the river to play music. I have heard both their music time and again but, in this setting, it held something entirely new. I watched a young girl and her father share a little slow dance. With the way the water echoed lyrics back to us, I could understand their urge.

I also spent a lot of my time studying the excited chatter between horticulturist Sasan Beni and TBG summer horticulture intern Jackie. The way Beni ruffled each plant like you would a beloved pet and gently chastised invasive species, it became clear to me that there is ineffable magic to it all.

His giddiness was especially evident when we arrived at one particular house, and for good reason.

To hear this homeowner tell it, luck and good weather are to blame for her garden’s success. But one look at the explosive ferns, winding wisteria and squirrel-planted walnut saplings, anyone can see she simply loves it. And in response, it loves her back.

This week I was given a new canna lily. I left it in the sun and upon my return home planted it between some resilient irises a past resident left behind, inspired to one day be as bashful and loving when inviting others through my own garden gate.

By Lee Robbins Weston Family Library Manager

IHAVE BEEN the Weston Family Library Manager since July of 2024, although I have been volunteering and working in the Library since Summer 2022. Earlier this year, my colleagues and I decided to reorganize the library’s workroom and an unused office used for storage. The office turned out to contain a treasure trove of historical material from Rupert Edwards’ estate

(e.g.,maps, photos, newspaper clippings and documents), the donation of the property to the City in 1955 and the start of the Civic Garden Centre (CGC) and the creation of the Toronto Botanical Garden (TBG). I had an epiphany that this material could be used to create a great display that would highlight and celebrate the 70 years of growth and development of the garden through its architectural history.

Putting the display together became a real research project, investigating the history of the garden, buildings and architects that showed the progress of the CGC/TBG. I ended up contacting the Archives at Toronto Metropolitan University, the University of Alberta, and the University of Toronto for information about the architects.

One unexpected and exciting discovery was finding a painting by

W.R. Teddiman of the golf course that Rupert Edwards had commissioned in 1947. This 9-hole golf course was designed by Stanley Thompson, who designed many award-winning golf courses in the early twentieth century and was a co-founder of the American Society of Golf Course Architects. Teddiman was a draftsperson for the prominent Toronto Landscape Architecture firm Wilson, Bunnell and Borgstrom contemporaneous with Thompson, which I only found out after corresponding with the Stanley Thompson Society’s executive director. Many of Thompson’s blueprint plans were drawn by Teddiman.

The painting was in a very fragile state: brittle paper, water marks, small holes and tears and framed with cheap cardboard backing. I spent some time finding one of the best conservators in Toronto who over a few weeks restored and repaired the painting and reframed it in a quality frame.

Another exciting discovery in the archival material was the original typewritten speech that Rupert Edwards gave in 1956 at the official donation ceremony of the lands that would form Edwards’ Gardens.

I spent many weeks putting together photographs and other material and creating the narrative that went with each item to tell the architectural story of the various buildings that were to become the TBG we know today. With the help of various staff and volunteers this display came together on the back wall of the library, above the children’s book collection.

The display starts with aerial photos from 1949 showing Rupert Edwards’ property surrounded by farm lands, the home, barn, glass houses and rock garden easily identifiable. Lawrence Avenue East appears to be a rural, single lane road.

Milne House, original to the property, that contained the holdings of the Civic Garden Centre, burned down in 1962. To encourage public use of

Edwards Gardens, Metro Parks contracted architect Raymond Moriyama in 1963 to build a pavilion on the foundations of Milne House. Moriyama incorporated the original foundations and terraces of Milne House into the pavilion’s design.

His design trademark of using natural materials and the enthusiastic public reaction to his pavilion made him an obvious choice as the architect to be considered for the new Civic Garden Centre, which opened in 1964.

Raymond Moriyama (1929-2023) designed many iconic buildings, including the Canadian War Museum, Ottawa’s City Hall, Bata Shoe Museum, Toronto Reference

Library, the Ontario Science Centre and the Canadian Embassy in Tokyo, to name only a few. He was recognized with several prestigious awards such as the Confederation of Canada Medal and the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada Gold Medal. In 2008, he was bestowed with the highest honour of the Order of Canada.

An addition to the east side of the Moriyama building was designed by architect Jerome Markson and opened in 1976.

Jerome Markson’s (1923-2023) architectural and urban works won more than 50 design awards over the course of his career. He received the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada (RAIC) Gold Medal in 2022, the highest honour the Institute can bestow in recognition of a significant and lasting contribution to Canadian architecture.

The newest portion of the Civic Garden Centre, the George and Kathy Dembroski Centre for Horticulture, was completed in 2005 by Montgomery Sisam Architects (founded in 1978). Their addition to the TBG design received many awards.

Montgomery Sisam has developed a reputation for design leadership

that is supported by over 80 provincial, national and international design awards.

The history of the TBG is not finished as there are many future expansion plans already underway in collaboration with the City, as well as ambitious capital projects to expand its education, horticultural displays and conservation.

I really enjoyed working on this project and learned a lot about the Garden’s history while putting the display together. Hopefully you will, too, when you come to view the display in the library.

◗ Archaeological & Cultural Heritage Services, Heritage Impact and Cultural Landscape Assessment prepared for the City of Toronto, Parks Development/Capital Projects (2017) ◗ The Garden Club of Toronto, ed. Elizabeth M. Bryce, A History of the Civic Garden Centre: The Civic Garden Centre in Metropolitan Toronto 1958-1997 (1997).

By Natalie Harder Director of Learning

WHAT BEGAN as a centrepiece-making class has grown into a popular workshop, now offering both afternoon and evening sessions and an expanded selection of projects like wreaths and swags.

But this event is about more than crafting beautiful décor—it’s about supporting future nature lovers. Proceeds from the workshop fund children’s educational programs at TBG, a cause the club embraced because they wanted to support something meaningful and visible. “We see the children coming and going for programs like Living Winter,” says a club representative. “Connecting with kids felt natural for us—many of our members are former educators, and it’s a way to spark a love of nature that lasts a lifetime.”

The workshop itself is full of holiday spirit. Guests are welcomed by the fragrance of fresh greenery, homemade cookies and warm apple cider. The atmosphere is friendly with lots of one-on-one support to make sure everyone leaves feeling proud of their creation. “There’s no right or wrong way,” says Michael Erdman. “It’s about enjoying the process and learning something new.” Sustainability is also at the heart of the event—materials are natural, and even leftover greenery finds new life as decorations throughout the Garden.

This year’s workshop will feature a totally new design— a modern twist on a holiday classic, crafted with natural materials. As the club puts it: “Thinking outside the vase!”

Don’t miss your chance to be part of this beautiful tradition! Come create something special, enjoy the festive atmosphere, and know that your participation helps bring the joy of nature to children all year long.

Date: December 2 Times: 1 p.m. & 7 p.m. Location: Toronto

Pinecones

Bring a touch of frosted magic to your holiday décor with these simple, nature-inspired ornaments. Perfect for wreaths, swags or centrepieces, these ‘iced’ pinecones are easy to make and add a sparkling winter feel to your home. Follow these steps and get creative!

1. Prep Your Pinecones Start with short, stubby pinecones—white pine cones work beautifully, and the bigger the better! For swags, choose the longer cones.

2. Bake and Open Place pinecones on parchment paper and bake at 250°F for 30 minutes. This helps open the scales, releases sap and clears out seeds and bugs—plus, it prevents mess later!

3. Wire for Crafting Thread a sturdy wire (22-gauge or thicker) through the bottom scales and twist to secure. This makes it easy to attach your pinecones to wreaths, swags or arrangements.

4. Add a Frosty Finish Brush edges with Mod Podge or spray glue, then sprinkle a mix of Epsom salt and glitter for a sparkling, frosted effect. Let dry, and they’re ready to use!

Swing by for a croissant and coffee, relax on the patio with our lunch menu, and cool down on a hot day with icy treats.

Rooted in local goodness, we prioritize Ontario and Canadian-grown ingredients because fresh ingredients taste better and supporting local matters.

Swing by for a croissant and coffee, relax on the patio with our lunch menu, and cool down on a hot day with icy treats.

Guillaume Clairet and Dave Stratton open new restaurant in Edwards Gardens

By Lorraine Hunter

Trellis Editor

Rooted in local goodness, we prioritize Ontario and Canadian-grown ingredients because fresh ingredients taste better supporting local matters.

prioritize ingredients better and matters.

JUST TWO MONTHS after the opening of the Dandelion Café, proprietors Guillaume Clairet and Dave Stratton were pleasantly surprised to find that they were much busier than expected.

Partners in the catering firm Daniel et Daniel, as well as brothers-in-law, the two men jumped at the chance to take over the café housed in the old barn in Edwards Gardens when it became available last spring.

“As a longtime event caterer for the TBG we welcomed the opportunity to work with them,” said Dave. “We opened with a quick turnaround in May, learning as we went. Traffic patterns began to emerge and we have been learning all summer.”

They named it the Dandelion Café, said Guillaume, “because wild plants deserve more than just being perceived as weeds. We want to celebrate the value of dandelions rather than spraying them down.”

Growing up in the countryside, Guillaume remembers dandelion picking with his family. His mother would use the leaves for salads and the roots in tea. “My dad made dandelion wine with the flowers. We did regular foraging for things growing around us.”

Dandelions are herbs. Their leaves, roots, seeds and flowers are said to offer health benefits, such as improving liver function, fighting inflammation and managing blood sugar levels. The café serves Dandelion tea, salads and other dishes.

Guillaume’s father Daniel founded the catering business with fellow Parisienne Daniel Megly in 1980, “and we bought him out when he was ready to retire,” said Dave.

“Catering is our bread and butter,” he said. “And we also own a food shop

at Carlton and Parliament downtown that does really well, selling freshly baked goods with a larger menu than the Dandelion.”

The Dandelion Café is a popular spot in the Garden where the most frequently ordered items besides coffee, are paninis, sandwiches and ice cream. Thursday evenings during July and August, when the outdoor Edwards Foundation Summer Music Series took place literally right outside their door, were especially busy. Serving complete grilled salmon, chicken brochette and steak dinners as well as pizzas, “the staff loved doing the barbecue and making the pizza.”

“We both attended the concerts,” said Guillaume. “It was a great chance to get out of the office.”

“Week One everyone wanted chicken brochettes so we prepared more for Week Two,” said Dave. “But in Week Two everyone wanted salmon and we ran out. For Week Three it was steak. I think the regulars were trying something different every week.”

The partners have increased the amount of indoor seating at the café and are featuring on-sale works of local artists and photographers on their walls.

For groups visiting the TBG or Edwards Gardens, the café will prepare boxed lunches and keep them cool until lunchtime. “It’s convenient for the customers and for our staff during the busy lunch hour,” said Dave. But you have to reserve a few days ahead.

“We are excited about this new venture,” said Guillaume, “reconnecting society with nature.”

“It’s a nice connection to gardening,” added Dave. “Guillaume’s dad and our executive chef Karen are both avid gardeners.”

• 2 oz fresh dandelion greens-roughly 2 loosely packed cups harvested before the flowers form

• 3 oz bacon (2 slices) cut into 1 inch slices

• 1 tbps balsamic vinegar

• 1 small clove of garlic minced (optional)

• 2 large fried or hardboiled eggs optional

• Shavings of fresh high quality parmesan cheese such as Parmigiano Reggiano

• Fresh ground black pepper

• ½ tsp maple syrup

• 1 tbsp fresh cut chives

• A few sliced leaves of fresh mint, tarragon or basil (optional)

• 1 dandelion flower to garnish (optional)

Wash, clean, and dry the dandelion greens. Make sure the greens are perfectly dry so they don’t dilute the dressing.

Cut the greens into 1-2 inch pieces. If using cultivated dandelions, remove most of the stem so you have mostly the leafy upper portion.

In a stainless steel saute pan or cast iron skillet, heat the bacon over medium heat, stirring occasionally, until crisp and the fat has rendered out.

Drain off most of the fat, leaving about 2-3 tsp in the pan.

Remove pan from the heat, and, while it’s still very hot, add the vinegar and stir quickly with a wooden spoon to remove the browned bits.

Immediately pour the hot baconvinegar mixture onto the dandelion leaves and mix well, adding the maple syrup and herbs.

Garnish with the fried or boiled eggs.

Taste the salad and adjust the seasoning for salt, pepper and acid. A dash of fresh squeezed lemon juice (½ tsp) can be nice at the end.

Transition your containers from summer to fall by changing out plants and colours

By Wendy Downing

AS WE HEAD into September, those gorgeous planters and urns we prepared in the spring are starting to look tired—a little bedraggled with plants looking for help to perk them up.

We all enjoyed the vibrant, hot colours of summer, but with cooler weather on the horizon we start to look inward as we prepare for fall and winter. Were you smart enough to think ahead with your spring planting and include structural elements in your containers? This one simple thing can make transitioning from one season to the next a little smoother. Whether you have used dracaena spikes, ornamental grasses or evergreens as the centre element of your design, these staples of the garden give us a good place to start.

Bronze dracaena spikes lend that wonderful deep colour that sets off the brighter hues of spring and summer and then acts as a foil against the rich colours of autumn. Take a trip to your local nursery and walk up and

USING A BRONZE DRACAENA spike as your central element, add white, orange or apricot chrysanthemums; golden, orange, or green cockscomb celosia, blue or purple asters, decorative kale and gourds in tones that enhance the flowering plants. Plant something vining to spill over the edge of the container. A number of ivies are now considered invasive in many parts of the county, but if you can use them, they do an excellent job of masking the line between the container and the plant material. Add a grouping of gourds or different pumpkins at the base of the urn to help ground it and draw your eye throughout the design. If you have chosen grasses as your vertical element, choose your accent and filler plants to harmonize with the colour of the grass. Purple fountain grass for instance, looks great with blue-grey foliage such as lamb’s ears (Stachys), hosta, heuchera, dusty miller, blue salvia, purple chrysanthemums or asters together with an accent of yellow or orange using either gourds or rudbeckia.

down the rows. You will be surprised to find a vast number of plants and accessories that lend themselves to designs for fall and help to prepare us for the colder weather ahead. Look to decorative planters at public parks and gardens for inspiration. The gorgeous colours of chrysanthemums and asters juxtaposed with the accents of grasses and vining plants that tumble over the edge of the container create good visual interest. Be sure to check out the non-flowering plants as well—kale, hosta and other foliage plants help round out the overall appearance of your container by adding contrast in colour and texture. Closer to Thanksgiving you can add pumpkins and other gourds to the mix for something smooth and eye-catching. And, in case you haven’t noticed, pumpkins now come in a variety of colours from white to grey,

orange to smoky green, from smooth and shiny to wrinkled and warty.

If you used evergreens as the focus, remove the annuals from the fall planting, plant the perennials into the garden to enjoy next season, and turn your imagination to thoughts of the upcoming holidays. With the addition of glossy leafed branches such as holly or mahonia along with trimmings from your cedar hedge, yew and pine, you have the start of an interesting winter arrangement. Add branches of red twigged dogwood, curly willow or contorted hazel for height and you have transitioned to a design for the winter season. As December approaches, think about whatever holiday you celebrate, add things that personalize your design and help to make it your own. Feel free to fill out your design with additional branches of greens. Make sure

1. Start with a clean container.

2. Add some drainage material to the bottom.

3. If possible, add fresh soil or soilless mix and a handful of slow-release fertilizer.

4. Consider the plants. You want something tall to help form the line of the design; something trailing to bring your eye through and mask the edge of the pot; and fillers for colour, contrast and texture.

5. The proportion of plant material to container should be two parts plants to one part container.

6. Put some of the colours used at the front in the back of the design to create depth

7. Be sure to add something like fall gourds or pumpkins to continue the line and rhythm of the overall planter.

8. Water and enjoy.

to water the container well and the branches will freeze into the container and keep reasonably well until after Valentine’s Day when you can turn your thoughts to the delightful spring flowering bulbs, pussy willow and other plants which are the harbingers of spring.

Give your imagination free rein and see what wonderful plant combinations you can make to bring life to your planters and a feeling of welcome to your guests as they come to your door.

Regardless of where you live in Canada, you should be able to find plants that will survive in your area. Savour the feelings that come from working with plants and flowers and know that your efforts will be enjoyed not only by your friends and family but also by your neighbours and passersby.

Savour the feelings that come from working with plants and flowers and know that your efforts will be enjoyed

By Veronica Sliva

AS FALL approaches, our attention turns to the many garden tasks that cooler temperatures bring. One of them is to get the houseplants back indoors. When to bring them in is a question many gardeners wonder about. And that depends on the weather, of course. Because most of our houseplants are tropical, bringing them in before the temperature drops and the nights turn cold is recommended, allowing them to acclimate indoors with less stress.

Many of us live on the edge, leaving this task too late, ending up with damaged or dead plants. On the other hand, some plants are quite happy to be left to chill down a little longer than most. It’s good to know the difference. I remember discussing this many years ago with the late Larry Hodgson, one of Canada’s best-known and prolific horticultural writers. You may be familiar with his blog, The Laidback Gardener. (Though Larry passed away in 2022, his son Mathieu still maintains the blog at https:// laidbackgardener.blog/. It’s a wealth of information worth checking out.)

Larry explained that most houseplants are tropical and do not like the gradual cooling of autumn nights. They adjust better to the indoor environment when they are brought inside while the outdoor temperature is still relatively warm.

He pointed out, however, that a small group of the houseplants we grow are not tropical in origin at all, but rather subtropical. In their native environment, they do experience cool temperatures for part of the year (but not frost), and these are the houseplants that enjoy the cooler temperatures of fall. We can leave them outdoors longer than you might think.

Plants that like it cool… really cool

CYMBIDIUM ORCHIDS (Cymbidium spp.): Cymbids can thrive outdoors and benefit from cooler temperatures. In fact, they

bloom best after a cold spell. Unlike typical tropical houseplants, cymbidiums like to spend the fall outdoors. Theoretically, they tolerate temperatures as low as 1°C (34°F). However, Larry pointed out that it is safer not to subject them to temperatures quite that low. Instead, bring them in when the night temperature begins to regularly dip below 7°C (45 °F). Once indoors, keep them in a cool spot, at about 10° to 15°C (50 to 60°F) until spring returns. This mimics the ‘winter’ they would have in their native environment. You should be rewarded with blooms.

CHRISTMAS CACTUS

(Schlumbergera hybrids): Left outdoors until nighttime temperatures drop to from 4°C to 10°C (40°F to 50°F), this group of plants will reliably reward you with a froth of blooms not long after you bring them in. Mine sometimes start showing buds a few days after they are brought back inside. Very easy and satisfying!

AZALEA (Rhododendron hybrids): Have you wondered why the azalea you were given during the holiday season didn’t rebloom? I always found this frustrating and rather than try, I just sent the plant to the compost pile. The reason these ‘florist’ azaleas don’t rebloom is that they have not had a cold spell. They need about six weeks of temperatures from 4°C to 10°C (40°F to 50°F) to set buds. So, you can leave them outside longer than you might think and will likely get a flush of bloom.

CITRUS: Citrus (like lemons, limes, oranges, etc.), make good houseplants

given the right conditions. When they bloom indoors, they fill the house with the intoxicating scent of the tropics. Citruses are happy between 13°C and 29°C (55°F to 85°F), but a variation of 10 degrees encourages blooming (not frost though). I always set mine outside for the summer, where they

put on lots of new growth. They are the last to come indoors when fall arrives and eventually that pleasant scent drifts through the house.

Agapanthus Lilly

THIS IS A SHORT LIST that includes some plants that tolerate cooler temperatures in the fall and can be left outside longer than the more tender ones can. However, if you decide to bring them indoors at the same time as their tropical companions, they don’t mind that either.

Note: This list is not comprehensive. If you are wondering about a plant not on the list, rather than risk losing a beloved houseplant to the elements, an internet search may be in order!

• Agave (Agave spp.)

• Aloe (Aloe spp.)

• Aspidistra or cast-iron plant (Aspidistra elatior)

• Bottlebrush (Callistemon spp.)

• Buddhist Pine (Podocarpus macrophyllus)

• Common ivy (Hedera helix)

• Cordyline or spike dracaena (Cordyline australis)

• Crassula or jade plant (Crassula obtusa and others)

• Dwarf pomegranate (Punica granatum ‘Nana’)

• Elephant bush (Portulacaria afra)

• Agapanthus or lily of the Nile (Agapanthus spp.)

• Gasteria or ox tongue (Gasteria spp.)

• Golden cypress (Hesperocyparis macrocarpa, syn. Cupressus macrocarpa)

• Holly osmanthus (Osmanthus heterophyllus)

• Japanese aralia (Fatsia japonica)

• Lady palm (Rhapis excelsa)

• Miniature rose (Rosa cvs)

• Oleander (Nerium oleander)

• Calceolaria or pocketbook plant

(Calceolaria × herbeohybrida)

• Florist’s chrysanthemum (Chrysanthemum morifolium)

• Florist’s cineraria (Pericallis × hybrida, formerly Cineraria × hybrida)

• Florist’s cyclamen (Cyclamen persicum)

• Florist’s hydrangea (Hydrangea macrophylla)

• Piggyback plant (Tolmiea menziesii)

• Primrose (Primula spp.)

• Strawberry saxifrage (Saxifraga stolonifera)

• Venus flytrap (Dionaea muscipula)

• Voodoo lily (Typhonium venosum, syn. Sauromatum guttatum)

• Wire vine (Muehlenbeckia spp.)

• Yucca (Yucca spp., some species)

Join a dynamic community of plant people and access special benefits including:

Free parking at the Garden

10% off classes & workshops

10% off at the Garden Shop & Dandelion Café

10% off children & family programs (Tree level+)

Access to presale tickets on select events

Reciprocal benefits at 330+ other gardens

Weston Family Library privileges… and more!

Digital Membership Cards

For more information and to join: torontobotanicalgarden.ca/member

By Megan Blacquiere Seasonal Horticulturist

Photography By Ross MacDonald and Sasan Beni

WHITE-TAILED deer are the most numerous and widely distributed large animal in North America. These animals predate the ice ages and are the oldest existing deer species. They are found in southern Canada, from British Columbia to Nova Scotia, and in most of the United States, except for parts of the Southwest, Alaska and Hawaii. There are also populations in Central America, including Panama and southward to Bolivia. In the summer, they can be found in a diverse range of habitats, including forests, woodlands, shrubby areas, grasslands and

agricultural fields, where they have an abundance of food. They prefer areas containing dense thickets and edge habitats, with access to water, vegetation and protective cover from predators and harsh weather. Most typically live as solitary individuals in summer, but many form herds in winter where they populate ‘deer yards’, trampling down snow in

THESE DEER ARE most easily identified by the pure white under their tails and around their rumps, with their signature ‘flag’ appearance when their tail is raised. In spring and summer, their fur pattern is reddish on their back and sides, with a whiteish tone underneath. In fall and winter, the reddish colouring turns to a greyish hue. Full-grown males can reach up to 2.5 to 3.5 feet tall at shoulder height, and 5 to 6.5 feet in length, weighing anywhere from 150 to 300 pounds. Males have forward-curving antlers with numerous unbranched tines, which they shed in late December to February and regrow every season starting in late March or early April. White-tailed deer can be confused with black-tailed deer. Both species have similar antlers and white under the tail, but black-tailed deer inhabit only from Coastal British Columbia to Vancouver Island, where the occurrence of white-tailed deer is rare.

areas that provide food and shelter from storms and deep snow. Suitable areas include coniferous forests or south or southwest-facing slopes with more sunlight.

WHITE-TAILED DEER are crepuscular herbivores, feeding in early morning until dawn and late afternoon until dusk, consuming a diet of plants. They are also ruminant mammals, meaning they have a four-chambered stomach for digestion. The first two chambers are the rumen and the reticulum, where the cud is formed when food is mixed with bile. After the cud is regurgitated, re-chewed, and swallowed, it passes from the rumen to the omasum chamber, where water is removed. It then enters the final chamber, the abomasum, and travels to the small intestine for nutrient absorption. This system allows the digestion of the roughage of their diet, consisting of leaves, twigs, fruits, nuts, lichens and fungi. Their diet changes seasonally. They eat green plants in spring and summer. In fall, they enjoy corn, acorns and nuts. In winter, they feed off woody plants, eating the buds and twigs.

MATING BEGINS in November in the north and January or February in the south. The shortening of daylight hours brings hormonal changes in female does and male bucks. To attract a mate, bucks will partake in rituals such as sparring with their antlers, antler rubbing on trees and scraping on the ground to assert dominance. Once successfully mated, the gestation period lasts approximately 200 days, with females giving birth to one to three fawns. The babies can walk upon birth and forage after a few days. Mothers leave their young well-hidden and unattended for hours due to the safety of their camouflage and the fact that they are nearly scentless. At about four weeks old, the fawns can join their mothers on foraging trips. Weaning begins at about 10 weeks. Young females stay with their mothers for two years whereas males leave after one year. These deer can live up to 20 years in the wild, but few will live past 10; the typical average lifespan is two to three years.

AS AN AMATEUR WILDLIFE PHOTOGRAPHER, I’m delighted when I see deer in the city. As a horticulturist at TBG, I shake my fist at them when they trot on the grounds and eat our tulips. We had a deer problem back in the spring. Six had settled at the teaching garden and would make their way through Edwards Gardens, trampling the beds, nibbling on the yew hedges. To solve this problem, we decided to understand them better. Hence, this profile on the white-tailed deer. SASAN BENI, Seasonal Horticulturist

How to protect your garden from urban wildlife

By Leslie Hockley Lead Horticulturist

WHITE-TAILED DEER (Odocoileus virginianus) for most Torontonians are considered cute and mystical creatures. When we stumble upon them in seemingly very urban areas, we often think, “A large wild animal in the city! So cool, wow!” or “Aww, Deer!”

For gardeners however they can be public enemy number one. Often thought of as bottomless pits that will consume all plants in sight, especially when we are trying to make the most of our city oases, they can be devastating. These four-legged creatures are quite adaptable and habitual creatures. Knowing when and how to protect your cherished plants can be vital.

There are three main deer habits that can cause damage to one’s garden: eating/browsing, antler rubbing and bedding (laying down). The most common form of damage a gardener will encounter is likely from browsing where a deer will consume tender buds or lush new growth on plants. Deer can be seen most often browsing gardens from late winter to spring (early summer), when their diets require a much higher nutrient concentration. The variety of plants they’ll eat increases when normal browsing material diminishes (long winter) or from higher deer pressure (high population, urban area, or reduced habitat). A very common topic among gardeners inflicted with browsing deer is how to prevent the problem. There are many products available on the market that are advertised to deter or repel deer:

◗ Mechanical: implements that make noise, flash lights, sprinkle or move— to try and trigger a fear response in the deer.

◗ Sprays: which can contain things such as blood meal, blood byproducts, predator urine, or sulphur. Depending on which product is in the spray, it will trigger a different response in the deer. Blood and urine trigger fear, whereas sulphur (eggs) trick the deer into thinking the plant is unpalatable.

◗ Fencing: there are a few different styles of fencing which can be utilized to keep deer away (e.g. upright, slanted or electrical.) The key is to understand how far and high deer jump. Other strategies include:

◗ Strategic Plantings: employing companion planting techniques by planting unpalatable plants on the outer edges of your yard or around more vulnerable plants.

◗ Owning a dog

◗ Growing plants that have characteristics deer “don’t like”: fuzzy/tough/ leathery/spiny leaves, aromatic, or poisonous. Though the effectiveness of these will directly correlate to the hunger level of the deer.

*Ultimately, the best form of protection is a good defense; if you know there are deer in the area, prior to planting it is recommended to install a fence or plant deer ‘deterrent plants’. It is also recommended to implement several strategies and rotate through them. If you only use one consistently, the deer will eventually learn it isn’t a threat.

BROWSING

At Toronto Botanical Garden we are not immune to the pressures of urban deer populations. With Wilket Creek connecting us to many greenspaces in the City, deer have been known to frequent the property. Due to the way our site is arranged there are a few techniques we are unable to use successfully like large scale fencing (though this is the most effective deer deterrent). In most years if there has been any deer damage it has gone largely unnoticed, so we have not had to implement any strategies.

This past spring for the first time we noticed browsing damage on our tulip displays! If left unchecked this

could have done untold damage to this seasonal display and left the garden without its most prominent display. There were signs of deer hooves in beds and jagged bite marks on the newly emerging leaves.

Since we couldn’t erect tall fences or employ a fleet of guard dogs, we trialed a spray application. We wanted to use the deer’s distaste of eggs against them. So, we mixed a concoction of raw eggs and water (1-2 raw eggs to 1 gallon of water) into a sprayer and applied that directly to the leaves of the tulips. The smell tricks the deer into thinking that whatever plants have this protective coating is inedible and does not taste like a juicy tulip.

Most recipes found in books in the Weston Library, mention that “the mix should be left to ferment or become putrid over the course of a few days.” Which as you can imagine is quite smelly, however once it is diluted into the sprayer the smell is dampened and is only really detectable by deers’ highly sensitive noses. Like many spray applications it is recommended that you reapply after each rainfall or after a few weeks to maintain the potency.

Luckily for us when the deer did their initial browse, they only nipped the leaves because the buds had not emerged yet. With our egg mixture on hand, we were able to dissuade the deer from munching on them further.

Several of these techniques also work on other common urban critters like rabbits (fencing) or squirrels (fencing/caging and/or spraying).

Canada releases new Plant Hardiness Zones By

Carol Gardner

Canada’s new plant hardiness zones have just been released, and what a challenge it has been for the scientists who work for National Resources Canada/ Forestry. The last Canadian update was in 2014, and how the world has changed since then!

Plant hardiness zones tell us which plants are likely to thrive in specific geographical zones. The first USDA zones were compiled in 1927 by a German scientist, Dr. Alfred Rehder, while working at Harvard University’s Arnold Arboretum. Canada’s plant zones were developed by our Department of Agriculture in the 1960s, based on the survival status of 174 woody plants, shrubs and cultivars at 108 test stations across the country. Later on, these zones also encompassed herbaceous perennials. It wasn’t until 2012 that Britain’s Royal Horticultural Society introduced plant zones which would work for their unique climate. Don’t bother checking it out – you’ll just grind your teeth when you see what they’re able to grow!

What I hadn’t realized, to my shame, is how much the American version of zones differs from the Canadian one. The American zones are based on only one factor: the lowest extreme minimum temperature experienced in the different zones over the previous 30 years. That’s the only criterion. The Canadian zones are based on information gathered over the past 30 years ((19912021) for seven variables:

• Average annual minimum temperatures of the coldest month

• Mean maximum snow depth

• Monthly mean of the daily maximum temperatures (°C) of the warmest month

• Amount of rainfall in June through November

• Frost free periods above 0°C

• Amount of rainfall in January

• Maximum wind gust

How do they deal with the potential for climate change? They suspect that the zones will have to be reviewed and changed much more frequently than they were in the past. All that being said, the scientists caution that the zones should be used as guidelines, not hard and fast rules. There are many other variables to consider when deciding when a plant has a chance to flourish –micro-climates, soil composition and elevation to name just a few. So be adventurous – but not crazy! There is a great deal of information about planting zones available on www.planthardiness.gc.ca including planting zones by municipality and zone maps. Here, we’ve given you just a few by local municipalities. Many thanks to Dan McKenney and John Pedlar from Natural Resources Canada for the above information.

November 21 to 23

November 28 to 30

Fri, 2 to 6 p.m. Sat & Sun, 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Admission is FREE

By Georgie Kennedy

PODCASTS ARE the ultimate alternative to doomscrolling: they can be positive, entertaining and educational. Most podcasts are free, but some offer premium membership for those bothered by advertising.

How do I find podcasts?

◗ From a podcast site. If you do not already have Apple Podcasts app (purple icon) or another podcast site on your device, you can find and download it from the Apple Store or the Google Play Store. Once you have the podcast app icon on your device, search within it to find and follow the podcaster you like. Now you’ll have access to all previous and future podcasts.

◗ From your preferred search engine: enter your search term (ie. gardening or ecology) and listen at your computer or on your phone. To subscribe from a podcaster’s website, look for the live link to choose your delivery method. Some may arrive by weekly email, or they can come directly to your app. You can create bookmarks on your computer to save podcasts.

◗ From YouTube: You can listen and watch directly from the website itself and add it to your favourites so you can find it easily.

How can I squeeze gardening podcasts into my daily life?

BEST TIMES TO TUNE IN ARE:

• On your daily walk

• On your commute via train, bus, or car

• On long trips

• While gardening

• While waiting for the dentist, the doctor, or anyone with office hours

A recent Toronto Master Gardeners meeting was devoted entirely to Ecological Gardening. Here is a list of some of our favourite/award winning podcasts. The links take you to their websites where you can explore everything on offer.

• Two Minutes in the Garden with Melissa J Will, The Empress of Dirt.* Melissa offers bite-sized informative updates on gardening basics, myths, and other subjects of interest

to Ontario gardeners. A recent July podcast is Attracting Fireflies to Your Garden. https://empressofdirt.net/ two-minutes-in-the-garden/

• A Way to Garden (horticultural how-to and woo-woo) with Margaret Roach, podcaster and blogger. Some recent/popular episodes of interest are Beeches Under Pressure and How effective are Cultivars? with Doug Tallamy. https://awaytogarden.com/podcast/

• Ontario Today – The Gardening Show with Paul Zammit.* You can hear this weekly on Mondays during the noon hour on CBC Radio or listen in on saved episodes. In a recent episode, our gardening expert answered questions about helping plants during times of great heat. https://www.cbc.ca/ listen/live-radio/1-45-ontario-today

• The Joe Gardener Show with Joe Lamp’l. Joe is the engaging host and executive producer of the PBS show Growing a Greener World® and frequent television guest. He blogs, podcasts and creates videos on all aspects: supporting wildlife, phenology, grafting fruit trees, vegetable production. https://joegardener.com/podcasts/

• Growing Greener with Tom Christopher. Addressing environmental challenges begins in our own backyards. Tom shares interviews with gardening experts who work and live in harmony with nature. In the July 2, 2025 podcast he talks with the authors of a new free online guide for helping your native plants adapt to a changing climate. https://www.thomas christophergardens.com/podcast

• Cultivating Place (NPR) created by Jennifer Jewell. Through thoughtful

conversations with growers, gardeners, naturalists, scientists, artists and thinkers, this podcast illustrates the ways in which gardens are integral to our natural and cultural literacy. The weekly conversations celebrate how cultivated spaces nourish our bodies and feed our spirits. Topics range delightfully from moth-watching to community gardening. https://www.npr.org/ podcasts/503170304/cultivating-placeconversations-on-natural-h

• Flora & Fauna is a podcast within the magazine/website of Canada’s Local Gardener.* Former MP Dorothy Dobbie and her daughter Shauna, both well-known gardeners, interview authors, retailers, broadcasters and local gardeners from all over Canada. Topics range from seeds to soil nutrients to power tools to Indigenous gardens. They also offer their own garden advice and insights. https://localgardener.net/flora-ampfauna-podcast/

Their blogs, dealing with a myriad of timely issues, can be found at the main menu. A recent July blog, Water while you’re away: 10 things about keeping the garden hydrated provided help to many a Toronto gardener.

Enjoy these podcasts. If you’re like me, you will actually feel a sense of accomplishment after listening to a particularly enlightening show instead of wondering where the last half hour went looking at meaningless videos!

*Canadian content

Georgie Kennedy is a Toronto Master Gardener

Totora reeds at Lake Titicaca are central to an entire civilization

Text By Aruna Panday

1 2 3

1. BOAT, SKY, TOTORA

2. TOTORA CLUMP IN THE LAKE

3. CUTTING THE TOTORA

4. TRADITIONAL UROS BOAT

FROM A DISTANCE, Lake Titicaca shimmers green, stretching far beyond what the eye can see. Immense, remote and ancient, the largest lake in South America sits 3,800 metres above sea level, has an area of nearly 8,400 square kilometres, and is shared between Peru and Bolivia. It is also one of just 20 ancient lakes on Earth, believed to be over three million years old. More than 25 rivers empty into Titicaca while the only outflow, Rio Desaguadero, drains five per cent of the lake, the rest is lost to evaporation making its water slightly brackish.

Totora (Schoenoplectus californicus subsp. totora), a tall, moderately salt tolerant sedge native to South America, dominates the edges and shallow waters of Lake Titicaca. Paleo evidence suggests humans introduced totora from the Pacific coast to the lake about 3,500 years ago. This plant, essential to the region’s ecology, is exceedingly special because it’s one of the very few aquatic plants to become central to an entire civilization, especially a floating one.

‘Reed,’ from the Anglo Saxon word ‘hreod’ (plant with a stalk or reed), is a common descriptive term rather than a taxonomic category. It identifies tall, slender, flexible plants that grow in wetlands, shallow water or along lake and river edges. Reeds have stems that are fibrous or hollow, making them useful for weaving, building, thatching and more. Taxonomic families of plants often called reed, are grasses (Poaceae), sedges (Cyperaceae) and rushes (Juncaceae). While they appear similar, they are botanically different. A classic mnemonic helps with field identification: Sedges have edges, rushes are round, grasses have nodes where leaves are found.

Totora, bestower of the lake’s green hue, is a perennial monocot, clonal, emergent macrophyte; an aquatic plant rooted in lakebed sediment but rising above the water’s surface. It grows in thick mono dominant stands with erect, cylindrical, tapering culms growing up to six metres high. Under optimal conditions—high nutrient availability, full sun, water depth less than two metres— it can extend up to two centimetres per day. Reproduction occurs both clonally by rhizomes and via seed. Totora is managed through deliberate plantings and burnings that remove older plants and encourage regeneration. Its buoyant, fibrous stems consist of an outer protective rind and an inner spongy pith. The internal

tissue, characterized by air pockets or channels, aids gas exchange throughout the plant. Anchored by horizontally spreading rhizomes, totora forms dense mats.

This combination of a sturdy cortex and spongy pith plus a robust rhizome system, creates a tough, flexible, resilient plant well suited to withstand wind, waves and human manipulation.