Art as Activism

issue 4 April 2024

What Makes Art Good?

Your Guide to Writers Groups in Dublin

by Rachel Baum

by Rachel Baum

COVER

Meet Our Team!

Queer Fashion in the Mainstream

Art as Activism

A Cure for Homesickness

Fiction & Poetry

Fostering Community Through Poetry In Dublin and Beyond;

A conversation with The Madrigal Press

Interview with The Frustrated Writers’ Group

Should I start saying more, or saying less?

What to do in Dublin this month

What Coming-of-Age Cinema taught me about Growing Up

Romantic Ireland's dead and gone, It's with Netflix in the grave

Change Nothing and Nothing Changes; A Personal Essay

A Farewell Ode to Trinity College

How to Break Up with Your Fandom

What Makes Art Good?

Traversing the Cosmic Swamp with Wednesday

picks 4 6 8 10 14 16 20 22 24 26 28 30 32 34 38 40

Tn2

Queer Fashion in the Mainstream

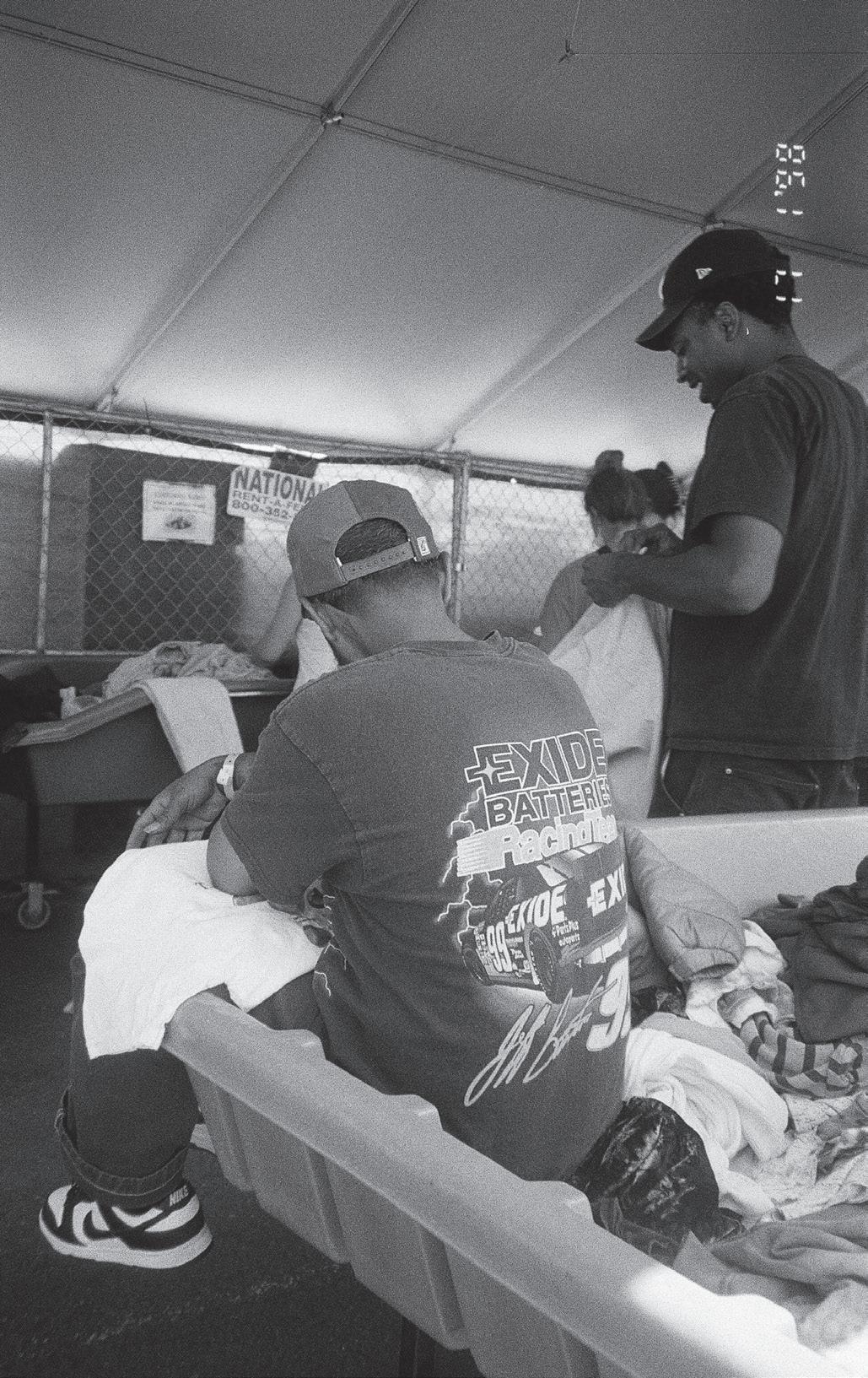

WORDS by Bo Kilroy

PHOTOGRAPHY by

Sophie Eastwood

Though most people outwardly say that queerness does not have an appearance, and that you cannot presume one’s sexuality by looking at them, this is hardly the case in our very perceptive society. Fashion and appearance have long been a signifier for sexuality, regardless of the reasoning behind it. Everyone is aware of these general stereotypes (lesbians wearing cargo shorts) and it is embedded in us no matter how evolved we want to be. Within the fast-paced and trend focused fashion industry, in the past decade or so, queerness has undoubtedly become an aesthetic. As the LGBTQIA+ community becomes more accepted and mainstream, so does the appearance of it. But when was it decided what queer fashion or straight fashion looked like? Or what makes a person appear as a certain sexuality? I feel that this all comes down to preconceived ideas of gender, and how far we as individuals separate ourselves from them through clothes.

The fashion industry has long been ‘infiltrated’ by the LGBTQIA+ community, beyond the notable contributions to it from queer designers, such as Gianni Versace and Tom Ford. Fashion is an expression of self identity, allowing you to present gender, nationality, and sexuality through clothing. Attire has historically been a method of rebelling against the societal standards assigned to your gender, even in subtle ways to avoid persecution. Oscar Wilde comes to mind, as his femininity didn’t just destabilise Victorian masculinity, but essentially created an image for what homosexuality looked like in the late 19th century. Dominic Janes, on the subject of Wilde’s trial, states that his outward flamboyance “…was to become a dominant stereotype of the homosexual for much of the twentieth century.” Wilde is known for wearing a green carnation that was apparently arbitrary and served to confuse people, and that got turned into a symbol of homosexuality. When queer people wear a certain style outside of what Western society has deemed acceptable at the time, it becomes queer itself. Lesbians in the early twentieth century, specifically those in the working class, began wearing trousers and generally masculine clothing in defiance of patriarchal standards, as well as simply needing clothes meant for physical labour. Hence this style was basically coined as belonging to the lesbian community, even if it was not entirely intentional. There was also a huge importance of fashion as an identifier; it has long served as a practical way to recognize another queer person or a safe space. In the latter half of the twentieth century, an earring on the right side was a signifier of queerness for gay men. It’s a subtle decoration that wasn’t feminine or ‘outrageous’ enough to completely

out someone, except to those who understood its significance. Even within queer spaces, there were certain style choices that indicated sexuality and sexual preferences. Carabineers were, and continue to be, a symbol of queerness on women, and whether it is placed on the left or right side communicates sexual roles. Fashion provides a vessel of expression for the LGBTQIA+ community, especially in societies that prohibit queer joy. It is important, I think, to recognise queer fashion as more than individualistic, but also to acknowledge how the community utilises clothing to come together. Although we are not past the need for hidden queer symbols, the alternative fashion movement associated with queerness has seeped into the mainstream in recent years. This can create issues in the world of queer fashion, that, through its mainstreaming, has been continuously whitewashed. Harry Styles has been notably celebrated for his gender fluidity on the red carpet far more than celebrities such as Billy Porter, who has been dressing in avant-garde fashion and opposing gender standards for far longer. This speaks to how queer fashion is often only accepted and praised when it’s seen on Eurocentric and conventionally attractive people.

The internalised fear of appearing queer has shifted somewhat and disrupting gender norms has been celebrated outside of the community. Social media has provided a platform for more LGBTQIA+ influencers and alt fashion to be showcased, so it is normalised to dress against societal standards regardless of sexuality. As a result, identifying queerness through fashion is now a little more challenging. As the male gaze and how we dress for it is further confronted, women’s fashion trends become less and less aligned with traditional Western femininity. Masculine attire, provocative and hyper feminine clothing, and generally traditional ‘alternative’ fashion that was once ridiculed in the everyday is now idolised. This revolt against tradition with fashion that was once associated primarily with lesbians, like the ‘anti-fashion’ movement of the 70s, has expanded. Dressing in a way that doesn’t fall under socially acceptable examples of femininity is freeing, so it’s understandable why many women, especially from younger generations, appear as stereotypically queer. Similarly, there are fashion trends that straight men take part in that bend the rigid rules of masculinity. Men wearing nail polish, for example, was something connected directly to the queer scene, or at least the alt scene. It is now a widespread phenomenon for all artsy students, along with moustaches, jewellery, and generally being well-groomed. This shift in a more androgynous approach to fashion is obvious in Trinity’s campus couture, where

FASHION

alternative styles are the most sought after. Masculine people wearing feminine clothing and vice versa, has been nominated the epitome of style, within the arts block at least.

On the flip side, it’s also common for queer people to feel pressure to dress according to how their sexuality is perceived. Appearance is often the first hint at someone’s sexuality, and queer people have historically needed to be aware of this, as no one wants to presume, or be perceived, wrong. This can be seen in mainstream fashion as Adrianne Lenker, the lead vocalist of Big Thief, is somewhat of a style icon with their masculine attire that is almost an ode to the cowboy-esque fashion of working-class lesbians. Their appearance has consistently caused assumptions around their sexuality, despite being opposed to defining it. I went around the arts block to ask people the question “Do you feel, or know, that your sexuality is presumed based on your appearance and style?”, to which everyone answered yes. I asked Katie Carr, a fellow student, why they thought their sexuality would be assumed and they specifically referenced their hair. After cutting it short, they found they received far less male attention, which was a benefit. From AFAB people I’ve spoken with, and in my own personal experience, dressing masculine or in any way alternative sets you apart from the male gaze. To the question of whether sexuality is presented through gender, Katie says that it can be, but it is more so an expression of gender identity, and the general alt movement, that creates a safe space for being queer. Stephen Flannery stated that “I think inherently queer people must question their identity more so than heterosexual people…. you have to do that introspective work of who you are, and you realise you don’t want to wear what everyone else is wearing, I think that is why alternative dress is linked with queerness.” The more someone dresses disaccording to their assigned gender, a.k.a. hyper feminine for those who are AMAB or hypermasculine for people AFAB, the queerer they appear. The presentation of gender and sexuality have been, inevitably, interlinked.

As our views on gender and sexuality become more fluid and understood, we become more secure in our identities. The fashion statements that would previously undermine someone’s sexual identity is now a trend and, generally, accepted in more spaces outside of exclusively queer ones. However, I don’t think that necessarily takes away from the significance of queer culture. Being able to present sexuality through subtle methods remains freeing and celebrative. Thoughtfully dressing in a way that I know will make it

clear to people that I’m a lesbian, and knowing that others are doing the same, gives me a great sense of community. The fact that gender expression is being considered across sexualities really just highlights the importance of queerness in the fashion industry, and this should be celebrated.

5

Art as Acticism

An Interview with Empower the Voice Dublin

From the first wave at the Botany Bay steps and the excitable introductions to gathering around an eclectic and bright living room with Esme Dunne and Grace O’Sullivan, two founders and core members of Empower the Voice Dublin, I am instantly swept into an atmosphere of ease, comfort and inclusivity. Aglow from returning from a previous art workshop, and as the sunlight beams upon us, the distinction between interviewer and interviewees is replaced by a feeling of friendship and belonging. At its core, this is what the non-profit organisation stands for. “A place to rest your bones”, as they so aptly relay in their Instagram bio, for all people of marginalised genders.

Dunne, a fourth year English student, prior to residing in Ireland was a member of Empower Her* Voice, a group which was set up in her school in the UK. Leading the club in her final year, the group was mainly rooted within school events ranging from talk series with teachers to selling t-shirts. Following school Dunne went on to become a director in the London branch of Empower Her* Voice, involving herself within summer internships and a multitude of events. When asked whether Dunne identified Dublin as in need of a community such as this, Dunne relayed how organically the group developed, from identifying that she herself needed Empower the Voice to friends expressing interest and finally to the realisation that she could provide her community with something. In November 2021 they held their launch party at Workmans, which was a huge success. From that point onwards the organisation has gone from strength to strength as part of the wider Empower the Voice while still “maintaining their own distinct identity”.

“...everyone in the room has common experience, but you don’t need to talk about it… there’s a level of understanding and knowing...”

Art and the act of creating have always been integral to Empower The Voice’s ethos whether through life drawing, jewellery making, painting or the creation of ‘scrap babies’. Detailing how art fosters a safe space, O’Sullivan, a fourth year PPES student, remarked upon the beautiful and peaceful energy it conjures for all “girls, gays and theys” in which no matter the skill level it is about taking the time to create. Explaining the structuring of the classes the two members describe how different friends lead each intimate class, most frequently the life drawing classes formatted to lead up to an exhibition. Both Dunne and O’Sullivan light up speaking about the classes as their “bread and butter”, a liberating experience with the former citing it as “a space where everyone in the room has common experience, but you don’t need to talk about it… there’s a level of understanding and knowing” in how “creativity cultivates connection”. The group made a conscious effort to focus upon art of all mediums for their community-based activities. Although social and night out events have their place, Dunne stated of their own organisation that “Dublin doesn’t need another DJ collective, and if it does it doesn’t need to be us”. Rather, their classes are marked by their restorative and easy nature.

Empower the Voice have become a prominent organisation within the Dublin scene for combatting themes surrounding sexual assault, harassment, and social injustice through the growth in their chalking campaign. It is “a creative way to amplify voices”, Dunne explained. Interestingly, it was the Molly Malone statue which acted as a catalyst

for what would propel this community to the forefront of the scene. One day, Dunne and O’Sullivan were sitting by Molly Malone when a person passed uttering that “she wasn’t as pretty in person”. Other than prompting initial anger it led to them chalking “groping isn’t good luck”, a reflection upon street harassment. As avid supporters of @catcallsofnyc, Dunne and O’Sullivan citied the page’s engaging use of protest to forge connection and activism as inspiration for the chalking. The conception of the campaign was consolidated with a chalking outside Wigwam which confronted the club with a horrible experience O’Sullivan endured. Walking me through her experience at Wigwam at a freshers event for TCD’s FashionSoc in October 2023, O’Sullivan was “groped by a man in the line”. Upon reaching the entrance O’Sullivan notified the bouncer of her experience yet was met with a complete lack of empathy or concern. Instead he responded with the question, “what did you do to instigate it?”.

This comment prompted outrage from her friends and those in the queue. The next day a friend was hit with microaggressions and unproductive conversation when she met with Wigwam to inform them of what had happened. Dunne and O’Sullivan remarked how this was a learning curve in the club process, one they initially had little knowledge of, with a lack of accountability often cited as a justification. Different fingers of blame were pointed over whether responsibility lay with promoters or with the club itself. This incident led to the first chalking and post on Instagram of O’Sullivan standing in front of Wigwam with the response of the bouncer chalked on the ground. Overnight, the organisation’s Instagram followers doubled. This was to be the launch of a new era of the organisation and their subsequent growth in Dublin. The power of social media led to the promoters of this event, Bodytonic, reaching out. Within a few days, Dunne and O’Sullivan set out to meet with them. They collectively laugh in reflection of their mindset entering the meeting and believing it would entail a tough and tiresome conversation of little progress. Instead, they were met with a receptive audience and belief in the incident which had taken place. The result of the meeting with Wigwam was the implementation of a late night safety officer, a position the organisation is extremely passionate about. O’Sullivan described how it is “so important to have within a nightclub one person whose sole responsibility is to ensure the safety of the people,” with Dunne adding the anointed person as having the “sole purpose” to “believe what you say, and to look after you after it happens”. The hope is that other nightclubs will implement a similar role, as their chalking sheds a light on numerous clubs around Dublin which have mishandled situations very similar to what O’Sullivan experienced that night.

“Just as they watch each other’s back whilst chalking, they do so in fostering a community rooted in offering a secure and safe environment.“

Remarking upon art as an effective medium of protest, Dunne explained how the chalking, unlike other artworks, is “not intrusive or damaging, bringing a level of permeance to something that happens in passing”. By taking art out of a traditionally institutionalised space through chalked street art, Dunne and O’Sullivan explained, results in the reclaiming of public space. Dunne stated how “claiming public space for something positive is really lovely, reclaiming the space after something has happened to you there, re-inserting yourself into something you shouldn’t

DESIGN

ART &

have been pushed out of”. For Dunne and O’Sullivan, the act of chalking itself is reflective of their emphasis on friendship and comradery. Just as they watch each other’s back whilst chalking, they do so in fostering a community rooted in offering a secure and safe environment.

When asked how public reception of their campaign, Dunne and O’Sullivan mutually agreed they were overwhelmed with the outpouring of support upon the Google form they set up for people to submit instances of sexual harassment they have experienced on the streets of Dublin. They described instances while chalking of people taking the time to stop and appreciate, some clapping, others commending them on their work. Most recently, Dunne described a man who positively shouted, “vive la révolution”. Disappointingly, yet unsurprisingly, there have been moments where public reaction has led to harassment. The most frequent instances have been times when they have been told to smile, with O’Sullivan telling the story of a man coming up and criticising their activism with the statement, “you need to smile, don’t be so angry”, a comment which they have said reappears again and again in the Google form submissions. Recently whilst Dunne was chalking in front of the Molly Malone Statue a group of young boys began to catcall her and shout verbal abuse. Overall, however, this has only inspired the organisation to continue their endeavours as the harassment only informs their opinion of the need for such a campaign as this.

The chalking campaign has not only created greater awareness of the culture of catcalling and harassment in Dublin but also allowed for introspection. Commenting on the normalisation of catcalling within society from a very early age, O’Sullivan stated that “there is a lot of forgiveness and empathy for people who do it at a young age but it’s not reciprocated the other way around, the support isn’t there”. This was in particular a response to the influx of young girls submitting incidents where they have been the victim of catcalling and sexual harassment, a sad reality which effects so many. Often catcalling is excused as a right of passage when one reaches a certain age, yet this is the very practice the organisation feels so passionately opposed to. Reflecting upon her own personal experiences Dunne explained how, before, she didn’t always fully understand the nature of catcalling, “thinking that I’m being complimented, because it’s not aggressive. But it doesn’t mean I asked for it either. And it doesn’t mean that it’s not creepy or uncomfortable”.

The organisation’s campaign has been the jumping off point for great opportunities. Recently, Dunne got the opportunity to speak on a Labour Women platform in which a wider demographic could be reached. Speaking on Molly Malone and the practice of touching the statue struck a chord with many women at the talk, Dunne explained. This has led the group to begin talks with Dublin City Council and thus launched a campaign with @tilly_cripwell called #leavemollymalone. The campaign aims to re-polish the statue to obstruct the visual beacon of the statue’s chest, to have a sign placed informing people of the history of the statue, and for tourist boards to discourage the practice of touching her breast. To those that argue that Molly Malone is just a statue, Dunne and O’Sullivan are obviously aware of this fact. But, as Dunne replied, the treatment of Molly Malone is representative of “behaviour which translates into real life,

the way we treat women and marginalised genders as objects, objectified and sexualised without their consent”. Even in the absence of the sexist connotations which surround the statue, it’s a strange practice to touch a statue’s breasts. While some defend it as an age-old tradition, Dunne and O’Sullivan debunk this excuse. They explained how Molly Malone was only unveiled in 1988 and that the groping is thought to have begun only within the last decade. Their campaign gained significant traction on social media resulting in the group joining forces with Mind the Gap Ireland, the first ever online anonymous story platform for survivors of sexual violence. This merging happened rather organically and is only in the primary stages. Dunne explained how “we exist in relation to one another and not separately”, with both herself and O’Sullivan hopeful of the new opportunities this merge will produce.

On the 22nd of March this year, Empower the Voice held ‘An Evening of Art and Conversation’ at the Fumbally Stables. Showcasing art from their art classes hosted throughout the year as well as art from various Dublin creatives, the evening spotlighted the intrinsic connection between art and their organisation. Featured artists included Amelia Greham, Lara Prideaux, Lauryn Creamer, Nicole Manning, Olive Jagha, Rukmini Kelkar, Shannon Ryan Kelly and Unyoung Cho. The profits from the event were in aid of Akiwda, a Dublin-based charity working to promote equality and justice for migrant women in Ireland. Three speakers presented including Trinity’s own Jenny Maguire, a co-organiser of Trans and Intersex Pride Dublin and recent presidential elect of TCDSU. Jenny spoke on her own experiences of sexual harassment as a Trans woman. Baisat Alawiye, a primary school teacher and advocate for EDI: Equality, diversity and inclusion in education and pioneer of Minority Teachers Ireland, spoke insightfully on how to be anti-racist, especially in the wake of the Dublin city riots. She also spoke on ethnic and religious minorities in the workplace. Poet and coordinator of public relations at Mind the Gap Ireland Tatenda Madondo sparked conversations surrounding race, equality and feminism. Unlike previous themed exhibitions, the first theme being the female gaze and last year focusing on empowering the body, this year had no theme; its broad nature led to the representation of a multitude of voices, art, and diversity of experience.

Speaking on the future of Empower the Voice, Dunne and O’Sullivan reiterated their dedication to continue the chalking campaign. The summer poses a hopeful opportunity for increased interactions with clubs and the implementation of late night safety officers. As Dunne noted, “the more interaction a post gets the more pressure is put on the club, the more they respond”. They also hope to further the growth with Mind the Gap Ireland and other projects currently in the works.

Empower the Voice Dublin and the work this organisation is pioneering showcases how art can be utilised for activism and the mobilisation of communities for societal change. To finish this article I would like to thank Empower the Voice Dublin for their existence, their dedication to those often voiceless and for the creation of a community which makes so many feel like they belong.

7

WORDS by Alice Carroll

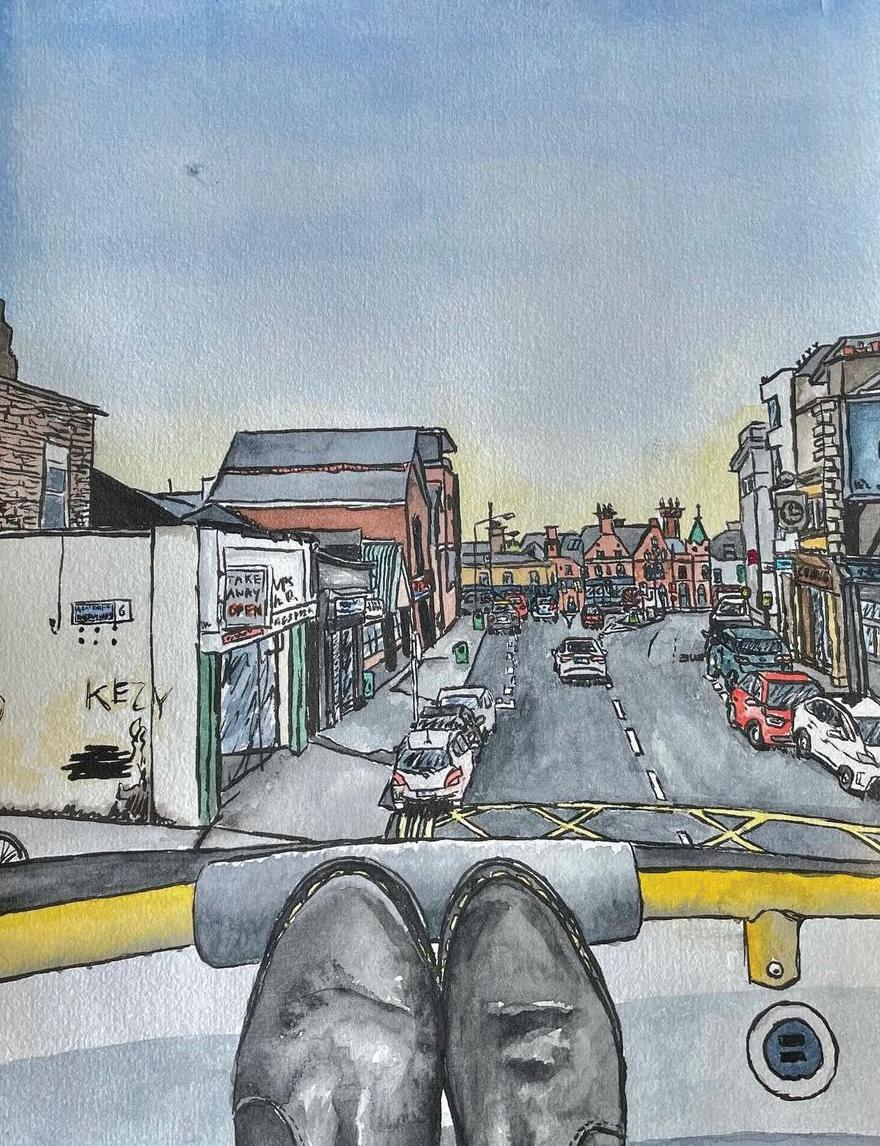

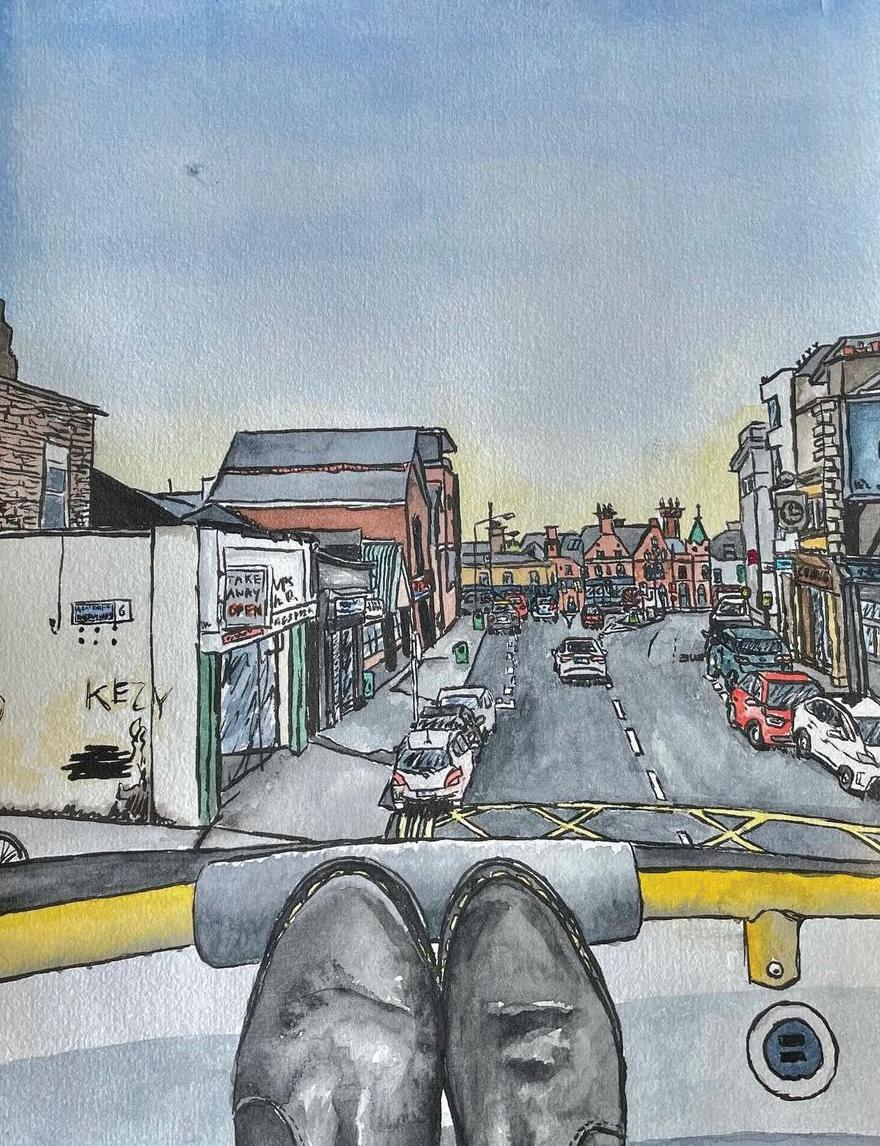

A cure for Homesickness

Isabelle Doyle speaks on leaving home, the comfort of the familiar, and the place of art in times of transition

Iwas sitting in the kitchen in my flat in Utrecht the other night talking to one of my flatmates about the highs of the past few weeks we have spent on Erasmus. After exchanging stories from nights out or hidden spots in the city, she refreshingly revealed that she was missing home, a sentiment I have been grappling with myself. I’ve only really confessed to these feelings on facetime calls or in voice messages to friends from home. Admitting to challenges on Erasmus can be difficult as you want to show you’re making the most of your time away. Yet, beneath the surface of initial excitement lies a period of adjustment, a hard transition from the familiarity of your hometown to the unfamiliarity of a foreign country, without the comforting presence of your close friends. This is the perfect recipe for homesickness. While the highs here have been so exciting and rewarding, there are quiet moments when the lows creep in. I have tried to ride through the lows by attempting to find pockets of familiarity in Utrecht. What I have come to learn is that there is really no fix for this other than letting the discomfort run its course until it inevitably passes, as it always does. However, I have found art to be one to be one of the biggest forms of comfort while going through this. It has opened up chances for connection in a new city and also a comforting nostalgia of home.

It truly is never a struggle to find Irish art and artists, and when it comes to themes of moving abroad we have an abundance to offer. As I navigate this experience myself, it has given me a sense of relief to cling onto books, music, poetry, or art about Ireland to evoke a sense of familiarity and belonging in the references to places I know and love, or even the familiar accents. Playing Irish artists such as CMAT or Pillow Queens when I’m cycling through the city and listening to their Liffey references almost makes me feel like I am cycling by the Quays of Dublin, which in reality, considering Dublin’s bike lanes, would be a terrible idea. Irish music truly has been a source of joy here in The Netherlands. I travelled with my group of friends to The Hague on St Patrick’s Day a few weeks ago as they were hosting a large festival. We proudly showed our knowledge of traditional tunes, celebrating songs that would not evoke nearly the same passion back home. We encountered a woman from Fermanagh while waiting in line for drinks. Our American friends attempted their Irish dancing, catching her attention. To our delight, she told us she was an Irish dancer, having performed in céilí bands since childhood. She kindly gave us a quick lesson in the basics of Irish dancing. In that moment, it not only evoked a sense of home, but also the beginnings of new one.

I think it is so important to hold the familiar with you when you are away, but I’ve come to realise the profound importance of embracing

everything that is new. Despite how I have made it sound so far, I am going beyond Irish art and spaces here. The Netherlands is known for being a culturally rich country and it really has not disappointed. From an abundance of art museums to vibrant street art and a myriad of cultural events, the city is full of creativity, a value deeply ingrained in its essence. Live music is a constant joy here with gigs happening every night of the week. The constant flow of cultural festivals, like the recent celebration of queer history, only adds to the vibrancy here. I hunted down the talks and panels in English and learned so much about queer culture in the Netherlands through the art on display. Truly integrating with a new environment means venturing beyond the tourist traps and seeking out the cultural heart of the city. While this has proven more challenging than anticipated, I am searching every day for the special spots similar to the ones that I have mapped out in Ireland. The few places I have been have offered me not only a sense of community but have challenged and expanded my view on what art and those spaces can look like.

Something I found to be the most helpful is the art people gave me before I went on Erasmus. I was given letters, poems, and postcards, and now my room has been decorated with what feels like pieces of loved ones from back home. Even my mother gave me a calendar with photos of the Irish Sea. I have also found writing for loved ones to be so helpful. While Facetiming and texting offer an instant connection, there is something special and intimate about sitting down and taking the time to write a message to someone you love. It can bring you out of your head and help you feel connected in a different way. Despite the challenges Erasmus has brought up, it has given me new perspectives I never would have gained from staying at home. It has made me appreciate my friends in Dublin and the city in a new way, as I almost couldn’t see the special parts of my life there as they blended into my daily routine. I hope to now hold all the joys of travelling and the warmth of home, using art as a way to carry that warmth and prepare me for the adventures that lie ahead.

WORDS by Isabelle

PHOTOGRAPHY by

Doyle

Giulia Vettore

ART & DESIGN

9

FICTION & POETRY

Heartsick Mortar

By Dylan Breheny

What do you think it’s like to be a house?

That’s a trick question. You yourself are a house to many things, not least of which is the brain at home in that skull, sitting in that skin, reading this now. You’re a house to the microbes in your gut, on your skin, stuck between your teeth. But you probably don’t think about those very much, so I suppose being a house isn’t like much of anything at all.

So why can’t I stop looking at him?

I first noticed the architect a few seasons after he had arrived. It was just before the thaw, when my piping was frozen and the vents in the street steamed with the breaths of the city. I had been little loved over the years, an old administrative office in the city’s historical district. People shuffled in during the day and each evening left me empty and cold, besides the occasional family of owls in the rafters or rats running riot beneath the floors. That’s the funny thing about the stuff inside you, like your brain or your marrow or the things that call you home – you might not notice when they’re there, but you certainly will when they are gone. The Architect stayed long hours though, worked late into the night. He was there to oversee my repair, I think, to make me ‘modern.’ He loved the word. Modern. Modern like the towers that sparkle against the sky – even brighter during the night when they outshine the stars. The architect was there to make me beautiful and loved again. I listen, as the workers hang their coats against the humming radiators and walk wet footsteps over the flexing wooden floors. Soon they file into their offices as the talk is hushed, replaced by the sounds of productivity, of muted questions and typewriters clicking. Not the Architect though. He walks my long forgotten halls, drawing measurements along the walls, and I can hear him tally numbers below his breath. I can hear him building castles in his mind. He finds the places where the mould has eaten my walls from inside, the places where the piping has burst with the ice. He shines a flashlight into the boiler room and lets out a shout when the rats squeak and flee. And then I hear him laugh at his own silliness, to no one but himself. Over the hours he maps me from inside, pressing his hands to the walls.

I wonder if this is what it’s like to be a home, where the workers run so eagerly each night. I watch the towers on the horizon and wish I could be a workshop, or a boarding house, or anything besides what I am. But it’s alright. The architect knows me inside and out; he will make me beautiful, he will make me loved, will make me modern. The workers invite him out to a public house one night, and he smiles and declines – he has a deadline to meet, he says. And the rest of the night I watch him, he moves beneath misted windows, and I don’t even think once about the towers that sparkle and shine out there in the city.

The season passes. The halls echo, bulbs buzz, the door swings and leaves gentle indents against the walls. The Architect chatters, too fast for me to understand, except for the words that appear again and again: words like demolish, refurbish, new wing, foundations, funding, funding, funding. He falls asleep over his maps one night and forgets to leave,

until the weak morning light wakes him up and he groans to himself as he rolls up his papers. The season changes and every morning the workers rise earlier. One morning the Architect arrives earliest of all, and with him many others, stern and tireless people who spend the day clearing out my rooms, chalking marks along the walls, wheeling imposing machines into the street outside. I feel motion, attention, purposeful and meaningful activity not at all like the workers and their scribing and their papers. A wooden fence is erected to hide me while I am remade. Everything has aligned for this. I feel scared but I hush that fright because I know that the Architect loves me. He will make me beautiful.

At daybreak the following morning, they knock out the first walls. I feel my foundations quake as brick and mortar is sledged apart. The architect conducts the builders from outside, his plans spread over benches. Something about foundations, foundations, funding, funding, unsound, unsafe, rebuild, refurbish. I feel empty air gasp into me as the walls fall. I feel pipes pulled free gutted from the ground. I feel the shake of steps and hammers and plywood as it is hammered into place. Those old rotten bricks and musty walls will be replaced. I will be fond of myself. The workers whistle, as they strip the insulation from the walls, like marrow and they say words like foundations, foundations, delays, delays, funding, funding.

One day they don’t turn up at all. But that is fine. Wind and rain continues to worm its way through my walls, wearing them away to be replaced by bright new bricks and plaster. I welcome the vermin, the bats, the rain that rots away those wooden floors, because soon I’ll be fond of myself, like the Architect dreamed me up. One day the builders return; they climb into those imposing machines, built to tear me down, and simply drive them away. The door is locked, a sign placed on it – and I don’t know what it says, but I can at least hear the voices that murmur: foundations funding, postponed, what a pity.

And then I hear nothing at all. Noone clicks open the door, or stamps their cold feet in the hall, noone snarks or suppresses a laugh. There is no architect, drawing fine lines by the light of his lamp and muttering to himself. It’s funny, the things you only notice when they’re gone. The seasons change, and my edifice stares out at the bright lights in the city sky. At first I wish he was here, but the longer I’m alone the wishes get smaller, less wishful. If I could even just know where he was. If I could even know what he’s doing. Is he happy? Is he dreaming up the towers that decorate the sky? The seasons change, and green shoots push through my foundations. Water pools in my basement, wind blows through my empty frame. People say things in passing as they step by on the street. Sometimes I try to listen, and imagine that one of the voices belongs to one of the workers – or even the Architect? But it’s ridiculous, as ridiculous as thinking the spiders in your room remember your face. The sky turns. The frost thaws. My walls fall away. I almost think I’m dreaming when one day, someone slips through the wooden fence, and walks up the overgrown steps, and drops their bag to the ground. There is hardly anything left of me now, but foundations, and a few bare brickwork walls. For the first time in so long I feel attention, as the girl regards my dirty, ruined, loveless walls. She pulls a metal aerosol can from her bag, rattles it in her hand, and holds it to the wall. I see her mumble something beneath her breath.

She starts to paint.

Soft Sermons for Spring: IV

By Ella Flynn

In the summer we build castles Born of soft brazen granules

This could be glass

But time passes softly, quickly, And sand sinks again to the ground.

Come winter, on time and perfect, Aware, maybe, of the clauses that govern, Of the innocence of the first mourning; The death of the year.

Building with clothed hands men from soft snow, Adorning their chill with things that keep our skin warm, Watching them stand like structures of spirit Only to melt away.

On the beach in July

We want to stay forever

And make ourselves a home.

A castle with a moat and a bridge and a thousand soldiers keeping safe what is worthy of protection.

The first day of spring, And the only snowfall of the lonely winter. Perhaps we want to build a friend out of that pale grief, Perhaps we take your branch and give the final touch, A handshake,

To leave what has come to pass, To gift company to something that was cruel and desolate, Or really just an innocent thing dying.

All your sorrow and all of your pain will melt away now. You can start the plans for the pergola and the patio.

11

PHOTOGRAPHY by Giulia Vettore

Bucket of Blood

By Joe Prendergast

TW: Sexual Content

When they threw that bucket of blood over Martina, I was in the garden centre with my mother. I was helping her decide between blue or indigo hydrangeas – although, later on in the week, after a period of prolonged silence on the patio, Mom pondered aloud whether there was any great distinction between the two shades after all – when my phone rang.

“Hi, is this Adam?” It was Rick, Martina’s husband. Rick had a patchy beard, grey eyes and a permanently wet mouth, presumably slicked at regular intervals by an invisible pink tongue. One night at the lake house, we found ourselves alone together. Rick was very drunk and told me he found me very attractive. He placed his right hand on my crotch, began to cry and excused himself curtly. I finished my brandy alone in the kitchen and listened to him fervently masturbating in the bathroom. Since then, he came to fewer dinners and spent most of the times I visited their apartment playing with the two Pomeranians.

“Yeah, hi, it’s me,” I said. “Is everything alright?”

There was a beat of silence while Rick formulated an answer. “There’s been a sort of - well, incident.” He paused. “With Martina.”

That summer was one marked by incidents with Martina. In fact, having worked for her for almost three years, my entire life was starting to become a series of incidents with Martina. “What happened? Is she OK?”

“She’s fine, she’s just - a little shaken. Listen, she’s -” His voice went distant then. “Yeah, I’m calling him now, honey. Yes, he’s just - Yes, I’ll tell him - I’ll - ”

I watched my mother question a young shop assistant with a green lanyard whose tag read, “Hi! I’m Kevin. Ask Me Anything!” In spite of his apparent eagerness to help, he maintained a distance from my mother usually reserved for large and dangerous animals.

Rick was back now, and quieter. “Listen, Adam, these - I don’t know, these crazy activist people, these - I mean, nutjobs, they came up and got all in our face - saying all this crazy shit like - like calling her a murderer, a psycho - a creep and stuff like that. Like, really fucking angry. And - one of them had this bucket of blood, like - what the fuck, man? A bucket of blood? And they threw it on her, just like that, and ran off - people were videoing, man, it’s fucked.”

At this point in Martina’s career, it was out of the ordinary for people to throw buckets of blood on her, but now, I’m lead to believe it’s one of the tamer protests she’s met with. One particularly memorable sign outside the opening of her show at the San Diego Cultural Centre read, “Martina Roderick: Crazy Pig Murderer Bitch.” I took a photo of it with my phone and sent it to Rick. He sent back a thumbs-down emoji. It was the last time I spoke with him. “Anyway,” Rick continued, “we’re doing this restricted intimacy thing right now, and so she’s – we’re –asking for you to come and help. I’ll - uh, I’ll pay for your

Uber, and everything.”

Martina’s apartment was on the fourth floor of a building that used to be a Quaker meeting house. The elevator was broken, so I took the stairs, and was sweaty upon arrival. Rick opened the door. “Hi,” he said apologetically. “She’s just in the bathroom. I’ll just be - just holler, if you need anything.”

Down the hallway to the left, the bathroom door was ajar. I could hear water running inside, hot and steamy. “Martina?” I called in. My voice sounded strange and girlish.

Martina gave a little gasp. “Oh!” she cried. “You’re here. Come in, come in -” I heard her turn the water off.

The bathroom was foggy and the smell of the blood made my nose crinkle. Martina was sitting in the tub, scrubbing vigorously at her leg with a swiftly darkening loofah. On the side of the tub perched a box of sugared donuts. “Rick bought them for me,” she offered as explanation.

I put the toilet seat down and sat on it, facing her directly. I had seen Martina naked before, but I had never been this close to her bare body. The dried blood was matted in her hair, and there were dark red stains down her neck and the top of her breasts. Her clothes lay on the floor in a pile.

“It’s fucking ridiculous, Adam,” she announced, continuing to scrub. “I mean, what kind of fucker just does something like that? It’s sick. That’s what it is.”

I nodded in agreement, but said nothing. “Martina, why couldn’t you ask, you know, Rick to help you with this? I mean, he was there, right?”

She sighed. “Rick’s therapist advised that we do something called restricted intimacy. So, we’re not exposing our bodies as readily to each other, or having sex as much. Things like that. He seems to think,” she said, adjusting her position slightly to get a better run at her calves with the unfortunate loofah, “that it’ll help with some - problems we’ve been having. Can you do my back?”

Martina manoeuvred herself into position, and held out the loofah. I got off the toilet seat and knelt down before the tub. I took the loofah and waited while she moved her matted curls off her back. I began scrubbing. It reminded me of cleaning the floor of the café I worked at, right before I first met her. For some reason, I liked to do it by hand, crouched on all fours, until the smell of the chemicals went so far up my nose that I got dizzy.

After her back, I scrubbed the backs of her legs and the soles of her feet methodically, in near-total silence. Martina let the water run again for a while, for no particular reason. “I’m sorry to make you come in on your day off,” she said. “I hope it wasn’t too much of an inconvenience.”

“Not at all,” I replied, and smiled. “Happy to help.”

Martina tried to smile back, but it ended up being a sort of grimace. This was often the case with Martina. She insisted that I have a donut, and so I took the last one in the

box. The sugar stuck to my wet fingers.

The taste of these particular sugared donuts made me think of an October morning after I first started working at Martina’s studio, when Rick came up with a box of them for her. She wasn’t there, so we smoked and ate them on the fire escape. We split the final one. He asked me to take my clothes off and took pictures of me from different angles with the camera on his iPhone. He texted them to me, alongside the link to a YouTube video explaining how to set up a Nutribullet. His next text read, “Sorry – didn’t mean to send Nutribullet video. Rick.”

I was hungry, not having eaten anything yet that day. I proceeded to fit as much of the pastry into my mouth as I could muster. As I was doing this, Martina, still in the bath, fixed her gaze directly at me. “Adam,” she pronounced.

I mustered a grunt in response.

“I’m - letting you go. Firing you. I mean to say, you’re - not my assistant anymore.”

I swallowed half of the donut and felt it scraping down my throat. “Oh.”

“I just - I don’t think you’re a good fit for me any

longer. Or my work. I think you’d be better with anotherperson. Artist. Whatever.”

“Martina,” I said, rising from my position on the toilet. The warmth and wetness of the room made this a difficult task. I put my hand out onto the cold wall tiles. “I really, I-“

“I know about Rick,” she interrupted. “I know about - you and Rick.” Her voice faltered slightly when she said this. “It would be - unprofessional of me to continue working with you, pretending I didn’t know.”

There was a prolonged silence in the bathroom. Martina got up out of the tub quite abruptly. Her body was slick. I took a white towel off the radiator and handed it to her. “Thank you,” she mumbled. I left the room silently, just as she started to dry off.

The kitchen was empty on my way out. I was thirsty, so I stopped and poured myself a glass of water. It was cold and delicious, and I drank it so quickly that my throat hurt. I opened one of the cupboards and found a mug with a cat on it, one that looked cheap, and I hurled it against the floor, hard, so that it smashed into pieces.

13

Fostering Community Through Poetry In Dublin and Beyond

A conversation with The Madrigal Press

For many aspiring poets, the prospect of ‘getting published’ may seem more like an insurmountable obstacle than an achievable goal. All too common are the stories of rejection, and there are few poets who have not heard or read the words, ‘thank you for your submission, but we are unable to publish your work at this time.’ Rejection is commonplace, but rarely is it doled out through a constructive lens. This, in part, is what makes The Madrigal Press so special (pull quote).

The Madrigal was founded in 2021 by two students during a period of relative isolation. Helen Jenks, one of the founders and current editor, discussed the motivations behind creating a new publication. Many publications– both within and outside of Trinity– are either too niche or too daunting for entry level writers; there was a distinct lack of a ‘safe space’ for writers and poets to work on their craft.

I spoke to Helen and current deputy-editor (and longtime contributor) Luke Hayden over Zoom. “We wanted to give people a space for creation, and for them to come back to,” Helen says. “We look for work that is sincere, familiar, emotive, and well-crafted; we want to extend that same compassion and sincerity to the people we work with.”

Founded in the depths of Covid-Lockdown isolation, The Madrigal Press has fostered over the last three years a community which spans not just across Dublin, but across the entire world. Their first issue, ‘roots,’ received over 150 submissions– and astoundingly, each received a personalised acceptance or rejection letter in return. “It wasn’t sustainable,” Helen says, “but we still try to double down on forming personal relationships with our writers. We want to make it clear that their work was read, discussed, and valued in one way or another.”

“The nature of any magazine is that you’ll send out more rejections than acceptances,” Luke explains, “but it’s the way they’re sent, the content of the rejection, that really matters. We never want someone to think, ‘I should never write anything again.’ We try to encourage people to keep submitting.”

one would fare reasonably well in competition against even the densest of phone books. That being said, one will undoubtedly see some names repeated often, and for good reason; The Madrigal prides itself on the community it’s built since its origins in the days of lockdown.

Due to the lack of in-person college (or in-person life in general) in 2021, early contributors for The Madrigal had to be sourced remotely–meaning that poets from outside of Dublin, and outside of Ireland, could contribute. Nonetheless, one of the main goals stated by the editors is a constant striving to maintain an intimate sense of community.

“Helen has an encyclopaedic memory for contributors,” Luke says. “Since I joined The Madrigal we’ve received submissions from hundreds of different poets, and Helen knows almost all of them.” What makes this all the more remarkable is that many contributors for The Madrigal have never even set foot in Dublin. The publication has received submissions from every continent on the planet (except Antarctica, the editors note), with a particularly high volume of entries from all across ‘the English speaking world,’ as well as countries like India, Brazil, Nigeria, and Japan. As far as Dublin-based publications go, The Madrigal is unique in the incredible diversity of its authorship. To accommodate the global dispersion of their writer-base, The Madrigal has taken inspiration from their lockdown origins.

Looking through the contents of multiple volumes, one is struck by the sheer number of different contributors– a list of names as long as this

“Our big event is our launch, which we do on Zoom for every volume,” Helen explains. It’s important to us that we connect all these different people, both as writers and through the magazine itself.” Though Zoom calls may seem like mostly-forgotten remnants of the Covid-19 lifestyle, they suit The Madrigal and their writers very well in the years postlockdown.

“Hosting the launch on Zoom means that everyone can participate to the same extent,” Luke says. “No one is left out, no matter how far away they are.” Similarly, the magazine can be purchased in print, but is always available online for free (at themadrigalpress.com). For The Madrigal, openness and accessibility for writers is almost as important as the poetry itself.

In terms of content, The Madrigal deliberately avoids putting in place many guidelines. They seek out poetry which is “emotive, delicate, and sincere,” with the theme attached to each issue (‘roots,’ ‘whimsy,’ or ‘metamorphosis,’ to name a few) giving direction and cohesiveness, while still allowing poets substantial room for interpretation and creativity.

“In general we choose the themes based on what feelings we got from the previous issue, and what we’d like to contrast those with in the next

LITERATURE

issue,” Helen says. This way, reading each successive volume is different, but linked by a common emotional undertone. The first volume, ‘roots,’ focuses on origins, featuring often deeply-emotional reflections on the past. By contrast, the theme for the second volume is ‘whimsy.’ “We chose ‘whimsy’ because we didn’t want to get stuck in a place where we were only publishing really specific, serious, heavy poetry,” Helen says. “We try to make each volume tonally unique,” Luke adds. “It lets people come up with some very unique interpretations.”

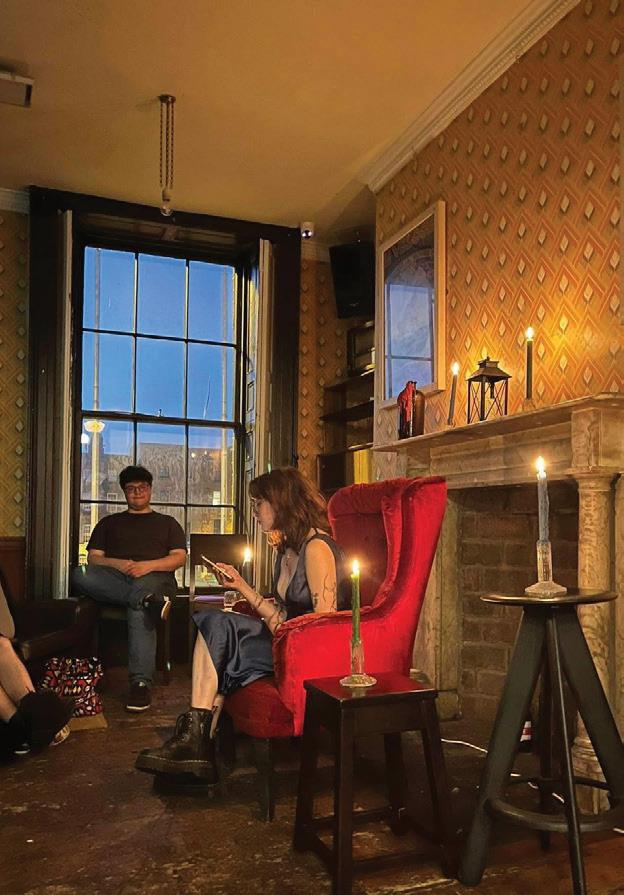

In addition to the magazine, which is published regularly 2-3 times a year, The Madrigal also collaborates with another publication, The Martello. Together they have produced two anthologies, as well as a series of poetry open mics, which began in the spring of 2023. “A lot of times, events that call themselves ‘open mics’ charge money for entry,” Luke says. “One of our goals was to have a truly ‘open’ mic, where anyone can come and read their work.”

There are few institutions that can successfully unite poets of all styles, from across the planet, ranging in age from 13 to 99. The Madrigal has achieved all of this. For poets in Dublin, as well as those operating through the digital frontiers of the internet, The Madrigal provides something truly unique.

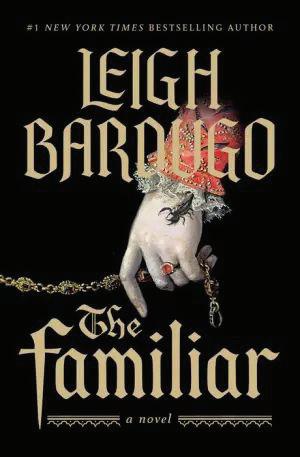

The Madrigal Press is due to release their latest volume, ‘reminiscence,’ this May. It will be available both online, as well as in print– you can order online, or visit Books Upstairs, The Winding Stair, Charley Byrne’s Bookshop in Galway , and (hopefully, Luke and Helen say) Hodges & Figgis.

15

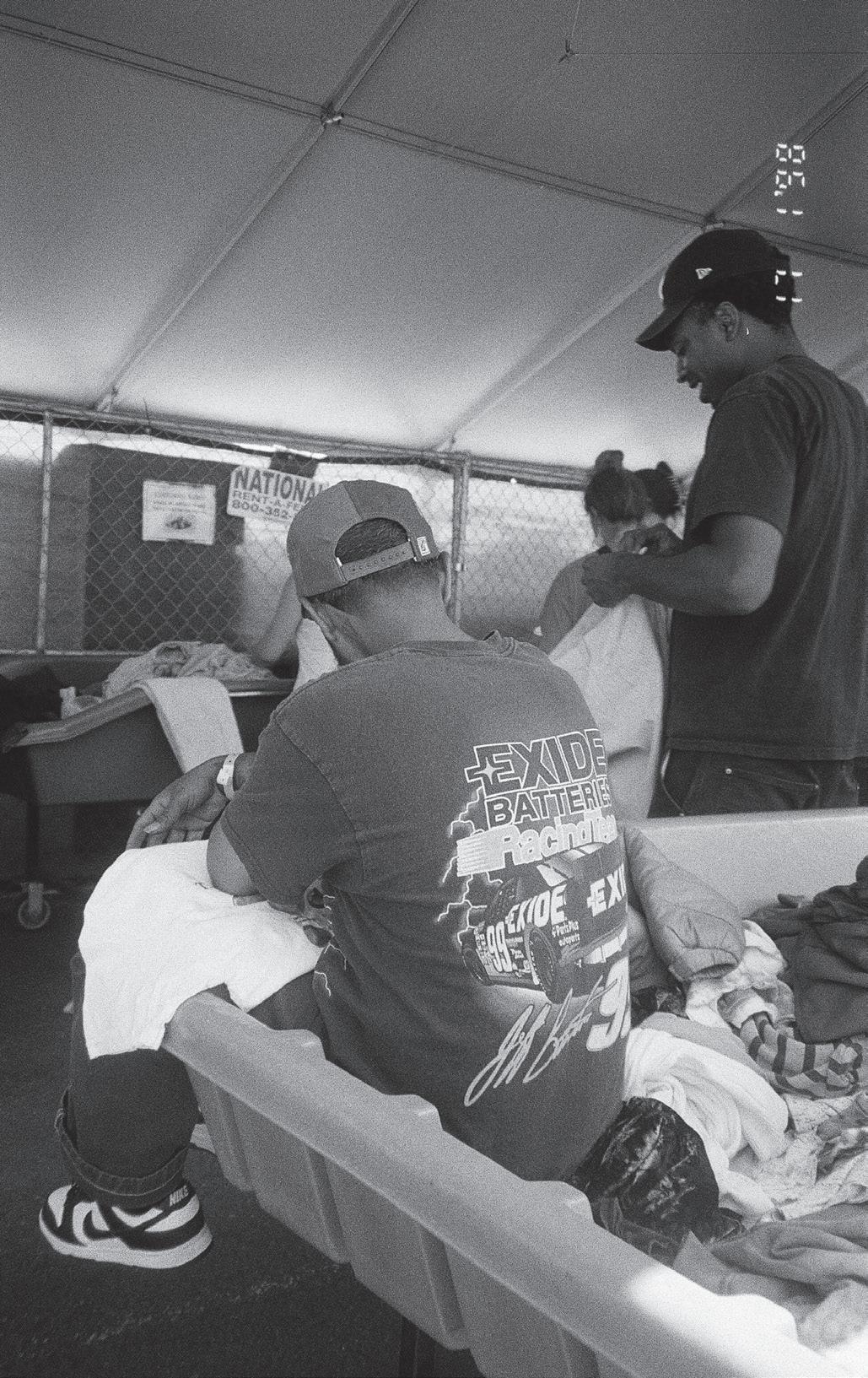

WORDS by Buster Whaley

Interview with The Frustrated Writers’ Group

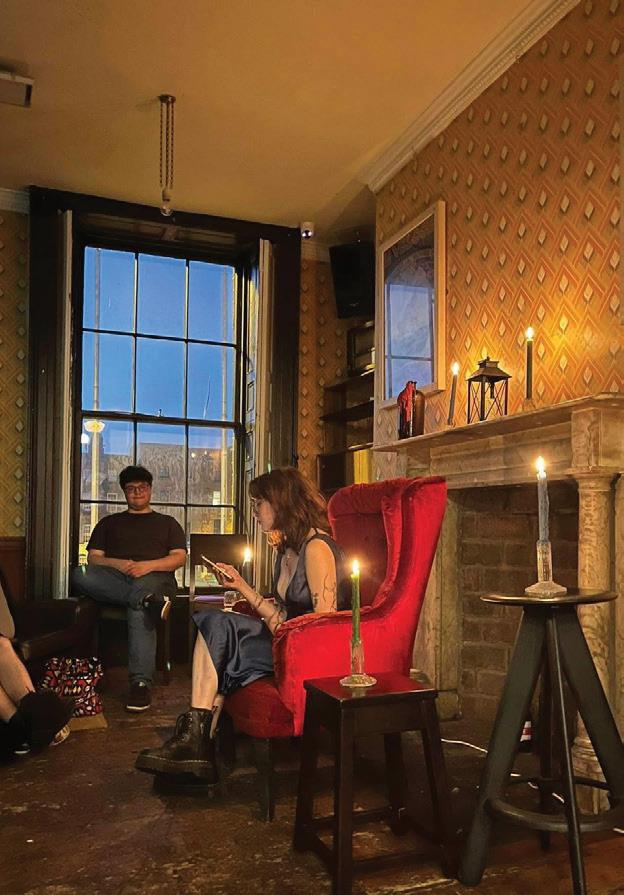

The first thing I did when I finished my dissertation was have a pint with a group who love writing. I sat down with the editorial committee of The Frustrated Writers’ Group, a Dublin based writer’s group that meets twice-monthly, in Lincoln’s Inn. The group has two hundred members and has published an anthology of writing, Frustrated Writers’ Group, Vol.1. Tom Roseningrave is the founding editor of the group, and upon publishing their anthology, set up the rest of the editorial committee. Clíodhna Bhreatnach is the Poetry Editor, Jess Kelly and Katy Finnegan are Prose Editors and Emily Featherman is the Drama & Performance Editor. After general chit chat about Trinity and debating whether to admit that I had got myself stuck in a bathroom stall ten minutes before their arrival, I asked the extremely well-dressed gang about their group and their experience of writing in Dublin:

Rachel: Tell me about your founding story. Tom: Really, it started with two things. One was that I was writing more seriously at the time, this was in 2021/22. If you’re not in a course or surrounded by peers who are reading your work regularly it can be a bit kind of confusing and you can kind of feel lost. At the time I was a member of an experimental music group called Kirkos Ensemble and the artistic director Sebastian Adams had set up this new free space in Stoneybatter called Unit 44, . I was involved with that and had access to it. It was as simple as that. Then I put out a post on Twitter asking if there would be interest in a writing group and it got quite a good response, I think like seventy or eighty people liked it, and that began a mailing list which is how I contacted people. I did a little bit of research into how to run a writing group and I suppose I didn’t really want to put too many restrictions on it. The ethos of Unit 44 and Kirkos Ensemble and being in this kind of DIY scene is that things should be inclusive, free if possible, open to everyone and, you should work towards facilitating that.

maybe just the styles of pieces that were presented in the early days and have led to this community- it’s fair to say all the writers are quite frustrated politically with the state of things in Dublin. We all definitely are aligned with our frustrations with Dublin so it kind of goes.

Rachel: For someone attending your writers’ group for the first time, what can they expect?

Katy: So each presenting writer will have an opportunity to read either the full piece if it’s short, or an excerpt of their piece if it’s a bit longer. They read that out, everyone claps, people go around basically and give

Rachel: I’m really intrigued by your name- The Frustrated Writers’ Groupwhere did that come from?

Tom: I just picked that name because I was finding this very solitary and like, you’re constantly getting rejections. Very few people aren’t getting rejections, so it is almost inherently frustrating. Then of course that leads you to the nature of the space, Unit 44 is Arts Council funded so it’s a free space, it’s also a DIY space and arts spaces in Dublin, especially free ones where they are quite hands off, aren’t very plentiful. So I guess from the very beginning there was a social imperative to coming together and making this a cooperative project- things are really difficult, rent is really expensive, it can be lonely, so we’re stronger together. It’s as simple as that. Jess: I think with the group being part of the DIY scene in Dublin and

constructive feedback and that’s moderated by me just to make sure people aren’t talking over each other and everyone stays constructive, but that’s never really been an issue to be honest. Everyone’s very supportive and enthusiastic and it’s kind of amazing really- the quality of some of the critique that comes from it depending on what it is. I think it’s very important to us that people feel comfortable to an extent and it seems like a nice experience for everyone- the two hours seem to fly by for me anyway.

Clíodhna: And we go to the pub afterwards!

Emily: We do online sessions as well and we run it basically the same because it works really well. Like Katy said it’s pretty amazing every time to see the level of critique given in the online and in person sessionswhen I started there weren’t as many people coming to the group but now as its grown you know we just have so many talented, engaged writersthere’s like 25-30 people who come to the in-person group. It’s honestly one of the most unique experiences I’ve ever witnessed of writing being workshopped where everyone has something really exciting to contribute. It’s such an amazing community and that really reflects online as well.

Rachel: What led you to publish your first anthology?

LITERATURE

Tom: We have this Google drive folder where all the work that had been shared by the group is archived there. I was just looking at the archive and I was like okay, woah, something really good is happening here so that’s kind of where the idea to publish an anthology came from. So I was like okay, a lot of us are writing, in my opinion really good work, [ that’s] not getting published as regularly as I felt like that work deserved to beit’s just the competitive nature of writing in Dublin or writing in Ireland. I would also say if you’re a musician you’re performing pretty regularly so you’re getting more people engaged with your work whereas if you’re a writer that doesn’t happen too often. So I started putting together this publication and that was kind of where I asked the rest of the editorial committee if they wanted to help with the editing so that was when it [the writers’ group] became a bit more collaborative and there was a bit more structure.

Clíodhna: It was cool for me because when I was six my Dad was in a writing group in Waterford and they published a pamphlet after a few months so that was like the first time I ever met someone who had published any writing, so for me it was really full circle. It made me feel more like a writer than sometimes getting something published in a really prestigious magazine because you’re with a group of other people, and being a writer in a social way is really cool because it’s such a solitary thing to do.

Rachel: You’ve recently held your first Artist Talk with Michael Magee. What was that experience like?

Tom: We were very lucky to get Michael Magee, he knew about the group for a while so was very supportive of what we were doing and our ethos. I think with the group as well I always think about facilitation, like how these different approaches or small changes, like having it in a venue like Mono’s bar, makes for a totally different atmosphere and conversation. I think one thing as well to point out about the group is I think a lot of us are in the same position where we might be termed as ‘early career’ artists. I don’t know many other projects that are self-organising for early career emerging writers, us on the committee are in the same position as the members. That’s why we would have an event like Mick speaking rather than doing the same old thing, you know, go to the Irish Writing Centre or Hodges Figgis, because for many of us, maybe that’s not a great night out. We wanted to mix it up so Mick was in conversation but three of our members read, and we also invited a Palestinian poet, writer, and academic Bana Abu Zuluf to read.

Rachel: Jess, you were one of the readers at the event. How did that go?

Jess: It felt really inviting and casual, not intimidating like some literary events when you walk into the room and there’s a big chandelier and men painted on the walls from 200 years ago- it was a completely different vibe. I felt very at ease and happy to be a part of it. I think it’s a great way of helping to platform new writers and give people the opportunity to read and to show their work. The writers from the group are chosen based on how their work links up to the artists so being a part of that I felt really privileged to get a chance to read in front of Michael because I admire his work and I could feel a connection between my work and his, and his background. I felt I wasn’t just reading at an event but getting to read to this writer I admire.

Rachel: Lastly, what’s your favourite thing about being a writer in Dublin?

Katy: I think it is the fact that people take it seriously here. If you tell people you’re a writer maybe in some places they’ll literally just roll their eyes and be like gowan, gowan, but, maybe it’s just the circles I’m moving in but if you tell someone that you’re writing or involved in a writers’ group, I feel like universally the response has been like, oh my

god, that’s so cool! People really take the time to read each other’s work, support each other, share opportunities and I think for me that’s what this community is about- its people who take it seriously and aren’t just kind of like you know, oh that’s a nice hobby. It’s willing to engage on a deeper level because I think nobody writes as kind of a hobby they enjoy. It’s torturous!

Clíodhna: I think what’s nice about being a writer in Dublin is that it’s not like there’s literary cliques where only writers hang out with each other. You can really get inspired by people who take other things seriously like being a historian, or working in a trade union but kind of everyone has a cultural part to play in it no matter what they do in Dublin.

Emily: I have an unusual perspective from this because I’m obviously not from Dublin but I came to Dublin to do a masters and I just showed up to this group. It’s really been out of all my experiences in New York and anywhere else the best artistic community I’ve ever sort of witnessed, so it’s definitely this group for me.

Jess: The main things I’m writing now involve reflections on class in Dublin and I love being part of a community where people are casually talking about the things I want to write about. I feel like the frustrations I have in my personal life they’re shared with others and I feel like I’m kinda doing something about it just by producing some writing and having the opportunity to share that and having other people connect to it.

Tom: It kind of just changes your brain chemistry when you’re walking around and observing things and just hearing different snippets of conversation- it just kind of magnifies the things you care about. I think Dublin is an amazing place for just hearing the crazy stuff- my Notes app is just full of the mad stuff you hear on a regular basis. I’ve got this story coming out next in the Banshee magazine and that’s all these fragments of different people in Dublin over the course of a minute but that was really easy to write because I had loads of things in my Notes app that I had kind of just overheard. If you’re doing the practice of writing, well then your kind of brain chemistry has changed like that and you’re open and aware of all these things and I think Dublin is germane and a good place to be for that.

The Frustrated Writers’ Group can be found on Instagram @frustrated_____ writers and always welcome new members. Limited remaining copies of Frustrated Writers’ Group, Vol.1 can be found in Marrowbone Books and Bang Bang Cafe. The group will collaboratively edit the next group anthology Frustrated Writers’ Group, Vol.2, later this year; its due for publication in Autumn 2024.

Tom has stories in the current Banshee (Issue #17), & the forthcoming issues of The Stinging Fly (Summer 2024) & Profiles (Issue #3; late 2024). All three of these stories were workshopped at the group.

Katy Finnegan’s story ‘Bl0ss0m’ is in the current Banshee (Issue #17) & she has another story, ‘Undamaged’, in the next edition of The Honest Ulsterman. Both stories were workshopped at the group.

Clíodhna Bhreatnach has work forthcoming in the next Banshee (Issue #18; Autumn 2024). Her poems have recently been published in The Stinging Fly and Skylight47, and she was highly commended for the Forward Prize in 2022. She is also nearing completion of a poetry pamphlet about work and leisure.

Jess Kelly is working on a collection of dialogues about class consciousness and queer identity in Dublin.

WORDS by Rachel Kelly

17

Should I start saying more, or saying less?

LITERATURE

Often, people feel they say too little for themselves in interactions, whether it be arguments or superficial chat. I say often, although I am just assuming this to be true.

Saying more is the obvious solution to feeling that too little has been said by oneself; to say even less would be to trust the other person to read one’s mind accurately, and savour each word appropriately. I wouldn’t be able to trust saying less than I do now, despite having adequate friends. I say that, but I’m sure I would trust them, and they’re more than adequate quite often. Saying more requires trusting that the other person will patiently listen, which is more acceptable than trusting the other person will understand you without a clarity of words.

Saying less doesn’t limit you to those chosen words, though. Like the first sentence of this piece, the limitations and flaws of a statement grow, and the words decay extremely quickly. Words give you oars to paddle around with, and more speaking would communicate more words, certainly- but words are only words and it’s too easy to forget that we don’t mean words, we use them. As I write, speak, or type, I use words to best convey what I mean and even this sentence about it is too plain to say what that means.

Hidden in each spat of conversation, in each little word, is the person using them. This is another assumption, but it can’t just be words that these words contain- that would be distressing.

To say more, then, is to throw more personal clues at whoever will listen. But what about arguments that reach a crescendo, such as the circumstantial victor’s monologue? What happens to the so-called loser of this battle as they’re forced to sit and lick their wounds and listen? In each monologue in every argument that has one, is there a point at which the listener’s face lights up, surrounded by the remains of the kitchen, and they say “Oh no wait, yes, you’re totally correct”? Absolutely not. Not always.

You knew that; I’m not telling you- I’m reminding you for the sake of me wanting to say something else overall, which also explains my unfounded opening claim. Arguments do not consist entirely of education eitherthey consist of legal battles between two equally jammy lawyers.

The more words you send my way, the more you lock yourself into an opinion that, in the heat of your rambles, becomes very specific and increasingly unfounded. The more words I fire back, the further away from escape I go, until we are both tapping around each other on lily pads. When one person’s monologue trips them up, or, worse, they run out of words full-stop, that’s them in the pond all wet. And then the winner hits their mark and begins the victory lap monologue. Let us not also forget how often we look back on what we ourselves have said in different contexts such as arguments, and how disconnected from ourselves those words seemed. Do I even know what I’m rambling about?

So where does a water canon’s worth of words get you? Not out of the ruins unscathed, probably. But, on the other extreme, witty comebacks and oneliners are more pleasurable than decisive, and rarely hold the satisfaction of a good closing speech or solid debate strategy; is the middleground to then be a Goldilocks-portion of words? I think, in the case of arguments, the Goldilocks approach might be the best to follow unless and until it fails or comes across poorly. Then release the kraken and sure we won’t be friends tomorrow, take it how you like. This is just us back in the pond

problem, wet, though.

What good can come of no words? Of silence? The extreme extreme. There’s misinterpretation to worry about- the untrustable nature of other people locking that one in. But what about an understanding silence, where you’ve said nothing but they know or can reasonably guess where your head is at based on this lack of words. Or, and this is the ideal, an un-poked silence. No understanding you in your silence and drawing conclusions or reasonable thoughts on it- all essential parts of interpreting someone and their use of words to convey what they mean, so fair enough to do it to silence too.

With un-poked silence, you’re not put into such a box of the other person’s “understanding”. Fuck off, actually. It’s not fruitful, possible, or necessary to seek that kind of view of another. It’s only to gain information for one’s own plans anyway- arguments have proven this strength we have in repurposing people’s words and reusing them to knock them over. So don’t try to understand me in your image. Don’t consider my wordlessness and meet it with a worded understanding. That would be akin to a theological understanding of a cookbook.

The clear thing to me is that words are things that look like our own arms, but are more like oars, and oars which turn out to be incapable of following direction beyond vague approximation. People sometimes say the wrong thing and we know what they mean, which is an exception that proves that rule. I’m not assuming here, I’m directly referring to my friend saying “consistence” instead of consciousness. We knew what they meant, and life goes on. If I can’t paddle straight, then words are overrated at the very least. We’re too stupidly intelligent to do without stupid words, though. But I think no words would be good for a while, or at the very least no words after twenty minutes on the same topic.

It took hundreds of words to express this inane piece, and they’re already mostly rotten. Even in their decay, and maybe only through words’ decay, you’ll remember the point as you want to remember it, just like I will. We both won the non-argument, I’ve already done my monologue, and we don’t have to talk to each other. Class.

WORDS by Cormac Nugent

PHOTOGRAPHY by Giulia Vettore

21

WHATS GOING ON?

Let It Be a Tale Abbey Theatre Tickets €20

Five Lamps Art Festival Free Admission APRIL

28

11-20 The

15

Bohs vs Palestine Charity Football Match

Dalymount Park

Tickets on Ticketmaster €40, €20 concession

Bloom Flower Festival Phoenix Park Student Tickets at Ticketmaster from €22.20

2-6

Sin e Pub Weekly Comedy Club Free Admission

EUNIC European Film Club Series Until May 30 Free Admission

ON GOING

Silent City National Gallery of Ireland Until July 21 Free Admission

MAY

JUNE

23

Goodbye Trinity

What Coming-of-Age Cinema taught me about Growing Up

As my final year of college wears on, the impending fear of the unknown draws closer into view. It’s a feeling that is familiar now, cropping up with any life transition: from primary school to secondary, from secondary school to college and now from college to the working world. As someone who has been in college for six years, I am well versed with seeing friends leaving the comfortable bubble of Trinity and encountering the difficulties in adjusting to a world where making friends becomes harder, your social circle shrinks ever smaller and aspirations shift from lofty idealistic dreams to fit in with the reality of life. Whilst there is a degree of excitement in finally leaving college I find myself seeking out and rewatching coming-of-age films, vicariously living through the depictions of growing up and reliving my college experiences. As a queer Asian person who lived in rural Ireland my coming-of-age moments didn’t transpire until college began, so seeing this phase of my life finally drawing to a close feels bittersweet and poignant, but ultimately it is necessary. It’s a sentiment that many people leave college with, so this essay goes out to all the overthinkers, those who didn’t find themselves until college and those who feel too much.

go on the trip in order to escape her domestic life upon learning that her husband is cheating. Throughout the trip, the boys and Luisa learn about each other and open up to one another as they navigate driving towards the beach in their ramshackle car. The boys both end up hooking up with Luisa but by this point the lessons of the road trip have transcended their simple urges to have sex. They embody the freedom which Luisa is pursuing, unbeknownst to them in her final days of living. It’s the ending of the film which acts as an emotional gut punch, when we learn Tenoch and Julio no longer speak to each other following that road trip and Luisa has passed away from a cancer only she was aware of. It brings into sharp focus how restrictive it can feel living in a capitalistic and rigid society, a society where many behaviours are silently discouraged. Y tu mamá también acts as an ode to living life on your own terms sooner rather than later. This is an essential belief to carry when moving from college to working life. However, the film also understands that doing so is easier said than done.

I like to think of myself as a connoisseur of coming-ofage cinema. I have largely exhausted the “Best Comingof-Age Movies to Watch” lists, so it was a pleasant surprise this year when I realised I had missed the highly acclaimed Y tu mamá también (2002). A film which is all too relevant to my current life transition of moving from college to the working world. Whilst college has been a whirlwind of trying to find yourself, it can feel like it comes screeching to a halt when you begin to venture into working a full-time 9-5 job. Workplaces and as an extension society can feel restrictive; there’s a certain way to dress, a certain way to speak, a certain way to generally behave which can squash the self-expression which you have mustered together throughout college years. Tenoch (Diego Luna), Julio (Gael García Bernal) and Luisa (María Verdú) on the face of it are the three main characters in this fun but unoriginal coming-of-age road-trip film. There’s a freedom of expression which permeates the film, especially in regards to sexuality and personal freedom. The road trip to the beach initially begins as an exercise for the two boys to try and seduce Luisa. Meanwhile Luisa appears to agree to

Reflecting further back to when I was coming to the end of secondary school, Lady Bird (2017) was released in cinemas and a generation of teens, including myself, fell in love with the movie. The titular character (played by Saoirse Ronan) lives in Sacramento, California and throughout the film Gerwig masterfully illustrates the growing pains of living in a place where you don’t feel like you belong. Lady Bird is so much more than that though, and as a semi-biographical film it touches not just on our environment but also on interpersonal relationships. This ranges from Lady Bird’s first kiss to friendships to her familial relationships, especially the fraught relationship with her mother (Laurie Metcalf). As she navigates the end of high school and the transition to college it results in an expected tension with Sacramento itself as well as with her family

FILM

and friends. I personally have a mixed race background and I think as any third generation kid can attest to, it comes with unique challenges, including friction with parents who grew up very differently. Although even more importantly as a mixed race kid living in my small and very white Irish town of 2,000 people, Abbeyfeale, it translated into a feeling of exclusion from the close-knit community. Much like Lady Bird and a vast number of teens today, my feelings of disenfranchisement towards where I lived and friction in relationships was exacerbated coming to the end of secondary school. I was academically strong in school and similar to Lady Bird’s aspirations to attend a big liberal arts college like Yale, I had aspirations to go to a prestigious college (which, funnily looking back now, was Trinity College Dublin). However as I finish up college and grow further and further away from who I was in Abbeyfeale, I find that the Joan Didion quote which opens the movie has only resonated with me more: “Anybody who talks about California hedonism has never spent a Christmas in Sacramento.” There is a level of self-pleasure which is associated with living in cities like Dublin; I have access to and the chance to engage wider in things that I care about such as film and even writing this essay. Whilst growing up in Abbeyfeale did have plenty of challenges for a marginalised, sensitive and quiet kid like myself, it also has provided me with grounding and an extra appreciation towards possessing the ability to invest time into things that are deemed self-indulgent - like writing and film.

Where better to end than the film that largely began my love for movies, The Perks of Being a Wallflower (2012). In my childhood I watched it with eyes wide and when it ended I remember sobbing into my pillow. It stirred something in me, that life could be different, so I hedged all my bets on moving to Dublin. Admittedly the film is polarising in certain groups. It is rooted in a world of privilege, the quintessential white American suburb, but I don’t think asking every film to address our socioeconomic issues is the answer to addressing social inequality. If a film touches the lives of a few, shouldn’t that be enough? Much like Charlie (Logan Lerman), the main character in the film, I was a shy teen and arrived at Trinity Halls ready to be taken under the wing of a quirky group of teens à la Sam (Emma Watson) and Patrick (Ezra Miller). Now what actually transpired was a swift mental breakdown and a repeat of my first year as I aimlessly attended college lectures completely lost in a new city way that was far bigger than Abbeyfeale. Unfortunately it is true - real life isn’t like the movies.

Hitting the redo button, I decided to throw myself into every random college society I could find until one eventually did stick. Low and behold I did find a group of friends, most of whom I still am close with now. If there was anything to learn from my experience, it is that sullenly walking around campus isn’t going to result in finding the connections you desire. I had missed what made Charlie find his own group in the film. It wasn’t simply waiting for friends to fall on his lap, he braves dancing with Sam and Patrick at the school homecoming party to introduce himself. Furthermore, forming connections with people requires vulnerability; it is when Charlie tells Sam about his close friend who passed away (admittedly he does so while drunk but I can’t lie and say that many open conversations I had didn’t happen in smoking areas of pubs or the dancefloor of the George) that his friendships really begin to blossom. We’re all a lot more astute than we give each other credit for. It’s clear when someone really values your presence and a sign of this is simply allowing yourself to be vulnerable. The Perks of Being a Wallflower is a film I have returned to again and again, and each time it brings up a past memory, sometimes painful (like that incredibly poignant final act of the film), but it really brings into sharp focus how much I have grown since I first watched it.