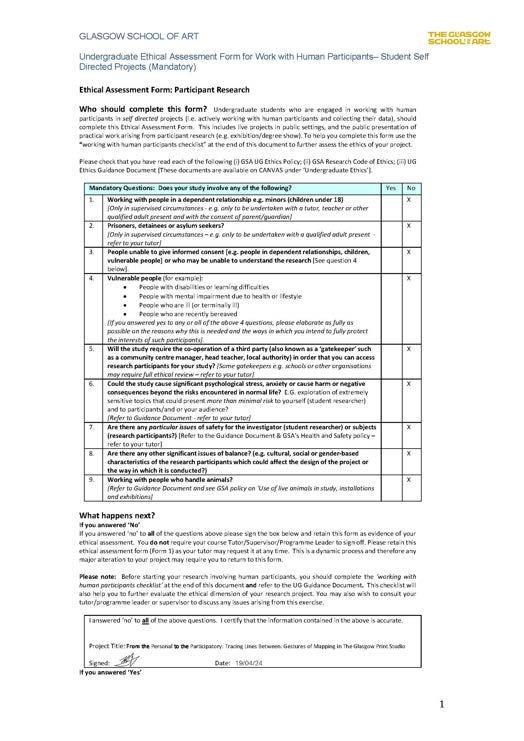

Glasgow Print Studio: ABriefIntroduction

The context for this study is the Glasgow Print Studio. Since 1972 the studio has risen from an informal workshop in the basement of a west end tenement, to an internationally renowned centre for learning, making, exhibiting and buying art 5 Started by graduates of The Glasgow School of Art in an attempt to collectivise access to printing equipment and to continue their practice after graduation, the democratic accessible nature of the studio, with a strong emphasis on education, continues to define the artist-led organisation’s aims. A reliance and knowledge of equipment is fundamental to a printmaking practice; indeed, it was the arrival of an etching press to Glasgow with studio co-founder Beth Fischer, that sparked the genesis of the project 6

The series of processes that form the practice of printmaking and their dependence on equipment give the pursuit a unique position within arts spaces. Marrying their legacy as places of mass production with studios for culturing fine art practice creates spaces that balance thought and action, inspiration and process. Sonobe documents the manifestation of this in her timelapse videos entitled “choreography around the press”, a simple but effective illustration of the interconnection of artists and equipment in these spaces, activation through technological, creative and social exchange 7 .

Figure 2: Rinako Sonobe (@rinakosonobe02), The "choreography around the press" at @hfatelierdegravura in May in São Paulo, Brazil. Instagram photo, October 5, 2023. https://www.instagram.com/p/CyCDRAKoL-V/.

5 Clare Henry, ‘The First 21 Years - Glasgow Print Studio’ Accessed 23 February 2024 https://www.gpsart.co.uk/DownloadDocs/Clare_Henry_GPS_essay_1993.pdf

6 Clare Henry ‘Glasgow Print Studio Celebrates 50 Years Of Printmaking – Clare Henry’, Accessed 23 February 2024 https://artlyst.com/features/glasgowprint-studio-celebrates-50-years-printmaking-clare-henry/.

7 Rinako Sonobe, (@rinakosonobe02), The "choreography around the press" at @hfatelierdegravura in May in São Paulo, Brazil. Instagram photo, October 5, 2023. https://www.instagram.com/p/CyCDRAKoL-V/.

In each of the studio’s spaces other artists are found, standing over acid baths as they wait for their metal plate to etch, lifting and adjusting screen printing beds, discussing work over cups of tea, trimming finished prints for sale or exhibition. The presence of other artists is inescapable in the studio, and the process of learning to share the space efficiently is just as important for new printers as learning their chosen print craft. All these artists’ days are anchored by the reason they use the studios; access to facilities and equipment not financially or practically possible for most artists to use privately. From the magnificent eagle press to the rooms for aquatint and silk screen preparation, each of these tools are physical and demand to be held and known. As printers using the studio, each grasp of the press handle and brandishing of the screen squeegee links us to our colleagues in print, from those waiting to use the equipment after your turn, to a history of artists who have held the same handles.

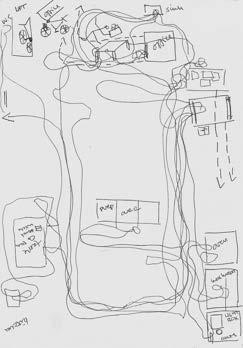

Below is an initial mapping of the Glasgow Print Studio workshop space, drawn in the form of a roughly sketched floorplan. The looseness of the lines and use of soft pencil allow the questing hand’s investigation to be traced in graphite dust as the rooms and their uses take form.

Figure 3: Tom Matthews, Glasgow Print Studio Sketch floorplan, 2024, pencil on tracing paper

Chapter I: Gestures of personal mapping

“Drawing is the opening of form. This can be thought in two ways: opening in the sense of a beginning, departure, origin, dispatch, impetus, or sketching out, and opening in the sense of an availability or inherent capacity. According to the first sense, drawing evokes more the gesture of drawing than the traced figure. According to the second, it indicates the figure’s essential incompleteness, a non-closure or non-totalizing of form.” 8

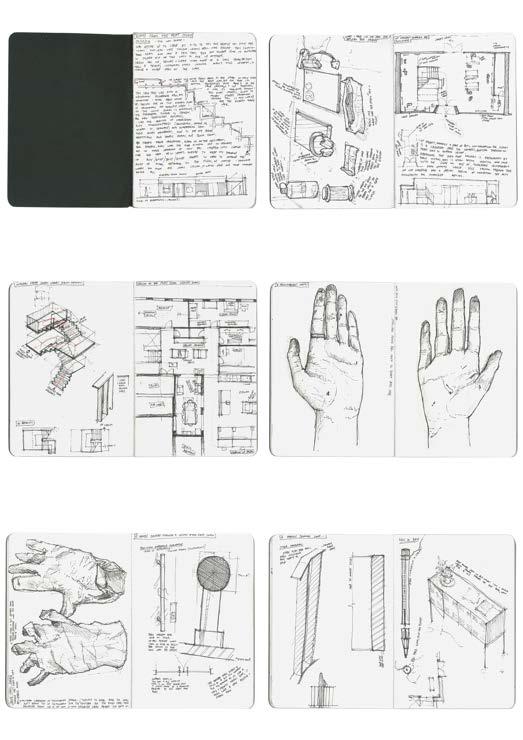

Choosing drawing as a methodology for the initial mapping of the space was a deliberate choice to engage with the process of “unlearning prior knowledge, and of cultivating an open, vulnerable orientation to encounters in the field” 9 as Brice describes. As someone familiar with the space and its processes, I am conscious of unpicking ways in which my acquired knowledge and familiarity could act as a constraint or be used to the advantage of the study. John Berger states “drawing is discovery” 10, a statement that aligns with my experience of the observational demands of representing space in a drawing, allowing even well-known spaces to be discovered anew. A daily sketch journal kept from August 2020-21 11 clearly substantiated the ability for observational drawings, often in times and spaces that would be unusual for me to initiate drawing, enabling surprising and deep exploration of an artist’s environment.

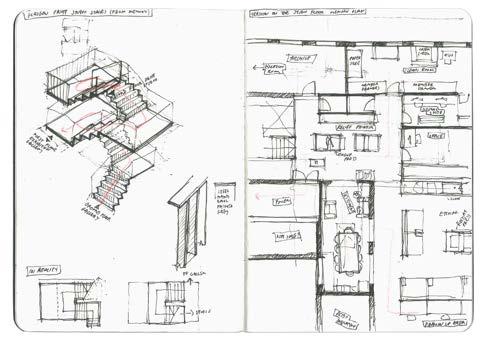

Therefore, the start of my self-directed research residency at the Glasgow Print Studio involved the simple purchase of a small black sketchbook. This book, its practicality and ease of access, has enabled me to approach a practice of ethnographic research through sketching and observation, alongside my habitual practice as a printmaker in the studio that hopes to encourage the ‘open encounters’ that Brice emphasises 12 The book moves from analytical renderings of space, in plan of axonometric form, to a narrative of held objects and surfaces over a day in the studio. The Hand’s Journey was the result of a reflection on my own inhabitation of the space, and an ambition to authentically represent this experience. Juhani Pallasmaa’s exploration of bodily knowledge centred through making and drawing in The Thinking Hand 13 connects and resonates with my environmental perception and navigation.

This embodied knowledge and memory is also defined by Michel Serres, writing about the skin of his hands; “in it, through it, with it, the world and my body touch each other, the feeling and the felt, it defines their common edge” 14. To touch and extend your body through the common edges of the studio is most clearly how I feel and

8 Jean-Luc Nancy, The Pleasure in Drawing (Trans. P. Armstrong), New York: Fordham University Press, 2013, Pg 1

9 Sage Brice, "Critical observational drawing in geography: Towards a methodology for ‘vulnerable’ research." Progress in Human Geography 0 (2023): Pg 1

10 John Berger, Berger on Drawing. Cork: Occasional Press, 2005, Pg 3.

11 Tom Matthews, Daily sketch Journal, 2021, Sketchbook, Personal Collection.

12 Brice, Pg 1.

13 Juhani Pallasmaa, The Thinking Hand, Existential and Embodied Wisdom in Architecture, Chichester: John Wiley & Sons Ltd, 2009

14 Michel Serres, The Five Senses: A Philosophy of Mingled Bodies, London: Bloomsbury, 2016, Pg 80.

digest the space. This realisation initiated the documentation of held surfaces, describing both their tectonic characteristics in 1:1 cross sections, and more qualitative aspects such as texture and feel in annotations and sketches. Excerpts from the sketchbook are included overleaf, and in its entirety as Appendix A

As well as a self-awareness of my relationship to the space and its use, this practice requires consideration of adopted ways of drawing. The resulting sketchbook drawings arguably sit within the genre of architectural documentation. Berger’s writing on drawing suggests three labels attributable to any work of mark making: “those which study and question the visible, those which put down and communicate ideas, and those done from memory ” 15. It is important to state that much of this critical analysis of drawing as a practice and my approach is post-rationalised, and the act of drawing was intuitive and non-planned. As a result, the book waves between heavily notated exercises in laying out and recalling the route taken to studio, drawing s done from memory, however also a work of study and visibility. Berger’s statements emphasising the importance of differentiating and understanding every drawing into its relevant label lacks the nuance of these collected drawings. On reflection, the architectural sensibilities of these marks exist as result of my own intuition and a way of understanding my environments. Brining this drawing methodology out of the studio into the field allows a deeper communication and investigation into the space than observational drawing alone.

Alongside the sketchbook mappings I collected and curated a photographic journal focusing on textures and tones found in the Print Studio. Repetitive staining, footsteps and brushstrokes have built up shapes of patina that reflect the animation of the spaces. A collaged example of these ‘real time maps’ is included on page 8.

The balancing of analytical diagrams against experiential descriptions of surface feel and material texture begins to form an important link between the qualitative and quantitative that I will go on to explore throughout the project. It is the first stage of a line of enquiry that seeks elements of commonality amongst the experience of the individual.

15 John Berger, Berger on Drawing. Cork: Occasional Press, 2005, Pg 46.

Figure 4: Tom Matthews, Print Studio Sketchbook Page 8-9, 2024, Pen and coloured pencil on paper.

Figure 6: Tom Matthews, Print Studio Sketchbook Page 4-5, 2024, Pen and coloured pencil on paper

Figure 5: Tom Matthews, Print Studio Sketchbook Page 21-22, 2024, Pen on paper.

Figure 7: Tom Matthews, Print Studio Patina Collage, 2024, Digital Photographic collage

Acidroomtap

Wallbysolventbottles

Platesmokingwall

Aquatintroomdoor

Varnish wall

Acid room wall

Chapter II: Gestures of participatory mapping

“The movements of crowds, dancers, fighters recall the inevitable intrusion of bodies into architectural spaces, the intrusion of one order into another…”, writes Bernard Tschumi, describing The Manhattan transcripts and its ambition “…to record accurately such confrontations, without falling into functionalist formulas” 16. The formulas that Tschumi addresses, the visual grammar of the architectural draftsman, fail to represent the ‘sound, touch, or the movement of bodies through spaces’ 17

This project is focused on investigating and representing multiplicities of spatial experience, from a perspective that addresses the body’s ‘intrusion’ into an architectural space. Exploring this through the participation of others is invaluable in understanding spatial experiences beyond my own, alongside a deeper appreciation for the practice of mapping as communication. This element of the research was positioned to initiate dialogues, be they verbal or visual, around the representation of space in relation to activity and use, and to ask questions about the power of mapping as a tool of communication. Forming and curating a brief for this exercise was an interesting process exploring thresholds of control and explanation, which this chapter documents. My initial sketchbook mapping and focus on ‘a hands journey’ represents a very personal reflection on spatial experience, however it is in holding and using these shared objects that brings the studio its purpose and sense of communality. This connection was the initial anchor point around which I began to tease out a brief for engagement.

Figure 8: Bernard Tschumi, The Manhattan Transcripts, 1976-1981. Digital Image. Accessed 3 April 2024. https://www.tschumi.com/projects/18/

16 Bernard Tschumi, "Illustrated Index: Themes from the Manhattan Transcripts", AA Files, 4 (1983),Pg 69.

17 Bernard Tschumi, Architecture Concepts: Red is Not a Colour. New York: Rizzoli, 2012, Pg 19.

Adele Irving and Oliver Moss’s project Imaging Homelessness in a City of Care is an example of participant mapping using existing maps as the basis for annotation and elaboration. The project involved 30 participants with experience of rough sleeping in Newcastle and asked them to inscribe maps of the city with their anecdotes and comments The graphical language of the roads and urban arteries has an abstract unpersonal character that makes space for the expression of qualitative subjectivity in the form of handwritten text 18 . A similar approach was considered for this study, however I felt that a visual framework would constrain the drawing of movement and spatial perception into defined and existing boundaries. I therefore opted for a blank page, free of reference and structure, for the participants’ starting point.

Figure 9: Adele Irving and Oliver Moss, Participant Maps, 2014, Digital Image. Accessed 2 February 2024, https://esrcimaginghomelessness.wordpress.com/participant-maps/

18 Adele Irving and Oliver Moss. "Imaging Homelessness in a City of Care – Participatory Mapping with Homeless People." In This Is Not An Atlas, ed. Kollektiv Orangotango+ (Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag, 2018), Pg 270-273

14 February 2024, http://www.losingmyself.ie/.

10: Niall McLaughlin and Yeoryia Manolopoulou, Social Drawings, 2016, Pen on paper. accessed 14 February 2024, http://www.losingmyself.ie/.

In continuation with the lines of enquiry of social interaction and physical interaction with shared equipment, I chose these themes as suggested iconographic anchors between which movement and activity could be visually described. Architects Niall McLaughlin and Yeoryia Manolopoulou represented Ireland in the 15th Architecture Biennale with their project losing myself: a collection of drawings, conversations and texts exploring how people with Alzheimer’s experience space. Their primary methodology of process and representation was through “time-based projected drawing” 19 in which they recognise the fixed and restrictive nature of the architectural plan. Their research and writing documents drawings by their workshop participants in which the act of drawing becomes the mapping practice. Through animations and moving image they allow the hand’s inhabitation of the paper and perceived space to represent the body in space. Connecting the gestural hand in mapping, and the inhabitation of movement through space is also something noted by Tim Ingold, referencing the gesturing hands of storytellers as fleeting maps traced through the air 20

In continuation with the lines of enquiry of social interaction and physical interaction with shared equipment, I chose these themes as suggested iconographic anchors between which movement and activity could be visually described. Architects Niall McLaughlin and Yeoryia Manolopoulou represented Ireland in the 15th Architecture Biennale with their project losing myself: a collection of drawings, conversations and texts exploring how people with Alzheimer’s experience space. Their primary methodology of process and representation was through “time-based projected drawing” 19 in which they recognise the fixed and restrictive nature of the architectural plan. Their research and writing documents drawings by their workshop participants in which the act of drawing becomes the mapping practice. Through animations and moving image they allow the hand’s inhabitation of the paper and perceived space to represent the body in space. Connecting the gestural hand in mapping, and the inhabitation of movement through space is also something noted by Tim Ingold, referencing the gesturing hands of storytellers as fleeting maps traced through the air 20 .

The document inviting engagement of other Print Studio members, included in Appendix B, was written acknowledging the difficulties of presenting such an open brief. Trying to give participants background and insight into the narratives of touch and interaction was important to address this, as was providing a variety of visual prompts for inspiration.

The document inviting engagement of other Print Studio members, included in Appendix B, was written acknowledging the difficulties of presenting such an open brief. Trying to give participants background and insight into the narratives of touch and interaction was important to address this, as was providing a variety of visual prompts for inspiration.

19 Niall McLaughlin and Yeoryia Manolopoulou, ‘Loosing myself’ accessed 14 February 2024, http://www.losingmyself.ie/.

19 Niall McLaughlin and Yeoryia Manolopoulou, ‘Loosing myself’ accessed 14 February 2024, http://www.losingmyself.ie/.

20 Tim Ingold, Lines : a brief history. (London: Routledge, 1948) Pg 47.

20 Tim Ingold, Lines : a brief history. (London: Routledge, 1948) Pg 47. 12

Figure

Figure 10: Niall McLaughlin and Yeoryia Manolopoulou, Social Drawings, 2016, Pen on paper. accessed

Analysis of Results

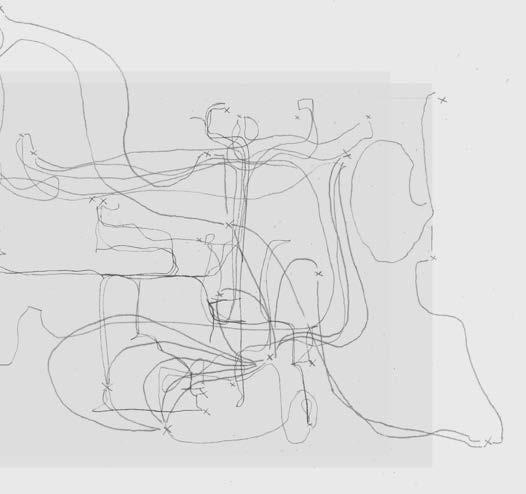

The maps I received from the hands of the Glasgow Print Studio members showed varying approaches to drawing their activity in the studio. One participant mapped the movements they made through the space, noting an X in every location a piece of communal equipment was used (Participant Map A). The resulting diagram has a similar visual grammar to that of Rinako Sonobe’s notebook sketches, referenced earlier in the essay, in its absence of contextual detail and focus on movement. This drawing can be read as charting the movements of the body in and around walls and objects, a graphic expression of Tschumi’s ‘intrusion of one order into another’ 21. However, its lack of spatial reality just as powerfully suggests a methodological mapping of process and thought. Here the hand gestures across the page, finding resting places in interactions with tools for printing, making marks that point towards animation and process.

21 Tschumi, Architecture Concepts: Red is Not a Colour, PAGE

Figure 12: Glasgow Print Studio Member, Participant Map A, 2024, Pencil on Paper.

Figure 11: Glasgow Print Studio Member, Participant Map B, 2024, Pen on Paper.

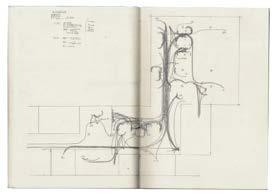

Another mapper used a similar technique of representing movement, in this case with a greater sense of contextual organisation, including more details of the objects and equipment the movements were made around (Participant Map B). In comparison to the previous map, this drawing stands out through the author’s commitment to precisely representing the body’s journey, instead of involving an amount of simplification of line that can be assumed the first mapper employed.

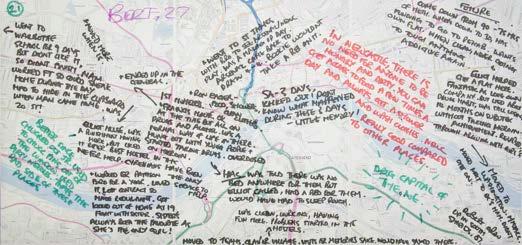

There are two maps (Participant Maps C & D) which are guided by narrative structure over definition of their maker’s geographical imprint. The lines of these maps are experiential descriptions of their makers’ session in the studio, annotated with text, and featuring small illustrations. Each illustrated chapter is arrived at across the page via a series of leading arrows and gesturing curves. In this way it relates to an experience of place that is reminiscent of Guy Debord’s map of a situationist ‘dérive’ around Parisian streets 22. Guide Psychogéographique de Paris puts humanity into urban representation, recognising the jumbled and collaged ways in which we digest place. However, these maps arguably further Debord’s ideas of experiential representation by subverting aerial conventions of cartography, a critique also put forward by Nicholas Herrmann in The Search for an Honest Map 23 , analysing discourse around the birds-eye view, as discussed in Chapter III

22 Guy Debord, ‘Guide psychogéographique de Paris’, 1957, Lithograph. accessed 3 March 2024, https://collections.fraccentre.fr/auteurs/rub/rubinventaire-detaille-90.html?authID=53&ensembleID=135

23 Nicholas Herrmann, ‘Drawing Matter: In Search of an Honest Map.’ accessed 15 February 2024, https://drawingmatter.org/in-search-of-an-honest-map/

Figure 14: Glasgow Print Studio Member, Participant Map C, 2024, Pencil on Paper.

Figure 13: Glasgow Print Studio Member, Participant Map D, 2024, Pencil on Paper.

Pushing this idea further to fictional realms could lead to in the work of Andrew Degraff, an artist known for creating ‘cinemap’ illustrations portraying place and narrative in well-known films 24. Much like Guide Psychogéographique de Paris, these maps display a mosaic of locations and landmarks connected by lines and arrows such as the way we experience place in film; a series of set locations between which we travel instantly through the power of cinema. The transitionary narrative parallels between this and Debord’s work are clear, however Degraff’s cartoon-styled axonometric projections have more relatable character than what we experience in each film scene.

Figure 15: Andrew Degraff, North By Northwest, 2017, Gouache on paper. accessed 20 February 2024. https://www.andrewdegraff.com/moviemaps#/northby-northwest/

Figure 16: Guy Debord, Guide psychogéographique de Paris, 1957, Lithograph. accessed 3 March 2024. https://collections.frac-centre.fr/auteurs/rub/rubinventaire-detaille90.html?authID=53&ensembleID=135

24 Andrew Degraff, ‘Cinemaps’, accessed 11 February 2024, https://www.andrewdegraff.com/moviemaps

Reflections

Reflecting on the diversity of outcomes from my mapping exercise suggests that each visual document cannot be read as a product of similar mapping methodologies, and comparison between them on a granular level seems unjustified. Had this exercise been employed as a means for specific spatial enquiry or investigation, it would have been appropriate to create a more defined brief and formula for mapping. However, these visual responses, and therefore also the brief, are fit for a study exploring the practice of mapping itself, using the space as a vehicle for inquiry and not the primary research objective. The safety and generosity of the Print Studio’s creative environment, and my acquaintance with it, made this task easier than perhaps it would have been elsewhere, particularly when considering the artistic sensibilities and understanding of the members. On reflection, the results of this participatory mapping are an initial view of the dynamics and processes behind engaging others in a visual and spatial task. There is potential for future extensions of this body of research through conducting participant workshops, or longer periods of engagement. However, it is important to value the mapping responses I did receive. It became clear that participants required more thought and reflection on the task before they felt comfortable to draw, and in this way the mappers chose to take the materials and instructions away with them to complete in their own time. This was a step in the process I had overlooked, assuming that most mapping would be undertaken in my supervision in the Print Studio social spaces. As a result, and in further informal conversation with the participating members, the returned maps had a large amount of careful consideration and artistic ownership by the authors.

Figure 17: Tom Matthews, Palette Knives, 2024, Digital photograph.

Chapter III: Gestures of Representative Mapping

Figure 18: Helen Scalway, Travelling Blind print no 5, 1996, Digital print accessed 27 March 2024. https://www.ltmuseum.co.uk/collections/collections-online/artwork/item/2011-12601-part-7

Theories of Representation

“There are drawings that register in the uncertain pressure of the pencil, how the mind crept uncertainly from point to point. Other hands dashed or swept confidently around. Many hands hovered tentatively above the paper, and then sketched doubt or question in the air before descending to make the mark. Elderly hands trembled the pen across the paper. In every case the line traced a thought, despite differing levels of ease with the concepts of ‘drawing’ and ‘network’” 25

Artist Helen Scalway compiled a mapping project aiming to reveal the ‘personal geographies’ 26 of different users of the London underground, approaching passengers in stations and asking them to draw a map representing ‘their’ underground. The compiled layering of their drawings is an interesting example of how personal drawings can be combined. On first glance it appears to fall into the trap of over collectivising experience, that is to say by combining all of the drawn maps it hides the detail and nuance that lies in each individuals document and results in something complex and unwieldy. However, if we consider it as a visual piece, not communicating the particulars of each hand’s work but the thought and collective conscious of many users, it conveys a very different outcome. The absence of defined structure suggests a lack of uniform thought or certainty around the spatial layout of the underground.

25 Helen Scalway, ‘Travelling Blind’, accessed 27 March 2024, https://helenscalway.com/travelling-blind/.

26 Helen Scalway, Travelling Blind, 1996, Digital print, 20 x 25 cm, London Transport Mueum, London, https://www.ltmuseum.co.uk/collections/collectionsonline/artwork/item/2011-12601-part-7.

Whilst the marks all seem to be made from a similar pen, the diversity in line; some angular and rigid, others carefully curling and dynamic, renders the multiplicity of experience and perception clearly to the viewer. This exemplifies the complexity of the composite map-maker’s task, but also the opportunities for expression.

Where Scalway’s piece exists as a process of engagement and then curation, Irving and Moss’s project Imaging Homelessness in a City of Care, referenced in Chapter II, is an example of collated participant mapping formed into a composite map, by the artist Lovely Jojo 27 Translating the sensitive documents created by their participants into one complete map is a difficult task. However, as these elements took the form of geographically related text, the artist was able to transfer the mappers’ dialogues directly to the final work, in a manner that hopes to sustain the agency and ownership to the original mapper.

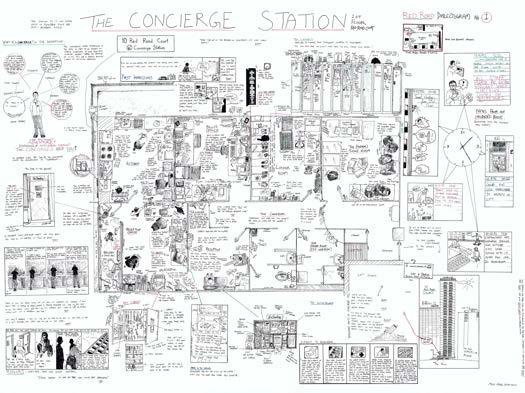

Figure 19: Mitch Miller, The Concierge Station (Red Road, Glasgow), 2009/10, Pencil and Ink on mountboard Accessed 10 April 2024. https://www.dialectograms.com/portfolio-item/the-concierge-station/

Another researcher representing multiplicity of spatial experience through what may be considered ‘social text illustration’ 28 is Glasgow based researcher Mitch Miller. Miller engages in spaces and communities through a practice of ethnographic research over sustained periods, which he then represents in notated and illustrated diagrams entitled ‘dialectograms’. Miller’s methodologies of visual representation to authentically document

27 Irving & Moss, Pg 270-273

28 Mitchell Miller, ‘An unruly parliament of lines: dialectogram as process and artefact in social engagement.’ (PhD Thesis, Glasgow School of Art, 2016), P g 16

the stories of the users of the spaces is highly valuable, as is his consideration towards the process of distilling field research into one artwork.

Miller recognises choices such as using the birds-eye view to lay out his drawings, with its implicit power and lack of quotidian street level grounding29, citing theories of ‘totalising’ representation as recognised by Michel de Certeau in The Practice of Everyday Life 30

“I’ve always thought the birds-eye view depends what type of bird you’re talking about”, Miller counters, “pigeons, for example”, “…pigeons know where the kebabs and the chips are”31. Miller’s approach therefore is to play with the ‘tensions’ between birds-eye and ground level perspectives in his work, using this balance of representations to draw out understandings from each other. A technique also documented in the work of Mark Bradford and Julie Mehretu by Kathryn Brown32 Brown compares both artists’ use of traditional cartographic grids and viewpoints offset against vignettes and collages that relate to the streetscape experience.

Bringing these reflections and mapping results into one compiled map was my initial goal for the later part of this project. However, as I have reflected, the diversity of mapping methodologies means that distilling the visuals into one piece would lose the personal narratives behind each drawing. Reflecting too on critical theories around cartographic culture, the need to totalise and compile experience can be problematic Perhaps then the best approach is to accept the total subjectivity of each mapping gesture, allowing them to sit apart, so that communication and collectivity happen as the viewer sees them together In this manner, I developed three of my own visual works, responding to the maps of others and my own findings, to stand as ‘gestures’ towards how the space might be represented.

To bring these findings into a method of compiling a leading image requires reflection on the protagonists in each mapping exchange, and consideration of how these transform into visual gestures of experience. The two labels of definition taken from the participant mapping, of narrative processes on one hand and spatial movement on the other, are often at odds with each other in the sources researched. Perhaps this suggests a requirement for focused communication to achieve a successful elegant visual. Where gestures of holding are our protagonist, what is required of a map to communicate this experience? There is a dynamic energy to such an experience that would demand the same in a graphical representation, perhaps a conceptual diagram of movement, however feeling the tools in your hands is a sensory groundlevel experience that surely requires narrative and grounding for an honest portrayal?

29 Ibid., Pg 14

30 Michel de Certeau, "Walking in the City." In The Practice of Everyday Life, tans Steve Rendall (Berkeley: University of California Press. 1984), Pg 93

31 Mitchell Miller, 2020. “Dialectograms by Mitch Miller: CITY Journal”, City Journal. 9 December, 2020. Online lecture, 23:26 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nGJzjDPSENw&t=2736s.

32 Kathryn Brown, "The Artist as Urban Geographer, Mark Bradford and Julie Mehretu." American Art, 24 (2010), 100-113.

Photographic map

Returning to explorations of balancing the experiential and the cartographic, I began an initial mapping gesture of photographic collaging, borrowing themes from Tschumi’s Manhattan Transcripts Dynamically drawn overmarks suggest Debord-esque transitionary spaces and perceived boundaries, linking silhouetted hands operating, moving and turning elements within the map. The arrangement of photographs suggests a degree of spatial organisation, however the irregular use of scale amongst the images communicates a more interpretative, psychogeographical approach. These vignettes and collages, in a similar way to Mehretu and Bradford’s work, bring the tactile nature of the space into the foreground of the map, allowing the geographical to exist as a subtle backdrop.

Figure 20: Tom Matthews, Print Studio Photographic Map, 2024, Digital collage

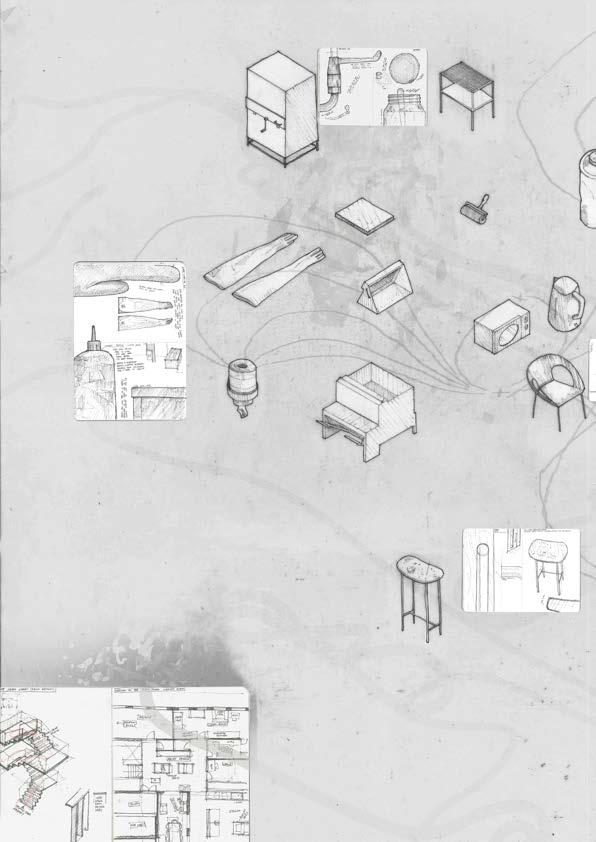

Object map

Returning to Serres’ ‘common edge’ 33 between object and user is a methodology for grounding maps in the thinking hand In this way, Rinako Sonobe’s Instagram feed cataloguing print studio objects collected from across the globe becomes a ground-level mapping of the histories of these well used objects by the many hands that know them 34. Removing objects from their context to suggest or question their surrounding activity relates also to the author’s work Street Furniture 1:16, an etching depicting a damaged street bench on Sauchiehall Street. Traditional architectural hierarchies of wall and built form are subverted, and instead space is organised around objects. Research documenting spatial perception as directly informed by the actions and activity we engage with in space highlights an interesting psychological angle to this idea. This is demonstrated by Witt’s study into the way perceived distances from objects can vary, depending on the viewer’s knowledge of the object, or whether they are holding a tool to further their reach 35 .

Developing this drawing was a result of studying equipment referenced in the mapping of Print Studio participants, and the field sketches from my notebook. Scale, orientation and location on the page vary between object, taking cues from the language and layout of the photographic map. However, this drafted document lacks the fiction and drama of my over-drawn diagrams, existing more in the realm of an orthographic architectural representation.

21:

Sonobe (@rinakosonobe02), Instagram photos, 20 January - 17 February, 2023. https://www.instagram.com/p/CyCDRAKoL-V/.

33 Serres, Pg 80

Etching and aquatint.

34 Rinako Sonobe (@rinakosonobe02), Instagram photos, 20 January - 17 February, 2023. https://www.instagram.com/p/CyCDRAKoL-V/

35 J. K Witt, " Action’s Effect on Perception." Current Directions in Psychological Science, 3, (2011), 201-206.

Figure

Rinako

Figure 22: Tom Matthews, Street Furniture 1:16, 2022,

Figure 23: Tom Matthews, Glasgow Print Studio Object Map, 2024, Pencil on tracing paper.

This growing collection of maps, and the processes and experiences of forming them, have been invaluable in analysing the practice of drawing space. This simple task connects with such an intrinsic quality of existence, communicating nonverbally how we inhabit space, and it is a reminder of the power wielded by designers, surveyors and cartographers.

In concluding this project with a single visual work, it is important to return to themes explored throughout the study around totalising representation and agency in map making. As reflected in chapter II, the practice of mapping your world is deeply personal and collating multiple maps made in this way is a complex task. Had the participatory exercise had a more quantitative control to the brief and output, perhaps this stage would be a simpler process of filling in information into a visual framework formed by the artist. Exploring this hypothetical outcome I created a layering diagram, tracing the movements and interactions in each of the participant maps, presented as lines and ‘X’s, to imagine how this might inform my final mapping task. Allowing myself this disturbance to maps made by others could feel problematic in the context of a de-centred mapping practice, however, accepting and emphasizing this as a map that seeks to address the communal without claiming to speak for it, is how I have approached this final work.

Figure 24: Tom Matthews, Participant Maps Collage, 2024, Digital Collage.

Figure 25: Tom Matthews, Gestures of mapping in Glasgow’s Print Studio, 2024, Digital collage.

Conclusion

Reflecting on this research reveals learned insights into how to approach qualitative mapping. The starting point of sketchbook documentation is perhaps stretching the accepted conventions of what may be considered a map, a central term I have consciously avoided defining throughout the essay. Considering these sketches as inhabited details of spatial experience however justifies their place alongside more conventionally laid out cartography. The core argument of this section of research is in promoting spatial communication that is deeply personal and subjective. If we see maps as the language of conveying spatial experience, restricting the lens of what we consider a map is also restricting the opportunities for authentic dialogue. Bringing this from the personal to the participatory supports the critiqued conventions of visual grammar and organisation that have developed around mapping. Although problematic in their lack of critical mainstream analysis, their nodes and folds have developed out of a need to create a communal language to share and understand. As seen in Chapter II, visual documents communicating in different methodologies and layouts are more complex to relate and compare, however they allow their authors a freedom of expression that is vital for deeper understanding of each other’s experience.

Concluding then in reflection of these final gestures of mapping, the creation of our own mapping tool kit is perhaps gesturing in the right direction for spatial communication that is both deeply personal yet communicative. This can be seen throughout the developed visuals intertwining object, scale and movement, all stemming from a deep consideration of the way an environment is felt and held. Focusing these visuals around sites for connection is how this study has brought the individual and communal together, not as a document of objective representation, but a gesture toward the experience of communality.

Figure 26: Tom Matthews, Print Studio Sketchbook Page 6-7, 2024, Pen and coloured pencil on paper.

Table of Figures

Figure 1: Rinako Sonobe (@rinakosonobe02), From February 2023, at @borch_editions. One of my favorite paths from my second sketchbook. Instagram photo, August 9, 2023. https://www.instagram.com/p/CwHqESioV5X/ 3

Figure 2: Rinako Sonobe (@rinakosonobe02), The "choreography around the press" at @hfatelierdegravura in May in São Paulo, Brazil. Instagram photo, October 5, 2023. https://www.instagram.com/p/CyCDRAKoL-V/. 4

Figure 3: Tom Matthews, Glasgow Print Studio Sketch floorplan, 2024, pencil on tracing paper. 5

Figure 4: Tom Matthews, Print Studio Sketchbook Page 8-9, 2024, Pen and coloured pencil on paper. 7

Figure 5: Tom Matthews, Print Studio Sketchbook Page 21-22, 2024, Pen on paper. 8

Figure 6: Tom Matthews, Print Studio Sketchbook Page 4-5, 2024, Pen and coloured pencil on paper. 8

Figure 7: Tom Matthews, Print Studio Patina Collage, 2024, Digital Photographic collage. .................................................

Figure 8: Bernard Tschumi, The Manhattan Transcripts, 1976-1981. Digital Image. Accessed 3 April 2024. https://www.tschumi.com/projects/18/

Figure 9: Adele Irving and Oliver Moss, Participant Maps, 2014, Digital Image. Accessed 2 February 2024, https://esrcimaginghomelessness.wordpress.com/participant-maps/

Figure 10: Niall McLaughlin and Yeoryia Manolopoulou, Social Drawings, 2016, Pen on paper. accessed 14 February 2024, http://www.losingmyself.ie/. 12

Figure 11: Glasgow Print Studio Member, Participant Map B, 2024, Pen on Paper.

Figure 12: Glasgow Print Studio Member, Participant Map A, 2024, Pencil on Paper.

Figure 13: Glasgow Print Studio Member, Participant Map C, 2024, Pencil on

Figure 14: Glasgow Print Studio Member, Participant Map D, 2024, Pencil on Paper. .......................................................

Figure 15: Andrew Degraff, North By Northwest, 2017, Gouache on paper. accessed 20 February 2024. https://www.andrewdegraff.com/moviemaps#/north-by-northwest/

Figure 16: Guy Debord, Guide psychogéographique de Paris, 1957, Lithograph. accessed 3 March 2024. https://collections.frac-centre.fr/auteurs/rub/rubinventaire-detaille-90.html?authID=53&ensembleID=135 15

Figure 17: Tom Matthews, Palette Knives, 2024, Digital photograph. 16

Figure 18: Helen Scalway, Travelling Blind print no 5, 1996, Digital print. accessed 27 March 2024. https://www.ltmuseum.co.uk/collections/collections-online/artwork/item/2011-12601-part-7 17

Figure 19: Mitch Miller, The Concierge Station (Red Road, Glasgow), 2009/10, Pencil and Ink on mountboard. Accessed 10 April 2024. https://www.dialectograms.com/portfolio-item/the-concierge-station/ 18

Figure 20: Tom Matthews, Print Studio Photographic Map, 2024, Digital collage. 20

Figure 21: Tom Matthews, Street Furniture 1:16, 2022, Etching and aquatint. 21

Figure 22: Rinako Sonobe (@rinakosonobe02), Instagram photos, 20 January - 17 February, 2023. https://www.instagram.com/p/CyCDRAKoL-V/. 21

Figure 23: Tom Matthews, Glasgow Print Studio Object Map, 2024, Pencil on tracing paper. 22

Figure 24: Tom Matthews, Participant Maps Collage, 2024, Digital Collage. 23

Figure 25: Tom Matthews, Gestures of mapping in Glasgow’s Print Studio, 2024, Digital collage. ..................................... 24

Figure 26: Tom Matthews, Print Studio Sketchbook Page 6-7, 2024, Pen and coloured pencil on paper. ............................ 25

Bibliography

Berger, John. 2005. Berger on Drawing. Cork: Occasional Press.

Brice, Sage. 2023. "Critical observational drawing in geography: Towards a methodology for ‘vulnerable’ research." Progress in Human Geography 0 (0).

Brown, Kathryn. 2010. "The Artist as Urban Geographer, Mark Bradford and Julie Mehretu." American Art 24 (2): 100-113.

de Certeau, Michel. 1984. "Walking in the City." In The Practice of Everyday Life, 91. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Debord, Guy. 1957. Guide psychogéographique de Paris. Discours sur les passions de l’amour. Lithograph, 595 × 735 mm.

Degraff, Andrew. “Cinemaps”. Accessed 11 February 2024. https://www.andrewdegraff.com/moviemaps.

Flusser, Vilém. 1991. Gestures. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Henry, Clare. 2022. Glasgow Print Studio Celebrates 50 Years Of Printmaking – Clare Henry. Accessed 03 23, 2024. https://artlyst.com/features/glasgow-print-studio-celebrates-50-years-printmaking-clare-henry/.

Henry, Clare. 1993. The First 21 Years - Glasgow Print Studio. Glasgow: Glasgow Print Studio.

Herrmann, Nicholas. 2021. "Drawing Matter: In Search of an Honest Map." February 22. Accessed February 15, 2024. https://drawingmatter.org/in-search-of-an-honest-map/.

Ingold, Tim. 1948. Lines : a brief history. London: Routledge.

Irving, Adele, and Oliver Moss. 2018. "Imaging Homelessness in a City of Care – Participatory Mapping with Homeless People." In This Is Not An Atlas, 270-273. Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag.

Jefffries, Michael J, and Jon Swords. 2015. "Tracing postrepresentational visions of the city: representing the unrepresentable Skateworlds of Tyneside." Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 47 (6): 1313–1331.

Kuschnir, Karina. 2011. "Drawing the city: a proposal for an ethnographic study in Rio de Janeiro." Vibrant Virtual Brazilian Anthropology 8 (2).

Matthews, Tom. 2021. Counter Currents: A journey down the river Don through six counter-cartographies. Undergraduate Thesis , University of Sheffield.

Matthews, Tom. 2021. Daily sketch Journal.

McLaughlin, Niall, and Yeoryia Manolopoulou. 2016. Loosing myself. Accessed 02 14, 2024. http://www.losingmyself.ie/.

Miller, Mitch. 2020. Dialectograms by Mitch Miller: CITY Journal. City Journal. Accessed October 3, 2023. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nGJzjDPSENw&t=2736s.

Miller, Mitchell. 2016. An unruly parliament of lines : dialectogram as process and artefact in social engagement. Thesis, Glasgow: Glasgow School of Art.

. 2018. "Inner City." Glasgow: Glasgow Museum of Modern Art (GoMA).

Nancy, JL. 2013. The Pleasure in Drawing (Trans. P. Armstrong). New York: Fordham University Press.

Padrón, Ricardo. 2007. "Mapping Imaginary Worlds." In Maps: Finding Our Place in the World, edited by James R. Akerman and Robert W. Karrow Jr., 255-87. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Pallasmaa, Juhani. 2009. The Thinking Hand, Existential and Embodied Wisdom in Architecture. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

Petherbridge, Deanna. 2008. "Nailing the Liminal: The Difficulties of Defining Drawing." In Writing on Drawing, Essays on Drawing Practice and Research, edited by Steve Garner, 27 - 41. Bristol: Intellect Books.

Reeves, Philip. 2010. Finding equipment and importance of the workshop (09 15).

Scalway, Helen. 1996. Travelling Blind.

. 2011. Travelling Blind. Accessed 03 27, 2024. https://helenscalway.com/travelling-blind/.

Serres, Michel. 2016. The Five Senses: A Philosophy of Mingled Bodies. London: Bloomsbury.

Rinako Sonobe (@rinakosonobe02), From February 2023, at @borch_editions. One of my favorite paths from my second sketchbook. Instagram photo, August 9, 2023. https://www.instagram.com/p/CwHqESioV5X/

--. The "choreography around the press" at @hfatelierdegravura in May in São Paulo, Brazil. Instagram photo, October 5, 2023. https://www.instagram.com/p/CyCDRAKoL-V/.

Torres, García Joaquin. 1943. "América Invertida (Inverted America)." Fundación Torres García, Montevideo. ink on paper, 22 x 16 cm.

Tschumi, Bernard. 2012. Architecture Concepts: Red is Not a Colour. New York: Rizzoli.

. 1983. "Illustrated Index: Themes from the Manhattan Transcripts." AA Files 4: 65-74.

Witt, J. K. 2011. " Action’s Effect on Perception." Current Directions in Psychological Science 3 (20): 201-206. Wood, Dennis. 1992. The Power of Maps. New York: Guilford Press.

Appendix A - GesturesofPersonalMappingsketchbook

Appendix A - GesturesofPersonalMappingsketchbook continued.

Appendix B - GesturesofParticipatoryMappingParticipant brief