Ignasi de Solà-Morales wrote in the introduction to The Museum of the Last Generation that art museums and galleries are direct products of modern society, functioning as knowledge institutions in the way that theaters and libraries once did in the past. In today’s modern society, art museums and galleries have become increasingly important, as art is now regarded as a shared possession of all social classes, no longer confined to ruling elites or religious leaders as it once was.

Museums, and particularly art museums, are cultural institutions rooted in and originating from the Western world, having undergone continuous development over the past century. The architecture of art museums and galleries has evolved in parallel with the transformations of art and artistic thought throughout different eras.

In The Museum of the Last Generation by Josep Montaner and Jordi Oliveras, published in 1985, the authors examined major museums and galleries built in Europe and the United States between 1970 and 1985—a period marked by significant changes in many aspects of the art museum. The shifts in architectural form and design during that time influenced the architecture of contemporary art museums from 1985 to 2000.

Montaner and Oliveras summarized and analyzed these changes into four main points: The programmatic requirements of museums shifted from exhibition halls to complexes that integrate multiple functions within a single site or building—exhibitions, information centers, libraries, schools, auditoriums, restaurants, shops, and more. Exhibition halls became increasingly flexible to accommodate new forms of art, replacing the traditional room-and-corridor layout leading to separate galleries. New technologies were introduced for both the conservation and presentation of art, particularly in lighting design, where all available technologies were applied to achieve optimal conditions for artworks. Finally, art museums assumed a new role as major urban monuments, becoming landmark buildings within their cities.

Montaner and Oliveras concluded in the final chapter of the same book that the most evident changes in museums during 1970–1985 can be seen through 3–4 key examples of the period. These begin with the East Building extension of the National Gallery by I.M. Pei & Partners, regarded as one of the first museums to fully function as a “center.” In the middle of the period came the Museum in Mönchengladbach, Germany, designed by Hans Hollein, and the extension of the Staatsgalerie by James Stirling, both considered the peak of the postmodern museum era, which flourished to its fullest before closing the chapter with the Louvre extension in Paris, again by I.M. Pei.

In the article “New Frontiers” published in Tate magazine recently, Raymond Ryan provided an overview that resembles a summary of the developments of museums and galleries over the past 10–15 years, leading up to the new decade and century. Ryan questioned whether art museums and galleries would continue to play an important role in the 21st century amidst numerous factors of change in today’s world: the boundless forms of art that at times verge on the absurd; curatorial practices tied to the “trends” of the information age; the influence of “superpowers” in the art world; state support for the arts; and even sex, which has always drawn public attention across eras, and which museums readily exploit in various ways. Spectacular new museums have become indispensable features of major cities in the capitalist world, with their architecture expected to be striking and often designed by renowned architects, while also

tied to commercial spaces and interests. Ryan pointed out these crucial factors of art museums in the past decade as a way to look ahead and consider the direction they may take in the decade to come.

Ryan’s article can be seen as the next piece following the research of Montaner and Oliveras, revealing both the similarities and differences of art museums between 1970–1985 and 1985–2000. What is notable is that it shows how the major developments and transformations of art museums in recent decades have tended to occur in cycles of every 10–15 years. This is the point in this article, while also observing the changes that may shape art museums in the coming decade.

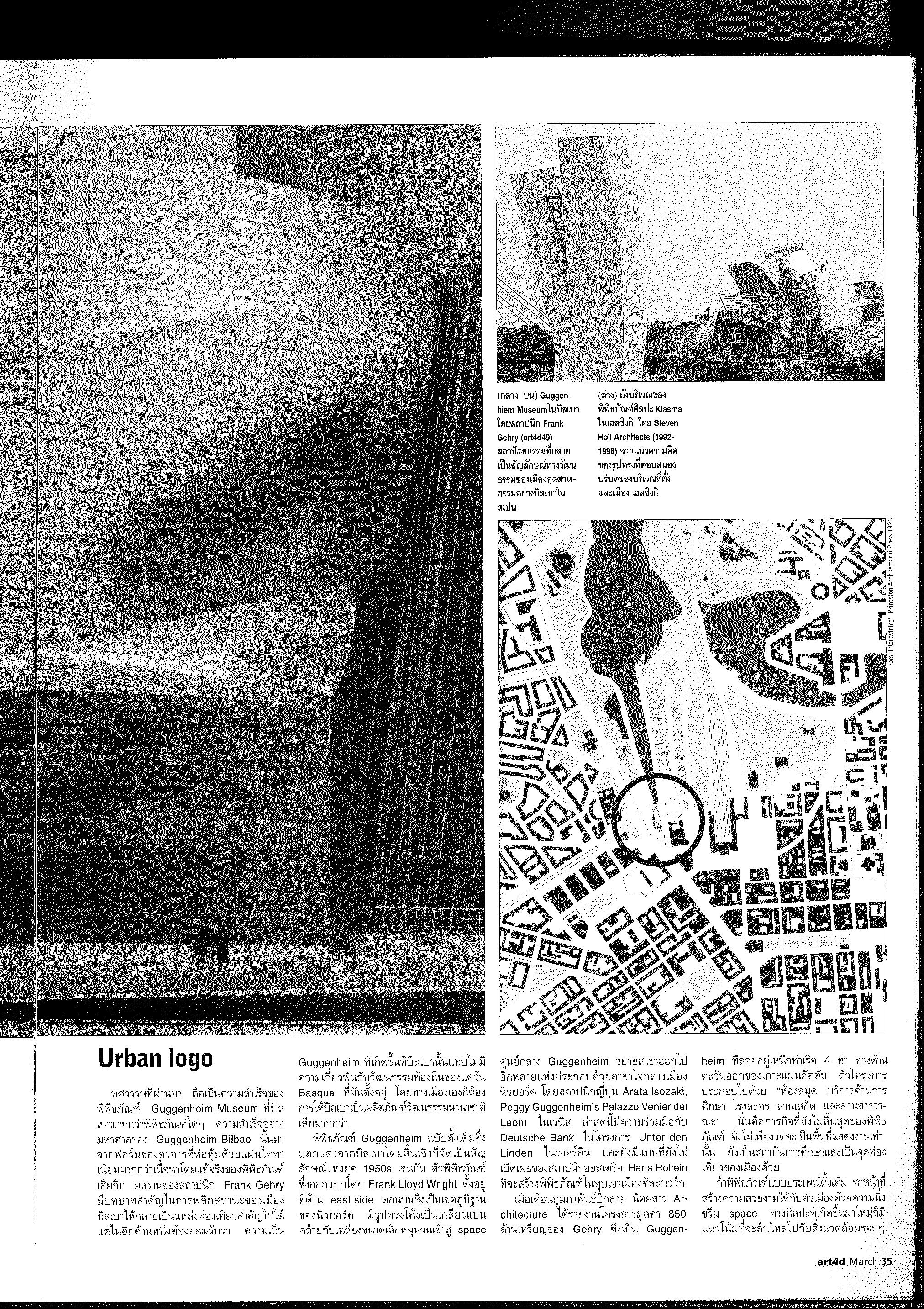

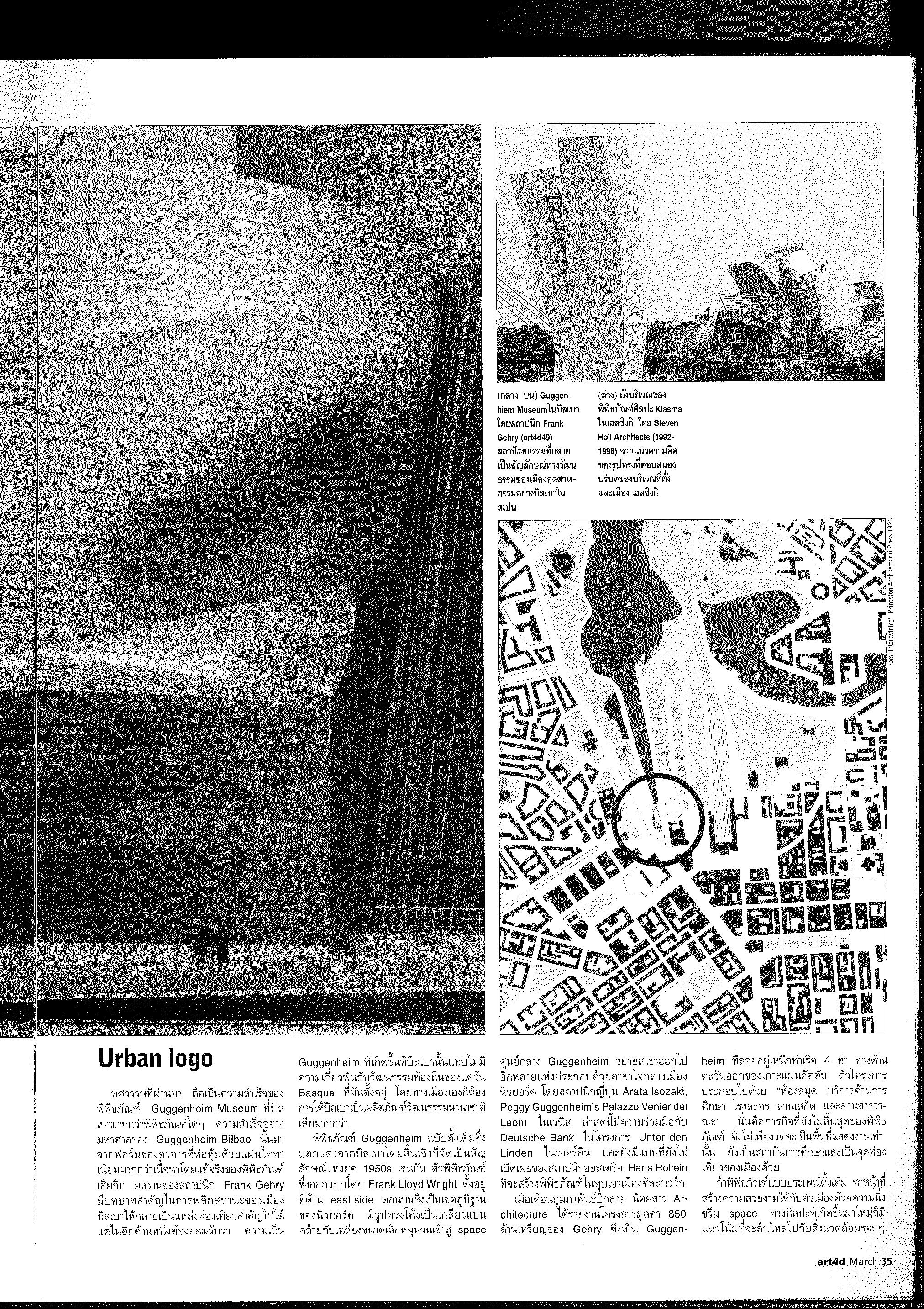

The past decade has been defined above all by the success of the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, surpassing any other museum. The immense success of the Guggenheim Bilbao stemmed more from the building’s titanium-clad form than from the actual content of the museum itself. The work of architect Frank Gehry played a decisive role in transforming Bilbao into a major tourist destination. On the other hand, it must be acknowledged that the Guggenheim in Bilbao bears little connection to the local culture of the Basque region in which it stands, as the city itself sought instead to position Bilbao as an international cultural product. The original Guggenheim Museum, entirely different from Bilbao, also stands as a symbol of the 1950s. Designed by Frank Lloyd Wright, the museum is located on the Upper East Side, an affluent district of New York. Its form is a flat spiral curve resembling a small ramp winding upward toward a central space.

The Guggenheim later expanded to several other branches, including a downtown New York location by Japanese architect Arata Isozaki, Peggy Guggenheim’s Palazzo Venier dei Leoni in Venice, and more recently, a collaboration with Deutsche Bank for the Unter den Linden project in Berlin. There is also an unrevealed design by Austrian architect Hans Hollein for a museum in the valley of Salzburg.

In February of last year, Architecture magazine reported on Gehry’s $850 million project for a Guggenheim that would float above four piers on the east side of Manhattan. The project includes “a library, educational facilities, a theater, a skating rink, and a public park.” This reflects the ongoing mission of the museum—not only as an exhibition space, but also as an educational institution and an urban attraction.

If traditional museums served to enhance the beauty of the city with their solemn stillness, the new art spaces tend instead to flow with their surrounding environments. Gehry’s Guggenheim rises like a fish-tail tower embracing a main thoroughfare bridge and a public plaza, with Jeff Koons’ puppy sculpture facing back toward the city’s business center. The new gallery in Warsaw, designed by London architects Adam Caruso and Peter St. John, adapts its massing and visual continuity to the surrounding context while also reinterpreting local Victorian architecture (canal-side houses, patterned tiles, grand halls) as it exists.

In 1998, Blueprint, the British magazine of architecture and contemporary culture, posed the question of whether Helsinki would become another Bilbao when Kiasma, Finland’s contemporary art museum, integrated itself into the city while drawing the natural landscape as its backdrop. Designed by Steven Holl, the building

is strongly connected to its site and conveys a greater sense of locality than Gehry’s work. Its valley-like setting, with pools of water and intersecting roads weaving through building clusters leading to Toolo Bay, creates a charming balance of scales. Art mediates the transparency and lightness of glass, resembling inverted blocks of ice, evoking a sensual impression of Nordic art and craft.

What gives these cities their distinction is not the newly established institutions nor the valuable collections, but the cities themselves. Museums have become symbols and magnets of prosperity in the post-industrial era. Rem Koolhaas is consistently associated with major urban development projects. He once offered a sharp analysis of New York in his book Delirious New York and, more recently, has taken part in the development of China’s vast Pearl River Delta project, along with numerous other large-scale urban plans. His office, however, is based in Rotterdam—a city defined by commerce, infrastructure, and a certain independence from history, setting it apart from other European cities. From OMA’s perspective, architecture is the integration of program, material, and the ability to create what has not yet been seen.

While Gehry’s Guggenheim appears striking, almost as a symbol of the Cyber-baroque era, within a quiet context, Koolhaas and OMA’s Kunsthal rises amid the dense bustle of Rotterdam, making it difficult to discern where the city ends and the museum begins. You might jog or rollerblade along the ramp cutting through the heart of the Kunsthal, experiencing the artworks and gallery activities along both sides, above and below, without passing through internal security systems. The interior surfaces are interconnected, resembling a network inside a storage-box-like warehouse. Whether you are driving on the elevated road, delivering goods on the lower street, or playing in the outdoor park, your eye will inevitably catch a part of the Kunsthal from any direction, like a directional sign or an advertisement.

Architects’ obsession with the “new” can cause discomfort for others. Contemporary modern architecture, such as Richard Meier’s building complexes and Norman Foster’s futuristic designs, presents itself as a predictor of a clean, polished future. Even the Guggenheim Bilbao relied on the CATIA computer program—such a project could not have been realized in earlier times. While Bilbao achieved overwhelming success, other cities must think carefully before attempting Gehry’s audacious work. It is understood that Gehry is an artist—his ability is unique and cannot be imitated.

The novelty of MACBA in Barcelona, the depth of Kunsthandwerk in Frankfurt, the High Museum in Atlanta, and the grandeur of the Getty in L.A.—in truth, all represent a reinvention of Le Corbusier’s forms from the 1920s. Having a fresh appearance does not necessarily make them truly new; it may be merely a symbol of newness, or the unclear idea of someone.

Another city emerging on the global contemporary art scene is the quiet and beautiful Santiago de Compostela. Much has happened in this old city: when the four provinces of Galicia united as a postFranco autonomous region, Santiago was awakened to serve as the capital, accompanied by planning for a new urban identity, including landmark buildings. One of the most beautiful urban development projects in this new city is the Galician Centre of Contemporary Art (cGAC), designed by the master Portuguese architect Álvaro Siza Vieira. Located in a valley, it offers views of both the city’s stonebuilt landscape and the surrounding natural beauty. The entrance features a canopy that provides shade and shelter while offering

glimpses of the artworks inside to draw attention from the exterior. Both Meier’s and Siza’s museums are architectural masterpieces, yet in Siza’s work, it is uncertain where the old ends and the new begins.

Traditionally, museums were used to preserve works of art. But in today’s new world, art is created to preserve museums, to decorate architecture, and to tease and play with audiences. The Groninger Museum in the northeast of the Netherlands is uniquely special in that several renowned design offices collaborated to create a masterpiece of architecture. The pavilion for the paintings of master artists was conceived and designed by Coop Himmelblau.

Such ambition separates the museum from the typical visitor experience. The museum becomes a Disneyland with explanatory labels, reinterpretations of Corbusier by Meier, high-tech complexity, and deconstructivism in the gaps between avant-garde culture and the remaining visible elements. The meticulous forms of modern architecture elevate the museum to another level—not as a filter for chaotic reality, but as a stratifying object: high culture, the senior authority.

If Getty is the Acropolis of the present and MoMA represents the visual arts culture of St. Peter, there are still many galleries that prefer adapting existing spaces for exhibitions. Observing numerous contemporary projects, and from the perspective of many contemporary artists, transforming an existing space can create a more compelling atmosphere than constructing a new building. The old factory that became the Saatchi Collection in London, the police parking garage that became Temporary Contemporary in LA, or the old school in Long Island that became P.S.1—all represent daring alternatives to mainstream architectural practices. Both old and new projects of this kind rarely address architecture per se; in fact, there is no need for embellishment when space and atmosphere mutually support one another while remaining autonomous.

Young artists of the 21st century understand well that life has pleasures beyond ornamentation or excessive refinement.

In 1986, Jan Hoet’s Ghent Museum of Contemporary Art organized Chambres d’Amis, bringing prominent artists such as Joseph Kosuth, Giulio Paolini, and Mario Merz to exhibit works in local homes. The city’s residents thus became part of the art itself, breaking down the barriers between the public and the gallery, and embracing new ideas that arise every day. Artangel in London has applied a similar approach, both in the Queen’s House near Greenwich (artist Tatsuo Miyajima) and in warehouses near Wembley (artists Eno & Co and RCA students).

A key distinction between galleries and museums lies in the museum’s focus on collecting and preserving art, a matter of conservation. Museums resemble banks, with strong financial bases, an institutional image, and a closed-off aura that is difficult for the general public to access.

In a context where most museums are overcrowded, with people packed into shops, cafés, and restrooms, many institutions are seeking open-air locations, escaping the crowds and reconnecting with nature. In the north of Cologne, the Insel Hombroich Museum aims to integrate art with the ecosystem. It is a stylish museum, simple and sincere in the German manner, located within a riverside park, featuring several small pavilions for artworks from various sources (Europe and Asia, both contemporary and historical). The project exudes a relaxed atmosphere.

Opposite Insel Hombroich lies a fallow field, now purchased for an additional project, with several internationally renowned architects involved in the master plan (Alvaro Siza, Tadao Ando, Claudio Silvestrin). This architectural initiative has been supported both by gallery owners and by criticism, notably Brian Doherty’s The White Cube over 20 years ago.

However, Siza’s work possesses a depth that goes beyond what appears in photographs. The architecture in Santiago is almost imperceptible—it is a dazzling play of subtlety. Casa de Serralves, Siza’s work in Porto where he lives, features entrances and interior designs that can be interpreted in multiple ways. This seems aligned with the intention of Rudi Fuchs, director of the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, who specifically commissioned Siza to design the museum’s new extension. Fuchs sought architecture that is simple, modest, and humble, distinct from the sleek, stylish, and futuristic work of Japanese architect Kisho Kurokawa at the neighboring Van Gogh Museum. If Koolhaas is a brilliant genius skilled at everything, Siza is calm, reserved, and less inclined toward modern technology. His work engages with light and the landscape—key factors in creating architectural beauty. His designs feature geometric forms and appear contemporary, yet they are also full of life.

Art hardly requires those flamboyant architectures at all. Donald Judd, both a sharp-tongued critic and a gentle mediator, moved himself from the competitive environment of New York City to the remote lands of Marfa. He spent over 20 years acquiring several old warehouses (mostly former military armories) and exhibiting his own and others’ sculptural works in extreme ways—through the choice of location, the sequence of arrangement, and the manipulation of light. Today, Marfa functions almost like a sacred land that curators and architects from around the world feel compelled to visit.

Such seclusion arises from a desire to distance art from the management systems of major city galleries. The successes of works like Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty in Utah, Michael Heizer’s Double Negative in Nevada, and Walter de Maria’s Lightning Field in New Mexico illustrate this. Artists entered a cycle of independent initiative. James Turrell called on American artists to escape urban society and work in the countryside. Artists such as Christo or Richard Long might occasionally approach galleries for exhibitions or funding. Accordingly, contemporary museums must engage with these artworks and allocate budgets for art located far from urban centers.

The feedback of art on contexts shaped by long-standing traditions has generated a number of interesting challenges for museums. In fact, the history of the 20th century has already shown that true artists often evade, resist, and even subvert the institutional contexts they belong to—or, as Koolhaas puts it, “fuck context.”

Many land art projects have been realized through private support, particularly from the Dia Foundation, headquartered in New York’s Chelsea district (www.diacenter.org). Dia planned to acquire the Nabisco box factory in the Hudson Valley area near Beacon. Experiencing land art requires careful planning and travel, and such artists need vast spaces. Yet we can document their work and present it through existing technology. While museums cannot always bring you to the artwork, they can bring the artwork to you.

Technology that museums rely on involves lighting, as well as the control of temperature and humidity, along with security. In the early 1970s, Richard Rogers and Renzo Piano created a marvel with the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris. Piano’s later galleries,

whether the Menil in Houston, the Beyeler Foundation near Basel, or the Centre Culturel Tjibaou on New Caledonia (www.adck.nc), advanced toward a harmony of scientific knowledge in construction, elegance, and design attentive to efficient energy use. These museums did not deplete resources like the major architectural monuments of the past.

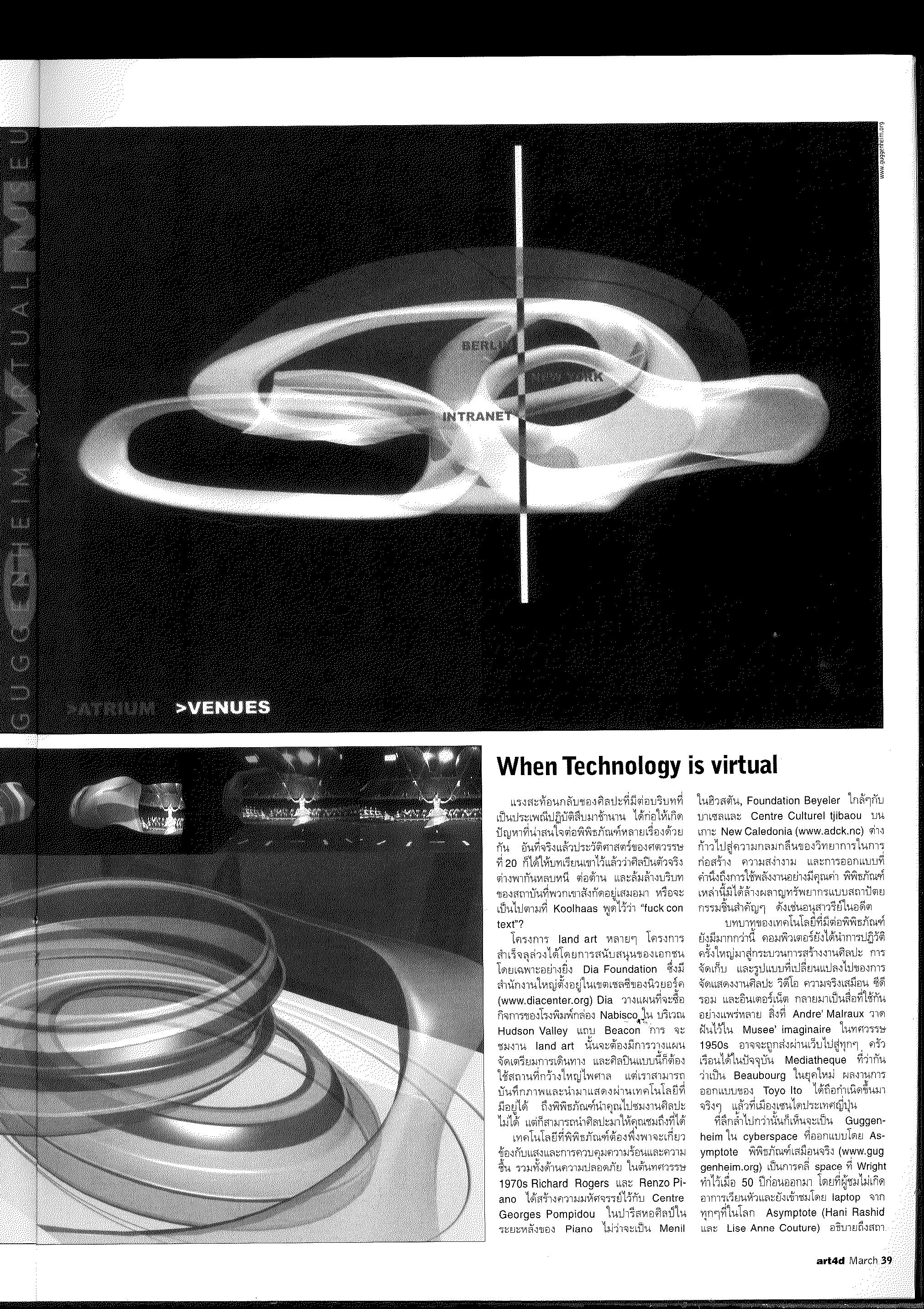

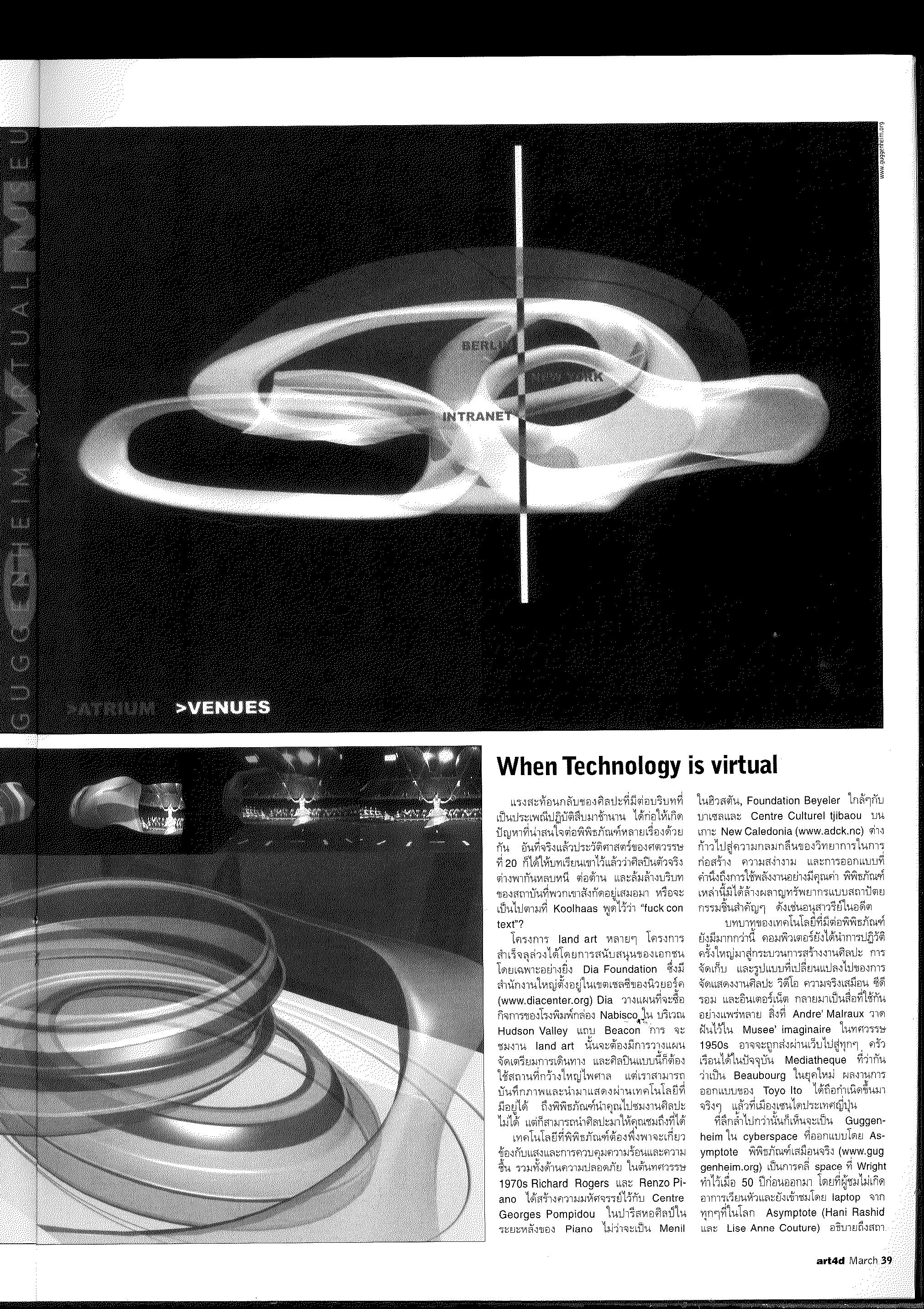

The role of technology in museums extends further. Computers have brought a major revolution to the processes of creating, storing, and presenting art. Video, virtual reality, CD-ROMs, and the Internet have become widely used media. What André Malraux envisioned in the Musée imaginaire in the 1950s can now be delivered via the web to every household. The mediatheque, said to be the Beaubourg of the modern era, has truly emerged in the design work of Toyo Ito in Sendai, Japan.

Even more futuristic is the Guggenheim in cyberspace, designed by Asymptote. The virtual museum (www.guggenheim.org) unfolds the spatial concepts that Wright developed 50 years ago, allowing visitors to explore without feeling dizzy and to access it from a laptop anywhere in the world. Asymptote (Hani Rashid and Lise Anne Couture) describe their architecture as “Liquidity, flux and mutability predicted on technological advances.” You simply log on and navigate effortlessly through the Internet. While technology guides us toward complex information and a placeless experience, the question arises: Is there an alternative that can create a humanistic sense and a genuine perception of place?

By the late 20th century, Tate Modern may offer a good answer. Architects Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron, who had collaborated with artists for nearly 20 years, began by looking to the past— the former power station designed by Gilbert Scott, which conveys a sense of historicity and permanence—and integrating it into the city. Tate Modern offers expansive, tranquil exhibition spaces with a striking interplay of natural and artificial light. These elements continually provoke new discourse, presenting a challenge for the museum and England’s emerging artists to consider how best to respond to the unfolding newness.

Raymond Ryan’s article provides an overview and highlights the increasingly diverse and changing factors in the creation, design, and operation of art museums over the past decades and at the end of the century. Although all the case studies are Western art museums, from the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, whose architecture functions as a work of art, to art museums in the virtual world of the Internet, it demonstrates that the “spirit” of an art museum arises from many elements and is constantly evolving.

In Thailand, we must first understand that building an art museum is not intended to attract tourists or accommodate artists’ works, as many tend to assume. An art museum should have fundamental functions and roles no different from a sports center or stadium, only with a different value: fostering mental subtlety instead of physical strength. From an architectural perspective, an art museum is not “just anything” judged by its façade, as some architecture students or architects who have never experienced a museum might think. The architecture of art museums has consistently influenced contemporary architectural thinking for architects.

For those interested in contemporary art and architecture, it is therefore fascinating to follow the changes that art museum architecture will undergo in the coming decade.

This publication is a reprint of the article originally published in art4d magazine, Issue 69 (March 2001), reproduced here with permission.

Editor in Chief

Mongkon Ponganutree

Managing Editor

Pratarn Teeratada

Art Editor

Krissana Tanatanit

Photographic Editor

Somkid Paimpiyachat

Oranut Paimpiyachat

English Editor

Leroy Sylk

Art Assistant

Sarawut Charoennimuang

Piyapong Bhumichitra