The fastest, smoothest, most powerful professional photo editor for macOS, Windows and iPad

The fastest, smoothest, most powerful professional photo editor for macOS, Windows and iPad

The special edition of the RPS Journal celebrating the Society’s awards is always the most challenging and exciting issue of the year. This one, though, has for me been the most memorable of them all.

From the moment the RPS shared its list of 2022 awards recipients, I knew this would be a visually striking edition, offering some wonderful stories from those being honoured. Once the interview requests were in, we looked forward to creating something special for RPS members –provided that some of the world’s most accomplished image-makers responsed with that magical ‘yes’.

Then, during the afternoon of 8 September 2022, it was announced that Queen Elizabeth II had died at her beloved Balmoral estate in Deeside, Scotland. That evening, we mulled over how we might honour the UK’s longest-serving monarch –and Patron of the RPS from 1952-2019. As many blinked in disbelief that this Elizabethan age was over, we conceived a visual tribute involving portraits of The Queen by RPS Honorary Fellows including Cecil Beaton, Rankin and Eve Arnold, along with other landmark images.

The results show how the image of Queen Elizabeth evolved over more than seven decades – from beautifully constructed symbols of regality such as Beaton’s 1953 coronation portrait to the cheeky portrait by Rankin HonFRPS released as part of the Golden Jubilee 2002 portfolio. What is almost certain, though, is that whichever esteemed photographer was creating her portrait, there was one person in charge.

Besides honouring Queen Elizabeth, this issue also celebrates innovative image-makers working in genres from science to art and documentary to film. Our cover is by Nadine Ijewere, who receives the RPS Award for Editorial, Advertising and Fashion Photography. The first Black woman photographer to shoot the cover of Vogue, Ijewere is changing the way beauty is defined.

Babak Tafreshi receives the RPS Award for Scientific Imaging with stunning nightscape pictures that pay particular attention to light pollution. And the RPS Vic Odden recipient Carly Clarke gives a moving insight into surviving Hodgkin lymphoma.

We hope you enjoy the feast of talent this issue. You can meet more of the RPS Awards recipients in our pages during 2023.

KATHLEEN MORGAN Editor

‘The Queen and the two princesses at Windsor’, c 1943, by Cecil Beaton HonFRPS/Royal Collection Trust/ His Majesty King Charles III, 2022

WITH THE RPS

Hoda Afshar stretches the borders of the documentary form with her latest series Speak the Wind, exploring a little-known culture and how humanity interacts with place in spiritual and historical ways

A visual tribute to Her Majesty The Queen, whose 70-year reign was captured in images by some of the greats, including RPS Honorary Fellows Cecil Beaton, Rankin, Patrick Lichfield and Martin Parr

As the world rediscovers the work of Ming Smith, the Honorary Fellow selects the work that make her most proud from a back catalogue of beautiful, tender images of everyday Black life and cultural icons

An Indigenous Australian photographer and artist, Destiny Deacon HonFRPS explains why she satirises racist stereotypes and explores political issues in work that blends autobiography and fiction

624

AWARD FOR SCIENTIFIC IMAGING National Geographic photojournalist Babak Tafreshi bridges the gap between art and science with images that explore global nightscapes and expose light pollution

Documentary photographer Carly Clarke was focusing on other people’s lives when she was diagnosed with Hodgkin lymphoma in 2012. Her response was to turn the camera on herself. She shares her journey of fear and hope

She was the first Black woman photographer to shoot the cover of Vogue. Nadine Ijewere explains why she challenges mainstream concepts of beauty

fr

RPS House, 337 Paintworks, Arnos Vale, Bristol BS4 3AR, UK rps.org frontofhouse@rps.org

+44 (0)117 316 4450 Incorporated by Royal Charter

Patron

HRH The Princess of Wales

President and Chair of Trustees

Simon Hill HonFRPS

Deputy Chair

Mathew Lodge LRPS

Derek Trendell FCA ARPS

Mónica Alcázar-Duarte, Nicola Bolton ARPS, Gavin Bowyer ARPS, Sebah Chaudhry, Sophie Collins LRPS, Sarah J Dow ARPS, Andy Golding ASICI FRPS, Mervyn Mitchell ARPS, Dr Peter Walmsley LRPS

Evan Dawson Directors

Development: Tracy Marshall-Grant Finance and HR: Nikki McCoy Programmes: Dr Michael Pritchard FRPS

The Journal of The Royal Photographic Society

Kathleen Morgan

rpsjournal@thinkpublishing.co.uk 0141 375 0509

Rachel Segal Hamilton

Art Director John Pender

Managing Editor Andrew Littlefield

Deputy Editor Ciaran Sneddon

Advertising Sales Elizabeth Courtney elizabeth.courtney@thinkpublishing.co.uk 0203 771 7208

Client Engagement Director

Rachel Walder

Circulation

10,604 (Jan-Dec 2020) ABC ISSN: 1468-8670

November / December 2022 Vol 162 / No 6

Published on behalf of The Royal Photographic Society by Think, 20 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JW thinkpublishing.co.uk

© 2022 The Royal Photographic Society. All rights reserved.

The ‘RPS’ logo is a registered and protected trademark.

Every reasonable endeavour has been made to find and contact the copyright owners of the works included in this publication. However, if you believe a copyright work has been included without your permission, please contact the publisher. Views of contributors and advertisers do not necessarily reflect the policies of The Royal Photographic Society or those of the publisher. All material correct at time of going to press.

GemmaPadley(page606)

Padley is an editor, journalist and author whose clients include Getty Images and Magnum Photos. Her latest book is New Photography of the Bird (Hoxton Mini Press)

EvaClifford(page616)

Clifford is a photographer who has written on photography and current affairs for sites and publications including huck and British Journal of Photography

TeddyJamieson(page632)

An award-winning journalist based in Scotland, Teddy Jamieson was born in Germany and raised in Northern Ireland. He is the author of Whose Side Are You On? (Yellow Jersey)

On 2 October 2022 the photography community lost a formidable force. Eamonn McCabe, who died suddenly aged 74, was a celebrated photographer and picture editor, while his influence as a mentor was also felt by many.

Joining the Observer newspaper in 1976, McCabe discovered his first passion –sports photography. Writing in the Guardian in 2009 about his life in pictures, he chose the image here as one of his all-time favourites. The hands are those of Sylvester ‘The Master Blaster’ Mittee – a big name in British boxing during the 1970s and 1980s. McCabe met Mittee in a cramped gym near King's Cross, London, in 1984, and the closeup was captured as the boxer was preparing to spar.

McCabe later commented that other people’s attempts to recreate the image had been let down by too much preparation or production: the magic lay in the rough and readiness of the original.

In 1988 McCabe became head of photography for the Guardian. He was to be named picture editor of the year a record six times before returning to photography and focusing mainly on portraiture for the Guardian and Observer. There are 29 examples of his work in the collection of the National Portrait Gallery, London.

McCabe was able to share his lifelong passion for photography in the 2017 BBC series Britain in Focus.

Bullfighting, fishing and Franco’s legacy – this is the varied territory to be explored by Owen Harvey, Tessa Bunney and Jordi Jon Pardo, recipients of this year’s RPS bursaries.

The Joan Wakelin Bursary, run in partnership with the Guardian, is awarded to documentary photographer Owen Harvey. His project, Death in the Afternoon in Seville Spain, follows contemporary matadors in training,

examining the significance of bullfighting to their identity. Aljohara Jeje, Lungisani Mjaji and Marissa Roth FRPS were shortlisted for the bursary.

“I was looking for projects I felt really embodied the subjects I am interested in.

A lot of my work explores family, heritage and notions of masculinity,” says Harvey, who has also photographed mod, punk and skinhead subcultures, young fathers with their children, and the British seaside.

“The financial support helps with the production of the project but equally importantly is the guidance from top picture editors. Having the support of the RPS and the Guardian is a huge help and will allow me to present the work to a wider audience.”

Tessa Bunney, a UK-based photographer who has chronicled rural life for 25 years, receives the RPS/TPA Environmental Bursary to expand the work she has been doing for four years with English fishing communities.

Photographers emerging and established are invited to submit their images to this themed award run by 1854 Media. The contest offers a platform to have your work shown internationally – previous editions have been exhibited at the Galerie Huit Arles, France. Deadline is 31 January 2023. 1854.photography/awards/ openwalls

A new competition from the RPS Women in Photography Group, aimed at female-identifying image-makers of all levels. Open call is 1 November to 15 December 2022, with top submissions exhibited at RPS Gallery in March 2023. rps.org/wip

This prestigious annual prize is for anyone specialising in wildlife and nature photography, whether professional or amateur. Categories include Plants and Fungi, Animal Portraits and Under Water, among many others. Closes on 8 December. nhm.ac.uk/wpy/competition

“I’m fascinated by location-specific fishing techniques, stories and traditions, the lives of fishing families past and present and the landscape in which they work,” she says.

In May 2022, fishermen from Teesside and the Yorkshire coast staged a protest against dredging, which they argue unearths toxins that kill the crabs and lobsters on which their livelihoods depend. Bunney’s project, Save Our Seas, will explore this story in depth.

Ecological crisis is also at the heart of Jordi Jon Pardo’s Postgraduate Bursary-winning project Eroding Franco. It looks at the

desertification currently unfolding in Spain and, through photographic documentation and archival research, links this to scientific findings that were released but ignored in the 20th century under Franco’s regime.

“Today we know that 80% of Spain will become a desert by the end of the 21st century,” says the Barcelona-based journalist and documentary photographer. “The project’s objective is to raise awareness about the environmental risks and problems that collectively implicate us as human beings.” owen-harvey.com tessabunney.co.uk jordijon.com

‘The gods will not be blamed’ by Christopher Iduma, Single Image winner, OpenWalls 2021

‘Margaret Owen, haaf netting, Lancashire, 2018’ from the series Going to the Sand by Tessa Bunney

Below

‘Barcelona, October 2016’ from the series Eroding Franco by Jordi Jon Pardo

Bottom

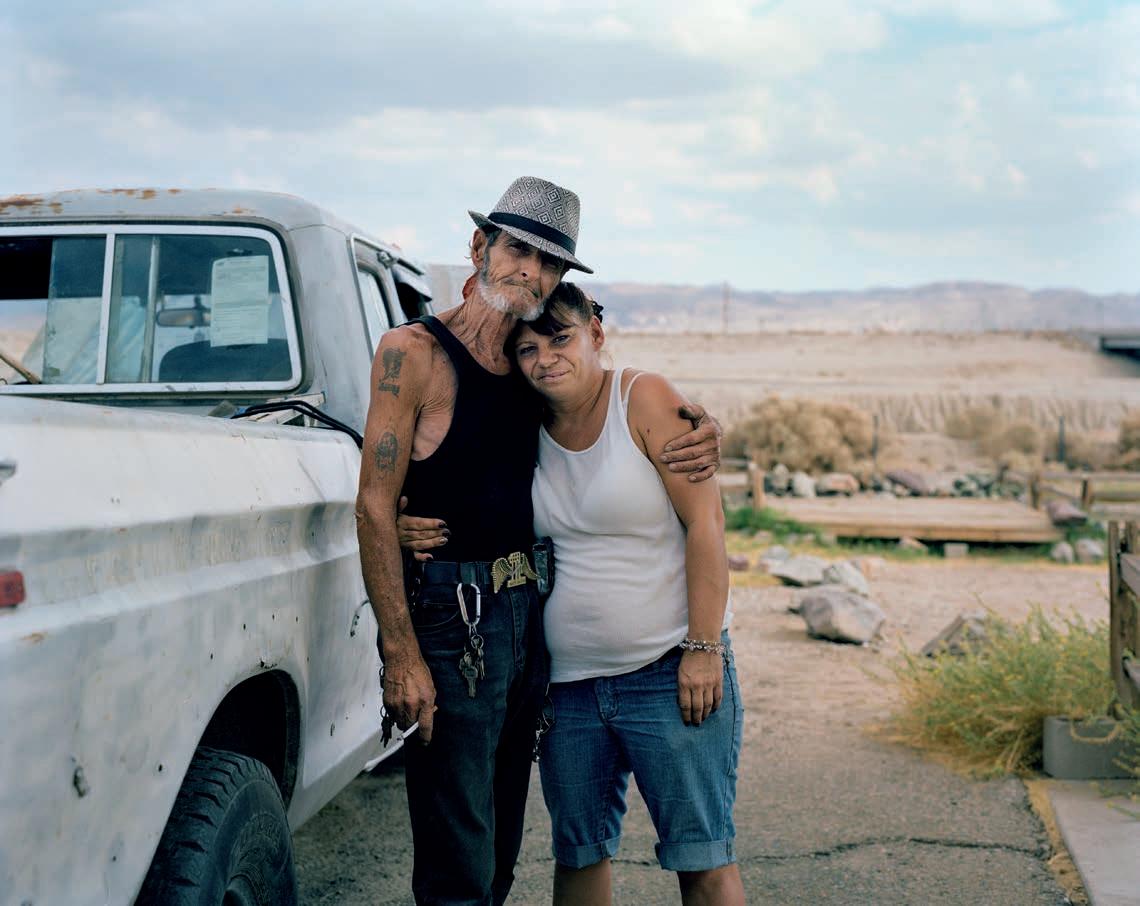

‘Finn and Liz’ from the series Skins and Suedes by Owen Harvey

An image by American wildlife photographer Dennis Stogsdill of a rarely seen caracal carrying a flamingo in its jaws beat more than 8,000 entries to take the title of Nature TTL Photographer of the Year and win £1,500 prize money. The competition reopens for entries in January 2023. naturettl.com

The Folio Society has released the first illustrated edition of Susan Sontag’s hugely influential book On Photography, originally published in 1977 and a mainstay of every photography degree syllabus. The pictures include images by Edward Steichen, Dorothea Lange and Diane Arbus. foliosociety.com

Founded by author L J Ross, the Northern Photography Prize celebrates the finest amateur photography depicting the ‘heart’ and ‘spirit’ of the north of England. The shortlist and winners are now available to view at the link below, along with more information on the prize. ljrossauthor.com/philanthropy/ northern-photography-prize/

Frederic Aranda FRPS and Carolyn Mendelsohn will blaze a trail in the inaugural programme

The RPS has launched an ambassadors programme with photographers Frederic Aranda FRPS and Carolyn Mendelsohn at the helm. Tracy Marshall-Grant, development director of the RPS, says, “We have so many talented and inspiring members in RPS and so many who have such amazing stories to tell about their photography journeys with us. Frederic and Carolyn have generously agreed to be the 2022/2023 ambassadors, and to share their experiences and their work with us throughout the year.”

Aranda, who is self-taught, creates editorial and commercial portraiture for clients such as Harper’s Bazaar and the Royal Ballet. He sees this as an opportunity to give something back to a photographic community that helped him grow creatively.

“I have met some wonderful people through RPS and some very inspiring photographers, who have been very kind and supportive from day one,” he says. Remembering the early days when

he was yet to connect with the industry network, he adds: “My journey as a photographer would have been a lot smoother had I known others I could turn to in those tricky times.”

Renowned for her commercial and documentary portraiture – in particular the book and exhibition Being Inbetween which focused on girls aged 10-12 –Mendelsohn also looks forward to sharing her experiences through the ambassador role.

“I didn’t have a straightforward journey into photography, but when I picked up a camera and started using it, it transformed my life at what was quite a challenging time,” explains the IPE 159 Gold Medal winner who is enthused about the Society’s work with younger people from all backgrounds.

“The RPS is an extraordinary organisation, with a forward-facing commitment to encourage, celebrate and nurture all photographers –from absolute beginners to seasoned professionals. I am proud to be part of it.”

National History Museum, London

Until 2 July 2023

The latest edition of the prestigious competition is on show, with 100 extraordinary photographs of nature and wildlife. This year, the space has been reimagined with video and scientific insights interwoven with the imagery to encourage viewers to consider the urgent actions humanity must take to protect nature. nhm.ac.uk

The Horsebridge Arts Centre, Whitstable

Until 28 November

Graves Gallery, Sheffield

Until 24 December

“For me home is somewhere that you take with you,” says Sheffield-born Johny Pitts. This project is the result of a journey taken by Pitts and the poet Roger Robinson around the British coastline in search of contemporary Black Britain. Shots of shops, streets and parks act as a meditation on community life. museums-sheffield. org.uk

Jerwood Space, London

Until 10 December

An exhibition of new commissions produced by winners Heather Agyepong and Joanne Coates. Deepening her interest in performance and the self, Agyepong’s ego death is inspired by Carl Jung’s notion of the shadow. In The Lie of the Land, Coates investigates the rural landscape of north-east England through the prism of gender and class. jerwoodspace.co.uk

A celebration of abstract and expressionist tendencies in contemporary photography, this group show brings together work by Valda Bailey, Doug Chinnery and 12 photographers from the UK, Europe and North America, among them many RPS members. A programme of talks accompanies workshops and the show. arbnexhibition.co.uk

The Martin Parr Foundation

Until 18 December

5 in Leicester there’s a predominantly South Asian area known as ‘The Golden Mile’. Pujara grew up nearby but left for London at 18 before returning as an adult. Taking these images helped him reconnect with his past. martinparrfoundation. org

A brand new 26.1 megapixel imaging sensor combines our existing back-side illuminated technology with a stacked, layered structure that quadruples readout speeds for faster image processing capabilities.

Ready to go. Made for movement.

X-Trans CMOS 5 HS is capable of blackout-free bursts of up to 40 frames-per-second. In burst mode, the sensor's phase-detection pixels are controlled independently from the image display.

X-H2S also supports 4K/120P high-speed video. Now, fast-moving subjects can be recorded in incredible detail for high-quality, slow-motion footage. Increased video recording time of up to 240 minutes of 4K/60P video.

The Magnum Fellow’s work on Latin America has appeared in TIME, Le Monde and the New York Times. She is the 2022 recipient of the 12th Carmignac Photojournalism Award, given by Fondation Carmignac to support Ferrero’s study of her home country, Venezuela. fabiolaferrero.com

VISUAL POET

Christian’s work is a celebration of their queer identity, focused on the communities to which they belong. The Cape Townbased artist is a finalist in this year’s Taylor Wessing Portrait Prize; an exhibition runs at Cromwell Place arts hub, London, until 18 December. cromwellplace.com

Baqué is one of two photographers to be awarded a 2022 Getty Images and Dove #ShowUs grant. Madridbased Baqué will receive $5,000 to create new work on the theme ‘Beauty has no age limit’, focusing on women in their 50s to 70s. instagram.com/ irenebaque IRENE BAQUÉ BY GABBY LAURENT; FABIOLA FERRERO BY STEFAN POZZEBON

The title of Bird Photographer of the Year 2022 has gone to this Norwegian nature photographer whose winning image features a rock ptarmigan cruising over the mountains above Tysfjord, Norway. Haarberg also won a Gold Award in the category Birds in the Environment. haarbergphoto.com

While interning at a studio in Atlanta, the Morrocan-Dutch photographer started working on a project about dancers at the strip club Magic City. Benjida’s series has now won the BJP International Photography Award – previous winners include Jack Latham and Vic Odden recipient Juno Calypso. 1854.photography

Prestel (£39.99)

Every generation rewrites history according to their own experience. The cultural and social landscape in which we find ourselves provides us with the lens through which we understand the past.

Here we have a new photographic history from Phillip Prodger, former head of photographs at the National Portrait Gallery, London, now executive director at Curatorial Exhibitions in LA. Since 2010 Prodger and his colleague Graham Howe have discussed the prospect of a survey that “capitalised on the incredible research performed in recent

decades by scholars around the world, featuring women, people of colour, and the rich variety of underappreciated traditions worldwide.” It would look “anew at already famous artists, engaging not just their most famous bodies of work but other, equally powerful projects.”

To this end, the pair began building the remarkable Solander Collection – vintage prints spanning nearly 100 years from the late 19th century onwards that underline the inclusivity of the medium.

An Alternative History of Photography takes readers on a journey through the close readings of images, from pioneers such as William Henry Fox Talbot or Hippolyte Bayard, early women photographers such as Julia Margaret Cameron and Augusta Mostyn, through to the feminist photographic performance art of Austrian VALIE EXPORT HonFRPS, who poses as the Madonna

cradling a vacuum cleaner in her 1976 image, ‘Expectation’.

Along the way we discover photographers from West Africa to South Asia, through monochrome studio portraiture by Cameroonian Michel Kameni and handcoloured gelatin silver prints by Indian Ram Chand, as well as images by Diane Arbus, Lee Friedlander and others.

An accompanying exhibition of the same name and curated by Prodger is at The Photographers’ Gallery until 19 February 2023. Rachel Segal Hamilton

Above ‘Expectation (Erwartung)’ by VALIE EXPORT HonFRPS

Left

‘Miles Davis’ by Lee Friedlander

Loose Joints (£49)

From Infra (2011) to Incoming (2017), Irish artist Richard Mosse HonFRPS has always enlisted unusual photographic technology in his efforts to explore the big questions of our age, including conflict and migration. His latest body of work focuses on the ecological devastation of the Amazon rainforest using multiple techniques including microscopy and multispectral imaging.

Rhiannon Adam

Blow Up Press (£95)

Pitcairn Island in the Pacific Ocean is a tiny British Overseas Territory renowned as the site of a mutiny that took place aboard the HMS Bounty in 1789. More recently, in 2004, the island was rocked by claims of sexual abuse. Rhiannon Adam’s haunting artist’s book is the result of a strange and alienating three months spent among a community still wary of outsiders.

Damian Hughes

Palgrave Macmillan (£109.99)

Ecology emerged from botany, the study of how plants thrive as communities. From day one it was bound up with visual culture. In this enlightening book, scholar Damian Hughes reveals the role played by photography in the development of an approach to understanding the world that is ever more relevant, as we confront global warming and biodiversity loss on an unprecedented scale.

A HIS'li PHO'Ji

When Simon Roberts HonFRPS arrived in Havana for the first time in 2019 he was struck by how much it conformed to the visual stereotypes familiar to outsiders.“It seemed almost as if the city had become a stageset for us foreign visitors,” he says.

Roberts was there as part of a collaboration between the Universidad de las Artes in Havana and the Royal Academy of Fine Arts Antwerp, uniting four Cuban and four European photographers to make new work about contemporary Cuban society.

On his second day there, Roberts wandered into the Church of Santa Rita de Casia. “I was immediately taken by its beautifully preserved neocolonial features and great parabolic arches holding up a carved wooden roof,” he remembers.

“On further investigation I realised there were dozens of churches, cathedrals and other faith buildings dotted around the city representing all major religions – surprising given that Castro had enshrined atheism into the country’s constitution.

“I was drawn to the huge range of architectural forms, from the splendour of Havana’s Catholic cathedral through to the vibrant, makeshift spiritual spaces in corners, basements and appropriated buildings,” says Roberts.

And the most surprising location? “El Calvario Baptist Church, housed in Havana’s former circus building.”

Cathedrals Are Built In The Future by Simon Roberts HonFRPS is published by Another Place Press. anotherplacepress.bigcartel.com

1 Tell us about an image that inspires you

A photograph from the Through Our Lens: Growing up with Covid-19 exhibition by Amy Lorrimer, then aged 16, taken during the first lockdown, a time of uncertainty and fear. Full of hope, it captures youthful joy, is testament to resilience and a reminder that things get better.

2 Which achievement makes you most proud?

I love that Impressions is a community. Without people, a gallery is just a room. Syd Shelton’s Rock Against Racism show opened on the day Jo Cox MP was murdered in nearby Batley. There was a deep feeling of disbelief and sadness and I thought about cancelling. Three constituents of Jo’s came, having decided to attend because they knew Impressions was a safe place where they wouldn’t feel alone.

3

What has been the toughest time in your career?

Saving Impressions Gallery from the threat of possible closure, and ensuring its future by closing the gallery in its York location in 2005 and reopening in a

purpose-built gallery in Bradford in 2007. Looking back, it was a bold, risky decision. At the time someone big told me, “You are committing professional suicide.” It’s the best professional decision I’ve ever made.

4

What would you most like to be working on right now?

The programme of exhibitions and the public art bringing photography to the streets of Bradford for 2025, when Bradford will be the UK City of Culture.

5

What’s next for photography?

The growing interest in environmentally aware approaches by, for example, Hannah Fletcher from the Sustainable Darkroom, Melanie King, Christina McBride and, closer to home, Lisa Holmes, who runs an eco darkroom in Keighley. Lisa and I plan to host an inaugural sustainable photography networking event at Impressions in spring next year.

impressions-gallery.com

From the series Speak the Wind by Hoda Afshar

From the series Speak the Wind by Hoda Afshar

SOPHIE GORDON

“Putting the viewer in The Queen’s place is often an uncomfortable experience as hundreds of eyes stare back at us”

594

NADINE IJEWERE

“I’m just going to take photographs of people who look like me and question why there’s only one type of beauty”

606

MING SMITH

“Mainly I think that the doing of photography can be a healing instrument for yourself”

616

DESTINY DEACON

“The photos of the dolls are saying we’re still treated like children; we’re still trying to express ourselves”

BABAK TAFRESHI

“I’m a nightscape photographer, here to reveal the beauty of the night sky of this place”

632

JOHN AKOMFRAH

“Migration is the most utopian act on the planet because if you don’t believe there’s a future you don’t move”

640

CARLY CLARKE

“There’s a picture of me looking out of the window in my mum’s bedroom. It reminds me of my darkest hour”

LAIA ABRIL

“I never romanticised photography as the only way to tell stories and I think that was helpful”

Following the death of Queen Elizabeth II, Patron of the RPS from 1952-2019, art historian Sophie Gordon looks back at her evolving royal image

Top left Princess Elizabeth with The Countess of Strathmore, 1927, by Frederick Thurston/ Royal Collection Trust/ His Majesty King Charles III 2022

Bottom left Queen Elizabeth II, for Golden Jubilee 2002 portfolio, 6 December 2001, by Rankin HonFRPS

Above The Queen on tour in Cheshire, UK, 1968, by Eve Arnold HonFRPS/ Magnum Photos

Top right The Queen laughing on board HMY Britannia, 1972, by Patrick Lichfield HonFRPS/Getty Images

Bottom right Queen Elizabeth II, 1952, by Dorothy Wilding/Royal Collection Trust/His Majesty King Charles III 2022

When I arrived at Windsor Castle in October 2005 to begin work as the new curator of photographs, I was immediately asked to work on an exhibition of portraits of The Queen to celebrate her 80th birthday in April 2006. This project opened up a side of the collection that had, surprisingly, been seen only rarely over the previous decades.

Even more of a surprise, at least to my more experienced colleagues who knew ‘how things were done’, was that The Queen decided she wanted to see the exhibition before it went on public display. So only a few months into the job, I found myself escorting The Queen and The Duke of Edinburgh around a display of portraits of themselves. It was a truly extraordinary and somewhat surreal experience.

What had previously only been an intellectual exercise suddenly became a very real, emotional journey through a family’s history. The best part, though, was listening to what they said.

Almost the first photograph we stopped at was a work by Frederick Thurston, purporting to show the infant Princess Elizabeth with her grandmother in 1927. “That’s not me, it’s Margaret,” said The Queen. I was completely thrown and had no idea about the protocol of arguing with The Queen over whether she recognised herself or not. A senior colleague moved things along swiftly, while we whispered furiously to each other.

The next portrait we stopped at fortunately received only positive remarks. Cecil Beaton photographed Princess Elizabeth in 1942

to mark both her 16th birthday and her first official public engagement – inspecting the Grenadier Guards as their newlyappointed colonel-in-chief. The princess wears a military-influenced outfit with a brooch showing the Guards’ insignia.

For an official portrait taken during the war, the subject is presented in a strikingly relaxed manner. This in turn highlights the individuality and youth of the sitter, something that is often lost in a more traditional or formal approach. The photograph really raises several important questions for when photographers approach The Queen – should the photograph draw on the tradition of royal portraiture? Should the sitter represent a timeless, institutional role, or is she an individual?

Perhaps the most successful photographs of The Queen manage to combine all of these elements somehow. Beaton’s early images of the princesses and their mother rely on dramatic surroundings and theatrical lighting to imply status and role, yet the day dresses and positioning of the women shows them as mother and daughters.

In contrast to Beaton’s busy background, Dorothy Wilding chose to photograph The Queen in front of a stark white backdrop, with the sitter staring directly at the camera. The modernity of the 1947 engagement portrait is remarkable and, although it is rarely seen, it remains a hugely successful statement of the partnership between The Queen and The Duke, as he stands resolutely behind her, arms crossed. When viewing the 80th birthday exhibition, The Queen and The Duke stood for some time in front of this portrait

“I had no idea about the protocol of arguing with The Queen over whether she recognised herself or not”

facing themselves from 59 years earlier. “Do you remember this?”, The Queen asked The Duke. He turned, smiled and said, “Oh yes”.

It was a very touching moment.

Wilding went on to photograph The Queen again on several occasions: twice in 1952 and in 1956. She again used the minimal background and uncomplicated approach, and created the most famous and most reproduced images of The Queen. Her portraits became the images sent around the world to embassies, official buildings and military bases, and they were used for stamps, postcards and a wide selection of ephemeral souvenir items.

Beaton was asked to take the official coronation portraits in 1953. His approach was traditional, using a painted backdrop of Westminster Abbey, alongside the symbols of state. A similar style was adopted for an extensive series of portraits in 1955, although Beaton’s use of lighting and contrast was moving away from a softer approach. By 1968, Beaton had dispensed with a backdrop completely and presented The Queen in the Admiral’s Boat Cloak against a stark white background. No royal trappings are visible. Beaton himself famously stated he wanted to "try something different". It is his most striking portrait of The Queen, undoubtedly modern yet also recalling the direct approach of Wilding.

During the 1960s and 1970s, photographers sought out less formal, more natural portraits of the royal family. The aim to capture the individual partly arose from the public demand to gain

greater access to the royals through images and film. One way to manage this was to use photographers known to the family. In 1971 Patrick Lichfield, a cousin of The Queen, was invited to photograph the Royal Family on an official tour and then later at Balmoral to create images to mark the Silver Wedding Anniversary in November 1972. The results are well known, showing the family relaxed and happy. Most famous perhaps is the portrait of The Queen on board HMY Britannia, laughing at the photographer as he is ducked in the swimming pool (with his waterproof camera!).

Lichfield was also asked to participate as one of several photographers to create The Golden Jubilee portfolio in 2002. Ten UK and Commonwealth photographers were given short sittings with The Queen and the resulting portraits highlight the differing approaches seen at this time. For example, Rankin created two portraits of The Queen, closely framing her brightly lit face and looking up slightly. The portrait in the Royal Collection has the Ballroom at Buckingham Palace as the background, but the more widely known portrait has the Union Flag behind Her Majesty. The close focus on the face is unusual and somewhat uncomfortable, while ostensibly the portrait manages to be also appropriately patriotic.

Lichfield chose to create a formal double portrait of The Queen and The Duke in profile, facing right, recalling Yousuf Karsh’s striking double profile portrait from 1951, where the couple face left. Lichfield’s differing approaches perhaps depend on the personal

“‘Do you remember this?’, The Queen asked The Duke. He turned, smiled and said, ‘Oh yes’. It was a very touching moment”

Above

‘The Queen visiting the Drapers’ Livery Hall, London, 2014’, by Martin Parr HonFRPS/ Magnum Photos

Below ‘Felicity: Platinum Queen, 2022’ by Rob Munday

nature of the wedding anniversary in contrast to the formal state occasion of a jubilee.

Photojournalists have presented a different image of The Queen, frequently seeking out differing viewpoints. Eve Arnold and Ian Berry have looked at the world from The Queen’s perspective, as well as showing us The Queen taking her own photographs and film. Putting the viewer in The Queen’s place is often an uncomfortable experience as hundreds of eyes stare back at us. It is also sometimes comical, as unique personalities stick out in the crowd. The Queen remains clearly distinguishable, both by her colour blocking outfits and the ever-present ring of empty space that separates her from the public like an aura. Martin Parr relies on the bright pastel blue of The Queen’s hat and dress for her to be identifiable.

The photographs that we have seen The Queen take currently remain private. Many of them have been compiled into albums prepared by the Royal Bindery at Windsor Castle. They will hopefully, in time, shed new light on the reign and the family of The Queen from her own perspective, as some of the recently released film footage has done.

More recently, increased formality seems to have returned to official portraits. John Swannell’s Diamond Jubilee portrait from 2012 was taken inside Buckingham Palace, with the Queen Victoria memorial visible beyond, highlighting the only other

British monarch to have reached the milestone. The Queen is dressed in recognisable jewels, including the Diamond Diadem as well as other royal insignia.

Similarly successful at catching The Queen in an informal moment within a formal setting are some of the portraits which have emerged from the 2003-2004 commission from the Jersey Heritage Trust. Rob Munday and Chris Levine worked together to create a holographic portrait of The Queen, and many of the photographs from the session have subsequently emerged as portraits in their own right.

One recent discovery was the portrait known as ‘Felicity’, which Munday issued for the Platinum Jubilee in 2022. The portrait captures the brief moment when The Queen relaxed and smiled at her dresser Angela Kelly, who had just entered the room. The portrait perhaps demonstrates the famous sense of humour and the twinkle in the eye, of which many have spoken in recent times. Munday’s portrait was widely used following the death of The Queen. It was even projected by the BBC onto the outside of Broadcasting House in London.

And in case you’re still wondering about that Thurston portrait in the exhibition? It remained on display.

Sophie Gordon is an art historian and former head of photographs at the Royal Collection (UK)

“The Queen remains clearly distinguishable, both by her colour blocking outfits and the ever-present ring of empty space that separates her from the public like an aura”

Below

Still from Mimesis: African Soldier (2018) by John Akomfrah

Right

‘Tina Turner, What’s Love Got To Do With It’, 1984, by Ming Smith HonFRPS

Congratulations to this year’s recipients, from scientists to publishers, academics to artists

For scientific or technological advancement of photography Graham Hudson and Leonardo Chiariglione

For a sustained, significant contribution to the art of photography Destiny Deacon

Awarded to distinguished individuals who have an intimate connection with the science or fine art – or application – of photography

Laia Abril, Ming Smith, Dafna Talmor, Victor Burgin, Dawoud Bey, Ajamu X, Craig Easton, Jo Ractliffe

For sustained, outstanding and influential advancement of photography Howard Greenberg

For outstanding achievement in the production, direction or development of film for cinema, television, online or new media Werner Herzog

For major achievement in the field of cinematography, video or animation

Dr John Akomfrah CBE RA

For excellence in the field of

Clockwise from top left From the series Speak the Wind, 2015-2020, by Hoda Afshar; from a successful Fellowship Documentary submission by Mark Phillips FRPS; ‘An astronomer’s night’, Canary Islands, 2015, by Babak Tafreshi; ‘Smile’, 2017, by Destiny Deacon HonFRPS

photographic curatorship, through exhibitions and associated events and publications

Anne McNeill

For outstanding achievement and excellence in these fields

Nadine Ijewere

For outstanding achievement or sustained contribution in photographic education Andrew Dewdney

For a body of work promoting or raising awareness of current issues

Hoda Afshar

For major achievement in photographic criticism or photographic history

Professor Emeritus Liz Wells

For major achievement in the field of photographic publishing in its broadest sense Craig Atkinson

For a body of scientific imaging which promotes public knowledge and understanding

Babak Tafreshi

SELWYN AWARD

Recognising successful science-based imaging work

made by a researcher in the early stage of their career Edward Fry

For achievement in the art of photography for those aged 35 or under Carly Clarke

For extraordinary, sustained support of the RPS Mark Phillips FRPS

For outstanding contributions t o the work of the RPS Richard Brown FRPS, Sue Brown FRPS, Robert Gates ARPS, Janet Haines ARPS

When, in 2018, she became the first Black woman to shoot a cover for Vogue in the magazine’s 125-year history, Nadine Ijewere posted her reaction on Instagram. “I am so grateful for this opportunity I have been given to shoot for a publication where I once felt perhaps I did not measure up,” she wrote.

Her words about the shoot with pop star Dua Lipa for the Future Talent issue of British Vogue are telling. While growing up in south London,

Ijewere had immersed herself in the fantasy world pedalled by her mother’s fashion magazines. None of the faces, hair or body types she saw on their pages resembled her own – or resonated with her Nigerian-Jamaican heritage.

It was only when she began taking pictures at sixth form college, using her friends as models, that she realised she could challenge the mainstream definition of beauty. She would go on to study photography at UAL London College of Fashion,

using social media as a platform for her considerable talent – and was soon being commissioned by brands including i-D, Dior and Hermes. Now, she is to receive the RPS Award for Editorial, Advertising and Fashion Photography.

In an extract from her first photobook, Our Own Selves, Ijewere describes her fascination with ballgowns, her first trip to Jamaica, and how she swapped the road to medical school for a trailblazing journey into photography.

I went to study in sixth form and that was when I first started to dabble in photography. I was actually going to study medicine. My parents thought I should do something more academic. Well, it was more my dad – my mum was always like, “Do what you want to do.”

They had a darkroom so we could process the film ourselves. I just got this incredible rush of excitement of shooting a roll of film and not seeing it until you’d

processed it yourself, and being so excited to see the images come up on the negative. I loved the patience of really thinking about the image you were going to take and the limit on how many frames you have on a film roll.

I’d always loved looking through fashion magazines. My mum’s very into that. I think at that point, when I started exploring photography in the magazines I’d flick through, I would think to myself, “Well...” I never saw anyone that really looked like my friends or anyone I could

relate to in those images. If they were people of colour or Black women, they were all light-skinned and had European features. If they had curly hair, it was blow-dried straight to match the white women. None of my friends really looked like that.

When I was learning photography, we’d explore different techniques. We’d do still life, we’d do portraits, we’d do landscapes. I was drawn to photographing people the most, so I started shooting my friends.

We’d get suitcases full of clothes from our wardrobes and we’d drag them to the park, and we’d just take pictures and have fun. I became the designated photographer and I quickly realised I didn’t want to study medicine. I had to redo a year to be able to do art so I could study photography [at UAL London College of Fashion], but I never ever saw the possibility of photography as a career.

In the third year you got to explore as part of your dissertation. That was my point of thinking, “I’m just going to take photographs of people who look like me and

question why there’s only one type of beauty.”

From a young age I have always loved beautiful gowns and dresses, and dressing up to go to the ball and parties.

I have a nostalgia for the 1950s and 1960s with the hair and the clothes. Me wishing I could dress in this way every day, ha ha! But growing up and looking at fashion imagery, I rarely saw Black women portrayed in these worlds and in this way, but it did exist, and throughout history as well – those images are so rare and were (back then) difficult to research and find.

I think that this is another element to my work. I love doing those beautiful stories and showing Black women in this way. I want to break these stereotypes of only certain types of women being able to exist in these worlds, if you like, but I guess I then make the images contemporary with the compositions.

This project for me was an important journey. I hadn’t really explored my Jamaican side until my late twenties. I suppose, as one gets older, you want to connect with your background some

more and so this felt like the time that I could do this.

Growing up, through the media I guess I would always come across negative connotations regarding Jamaican women and I wanted to go against that because it isn’t true, especially with the women I grew up around.

That trip was my first time in Jamaica and I collaborated with hairstylist Jawara Wauchope. I remember the first shoot we did together, he asked me if I was Jamaican and I thought that intriguing. He said there were some mannerisms I had that prompted him

to ask. So interesting when I had grown up in London. Anyway, we both wanted to work on a project that celebrated strong Jamaican women and the relationship with hair.

Hair is a huge topic within the Black community, so we are celebrating what is another type of beauty. It was honestly such a personal journey going there that I felt I had a connection which, I think, being in London I didn’t have.

There is a moment that sticks out to me where one woman we were photographing – her name was Janet – asked us after we had explained the

project where the images would go. She said she hoped they wouldn’t end up somewhere where there will be captions referring to us as “gorillas and loud angry women”. At that point I realised why projects like this are so important to do. Honestly, I’m so glad I was able to do this project and have the privilege of doing projects like these. I think it’s so important in terms of educating others.

This is an edited extract from the monograph Our Own Selves by Nadine Ijewere with contributions from Lynette Nylander, published by Prestel, £39.99. nadineijewere.co.uk

Iran-born and Australia-based artist Hoda Afshar is intrigued by tension. The RPS Hood Medal recipient explains why

WORDS: CIARAN SNEDDON IMAGES: HODA AFSHAR/MILANI GALLERY, BRISBANE

Tension. A word that is by nature uncomfortable, even off-putting. But here it is in all its glory: the tension between the oppressed and their oppressors, between people and their surroundings, between individuals and societies at large.

Hoda Afshar, the recipient of the RPS Hood Medal 2022, is at home in the tension. Not content merely with capturing beautiful photography infused in conflict, she finds satisfaction in exploiting the natural tensions between different forms of image-making.

This all leads back to the photographer’s first foray into the world of visual art. She was born in Tehran in 1983, with her childhood unfolding in the country’s immediate post-Islamic Revolution years. Her own life appeared to be at odds with the public image of this Iran, and it is here that her interest in photography began.

Afshar’s university days were at the University of Tehran where she studied fine art, with a particular focus on photography. By 2005 she was working as a full-time photographer. During this period she created a piece of work titled Scene which, while grainy and moody, offers a message with obvious clarity –Iran is not a monoculture.

Here are the underground parties that were held across Tehran: dancers, cigarettes in hand, embracing one another. The images walk a tightrope between documentary photography and visual art. Deliberately so, says Afshar. “I’ve always approached

photography as a visual art form, making works that combine documentary and non-documentary elements, and at the same time questioning the supposed line between these different modes,” she explains.

“I came to the view quite early in my career that the documentary photographer is no less than an artist, always in some way involved in framing and staging reality, and this led me to explore how such tensions inherent in the medium of photography might be used creatively. It is here I think that photographers and artists can learn from each other.”

And so it is that the tension creeps into her work.

Scene was never publicly displayed in Iran, nor shared on any platform. It couldn’t be. By 2007, the year after her graduation, Afshar was living in Australia. While the setting might have changed, the desire to portray people and places imbued with an emotional resonance did not. In a portfolio more than 15 years in the making – and with an impressively eclectic and varied aesthetic – the main throughline is that of portraying the unportrayed, the unseen, just like the secret parties of Tehran.

“In most of my works I have mainly been concerned with exploring issues to do with visibility and representation of the lives and experiences of marginalised groups within society,” Afshar says, adding: “Or bringing to light concerns that have been hidden from the public view.

“I came to the view quite early in my career that the documentary photographer is no less than an artist, always involved in framing and staging reality”

Below

Boochani –Manus Island’ from the series Remain, 2018

“[I am drawn to] complex human stories, where struggle and triumph, suffering and resistance, beauty and ugliness coexist, in no hierarchy of order. I am also mostly only motivated to make work about subjects that I am emotionally drawn towards, and more often than not this tends to involve making work about specific groups engaged in social and political struggles. So I suppose I am motivated and guided by a compassionate approach. In my most recent work, Speak the Wind, I have been concerned with another aspect of the issue of visibility, namely, with the problem of how to capture certain realities that cannot be directly seen or recorded.”

Speak the Wind is a profile of a belief, held by the inhabitants on the islands of the Strait of Hormuz, off Iran’s southern coast, that winds can possess a person and make them ill. It’s a fascinating study of a little-known culture, and of the winds themselves. Afshar has previously written: “This project documents the history of these winds and the visible traces they have left on these islands and their inhabitants –a visible record of the invisible seen through the eye of the imagination.”

Part-landscape, part-portrait, partvisual art, as a standalone collection Speak the Wind could be the work of several photographers.

Another landmark in Afshar’s career is her series Remain, formed of a video and portraits, each documenting life on Australia’s infamous Manus Island detention centre. The pieces are a collaboration between Afshar and Kurdish-Iranian writer and journalist Behrouz Boochani, who was being held there at the time.

“Behrouz and I exchanged thousands of voice messages over many months on WhatsApp before I went to Manus,” Afshar explains. “We discussed the philosophy of the camps and what was happening there and mapped out a secret plan to get me to the island without alerting the authorities. It was a risky and dangerous trip.”

“The process of making the images was quite theatrical,” she adds. “I staged each portrait to symbolise the physical and psychological struggles of being a refugee. This was to avoid simplifying or idealising their narrative. Before taking their portraits, they’d shared with me the most painful stories of their life and time on Manus.

“We discussed the philosophy of the camps and mapped out a secret plan to get me to the island without alerting the authorities. It was a risky and dangerous trip”

“Then I would ask them to choose a natural element like water, or fire or birds – something that they felt would reflect their inner feelings most.

“Behrouz picked fire and we made his portrait on the last day, with many of the locals and the refugees involved in creating it — two men holding the backdrop, a couple making fire, one was holding the reflector and the other was making smoke. Looking at Behrouz’s portrait now, I see everything that went behind making it, and even what came after that. It’s all there in his gaze.”

First displayed in 2018 at the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, the piece was one of several made by Behrouz Boochani while on Manus. He has been living in New Zealand since November 2019, having first been detained in July 2013.

To single out any of Afshar’s work is to exclude, or sideline, the collective variety of her catalogue. What of Under Western Eyes, a Warholian take on Islamic identity? Or In the Exodus, I Love You More – a love letter, at least at times, to Iran and a document of Afshar’s separation from her homeland. Agonistes is another important entry in her oeuvre, with its depiction of the stifling culture of anti-whistleblowing measures in Australia.

“It is a decision,” Afshar says, of the wide-ranging nature of her work, “but only in the sense that I don’t believe in using a uniform approach or visual language for everything I make a work about. I’d rather allow the nature of the subject to determine the aesthetic and form of the project

instead. A lot of the decisions are made in the process of making, through the dialogues I have with the people I work with. Each project demands a language of its own.

“I don’t have a bucket list. I tend to focus entirely on the project that I am working on at any given time, and I never know what will be next. Each project I undertake emerges out of my encounters with the world and with people.”

What, then, lies ahead? Predictably unpredictable, it is an archive of images at the Musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac, in Paris.

“It’s the photographic archive of the French psychiatrist and photographer, Gaëtan Gatian de Clérambault, who made more than 30,000 images of Islamic women in veils to explore his psychoanalytical ideas about covering and fantasy,” Afshar explains.

“I’m exploring how the medium of photography became and continues to serve as one of the central tools in the project of colonialism through its construction of fantasised representations of Islamic women, viewed at once as threatening and as desirable.”

The RPS Hood Medal is awarded in recognition of a body of photographic work which promotes or raises awareness of an aspect of public benefit or service. Fitting, then, that Afshar should continue to be such a pioneer of enriching and beneficial work, all done with such creativity and imagination.

hodaafshar.com

“I don’t have a bucket list. I tend to focus entirely on the project I am working on at any given time, and I never know what will be next”

New York-based photographer Ming Smith came to prominence in the mid-1970s and has only recently begun to be celebrated again. As she is awarded an RPS Honorary Fellowship she selects some of the images that mean the most to her

Previous page

West Indian parade, Brooklyn, New York, 1972

“This is an early photograph. I was interested in the dancing and the culture of the parade. We didn’t have anything like this in Columbus, Ohio. It was just an image I took – I liked the girl in the car. I don’t know who she is. It’s just street photography. My work was included in the exhibition We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965–85 at the Brooklyn Museum, and curator Rujeko Hockley chose to have this photograph behind her when she spoke. I loved seeing it large.”

Below When you see me comin’ raise your window high, New York City, New York, 1972

“This photograph belongs to an early body of work I made in Harlem, New York. The mother is leaning out of a window and looking at a man below who I took to be her son in what I saw was a protective way. That’s how mothers in New York are – we worry about our children. We say, ‘Be careful’, to the daughters as well.”

When Ming Smith and her siblings were going through their mother’s belongings after she passed away, they discovered a yellow Kodak box with Smith’s name on it. “My brother handed it to me,” the artist recalls during a video call from her studio in New York. “‘I guess this is yours,’ he said.”

The box contained photographs Smith had taken on a school outing when she was around eight years old.

“I didn’t even remember,” she says. “When my mother was alive she would say, ‘What are you doing with your life? You’re still photographing?’ But when I opened the box and saw some of my belongings and photos, even some of the first photos I took when I was in college, it was amazing. She is gone, but sometimes I think she speaks to me more now than when she was alive.”

For Smith, who is receiving renewed attention and recognition in the art world, media and beyond, the acclaim is bittersweet. “I feel grateful, but I wish it had happened while my parents were alive. I’ve always had internal questions about what I’m doing, but I kept on photographing, and photographing helped me to continue. It’s been that way my entire life.”

Born in Detroit, Michigan, and raised in Columbus, Ohio, Smith had intended to go to medical school, but after studying microbiology and chemistry at Howard University decided it wasn’t for her. Instead, she moved to New York in the early 1970s.

Self portrait (total), 1986

“I like this image because that’s who I was – a mother and a photographer. And those were the two main loves of my life – I loved photography and raising my son, Mingus. It was a glorious moment. I felt very balanced. Many times, we go through life trying to keep our balance, trying to juggle things, and that was a very serene [time]. It is what women do – they work, they raise their children, and I come from that tradition. It’s a successful image for me.”

“When I told my father I wasn’t going to go to med school, he said, ‘Well, you could always be an artist,’” Smith recalls. Her father was a pharmacist, but he also took pictures. “I didn’t say yes straight away but it stuck with me. I didn’t want to claim it until I knew I could do something in it, or until I found it for myself. I didn’t tell anybody, but when I came to New York, that’s when I decided to be an artist.”

Working as a model to get by, Smith attended ‘go-sees’ –shoots with photographers who were building their portfolio. One occasion would leave a lasting impression.

“There was a partition in this loft space and I could hear two photographers debating whether photography was just nostalgia or if it really was an art form,” Smith remembers. “The studio had models and photographers coming in and out, and I started taking photos and hanging out.” Before long, Smith was invited by photographer Louis Draper to join the Kamoinge Workshop, a collective of Black photographers founded in 1963. She was the first woman to join the group. “Ever since then, photography was my chosen art form.”

“There was a hairdressers in Manhattan on 57th Street called Cinandre. Andre, who ran it, did most of the models’ hair back then, including Grace Jones, who became a friend. He cut her famous flat top. Grace was telling me how she was going to go to Paris because she wasn’t getting any work and we were complaining about how black girls get the leftover jobs. This was before she went. She came back a star. I like this because it’s Grace Jones before.”

Above and below Sun Ra space I & II, New York City, New York, 1978

“I had a friend who was auditioning for the Sun Ra band. She called me up and asked if I wanted to come with her. I was being supportive of a friend and took my camera. This is a very successful image for me. It’s pure energy, cosmic energy. It’s just light and it was, well, Sun Ra, the visionary keyboardist, composer, arranger, bandleader and poet. I like these images [as a pair] because they go together for me. I don’t like to see them separated. It’s easier to understand when you see them side by side. Designer Karl Lagerfeld said this [above] was one of his favourite images.”

Joining Kamoinge was transformative for Smith and her photography. She acquired and developed key skills and ideas that would inform her work for decades to come.

“I learned what the art of photography was about,” she recalls. “I learned about Roy DeCarava and Brassaï and Bresson. It was like opening a door. I was immersed in it.” Black and white arthouse films provided inspiration too. “I loved a lot of the directors and their work,” Smith enthuses. “It was like still images to me. I learned a lot about photography and light by looking at some of those films. I love Fellini and the characters. I still have a magical, offbeat love for his images and the feelings of those images.”

“The Greyhound bus was how people migrated from the south to the north. Even me. I travelled with my grandmother on a Greyhound bus to Columbus, Ohio, where I was raised. I was around four years old. We almost missed our stop because we had fallen asleep. I left my doll. This image is from a series dedicated to the American playwright August Wilson called August Moon. I took the bus to the Hill district of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, to photograph his hometown. The woman reminded me of my grandmother. The children had dolls with them.”

Smith’s photographs, with their focus on the humanity and spirituality of African Americans and Black culture, possess a kind of undefinable yet undeniable energy. They feel urgent and visceral, not of this world. Often playing with what’s seen and not seen, Smith uses light and shadow, movement and blur to conjure images that not only draw in the viewer but keep them there.

“It’s my instincts and what I see,” she says. “I was following my impulses, very much like how a jazz musician [plays] –they riff and improvise.

She adds, “This is all hindsight for me. While I was doing it, I wasn’t thinking that. It’s seeing something and capturing that moment – that was my intention. And that was art for me.”

Ming Smith was initially recognised when she became the first woman invited to join the Black photography collective the Kamoinge Workshop. Focusing on street photography and portraits of Black cultural figures, Smith was also the first Black woman photographer to be included in the collections of the Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan. Her work and influence have been celebrated again in more recent years.

Below Professor Edward Boatner, New York City, NY, 1979 “African American composer, teacher, choral conductor and singer Edward Boatner taught piano and gave voice lessons. He also arranged and published many spirituals. One of his sons was Edward ‘Sonny’ Stitt, the famous jazz musician. He knew Billie Holiday. I was fascinated by that. Those are his students, hanging on the wall behind. Some were on Broadway, others were recording artists. He was a proud and elegant man who had a lot of integrity and a lot of love for his students.”

Anything could draw her eye, she says. “Sometimes it was in my family or going to the grocery store or coming out of a shopping centre. It could be anywhere. I had my camera with me most of the time.”

In 1978, MoMA bought some of Smith’s work and she became the first African American female photographer to have work acquired by the museum. In the decades that followed Smith kept making pictures, but attention fell away. In 2017 she was included in the group exhibition Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power at Tate Modern, London. More shows followed. She is busy preparing for two right now, including a solo show at the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston, opening in spring 2023.

“I like when people come and see my photographs,” Smith muses. “Many of the young people are very inspired by it, which is fantastic.

“Mainly I think that the doing of photography can be a healing instrument for yourself. It helped me get through the ups and downs in life. You can take your camera any time and be alone and work, and so the doing of it is healing because it brings you into yourself. You can be authentic.

“My life has always, it seems, to have been led by spirits. Nothing was planned, I just follow my angels or my spirit. Seeing my work – I’m happy, I’m glad, but doing it was most satisfying.”

mingsmithstudio.com

“I took this in Germany. I was on a bus with my former husband, Mingus’s father, the jazz musician David Murray, and a band. We’d been travelling for maybe ten hours when I saw these sunflowers. It was so beautiful, I thought, ‘Of course Van Gogh would paint sunflowers!’ I said, ‘I’m sorry, I’m sorry, you must stop the bus, just for two minutes.’ I love this photograph not only because of the sunflowers, but the dark, heavy clouds, which seemed very meaningful.”

She disarms her audience with humour while confronting them with unsettling symbols of everyday racism. As Destiny Deacon receives the RPS Centenary Medal she explains how her activist mother inspired her life and work

WORDS: EVA CLIFFORD IMAGES: DESTINY DEACON HonFRPS

A menacing grin looms overhead, eyes and teeth glistening demonically. A decapitated doll lies sprawled beside an axe. Two dolls sit side by side, one with a gaping hole in its head. The photographs of Destiny Deacon could well be stills from a horror film but for her, as an Indigenous Australian, horror is a part of everyday life.

Deacon, who is being awarded the RPS Centenary Medal in recognition of her contribution to the art of photography, was born in 1957 in Queensland and raised in Melbourne. Her ancestry hails from the KuKu of Far North Queensland and the Erub/Mer people of the Torres Strait. She grew up in Housing Commission – the equivalent of British council housing – in the innercity suburbs, part of a culturally diverse, working class community which exposed her early on to the country’s deep-rooted inequalities.

Raised by her mother, an influential activist, Deacon remembers tagging along to meetings and protests campaigning for Aboriginal rights, and it was her mother who inspired Deacon to study politics at university. She then moved on to teaching, working at some of Australia’s roughest schools before becoming a staff trainer for the Aboriginal activist Charles Perkins. It was in her 30s that she turned to photography, after taking part in a group exhibition at the Melbourne Fringe Festival in 1991.

Deacon was in fact returning to an early interest as she recalls making photos on a Kodak point-and-shoot as a young girl. Even then her photos had a theatrical slant, often featuring her family members, such as her little brother dressed up in their mother’s clothes. Though she’d never considered photography as a profession, Deacon

recognised its potential to articulate her political beliefs, and it was after her first show that things began to snowball.

Since then, her work has made extraordinary waves. Besides participating in prestigious exhibitions around the world including documenta, the Yokohama Triennale, the 1st Johannesburg Biennale, the Havana Biennale and the Asia-Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art, Deacon has earned a reputation as one of Australia’s boldest and most acclaimed contemporary artists. Yet for all her achievements she remains strikingly humble, referring to herself as “just an old-fashioned political artist”.

To describe Deacon’s work in words is difficult because it affects the viewer on a visceral level. Looking at her image of

“For all her achievements she remains strikingly humble, referring to herself as ‘just an old-fashioned political artist’”

‘Meloncholy’, 2000, from the series Sad and Bad

a decapitated doll beside a hatchet in ‘Axed’ (1994-2000), for instance, has a far stronger impact than reading about it. Central to all her work though – whether she’s working with photography, video, performance or installation – is the political message at its core. Deacon consistently exposes the everyday racism that pervades modern-day Australia and the violence that has been inflicted upon Aboriginal people for generations. Even her method of image making is inherently political. Her ‘anti-art’ aesthetic cunningly subverts the conventions of fine art photography, historically the preserve of white middle class men.

Drawn to the simplicity of Polaroids, Deacon began making portraits of her Aboriginal friends and family in the 1980s, but despite its convenience Polaroid was extremely costly – every shutter click costing around two Australian dollars. One thing it taught her, though, was how to be economical taking photos and soon Deacon began working with more reliable and patient models – dolls – which have since become her trademark. She explains: “With the Polaroids, I tried to take them with friends and family but people say ‘hurry up’ and they have somewhere to go. Dolls didn’t complain, of course.”

After capturing the images on Polaroid, Deacon would then blow them up to present on gallery walls, characteristically blurred and out of focus. “When I first started, people thought it wasn’t art,” she says. “White men thought it wasn’t photography because it was pictures of dolls and things – and also because it was bloody Polaroids.”

While Deacon swapped film for digital when Polaroid stopped production in the early 2000s, her anti-art aesthetics endured – as did her particular brand of dark humour, which reminds us ‘serious’ art can be funny too. Through her ‘lo-fi’ setups Deacon, who says she’s never owned a fancy camera in her life, uses humour as a disarming tactic and her

wit as a weapon to challenge common cliches about Indigenous people. “If you’re going to send a message,” she says, “you should make people think and laugh as well. I like to say there’s a laugh and a tear in every picture.”

With the dolls, mainly ‘rescued’ from secondhand stores, Deacon is able to act out certain feelings or experiences particular to being an Indigenous Australian. To her they represent the objectification of Indigenous people, so in reclaiming these objects – among other “Koori kitsch” or “Aboriginalia” she has collected over the years, from boomerangs to golliwogs – Deacon gives them agency.

“We [as First Nations] don’t have sovereignty, and so the photos of the dolls are saying we’re still treated like children; we’re still trying to express ourselves and say something,” she says.

By staging the dolls in strange and sometimes sinister scenarios, Deacon draws attention to Australia’s dark colonial legacy. In ‘Adoption’ (1993/2000), eight miniature brownskinned dolls are shown lying face up in baking cups. What at first seems an innocent image takes on a darker meaning when we clock the reference to Australia’s Stolen Generations – a government programme lasting from the mid 1800s onwards, which separated Aboriginal and mixed-race children from

“If you’re going to send a message, you should make people think and laugh as well”‘Man and doll’, 2005

their parents and placed them in institutions. The trauma of separation is even more explicit in ‘Meloncholy’ (2000), in which a decapitated doll rests inside a scooped-out watermelon.

As shown by the frequent wordplay in her titles, subverting colonialist language is also a focus of Deacon’s work. She felt the cutting impact of words while growing up, when white kids would call her a “little Black C—”.

“For Aboriginals living around Melbourne, that’s all you’d hear,” she says. “‘You f—ing Black C. You f—ing Black C’. So what I thought I’d do is take the ‘c’ out of Black and it would make it sound stronger.”

Though a seemingly simple act, its impact was huge. “I was surprised, I started off in the early ’90s, and since then Indigenous Australians have used it right around Australia and just for ourselves – as our people. It’s amazing, I’m so pleased about that.”

Yet despite these positive gains – and the Indigenous communities continually fighting for recognition and justice around the world – little has changed for Indigenous people in Australian society, from Deacon’s perspective. In her 2017 work ‘Escape’, which shows two dolls suspended either side of a metal fence, she addresses the growing rates of Indigenous incarceration; the fact that if you are born Indigenous Australian you are far more likely to be imprisoned than a non-Indigenous Australian. For women, the risks are compounded: despite making up just 2% of Australia’s population, Aboriginal women total 34% of those incarcerated in women’s prisons – making them the fastest growing prison population in the country. More than 80% of those women are mothers, further fracturing families and creating long-lasting trauma which can be felt across generations.

As children’s playthings, Deacon’s dolls become symbols for how insidious racial discrimination is, affecting people right from childhood through subtle to not-so-subtle messages in the world around them. And just as dolls are a familiar trope in horror, Deacon subverts their innocence to reveal the darker aspects of society.

“Racial prejudice and stuff like that, it hurts. Especially for young children today,” she says. “It mucks their heads up, and that’s something we’ve got to deal with. That hasn’t changed. It doesn’t seem to have stopped since I was a little child. Being called a little Black C, that still happens to the little ones now.”

This injustice continues to fuel Deacon’s work as an artist and activist, and for as long as it continues she will carry on confronting these difficult truths. It is up to the viewer what they then do with that knowledge.

“The pictures tell the story,” says Deacon. “People look at the pictures and they should think, and they should either get love or get disturbed.”

“Racial prejudice and stuff like that, it hurts. Especially for young children today. it mucks their heads up”

Science photojournalist Babak Tafreshi is collaborating with image makers around the world to illuminate the night sky –and expose light pollution. As he receives the RPS Award for Scientific Imaging, he explains why

‘Las Vegas at Night’ shows the extent of the city’s light pollution

“I’m honoured to have been arrested by the police in almost every country I’ve been to,” says Babak Tafreshi with a playful smile. He’s exaggerating, but as a man who spends much of his time wandering around alone in the middle of the night, run-ins with the law are an occupational hazard.

“I’ve actually been arrested a few times. But most times the police just come to talk to me because they have suspicious eyes and wonder, ‘What is this guy doing out with unusual equipment at night time?’ As soon as you tell them, ‘I’m a nightscape photographer, here to reveal the beauty of the night sky of this place’,

there’s a hidden interest in every person, including police officers. That helps a lot in those situations.”

Tafreshi’s own interest in the night sky goes back to his childhood in Iran.

“I was curious about night skies ever since I can remember,” he says. “The changing point was when I was 13. I borrowed a telescope from my neighbour and set it on our apartment rooftop in the middle of Tehran to look at the moon. I couldn’t believe my eyes. Every crater and mountain was visible. I still remember that moment. It’s fascinating how a simple experience like that can change somebody’s life forever.”

That vision of the moon set Tafreshi on a lifetime of astro adventures, as an astronomer, science journalist, TV presenter, and now a science photographer and cinematographer for National Geographic. Many of his images incorporate landscapes or Earth-bound structures, so he prefers the term ‘nightscape photography’ to just ‘astrophotography’.

In 2007 he founded The World At Night (TWAN), a project with the slogan ‘One people one sky’ designed to show landmark buildings and natural locations around the world set against night skies. The project now has 40 photographers signed up. “I thought maybe if I photographed cultural landscapes and religious landscapes –

a church, a mosque, a Buddhist temple – and put them together under one roof, we can show one family living in one home,” Tafreshi explains. “We can break borders.”

Tafreshi is also an adviser on the board of Astronomers Without Borders, which has a similar goal of bringing people together through astronomy. Night skies are a great unifier, he suggests. Cultures across the globe and across time have looked up and wondered about humanity’s place in the universe. “There’s something inside you that all of a sudden unfolds,” he says. “It’s a connection to the universe that you were always looking for, understanding your place or your life in a different way.”

Now based in Boston, the IranianAmerican photojournalist doesn’t just aim to communicate the beauty of the universe, but also the science. He is this year’s recipient of the RPS Award for Scientific Imaging.

“In my photography, science is a major factor,” Tafreshi explains. “I have a science background. I studied physics.

I was a science journalist. In Iran, I had a TV programme on astronomy.

I was editor-in-chief of an astronomy magazine. My work usually tries to connect art and science in the media of photography and cinematography, or, for example, time-lapse motions.”

When creating images, Tafreshi often has a scientific phenomenon in mind

that he wants to demonstrate. “All my images start with the story,” he says. “We’re often saturated by the beauty of images we see on social media, but without the story, they don’t make an impact on people. I ask myself: What am I going to present? Is it a science story? Is it about the environmental impact of light pollution on a species? It could be a majestic new comet or an atmospheric phenomenon. I love to put as much science as possible in my visual storytelling.”

Tafreshi’s photography has taken him around the world, with the Atacama Desert in Chile and the Himalayas in Nepal his favourite locations for night skies. Spending around 90 nights of the

year working means he has witnessed all kinds of phenomena, his images often feeding into scientific understanding. “My photos are mainly wide angle. They won’t discover new objects but often they have something to contribute, especially in atmospheric science, by recording elusive phenomenon such as red sprite, or air glow phenomena, or a supernova.”

As human civilisations expand, so does light pollution, making it harder for people to find clear night skies. Tafreshi is currently working on a project

to highlight light pollution, including the impacts on insects, birds and other wildlife as well as on human health, mental health and cultures.

“Previous generations were in connection with night skies, for time, for a calendar, for healing and for moments of peace,” he says. “All of a sudden, it’s gone. It’s an important part of our environment to preserve, like a mountain or a national park.”

The work of astrophotographers or nightscape photographers is also becoming increasingly difficult due to

“I love to put as much science as possible in my visual storytelling”Clockwise from above: Constellation Orion appears with red nebulae in Death Valley National Park, California; Tafreshi on assignment in Zion National Park, Utah (photo by Oshin Zakarian); ‘Lausanne New Moon’ captures the sky above the historic Cathedral of Notre Dame of Lausanne, Switzerland

the number of satellites being sent into space to orbit the Earth. “It’s really a pain,” Tafreshi admits. “They appear on so many images. On long exposures, it’s a major issue, and the number of satellites is increasing dramatically in the next few years.”

Despite years spent gazing up into space, Tafreshi has yet to capture any solid examples of extra-terrestrial activity. “I’ve recorded many things

I initially didn’t realise what it was. We could call them UFOs,” he says. “But over time, it was explained to me by an expert, and either what I saw was a very bright meteor, or a rotating satellite flare, or a rocket-related phenomenon. So far I haven’t captured anything that wasn’t explained. But there are things my colleagues have captured that are still not explained. We just need more time to explore this.”