From the Editors

Genie Nicole Giaimo and Sam Turner

Why do Writing Center Professionals Publish? Examining and Improving Our Practices

Candis Bond, Elisabeth H. Buck, Elizabeth Culatta

The Cost Of Representation: How The Publication Process Impacts Black Researchers In Writing Studies

Ronada Dominique

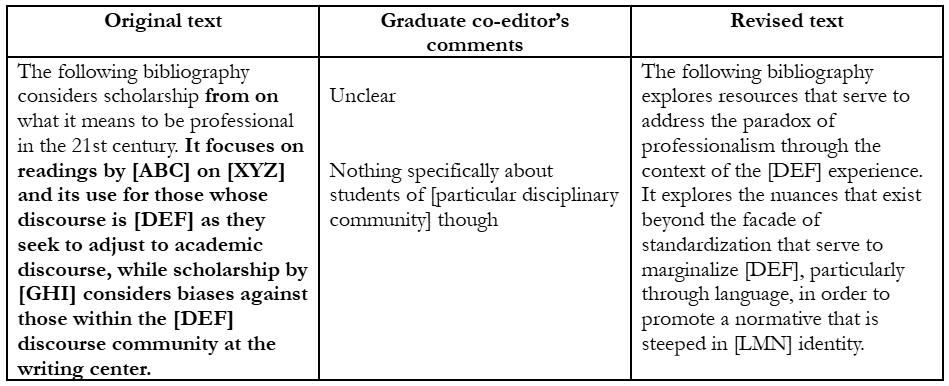

Mentoring in Editorial Spaces: Graduate Co-Editors as Literacy Brokers

Rabail Qayyum

Sis, Put That Playlist On and Sip Through the Emotions of Writing

Shewonda Leger

From Personal Rejection to Shared Satisfaction: Thriving through Principles of Relationship-Rich Collaboration

Stephanie Roach, James Schirmer, Bob Barnett, and Jacob Blumner

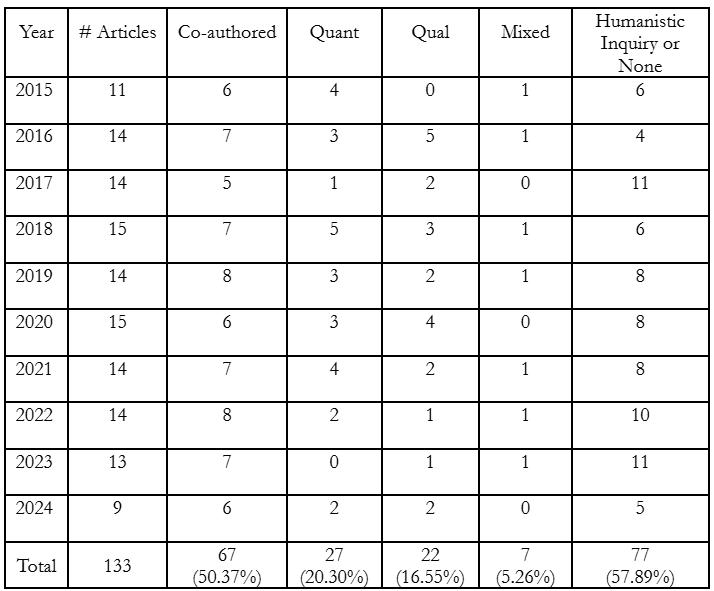

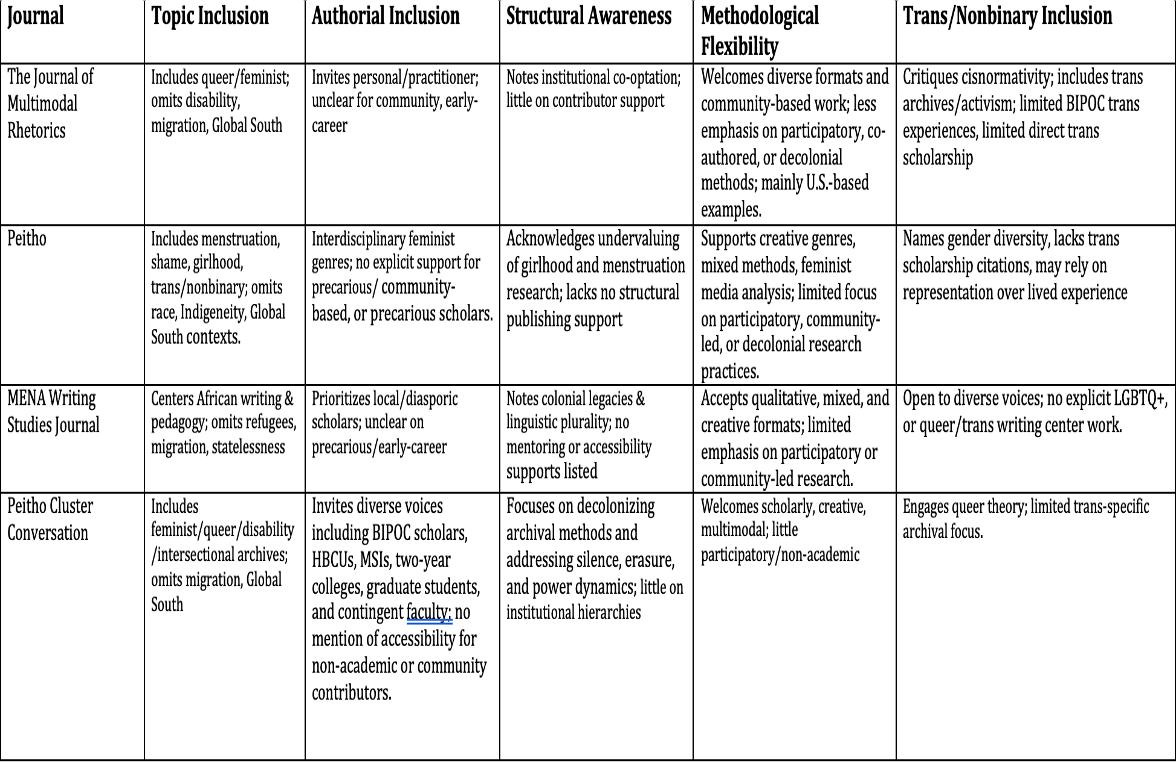

Assessing the Field: Establishing the Ethos of Writing Center Publications

Joseph Cheatle

The Research Tax: The Hidden Costs of Publishing Underrepresented Knowledge

Sarah Rewega and Waed Hasan

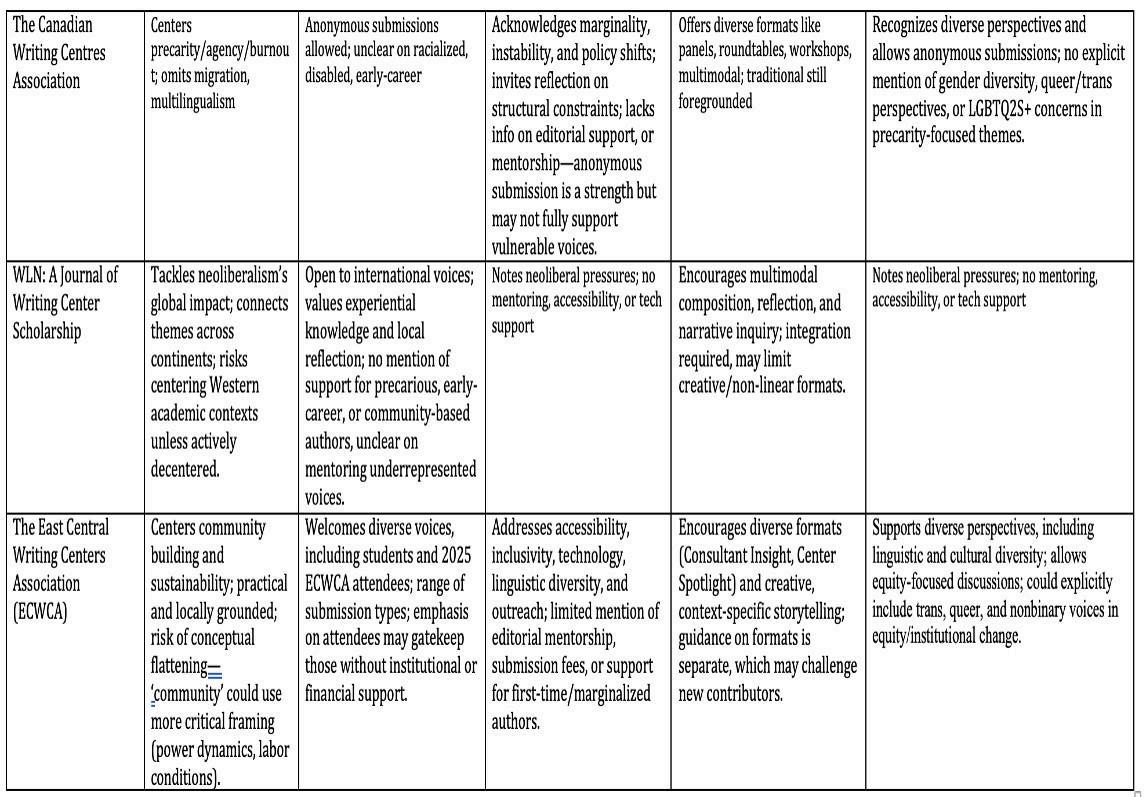

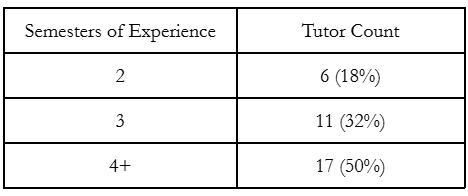

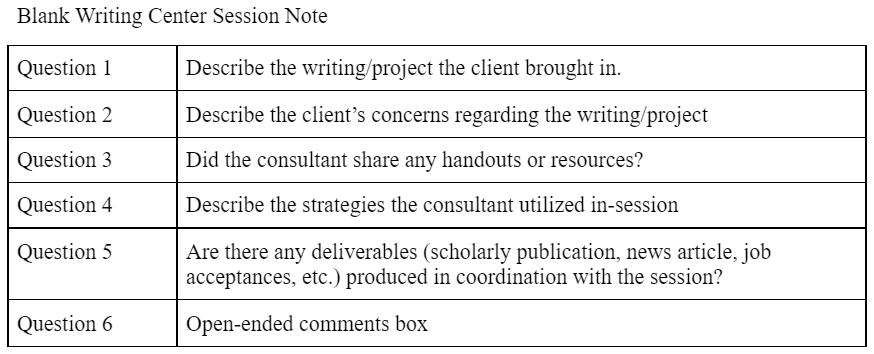

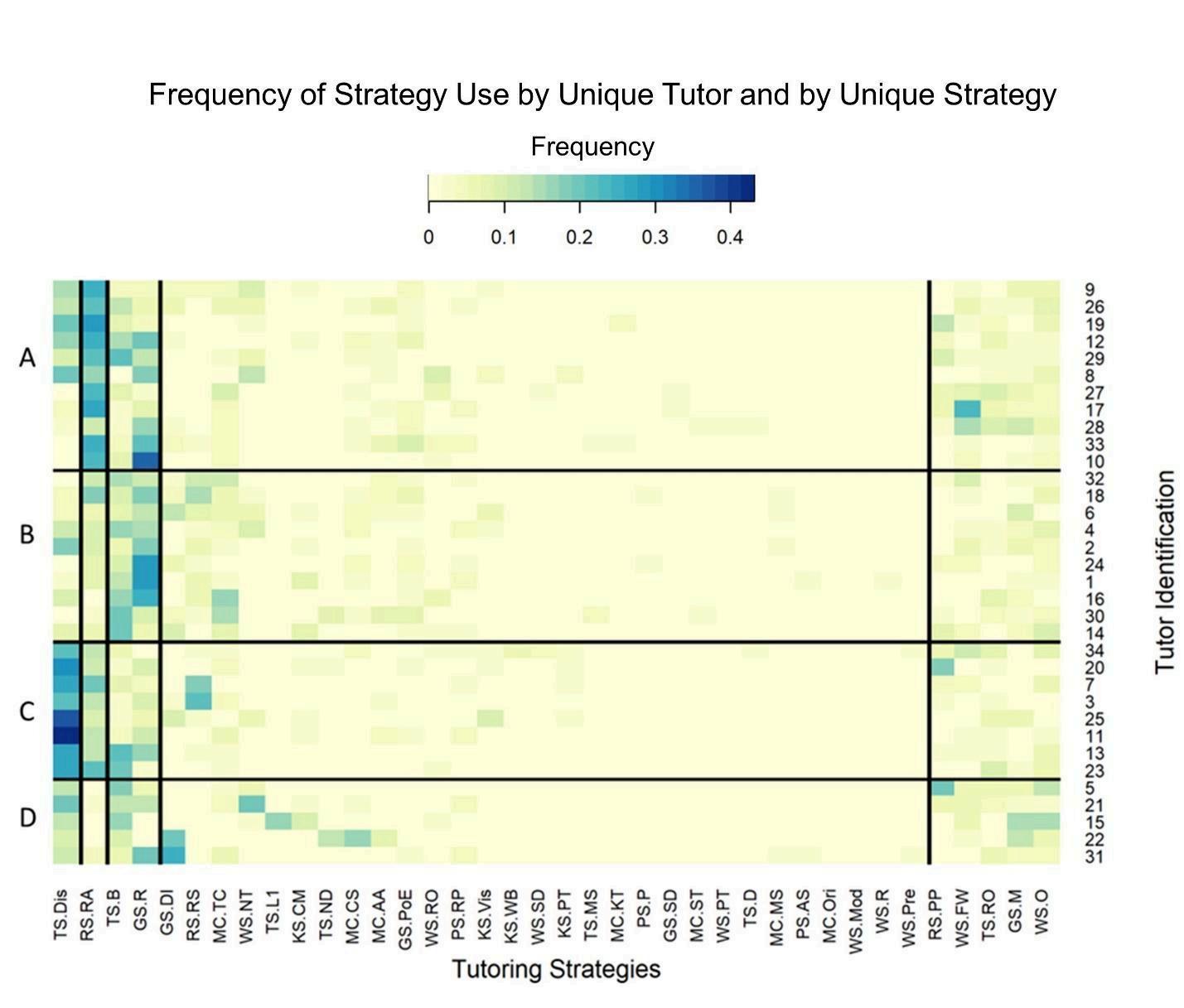

Quantity Over Quality? Defining Educator Flexibility Through Tutor Strategy Use and Session Engagement

Genie Nicole Giaimo and Sam Turner

Rejected: Co-authoring With Undergraduate Students

Erin B Jensen

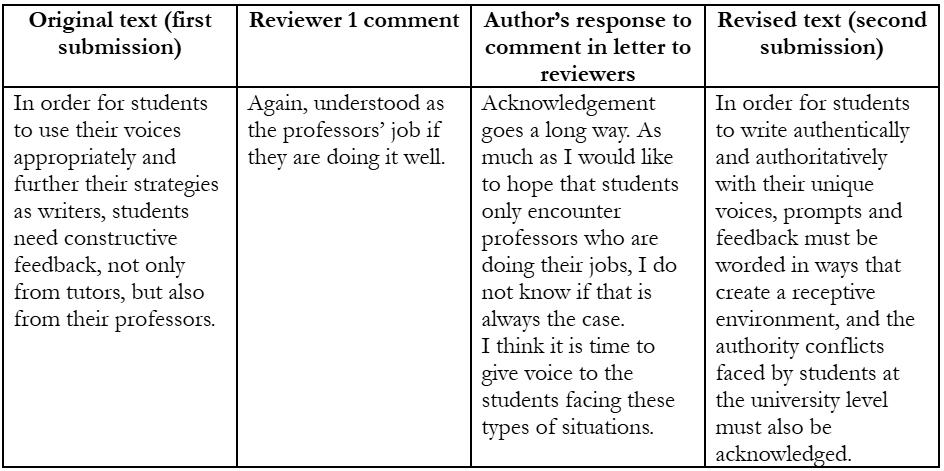

Exhausted: The Toll of Hyper-revision on a Writing Center Administrator

Andrea Efthymiou

Candis Bond, PhD, is an associate professor of English and interim chair of the Department of English and World Languages at Augusta University, where she served as director of the writing center for nearly a decade. Her writing center scholarship has appeared in WLN, Writing Center Journal, The Peer Review, and Praxis: A Writing Center Journal. She currently serves as the president of the Southeastern Writing Center Association (2024-2026) and is a co-editor of WLN: A Journal of Writing Center Scholarship

Elisabeth H. Buck is an associate professor of English and the Director of the Writing Center at Fordham University in New York City She is the author of Open-Access, Multimodality, and Writing Center Studies (Palgrave, 2018), which was a finalist for the 2018 IWCA Outstanding Book Award, and the co-editor of the forthcoming collection Writing Centers and AI: Generating Early Conversations (WAC Clearinghouse Perspectives on Writing Series, 2026) Dr Buck is the incoming professional editor of The Peer Review journal

Elizabeth Culatta, PhD, is an associate professor of sociology in the Department of Social Sciences at Augusta University Dr Culatta studies social determinants of health, especially focused on identity tied to mental health and substance abuse for young adults. She has published in journals including Society and Mental Health, Journal of Women and Gender in Higher Education, and Journal of Health Psychology

Dr. Ronada Dominique is a Black millennial scholar focused on advancing equity and inclusion in higher education Her research centers the experiences of Black students and challenges the systemic gaps in academic curricula and institutional practice. Through her teaching and scholarship, she advocates for classrooms that honor diverse perspectives and make space for every student’s story

Rabail Qayyum, PhD, teaches Intensive English Program students in the Language and Culture Center, University of Houston. She spent over a decade teaching academic writing, public speaking, and business communication to university students in Karachi, Pakistan Her research interests include second language writing, assessment, writing center studies, and adult literacy

Dr. Shewonda Leger is an Assistant Professor of Multilingual Writing and Pedagogy in the Department of English at Florida International University. Her research interests include Haitian narratives and histories, heritage linguistics, Caribbean women’s rhetorics, Black feminist film theory, and health disparities affecting Black women

Stephanie Roach is an Associate Professor of English who has been teaching writing at the University of Michigan-Flint since 2003. Stephanie is the former Director of Writing Programs and Associate Chair of English. She has co-authored scholarship on reflective pedagogies, integrative learning, and folio thinking with members of the UMFlint Persistence and Mattering in Undergraduate Education Research Cooperative Within the field, she has written on WPA metaphors, and, with the authors here, on spaces for composing.

James Schirmer is an Associate Professor of English who has been teaching writing at the University of Michigan-Flint since 2008. A former Chair of English, he currently heads the Department of Language & Communication He has written about social media and video games in relation to composition pedagogy and worked with his coauthors here on the histories, futures, and spaces of writing centers and computer writing classrooms.

Bob Barnett is a Professor of English who has been teaching writing at the University of Michigan-Flint since 1994 Bob is a former writing center director and former Dean of the School of Education and Human Services at UM-Flint He has written about writing center theory and practice, general education reform, and leadership development. He is currently working on a book on the history of American Counterculture.

Jacob Blumner is a Professor of English and Director of the Marian E. Wright Writing Center at the University of Michigan-Flint since 2005. He teaches writing courses that span the curriculum. He writes about

Praxis: A Writing Center Journal

Vol 23, No 2 (2026)

writing centers, writing across the curriculum, and secondary school to college connections. He has co-edited three books, and his work has appeared in The WAC Journal, Across the Disciplines, and Praxis: A Writing Center Journal. He enjoys writing haiku and is exploring haiga.

Dr. Joseph Cheatle is an Assistant Professor and Director of the Writing and Communication Center at Oxford College of Emory University. In addition to researching the broader narratives of writing center studies, he is interested in the organization and systems that help writing centers to be successful His work is previously published in Writing Center Journal, The Peer Review, The Journal of Writing Analytics, and Kairos: A Journal of Rhetoric, Technology, and Pedagogy.

Sarah Rewega is a PhD candidate in English with research interests in feminist theory, visual culture, and digital discourse She has over two years of experience working in post-secondary writing centres and is deeply committed to student-centred, process-based, and inclusive writing support She has also taught academic writing and literature at the university level. Her recent article, “Women’s March and the Borders of Belonging: Rethinking Collective Space Through Transnational Feminism,” was published in (Un)Disturbed: A Journal of Feminist Voices. She is also the author of the poetry chapbook becoming.

Waed Hasan is a Palestinian refugee and scholar She holds a PhD from the University of Guelph (2025) Her research lies at the intersection of Palestinian Studies, Critical Refugee Studies, and postcolonial theory. Drawing on intergenerational narratives of exile, Hasan’s work establishes Refugee Poetics as an inclusive, decolonial framework that centers lived experience, memory, and creative expression in theorizing refugee life Her scholarship bridges personal testimony and critical theory to foreground refugees as producers of knowledge, culture, and resistance Hasan has published and has forthcoming articles with Liverpool University Press, Praxis: A Writing Center Journal (University of Texas), University of Toronto Press Journals, and Routledge’s Literary Studies in Social Justice series.

Dr. Genie Nicole Giaimo is an Associate Professor of Writing Studies and Rhetoric and Writing Center Director at Hofstra University Their research utilizes quantitative models to answer a range of questions about behaviors and practices in and around writing centers and writing programs They are the co-editor of Writing Assessment at Small Liberal Arts Colleges with Megan O’Neill (2025), the co-author, with Dan Lawson, of Storying Writing Center Labor for Anti–Capitalist Futures (2024); the author of Unwell Writing Centers: Searching for Wellness in Neoliberal Educational Institutions and Beyond (2023) which won the IWCA Outstanding Book Award in 2024, and the editor of Wellness and Care in Writing Center Work (2021). They have also published in Praxis, Journal of Writing Assessment, Composition Studies, Writing Center Journal, TPR, Journal of Writing Research, Kairos, Journal of Writing Analytics, and Journal of Multimodal Rhetorics, among others. They are the outgoing professional editor of TPR: The Peer Review This is the second time they have served as guest editor for Praxis

Sam Turner is a PhD candidate in the Department of Rhetoric and Writing at the University of Texas at Austin Her dissertation project leverages feminist rhetorical theory and critical disability studies to explore how people narrativize their experiences of obsessive-compulsive disorder outside of diagnostic settings. Sam currently serves as a managing editor of Praxis: A Writing Center Journal and teaches rhetoric and composition courses at UT and for incarcerated adults in Austin

Erin B. Jensen is a tenure track Associate Professor at Midwestern State University, Texas Previously she taught at Belmont Abbey College where she co-authored several articles with undergraduate students including the one discussed in this issue. She focuses on encouraging students to be involved in undergraduate research projects and in publication opportunities

Andrea Efthymiou, PhD, is Writing Center Director and Associate Professor at Queens College (CUNY). She serves as treasurer for the National Conference on Peer Tutoring in Writing and co-editor for WLN: A Journal of Writing Center Scholarship. Andrea’s current projects include a collaboratively-edited collection on interfaith dialogue in writing centers and writing classrooms and a study of the rhetoric of child adoption in the US Her scholarship has appeared in various journals and edited collections

Genie Nicole Giaimo Hofstra University genie.n.giaimo@hofstra.edu

Publishing, a mainstay in academic disciplines, is not a neutral or uncomplicated practice. For many scholars, publishing can be a herculean task made more complex by reviewer feedback and hyper-revision Many articles have been written about the complexities and intersecting challenges in academic publishing, from plagiarism controversies (Awasthi, 2019), to how exploratory and creative research is inhibited by the metrics and standards of well ranked journals (Agafonow et al., 2024), and the citational inequities and bibliographic biases that drive impact factor scales Gender, racial, linguistic, and geographic bias, as many studies have shown, is rampant in academic publishing (Drieschová, 2020; Conklin & Sing, 2022; Lee et al., 2021; Thien, 2023). In writing center studies, Alexandria Lockett (2019) aptly identifies the taxes placed on Black graduate students, which includes a writing tax that impedes production and publishing In 2017, Elisabeth Buck found that writing center researchers yearned for more digital and open access publication platforms as these offer greater idea dissemination, including outside of the United States.

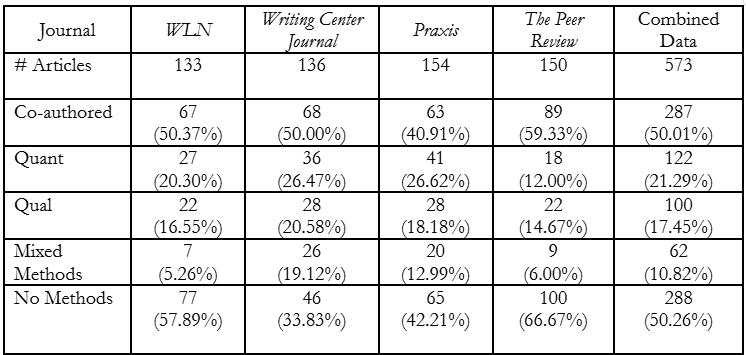

This special issue of Praxis explores the publishing, revision, feedback, and writing experiences of practitioners in writing center studies and the broader discipline of writing and rhetoric. Contributors like Shewonda Leger and Rabail Qayyum explore autoethnographic experiences with writing and publishing, while Bob Barnett, Jacob Blumner, James Schirmer, and Stephanie Roach outline an approach to writing and publishing as “relationship-rich” collaborative practice Joseph Cheatle, Ronada Dominique, Waed Hasan and Sarah Rewega, and Candis Bond, Elisabeth Buck, and Elizabeth Culatta share empirical research on the state of journal publishing in our field. Several contributors–including Andrea Efthymiou and the editors of this issue–write about experiencing hyper-revision and being repeatedly rejected by journals in the field

It is no secret that many of us have experienced significant barriers to publishing in writing center studies and the broader field of composition and rhetoric. Some of this might

Sam Turner University of Texas at Austin

praxisuwx@gmail.com

have to do with writing center research struggling to gain traction in composition journals, and it may also have to do with the preferences, feedback, and training of reviewers or even journal editors This special issue had two interrelated goals: to publish pieces that give in-depth insight into the challenges of the publication process in our field–especially for those of us who are working in contingent and non-tenure track positions–and giving a venue to submissions that have been previously peer reviewed but were rejected by other journals All submissions went through a mentorship-based peer reviewed process; we did not sacrifice quality in the process but led with humanity and the goal of bringing all submissions to press.

Publishing in our field frequently relies on free labor performed by editors, reviewers and authors. While tenure track and tenured colleagues benefit from the academic currency of the publication process, many do this work for free and outside of their job duties. The majority of writing center practitioners occupy contingent non-TT positions (Herb et al., 2023). So, while we appreciate the material conditions of publication work–and want to extend our gratitude to those who have joined editorial teams or review boards and worked for little-to-no compensation performing time-consuming and intricate work–we also want to recognize the profound amount of labor that bringing a single article to publication requires for authors. For those without institutional support or those, like Erin B. Jensen (“Rejected: Co-authoring With Undergraduate Students,” 2026), who work with undergraduate students to co-publish, this work is even more complex and time consuming We ought to make the publication process–particularly the review process–more transparent, ethical, and streamlined to honor the labor of all those involved in this work.

In other fields, as well as our own, publication practices are changing. Open-access publishing is becoming commonplace–over the last few years, for example, two of the major journals in writing center studies became open access, joining the other two journals Journals are publishing standards for inclusive review work

and, also, citational practices. Journal review-and-editorial boards are expanding to include underrepresented scholars. Editors and reviewers are being paid for their labor Reviewers are required to identify themselves rather than a double-blind process. Professional associations and journals are creating mentorship programs and models to help bring authors to publication. In writing center studies–and the broader field of Composition and Rhetoric, we have seen some of these changes while others–like an open-review process or paid review work–remain elusive

Agafonow, Alejandro, and Marybel Perez. “When an A is not an A in Academic Research, or How A-Journal List Metrics Inhibit Exploratory Behaviour In Academia.” Journal of Interdisciplinary Economics, vol 36, no 1, 2024, pp 105–121

Awasthi, Shipra. “Plagiarism and Academic Misconduct: A Systematic Review”

DESIDOC Journal of Library & Information Technology, vol. 39, no. 2, 2019, pp 94–100

Buck, Elisabeth H. “Conversations with Writing Center Scholars on the Status of Publication in the Twenty-First Century” Open-Access, Multimodality, and Writing Center Studies Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2017, pp. 93–110.

Conklin, Michael, and Satvir Singh “Triple-blind review as a solution to gender bias in academic publishing, a theoretical approach ” Studies in Higher Education, vol. 47, no. 12, 2022, pp. 2487–2496.

Drieschová, Alena “Failure, Persistence, Luck and Bias in Academic Publishing.” New Perspectives, vol. 28, no. 2, 2020, pp. 145–149

Herb, Maggie M., Liliana M. Naydan and Clint Gardner “Contingency and Its Intersections in Writing Centers: An Introduction.” The Writing Center Journal, vol 41, no 1, 2023

Lee, Sohui, Julie Prebel, and Elizabeth Kleinfeld. “Rethinking Publishing In Writing Center Studies: Imagining an Anti-Racist, Decolonial, Anti-Ableist Publishing Model ” International Writing Center

Association. Virtual Conference. October 20-23, 2021

Lockett, Alexandria. “Why I call it the Academic Ghetto: A Critical Examination of Race, Place, and Writing Centers ” Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, vol. 16, no. 2, 2019

Thien, Nguyen Hoang. “Reducing the Risk of Bias in Academic Publishing.” European Science Editing, vol 49, 2023, e90942

Praxis: A Writing Center Journal • Vol 23, No 1 (2025) www.praxisuwc.com

Candis Bond Augusta University cbond@augusta.edu

Abstract

Elisabeth H. Buck Fordham University ebuck7@fordham.edu

Why do writing center professionals, many of whom are not required to engage in scholarship, opt to go through the laborious process of publication? And what factors might facilitate or inhibit the publication process for authors in the discipline? To help answer these questions, we conducted a mixed-methods IRB-approved study consisting of a web-based survey (N=58) and follow-up virtual interviews with six writing center practitioners. We illustrate in this article a framework, grounded in quantitative and qualitative data, for fostering more inclusive practices for welcoming voices into published writing center spaces. We also provide insight into how publishing fosters writing center scholars’ positionality within a discipline and the extent to which the peer review process informs (and complicates) why writing center practitioners do or do not publish in the field.

Introduction

Our research here was born out of a semi-existential question: why do writing center professionals (WCPs) engage in scholarly work? In the current “post” pandemic educational context, where burnout and other issues impacting the retention of higher education faculty continue to dominate news cycles (Lederman; Lu), we wanted to better understand what motivates scholars to engage in research WCPs have written extensively about emotional labor, burnout, and wellness (Caswell et al.; Giaimo Unwell; Giaimo “Laboring”; Giaimo & Hashlamon; Giaimo et al ; Green; Jackson et al.; Lockett; Morris and Concannon; Webster; Wooten et al.) as well as marginalization (Denny et al ; Faison and Condon; Geller and Denny; Perryman-Clark and Craig; Wooten et al.), and yet, as evidenced by the very existence of these conversations, many continue to publish The question of motivation is especially prescient for WCPs, as their positions do not always require publication and are often tenuous or contingent. For example, the 2020-2021 Writing Center Research Project survey showed that only 25% (n=30) of 117 writing center administrators who responded were tenured or tenure-track (Purdue OWL). Those that participate in published writing center spaces thus generally do so because they have a choice, not a

Elizabeth Culatta Augusta University eculatta@augusta.edu

mandate We are publishing this article, in something of a meta-inquiry, because we sought to understand the breadth of WCPs’ reasons for pursuing scholarly publication, along with what could be equally important factors that discourage would-be researchers from participating in peer-reviewed spaces Elisabeth began to explore these questions in her 2017 book Open-Access, Multimodality, and Writing Center Studies Her robust survey of rhetoric and composition scholars yielded reasons for why researchers tend to publish in one journal over another, with respondents indicating that perceived prestige, scope or focus, and/or editorial board composition significantly impact a decision to submit to one journal over another (19-20). Even within the much narrower sub-field of writing center studies, WCPs have many choices about when, where, and how they participate in professional and scholarly conversations. Our current project seeks to expand on Elisabeth’s investigation by not only focusing more specifically on writers’ decisions and experiences in publishing their work, but also on how they conceptualize their labor and identities when they participate as reviewers of academic texts themselves In other words, how does the field’s publishing process impact WCPs’ sense of professional belonging and identity? Both experiences–submitting research and reviewing the scholarship of others–undoubtedly inform the extent to which scholars understand and conceptualize their role(s) and position(s) as professionals in a discipline

Our personal experiences in writing center publishing have significantly impacted our professional identities in both positive and negative ways–something we heard echoed anecdotally by other WCPs in informal conversations and through professional networking. At times, we experienced the editorial and peer review process as affirmative. The mentorship we received from reviewers and journal editors contributed to our sense of belonging in the writing center community and built up our confidence as experts in the field Similarly, serving as reviewers ourselves helped us develop as disciplinary mentors, shaped our disciplinary identities, and added to our sense of professional belonging. At other times, however, we found publishing in writing center

journals, and mentoring others through the publication process, challenging. We were discouraged by extended timelines and the intensive revision required, and sometimes the style of commentary felt opposed to the field’s pedagogical values. When we attended conferences and shared these experiences with other WCPs, we heard similar stories

As Elizabeth Kleinfeld, Sohui Lee, and Julie Prebel argue in Disruptive Stories: Amplifying Voices from the Writing Center Margins, writing center publishing practices are inherently tied to issues of diverse representation, access, inclusivity, and belonging Our own positions within writing center studies are very privileged Candis and Elisabeth are both white women who are tenured writing center directors and associate professors of English. (Elizabeth is also a white woman with tenure in the discipline of sociology.) Underrepresented and contingent WCPs are likely to experience additional barriers and challenges when they seek to publish in the field’s journals. Writing centers claim to be inclusive and welcoming spaces, and many writing center publications also tend to be particularly and outwardly conscious of a disciplinary tradition and praxis that is very attentive to accessibility When we began our study, an original goal was to better understand the extent to which the field’s publishing practices reflect or undermine these values, and the impact publishing practices have on WCPs’ sense of professional identity and belonging Due to the homogeneity of our sample, we ended up focusing less on professional identity and demographics and more on why writing center practitioners do or do not publish in the field

Below, you will find an overview of publishing practices in the field of writing center studies, followed by our study methods and results Our findings focus on why WCPs publish, including the advantages and challenges of publishing in the field We conclude with our interviewees’ ideas for improving writing center publishing practices. What we hope to illustrate is a framework, grounded in quantitative and qualitative data, for fostering more inclusive practices for welcoming writers into academic publishing. We also hope to provide insight into how authors and reviewers see themselves and the extent to which this serves as an extension of their positionality within a discipline Ultimately, we hope our findings provide pathways for making our scholarly platforms more inclusive, accessible, and diverse

Historically, writing centers have been led by a rather homogenous group. Reporting on director surveys dating from the 1950s, Valles et al point out that, since at least the 1990s, white women have accounted for 70-80% of writing center directors nationally. This was affirmed in their own 2014 director survey Out of 314 respondents, 71.5% identified as women; only 8.7% of participants identified as non-white, 3.2% identified as disabled, and 6 5% of respondents identified as LGBT These percentages were far below national averages for these communities (Valles et al ) Kleinfield and her colleagues link the field’s lack of diversity to inequitable publishing practices that exclude underrepresented and contingent WCPs from scholarly conversations Through a survey they conducted, they found that “writing center leadership (directors and coordinators) as well as writing center scholarship are not reflective of the current US population,” which should be “unsettling” considering that writing centers are “known for their wide range of institutional contexts and administrative roles” (14). Finding that publications trended toward white voices employed at high-status institutions, they note, “When the entire picture of who works in writing centers, how their positions are structured, and what models of writing center work they enact in their centers is shaped by a demographically narrow group of scholars, it is harder to imagine writing center work, scholarship, and models that look different from what is established as ‘normal’ or expected” (11)

The lack of authorial diversity in writing center publishing is exacerbated and perpetuated by the field’s insular citation practices (Lerner and Oddis) This insularity affects not just whom, but what gets published For example, although a valuable form of research, the field’s call for more RAD (replicable, aggregated, and data-driven) studies in the 2010s (Driscoll and Perdue) which requires significant time, resources, and institutional security to conduct may have made publication inaccessible to many underrepresented and contingent WCPs Although more than 70% of writing center directors are contingent (Isaacs and Knight), as Maggie M Herb et al observe in their special issue of Writing Center Journal on contingency, scholarship for and by contingent WCPs is lacking Kleinfield et al point out that, when a field is as homogenous as writing center studies, it is “harder for alternative voices to break the grand narratives that are shaped by scholarship” (11)

One of the main publishing practices that Kleinfield et al. critique is double-anonymous peer review. They cite multiple studies that show this practice privileges full-time tenure-track directors who are primarily white and work at secure, four-year research comprehensive institutions (Kleinfield et al 13-14) In response, Kleinfield et al offer their model of “activist editing,” which involves active recruitment of diverse authors and collaborative, non-anonymous mentorship to publication. Others have noted the limitations of the peer review process within the broader field of rhetoric and composition, drawing attention to the ways this practice is normalized in the field yet inconsistent in its delivery and purpose

In their 2019 article “A Study of the Practices and Responsibilities of Scholarly Peer Review in Rhetoric and Composition,” for example, Lars Sutherland and Jaci Wells interviewed 20 rhetoric and composition scholars and found that they were divided in their views on the purpose of peer review Some scholars felt that reviewing should work similarly to how the field teaches writing, focusing on collaborative relationships between authors and reviewers, while others felt that reviewers should “bluntly assess the merits of the author’s text” (118) The latter, they explain, is “out of respect to the author, who deserves to know how their work is received” (118). The former view focuses on process and providing a gateway to publication; it also focuses on developing a sense of community through relational dialogue The latter view takes a product-oriented approach and frames the peer review process as a vetting, or gatekeeping mechanism. Sutherland and Wells point out that these two perspectives were articulated at the 1995 Symposium on Peer Reviewing in Scholarly Journals in Rhetoric Review and have not changed much since now three decades later (118). Within the narrower sub-field of writing center studies, divided views on peer review take on heightened significance, since a gatekeeping model is in opposition to the field’s pedagogical praxis, which focuses on writing as a process, centering the author, and non-evaluative mentorship. Since 2020, some writing center journals have taken steps to create more accessible and inclusive publishing practices, including being more explicit about guidelines and expectations for reviewers and the feedback they provide to authors For example, in their section on “Scholarly Review Practices,” The Peer Review (TPR) commits to anti-racist, accessible, and inclusive reviewing practices (“About”). The journal provides reviewers with access to the document “Anti-Racist Scholarly Reviewing Practices: A Heuristic for Editors, Reviewers, and Authors,” which offers guidance in how

to engage in anti-racist reviewing and publishing practices. The journal also provides its own, in-house “Guidelines for Reviewers,” as well as an accessibility guide TPR is explicit about the purpose of the peer review process in its guidelines for reviewers, stating “our goal is to get just about every pertinent submission to publication, and, secondly, we expect our reviewers to offer feedback that allows the author(s) to grow and develop throughout the review process. In other words, our reviewers are invited to act like writing consultants.” The journal provides detailed instructions on how to give “encouraging” feedback to authors that is “useful,” “engaged,” “thoughtful,” and “actionable ”

Like TPR, Writing Center Journal (WCJ) refers reviewers to the Anti-Racist Scholarly Reviewing Practices heuristic The journal also offers its own “Guidance for Reviews” document, although this guidance is less clear than TPR’ s about the purpose and role of reviewers and does not mention inclusivity, accessibility, or anti-racism explicitly. The guidance does encourage reviewers to “practice the sorts of empathy and respect for writing in progress as we would in any writing center.” WLN: A Journal of Writing Center Scholarship, Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, and SDC: A Journal of Writing Center Studies do not post guidelines for reviewers on their websites, although WLN does ascribe to the WAC Clearinghouse’s “Commitment to Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Justice,” which includes promoting equitable publishing practices to “encourage greater representation across cultures, backgrounds, and viewpoints.” All writing center journals also provide reviewers with the option to leave comments that only the editors will see. This practice allows reviewers to express concerns to editors that will not be shared with authors directly Some journals, including Praxis, WLN, and TPR, request that reviewers share areas of specialization within writing center studies This practice theoretically ensures that an article is appropriately matched with a reviewer who is willing to disclose particular identities, interests, or experiences. Reviewers are also encouraged to decline a review if they do not feel they know enough about an article’s subject area

Although we are encouraged by shifting editorial and publishing practices in the field, we hope our study can also contribute to reshaping disciplinary publishing practices to make the field more inclusive, accessible, and diverse Our study offers insight into why WCPs publish, as well as how engaging with writing center journals influences their sense of professional identity and belonging Writing center journals and editors can use this information to think

Praxis: A Writing Center Journal • Vol 23, No 2 (2026) www.praxisuwc.com

critically about their practices, including whether they are serving WCPs well and helping them to meet their professional goals.

In order to learn more about writing scholars’ experiences with academic publishing, we conducted a mixed-methods study that included a web-based survey and follow-up virtual interviews To be included in the study, participants had to be at least 18 years of age and identify as a writing center professional who has received a review from a writing center journal and/or has served as a reviewer for one or more writing center journals “Writing center professional” was defined as someone who works professionally within writing centers as a director, assistant director, coordinator, or tutor/consultant “Writing center journal” referred to the following publications: Writing Center Journal, WLN: A Journal of Writing Center Scholarship, Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, The Peer Review, and Southern Discourse in the Center: A Journal of Multiliteracy and Innovation. “Reviewer” referred to having reviewed at least one time for one or more of the journals listed above Being a recipient of a review meant the participant had received at least one review from one or more of the journals listed above. “Review” referred to both peer and editorial reviews of submitted manuscripts.

We used Qualtrics to create an anonymous, web-based survey consisting of 43 closed and open-ended questions. Convenience and snowball sampling was used to solicit participants The survey was distributed electronically via email to the Writing Studies (writingstudies-l@listserv.nodak.edu) and Writing Center (wcenter@lyris ttu edu) list-servs The authors also emailed the survey directly to colleagues whom they thought might be interested in participating and encouraged them to share with others who fit the eligibility criteria. The authors also shared the survey on the Directors of Writing Centers and Writing Center Network Facebook pages.

Questions were categorized into four sections:

1 Experience working in writing centers

2 Experience receiving feedback from writing center journals

3 Experience giving feedback on submissions to writing center journals

4. Demographics

The survey contained a final question asking participants if they would be interested in participating

in a follow-up interview If participants responded “ yes ” to this question, they were prompted to provide a name and email address. Contact information was disaggregated from survey responses to protect participants’ anonymity and to reduce the chances of bias when selecting interviewees

We received 58 complete responses to our survey between July and August of 2022. Elizabeth used the software program STATA version 18 to analyze quantitative results. Forty-five respondents stated they had received reviews from writing center journals, while 42 stated they had given reviews for writing center journals. Unfortunately, although perhaps unsurprisingly considering what we know about the demographics of writing center studies as a discipline, the sample was fairly monolithic: 91% (n=51) were 35 years of age or older (50% of respondents were between the ages of 35 and 44); 91% (n=52) were white; and 67% (n=35) identified as cisgender women Eighty-four percent of respondents (n=49) held a leadership position within their respective writing center as a director, coordinator, or assistant/associate director/coordinator and 74% (n=43) had worked in writing centers for 10+ years. In other words, participants were experienced and advanced in their writing center careers. While our goal in this study was to promote inclusive, accessible practices, our findings fall short of providing insight into the experiences of underrepresented practitioners and scholars in the field However, our respondents still provide valuable information about disciplinary publishing that can be used to improve practices. Although the sample was monolithic in many ways, a clear distinction emerged between participants who were tenured or on the tenure track and those who were not Forty-seven percent of respondents (n=27) stated they were tenured or on the tenure track while 53% (n=31) stated they were in non-tenure track roles Those not on the tenure track identified as students, staff, adjunct/contingent faculty, non-tenure track faculty, and “other,” with the majority occupying staff roles (n=19). This split was interesting because it suggested that tenure-track status may not be the driving motive for engaging in scholarly publication within writing center studies. Tenure is frequently associated with research output as well as disciplinary identity and belonging, but it may not be a significant factor for writing center professionals who publish. This sparked our curiosity: Why were these folks publishing if they weren’t required to do so? This early observation also helped inform our process for selecting candidates for follow-up interviews since we knew we wanted to hear from both Praxis: A

tenured/tenure-track and non-tenured/tenure track respondents.

Twenty-six survey respondents stated they would be willing to participate in a follow-up interview We interviewed a total of six survey respondents–four women and two men–who held leadership positions within their writing centers as directors, associate directors, or coordinators. Three were in tenured/tenure-track positions and three held non-tenure-track roles. All the tenured/tenure-track interviewees stated that they were required to publish as part of their job, although one noted that they did not have to publish as part of their administrative assignment to direct the writing center–their publishing was connected to their faculty position in English literature. None of the non-tenure-track interviewees were required to publish as part of their writing center jobs.

Candis and Elisabeth conducted 45-60-minute interviews virtually over Zoom between November 2022 and March 2023. Interviews were recorded and Zoom’s transcription feature was enabled to allow the authors to accurately transcribe responses for analysis. After verbal consent was obtained, Candis and Elisabeth asked participants the following questions:

1. We want to know your story. Tell us about your experiences receiving reviews from writing center journals

2. How have these experiences impacted your perceptions of the field and your place within it?

3. Tell us about your experiences giving reviews for writing center journals

4. When you review, how do you perceive your ethos and purpose?

5 Is there anything you would change about the review process to make receiving reviews from writing center journals a more positive experience?

6. Is there anything you would change about the review process to promote diversity, equity, inclusion, and access within the field of writing center studies?

7 Several of our survey respondents noted they published even though their positions do not require it Can you tell us if your position requires you to publish? What motivates you to publish, especially if this isn’t a required component of your position?

8. Is there anything else you would like us to know that we didn’t ask you about?

After all interviews were completed, Candis and Elisabeth cleaned up and anonymized the Zoom transcripts and used a grounded theory approach to code the data manually using Excel spreadsheets A grounded theory approach meant we approached the data iteratively in several cycles without applying pre-existing codes or categories; instead, we identified concepts that led to codes and, later, categories emerged organically as we inductively analyzed the text (Saldana 1-2). Although we did not approach the data with pre-existing categories or themes in mind, we did prioritize our research questions and looked for emergent patterns related to reviewer ethos/approach, motivations for publishing, barriers to publishing, and recommendations for improving publishing practices During the first cycle of coding, Candis and Elisabeth chose one interview and each coded it independently to identify emergent categories. We used brief words and phrases to describe what we were seeing and took notes so that we could compare our interpretations of the data. We then met to review our independent coding results and discussed areas of agreement and difference After comparing our notes and initial results, we agreed upon a list of 13 categories and completed a second cycle of coding for this same interview (see Appendix B for a complete list of categories). After comparing our results for this second cycle, we agreed that we were on the same page when it came to interpreting the data, and Candis coded the remaining five interviews using the same method and list of categories After Candis completed coding, Elisabeth reviewed her work to ensure agreement and enhance reliability We used our coding results to develop the themes we discuss in the next section. After the full manuscript was drafted, Candis and Elisabeth assigned pseudonyms to the interview participants, and they were individually contacted to review the full article draft to verify that we represented their words accurately and authentically We also offered an opportunity to change their assigned pseudonym, if they desired Candis and Elisabeth also offered participants author credit, as promised in their consent process, but all six interviewees declined this offer and chose to remain anonymous.

In our results section, we share themes that emerged related to writing center professionals’ experiences publishing in the field We focus on their “whys,” beginning by discussing the positive advantages of

publishing in writing center journals followed by barriers and challenges.

Activism, Joy, and Gaining “Street Cred”

We were curious to learn why WCPs publish, especially when their positions frequently do not require them to do research, or to do research specifically on/in writing centers Historically, writing centers have been perceived as marginalized or under-resourced spaces, and yet, WCPs are often prolific writers and researchers Our interviewees shared several sources of motivation. Only one of our participants, notably an interviewee with tenure, expressed financial motivations for publishing, but as a “first-generation college student” who “grew up poor” it was difficult for him to not see publication as the best way to “get that next pay bump” (David). Several interview participants opted to pursue publication to give themselves–and perhaps by extension their affiliated centers–credibility in the eyes of the institution. Khloe illustrates this argument succinctly: “in the institutions where I've been that have been very hierarchical, and have had a heavy faculty-staff divide, being able to show that I have just as many publications [as many faculty members] gains me street cred with them.” The idea that publication brings a specific form of institutional cachet can be especially significant for non-tenure track directors. Khloe in particular saw her publication record as a means of combating the tendency of certain parties to see the writing center director as a “ a literal servant to the university [that is] there to meet their needs ” She also saw her research as a means of resisting the legacy publication model where white male scholars were able to publish prolifically largely due to their wives’ unseen and uncredited labor. For Khloe, the ability to publish despite both her heavy administrative workload and no obligation to do so renders her research a “weapon” against these standards. “I also don't feel like there's any choice in some contexts,” Khloe says about her use of the term “weapon” to describe her publication record; it exists within the arsenal of her other professionalizing experiences: I guess it evens things out when faculty members are like, ‘Oh, well, you're just staff You don't understand what it's like ’ No, I carry a half time faculty load, teaching just as many students as you are I'm having way more one-to-one contact [with them]. I've published. I'm presenting at these conferences, and I'm an invited speaker at these places What do you bring to the table?

For Khloe in particular, the concrete evidence that she has engaged in as much academic labor as her tenure-track or tenured colleagues helps to importantly cohere her institutional ethos, and publishing exists as perhaps the most visible and legible manifestation of this labor

Other interview participants saw their publication efforts as specifically motivated by activism Bella felt her efforts to publish about the experiences of first-generation students and labor issues were especially significant: “I’m contributing something that might actually positively benefit somebody.” Bella does have some percentage of her workload allocated toward research but also sees it as essential to her role as writing center director “For me, personally, it’s a very important part of me being in the field,” Bella noted whilst also echoing Khloe in suggesting that publishing research is a critical way “to demonstrate to the University how we're doing.” Another interview participant also saw activism in publication as extending to mentoring students through the research process On this point, Josie notes that “I try to include students in conference presentations and publications…I let students know if they're interested in research, they can reach out to me.” Josie sees publication and research as an important way to validate tutors’ experiences and stories by demonstrating “that people want to learn from them.” Janelle also shared the importance of mentoring graduate students through publication efforts, even if such efforts are challenging “I really want those positions to offer as rich a professional development experience for the graduate students as is possible,” she noted and working through the publication process with a writing center director mentor can be one of the most fruitful professionalizing experiences. Engaging students in research efforts can be seen as another way to showcase writing centers as spaces for developing academic skill-sets, thereby also contributing to the writing center’s reputation as a site for robust intellectual inquiry. It is significant that participants see their motivation for publishing as having meaning beyond their own professional reputation Writing center directors, by virtue of their close and unique work with students, can play a role in modeling how anecdotal experiences, when shared through story and research, can lead to rigorous inquiry and significant results Mentoring lets writers know that they have an important perspective worth sharing, which in and of itself is a form of activism within the academy. Another motivation for publishing emerged, quite simply, from the joy of participating in writing

Praxis: A Writing Center Journal • Vol 23, No 2 (2026) www.praxisuwc.com

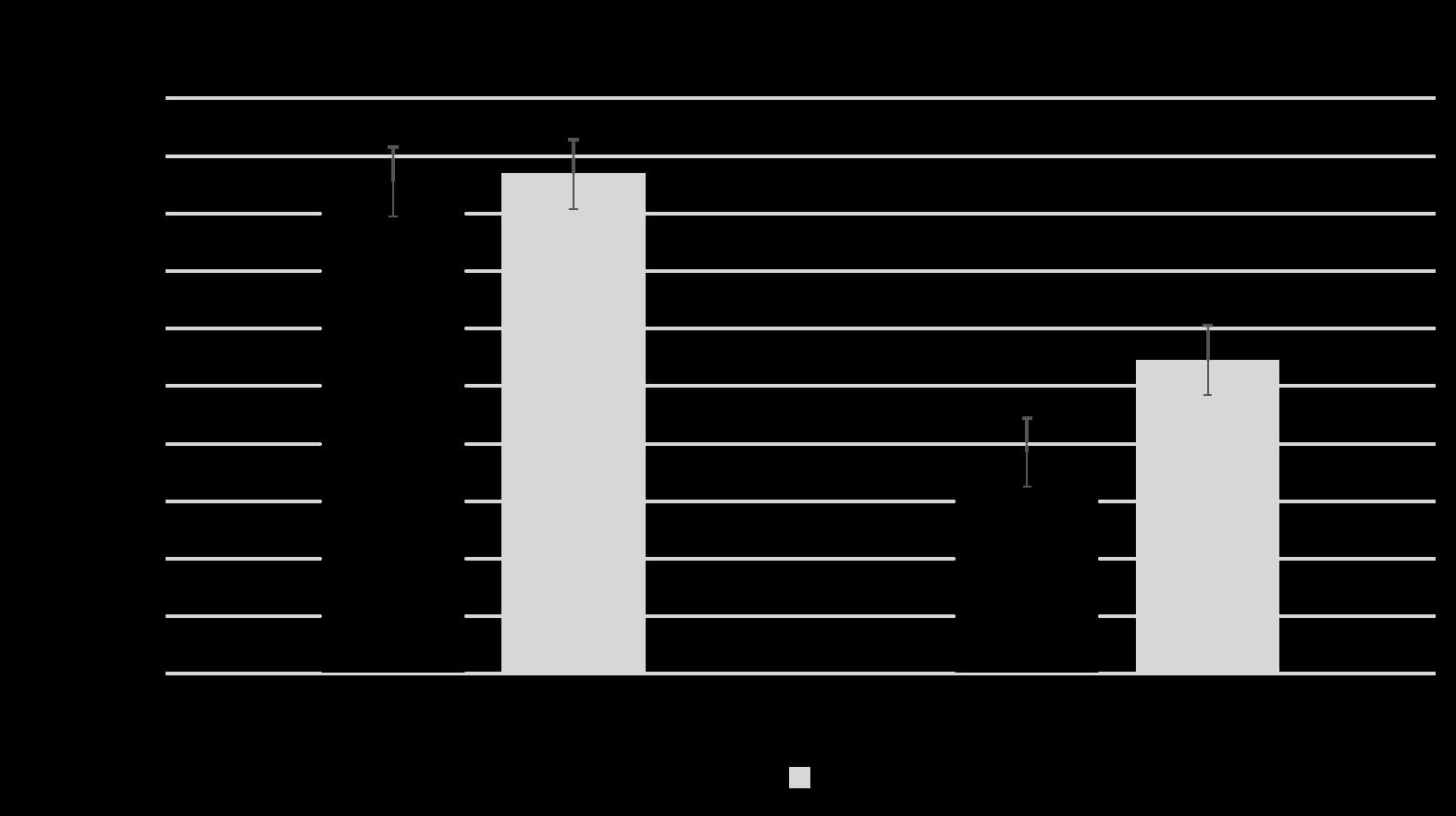

center conversations, especially with other like-minded professionals. WCPs seem to find a sense of self, place, and belonging through publication. This finding was borne out in quantitative survey results as well as in interviews. Thirty-seven percent (n=17) of respondents somewhat or strongly agreed that receiving reviews “affirms [their] professional identity” and 69% (n=31) somewhat or strongly agreed that receiving reviews “positively contributes to [their] professional development.” Fifty five percent (n=25) of survey respondents reported that receiving peer/editor reviews “make me feel welcome in the field of writing center studies,” while fifty one percent of survey respondents also somewhat or strongly agreed that “receiving reviews from writing center journals has been a positive experience.”

Our interview participants provided examples of these positive experiences. Colin said that “for me, [engaging in research] is kind of fun. It's a source of creative expression and just allows me to kind of cultivate ideas that often feed back into my teaching, feed back into my writing center work and administration ” For David, participating in writing center research can be a way to connect with others, which took on new meaning post-pandemic “If I do anything now, ” David says, “I want it to be because I'm working with people I like working with...and getting to have chats with some folks like, maybe this could be a conference talk we could do together. Maybe I can convince this person to write an article together, because they're really cool ” Josie argues that the space of the writing center inherently inspires engagement with research, as “I find [the experiences I have every day in the writing center] really interesting and engaging, and [they] make me want to learn more and read more, and study more Those everyday experiences feel to me like really valuable places of inquiry” As these comments make clear, writing center research provides space for creativity and camaraderie

That the site of our labor (i.e., the writing center) can itself be a source of inspiration to engage in research is perhaps unique to our profession. Yet, throughout their conversations with us, a number of participants shared that, despite whatever difficulties they have encountered both professionally and institutionally as writing center constituents, their enthusiasm for and commitment to the value of writing centers was a strong motivation for engaging in the discipline as a publishing professional: “It's kind of where my bliss is. I didn't intend to be a writing center person, but when I fell into a directorship, I loved it again I think that's very common” (David) The belief in the value of writing centers, and research’s ability to

convey and articulate that value, thus emerges as perhaps the strongest motivation to publish in the field.

During our interviews, it became clear that publishing in writing center journals offered participants more than a line on their CVs. Over and over, interviewees focused on the collaborative, encouraging mentorship they received from reviewers and editors, and they noted the ways writing center publications offered a “gentle introduction to scholarly publishing” (Khloe) by taking time to demystify disciplinary conversations, genre conventions, and audience expectations. This approach contrasted noticeably to publishing practices participants had observed in other adjacent disciplines, including literature, linguistics, and rhetoric and composition The way authors and reviewers described the writing center publication process may offer an explanation for why so many writing center professionals publish, even if it is not required by their position–publishing seems to function as a form of relationship and community-building, as it also serves to teach the ins and outs of a specialized field in ways that lend credibility and legitimacy to directors and their centers

As they recalled their early publishing experiences, interviewees expressed appreciation for reviewers and editors who took time to coach them through a collaborative process. For example, Khloe stated that, as a late grad student, she struggled with her first writing center publication, especially “trying to make it feel very scholarly,” but, after receiving anonymous peer reviews, the editor of the journal “worked with us in a Zoom format…and kind of coached me and my writing partner through some pretty massive revisions ” Khloe explained that this editorial coaching “ gave us a chance to ask questions about what the reviewers had said and clarify what [the journal] was looking for.” The coaching offered by reviewers and editors also helped authors navigate new audiences and disciplinary expectations For example, Bella noted her first writing center journal peer reviewers were “really good at addressing genre conventions… They’re like, okay You want to pull your results out a little separately from your analysis a bit more, and that kind of thing where I was like, okay, this is stuff that’s really helpful for me, just in terms of figuring out the genre, and that helps me in terms of my professional identity and figuring out my ability to write in these different academic genres.” This kind of

collaborative coaching helps new professionals transition into the discipline and gain expertise. Several participants also appreciated the extra coaching journal editors offered authors after peer reviews came in. This is a step in the publication process that seems to be a hallmark of writing center studies–editors are willing to act as gateways to publication and offer an extensive amount of time to coach authors through the revision process David, for example, shared an early-career publication story that showcased how editorial mentoring helped him “traverse that threshold” from graduate student writer to published professional. He said:

[The editors] really beat that manuscript up, but in a very kind way that was a really formative experience for me. I really felt I was being apprenticed in a lot of ways, and it just helped. They were really patient. They let me go back and forth with them. And so it was a really positive experience It took a minute, but I was really proud of that piece when it came out

The “back and forth” that David mentioned was also appreciated by Colin, who praised reviewers’ “supportive” and “positive” comments that often “had nothing to do with things they thought needed to change.” Instead, it was a “collegial interaction.” He said, “We’re all writing center people, and we’re having a conversation, and you know, as part of our discipline, right?” Several interviewees mentioned the positive impact of reviewers and editors who treat feedback as a form of mentorship. For example, Josie said, “I’ve found a lot of mentorship and a lot of work with people to, I guess, enhance and make the work better.”

Josie noted this form of collaboration is especially helpful for student and novice authors in the field:

Having [a] collaborative feedback model was really helpful for showing [students] the process of publication, and that, even when you're publishing something, multiple people are looking at your work So it's not just one person, and I think that that…sort of helped demystify the publication process… there are sometimes conflicting pieces of feedback you have to work through, and there's a lot of navigating involved But, like I said, I think it's really supportive, and that kind of furthers my idea of what the writing center field is: being supportive, being mentoring, being encouraging of new voices and student publications.

Interview participants whose disciplinary background was not in rhetoric and composition or writing center studies were even more mindful of a need for coaching during the publication process, especially if the field wants to be inclusive of voices from underrepresented communities and those in positions that do not support research Janelle, whose background is in the arts, received negative reviewer feedback and an article rejection from a writing center publication early in her first job as a writing center coordinator. The feedback was not encouraging and focused on a lack of engagement with disciplinary scholarship and past conversations. She said it “ was challenging to receive that [negative] feedback,” but it “ was also really useful to recognize, oh, this is a field unto itself There is scholarship here that needs to be respected.” She said, “I don’t think [our manuscript/research] was naive, but I think that was the reception of it. It was received as, ‘Oh, yes, you just, there, there. You’re excited about your ideas that we ’ ve all already had ’” For WCPs like Janelle, coaching could offer a way into the discipline rather than closing doors Although some interviewees had experiences with negative reviewer feedback, most focused on positive experiences grounded in a spirit of collaboration and mentorship In our survey, 58% (n=26) of respondents somewhat or strongly agreed that the reviewer comments they received on their own work “promoted the field’s values of writer-centered, process-oriented, equitable writing instruction.” Participants’ generally positive experiences with reviewer feedback aligned with the way interviewees described their approach to reviewer work Most stated they aimed to mentor authors by providing pathways to publication and intentionally avoided taking a gatekeeping approach to promote equity For example, none of our survey respondents disagreed (and 38% strongly agreed) with the statement “my reviews promote equitable publishing practices in the discipline of writing center studies ” In her interview, Josie elaborated, explaining that she strives to be a “mentor guide” when she reviews Since many writing center scholars are new to the field and may not be familiar with the scholarly conversation, she tries to “give [authors] access to resources” “if there are certain people they should be talking about” or if they are “not signaling foundational scholarship” rather than “shut[ting] them down” because they’re “not citing the right people.” She does not want writers to feel excluded or “defeated” because they “didn’t know who the right people were” to include. She also tries to find “strength and points of encouragement” while “emphasizing the value of the piece as a whole” and telling them “they do have really important

Praxis: A Writing Center Journal • Vol 23, No 2 (2026) www.praxisuwc.com

contributions to make ” Similarly, Khloe said “I would much rather see us work with writers to build them up and make sure things are getting in rather than rejecting them and just sending them on the way I think that that contributes to the mentoring. I'm hoping that the feedback I've given makes people feel welcome and makes their ideas feel valued ” David thinks reviewing is “really about mentoring someone and making sure they kind of understand the ‘Why’s’ of [the requested revisions] rather than just kind of tearing [the draft] down.” Bella said she sees herself as a “helper,” and she tries to be conscious of the background and experience level of authors she reviews so she can tailor the amount and type of feedback she offers to be the most encouraging and useful as possible.

Colin also views his role as reviewer to be one of inclusion and initiation rather than exclusion and gatekeeping. He said,

I think [reviewing and publication] is kind of, in a sense, a process of initiation. If it's with people that are less experienced, because I just think a lot of us well, just a lot of us are insanely busy. A lot of people in our field maybe didn't professionally identify as writing center people when they started their jobs. They're just keeping their nose down and are just trying to keep things under control And so sometimes there can be a kind of tunnel vision or myopia, where they'll be presenting something that's actually they're presenting something local, and they're presenting something as if it's this amazing discovery that no one has ever talked about. And then when you're giving feedback, you have to be like, oh, here, actually, we ' ve been talking about this Why don't you talk about that, too? How does this fit into this ongoing discussion we ' ve been having, right? And so part of that is about, like I said, sort of welcoming people into the community and transferring membership and trying to situate them within a, you know, a much bigger kind of scholarly discussion. Overall, our participants prioritized mentorship when reviewing and saw it as central to the reviewer role. Even when a piece is not a good fit for a particular journal, Bella tries to offer the authors a path toward publication by suggesting other publishing venues She explains, “I have read things [as a reviewer] that…I felt had interesting things to say but were not a right fit for the journal…and that's always tough, because I want them to understand their work is important. It just doesn't fit…this journal. And that's a

situation where I try to be really encouraging of, like, here's why I think it would fit better for this [other] publication or this [other] publication.” Bella’s comments indicate how committed she is to empowering writers’ voices, a theme other participants echoed

Several interviewees explained that they tried to stay true to writing center pedagogy and practices when they reviewed by being author-centered and serving as gateways rather than gatekeepers. They approached reviewing with a mindset of positivity and curiosity Khloe, for example, said she tries “to approach [reviewing]” by using “the same strategies that I would use as a writing center tutor” by asking open-ended questions David also “appl[ies] a writing center ethos” in his reviews by asking questions and responding as a reader He will ask, “How might a reader who believes in X or Y respond to what's related here?” Similarly, Janelle sees reviewing “ as an extension of [her] work in the writing center” and tries to “respond as a particular, situated reader.” She says, “I think of myself as a champion of the piece Basically, I always approach reading something as a peer reviewer from the stance of, I want to see this published And what can I offer? What do I see when I read this that I think will help to move it a next step forward?” She described her role as sitting in this space between, and responding to what is there, and also what could be there, what is not yet there So there’s also this, like, coming to be-ness of the writing, and so I guess I see the peer reviewer role very similarly to that, which is that we’re sitting between the expectations of the journal and the publication, and the piece of writing and the author, and we kind of have obligations to both of those things, and to respond to where they intersect, and where they might diverge I think I approach it more in line with my writing center work, where I think, okay, I have a responsibility to what is the expectation of the journal, but I also have a responsibility to meet this author and their piece of writing, and to be curious and inquiring about what are they trying to do. And maybe that’s something that the journal has never seen before or didn’t account for in their expectations, because it’s not a way that people have felt they could write before, or, you know, or maybe they just, maybe the author doesn’t know, but maybe they do know, and they’re challenging something on purpose…I think that does play into how I Praxis: A Writing Center Journal • Vol 23, No 2 (2026) www.praxisuwc.com

talk to tutors about, sort of, what is our role [in the writing center]...because our role isn’t to fix anything or assume the writing is broken from the outset, but it is to champion the writer to feel ready to hand in their best work, and I think that, to me, that would be a great thing for peer reviewers [for writing center journals] to think of their role as, like, how do I champion this writing and this writer to publish their best work, or choose not to, if they want?

Janelle’s comments capture a potential rather than deficit-oriented perspective that seems common among writing center reviewers

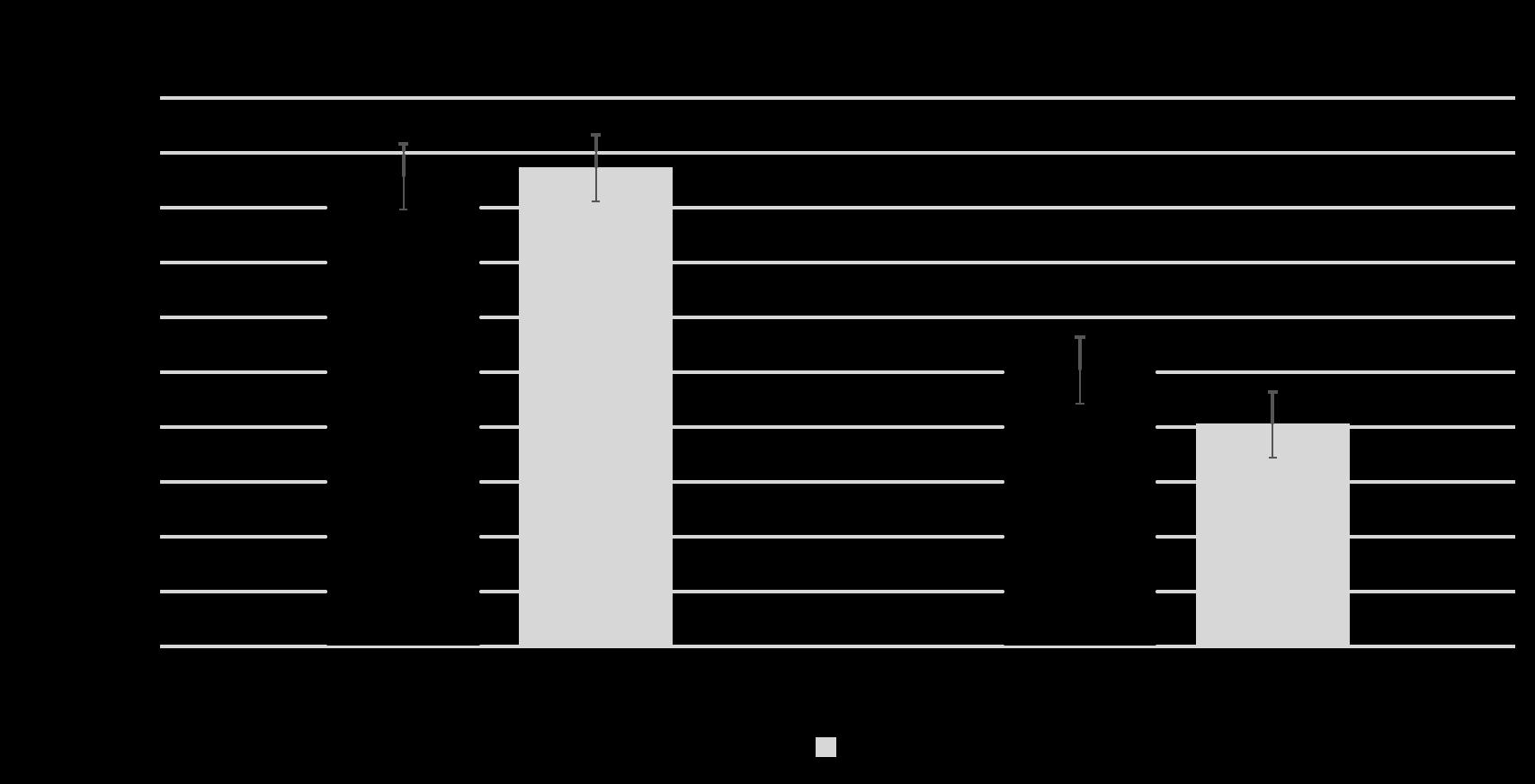

Overall, reviewers emphasized a focus on the writer–not just the writing, and they took a process, revision-oriented rather than product-oriented approach in their feedback. Indeed, 83% (n=35) of survey respondents somewhat or strongly agreed that their own reviews for writing center journals are “writer-centered” and 79% (n = 33) of respondents somewhat or strongly agreed that they would describe their own reviews as “process oriented ” As Colin noted, “writing center people tend to give pretty nurturing, supportive feedback [in reviews], even when they’re being critical.” Many of our interviewees noted that this approach to publication contributed to their sense of belonging in the discipline and academe more broadly. Khloe, for instance, said, “I feel like the accessibility and kindness of the majority of the reviewers in writing centers makes it so that I want to stay in this field. I want to stay in academia. I don't feel like anything is false or overly elevated, or extra elitist in that process, and that was something I was really afraid of when I started publishing.” Moving into the role of supportive, writer-centric reviewer seemed just as formative for our participants as did receiving reviews, potentially motivating them to remain active in publishing themselves Our survey results indicated that providing reviews to writing journals was important to respondents’ development of professional identity (81% somewhat or strongly agreed) and fosters their sense of belonging within the field (83% somewhat or strongly agreed)

As implied in the previous section, imposter syndrome (which can admittedly strike at any stage of one ’ s career) and learning a new, specialized discipline can act as barriers to publication in writing center studies. In addition to these potential barriers, participants commented on several others, including lack of time, resources, and support; the ways writing center

reviewer and editor ethos can extend the publication process for too long, leading to frustration, delays, and, sometimes, thwarted or wasted efforts; and a disconnect between the ways work is received at conferences and other informal venues as compared to its reception in scholarly journals, a disconnect that can also lead to extended timelines to publication and discouragement from publishing altogether.

Many participants, especially those in staff and non-tenure-track roles, stated they did not have the structural support or time needed to publish. For example, Janelle said she “didn't necessarily think about [publishing…] because I was still working, busy, and stuff, but just recognizing that there were people in writing centers who had the kinds of positions that allowed them to do much more scholarly type work, like do studies and get ethics approval, and that kind of thing, and be faculty members and do that kind of work. And that was not the kind of position that I had ” Bella also acknowledged the competing demands on directors’ time that can make publishing difficult. She “understands why people wouldn't [publish] Because it is incredibly time consuming And you know our center's been crazy busy this semester, and we ' ve had a million workshop requests And so it’s like, when things are like this, it's like, yeah, how would you have time for [publishing] on top of everything else.” She went on to say, “it's tough when [research and publication is] a relatively small percentage of what you're supposed to be doing for your job, but it's also something you really care about It's like, ‘Okay, How am I gonna manage this?’” Similarly, Khloe stated that it is difficult to “balance in writing time and publication” when writing center directors’ roles are often filled “with turmoil” and “up in the air.” Yet, she notes that they must “carve out time” to publish in order to maintain their credibility on campus: “when people are questioning my professionalism, where people are questioning my belonging in a university or the existence of my line, or if I'm a teacher (right now I'm arguing for faculty status at my institution), and one of the things I have is, ‘well, I've actually published more than the majority of your core faculty, who haven't published at all since they started working here Here are the plans that I have for my research agenda[ ] I think that is helpful ’” These concerns are of particular significance in a higher education landscape where contingency is the norm and the value of research is being called into question

While participants appreciated mentorship throughout the publication process, they also noted it could lead to delays and overly extended timelines that further discouraged them from publishing. In some

cases, authors revised extensively through several rounds of peer review, only to have their piece rejected. For example, Bella explained that a manuscript was “reviewed [and revised] three times and ultimately rejected.” Bella noted she was “unhappy, to say the least, at the end” and would have preferred it if the journal would have rejected the article at the beginning “because I ended up spending a year and a half on this thing that will probably never see the light of day, because I have no interest in going back to it at this point.” Similarly, David submitted a piece to the same journal and was asked to revise and resubmit After revising substantially, the piece had to go to new reviewers because the original reviewers were unavailable The new reviewers asked for many of the revisions to be reverted, so David made substantial revisions again and sent it back for a third round of review. After “months of radio silence,” the piece was rejected. David decided to submit the manuscript to a different writing center journal and went through two additional rounds of peer review there, only for the journal to become unresponsive for more than 10 months At the time of our interview–nearly four years after he had submitted his first draft to the first journal–his piece remained unpublished, and he had not heard back from the editors of the second journal. David called his experience “disheartening,” and while many factors, including inconsistent communication, backlogs, and reviewer turnover were involved, he also pointed to the mentorship model of reviewing as a potential stumbling block for authors Writing center journals, he stated, have “almost cultivated a culture of hyper revision at that level where you know it’s almost micromanagement in some ways ” (David).

While long timelines to publication and unresponsive journals are exasperating, they can also have tangible negative effects on scholars’ careers and can limit access and representation in the field Long timelines to publication and extensive coaching through revisions can discourage newcomers and marginalized scholars from entering disciplinary conversations. David noted, “There needs to be a decent enough turnaround time” so we can get people, especially students and those new to the field, “acquainted with [publication], and to get a sense of what [the discipline] looks like” (David) Long timelines can also hinder career advancement During the four years David waited to hear about his manuscript, he had gone up for tenure and promotion–without this publication on his CV. While this did not affect his case, it can have serious repercussions for many academics In a different situation, for example, David decided to pull a

manuscript from a writing center journal because the editors had been unresponsive for more than a year and their co-author did need the publication for their tenure and promotion dossier When they resubmitted the essay to a general education journal, the co-authors received “feedback right away ” David lamented, “it sucked because I really believed in that piece But there were material consequences for it not going through, and we had to make sure [my co-author] got [it] through [to publication for tenure]” (David). Many participants also commented on the role of writing center conferences in publication Most spoke highly of the feedback they received at these conferences and were grateful for activities such as publishing workshops and journal editor meet-and-greets. However, one participant observed that writing center conferences can set up unrealistic expectations for the publishing experience, which can also slow down the publishing timeline and be discouraging to newer authors She stated, “it does feel like we end up having very different scholarly conversations, right, in a conference, which I hope we think of as part of our scholarly conversation that we have in our profession...some of them are very ‘scholarly’ scholarship and research and RAD…presentations. But we also have a lot more scope and space for human-to-human and curiosity about, like, ‘oh, what happens in your center? Our center is different.’ And then it doesn't feel like there's a lot of space for that in publications, which is, I don't know, maybe a bit odd” (Janelle) She went on to explain: “writing center conferences and professional associations [are] so welcoming, and are like, “ yes, great presentation about this stuff that you're doing…just tell us about your program.’ [...] And then [there is a very different] response to a publication, which is like, ‘where's the scholarship, it needs to be grounded in the scholarship,’ which is not the experience we had at conferences or in other professional associations ” She expressed how this can be discouraging and “ a bit jarring” (Janelle) Although none of the other interviewees spoke about this disconnect, it resonated with the two first authors who have both had similar experiences where their work was received much more positively at writing center conferences than it was in the peer review process

While participants spoke at length about the advantages and challenges associated with publishing in writing center journals, they also mentioned several ways to improve the publication experience, especially

for underrepresented, contingent, and novice authors In this conclusion, we share some of the ideas expressed by our respondents, including recruiting diverse reviewer pools, being more intentional about timelines to publication and integration of technology, and providing more extensive training for peer reviewers

A primary motivation for engaging in this project was to consider how our participants’ perspectives could support recommendations for a more inclusive and accessible publication experience–both within writing centers and across broader academic contexts Many of our interviewees spoke about the extent to which engaging in writing center research as both a reviewer and a participant contributed to their own sense of belonging, especially vis-a-vis reviewing practices that enable reviewers to draw on their own identities and experiences. Khloe notes that, “I'm white. I'm queer. I'm a child of first-generation immigrants and I felt super great about being recruited into reviewing To me that was a compliment.” For others, however, this recruitment might be more complicated if one is regularly asked to take on this labor due to specific identities or experiences, as Khloe describes: I carry a lot of white guilt around and feel like it's my job to review for free, and to contribute for free, because I have profited so much off of the system I don't feel the same way for people who have more intersectionalities than I do, who have been historically excluded or oppressed. I think that being able to seek out those scholars and offer them honorariums for their work is really important, particularly because they're being asked to do so much of [this] I know that's making a broad, sweeping generalization, but it's what I’m observing for my colleagues of color, who are constantly being tapped for their input in terms of inclusive or DEI articles.

Compensating peer reviewers is certainly not a new proposition, and it is one that most journals would probably happily participate in with robust institutional or external support. Sylvia Goodman’s 2022 Chronicle article, “Is it Time to Pay Peer Reviewers?” posits that pay and more institutional recognition would significantly increase motivation for engaging in peer review labor, but writing center journals tend to exemplify a lack of substantive support, perhaps even more so than other publications in the humanities Yet still, if making sure that pieces are reviewed by the

most diverse possible editorial team is a priority, then attention must be paid to how this labor is compensated and recognized.

Writing center reviewers, as both our literature review and survey results illustrate, tend to be a particularly homogeneous population, and Colin rather dryly notes, “We're a very white field, and, interestingly, we're also a very feminized field, right? So, actually, as a guy, like, it's like, oh, my gosh, I'm diverse, yay! Believe me, I don't think we need to do anything to make our field more inclusive of, you know, cis-het, straight white men, like, we got our, you know, we have plenty of venues for that.” Colin’s point–that writing center studies tends to center the perspective of white women–certainly has an impact on the kinds of scholarship that we produce and the way(s) that it is reviewed, as Kleinfield et al have demonstrated so aptly. It is an oversimplification of a complicated problem to suggest that the field would benefit from a pool of more diverse voices, but it should be a serious consideration for any journal editor on how to recruit a diverse editorial team and make that labor legible Kleinfield et al ’ s “activist editing” model may also work for reviewers, but a field’s practices do not necessarily make a dent in wider systemic inequities that continue to devalue and underpay the labor associated with editing, reviewing, and, for many, authorship Khloe suggests that “more conversation about how we talk about and how we use the reviewing process in our professional portfolios” might be one way to accomplish this, if reviewers are given space to robustly explain their labor as reviewers within their institutional review process Taking this a step further, editors of journals could narrativize the reviewer’s labor and the impact it had on the publication of a piece This narrative could be a component to submit with an annual review and/or a tenure and promotion file In any case, the ways that reviewing labor is recognized and compensated should certainly be at the center of editorial conversations, especially regarding increasing the diversity of reviewing pools

As indicated in the previous section, many of our participants noted that complicated and confusing timelines contributed to their negative publication experiences Many suggested, however, that more streamlined tools and guidelines for the reviewing process might contribute to a smoother and more expedient publication experience. Bella explained, “I think, having clear guidelines for reviewers is really necessary In some instances, I've gotten that and other instances, I haven’t as a reviewer. When I do get