. Jennifer Diaz, Ph.D., LPC

. Jennifer Diaz, Ph.D., LPC

You’ll never be able to make a difference.” She looked at him thoughtfully, smiled, and then picked up another starfish. As she tossed it into the water she said, “I made a difference to that one.”

Each year, the GSCA President chooses a theme for their presidential year and conference. My theme this year is “School Counselors: Making a Difference in the Lives of Students”, based on the starfish story by Loren Eiseley. There are a few versions of the story now and if you’ve already heard me talk about this, forgive me. However, please also indulge me for a few moments as I share the story as I like to tell it.

There was once an old man walking along the shoreline. As he was walking, he saw what looked like a young girl dancing on the beach. However, as he got closer, he noticed that she was picking something up and throwing it into the water. As he approached her, he saw she was standing among hundreds of starfish that had washed up onto the shore.

“Pardon me, but do you mind if I ask what you are doing,” he asked. She plainly explained, ‘Don’t you see, all of these starfish have washed up on the shore and the tide is going out. If we don’t throw them back in the water, they will all die.”

“Well, I don’t mean to be rude,” he responded, “but there are hundreds.

This story encapsulates a lot of what we do in the field of school counseling. Many people don’t understand what we do in our roles as school counselors. Some question why we do what we do and some seem to have little appreciation for what we do. Regardless, we keep working to make a difference in children’s and families’ lives doing what we know is right. Despite any possible lack of support and/or recognition, we keep doing the work of school counseling because we love children and we want to make a positive difference in their lives. Throughout this year as President of GSCA, I’ve been able to talk to school counselors from every region in the state and hear about their challenges and moments of pride in their work. Unfortunately, we all still have to advocate every day for what we do as school counselors. Whether that is within our own schools for our students or our roles, with local school boards, and even with state and national legislators.

This most recent legislative session, we had to fight the proposed ‘School Chaplains’ Act’ in the Georgia Senate. Some legislators thought it would be a good idea to hire chaplains in the place of school counselors. These chaplains would not have been required to have any mental health training, licensure or certification, and would not have been held accountable by the Professional Standards Commission.

With a lot of work by our Advocacy team and members responding to ‘Calls to Action’, we were able to prevent the School Chaplain’s Act from getting a vote on the Senate floor. However, on Sine Die which is the last day of the legislative session, it came back up in a last-ditch effort from some legislators to get a modified version passed through. Again, the advocacy work of school counselors reaching out to their elected officials had built a strong foundation of legislators that were not open to the idea. However, we cannot rest. This legislation was proposed in at least 13 states this year and is continuing to receive support. Next year GSCA will be prepared to advocate about our profession and educate stakeholders about the work we do making a difference in students’ lives.

This may mean arguing against school chaplains being hired in our place or some other nonsensical legislation that we haven’t even heard of yet. The last few years truly have been a roller coaster ride with legislative issues that can possibly negatively impact our students.

What I know is that if we continue doing our jobs as school counselors and advocating for school counseling programs for all students, we will always be making a positive difference. As my presidential year is coming to a close, I am so very grateful for the opportunity I have had to lead and learn from difference makers who care as deeply about children as I do. Just like the starfish the little girl was trying to save, every single child deserves a school counselor who is willing to do whatever it takes so that they can succeed.

Please read and absorb as much information in this Beacon as you can. One of the best things we do for each other is sharing our knowledge and best practices with what works in our schools. The Beacon is written by school counselors, for school counselors. Though I’m a little biased, it’s also written by the BEST group of school counselors and that is GEORGIA school counselors. I hope that your school year ends smoothly and that you are able to truly appreciate the value of the role that you have in students’ lives, as a difference maker.

As members of GSCA, we believe:

• all students, grades K – 12, deserve access to school counseling services

• the nature and substance of school counseling programs should be , developmental, and continuous

• on-going enhancement of school counseling skills and knowledge to benefit children is essential.

• all people have value and deserve respect and dignity

• counseling services provided to students and schools should be with appropriate accountability components.

• all students should be taught skills that lead to developing competencies in the three areas of academic, career, and social.

Naomi Howard, Ed.D., howardn@clarke.k12.ga.us

According to Parent Square (2023) some of the most effective ways to improve family engagement are providing resources and building partnerships with the community. I currently work at an elementary school, but have previous experience at the middle school and high school levels as well. Our family engagement specialist and I recently worked together to plan a parent night to incorporate meeting present and future needs of our students. The parent night included guest speakers (registered nurses) from a local health center and our regional representative from GA Futures. The topics were car and bicycle safety, healthy eating habits and college readiness awareness of the Path2College 529 Plan. The community resources given and new knowledge gained were astronomical. For instance, the nurse who spoke on car safety surprised us by offering opportunities for free car seats to those in need; and the GA Futures representative gave a plethora of informational resources and swag. We also went out of our way to give words of inspiration and affirmation, as oftentimes parenting is a thank-less occupation. Saying ‘thank-you’ to a parent adds meaningful encouragement (Aguilar, 2011). The parents who attended were so appreciative of the community connections and materials.

Speaking of parents, something my father always says is “Education is never wasted.” So, whether we are being educated from the positive conversation with a parent or hosting an event to share resources with parents it is a two-way street to building the partnership.

Aguilar, E. (2011). 20 Tips for Developing Positive Relationships with Parents. Retrieved from https://www.edutopia.org/blog/20-tips-developing-positive-relationshipsparents-elena-aguilar

Garbacz, A., Godfrey, E., Rowe, D. A., & Kittelman, A. (2022). Increasing Parent Collaboration in the Implementation of Effective Practices. Teaching Exceptional Children, 54(5), 324–327. https://doi.org/10.1177/00400599221096974

Guay, F. (2022). Sociocultural Contexts and Relationships as the Cornerstones of Students’ Motivation: Commentary on the Special Issue on the “Other Half of the Story.” Educational Psychology Review, 34(4), 2043-2060. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-02209711-3

Paredes, M. (2022). 6 Strategies for Effective School Family Engagement Events. Retrieved from https://ies.ed.gov/ncee/rel/Products/Region/northwest/Blog/100806

Parent Square Blog (2023). 10 Ways to Improve Family Engagement in Schools. Retrieved from https://www.parentsquare.com/blog/10-ways-to-improve-family-engagementin-schools/

YouTube. (2016, March 8). Celeste Headlee: 10 ways to have a better conversation | ted. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R1vskiVDwl4

It’s the week of pre planning and you get a phone call at work. One of your upcoming students was diagnosed with cancer over the summer and will need accommodations at school during treatment. Or maybe the phone call shares that your upcoming student has a mother with stage 4 metastatic breast cancer. The family is hopeful that the student will be able to go to school as much as possible to have a sense of normalcy, but what is normal?

I am a counselor who is also a stage 3 breast cancer survivor. I have worked with students who have cancer, and students who have immediate family diagnosed with cancer. Immediate family in this case would be a mother, father, sister or brother. It was not until my own diagnosis that I ventured deeper into the world of cancer and supporting those affected by this diagnosis. Sometimes the ability to come to school was the only thing the students looked forward to. Other days going to school was a big thorn in their side with everything else that the family has going on. I often ask myself; if I hadn’t been affected by cancer myself, would I know what these students and their families need from their school counselor? Would I even know how to ask them if they need any support from the school? I wonder. . .

The truth is I won’t know that answer. I do know that having the experiences I had as school counselor and as a cancer patient, has been integral in my passion to support and advocate for students affected by cancer.

Cancer is a disease where abnormal cells start to divide uncontrollably and destroy body tissue. Today there are more than 200 types of cancer. In the United States 1 in 285 children from birth to age 19 are diagnosed with cancer. In adults there are more than 1.9 million in the US diagnosed with cancer. Each year at least 54% of families are directly affected by cancer. These striking numbers are the reason we as school counselors need to understand effective ways to support the people who are a part of this data research. (Data source: mayo clinic)

“If it was you. If it was your child. If it was your sibling. If it was your parent. What support would you want the school counselor to give?”

Overall, Cancer is scary. Most of us have not been directly affected by cancer. It’s hard for us to think about what support the family may need. It’s hard to want to ask the family what support they need. Sometimes it just seems easier to look the other way, but as school counselors we don’t. We won’t look the other way.

My hope for this article is to give courage to school counselors and encourage them to empathize and communicate. Those are the 2 best actions a school counselor can give to a family affected by cancer.

Gakobe and his twin brother Gioni were 8th graders with me during the 2022-2023 school year. Gakobe was diagnosed with Osteosarcoma in July of 2022. His treatment consisted of a leg sparing surgery where a rod was put in his leg and the bone with cancer was removed. He has had both oral and IV chemotherapy and radiation. He has some cancer that tries to spread to his lungs, but if he stays up to date with appointments and treatment with his oncology team, the spots have been treatable.

Most days Gakobe just wants to be a student. We created a 504 plan that included the option to receive hospital homebound services due to the side effects from chemo. I don’t think he used the home bound option one time during his 8th grade year. If he felt good enough to sit up and talk, he was coming to school. Overall, the teachers were supportive, but given our own fear of cancer, some teachers struggled to look beyond their own concerns. “Why is here today?” “ What if something happens?” “I can see the drain coming out of his leg.” Those were just a few comments from teachers. There were times when Gakobe would work in my room and fall in and out of sleep. It was ok. I was happy to have him at school. At least he has distraction at school. Gakobe became more sensitive to students joking with each other and playing around. Most days he didn’t want to talk about it, but on the days he did, I listened. When I would talk to Gakobe about school he would tell me that the classwork and assignments helped distract his mind. He wanted to do well in his classes, and it often became more of a priority than his cancer.

Gakobe is a lover of basketball. Him and his twin brother Gioni. Its their passion. Gakobe was not able to play in 8th grade because of cancer. This was heart breaking news for him. The coaches allowed Gakobe to still be on the team as an “assistant coach.” I don’t know if they realize what that meant to Gakobe. I would go to the games, and I would see him on the bench. He wasn’t crying. He wasn’t angry. He wasn’t pouting. He was cheering his team on. He was giving high fives and good jobs. He was pep talking the team and his brother. He was a part of the team and cancer was NOT.

On our last home game the principal at our school approved my request to honor Gakobe and all children who were cancer survivors during half time. It was an amazing evening. Gakobe helped me plan it, along with another student who was an osteosarcoma survivor. We had metals for all the children we acknowledged as survivors. We then acknowledged Gakobe and showed our support for him as he continues his cancer treatment. Then the most amazing thing happened. We asked for ANY ONE who was a cancer survivor, OR affected by cancer in some way to come to the court, and WOW did we have a crowd.

The stands became empty, as the court became full! I hope that was as special a day for Gakobe as it was for me. It was an opportunity to do something for someone who has taught me so much. To pay it forward. For once, to be the adult who is inspired by our students. Our students like my friend Gakobe.

This school year an 8th grade student Tristan, shared about the loss of his mother in 2021 to metastatic breast cancer. Tristan shares from a different lens. The child of a parent who is sick with cancer. An opportunity for counselors to learn what it can be like to be a child with a sick parent. Tristan is a very strong-minded young man. He has a foundation founded by God and faith to persevere through life’s challenges. I have a lot to learn from Tristan. I often wonder how he has been able to keep going, despite the trauma he endured. He says he finds himself more easily angered than before his mother passed away. He’s taken to Football and Basketball and finds moments of peace in being active with sports.

An avid honor roll student continues to be important for Tristan. One thing I notice as an adult on the outside looking in: He takes qualities he remembers and loves about his mom and works to have those same qualities in himself. It’s quite inspiring the way he looks up to his mom. The way he chooses not to play a victim in his circumstances. I truly feel like he knows his story is meant to inspire others. He is a young teen I am very proud of. He is resilient, mature, humble, and has a natural strength in being considerate. I like to think his mother looks down from Heaven and smiles at Tristan.

Cancer affects a whole family. It doesn’t only affect the person with the diagnosis. It changes the way we think. It changes our life routines. It changes are thought processes. It changes everything. We as school counselors advocate for all students. This includes students directly affected by cancer. They may not share what they need. They may not feel comfortable sharing such devasting news to others in school. Every day creates new challenges, new fears, new routines to create a new normal.

I close this article with a simple piece of advice:

Whether you have a student with cancer, a student who has a parent with cancer, or a student who has a sibling with cancer at school, sometimes you just have to let them BE!

Let them BE at school. Let them BE with friends. Let them BE with their emotions and work through them with their counselor, safely at school. Compliment them for coming to school. Encourage them to continue to do what is right. Remind them of how they are inspiring others. Let them BE a part of your world for a moment. And in that moment, BE there FOR them.

Mercer University

(Jordyn Alderman is a graduate Counseling student, Dr. Karen Rowland is a Professor of CounselingIntroduction

A crisis is an event that an individual perceives as an extreme difficulty exceeding their current resources and coping skills (Jackson-Cherry & Erford, 2018). According to Jackson-Cherry and Erford (2018), three essential elements must be present for an event to be considered a crisis: a precipitating event, a perception of the event leading to subjective distress, and diminished function when customary coping mechanisms or other resources do not alleviate the duress. This crisis may or may not lead to trauma or be perceived as disrupting one's life (Jackson-Cherry & Erford, 2018). The defining factor that could turn a crisis into a traumatic event or allow the person to work through the crisis is someone's perception of the event (Jackson-Cherry & Erford, 2018).

To differentiate between the types of crises that arise, they are identified into one of four domains: developmental, situational, ecosystemic, and existential (Jackson-Cherry & Erford, 2018).

Developmental crises are events most people are expected to experience during their developmental years. Situational crises are typically unexpected events that may be shocking, catastrophic, or random spontaneous acts. Ecosystemic crises occur naturally or due to human interference and impact the individual and the community systems connected to them. Lastly, existential crises affect a person's core beliefs, such as religion, purpose, and sense of meaning.

Crisis intervention models are designed to assist individuals, populations, and communities in working through the behavioral and cognitive symptoms of a crisis or catastrophic event (Jackson-Cherry & Erford, 2018).

To differentiate between the types of crises that arise, they are identified into one of four domains: developmental, situational, ecosystemic, and existential (JacksonCherry & Erford, 2018).

Developmental crises are events most people are expected to experience during their developmental years. Situational crises are typically unexpected events that may be shocking, catastrophic, or random spontaneous acts. Ecosystemic crises occur naturally or due to human interference and impact the individual and the community systems connected to them. Lastly, existential crises affect a person's core beliefs, such as religion, purpose, and sense of meaning.

Crisis intervention models are designed to assist individuals, populations, and communities in working through the behavioral and cognitive symptoms of a crisis or catastrophic event (Jackson-Cherry & Erford, 2018).

Losing a friend or family member can be jarring and cause immense distress in an individual's life. Sometimes, the loss of a loved one results from a completed suicide, which can elicit confusion, anger, shame, and guilt in the survivor (Jordan, 2015; Young et al., 2012). Suicide is a mental health crisis and is one of the leading causes of death among adolescents and young adults worldwide. Most suicides can be associated with a diagnosable mental disorder (Young et al., 2012). Even with proper treatment and support, there may be times when the efforts of loved ones and professionals cannot stop a person's suicidal thought cycle. Young et al. (2012) state that roughly 85% of people in the U.S. know or will know someone who has committed suicide. Just as the responses to grief vary from person to person, the reaction to losing someone through suicide could bring many emotions, even if one is not closely related to the person (Jordan, 2015; Young et al., 2012).

This paper explores the concepts of crises and complicated grief therapy through the use of a case study. Each step of complicated grief therapy is examined, with practical insights on implementing this therapy approach within the context of the case study.

Sage, a 15-year-old high school sophomore attending, is described as active in sports and clubs and excelling academically. She has a tight-knit group of friends who have known each other since the second grade, and all have attended the same school. Two of her best friends, Rene and Chloe, are on the cheer squad together and always share secrets. A month into their sophomore year, Rene passes away from a completed suicide, leaving Sage devastated, confused, and burdened with guilt.

The school responds by holding an assembly to address suicide, but to Sage and her friends, it feels more like Rene is being criticized for her actions. In the months following Rene's death, Sage struggles with conflicting emotions. She feels disconnected from her faith and conflicted about her feelings toward Rene. Sage experiences severe mood swings, declining grades, weight loss, and reluctance to discuss Rene. She blames herself for not recognizing signs or preventing Rene's suicide, yet she also feels anger and guilt for being upset with her friend. Despite missing Rene deeply, Sage is unsure how to navigate her complex emotions.

Complicated Grief Therapy

Complicated Grief Therapy (CGT) is a counseling approach designed for individuals experiencing prolonged and intense grief, characterized by intrusive thoughts, intense emotions, and difficulty accepting the loss of a loved one (JacksonCherry & Erford, 2018; Iglewicz et al., 2019; Wetherell, 2012; Shear et al., 2013). This approach targets individuals who may feel stuck or hindered in their grieving process. Grief typically progresses through two phases before returning to baseline functioning (Jackson-Cherry & Erford, 2018). The first phase, acute grief, involves the initial intense feelings following the loss, often characterized by sudden and overwhelming emotions. Integrated grief, the second phase, represents a more permanent adjustment to the loss, allowing for an understanding of life without the loved one and a return to satisfaction and interest in everyday life. However, when individuals cannot move from acute to integrated grief, they may develop complicated grief (CG) (Shear et al., 2013). CGT aims to assist individuals experiencing complicated grief, in transitioning from acute to integrated grief.

The CGT approach includes seven steps to facilitate this transition, including providing information about the diagnosis and counseling, assisting in managing emotional turmoil, helping students/clients envision a future without the loved one, facilitating reconnection with others, encouraging the sharing of memories, normalizing reminders of the loved one, and reassuring students/clients that reminiscing is a healthy part of the grieving process (Iglewicz et al., 2019; Shear, 2010; Shear & Bloom, 2016; Wetherell, 2012). By following these steps, school counselors can help students with complicated grief transition toward integrated grief, allowing them to regain satisfaction and interest in everyday life.

The first step of the CGT Model is for the school counselor to provide information about what they are experiencing. Since students may struggle to control their feelings due to the turmoil of acute grief, explaining the mechanisms of complicated grief very often serves as a relief in an otherwise constantly disruptive emotional state. This information step give students/clients the space to ask any and all questions they may have about the suicide and their emotions/reactions to it. The school counselor and students can us a collaborative approach to help them explore the different ways to reach the next stage (Iglewicz et al., 2019).

With the case study, Sage was referred by both her parents and teachers due to her experiencing profound grief following her friend, Rene's suicide. Sage disclosed feelings of intense sadness, guilt, and anger toward Rene. Her mother expressed concerns about Sage's academic focus, weight loss, and emotional well-being.

Utilizing an assessment instrument called the Complicated Grief Assessment, helped the school counselor in providing Sage with information on complicated grief. Sage’s homework was to begin a grief journal that included reporting on her emotions and reflections after each counseling meeting. The purpose for the journaling was to aid Sage in navigating her grief journey and equip her with coping mechanisms to manage her emotional reactions effectively.

Step

The second step involves assisting students/clients in exploring and navigating their emotions surrounding the loss. Students are encouraged to allow themselves to experience their feelings as they arise, which not only helps in the school counselor's understanding of the students' grief process but also allows students/clients to gain insight into their own emotional landscape (Iglewicz, 2019; Shear, 2010).

During this step, Sage's emotional challenges are addressed, focusing on her feelings of anger and resentment towards her deceased friend, Renee. The grief journal was reviewed to understand triggers and coping strategies. The school counselor also incorporated techniques of breathing exercises and scaling to help Sage with her emotional state.

Step

For step three the focus is on guiding students/clients to envision a future without their loved one and to set personal goals. Clients struggling with complicated grief may find it challenging to imagine a future without their loved one's presence.

. To assist students in this stage, the school counselor uses a CGT technique called imaginal revisiting with the aim to encourage the students to visualize a future where their grief is manageable and to also set achievable goals to work toward that vision (Iglewicz et al., 2019). These goals can be small, such as incorporating new activities into their selfcare routine, exploring different types of physical activities, reading regularly, or engaging in creative pursuits like coloring. The purpose is to create a rewarding and fulfilling future outlook for the grieving students to look forward to. During this step, Sage's grief journal continued to be reviewed. Additionally, the school counselor engaged Sage in sharing her aspirations and sources of joy since their last session. The school counselor emphasized the safe nature of the space and the collaborative effort in working through emotions. Imaginal revisiting was introduced, where Sage briefly visualized and recounted the moment she learned of Rene’s suicide. This exercise was recorded for reflection and journaling for the next session. To make this activity less daunting or traumatic for Sage, it was followed by an identified rewarding activity (for the client); coloring! The school counselor also noted that as Sage shared her feelings of anger and guilt about her friend's death, it became apparent that her emotions were more rooted in guilt than anger. Sage recounted learning about Rene's passing and struggling to comprehend the news. After sharing her story, Sage cried but appeared less overwhelmed. The school counselor helped Sage discussed coping strategies for when these intense feelings resurface, such as coloring, breathing exercises, listening to music, etc., to manage her emotions.

The fourth step involves facilitating students/clients in reestablishing connections with their support network. During this phase, the school counselor aims to motivate students to cultivate new relationships or rekindle existing ones, including with family members, friends, teachers, and/or community members. The objective is for students/clients to have at least one person (family, close friend or confidant), they can depend on for support (Iglewicz et al., 2019).

Rebuilding a support system encourages students/clients to envision a positive future and provide them with safe spaces outside of the school counselor’s office (Iglewicz et al., 2019; Shear & Bloom, 2017; Wetherell, 2012).

During this step, the school counselor had Sage engaged in various therapeutic activities, including reviewing the grief journal, discussing aspirations and sources of joy, practicing imaginal revisiting, and also the introduction of situational revisiting, a technique similar to imaginal revisiting. Situational revisiting consisted of Sage focusing on confronting places or activities she had previously avoided due to strongly associated emotions surrounding the loss of her friend, Rene. Through guided imagery (visualization), the school counselor had Sage share some of the places and activities that she and Rene enjoyed going to or doing but she no longer did. An example of one of the situational revisiting was having Sage visualized returning to her church’s youth group that she always attended with Rene.

After this visualization, Sage reflected on her thoughts and feelings with an encouragement from the school counselor for Sage to try going to the youth group for that week, staying as long as she could, then journaling about the experience

Additionally, this step also addressed Sage’s support system, exploring whether she had any safe spaces or supportive individuals outside the counseling office. Sage found it challenging to identify anyone beyond her parents, prompting the school counselor to help her consider other sources of support during this period. From this exercise, Sage was motivated to reconnect with her friend, Chloe who was also friends with Rene. Sage reported that this activity, highlighted the importance of having a supportive network for her present and future well-being.

Step

Step five involves encouraging students/clients to share stories about their loved ones. The school counselor gently prompts students to share the story of their loved one's passing in multiple sessions, aiming to facilitate better emotional regulation (Iglewicz, 2019). This process helps students/client accept the reality of their loss and adjust to a new life without their loved one (Iglewicz, 2019). A technique used in this step is revisiting, which involves exposing students to the event and then helping them set it aside (Shear, 2010). This technique is particularly beneficial for students experiencing CG, as they often fear that talking about the deceased person will perpetuate their pain (Iglewicz, 2019; Shear & Bloom, 2017; Wetherell, 2012). Although initially distressing, practicing remembering the person without becoming emotionally overwhelmed can help students/clients process their grief more effectively (Iglewicz, 2019; Shear & Bloom, 2017; Wetherell, 2012).

In this session, Sage shared photos and items (of her choosing), that reminded her of Rene, discussing the stories behind them. She was encouraged to express both positive and negative memories associated with Rene, aiming to help her talk about Rene without overwhelming emotions. The purpose was to help Sage accept the reality of Rene's absence and shift her focus to the future. Sharing the stories helped reduce triggers and also address Sage’s maladaptive cognitions.

During step six the purpose is to help students/clients live with reminders of their loved one (Iglewicz, 2019; Shear & Bloom, 2017; Wetherell, 2012). Although experiencing complicated grief may find reminders of their loved ones uncomfortable, these reminders are crucial in students/clients accepting the new reality of living without their loved one. The school counselor aims to encourage students to embrace these reminders, even though they may evoke painful or bittersweet feelings because ultimately, doing so leads to enhanced emotional regulation and the ability to feel sad without distress (Iglewicz, 2019; Shear & Bloom, 2017).

In this step, Sage continued the routine of journal sharing and reflections, engaged in storytelling to reinforce progress made in previous meetings, Sage shared that she had returned to youth group, had cried when her youth pastor and friends embraced her during the service, but she had stayed for the entire time and was glad that she had done so! The school counselor reassured Sage that it's okay to miss Rene and feel sad, and also encouraged her to begin to make new memories at the youth group and think fondly about the time spent there with Rene.

The final step of the CGT approach involves encouraging students/clients to reminisce as a form of reassurance. Following the loss of a loved one, individuals may struggle with feelings of permanent separation and the inability to interact with their loved one again (Iglewicz, 2019). However, engaging with memories such as photos, videos, and mementos can provide a sense of closeness and connection, even in the absence of physical presence (Iglewicz, 2019). This process can help alleviate feelings of loneliness and allow clients to remember their loved ones for who they were (Iglewicz, 2019; Shear & Bloom, 2017). It's important for students/clients to recognize that while their loved one is no longer physically present, they can still maintain a relationship with them through memories and shared experiences. This understanding can provide students/clients with peace of mind, knowing they can access these memories whenever they need to (Iglewicz, 2019; Shear, 2010).

The school counselor knew the meetings with Sage was coming to an end as Sage now knew their routine; she would eagerly share her weekly joys and confidently present her homework. While she found the assignments challenging, she acknowledged increased engagement with friends and improved grades.

References

During the final meeting, Sage bravely brought up the last picture she took with Rene, admitting she had avoided it for some time but felt ready to share this story.

As she recounted the memory, Sage displayed a range of emotions, expressing ongoing feelings of missing her friend. Despite acknowledging that she may always miss Rene, Sage noted that recalling memories of her was becoming less painful. Sage also tearfully expressed a fear of forgetting Rene as time moves on. The school counselor reassured her that Rene can always be remembered through photos, videos, memories, and stories.

Losing a friend can be a profoundly distressing experience, regardless of the circumstances or the depth of the relationship. For those left behind after a friend's suicide, the grieving process can become disrupted or stagnant due to overwhelming emotions and maladaptive thoughts. However, with proper intervention, they can access resources such as individual counseling, grief group counseling, safe spaces for open dialogue about their feelings, guidance on navigating their new reality, and strategies for envisioning a hopeful future.

Iglewicz, A, Shear, M., Reynolds, C., Simon, N, Lebowitz, B, Zisook, S. (2019). Complicated grief therapy for clinicians: An evidence-based protocol for mental health practice. Depress Anxiety. 2020; 37: pp. 90– 98. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22965

Jackson-Cherry, L. R., & Erford, B. T. (2018). Crisis Assessment, Intervention, and Prevention (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Pearson.

Shear M. K. (2010). Complicated grief treatment: the theory, practice, and outcomes. Bereavement care: for all those who help the bereaved, 29(3), 10–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/02682621.2010.522373

Shear, M.K., Ghesquiere, A. & Glickman, K. (2013). Bereavement and Complicated Grief. Curr Psychiatry Rep 15, 406 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-013-0406-z

Shear, M.K., Gribbin Bloom, C. (2017).Complicated Grief Treatment: An Evidence-Based Approach to Grief Therapy. J Rat-Emo Cognitive-Behav Ther 35, 6–25 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10942-0160242-2

Wetherell, J. L. (2012). Complicated grief therapy as a new treatment approach, Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 14:2, 159–166, DOI: 10.31887/DCNS.2012.14.2/jwetherell

Harmonizing Social and Emotional Learning: The Role of Music in

Christy Conley, cconley@oconeeschools.org

Kimberly Brown, kmercer9680@gmail.com

Do you believe you are immune from implicit bias as a school counselor? Do you think your personal preferences and circle of loved ones do not affect your work as a school counselor? Let’s take a deeper look and see if this is in fact true. Think about the people whom you would consider in your circle of trust. In your mind, list six to ten people you trust the most who are not family members. Review your list and identify the people in your circle of trust who have the same diversity dimensions as you. Who on your list is the same age, gender, race/ethnicity, nationality, region, speaks the same native language, or has the same professional background? Now evaluate; how many people in your circle of trust are very similar to you? As a result of this activity did you discover that your circle of trust displays minimal diversity and that the people you trust the most

include people with backgrounds similar to yours? If you did, do not fret you are not alone; this is true for most people, school counselors included.

Despite years of graduate education and training, school counselors are not immune from implicit bias. It can affect our work with students daily if we are not mindful of and

address it when present. Unconscious bias in schools has profound implications—when we make decisions on who gets recommended for advanced courses or selective programs, who gets awards or nominated for scholarships, who we select to develop as leaders or whose ideas we give consideration, we may be adding our own subliminal and emotional criteria to that decision. If left unchecked, school counselors who are not aware of implicit biases can be accomplices in creating unfair systems in our lives and in our work.

Implicit bias is prejudice in favor of or against one thing, person, or group compared with another, usually in a way considered to be unfair. It refers to unconscious stereotypes against others and how they affect our behavior. Implicit bias, aka unconscious bias, reinforces inequalities at work, school, and other areas of our lives. Unlike racism or sexism, people with implicit biases are often not aware of the ways that their biases affect their behavior. It is critical to understand that having implicit bias does not make you a “bad person”, but instead, understand the importance of acknowledging the bias and how it can affect the work of school counselors and educators. Recognizing implicit bias is vitally important because it can alter your decision-making process and how you interact with others.

Ongoing professional development and open and courageous conversations can assist school counselors and educators in learning how to identify their biases and not let them control their decision-making and daily interactions. Unlike implicit bias, which is an unconscious act or thought that is expressed indirectly, explicit bias is a bias that operates consciously and is expressed directly. One must be careful not to let implicit biases become explicit biases. This happens when one becomes consciously aware of the prejudices and beliefs one possesses. The examination of both implicit and explicit bias should be required internal work for school counselors because of how these biases can affect the work we do with students. While examining biases, school counselors should ask themselves, are they opening or closing doors? Are they serving as a contributor or a disruptor in their students’ lives? Are you allowing your biases to reinforce barriers and restrict opportunities for students or have you addressed your biases and are operating with the awareness of them to remove barriers and provide opportunities to students?

As a school counselor, it is important to recognize the role that bias can play in our work. Even if we are unaware, our biases can impact how we interact with students, advise them, and provide resources. In many ways, we dictate whether the doors of opportunity open or close for students. While biases are a part of human nature, it's important to be aware of our biases and work to overcome them so that we can provide fair and impartial support to all of our students.

When selecting students for leadership positions, it's important to ensure that the process is fair and free from bias. It's easy to fall into the trap of selecting students who fit a certain mold or have specific qualities that we deem desirable, but this can lead to a lack of diversity and leave out qualified candidates who do not fit the mold. Instead, we should evaluate each student based on their unique strengths and abilities. Our goal should be to find ways to support and encourage all students to develop their leadership skills. By doing so, we can create a more inclusive and equitable environment where everyone has the opportunity to succeed and thrive.

Access to academic opportunities can create a catalyst of options for students. Student course selection establishes rigor on a student's transcript. Academic Rigor and GPA are two of the most impactful aspects reviewed in a college application. Yet, there are disparities in understanding how course selection can significantly impact a student’s admissions status or ability to qualify for scholarships. Access to challenging courses in high school can prepare students for their future career aspirations

How does your school determine what class a student is recommended to take? Are there barriers to the honors or AP/IB classes? Does your school review the numbers of what types of students make up your rigorous classes? Is AP Potential used to help identify qualified students for AP classes who may otherwise be overlooked? Are you having discussions of ways to diversify homogeneous classes? Are those discussions turning into action? Implicit Bias can infiltrate many aspects of school counseling, noticeably in letters of recommendation. When writing a letter of recommendation as a school counselor, it is important to be aware of any biases that may impact the letter's content. Verna Myers said in her Ted Talk, “Biases are the stories we make up about people before we know who they actually are.” If we hold certain assumptions or stereotypes about the student we are recommending, it may unintentionally come through in the letter and affect the student's chances of being accepted into their desired program or school.

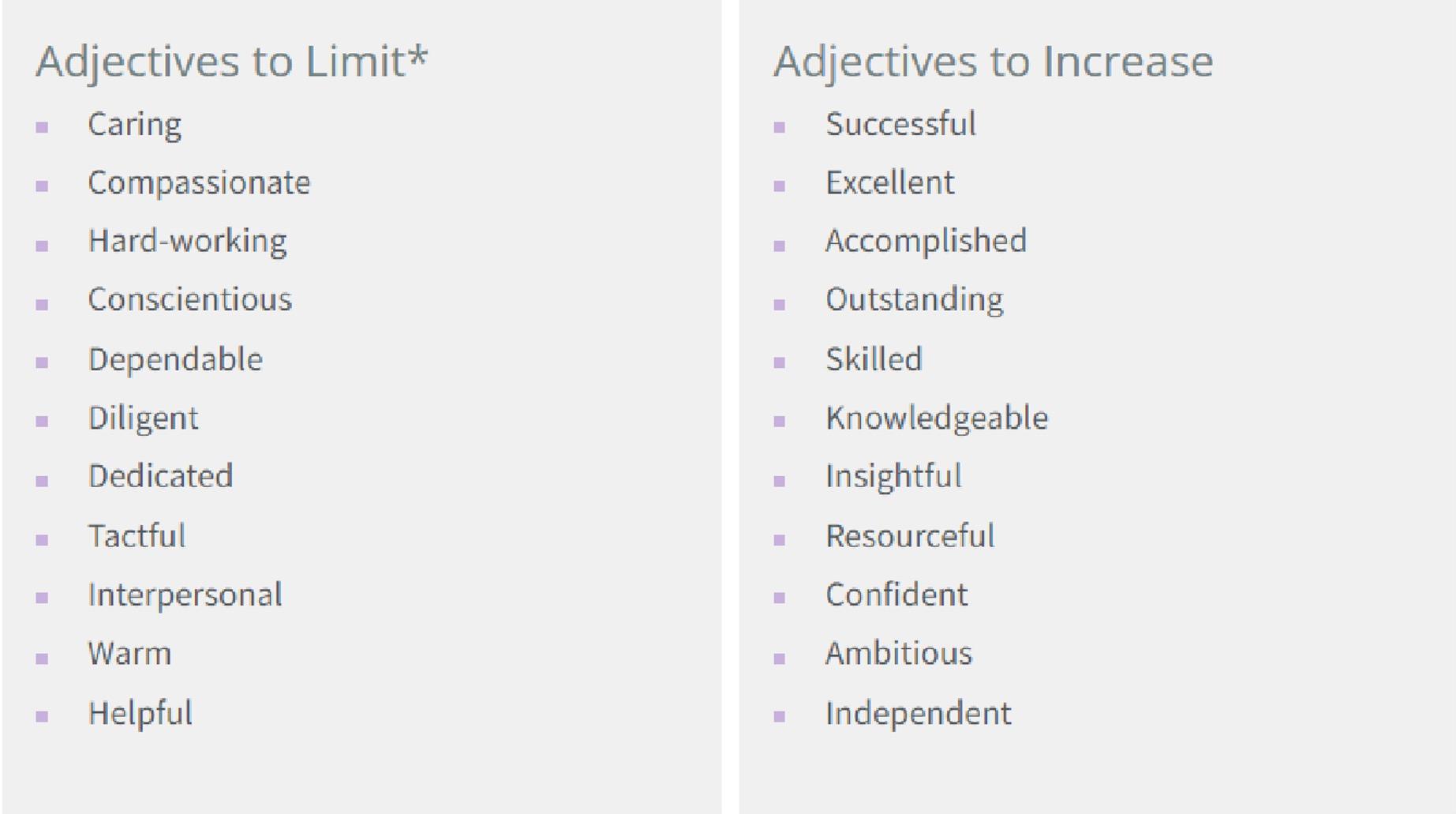

It is essential to focus on the student's strengths and accomplishments in a way that is fair and impartial, regardless of any personal biases we may have. Our language plays a significant role in how we paint our students' picture. Gender and racial bias are often found in letters of recommendation. A college representative gave a great tip to help counselors avoid this common pitfall.

If you are using a description of a student, apply that same description to a student of another race, gender, and/or background and see if it would fit. If a counselor finds that they are only applying the adjective “delightful” to female students and the term “leader” to male students, their biases may be showing.

Counselor letters of recommendation can often contain adjective biases in the areas of gender, race, sexual orientation, class, etc. Counselors should evaluate letters of recommendation to ensure that common biased adjectives are not themes within their letters. Northwestern University has published useful resources on how to write bias-free letters of recommendation. In their work, they suggest avoiding potentially biased language including certain adjectives to limit and to increase. School counselors can test their letters of recommendation using Northwestern’s gender bias calculator.

As someone who writes letters of recommendation, it is important for us to be mindful of our bias. There are many colleges that train their staff to be aware of biases and many that do not. As the reader of recommendations, college representatives will also have their own biases to contend with as they review files. Talking with college representatives about the ways implicit bias can impact the college admission process can be informative and insightful for both parties. Don’t be afraid to ask college representatives to review your letters of recommendation and share if biases are noticed in the letter. As school counselors, we must ensure that we are cognizant of our implicit biases and how they can affect not only our work, but most importantly the educational trajectory of our students. We must be responsible professionals and seek the needed training to learn how to ethically advise our students without letting our biases tell a story that does not show our students in the best light. Rather than relying on our own biases or assumptions about their abilities, it is essential for educators to recognize and challenge our own biases to ensure that all students have equal opportunities to pursue their passions and achieve their goals. Ultimately, by promoting fairness and inclusivity in the process, we can empower students to reach their full potential and succeed in their academic and professional pursuits.

Imagine waking up, hearing chaos resonate throughout your home, standing at your bus stop and feeling isolated, walking into your classroom where you are faced with overwhelming academic pressures due to learning issues, struggling to make and keep friends, and feelings of hopelessness and insecurity. Overwhelming is an understatement. These are just a few descriptors that our elementary students face on a regular basis. School counselors are on the front line to partner with teachers and administrators and provide a safe space for students at school experiencing such hardships.

Oftentimes, students who need support the most, have the most unusual way of requesting it: by acting out. School counselors see behavior through a different lens, one of curiosity. We often ask, “What is happening with this student?” “Did they have dinner?” “Are their basic needs being met?” “Was there a caring adult at home last night or this morning to see them off to school?” If the answer is no, we find resources to help meet that need. School counselors assist in decreasing classroom disruptions caused by unmet social and emotional needs. We see ourselves as bridge builders. We build a bridge between the student and the teacher, if needed, and between the student and their peers. We create and implement mentor programs that help students feel connected at school. One way that I make a difference every single day is to greet students upon their arrival at school. I strategically stand where every fifth grade student passes me to get to their classrooms. Students who have chronic attendance problems are identified and a targeted intervention is put into place. That intervention creates the opportunity for the student to check-in each morning with a friendly hello and then stamp their attendance incentive card. This program has been successful in connecting with students on a daily basis and if they are absent, being intentional about following up with the student upon their return.

Whether the intervention is a beginning of the day check-in or supporting a student through a life altering event, such as loss of a parent or sibling, school counselors bridge the gap in response to mental health crises our students face on a regular basis.

Knowing how to distinguish between these two types of tantrums help school counselors know how to respond to the dysregulated child most effectively. Responding to a child with reasoning to a tantrum in the downstairs brain may likely result in the child becoming physically agitated and, perhaps, aggressive. In addition, if an adult responds in the same fashion as the child, with an emotional response, there are now two people with unregulated, unintegrated brain responses (Payne, 2018). In this state, the child does not have access to the skills of the upstairs brain to respond in a more appropriate and regulated manner. The most effective response in this situation is to coregulate with the child, gaining their attention to engage in soothing responses and acknowledging their feelings. The concept here is to engage, not enrage. Demanding a behavior change to a child having a tantrum in the downstairs brain is going to enrage, which is not the goal. This is when the school counselor needs to engage the child. This allows the child’s brain to integrate (Seigel & Bryson, 2011).

To further illustrate, consider the case of Jarred. You get called to help a 1st grade student, Jarred, who is having a tantrum in the classroom. When you arrive, Jarred is emotionally dysregulated, having thrown several crayons on the floor as well as ripped up his worksheet. The signs of dysregulation indicate that Jarred is responding from the downstairs brain. In this moment, demanding or even suggesting to Jarred to pick up the crayons is likely to enrage him. We must engage here, connect and redirect. Use a calm, soothing tone. The school counselor can engage Jarred by saying something along the lines of, “I see that you are upset. Would you like to tell me about it?” You might still get an emotional response, “no”. Now is a good time to utilize the distraction strategy. You could say something like, “I see that cool soccer ball on your shirt. I like to play soccer. Do you like to play soccer?” When you can get a response, ask Jarred if he would like to take a break. Taking Jarred for a walk in the hallway serves as a break from the environment where the emotional stimulation occurred. Once Jarred is calm, the conversation can take place about the inappropriate behavior that Jarred exhibited and what Jarred can do more appropriately in stressful situations in the future. With Jarred now calm and the brain integrated, the discussion about cleaning up the mess Jarred made in the classroom can occur. Summary

Comforting the child in a downstairs brain tantrum does not mean that there are no consequences. It means that the child is not able to effectively process the information of consequences in these moments. Once the child is calm, consequences can be discussed. In addition to comforting the child, there is distraction. This occurs when the adult begins talking about something outside of the tantrum, such as a dinosaur on the child’s shirt, a wheel in a water timer, etc. Reclaiming a sense of calm when a child is amid a stressful situation can be difficult for many children. It is important that adults use the brain science of Dan Seigel to help guide their interactions when a child is responding to an undesired environment. Doing this work will teach children the process of integrating their brain so that they can in time be able to handle emotion provoking situations in the future.

References Payne, R. (2018). Emotional poverty. Highlands, Texas: Aha! Process. Siegal, D. & Bryson, T. (2011). The whole-brain child: 12 revolutionary strategies to nurturing your child’s developing mind. New York: Random House Publishing Group.

Research has shown exercise benefits both our physical and mental health. Although we know this is a true statement, schools often do not allow students to have adequate physical activity throughout the day. Physical education class is often limited to once or twice out of the school week. Some schools allow daily recess, but often students are excluded from participating due to their behavior. Many of the students whose behaviors often lead them to miss P.E., recess, or extracurricular activities are the children who would benefit from physical activity most. Students thrive in environments where they are active. Movement and physical activity have a positive impact on students’ academics, physical and mental health (Miller, et al. 2007). School counselors have the unique opportunity to help improve students’ overall well-being by infusing physical activity into their counseling programs.

Including physical activities in counseling programs such as yoga, running, walking, and sports can be rewarding and beneficial to both students and counselors. Students will enjoy the fun of the activity while working on skills that can improve their decision making, social skills, and overall, well-being. Counselors can benefit by having the opportunity to move, building positive relationships with their students, and adding variety to their counseling program.

Here are some practical ideas to get your counseling program on the move:

• Include an afterschool run club like Girls on the Run in your program. Girls on the Run is a non-profit organization that has programs for grades 3rd-8th. The program is a natural fit for school counselors because it includes a curriculum that includes social emotional learning lessons with physical activity. The program includes a culminating 5K race that will help to build girls selfconfidence and build sisterhood among the team members. Girls on the run has several studies that show the positive impact this program has on participants. Check out their website by visiting girlsontherun.org.

• Implement movement activities during small groups, individual sessions, and class counseling lessons. An easy example of this would the use of thumb balls as a getting to know you activity. Have students throw and catch balls and answer questions based on where their thumb lands on the ball. Have students step back each time the ball is catch as an added challenge. Go Noodle and Cosmic Yoga are great resources that include kid friendly exercise and dance videos.

• Start a morning energy or walking club for students. This can be a great way to encourage students to arrive at school on time while allowing students to participate in a morning movement activity. Energy clubs can include fun activities such as basketball, volleyball, dodgeball, walking, jogging, jump rope and more. This will be a great chance for school counselors to collaborate with physical education coaches and build relationships with students.

School counseling programs that include physical activity will be a welcomed addition to schools. Parents, staff, and more importantly students will appreciate improving their emotional and academic development through movement. Reed (2021) states that if youth include at least 60 minutes of physical activity in their daily routine there can be improve selfconfidence, leadership skills and decreased instances of depression and anxiety. School counseling programs that are on the move can have a lasting positive impact on their students and schools.

Miller, D. N., Gilman, R., & Martens, M. P. (2007). Wellness promotion in the schools: Enhancing students’ mental and Physical Health. Psychology in the Schools, 45(1), 5–15. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.20274 (2021, December 15). Physical Activity Is Good For The Body And Mind

Heatlth.gov. Retrieved March 29, 2024, from https://health.gov/news/202112/physicalactivity-good-mind-and-body

connect STEAM concepts with real-life scenarios, encouraging empathy and a deeper understanding of practical applications.

STEAM projects, ranging from DIY slime to nature scavenger hunts and model volcanoes, provide a platform for students to develop problem-solving, critical thinking, and creativity. Furthermore, collaborative projects that require diverse teams mirror real-world scenarios, preparing students for the future workforce. STEAM activities are fun! It gets students excited and curious about learning by making lessons engaging. But it's not just about having a good time; STEAM is like a brain workout. It helps students think hard, ask many questions, and find answers. This kind of thinking is super important for doing well in the future. STEAM is a captivating and enjoyable approach to learning, fostering an environment where students can explore their innate curiosity. STEAM goes beyond the traditional boundaries of subjects, encouraging students to integrate knowledge from various disciplines to solve real-world problems. By emphasizing hands-on activities, experiments, and creative projects, STEAM creates an interactive and dynamic learning experience that resonates with students of all ages.

One of the key benefits of STEAM education is its focus on cultivating critical thinking skills. Rather than rote memorization, students are encouraged to ask probing questions, analyze information, and develop innovative solutions. This approach prepares them for future challenges, where adaptability and problemsolving abilities are essential for success in a rapidly evolving world. In essence, STEAM education is not just about teaching facts and figures; it's about nurturing a mindset that values exploration, creativity, and analytical thinking. By making learning enjoyable and relevant, STEAM sets the stage for students to become lifelong learners equipped with the tools they need to navigate an ever-changing landscape and contribute meaningfully to society. Introducing service learning projects into the mix reinforces the importance of STEM in solving real-world problems, instilling a sense of social responsibility in students.

For school counselors, integrating STEAM with SEL into counseling small groups and core curriculum offers dynamic learning experiences. Don't worry, school counselors; you only need to understand how to follow directions! You do not need to have a STEAM background to facilitate lessons! Students follow simple directions for the STEAM activity, navigate interpersonal dynamics through collaborative projects, and develop better relationship skills and social awareness. Moreover, the challenges inherent in STEAM activities encourage self-awareness and selfmanagement as students grapple with problem-solving and project management.

Tesha is also an author whoalso writes STEAM lessons for school counselors

The Mental Health Effects of COVID-19 on Elementary Students and the Role

The COVID- 19 pandemic has caused damage to the mental health status of individuals everywhere. As a result of risk factors associated with quarantine and social isolation as well as the fear evoked by the nature of the event, internalizing and externalizing behavioral symptoms have surfaced in elementary students (Man Ng & Ling Ng, 2022). Keeping this in mind, it is imperative to consider the key role that the school counselor plays at elementary schools across the nation. School counselors are considered to be the mental health experts within the educational system (Pincus et al., 2021). As such, the significance of their role has grown exponentially since the onset of the pandemic. Specifically, researchers explain how the roles of school counselors continue to be crucial for supporting the mental health and social development of children since the COVID-19 pandemic (Pincus et al., 2021). In order to address the increase in anxiety, stress, depression, adverse childhood experiences, and suicide ideation in children, school counselors are faced with the imperative tasks of providing early intervention, prevention, and referrals to students (Pincus et al., 2021). According to Pincus et al.’s (2021) research findings, school counselors must continue to advocate for the purpose behind the school counseling program now more than ever.

In order for counselors to be what elementary students need them to during this time, they must collaborate with stakeholders as to further strengthen their position for the sake of the students. Prior research that has been completed on the topic of isolation has stated that there is a link between children’s social emotional concerns, mental health concerns, and the potential of career/academic achievement (Pincus et al., 2021).

Pandemic

As aforementioned, internalizing and externalizing behavioral symptoms have surfaced in elementary students since the onset of the pandemic (Man Ng & Ling Ng, 2022). This is believed to be a result of risk factors and adverse events experienced during the social isolation that have occurred. Internalizing behaviors can be characterized by those such as stress, anxiety, depression, grief, anger, irritation, withdrawal, and trauma related symptoms (Man Ng & Ling Ng, 2022). Externalizing behaviors can be defined as hyperactivity or inattention issues, conduct issues, and aggressive behaviors (Man Ng & Ling Ng, 2022).

The COVID-19 pandemic caused major disruptions to the positive behavioral development of children (Man Ng & Ling Ng, 2022). The thirty studies these researchers explored showed substantial percentage growth of negative internalizing and externalizing behaviors amongst various worldwide populations (Man Ng & Ling Ng, 2022). In conjunction, de Miranda et al.’s work suggests that children who experienced the pandemic in elementary school may be susceptible to negative long term mental health effects such as depressive, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress disorders. This article defines the COVID-19 pandemic as a “disaster” due to its irregular characteristics and the populations’ struggle to respond to it (de Miranda et al., 2020). Previous disasters have been studied at length and have allowed researchers to make predictions about how the pandemic will ultimately impact the long-term mental health of elementary aged children..

In de Miranda et al.’s comprehensive review (2020), data was collected from two separate non-systematic reviews, and fiftyone articles from those reviews were selected for this study. A formal systematic review was not possible at the time of the study due to how fresh the COVID-19 pandemic was when the article was written. These articles focus on various samples of children and adolescents. The mental health state of the children and adolescents in the studies were examined. Additionally, risk factors such as socioeconomic status, domestic violence, preexisting health conditions, children infected with COVID-19, and level of mental health support offered during the pandemic online were considered as probable pieces that play a part in the disaster of the pandemic (de Miranda et al., 2020). The study ultimately painted a picture of the mental health scene post pandemic. This work reveals that high rates of depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress have already been identified among children as a result of the pandemic, and could potentially be seen as long-term effects.

Grief has been an intensely prevalent internalizing behavior experienced by many during the COVID-19. Unfortunately, a large number of elementary aged children have experienced loss at some capacity due to the pandemic. Chacar et al. (2021) uses Brofenbrenner’s bioecological model as a means for discussing how children of varying cultural, educational, economic, and mental health backgrounds have been impacted by the phenomenon of grief in the midst of the COVID- 19 pandemic. The article specifically addresses populations of children who have experienced loss as a result of the pandemic.

The study also offers a review of factors affecting a child’s understanding of death and grief including developmental understandings, emotional responses related to death, fears related to death, and terror management theory. Chacar et al. (2021) concludes that children respond differently to the idea of death depending on their environments. The adults in the life of a quarantined child played a major role in the child’s ability to respond when experiencing grief. The behaviors of a child experiencing grief while living in an unhealthy environment during quarantine may have been more negatively impacted than a child living in a healthy environment (Chacar et al., 2021). Adults must provide safe spaces for children to express their emotions. They must also develop an understanding of how to help children identify, normalize, and express their reactions to loss (Chacar et al., 2021). Hence, having positive adult relations is monumentally important in the lives of today’s children as they develop coping skills relative to potentially damaging internalizing behaviors. Internalizing behaviors and externalizing behaviors have also been linked to sleep quality and length. Lokhandwala et al.’s (2021) research correlates the sleep behaviors of children with their ability to cope with hardships. Data that was found in this study was collected twice: Once before the pandemic between July 2019 and February 2020, then again during the COVID-19 pandemic from May 2020- June 2020 (Lokhandwala et al., 2021). During the study both overnight sleep and naps of elementary aged children were tracked. The coping skills that were measured included the categories of positive coping skills, negative coping skills such as emotional expression, and negative coping skills such as emotional inhibition (Lokhandwala et al., 2021).

The data points collected ultimately suggested that sleep timing and duration have ties with coping skills (Lokhandwala et al., 2021). The study also highlighted additional research that reductions in sleep quality and length have been found to predict a greater probability for mental health risks in elementary children (Lokhandwala et al., 2021). This evidence supports the notion that when children are sleep deprived or experience interrupted sleep due to stress, they are more likely to show internalizing and externalizing behaviors such as irritation, anger, inattention, and conduct issues in the event of challenging tasks. Children lacking sleep cope negatively in the face of daily difficulties (Lokhandwala et al., 2021). As a result, elementary aged children who experienced sleep issues due to stress during and post pandemic may still be experiencing negative mental health effects in schools today.

Students with disabilities are amongst some who have suffered the most from the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. One study by Lipkin et al. (2023) examines these effects. The participants in this study included a group of fifteen parents who have children ranging in age from five through sixteen with disabilities such as Autism, ADHD, Down Syndrome, and other significant learning disabilities. Data collection occurred through participant interviews, observations, and document analysis. The results of the study unearthed four major themes relative to the impact of covid-19 school closings on participants and their children with disabilities (Lipkin et al., 2023).

The themes included school connection, virtual learning challenges and benefits, potential impacts for students, and managing change (Lipkin et al., 2023). The study ultimately advocates for families with students who have disabilities by explaining the negative effects that the pandemic had on the academic and social/emotional development of these children. According to the study, the pandemic also caused immense levels of stress amongst these families, and it is of the utmost importance that school personnel are still choosing to prioritize supporting these families and their individual needs post- pandemic (Lipkin et al., 2023).

Negative internalizing and externalizing behaviors observed during and postpandemic can potentially be attributed to quarantine related risk factors such as extended screen time, sleep disturbances, less physical activity, unfavorable family environments, and lack of school connectedness (Man Ng & Ling Ng, 2022). In general, parents and caretakers are major players when it comes to posing potential risks involved with children’s mental health issues (Adegboye et al., 2021). Unfortunately, parents and caretakers of children have also experienced unprecedented hardship since the arrival of the pandemic. Financial strain was placed on families during the pandemic (Adegboye et al., 2021).

This is yet another factor has affected children’s mental health levels through the way it has directly manifested in parents and caretakers. The direct factor impacting child anxiety in this case is parental mental health, which is caused by financial strain pandemic (Adegboye et al., 2021).

Viner et al.’s (2022) research on children and adolescent wellbeing during the pandemic pointed out that parental physical health behaviors and child abuse play a part in this as well. Viner et al. (2022) indicated that one major risk factor involved in the increase of mental health issues for children could be child abuse. Viner et al. (2022) completed a narrative synthesis of reports from thirty- six different studies that focused on the mental health effects on children during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. Within their study, several risk factors were identified as possible key issues during this time. Viner et al. (2022) highlighted a study a study that reported the number of child abuse referrals fell by about 27% during quarantine. Although the idea of referrals dropping may seem like positive improvements, when one takes a closer look into the deeper meaning behind this it is plain to see that school closures played a chief role in the lack of referrals noted. In other words, because schools shut down, mandated reporters such as school staff personnel were no longer seeing students face to face, therefore, abuse reports plummeted from their norm. Similar findings were reported in another study reported in Viner et al.’s (2022) work. Researchers in the UK estimated that child protective medical referrals were reduced by around 36% to 39% due to school closures (Viner et al., 2022). This poses a major question: if reports of child abuse paired with protective medical referrals dropped by significant values during school closures throughout the pandemic, how might that have an impact on children in our world today? When a child experiences abuse, their mental health will suffer as a result. Future studies could be completed to draw more direct connections between the longterm mental health effects of COVID-19 based on the aforementioned risk factors involved.

The negative mental health effects that have ensued as a result of the pandemic are a cause for proof that specific and strong interventions are needed to support suffering elementary students. Gkatsa (2023) conveys the strong need for the implementation of resilience intervention strategies specifically for populations of children and adolescents in both the general population and with special needs who have experienced anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress relative to the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. In this systemic review, Gkatsa (2023) analyzes ten articles to extract data relative to resilience interventions that were applied to the defined populations within different phases of the pandemic. The most effective interventions that were identified in the review included trauma informed intervention, an eight-week fitness intervention, interventions involving the use of digital technology, specific psychological interventions, and Trauma Informed Positive Education (TIPE).

These intervention strategies support the need for student psychosocial support and are encouraged for use amongst communities and school counselors worldwide. In this section, three of the aforementioned specific interventions are reviewed for their effectiveness in regard to helping children strengthen their mental health post pandemic. Trauma informed intervention involves all members of the school setting. The resilience-based intervention recognizes that all members of the school system have felt the impact of a certain trauma. In this case, that trauma is COVID-19. Halladay Goldman et al. (2020) developed a list of trauma informed practices for school personnel to practice during the pandemic.

The trauma informed approach allows schools to create a structured framework for how to handle infusing trauma awareness, knowledge, and skills into their classrooms, climate, and community (Halladay Goldman et al., 2020). The goal of the intervention is to create an atmosphere that supports the physical and psychological safety of school members, while simultaneously facilitating the adjustment and recovery processes of children within the school so that they can continue to grow positively (Halladay Goldman et al., 2020).

Another intervention that has been successfully utilized within education since the pandemic is Trauma Informed Positive Education (TIPE). Within schools, TIPE promotes the student-teacher relationship and its ability to strongly impact student wellbeing (Brunzell et al., 2021). It focuses on teacher wellbeing, which connects directly with student wellbeing. Teacher intervention approaches within TIPE include gratitude practices, stress management programs, development of intentional coping strategies, resilience, optimism, hope, and mindfulness- based stress reduction (Brunzell et al., 2021). These interventions targeted at teachers have been found to boost teacher wellbeing, which ultimately impacts student wellbeing (Brunzell et al., 2021). Brunzell et al. (2021) completed a qualitative study on the impact of TIPE with a group of early childhood educators in Australia. After teachers participated in TIPE interventions, several positive themes emerged. Teachers were able to notice trauma-exposure responses, learned how to put their wellbeing and self-care practices first, improve their relationships with students and staff, develop their own positive character traits further, and more (Brunzell et al, 2021).

Brunzell et al. (2021) concluded that effectively teaching students and supporting them in their traumas within the realm of education starts with leaders and teachers within school buildings. Once teachers understand the importance of noticing trauma within others and knowing how to intervene, a stronger and safer school climate can be created. The school counselor plays a critical role in this as well. School counselors have the leverage to introduce TIPE and other types of interventions to their administration and school staff. It is important that school counselors are vigilant in selecting the correct interventions for their student populations.

The pandemic had a physical impact on children as well. Because physical and mental health are closely related, the lack of physical activity children took part in during the COVID-19 isolation period may have impacted their mental health. During the pandemic, physical activity declined due to various factors. A study completed in Italy focused on providing a physical fitness intervention for thirty young adolescents over the span of eight weeks. Throughout the duration of the study, data was collected through physical fitness tests accompanied by a psychological measure with the Regulatory Emotional Self- Efficacy scale (Cataldi et al., 2021).

As a result, a positive correlation was found between the improvement in the participants physical fitness and their mental health (Cataldi et al., 2021). Researchers concluded that schools should implement motor and motivational programs to support the growth of the physical and mental health of students post pandemic.

This paper aimed to connect the dots between significant elements that have affected the mental health of elementary students since the COVID-19 event. As time passes, studies on this topic have expanded. There is increasing research to support the observations and experiments that have found evidence to support that many students have experienced difficulties in regulating internalizing and externalizing behaviors. These behaviors impact both the mental and physical wellbeing of students. Anxiety and depression rates climbed due to various factors throughout the pandemic. If children were in unhealthy home environments that lacked appropriate parental support during the pandemic, they may have had greater exposure to factors putting them at risk for a mental health decline. In order for children impacted by the pandemic to have opportunities for recovery and growth, adults must step up and become strong figures in their lives. Studies have indicated that there is a broad need for specific interventions to be put in place at schools for students with mental health needs since the pandemic. Within schools, school counselors have the unique opportunity to offer brief intervention and prevention sessions to students that may aid in the process of recovering from the pandemic’s effects. Understanding the risk factors that could be attributed to COVID-19 effects on the mental health of elementary students has caused school counselors and other school staff to work harder than ever to ensure that students are provided mental and emotional support.

References

Adegboye, D., Williams, F., Collishaw, S., Shelton, K., Langley, K., Hobson, C., ... & van Goozen, S. (2021). Understanding why the COVID-19 pandemic-related lockdown increases mental health difficulties in vulnerable young children. JCPP advances, 1(1), e1 2005.

Brunzell, T., Waters, L., & Stokes, H. (2021). Trauma-informed Teacher Wellbeing: Teacher Reflections within Trauma-informed Positive Education. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 46(5). https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2021v46n5.6

Cataldi, S., Francavilla, V. C., Bonavolontà, V., De Florio, O., Carvutto, R., De Candia, M., Latino, F., et al. (2021). Proposal for a Fitness Program in the School Setting during the COVID 19 Pandemic: Effects of an 8-Week CrossFit Program on Psychophysical WellBeing in Healthy Adolescents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(6), 3141. MDPI AG. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18063141

Chachar, A. S., Younus, S., & Ali, W. (2021). Developmental Understanding of Death and Grief Among Children During COVID-19 Pandemic: Application of Bronfenbrenner's Bioecological Model. Frontiers in psychiatry, 12, 654584. de Miranda, D. M., da Silva Athanasio, B., Oliveira, A. C. S., & Simoes-e-Silva, A. C. (2020). How is COVID-19 pandemic impacting mental health of children and adolescents?. International journal of disaster risk reduction, 51, 101845.

Gkatsa, T. (2023). A Systematic Review of Psychosocial Resilience Interventions for Children and Adolescents in the COVID-19 Pandemic Period. Journal of School and Educational Psychology, 3(1), 34–48. https://doi.org/10.47602/josep.v3i1.35

Halladay Goldman, J., Danna, L., Maze, J. W., Pickens, I. B., and Ake III, G. S. (2020). Trauma Informed School Strategies during COVID-19. Los Angeles, CA, and Durham, NC: National Center for Child Traumatic Stress.

Lipkin, M., & Crepeau- Hobson, F. (2023). The Impact of the COVID-19 School Closures on Families with Children with Disabilities: A Qualitative Analysis. Wiley Online Library, 60(5). https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22706