A Wild Promise

AN INTRODUCTORY ESSAY

TERRY TEMPEST WILLIAMS

n the fiftieth anniversary of the Endangered Species Act, I am thinking about extinction and what that means for a creature, a living being, to vanish from existence. Say their names: great auk, passenger pigeon, Carolina parakeet, Steller’s sea cow, Caribbean monk seal, Great Plains wolf, Puerto Rican long-nosed bat, Maryland darter, Utah lake sculpin, Labrador duck, heath hen, Bachman’s warbler, Xerces blue butterfly, Wyoming toad, and Panamanian golden frog—all extinct beginning in the 1800s to present.

Imagine an individual animal or insect or plant—alone—reaching, wandering, wondering, if they are the last of the living members of their kind. Certainly, they must know, sense, or fear this fact. What must it be like to surrender to one’s isolation by way of howl or cry or flight or bloom to attract a response, a glimmer or glint of kin?

The Sixth Extinction is upon us. It is true, species extinction has been a natural part of the Earth’s evolutionary history, as evidenced with the disappearance of dinosaurs in the Cretaceous Era, sixty-five million years ago, to the extinctions of the great megafauna such as mammoths and mastodons in the late Pleistocene Era who inhabited the last ice age some 10,000 years ago. But scientists today report an accelerated loss of biodiversity 1,000 times faster than the natural rate of approximately one to five species annually.

1

Now on the brink of extinction in North America are the red wolf, wood bison, grizzly bear, black-footed ferret, California condor, ocelot, Florida manatee, northern fur seal, loggerhead turtle, green sea turtle, giant sea bass, Oregon spotted frog, O‘ahu tree snail, rusty-patched bumblebee, Hine’s emerald dragonfly, Kirtland warbler, Eskimo curlew, wood stork, willow flycatcher, North Atlantic right whale, beluga whale, and elkhorn coral.

Loneliness inhabits my body as I whisper the names of the extinct and endangered, something better to do in a circle as ceremony, as we pay our respects and contemplate their lives together. How are we to survive without our companion species on Planet Earth? We are not above them or below them—but side by side—fellow creatures caught in a web of uncertainty in this era of the Anthropocene where our human footprint lands heavy on the Earth.

Grief is part of extinction that when understood and witnessed becomes an emotion that parallels love. When the last Rabbs’ fringe-limbed tree frog died in the care of the Atlanta Botanical Gardens on September 26, 2016, I wept. I had visited the Atlanta Botanical Gardens that year and knew the single remaining member of this species, tenderly named “Toughie,” was holding on—his call penetrated the walls of the Gardens—but there was never a call back in response. He was an Endling.

Today, over 1,400 species appear on the Endangered Species list under the jurisdiction of the United States Fish & Wildlife Service, all part of the Endangered Species Act signed into law on December 28, 1973, by President Richard M. Nixon.

President Nixon wrote, “This legislation provides the Federal Government with the needed authority to protect an irreplaceable part of our natural heritage— threatened wildlife.” Just before putting his pen to paper to seal this landmark act, he said, “Nothing is more priceless and more worthy of preservation than the rich array of animal life with which our country has been blessed.”

The Endangered Species Act was introduced in the United States House of Representatives and the Senate by Congressman John Dingle and Senator Mark Hatfield. It passed the House in an overwhelming majority with only four opposing votes. The Senate vote was unanimous. Hard to imagine in this current period of political divisions; harder still to imagine this act of compassion for all living beings remains intact despite previous polarizing times. It is a testament to the moral vision adopted by

2

Congress with a collective commitment to the continuing health of vulnerable species and securing a livable future of all generations—winged, hoofed, scaled, and rooted.

Fifty years since its inception, there has been a gradual erosion of the Act. In 1978, when a three-inch perch known as the snail darter was listed as an endangered species, it collided mightily with the Tennessee Valley Authority’s construction of the Tellico Dam. The Endangered Species Act halted the project. This was more than David taking on Goliath. This was a tiny fish swimming in the way of a monstrous water project. The spotted owl in the forests of the Pacific Northwest was threatened by wholesale clearcuts during the 1990s, igniting the timber wars between loggers and environmentalists. Lines were drawn. Violence threatened environmental activists choosing to live in the upper canopies of redwood trees as a protest. Trees were spiked to teach anyone with a chainsaw a lesson: “Hands off old-growth forests.” Any sort of amiable agreement was at loggerheads. Thankfully, solid legal ground was held for both the spotted owl and snail darter, and their endangered status was upheld by science and the courts. In time, solutions were sought through arduous negotiations discussing issues and process. Common ground was eventually found, and in some cases, even consensus.

During the terms of President Ronald Reagan and George Herbert Bush, amendments were made to the Endangered Species Act including the formation of a “God Squad” comprised of federal arbiters appointed to balance the common good of capitalism with the survival of a species. It, too, was not without its controversy and contentions. In the American West, where states like Nevada and Utah have a higher percentage of public lands (owned by the federal government) than private lands, a “sagebrush rebellion” ensued, still alive as witnessed by the Bundy standoff at the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge in 2014. The fight over the rights of private land owners and the rights of the federal government to oversee and protect threatened species continues. The battle between ecology and economy persists, but the Endangered Species Act of 1973 endures.

How do we place a monetary value on what one wild life is worth—let alone the value of a species’ right to continue when weighed against the perfection of adaptive evolution over time? Do we gauge it through dollars per board feet, or the millennial standing of a redwood forest? Do we approve one more golf course in the desert, or act

3

on behalf of a community of threatened Utah prairie dogs in times of drought? How do we balance the health of a declining grizzly bear population against the wealth of private land owners in a state like Montana and with a desire for a second or third home in Paradise Valley? Respect, restraint, and accommodating the rights of other species continue to butt up against the individual dreams and desires of humans.

The International Union of Concern for Nature (IUCN) has a “red data book” that is the gold standard for the “global extinction risk status of animal, fungus, and plant species.” It is known as the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, established in 1964 and updated continuously. We know, through shared science from governments around that world, that biodiversity is on the decline. In 2022, the IUCN has registered more than 142,500 species on the Red List, with more than 40,000 species threatened with extinction: 41% of amphibians, 37% sharks and rays, 34% of conifers, 33% of reef building corals, 26% of mammals, and 13% of birds. The breakdown is sobering.

Why should we care? We care because we have co-evolved with the living world of animals and plants and fungi and corals and multitudes of microorganisms, many that have never been seen or defined or categorized or named. “The great majority of species of organisms—possibly in excess of 90%—remain unknown to science,” the venerated scientist E. O. Wilson wrote before his death in 2022. He also coined a word, biophilia, to mean “the inborn affinity human beings have for other forms of life, an affiliation evoked, according to circumstance, by pleasure, or a sense of security, or awe, or even fascination blended by revulsion.” We care because it is in our deepest nature to live and learn and evolve from the life that surrounds us.

We imitate animals through dance and song and stories. In ceremonies, their skins are donned; in fashion, we wear their prints and feathers; in art, we draw them, paint them, and sculpt them, making masks to honor them; and in every religious tradition animals from snakes to lions to locusts and doves we reference them, we fear them, we worship them and bow. They are our teachers, our mentors and guides capable of portending our future because they were here to meet us when we arrived. “Men are born human. What they must learn is to be animal,” says ecologist Paul Shepard. “If they learn otherwise it may kill them, and kill life on the planet.”

4

IF THE ENDANGERED SPECIES ACT itself has been protected for the past five decades by the passionate research of scientists and the savvy of committed lawyers with the flexed muscle of grassroots organizations, I believe what is being called forth in the twenty-first century is the strength of our collective will—fierce and direct. As David Lamfrom, Vice President of Regional Programs at the National Parks Conservation Association, says, “Our opening position now must be ‘No more.’” No more compromises on the survival of grizzly bears, wolves, and wolverines. No more “taking” (a euphemism for killing) of prairie dogs and development in the critical habitat of black-footed ferrets and burrowing owls. No more draining of precious wetlands where scores of threatened species are making their last stands. No more apathy on our part. No more wondering what we can do when the Endangered Species Act needs heart-fires of support when Congress will inevitably move again to threaten the Act’s beautiful, shimmering teeth of accountability in the name of justice for all.

“Right now, in the amazing moment that to us counts as the present, we are deciding, without quite meaning to, which evolutionary pathways will remain open and which will forever be closed,” writes Elizabeth Kolbert in The Sixth Extinction. “No other creature has ever managed this and it will, unfortunately, be our most enduring legacy.”

You, Dear Reader, hold in your hands A Wild Promise. Allen Crawford has created an illustrated celebration of the Endangered Species Act, vibrant and instructive by featuring eighty vulnerable species. He is a visionary artist who not only cares about the survival and sustaining grace of the “more than human world” but has chosen to put his gifts to use with the intention of inspiring us to care more deeply and act more consciously on behalf of these vulnerable creatures.

As you meet each species in this collection, a coalition of representatives from the Endangered Species list, let this become a moment of contemplation about their lives, where they live and how, in the context of six ecosystems: oceans, wetlands, grasslands, deserts, forests, and mountains. Other species are candidates nominated for consideration. Some of the creatures are critically endangered. Some are threatened. Some have been taken off the Endangered Species list like the the bald eagle, peregrine falcon, and brown pelican, as a result of a national ban on the pesticide

5

DDT issued by an order of the Environmental Protection Agency on June 14, 1972. Others are on the precipice of extinction like the North Atlantic right whale with only 400 individuals remaining due to centuries of overfishing, entanglement in fishing lines, and increased ship traffic that bisects calving areas.

Perhaps as you come to know their stories, you will be moved to seek out an endangered or threatened species that lives close to you, learn their natural history and give them not only your attention, but your devotion. Or maybe you know of a species in your state or a particular ecosystem that needs federal protection. You can support a specific species campaign addressed to the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service to nominate newly threatened plants and animals to be concerned for protection under the Endangered Species list. Advocates in the Northern Rockies are working to upgrade the status of the wolverine from a “species of concern” to “threatened.” The Endangered Species Act is an act of love that asks for our engagement, each in our own way with the gifts that are ours in the places we call home. Learn their names. Speak their names. Remember their names. Act.

As a child, I watched the men I loved in my family lift their high-powered rifles and shoot one prairie dog after another and another for fun, and then walk away. They called them “pop-guts.” On the way back to our camp, I stepped over their small blood-soaked, blown-apart bodies left in the matted grasses of their prairie dog town. And then, a single prairie dog raised her head out of a burrow and stood up and faced me. I froze in place, unable to avoid her gaze. She disappeared underground. On that day, I made a vow, short of standing in front of my father’s rifle, that I would be their ally. I have tried to keep that vow.

I graduated from high school in 1973, the same year the Endangered Species Act was signed into law. At that time only 3,300 Utah prairie dogs remained in thirty-seven isolated colonies in the state of Utah. Due to political pressure from ranchers and developers, they were not listed on the original Endangered Species list. Prairie dogs were seen as vermin.

In 1977, I lobbied the Utah legislature as a graduate student in education from the University of Utah. I had created a Utah prairie dog curriculum for the Salt Lake City school district. At the State Capitol, I was met with incredulity and disdain by representatives who insisted on calling prairie dogs “varmints.” The Speaker of the House

6

handed me a recipe for “Prairie Dog Stew.” Finally, in 1984, the Utah prairie dog was added to the Fish & Wildlife’s Endangered Species list and remains on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.

In 2000, in a special millennial issue of The New York Times Magazine, the Utah prairie dog was featured as one of ten species most likely to become extinct by the next millennium. Their fate was to become a ghost species. I wrote a book on prairie dogs. Every month I sent a picture of prairie dogs in different poses (one with a helmet and bazooka) to friends at The Utah Nature Conservancy, a playful nudge for protection. Did any of these gestures make a difference? It made a difference to me. This was my wild promise that became a vow I made to the lone Utah prairie dog who survived my family’s massacre.

What is the difference between a promise and a vow? A promise is “a specific declaration or assurance that one will do a particular thing or that a particular thing will happen.” A vow is “a solemn promise”—a deepening gesture that one makes with one’s whole being. Both are nouns. But what if we see them as verbs, as actions that grow out of a commitment?

A promise becomes giving one’s word—“assuring someone that one will definitely do, give, or arrange something; undertake or declare that something will happen.” A vow is an open-ended commitment over time that moves into the realm of a sacred obligation—“dedicated to someone or something, especially a deity.” If one believes, as I do, that the Divine resides in all living things, then there are many gods among us, in a myriad of shapes and sizes and forms.

Perhaps you have often felt yourself watched. Perhaps you were right.

—Helen Mort, The Illustrated Woman

WHETHER IT IS A WOLF LODGED DEEP inside our psyches or a mite invisible to our eyes, each species encompasses a life honed to perfection over millions of generations. Our wild promise within the Endangered Species Act, to protect and

7

keep safe threatened and critically endangered species from extinction, can become a vow of action. What I have learned from spending time in Utah prairie dog towns is that community matters. These communal animals watch out for each other. Each member of a colony has a carefully communicated role to play.

Could they be watching out for us, as well? By caring for their own kind, prairie dogs simultaneously create an environment where other species can thrive. They are a keystone species that other species rely on for their survival. Where prairie dogs dwell other species dwell, also—including black widow spiders, pronghorn antelope, burrowing owls, badgers, meadowlarks, and rattlesnakes. Each species fulfills their ecological niche. Diversity equals stability. Prairie dogs continue to teach me, we are nothing without community in all its magnificent and infinite variety.

We, too, are threatened. Endangered species are showing us now that we are not immune from the perils of climate collapse. The issues affecting endangered species, such as habitat destruction from extreme weather, to drought, to fires, are inextricably linked. My friend Becky Duet and her family, who are Cajun, have lived in the bayous of Louisiana for generations. They lost their home in the summer of 2021 to Hurricane Ida. The eye of the hurricane split in two, something they had never seen. There was no momentary calm—what came instead were 190 miles per hour winds that threatened their lives and blew apart their town of Galliano. Her husband Earl, a renowned shrimper in the area, lost his way a decade ago as the grasslands and waterways he once knew by heart disappeared to erosion. Now the maze of shrimping in the bayous has been lost to open waters. Louisiana loses one football field of soil every hour. The Duet family now belongs to tens of thousands of climate refugees who see what is happening and are sounding the alarm, but not enough of us are listening, watching, and bearing witness to a world transformed.

Our ignorance and arrogance are threatening life on the planet as we continue to live as though nothing has changed, as though our reliance on fossil fuels has no consequences, as if holding fast to our beliefs that we have the right to drill for more and more oil at greater and greater cost to the Earth and its inhabitants will make it right.

This is not a homily, this is a fact: Our relentless drive to protect our American lifestyle while we continue devouring the sacred sites of endangered species for our

8

own short-lived additions is our pathology. This will be our undoing. Respect and restraint will be our healing. Our unconscious and conscious acts of killing must be transformed into intentional acts of reverential vigilance. Animals are leaving us. Plants and fungi are offering us their medicines so that we might see more clearly with greater understanding, our place in the wholeness of things. Native bees continue to pollinate wildflowers and grace us with honey even as their populations plummet. On hands and knees, we would do well to take the humble stance of an animal and remember who we are, where we belong, and what our responsibilities to those with whom we share this planet must become and why.

I often return to these lines from the prose poem “Dead Seal near McClure’s Beach” written by Robert Bly—the poem that made me care. His words about a seal dying from spilled oil held a mirror up to my own complicity in the suffering of animals:

. . . goodbye brother, die in the sound of waves, forgive us if we have killed you, long live your race, your inner-tube race, so uncomfortable on land, so comfortable in the ocean. Be comfortable in death then, when the sand will be out of your nostrils , and you can swim in long loops through the pure death, ducking under as assassinations break above you. You don’t want to be touched by me. I climb the cliff and go home the other way.

WE CAN WRITE A DIFFERENT ENDING to the stories of critically endangered species and all the miraculous creatures large and small whose populations are in decline. Their lives are in our hands. A new ending is possible once we begin to love and live differently.

9

Terry Tempest Williams

GRIZZLY BEAR

Ursus arctos horribilis

Found in Alaska, Washington, Montana, Idaho, and Wyoming.

Population in Alaska: 30,000.

An estimated 1,913 grizzlies remain in the lower 48 states.

Listed as threatened in 1975.

12

BIG SANDY CRAYFISH

Cambarus callainus

Once found throughout the upper Big Sandy River watershed {10 counties in Kentucky, West Virginia, and Virginia}. Now only found in 4 isolated populations.

Range has been reduced by more than 60%.

Threats include sediment from mining, habitat degradation from timbering, and the impacts of offroad vehicles.

Listed as threatened in 2016.

(following page)

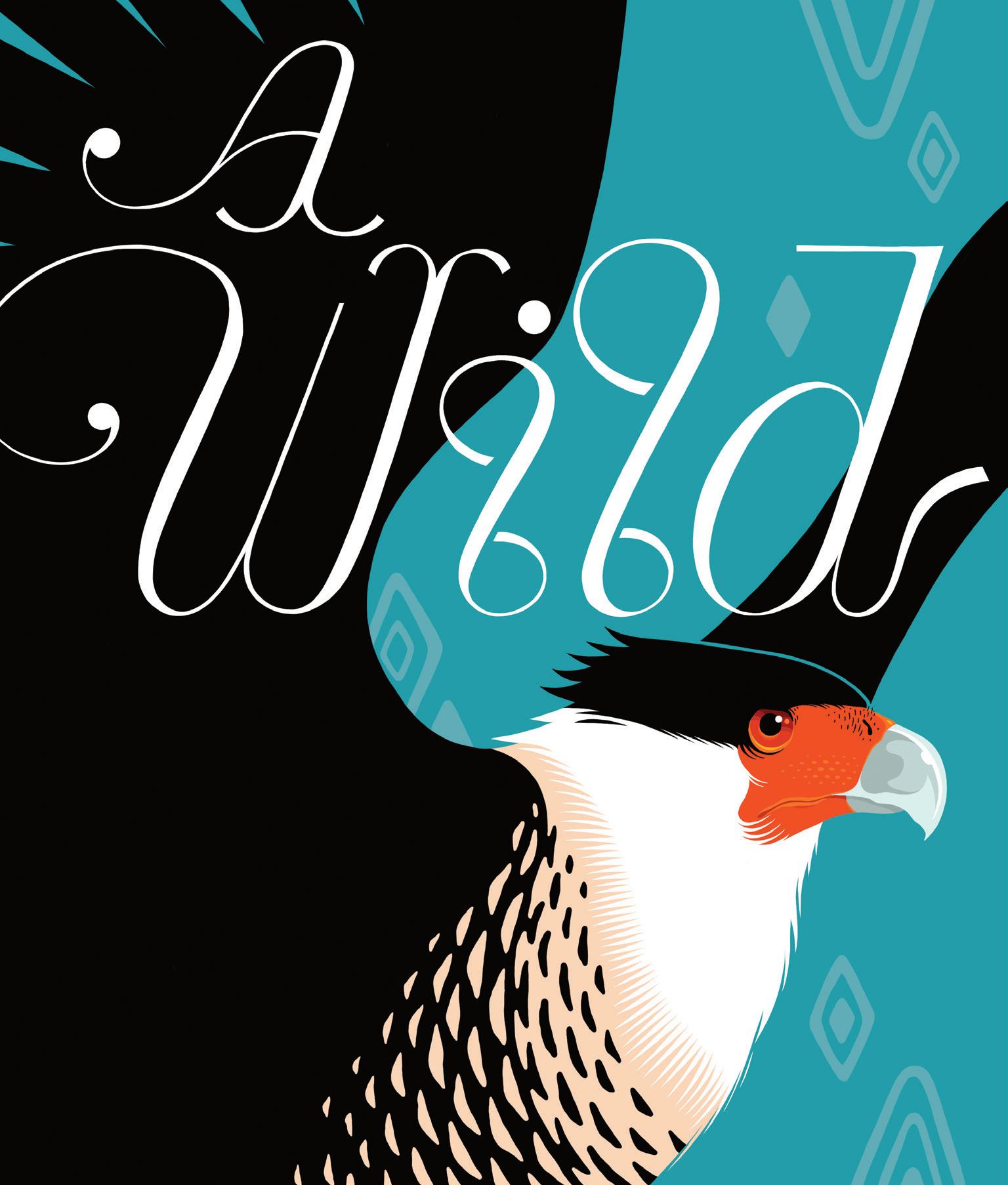

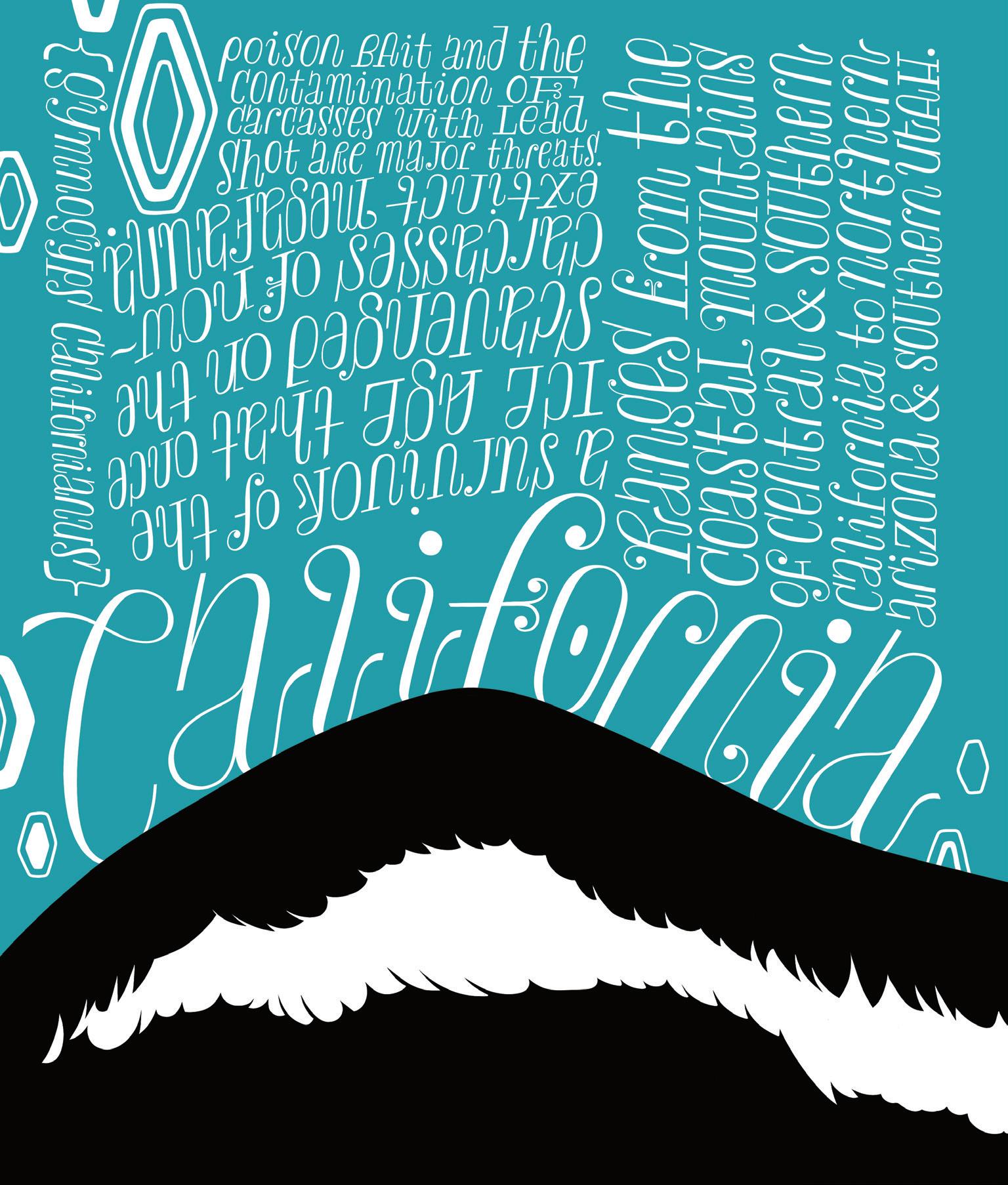

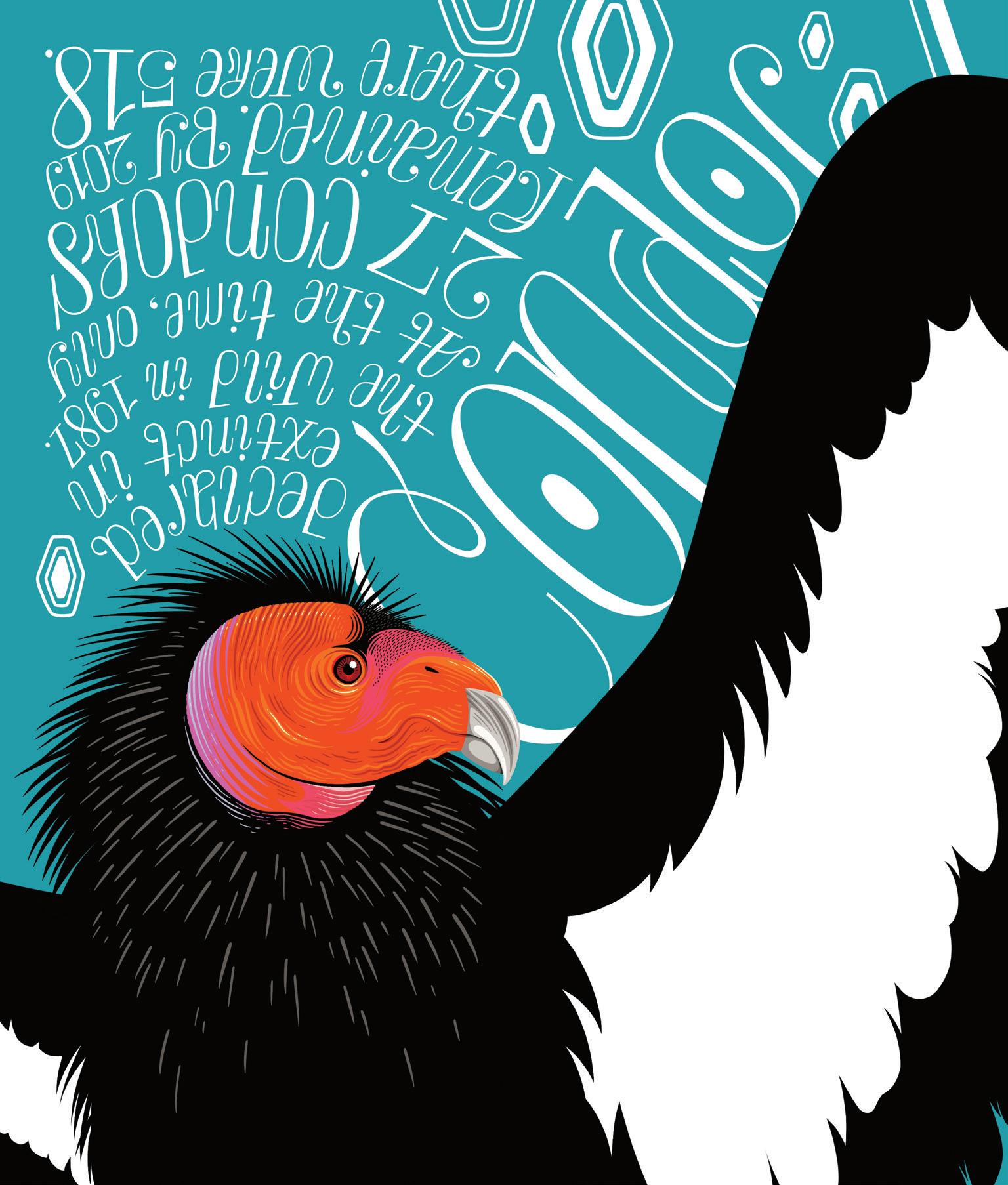

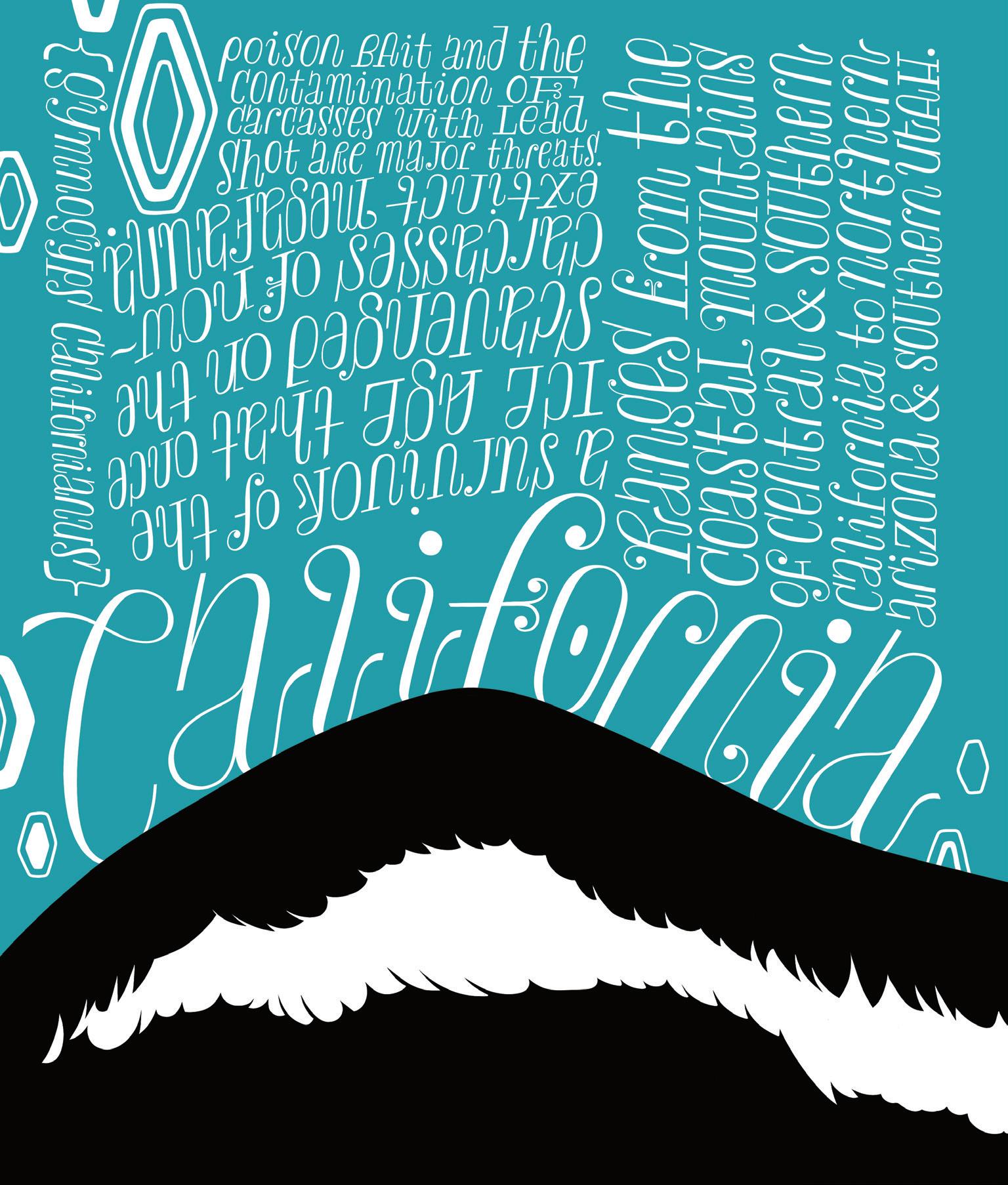

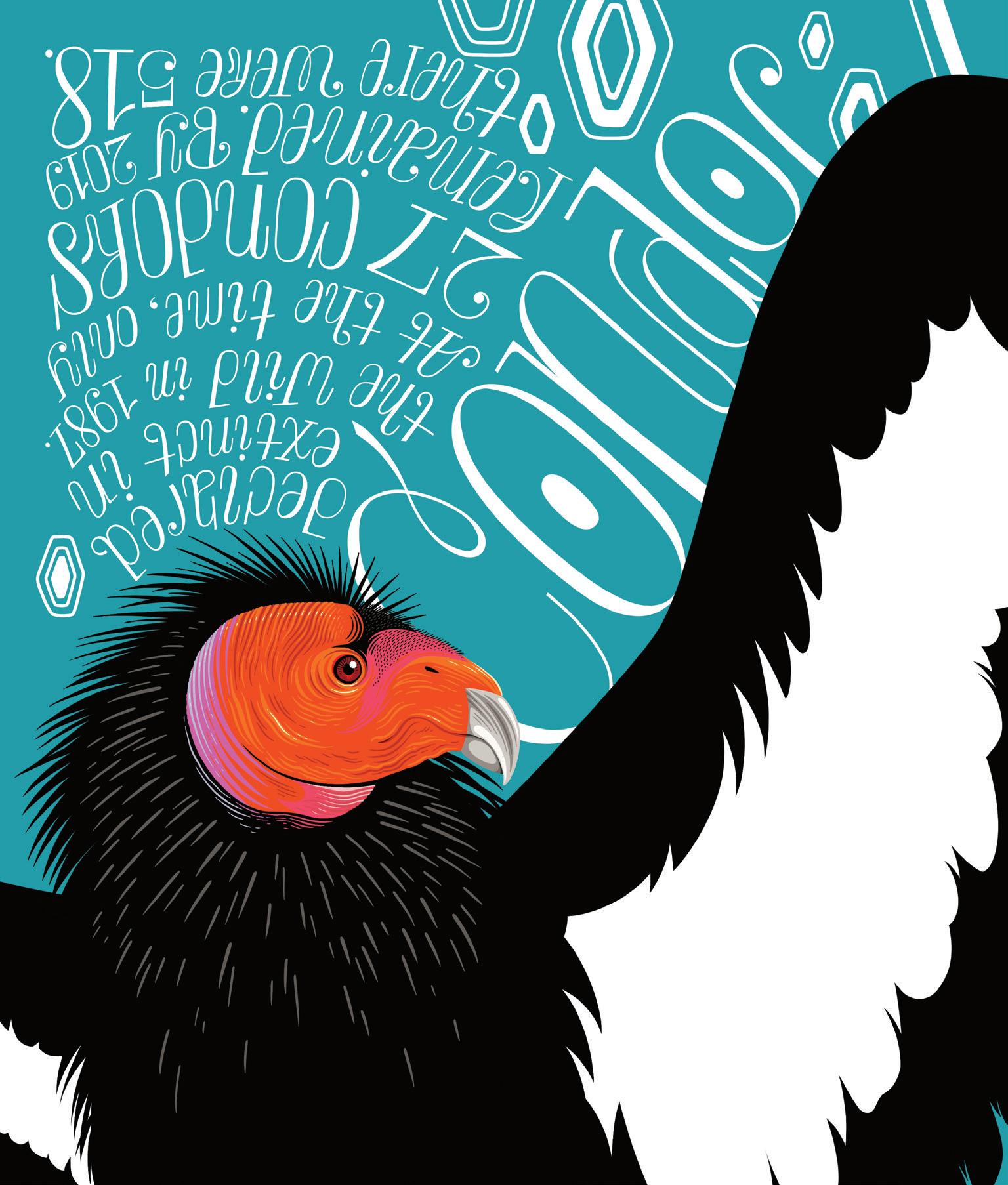

CALIFORNIA CONDOR

Gymnogyps californianus

Ranges from the coastal mountains of central and southern California to northern Arizona and southern Utah.

A survivor of the last Ice Age, scavenged on the carcasses of now-extinct megafauna.

Poison bait and the contamination of carcasses with lead shot are major threats.

Declared extinct in the wild in 1987. At the time, only 27 condors remained.

By 2019, there were 518.

14

WESTERN BUMBLEBEE

Bombus occidentalis

Population has dropped 40% over the past decade.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is considering it for listing under the Endangered Species Act.

DWARF BEAR-POPPY

Arctomecon humilis

Only eight known populations, all of which are located in Washington County, Utah.

Listed as endangered in 1979.

18

SPRUCE-FIR MOSS SPIDER

Microhexura montivaga

This species lives only in cool damp moss in dwindling spruce and fir forest habitats on a handful of mountains in southwestern Virginia, eastern Tennessee, and western North Carolina.

Fir trees are dying from invasive insect infestations, which opens canopy and kills moss.

Listed as endangered in 1995.

20

OZARK HELLBENDER

Cryptobranchus alleganiensis bishopi

Found in southern Missouri and northeastern Arkansas.

75% decline over the past thirty years.

Fewer than 600 left in the wild.

Listed as endangered in 2011.

22

(previous page)

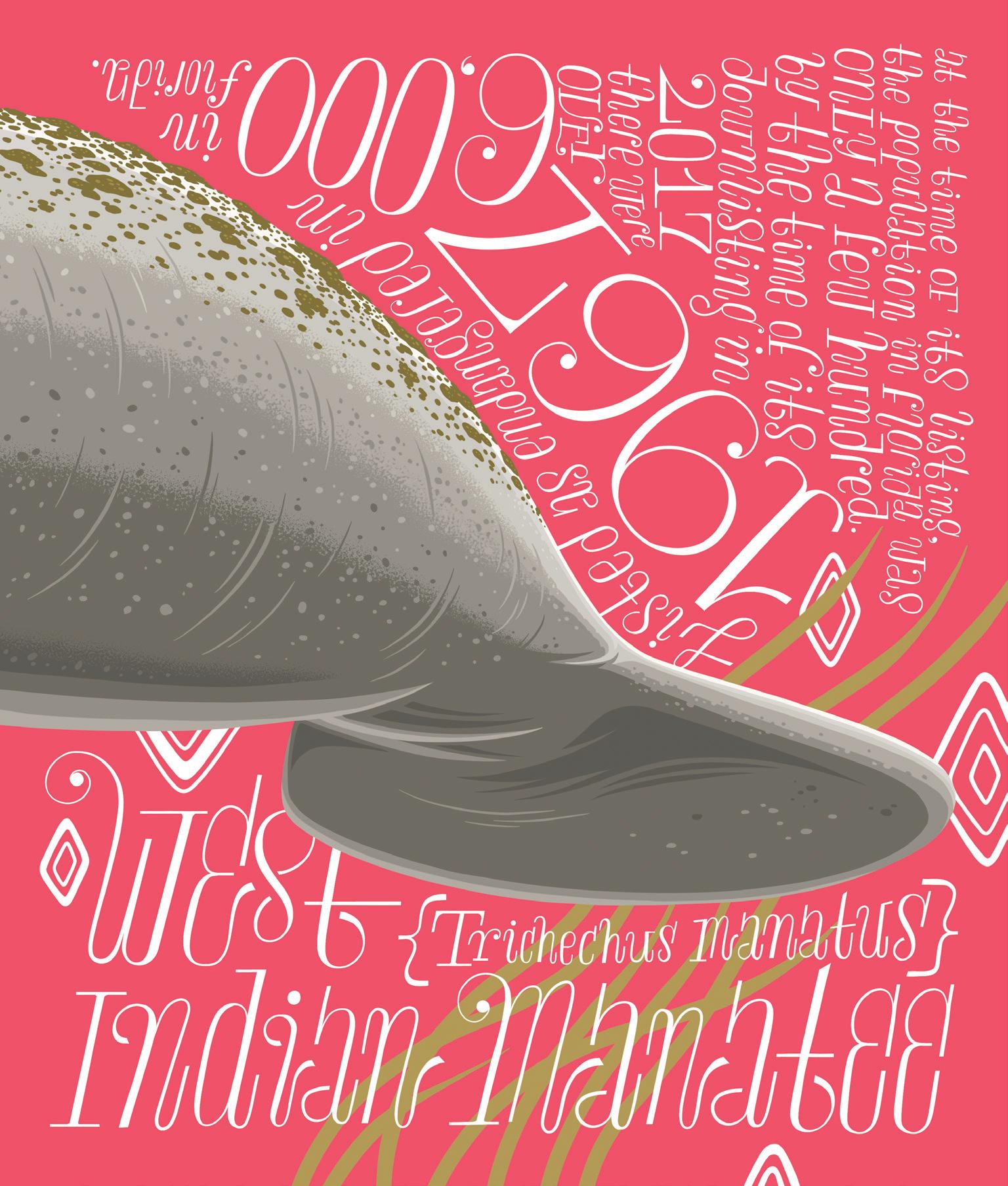

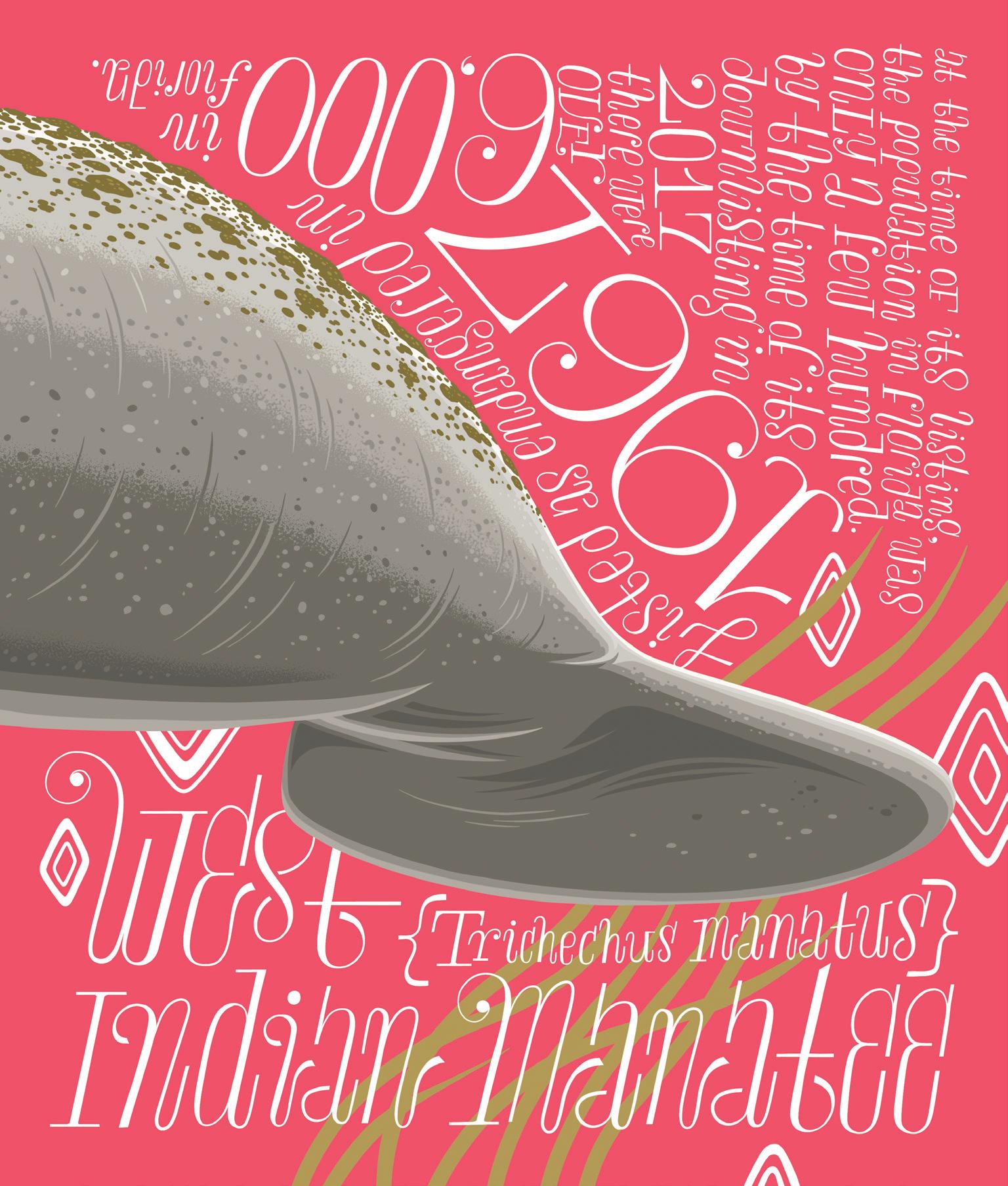

WEST INDIAN MANATEE

Trichechus manatus

Found mainly along the coast of Florida, but can range north to the mid-Atlantic Seaboard and south to the Gulf and the Caribbean.

Collisions with watercraft are among the main threats to this species.

At the time of its listing, the population in Florida was only a few hundred. By the time of its downlisting in 2017, there were over 6,000 in Florida. Listed as endangered in 1967.

Downlisted to threatened in 2017.

STELLER SEA LION

Eumetopias jubatus

Found in the Bering Sea and Alaska to British Columbia and central California.

Eastern population listed as threatened in 1997, delisted in 2014.

Western population listed as endangered in 1997 { Aleutian Islands}.

28

(previous page)

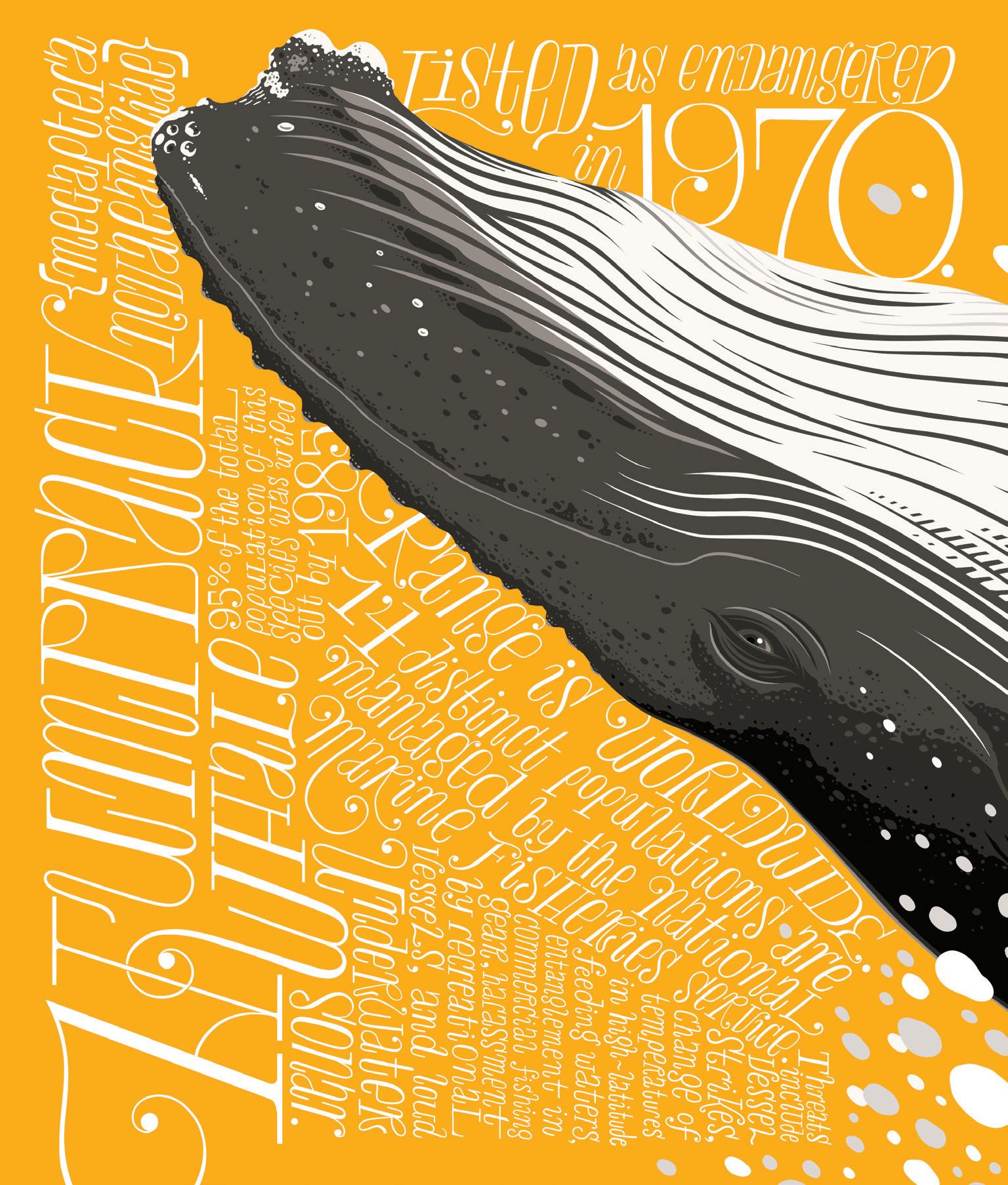

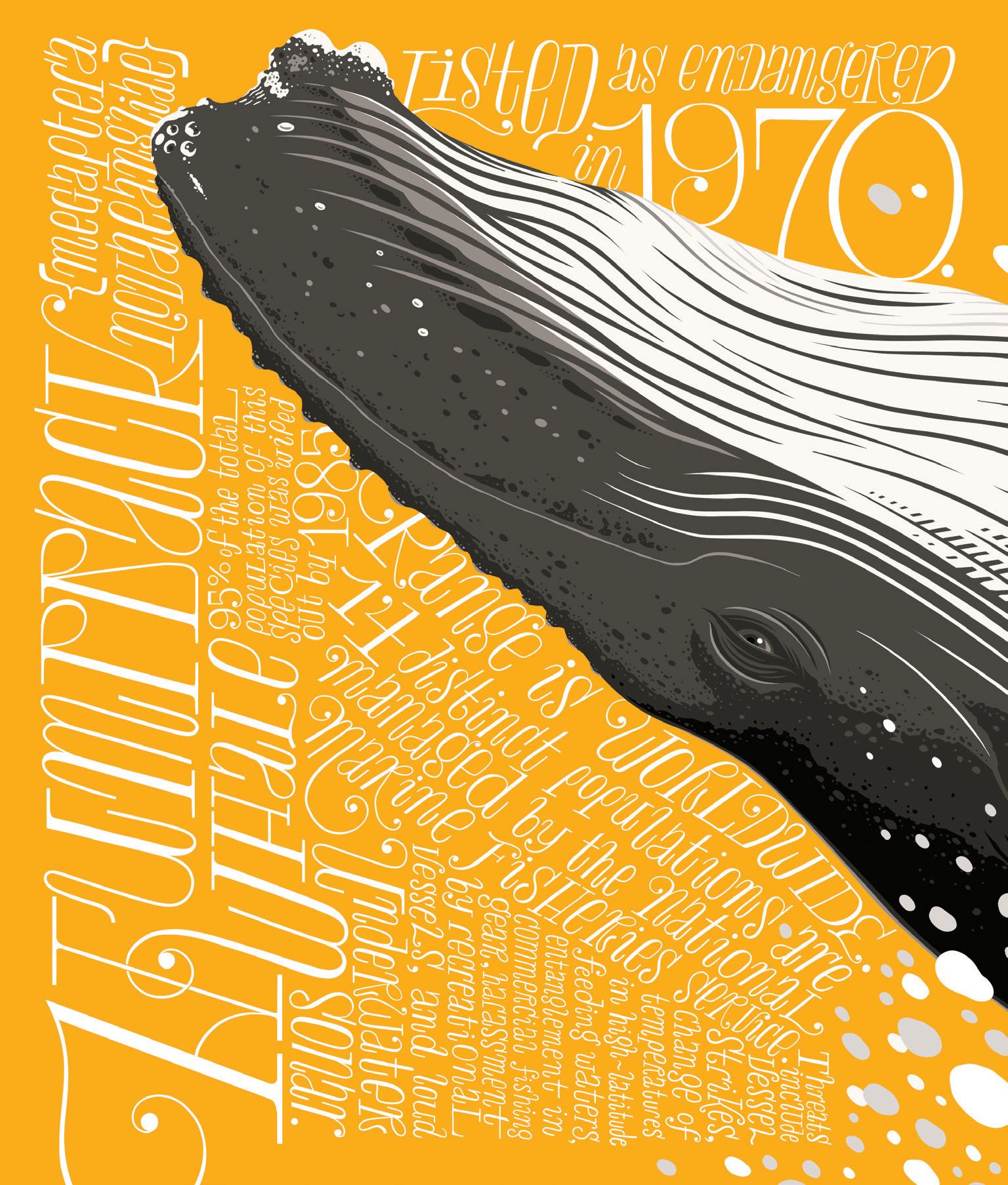

HUMPBACK WHALE

Megaptera novaeangliae

Range is worldwide. 14 distinct populations are managed by the National Marine Fisheries Service.

Threats include vessel strikes, change of temperatures in high-latitude feeding waters, entanglement in commercial fishing gear, harassment by recreational vessels, and loud underwater sonar.

95% of the total population of this species was wiped out by 1985.

Listed as endangered in 1970.

As of 2016, 9 populations are delisted due to recovery, 4 populations remain endangered, and 1 remains threatened.

BROWN PELICAN

Pelecanus occidentalis

Lives on the Atlantic, Pacific, and Gulf coasts. Found as far north as Canada during the non-breeding season.

Estimated global population: 650,000.

Listed as endangered in 1970.

Delisted in 2009.

32

(previous page)

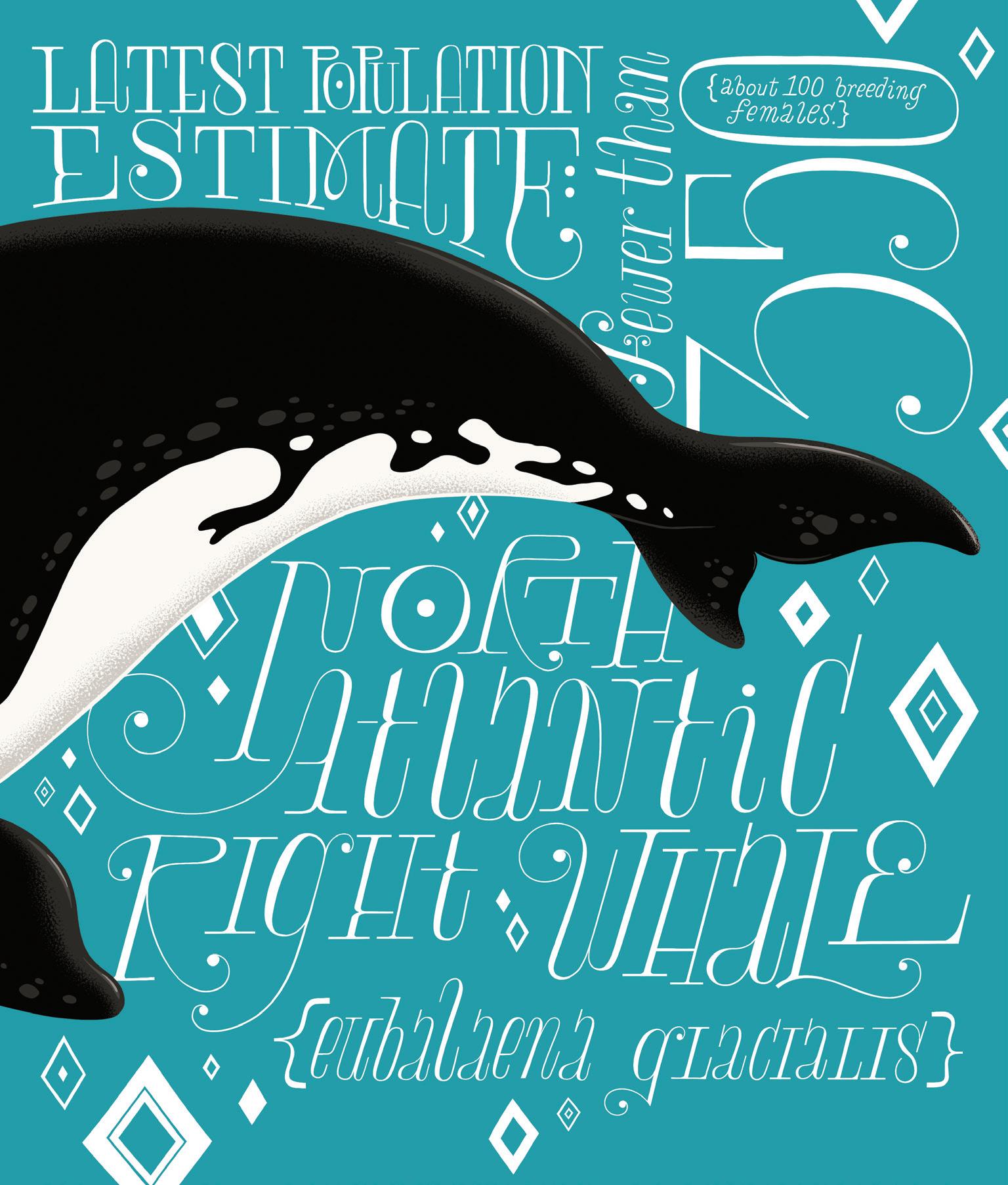

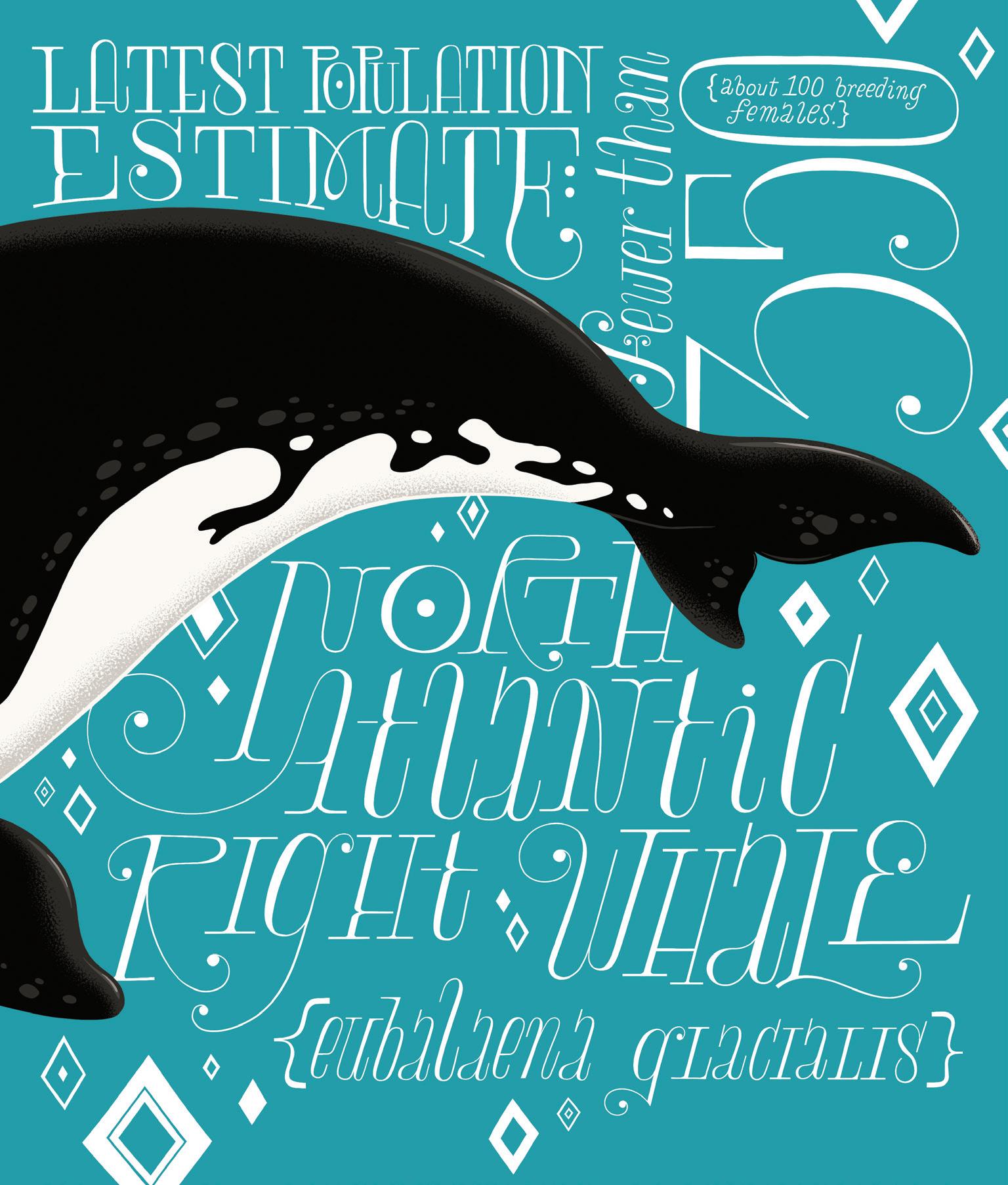

NORTH ATLANTIC RIGHT WHALE

Eubalaena glacialis

Feeds and breeds in the coastal waters of eastern North America.

Vessel strikes, fishing gear entanglements, and changes in the location and availability of prey due to warming ocean waters are the greatest threats to the survival of this species.

Latest population estimate: fewer than 350 {about 100 breeding females}.

Listed as endangered in 1970.

NORTHERN SEA OTTER

Enhydra lutris kenyoni

Found along coastal Alaska and southward along the North Pacific US coast.

Worldwide population in 2007: 107,000.

Southwest Alaska population listed as threatened in 2005.

36

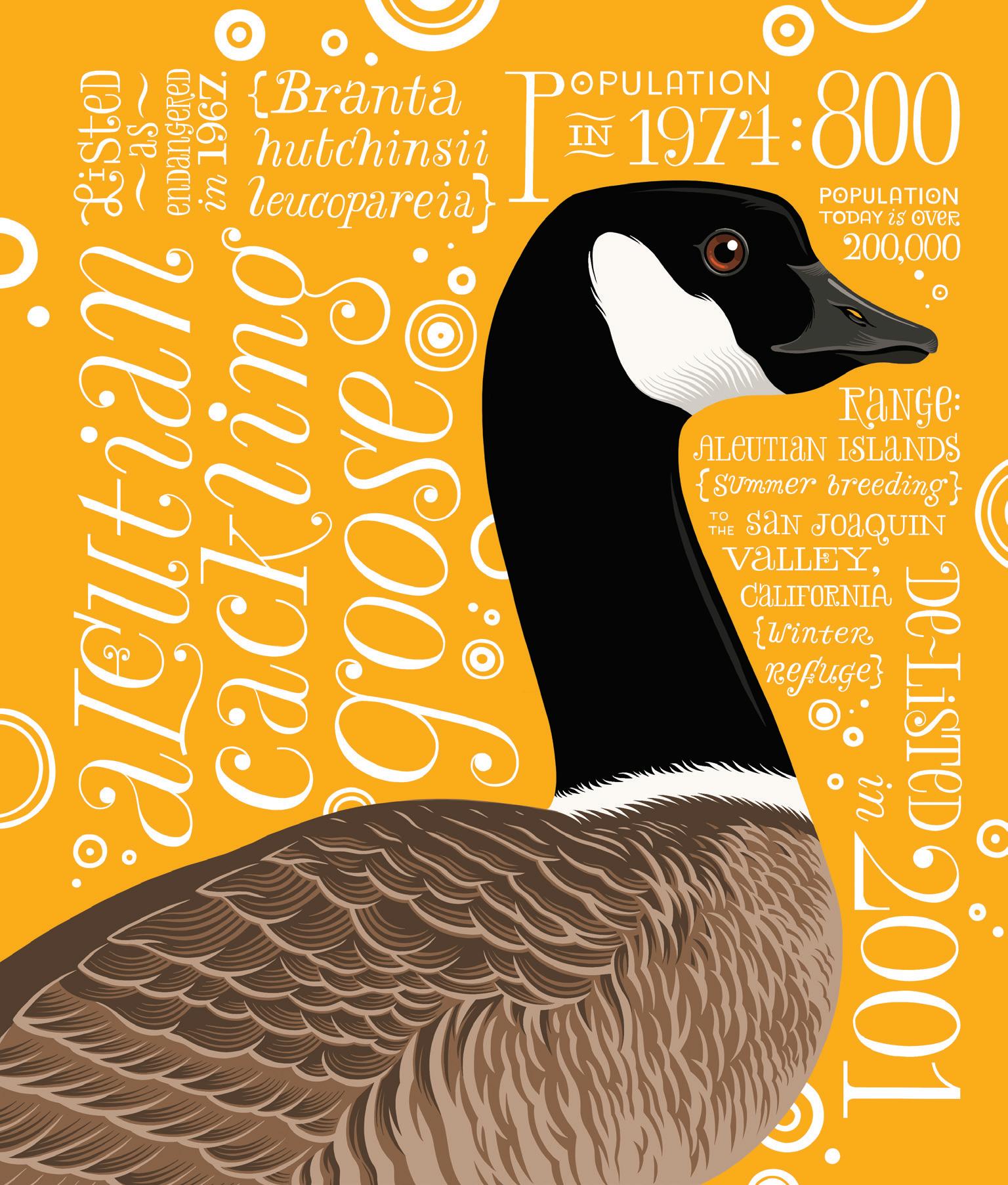

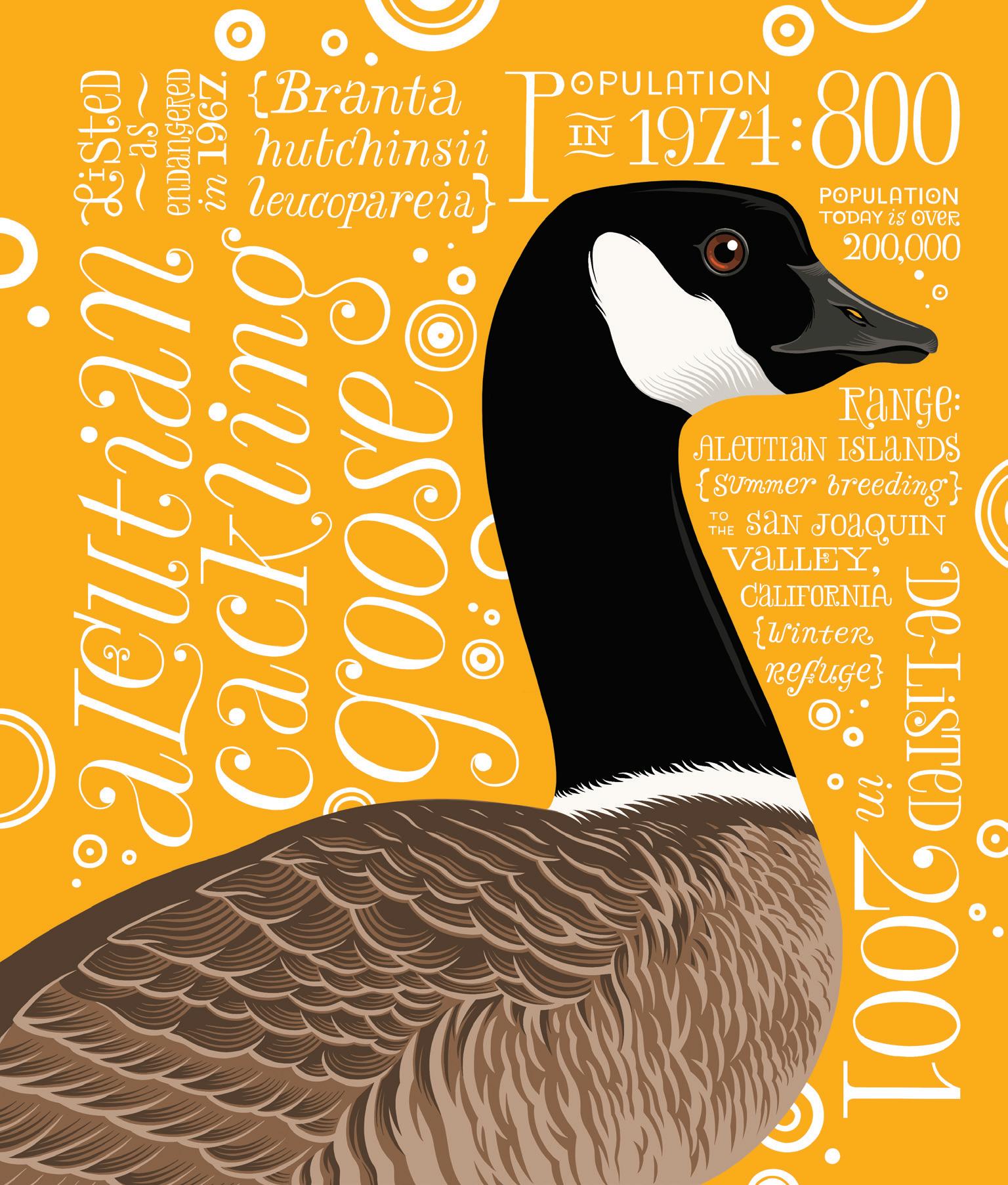

ALEUTIAN CACKLING GOOSE

Branta hutchinsii leucopareia

Range: Aleutian Islands {summer breeding} to the San Joaquin Valley, California {winter refuge}.

Population in 1974: 800.

Population today: over 200,000.

Listed as endangered in 1967.

Delisted in 2001.

38

MONITO GECKO

Sphaerodactylus micropithecus

Found only on Monito Island off the west coast of Puerto Rico.

Population decimated by rats.

Current population: 5,000–11,000.

Listed as endangered in 1982.

Delisted in 2019.

40

(previous page)

GREEN SEA TURTLE

Chelonia mydas

Found in the waters along the Atlantic, Pacific, and Gulf coasts of the US.

The largest breeding areas in the US are found in Hawai'i and Florida.

The largest populations worldwide are found in Australia’s Great Barrier Reef and the Caribbean Sea.

It is estimated that only 1% of hatchlings survive to full sexual maturity.

Human activity like boat traffic, commercial fishing gear, shoreline habitat destruction, plastics, chemical pollution, and poaching are major causes of population decline.

First listed under the Endangered Species Act in 1978.

11 regional populations monitored worldwide as of 2016: 8 populations are listed as threatened, 3 are listed as endangered.

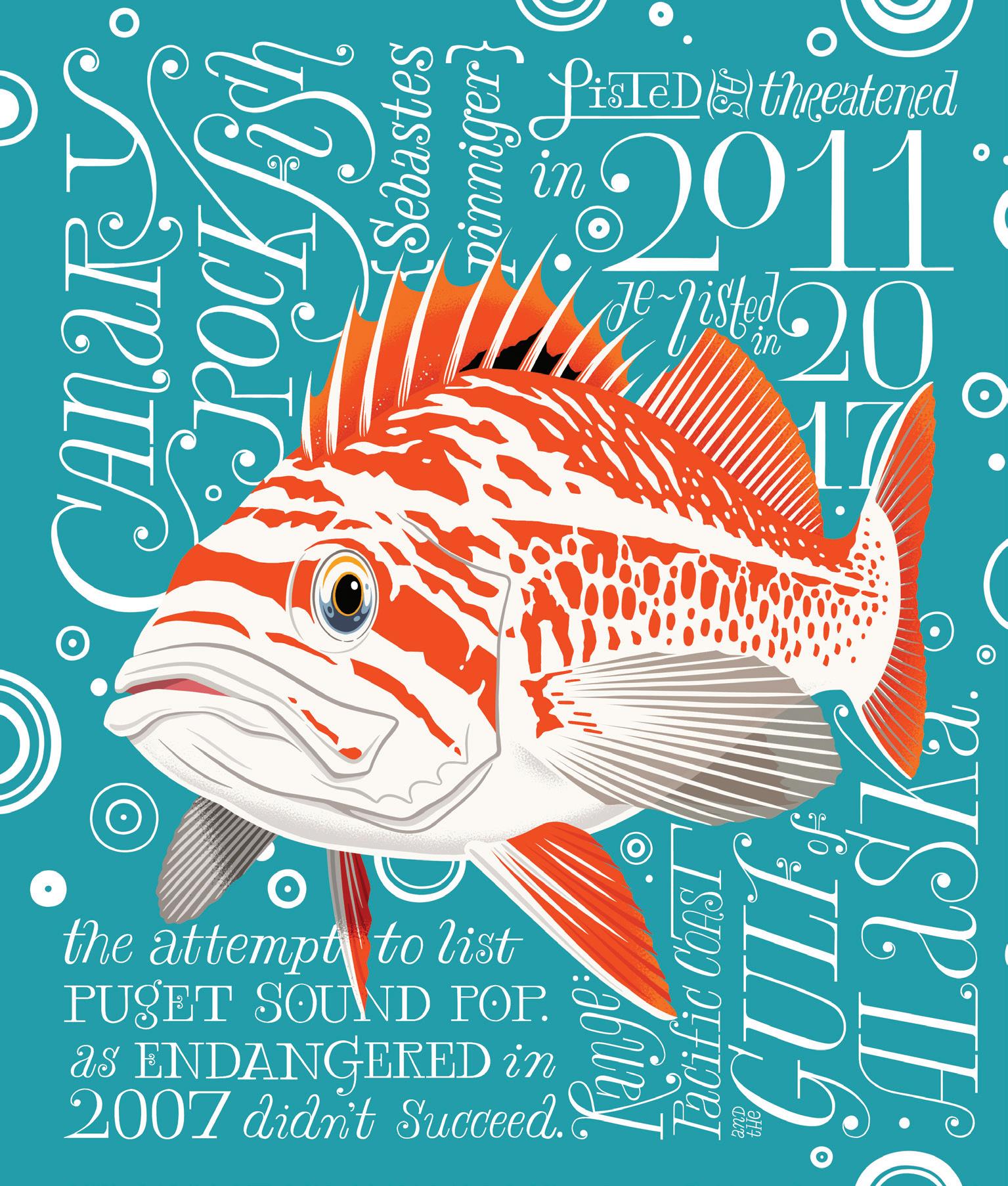

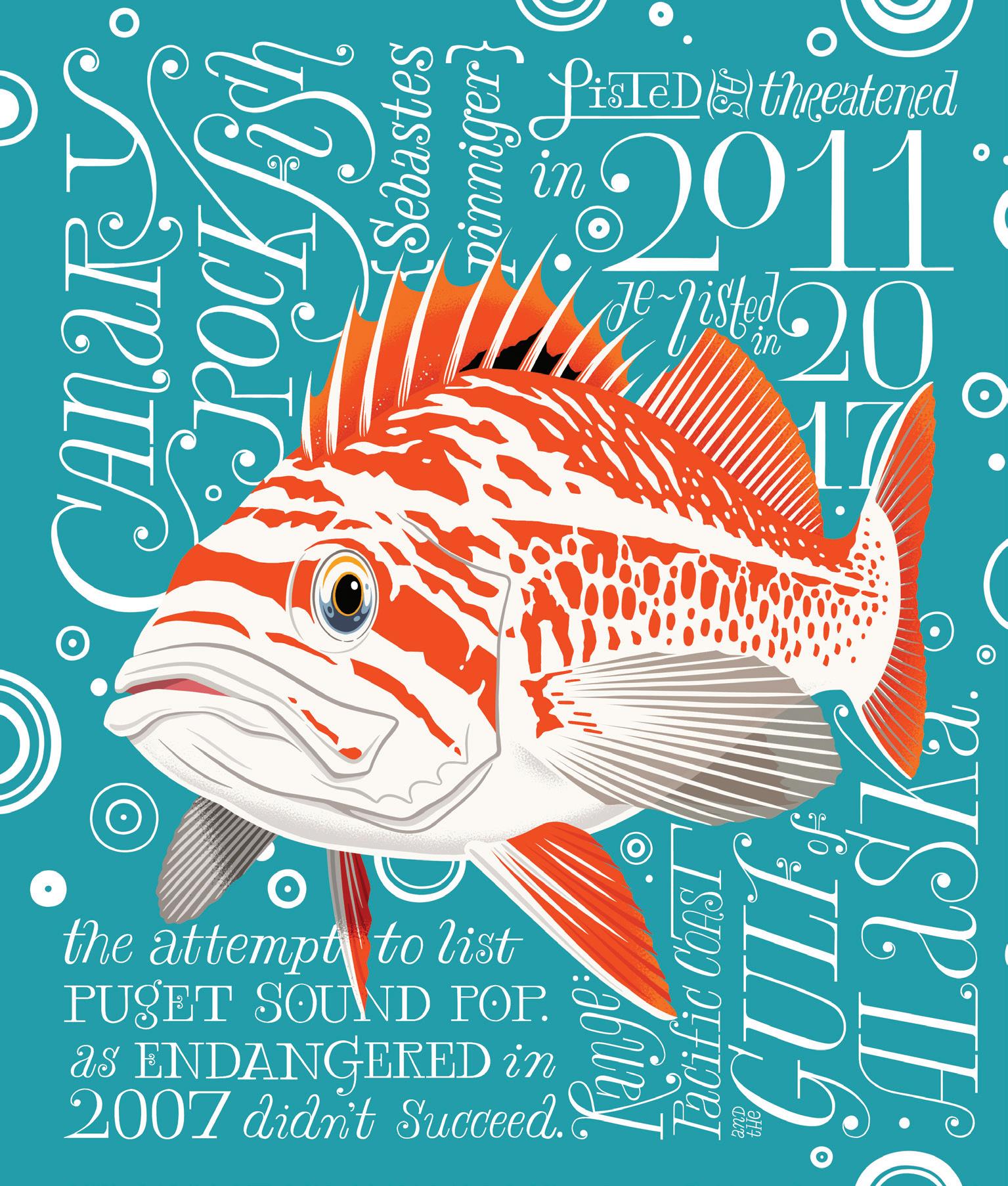

CANARY ROCKFISH

Sebastes pinniger

Found in the waters along the Pacific Coast and Gulf of Alaska.

The attempt to list Puget Sound population as endangered in 2007 didn’t succeed. Listed as threatened in 2011.

Delisted in 2017.

44

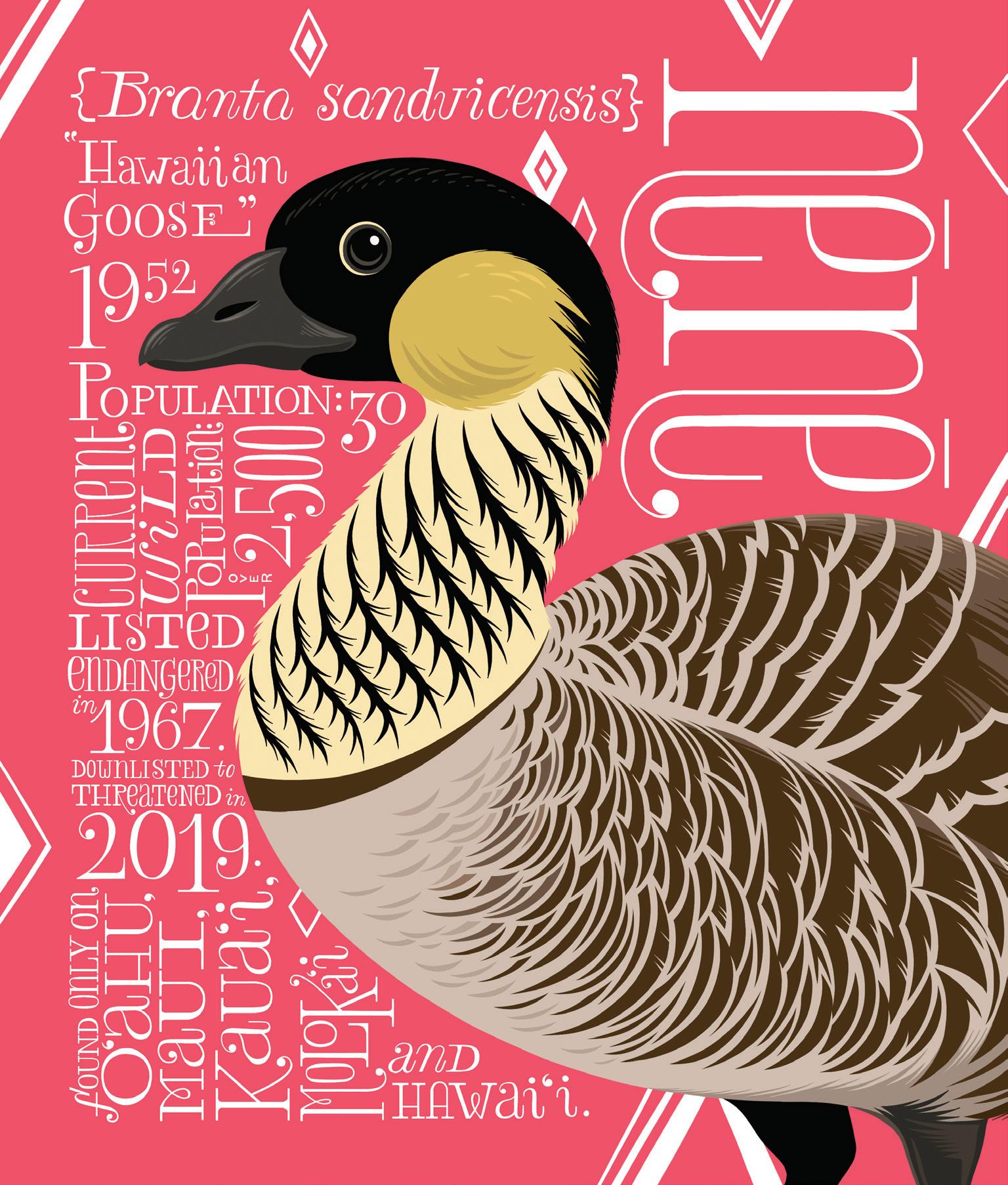

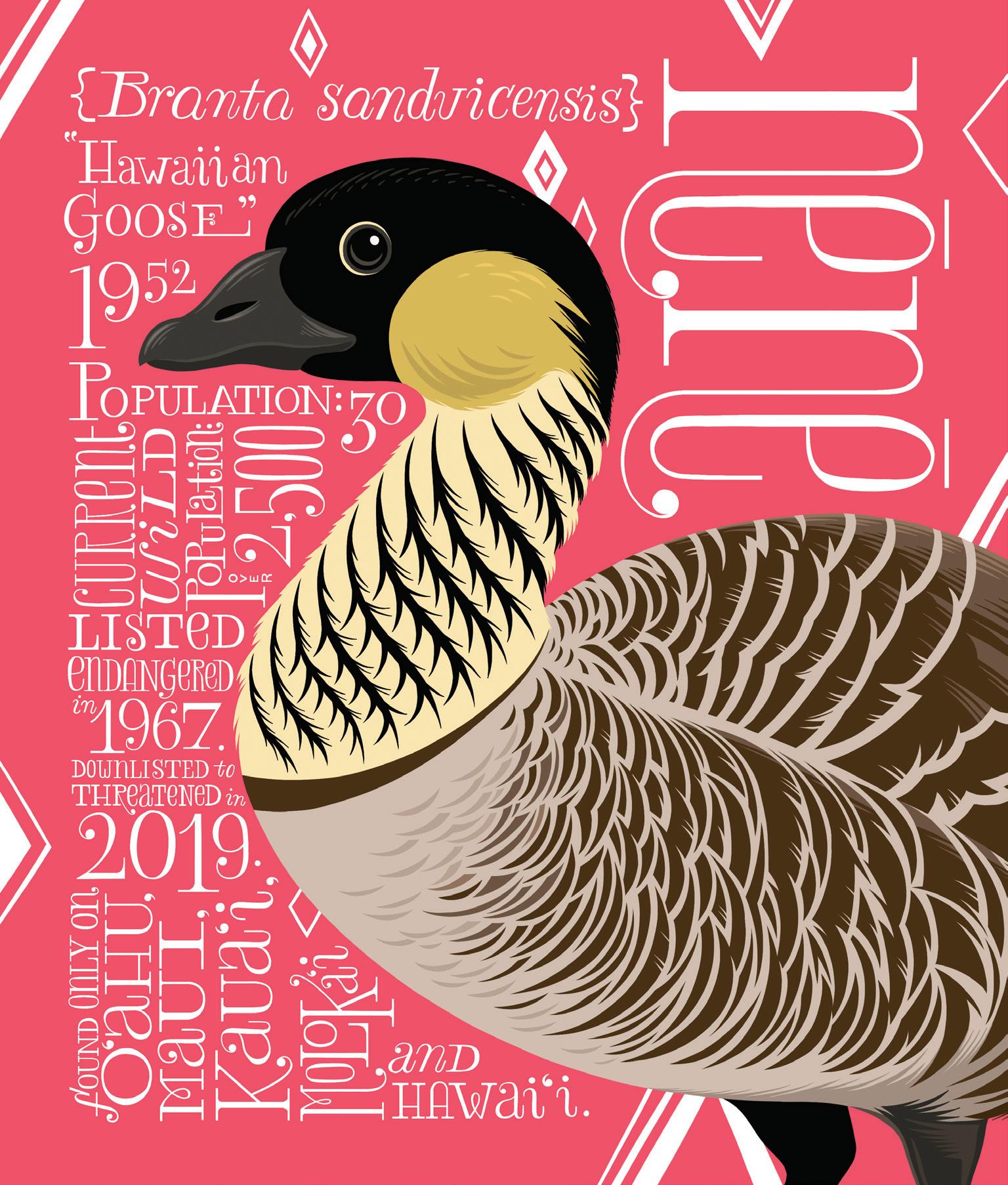

N Ē N Ē “HAWAIIAN GOOSE” Branta sandvicensis

Found only on O'ahu, Maui, Kaua'i, Moloka'i, and Hawai'i.

Population in 1952: 30.

Current wild population: over 2,500.

Listed as endangered in 1967.

Downlisted to threatened in 2019.

46

BELUGA WHALE COOK INLET POPULATION

Delphinapterus leucas

Found in Cook Inlet, Alaska.

Population in 1979: 1,300.

Population in 2018: 279.

Listed as endangered in 2008.

48

PIPING PLOVER

Charadrius melodus

Found on sandy beaches and lakeshores in the Great Plains, Great Lakes, and the Atlantic Coast.

Estimated population in 2022: 8,000.

Great Lakes population listed as endangered in 1986. Other populations listed as threatened in the same year.

50

SCALLOPED HAMMERHEAD SHARK

Sphyrna lewini

Found in temperate to tropical waters between 46◦ north and 30◦ south.

Overfishing is the main cause of decline. Numbers in the Atlantic have decreased by 95% over the past 30 years.

Central and Southwest Atlantic distinct population segment listed as threatened in 2014.

Indo-West Pacific distinct population segment listed as threatened in 2014.

Eastern Atlantic distinct population segment listed as endangered in 2014.

Eastern Pacific distinct population segment listed as endangered in 2014.

52

ATLANTIC SALMON

Salmo salar

Once native to almost every coastal river north of the Hudson River.

The only remaining population in the US lives in the Gulf of Maine.

Dams, pollution, and overfishing have reduced the wild population to less than 1,000 adults.

Gulf of Maine population listed as endangered in 2009.

(following page)

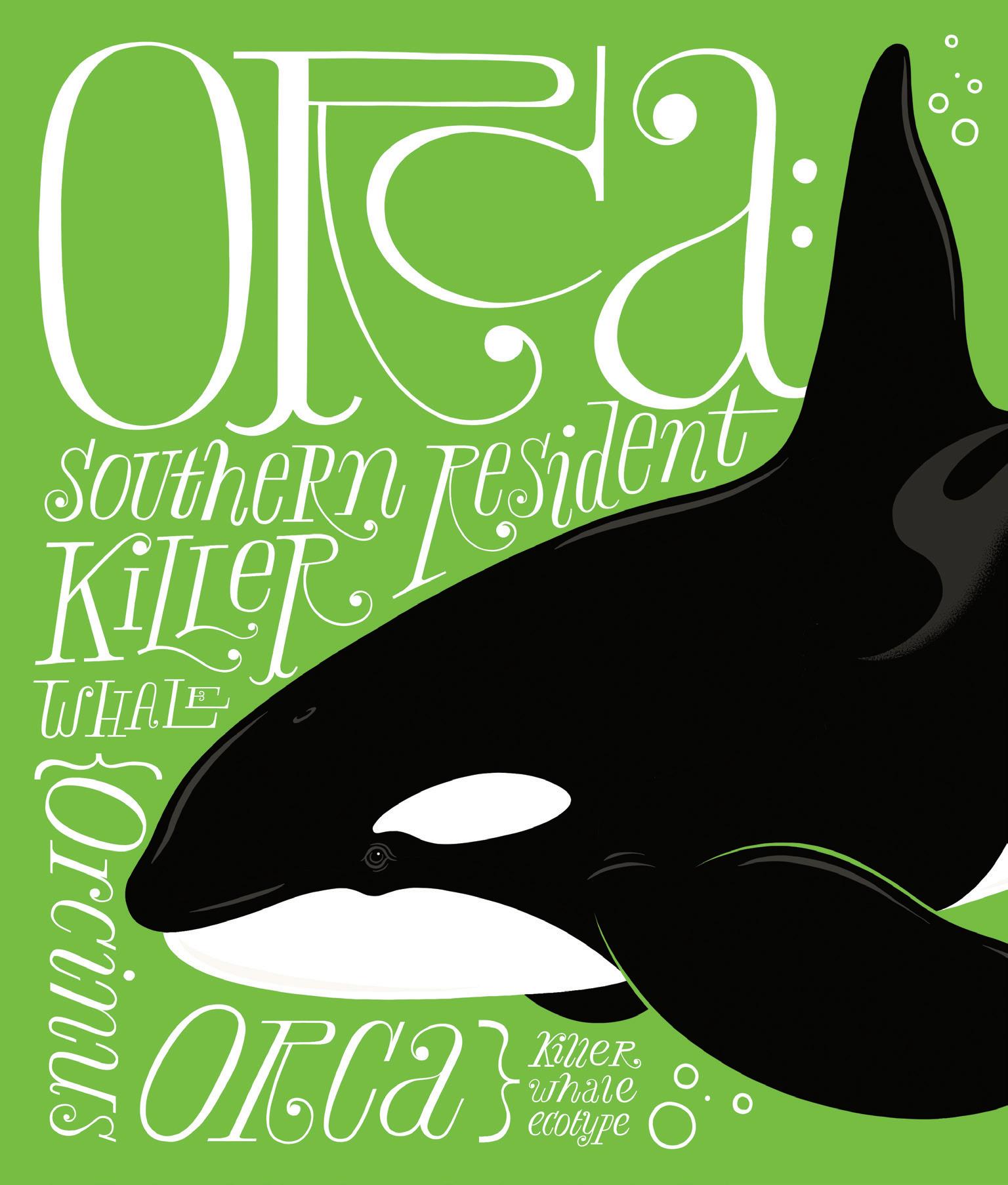

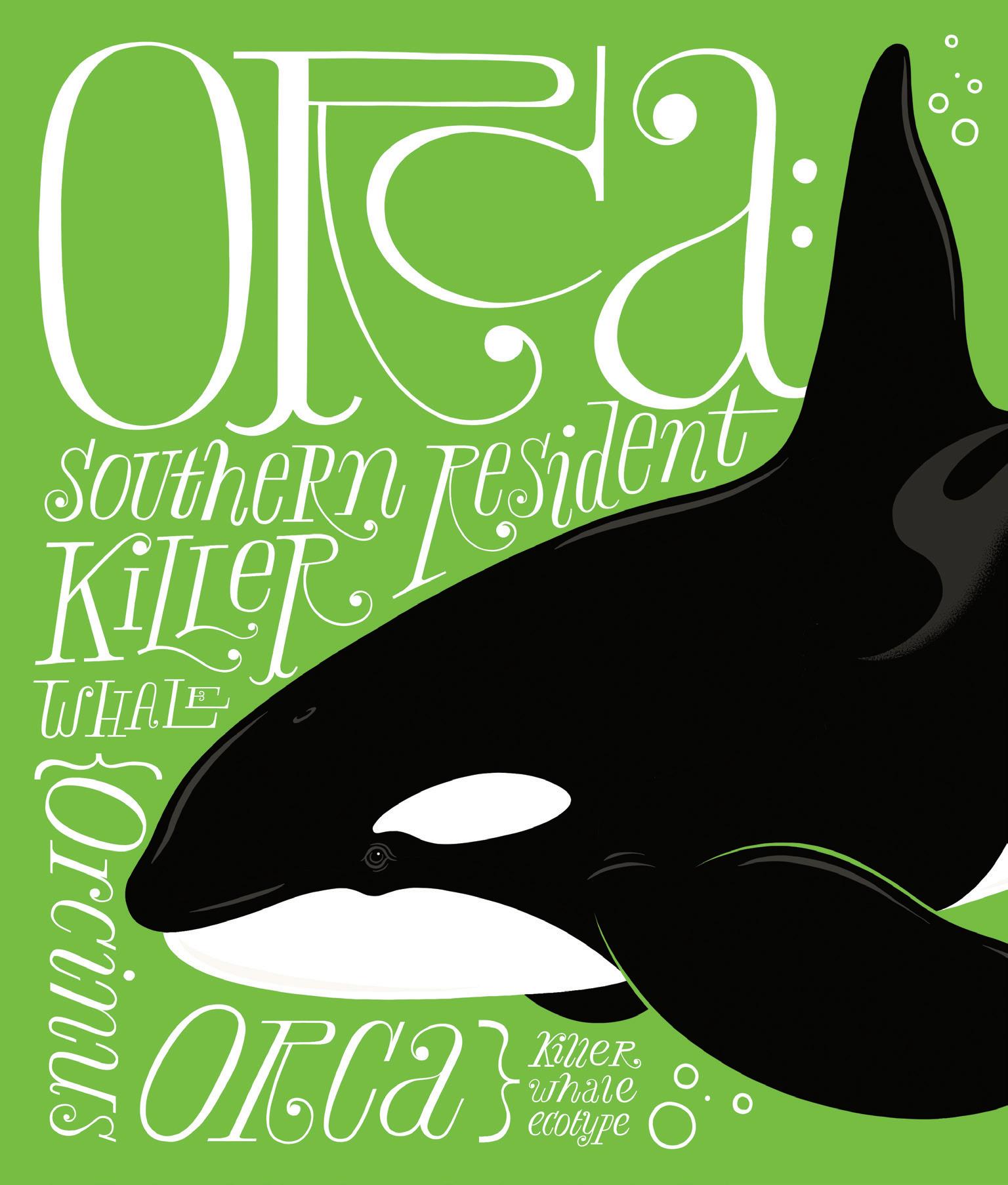

ORCA

SOUTHERN RESIDENT KILLER WHALE KILLER WHALE ECOTYPE

Orcinus orca

Found along the coast of British Columbia, Washington, and Oregon.

Chinook salmon is the main prey species of this ecotype.

Population in 1974: 71.

Population in 1995: 98.

Population in 2020: 72.

Southern Residents listed as endangered in 2005.

54

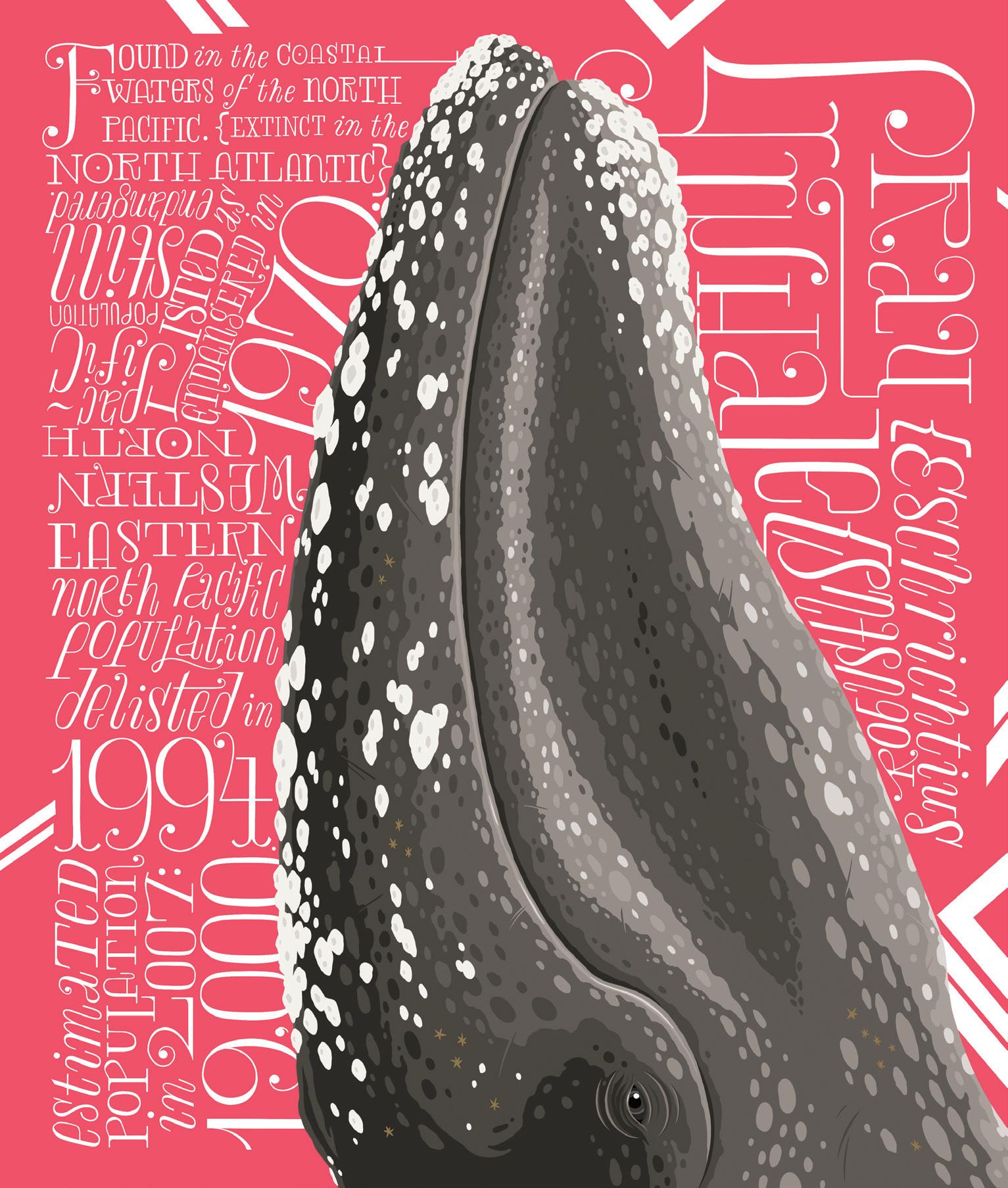

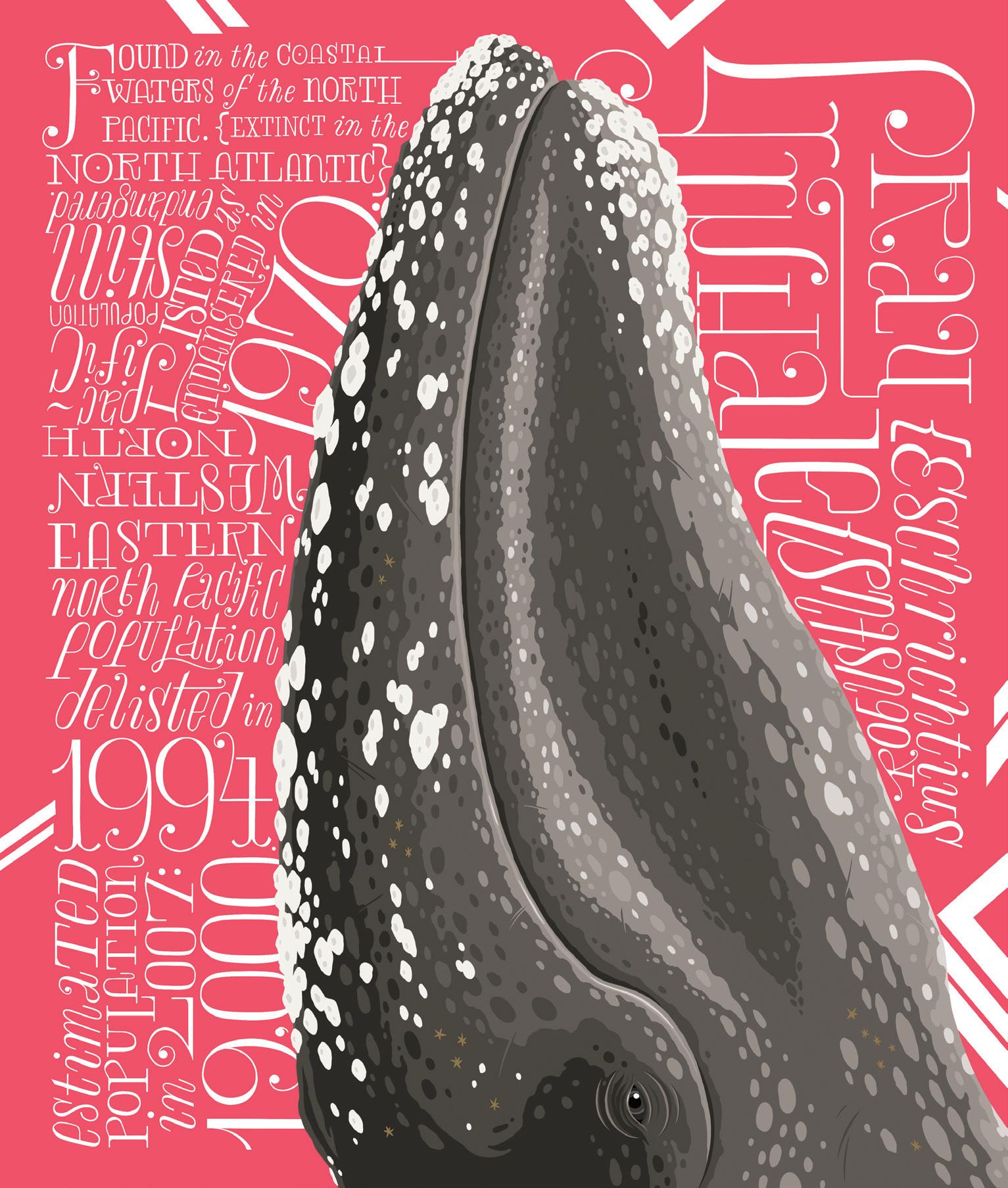

GRAY WHALE

Eschrichtius robustus

Found in the coastal waters of the North Pacific {extinct in the North Atlantic}.

Estimated population in 2007: 19,000.

Listed as endangered in 1970.

Eastern North Pacific population delisted in 1994.

Western North Pacific population still endangered.

58

(previous page)

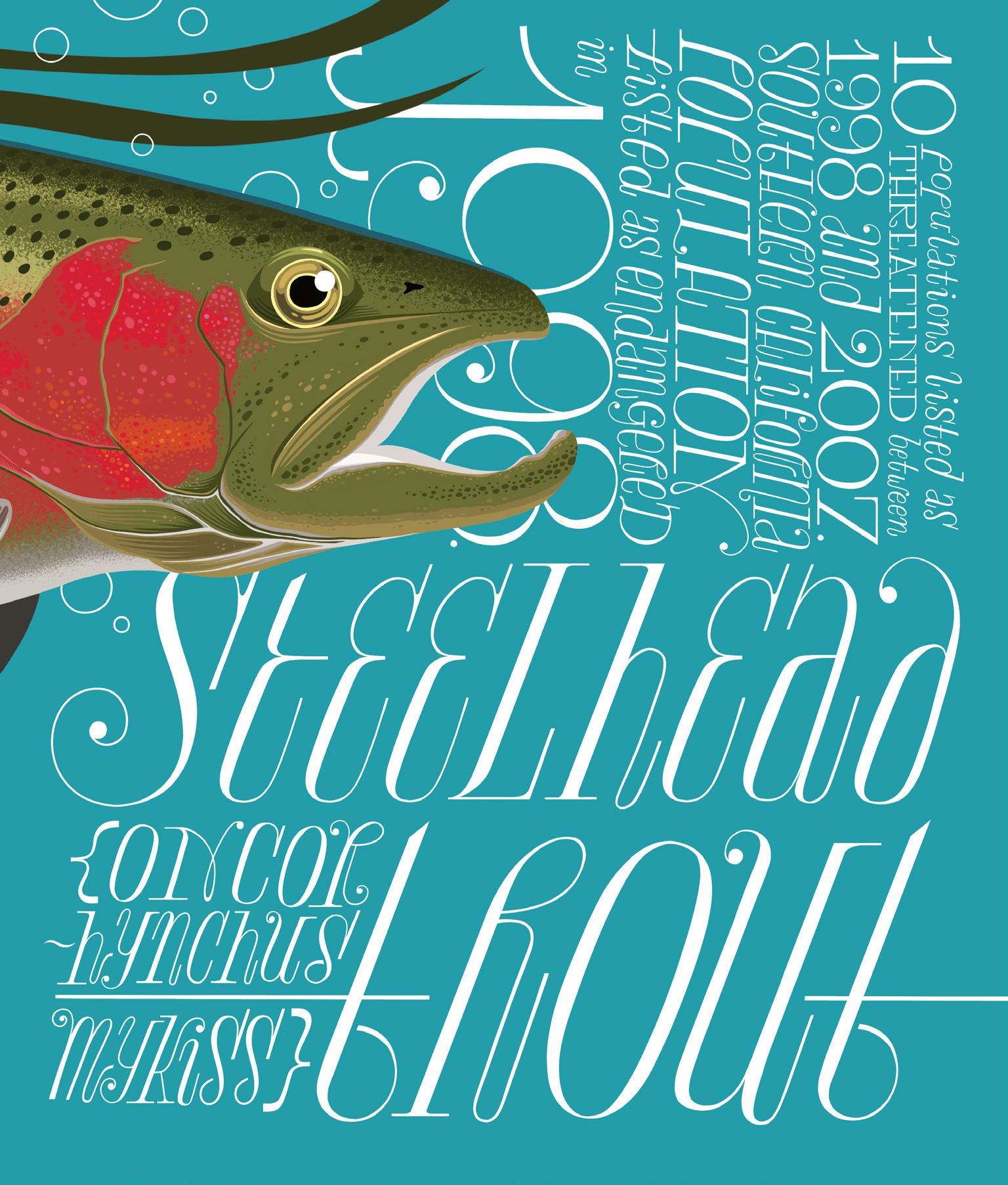

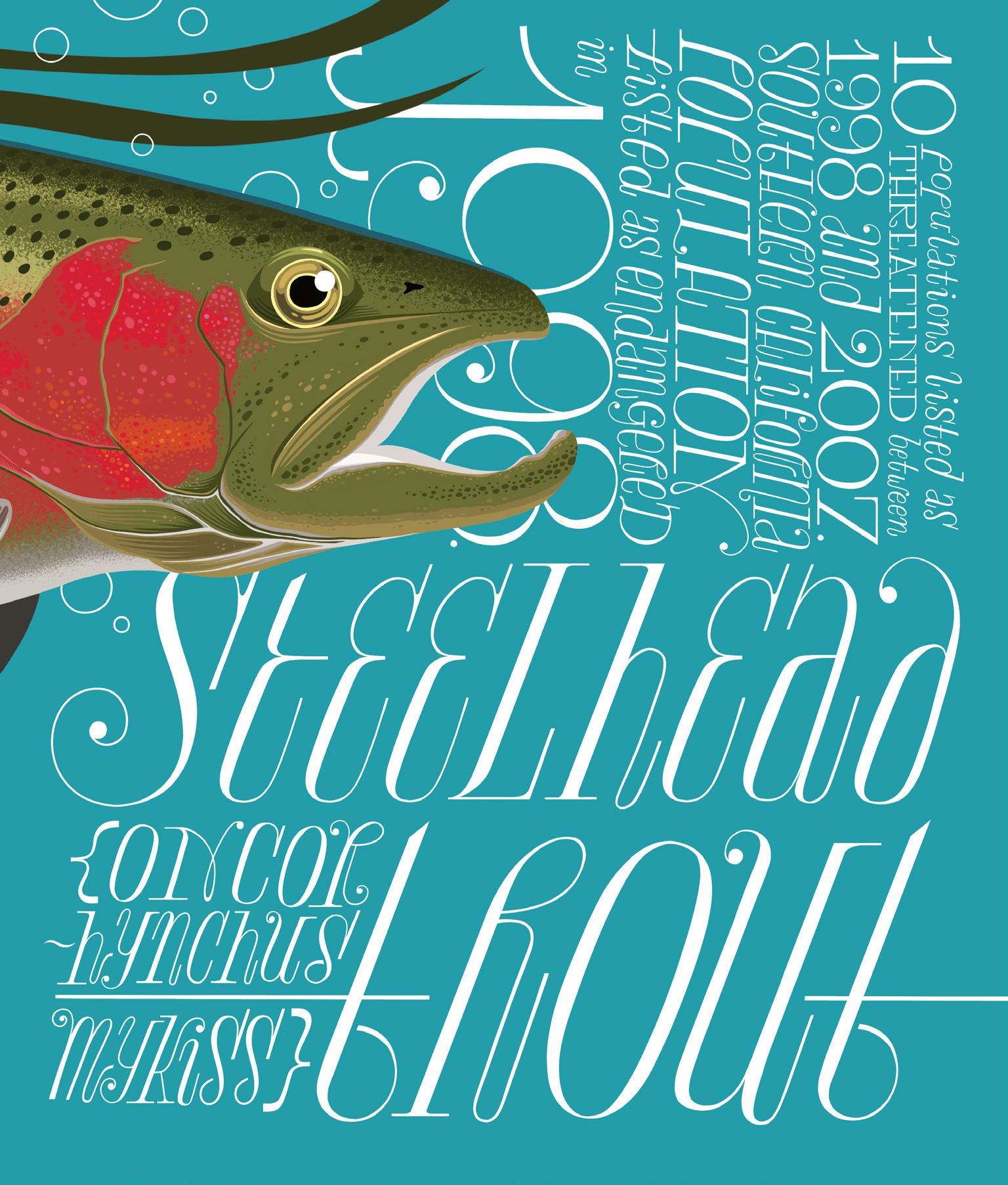

STEELHEAD TROUT Oncorhynchus mykiss

Oceangoing form of rainbow trout.

Found in the tributaries and coastal waters of the North Pacific.

Causes of population decline along US West Coast include habitat loss due to dams, pollution, concrete channels, groundwater pumping, heat island effects, and other byproducts of urbanization.

10 populations listed as threatened between 1998 and 2007.

Southern California population listed as endangered in 1998.

HAWKSBILL SEA TURTLE Eretmochelys imbricata

Found in the coastal waters of the Eastern Seaboard and the Gulf states.

The overhunting for its valuable shell is a main cause of its population decline. Listed as endangered in 1970.

62

ATLANTIC STURGEON

Acipenser oxyrinchus oxyrinchus

Only 22 of the 38 historical river systems now have breeding populations.

4 regional populations between New York and Georgia were listed as endangered in 2012.

Gulf of Maine population listed as threatened in 2012.

64

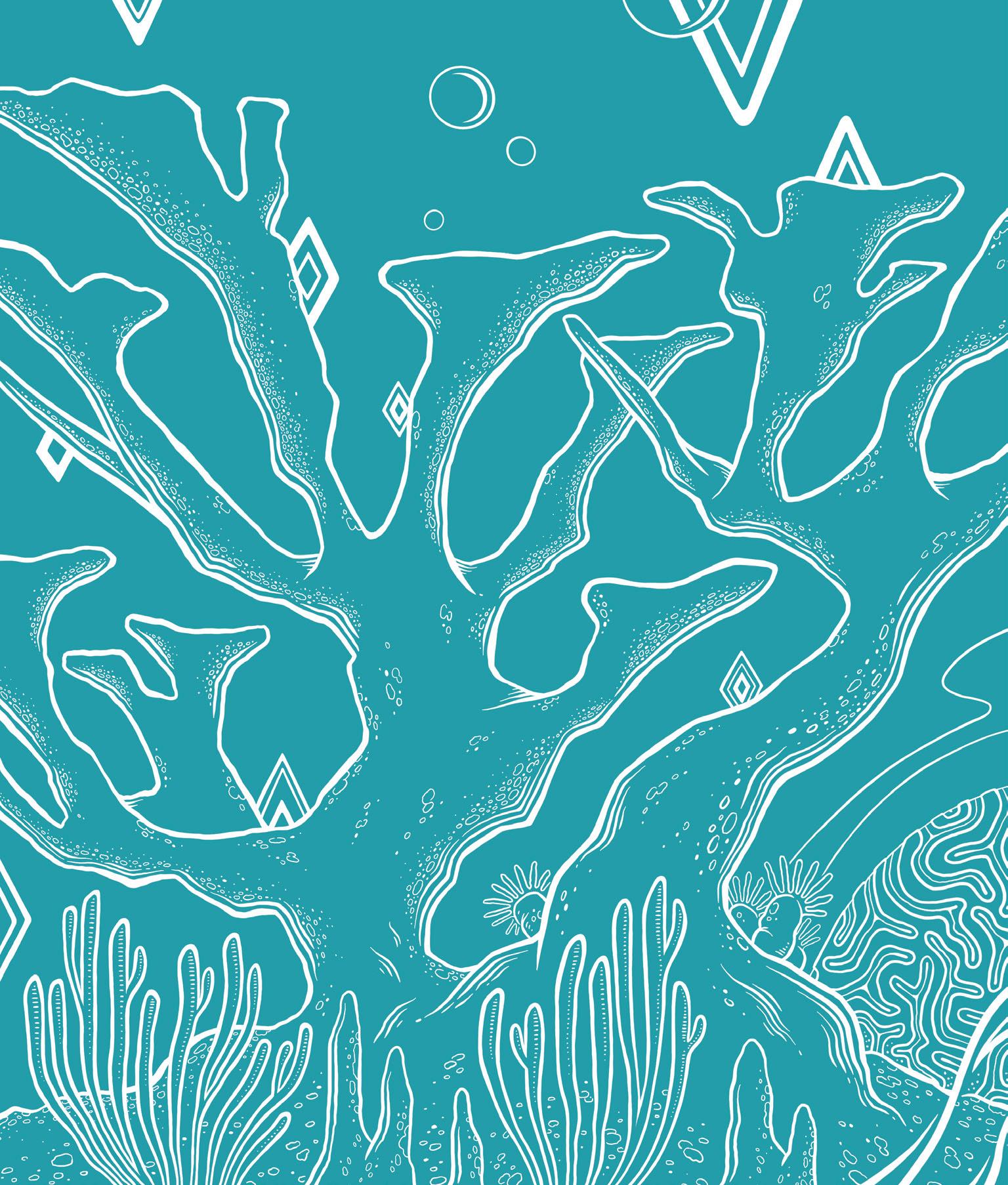

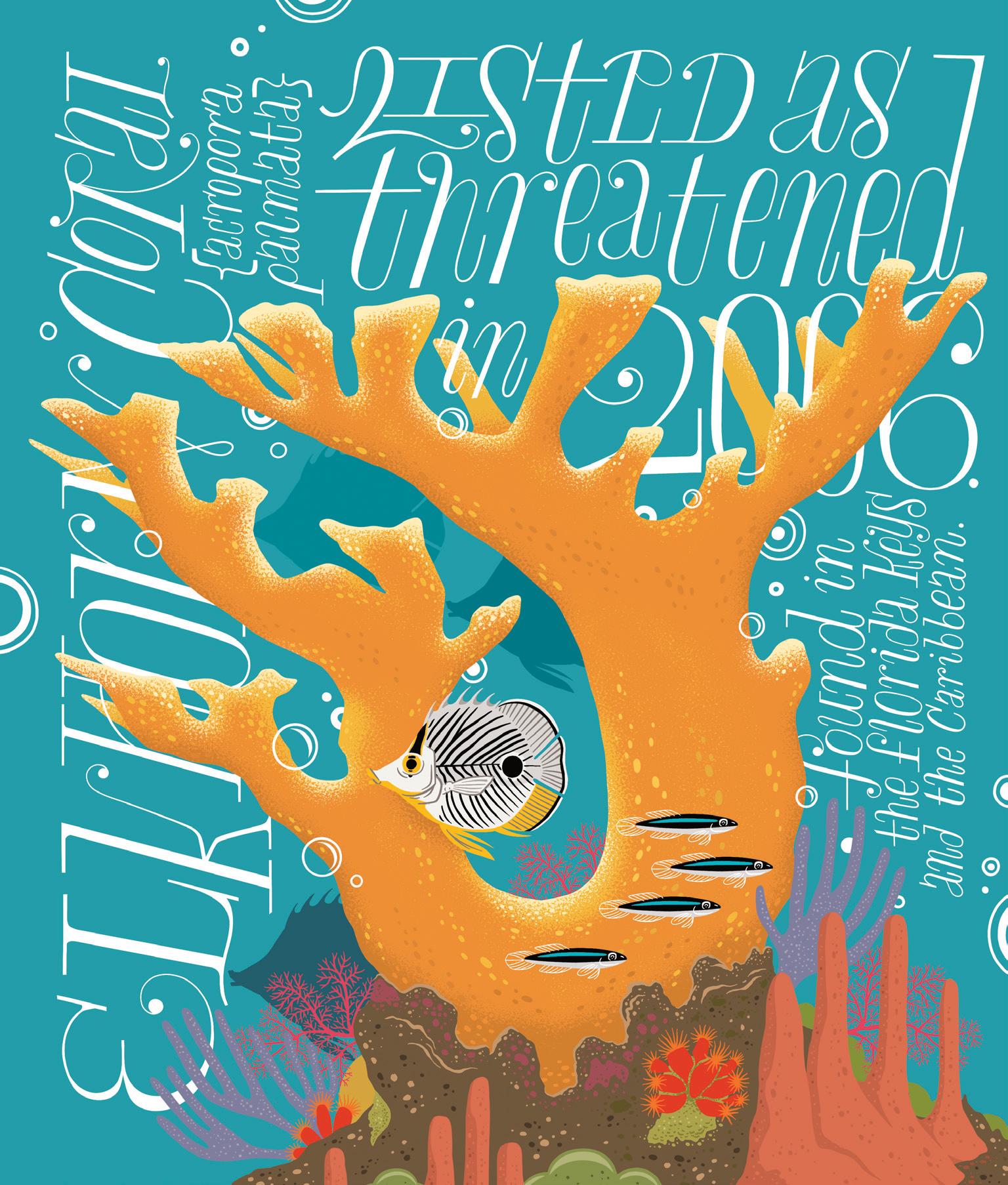

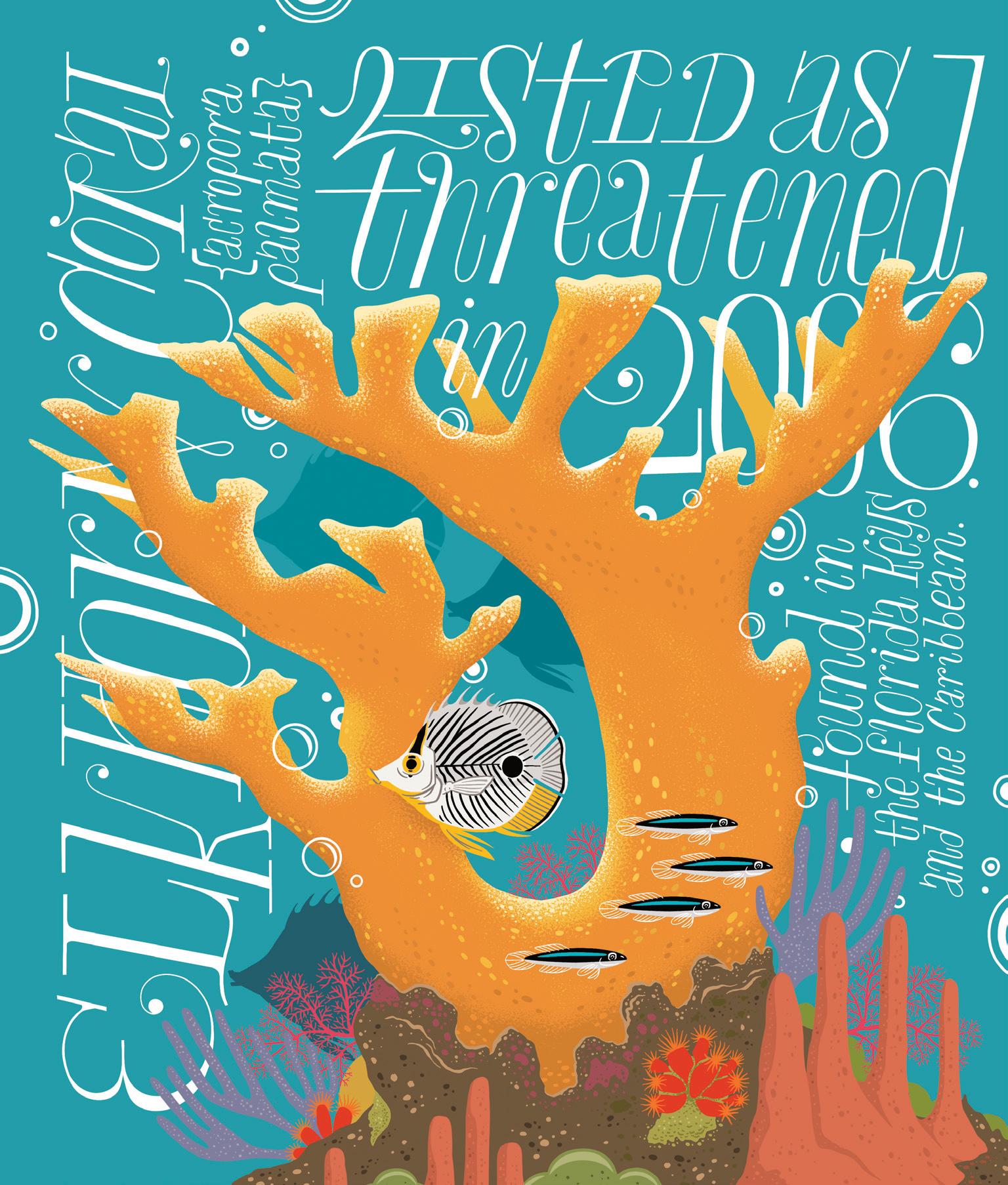

ELKHORN CORAL

Acropora palmata

Found in the Florida Keys and Caribbean.

Listed as threatened in 2006.

66

(previous page)

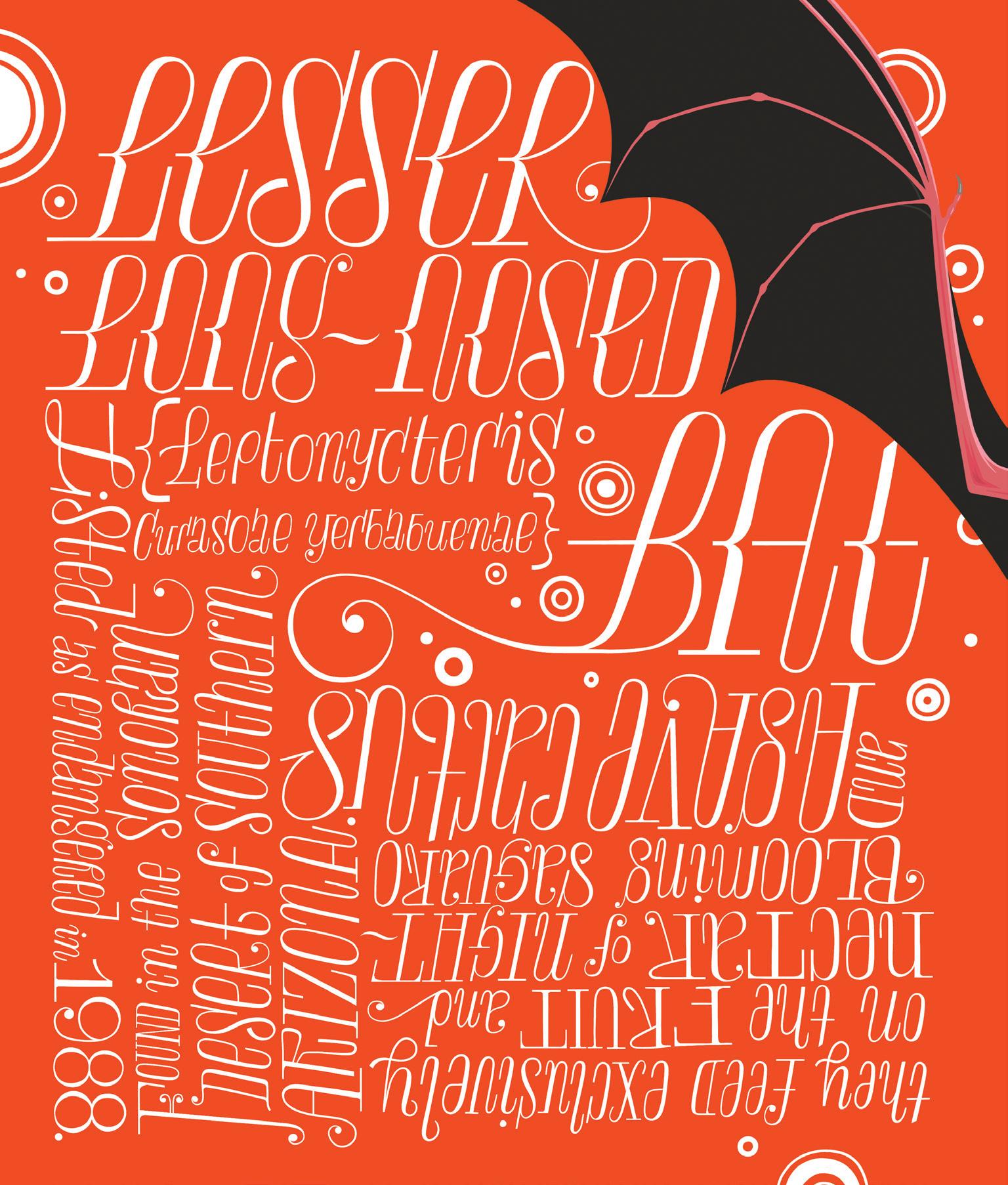

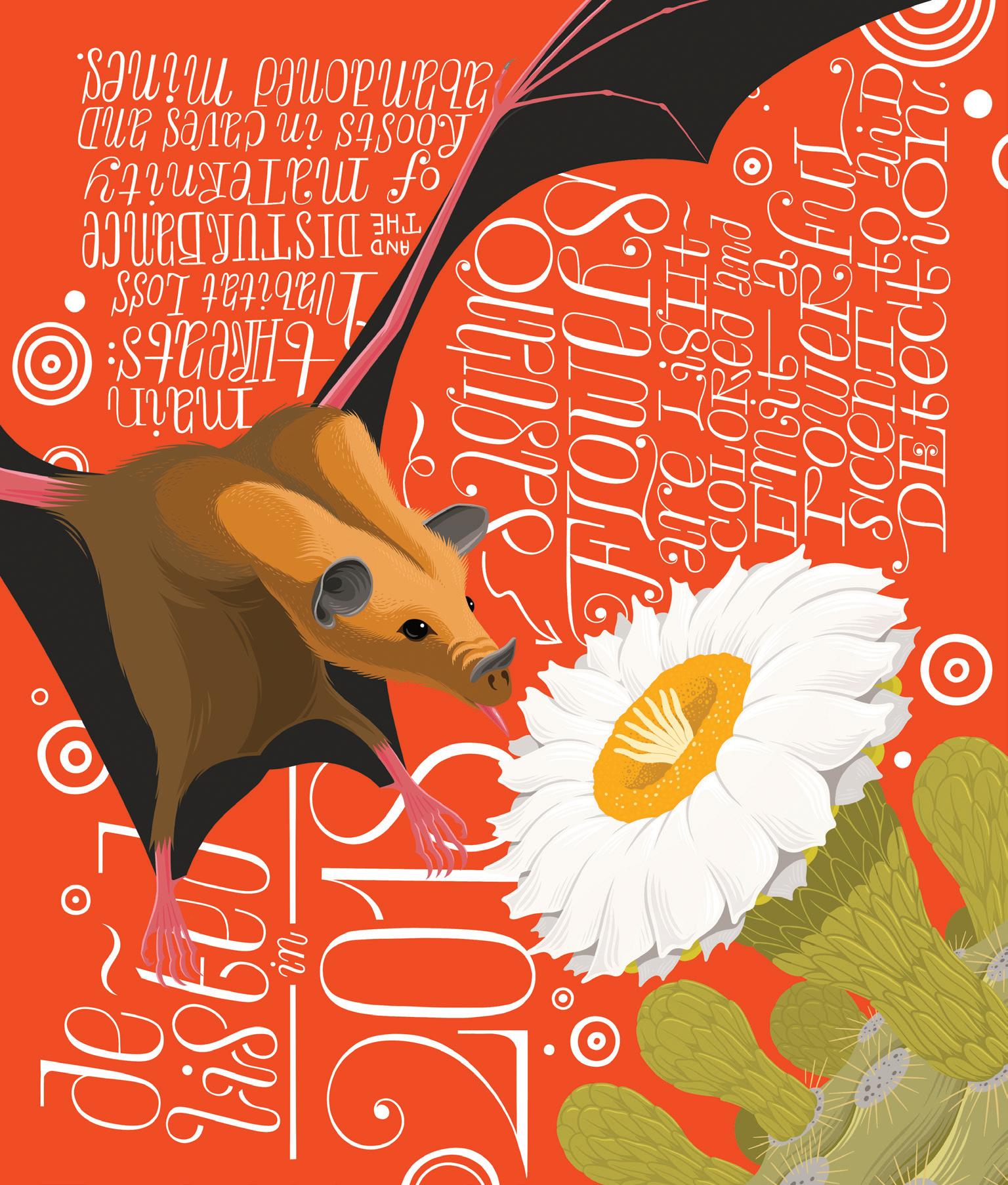

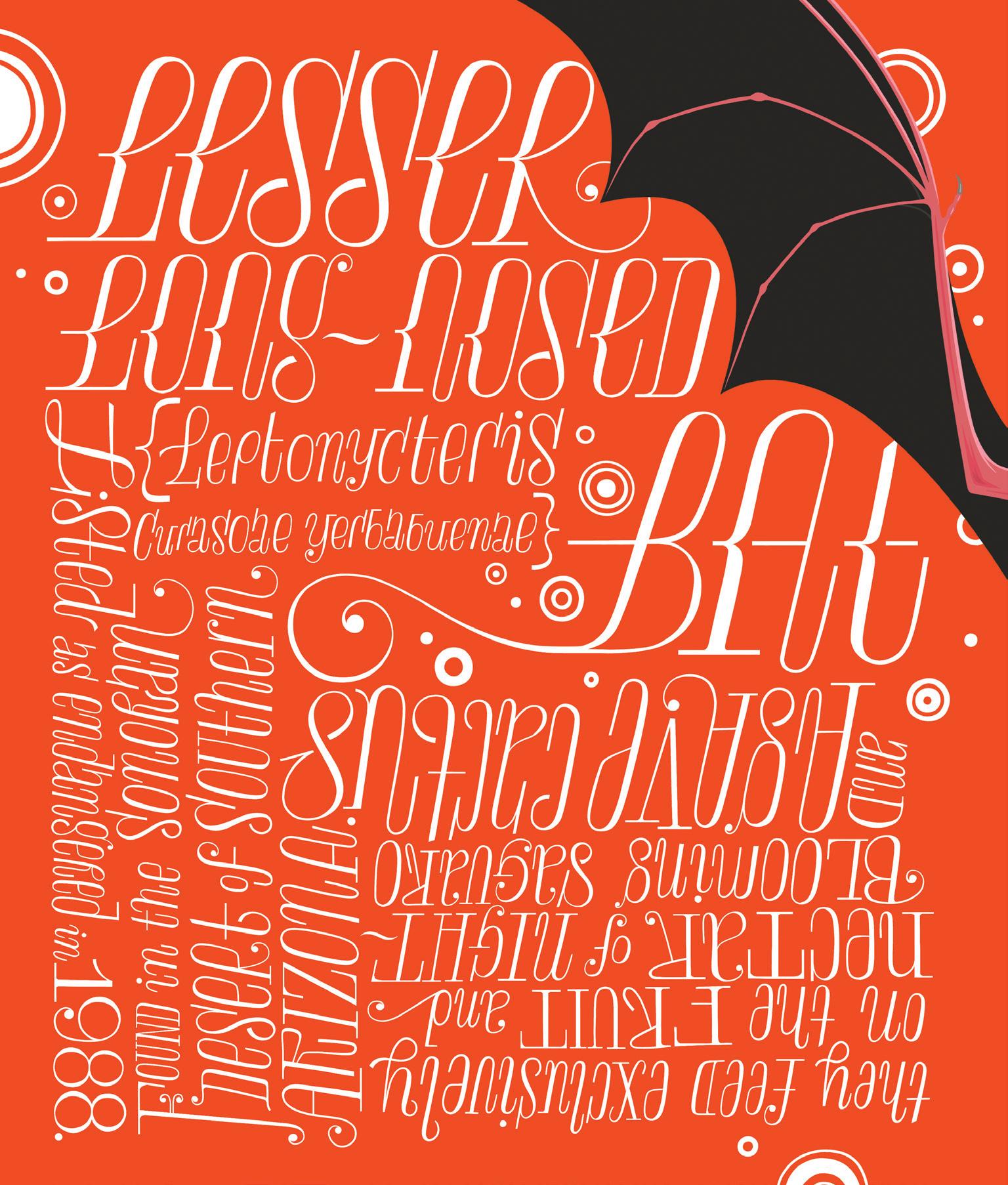

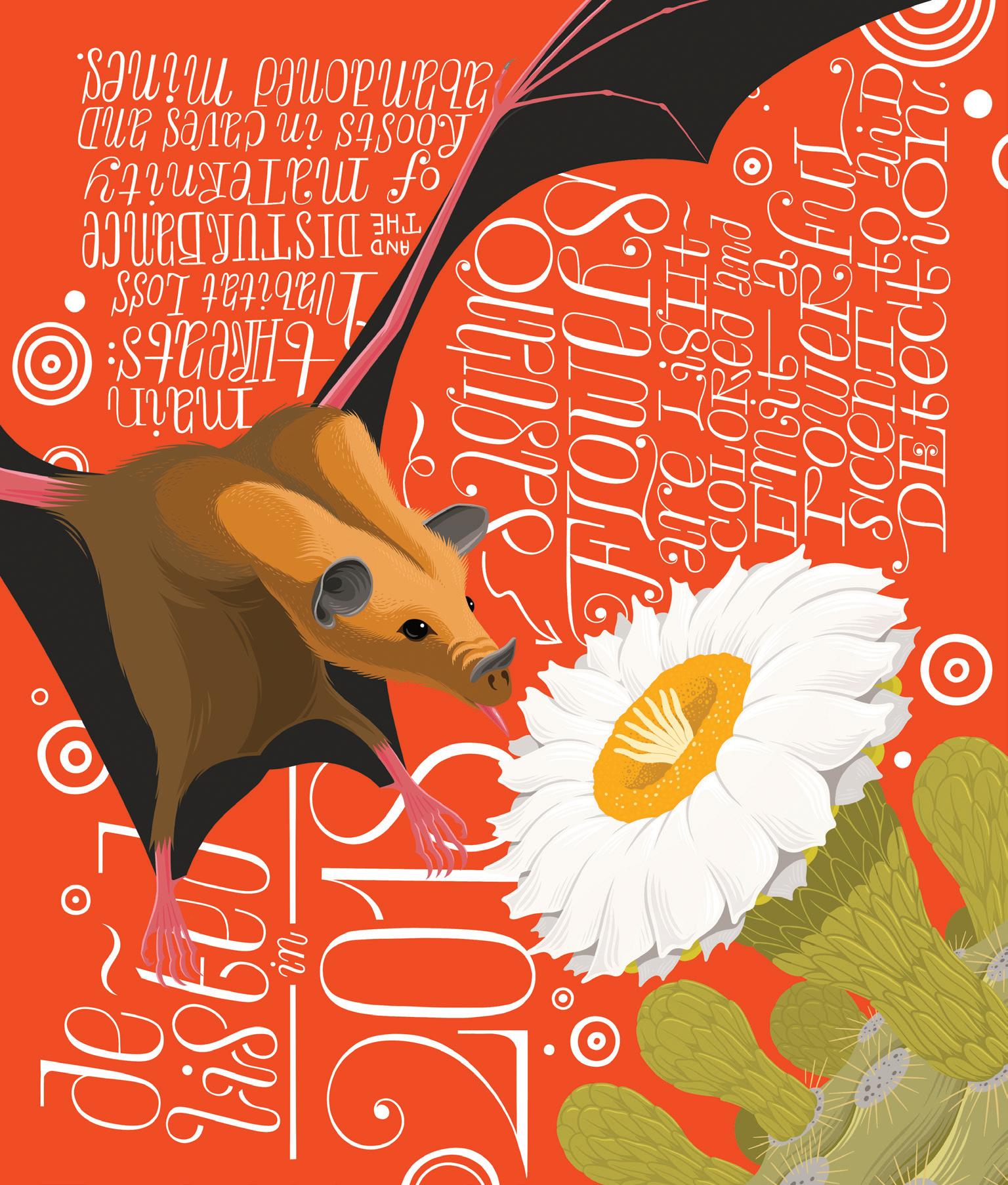

LESSER LONG-NOSED BAT

Leptonycteris curasoae yerbabuenae

Found in the Sonoran Desert of southern Arizona.

They feed exclusively on the fruit and nectar of night-blooming saguaro and agave cactus.

Saguaro flowers are light colored and emit a powerful scent to aid detection.

Main threats include habitat loss and the disturbance of maternity roosts in caves and abandoned mines.

Listed as endangered in 1988.

Delisted in 2018.

MOJAVE DESERT TORTOISE

Gopherus agassizii

Lives in the Mojave and Sonoran Deserts north and west of the Colorado River.

Listed as threatened in 1980.

Rate of decline since 1980: 90%.

72

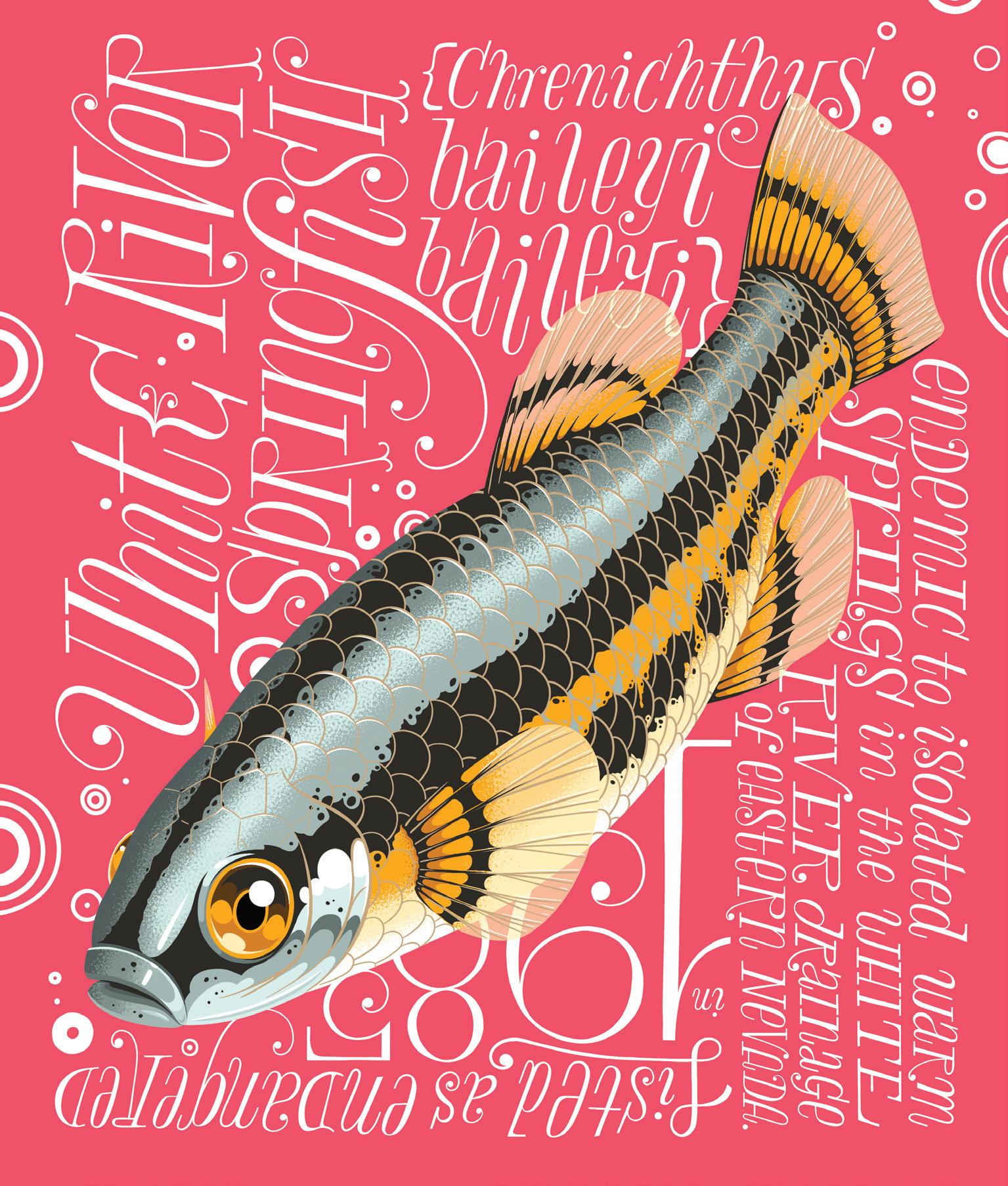

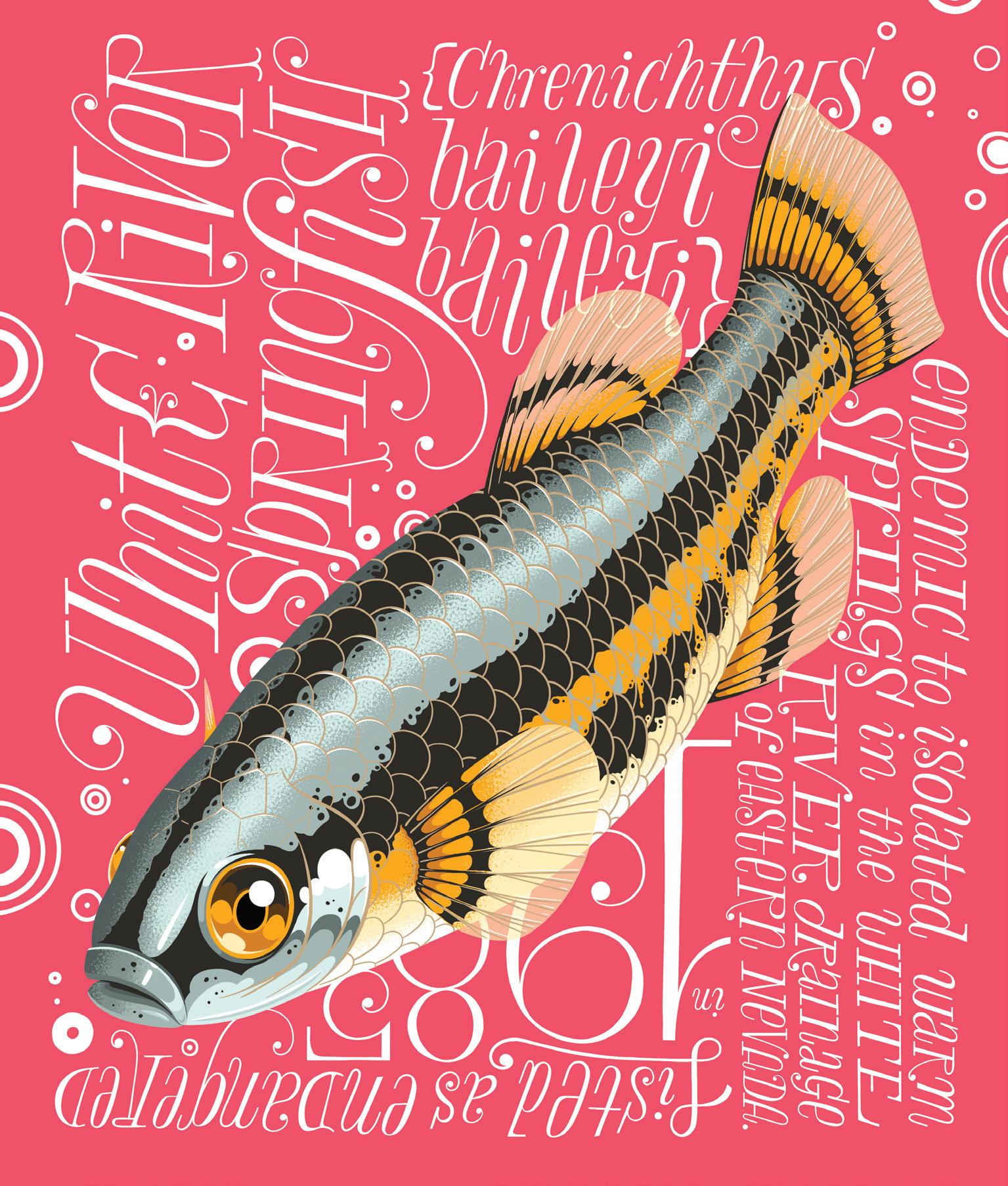

WHITE RIVER SPRINGFISH

Crenichthys baileyi baileyi Endemic to isolated warm springs in the White River drainage of eastern Nevada.

Listed as endangered in 1985.

74

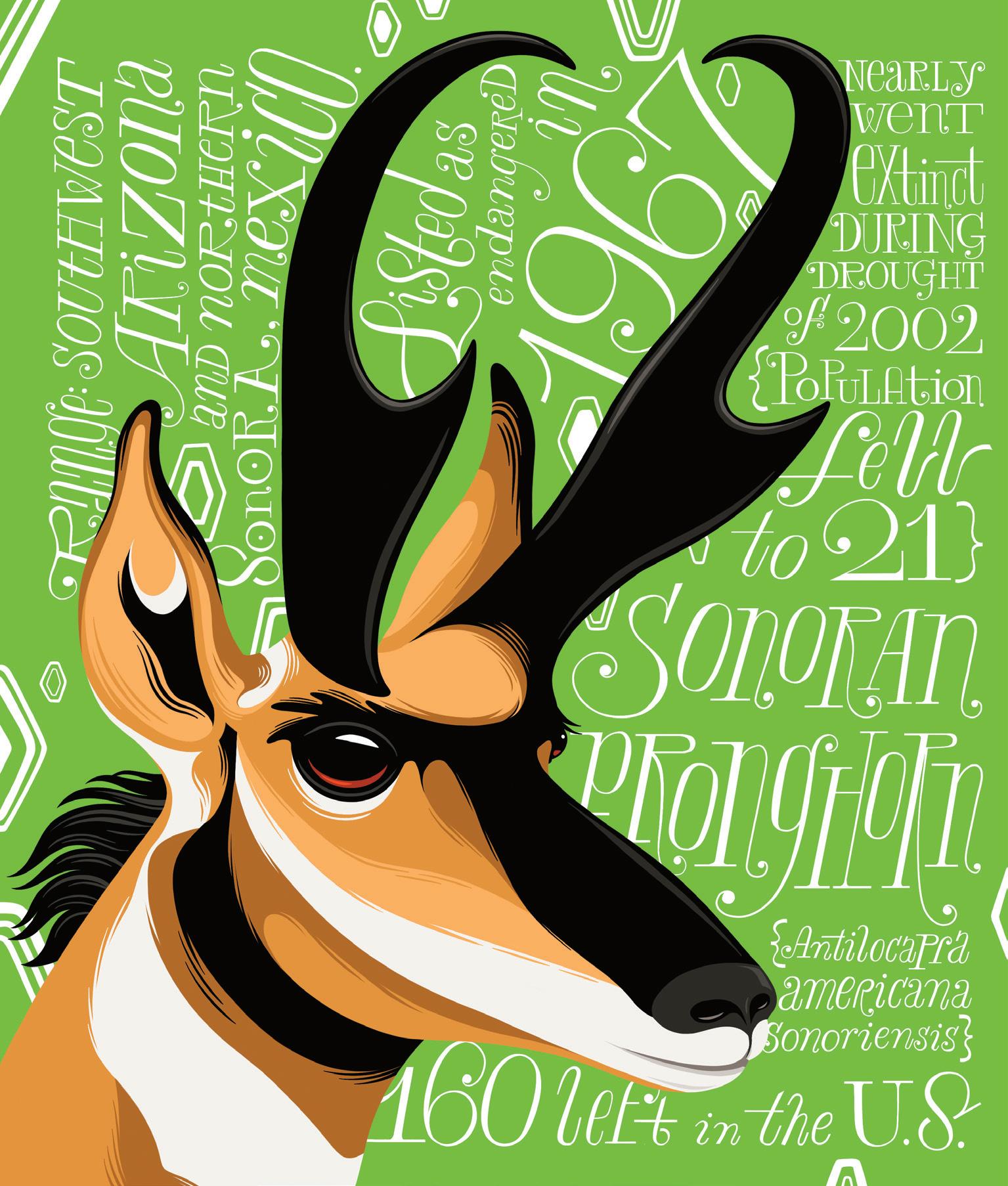

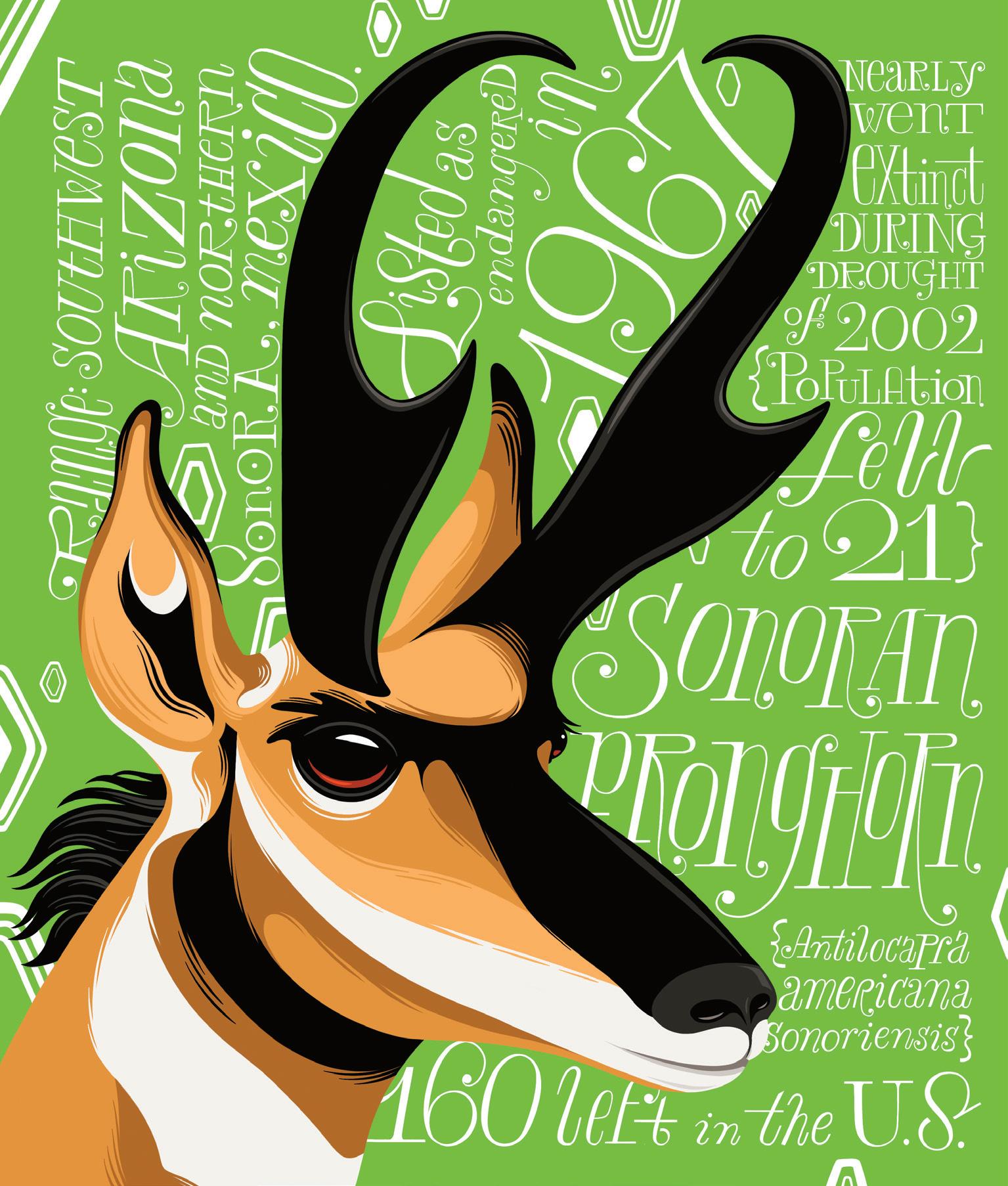

SONORAN PRONGHORN

Antilocapra americana sonoriensis

Found in southwestern Arizona and northern Sonora, Mexico.

Nearly went extinct during drought of 2002 {population fell to 21}.

160 left in the US.

Listed as endangered in 1967.

(following page)

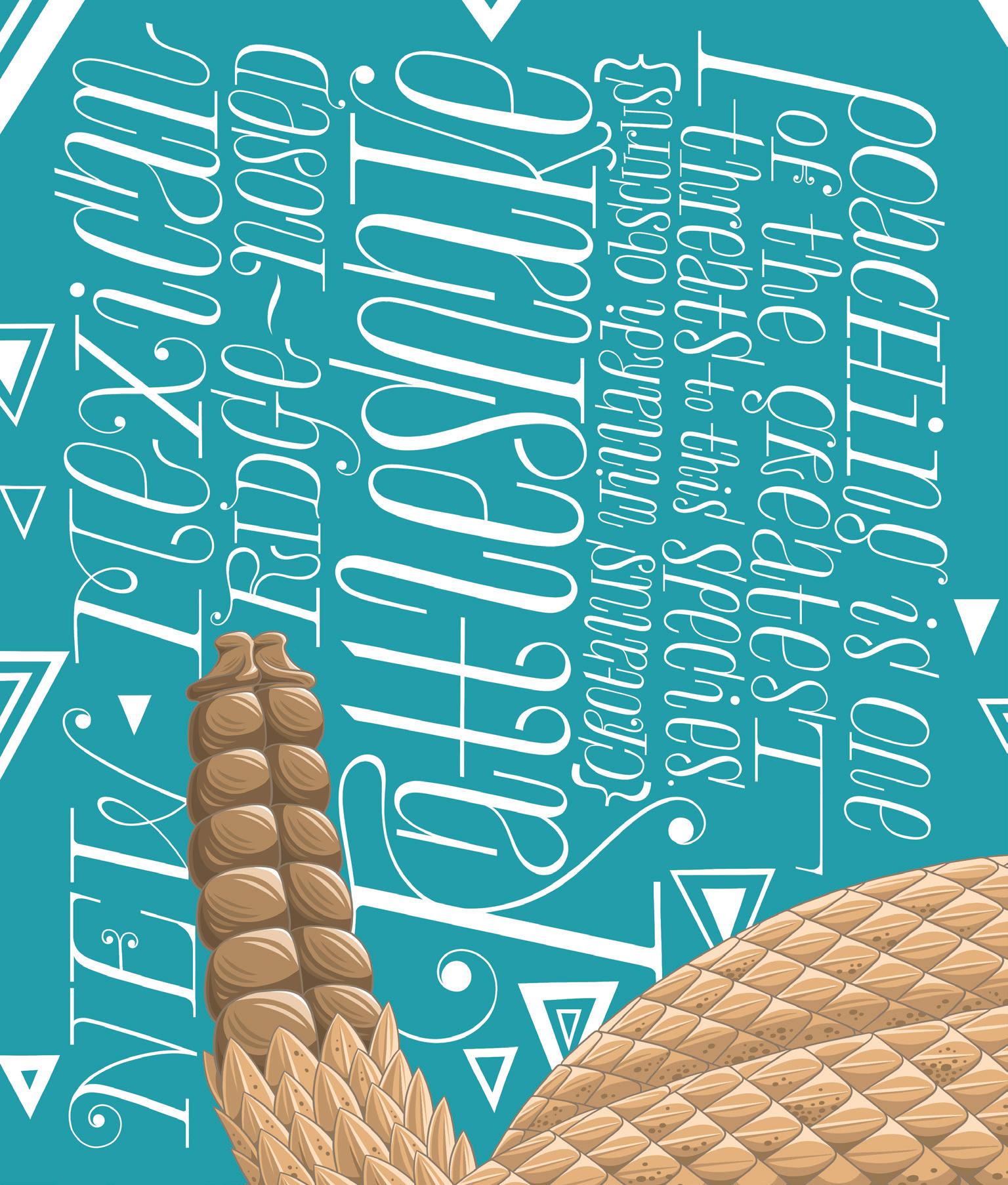

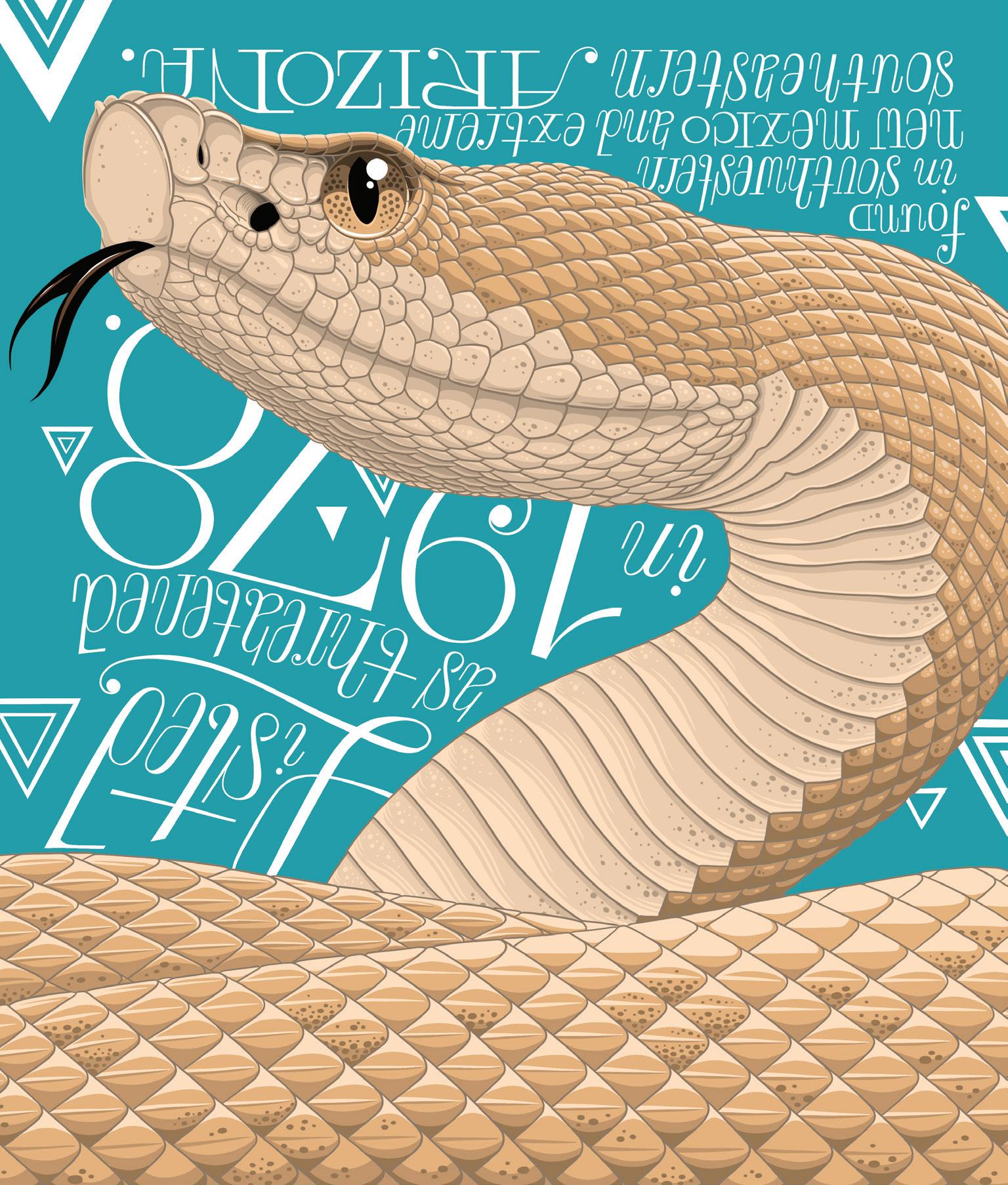

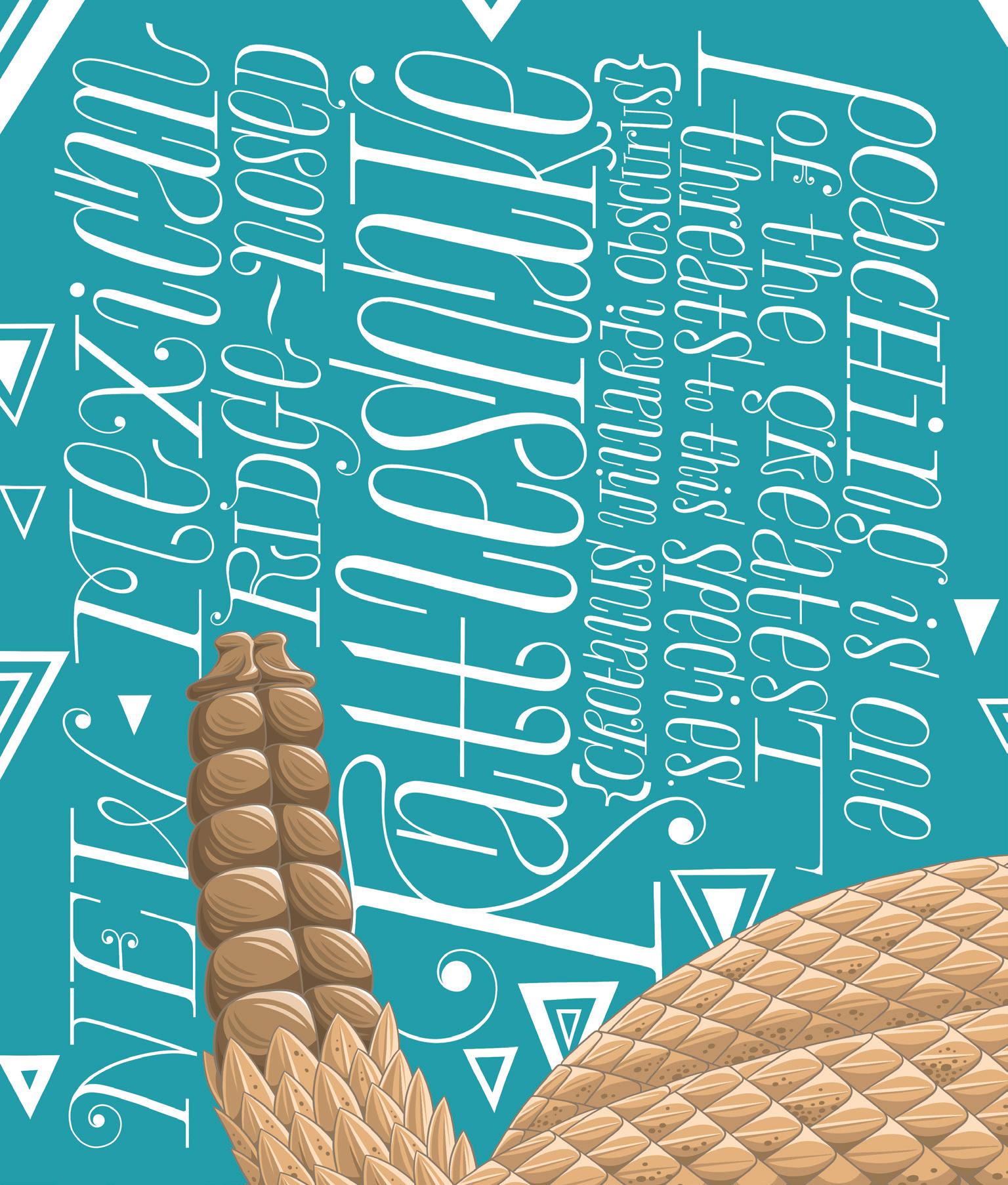

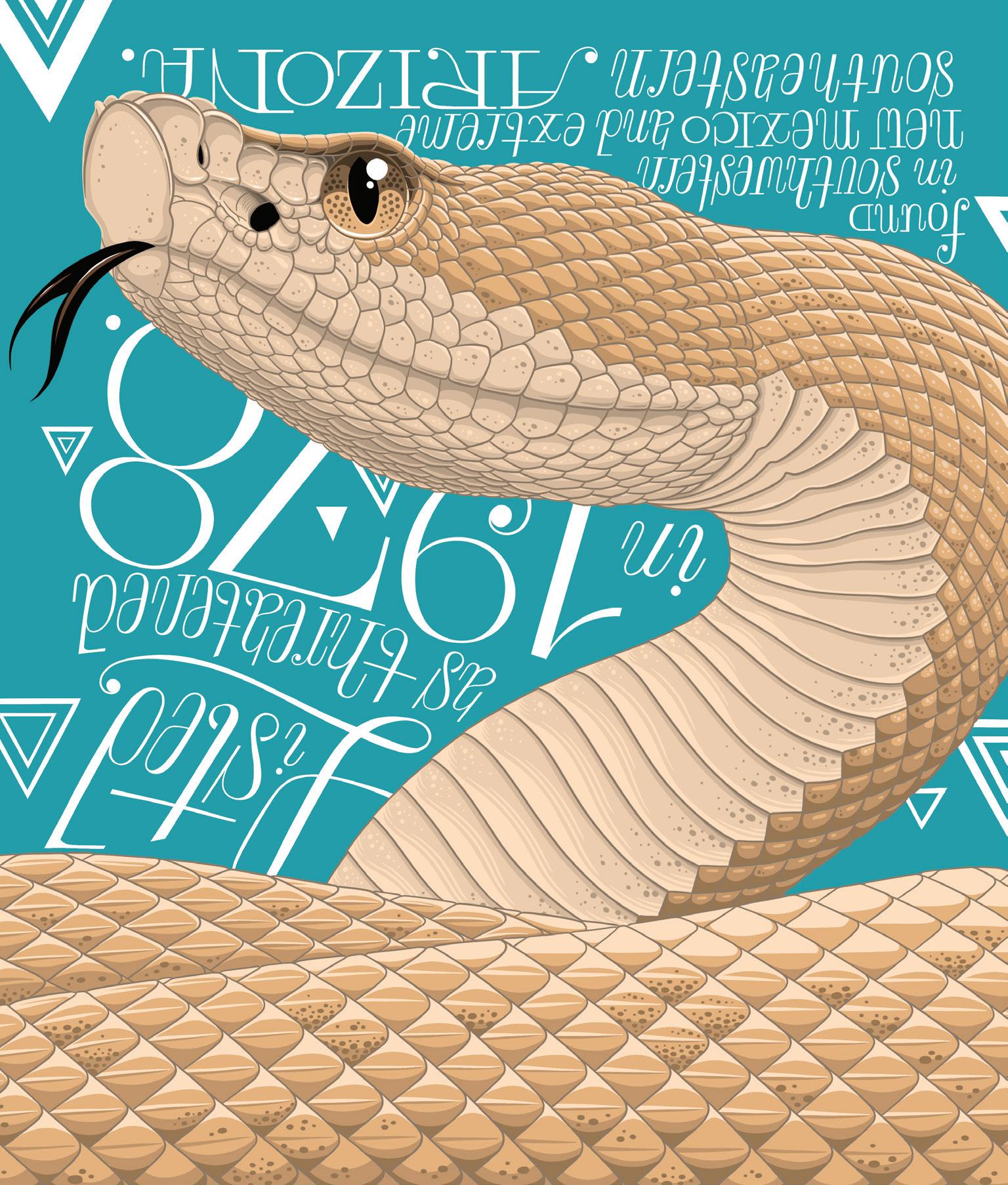

NEW MEXICAN RIDGE-NOSED RATTLESNAKE

Crotalus willardi obscurus

Found in southwestern New Mexico and extreme southeastern Arizona.

Poaching is one of the greatest threats to this species.

Listed as threatened in 1978.

76

SOUTHWESTERN WILLOW FLYCATCHER

Empidonax traillii extimus

Lives and breeds in the dense vegetation around the wetlands and rivers of the southwestern US.

Estimated population in 2016: 2,500. Listed as endangered in 1995.

80

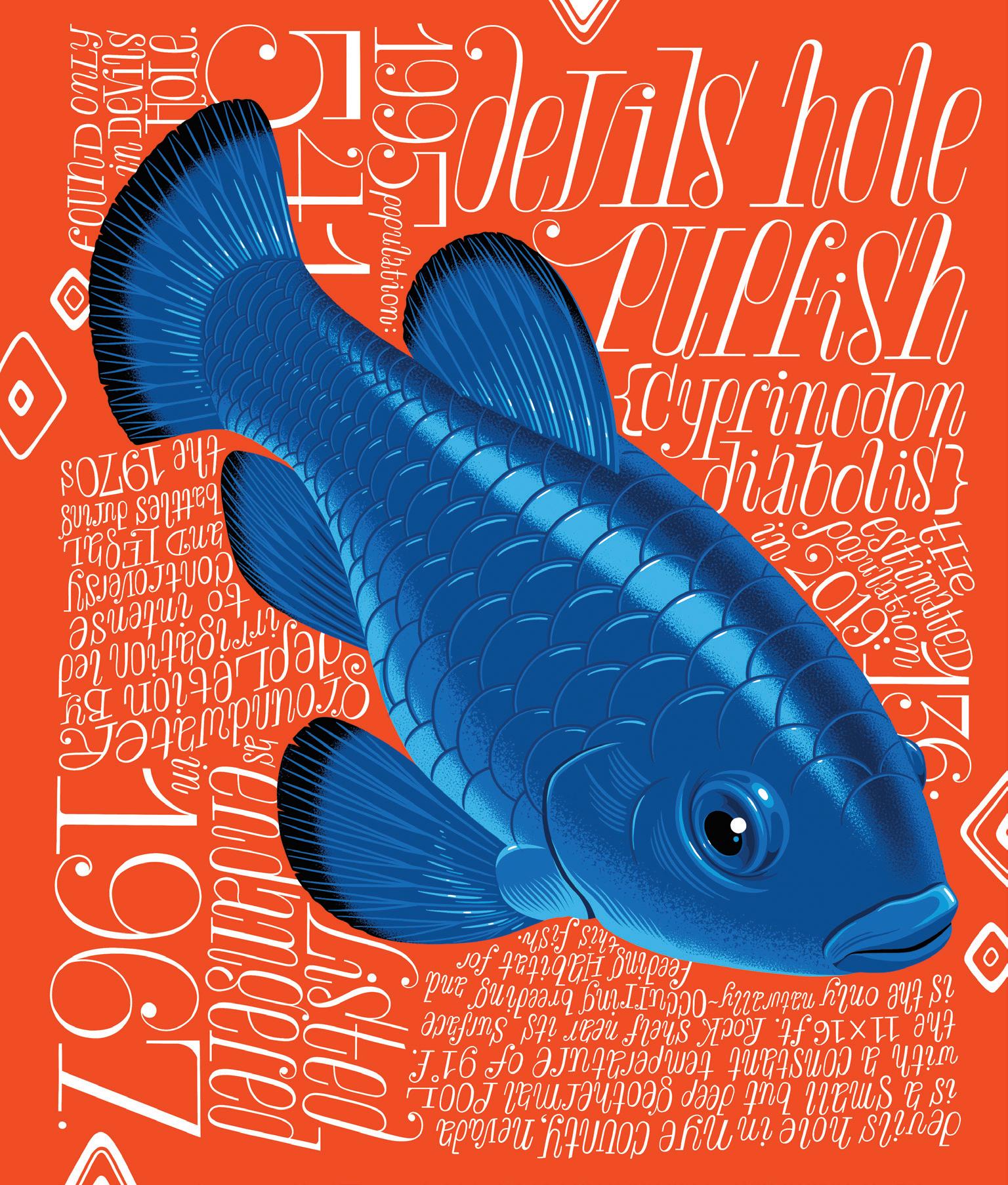

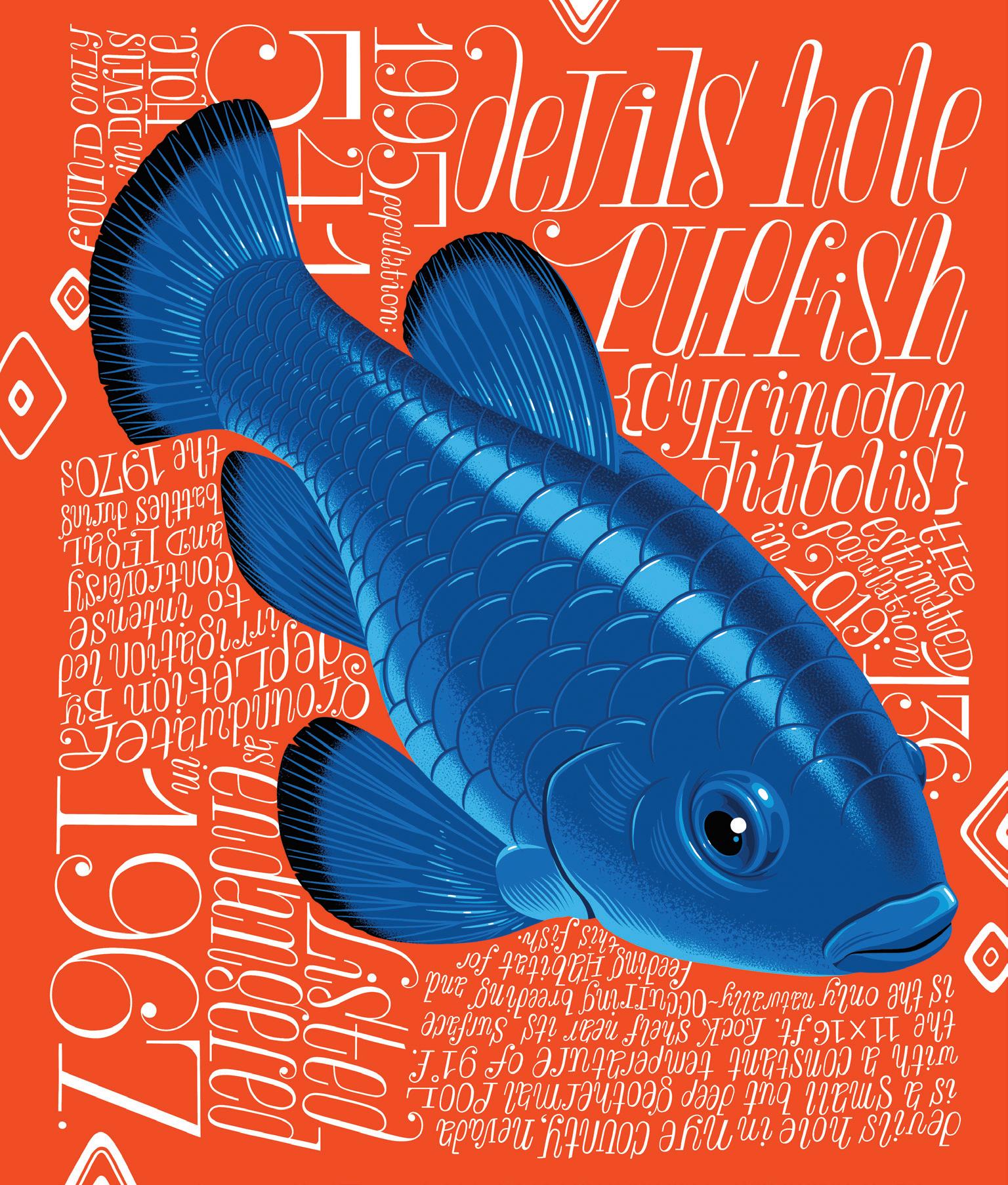

DEVILS HOLE PUPFISH

Cyprinodon diabolis

Found only in Devils Hole, Nye County, Nevada.

Devils Hole is a small but deep geothermal pool with a constant temperature of 91◦ Fahrenheit. The 11' x 16' rock shelf near its surface is the only naturally occurring breeding and feeding habitat for this fish.

Groundwater depletion by irrigation led to intense controversy and legal battles during the 1970s.

Population in 1995: 541.

Estimated population in 2019: 136.

Listed as endangered in 1967.

82

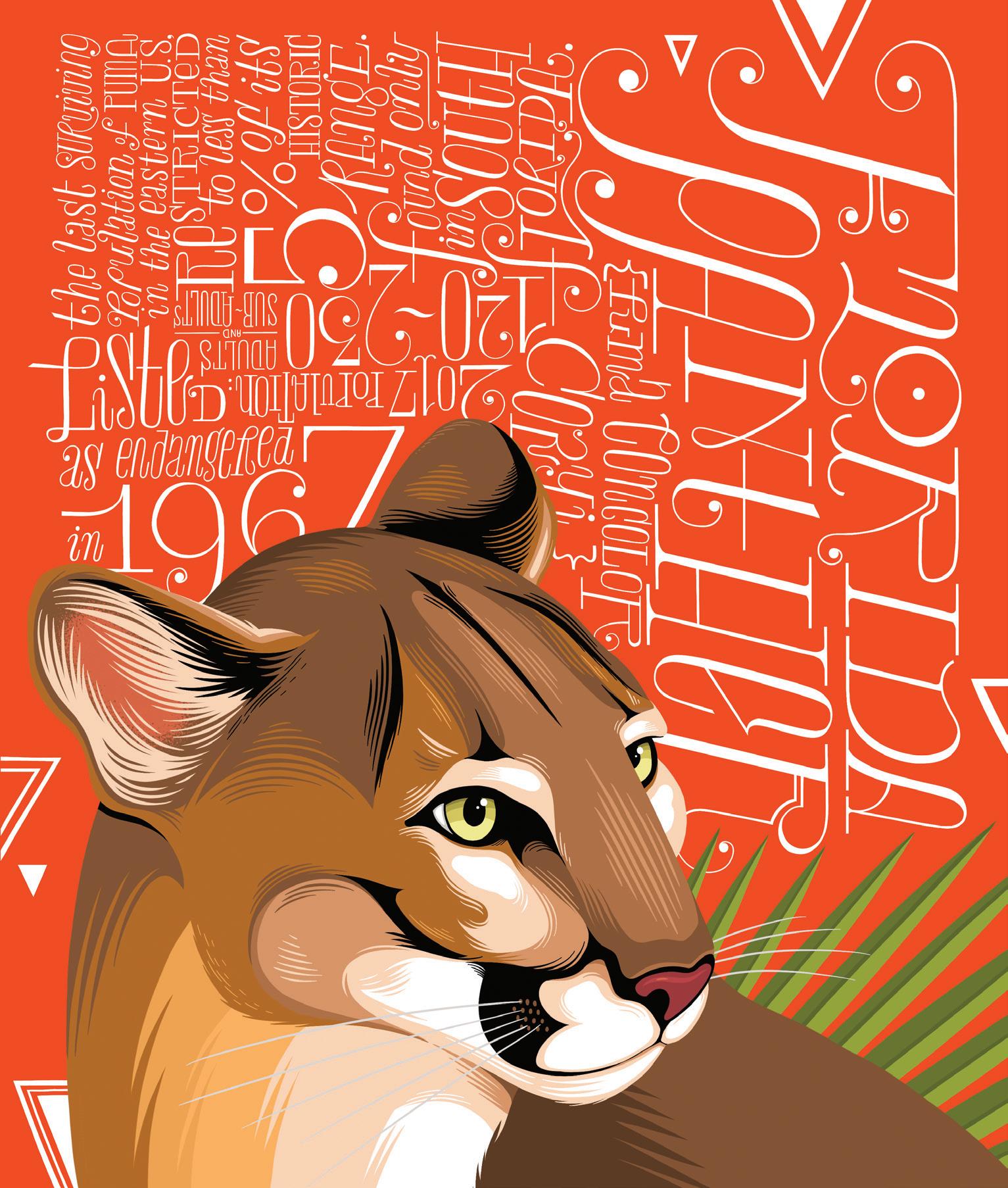

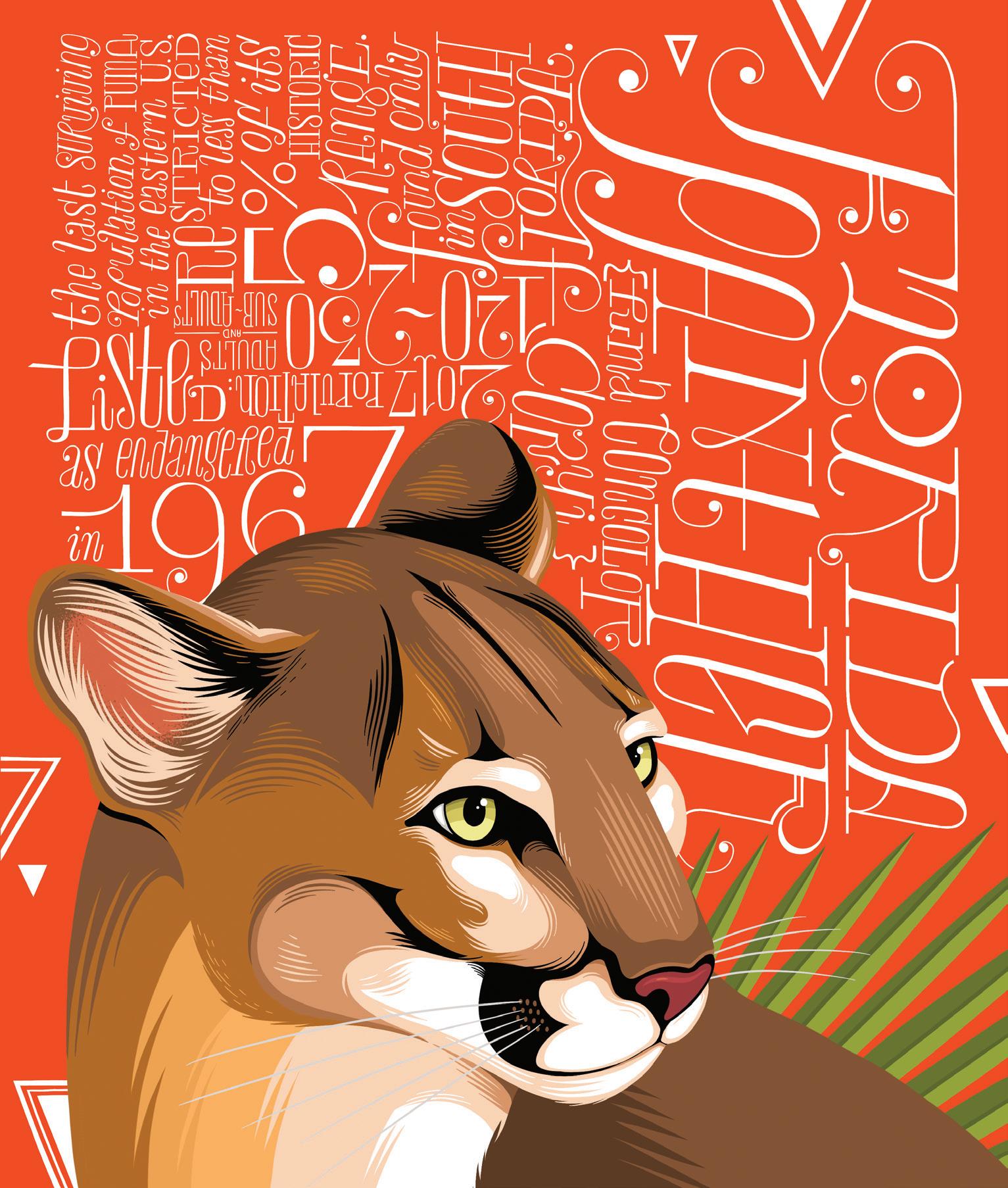

FLORIDA PANTHER

Puma concolor coryi

The last surviving population of puma in the eastern US.

Found only in South Florida. Restricted to less than 5% of its historic range. Population in 2017: 120-230 adults and sub-adults.

Listed as endangered in 1967.

(following page)

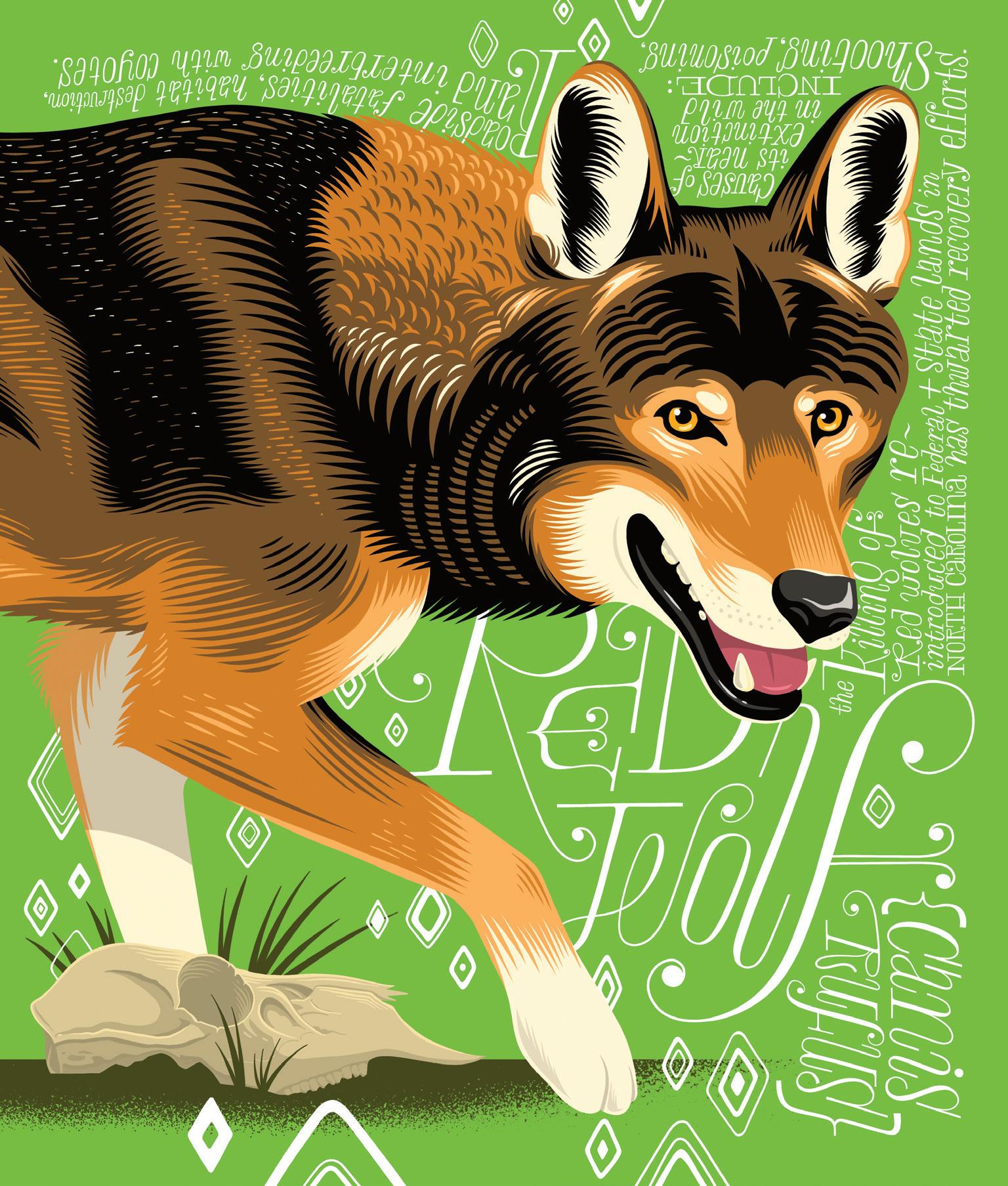

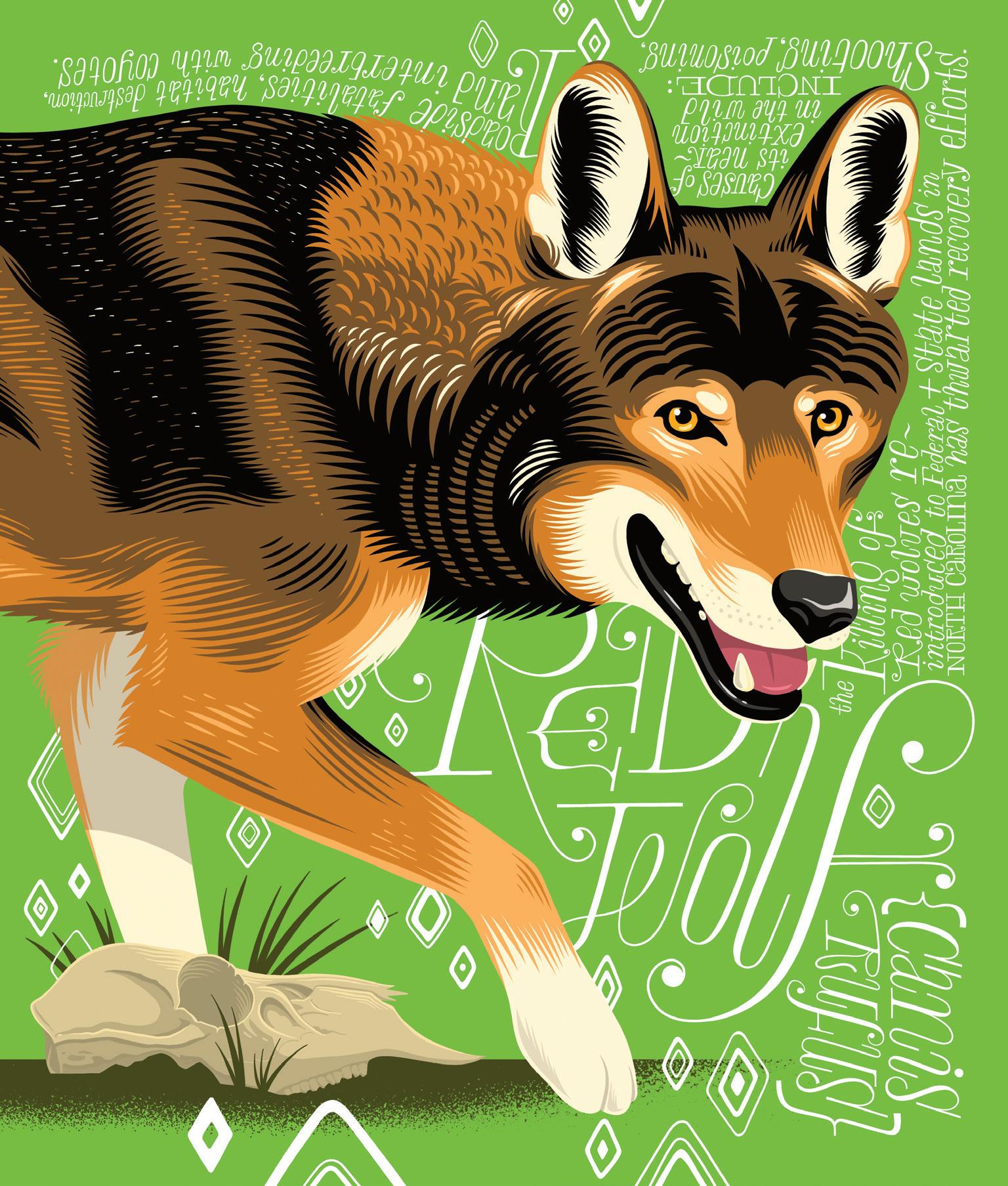

RED WOLF

Canis rufus

Once found throughout the southeastern US. Causes of its near-extinction in the wild include shooting, poisoning, roadside fatalities, habitat destruction, and interbreeding with coyotes.

The killing of red wolves reintroduced to federal and state lands in North Carolina has thwarted recovery efforts.

93 wild red wolves survived in 2007. By 2023 there were less than 20.

Fewer than 235 red wolves survive in captivity.

Listed as endangered in 1967.

86

AMERICAN PEREGRINE FALCON

Falco peregrinus anatum

Found in southwestern Texas to the southern Rockies and the California coast.

Listed as endangered in 1970.

Delisted in 1999.

(following page)

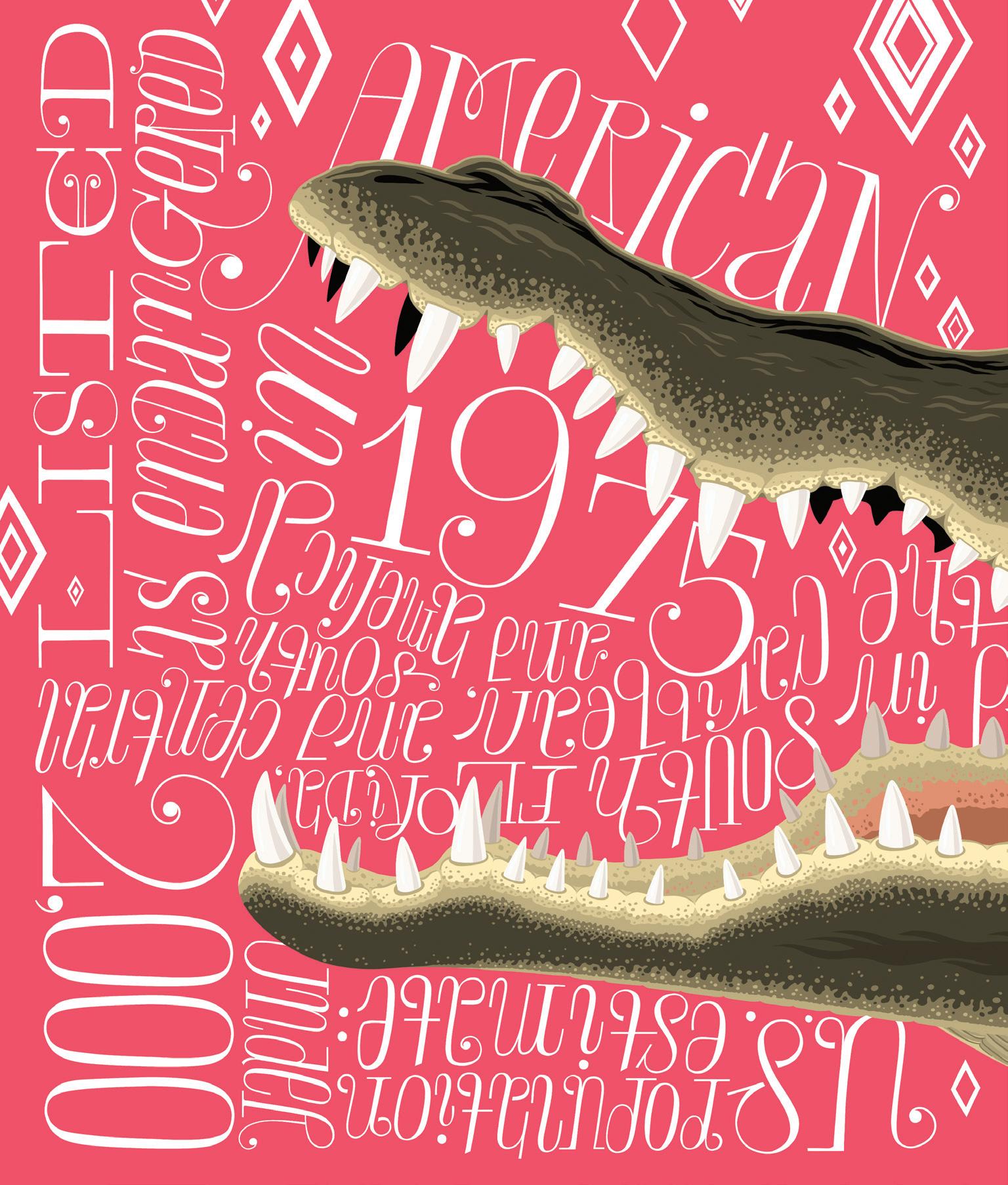

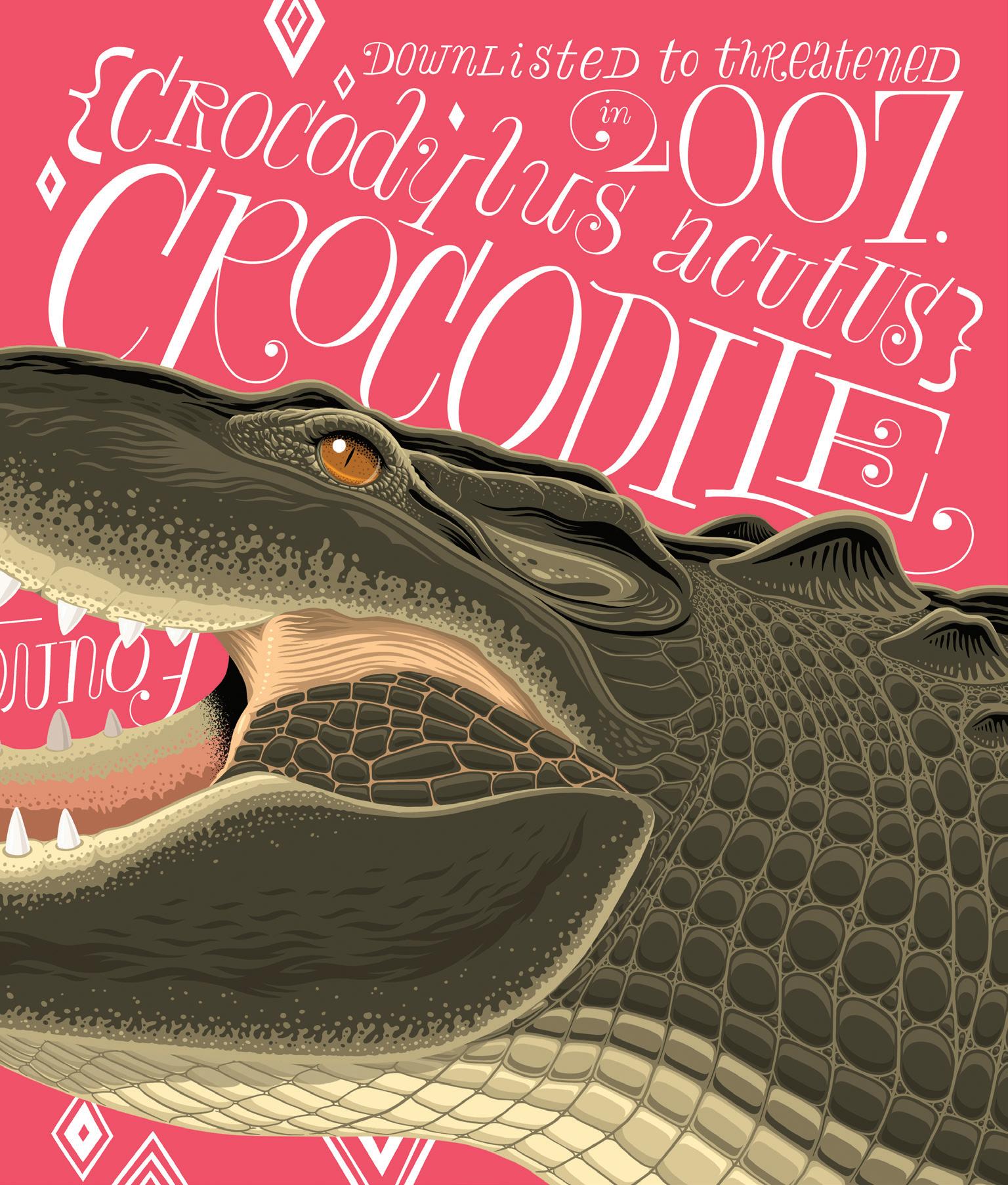

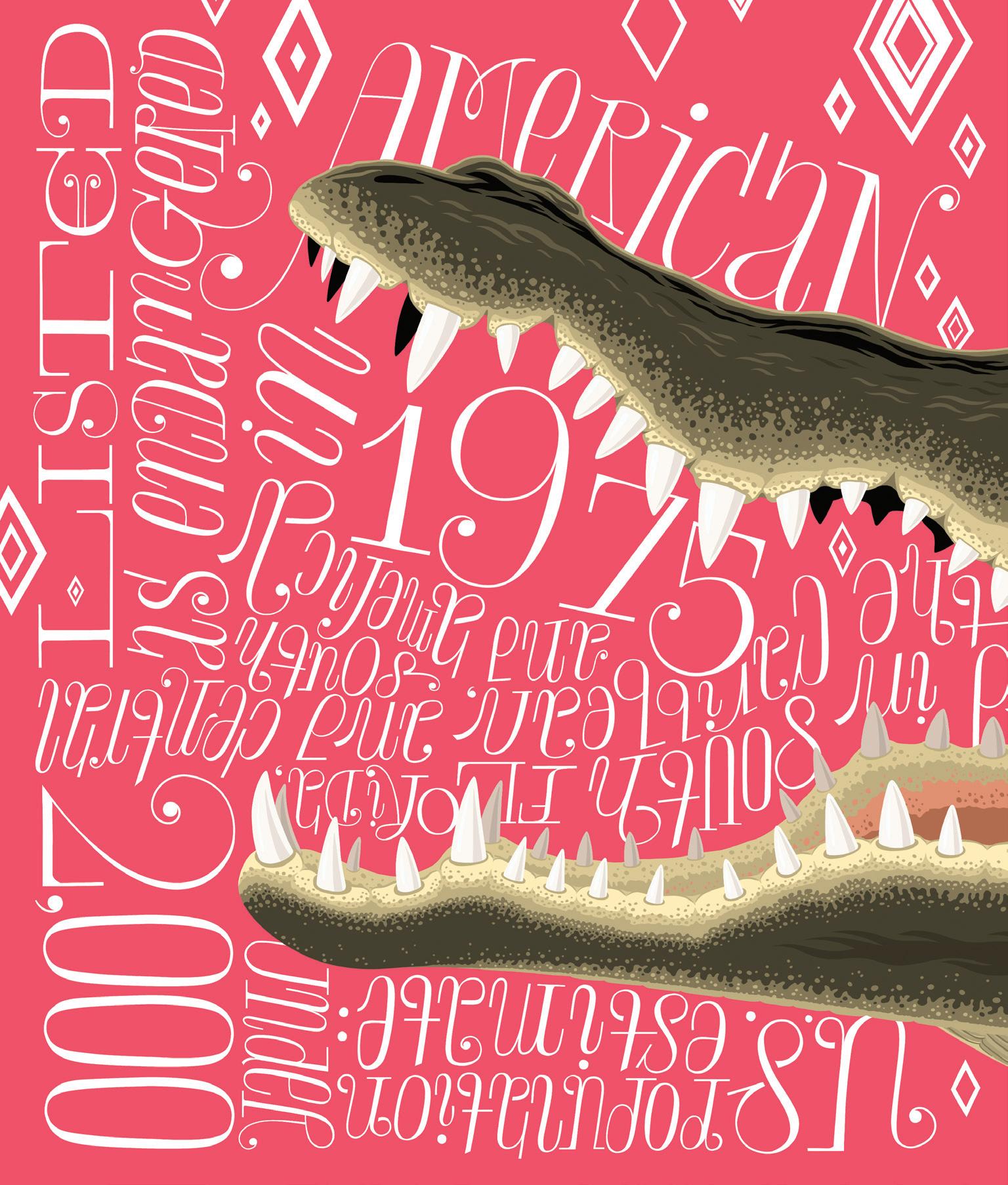

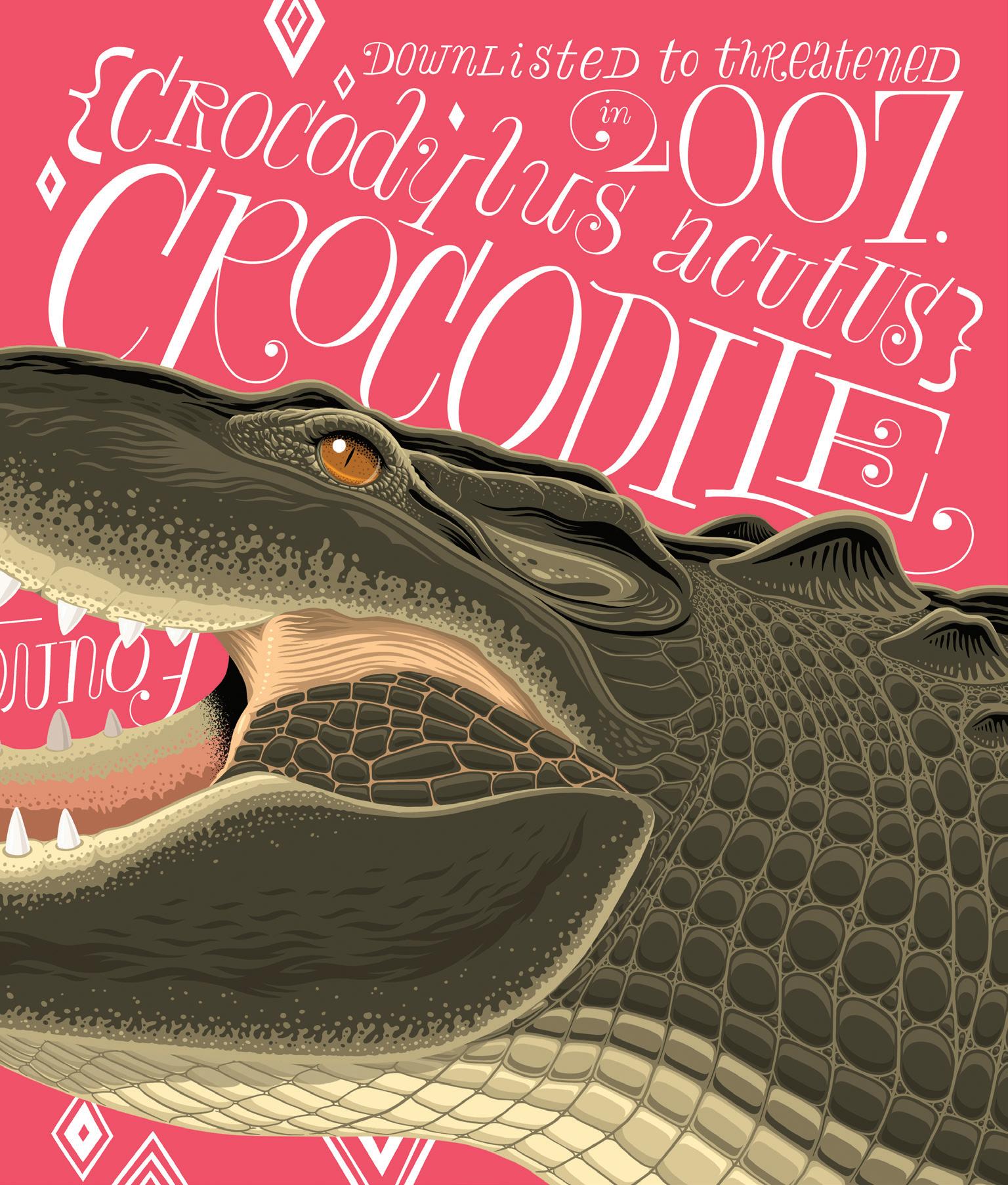

AMERICAN CROCODILE Crocodylus acutus

Found in South Florida, the Caribbean, and Central and South America.

US population estimate: under 2,000.

Listed as endangered in 1975.

Downlisted to threatened in 2007.

90

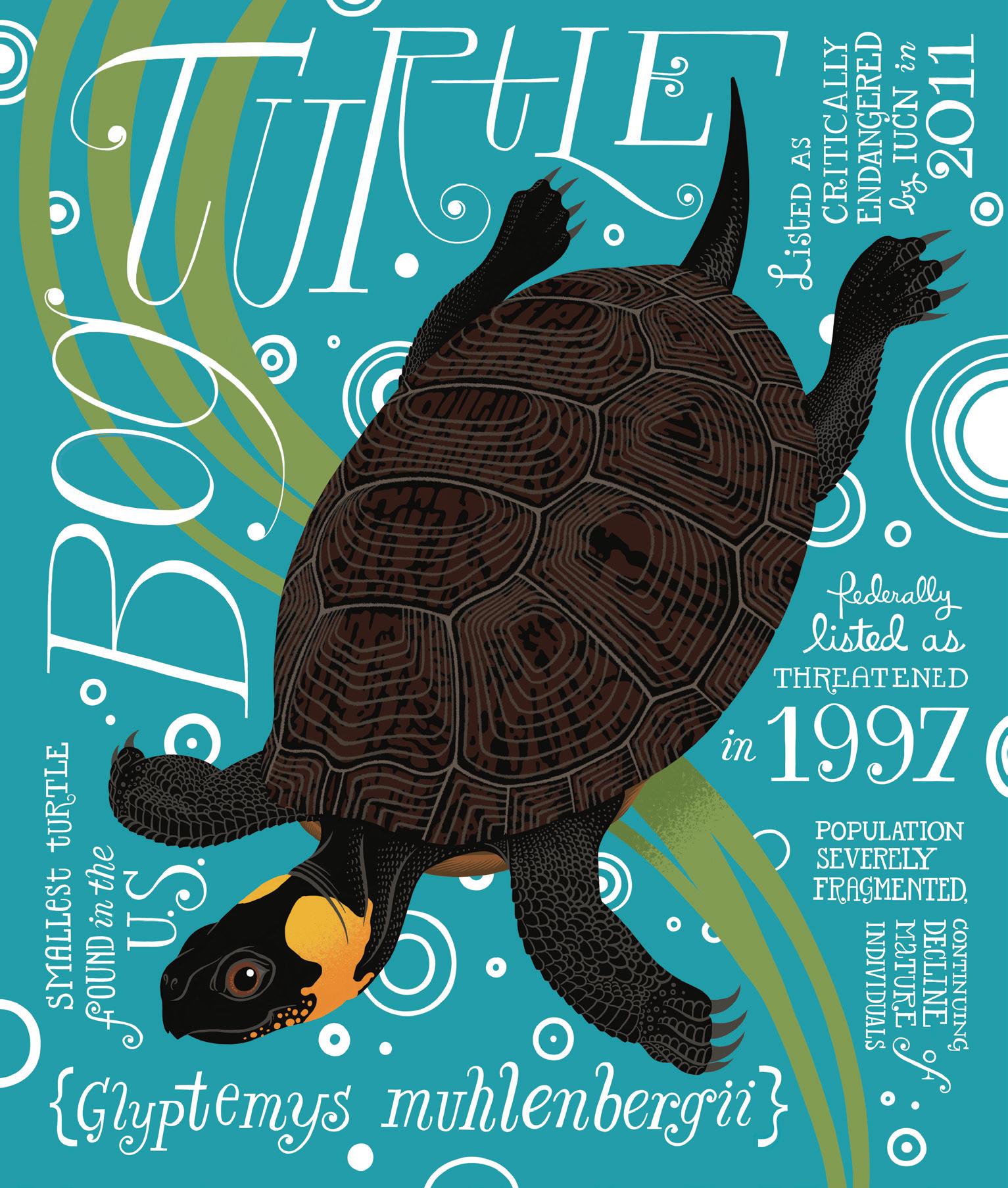

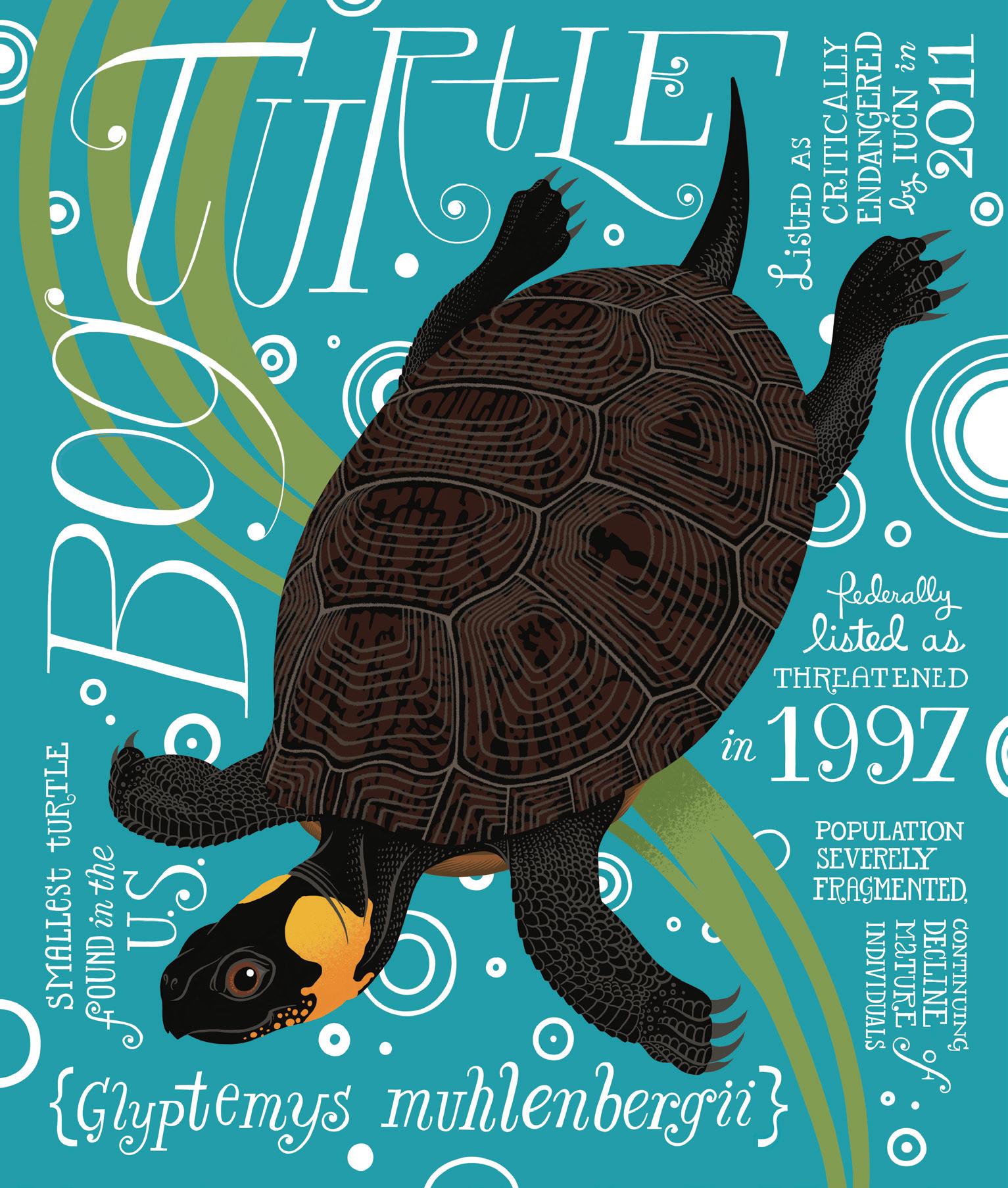

BOG TURTLE

Glyptemys muhlenbergii

Smallest turtle found in the US.

Population severely fragmented, continuing decline of mature individuals.

Federally listed as threatened in 1997.

Listed as critically endangered by IUCN in 2011.

94

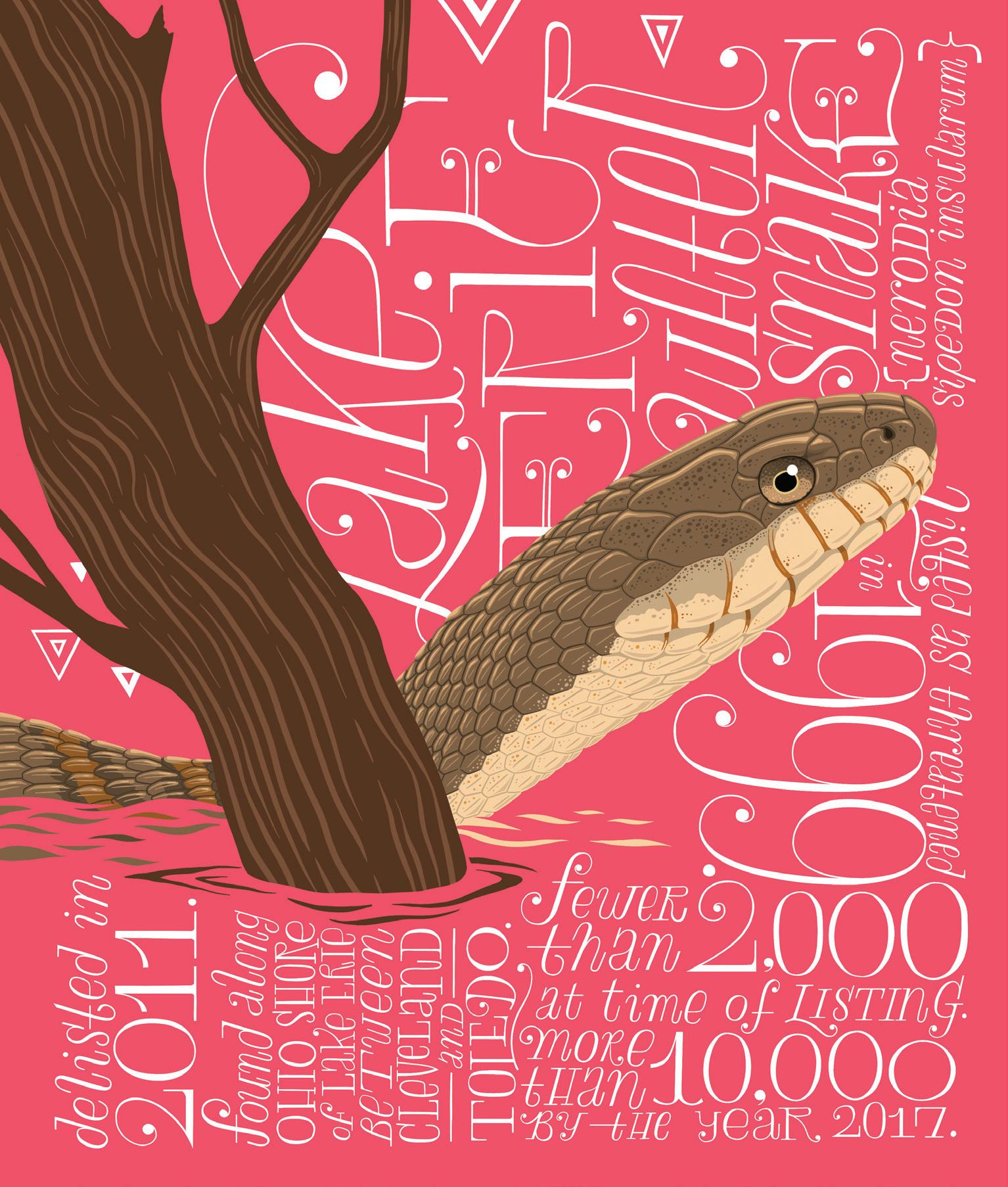

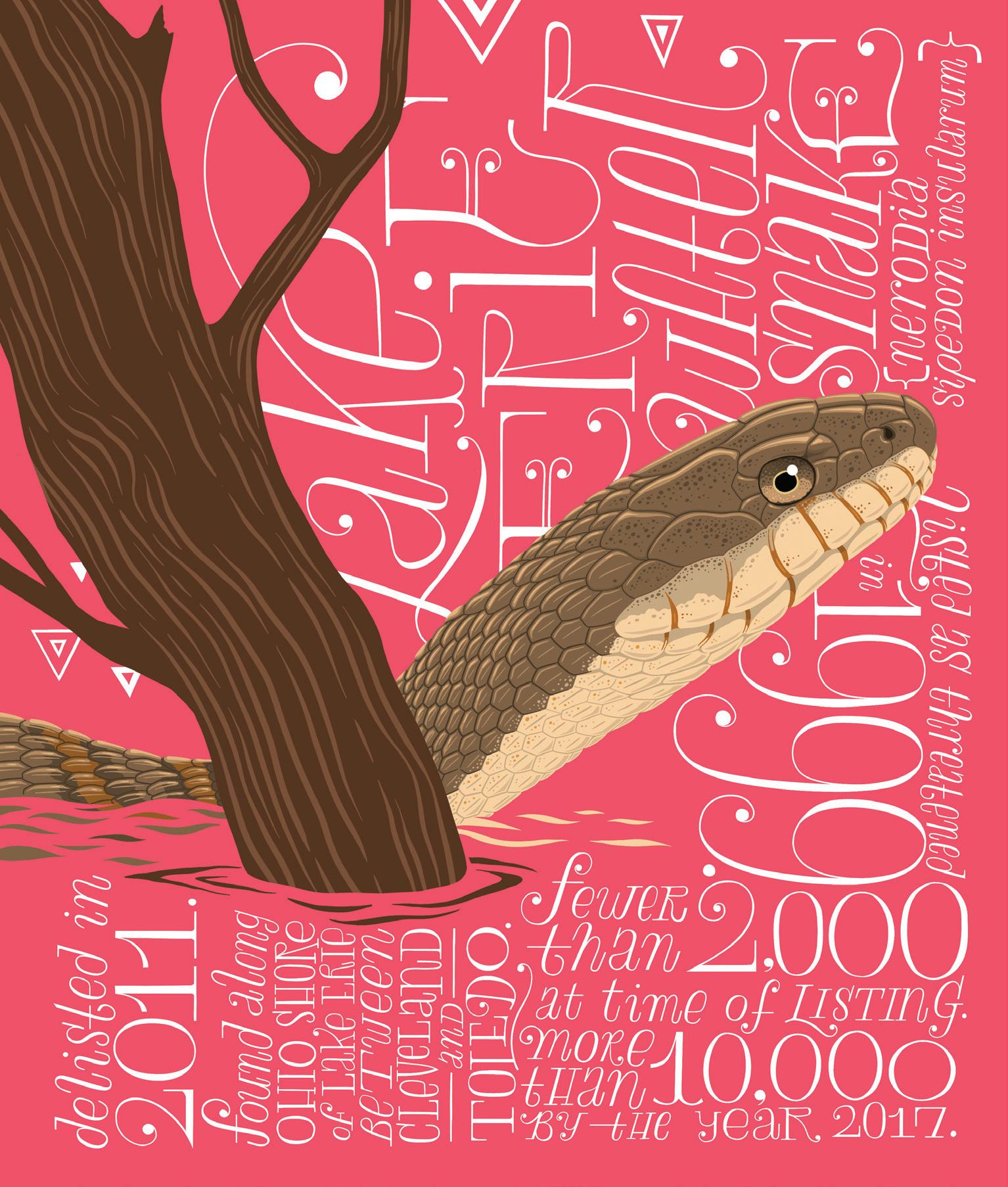

LAKE ERIE WATER SNAKE

Nerodia sipedon insularum

Found along the Ohio shore of Lake Erie between Cleveland and Toledo.

Fewer than 2,000 at time of listing. More than 10,000 by the year 2017.

Listed as threatened in 1999.

Delisted in 2011.

96

(previous page)

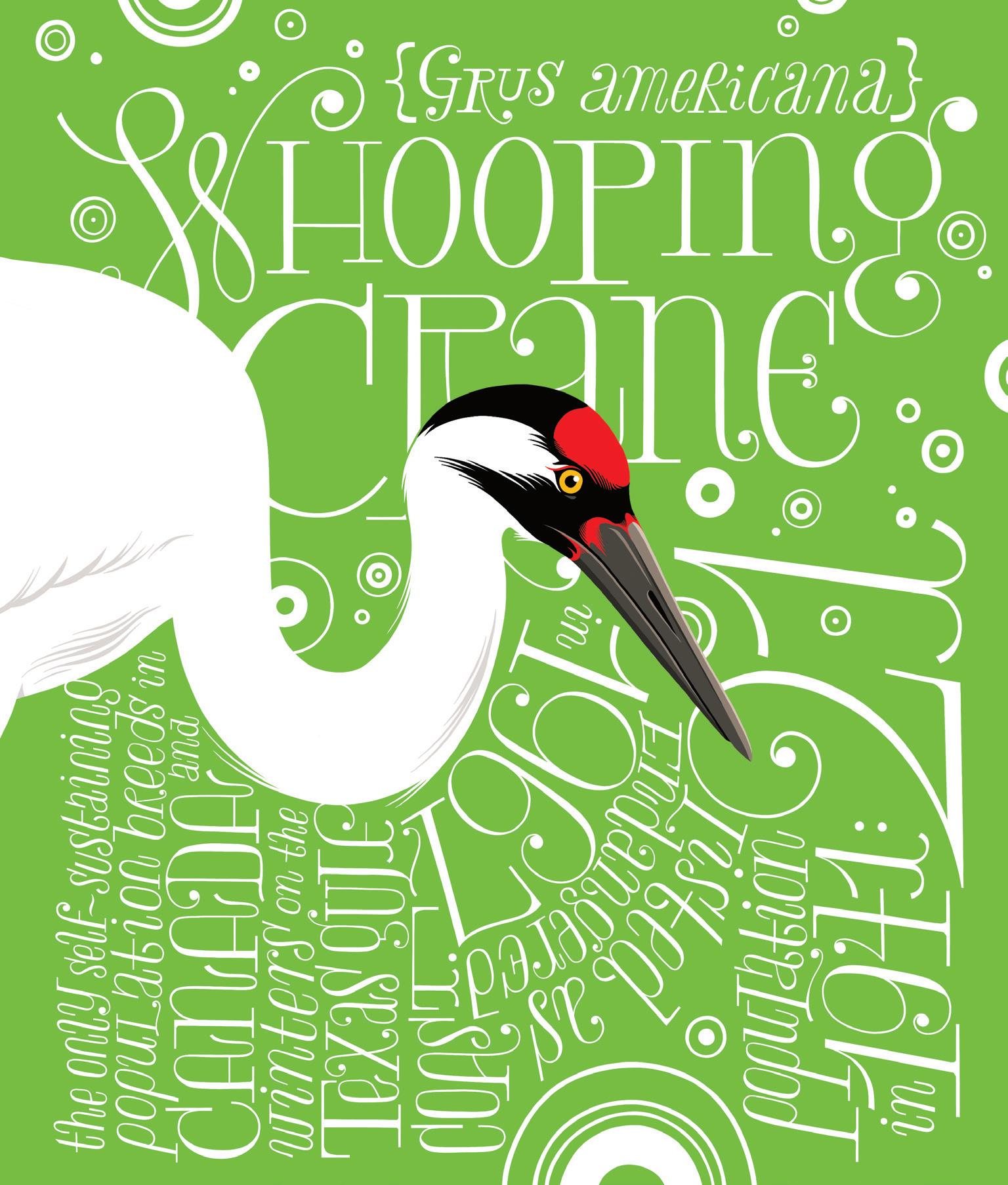

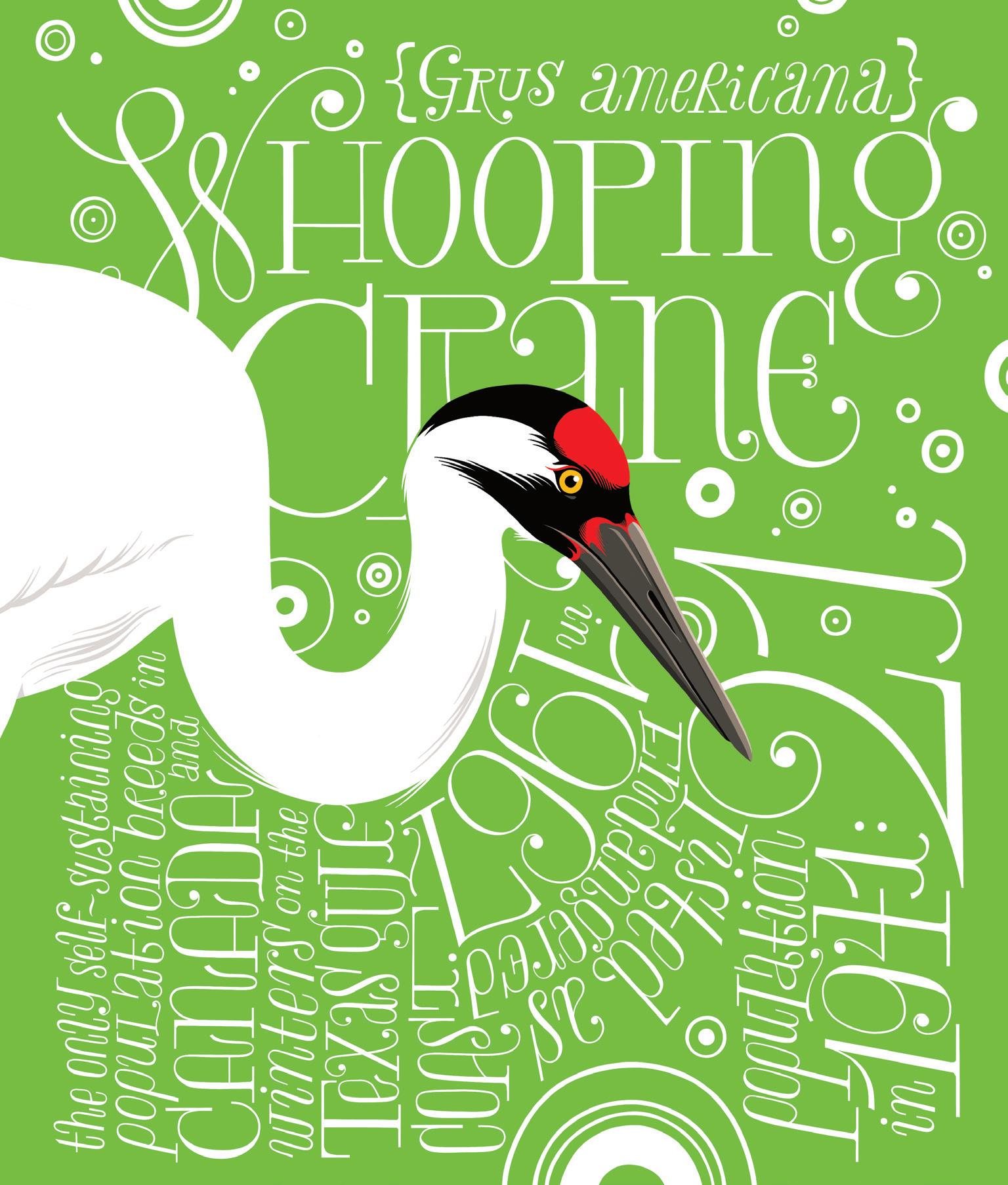

WHOOPING CRANE

Grus americana

The only self-sustaining population breeds in Canada and winters on the Texas Gulf Coast.

Destruction of habitat and overhunting were the main causes of the whooping crane’s decline from the estimated precolonial population of 10,000.

Population in 1941: 21 wild and 2 captive.

Total wild population in 2010: 383.

Wild and captive population in 2010: 535.

Listed as endangered in 1967.

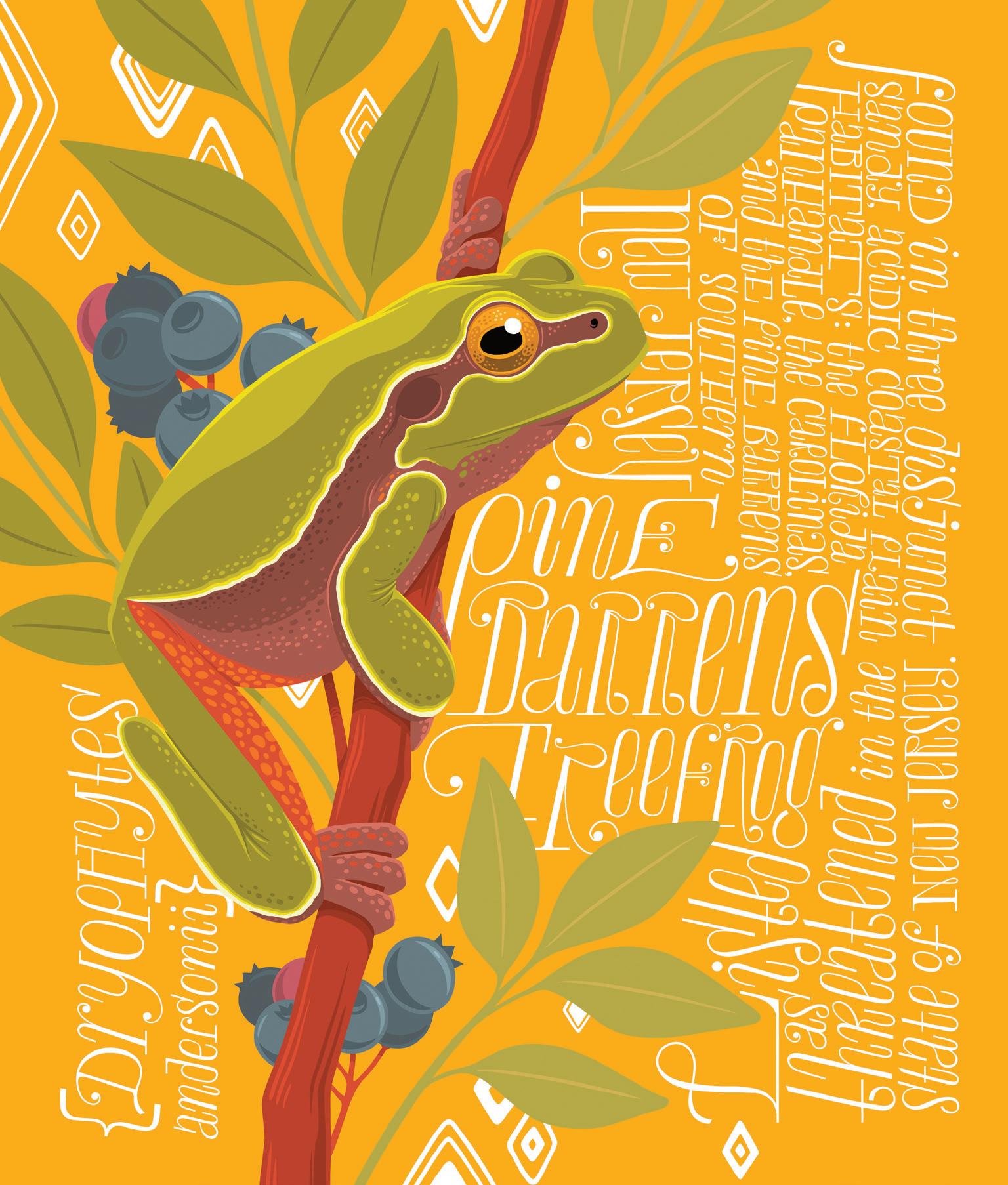

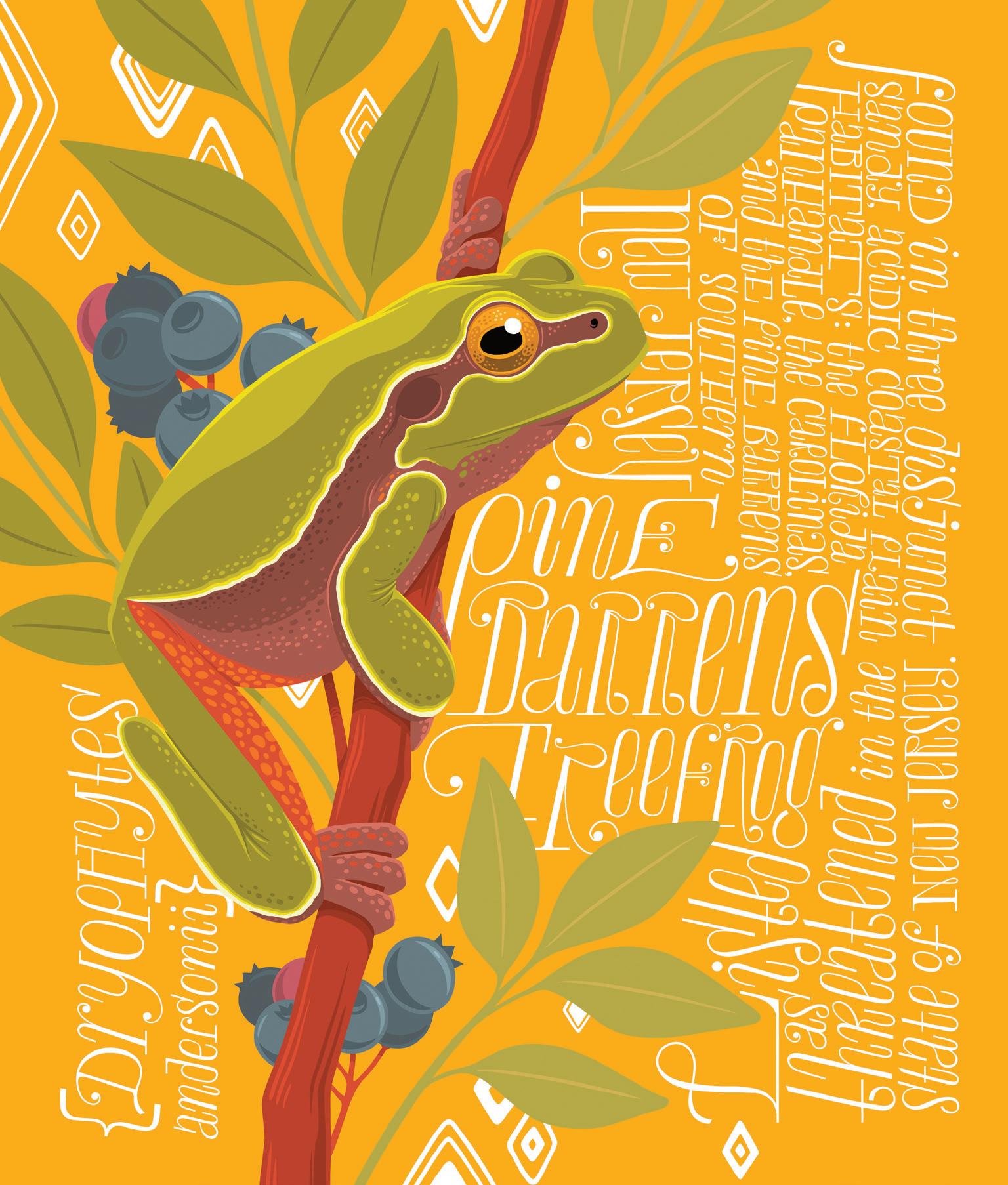

PINE BARRENS TREEFROG

Dryophytes andersonii

Found in three disjunct sandy, acidic coastal plain habitats: the Florida Panhandle, the Carolinas, and the Pine Barrens of southern New Jersey.

Once listed as federally endangered by the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. Delisted in 1983 when other disjunct populations in the Florida panhandle were found.

Listed as endangered in New Jersey in 1979. Downlisted to state-threatened in 2003.

100

(previous page)

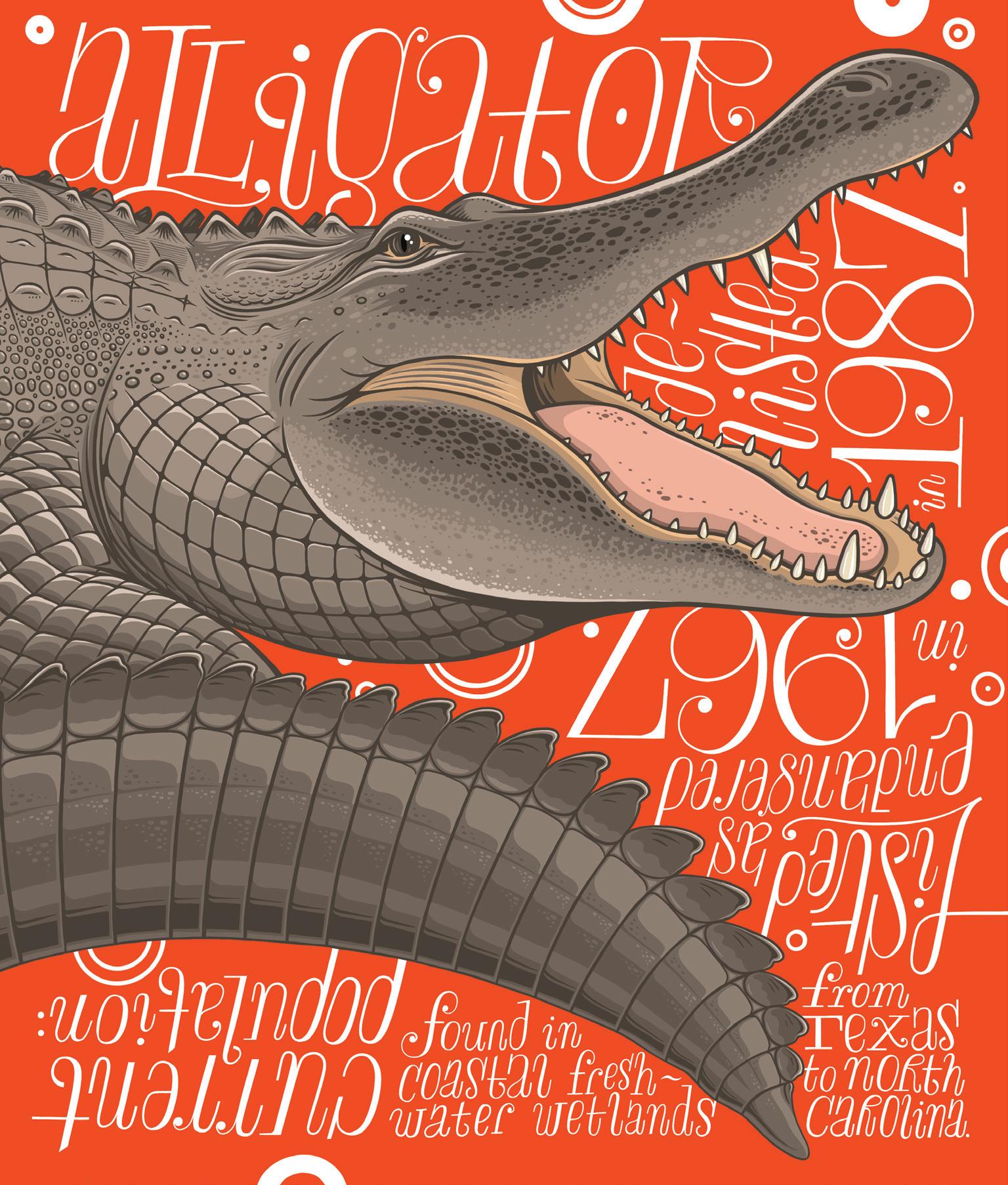

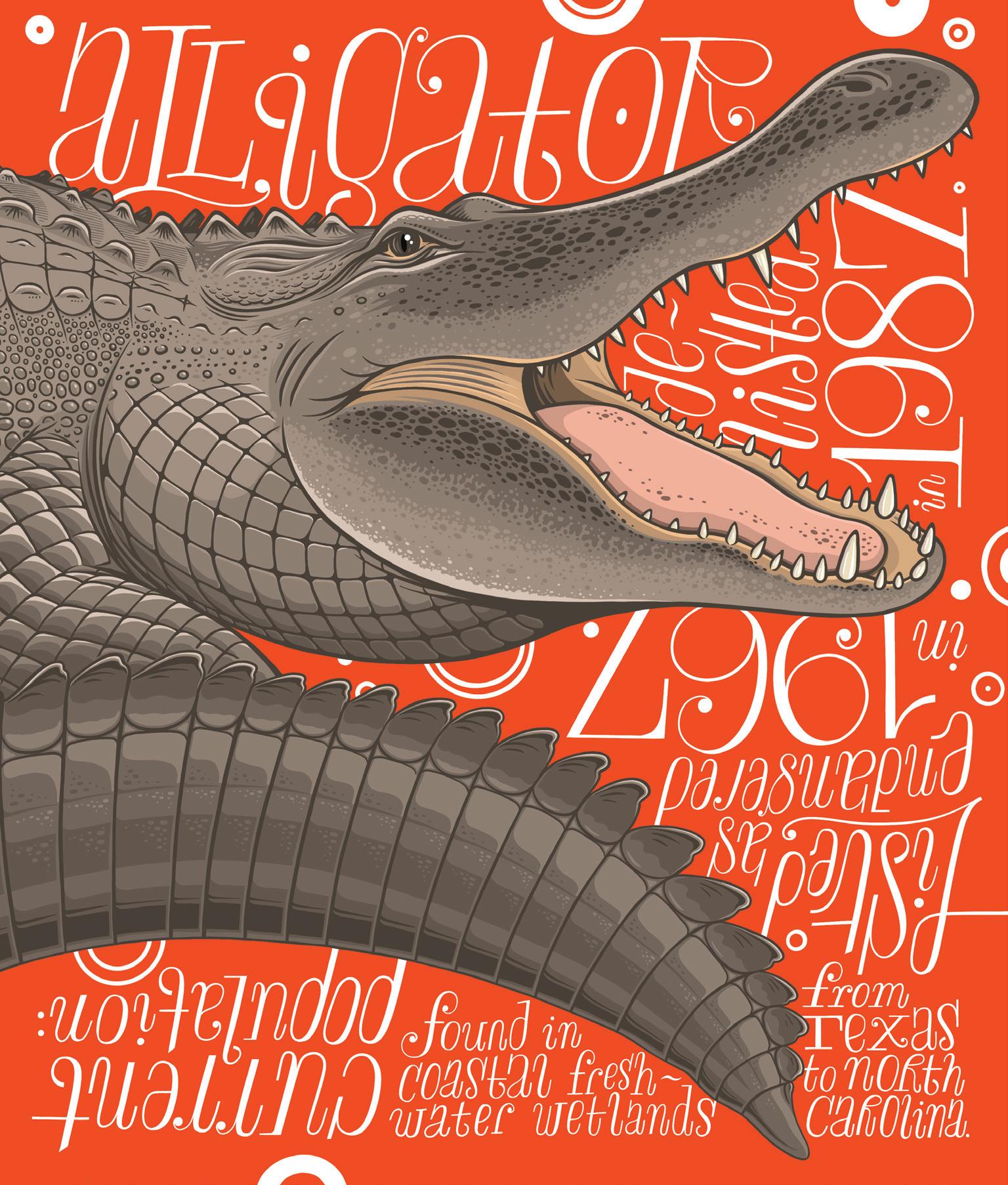

AMERICAN ALLIGATOR

Alligator mississippiensis

Found in coastal freshwater wetlands from Texas to North Carolina.

Current population: 5 million.

Listed as endangered in 1967.

Delisted in 1987.

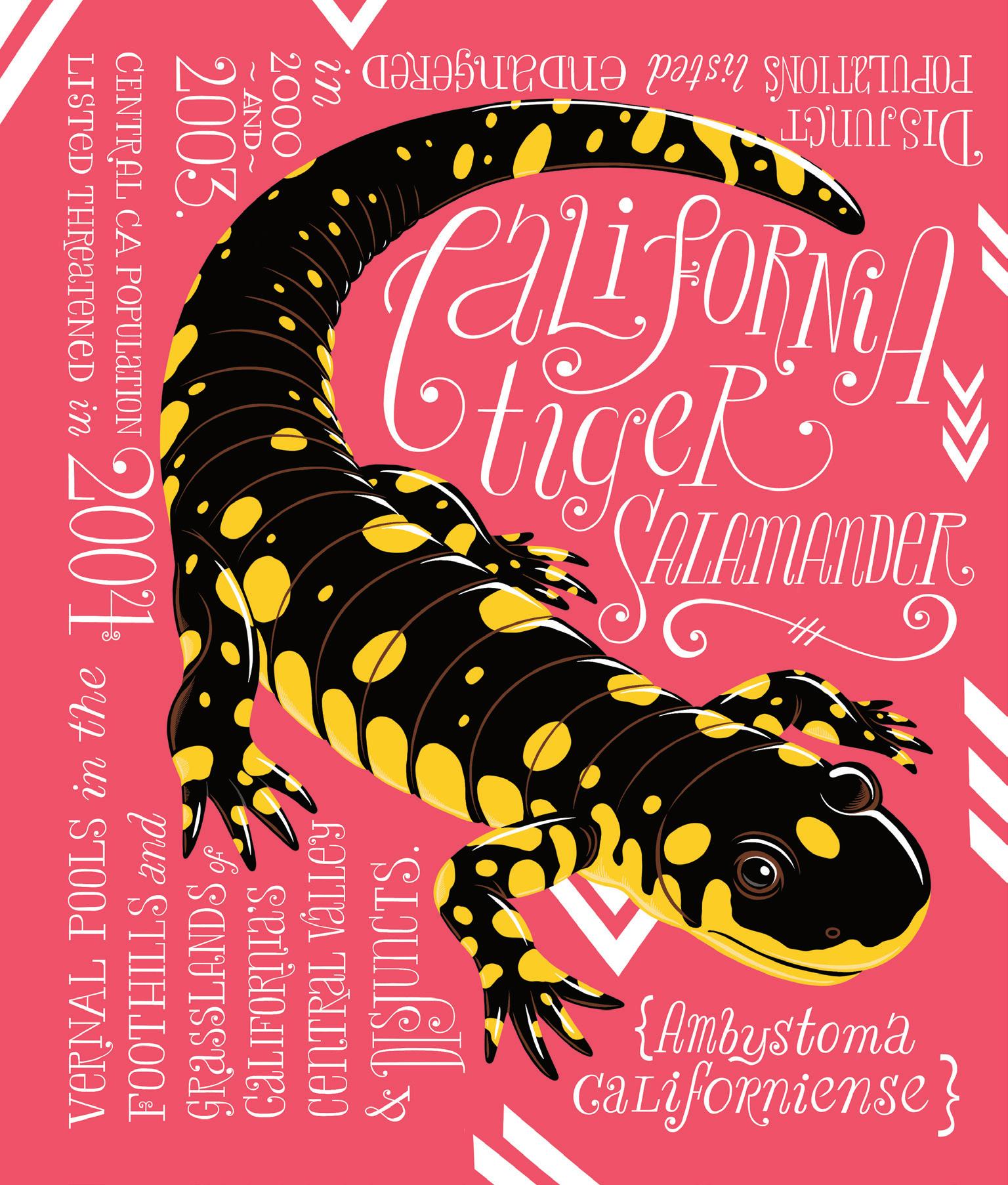

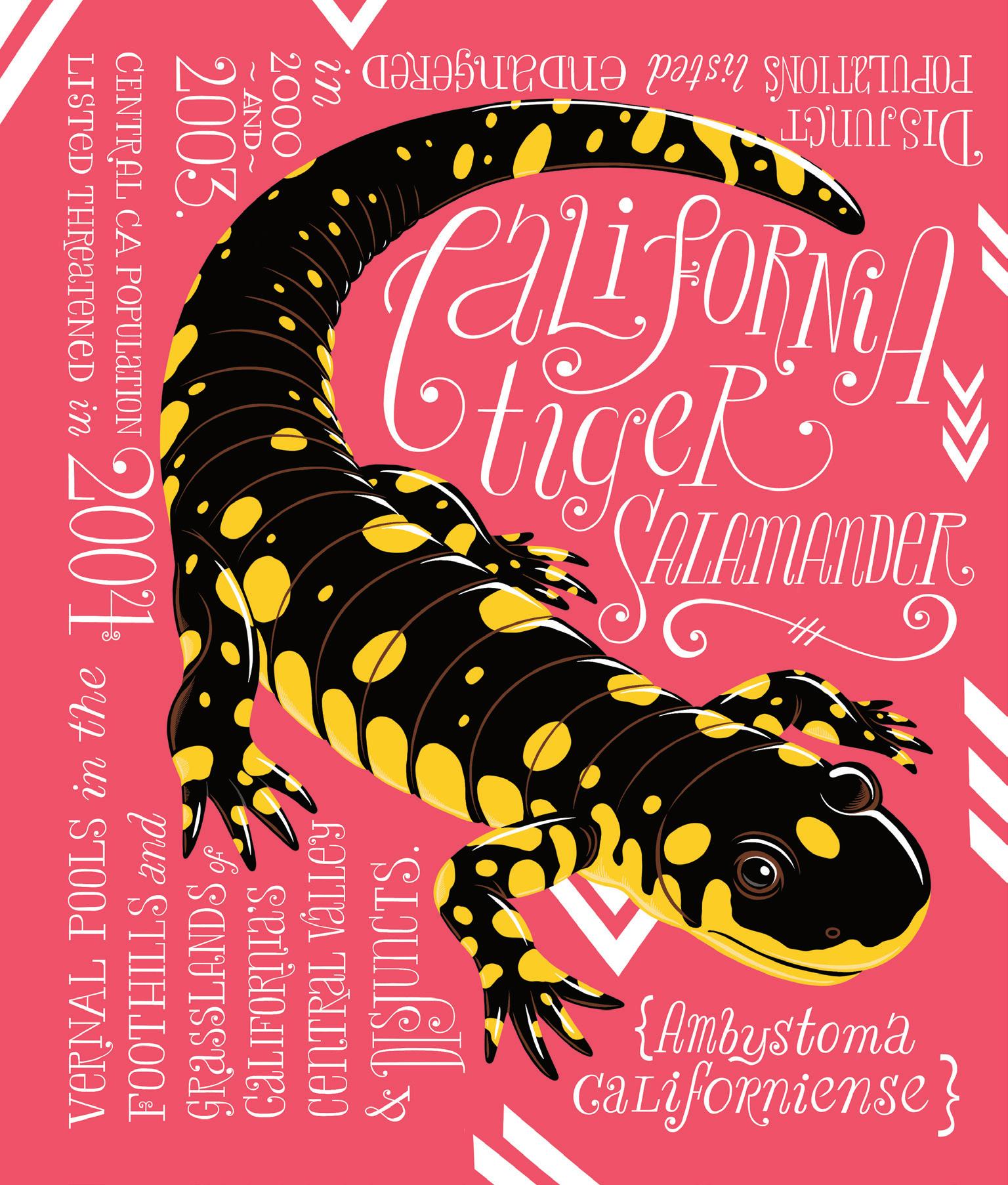

CALIFORNIA TIGER SALAMANDER

Ambystoma californiense

Found in vernal pools in the foothills and grasslands of California’s central valley and disjuncts.

Disjunct populations listed as endangered in 2000 and 2003.

Central California population listed as threatened in 2004.

104

(previous page)

IVORY-BILLED WOODPECKER

Campephilus principalis

Proposed delisting due to extinction in 2021.

Status under review: recent evidence suggests its possible survival.

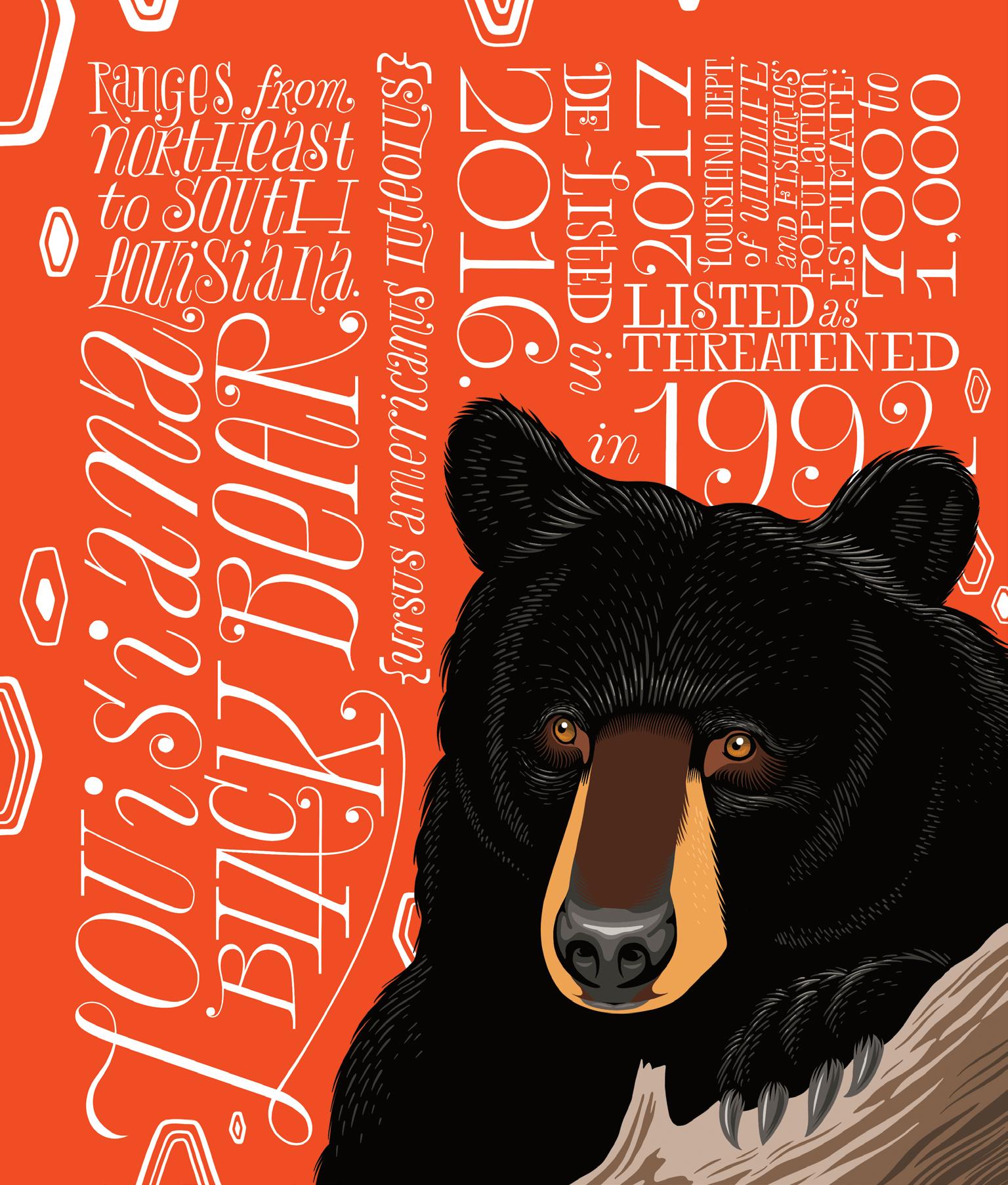

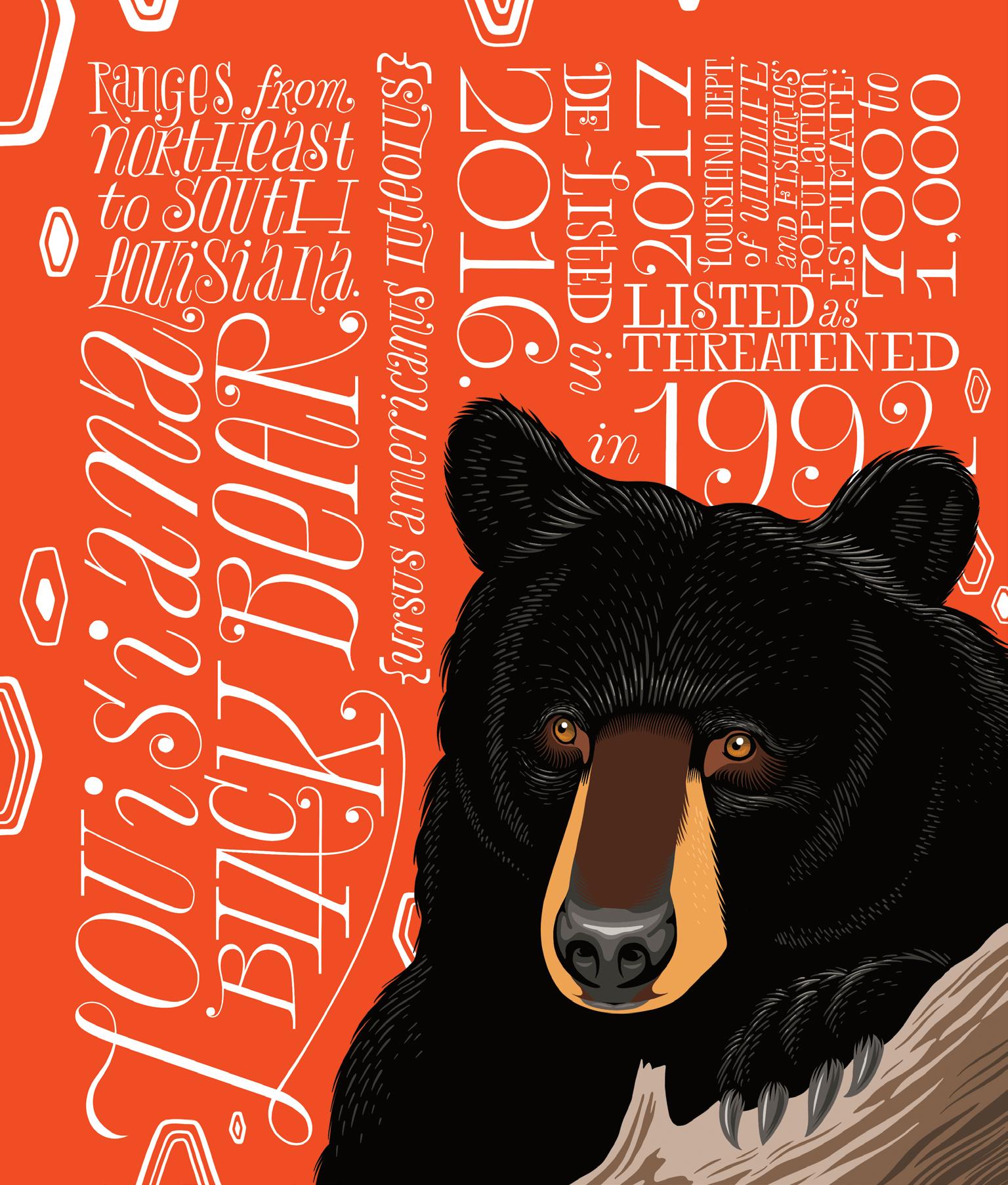

LOUISIANA BLACK BEAR

Ursus americanus luteolus

Ranges from northeastern to southern Louisiana.

2017 Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries population estimate: 700 to 1,000.

Listed as threatened in 1992.

Delisted in 2016.

108

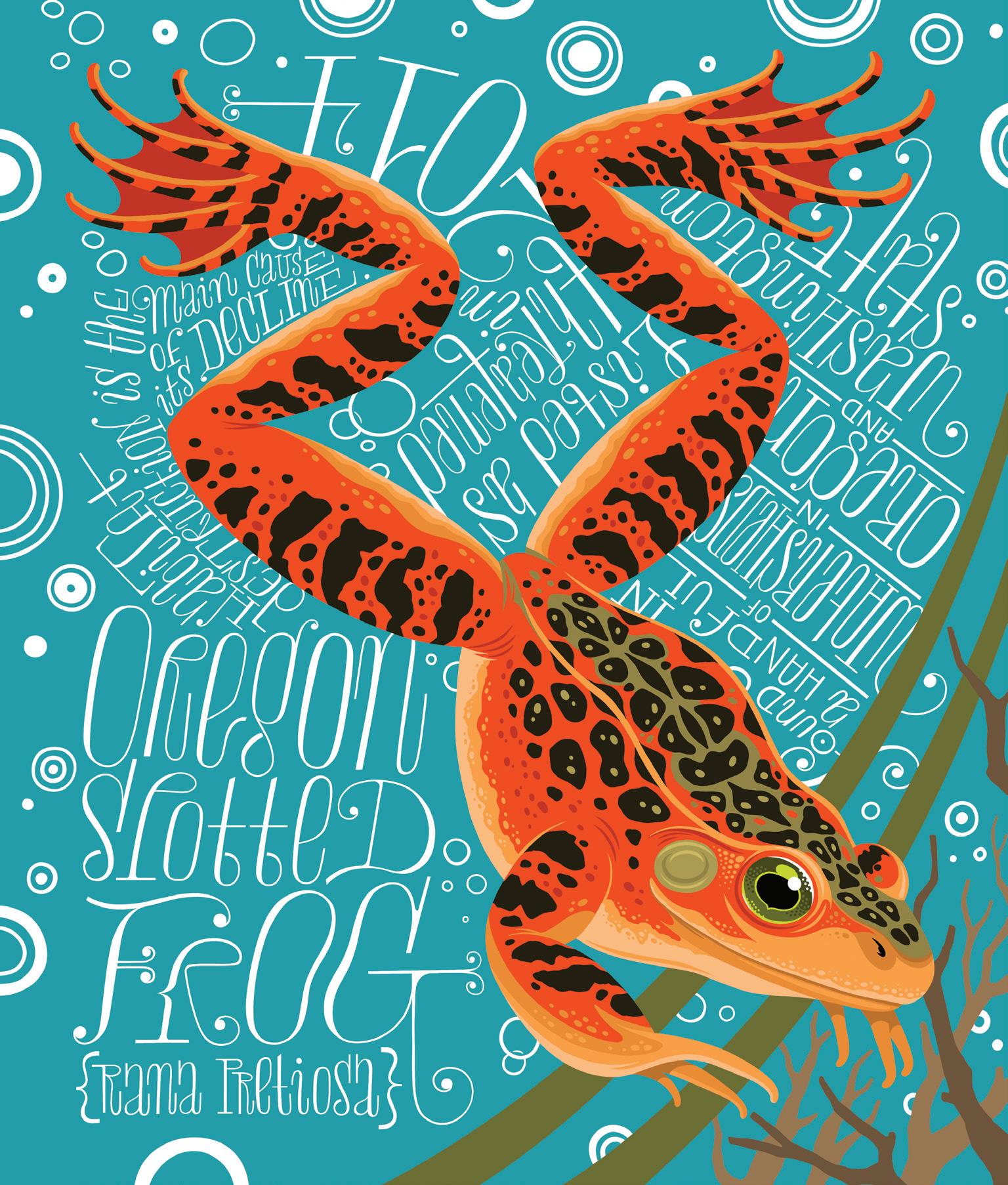

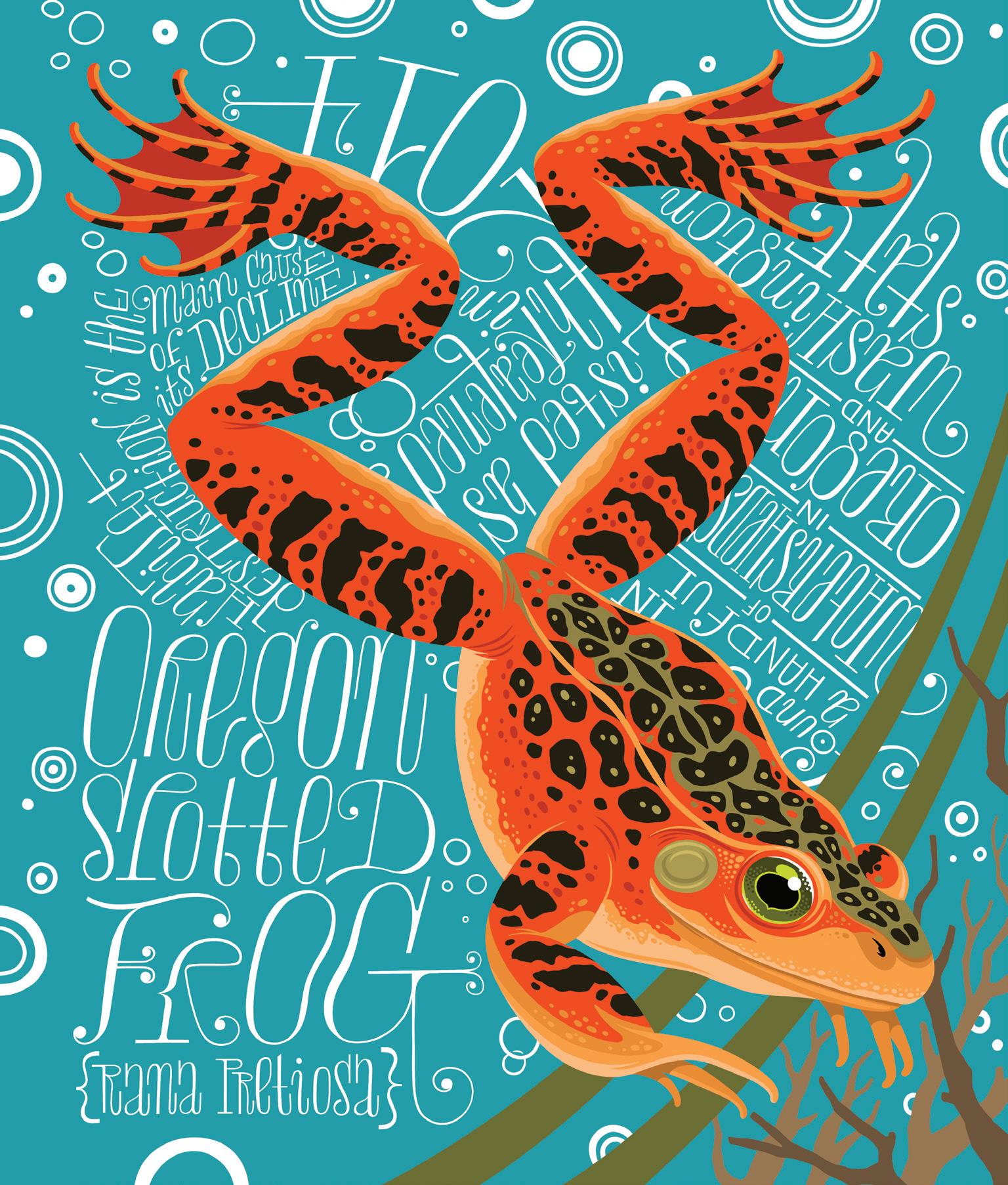

OREGON SPOTTED FROG

Rana pretiosa

Found in a handful of watersheds in Oregon and Washington State.

Habitat destruction is the main cause of its decline.

Listed as threatened in 2014.

110

INTERIOR LEAST TERN

Sternula antillarum athalassos

Smallest species of North American terns. Nests along the rivers of the Great Plains.

River dredging has reduced the sand bars they need for breeding.

Population when first listed: 2,000.

Current population: 18,000.

Listed as endangered in 1985.

112

OREGON CHUB

Oregonichthys crameri

Endemic to the Willamette River drainage in Oregon.

Estimated lowest population: fewer than 1,000.

Estimated population at time of delisting: over 140,000.

Listed as endangered in 1993.

Delisted in 2015.

114

VENUS FLYTRAP

Dionaea muscipula

Native to the coastal plain of northeastern South Carolina and southeastern North Carolina.

Threats include habitat destruction and poaching.

Its conservation status is currently under review.

116

CONCHO WATER SNAKE

Nerodia paucimaculata

Endemic to the Concho and Colorado River systems in west-central Texas.

Listed as threatened in 1986.

Delisted in 2011.

(following page)

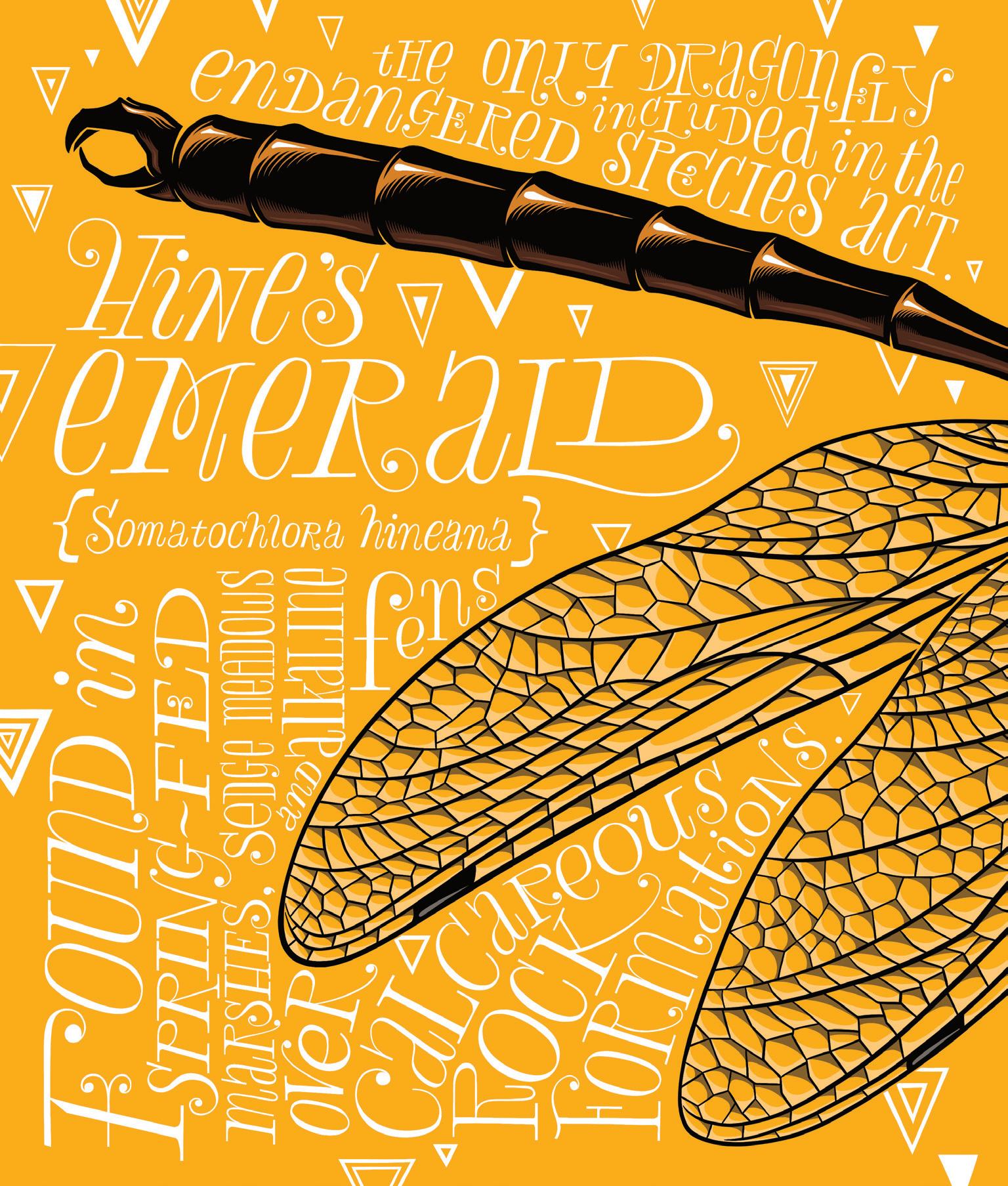

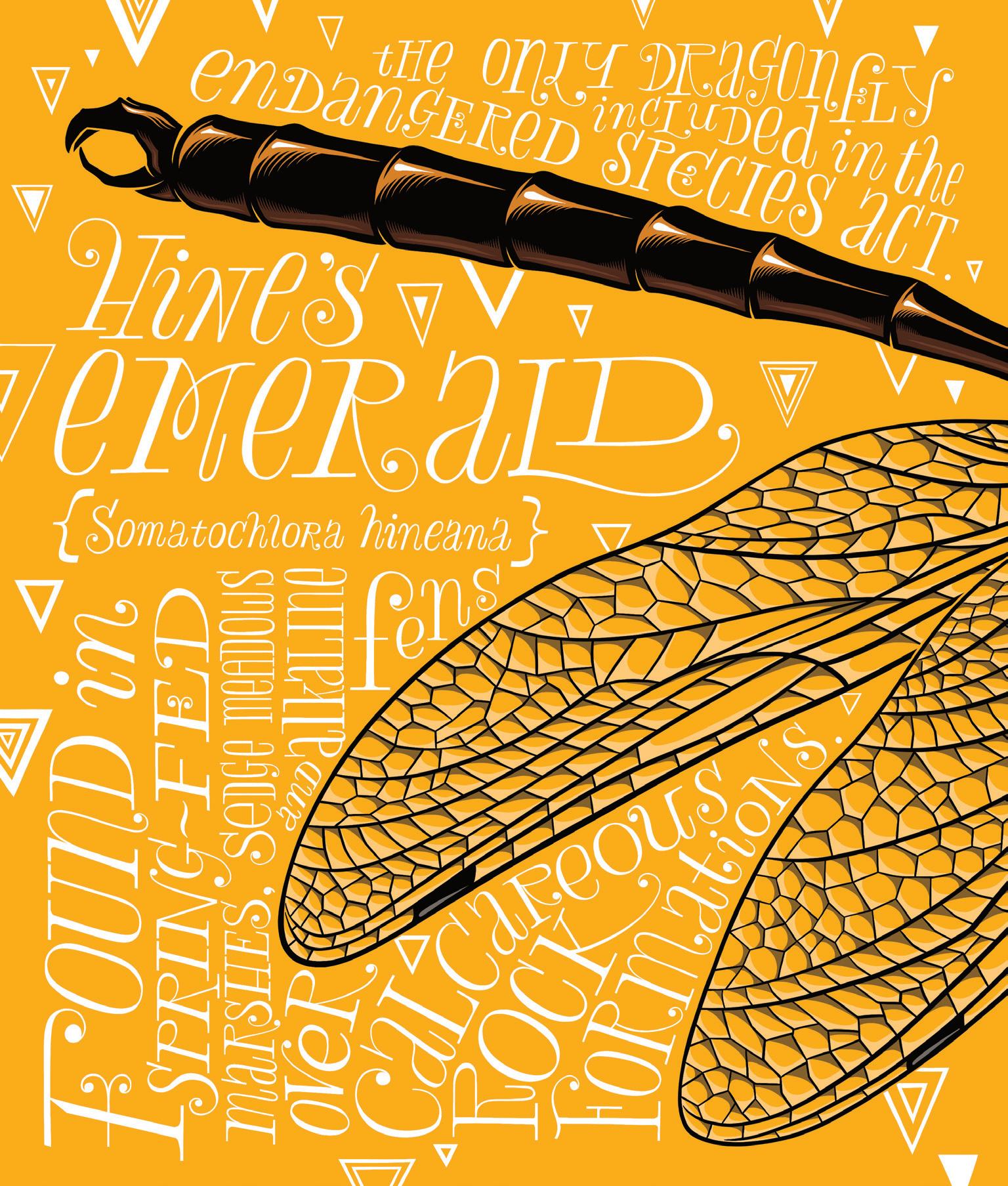

HINE’S EMERALD DRAGONFLY

Somatochlora hineana

The only dragonfly included in the Endangered Species Act.

Range: remnant habitats in Illinois, Michigan, Missouri, and Wisconsin.

Found in spring-fed marshes, sedge meadows, and alkaline fens over calcareous rock formations.

IUCN global population estimate: over 30,000 individuals.

Listed as endangered in 1995.

118

TULOTOMA SNAIL

Tulotoma magnifica

Found only in the Coosa-Alabama River system in Alabama.

The number of colonies within the watershed were found to be greater than during the time of its 1991 listing.

Listed as endangered in 1991.

Reclassified as threatened in 2011.

122

TEXAS BLIND SALAMANDER

Eurycea rathbuni

Found only in the San Marcos pool of the Edwards Aquifer in south-central Texas.

Listed as endangered in 1967.

124

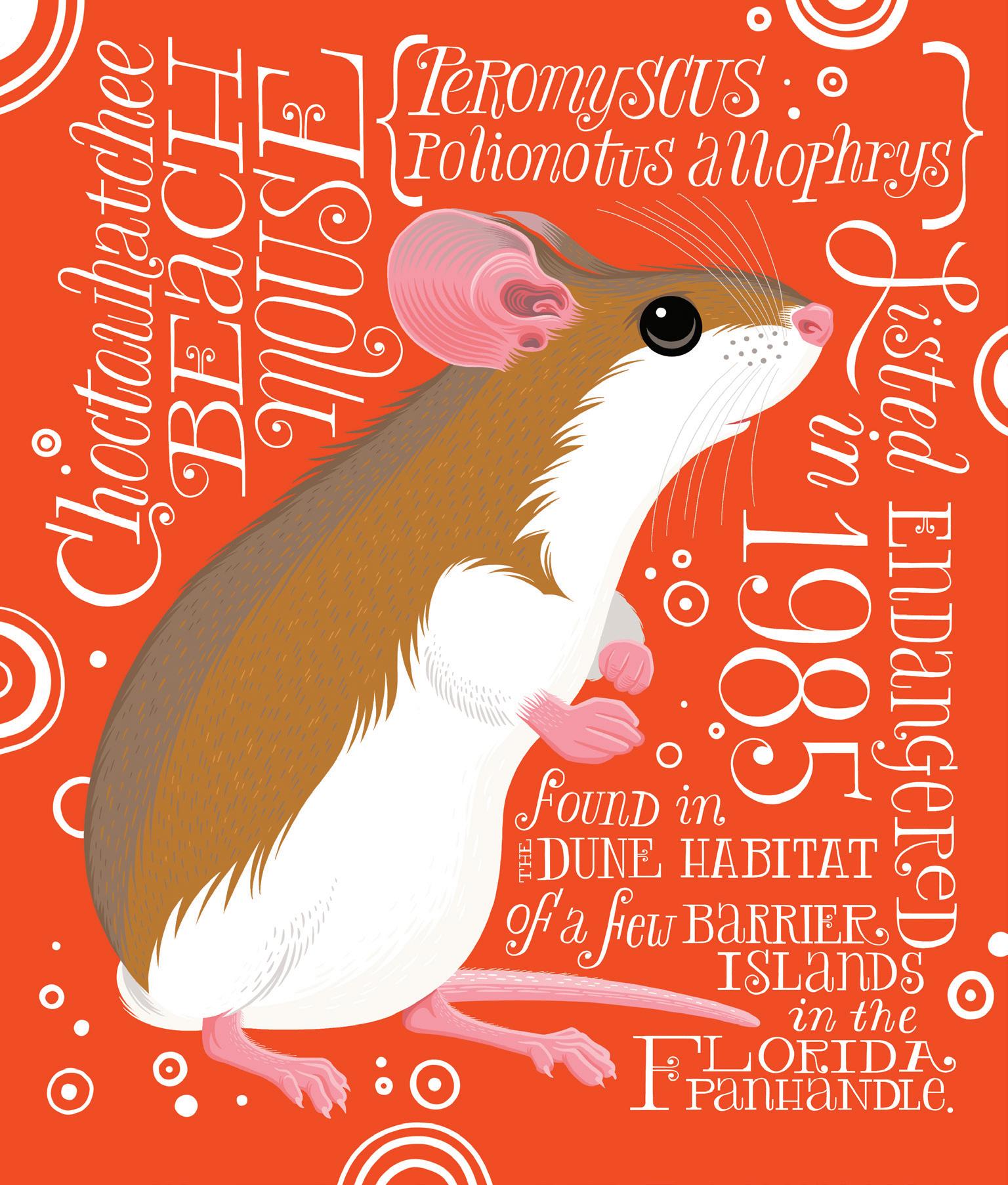

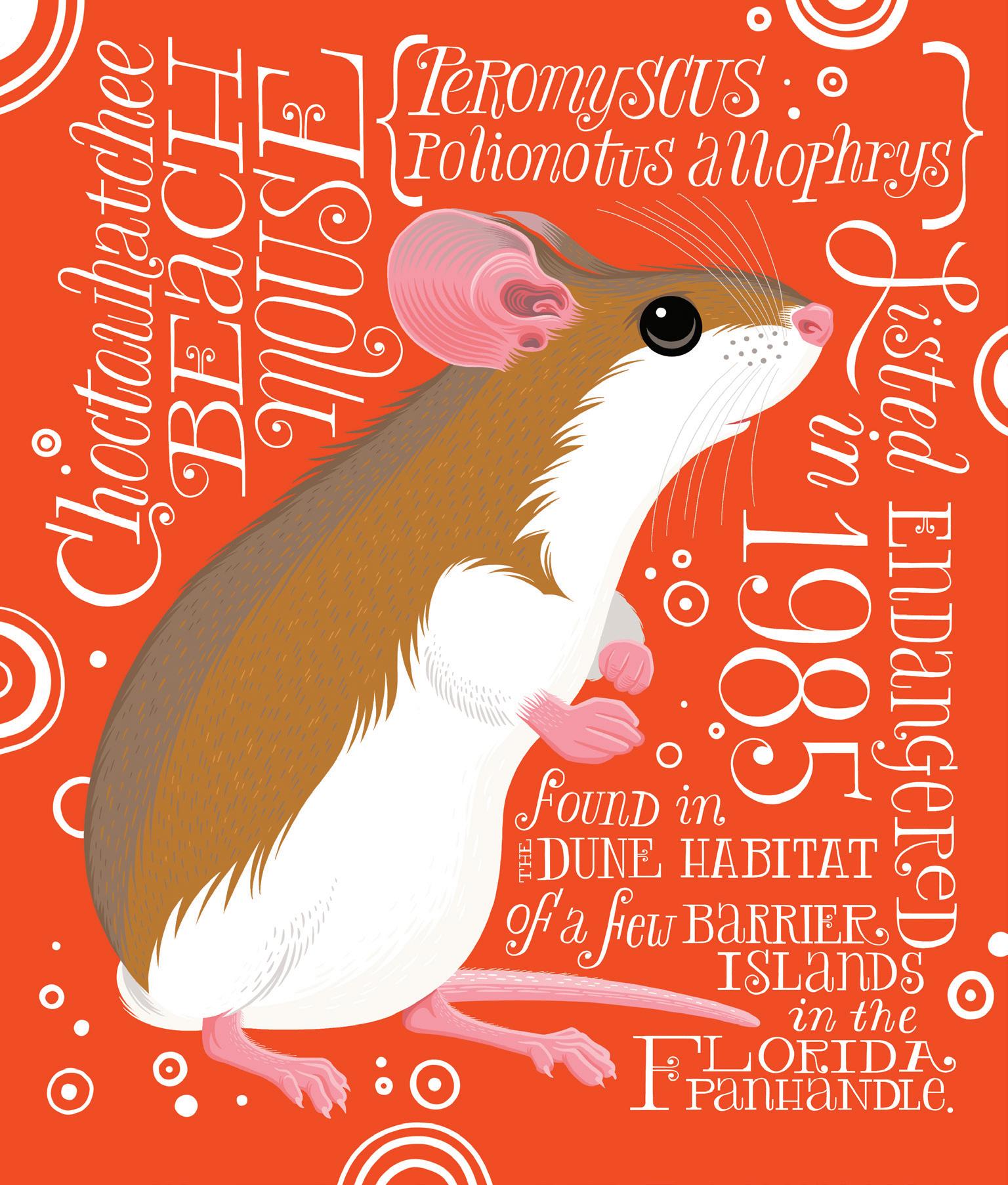

CHOCTAWHATCHEE BEACH MOUSE

Peromyscus polionotus allophrys

Found in the dune habitat of a few barrier islands in the Florida Panhandle.

Listed endangered in 1985.

126

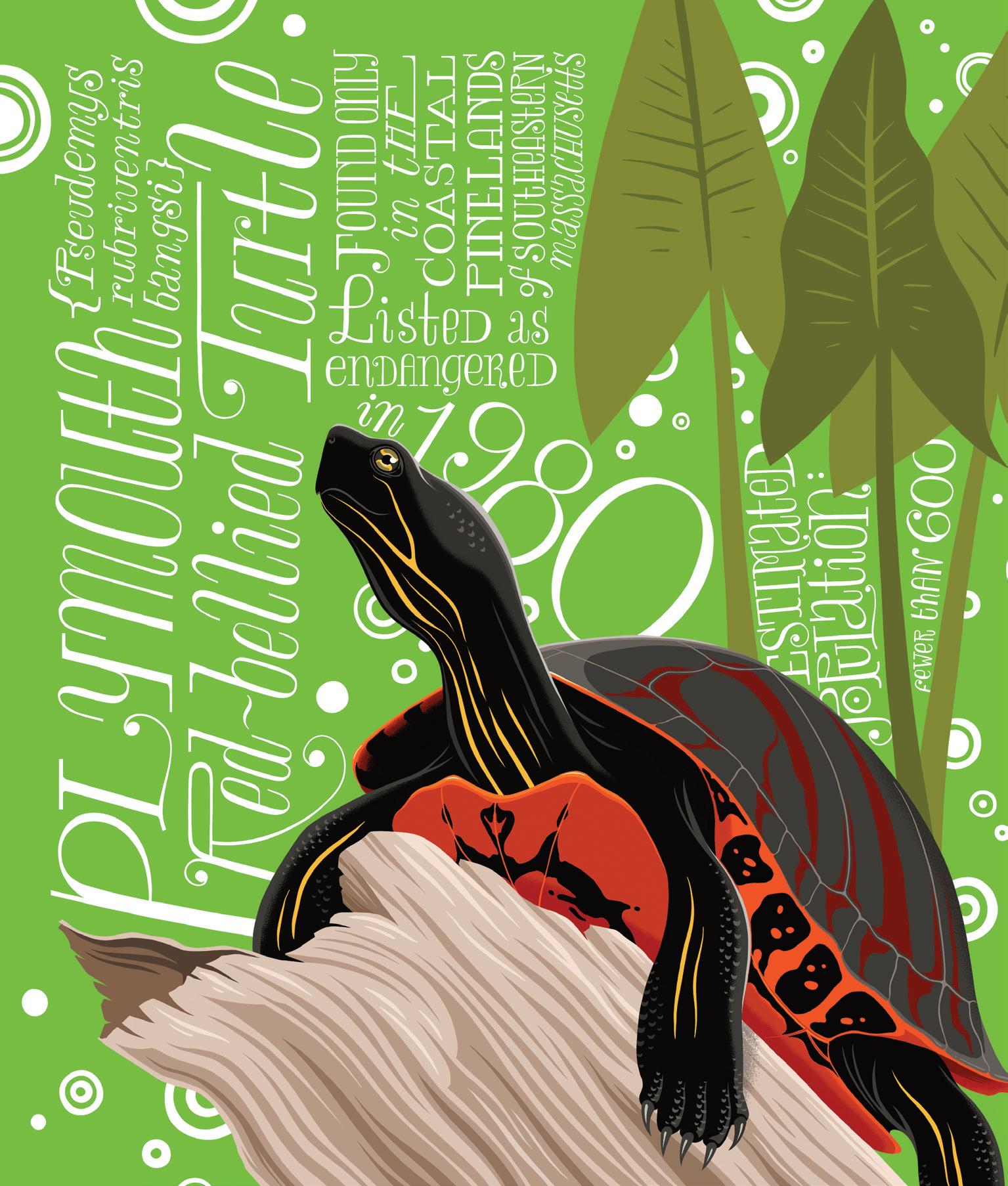

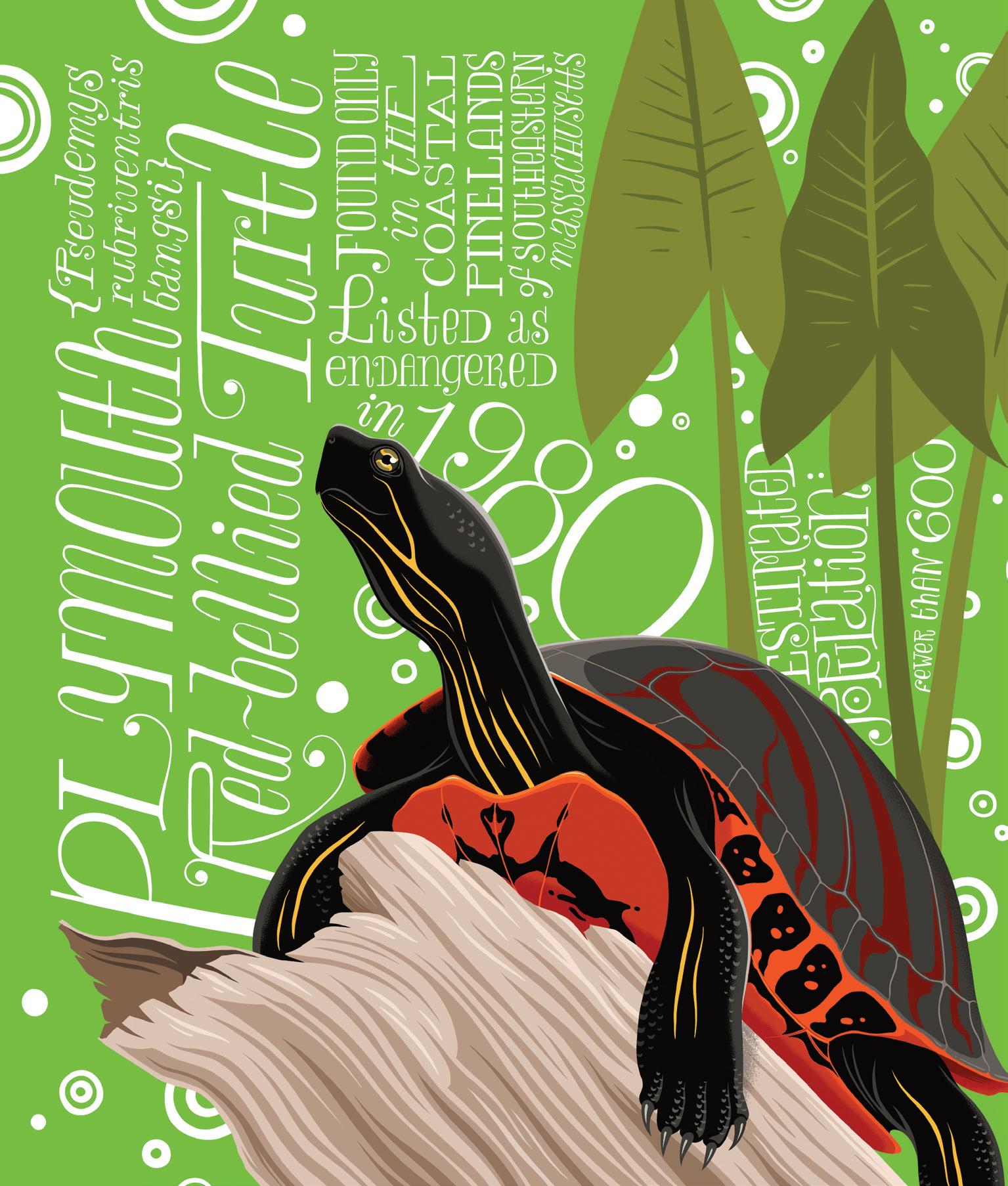

PLYMOUTH RED-BELLIED TURTLE

Pseudemys rubriventris bangsi

Found only in the coastal pinelands of southeastern Massachusetts.

Estimated population: fewer than 600. Listed as endangered in 1980.

128

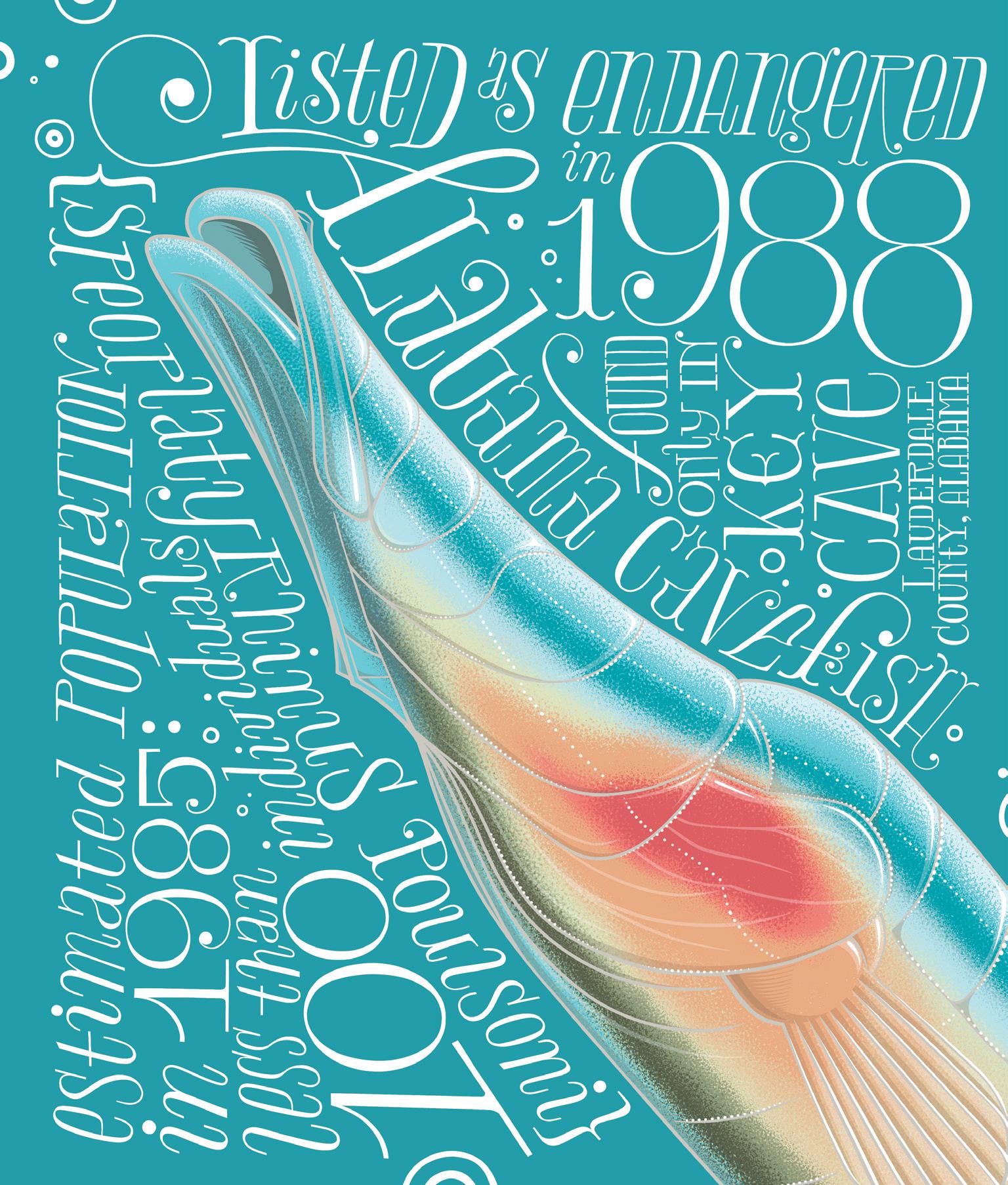

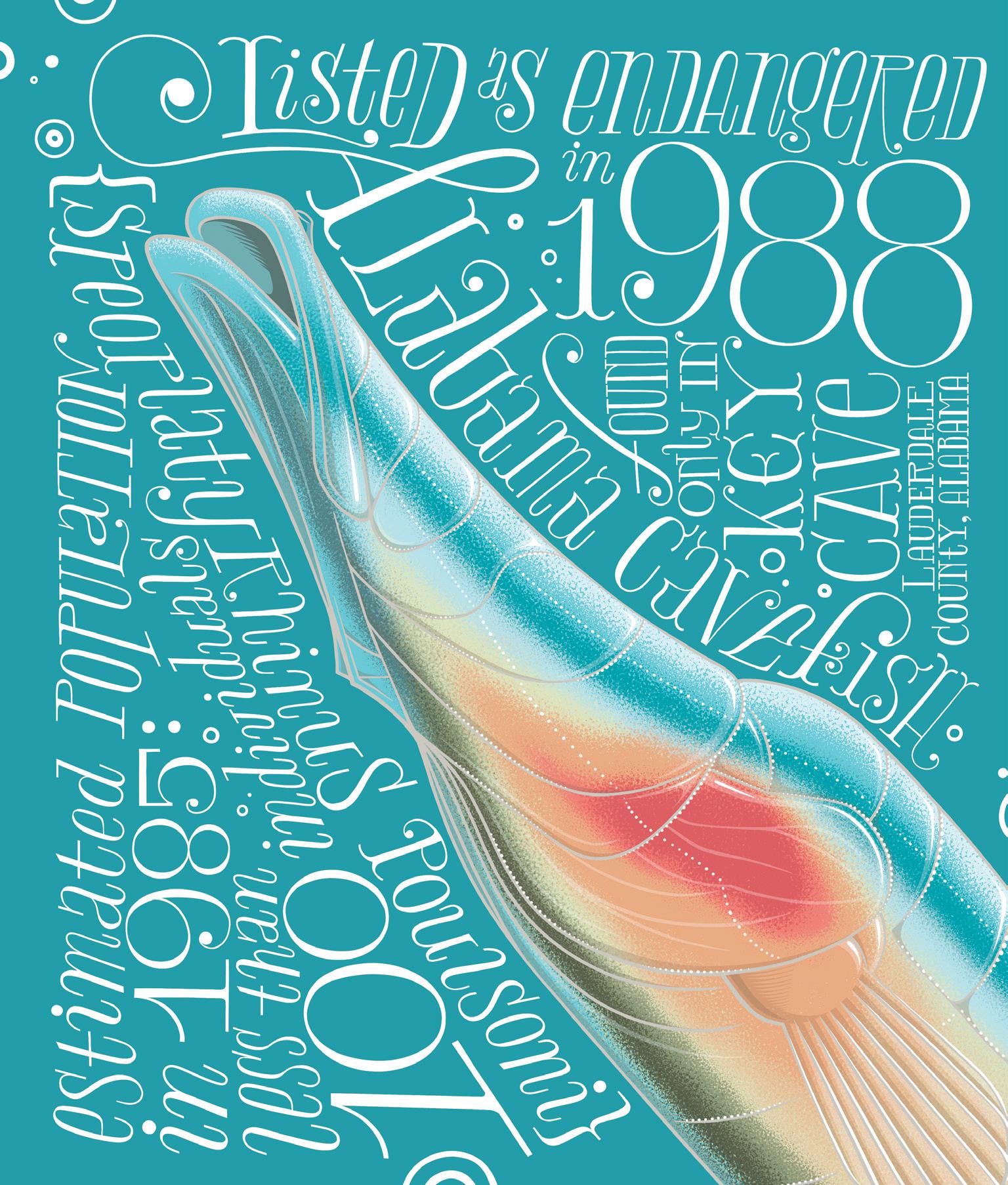

ALABAMA CAVEFISH

Speoplatyrhinus poulsoni

Found only in Key Cave, Lauderdale County, Alabama.

Estimated population in 1985: less than 100 individuals.

Listed as endangered in 1988.

130

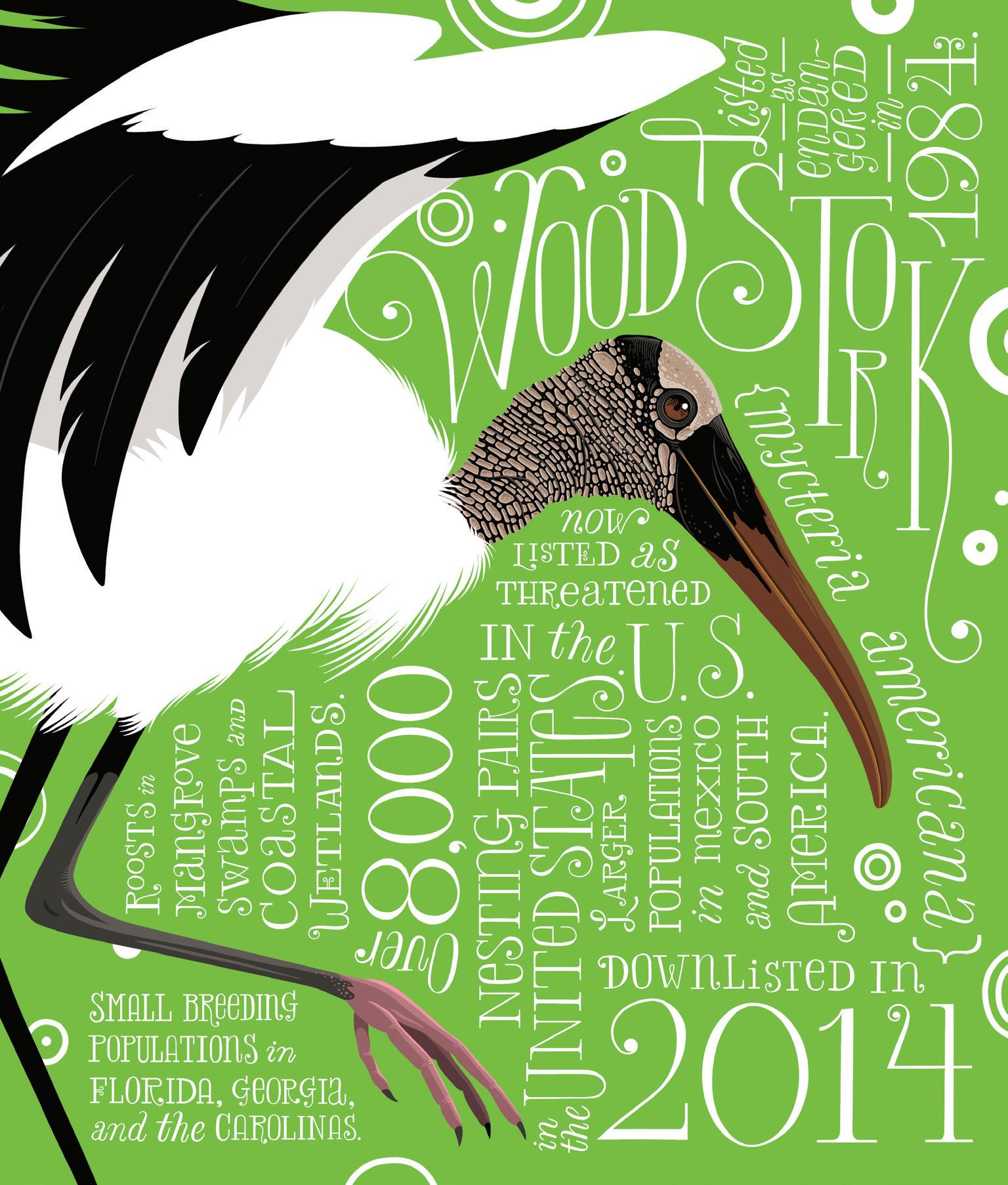

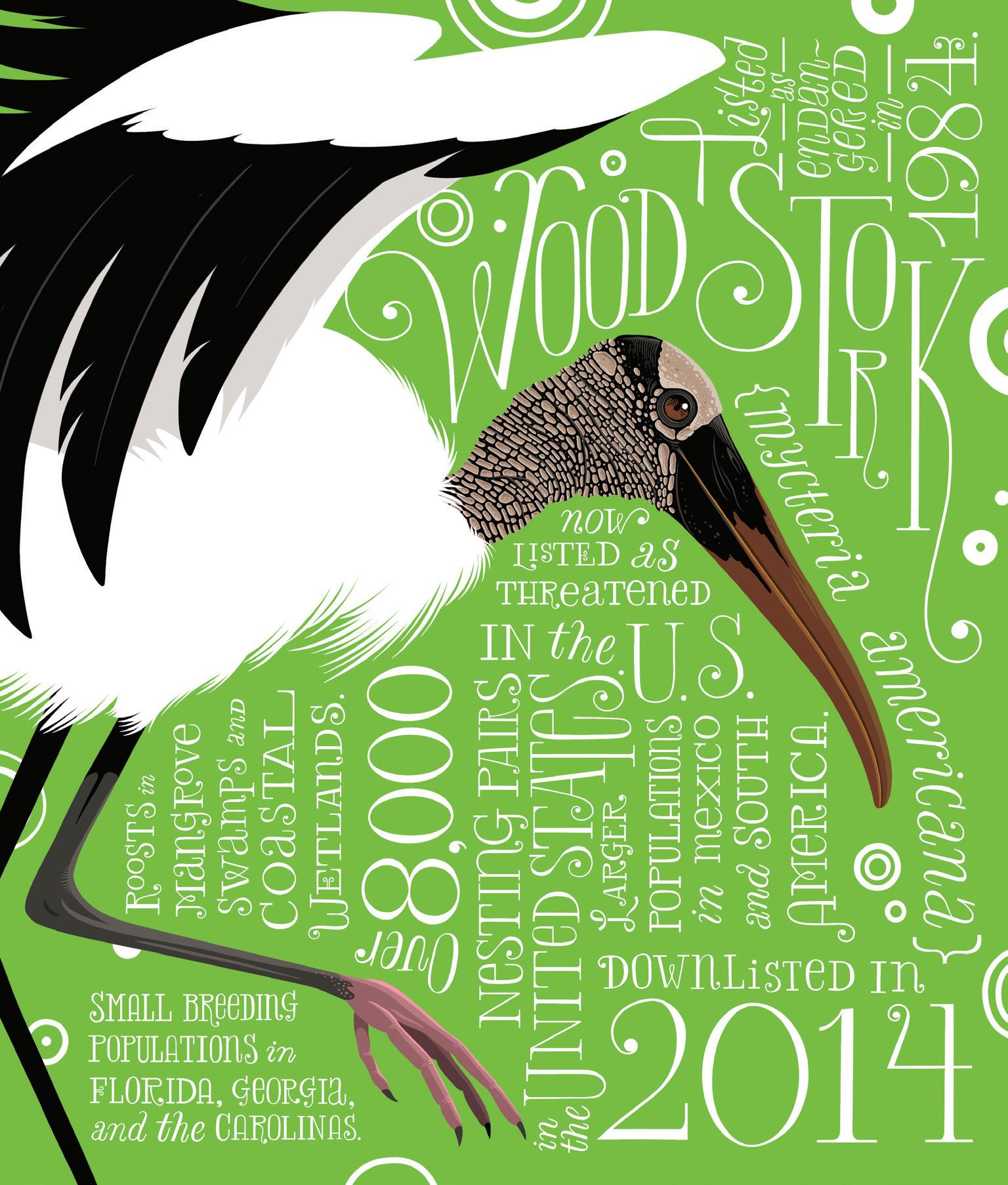

WOOD STORK

Mycteria americana

Small breeding populations in Florida, Georgia, and the Carolinas. Roosts in mangrove swamps and coastal wetlands.

Over 8,000 nesting pairs in the United States.

Larger populations in Mexico and South America.

Listed as endangered in 1984. Delisted in 2014. Now listed as threatened in the US.

132

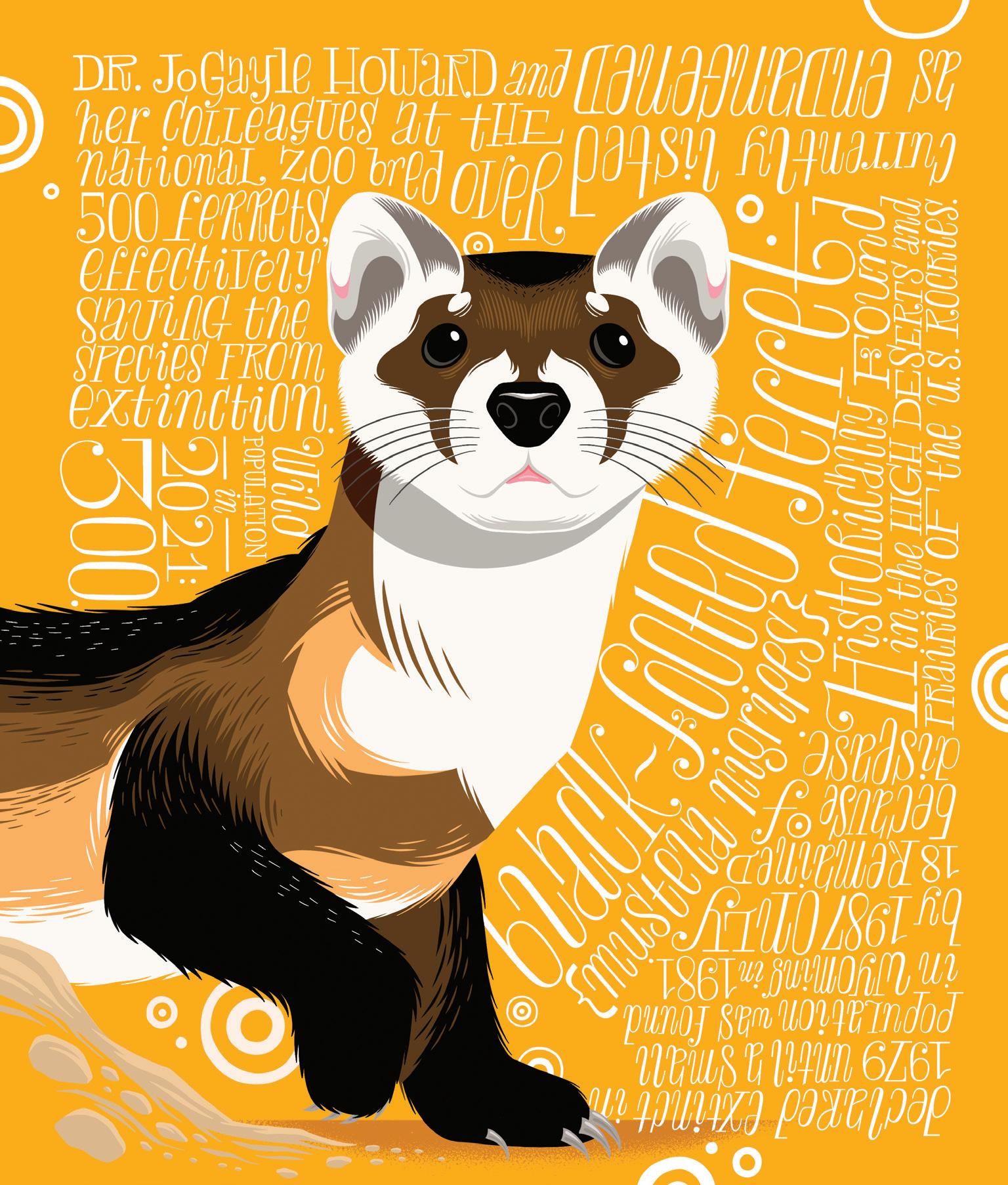

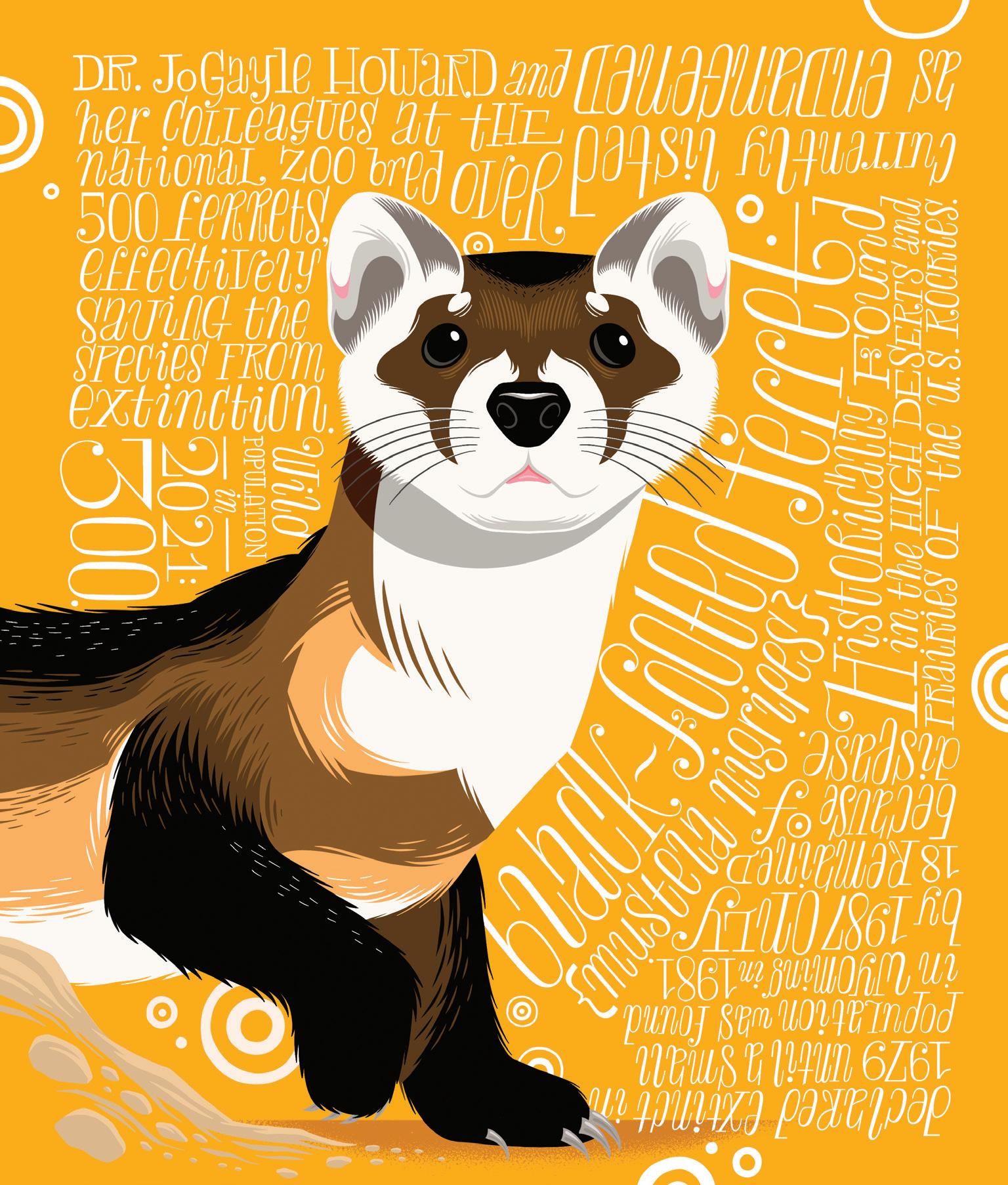

BLACK-FOOTED FERRET

Mustela nigripes

Historically found in the high deserts and prairies of the US Rockies.

Declared extinct in 1979 until a small population was found in Wyoming in 1981. By 1987 only 18 remained because of disease.

Dr. JoGayle Howard and her colleagues at the National Zoo bred over 500 ferrets, effectively saving the species from extinction.

Wild population in 2021: 300. Listed as endangered in 1967.

136

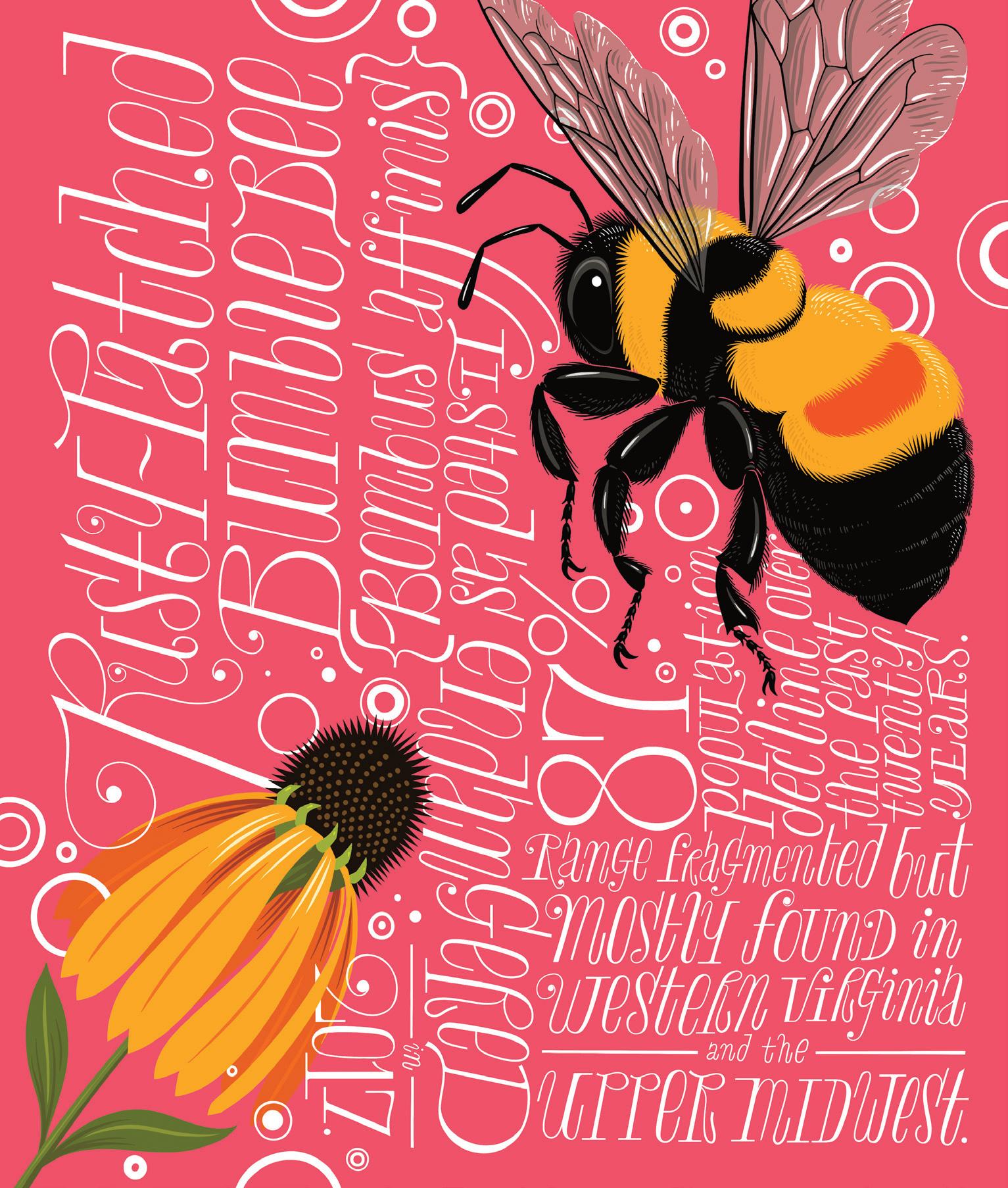

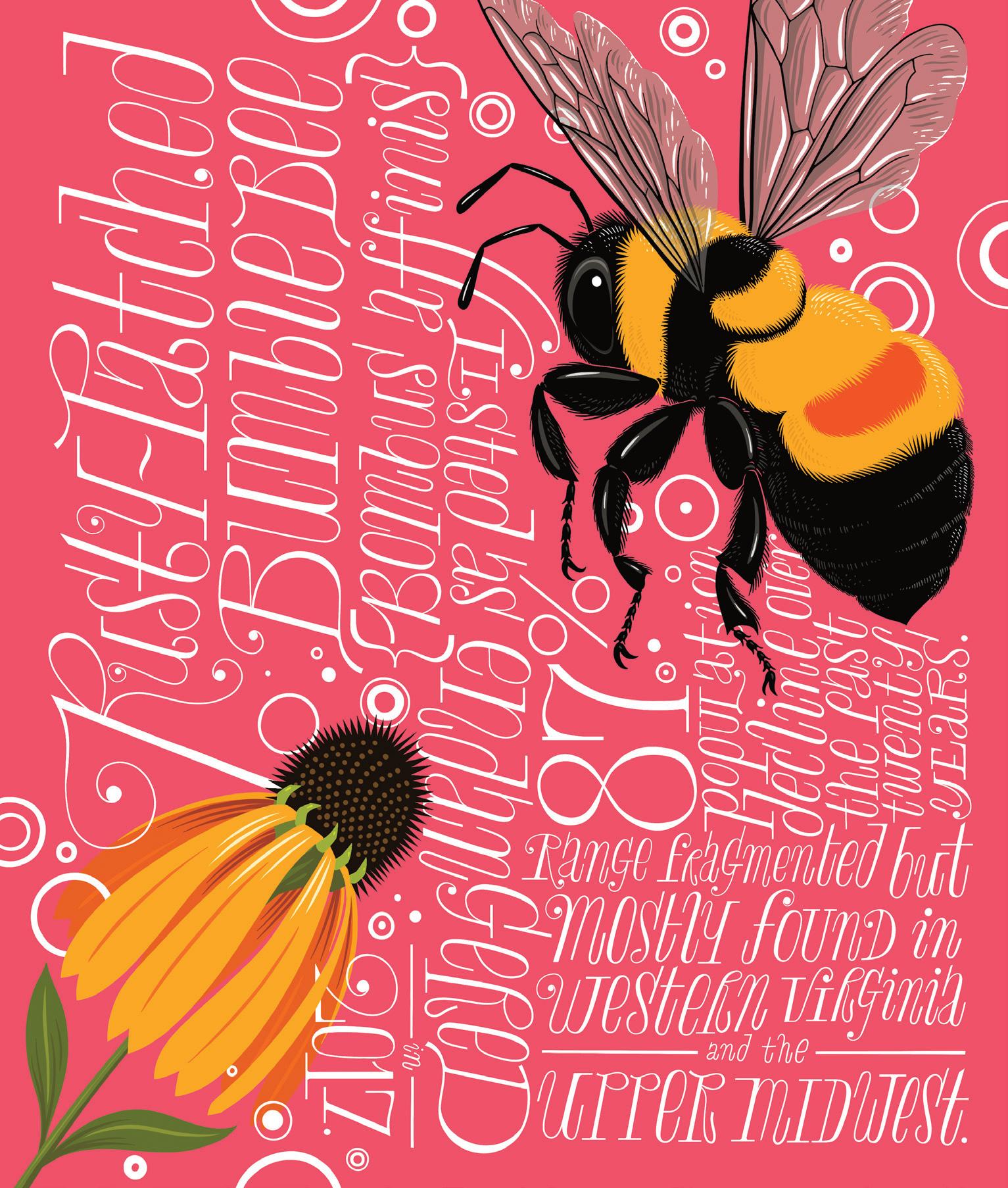

RUSTY-PATCHED BUMBLEBEE

Bombus affinis

Range fragmented but mostly found in western Virginia and the Upper Midwest.

87% population decline over the past 20 years.

Listed as endangered in 2017.

138

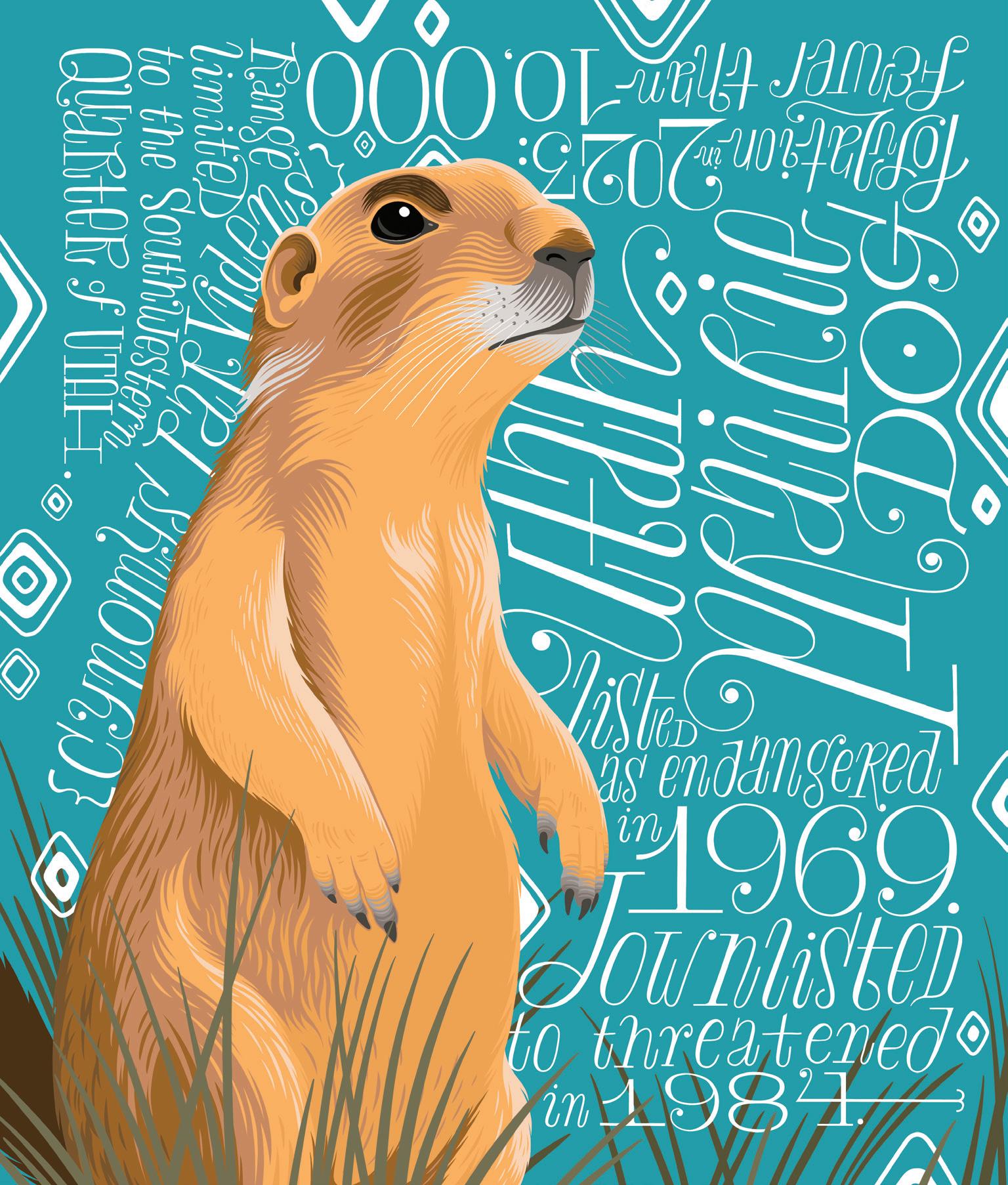

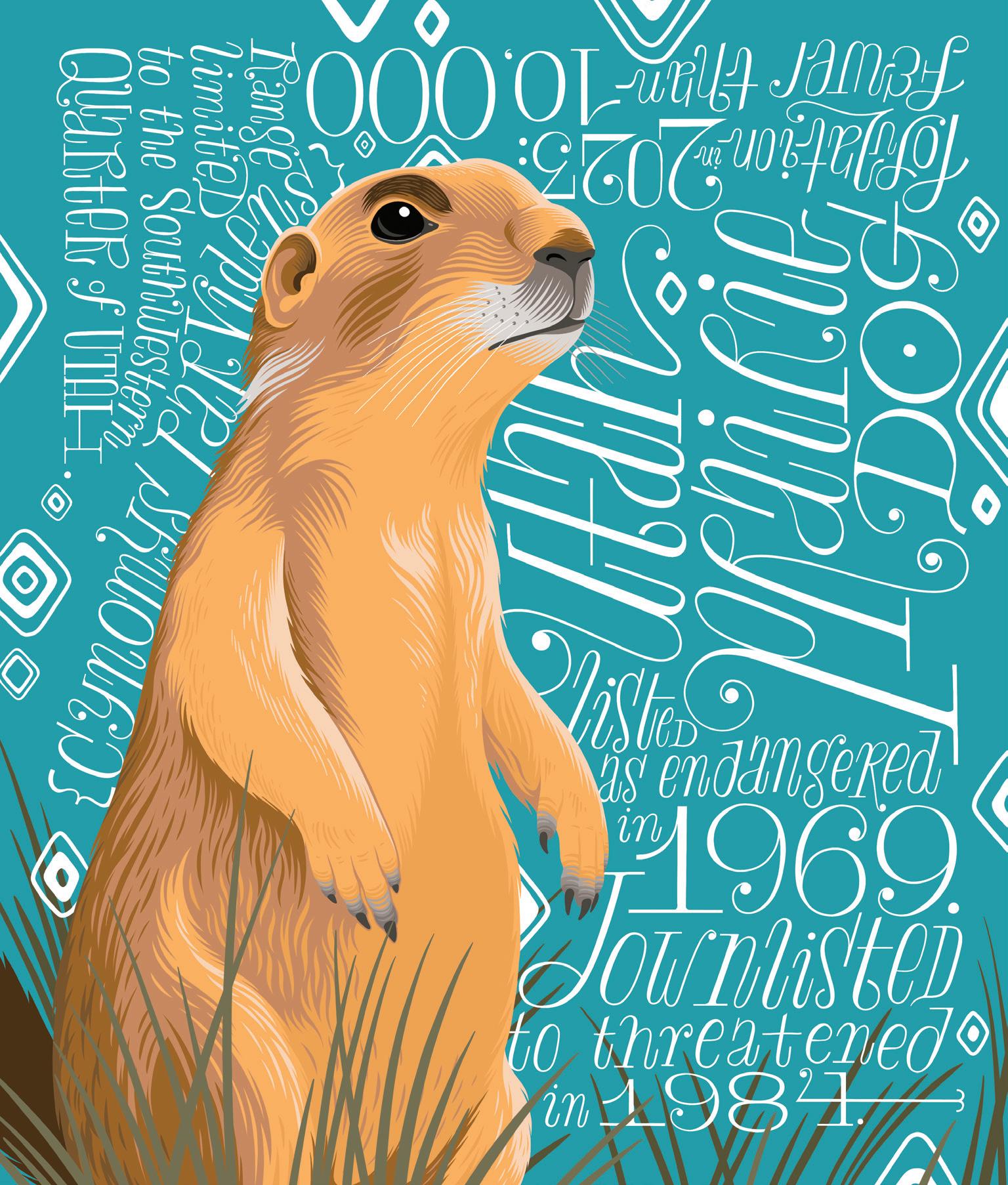

UTAH PRAIRIE DOG

Cynomys parvidens

Range limited to the southwestern quarter of Utah.

Population in 2023: fewer than 10,000.

Listed as endangered in 1969.

Downlisted to threatened in 1984.

140

ISLAND NIGHT LIZARD

Xantusia riversiana

Found only on the Channel Islands off the coast of southern California. Population now over 21.3 million. Listed as threatened in 1977.

Delisted in 2014.

142

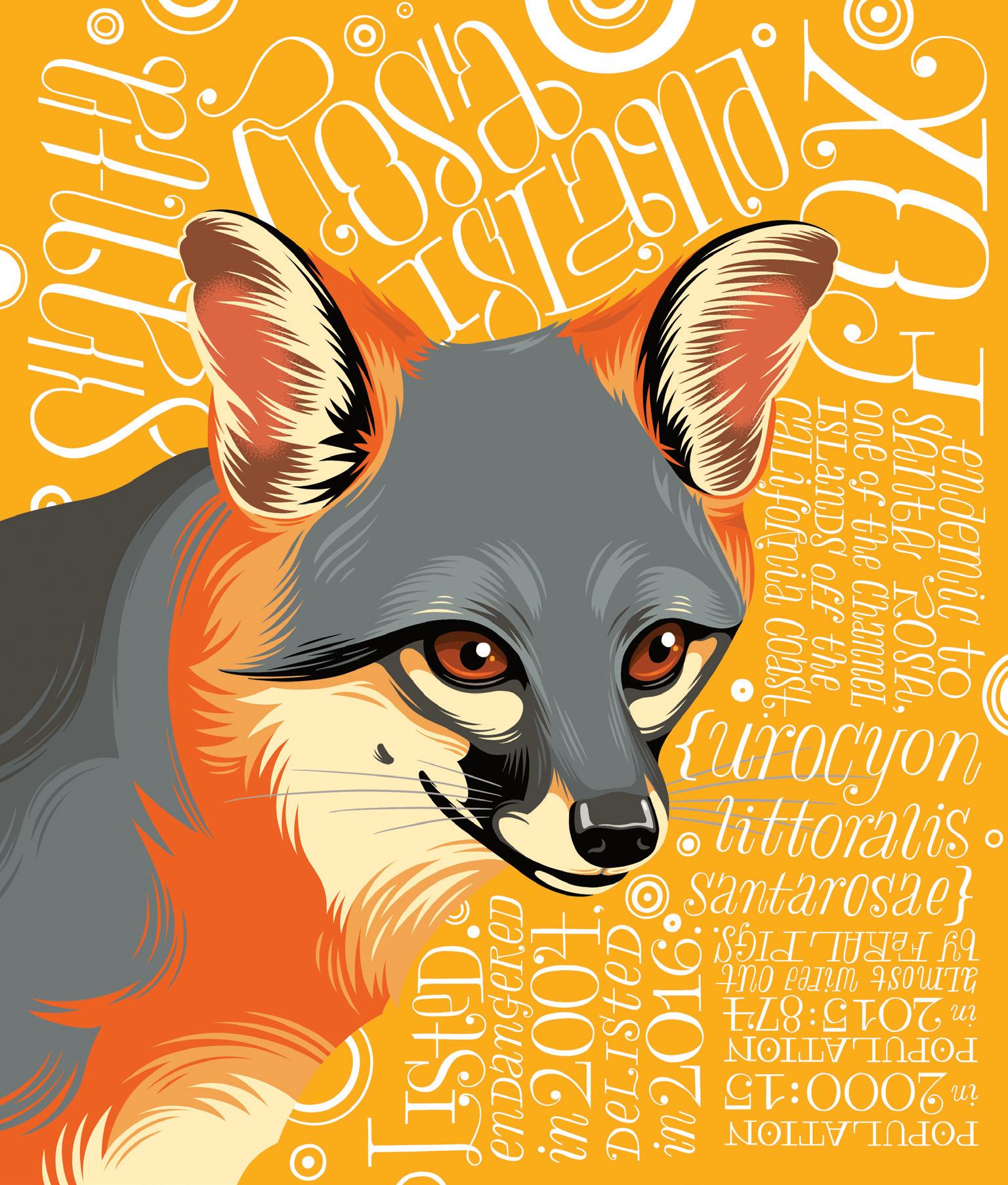

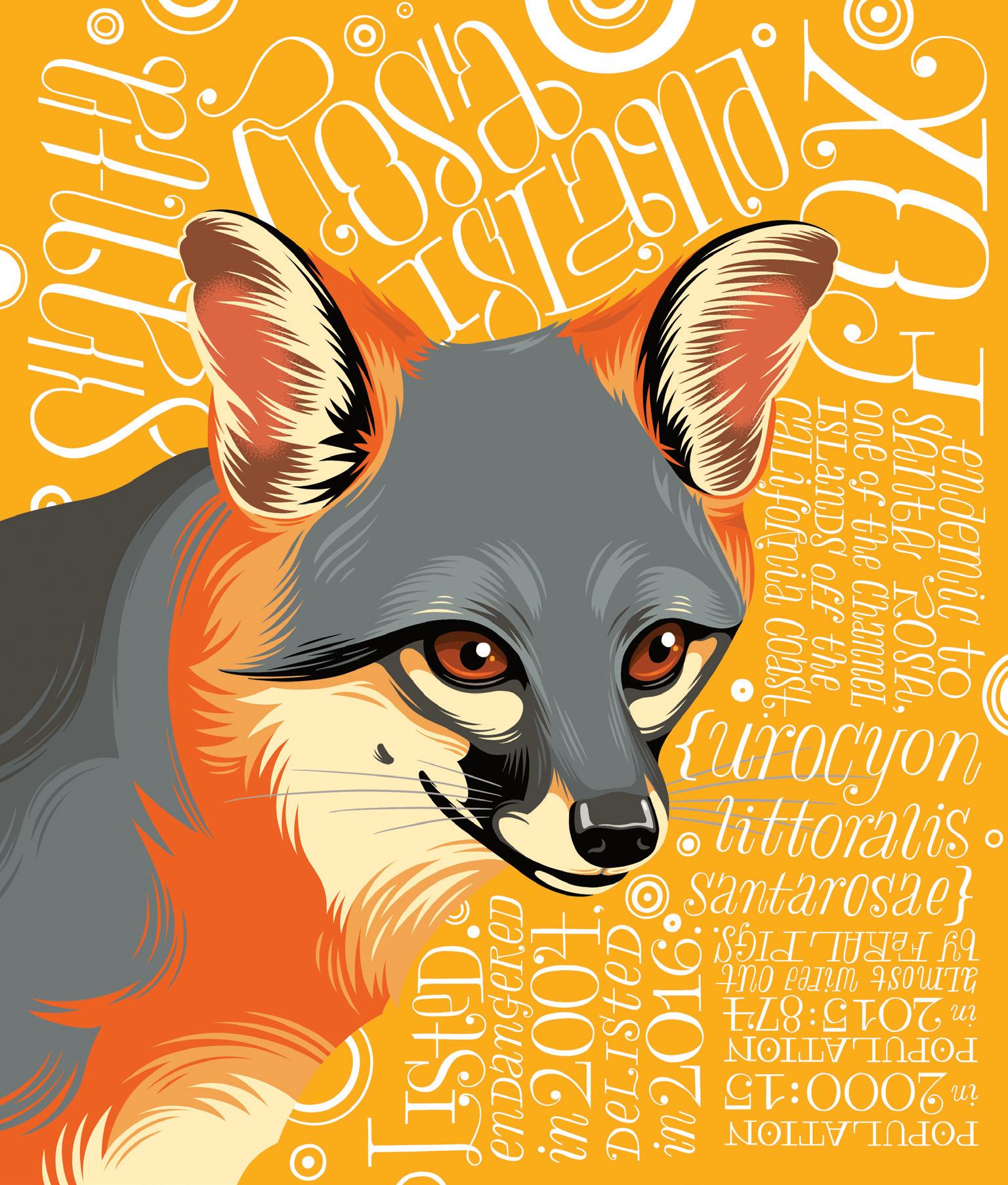

SANTA ROSA ISLAND FOX

Urocyon littoralis santarosae

Endemic to Santa Rosa, one of the Channel Islands off the California coast.

Almost wiped out by golden eagles lured to the island by feral pigs.

Population in 2000: 15.

Population in 2015: 874.

Listed as endangered in 2004.

Delisted in 2016.

144

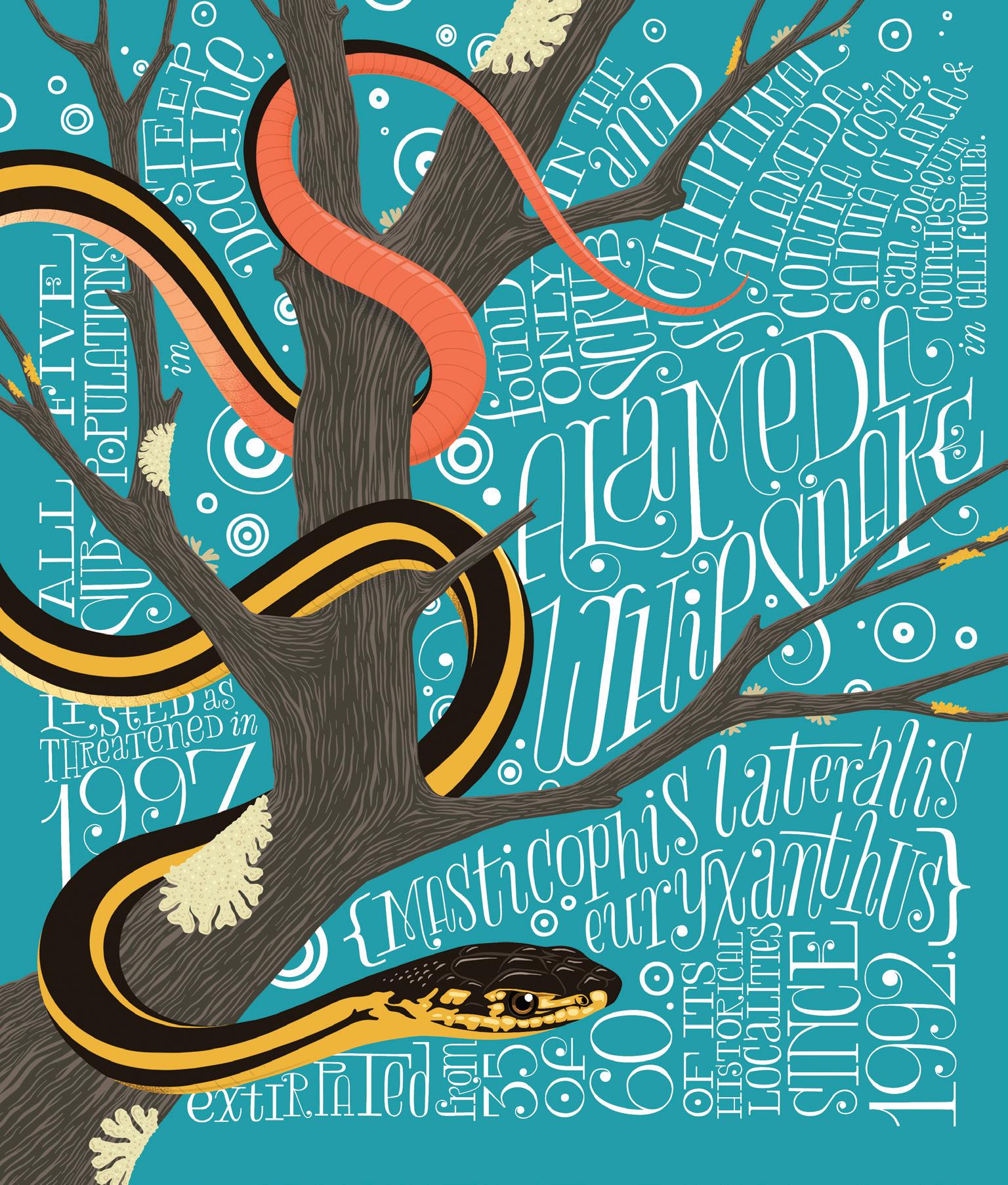

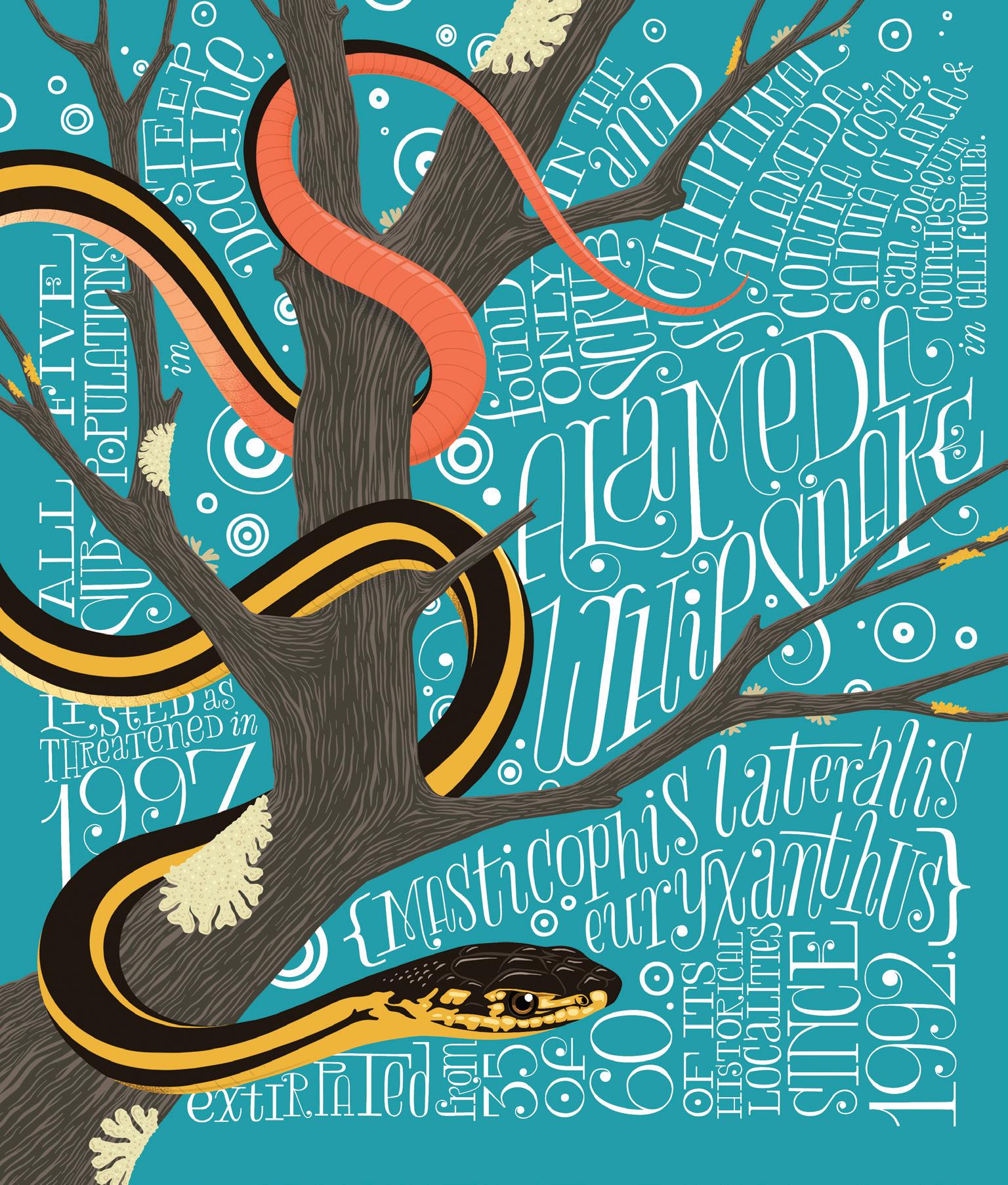

ALAMEDA WHIPSNAKE

Masticophis lateralis euryxanthus

Found only in the scrub and chaparral of Alameda, Contra Costa, Santa Clara, and San Joaquin counties in California.

Extirpated from 35 of its 60 historical localities since 1992.

All 5 sub-populations in steep decline.

Listed as threatened in 1997.

146

AMERICAN BURYING BEETLE

Nicrophorus americanus

Range: isolated populations in the Great Plains.

Animal carcasses are key to its life cycle.

Still listed as endangered, but captive and wild populations are being established.

Listed as endangered in 1989.

148

GREATER SAGE-GROUSE

Centrocercus urophasianus

Lives in the sagebrush grasslands of the western US and Canada.

95% of the original population lost over the past 100 years.

Listing of species was blocked by the U.S. Congress in 2015.

(following page)

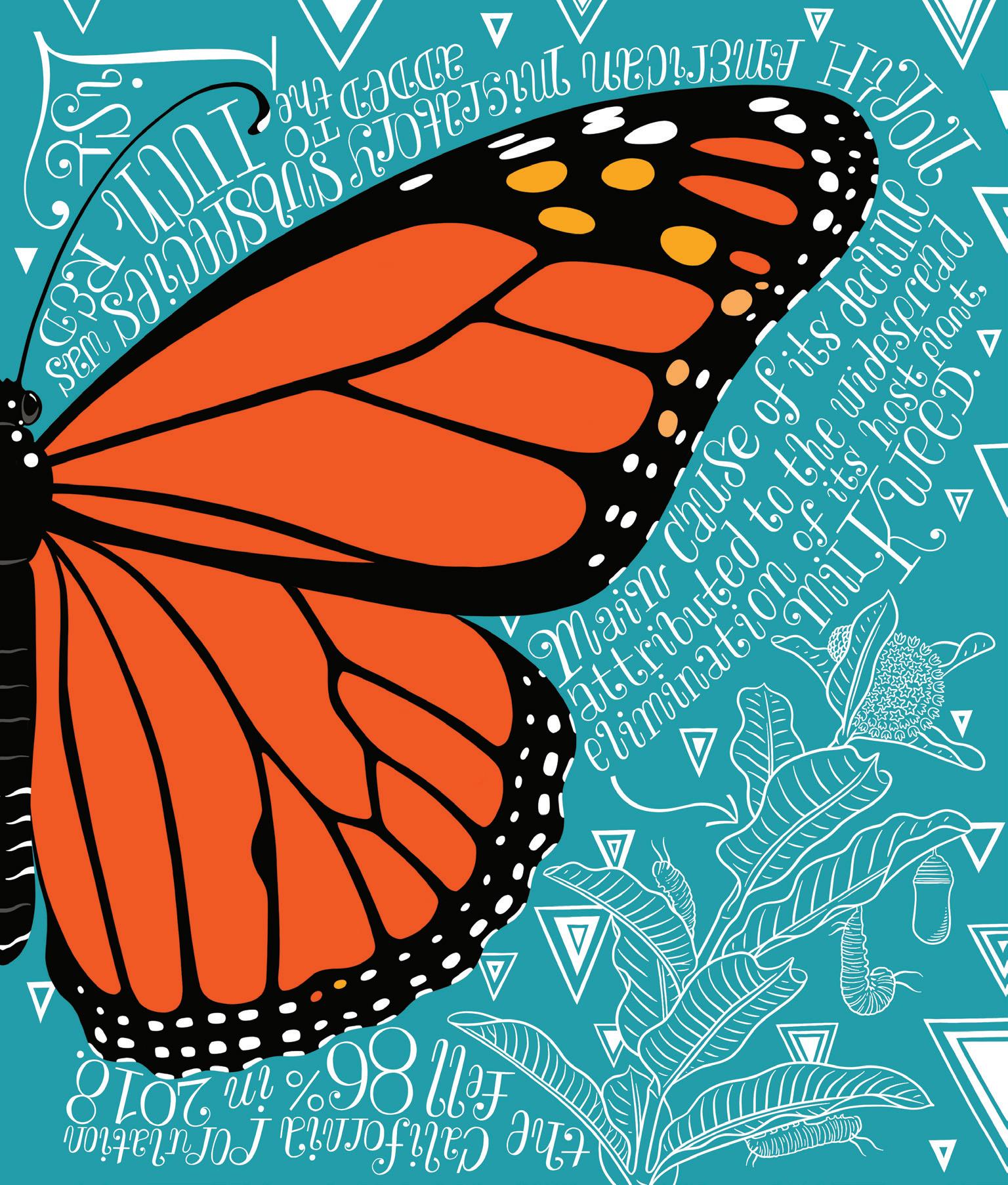

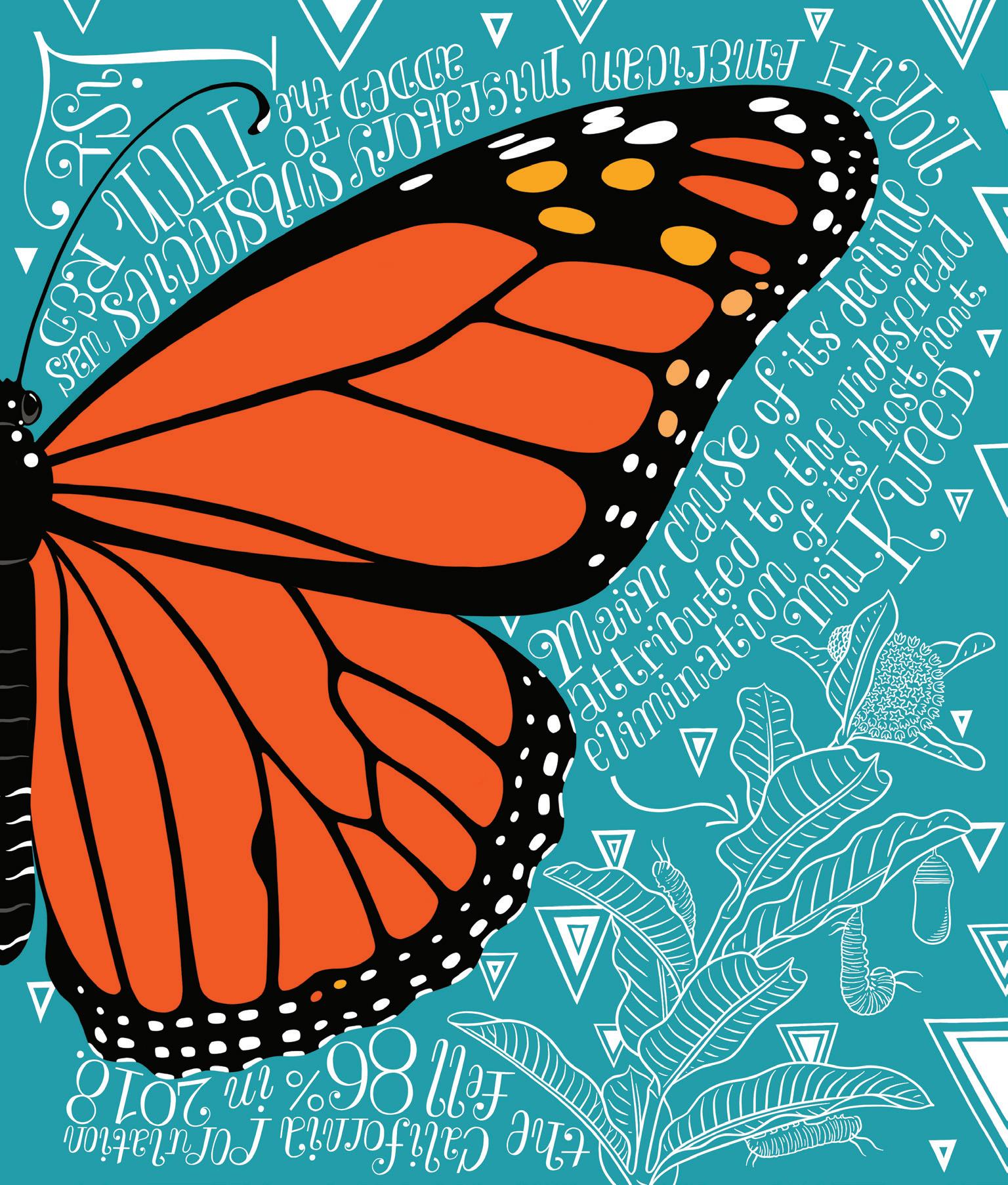

MONARCH BUTTERFLY

Danaus plexippus

Main cause of its decline attributed to the widespread elimination of its host plant, milkweed.

Overwintering numbers east of the Rockies have declined more than 90% since 1995.

The California population fell 86% in 2018.

In 2015, U.S. Fish & Wildlife reported that nearly a billion monarchs have vanished from overwintering sites in the US since 1990.

North American migratory subspecies was added to the IUCN Red List of endangered species in 2022.

150

WOOD BISON

AMERICAN BISON ECOTYPE

Bison bison athabascae

Found in the boreal forests of Alaska and the Canadian Northwest.

Total free-ranging disease-free population in 2015: about 5,000.

Downlisted to threatened in 2012.

(following page)

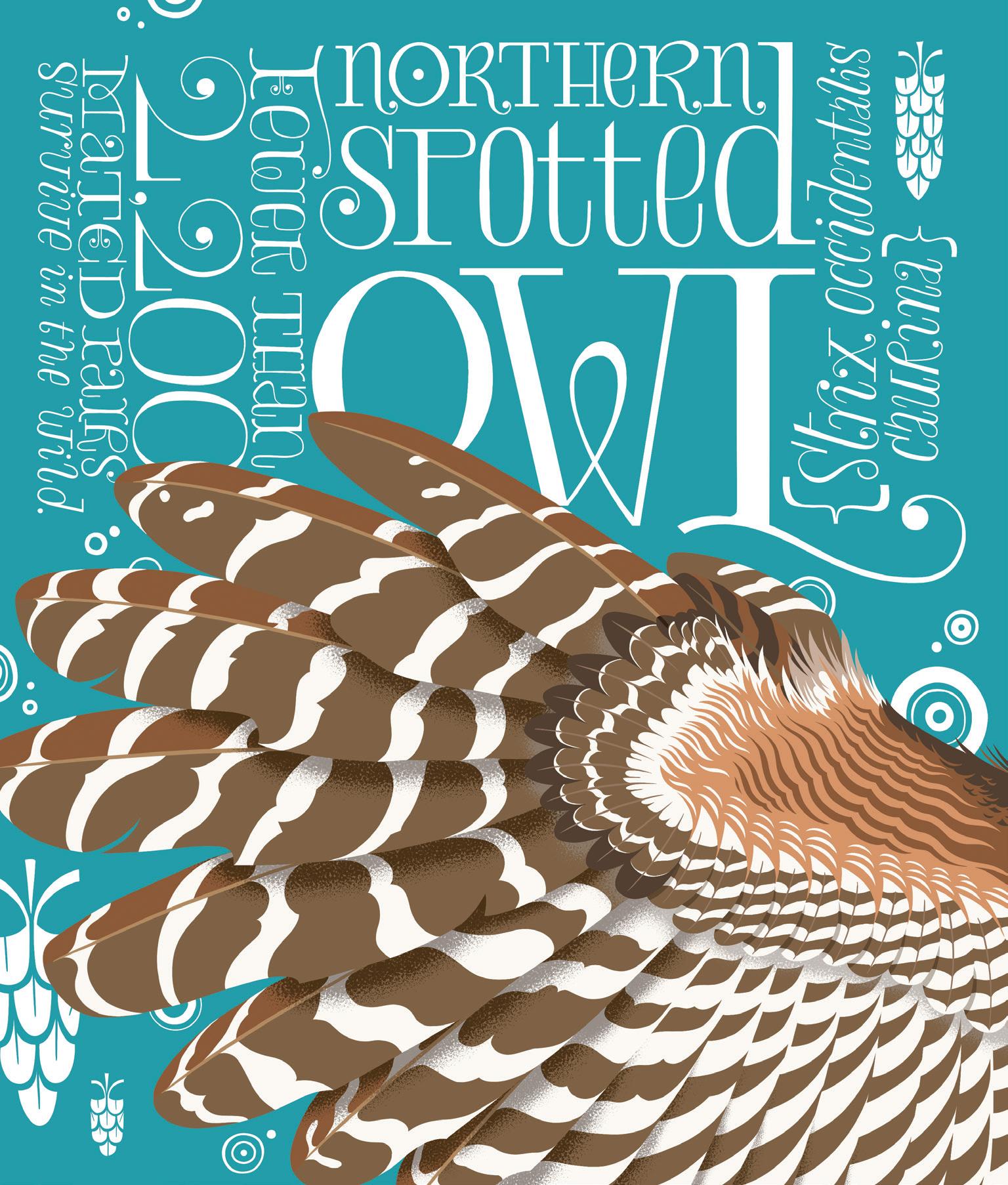

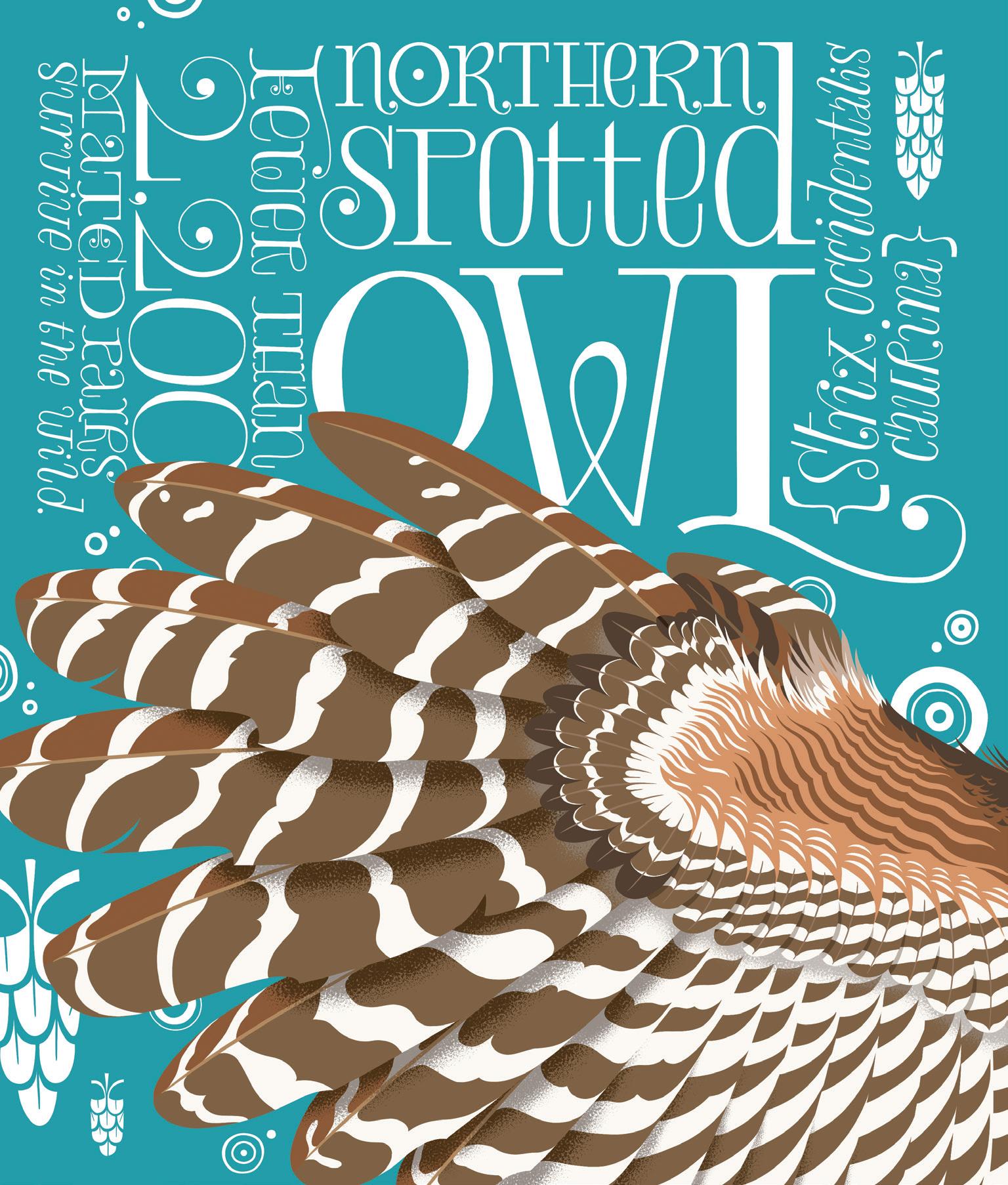

NORTHERN SPOTTED OWL

Strix occidentalis caurina

Lives in old-growth forests of the Pacific Northwest.

70% decline in population since 1995, attributed to habitat loss and competition with barred owls.

Fewer than 2,200 mated pairs survive in the wild.

Listed as threatened in 1990.

156

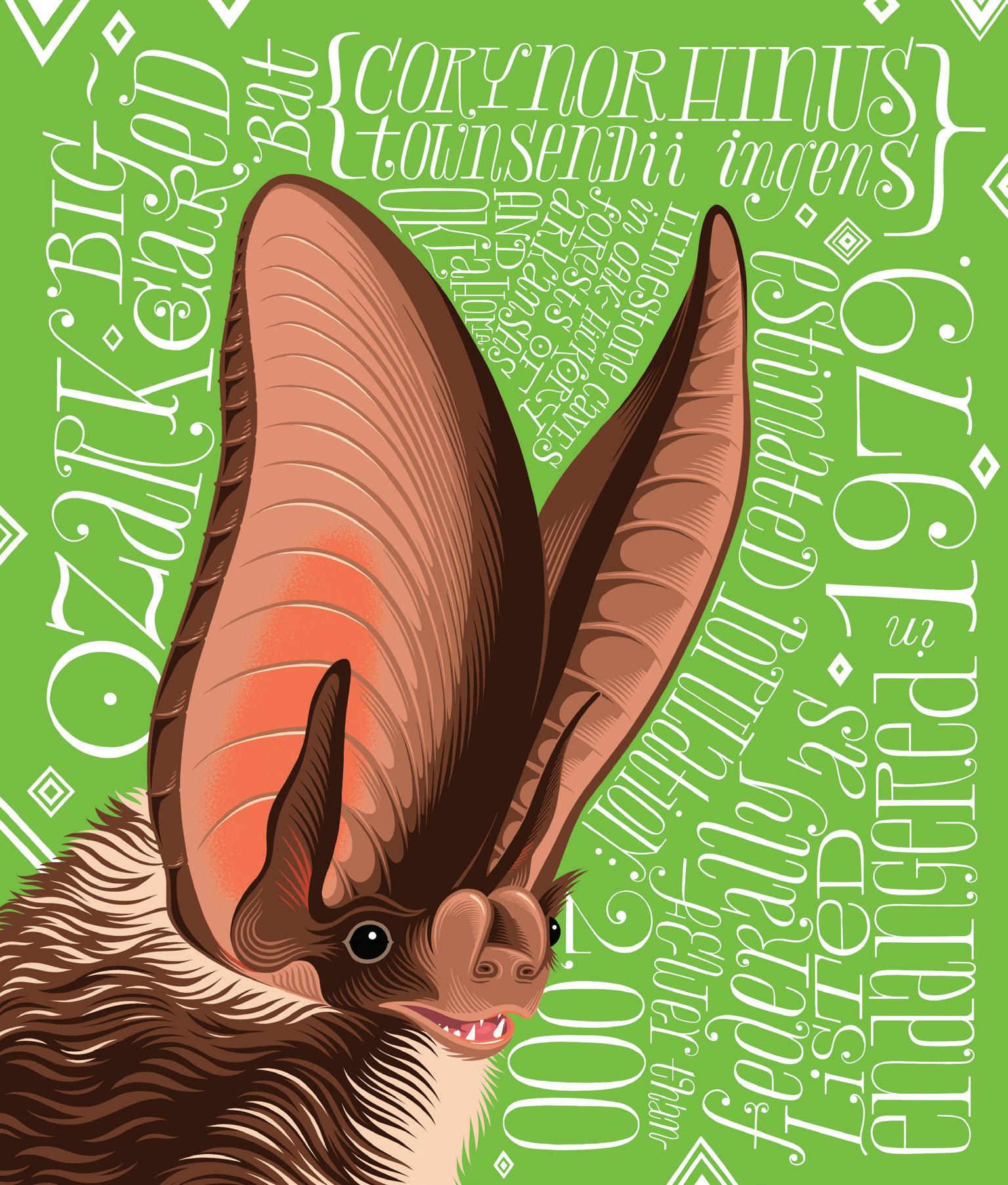

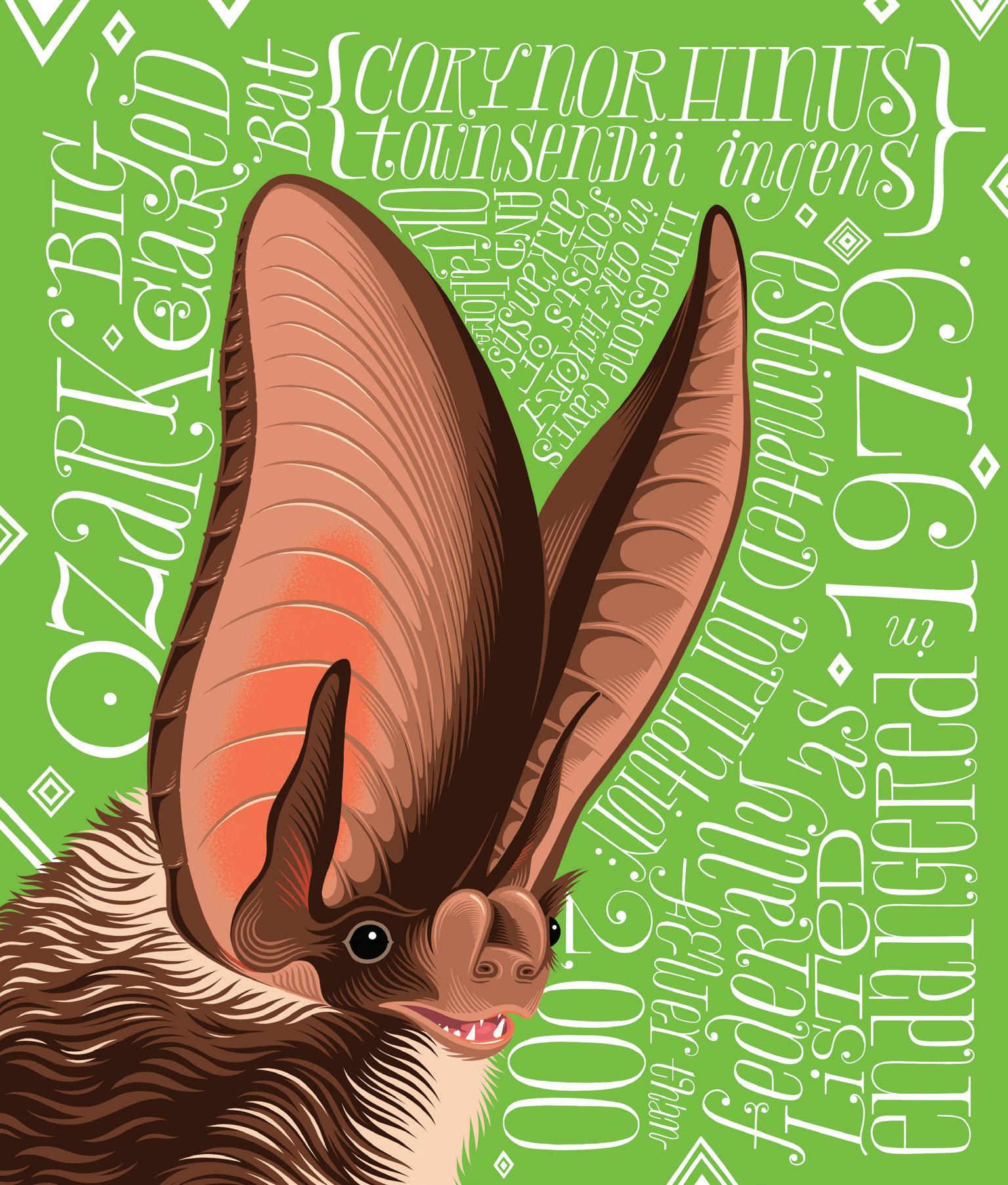

OZARK BIG-EARED BAT

Corynorhinus townsendii ingens

Found in limestone caves in oak-hickory forests of Arkansas, Oklahoma, and Missouri.

Estimated population: less than 2,000.

Listed as endangered in 1979.

160

GOLDEN-CHEEKED WOOD WARBLER

Setophaga chrysoparia

Breeds in Ashe juniper habitats in central Texas.

Estimated population: 9,600 singing males.

Listed as endangered in 1990.

162

COLUMBIAN WHITE-TAILED DEER

Odocoileus virginianus leucurus

2 populations: lower Columbia River and Douglas County, Oregon.

Total population in 1968: less than 1,000.

Douglas County population now: over 6,000.

Douglas County population delisted in 2003.

Lower Columbia River population in 2019: 1,300.

Lower Columbia River population reclassified from endangered to threatened in 2016.

Listed as endangered in 1968.

164

KIRTLAND’S WARBLER

Setophaga kirtlandii

Breeds in the young jack pines of Michigan’s Lower Peninsula.

Population in 1974: 167 singing males.

Population in 2015: 2,365 singing males.

(following page)

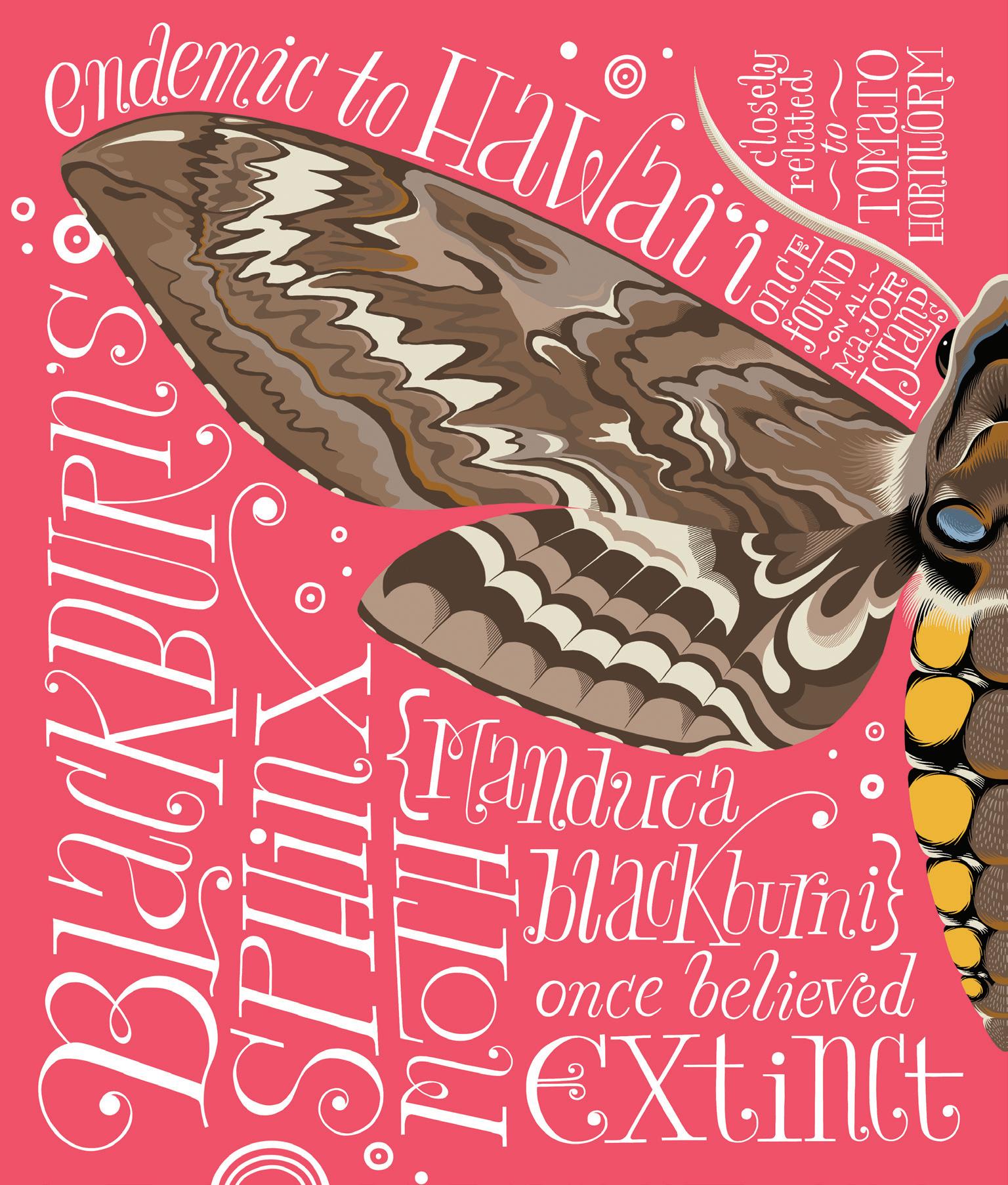

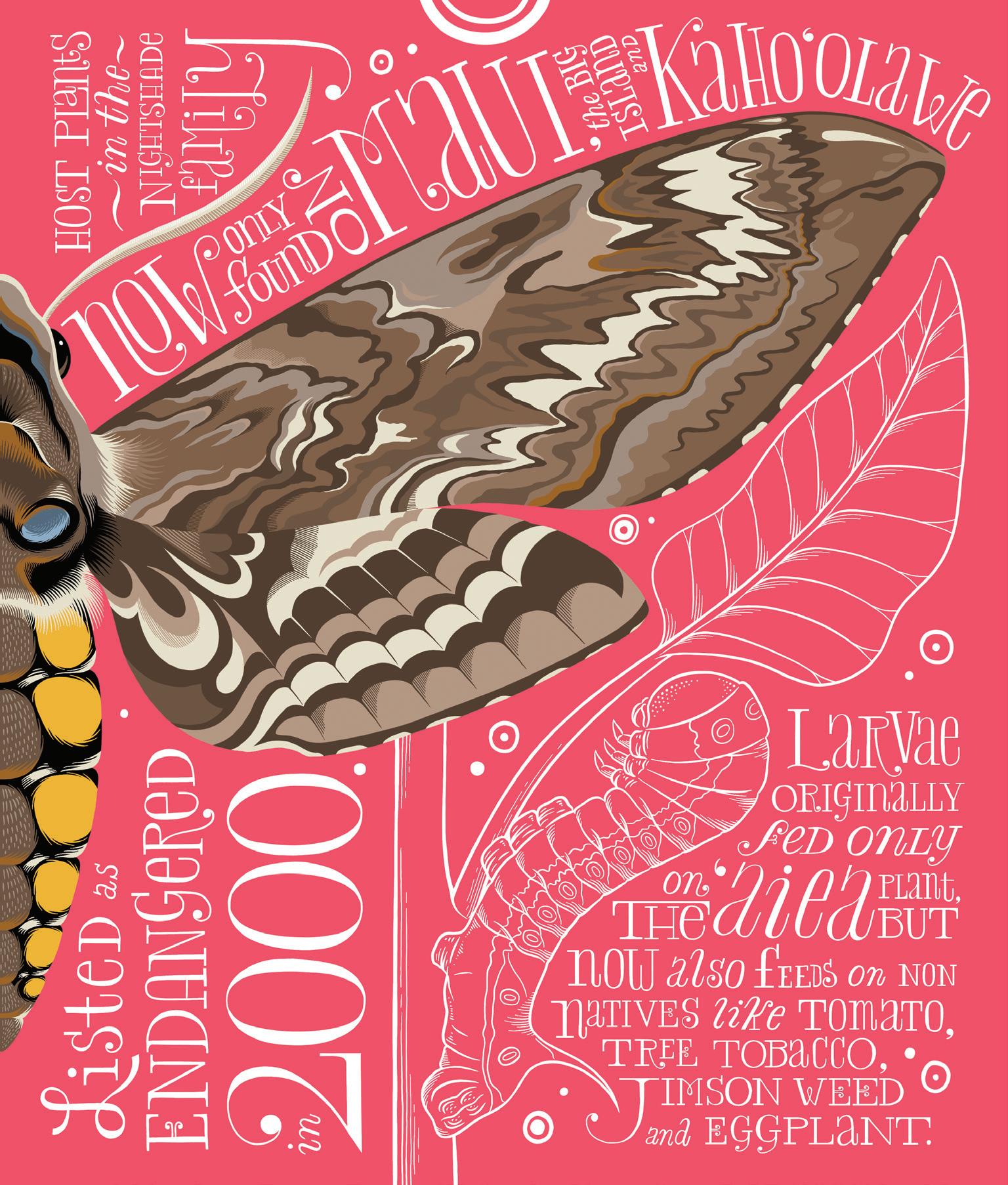

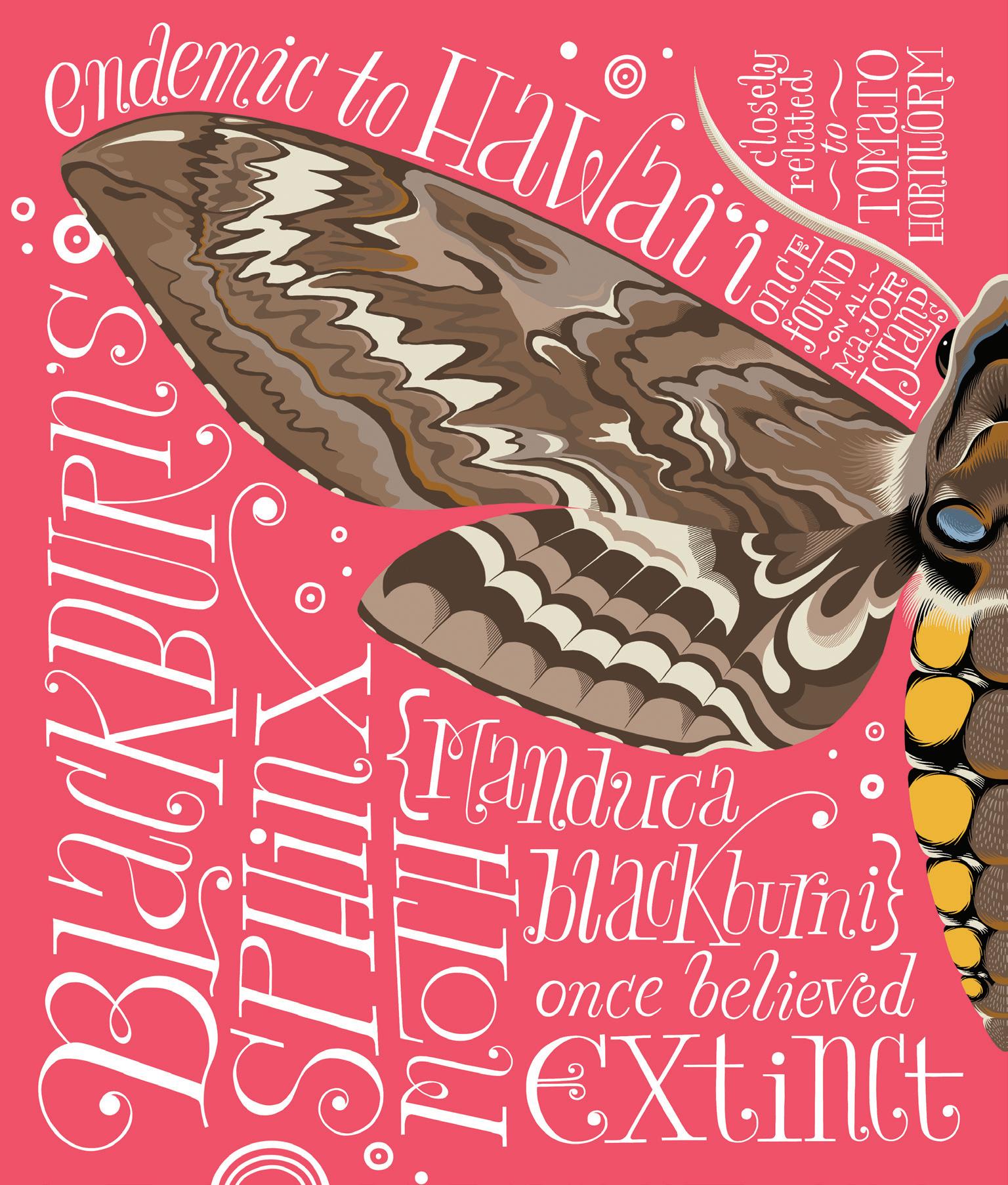

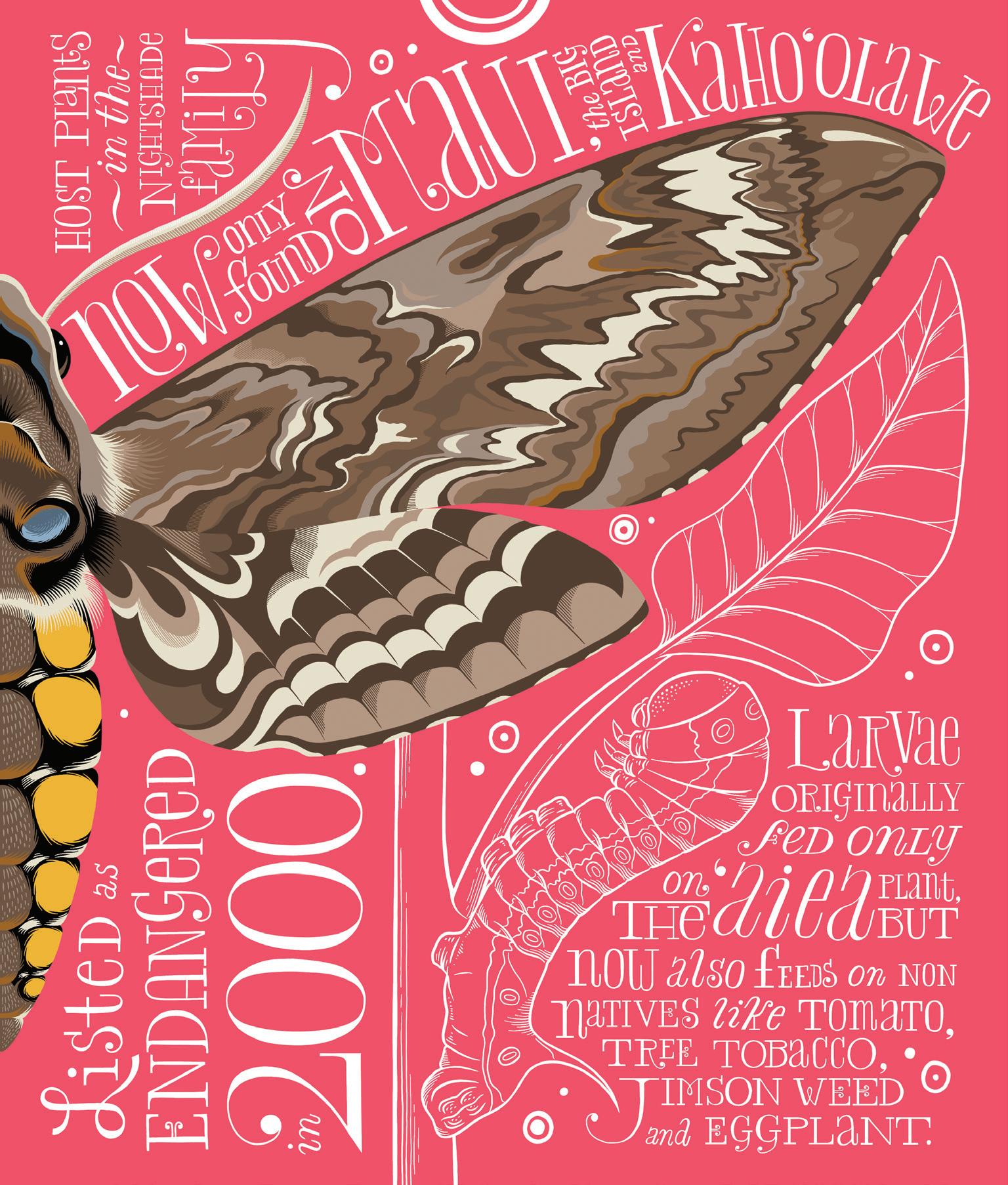

BLACKBURN’S SPHINX MOTH

Manduca blackburni

Closely related to tomato hornworm.

Host plants in the nightshade family.

Larvae originally fed only on the 'aiea plant, but now also feed on non-natives like tomato, tree tobacco, jimson weed, and eggplant.

Endemic to Hawai'i. Once found on all major islands. Now only found on Maui, the Big Island, and Kaho'olawe.

Once believed extinct.

Listed as endangered in 2000.

166

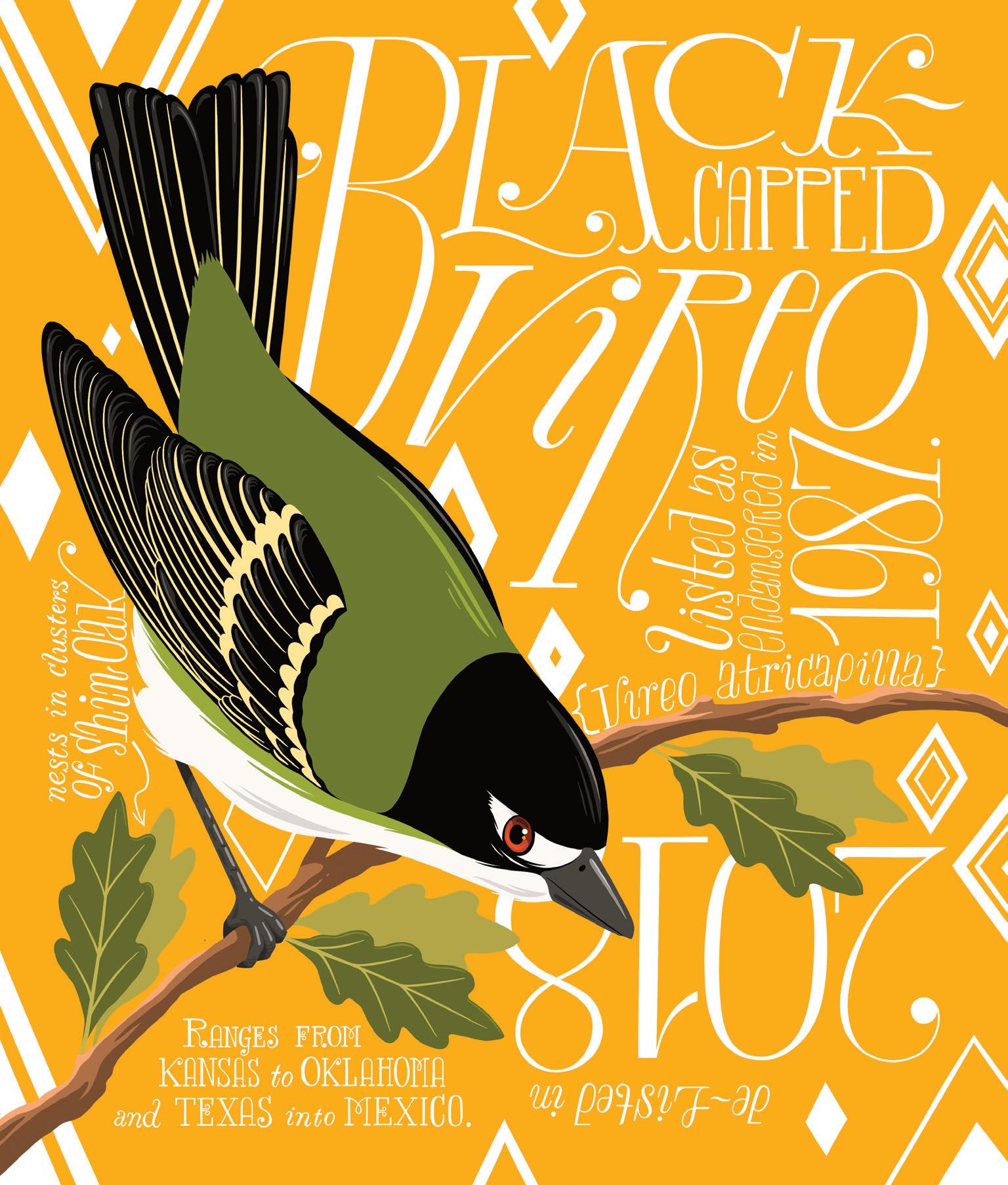

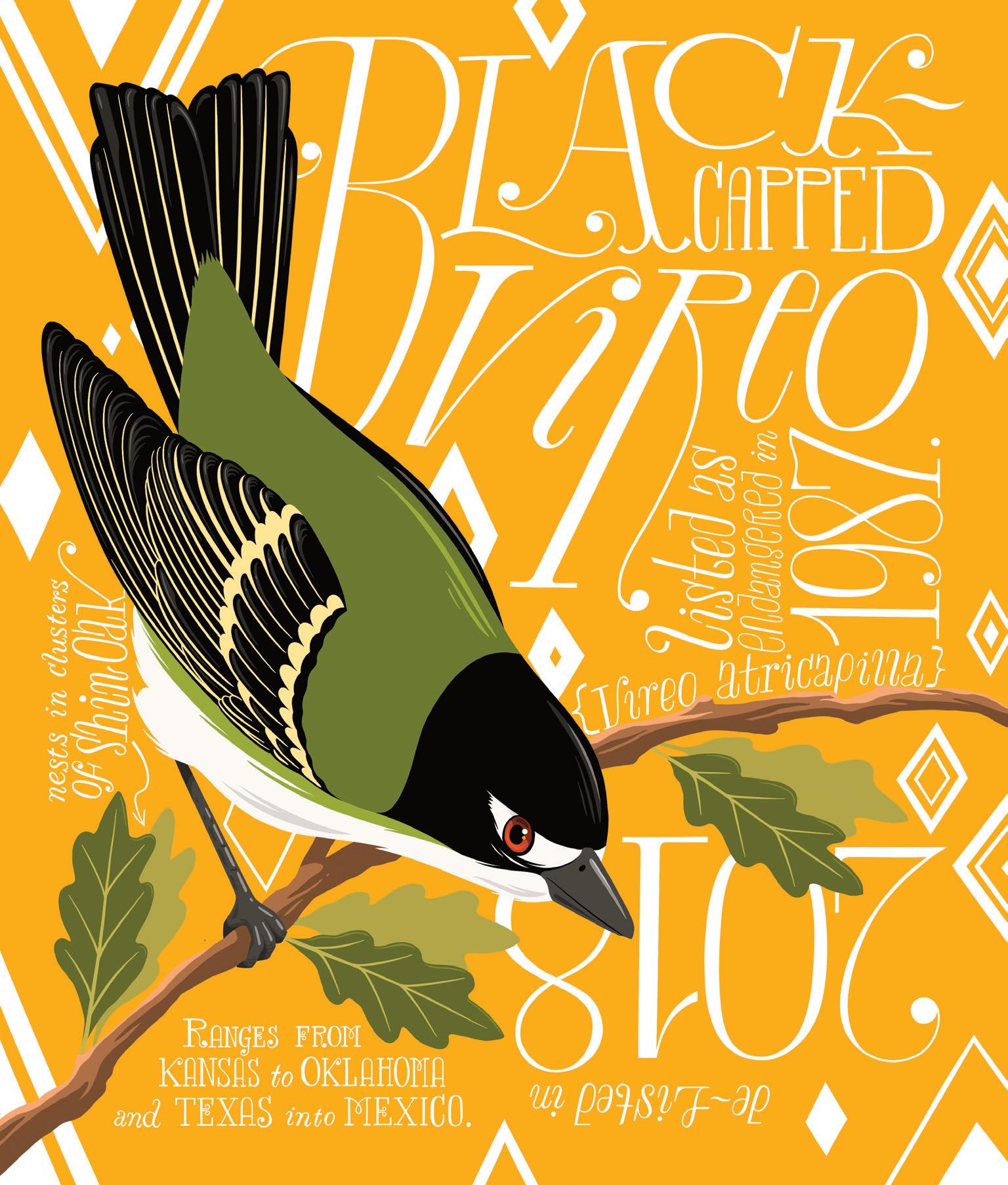

BLACK-CAPPED VIREO Vireo atricapilla

Ranges from Kansas to Oklahoma and Texas into Mexico.

Nests in clusters of shin oak.

Listed as endangered in 1987.

Delisted in 2018.

170

VIRGINIA NORTHERN FLYING SQUIRREL

Glaucomys sabrinus fuscus

Found mainly in Monongahela National Forest.

Listed as endangered in 1985 {only 10 known to exist at the time}.

Population in 2013: 1,100.

Delisted in 2013.

172

FLORIDA LEAFWING BUTTERFLY

Anaea troglodyta floridalis

Found in the pine rocklands of the Florida Everglades.

Host plant is pineland croton {Croton linearis}.

Estimated population in 2012: less than 700.

Listed as endangered in 2014.

174

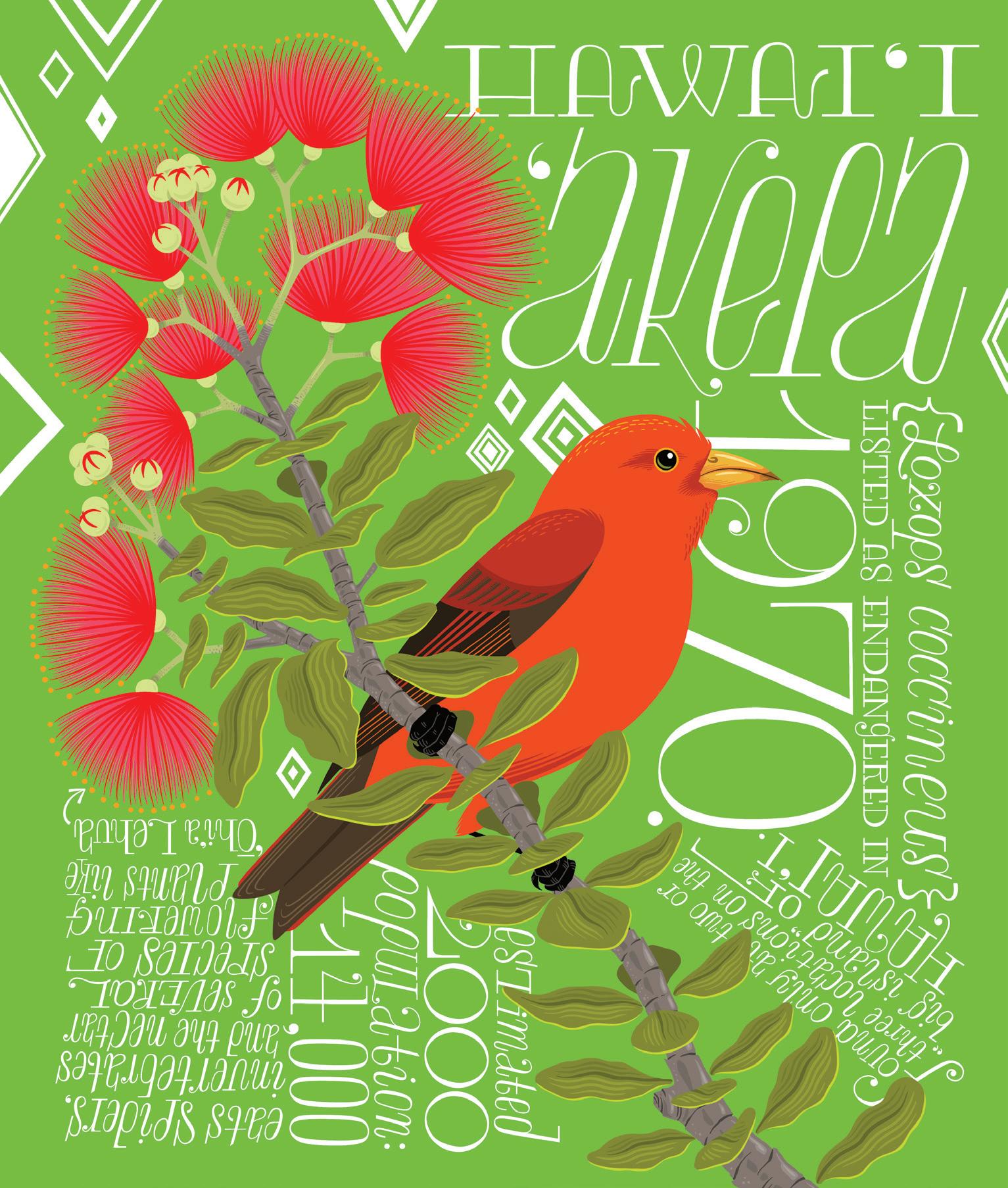

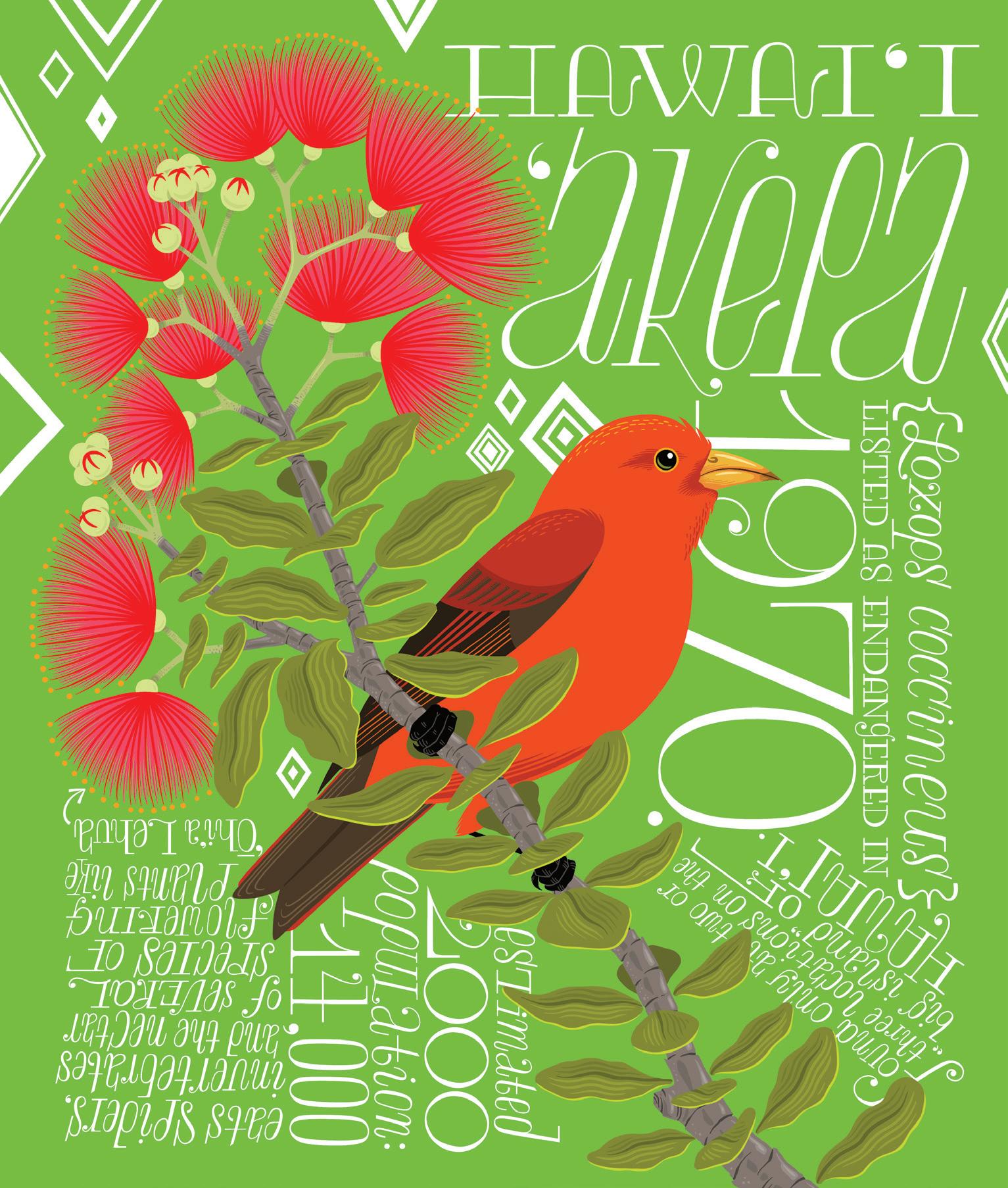

HAWAI ' I ' AKEPA

Loxops coccineus

Found only at 2 or 3 locations on the Big Island of Hawai'i.

Eats spiders, invertebrates, and the nectar of several species of flowering plants like 'Ōhi'a lehua.

Listed as endangered in 1970.

Estimated 2000 population: 14,000.

(following page)

BALD EAGLE

Haliaeetus leucocephalus

1963 population in the lower 48 states: 417.

Population in 2007: 10,000.

Listed as endangered in 1967.

Delisted in 2007.

176

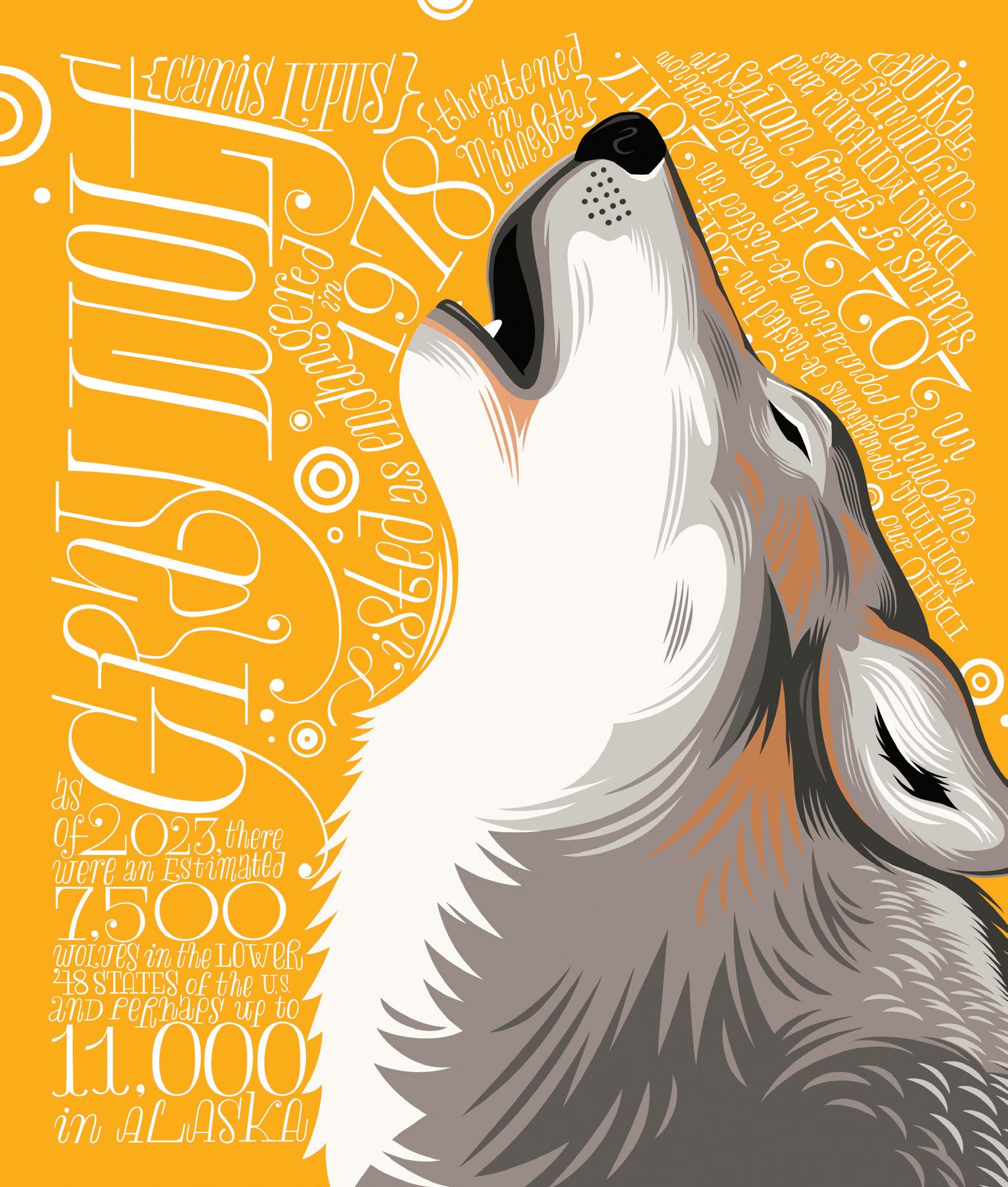

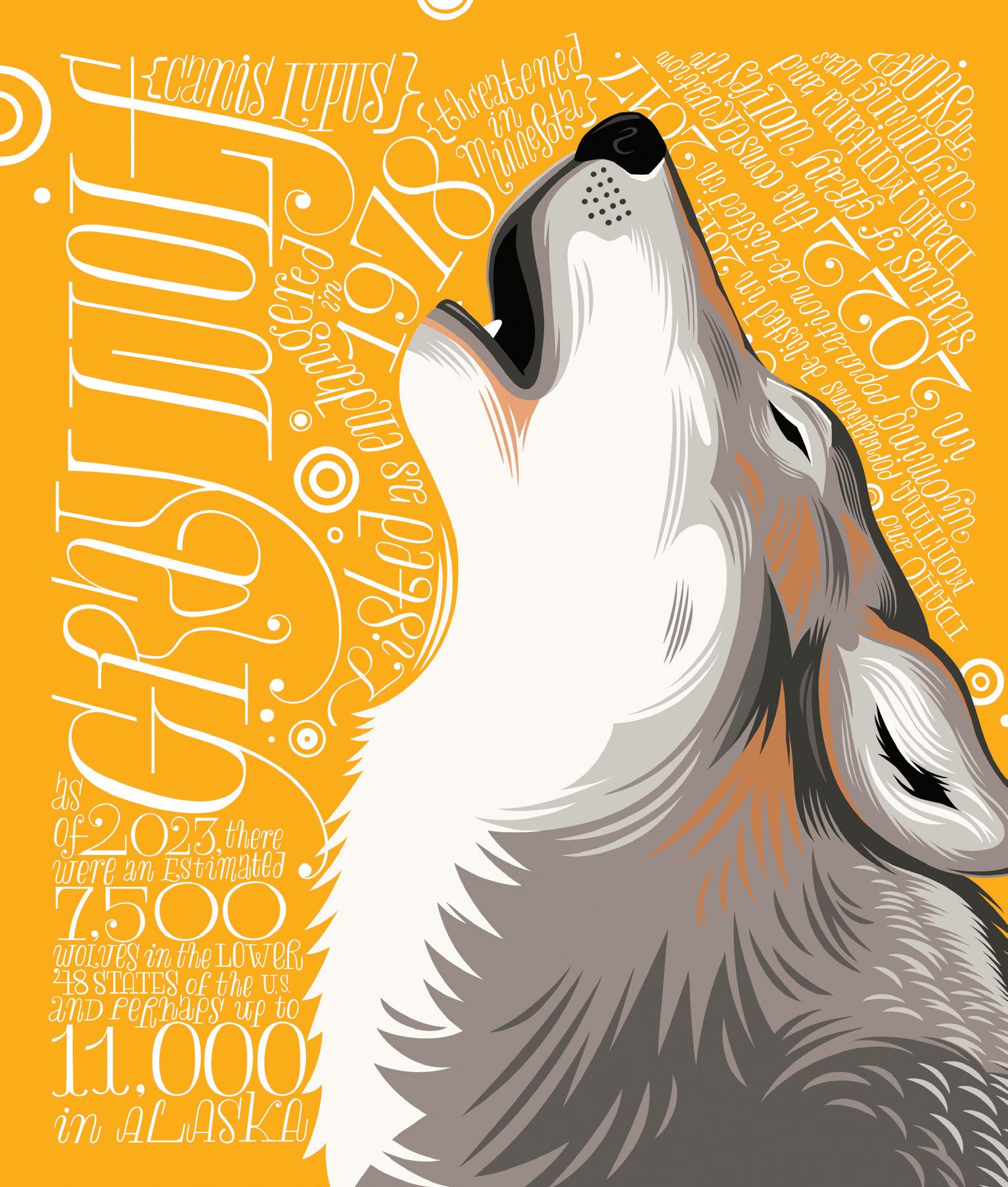

GRAY WOLF Canis lupus

Listed as endangered in 1978 {threatened in Minnesota}.

Idaho and Montana populations delisted in 2011. Wyoming population delisted in 2017.

In 2022 the conservation status of gray wolves in Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming was restored.

As of 2023, there were an estimated 7,500 wolves in the lower 48 states of the US and perhaps up to 11,000 in Alaska.

180

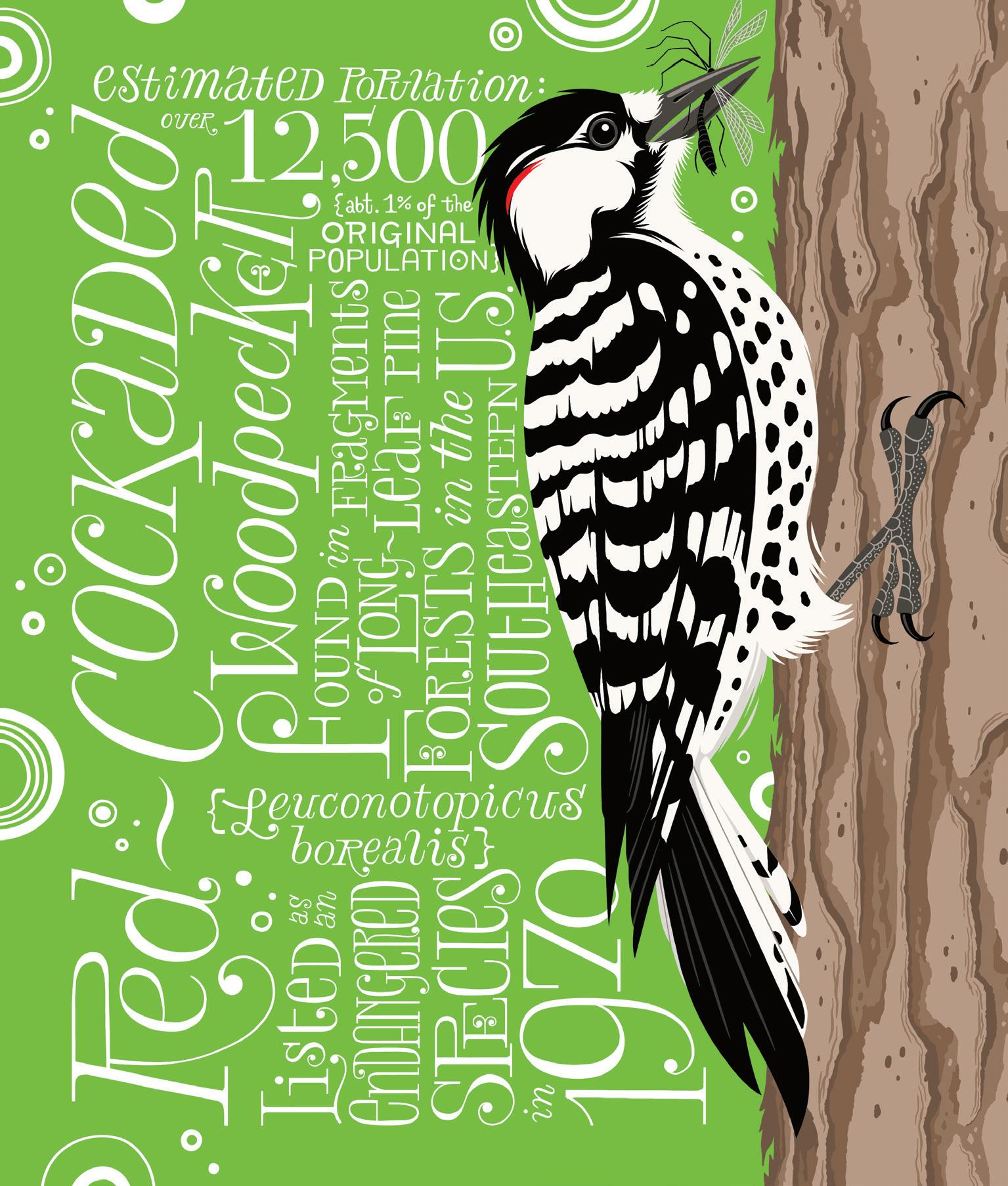

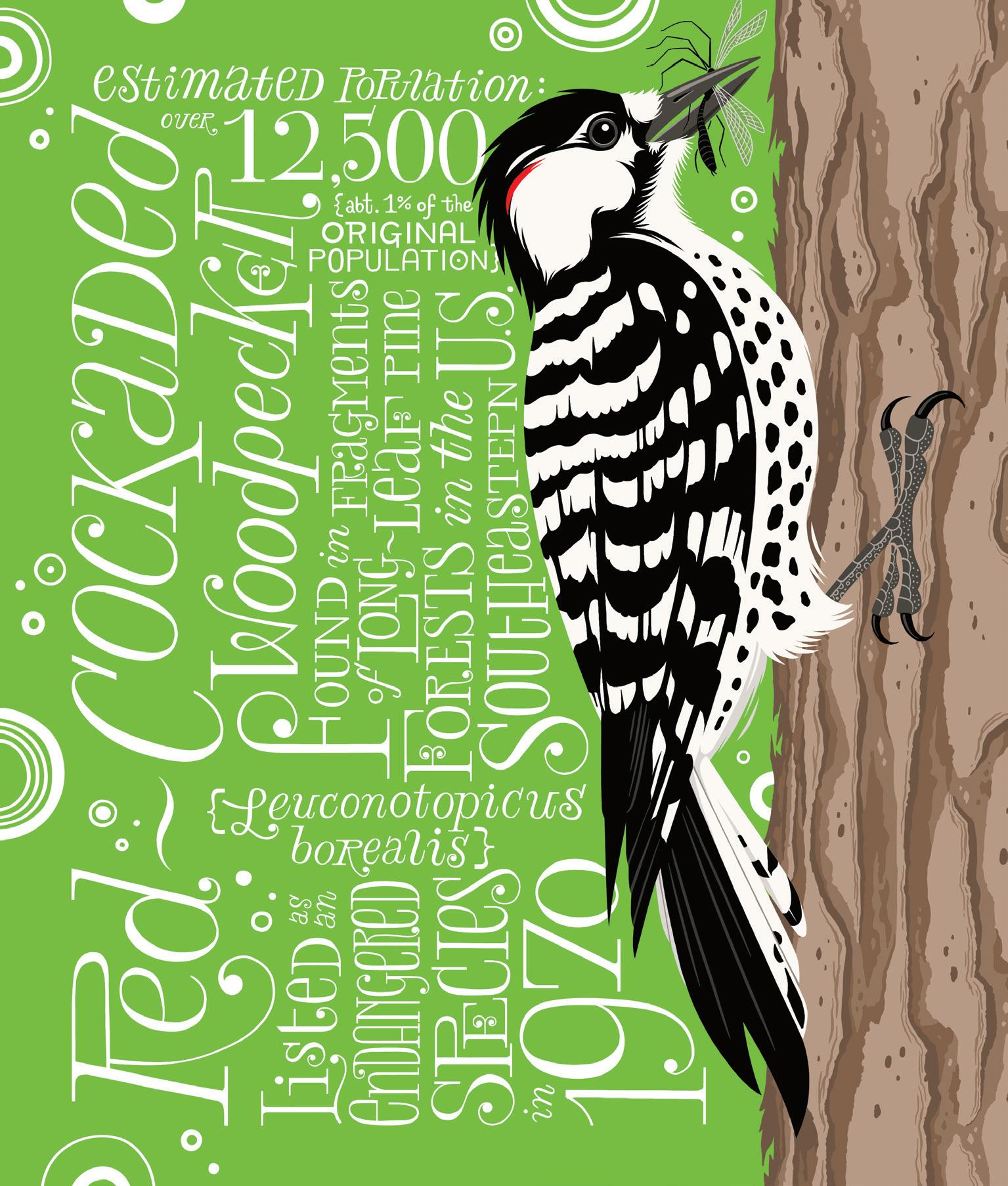

RED-COCKADED WOODPECKER

Leuconotopicus borealis

Found in fragments of longleaf pine forests in the southeastern US.

Estimated population: over 12,500 {about 1% of the original population}.

Listed as endangered in 1970.

182

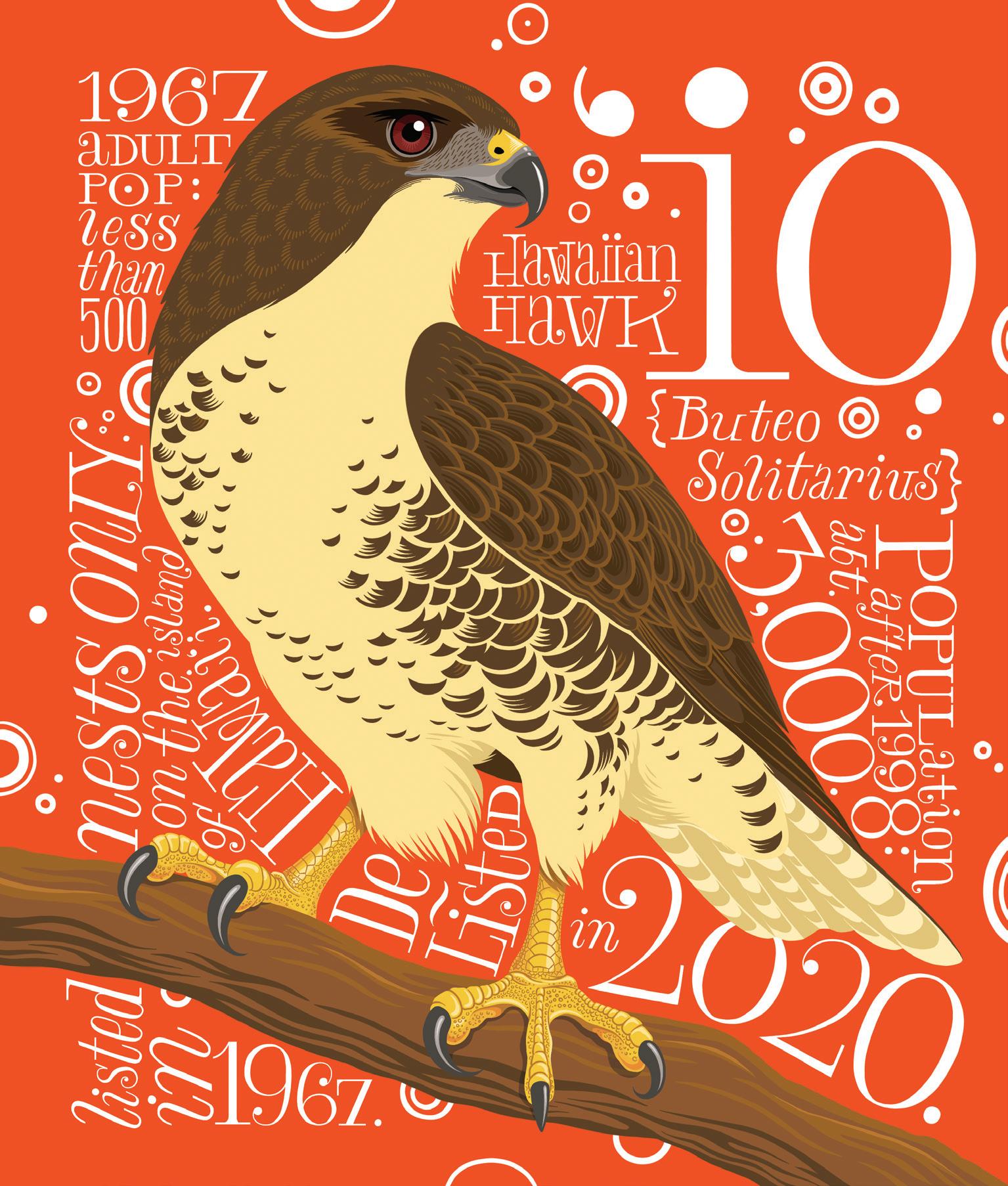

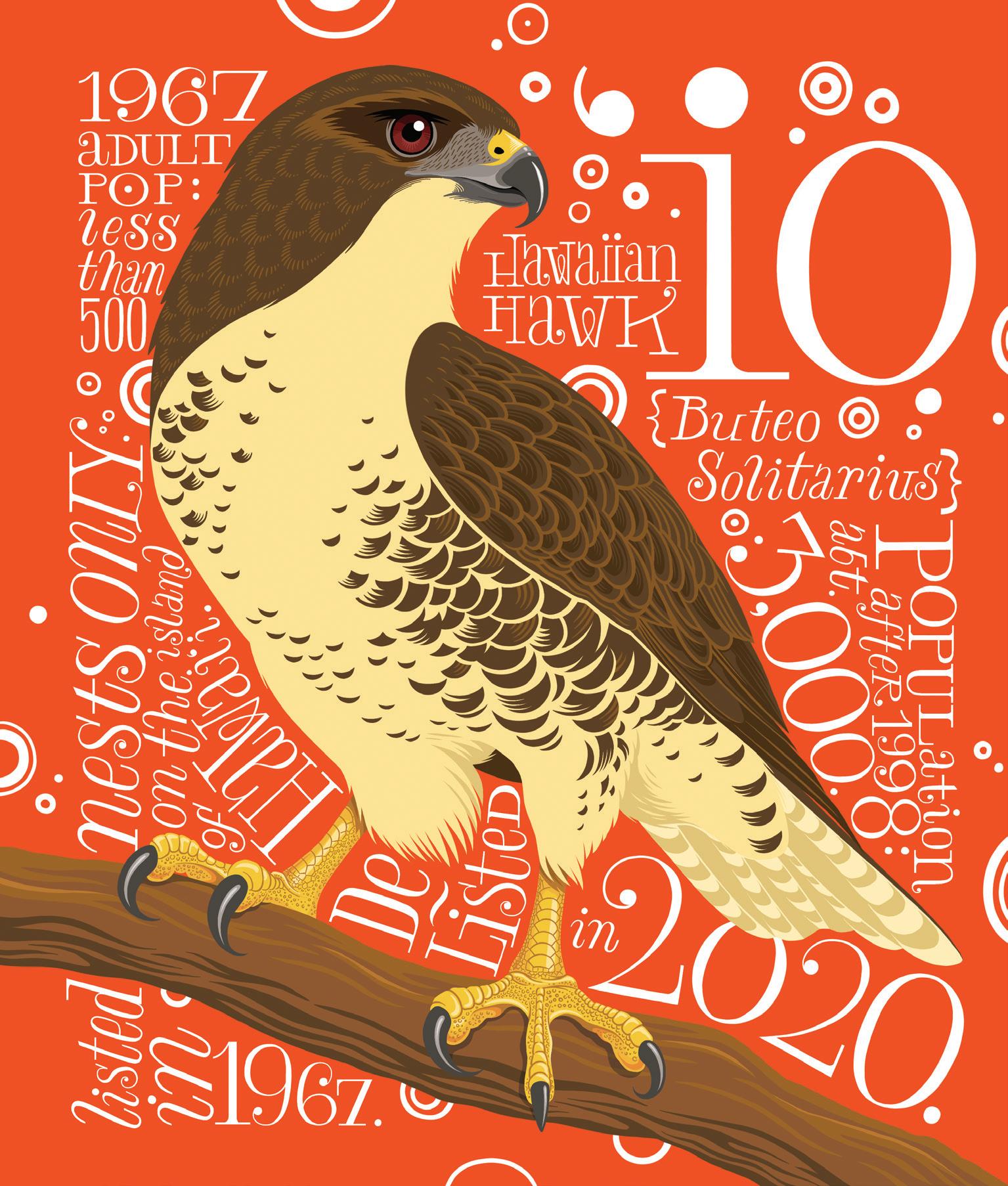

“HAWAIIAN HAWK”

Buteo solitarius

Nests only on the Big Island of Hawai'i.

Adult population in 1967: less than 500.

Population after 1998: about 3,000.

Listed as endangered in 1967.

Delisted in 2020.

184 ' IO

Afterword

ALLEN CRAWFORD

I’ve always viewed the world through a lens of water. I was born in the mountains of eastern Kentucky, but I’ve spent most of my life exploring the watery mazes of southern New Jersey. The town where I grew up overlooks a large bay enclosed by salt marshes and an eroding strand of barrier islands, all of which shelter the mainland from the full force of the North Atlantic.

Living at the edge of the ocean sometimes revealed the paradoxical nature of our world. I watched bridges, bulkheads, and docks battered by ferocious waves that simultaneously cradled delicate jellyfish in their swells. The ocean also revealed to me how the apparent chaos of an elemental force can contain a deep and abiding order. That order, if not interrupted, will form patterns. Like sea foam. Or kelp. Or us.

Back on the land, my hometown taught me harsh truths about human selfishness, shortsightedness, and greed. The thickets of oaks, pines, and briars around my old neighborhood where I regularly found huge yellow garden spiders, box turtles, and wood nymph butterflies were swallowed by development decades ago. It’s a cruel irony that the meadow where I spent many summer days studying butterflies and insects—some so strange and colorful that I still wonder if I’d dreamt them—is now a garden center. I’m sure that some of you reading this are haunted by a lost meadow of your own.

I moved inland many years ago. Time has taken its inevitable course, and I’m beginning to resemble my battered kayak. After spending years drifting through the eerie bogs and winding rivers of the New Jersey Pine Barrens, I rarely feel a strong desire for the harsh clamor of the ocean.

189

The New Jersey Pine Barrens is the largest remaining tract of wilderness between Washington, DC and Boston. 1.1 million acres of pine forests and cedar swamps blanket the acidic, nutrient-poor coastal plain, all of which is steeped in one of the cleanest remaining freshwater aquifers in the US. The Pine Barrens are home to beautiful orchids, sparkling damselflies, carnivorous plants, dazzling snakes, fish-eating spiders, and prudent turtles. Several rare and threatened species of plants and animals have made the Pine Barrens their main stronghold, while a few species living there are found nowhere else on Earth.

Once slated to become a massive airport hub for the Northeast Corridor, the establishment of the Pinelands National Reserve in 1978 was nothing short of miraculous. It was saved because of a single book: The Pine Barrens by John McPhee. The book was read by Brendan T. Byrne, the governor of New Jersey, who made it his mission to set aside this unique ecosystem for posterity.

The Pine Barrens, with its acidic soils, forest fires, centuries of clear cutting, intrusions of small industries, and surrounding overdevelopment, has proven itself to be incredibly resilient. Time and again, the forests have grown back and swallowed scores of farms, small towns, iron forges, glassworks, and other manmade disruptions. In some areas, the Pine Barrens looks much like it did 300 years ago.

There are many persistent challenges, but the Pine Barrens has been a remarkable success when compared to many other threatened wild areas in the rest of the country. But that can easily change. Despite its protected status, the Pine Barrens remains threatened by neglect, corruption, industry, and overdevelopment. The brazen abuse of law, good sense, and decency over the past decade in South Jersey has shown that even our officially protected wild places are still vulnerable.

What gives me the most hope—and this is true everywhere—are the volunteers. I’m as much a part of the problem as anybody, but like the other volunteers I try to help where I can. I sometimes give guided tours. I’ve surveyed and established populations of threatened plants. I’ve patrolled local roads to rescue crossing turtles in late spring. I’ve helped clean up illegal dumping sites and have set up barriers to prevent off-road vehicles from churning up habitat where rare tree frogs breed. I’ve hidden in underbrush and called in rangers when off-roaders have illegally intruded sensitive areas. I’ve also joined the state’s volunteer venomous snake response team.

190

But lugging trash and building barricades is easy compared to watching helplessly as painted turtles and snapping turtles are crushed before I can reach them. Finding muddy pits that only hours before were clear ponds full of water lilies, tadpoles, and frogs always gives me a sick feeling, too.

Refusing to look the other way is personally taxing, but crucial to conservation. It’s why this book now rests in your hand. It’s also why the species in this book have survived this long. The naturalists, advocates, rangers, and scientists who study and protect imperiled species should be admired for choosing not to look away and willingly signing up for what is often a dirty, tedious, thankless job. This book is partially dedicated to them.

Because I too didn’t want to look the other way, I was compelled to create a series of illustrations devoted to extinct or endangered wildlife. After discussing the idea with the team at Tin House, we decided on an illustrated book that not only paid tribute to the species in the series, but also commemorated the fiftieth anniversary of the Endangered Species Act of 1973.

As I did with my previous illustrated book, Whitman Illuminated, I retreated to my cold basement for a year, this time to illustrate eighty-two species in full color. I researched each species as I went, which took an emotional toll at times. The pages, with their full incorporation of hand-drawn calligraphy, were designed to be more like pantheistic icons, banners, or emblems rather than conventional likenesses. This approach was in keeping with the devotional conceit of the book, and had the added virtue of being more practical to produce as a series. Using the app Procreate sped up my workflow, which enabled me to make much more detailed images than I otherwise could have.

Among the illustrations in this book are famously successful species like the bald eagle and American alligator, both of which have been delisted due to their recovery. Also in this book are species new to the list whose futures remain uncertain. This book aspires to make readers more aware of the plight of many lesser-known endangered species, many of which are endemic to a single location and are teetering on the brink of extinction. I shudder to imagine what the fate of all these species might have been if the Endangered Species Act never existed.

The living world isn’t sentimental: It can be quite cruel. But that brutality has given rise to so much beauty that commands our reverence. In my sappier moments

191

I imagine my boots, paddles, and pen as instruments of prayer. They’re the tools I use to help others perceive and revere the web of life from which we’ve emerged, and to which we’ll return. It may be grandiose and silly, but it gives me a useful ideal to strive for.

My hopes for this book are threefold. My first hope is that this collection of emblems has sufficiently dignified all the species it represents. My personal hope is that this book might help bring some added attention to these imperiled species. My great hope is that this book will inspire readers to don their own boots and declare their own promise to serve the wild places remaining on this ancient, strange, and precious world. It’s how each of us might earn the stunning view of the cosmos we now enjoy before we’re compelled to climb back down the tree of life to nourish its roots again.

Allen Crawford

192

SPECIES INDEX

A

Alabama Cavefish, 130-131

Alameda Whipsnake, 146-147

Aleutian Cackling Goose, 38-39

American Alligator, 102-104

American Burying Beetle, 148-149

American Crocodile, 90, 92-93

American Peregrine Falcon, 90-91

AMPHIBIANS

California Tiger Salamander, 104-105

Oregon Spotted Frog, 110-111

Pine Barrens Tree Frog, 100-101

Ozark Hellbender, 22-23

Texas Blind Salamander, 124-125

Atlantic Salmon, 54-55

Atlantic Sturgeon, 64-65

BEARS

Grizzly Bear, 12-13

Louisiana Black Bear, 108-109

BEES

Rusty-Patched Bumblebee, 138-139

Western Bumblebee, 18-19

Beluga Whale (Cook Inlet Population),

48-49

Big Sandy Crayfish, 14-15

BIRDS

Aleutian Cackling Goose, 38-39

American Peregrine Falcon, 90-91

Bald Eagle, 176, 178-179

Black-Capped Vireo, 170-171

Brown Pelican, 32-33

California Condor, 14, 16-17

Golden-Cheeked Wood Warbler, 162-163

Greater Sage-Grouse, 150-151

BBald Eagle, 176, 178-179

BATS

Lesser Long-Nosed Bat, 70-72

Ozark Big-Eared Bat, 160-161

Hawai‘i ‘Akepa, 176-177

Interior Least Tern, 112-113

‘Io, or Hawaiian Hawk, 184-185

Ivory-Billed Woodpecker, 106-108

195

Kirtland’s Warbler, 166-167

Nēnē, or Hawaiian Goose, 46-47

Northern Spotted Owl, 156, 158-159

Piping Plover, 50-51

Red-Cockaded Woodpecker, 182-183

Southwestern Willow Flycatcher, 80-81

Whooping Crane, 98-100

Wood Stork, 132-133

Blackburn’s Sphinx Moth, 166, 168-169

Black-Capped Vireo, 170-171

Black-Footed Ferret, 136-137

Bog Turtle, 94-95

Brown Pelican, 32-33

BUTTERFLIES AND MOTHS

Blackburn’s Sphinx Moth, 166, 168-169

Florida Leafwing Butterfly, 174-175

Monarch Butterfly, 150, 152-153

C

California Condor, 14, 16-17

California Tiger Salamander, 104-105

Canary Rockfish, 44-45

Choctawhatchee Beach Mouse, 126-127

Columbian White-Tailed Deer, 164-165

Concho Water Snake, 118-119

D

Devils Hole Pupfish, 82-83

Dwarf Bear-Poppy, 18-19

F FISH

Alabama Cavefish, 130-131

Atlantic Salmon, 54-55

Atlantic Sturgeon, 64-65

Canary Rockfish, 44-45

Devils Hole Pupfish, 82-83

Oregon Chub, 114-115

Scalloped Hammerhead Shark, 52-53

Steelhead Trout, 60-62

White River Springfish, 74-75

Florida Leafwing Butterfly, 174-175

Florida Panther, 86-87

FROGS

Oregon Spotted Frog, 110-111

Pine Barrens Tree Frog, 100-101

G

GEESE

Aleutian Cackling Goose, 38-39

Nēnē,or Hawaiian Goose, 46-47

Golden-Cheeked Wood Warbler, 162-163

Gray Whale, 58-59

Gray Wolf, 180-181

Greater Sage-Grouse, 150-151

Green Sea Turtle, 42-44

Grizzly Bear, 12-13

H

Hawai‘i ‘Akepa, 176-177

Hawksbill Sea Turtle, 62-63

Hine’s Emerald Dragonfly, 118, 120-121

EElkhorn Coral, 66-67

Humpback Whale, 30-32

196

I

INSECTS

American Burying Beetle, 148-149

Rusty-Patched Bumblebee, 138-139

Western Bumblebee, 18-19

Blackburn’s Sphinx Moth, 166, 168-169

Florida Leafwing Butterfly, 174-175

Hine’s Emerald Dragonfly, 118, 120-121

Monarch Butterfly, 150, 152-153

Interior Least Tern, 112-113

‘Io, or Hawaiian Hawk, 184-185

Island Night Lizard, 142-143

Ivory-Billed Woodpecker, 106-108

K

Kirtland’s Warbler, 166-167

L

Lake Erie Water Snake, 96-97

Lesser Long-Nosed Bat, 70-72

Louisiana Black Bear, 108-109

M

Mojave Desert Tortoise, 72-73

Monarch Butterfly, 150, 152-153

Monito Gecko, 40-41

N

Nēnē, or Hawaiian Goose, 46-47

New Mexican Ridge-Nosed Rattlesnake, 76, 78-79

North Atlantic Right Whale, 34-36

Northern Sea Otter, 36-37

Northern Spotted Owl, 156, 158-159

O

Orca (Southern Resident Killer Whale), 54, 56-57

Oregon Chub, 114-115

Oregon Spotted Frog, 110-111

Ozark Big-Eared Bat, 160-161

Ozark Hellbender, 22-23

P

Pine Barrens Tree Frog, 100-101

Piping Plover, 50-51

Plymouth Red-Bellied Turtle, 128-129

R

Red-Cockaded Woodpecker, 182-183

Red Wolf, 86, 88-89

REPTILES

Alameda Whipsnake, 146-147

American Alligator, 102-104

American Crocodile, 90, 92-93

Bog Turtle, 94-95

Concho Water Snake, 118-119

Green Sea Turtle, 42-44

Hawksbill Sea Turtle, 62-63

Island Night Lizard, 142-143

Lake Erie Water Snake, 96-97

Mojave Desert Tortoise, 72-73

Monito Gecko, 40-41

New Mexican Ridge-Nosed Rattlesnake, 76, 78-79

Oregon Spotted Frog, 110-111

Plymouth Red-Bellied Turtle, 128-129

Rusty-Patched Bumblebee, 138-139

197

S

SALAMANDERS

California Tiger Salamander, 104-105

Ozark Hellbender, 22-23

Texas Blind Salamander, 124-125

Santa Rosa Island Fox, 144-145

Scalloped Hammerhead Shark, 52-53

SNAKES

Alameda Whipsnake, 146-147

Concho Water Snake, 118-119

Lake Erie Water Snake, 96-97

New Mexican Ridge-Nosed Rattlesnake, 76, 78-79

Sonoran Pronghorn, 76-77

Southwestern Willow Flycatcher, 80-81

Spruce-Fir Moss Spider, 20-21

Steelhead Trout, 60-62

Steller Sea Lion, 28-29

U

Utah Prairie Dog, 140-141

VVenus Flytrap, 116-117

Virginia Northern Flying Squirrel, 172-173

WWest Indian Manatee, 26-28

Western Bumblebee, 18-19

WHALES

Beluga Whale (Cook Inlet Population), 48-49

Gray Whale, 58-59

Humpback Whale, 30-32

North Atlantic Right Whale, 34-36

Orca (Southern Resident Killer Whale), 54, 56-57

White River Springfish, 74-75

Whooping Crane, 98-100

TTexas Blind Salamander, 124-125

Tulotoma Snail, 122-123

TURTLES AND TORTOISES

Bog Turtle, 94-95

Green Sea Turtle, 42-44

Hawksbill Sea Turtle, 62-63

Mojave Desert Tortoise, 72-73

Plymouth Red-Bellied Turtle, 128-129

WOLVES

Gray Wolf, 180-181

Red Wolf, 86, 88-89

Wood Bison, 156-157

Wood Stork, 132-133

198