The heroes of Coweta County – those law enforcement officers, fire rescue and emergency responders, and 911 dispatchers who work in concert to help us in times of dire need –are not beyond need themselves.

While highly trained in their respective professions, these public service workers sometimes are taken aback by the tremendous stresses of jobs that put them on the front lines of life and death situations.

Fortunately, in Coweta, administrators at the local police departments, sheriff’s office, fire rescue and 911 recognize the potential trauma their employees face. To help these helpers, they put in place procedures and personnel to alleviate and manage

stress for those whose job is undeniably wracked with stressors.

As part of this magazine’s Death (and Life) Issue, the 2025 edition of Heroes Among Us seeks to explore the lives of local heroes who never know when they leave for work in the morning what tragedy they may encounter before their shift ends. Not knowing, they head out the door anyway to a job that has the potential to save lives – or put their own lives in harm’s way.

We recognize this, and we thank you from the bottom of our hearts for what you do. You truly are our heroes.

Jackie Kennedy, Editor Newnan-Coweta Magazine

Written and Photographed by JEFFREY CULLEN-DEAN

Gasoline brings back memories for Newnan Police Captain Jody Stanford.

Two similar incidents from his job as a police officer come to mind when he fills up his car. He’s never talked about them with his wife, but she knows there were things related to gasoline that happened at work. They both involved self-immolation.

Stanford watched a man douse himself with five gallons of gasoline and light a fire. From the waist up, he was on fire, according to Stanford.

Officers made attempts to talk the man down, but it didn’t work. Stanford kicked the man to the ground to put the fire out, and the man survived. The second incident also involved a suicide attempt.

Stanford and other officers were tracking the man’s vehicle because he had left a note.

By the time Stanford arrived, the man had filled the inside of his car with gasoline and lit it.

“When I pulled up to him, he’d already done it,” Stanford says. “That stays with me.”

Law enforcement officers (LEOs) seldom speak with their loved ones about the grief and trauma that results from their jobs, according to Stanford. Instead, he says, they generally prefer to talk to one another about the difficult incidents that weigh on their minds.

Vehicle fatalities were the first experiences with job-related deaths for Senoia Police Chief Jason Edens and Assistant Police Chief Steve Tomlin.

“It was five fatalities on one vehicle and that was in 1993,” Edens says. “Three of them were children. I was the first one on the scene. You never forget the first one. It’s just something that sticks with you.”

At the end of his first shift as a police officer is when Newnan Police Chief Brent Blankenship watched someone die. He was working the night shift, and it happened about 5 a.m. A man had been stabbed to death.

“I was 22 years old, and he passed right there,” Blankenship says.

“It’s easier to speak with someone on shift because they’re going to understand what you’re going through,” says Coweta County Sheriff’s Office Sgt. Brittany Doss. “A lot of them have been through and witnessed the same things we have.”

In her 10-year career, Doss says she’s seen infant and elderly deaths, has been a part of two officerinvolved shootings, and worked the night the sheriff’s office lost deputy Eric Minix in a 2024 wreck during a high-speed chase. She was also present last year at a fatal house fire that claimed the lives of six people, including a child she had tried to resuscitate.

Considering job experiences like these, compartmentalizing is key to the job, according to Doss. She says that after she responds to an incident, she may need to step away in order to keep her composure. About five years ago, she spent several hours on the scene of a child’s death. She recalls crying afterward, and she considered leaving the profession.

“But after I got that out, I said, ‘It’s time to go to the next scene,’” she recalls. “This job makes you kind of numb about everything because we see so much. You have to be able to separate your feelings. If you get yourself wrapped up into it, it’s going to eat you alive.”

Doss says she doesn’t remember her first encounter with death on the job. Neither does Sheriff Lenn Wood, but he thinks it was most likely an infant death scene. For Wood, the most difficult incidents on the job are when children are involved.

Events following that death were unceremonious, Blankenship recalls. He went home and tried to get some sleep. He came back to work the next day and completed paperwork for the incident. At the time, the culture among LEOs didn’t encourage discussing on-the-job trauma. It was viewed as a sign of weakness, Blankenship says.

Today, law enforcement agencies have peer support groups for officers to turn to after traumatic incidents. These groups include officers trained to provide trauma counseling.

After the fatal house fire last year, CCSO coordinated its peer support groups and brought in outside counselors for everyone who’d been on the scene.

About five years ago, the Senoia Police Department lost an officer to suicide. Counselors were made available for the other officers. Edens and Tomlin foster an open-door policy.

“If any employee is having a problem at work or home and talks to us, they don’t have to worry about their job being on the line,” says Tomlin.

“I’ll share stories from my past or things I have messed up on,” Eden adds.

An officer’s suicide in 2019 also encouraged mental health services at the Newnan Police Department. The department’s previous chief, Buster Meadows, planted the seeds for mental health care at the department, according to Stanford, and Blankenship pushed it further when he took over in 2021.

Wood encourages supervisors at CCSO to reach out if they see behavioral changes in deputies or jail personnel. He says he wants staff to support one another, to watch out for one another and pay extra attention if someone has clashes between their personal life and professional life, such as a divorce, financial trouble or death in the family.

After a deputy sought a counselor, Wood says he saw how much it helped him, so he encourages his deputies to seek counseling or to reach out to friends and family. Officers do their best to show compassion and support when breaking bad news to victims’ families, which was critical for Coweta deputies last year when Deputy Eric Minix was killed. Sheriff Wood, along with deputies, went to Minix’s home to tell his wife Trina. When she came to the door and saw him, she knew it wasn’t good.

“I didn’t have to tell her anything,” says Wood. Afterwards, he assembled on- and off-duty deputies to discuss the incident.

“We said, ‘Okay, we just need to talk about it,’” the sheriff recalls. “Some of them wouldn’t say anything, but we all eventually got to talking and laughing, [remembering] good things about Eric. I think that helped a lot… I think it helped us all.” NCM

Berkshire Hathaway Home Services

Coweta-Newnan O ice

1201 Lower Fayetteville Road 770-254-8333 • Coweta.BHHSGeorgia.com

Carriage House

Country Antiques, Gifts, Collectibles

7412 East Highway, Senoia 770-599-6321 • carriagehousesenoia.com

City of Hope

600 Celebrate Life Parkway, Newnan 833-282-2285 • cancercenter.com

Coweta Charter Academy

K-8 Tuition-Free School

6675 East Highway 16, Senoia cowetacharter.org

Odyssey Charter School

14 St. John Circle, Newnan 770-400-1000 • piedmont.org

Piedmont Newnan Hospital

745 Poplar Road, Newnan odysseycharterschool.net

The Salvation Army

Newnan Service Center

670 Je erson Street, Newnan 770-251-8181 • facebook.com/TSANewnan

Southern Crescent Women’s Health

Locations in Newnan, Fayetteville & Stockbridge 770-991-2200 • scwhobgyn.com

Wesley Woods

2280 Highway 29, Newnan 770-683-6833 • wesleywoods.org

White Oak Golden K Kiwanis Club

Newnan • whiteoakgoldenk.org

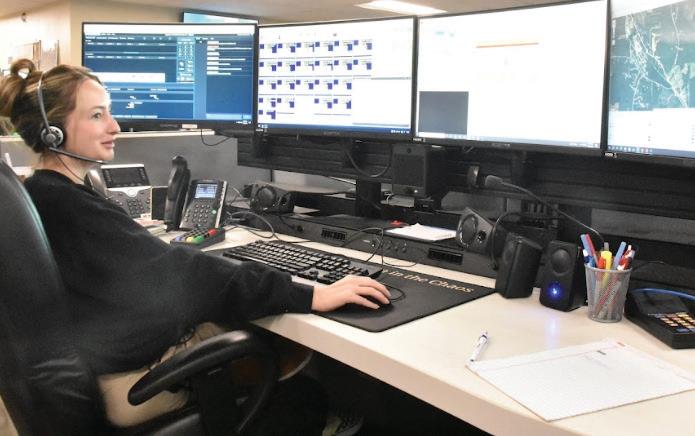

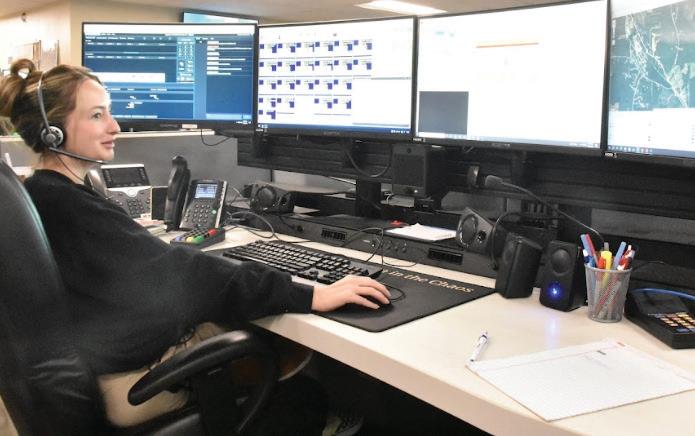

Calling 911 is often a daunting task, but the team in charge of the phones for Coweta County’s 911 services do everything they can to make difficult situations as easy as possible.

Behind the nameless voices are regular members of the community – mothers, fathers, neighbors – but when the headsets are on and the calls are coming in, a switch is flipped. They become the front line of emergency response in Coweta. It’s a responsibility they don’t take lightly.

Answering the call

“You’ve got to be resilient,” 911 Communications Officer Starr Gomez says. “You hear all these things, and you have to remember, it’s not you. You have to be grounded. You have to be able to be there for that person.”

At Coweta County’s 911 Administration Office, Gomez answers incoming 911 calls, gathers caller information, and dispatches emergency services all across the county.

She started the position two and a half years ago after moving to Newnan from Brooklyn, N.Y. When she saw the job description on the County’s website, she was intrigued.

“I grew up in the ’90s, and that’s when the show ‘COPS’ was all the rage, and all the little kids wanted to be the offi cer,” Gomez says. “I wanted to be the lady that he’s talking to. I wanted to be the 911 operator.”

Gomez joined the team, but before taking any calls, she needed the proper training. For the fi rst fi ve to six weeks, new employees don’t take calls. Instead, they learn the fundamentals: how the phone systems work, how to respond to high stress calls, and how to locate callers. Th ey complete multiple certifi cations along the way.

“I can walk someone through CPR,” Gomez says. “I can walk someone through bleeding control measures or how to administer naloxone.”

Once the proper training and certifi cations are completed, communications offi cers are assigned a “best friend” who accompanies them for training for the next few months. New recruits take calls under the supervision of their best friend and the communications training offi cer to ensure proper protocol is followed. After their supervisory period is complete, communications offi cers operate their stations alone, but the job remains a team eff ort.

A minimum of 10 people are always in the call room, including one supervisor, a floor supervisor, two assistant supervisors and a training officer, according to Gomez.

“Even if you’re the one taking a phone call, as a team, there’s always someone who can call another agency if we need them,” she says. “There’s always someone who can help you if you’ve never had that kind of situation, especially if you’re a newer dispatcher.”

The 911 shifts are 12 hours long. Communications officers alternate between 36- and 48-hour weeks, according to Assistant 911/EMA Director Nic Burgess.

Due to the nature of their job, communications officers often experience a lack of closure with their calls. Once the proper authorities are dispatched, many operators never find out what happened next.

“Sometimes I don’t want to know, especially if it’s a hard call,” Gomez says. “But there are days I just hope that person’s okay.”

Dealing with the lack of closure and other stressors can easily overwhelm, according to Gomez, who manages the stress through self-care techniques, like talking with her fiancé or working at hobbies. She’s on the night shift, where the call load is generally smaller than during the day, but the team is still required to be on high alert. On average, the night shift deals with 75-100 calls, while the day shift answers closer to 300 calls on a busy day. With so many calls of varying severity coming in, communications officers must focus on multiple things at once.

“You have to be able to multitask,” says Gomez. “It goes really fast, but it’s almost as if time slows down when you’re on a call, especially if it’s a high priority call. You’re going to get life or death calls. You can prepare for the worst, and you get the least, or the opposite.”

The unknown aspect is a blessing and a curse, says Gomez, but she credits her training and the team dynamic for making the stress more manageable. Meeting those high-stress, life-or-death calls doesn’t get easier, though, she says: “You just get better at doing it.”

A pivotal piece of the operations at Coweta’s 911 Administration is their Peer Support Team. When the department experiences a particularly stressful or potentially traumatic situation, the team addresses those issues and provides relief to employees.

Team members complete a 40-hour training course and are required to be recertified after three years,

according to Peer Support Team Coordinator Cindy Eady. At least two team members are present each shift.

“In peer support, we are trained to look for certain things, to know when somebody’s in a bad spot, and then we can give them the right resources, whether it’s an employee assistance program counseling or a crisis counselor,” Eady says. “We are very lucky that our top down is very much watching out for our mental health.”

An operator who’s dealt with a difficult call is allowed to step out and decompress before answering more calls. For wide-scale incidents, the entire department goes through a debriefing and defusing process where those who were affected by the incident talk about their experiences.

“We deal with traumatic events,” says Eady. “We deal with all the things that happen in life – the stresses and anxiety, the job demands, all of it. We try to either talk you through things or get you the help you need.”

The team at Coweta County’s 911 Administration is all about maintaining a healthy work environment while providing the best possible emergency response.

“A lot of people don’t know who we are, but we’re your neighbors, we’re your cousins, we’re your aunts, your uncles,” says Gomez. “We’re here to help you. We wouldn’t be doing this job if we didn’t want to help our community.” NCM

Written and Photographed by WILL THOMAS

Death brought Emergency Medical Services (EMS) Captain David Pickett new life. In 2007, his father passed away. Ten days later, he lost his uncle. But instead of letting loss control his life, Pickett used it as inspiration.

“I had a moment of a lot of intense death all within two weeks,” says Pickett. “I had to step back and go, ‘What am I going to do? What am I going to be known for?’ I wanted to do something to help other people. I was told I needed to be in EMS. And there I went, and I love it every single day. I wake up every morning and see what kind of fires I can put out.”

As an EMS captain in Coweta County’s Fire Rescue, Pickett’s “fires” can vary drastically – from dealing with cardiac arrests to delivering newborn babies. Such a high-stakes field can often lead to stress, anxiety, and even trauma, but the team at Coweta’s Fire Rescue makes a conscious effort to deconstruct the stigma surrounding their occupation.

“We’re fighting hundreds of years of stigma in mental health with this. The last thing we want to do is ask for help. We’re the ones who get asked for help. We are the solvers,” says Pickett. “In the last 20 years or so, the county has really amped it up to where it’s okay to talk or ask for help.”

Before working with EMS, Pickett acquired a psychology degree, something he says comes in handy in his line of work when looking out for his coworkers, like firefighter paramedic Kyle Byrom and advanced emergency medical technician (EMT) Trevor Greene. Between the three of them is years of experience in responding to medical emergency calls throughout Coweta. But before they can ride in the ambulance, EMTs and paramedics must complete more than 200 hours of training per year, according to Greene.

“The fire department hosts classes and teaches continuing education for EMS,” Byrom adds. “We have 40 hours of continuing education units we have to get every two years to maintain our certification as an EMT or paramedic.”

Paramedics and EMTs are trained for the most severe of situations, so when the call comes, they’re prepared for anything.

“I responded to a woman giving birth and helped deliver a baby, then I came back here and responded to a fatality accident,” says Byrom. “It was whiplash. But I can tell you when you’re there, you just fall back on your training. This is what we do, and then you kind of deal with it afterwards.”

Dealing with it afterwards isn’t always easy. That’s why the department takes steps to ensure its members know they’re not alone – and that support is always available for them. When the team experiences a particularly difficult call, they make sure to communicate how they’re feeling with each other.

“It seems like for most incidents, just getting together and talking about it with people who were either there or have been through similar situations seems to diffuse a lot of the stress,” Byrom says.

Department members are trained to recognize behavior patterns and pick up when a coworker isn’t acting normally. If an individual seems to be struggling, coworkers can step in and recommend the department’s peer support group, which gives them the opportunity to talk with state-provided, licensed mental health professionals.

The department also offers employee assistance programs with mental health resources specially tailored to individuals in public safety.

The most important thing, according to Pickett, is creating a safe environment where help is only one conversation away.

“We don’t want to go home and find out that our friend killed himself because he was too proud to talk,” Pickett says. “The best thing you can do is let them know that your door is open. Talking about it is going to be the best answer. That’s where it’s going to start. I’m a captain, but I can still walk into the chief’s office any day of the week, anytime, and go in there and blow off steam. And that’s where we have to be, no matter our rank.” NCM

With deep gratitude for the men and women who serve in the City of Newnan’s Police and Fire Departments, THANK YOU for keeping our

community safe.