cul metamorphosis

Colofon Editor’s note

Independent anthropological magazine

Cul is connected to the Cultural Anthropology and Development Sociology department at the University of Amsterdam.

Editors in Chief: Alex Dieker

Morrigan Fogarty

Graphic Design: Alžbeta Szabová

Image Editors: Carme Ferrando Soriano

Helena Peters

Alžbeta Szabová

Text Editors: Eduardo Di Paolo

Iris van der Goes

Daria Nita

Mia Grassi

Neve Faulconer

Cover: Alžbeta Szabová

Cul magazine is always searching for new aspiring writers. The editorial team maintains the right to shorten or deny articles. For more information on writing for the Cul or advertising possibilities, email cul.editorial@gmail.com

Printer: Ziezoprint

Prints: 200

Printed: June 2025

ISSN: 18760309

Cul Magazine Nieuwe Achtergracht 166 1018 WV Amsterdam cul.editorial@gmail.com

Follow us on Instagram and check out our website! @culmagazine http://culmagazine.com

Dear Readers,

Things are changing. Yes, you’re right: this shallow cliché belongs nowhere near pages touched by anthropological fingers, but here we are. The world is in a moment of upheaval, and so are we. The academic year has come to a close, those international students of an Amsterdam persuasion have returned home, and Autumn’s cool promise is already creeping into our post-midsummer minds. Many are going, others are staying put. And all of us are changing—along with the ‘things’.

This third edition of Cul Magazine’s thirtysecond year explores metamorphosis in all its glory. We are proud to present to you insightful articles and beautiful imagery highlighting the ever-shifting contours of student life, of history and warfare, of Americans both hillbilly and papal, and of Amsterdam’s most despised architectural bouts of genius. Within these pages exists something for you, who is going through some sort (small or seismic) metamorphosis. This edition is for the leg shavers, the freaks of nature, the privileged, the queer necromancers, those concerned with the state of food forestry and urban greening in the Netherlands, and to the aspiring academics pondering over the usage of “I” or “we”.

As our team of editors, writers, and artists begins its own yearly metamorphosis, thanks are due. To everyone who made this another year of deepening anthropological knowledge, tearing it apart, and reassembling it into thousand-word articles tucked into Cul's corners. Thank you to all members of the team, to those wonderful guest writers, and to you, the Reader, for making this a year to remember—cliché intended.

Best

Wishes, Morrigan Fogarty Alex Dieker

GUEST ARTICLE

The Grime

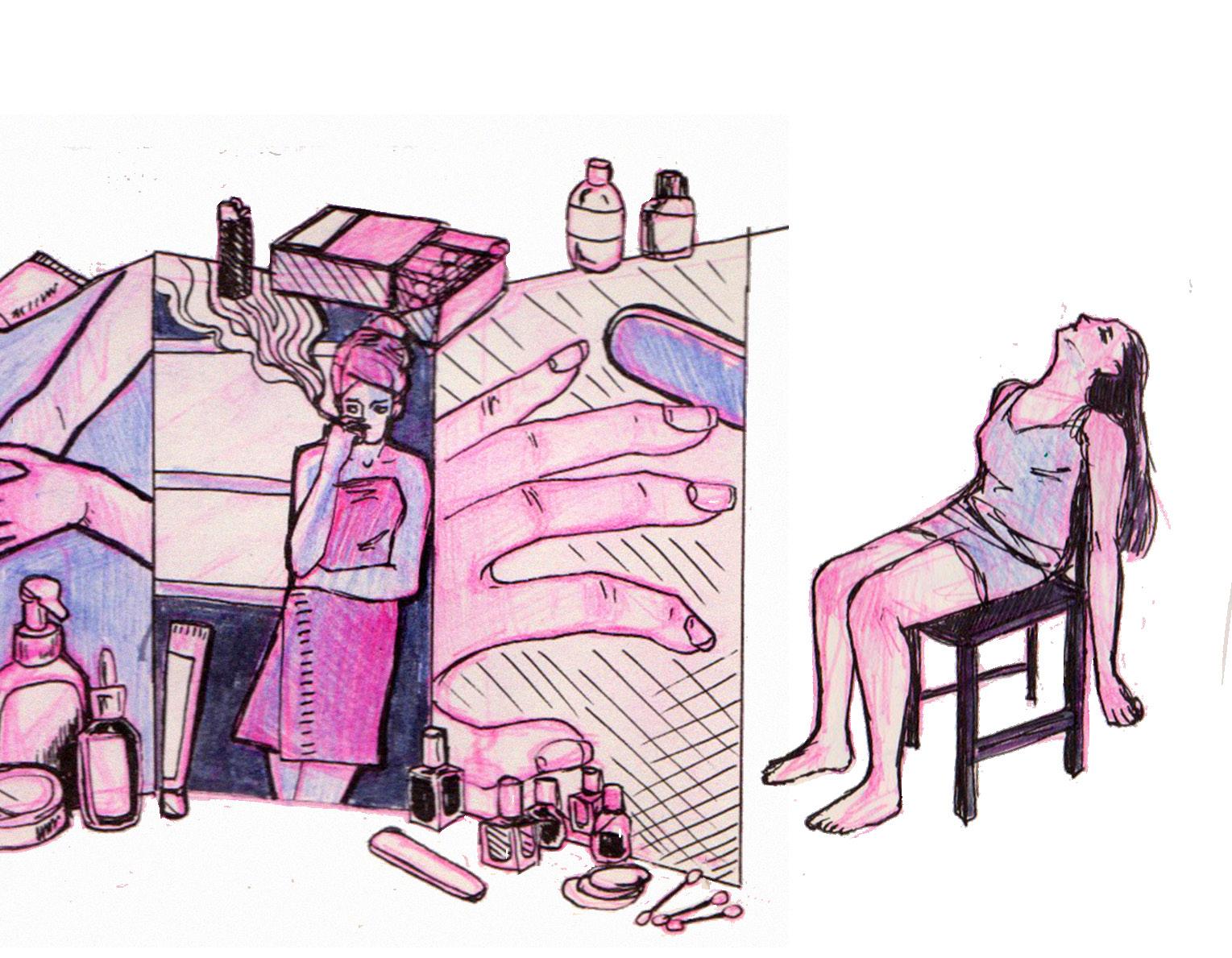

Text Gayatri Srikant Image Alžbeta Szabová

Afew months ago, I had the honor of receiving The Grand Tour of my beloved’s Steam account. As a non-gamer, my jaw dropped at the sheer amount of time he spent on this platform. The game he had just paused was Europa Universalis IV, where one plays as a nation-state to explore alternate histories from 1444-1821. A staggering 400 hours had gone into this game, a fact that flooded me with awe. This man had spent 400 hours learning about global history, political and economic strategy, and the leadership styles and personalities of the chiefs, dukes, kings, and emperors that shaped our present. Good practice for a politician in spe, no doubt about it. I, on the other hand — a fellow aspiring changemaker— hadn’t. And so, faced with a gaping knowledge deficit, awe turned into jealousy, which turned into fear. I had also spent my 400 hours, just unknowingly. That begs the question, where did my 400 hours go?

Vignette:

7 pm on a Friday, time for the infamous ‘everything shower’. Shave my beard, my mustache, pluck my brows. Head into the shower, shampoo twice, condition once, shave the rest of my body, bodywash, scrub, leave-in hair mask. Exit the shower, skincare, blackhead extraction, body lotion, curly girl routine: section, curl cream, gel one, gel two, squish squish, section again, five times over. Diffuse. Exit the bathroom, cigarette break,, demolish my

cuticles, polish my nails, and with the last stroke, sigh. It’s done. I am cleansed, I am once again, a woman.

In bed, I got to thinking. This man is miles ahead while I’m still contemplating running shoes! I know this is not all my fault. As De Beauvoir writes “one is not born, but rather becomes, a woman”; and a woman’s existence in society is conditional on their femininity. The consequence however, 400 hours of political strategy as opposed to 400 hours hunched over my belly, fishing the same ingrown hair out of my happy trail for the nth time, is both an infuriating and humiliating contrast. The truly feminist thing would be to stop caring, get a buzz cut, rock the unibrow, and eventually develop a sense of beauty uniquely my own and of trivial importance. However, after having spent 400 (give or take a zero) hours here, I’ve grown attached to this version of femininity, and parting from it would feel like parting from my womanhood. What then?

I came to Christ. To De Homem Christo to be precise, and as the helmeted prophet (better known as the gold-helmeted legend of the visionary French House band: Daft Punk) hath declared: I worked it harder, better, and faster. Perhaps I could optimise my grooming routines to simultaneously enhance my knowledge bases. It’d be a challenge, but challenge accepted. Step one was to incessantly bathe myself

GUEST ARTICLE

in enriching podcasts. I shunned Emma Chamberlain’s podcast from the everything shower; nothing goes anymore (her podcast is called “Anything G=goes”), and as I did my chores or took my daily commute you could find me listening to the BBC world news, Philosophize This! or De Correspondent, learning all about current affairs, the great Thinkers of history, and the problems of Dutch society. The second step was to eliminate all time I spent “dillydallying”. No more bedrotting, no more taking hours to boot up, and definitely no more maladaptive chain smoking hour after work. Upgrades people, upgrades! (A quote you might know from the animated film “Robots” https://amp. knowyourmeme.com/memes/upgrades-people-upgrades) Lightning speed ahead- we have a lot of catching up to do!

The first few months of this new routine were exhilarating. I was a well-oiled machine, the definition of efficiency, gaining new neural pathways by the second. Lavished with newfound knowledge, I joined in speculations on Camus’s “fifth cycle” at the de Rode Hoed (At event space De Rode Hoed, “Bucketlist Filosofie” is a series where each event explores a famous philosopher. Recommend!), I finally was able to contribute to the discussions of my smartest friends on the place of the individual in mass society, using Karl Popper’s insights on the Open Society, and most importantly, I no longer felt as humiliated and furious as I did that one night. In fact, I felt a winner.

After those initial months however, my brain could no longer handle the sheer amount of input fired at it every day. Every thinker I’d studied blurred into a singular amalgam of contradicting and dizzying thought, devoid of historical context. And because I did nothing with that knowledge—

created nothing, applied nothing—it never became mine to keep. I was exhausted, nay, burnt out.

Gazing upon the dirty dishes, a chairdrobe the size of Mount Everest, and though only visible to myself, eyebrows plucked into the face crack of the century (Drag culture expression meaning “record scratch moment”), I was confronted once more with the shortcomings of the meritocratic ideal. I cannot work hard enough, I can never be woman enough, and I can never catch up, because “the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house”.

But what about my career?

Unable to accept the part of my mixed feelings I labeled “failure”, I got back on my grind, sweeping my floors to the Philosophize This! podcast. The episode on play explored Byung Chul Han’s commentary on the Achievement Society. He argues that psychopolitics —an updated version of Foucault’s biopower— govern the Achievement Society we live in today. The telos of the commodified human being is limitless in modern Neoliberal societies. Thus, the only way to “be enough” (i. e. realize one’s telos) in such a society is through infinite work on the ego. Not only does such an Achievement Society lead to mass egocentrism, but the inevitable burn-out feels like a personal failure to become who I myself set out to be. Well, I’m tired, and I set out to rest. In the wise words of Tricia Hersey (performance artist, activist, and author of the book “Rest is resistance”), rest is resistance.

My dishes, eyebrows, and market value can go fuck themselves. I’m going to watch paint dry.

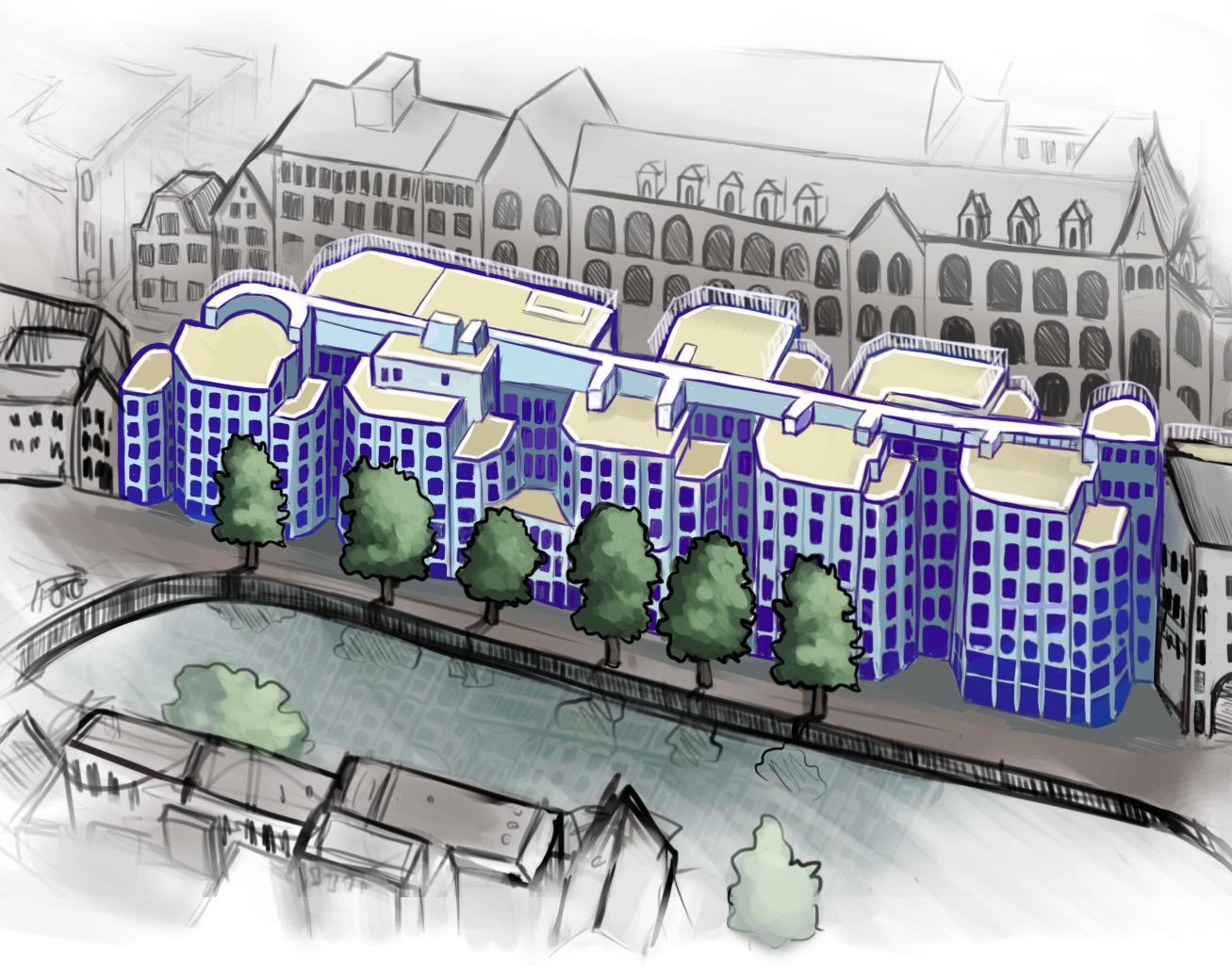

A Eulogy to the PC Hoofthuis

Why We Need Freaks of Nature

Text Audrey Fabri Image Alžbeta Szabová

The PC Hoofthuis is not a conventionally attractive building. A modernist contraption glued on the old world Spuistraat, this UvA library and faculty smells like a beautiful uncanny accident. It has certainly become dead weight to the UvA, however; with the new university library opening next September, its ugly little brother is being phased out of use. The PCH library will be the first

part of the building to go, closing its doors on the 16th of June. Then the whole building will eventually be sold, despite details on potential buyers still shrouded in mystery. With the end now in sight for our dear PCH, I felt a proper eulogy was deserved. So this article will be the first in a twopart series that attempts to do justice to the building and its conversations with visitors. The first volume will aim to

GUEST ARTICLE

convince you that the PCH is irreplaceable. The second will investigate what it's being replaced with, and the UvA's plans to sell the building. The bottom line is this: no matter your (probably vehement) position on the PCH, you don't have to love the building to conclude that it should stay.

Those repelled by our beloved PC see an unfamiliar and strange face in it. The building tests you like a lab rat, challenging your patience and composure. Certain entrances are only found by surrendering to the least convenient route. Not every door is an exit, not every elevator leads to every floor. It seems that if you want to learn the building, you first have to unlearn what you think you know about it. The odd distribution of space is a scandal amongst overworked students, who would rather seek the comfort of the predictable and open study spaces of REC or Science Park than risk wandering through a labyrinth like the PCH. But in a social atmosphere this atomized and immediate, I can only see its weirdness being its greatest strength. Very few buildings are designed to manipulate you into slowing down. Let me explain.

Just like its siblings, the PC Hoofthuis is built on particular assumptions about humans, their needs, and how they act when jumbled together in a semi-public space. To Renè Boer, these elements are the "script," that every building writes, the normative assumptions crawling under its foundations. If the city is a battle site of scripts, every building is waging a constant, silent war with its neighbors over the rival worlds they are built for. For the PC Hoofthuis, this world is defined by our interrelation and mutual acknowledgment as members of a shared social group. While not designed as a community space, architect Theo Bosch carves the building with micro elements that borrow your gaze and lend it to strangers: you peer inside towards the classrooms, where the half-windows expose the lecture halls to passerbys. You also peer outside towards the city, where the windows at ground level confront pedestrians on the adjacent street. This anti-architecture, defined by the spontaneous tightening and loosening of space, demands that you find comfort in the discomfort of conviviality. The PCH sneaks these ideas into its frame like a mom sneaks spinach into a brownie.

In this shedding city, such a building becomes more than just an architectural social experiment. It is also a middle finger to the perfect city that the UvA and (its) business are manufacturing. Going back to Boer, the more buildings are written with similar scripts, the stronger their influence becomes. This is important because neoliberalism is phasing out the unique script of the PCH and other wacky buildings like it.

Picturing contemporary Amsterdam, René Boer talks of a smoothening city, an urban environment metamorphosed

by business interests. If every dimension of human life is a potential market, then every aspect of the city must look friendly enough to attract investment. This commercial rationale deforms the city's facade, fostering architectural beauty standards that fetishize the smooth, clean, predictable, precise, inoffensive, obvious, profitable and controlled. We can look to campuses built after the UvA’s partial privatization as specimens: they hypermaximize the functional and aesthetic value of every spatial inch; every corner is polished and controlled. The script they write is one in which buildings have no responsibility to nudge people out of their comfort zones or remind them subconsciously that they share space with other humans. The more the UvA's spaces start to look like office spaces, the more its students will start to act like office workers, chained to their comfortable little cubicles. This trend at the UvA is a microcosm of the city's ongoing neoliberal adolescence.

With the visual homogenization of streets that were once architecturally biodiverse, we also see the homogenization of acceptable lifestyles. The range of who is allowed in a specific area and what they are allowed to do, becomes slimmer and more suffocating. The city becomes a bubble of bubbles in which wandering, creating, and breathing without the intention to spend money (or make money) become unthinkable anomalies. This is the city that buildings like the PC Hoofthuis are designed to unstitch. These are structures that confuse the corporate world: odd and hard to digest and tricky to wrap our heads around. They were meant for a more public and more curious city than the one we have right now. This is why the PCH is unpopular to the extent it can be scrapped: buildings unsubmissive to the smooth neoliberal style feel uncomfortable and blasphemous. Because they butt heads with the world the UvA is creating, in which its pupils are consumers and the city is the product. Instead, when I walk into the PCH, I am humbly reminded that I'm still only a student. Because as long as it exists, a different city still also exists.

Despite the love I feel in my bones for this concrete mess, the PCH will soon be gone. But its spirit will endure as a protest against the city's discoloration. Against the expectation that space must be immediately understood and categorized. Against the polished, experience-oriented Zuidasization of Amsterdam, against the pressure to label and control time and space. Against the plastic surgery sweeping our spaces and our lives.

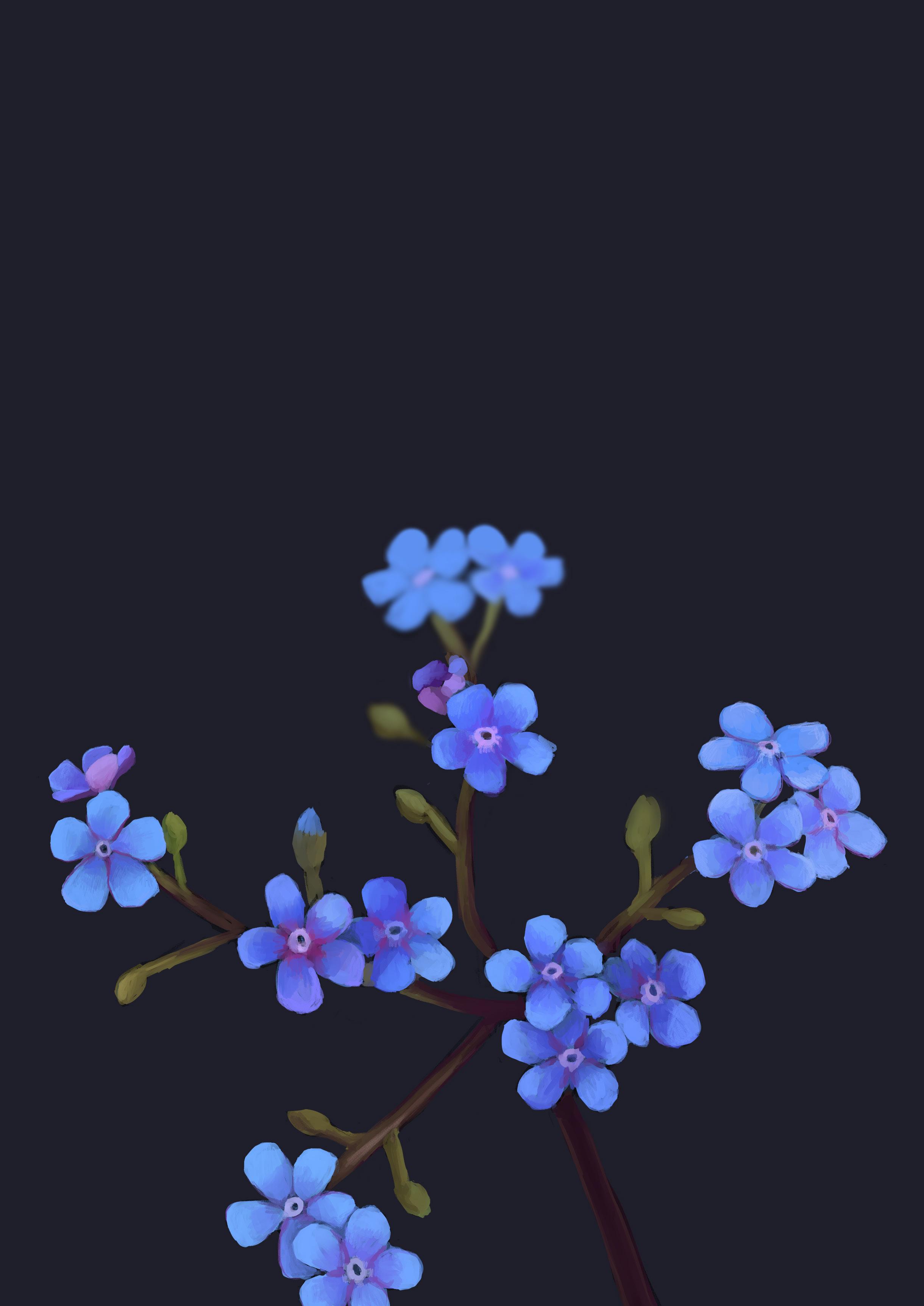

The Priviledge of Transformation

Text & Images Madelene Amber Nitzsche

Spring arrives not with a shout, but with a slow, seductive whisper. Bud by bud, ray by ray, it unspools a symphony of renewal. And yet, alongside this natural metamorphosis, we may find ourselves stuck in a loop of guilt, exhaustion, and a need to “do more.” Funnily, this exasperating spiral makes it easy to forget the elephant in the room. How lucky we are to have the space to contemplate these worries – to even have the time to ponder our own productivity. Overthinking replaces pure action, and the spiral ensues. Welcome to the paradox of privilege and toxic productivity in the season of change.

In May, I observed countless scenes of couples swaying handin-hand, flocks of friends skipping (class), parks so full the green grass is swallowed by crowds. At our feet, the first daffodil cracks the concrete like hope finding its way through cynicism. I feel both joy and shame. What a privilege to slow down, to walk aimlessly, to notice the daffodil. What a privilege to be unproductive.

In this Western world of ours that worships self-optimization, slowing down can feel like betrayal. Spring, once a metaphor for rebirth and soft awakenings, has become yet another excuse to re-strategize our calendars. The sun shines, and istead of taking a minute to bask in its presence, we wonder: “Am I doing enough?”. We weaponize warmth into fuel for further hustle – clean harder, work longer, run faster.But Spring’s most radical offering is not more productivity. It’s the permission to pause.

When I brought this up in my circle, two friends of mine produced two opposing perspectives on the matter:

Friend 1: “I feel exhausted. I can’t stop doing things I feel I ought to be doing. It feels like I’m wasting time if I just allow myself to follow my own routine.”

Friend 2: “Just do what you want. What’s the worst that could happen?”

GUEST ARTICLE

Why does it matter? It matters entirely.

Because toxic productivity is a system that feeds on our insecurity and weaponizes time. The privilege of rejecting it (of not needing to “earn” your rest) is not available to everyone. For Spring is not a respite, but a reminder. A contrast between how it should be and how it (actually) is.

Still, the flower grows. And perhaps that is the miracle. Seeing the city burst into life with the vibrant colours of flower petals have always made me emotional. Seeing such delicate flora thrive against the background of the concrete jungle begs for protection and care, but also shows their resilience. Like a celebration, petals thickly cover the ground like frosting on a birthday cake.

They don’t ask for permission to bloom. They don’t feel guilty about doing “nothing” but growing.

What if we, too, gave ourselves that grace?

It’s a hard sell in a culture obsessed with becoming. We chase “Selbstverwirklichung”, or self-actualisation, as if it resides at the peak of a mountain only the busiest can ascend to. But what if metamorphosis is not about climbing, but fortifying? I’m talking about rooting oneself into the very ground we stand on, the dynamic nutrients we’re made of.

What if it’s about softening into the truth that we are always changing, whether or not we try? Toxic productivity tells us we are only worth what we produce. Spring disagrees. To simply notice – the inviting tug of the warm sun – the giggle of a toddler, the bud that wasn't there yesterday – is

its own kind of resistance. In a society that insists on speed, noticing is revolutionary. A flower, after all, doesn't bloom to meet a deadline. It does so when it’s ready.

And there you go. It’s perfect, and it’s dying already. But it doesn't worry about its usefulness. It simply is – fragile, fleeting, honest. So maybe the point of Spring isn’t to emerge with a new plan or a better version of yourself.

Maybe the point is to re-enter life with a little more tenderness. To recognize, that the opportunity to even contemplate one’s purpose in life, to even take that walk with no destination, is a gift. Not everyone gets to metamorphose on their own terms.

This season, I offer no resolution. Just a suggestion: look outside. Let the soft wildness of the world interrupt your task list. Let it remind you that existing, breathing, noticing – these things are enough.

Happy Spring. Might be worth pausing for the next blossom…

My day starts slowly, and then all at once. I brush aside the dream and ready myself for a change of state. We walk over the grey stone sidewalk past the frozen morning dew and standoffish, large geese. I struggle to engage in an early morning chat. Past the school, we round the corner—Duivendrecht greets us with its large white letters framed by a red triangle, a late modernist sign for a sci-filike station appearing to be stuck in the Cold War.

Are we stuck here, too?

The platforms run so long you’d think they stretch to the following station. Or to the rest of Europe. Like its architecture, the station’s geography appears stuck, not in the past but in a swampy field. Tall, full trees enclose the steel-framed concrete and glass structure. Beyond them lie vast green fields, one of which has become colonised by a white-ish concrete slab serving as the foundation for this parking lot or that building project. Of course, the reader should not mind the details, but instead feel the sun’s caress from these mid-July photos.

Text & Images Alex Dieker

The not-oft-trampled rear exit leads us to the village of Duivendrecht, complete with a church and historical map, but nobody appears to be living here. It’s as if the town was constructed after the station, in its name, and very few chose to move in amidst the scramble to transfer from one train to another.

This space is for transport; one must teleport oneself to a remote locale, to this behemoth of a crossroads, to further pass to another Dutch city. I wonder: What is that final destination?

In the pentagonal entrance, we approach the gates to check in. Up the escalator, round the corner. Will it be an oat milk cappuccino or a sprint to the train doors, flashing red like a departing space shuttle? Layers of stairs and escalators, the overlap of foot-bound transit routes. How easy it is to not be seen, to inundate oneself with a podcast or, during the course of this photo shoot, a casual conversation with a friend. Topics of the day: What the heck is this building doing here? Is this the greenest station in Amsterdam? Should we grab a pint?

This is a centre of overlap, of meeting in the middle. Amsterdam sandwiches this small village and its oversized station. One can see the city and, with the turn of a head, the endless fields of ‘rural’ Holland.

It’s winter again. Small, beady-eyed crows watch us as we stand in the cold, between two worlds. In a few stops, we will be in the city centre with the cafés and coffee shops, tourists and rich locals, and buildings built with blood money. The Bijlmer sits only two stops in the other direction and hosts a more widely spread layout, a more diverse population. The station’s design echoes the massive honeycomb high-rises which define the modernist housing project of the city’s Southeast. I call it home, for now. Duivendrecht bridges a geographical and temporal gap. And in what unique fashion! An extravagantly concrete, unabashedly ugly, multi-layered station for a city of cultural tapestries.

This space feels distinctly inhumane, a product of Amsterdam’s unending spatial growth, built to facilitate the movement of thousands of daily commuters. We move from one place to another, a phase of life, the next turn of phrase, a hop, skip, and long leap into the future. As we look back at the station leaving our sight, we remember that nothing is stagnant—everything is changing. Probably for the better.

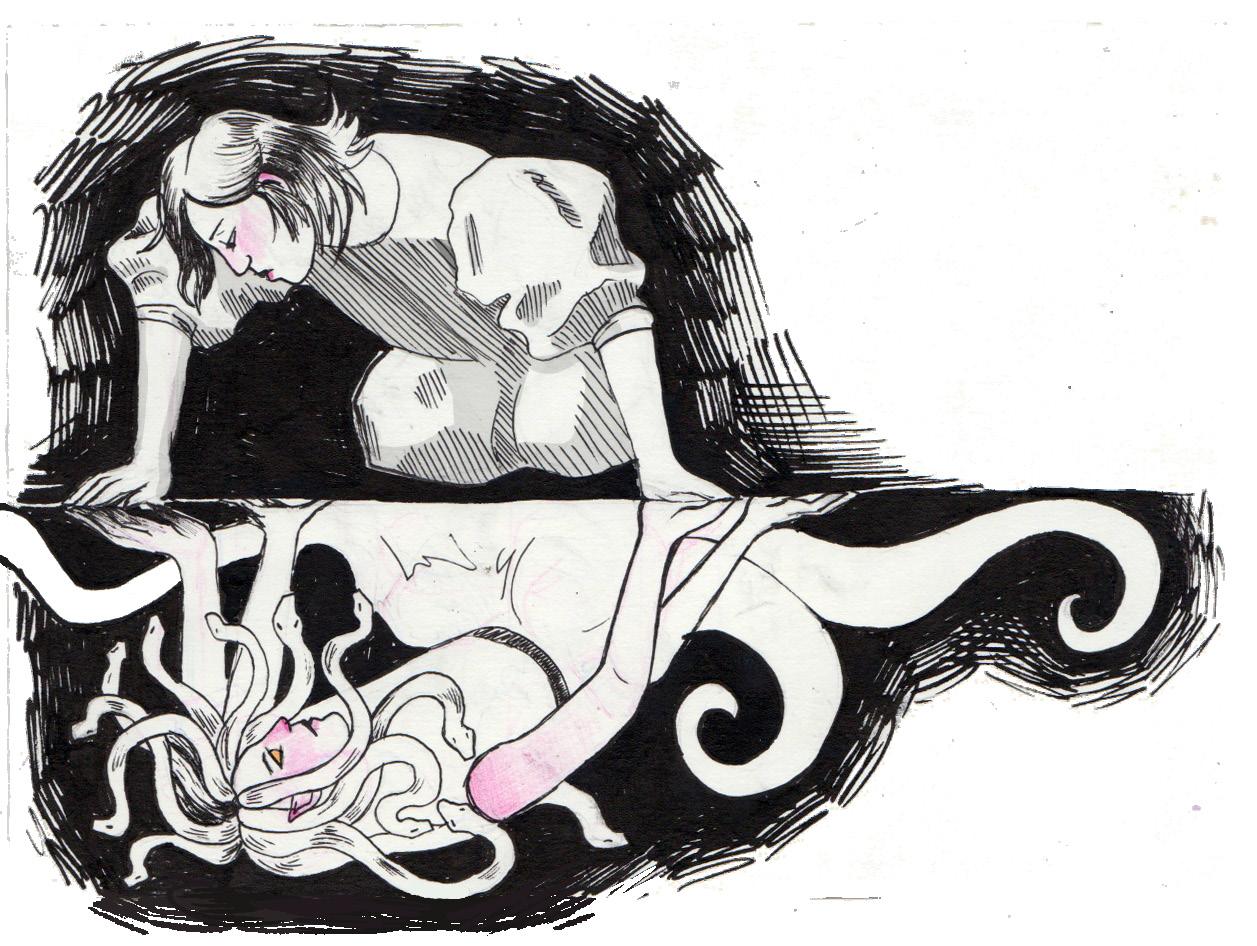

Hermaprodithus and History

Text Morrigan Fogarty Image Alžbeta Szabová

Disclaimer: It would be misleading to call this an interview, it is instead a collection of thoughts and theorizations about monster theory, queer theory, mythology, and how we read the past. I wrote this because I met Brennan, and it was written in conversation with her and her work, and I’m thankful for the time she spent talking monsters with me.

Ayoung boy walks alone in the woods. He comes upon a stream where a nymph watches him from afar, infatuated. She advances, he recoils, repudiates, and retreats from her. She throws herself upon him, and as they thrash in the water she calls to be made one. The monstrous emerges, the body both of man and of woman, and the monster speaks, it asks for a wish to be granted. Curse/bless this pool, make it so that others will be like me.

That is the simplest version of Ovid’s tale of Hermaphroditus. Stripped down to the bone the skeleton has little to say. Dear reader, it is our job to be the flesh.

Brennan Kettelle is a sort of queer necromancer.

In my young academic career I’ve noticed a peculiar phenomenon. While discussing my work with peers and professors, at some point I’ll be told of a scholar who I’ve yet to meet that my interlocutor is thus stunned to learn that I haven’t yet encountered. I don’t take this as a unique experience, but I’m happy to report that I’ve yet to be disappointed whenever I do evidently meet with the aforementioned scholar. Brennan was no exception.

I first came across their work in a lecture they gave on Monster Theory and Lilith, arguing for Lilith as a monstrous figure, (who I will not attempt to categorize or explore in this paper), and the role that Lilith held in sexual magic discourses, specifically as the embodiment of an enticing, evil, chaotic, queer figure created in the cosmological worldview espoused by the misogynist, homophobe, and all around weird guy Samael Aun Weor. I was not particularly struck by Aun Weor but instead in the way that Brennan utilized Monster Theory. Jeffery Jerome Cohen gave us Monster Theory in his work Monster Culture, and it’s beautiful in both its simplicity and its ease of execution. In brief, it posits seven theses that act as a mirror with which we can analyze and understand the cultural significance of a monster. In this case Lilith wasn’t just a queer demon going around and sending the unwise into her arms of sodomy and blasphemy. She was representative of anxieties, boundaries that shouldn’t be crossed, and also of thresholds of becoming. Towards the end of the lecture Brennan teased an idea she’s developing,the idea that we can identify with the Monster, that the monster can be valorized, and this relation can be seen between the Monster, and what we call the Queer.

STAFF ARTICLE

When I went to talk with Brennan, I went in with the express intent to have a free flowing conversation. This article was ultimately going to be about a monstrous queer reading of Hermaphroditus, but not knowing everything about the story or Brennan’s familiarity with the subject I decided to instead focus on Monster Theory and Queer Theory in general. This was the right call, as it allowed a flexible interview lasting about two hours filled with more dialogue than questioning.

After summarizing the story, I asked about the Queer as a Monster, and what kind of cultural associations queerness has had in the past. Brennan told me about pathologization, the idea that the Queer is contagious, for example found in the idea of Lesbian Narcissism, a theory that pathologized and psychologized lesbianism as a mental manifestation of intense dangerous self infatuation. It’s not hard to see how this trend of pathologizing the queer is extended to our times. One only has to briefly look at the news to see right wing fears of children being “groomed” into transition or queerness. This pathologization can easily be connected to monsters - Brennan talked about the history of the vampire being connected to these fears about infection and conversion. The Queer Monster can infect; it is a monster that not only exists at the boundaries but also invites you in to dwell with them.

When I read Hermaphroditus for the first time, I wanted to read it in a certain way. Being a trans historian means I have an urge or desire to look for people like me in the past. When I hear of a figure whose body is male and female, whose body is in some ways like mine, at a threshold of becoming, I want to say that they’re trans. This is of course a survival strategy. Increasing bigotry and transphobia means we are constantly in fear of being erased, of our stories being undone and untold, when I read of Hermaphroditus, of him asking the gods to leave behind a magical pond so that others can be like him I want to join him in those waters. One might think

that being transgender is simple, a want to go from concretely male to female or vice versa, but so often it is about standing at a threshold, at being in between two platonic ideals that nobody actually fulfills and deciding where one wants to define themselves. It’s why Hermaphroditus can feel relatable whereas the story of Tiresias, a blind prophet who was instantly transformed into a woman as punishment, does not. It seems fitting that the example of Lesbian Narcissism, like the story of Hermaphroditus harkens back to mythology, to stories and histories that can be interpreted and reinterpreted. Brennan told me about their work on Renée Vivien who “was proud to be a man hating sapphic poet”, and spent her work digging through historical figures to revitalize and valorize them as queer figures, one of which of course being Lilith. This process of taking the monstrous, of looking at them and identifying with them struck me in its profound implications but also its immediate recognition in my own life. Brennan told me that “if you’re going to become monstrous either way then why not work with that”, and it struck to the core of this process. If we are seen as monsters, if we are seen as things to be afraid of, we have to ask why, and what those fears represent. While monster theory is a great tool for examining this, we are still left alone in our analysis. Instead, Brennan spoke of “comrades beyond the veil”, of history as a site of connection that isn’t concerned with one hundred percent factually accurate questions like “was the Roman leader Elagabalus a trans woman?” but instead of how we can connect with hidden legacies, if we can make history be something for us instead of just describing us. I don’t know who wrote the first version of the Hermaphroditus story or what they intended (one particularly humorous explanation is that the Greeks wanted to prevent some barbarians from drinking from a spring so they made the story as a way to scare them away, telling them they’ll grow breasts if they keep using it), but I know that when I read Ovid’s version and I look briefly beyond the veil of textual authority, I can find myself in its words.

Sleeping Hermaphroditus (1620) Gian Lorenzo Bernini

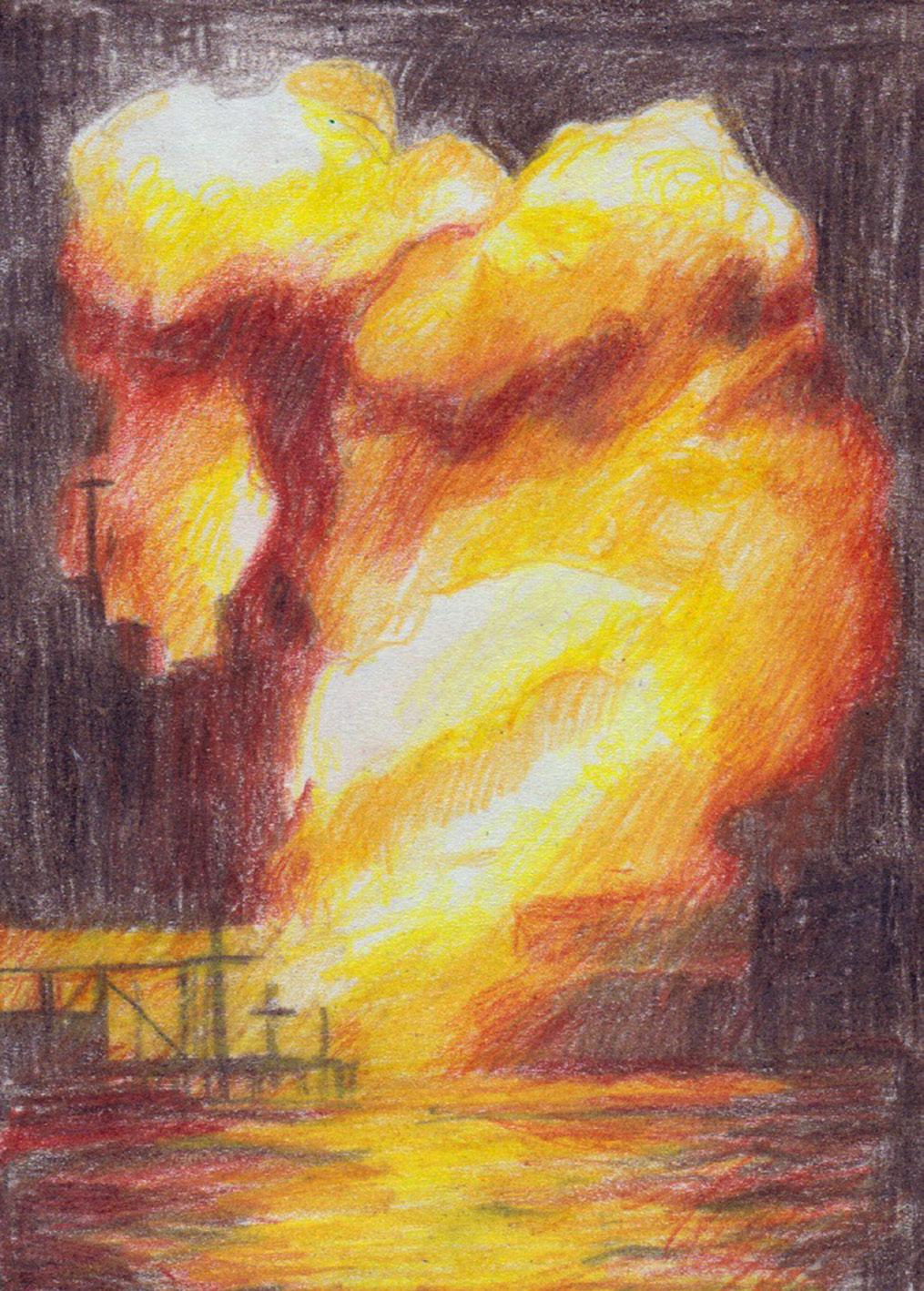

A Military Metamorphosis

A Metamorphosis From Student to Soldier

Text Kristine Lyckander

You were 18 years old when you went to the military selection session. You were skeptical at first. One year in the army to prepare for a potential future war? You surely had other options than that. You enter the doors excited to leave again when you see the first screen. A bunch of teenagers in camouflage military uniforms standing side by side, smiling towards you. You see another screen covered with bold letters stating the military’s core values: Human dignity. Freedom. Democracy.

Perhaps you were too quick to judge? You were also taught to uphold these principles. You enter the interview, confused by your own thoughts. You hear yourself saying “I want to go to university”, and the interviewee responding, “you can study after one year of compulsory military service”. You are assigned to serve one year in the navy, starting after you graduate highschool, at the end of the summer break.

You wake up at 05.30, make your bed without a wrinkle, polish your shoes, fix your hair. You go outside, find a spot in the line-up and look around. You see identical copies of yourself staring straight ahead. No. There is one person who did not shave their beard properly. A commander, only differentiated from the rest by a distinct insigna symbol on his uniform - a thick, red line beneath the “Navy” symbol we all wore, orders you to hold a plank until the person fixes his beard. There. Now he is identical too. Your individualistic values are slowly fading away, replaced with a collectivist mentality. Here you are no individual, no better or worse than the person beside you. A small voice inside your head asks “was collective punishment necessary to achieve obedience?” as the commander stops at your position, stating that your shoelaces are untied. He orders everyone to hold the plank and you fix it in an instant, your terrified heartbeats silencing the small voice in your head. You have no time to consider how a thick, red line sewed on a uniform can assign power to one individual over all the rest. You follow orders.

You have been here for six months now. You have learnt to cope with everyday tasks, and with the punishments given for failing them. You work harder each day to avoid the anxiety you get from failing and from disappointing others. Meanwhile, you have made great friends and you have become stronger than you ever imagined to be. You have free food on your plate everyday. You are more secure in yourself and you have found strength to believe in yourself. Even a military base can become a home.

You have become incredibly precise in shooting practices, finally achieving recognition from the commander who told you to fix your shoelaces on the first day. The compliments make you feel a way you have never felt. You are seen for your strengths by a person whose job it is to punish you for

your weaknesses. You want to chase that feeling and you train harder than you ever have. A small voice in your head says “wasn’t this the guy with a different insigna on his uniform who humiliated you for your untied shoelaces and punished the others for your mistake?” You ignore it. You no longer question his power to correct you. You question how you can metamorphose into his position next. How good must it feel to be the one giving orders instead of the one being ordered?

You finish your one year service, but are offered another year due to your exemplary progress. You have figured it out now. The more loyal you are, the higher you can rise. The higher you can rise, the more power you have. You walk around the new students, freshly born soldiers, and see them looking nervously towards you and the red line assigning superiority placed comfortably on your chest. You smile. Finally, it is your turn to teach them unquestioned discipline and hierarchical respect through collective punishment. The cost is high for human dignity and freedom.

You have spent 8 years in the military. The day you have trained for is finally here. War has come. You stand with your weapon, your closest friend in battle, your tool for survival, whose only purpose is to kill. Suddenly, you see a foreign soldier ahead of you, scoping for a hiding place. You lift your gun, pointed precisely at her heart, ready to fire the shot you have been complimented for time and time again in practice sessions.

But the soldier turns around and sees you. Your limbs become numb. A young soldier, looking no older than 18, stares into your eyes, terrified of what's to follow. In her expression, you see the reflection of your own face when you were 18, insecure and afraid of what you were becoming a part of: a state turning teenagers into weapons to maintain their own wealth and secure position in a society where war has become another way to make money. Where the weapon you hold, which has been made to kill another human like yourself, was created so that someone could profit from selling that weapon. Now you stand here, prepared to kill a young soldier, from a country you have no relationship to, whose individuality is stripped, whose friends, family and identity is invisible to your own eyes. You look down at yourself, your uniform, your insigna, your weapon, and you hear a small voice you haven’t heard in a long time, say “perhaps you are the inhumanity you have been told to save the world from?”

Two shots. You fire two shots in the teenager’s heart, forever silencing the soldier and that small voice in your head. You would rather be tributed as a hero than accept that the life you chose is built on institutional values slowly turning teenagers into loyal, unquestioning soldiers no matter the harm it can cause.

Birthday

Text & Image Elena Candon

When you look at this painting—or rather, a picture print of this painting—what do you see? Do you think of your past birthdays? How do you feel about your birthday?

I’ve always thought a lot about age and who I am or who I should, or maybe could, be on my birthday. More so than any other day that marks the change of time, like New Year's or the last day of school before summer break. I made this painting because I feel there is a sort of peace in getting older. The model in my reference photo was 5 years old, but I didn’t want that to show. I want this painting to be relatable for all ages, because while getting older means change and a loss of time, it is also a way of winning, of gaining. After all, every birthday means another year of experiences, memories, and thoughts that are for you to cherish. In this painting, I tried to emulate this flexibility and duality of change by using wide, undefined and unblended brushstrokes to create a sense of unfinishedness and texture. So to me, birthdays mean a metamorphosis of yourself and yet at the same time staying the same. I would like you to look at this painting and see for yourself that you are exactly the same as always, and always changing.

An Ode to the Friends I've Had Since I Was Thirteen

Text Mia Grassi

Image Carme Ferrando Soriano

We have been friends for almost ten years, and I am very proud of this fact.

I announce it with a smile every time I introduce you to someone new, or when I mention you in conversation; and I’ll admit, it happens often because I just can’t resist not talking about you, about those years we shared daily and about the lives you lead now that we’re farther apart. I can’t help but shout how proud I am of you and how grateful I am to know you and have known you all this time.

We have been friends for almost ten years (8 to be precise - if you care about that sort of thing), since I was thirteen.

Thirteen is a complicated age, or maybe it just feels that way when you’re no more a child than an adult. In those days I was very harsh: blunt and unforgiving, a mixture of insecurity and undeserved self-righteousness. Yet you never resented me for it, at times you were even delighted by it. You met my harshness with patience, my pretentiousness with humor, and my rigidity with warmth. You accepted parts of me I hadn’t yet come to understand or accept in myself. Since then I have softened, you softened me. And while I still have some sharp, unbending edges (I know, I’m working on it), you have taught me not to take myself quite so seriously all the time. To let go, laugh it off, to ease up on the world and myself. I’ve always known that even the teasing comments, disagreements, and rare arguments we’ve had have been laced with as much love as the good times. Our friendship, our conversations, the memories we’ve shared have shaped me into someone more open, more compassionate, more grounded. I don’t know who I’d be if we hadn’t met.

We have been friends for almost ten years, and I have been there for all of your firsts and you mine.

We even had many together. Remember that time we painted matching streaks of blue in our hair so that we’d look cool for

our first concert? Or when I taught you how to smoke with stolen cigarettes in that hazy warm basement that played the loud music? I remember explaining that you kinda have to swallow the smoke. Can you still feel the concealed excitement of when we’d walk into the liquor store that didn’t check IDs, looking to buy bottles of vodka to bring to school trips and birthday parties? Who even drinks vodka anymore? After I had sex for the first time I was in a rush to leave his bed so I could run back and tell you all the ways I felt changed and at the same time not different at all. When I was seventeen I wrote in my diary that I learned how much love could truly hurt because I watched you sob on the bathroom floor after a stupid, inconsiderate boy broke your heart. Now years later, after I have seen you face even bigger losses, I know how naive that sounds: no matter how close we are I can’t know the depths of your sorrows. What I can do is hold your hand as you traverse the abyss. I hope I have done that in all the years we have known each other and I know you’ll do the same when my turn comes.

We have been friends for almost ten years, and I am in awe of the person you are becoming.

I know we don’t talk every day, not even every week, (sometimes not even every month) but it doesn’t faze us because we know that what we have is secure and undeniable. I’ve gotten to a point where I cannot even imagine a life without you. Now that some of us have made it to graduation and most have gotten their driver’s licence, I can start picturing where you’ll move to next, our future careers, a wedding maybe, a baby? Most of all, I like to picture us together as old ladies. I know, I’m going too fast. What I’m trying to say is that I feel honored just to be a witness of the lives you’re building, wherever they might lead you - let alone be a part of them (and I plan to be for a long time). Looking back over these almost ten years that have gone by so fast, I’m amazed by how much we’ve all grown—not just individually, but together. We’ve moulded each other through years of laughter and cries, deep conversations, long distances, and unwavering support. And because of that, I carry with me pieces of each of you in eve-

The Papal Metamorphosis How Religious Authority Adapts to Shape Modern Politics

Text Neve Faulconer

Image Helena Peters

Forty million dollars. That's how much money was wagered online as the world watched 120 cardinals disappear behind the sealed doors of the Sistine Chapel to choose the next Pope. The last papal conclave that elected Pope Francis was in the Spring of 2013, three years before tik tok launched. This go around, for a generation raised on Netflix and TikTok, the papal conclave this past May lasted just two days and coincided with the global techno-cultural trends of our time, where games and world news of magnitude are delivered side by side, simultaneously and in the palms of our hands.

Live tracking the single smoke stack on the Sistine Chapel in person is an ancient ritual, with on screen viewing added since the first televised conclave in 1978. The stakes have always been relatively far-reaching, and the outcome influential to Catholics and non-Catholics alike. However, the context has shifted exponentially. This year because of the dramatic growth of the internet world wide, those stakes are truly global and the audience far exceeds anything prior. According to Stream Charts, the live stream of this year’s announcement had a peak concurrent viewership of 5.87 million people, from over 1,700 live streaming channels. The event generated over 16 million hours of viewing time. This is not the reach of the news about the Pope over the days, weeks and months, this is essentially the size of the crowd outside the Vatican in real-time.

While papal transitions have captivated people since the time of St. Peter, the most recent fever perhaps originated in Hollywood. The film Conclave introduced millions to the secretive world of papal elections, giving fictional life and light, drama and intrigue to otherwise completely obscured religious rituals. Then reality caught up with fiction: Pope Francis

was hospitalized, died, and suddenly people who had never cared about Vatican affairs found themselves glued to Vatican live streams, betting on cardinal favorites, and debating the future of the Catholic Church with the same intensity usually reserved for presidential elections, speculating the plot as if it was just another season finale of Game of Thrones.

For someone like me—nonreligious, twenty-something, more familiar with political scandals than papal encyclicals—this was unfamiliar ground. The Vatican has long been entangled in global politics and controversy, but I’d never paid it serious attention. Yet I found myself captivated—not just by the pageantry, but by a nagging question: Why did any of this matter beyond the walls of the Vatican?

The answer, it turns out, is more enthralling than the conclave itself.

When Pope Leo XIV emerged as the new leader of the Catholic Church on May 8th, 2025, he wasn't just assuming spiritual authority over 18% of the world's population. He was stepping into one of the most influential political roles on the planet—a position that operates at the intersection of diplomacy, moral authority, and soft power, in ways that would make most world leaders envious. The same technology that has exposed tens of millions more people to the conclave event, has exponentially increased the significance of the Pope’s role across the globe. This is in fact very new in scale.

The Vatican's diplomatic reach is already staggering. With formal relations with 183 countries—more than any nation on earth—the Holy See operates the world's most extensive diplomatic network. The Pope holds permanent observer status at the United Nations, receives invitations to international conferences as a matter of course, and maintains open chan-

nels to virtually every world leader. This isn't just ceremonial access; it's real political influence wielded by someone who never stood for public office or election. “Observing” even just 20 years ago, wasn’t anything like “observing” today, thanks to live streams, social media and the spread of the internet image, information, video sharing and hand-held super-computing. The internet reached a few hundred million people as recently as the 1990’s. Now it reaches 5.5 billion people. In our supposedly secular age, where the separation of church and state is perhaps assumed to be a popularly held principle and a growing trend, in exchange for democratization, how did a religious leader become one of the most powerful political players in the world today?

The papal metamorphosis isn't just about the transition from Francis to Leo XIV—it's about understanding how an ancient institution continues to shape modern politics, and why that should matter to all of us, believers and skeptics alike, beyond the characters and after the smoke has drifted away.

The Paradox of Unelected Authority

Here's what makes the papacy so fascinating— and troubling: in theory, the Pope represents the Catholic Church as an institution and its constituents, which derives its political authority from Jesus Christ, according to Catholic belief, who established the church and conferred authority upon the apostles and their successors, the bishops. However, in practice, in an era where we claim to champion democratic legitimacy and aim to question every form of unelected power, we've somehow carved out an exception for one man who answers to no constituency, faces no elections, and operates with virtually no oversight. Yet world leaders line up to meet with him, nations compete for his attention, and his statements can shift global conversations overnight. What makes this power so unique is its moral scale. While politicians navigate partisan divides and national interests, the pope operates from a position of perceived moral authority that transcends political borders and affiliations. His religiosity doesn't limit his influence—it expands it, placing him somehow "above" the usual constraints that bind other leaders. When the pope speaks, even secular leaders listen, because he carries the weight of what believers (and Catholic voters) see as divine mandate and what non-believers often respect as moral clarity or wisdom. While it can contribute to humanitarian efforts and peace efforts, a more complete understanding of this power must clearly include, it can just as easily repress, disregard and cause pain and death in other ways.

This isn't theoretical power—it's been repeatedly demonstrated, for better and for worse, throughout modern history. Pope John Paul II is frequently credited with helping to inspire resistance movements across Eastern Europe during the Cold War. But his legacy also reflects the dangers of papal influence: under his leadership, the Church entrenched hardline stances on reproductive rights, sexuality, and gender—positions that continue to shape policy in countries like Poland, where Catholic doctrine has helped justify some of the most restrictive abortion laws in Europe. Alongside Cardinal Ratzinger, John Paul II reoriented the Church toward a deeply conservative vision with global consequences.

More recently, Pope Francis positioned himself as a key intermediary in the attempted restoration of US-Cuba diplomatic relations—a moment hailed as historic at the time, though much of the progress was later reversed. Still, the Vatican’s involvement signaled its ongoing ambition to serve as a moral broker in geopolitical affairs. Whether enabling conservative backlash or facilitating momentary breakthroughs, the papacy’s interventions continue to shape the world in ways that few unelected figures ever do.

Popes consistently position themselves at the center of international conflicts, offering to host peace talks and providing moral commentary that shapes global opinion. During the Iraq War, Pope John Paul II was one of the most vocal international opponents, lending religious weight to anti-war sentiment. Today, Pope Leo XIV has already offered the Vatican as a neutral venue for Ukraine-Russia peace negotiations and issued calls for a ceasefire in Gaza. While these gestures have yet to yield concrete results, they reflect the Vatican’s continued effort to present itself as a moral actor in global affairs. This performance of neutrality and moral clarity—regardless of outcome—reveals something crucial: the papal office has evolved into a form of global moral arbitration that operates parallel to—and sometimes more effectively than—traditional diplomatic channels.

Perhaps most significantly, the Pope's positions can vary if not differ from the prevailing majority view of the Catholic institutions globally, and often serve as a barometer for attempting to shift global ideological currents. Pope Francis exemplified this perfectly, bringing progressive stances on climate change, economic inequality, and migration that both reflected and amplified a global progressive moment. His relatively tolerant positions on LGBTQ+ issues opened conversations within conservative communities that would have been impossible coming from political leaders. It was not shared by all in his faith by any means, but his ability to push that boundary is singular, compared to any other political figure.

But this same moral authority can be wielded to reinforce traditional religious doctrines that many societies are trying to move beyond—limiting women's reproductive rights, opposing gender equality, restricting LGBTQ+ rights. When a conservative pope speaks against progressive social changes, he doesn't just influence Catholics; he provides moral justification for political movements that seek to roll back these advances globally.

The Leo XIV Shift: A New Global Moment?

The selection of Pope Leo XIV signals a potential recalibration of this influence. As the first American pope, his election was no accident—the Vatican chooses its leaders extremely strategically, responding to global political currents while attempting to shape them. Leo XIV's more centrist positions and his early emphasis on "traditional family values" suggest a deliberate move away from Francis's progressive momentum. This shift matters beyond Catholic doctrine. If papal politics serve as a global ideological barometer, Leo XIV's more conservative approach may reflect—and reinforce—a broader

retreat from progressive politics worldwide. But his American identity adds another layer of complexity. Far from aligning neatly with U.S. soft power, Leo’s election may be a strategic response to it: a way to neutralize the rise of far-right American Catholic factions like Opus Dei, which were some of Pope Francis’s fiercest opponents. In that sense, his Americanness might be less about projecting U.S. influence abroad and more about containing its internal extremism within the Church.

The metamorphosis from Francis to Leo XIV isn't just a change in church leadership—it's a recalibration of one of the world's most influential sources of moral and political authority.

The Democratic Paradox We Ignore

This brings us to an uncomfortable question that most of us would prefer not to ask: In our supposedly secular democracies, should so many accept—or even celebrate—the political influence of an unelected religious leader?

Is not separation of church and state widely considered a cornerstone of modern, democratic governance? Nations where religious authority shapes political decisions, are often labeled backwards or undemocratic. Yet is there a massive exception for the Vatican, treating papal political intervention as not only acceptable but often admirable?

The recent papal transition has led many people my age especially, to confront this contradiction for the first time. Suddenly, the stakes became clear: the ideology of the person chosen to lead the Catholic Church would have real consequences for global politics. People who had never paid attention to Vatican affairs found themselves caring deeply about whether the next pope would be progressive or conservative, because they finally understood that it would affect them— believers and non-believers alike.

Time for a Secular Reckoning

The scale of influence and power, inherent to the papal metamorphosis from Francis to Leo XIV, is unique to our times and should serve as a wake-up call to the new generations and old alike, to fully examine, or re-examine, just how secular our supposedly secular democracies really are. The first step is awareness—recognizing that religious authority continues to shape global politics in profound ways, often operating in a blindspot of public consciousness and the scale of influence grows annually, exponentially. This influence operates largely without obligation to public scrutiny or democratic oversight. Can an organization that invests and profits, shapes borders and brokers agreements be considered independent from the obligations and burdens, sacrifices and accountability that comes with sovereignty?

As global politics become increasingly polarized, the pope's ability to influence both progressive and conservative movements makes him one of the world's most consequential political actors. Yet unlike democratically elected leaders, he faces no voters, no term limits, no institutional checks on his power.

Critical awareness must precede critical evaluation. Once we acknowledge the extent of papal political influence, the real questions emerge: Why have we continued to tolerate unelected religious authority shaping global politics? What would it look like to seriously challenge that influence—through diplomatic scrutiny, media accountability, or international pressure? And how do we reconcile the principle of religious freedom with the reality of religious soft power operating across borders, often against democratic values?

The papal metamorphosis reveals something fundamental about our political moment: Religious authority has simply adapted; not disappeared. Actions of the Catholic Church have always been motivated by more than religion—a struggle of power and politics. Pretending otherwise is naive and dangerous.

As Pope Leo XIV begins to shape global conversations in ways that may last decades, new generations cannot afford to treat papal politics as entertainment, games, or a curiosity confined to the religious sphere. Our technologies measure their success in time, “eyeballs” and revenue extracted, not in moral outcomes or societal benefits or peace. The message behind Sinead O’Conner’s historic act of protest in 1992 on Saturday Night Live, calling out systemic abuses by the church, was three decades ahead of recent revelations and the first public accountability for the church on those issues. A similarly influential artist today, sadly, would likely face the same devastating dismissal and punitive repercussions. Just because many people are witnessing, does not automatically translate to democratic action or concensus. The church's influence remains strong and present, operating at the highest levels of international relations and shaping policies that affect billions of lives.

Hillbilly - The True American

Text & Image Helena Peters

My friends and I started discussing the word hillbilly, as one does at a bar. I became increasingly worried discussing this word, as I associate something negative with the word hillbilly and wasn’t sure if it was insensitive and ignorant to use. But my friend said she disagreed as the word for her was just an objective description; this is how we started off our discussion.

To understand the word better and to see where we stand regarding its usage, I wanted to look into the history of hillbillies and ask my American family for the personal association they have to it to get a bigger picture of it.

A hillbilly, according to the Oxford dictionary is: “a person from a mountainous area of the US who has a simple way of life and is considered to be slightly stupid by people living in towns and cities”. This aligned with my understanding of the word, and I read the definition out loud to prove my point that night. My confidence in stating this definition really showcased my personal prejudices and the false ideas I had developed. Saying that I agree with this definition sets a border between me and “them” (the hillbillies as a group). Are Hillbillies actually so real that I'm able to call them a group, or is it only something imagend? Now, writing this after speaking with my American relatives and researching online for answers, I present you my journey, which is up for further exploration.

Through some further reading the word became an entity of description through the Scottish settlers in the united states of america. These were the first to be called hillbillies, due to the common name William and their living situations in the hills in Scotland and Appalachia. But this still didn't explain how the word developed into an overgeneralization within American ideals.

To cut into the root of the word, I thought talking to the older American generation would be helpful. I asked my grandfather and grandmother who live in Boston, and my grandmother who lives in California, and both came up with a description of hillbillies that points to an idea of a less developed human. “They need less to make them happy it seems” and “we judge them to be more undereducated and underemployed but they work much harder at more physical jobs.” I believe this last sentence from my grandfather explains my point yet again. The perspective on hillbillies usually relates to something negative and lesser. Yet the understanding of their culture and their being is not perceived or explored enough from their perspective.

My grandparents also added that their perspective was also built upon television shows. My grandmother even explained how she, as an elementary school teacher, had a difficult time teaching kids in southern Ohio, a suburb of Cincinnati as many parents of these kids lived “the hillbilly lifestyle” and did not have aspirations for kids to leave their town or enter the “educated” workforce.

In its socially created definition, hillbillies are on the lower end of the scale of a gradual evolutionary line of the American dream: at the beginning. The starting point: uneducated, poor and living far out in the country. The question still stands what hillbillies actually are, or if they even exist as they are painted out to be. Ideas about hillbillies come from culturally reinforced narratives, like in television as my grandmother put it: “To be honest, I think of Hillbillies as they were portrayed in this sitcom I grew up with in the 1960s: “The Beverly Hillbillies”.

Yet, an actual perspective from a hillbilly, as they are defined, ceased to exist fully. Why is this the case? Are they only an imagined community, created in American society? Or are there concrete groups we can call hillbillies?

When I spoke to my American grandparents I got a well deserved first answer to my question of what impressions they had of the characteristics of hillbillies. My grandfather said that “characterizing a group always comes with the risk of generalization and stereotyping”

Thus I keep thinking the question of what American culture entails. The thought of cowboys and country music comes to mind. American society, the American identity, it’s an interesting one to look at and analyze. American society is built on lies and terror. Even the idea of cowboys has its white supremist roots. Most cowboys were not even white and the idea just like the hillbilly developed over time into something so different and fictional. The idea of the cowboy as a white settler came at the same time as the idea of a hillbilly. The history of the states has successfully created a false whiter past with these ideas. It allows white Americans to connect to their supposed history and feel proud to be american.

As time goes by, American culture loses its credentials, more and more discrimination gets uncovered and defeated. What are Americans without white power? The white-claim and commodification of cowboy/hillbilly culture shows how white Americans desperately need something to define themselves and their culture. One could argue that the idea of a hillbilly is all that is left in being a true white American.

"Characterizing a group always comes with the risk of generalization and stereotyping”

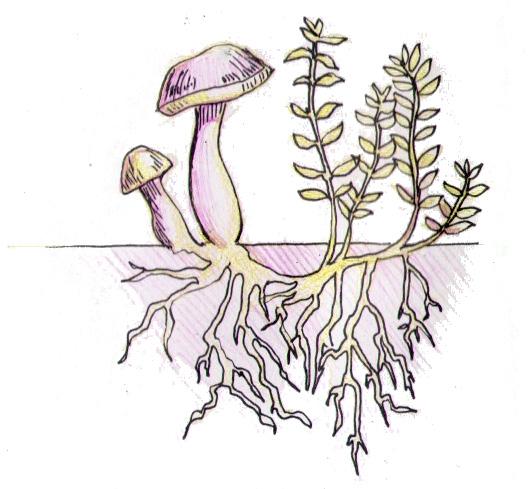

Patchy Ecologies and Policy Futures

Food Forestry in the Dutch Agricultural Debate

Text Amanda Rendtorff Jein

Image Alžbeta Szabová

This is an edited version of an essay that was submitted in May 2025 for the course “Food Forestry: Experiencing the Future of Nature and Agriculture”, in response to the question “What should be the future role of food forestry in the Dutch food system?”

The Netherlands is a land of meticulous order –rectilinear ditches, flat fields, and polders precisely zoned by bureaucratic design. Even nature here often feels regulated, confined to reserves with strict boundaries. Into this landscape creeps a different kind of order: a food forest, lush with intermingled species, blurring the line between farm and wild. This sensory tangle of fruit trees, shrubs, and fungi offers a whisper of change amid the neat rows of monoculture. It invites us to smell humus and blossom where once only crop and chemical prevailed. Food forestry in the Netherlands should be embraced not merely as a novel agricultural technique, but as a catalyst to reframe what is viable, governable, and valuable in land use. Food forestry is a model of deep ecological and social entanglement – a living critique of the dominant industrial logic that demands simplification and control. Where industrial farming has been praised for high outputs at the cost of soil and biodiversity, food forests demonstrate that agriculture need not exist at the expense of nature, dissolving the enduring “dualism” between nature and agriculture . Rather than forcing this unruly abundance into existing bureaucratic boxes, governance itself must evolve. In practical terms, this means reimagining subsidies, zoning, and land valuation to favor regenerative, long-term landscape stewardship over short-term yield metrics. It means listening to the rustle of leaves and the buzz of pollinators as much as to market prices. Food forestry, in short, should act as a catalyst for remaking Dutch policy frameworks to honor complexity, resilience, and the multispecies communities that make our food possible. It is a call to move from the tidy spreadsheet of the present system, where the value of a land is measured not only in euros or tons, but in the continuity of life it nurtures.

In the flat, ordered landscapes of the Netherlands, control is a kind of aesthetic. The fields are neat and the ditches run straight. Industrial agriculture functions like “a machine for converting fossil energy into calories” , a logic dependent on monoculture, external inputs, and the erasure of ecological complexity. This is not only an ecological crisis but also a political one: the state’s commitment to agro-industrial intensification sustains a governance model that simplifies life into units of yield and land into zones of use . Agroecology, on the other hand, thrives on functional biodiversity and place-specific knowledge, like Brazilian cases of perennial, multi-layered designs reversing soil exhaustion while feeding communities . Food forests, Ketelbroek among them, translate that logic northward. During an excursion to Ketelbroek, the

oldest food forest in the Netherlands, this distinction came alive. I walked along hedges deliberately planted not for yield, but for wind resistance. I was told that elder and black alder “prepare” the soil – pioneers that do not feed us directly, but make life possible for others. Wouter van Eck, the founder of Ketelbroek, highlighted this system’s foundations: polyculture, perenniality, and ecological mimicry. Unlike industrial farms, food forests evolve in layers – root, shrub, canopy, vine –each layer playing a role in nutrient cycling, microclimate regulation, and biodiversity generation. The difference is not just ecological but temporal. Industrial farms operate on seasons and subsidies; food forests ask for decades. As Wouter noted, “the forest starts slow... and then lives strong forever”. If industrial agriculture embodies the logic of acceleration, food forestry insists on patience.

In The Mushroom at the End of the World, Anna Tsing writes that we must learn to notice the “assemblages” of life that form without centralized control . This way of seeing unravels the anthropocentric fantasy at the core of modern agriculture: that humans act, and nature responds. Food forestry does not see humans as engineers of ecosystems but as participants in multispecies collaborations – what Tsing calls patchy entanglements, where growth, decay, and reproduction unfold unpredictably. The contrast could not be clearer. Industrial agriculture treats soil as a dead medium for chemical and genetic inputs. Farmers are managers. Crops are products. Trees are removed if they shade the yield. Agricultural techniques are never just about efficiency – they express deeper cosmologies about who belongs on land, and how land should be made to behave . The dominance of monoculture reveals a belief in order, hierarchy, and control: land is something to be owned, and made legible to human goals. Those who do not conform, whether weeds or animals, are often erased. Food forestry, by contrast, takes the side of the forest – not in a romantic way, but in a relational one. To plant a food forest is to submit to processes you will not control: fungi that negotiate with roots, insects that pollinate without asking permission, and birds that will take their share before you take yours. This is not just a method, but a worldview. A recognition that land is not a blank canvas for human use, but a shared space of entangled lives. This reframing of agency, away from human mastery toward multispecies negotiation, also reframes governance. If nonhumans are participants, then policies must do more than regulate, they must listen. Multispecies justice requires imagining ourselves as already entangled, already responsible.

This entanglement is not metaphorical. It lives in the soil, where relationships among fungi, roots, and microbes form the basis of life itself. Soil in a food forest is not passive. It breathes. It stores memory. Healthy soils depend on diverse

GUEST ARTICLE

communities of nematodes, bacteria, and fungi . Mycorrhizal networks facilitate communication between trees, share nutrients, and shape the microbiome of an entire ecosystem . These are not optional extras. They are the foundation upon which food forestry builds its abundance. In the Ketelbroek forest, this was not metaphor: leaves fell and stayed where they landed, feeding the fungal threads below. The soil was damp, soft, alive. This underground life is mirrored above. Food forestry embeds itself into the local microclimate, planting windbreaks, preserving moisture, welcoming pollinators. The forest becomes not a design imposed on land, but an emergent form grown with it. These ecological relations resist standard agricultural models. There is no single “crop”, no linear planting calendar, no standardization. Labor too is reframed. Food forestry, as seen in the Ketelbroek model, is not laborintensive in the conventional sense. After its establishment, the system becomes semi-autonomous. But its social logic is cooperative rather than commodified. It grows networks of people as much as plants. The food foresters told us this directly: “We’re not trying to own more land, we’re trying to connect”. In this sense, food forests are not just embedded in ecological surroundings, they are emergent from them. They grow from soil, sun, and sharing alike.

What might policy look like if it were shaped by food forestry, rather than the other way around? Some suggest the idea of performative politics, governance that does not assume fixed categories, but instead acts experimentally making space for “other worlds” to emerge through practice . A food forest is precisely such a world: it performs an economy of care, an ecology of patience, and a politics of coexistence. This means treating governance as a living system; dynamic, adaptive, and relational. Legal forms do not only constrain, but also express values . What values, then, are expressed when we require a food forest to conform to outdated definitions of land use? What alternatives could we imagine if we allowed ecological systems to teach us how to govern? Inspired by fungal networks and pollination pathways, we might imagine a regulatory system that operates less like a pipeline and more like a mycorrhizal web; decentralized, symbiotic, and sensitive to local conditions. Instead of asking “is this allowed here?”, it might ask, “what relationships are possible here?”. This shift would not only benefit food forestry, but offer a broader model for land governance in the Anthropocene: one that sees humans as partners in a larger choreography of life. Such a vision is not naïve. It is pragmatic in the deepest sense. It begins not with abstraction, but with attention. Attention to the needs of fungi, the timing of trees, the rhythms of community engagement. Attention, too, to the ways that laws, budgets, and institutional cultures can support or suffocate emergent life. In this view, policy becomes more than a set of rules. It becomes a practice of cohabitation.

In the end, food forestry’s greatest promise for the Dutch food system is not just the fruits or nuts it produces – food forestry invites policymakers to see agriculture as part of a multispecies entanglement rather than a factory line. It demonstrates that our food system can be managed not by dominating nature, but by cooperating with it. In fresh language: food forestry should take root as a keystone of Dutch food policy and planning, sparking an evolution toward governance that

A young food forest patch (left) stands in stark contrast to the plowed geometry of a conventional field (right) in the ordered Dutch polder landscape.

learns from ecosystems. This means embedding long-term ecological thinking into policy – treating soil, water, forests, and communities as stakeholders – and opening up decisionmaking to those on the ground who tend these living landscapes. Just as a forest garden balances the needs of apples, mushrooms, and bees, so too can Dutch food governance balance the needs of farmers, citizens, and more-than-human life. Such an integration signals a shift from business-as-usual to a more inclusive paradigm. There are, of course, formidable challenges ahead: entrenched regulations, market pressures, and institutional inertia will not disappear overnight. Yet, the very existence of thriving Dutch food forests and the urgency of climate and biodiversity crises make change both necessary and possible. In a hopeful twist, the edges of the Dutch food system are already sprouting with innovation, much as green shoots emerge through fallen leaves. Ultimately, food forestry should be the catalyst for a governance metamorphosis – one that honors entangled ecologies and fosters a participatory, resilient food future. As we step back from the forest, we carry its lesson that policy, like a mycorrhizal network, can adapt to nurture each unique community and ecosystem it touches. In that enduring lesson lies a seed of hope: a future Dutch food system rooted in collaboration between people and the land.

Reading Recommendations:

“Dualism.”

Rosine Keltz (2023)

Mark D. Hathaway (2016)

“Agroecology and Permaculture: Addressing Key Ecological Problems by Combining Traditional Knowledge and Modern Science.”

John Grin (2025)

“Governance and Politics in the Anthropocene.”

Altieri, Miguel A., and Victor Manuel Toledo (2011)

“The Agroecological Revolution in Latin America: Rescuing Nature, Ensuring Food Sovereignty and Empowering Peasants.”

A.L. Tsing (2015)

The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the possibility of life in capitalist ruins

Michael R. Dove (2021)

“Culture, Agriculture, and the Politics of Rice in Java.”

Kyle Powys Whyte (2018)

“Indigenous Science (Fiction) for the Anthropocene: Ancestral Dystopias and Fantasies of Climate Change Crises.”

Du Preez, Christel C., John W. Doran, and Francois J. Calitzn (2022)

“Nematode-Based Indices in Soil Ecology: A Global Synthesis.”

Suzanne W. Simard (2018)

“Mycorrhizal Networks Facilitate Tree Communication, Learning, and Memory.”

Gibson-Graham, J. K. (2008)“Diverse Economies: Performative Practices for Other Worlds.”

A Search for the Becom(mon)ing of a ‘We’ in Academia

Text Juliana Könning Image Alžbeta Szabová

The first week of April, I got a happy message.

Previously, on a sunny afternoon, we had enjoyed a conversation at the Kattenburgerplein. She had a tattoo on her arm of a mushroom and a plant and their shared underground network. The conversation landed on the botanical term rhizome, the network of interconnected roots that spread out under the ground. The rhizome has the amazing ability to inspire a nonlinear and decentred way of thinking about connectivity.

We, both academics, talked about the desire to do research in a more fluid way, fantasized about what fluidity in research could look like, and wondered to what extent we could maintain fluidity within an academic setting.

We talked about assemblage thinking and how the rhizome offers support, as a tangible ally for such thinking processes.

In the text message, she asked if I could share some more about assemblages, the rhizome and rhizomatic thinking. I wrote to her:

I have never been completely comfortable with using the word ‘assemblage’, let alone to actually apply this frame in its majestic entirety. One of the discomforts arises when I try to write from this perspective, as I believe the process already contains a paradox. Assemblages are “never fixed in time and space”, and in assemblage theory “all materials are viewed as vibrant and in flux” . Writing solidifies impressions of assemblages and in the process, some of the fluidity of assemblages in observation escapes the medium of writing. Also, using ‘I’ in the writing becomes a very selfconscious activity. It undermines the dispersed agencies that have collecti vely informed the understandings that are communicated. Still, discomfort opens up a space for transformative ruptures and can be extremely illuminating, so I (selfconsciously) guess that a theory that causes discomfort is one that deserves our attention.

Transforming the academic ‘I’

Despite my consideration of the act of writing as solidifying fluid matters, I wondered: can we explore more experimen tal expressions in writing collectively? Can we transform the academic ‘I’?

She responded that she recently had the same thought: that writing solidifies fluidities. I experienced the familiar jolt of joy that comes from commonality, when I read her message. She told me she wanted to delve into the ‘I’ in writing, and its

problems. Disliking the ‘I’, she found herself using ‘one’ a lot, but that did not sit completely right with her either. Using ‘one’, she said, could leave the impression of speaking about universal truths. So… where do we (she and I, and …?) go from here?

A problematic ‘we’

For a long time, I have had a desire to write from a we-perspective. However, in academic work I am wary of this style. Who are the ‘we’ in this case? Who are not part of the ‘we’?

If the described ‘we’-experience is culturally definite without being defined, ‘we’-ing can quickly become an exclusionary practice. The ‘we’ often refers to western academics: how ‘we’ make sense of something, with the ‘we’ being (often without my realising it) me and some unidentified western others. An unidentified ‘we’ can be eurocentric, or centred around scientific thinking. ‘We’, then, have to be suspicious of the ‘we’ we refer to when using ‘we’.

A ‘we’ in solidarity

The question of ‘we’ also came up during a seminar for the course Field Theory, when thinking about ‘how can we define the archive’. Someone asked “Who is we?”. Our guest speaker, Rahael Mathews, had the compelling hunch that ‘we’ has to do with solidarity. She gave us a glimpse: “‘We’ is a way of thinking with others (human and nonhuman), we can be anyone, but it is a way of thinking that is more collective” . The becoming of a we felt almost within reach. A search of this collective thinking about we, brought me to an art collective explaining their ‘we’.

And a ‘we’ as being-in-common

GUEST ARTICLE

The temporary art collective ‘We don’t want to be stars (but parts of constellations)’ (2023-2026) uses the terms ‘beingin-common’ and ‘being plural’ . They start from the idea of ‘being-in-common’. ‘We don't want to be stars’ explicates how the common “is not defined in terms of identity, instead it describes the work of connection, of collectivity and alliance, between (local) communities, human and nonhuman, that act, build, and create in common”. In their understanding, ‘in-common’ does not refer to a state, but a process of ‘becoming-in-common’. The common is not a resource, but an activity (‘commoning’), that is prerequisite to include both societal and natural relationality. The ‘more than human’ potentiality of this way of thinking about ‘we’ is elucidated on the collective’s website by García-López, Lang, and Singh: