Artistic Activism c ic

A 120-POINT RESEARCH PORTFOLIO SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF A MASTER OF ARCHITECTURE (PROFESSIONAL) AT TE HERENGA WAKA - VICTORIA UNIVERSITY OF WELLINGTON

A 120-POINT RESEARCH PORTFOLIO SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF A MASTER OF ARCHITECTURE (PROFESSIONAL) AT TE HERENGA WAKA - VICTORIA UNIVERSITY OF WELLINGTON

Research and existing practice of Artivism is explored to understand further how the relationship of art and activism can coincide together to create a “medium for political protest and social activism” (Groys, 2014, n.p). Defining Artivism, or artistic activism, it is the “creative expression to cultivate awareness and social change” (Funderbunk, 2021, n.p). Gupta furthers this definition by defining the practice of artistic activism as being “dynamic”, combining the creative power of the arts and their ability to move us emotionally with the strategic planning of activism to bring about social change (2021, p. 1021).

Theaster Gates notes’s arts ability in affect to create change, “sometimes the artistic affect is better than policy, it’s more complicatedly inclusive than the town hall meeting” (Gates, 2016, n.p). Artivism expands upon this by merging the goals of activism, effect, and the goals of art, affect, to bring about powerful social change and impact. However, this blend of art (affect) and activism (effect) has been criticised (Groys, 2014). Groys notes that Artivism comes under attack from both of the “opposite perspectives—traditionally artistic and traditionally activist ones” with critiques such as artistic quality and ‘aestheticisation’ (2014, n.p). In response to this, Duncombe and Lambert note that Artivism does not try to be just art, nor just activism, instead being its own thing (2014, p.27). Artivism, being its own practice, is described as “[m]aking artwork about politics is not the same as making art that works politically. The former aims to, again, raise awareness, while the latter is directed towards changing the world” (Duncombe & Lambert, 2014, p.27). Gates, Groys, Duncombe, and Lambert identify Artivism’s strength to blend affect and effect, in doing so, being respectively considered its own practice beyond just art or activism.

An important question in the research of Artivism is what quantifies its success. Only once a clear direct target or aim has been identified can Artivism be deemed successful, “we can know what it aims to do in particular, that is: what activist artists want their art to do. Once we have addressed this question, we can begin to investigate whether activist art has succeeded” (Duncombe & Lambert, 2014, p. 35). Therefore, while art may try to evoke and create feelings of “awe and beauty”, Artivism attempts to create a target and advocate an agenda through artistic means (Dissanayake, 1990, n.p). Artivism merges artistic and activist

methods and produces methods that are unique to its practice: “[a]rtistic activism is not merely a tactic that helps you be a better activist, but an entire approach—a perspective, a practice, a philosophy— that transforms activism” (Duncombe & Lambert, 2014, p.35). Combining the aesthetic with the instrumental, the Handbook for Artistic Strategies in Real Politics summarises artivist methods into nine categories (Malzacher, 2014). The applicability of artivist methods is directly linked to what the artivist targets. If an artivist wanted to display a message, they might enact methods of ‘documenting and leaking’ such as posters and defacing. While if an artivist sought to enact more violent direct action, they might engage in ‘playing the law’ such as shoplifting, hacking and expropriating money (Malzacjer, 2014, pp. 10-11). Therefore, targets are crucial to the practice of Artivism and the selection of appropriate methods.

The following section explores the relationship between art and architecture to further the understanding of blurring methods to strengthen advocacy and direct action for art accessibility.

The following three design chapters document three forms of direct action that together are activists for the arts, advocating the agenda of Artistic Activism.

“Direct action is a type of activism in which participants act directly, ignoring established (or institutionalised) political and social procedures” (D.A.M, n.d, n.p)

Each form of direct action responds to a target. As discussed in the literary context, the measure of success in terms of Artivism can only be determined if there is a target (Duncombe & Lambert, 2014). In the case of the three forms of direct action, when ‘target’ is referred to, it is the accessibility of the arts in Aotearoa.

TARGET = AOTEAROA’S ART ACCESSIBILITY

What lies ahead is colourful, exuberant, and bold - advocating for the right to access art across Aotearoa.

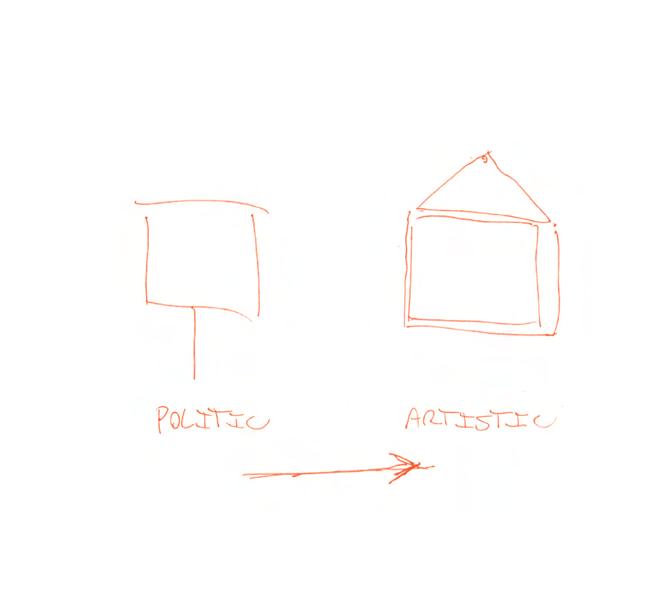

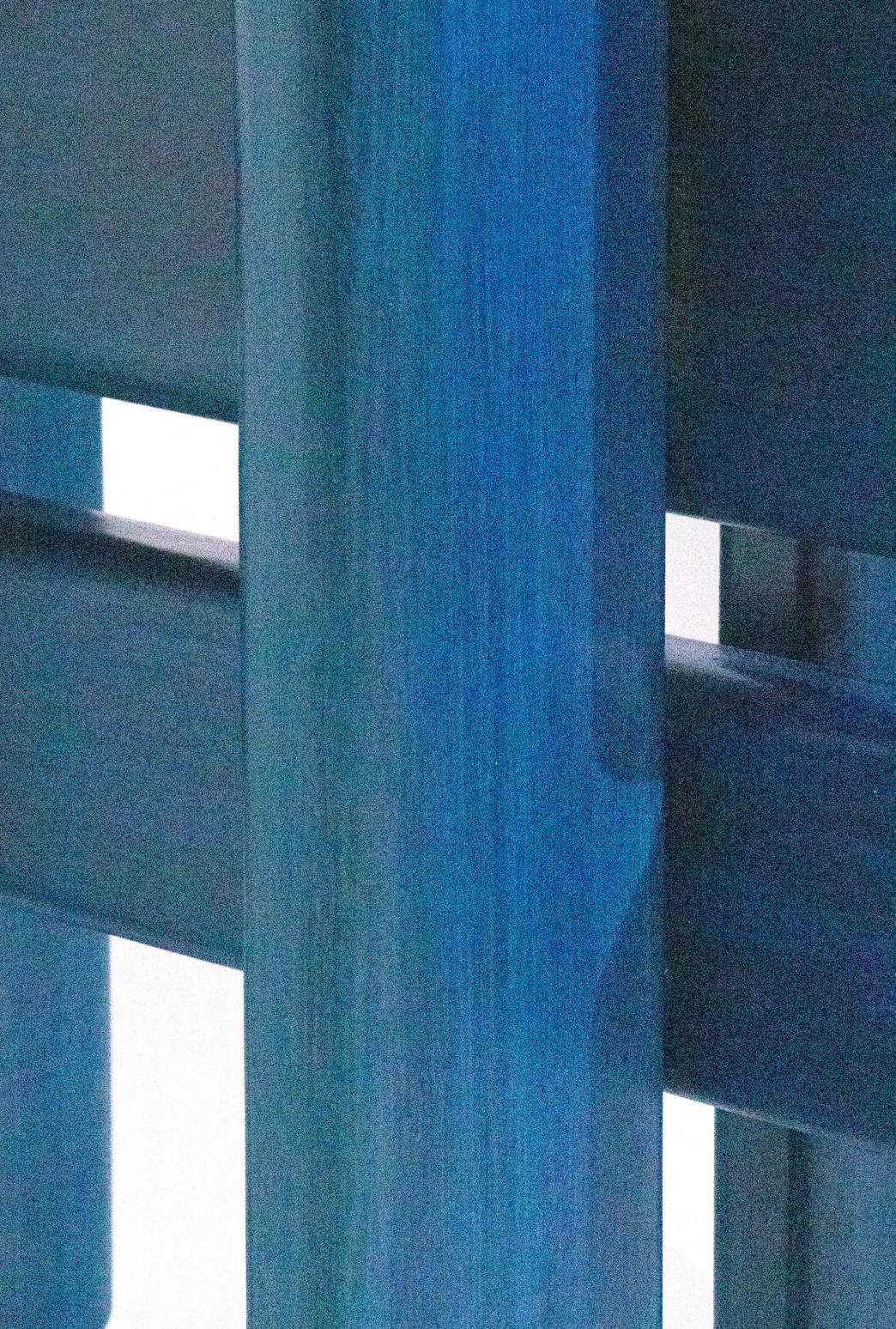

Much to the disapproval of the workshop, one of the viewing devices was stained blue. Staining aimed to push the normative and to expand the key for viewing (represented with blue pencil) beyond the canvas and into a physical matter through the viewing device. With a natural blue stain, one of the viewing devices became a physical depiction of the key for viewing while also aiming to represent the “exciting nature of the artist collectives” in contrast to the reserved traditional nature of the gallery bench (Desmarais, 2019, n.p). This decision created a stronger relationship between the viewing device, object, and the activist documentation, art. It, too, unintentionally brought upon a lot of opinion and scrutiny from some. Being described as ‘disgusting’, ‘sin’, and ‘wasteful’ (even though it was timber salvaged from waste) for its rejection of normativity and altering of the timber’s natural tone –but perhaps this further proves the installations aim to push the norms of the traditional gallery bench and setting.

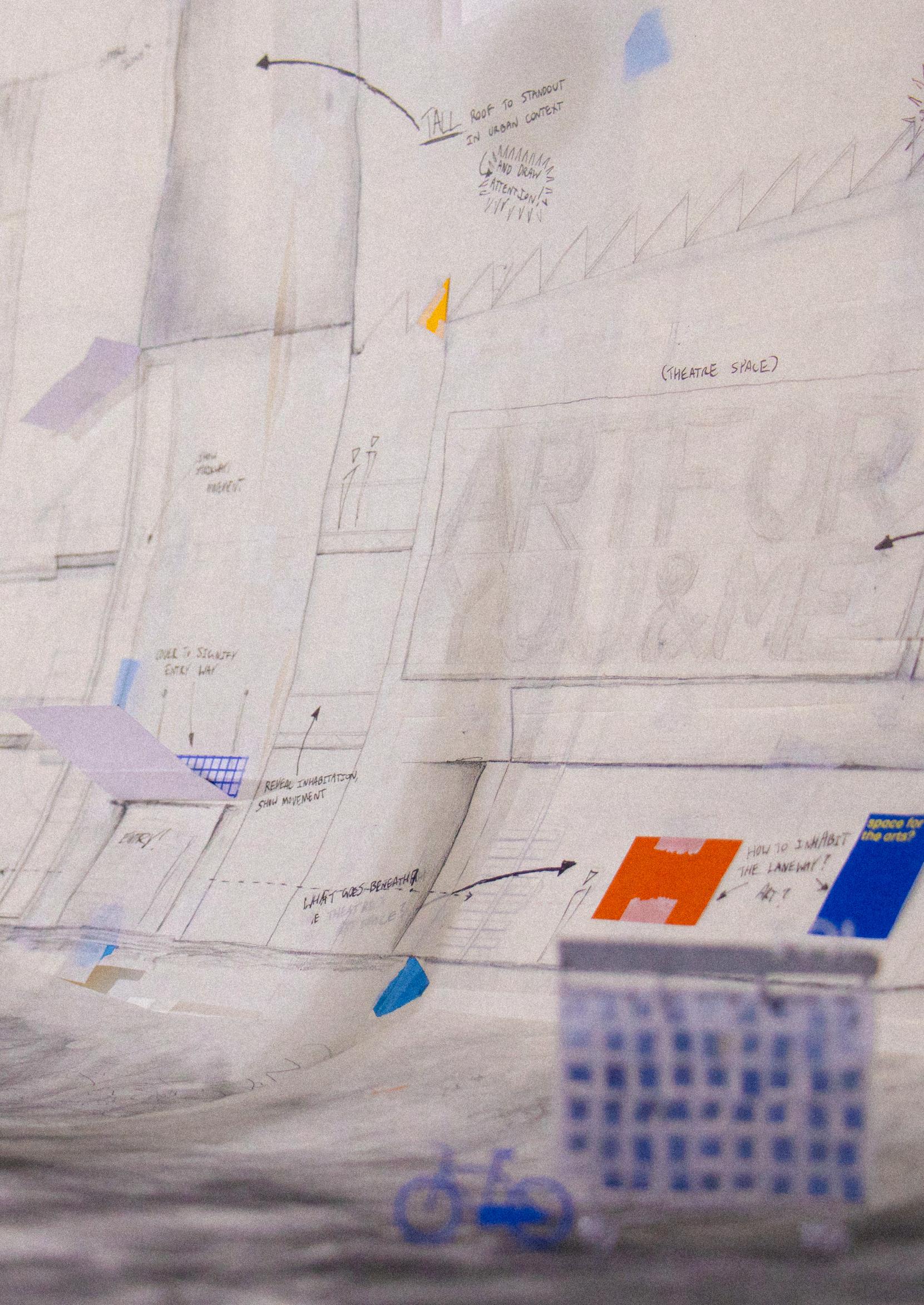

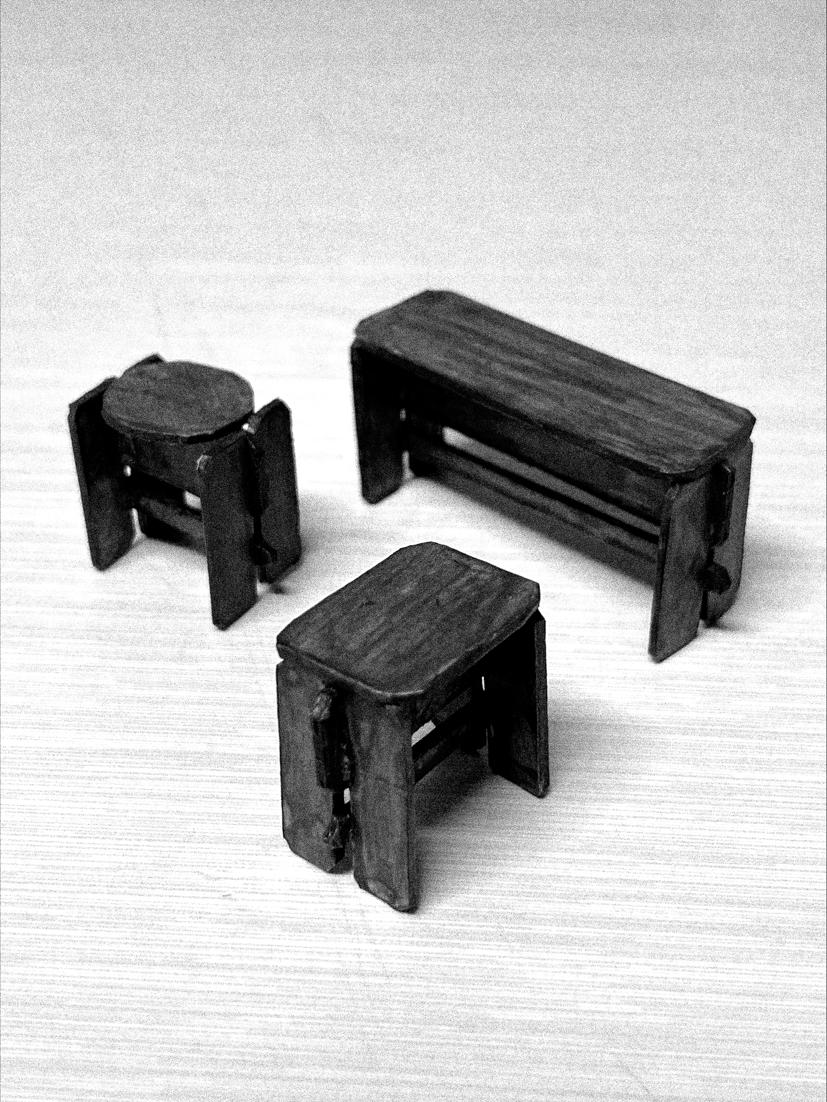

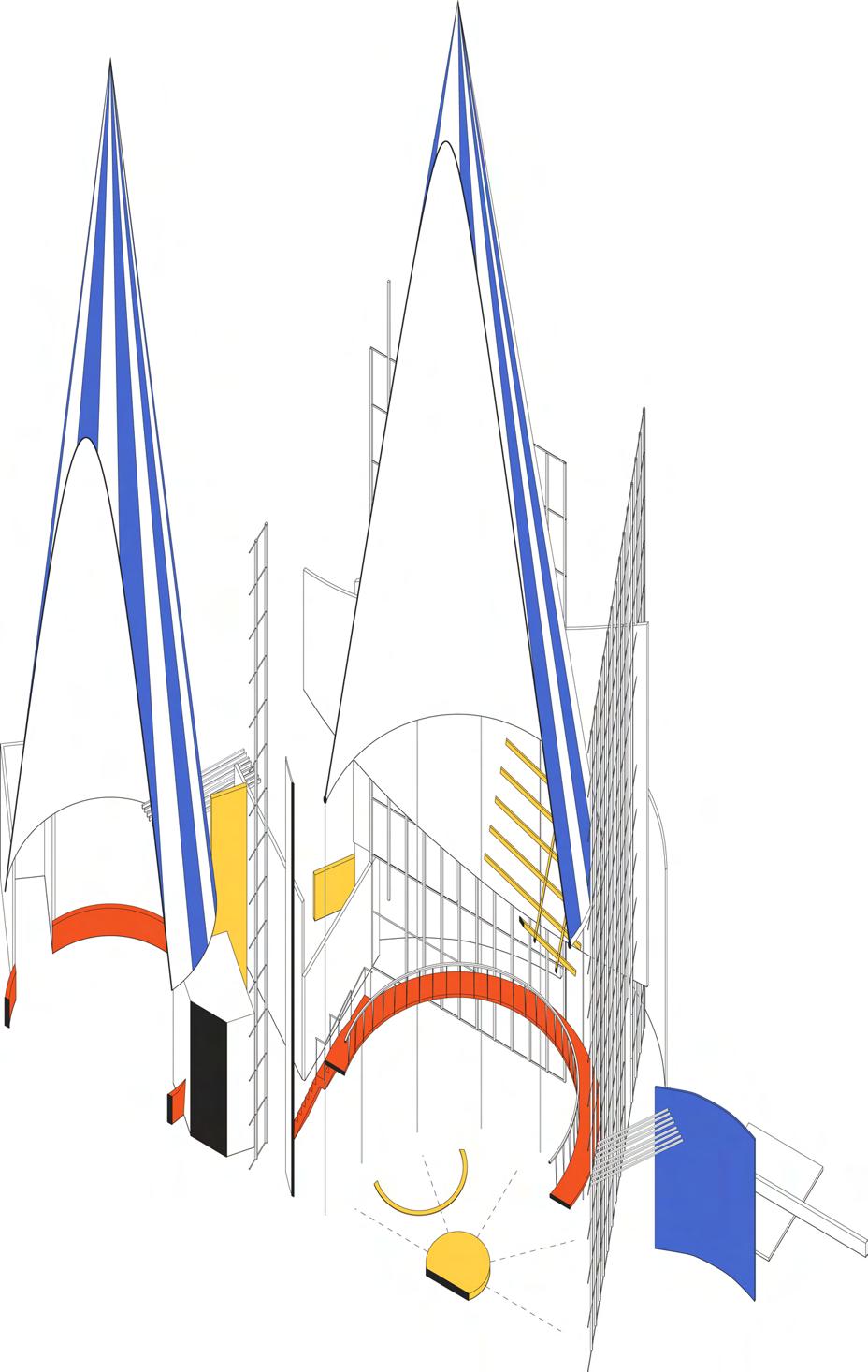

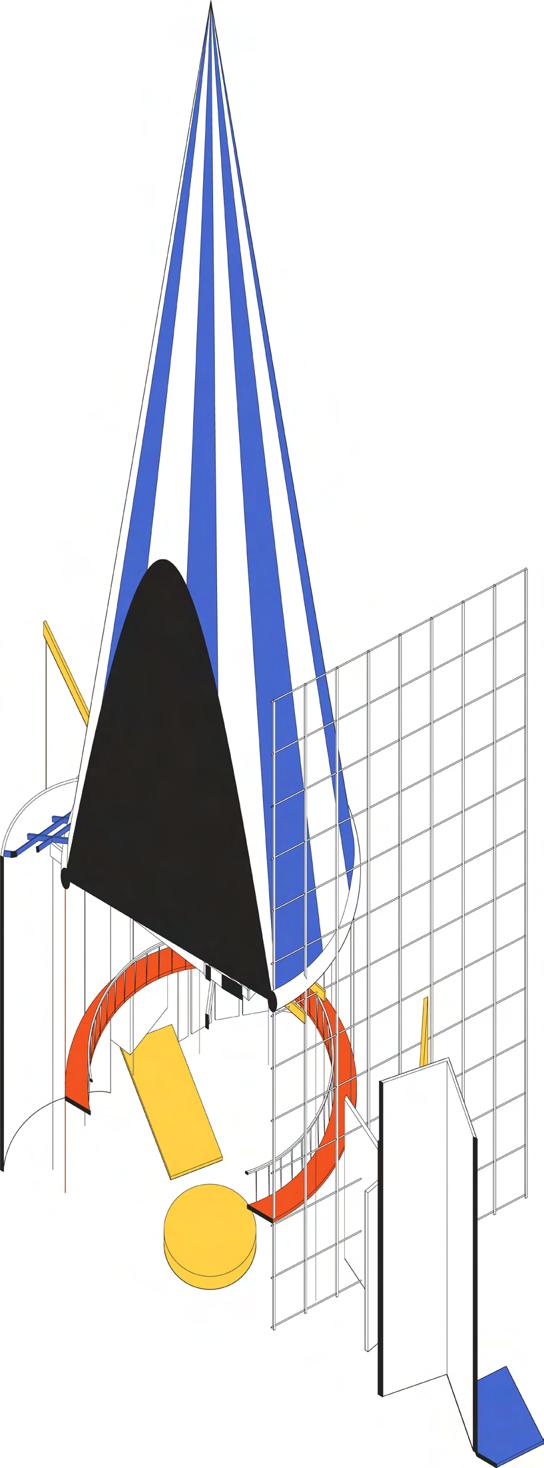

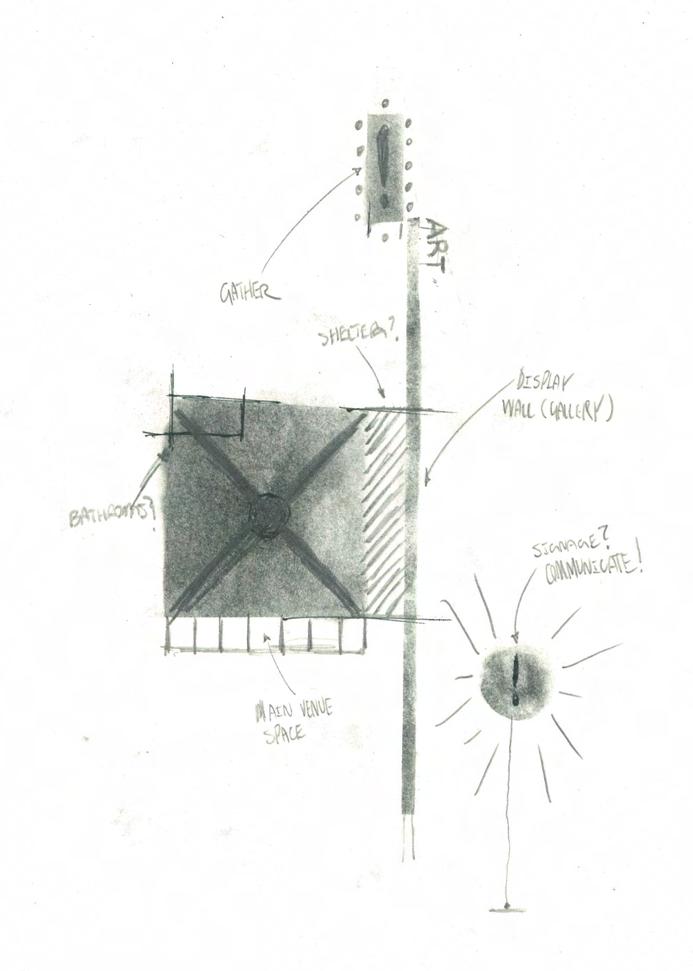

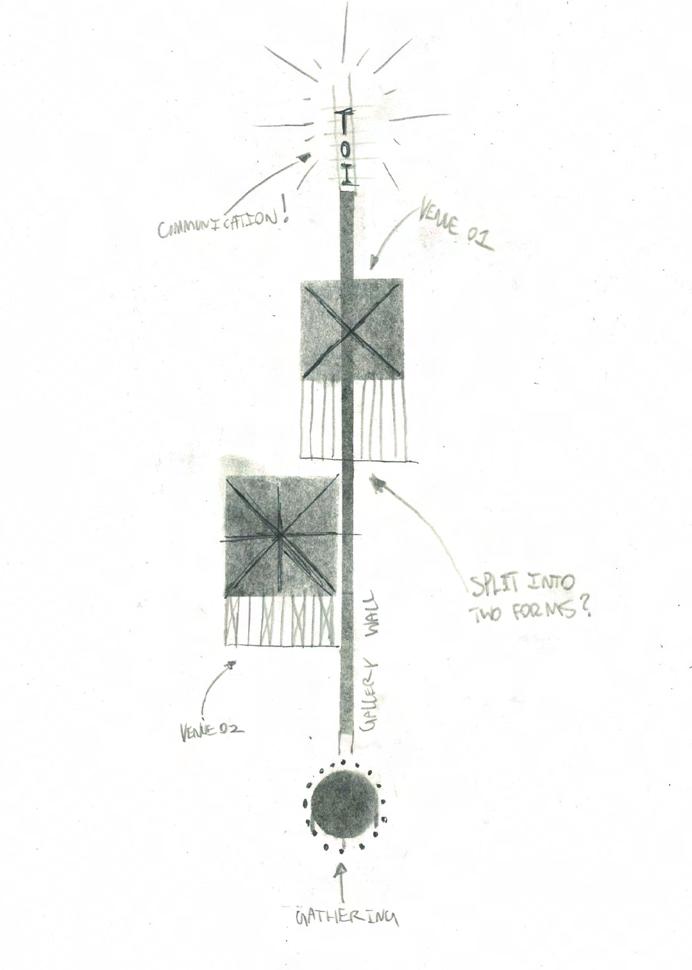

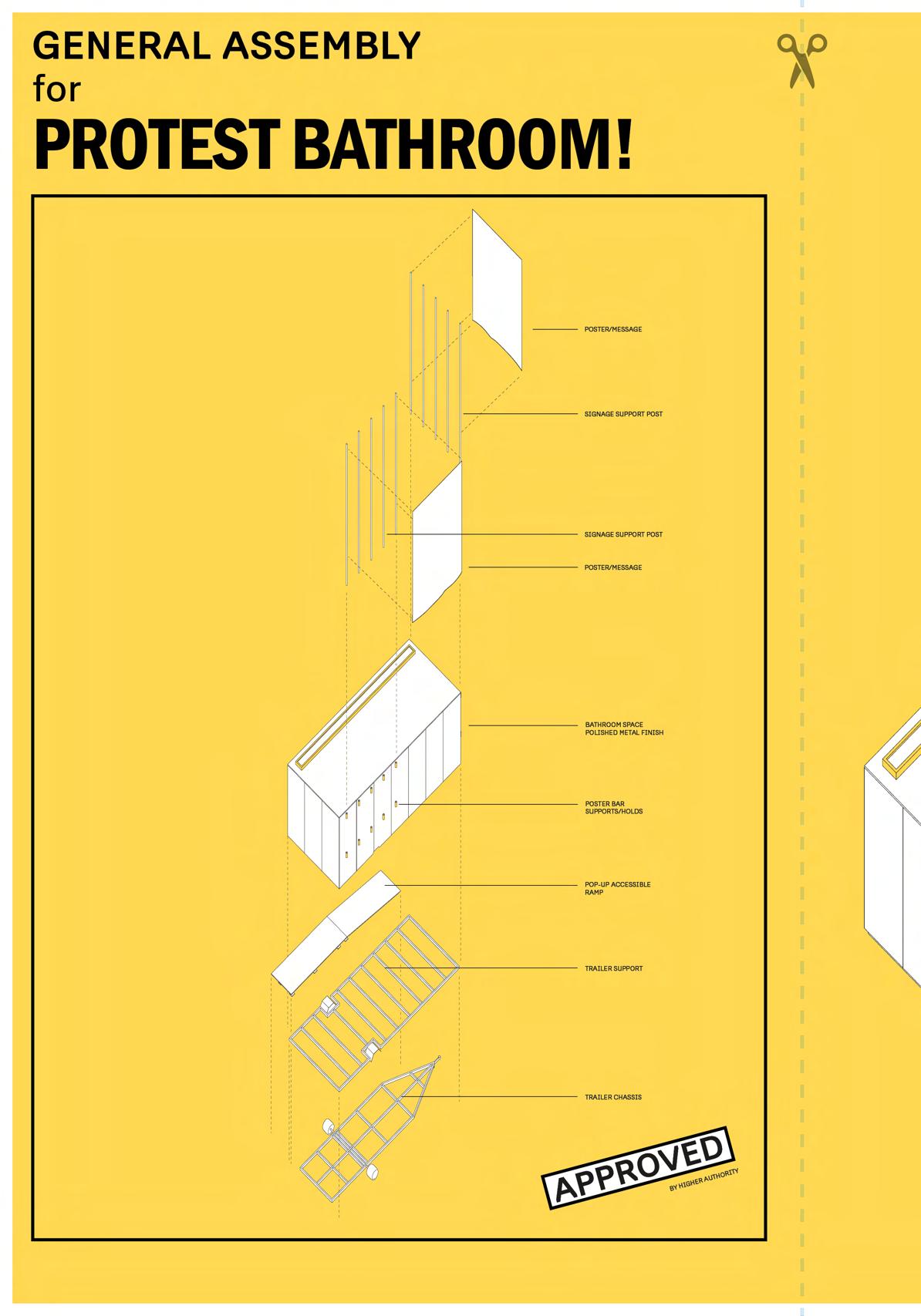

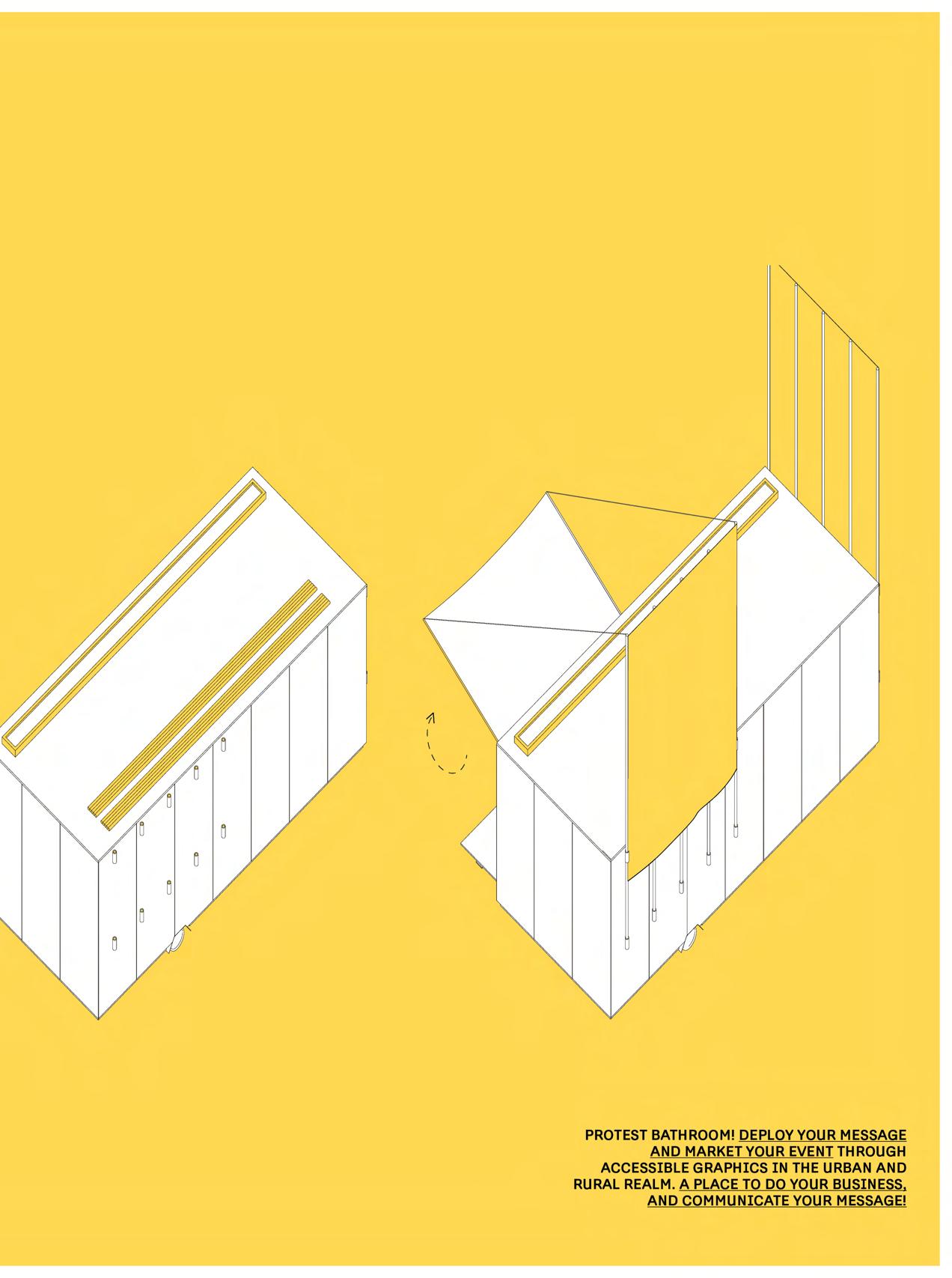

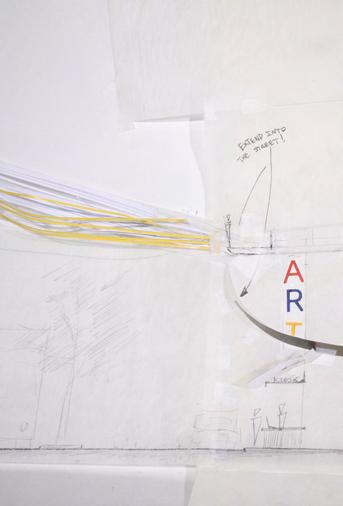

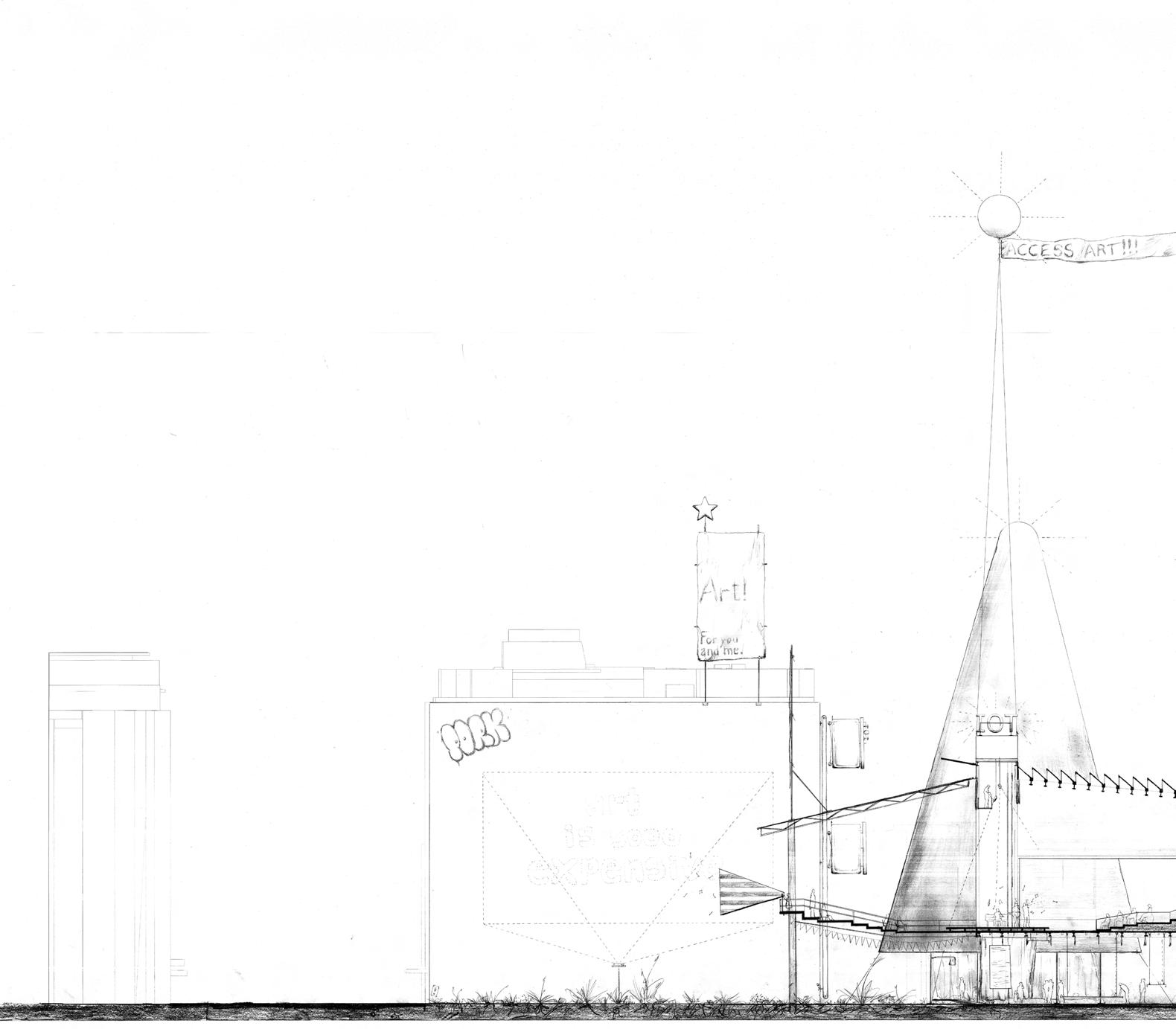

Development aimed to combine the experimentation and methods thus far to produce interventions that target art accessibility and challenge barriers of distance. Sketching, overlaying, and digital modelling were used for development. Initial form-finding extracted from Art Inhabitation (Chapter 04) were overlaid atop the programme study as ‘productive devices’ to alter the programme block forms (O’Carroll, 2019). This allows the artistic to inform the architectural. Practicalities, such as the need to be transported and ‘pop-up’, were considered using scaffolding structures and trailer-sized elements to ensure the plausibility of the speculative design. This process successfully found an initial concept for the Pop-Up Arts explored through physical modelling and sketching. This timing was well aligned with the threemonth review, allowing the initial design concept to receive feedback and critique from viewers.

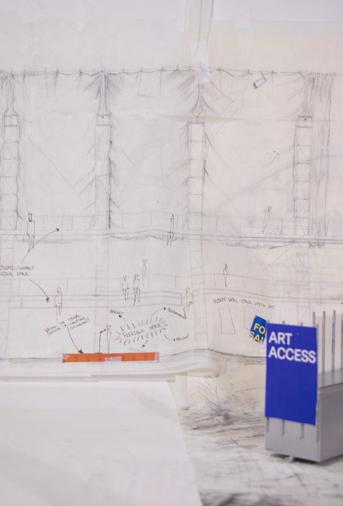

Pop-Up Arts set its target on art accessibility, which aimed to challenge the barriers of distance to accessing the arts (Creative NZ, 2023). It sought to do this by mobilising the arts and using inhabitation to temporarily transform vacant sites into spaces for the arts. Smout and Allen’s method of ‘productive devices’ and a method of sketching provided a good start in transforming the result of the previous chapter into a form-finding device, but it quickly became overcomplicated (O’Carroll, 2019). Therefore, the artistic method of abstraction was used to simplify these forms and allow a method of architecturalising to be enacted that imagined transforming art into architecture. By cutting out and architecturalising paper models into both plan and section, initial forms were successfully found, while also enacting the research questions exploration of the relations of art and architecture – but was yet to engage activism.

Architecturalising Activism aimed to explore the relationship of activism and architecture to assist in establishing the programme. This was successful in determining the spatial intentions of the Pop-Up Arts. Critical at this point was considering how the Pop-Up Arts could inhabit any site, rural or urban, to achieve its aim and target of distance barriers (Creative NZ, 2023). What resulted was the decision for the spatial intentions of the Pop-Up Arts to come together as individual temporary interventions that can transform the spaces they inhabit, “ephemeral architectures encourage both architects and the public to reimagine the possibilities of urban living” (Ferreira, 2024). The temporary, pop-up, and transportable natures of the Pop-Up Arts interventions achieved a successful form of direct action to barriers of distance.

The Pop-Up Arts documented each intervention, demonstrating both the assembly and transportation process to enact accessible means of recreating, influenced by The Mirror Barricade (Tools for Action 2016). A model and visualisations were used to demonstrate the ability for the Pop-Up Arts to inhabit an array of sites and bring the arts throughout Aotearoa.

Next, the public scale responds to a shift from temporary to permanent and siteless to sited. Returning to the creative capital, near the Wellington City Gallery, the public scale inhabits Reading Cinemas. Unlike the Pop-Up Arts, this next form of direct action explores a relationship of art, architecture and activism by inhabiting a permanent architectural response unlike that of the temporary Pop-Up Arts. A shift from temporary to permanent propels us into the final and largest of the three forms of direct action - Arts Corridor (Chapter 06).

Deploy Development o

Unlike the other parts of the Arts Corridor, deploy is imagined as a temporary activist act. Deploy aims to temporarily inhabit the remaining cinema structure and site before its inevitable development and aims to continue advocacy for the arts, the site, and its potential to reshape Wellington.

Methods of sketching, digital and physical modelling created deploy. Looking at the Mirror Barricade and its ability to reflect its surroundings came the idea of using reflective materials with the activist method of ‘blow up’, used earlier in the Pop-Up Arts, to create the activist act of deploy (Balen, 2014). Sketching and models explored how the material could drape along the remaining cinema while rising to extreme heights with light-up balloons suspending banners with activist messages. At extreme height and scale, advocacy becomes inescapable from view (Occuprint, 2014).

Through design-as-research, the process was continuously reflected upon, providing direction and collection of what is working and what is not to be identified. The iterative process allowed a wide range of methods to be tested, positively contributing to the exploration of the relationships of art, architecture, and activism. The processes enacted in the development stages of each of the three direct actions blurred the artistic, architectural and activist to strengthen the final responses of the three scales.

The installation successfully reimagined the gallery space by inhabiting undefined spaces and began an exploration of inhabitations ability to inform the relationships of art, architecture and activism. The activist documentation was an autoethnographic process being conducted and documented by myself, the author. If the thesis had ethics approval, the opportunity to involve creative communities within this documentation process could strengthen and alter the result of the installation. Reflected upon in the conclusion of the installation chapter was the stronger exploration of art and architecture, with activism not similarly explored to the same extent. Reflection allowed this to be responded to directly within the following direct action, PopUp Arts, by focusing on pushing activist methods further in the design process.

Complying with CUAP guidelines through three designed responses of direct action was successful in generating varied responses towards art accessibility and extensive testing of inhabitations’ ability to inform the relationships of art, architecture and activism. However, the sheer quantity of work conducted in this thesis did not allow areas to be fully explored to their maximum potential. Emphasising the importance of reflection throughout the design process to understand what should and should not be further developed. Although, the three scales and shift from temporary to pop-up to permanent allowed an in-depth and successful exploration of inhabitations’ ability to inform the relationship of art, architecture and activism in comparison to having had only conducted one developed design response.

Arts Corridor, the final form of direct action, became arguably the most complex due to its scale, permanence, and site. These complexities

provided a rich ground for activist response through an alternative to the likely commercial development of the site. The large scale of the site hindered its ability to create a well-developed and effective response, being quickly identified in the process and scaled down to the laneway.

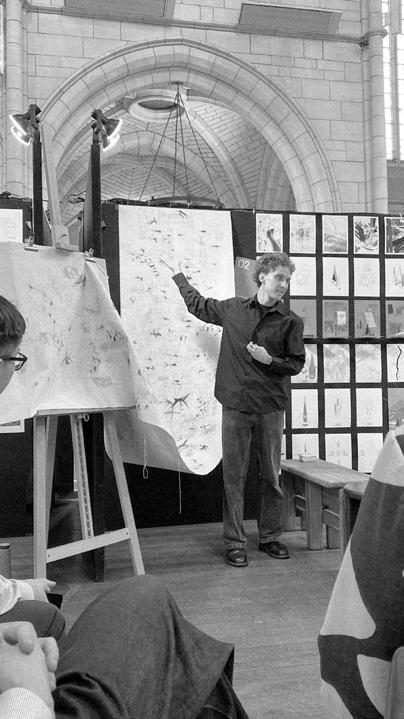

On reflection, engagement and viewing of the work with industry, academics and the public continued to reaffirm the urgency and need for art accessibility in Aotearoa. Industry professionals and the public responded well to the forms of direct action and their ability to read as plausible – particularly successful through physical models. Although, a continued note by academics was a concern that this project was not ‘speculative’ nor ‘crazy enough’ to be considered activist. However, this thesis aligns and shares argument with Kasonga (2024) who argues that this view of activism narrows and reinforces the negative ideas that activism is purely a spectacle. The work in Artistic Activism argued to create responses that make the speculative feel plausible to create direct action that could be imagined responding to the very real issues of art accessibility in Aotearoa.

Thank you, I hope you enjoyed! -T