COUNTRYSIDE VOICES

there

The groups that are making the countryside more accessible to all Getting out

The magic of meadows

Why these amazing habitats are soothing for the soul

When urban meets rural

An inside look at the pressures facing one West Country village

Living history

From a local shop to ancient barns, discover our oldest rural relics

Changing times

With an election due in the coming year, we’ve been busy getting our core messages across to politicians and will continue to put rural concerns on the government’s agenda – do see the news pages for more about our work on affordable housing and on getting more solar on our rooftops, and how you can get involved.

There’s also a summary of changes we’ve achieved in the Levelling-up and Regeneration Act, which I know will be important for many of you campaigning in local groups.

At times of change, however, it’s heartening to be reassured over the resilience of our countryside communities, and Anna Jones explores that in her personal piece on new arrivals and change in one English village. And in articles on helping people with disabilities to explore different countryside experiences and in gathering new communities to enjoy connecting with nature, we continue to promote the pleasures of our green – and blue – spaces.

Members will find their guide included in this issue with, this year, an increased number of homes and gardens across the country with offers to those producing their CPRE cards. I do hope you take advantage of them – and our wider countryside – as the daylight hours get longer.

Roger Mortlock Chief ExecutiveHomes in short supply

The affordable housing crisis in the countryside isn’t going away. As recent CPRE research has highlighted, 300,000 people in rural England are on waiting lists for social rented housing, and there has been a shocking 40% increase in rural homelessness in just five years. Our analysis showed that rates of rough sleeping are higher in the worst-affected rural areas – Bedford, Boston, North Devon, Cornwall, Bath and North East Somerset, Torridge and Great Yarmouth – than in many cities.

The growing disparity between rural house prices and rural wages, and the proliferation of holiday lets and second homes, pose a very real threat to the survival of rural communities. Many young people, in particular, are being forced out of the areas where they grew up due to a lack of genuinely affordable housing. Current planning policies have done little

or nothing to change the situation, and we fear that last year’s latest National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) revisions don’t go far enough to help, although the recent announcement on regulating short-term lets is very welcome.

With a general election due in the coming year, we’ll be campaigning for the future government to address the crisis. We want to see an increase in the minimum amount of genuinely affordable housing required by the NPPF, along with ambitious targets for the construction of these properties.

And, crucially, what’s classed as ‘affordable housing’ should be redefined to directly link to average local incomes. We’re also calling for more support for communities who want to deliver small-scale affordable developments in their neighbourhoods. And we’ll be monitoring the impact of new rules on short-term letting, as we want to see affordable housing remain in the hands of local people.

Download our recent report Unravelling a crisis: the state of rural affordable housing in England from cpre.org.uk/resources

In numbers: Local Green Spaces

7,286

771

80%

LGSs have been designated nationwide since 2012 LGSs were designated between June 2021 and 2022 were designated in neighbourhood plans (and 20% in local plans)

The Local Green Space (LGS) designation was introduced in 2012 as a tool to safeguard the smaller areas that people value for nature, beauty and recreation. But while our latest research on LGSs shows that hundreds have been designated in recent years, some of the most deprived areas of the country are lagging behind on protecting their green spaces. LGS take-up also varies greatly nationally; while London increased its LGS tally by 64% in 2021-22, neither Blackpool nor Hull have any.

To ensure we all have continuing access to green space, CPRE is calling for more communities to be empowered to engage with neighbourhood planning – particularly in the north and in urban areas – and a more consistent approach to LGS designation nationally. Download our latest LGS report from cpre.org.uk/resources to learn more. And thanks to all those who shared your favourite green spaces for our #LoveGreenSpaces project – view our compilation video at cpre.org.uk/ tell-us-about-your-favourite-local-green-space

CONNECTING PEOPLE AND COUNTRYSIDE

How our nationwide network is inspiring local communities

Oak saplings planted

CPRE Shropshire enlisted the help of local young people to plant saplings grown from acorns gathered from a threatened oak tree. Thought to be around 500 years old, the ‘Darwin Oak’ (so-called because naturalist Charles Darwin’s childhood home was nearby) could be felled to make way for Shrewsbury’s controversial North West Relief Road. The saplings will form part of a 100m hedge on a farm near Ratlinghope, as part of our group’s busy season of hedgerow planting and restoration.

Pointing the way

Work is well under way on CPRE Lancashire, Liverpool City Region and Greater Manchester’s National Lottery Heritagefunded joint project with the Ramblers to create a Greater Manchester Ringway, joining up footpaths across all 10 of the city region’s boroughs. Oldham and Bury were the first sections of the 200-mile trail to be marked out with signposts, with the waymarking due to be completed this summer. The route is designed to be easily reached by public transport, connecting more people than ever with local green spaces.

Volunteers wanted

Last year, thousands of you joined our Hedgelife Help Out survey, as part of the national Big Help Out. Look out for more CPRE volunteering opportunities, including our new Online Campaigns Activist role, during this summer’s Big Help Out, which kicks off on 7-9 June (thebighelpout.org.uk/volunteer).

Making rooftop solar a reality

We need to rapidly decarbonise our energy system to significantly reduce our impact on the climate. We could be generating clean, green energy on roofs across the country by unleashing the full potential of rooftop solar –and CPRE’s latest piece of research explores how to make that happen. Carried out by WPI Economics on our behalf, it looks at how other major economic powers worldwide are advancing rooftop solar. Policies range from the financial incentives that are powering a rooftop revolution in Germany to Japan’s ‘zero-yen

solar’ scheme, which installs solar panels on homes for free if the owners commit to buying the resulting energy in the long term.

We want to see the government commit to a target of at least 60% of the solar energy required by 2035 being delivered through rooftop solar. This report shows it’s absolutely credible to do that – but the government needs to be more ambitious and innovative in its approach.

Download the report from cpre.org.uk/resources

WHAT TO DO THIS SEASON

Use your members’ guide

With spring holidays in view, now’s the time that many of us will be looking to visit historic houses, gardens and other rural attractions. Members will find our 2024 Members’ Guide enclosed with this issue, offering discounts at nearly 100 properties, such as Cumbria’s Morland House (above).

Enjoy an exclusive reader offer on The Oldie

The humorous magazine The Oldie is offering CPRE members a trial subscription of six issues for £6 – a saving of £25.50. For every trial subscription taken out, The Oldie will also donate £5 to CPRE’s work.

Go to checkout.theoldie.

An outdoors for all

We all benefit from spending quality time in green and blue spaces, whether that’s a walk in the woods, a spot of wild swimming in a local river or an off-road bike ride. That’s why we’ve joined forces with 35 other environmental organisations and governing bodies to form the Outdoors for All coalition. Its manifesto is simple: extend responsible access to outdoor spaces. Together, we’re calling for new legislation to open up more of our countryside, including restricted woodlands, waterways, riversides and downlands, for public enjoyment. A new bill would help deliver the government’s commitment to ensuring that all of us live within a 15-minute walk of an accessible green or blue space.

CPRE was founded with the aim of ensuring a ‘countryside for all’, and we’ll continue to tackle the barriers that can make it difficult to access.

co.uk/offers and enter code ‘CPRE 2024’. Offer valid for UK addresses only. After receiving your first six issues, you can either cancel the subscription or continue at a reduced rate of £25.75 for every six issues thereafter (a saving of 96p per issue).

Win a countryside read

Many stories of rural Britain remain untold, with the lives of its peasants, farmers and craftspeople often going unrecorded. Author Sally Coulthard’s latest book, A Brief History of the Countryside in 100 Objects (HarperNorth), explores how the artefacts they left behind, from toys to tools, provide a connection with these rural forebears – while on page 22 this issue, Sally writes about some of our oldest country landmarks. We have three copies of Sally’s book to give away. To enter the draw, email your name and address to cpre@ thinkpublishing.co.uk with ‘Objects’ as the subject heading, by 30 June 2024.

Top priorities for the countryside

With a general election due in the next year, we’ve been clear about what our countryside needs from the next government. Our own general election manifesto sets out four key demands. First and foremost, we need a planning system for people, nature and the planet; one with democracy at its heart that also properly addresses the huge threats posed by the climate and biodiversity crises.

Secondly, we need to fix the broken housing system that has priced so many rural working people out of the places they call home.

Thirdly, we want to see more investment in the countryside next door: the Green Belt land that enhances the health and happiness of millions in our towns and cities. And finally, we’re continuing to call for a revolution in rooftop renewables.

Find our full general election manifesto at cpre.org.uk/resources

The final Act IN FOCUS

Getting started is easier than you might think, and as a CPRE supporter you can even write your will for free.

Writing a will is the best way to ensure your wishes are carried out the way you intend. After considering your loved ones, a gift to CPRE in your will could help ensure the future of our work to promote, enhance and protect the countryside we all know and love.

CPRE worked hard to influence the government’s Levelling-up and Regeneration Bill, both individually, and as part of the Better Planning Coalition of housing, planning, transport and heritage organisations. Now that the Bill has become an Act, we summarise some of the key campaign gains:

National Development Management Policies (NDMPs): This new type of planning policy set out to put key issues in the hands of the Secretary of State, with no public or parliamentary input – something we challenged from the beginning, with huge support from our members. While NDMPs remain part of the final Act, we were able to ensure that the public would be consulted on all new national planning policies, except in exceptional circumstances.

Nature recovery: Following campaigning by Wildlife and Countryside Link and the Better Planning Coalition, the final Act strengthened the duty on public bodies to

protect National Parks and Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty, and gave local authorities’ own local nature recovery strategies more weight in planning decisions.

Social housing: Work spearheaded by our coalition ally Shelter, and supported along the way by CPRE, managed to secure a key reform around one of the biggest barriers to building social homes: the price of land. Local authorities will now be able to purchase land for social housing and vital infrastructure at cheaper prices.

Local Voices

NEWS AND CAMPAIGNS FROM ACROSS THE COUNTRY

Marking 100 years

PEAK DISTRICT AND SOUTH YORKSHIRE

CPRE Peak District and South Yorkshire is celebrating its centenary in 2024, having started life as the Sheffield Association for the Protection of Rural Scenery in 1924 before becoming part of national CPRE in 1927. To mark the occasion, the group has commissioned a new biography of its founder, Ethel Haythornthwaite – find out more on page 21. It is also planning a range of centenary talks, walks and activities this year, including working with volunteers and community groups to manage Haythornthwaite Wood (pictured below). This small woodland, planted by the group in Sheffield’s Green Belt in 1994, is dedicated to Ethel and her husband, Gerald. A hedgerow is being restored here as part of the group’s ongoing Hedgerow Heroes project work.

Green Belt vs the film industry BERKSHIRE/BUCKINGHAMSHIRE

Local groups in Berkshire and Buckinghamshire are facing similar threats at present – proposals for largescale film and TV studios on protected Green Belt land in their counties. In Buckinghamshire, the plans are for a studio near Little Marlow, on land that is earmarked to become a country park in the Wycombe local plan. Meanwhile, CPRE Berkshire has objected to the revised version of a speculative application for a studio complex reaching up to seven storeys high on farmland in Holyport, near Maidenhead. This last proposal comes from an investment firm rather than a film company, and our group believes it could open the door to future housing development if the plans, as it suspects, prove unviable. With numerous film studios already across the counties, both local groups are calling for Green Belt protection to be upheld, arguing that no special circumstances exist in either case to justify the further industrialisation of the countryside.

Mattphoto/Alamy

Mattphoto/Alamy

Wild Mannington NORFOLK

One of Norfolk’s hidden gems, the Mannington Estate, was among the first country estates to introduce a countryside management scheme with public access and interpretation. Its grounds include a variety of habitats including ancient woodland, wet wildflower meadows and unimproved grassland. CPRE Norfolk will be joining the estate’s Wild About Mannington Day on 15 June, a celebration of the county’s wildlife and a ‘Bioblitz’ nature survey of the estate by volunteers (find out more at manningtongardens.co.uk). The group has long had a good relationship with Mannington, and 11 trees have been planted in memory of past supporters, volunteers and trustees in the estate’s chapel garden. On non-event days, CPRE members can enjoy 50% off entry to Mannington – see your members’ guide for details and opening times.

Championing Dorset DORSET

The Hampshire Hedge HAMPSHIRE

CPRE Hampshire has made great progress this year on its initiative to create a Hampshire Hedge that will connect up the South Downs and New Forest National Parks. The hedge will create a nature recovery corridor through the heart of Hampshire, linking woodlands, meadows, nature reserves and Sites of Special Scientific Interest. Working with community groups, schools and landowners, our group has been planting, laying and restoring hedges on a series of volunteer action and training days, and is aiming to have completed 5km of hedgerow by the end of March. It has also set up three successful hedgelaying traineeships to pass on the craft, and will be opening applications again this summer. Find out more, including how to get involved or become one of the project’s valued funders, at cprehampshire.org.uk

CPRE Dorset was recently delighted to welcome Kate Adie CBE as its president. The renowned broadcaster and author has been a fan of the countryside since growing up in Sunderland, and has lived in Dorset for more than 12 years. At the group’s AGM in late 2023 she spoke about how the world is changing, and the need to keep modern farming in harmony with the countryside. ‘We lead busy lives, we need to make our mark, stand up for our principles and be happy to have a chance to help it,’ she said. Kate and other CPRE Dorset representatives recently joined a hedge survey in Chilfrome as part of the Great Big Dorset Hedge project, a campaign to restore and extend the county’s hedgerows that is being supported by the group.

Stronger together HEREFORDSHIRE

Stretching from mid-Wales all the way to the Severn Estuary, the River Wye is one of Britain’s longest and most iconic rivers. But, as we’ve reported here in Voices, it is also facing serious threats, including manure and chemical pollution from local farms. Amid huge local concerns about the wellbeing of the river, local charity River Wye Preservation Trust has decided to merge with CPRE Herefordshire to unite their efforts to safeguard the Wye. The latest tool in this mission is Wye Viz, an online app that showcases the pollution data collected by dedicated citizen scientists. The group will be using this powerful evidence to support their call on local and national government and regulators to act.

Kate Adie representing our group at the 2023-24 Dorset Tourism AwardsYour Voices

Letters and emails from our members, and how to get in touch

Starletter

SHOUT IT FROM THE ROOFTOPS

Over 10 years ago I wrote [to the authorities] asking why houses were being built without solar panels, and was told this wouldn’t change before 2025 at the earliest. Why do we have

Not every cycle path is as safe as this off-road route in Derbyshire

to wait? It is going to cost more to install solar on existing buildings than to do it as they are being built. Weather permitting, you could have free electricity and even make money. A win-win solution, helping to save our countryside and planet. Margaret Brown, via email

Editor says: We heartily agree about the potential for rooftop solar, which is why we’re calling on the government to commit to a target of at least 60% of the solar energy required by 2035 to be delivered by this means – see cpre.org.uk/solar

Margaret wins a goody bag from LittleLeaf Organic (littleleaforganic.com), an awardwinning sustainable company in Hampshire providing bed linen, pyjamas, baby clothes and handkerchiefs, all in the finest organic cotton that doesn’t cost the earth.

Counting houses

Your ‘Closing the loophole’ story in the autumn/winter edition misses a vital point: at least in South Oxfordshire, the planning arguments are not about ‘whether local authorities [have] allocated enough sites for housebuilding’, but whether they have completed the number of houses dictated by central government. This seems to me iniquitous, because Local Planning Authorities (LPAs) like South Oxfordshire District Council (SODC) can only approve or reject planning applications. Completions are in the hands of developers or their builders, and LPAs are at their mercy when the number of completed houses is counted.

Time after time at planning enquiries, I have seen highly paid lawyers demolish SODC’s claim to have an adequate supply of houses, often with the aid of a firm that employs agents to check whether houses have been completed. SODC has approved more than enough applications to meet the targets imposed upon it, but planning law deliberately overlooks this. Kester George, via email

Editor says: You make a very good point, Kester, and one

that was too often an issue under the old National Planning Policy Framework, and a big reason why we called for change. Our understanding is that the new policies will address this by effectively making a local authority safe from appeals for five years once its plan has been adopted. There are, however, still large gaps in plan coverage, and the risk of appeals is still a concern in areas where there are such gaps.

On our doorstep

Reading the autumn/winter issue made me reflect on the effect the conservation work that the charitable trust I co-founded with my husband and a friend in 1986, the Halesowen Abbey Trust, has had on the countryside on our doorstep. In 2014 we purchased a neglected 18thcentury walled garden in Leasowes Park [left]. We have taken part in Britain in Bloom, planted a hedgerow and created a wildlife pond, meadow and heritage orchard. Over the years we have planted more than 10,000 trees in the surrounding countryside. We transformed a former industrial landscape into

a beautiful area with woodlands, and restored public rights of way.

Carole Freer, Halesowen, West Midlands

Road rage

Having just read ‘Your Voices’, I despair at the letter encouraging everyone to get on their bikes. Excuse my ire! I’m rising 90 years old and am pretty fit, but I’m absolutely convinced that I would be much more of a danger on the roads on a bicycle than I have been in my car. I live in a hilly part of Surrey, and the writer expects the young and old, and many in between, to cycle among the commuting car drivers on modern roads. In the countryside it would be even more hazardous. Having cycle paths on every road would help, but not entirely – most junctions are not safe for any cyclist.

Gwyneth Fookes BEM, via email

We’d love to know what you think of the magazine and the issues we’ve covered.

email us at cpre@thinkpublishing.co.uk

!i'll X

(formerly Twitter) via @CPRE

write to us at CountrysideVoices, Think, 65 Riding House Street, London W1W 7EH

We are unable to respond to all letters, and those published may be edited for length and clarity.

The rooftop revolution

From car parks, factories and schools to community centres, churches and mosques, many buildings nationwide are joining the solar revolution and reaping the benefits of generating clean energy on site. Chester Cathedral is among the latest in a growing number of places of worship to install discreet, roof-mounted solar panels, allowing the Grade I listed historic building to produce and use its own electricity.

The 206 panels on its nave and south transept are able to generate up to a quarter of the building’s total energy consumption, and are helping meet the cathedral’s fast-rising energy costs.

‘For us, sustainability includes ensuring that we are doing everything we can to reduce our carbon footprint and lessen our negative impact on our planet, and reduced costs mean we can fund the essential work carried out on

our magnificent cathedral,’ says the Dean of Chester, The Very Reverend Dr Tim Stratford – shown here (left) blessing the panels with the Bishop of Chester, Mark Tanner, after their installation.

As reported on page 4, CPRE is calling for more measures to encourage a rooftop revolution that will realise the full potential of roof-mounted solar to reach our national net-zero energy goals. Find out more at cpre.org.uk/rooftop-solar

‘It’s rewarding to help people and highlight nature’

Wildlife broadcaster Nadeem Perera

explains why he’s passionate about connecting marginalised communities and young people with the natural world

I can’t remember a moment when I wasn’t into wildlife. I put it down to my mum, because she’s from Sri Lanka, and although I grew up in east London, we used to go on holiday there every year, and you can’t escape wildlife. If you put clothes out to dry, you’ll get monkeys ripping it off the line later; if you went to the toilet in the night, there’d be a snake! When I got into birds, I was having a turbulent time in secondary education. At the age of 15, I stopped going to school and started just walking around places instead. One day I saw a green woodpecker. This bright-green bird, with a red cap and black mask – I’d never seen anything like it. Before I knew it, I was going out to look for it again. Then one bird turned into two, three, four... Next thing you know, I’m the most dope [cool] birdman in the UK!

Spending time outdoors 100% helped my mental health. Any teenager, let

alone a black kid from a single-parent family in east London, will tell you that life can feel overwhelming at times. You’ve got constant pressure around what you’re going to be when you grow up, doing your homework, what grades you’re going to get... That’s not easy for a kid who doesn’t even know who they are yet. But when I was outside in green spaces, I didn’t feel any of those pressures; I just felt welcome.

I held onto that feeling, and almost became addicted to it. I liked the idea that while all the people around me, and myself, were so stressed and consumed by their individual lives, there are millions of non-human lives out there that don’t care about any of the stuff we’re stressing about. All they’re doing is making a home, feeding their babies, feeding themselves, and staying alive. Life really can be that simple.

According to UN regulations, London is considered a forest. Over 40% of its public land is green space, and more than a fifth is wooded. I grew up visiting those spaces, such as Thames Barrier Park, where I saw my first kingfisher, Barkingside Recreation Ground and Hackney Marshes. I properly fell in love with birding in Richmond Park. I used to travel there a lot, and it’s where I saw my first sparrowhawk kill. It’s still my favourite place in the world.

At this time of year, I look forward to hearing the song of the chiffchaff. That really lets me know summer is coming. But my favourite bird is a year-round one: the carrion crow. They’re so clever, watching them is like watching a TV drama. Plus, they’re black, and they roll in groups, and people have negative stereotypes about them. So I can relate a lot to crows!

Flock Together started life as a birdwatching club in 2020, during the first pandemic lockdown. It was a time when we were all realising how important green spaces are to us. Meanwhile, the George Floyd case was

going on in America, racism and police brutality were in the spotlight, and Black Lives Matter protests were taking place globally. Our community was going through a very difficult time. I connected with another nature lover, Ollie, on Instagram, after I responded to a couple of his posts about birds. He told me he’d had this idea to set up a club that would open up nature to people of colour and challenge under-representation in the outdoor space. Together, we knocked up a flyer and put it out there.

On our first walk, in Walthamstow Wetlands, there were about 15 people. By the third walk, we had around 60. On one of our latest, in Epping Forest, we had more than 300. That was brilliant, because from the beginning, we wanted it to be massive. There’s a whole global community of black and brown people who could benefit from nature, just as nature has benefited me and Ollie as individuals. Our chapter in Toronto quickly popped up, then one in Tokyo. It’s brilliant to see what it means to people, and it’s rewarding to help people and highlight nature at the same time.

Our community has never had a massive part to play in the conversation about nature. But I feel optimistic that the situation is changing, and Flock Together is at the forefront of that.

It’s beautiful to see all these groups springing up that connect marginalised people with nature, and it’s good to see national organisations paying more attention to our stories, and valuing our input a bit more. We’ve never had the chance to influence nature, and it’s going to take time –but when we do get there, it’s going to be amazing.

Young people do care about nature. But some find it boring – and that’s not their fault, but the fault of whoever is conveying those messages to them.

I’m also a youth football coach, and this year Flock Together will be working with pro football teams to take their academy kids out and connect them with nature. You have to cross-pollinate nature with things they enjoy doing. It’s not difficult – listen to the kids!

I’m hopeful about the future of British wildlife, because new voices are being

Wildlife presenter, activist and youth sports coach Nadeem Perera has appeared on Springwatch, The One Show and other programmes. With Ollie Olanipekun, he is the co-founder of birdwatching collective Flock Together, and co-author of Outsiders: Reclaim your place in nature (Gaia).

heard, and new ideas are buzzing around. Through my coaching, I’m connected to the next gen, and they’ve got a lot of ideas and a lot of energy. In 10 years or so, these are the people who are going to be playing critical roles in decision-making. And if they carry on as I think they’re going to, the future for wildlife in this country is going to be very bright.

When urban meets rural

Rural communities are often characterised as a mixture of ‘locals’ and ‘incomers’ – but how does that play out in everyday life?

Anna Jones investigates the changing face of one English village

In 1912 my great-grandparents, Will and Bessie Davies, married and set up home in the parish of Baschurch in north Shropshire. Will was a blacksmith and Bessie an office worker in the village hospital. Back then, Baschurch had a train station; a fortnightly livestock market selling cattle, sheep and pigs; and a working men’s club built for the community by the lord of the manor and chief landowner. In 1922, my grandmother, Netta, was born.

After World War II, Netta married my grandfather, Wilfred, and they moved into The Smithy with Will and Bessie –a rambling old timber-framed house with an outdoor toilet and no running water or electricity. My mother, Avril, was born in Bessie’s ‘best room’, among the ‘posh settees and polished brasses’, in 1951.

When I track this period, flicking through the pages of Kelly’s Directory of Shropshire from 1885 to 1941, I can see how much Baschurch changed. While the population remained pretty constant, hovering at around 1,500, land ownership shifted from the lord of the manor to the local farmers; the little hospital where Bessie worked closed down; and electricity lit up the village for the first time (though it didn’t reach The Smithy).

In 1964, Bessie passed away from heart problems in the same room where my mother was born. Will, who’d always vowed ‘I’ll go when Bessie goes’, died four days later. In 1965, the same year Baschurch railway station closed, The Smithy was sold for £500, and my family story in the parish of Baschurch came to an end.

Baschurch today

Nearly 60 years later, in November 2023, I find myself watching a parish council meeting in Baschurch Village Hall, to research this very article. I’m wondering if Will and Bessie would even recognise it. The population has boomed to almost 3,000, and the average house price is north of £350,000. A quick snoop online tells me their former home, now called The Old Smithy, is worth more than double that.

There are new houses – big houses – everywhere; many standing loud and proud on what were once surrounding

fields. It feels much busier. There are actual traffic jams.

The village hall is freezing. Cheerful bunting feels incongruous with the six members of the public sitting on hard plastic chairs, wrapped in coats and scarves, on this dark winter’s night. Twelve parish councillors, sitting around tables arranged in a horseshoe shape, are discussing a range of issues – but planning is by far the dominant theme.

‘Baschurch has had its quota of development,’ says one councillor. ‘Are we within our rights to refuse more?’

The six parishioners share their feisty objections to a planning application for 10 dwellings on an unadopted lane.

‘It can’t take 20 more vehicles!’

‘Every time they put a new house on our lane, they have to dig up the road again and put all the cables in. There were six houses when I moved in – now there are 14.’

My ears prick up when the chairman mentions 20 affordable homes being built on the north side of the village. They debate the recent addition of solar panels, with comments ranging from ‘they’re a good thing’ to ‘they’re a complete mess, pointing in different directions’.

Jones is a Shropshire-based writer, broadcaster and farmer’s daughter. Her book Divide: The Relationship Crisis Between Town and Country was published in 2023 by Kyle Books.

Community life

I leave the meeting at 10pm, in no doubt of the crackling tension around housing in Baschurch. I need to get to know the village on a more casual level, somewhere I feel comfortable chatting to people. So, I sign up to a Pilates class.

It’s January 2024, and I’m back in the freezing cold village hall. Liz, secretary of the village hall committee, is pushing a broom around, giving it a quick spruce up before the class arrives.

She tells me Baschurch is full of ‘people who have moved in’, especially young families who come here for the popular school. Liz has only lived here

for two years but threw herself into community life, organising events in the village hall and trying to drum up interest by putting flyers through letterboxes. ‘It’s a funny old village,’ she says. ‘It’s difficult to get people to come along to things.’

Happily, the eight-strong Pilates class couldn’t be friendlier. They invite me to join them for a coffee at the farm shop café. Everyone has moved into the village or surrounding area, either with young families or after retirement.

Amanda moved eight years ago from Lancashire. She works full time but says it’s the retirees who keep Baschurch buzzing: ‘They’ve moved from elsewhere – London way, maybe – sold houses there, bought cheaper houses here so have lots of disposable income. That’s why I think the village pub is always packed on midweek lunchtimes.’

None of them describe themselves as a local. ‘I’m not sure who the real locals are,’ Amanda says, ‘maybe the farmers?’

New arrivals

I’ve always known Shropshire as a county of ‘locals’, perhaps because I come from farming stock, so I’m surprised to find that many people I meet come from somewhere else. And they’re not all retirees. My 37-year-old friend Nicola Kurt moved to Baschurch from London in 2022 after her husband, a vet, got a job near Telford. We’re sitting in the kitchen of her new-build house on a seven-year-old housing estate on the edge of the village.

‘The people here are lovely,’ she says. ‘I have to build in an extra 20 minutes on my dog walk because I’ll end up chatting away with my neighbours.’

She pauses. ‘At times, I have found it hard. I have to get in the car to get a big shop or do anything really. I miss being close to everything and it can get a bit lonely.’

Given Nicola’s experience of social isolation, when I ask for her thoughts on the future of rural villages like Baschurch, I’m expecting her to call for more services; more going on. I’m staggered when she says the opposite: ‘I think they will expand, but I hope they don’t. I think the beauty of rural communities is their old character. They’re peaceful, calm, slower-paced and unspoilt. You don’t

want too many new builds. It just becomes another town.’

‘So, where’s the cut-off, then?’ I ask.

‘Now. No more.’

‘But everybody says that after they’ve moved here!’

We laugh at the irony. I repeatedly hear this sentiment in Baschurch, and many other rural areas. People move in, find their place of peace and tranquillity, and become instantly protective over it. I find it fascinating how each new wave of ‘incomers’ somehow believes the next wave will ruin it, and on and on it goes.

Development pressures

Councillor Matt Feline is an exception. ‘My house is 15 years old, so I’d be a

Anna’smum(left)revisitsheroldhome andmeetsthenewowner(right)

hypocrite if I turned round and said I don’t want any development,’ he says.

Matt is vice chairman of Baschurch Parish Council, but he’s speaking to me purely as a village resident. He’s keen to reiterate that these are his views – not the council’s. Originally from Reading, he moved to Baschurch in 2018.

I ask him about the ongoing development of 20 new affordable homes, for social rent and shared ownership. It’s a touchy subject, as I know that the parish council is opposed to it.

‘We’re all for affordable homes,’ says Matt, ‘but we wanted to integrate our affordable housing into different estates so it’s an integrated community, rather than people on lower incomes living in one area.’

After weeks of emailing, I’m invited onto the building site for a look around.

‘There were very few objections to the planning application, and I think that’s because people know these homes are needed,’ says Kerry Bolister, director of development at Shropshire-based Housing Plus Group.

‘Most people aren’t in a position to buy their own home when they move out of the family environment, and those people might be providing care services within the village, they might be teaching assistants here, they might be shop assistants. If the village doesn’t provide housing for its lower-paid workers, where are they going to go? This is not an isolated area of build – in my view, it is integrated.’

I decide to knock on some doors directly opposite the building site. The first person I meet, a semi-retired teacher, is all for it. Seconds later, I bump into an elderly couple walking down the street. Brian and Glenis Bendall have lived in Baschurch for 40 years, after moving from a rented smallholding three miles away. After saving hard for nine years, they bought their first house in the village in 1984. While their children have also been able to afford homes in Baschurch, their grandchildren cannot.

People move in, find their place of peace and tranquillity, and become instantly protective over it

For that reason, the couple welcome more affordable homes. But they are concerned about the increasing pressure on local infrastructure: ‘The doctor’s surgery can’t expand, you have to wait three weeks for an appointment, and there’s not enough parking,’ says Glenis.

‘And our boiler is only just coping with the low water pressure because we live at the end of the pipe,’ adds Brian.

Change is a constant

My last stop is The Old Smithy, where Mum was born – and she agrees to

come with me. The present owner, Mandy Wright, has lived here since 1998 after moving from Surrey with her family. She invites us in and we chat for over an hour, with Mum reliving memories, her eyes sparkly with tears as she pictures her grandad leaning against the back door frame, watching her race up and down the garden path on her tricycle. As they study Mum’s old photos together, it’s clear both women share a deep love of this old house.

‘It was like going back in time,’ Mum smiles afterwards, ‘but everything has to change, doesn’t it?’

I’m struck by the dichotomy – how we’re so resistant to change, yet amazingly good at adapting to it. And Baschurch, like rural villages all over England, will continue to ebb and sway in the choppy waters of resistance and, ultimately, acceptance; for change really is the only constant.

The magic of meadows

Created to feed livestock, meadows provide a stunning habitat for wildlife – and labours of love are returning many to their former glories, says Iain Parkinson

Just like the botanical arrangement of a wildflower, a meadow is an intricate and beautiful design where form and function are subtly interwoven. Full of colour and character, these flowery worlds are wonderful places to see an abundance of plants, insects, birds and other wildlife; but they are not quite as wild as first meets the eye. Meadows are an ancient part of the agricultural landscape, managed by generations of farmers to produce hay to feed their livestock.

The annual cycle of hay cutting followed by livestock grazing creates an ecological balance where a dazzling array of flowers, grasses and other species have learnt to coexist as part of a tightly woven plant community. A meadow’s beauty, then, is derived from its utility.

Yet with livestock farming on the wane and modern methods of producing winter fodder, such as silage, replacing traditional hay production, meadows have found themselves marginalised. Pushed to the extremities

by a rapidly changing agricultural landscape, surviving examples are now increasingly rare – but those that remain still have the power to capture hearts and minds.

In recent times there has been a welcome shift in public perception, with the more naturalistic design of flowery grasslands becoming an increasingly acceptable sight in our parks and gardens, and alongside our highways and byways.

This is good news for nature, but it’s also good news for people. There are many benefits to our health and wellbeing when we spend time in the company of nature. The classic form of a hay meadow, where the abstract designs of nature repeat over and over again at varying degrees of complexity and regularity, is the perfect antidote to the stresses and strains of modern life.

A deep connection between humans and grasslands lies latent in all of us, but given a chance, it resurfaces to heighten the senses and soothe the soul.

Regional identities

At a glance, one meadow might look much the same as another, but closer inspection at a species level reveals countless expressions of regional identity. For example, the well-drained fertile soils of upland hay meadows support a very distinctive flora, including a number of rare and threatened plants such as melancholy thistle, globeflower and the dainty wood cranesbill.

In contrast, the heavy clays of some lowland meadows, like those of the High Weald of Sussex, are often dominated by ‘tough as old boots’ species such as common knapweed and dyer’s greenweed, the latter being an important food plant for a range of scarce and threatened micro-moths and other insects.

Sandwiched between the upland and lowland meadows are the colourful grasslands of the central floodplains. The plant communities of floodplain meadows are beautifully adapted to their dynamic environment and include a range of specialised moisture-loving plants, such as great burnet, meadowsweet and devil’s-bit scabious. By virtue of their enduring character, surviving examples of floodplain meadows, such as those of the Severn and Avon Vales, demonstrate a resilience to change that owes much to the careful and constant stewardship afforded to them over many centuries by the local farming community.

Water worlds

Water is a key factor in shaping the character of meadow plant communities, and this is certainly true in the case of traditional water meadows such as Harnham Water Meadows in Salisbury, Wiltshire, and Wicksteed Water Meadows in Kettering,

Northamptonshire. What distinguishes a water meadow from other wet meadows is their specially engineered systems of sluices, channels, ridges and hatches, designed to control the spread of nutrient-rich deposits over the sward and increase the annual yield of hay. The intensive way in which water meadows were managed in the past provides an excellent example of the importance people placed on hay production. Without this most basic of commodities, livestock would have lost condition or perished in the winter, severely impacting lives and livelihoods.

Ever-changing tapestries

Despite the rapid demise of meadows over the past century, a few ancient examples survive today, providing a link to the past but also hope for the future. Many of these – such as North Meadow in Cricklade, Wiltshire, where tens of thousands of snake’s-head fritillary flowers herald the spring, or the stunning upland hay meadows of Muker in Swaledale, North Yorkshire – are protected as Sites of Special Scientific Interest or preserved for posterity as National Nature Reserves.

These grassland gems are priceless, as hiding deep within their soils and swards are the ecological blueprints that can help us to build a better future for those that remain. Attempting to recreate the ever-changing tapestry of a meadow, along with its microcosm of life, is a complex and technical task. However, despite comprehensive research on the subject, the pursuit of meadow making will never be an exact science, but more a labour of love.

Iain Parkinson is the head of landscape and horticulture at Wakehurst, Kew’s wild botanic garden. Actively involved in creating and restoring species-rich grassland around the country, he is the author of Meadow: The intimate bond between people, place and plants (Kew Publishing).

National Meadows Day, coordinated by Plantlife, will take place on 6 July, celebrating meadowlands around the country. To find out more, including how to create your own wildflower meadow, visit plantlife.org.uk/events/uk-national-meadows-day

Making waves

Not all of us can access the great outdoors equally easily – but, as Jane Yettram discovers, many groups are passionate about opening up the countryside and green spaces to those with disabilities

Lying on a surfboard, you enter a different world. ‘It puts you in the moment,’ says Ian Bennett of The Wave Project surf therapy charity (waveproject.co.uk). ‘You’re looking at the horizon; at the water coming towards you. You’re at one with nature.’

Ian, a surfer for almost 30 years, knows how much this means to him. And through the adaptive surf hub for disabled learners at Croyde, north Devon, run by The Wave Project and Surf South West, he wants to bring that experience to everyone.

The Wave Project was founded to improve the mental health and wellbeing of young people through surfing. ‘But in 2017, a mum called Nicki Palmer asked if I could take her son, George, who has multiple disabilities, surfing,’ says Ian.

‘She told me George has cerebral palsy and epilepsy, that he’s visually impaired, a wheelchair user, and has an intellectual disability. I suddenly realised the challenge – it was nerve-racking.’

A small team took George surfing. He had a brilliant time – but Ian knew they could do better: ‘Even with George’s all-terrain wheelchair, it took three of us to get him onto the beach. And putting on his wetsuit was a real struggle. I was determined to do something about it.’

Since then, The Wave Project has developed adaptive surfing hubs in Croyde, Scarborough and Cornwall. ‘We now have boards with a raised chest for people who can’t lie flat, seated boards for people who can’t lie down, and beach wheelchairs with balloon wheels.’

Super-stretchy wetsuits with arm and leg zips are easier to put on. ‘And the

icing on the cake,’ says Ian, ‘has been opening a Changing Places unit, enabling people with disabilities to get into and out of wetsuits in a dignified, clean and warm environment. We have Access for All (a group founded by Nicki) as well as the beach owners (Ruda) and the local council to thank for that.’

Croyde’s adaptive surfing team now includes both qualified instructors and trained volunteers. ‘Our volunteers are vital because some participants need a lot of support. George, for example, needs a team of five, and Cliff – a stroke survivor who surfs as often as he can – needs a team of three.’

Individuals and groups with all disabilities, and of all ages, are welcome. ‘British Blind Sport has come several times,’ notes Ian. ‘The Silverlining Brain Injury Charity has come six years

‘Disabled people deserve the same chance as everybody else to get out of their comfort zone’

running. We even took them surfing in Lanzarote.’

Tom, 44, first came with British Blind Sport, emerging from his taster session buzzing. ‘Tom now surfs frequently,’ says Ian, ‘even competing in last year’s English adaptive surfing championships.’

Surfing presented Tom, who is severely visually impaired, with valuable challenges. ‘Overcoming these challenges has improved my selfconfidence,’ he says. ‘I now feel part of the surfing community.’

For Philip, too, who has chronic arthritis and is in his 60s, surfing has been life-changing. ‘Philip, who walks with a frame and is in constant pain, says surfing is the most free and alive he ever feels,’ explains Ian.

The fact that surfing is an adrenaline sport is fundamental for all surfers. ‘I’ve been working with Activity Alliance, the leading voice in sport for people with disabilities,’ says Ian. ‘Disabled people deserve the same chance as everybody else to get out of their comfort zone. Why shouldn’t they experience the same exhilarating fear factor that I have while surfing?’

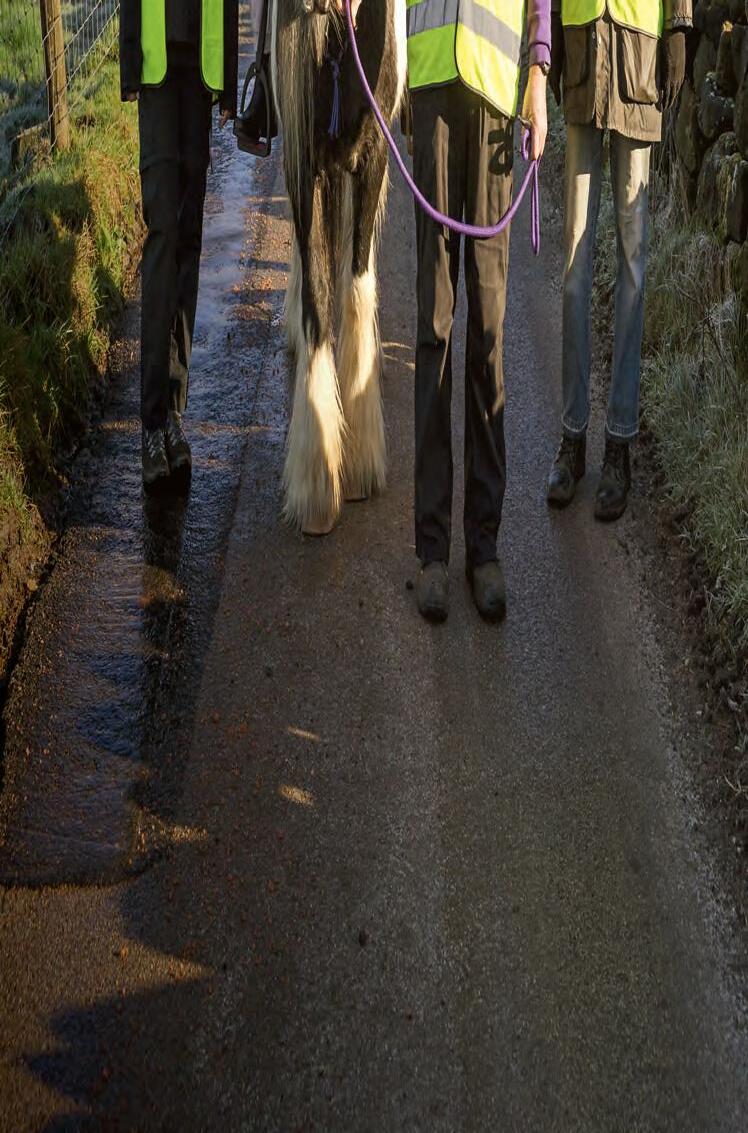

Adventures on horseback

It’s an equally exciting experience for those getting on a horse for the first time at Saddleworth Riding for the Disabled (facebook. com/saddleworthRDA) – one of many Riding for the Disabled Association (RDA) groups around the country. First-timers may be nervous, but sheltering people with additional needs from the thrill of outdoor adventure does them a disservice.

Seated boards are helping more surfers access the outdoors

that everyone treated her daughter, who has cerebral palsy, like a china doll. Getting out on a pony made her just like other children.’

The setting of Saddleworth Stables, in the foothills of the Pennines, is spectacular – and some are experiencing it for the first time. ‘Our riders aren’t wealthy, and come from different cultural backgrounds. Most have never been near a horse and never go out in the countryside,’ says Alison.

But Alison and the other volunteers are skilled in engaging riders with the horses and the landscape – whatever the weather. ‘The sun could be shining down on a child’s face while they’re sitting on a pony. Or the wind and rain could be coming sideways, with the pony’s mane flapping. But the volunteers are always smiling, saying, “Oh, look at my face, it’s all red, look at the pony’s ears – that shows he doesn’t like the rain!”

‘We tie everything together – nature, weather, environment, climate,’ continues Alison. ‘We say, “Look, what are those sheep doing? Have you seen the pheasant?” We do mindfulness too, asking, “Can you hear the pony breathing? Can you feel him breathing?” When the children return, grinning from ear to ear, their parents are so proud.’ *Name

As Alison Pickering, Saddleworth RDA co-founder, says, ‘One parent told us

There are some very real triumphs to celebrate. ‘Molly, aged nine, achieved her first RDA Endeavour Award recently, for nailing a rising trot. Those moments of success are really important.’

Molly’s mum, Caroline, was thrilled. ‘It’s an absolute joy to watch her. It’s the one thing Molly is always excited to do.’

Saddleworth RDA’s youngest rider is just four years old, but adults ride too. ‘One lady in her 50s is a double foot amputee,’ says Alison. ‘We’re also supporting children and adults with cerebral palsy, Down’s syndrome, hearing loss, ADHD, autism….’

Fourteen-year-old Abigail joined the group two years ago as part of her road to recovery after cancer treatment led to the removal of a major hip bone, reducing her weight-bearing ability. Alison says, ‘Abigail, a natural rider, has successfully competed at RDA regional level. Sitting on a pony, you’re balancing, strengthening your core, your upper body, your lower body. We don’t call it physio, but that’s what it is.’

There are vast psychological benefits too. ‘For anybody experiencing a difference, a horse doesn’t see that you’re different. A horse accepts you as you are. And a horse teaches you things. From the minute they get on, children learn cooperation and empathy – with other people, with the pony.’

When six-year-old Jackson*, who has ADHD, first arrived, he couldn’t stop running and shouting. ‘The pony backed off. I said if he wanted to stroke the

pony, he’d have to “be more horse”, because horses are calm, cool, chilled out. Suddenly Jackson was breathing quietly and stroking the horse. His parents were stunned. We have parents in tears at the change in their children.’

Sensory experiences

Bringing the therapeutic power of nature to others also motivates Sue Hooper, a leader of sensory walks for deaf and blind people.

‘During lockdown I was often in Lee Valley Regional Park – a 10,000-acre “green lung” spreading from London into Essex and Hertfordshire – and noticed groups of people with disabilities walking there,’ says Sue. ‘I wondered how much they got from it.’

Then Sue spotted an advert from Sense (sense.org.uk), a charity supporting people with complex disabilities, offering training to help people lead sensory walks.

As Sense’s Katie Sawyer explains, ‘We teach people how different senses can be used to engage with nature. This makes walking more meaningful and enjoyable for those with sensory impairments, who often have limited independence or time outdoors.’

Sue jumped at the chance to do the training, and Sense, delighted to find a passionate volunteer, helped set up the sensory walks in Lee Valley.

‘My two regular participants are Nicola, who is deaf and has little vision, and Matthew, who is deafblind,’ says Sue. ‘Their speech is limited too. Both are from a Sense residential home and come with their carers.

‘We concentrate on the flowers, the grasses, the trees. I have permission to take my secateurs and cut small sprigs of leaves and catkins for them to feel. On breezy days I hold their hands to

‘Sensory walks help carers build a closer relationship with the person they’re supporting’

grasses so they feel how things move with the wind.’

Sue focuses on the park changing over the seasons. ‘In spring, we discover new leaves, catkins, plants coming through the earth. In the autumn, it’s hips and haws, even walnuts.’

The carers take the items gathered back to the residential home. ‘They do an art activity, photographing residents’ creations,’ says Sue.

Carers themselves see benefits, too, adds Katie. ‘Sensory walks help them build a closer relationship with the person they’re supporting.’

The walks are so good for everyone that Katie wants greater numbers of people to benefit. ‘We’d love more care homes and individuals with disabilities to sign up, including from ethnically diverse communities – people from all backgrounds should be able to enjoy the countryside.’

Last summer, Sue took out a group of children with autism. ‘We brought crayons and paper to do bark rubbings. The children really enjoyed it.’

She also takes two friends with severe illnesses. ‘They walked a lot when in full health. To do that again is so freeing.’

Sue herself has gained so much –including a greater appreciation of the countryside on her doorstep. ‘To know the park through the experience of people with different needs has given me a whole new way of looking at it.’

Her enthusiasm is shared by Ian at The Wave Project: ‘Getting people into the sea, seeing their faces, is amazing. Sometimes I can’t believe this is a job.’

As for Alison in Saddleworth, others’ joy gives her joy: ‘That’s why we don’t mind getting up at silly o’clock, at times so cold our feet feel like ice blocks! That doesn’t matter when we watch 12 happy children trundle off ruddy-cheeked after a wonderful ride in the countryside.’

7 things to know about Ethel

We pay tribute to early CPRE campaigner Ethel Haythornthwaite MBE (1894-1986), with the help of her biographer, Helen Mort

1Ethel knew the therapeutic power of nature first-hand Sheffield-born Ethel married her first husband, Henry Burrows Gallimore, in 1916. Sadly, he was killed in World War I the following year, when Ethel was just 23. ‘She dealt with her grief by going walking in the Peak District, and she credited that with saving her and keeping her sane,’ says Helen. ‘Her drive to protect the countryside came out of her own experiences of finding being in nature deeply cathartic.’

2 Her campaigning helped shape today’s countryside In 1924, Ethel founded the local campaign group that would become CPRE Peak District and South Yorkshire, to protect the Peaks from development. She served as its honorary secretary until 1980, and as CPRE’s national director during World War II. In 1945, she was appointed to the government’s National Parks committee, helping make the case for the National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act 1949. This paved the way for the creation of National Parks, starting with her beloved Peak District (pictured above). ‘Ethel achieved so much but, even in Sheffield, few have heard of her,’ says Helen. ‘We need more people to know who she was, and why she mattered.’

3 She preserved huge chunks of the Peaks Ethel was instrumental in protecting many green spaces around Sheffield. In 1928, she led the successful public appeal to stop the Longshaw

As part of CPRE Peak District and South Yorkshire’s centenary celebrations this year, the group commissioned award-winning Sheffield-based author Helen Mort

personality, with a supreme gift for language and persuasion. She cared passionately about the countryside –and she made other people care too.’

5

There were many sides to Ethel

‘She cared about the countryside –and made other people care too’

Estate being sold off to developers. In 1932, she helped acquire Blacka Moor, which in 1938 became part of Sheffield’s Green Belt – the country’s first. Her tireless campaigning helped make Green Belt part of national planning policy.

4 She was nothing if not persistent How did Ethel achieve so much, in an era when relatively few women were active in public life? ‘Her financial means and her connections helped,’ says Helen. ‘Her father was a wealthy Sheffield industrialist, and there’s something fitting about her using the proceeds from that to ensure that the city’s industrial workers had access to green space. But above all, Ethel was a persistent, quietly determined

to write Ethel: The biography of countryside pioneer Ethel Haythornthwaite (Vertebrate Publishing), exploring the life and legacy of a radical who was ahead

Reading Ethel’s letters, Helen was surprised by her sense of humour, and her occasional bluntness: ‘She met the young man who became her second husband, Gerald Haythornthwaite, when he interviewed for a role at CPRE – and although he got the job, she was rather scathing about the design work he submitted!’ Nevertheless, the couple went on to marry, and spent their lives campaigning for the countryside together.

6 She had an eye on the future

‘Ethel was always thinking about the biggest challenges of the day, while looking ahead,’ says Helen. ‘If she was around today, I think she’d be active in the fight against climate change; not necessarily protesting but lobbying, letter-writing and getting the ear of those who might be able to enact change.’

7 We need more Ethels

As Helen notes, Ethel was great at uniting people from different backgrounds around a common issue, and believed in a countryside for the many. Helen hopes her new biography will inspire readers to ‘be more Ethel!’. ‘It’s an invitation to live in the spirit that she did, and care about things enough to do something about them. And, of course, enjoy the countryside, in whatever way you can.’

of her time. Due for release on 7 May, signed copies are available to pre-order now from adventurebooks.com/ethel priced £20.

Rural relics

England’s pastoral heritage is hiding in plain sight. Here, Sally Coulthard selects five of our country’s oldest surviving landmarks

The local shop

CHIDDINGSTONE, KENT

Until recently, almost every English village had its own general store. While many of these businesses proliferated in Victorian times, Chiddingstone Village Stores and Post Office may be the oldest working shop in England, dating back to the middle of the 15th century. This glorious Tudor building was once owned by Anne Boleyn’s father, Sir Thomas Bullen. Over the centuries, the premises have been home to a carpentry workshop, and used by tailors, hatters, general grocers and a post office. In fact, Chiddingstone is such an exceptional survivor of a half-timbered, onestreet Tudor settlement that in 1939 the National Trust bought not just the shop but the entire village.

The whipping post and stocks

ALDBURY, HERTFORDSHIRE

The strikingly pretty village of Aldbury is home to a stark reminder of a more brutal rural past: one of the oldest combined sets of stocks and whipping post. Medieval law required rural communities to erect and maintain their own instruments of public punishment. Indeed, royal charters that allowed a regular market or fair to take place were often only granted on the proviso that stocks, whipping posts or pillories were also erected. ‘Civic humiliation’ on village greens or market squares was often reserved for miscreants who undermined public confidence – for example, by serving short measures, gossiping, or employing deceptive trade practices such as selling rancid meat or adulterated bread. While most whipping posts and stocks still standing are 18th- or 19thcentury replacements, Aldbury’s are at least four centuries old, and are now Grade II listed.

The country pub

THE GEORGE INN, NORTON ST PHILIP, SOMERSET

The title of England’s oldest working country pub is hotly contested, but the claims made by many don’t hold up to scrutiny. Most medieval brewing was done at home, by women, and sold or bartered from domestic premises, and records of early pubs are thin on the ground. One strong contender, however, is the George Inn, thought to have been built by the monks of nearby Hinton Charterhouse to accommodate merchants travelling to local wool fairs. The earliest sections of the building date from the 14th century, and the inn is believed to have held a licence to sell alcohol from 1397.

The ancient barn

CRESSING TEMPLE BARNS, ESSEX

Author and Yorkshire smallholder Sally Coulthard has written more than 25 books focusing on nature, history and craft. Her latest, A Brief History of the Countryside in 100 Objects (HarperNorth), is out now.

The village school BURNSALL PRIMARY, YORKSHIRE

Many august organisations vie for the honour of being England’s oldest educational establishment, but few can claim to be true village schools. Burnsall Primary in Upper Wharfedale, however, was founded in 1602 and has been educating local children for over four centuries. What started life as a small grammar school for boys became co-educational in 1825. The Elementary Education Act of 1891 finally abolished fees for primary schooling, making education free to all families regardless of income. To this day, Burnsall Primary remains a state-funded school welcoming children from the Dales’ picturesque villages and outlying farms.

Cressing Temple boasts two of the country’s oldest and largest timber-framed barns. Built in the 13th century, the Barley Barn (the earlier of the two) and the Wheat Barn were part of a large farming complex run by the Knights Templar. Initially founded in the 12th century, the Knights Templar were military and religious crusaders but became inordinately wealthy from their banking and commercial side operations, including agricultural estates. These hugely impressive Grade I listed barns are now owned by Essex County Council. Cressing Temple Barns are open daily (unless an event is taking place) and admission and parking are free, although donations are welcome.

Five winters ago, we relaid a hedge in Wiltshire. The three of us – Jonathan, Harry and I – were no experts. We had only a rough idea of the principles of hedgelaying, and certainly wouldn’t have won any prizes for our efforts. We hacked and bodged and cursed – but luckily, you can’t easily kill a hazel, hawthorn or blackthorn. Cut them half through at the base, push them over and peg them down, and they’ll just grow back the stronger.

Soon, what was formerly a row of sad, wind-blown stumps with gnarled, deformed tops, once again looked like a laid hedge in winter, perhaps for the first time in two decades. Or a wildlife-laid or conservationlaid hedge, at least. The old countrymen with their billhooks, who lay hedges with such consummate skill, may favour stricter and more elegant styles: the Midland Bullock, the Leicestershire Bullfinch, the Glamorgan flying hedge…. The regional names for hedging styles are just as magically evocative of our countryside as the names of rare apple varieties, or breeds of sheep. But for maximum wildlife value, a rough-cut conservation lay is the best, as well as the easiest.

was a song-filled thicket bursting with blossoms and darting hoverflies; a linear ancient woodland.

Hedge helpers

When Christopher Hart teamed up with friends to lay a hedgerow, the results astonished them all

Thomas Smith/Alamy

Thomas Smith/Alamy

By the following spring, the old principle proved true: a relaid hedge is ‘new shoots on old roots’; and the numerous sliced and inclined pleachers, or stems, were now sending up a forest of rich new growth. The veteran stumps were magically rejuvenated, and soon it

WIN! HEDGELANDS

Christopher Hart is an author, journalist and rewilder whose forthcoming book, Hedgelands: A wild wander around Britain’s greatest habitat (Chelsea Green),

Harry, studying for a degree in wildlife conservation, carried out surveys before and after, and the results proved astonishing. Within three years, he clocked an increase of insect abundance of 40%, and an average of 6.7 extra species at each measurement site. He estimated that insect numbers might double within 10 years. Oh, and foliage density increased from 20% to 100%: a dense, impenetrable thicket of a hedge, a perfect proxy for the precious but now rare thorny thickets that once dotted our woodpastures, the most natural landscapes of this country, and the one to which almost all of our wildlife is best adapted. The implications are huge. We have some 400,000km of hedgerow in this country, but at least half are ‘relict’ – growing out and dying. Hedges don’t need to be physically removed to disappear. They’ll disappear anyway if we do nothing – and with them, the rich wild food buffet of shoots and leaves, blossoms and nectar, hips, haws and hazelnuts that supports so many species.

So the effects of relaying our relict hedgerows could be colossal, and the increase in foliage density of such a vast extent of hedge would mean major carbon capture. And all of this without planting or taking up any more room. The hedgerows are already there, their root systems deep and centuries old, ready to bud, shoot and blossom once again.

is a joyous journey around the life, ecology and history of the humble hedge. It’s released on 18 April, and we have five copies to give away. To enter the prize

draw, email your name and address to cpre@ thinkpublishing.co.uk, with ‘Hedgelands’ as the subject heading, by 30 June 2024.