would like to thank our sponsors...

Thieman Family

Wang Family

Schoebel Family

Cheung Family

Tung Family

Ginwalla Family

Telyaz Family

Weiner Family

Lee Family

Salvatierra Family

Wainwright Family

Bharat Family

Cho Family

Dogan Family

Scott Joachim

Steele Family

Liu Family

Pashalidis Family

Junowicz Family

Jonathan Levav

Kivett Family

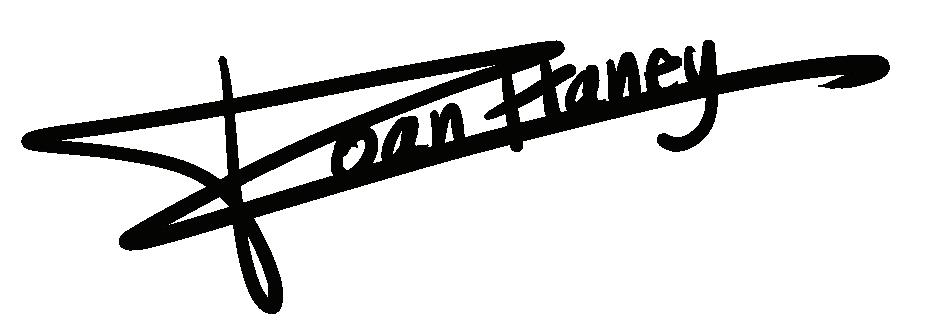

Editors-in-Chief

Claire Cho, Ethan Wang, Roan Haney, Emil Bothe

Creative Director

Nathan Lee

Photo Editor Lucas Tung

Business Manager

Sarah Thieman

Copy Editor

Scarlett Frick

Head Columnist

Tyler Cheung

Social Media Manager

Amanda Goody

Online Editors-In-Chief

Arjun Bharat, Luke Joachim

Staff Writers

Adi Weiner, Elena Salvatierra, Dylan Robinson, Isaac Telyaz, Evin Steele, Jonathan Yuan, Natalya Kaposhilin, Zoe Pashalidis, Malcolm Ginwalla, Max Merkel, Jake Liu, Elif Dogan, Carter Burnett, Ben Levav, Finn Schoebel

Adviser

Brian Wilson

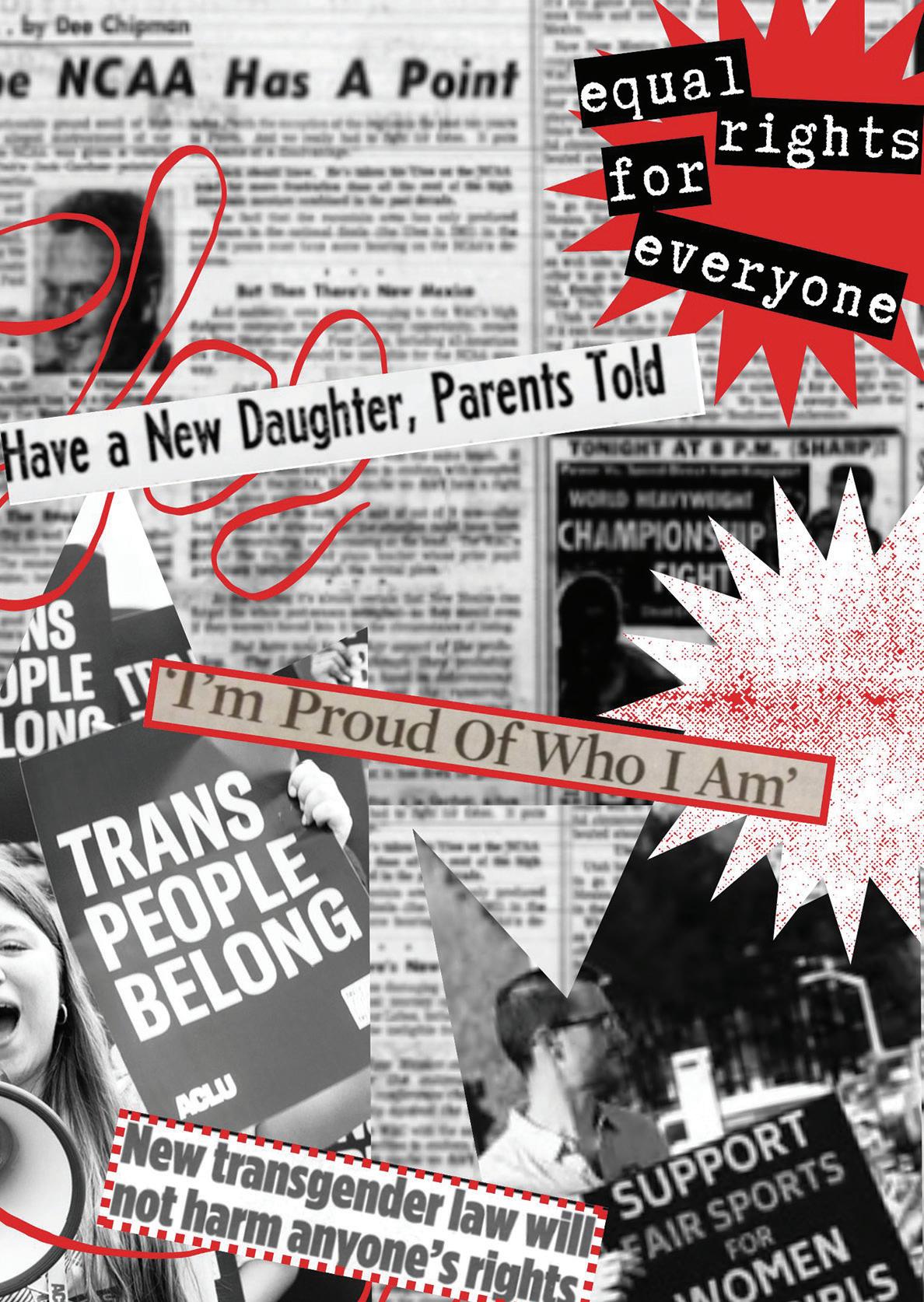

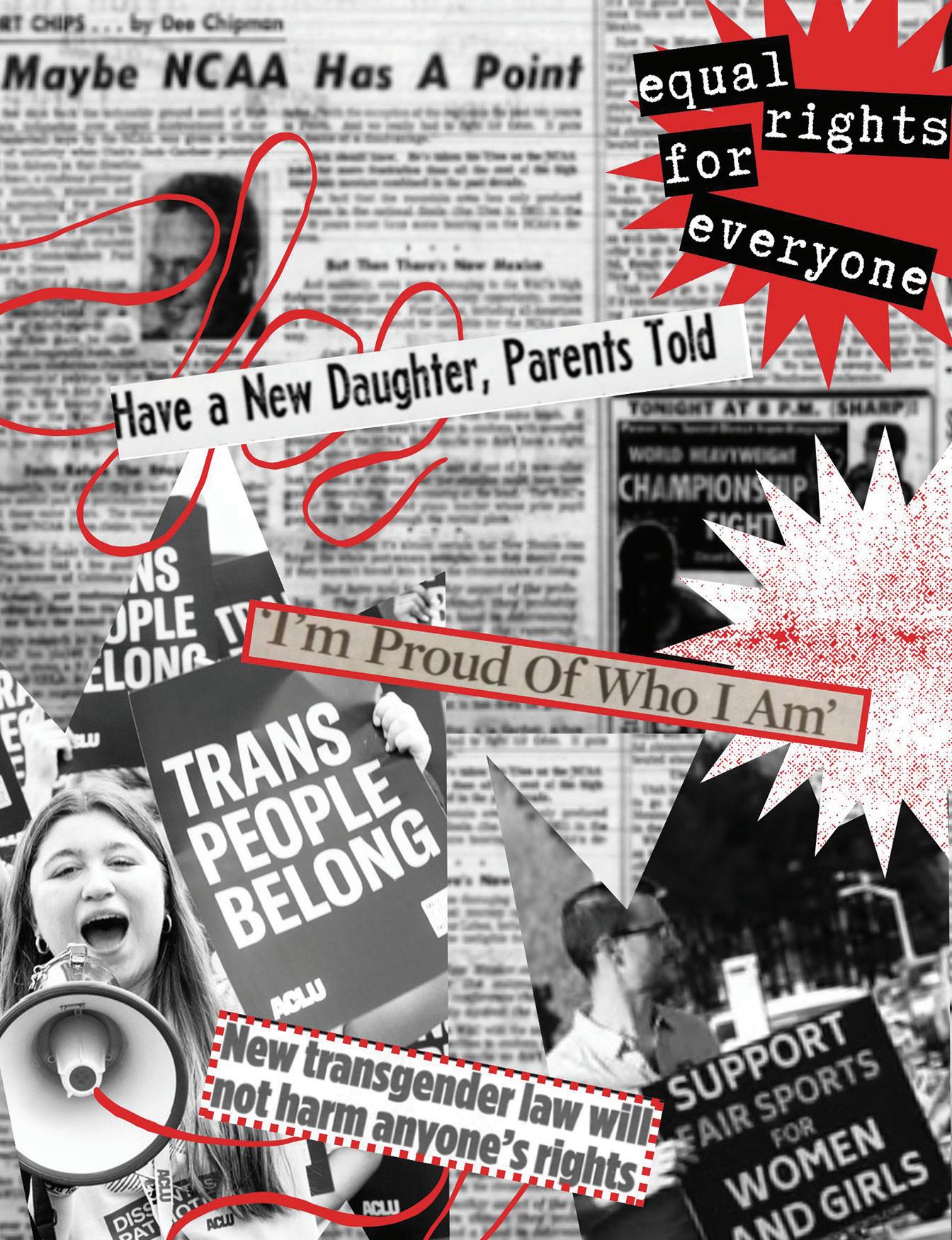

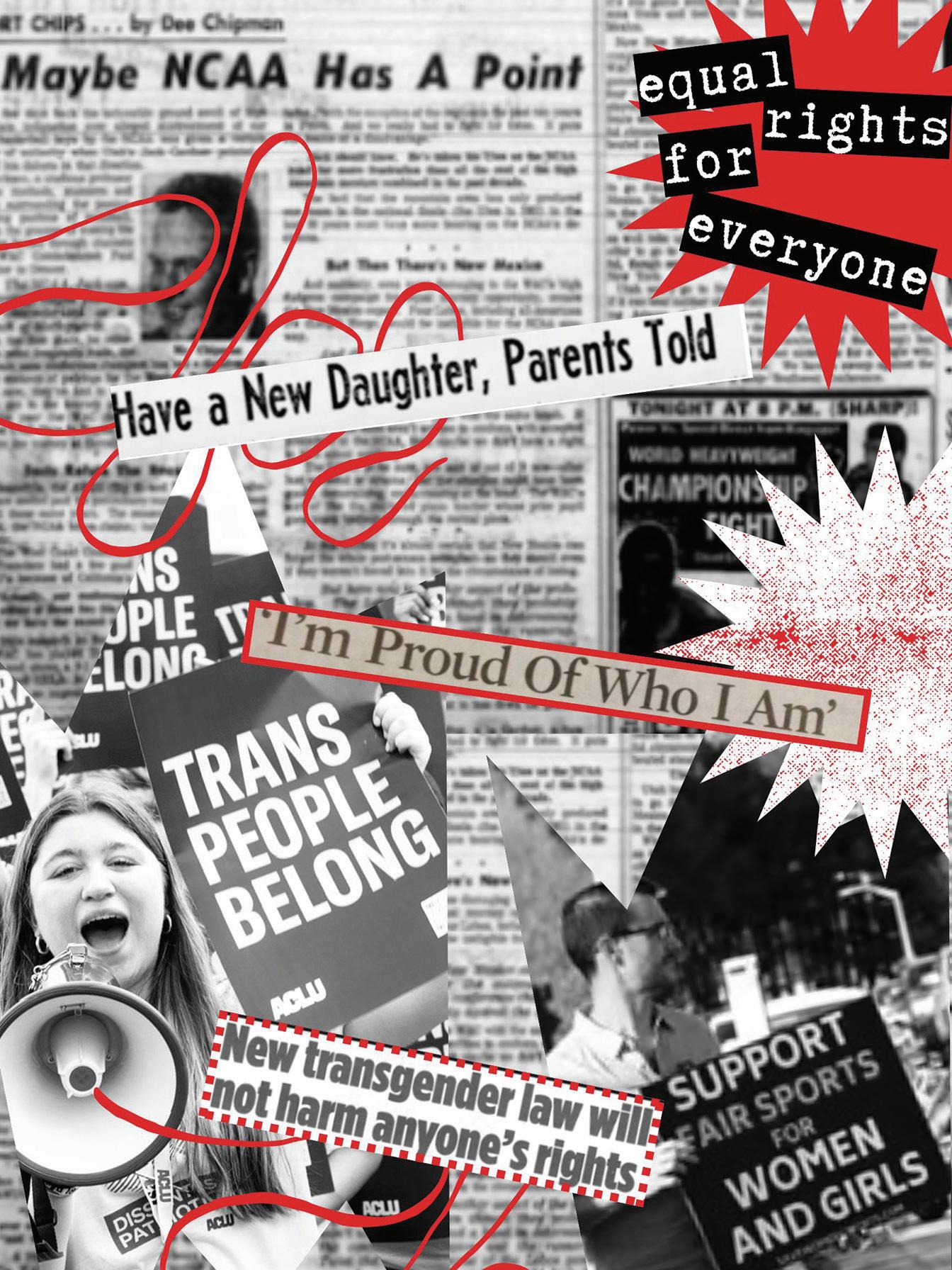

This cover features newspaper scraps in the silhouette of a head. This feature story on the transgender athlete debate can be read on page 38.

Hey Vikes! With Winter sports wrapping up and Spring sports in full swing, continue to check our website, Twitter, and Instagram for score updates and game recaps. We hope you enjoy our fourth print issue of Viking for the 24-25 school year!

Our cover story, “Transforming the Game” (page 24) discusses both sides of the debate of fairness and policy for the participation of transgender athletes in sports.

“Favorite Paly Icons,” (page 12) puts the spotlight on Paly alumni athletes who are inspirations for current Paly athletes.

High school practices vary from 7:00 am to 7:30 pm, and “Early Bird Night Owl,” (page 14) identifies what Paly athletes prefer.

cusses the transition of college soccer from traditional foundations to professional-style play.

Many athletes don’t have 20/20 vision, and “Beyond the Blur,” (page 19) unveils their difficulties and experiences.

“The War on Turf,” (page 22) recognizes the the pros and cons of artificial turf becoming the standard field at most Bay Area high schools.

“Plate of Pressure,” (page 24) reveals the effects of eating disorders on both people’s physical and mental health as athletes.

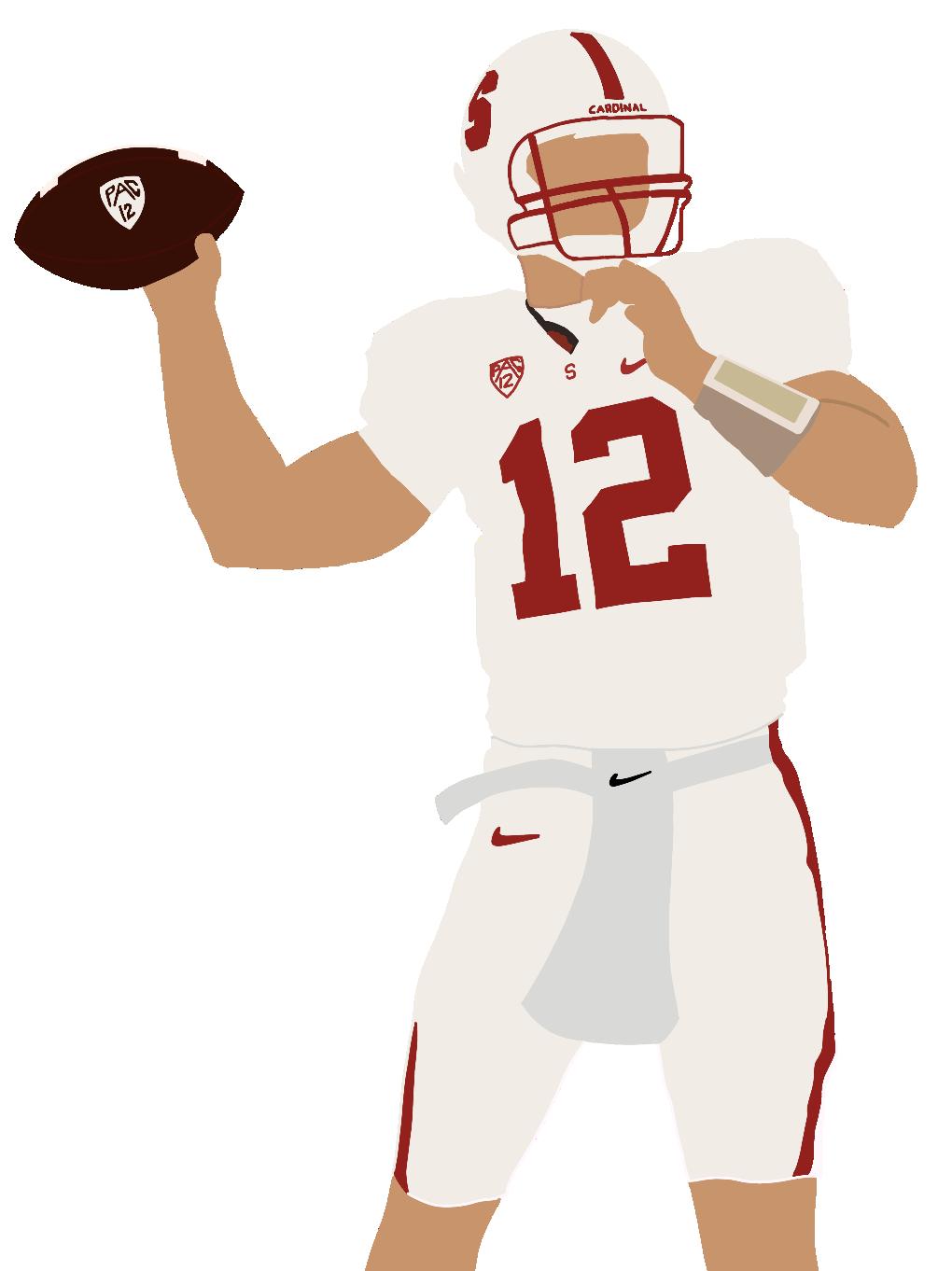

Once considered the face of Stanford football, “Luck’s Legacy” (page 28) dives into Andrew Luck’s return to his alma mater, as general manager.

most– a product of confidence and discipline.

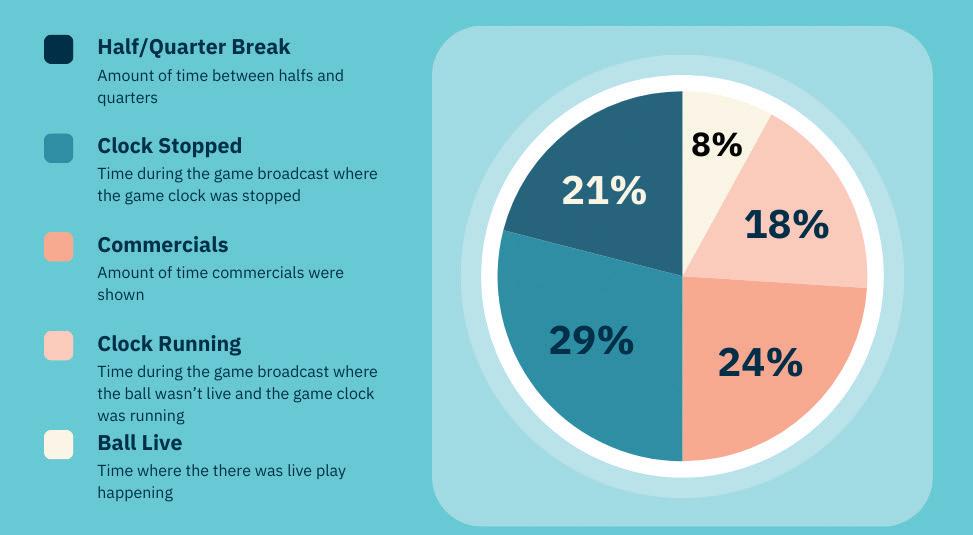

Each sport has a different proportion for actual play time in relation to the overall game time, and “Minutes that Matter,” (page 34) highlights the reality of playtime in varying sports.

“Cold-blooded Competition,” (page 36) focuses on Paly students who dedicate their weekends to skiing competitively.

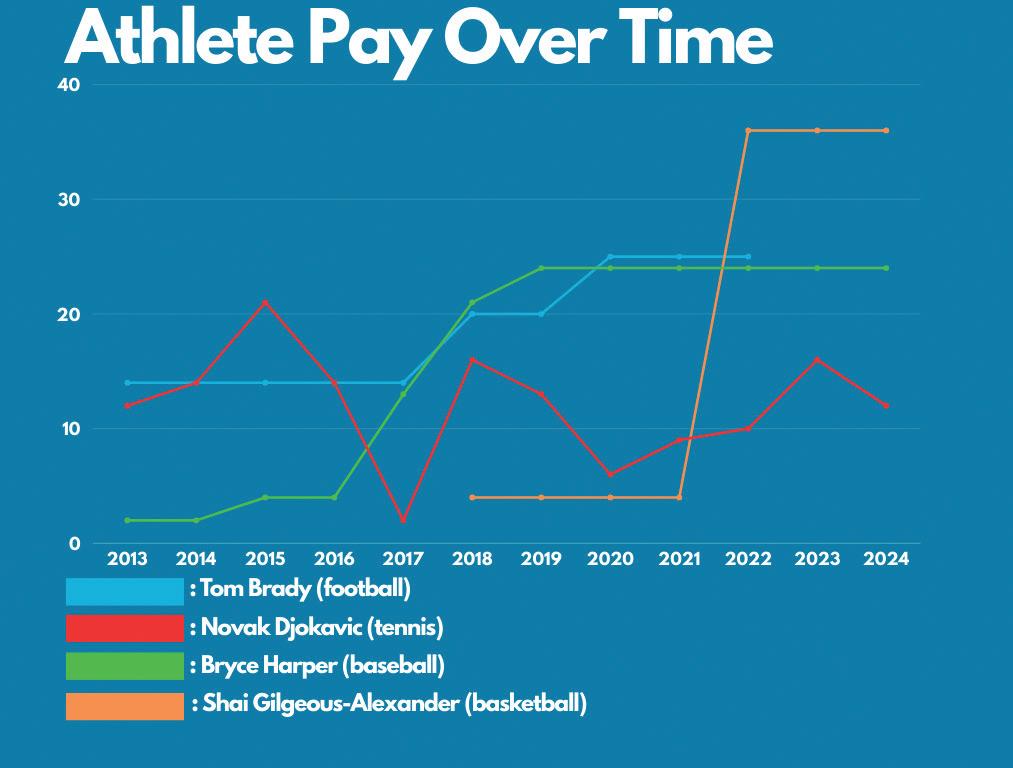

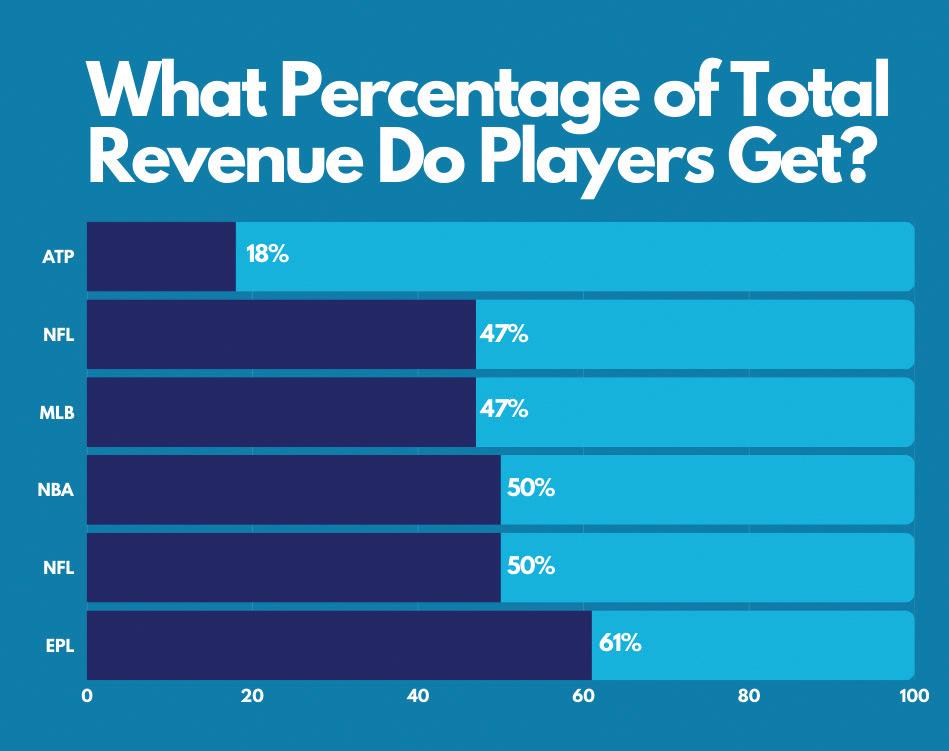

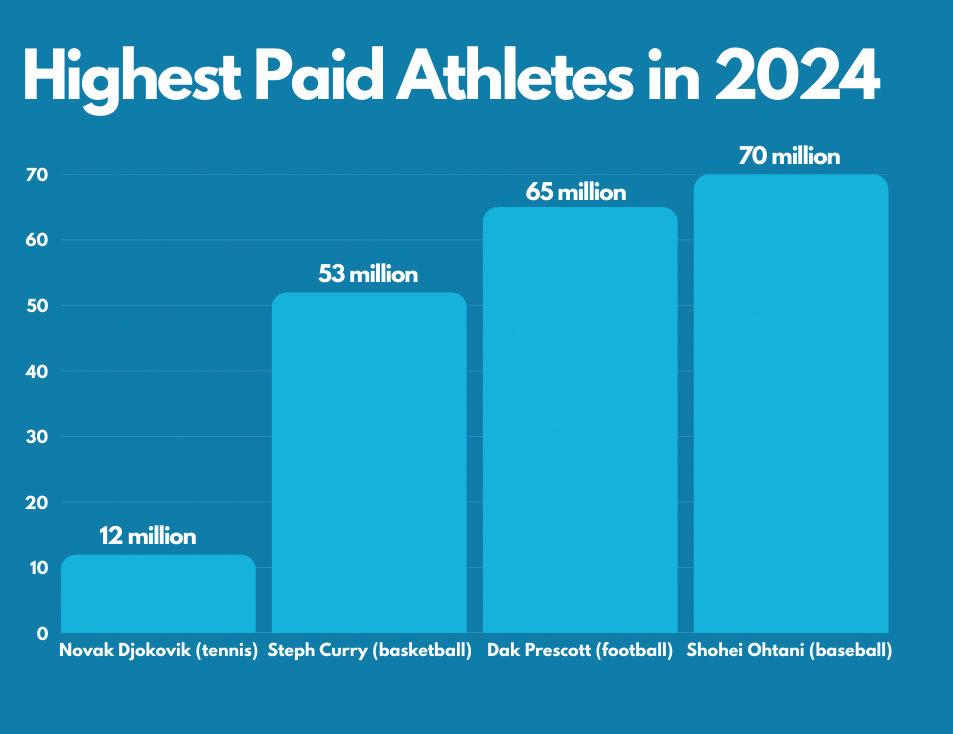

Finally, our final word, written by Tyler Cheung, explores the issue of financial insecurity prevalent in the professional tennis world.

“Professional Pivot,” (page 16) dis-

“The Clutch Factor” (page 30) identifies the skill of clutching when it matters

Roan Haney

That’s all for the fourth issue of this school year! This is our final issue as the editors of Viking as we hand the reigns to our new team. Hope you all have enjoyed what we’ve produced this year!

Emil Bothe

As the 2025 NCAA Men’s March Madness tournament progresses, there is one striking difference that sets this year apart from previous ones: the low-seeded powerhouse teams are winning everything. Unlike past tournaments filled with shocking upsets and underdog stories, many of the lower-seed teams are plowing through the tournament with ease. Every single one-seed advanced to the Final Four, leaving no room for the usual “Cinderella stories” that have come to define the spirit of March Madness.

The one defining factor that is most likely the cause of these results: name, image, and likeness (NIL). The Supreme Court’s decision in NCAA vs Alston allows college athletes to profit through brand deals, commercials, and sponsorships. While the concept of NIL is beneficial for player equity, the current reality is the slow dismantling of college basketball.

In the past, the recruitment process was a highly personal matter, typically involving face-to-face interactions, direct relationships, and a deep understanding of an athlete’s character and potential. Furthermore, players often chose less pres-

tigious basketball programs in order to receive more playing time and therefore develop more quickly as a player. For example, in 2006, Steph Curry was offered to play basketball at Virginia Tech, following in his father’s footsteps. Instead he opted to play at Davidson College, where he was promised more playing time. This decision proved beneficial, as following his three years at Davidson Curry was selected with the 7th pick in the 2009 NBA Draft.

With the introduction of NIL into collegiate sports, the financial upside of joining a well-established program is too great to ignore. Powerhouse basketball schools typically have the most lucrative budgets, leading to most highly recruited players signing with the same small cluster of colleges.

Another key issue is that high-performing players from lesser-known schools often transfer to more prestigious programs after showcasing their talent. This reduces the number of highly recruited players who attend lower mid-major colleges for multiple years. All the talent is being pulled up from the mid-major colleges and thrown into powerhouse

programs, further widening the gap between elite programs and the rest of college basketball.

Navigating and implementing the necessary regulations for a change as significant as NIL takes time for any sports league. One possible solution to restore the balance in college basketball is to provide more NIL opportunities to mid-major colleges. If these colleges have greater access to financial resources, they can attract high-profile recruits, allowing them to be competitive. This would encourage players to consider schools outside the powerhouses, redistributing the talent more evenly. Alternatively, an NIL cap could be put in place, similar to how salary caps function in professional leagues. This cap could limit powerhouse schools from monopolising the top recruits.

All and all, the excitement of March Madness has always thrived on the unpredictability of lower seeds. The new NIL rules jeopardize the integrity of this tournament, and the NCAA must implement guidelines that ensure mid-major colleges have a fair chance while competing against dominant programs.

Leo Terman (‘25) hits a powerful backhand during a 1-6 loss to Homestead. 3/18/25

Photo by Lucas Tung

Zoe Quintana (‘27) runs past a falling defender during a 7-13 loss to Los Altos 3/26/25

David Lian (‘28) stretches out to return a tricky shot in a 22-8 victory versus Homestead.

3/25/25

Photo by Lucas Tung

by NATALYA KAPOSHILIN, SHO NEWMAN, and PETER REVENAUGH

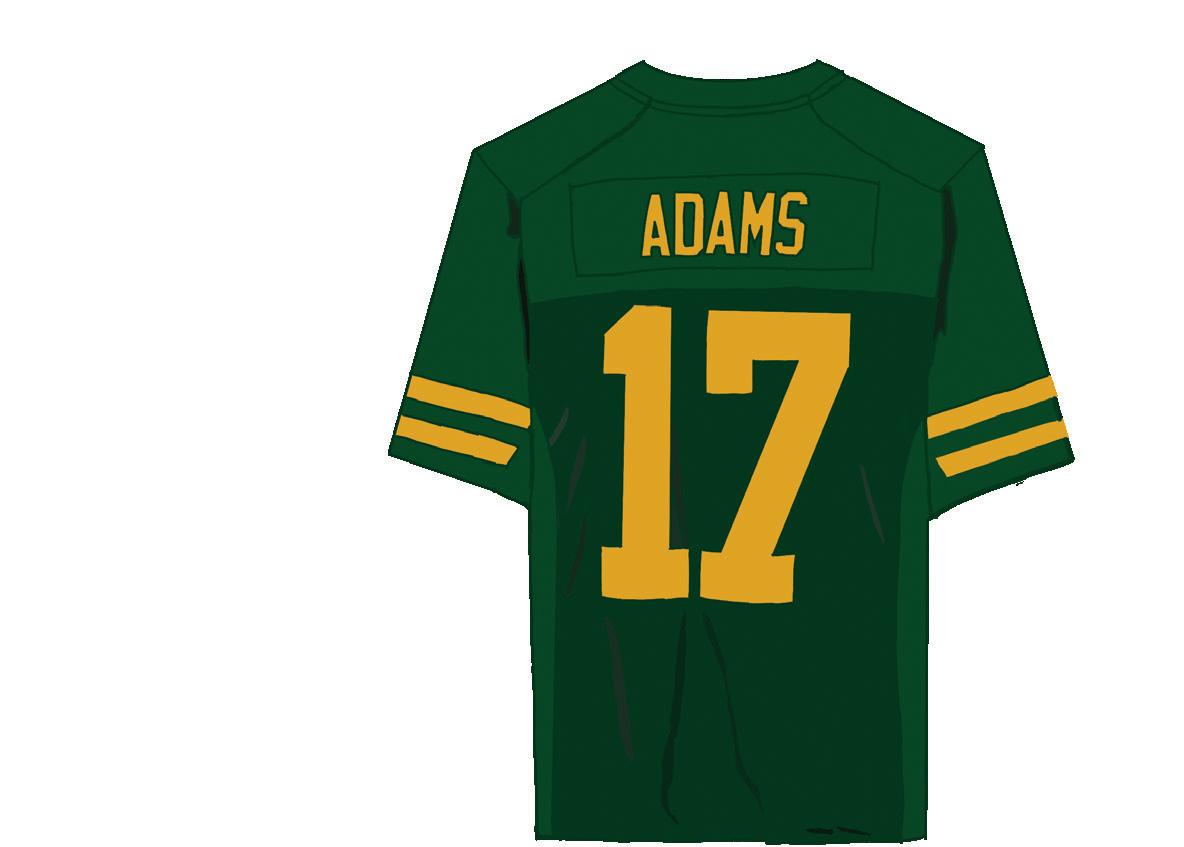

Paly alumni Davante Adams, Jeremy Lin, and Joc Pederson have had great achievements in pro leagues. These three stars have inspired Paly students on various levels, so we asked Paly students which alumni they look up to the most.

A Palo Alto High School graduate who now plays in the NFL as a wide receiver for the Las Vegas Raiders. He has 6 Pro Bowl appearances in his ca reer.

A Major League Baseball player who played for the Los Angeles Dodgers, Chicago Cubs, Atlanta

The Paly grad who is now a Major League Baseball player, previousley playing for the Los Angeles Dodgers, Chicago Cubs, Atlanta Braves, and San Francisco Giants.

Photos Courtesy of Karen Ambrose Hickey

In terms of Paly graduates, I think the only professional athletet that comes to mind is probably Davante Adams. Although I don‘t nessearly look up to him I think it’s really inspiring to know that in such an academically focused school, Davante Adams was able make it to the highest level of his sport from Paly.

“ ” Willem Madem (‘27)

Jeremy Lin has been a big inspiration of mine since I was younger. Seeing an Asian American athlete from Palo Alto like myself achieve success at the highest level of basketball proved that athletes that come from different backgrounds can make it and break different kinds of stereotypes along the way.

Meera Signh (‘26) “ ” “ ”

I really look up to Joc because I find it amazing that someone who stood next to the same home plate in the same stadium, won a World Series. It makes me feel like I could do the same some day.

High school sport practices can vary in time from one sport to another. From early mornings to late nights, which do students prefer more?

by NATALYA KAPOSHILIN, SHO NEWMAN, and PETER REVENAUGH

“Practices before school allows for more free time after school. Also for sports that need to share a field between JV and Varsity like baseball one team could practice before school and the other after.”

“I prefer to do both. In the morning I’ll focus on doing something light, a run, yoga, or technique session, so that after school I can get my body right to work hard and condition to the best of my ability.”

“I do sometimes like having morning practice because we end school so late now sometimes practice doesn’t end until 7:30, so its nice having morning practice so we are done after school. Overall I prefer after school practice though.”

“I prefer after school practice because I can get full sleep and I don’t like waking up early. I’m more focused after school when I’ve been awake for a while and my body feels the same way.”

by NATALYA KAPOSHILIN, SHO NEWMAN, and PETER REVENAUGH

Natalie Dymmel (‘26) is committed to play Division 1 lacrosse at Radford University, and has a particular eating schedule on game days to help her dial in nutrition and performance. We followed her on game day to see what she eats from morning to post-game.

EARLY SNACK

BREAKFAST

SNACK LUNCH

PRE-GAME

GAME TIME

POST-GAME

Protein Shake w/ BCAAs, creatine and vitamins

Two whole eggs and one egg white (salt & pepper for seasoning), banana & strawberry fruit salad (sometimes grapes or other fruits), and a bagel and cream cheese depending on needs

Organic fruit bar & Apple sauce

Typically pulled chicken with barbecue seasoning (otherwise plain grilled chicken), white rice, fibers can include carrots or fruit, prepare second protein shake for afternoon classes

Turkey and cheese sandwich & Protein chocolate milk

Water w/ Jocko Hydrate or LMNT electrolytes

Smaller serving of steak/meat, finish w/ Fruit bowl for the sweet tooth

n its present form, college soccer compresses the bulk of its competitive schedule into the fall, with some spring matches permitted. This structure means teams might play two or more games per week, often with significant travel across states and coasts. According to Matt Frank, balancing training with consistent travel was not just a logistical challenge but a physical one.

“When I was playing, we’d most often have

“For college soccer to remain relevant, maybe bridging the gap is the way forward.”

–Matt Frank

matches on Thursdays and Sundays. That means Friday is basically a recovery day and Saturday is a short session. Then it’s a quick turnaround on Sunday, and by Monday you’re already recovering again. Tuesday you’re preparing for another Thursday match. It’s a cycle that can be extremely difficult to maintain.” For Frank, the condensed schedule leaves little space for truly meaningful training. In the professional world, players usually have a full week to digest the previous match, isolate areas for improvement in practice, and gradually taper back up before the next competitive fixture. College athletes, however, often find themselves in a perpetual state of recovery. Add rigorous coursework and the swirling social demands of campus life, and it’s no wonder that injuries and mental fatigue can mount quickly. Matt Biggam, who played goalkeeper at Santa Clara University, echoes these sentiments. He recalls team members pushing through the exhaustion of two games per

By CLAIRE CHO and BEN LEVAV

ple games a week, you have more energy and time to focus on your gameplay. So yes I do believe it will be more competitive, girls won’t be as worried of injuries so it will become more intense and better training will most likely just lead to creating better players.

When bodies are under constant stress, there’s not just a risk of physical injury but also a compromise of performance. Biggam’s perspective underscores the need for a schedule that allows proper rest and structured development—something many proponents of a more professional-style model highlight.

“I believe the current schedule is harmful to player recovery. Playing two games a week plus training is very difficult on the body. On my college team, multiple players got injured because we did not get

Paly Senior and Pepperdine Women’s Soccer commit Kaitlin Lowry shares her thoughts on the new format as

“I think the pro-style layout will increase the intensity and competition at the college level. Right now, a lot of college players are having to deal with both practice everyday and rehab/recovery. If you take out the aspect of constant recovery due to the multi-

One of the loudest calls for changing college soccer’s format is the need for more games over a longer period—moving from a quick burst of 20 matches in a few months to a potential slate of 30 or 40 games spread throughout the academic year. Advocates argue that such an approach aligns better with professional leagues worldwide, where teams generally play once a week and devote the rest of their time to training, tactical preparation, and recovery. As Biggam explains, “I only see benefits from extending the college soccer season or making it yearround. This would increase the skills of all college soccer players and give them more game experience—which is very important for development. It would be closer to what a professional soccer player experiences, making the transition from college to professional much easier.”

A primary advantage of this approach is that players would have consistent opportunities to apply what they learn in training to real matches. College coaches could emphasize not just fitness but also the finer details of tactics, formations, and positional awareness. Instead of a mad dash from one game to the next, a more elongated schedule could incorporate dedicated blocks for skill work and scenario-based training—an environment where athletes can experiment, learn, and refine.

However, lengthening the soccer schedule inevitably raises questions about academics. College athletes are, after all, stu-

dents first—at least in theory. For many, the condensed fall format allows them to front-load or back-load challenging courses in the spring. Stretching out the season might eliminate that strategic scheduling advantage. If games are spread across two semesters (or three academic quarters), will players be perpetually on the road? Frank, who studied at Stanford, outlines a potential concern.

“You’ll maybe only play one game a week, so you’re not missing as many days at once, but you’ll miss classes, exams, office hours, and study periods throughout the entire year. You never really have that free quarter or semester to really focus on your studies. You’re tasked with performing as an athlete every week.”

This tension becomes sharper considering that many NCAA Division I programs frequently schedule distant non-conference matchups to boost their rankings or replicate tournament environments. A pro-style structure might reduce midweek matches, thus slashing travel on weekdays, yet it still might expand the total number of weekends dedicated to competition. For some institutions, that’s a worthwhile tradeoff. For others, with fewer resources or more demanding academic standards, it could prove daunting. Interestingly, Biggam found a strategy that worked under the old system.

“I balanced playing and being a college student by taking 12 units (four classes) during the season, which made it easier to manage playing and school.”

While that approach helped Biggam, it might not be univer-

“I only see benefits from extendting the college soccer season.” –Matt Biggam

College soccer is on the verge of a major shift, caught between longstanding foundations and forward-looking ambitions of professional-style play.

sal. A year-long season could require careful planning across both fall and spring semesters, without the luxury of parking harder courses entirely in the off-season. Critics of the professionalized model argue that it risks blurring the lines between amateurism and professional-level scheduling demands, ultimately squeezing the “student” part of “student-athlete.”

Under the current model, college soccer teams may squeeze 18-20 games into just a few months. Spring competition usually consists of friendlies or lower-stakes matches with strict NCAA regulations on training time. To players and coaches dreaming of a professional career, these limitations can feel like a barrier to true growth. Biggam believes the existing sys tem undercuts potential.

“No, the current schedule of 20 games is not enough for player development. Play ing two games a week is extremely chal lenging on your body as an athlete. I think they should extend the season to 30 or 40 games and play one game a week, much like the professional schedule.”

A weekly matchday, from Biggam’s per spective, is the sweet spot for develop ment. You gain the rhythm of regular com petition while still carving out the time required to hone individual skills, build team chemistry, and manage proper re covery.

“I am looking forward to the D1 soccer schedule over the high school one be cause the training can be more intense, and it allows time for healing, and more time to work on specific concepts with your coaches and teammates in between games,” Lowry said.

Many coaches echo this sentiment, es pecially those who see college soccer as a stepping stone to the professional ranks. If U.S. soccer aspires to cultivate home grown talent on par with European and South American systems, bridging the gap in match experience is crucial. Frank acknowledges that current college soccer can still produce elite athletes—countless alums have forged careers in Major League Soccer (MLS) or abroad—but the trajectory is narrowing.

Professional academies have begun offering robust training environments for younger players, often convincing them to bypass college entirely. As Frank notes.

“We’re seeing less and less of those big successes out of college. Now, with MLS Next, you have 15-, 16-, 17-year-olds who are getting high-level gameplay and might never go to college. They continue at that same level of training, while the college model right now has periods where you’re not competing or training as a team for months.”

The impetus behind an elongated season thus goes beyond simply replicating a pro schedule; it’s about preserving college soccer as a viable path for top-tier athletes. Without adaptation, the NCAA risks losing talent that seeks a steadier de

By CARTER BURNETT, ELIF DOGAN, ISAAC TELYAZ and JONATHAN YUAN

For athletes with vision issues, clear eyesight is crucial for peak performance. Every athlete, including those at Paly, has their own way of making sure their vision is at 100 percent.

The football spiraled towards Paly sophomore Jair Nucamendi, but this time, it was not just a brown blur; for the first time, his vision was clear and he was confident in catching the ball. For athletes with vision issues, glasses are not just an accessory — they are the key to victory. Wearing glasses or contacts gives visually impaired athletes an opportunity to elevate their game and play on the same baseline as their opponents. But for other athletes, glasses can feel clunky and get in the way of their ability to perform. Because of this, most people choose to use contacts instead.

Having clear vision as an athlete while performing during a game is essential. Factors such as reaction time, accuracy and depth perception are all affected by an athlete’s vision. Whether it’s a baseball player tracking a small and fast-moving pitch or a basketball player trying to make a precise shot, athletes heavily rely on clear eyesight.

Most athletes who have impaired vision choose to wear contacts because glasses have negative effects that can change an athlete’s ability to play. First is the issue of their fragility. According to a VisionFirst article, “High impact sports and glasses usually do not mix well; there are simply too many opportunities for your glasses to fall off your face or even cause an injury.” This would provide difficulties with

eyewear in sports such as football. Another negative impact of wearing glasses is the discomfort that can come with wearing them. Nucamendi, a football player whose transition from glasses to contacts was driven by a number of irritations, talks about how wearing glasses hindered his athletic performance before switching to contacts.

“Before I got my contacts, I wore glasses in every sport I played, which was troublesome at times,” Nucamendi said. “They would either slide down my face or fully fall off, so it was always a challenge. I would have to put them in my pockets or set them aside where they couldn’t be damaged.”

“In every sport I played, wearing glasses was a challenge because they would slip or fall off.”

to enhance his performance on the field. Contacts offer a practical solution to many athletes’ challenges when performing with glasses, eliminating distractions and allowing for greater focus during competition. Athletes are more likely to stay fully engaged in their games without the concern of glasses hindering their abilities. Nucamendi began wearing contacts to improve his football experience and stray away from his nearsightedness affecting his game.

—Jair Nucamendi (‘27)

Playing a sport like football requires a strong ability to see both near and far, making clear vision a necessity. Nucamendi also faced difficulties playing football due to his dependency on glasses or contacts.

Nucamendi serves as a prime example of an athlete who relies on contact lenses

“When I didn’t have my glasses or contacts, I had to play through it and hope for the best with partial vision,” Nucamendi said.

Another reason why most athletes prefer wearing contacts is because of the limited peripheral vision that comes with wearing glasses.

According to a Smart Vision Optometry article, “Athletes who wear glasses have limited peripheral vision because of the way the lenses are placed; limited peripheral vision could be the cause for a loss of a game or even the catalyst for a serious injury”. With limited peripherals, athletes are at a massive disadvantage. Other issues such as fogging up, slipping or discomfort makes contacts more preferable.

mance to levels that would have been impossible in his previously visually impaired state.

different sports use visor glasses to block sunlight, some common sports being baseball or golf.

“Being able to see more clearly has been a big part in improving my performance as an athlete.”

—Liam Li (‘26)

“There is a huge difference between wearing contacts versus not; being able to see everything more clearly has been a big part in improving my performance as an athlete,” Li said. Being an athlete means that you have to be prepared to play in troubling weather conditions, such rain or fog. If visually impared athletes do not have contacts readily available in these conditions, they could have consequences.

Sometimes athletes will wear goggles not for visual aid, but purely as protection from physical damage to their eyes. The most prominent example of this is seen in the six-time NBA champion, six-time most valuable player of the year, and nineteen-time NBA All-Star Kareem Abdul-Jabbar.

Abdul-Jabbar was notorious for wearing goggles in every game he played; he wore them strictly for protection, after suffering from corneal abrasion in 1974.

Even though people saw wearing goggles or glasses as annoying or obstructing their ability to play, Abdul-Jabbar brought a new perspective to wearing goggles, showing that they did not hinder his performance in the slightest.

These reasons are why the usage of eyewear for athletes is very uncommon, at Paly and on a broader spectrum. One such example of someone who was able to perform better with a clearer vision is NFL quarterback Jameis Winston.

Born with slightly blurry vision, Winston struggled to see things at a distance. Throughout his high school and college career, Winston played with his near-sighted vision. As a quarterback, Winston needed to be able to see his teammates clearly in order to throw accurate with his passes. After a few NFL seasons, he finally decided to look into his eyesight issue, eventually resolving it by having a LASIK eye surgery. According to a Sports Illustrated article, “[Winston] saw significant improvement after his eye surgery, now he can throw to receivers he sees as clear as day”.

Before getting the surgery, he threw a league-high 30 interceptions; after, he Winston reported an improved depth perception and experienced significantly sharper and more accurate vision.

Paly junior, fencer and football player Liam Li, who is near-sighted, has many thoughts about how wearing contacts has helped elevate his athletic perfor-

“When I am wearing contacts, I am not affected by tough conditions, but without them, it is definitely more difficult to see because it makes my already blurry vision even more blurry,” Li said.

Despite the clear advantages that contacts provide, glasses are still used in some circumstances. Not all types of glasses are used solely for clearer vision. When the weather is too sunny, athletes may consider using sunglasses to be able to get rid of glare and see better. Professional athletes in a variety of

With Abdul-Jappar’s adaptation, popularity of eyewear grew, with some notable players being Hakeem Olajuwan, James Worthy and Dwayne Wade. Though none of them wore them for as long or had as much success as Abdul-Jabbar, they all played over a hundred games wearing them, as they too saw the benefits that come with wearing goggles.

When watching a typical baseball game, one can usually find at least a couple of players who are wearing sunglasses, if not most of the players. The use of sunglasses, once seen as unnecessary as they distort the player’s vision, is now very popular at all levels of baseball due to their ability to reduce glare and protect the eyes from ultraviolet rays. Paly junior and

ofMaevaHerbert-Paz

varsity baseball pitcher Ian Johnston talks about the importance of wearing sunglasses.

“As a pitcher, wearing sunglasses is not necessary, but it allows me to see the batter more clearly when it is too sunny,” Johnston said. “I try to avoid wearing them unless the sun is directly in my eyes because the dark tint is kind of annoying.”

Sunglasses are also crucial for outfielders, as they need to track the ball out of the air. Wearing sunglasses not only helps them track the ball by eliminating glare, but it also allows players to look directly at the sun with a reduced risk of damage to their eyes. Paly junior and varsity baseball center-fielder Nate Robinson shares his experience with wearing sunglasses.

let rays. Paly junior and snowboarder Maeva Herbert-Paz talks about how wearing ski goggles is crucial when snowboarding.

without their imperfections, and swimmers may find that they come with aggravating downsides.

“I often get goggle tans and burns after wearing them for a long period of time,” Kirby said. “Additionally, I have been allergic to certain kinds of goggles in the past.”

“As a pitcher, wearing sunglasses is not necessary, but it allows me to see the batter more clearly when it is too sunny.”

—Ian Johnston (‘26)

“I did not fully grasp how important wearing goggles is when snowboarding, until one time my goggles fogged up so I had to go down without them,” Herbert-Paz said. “Due to the glare of the sun and snowflakes flying in my face, the faster I went, the harder it was to see, so I had to slowly slide down the mountain. After that, I understood how essential it is to wear goggles when snowboarding.”

Even though ski goggles are very helpful, they have their flaws. Herbert-Paz talks about some of the ways that ski goggles can have a negative impact.

Though the popular choice among athletes is to wear contacts while playing their sport, this may change in the future with advancements in sports glasses. These sports glasses will not only help with vision correction but also offer a wide range of benefits that can significantly enhance athletic performance.

According to a Co Eyewear article, what makes glasses that are designed specifically for sports special is that they are made with a variety of frame materials and different types of lenses. They also offer different designs specific to different types of sports, like a wraparound design for high-impact sports and anti-glare treatment for indoor sports. They have also worked to create budget-friendly options, with some of the cheaper pairs ranging from 30-80 dollars.

“When the sun is out, I need to wear sunglasses in the outfield because when I am not wearing sunglasses, I am not able to focus on the ball when it comes my way,” Robinson said.

Sunglasses are used in golf for the same purpose, protecting players from the sun and enhancing their vision of the field. However, goggles are not used as frequently in golf as in baseball. Paly junior and golfer Dylan Liao highlights his usage of glasses in his sport.

“I only wear sunglasses about once in every 10 games, specifically when the sun is blinding enough to hinder my performance,” Liao said. “If I didn’t wear glasses on sunny days, my stroke count would increase significantly as a result of worse vision.”

Glasses are also used in sports to protect people from getting physical objects in their eyes. One example includes the use of goggles for skiing and swimming to protect the user’s eyes from snowflakes and water.

Ski goggles not only prevent snow from going into the skier’s eyes, but protects their eyes from wind and harmful ultravio-

“Sometimes my goggles fog up, which can be very annoying because [depending on the weather conditions] I can’t take them off, and the fog makes it harder to see things like bumps, which can be very dangerous,” Herbert-Paz said.

Similarly, goggles are essential for swimming, significantly enhancing the swimmer’s underwater vision. Paly junior and swimmer Romy Kirby sheds light on the significance of wearing swimming goggles.

“If I didn’t have goggles, I would not be able to see and my eyes would become super irritated from the chlorine,” Kirby said. “I would not be able to perform underwater at the same level without goggles.”

However, goggles are

As sports eyewear continues to evolve, athletes may find that specialized glasses offer a more feasible alternative to contacts, providing both vision correction and enhanced performance benefits. Whether through contacts, glasses or even corrective surgeries like LASIK, clear vision remains crucial in an athlete’s ability to compete.

As artificial turf becomes standard at many Bay Area high schools, players and communities are weighing its consistency and low maintenance against concerns over safety and environmental impact.

Racing off his line, goalkeeper and Paly senior Jacob Kinsky glides across the turf, deflecting the shot with precision. As his teammates swarm in celebration, Kinsky glances down to see a fresh turf burn on his leg— but he shrugs it off. The save was worth the sting.

Synthetic turf has become extremely popular in the United States and is used at most high schools in the Bay Area, including Palo Alto High School. The artificial alternative to grass offers several benefits, such as increased durability and significantly less maintenance. Kinsky has grown up playing soccer for Palo Alto Soccer Club, which uses both grass and turf, but has become accustomed to turf at the high school level.

“Turf is the standard for high school soccer, and I am used to playing on turf more than grass,” Kinsky said. “Especially as a

keeper, I like turf because it’s a lot cleaner, and the fields are a lot more consistent and flat.”

While turf is a mainstay for sports in the United States, it’s not always the case in other parts of the world. Paly junior Reyes Aronson has played abroad in both Switzerland and Denmark while representing the Under-16 Swiss national team at training camps last November, where conditions varied.

“This was my first time going out of the country, let alone playing,” Aronson said. “It was such a cool experience, seeing their culture and the atmosphere. The Swiss playing style is very different compared to the style I grew up with. They are very technical and everything is so clean.”

In Europe, natural grass remains the preferred playing space for both professional and youth-level soccer teams. Aronson noted that these fields were significantly

By ARJUN BHARAT and MAX MERKEL

better than what she was used to in California. This is largely due to climate differences and field maintenance standards. Many European countries, particularly in northern and central Europe, have cooler, wetter climates that naturally support lush, green fields, reducing the need for artificial irrigation.

“Playing in the Bay Area on grass is actually worse than when I played in Europe,” Aronson said. “The grass in Europe is much greener and moist. It’s just better quality grass than California, where the grass is either very dry and mainly dirt or just too long.”

For players like Aronson, the difference is noticeable. High-quality grass fields offer better ball control, smoother movements and fewer injury risks compared to artificial turf, which can be harder on the joints.

Turf is generally more consistent, es-

pecially in varying weather conditions, whereas grass is far more volatile and often subject to drastic changes. While snow isn’t an issue in the Bay Area, rain during the winter months can negatively disrupt play with factors like mud

Paly sophomore and lacrosse player Richard Zhang tends to prefer turf, having played on it for both school and club teams.

“They both have positives and negatives,” Zhang said. “Playing on turf, you can get a little bit of abrasions or turf burn if you fall, which won’t happen on grass, but the bounce on turf is also more consistent and turf won’t get muddy like grass does if it’s raining.”

Temperature is also a major factor for turf, especially in the summer months.

According to research from Penn State University, artificial turf can measure

This issue is also becoming relevant on the international level. With the 2026 FIFA World Cup set to be hosted primarily in the United States, strong criticism has arisen due to the playing surface. Most of the NFL fields that will be used for the tournaments are artificial turf, which creates difficult for soccer players, as it increases the chance of injuries and makes the game more difficult to play.

One of the key arguments against turf is its impact on the environment. Accord ing to the NIH, most artificial turf fields use crumb rubber infill (often made from recycled tires) or other synthetic materials that break down over time. These small plastic particles can wash away into storm drains, soil and waterways, contributing to microplastic pollution, which harms aquatic life and ecosystems.

Zhang acknowledges the environmental impacts, but believes that the costs of transitioning are not worth the benefits.

“A 10 out of 10 grass field is the best surface in the world... but those are extremly rare.”

— Jacob Kinsky (‘25)

the elevated temperatures can be dangerous to athletes, with many becoming susceptible to it. The heat not only makes sports like soccer and lacrosse generally more exhausting, but it also changes the

“During the summer, when it’s hotter, the melted rubber in the turf will stick to your cleats,” Zhang said. “This can be really annoying, as you have to spend a lot of time picking it out of your cleats each day.”

The debate over turf and grass is also receiving attention in the local government, as Santa Clara County considered banning synthetic turf in January. The Santa Clara County Board of Supervisors ultimately rejected the ban by a three-totwo vote, but that doesn’t mean the subject won’t be brought back up in the future. Within Palo Alto, there is an attempt to phase out turf usage with the replacement projects of prominent fields like Mayfield Sports Complex and El Camino under discussion.

“[Turf] is not as friendly for the environment, but it is more practical for a lot of schools just to do turf because it costs more to maintain grass,” Zhang said. “I think transitioning to grass might cost too much long-term; that money could be spent better elsewhere.”

Kinsky shares these views, adding that many athletes have also developed their game on turf, with its crisp con sistency being essential to the game.

“I think most sports can be played on a turf field, and should be played on turf,” Kinsky said. “Grass is expensive and hard to maintain, it is inconsistent and can change drastically depending on the weather. Turf is super easy, super clean and doesn’t require main tenance.”

However, the de bate over turf or grass does not need to be a binary one. While both of Paly’s fields are turf, the idea of converting one to grass if necessary is not out of the question.

“For me both grass and turf are good options for different reasons,” Kinsky said. “I look at it like this: a 10 out of 10 grass field is the best surface in the world. But those are extremely rare, and for the most part, I prefer turf.”

As the debate over turf and grass will undoubtedly continue on both the local and national stage, the future of playing surfaces will likely involve a balance of cost, durability and playing quality. With ongoing discussions, advancements in turf technology and grass maintenance could be on the horizon. Whether fields stay synthetic or go back to their roots, the goal will be to keep sports on solid ground— without too many slip-ups.

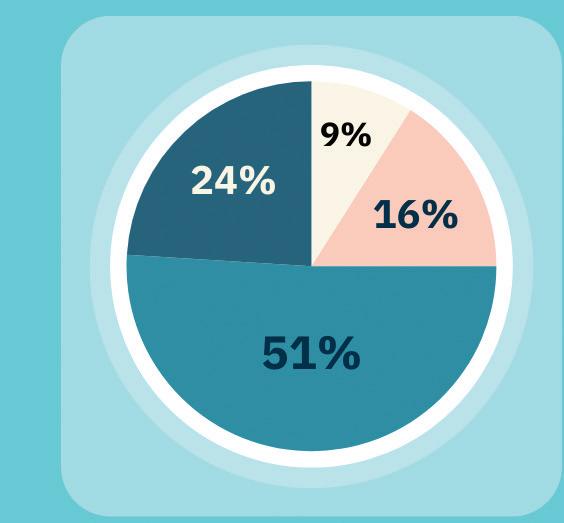

Does the Viking community prefer grass or turf?

Data From 55 Paly Students

Success can come at a high cost. In high school sports, athletes are particularly vulnerable to developing eating disorders as they strive to surpass expectations, threatening their physical and mental health.

s she chases the soccer ball down the field, the world around her be gins to blur. With each step, her disappears, and in the blink of an eye sev

Unfortunately, Gonzalez-Arceo isn’t alone. High school athletes frequently push their bodies to the limit working towards perfec tion. But behind the scores and trophies, many young athletes face a silent oppo nent that few are willing to talk about. According to Eating Disorder Hope, an eating disorder resource center, 42% of high school athletes have some form of an eat ing disorder, which in creases the risk of injury by eight-fold. In sports like run ning, swim ming and wrestling, where being thin is consid ered an advan tage, athletes are at the highest risk of eating disor ders. Athletes in training have high ca loric needs due

up with the level of exercise they may be engaging in. This affects their metabolism, menstrual function, bone health

According to Jennifer Carlson, a Clinical Professor of Pediatrics at Stanford, these disorders stem from numerous different causes, including genetic, social and psychological factors.

“There is no one single reason that eating disorders (ED) start,” Carlson said. “ we tend to think of it as a ‘perfect storm’

Genetics and brain chemistry are usually the root cause of most eating disorders; those with a family history of eating disorders or imbalances in serotonin and dopamine may be more susceptible. Psychological factors such as perfectionism, anxiety or a low self-esteem also invite disordered eating as a coping mechanism. Additionally, environmental factors like poor family relations and traumatic events can also spark disorderly

mended websites and resources are not reliable or healthy.

These diets and online resources may be acceptable for certain people, including some adults, but growing teens, especially athletes, need much more nutrition than these sites recommend to function their bodies properly and healthily.

“I do not recommend using online calorie calculators as they tend to be aimed at adults and do not include the extra calories needed for teen’s growth,” Carlson said. “Athletes, due to their increased levels of exercise, will need even higher levels of calories than the average teenager.”

Cultural and social effects, such as unrealistic beauty standards and peer pressure further reinforce unhealthy eating habits. Today, especially for adolescents, a primary cause of eating disorders comes from societal pressures emphasized by social media. Social media can perpetuate unrealistic standards of what a “healthy body” should look like. Constant exposure to edited images or videos displaying thinness, curviness or muscularity as the ideal body type can lead to unhealthy comparisons. Oftentimes in the media eating disorders are glorified which is a major issue that perpetuates harmful online perceptions of eating disorders. Paly students agreed and shared their thoughts in an

“Stop romanticizing eating disorders,” *Sally, an anonymous poll responder, said. “Stop romanticizing fainting. I always see girls online romanticizing eating disorders, specifically anorexia, and it’s so

Many people online present eating disorders as the best, easiest way to look “better.” Social media influencers or fitness models are constantly sharing new diets, workouts and products, encouraging disordered eating habits that teens latch on to. However, many of these influ-

Online calorie calculators are just one example of encouragement for disordered eating in teenage athletes. But the effects of eating disorders are not just physical, and for Gonzalez-Arceo, her experience with Bulimia brought mental challenges as well. She experienced changes in mood, sociability and even was impacted by depression and anxiety.

“My mental health was at its worst,” Gonzalez-Arceo said. “It’s hard when there’s all this talk about body image from a young age.”

The pressure to meet and maintain these unrealistic standards contributes to the development of an eating disorder, especially if the user is younger and more susceptible to bullying or peer pressure.

This can often be one of the hardest challenges to becoming fully recovered, because an individual’s body image is one they have to get used to for their entire life. Often people with eating disorders have a distorted view of themselves, which can make recovery even more difficult.

For Gonzalez-Arceo, comments from her peers heightened her insecurities and initiated her struggles with disordered eating.

“[My teammates} would say things like ‘maybe if you lost a little weight, you’d run better, maybe if you got on a diet, the uniform would fit you better,’” Gonzalez Arceo said. “Eventually I did lose weight, but then the nice comments and validation I got from it just

My mental health was at its worst. It’s hard when there’s all this talk about body image from a young age.

– Kaitlyn Gonzalez-Arceo,

perience depression.

Despite the extensive negative effects of eating disorders, many suffer in silence. Eating disorders are frequently undetected, leading to dangerous outcomes for the health of young athletes. Wendy Ster-

ling, a registered dietitian and certified eating disorder specialist who co-authored the book: How to Nourish Your Child Through an Eating Disorder and co-developed the Plate-byPlate Approach specializes in sports nutrition and eating disorder recovery. She works with adolescents and athletes to promote a balanced, non-diet approach to health. Sterling states that high performance athletes are often surrounded with an overemphasis on weight, which is not necessarily a helpful measurement of one’s health as a whole. There are many factors that determine athletic wellness.

“Performance is influenced by far more than just weight,” Sterling said. “There are at least 40 factors according to Dr. Ron Thompson who studied this, including skill development, endurance, flexibility, meal timing, adherence to recovery protocols and hydration, among others.”

In the case of many athletes, the effects of eating disorders can upend their athletic career and change their lives permanently. One anonymous Paly multi-sport athlete, referred to in this story as Jane, discusses how she found joy playing sports in her adolescent years. However, as she got older, Jane gradually became aware of her development of disordered eating.

can have devastating consequences on both the mind and the body. When mal nourished, the athlete noticed her bones growing weaker with less muscle to support them, consequently breaking more easily. According to Jennifer Carl son, malnutrition can make individuals more likely to have muscular and bone injuries that can increase the chances of stress fractures and osteoporosis in the future.

“In one game, I broke my nose, a few games later when I was finally able to come back, I broke my shoulder,” Jane said.

Many athletes first develop an eating disorder in an attempt to be healthy or fit, yet they don’t realize both the short and long term repercussions eating disorders have on the body.

“The resulting energy deficiency negatively impacts every system in the body — including the heart, gastrointestinal system, bones and hormones,” Sterling said. “While also impairing sports performance by reducing recovery, endurance, muscle development and coordina tion.”

I realized if I want to be a high school athlete, I have to fuel my body... You can’t have one without the other. – Jane,

“For me, an eating disorder was not something that just came on, it started and I didn’t know how to stop it,” Jane said.

Eventually, a doctor officially diagnosed Jane with anorexia; little did she know, the disease would soon overtake her life. At first, she was only restricted from participating in P.E, but as time went on, the physical effects began to take a major toll on her body and her performance,

“My activity was so limited that I was even worried for myself when I was walking,” Jane said. “I started to feel dizzy and my heart was pounding whenever I played. I was letting myself and my entire team down due to this disorder.”

Those restrictions quickly grew, and soon she was unable to participate in any physical pastimes at all.

The harmful impacts of eating disorders, like those experienced by Jane, extend beyond physical appearance, and

For women, REDS is especially det rimental because it can cause a loss of one’s menstrual cycle, which in turn negatively affects bone health, fertility and cardiovascular health. Athletes frequently underestimate the permanence of these bodily chang es and the seriousness of their disorder. When malnourished, it becomes increas ingly difficult for an athlete to exert the necessary energy needed to improve their performance in their sport. This is a realization that Jane came to terms with during the turning point of her disorder. When she began high school at Paly, Jane tried field hockey for the first time, and fell in love with the sport. This love for field hockey inspired her to begin recovery.

“I realized if I want to be a high school athlete, I have to fuel my body,” Jane said. “You can’t have one without the other.”

Jane began a 100 day treatment pro gram at The Healthy Teen Project, a recov ery center in Los Altos. The Healthy Teen Project (HTP) is an eating disorder treatment center for youth. Based in Los Altos and San Francisco, this facility has both PHP (Partial-Hospitalization) and IOP (Intensive-Outpatient) programs. Both of these programs are quite time consuming for patients, often requiring teens to put their life on hold in order to complete

Raising awareness and encouraging recovery is hard, but I think that teens need to know that they will be supported.

– Sally,

these rigorous programs. Eating disorder treatment is a complicated journey and contains many different levels of care based on the patient’s needs. Most levels of care have medical teams consisting of a psychologist, therapist, dietitian, medical doctor and a family therapist, with the goal of fostering the most effective environment for the patient.

“I put my school, social life and sports

ey and it felt different; I knew I had to have a protein bar before practice, I knew I had to eat lunch if I wanted to practice, I knew my boundaries regarding how much I could do, and it felt so much better.”

According to Jane, her love for the sport kept her going. She didn’t want to go back to treatment, and her newfound awareness of her bodily needs has been necessary to produce success and happiness in her athletic, academic, and social life at Paly.

Jane’s recovery story is one of many, but it’s important to acknowledge that the road to recovery looks different for everyone.

Faina Birman, a nurse practitioner at HTP, has seen many different paths that patients undergo during recovery.

“Recovery is exceptionally individual, gradual, and almost never linear,” Birman said. “We don’t see the same path for everyone.”

It’s imperative to acknowledge and support anyone who may be struggling.

“Let them feel comfortable around you, that’s what they need,” Sally said. “Just be their friend. Raising awareness and encouraging recovery is hard, but I think that teens need to know that they will be supported, that they won’t be yelled at, cursed at, they just need an environment where they will be loved, whether that’s friends or family, and if they don’t get that, that’s why they reach out to their ED.”

As a society, it is crucial to reshape the overall narrative around eating disorders in order to provide genuine support rather than encouraging harmful behaviors.

By challenging stereotypes, being empathetic, and prioritizing education, we can create an environment where those

Restricting food and then overindulging in an unhealthy way

Bulimia

Forcefully

Once considered the face of Stanford football, Andrew Luck is returning to his alma mater, and he is pioneering a new position in college football— general manager.

Playing quarterback in the NFL is a dream for many kids across America. Every Sunday from September to January, young fans nationwide turn on the television to watch their favorite team’s quarterback compete in front of millions of fans. Playing quarterback certainly comes with its challenges, as it is one of the most mentally and physically demanding positions in all of sports. The quarterback’s job is to analyze an opposing team’s defense in a matter of seconds, then making a decision with the ball, and in the process avoiding 300 pound defensive linemen trying to violently knock them to the ground. Getting tackled repeatedly takes a toll on a player’s physical and mental well-being, and in many cases can derail even the most promising careers.

Andrew Luck is a living legend on Stanford campus. In three seasons at the collegiate level, Luck was a twotime Heisman Trophy runner up, and set the school’s quarterback records in all time yards, completion percentage and touchdowns. Luck was a force to be reckoned with on and off the football field, earning a spot as a member of the Academic First Team for the Pac12 throughout each season of his collegiate career. His accomplishments and talent culminated in him being drafted

first overall in the 2012 draft by the Indianapolis Colts, where he then dominated the NFL for seven years. However, his career was cut short due to repeated injuries, and he retired in 2019, just weeks before the new season.

Following his retirement, Luck spent time focusing on himself, avoiding the media and spotlight. Luck is known to have a very private life — separating his family from his football career — so his low profile following retirement did not come as a shock to fans. This changed on a local level in 2022, when Palo Alto High School football coaches David DeGeronimo and Jason Fung received an exciting email: Andrew Luck was interested in coaching Viking football.

By DYLAN ROBINSON, GREG GOODY and ZOE PASHALIDIS

for him. Nevertheless, Luck began as a volunteer coach in 2023, bringing his professional understanding of the sport and knowledge to the team.

“Andrew is a gifted and talented football player with a very high level football IQ,” DeGeronimo said. “I think him deciding to coach at Palo Alto got his juices going again and he renewed his passion for the game.”

” He has developed me immensely for the two years he was with us and helped me become a better quarterback and teammate. - Justin Fung (‘27)

Head Coach DeGeronimo recalls that he at first believed the email from Luck to be a joke. Luck had been under the radar for so long that reaching out for a position seemed out of the ordinary

”

DeGeronimo also points out that Luck’s time at Paly served as a crucial stepping stone, equipping him for the greater challenges that lay ahead.

“I think his few years at Paly gave him valuable experience and convinced him he wanted to rebuild the football program at Stanford,” DeGeronimo said. “Now we get to watch him do great things in football again.”

Throughout his time at Paly, he mainly worked with the junior varsity and freshman teams, specifically with current sophomore and quarterback Jus-

tin Fung.

“The main thing he helped me with was definitely the fundamentals,” Fung said. “He never tried to over step and take over but would always help me with the small things like footwork, reads and tempo. He has developed me immensely for two years and helped me become a better quarterback and teammate. ”

As we build a winning culture and program, we will continue to attract the best, brightest and toughest players. - Andrew Luck

Despite being a quarterback focused coach, his extensive experience as a leader on the field gave him the teaching skills to impact players in all positions, even those on the defensive side of the ball. His commanding presence and leadership was felt by four-year Paly linebacker and Claremont McKenna College commit, Joe Kessler (‘25).

“Even though he was only here for two seasons, his impact on our team will last for years to come,” Kessler said. “His football IQ and passion for the game is unlike anyone I’ve met, and he helped me grow as a player significantly.”

From 2010-2012, Luck dominated the Pac-12 with the Cardinal, winning the Rose Bowl. It seemed as though the entire bay area tuned in to Stanford football games when Luck suit ed up; stadiums packed to the brim with fans trying to witness a Stanford legend in action.

Nowadays, Stanford stadium is lucky to hold 25,000 fans on gameday, a stark contrast from the 50,000 that Stanford averaged while Luck was playing.

Stanford hasn’t had a winning re cord since 2018, and since then the excitement around Cardinal foot ball has continued to dissipate. Shortly after the final game of a

disappointing 2024 season, Stanford announced they hired Luck to be their general manager (GM) of football. This title is new to the collegiate level, as typically the head coach holds all of the power when it comes to running the team. This new position has been implemented by many college football programs across the country, including

”

USC, Texas, Notre Dame and Oklahoma.

As for Luck’s responsibilities at Stanford, his new role has been described by ESPN as “a role that involves everything Stanford football touches.” The managerial position is brand new to college football, leaving Luck and others with uncertainty on the exact responsibilities of a collegiate GM.

“Every GM is a bit different, but [the role has] a lot of similarity to an NFL GM,” Luck said. “My role includes personnel decisions, but also business aspect decisions. This is unique among college football.”

Luck said.

These skills, combined with his extensive football background, have put him in a position to be a valuable asset in shaping the future of Stanford football.

Stanford seems to be trying to recapture the hype that Luck produced while he was on campus — and it might play out in their favor. The hiring of Luck instantly caught headlines and landed him an interview on the popular show “College Gameday” hosted by Pat McAfee, Luck’s former teammate from the Indianapolis Colts.

On the show, Luck highlighted the need for Stanford to adapt their old-fashioned strategies to the new era of college sports with Name Image Likeness (NIL). According to 24/7 sports, over the last five years Stanford has averaged the 32nd overall recruiting class in the nation. Stanford, which has always maintained a commitment to high academic standards, has successfully overcome this recruiting challenge and consistently fielded competitive teams in the past. However, the introduction of NIL has further limited their recruiting options, especially since Stanford is hesitant to spend large sums of money to improve their team. Unfortunately, the promise of a high level education doesn’t compete with the millions of dollars other schools are offering their athletes.

Luck’s brief stint at Paly is the only coaching experience of his football career, but it provided him with valuable insights into how to influence a game from the sidelines.

“Communication skills, organization skills and talent evaluation are areas in which I improved while coaching at Paly, and they have a direct translation on my job now,”

Luck stated that the vision for Stanford is clear, and they are going to be competitive in recruiting and retaining the talent they already have on the roster, as the transfer portal has been an issue for Stanford as of late.

“We are going to go after the best and brightest,” Luck said, “We are looking for tough kids.”

Stanford’s 2025 recruiting class landed ahead of six fellow ACC teams, including rival team Cal Berkeley. Their recruitment should push them in the right direction in terms of ACC play, as they struggled greatly last year, only winning two in-conference games (Syracuse and Louisville).

Luck isn’t only focused on recruiting, as his first executive move as general manager was firing Head Coach Troy Taylor. A fresh start is what Stanford needs, and looking at the future, Luck is confident in Stanford’s path to success.

“Maybe we were behind, but no longer,” Luck said. “The house settlement will bring some sanity to the system and we are poised to compete.”

By MALCOLM GINWALLA, NATHAN LEE and LUKE JOACHIM

Clutch is a skill earned through confidence, discipline and hours of grinding. Clutch athletes are made, not born.

The last seconds of a game hold immense amounts of pressure on the athletes involved. Adrenaline is pumping and your heart rate spikes, your mind either focuses up or stalls.

Whether it’s a last-minute goal or a photo finish, these are the moments where champions are made. For athletes at Paly, these are the moments that they believe hold the most importance.

The first and last five minutes make or break a game. Focus early, and you’re in control; lose the edge and risk falling behind. The first few minutes are crucial in setting the tone and rhythm for the rest of the game.

The last five determine the outcome

opening and closing minutes of a game.

“This happened against Homestead, where we scored a goal near the end of the game, and then we let up in our defense, and they scored to tie the game at the end of the game,” De Martel said. “The most goals happen five minutes after the game starts or before the end of time, so those five minutes in particular are very crucial.”

I need to pull out a big move,” Othuiva said. “I’m usually thinking in those scenarios that I need to go big or go home, and I always go big.”

“The most goals happen five minutes after the game starts or before the end of time, so those five minutes in particular are very crucial.”

—Hadrien de Martel (‘26)

As time dwindles on the clock, every mistake becomes more noticeable and costly. In a close game, the difference between victory and defeat can be a matter of a few pivotal seconds, making every attack, clearance, and goal all the more significant.

From split-second decision-making to the effects of adrenaline, understanding the science of clutch moments is not just about talent but how the body and mind work together under pressure. For junior wrestler James Othuiva, high-pressure moments are where he thrives.

“There have been a couple of unfortunate scenarios where I’m down big, maybe down 10 points, 12 points, and

According to psychologist Tim Woodman, the mental reaction to these spikes in pressure can be attributed to endocrinology. “When people are low in cognitive anxiety, or low in worry, the difference between their best performance and their worst performance is not very big.” On the contrary, when an athlete is anxious, their best performances may be slightly better than usual, but their worst performances will be significantly worse than normal.

It’s in these moments where you hear the term “clutch”, referring to how some athletes manage to perform well regardless of the added pressure in the moment.

But what causes some athletes to rise to the occasion while others falter?

The science behind clutch performances in sports reveals insights into how our brains react to stress, triggering a combination of physical responses and psychological strategies that can turn the tide of a game.

Athletes often rely on mental training, such as visualization and focus tech niques, to manage stress and maintain peak performance during critical mo ments. Leo Terman, captain of Paly’s Varsity Tennis team, tries to manage his stress by taking time after each point to pause and compartmentalize.

“I relax as much as possible to increase my intensity and focus on the things that I can control like my footwork and my mental state,” Terman said. “Taking time between points to make sure that I’m mentally resetting before I go back on court is helpful because I think it’s easy when you’re in a stressful situation to rush through things, and for me, I try to take a step back and breathe and refocus mentally.”

Focus and calming strategies are essen tial in helping athletes harness the surge of adrenaline to enhance their perfor mance rather than letting it overwhelm them. The ability to stay composed may come naturally for some, but it is also a skill that can be developed through years of practice and experience.

The “clutch factor” is critical in all competitive sports settings, and especially on the collegiate and professional level where millions of dollars are on the line and each game is nationally or even internationally televised.

cance of confidence - alongside experience - in “clutch” situations.

“After the two-minute warning, every play becomes crucial, and there’s an increase in the focus of everyone on the field.”

According to a study by Tshwane University, out of the 362 goals scored in the 2022 FIFA World Cup, 24% of the goals were scored in the last 10 minutes of regulation play.

—Jake Wang (‘26)

“I think confidence is more important than experience in a ‘clutch’ situation because even if someone has experience in situations such as these before but lacks the proper confidence to excel, the experiences of the previous movements are not an added benefit to an unconfident athlete,” Byer said.

energy that can be directed towards strategic thinking and emotional regulation.

Varsity tennis player Nuri Hafizi describes how his training in practice correlates to in-game success.

“I’m not thinking about where I want to put the shot; I just think about what I’ve practiced and just aim in a certain direction and trust my practice,” Hafizi said.

When individuals develop strategies to regulate their anxiety, they focus their energy on their performance, entering what psychologists call a “flow state.”

There have been numerous studies on “flow states” in athletes. These studies have primarily measured the following criteria: clarity of goals, action and awareness, and the loss of self-consciousness.

This phenomenon can also be seen in football. For Jake Wang, a junior on the Paly’s Varsity Football team, the waning moments of a game are when he feels at his best.

“I think that after the 2-minute warning, every play becomes crucial, and there’s an increase in the focus of everyone on the field, and it feels as though the entire crowd and other noise just fades away, and I’m just focused on my job and playing at my best,” Wang said.

Coach Brandon Byer, a veteran coach of the Palo Alto Boys Basketball program, explained how he defines the term “clutch”.

“Persistence, sacrifice, and being res-

Confidence can be an important tool for many athletes, including sophomore Justin Fung, quarterback of Paly’s varsity football team.

“I believe mentality is the most important thing in these types of moments, and I feel like mentality and confidence go hand in hand,” Fung said. “Having confidence in making the play in tight moments will help you succeed in those moments. I also believe in treating those clutch time moments like another routine play and not making them bigger than they are.”

Confidence allows an athlete to trust their abilities and make intelligent decisions when the stakes are

According to a study by Joshua Gold on the neuroscience of flow state in the modern world, individuals who enter a flow state are fully immersed, with no attention left to be distracted by anything else.

Coach Byer has years of experience seeing players enter the flow state through hard work.

“Players who routinely can achieve flow states have

prepared and routinized their habits with such precision that any interference from the opposition does not faze the athlete,” Byer said. “When someone prepares by way of skill-specific repetition, achieving mental clarity and routinizing processes that afford a greater probability to achieve a state, such as this.”

One of the greatest basketball players in history routinely entered this “flow state”, helping him perform impressively on the biggest of stages. In a 1992 interview with Playboy, NBA legend Michael Jordan explained, “I feel it [the zone] when the game starts. You just start getting on a roll... You’re in tune with everything that’s going on. You control the tempo, you control everything. It’s like you can do anything, you can take your time, you say anything to people, you seem to be just like you’re on a playground all by yourself.”

“We have all the time during practice to be able to work on specific mechanics, but during the race, my coach likes to say that we are reacting to the hurdle.”

entering a flow state on our team, I think we try to cater opportunities for that athlete to continue their success by accentuating positions to put them at the greatest advantage,” Byer said. “For example, if a player on our team has made 3 or more three-point shots in a row, we would call player-specific actions for that individual to ensure they get a touch on the ensuing positions.”

—Julie Yang (‘27)

When an athlete reaches a “flow state”, the game plan needs to change on the fly.

“As a coach, when I observe a player

Gold also highlights that participants in the study mentioned a collection of other psychological phenomena associated with mental “states”. These include a feeling of control over the activity at hand; an experience of time distortion, in which a person loses awareness of how time is passing; the removal of self-consciousness in which a person loses the awareness of themselves as well as thoughts of everyday problems; a feeling of transcendence, where the person feels a sense of unity with the activity.

Sophomore Julie Yang, a hurdler on the Paly track team, spends hours perfecting her form, trying to ingrain the technique

Simone Biles

Tiger Woods is considered one of the most clutch athletes of all time. Known for his comebacks, he has 82 PGA Tour wins with more than 15 championships.

Simone Biles has routinley pulled off incredible perfomances. She had a great bounce back performance at the Paris Olympics, regaining her title.

into her subconscious so she can relieve mental stress on race days.

“Especially in a race such as the hundred hurdles, I don’t have the time to be able to process or adjust at the moment,” Yang (‘27) said. “We have all the time during practice to be able to work on specific mechan ics, but during the race, my coach likes to say that we are reacting to the hurdle.”

Using this in tensive approach, Yang clears each hurdle instinc tively during rac es, removing the split-second decisions that could slow her down.

Similarly, senior Jacob Kinsky - Paly varsity soccer’s goalkeep er - considers how overthinking can negatively affect his in-game performance.

Throughout his career, Lebron James has been one of the most clutch players. James has had 17 gamewinning shots and five buzzer beaters in the playoffs.

Leo Terman (‘25) hits a first serve.

“When you practice, you’re not practicing with the adrenaline of the clutch or the fear of performing well,” Kinsky said. “Any negative thought will just throw you off your game, so you have to try and just clear your mind and concentrate.”

Athletes who are effective in controlling their thoughts and emotions - focusing instead on the immediate task at hand - are capable of succeeding in the “clutch”.

While natural talent plays a role in athletics, the ability to perform under pressure comes down to deliberate commitment and preparation. Through interviews with Paly athletes across multiple sports, a common theme emerges: those who excel in crucial moments have developed specific mental and physical routines through countless hours of practice. It’s not just experience, but the confidence built through preparation that enables athletes to stay composed when the pressure peaks.

By TYLER CHEUNG and EVIN STEELE

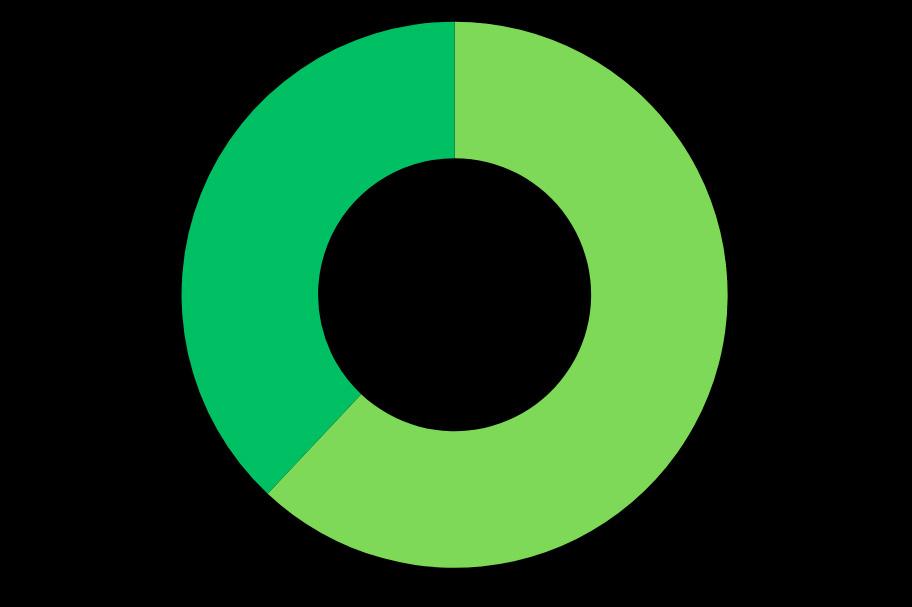

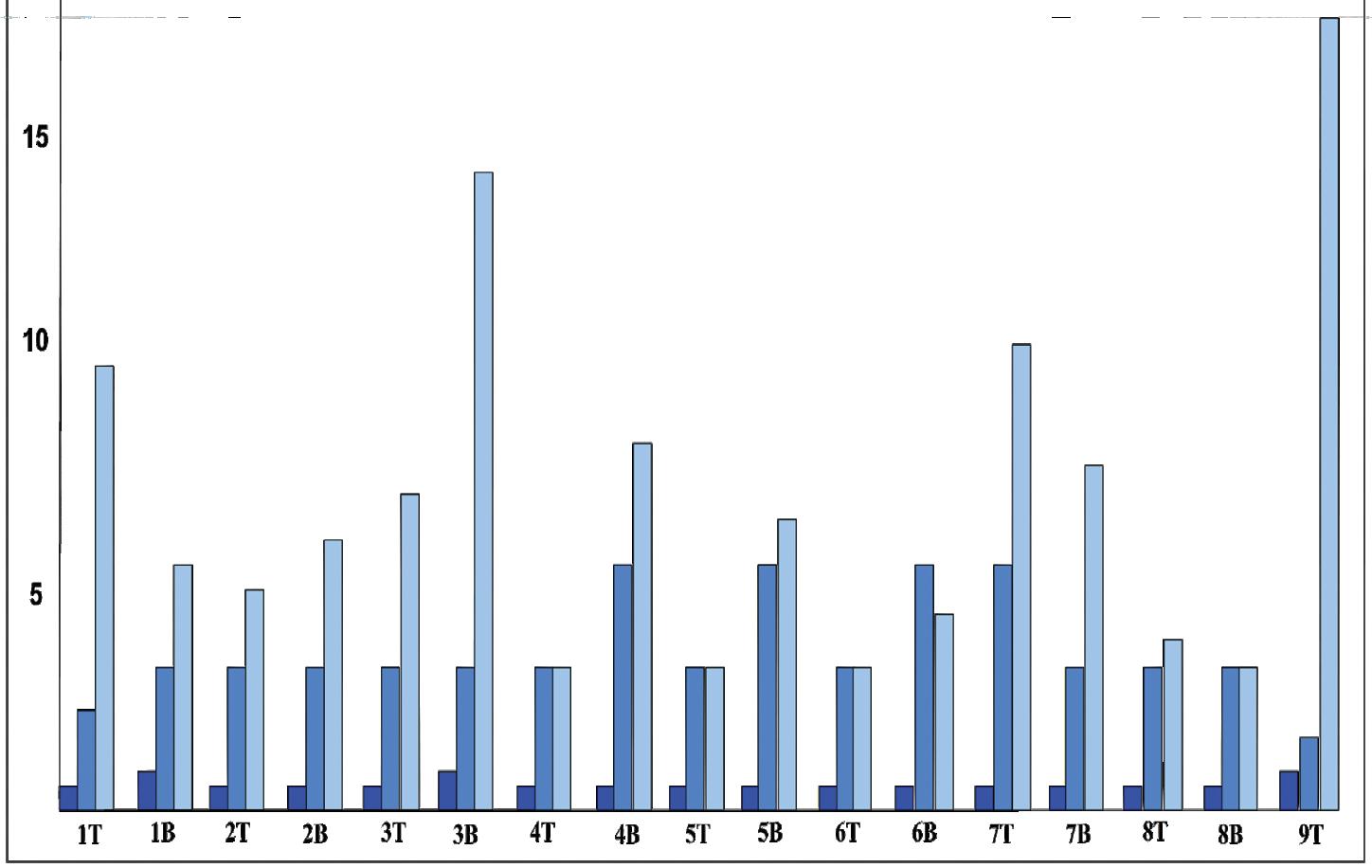

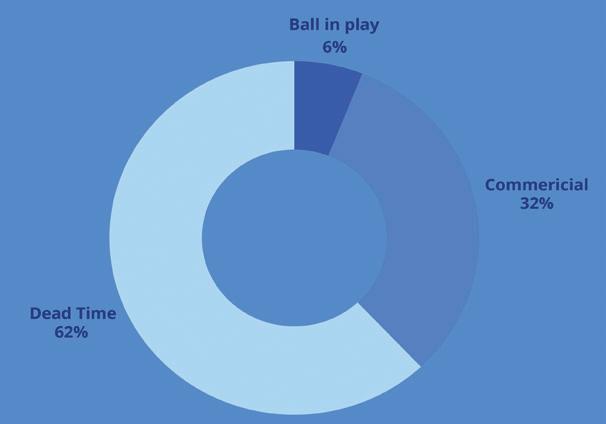

Sports fans crave action-packed moments during their viewing time, but many sports spend much of their broadcast on pauses, timeouts and commercials. Let’s explore which sports offer the most live play time compared to stapages.

Despite being considered one of the most action packed sports, football games consist of relatively little action in the grand scheme of the game. There are constant pauses between plays, and the ball isn’t live for a majority of the game. Similar to baseball, football relies on bursts of excitement rather than a constant flow of action. “A certain amount of commercials are good, but I feel like sometimes they just play an unnecessary amount,” Paly junior Brandon Tu said. “Like one time I saw they came out of a commercial break and showed the kickoff and im-

mediately went back to more commercials.”

All levels of football include significant stoppage time in their games, but the commercials in the NFL and college make the runtime of a broadcast drastically longer. “I think the main problem with the pace of watching football is all the timeouts and commercial breaks,” junior Kacey Washington said.

As a whole, one of the issues with football is that the time on the clock is not a good representation of how much time will actually pass before the game ends.

“For

sports with a stopping clock like football, it is difficult to understand how long the game will truly last, as five minutes on the clock could actually mean there is still 40 minutes left of real time.”

- KHRISAR MAGANA

: Dead Time

: Commercial Time

: Live Play Time

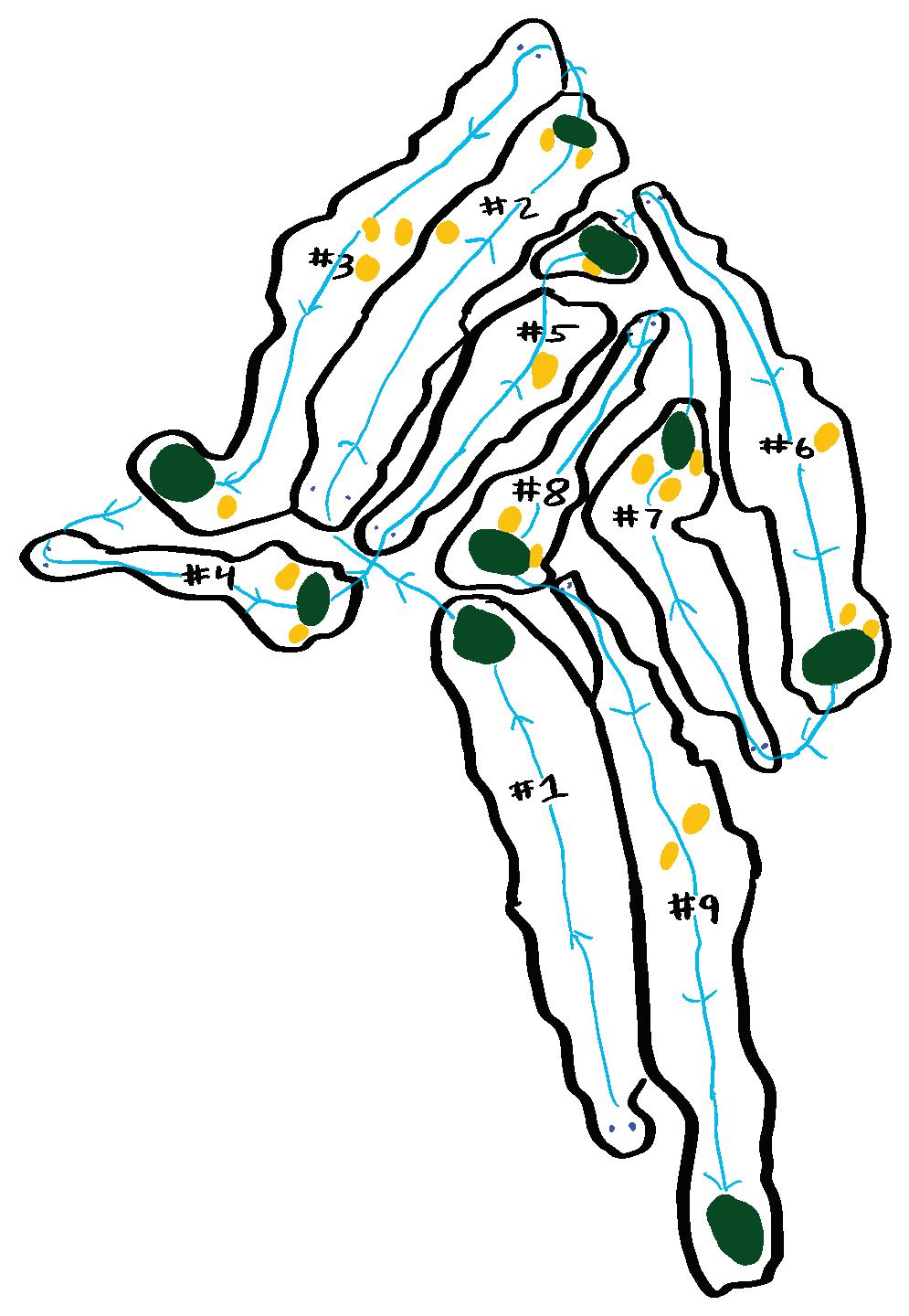

Golf is easily one of the slowest sports, as a majority of the time is spent walking in between shots and analyzing certain aspects of a shot. Most amateur 18-hole rounds last four to five hours, with players averaging 100 shots total, or roughly one shot every three minutes. One of the more frustrating aspects of golf is waiting for groups playing in front of you. With multiple groups playing on the course at the same time, faster groups are usually forced to regress to the speed of slower groups.

“Oftentimes there are old folks in front of you that take extra time to shoot their shots and I usually have to wait an extra two and a half minutes,” junior golf player Dylan Liao said.

The sport takes an adequate amount of thinking and calculation, as a majority of the time not hitting a ball is spent making important decisions about your next shot.

“It may seem like there is a lot of standing around, but we are always doing something,” Liao said. “I think that if we are walking with purpose and not spending five minutes per shot I think the pace of play can stay smooth.”

Baseball is often criticized for its slow play and infrequent activity. With only a few slips of action every game, it can be difficult for new and casual fans to stay invested in the sport. Baseball is unique in that it doesn’t utilize a clock system. Instead, the pace of the game is controlled by an inning system, which can have unpredictable durations.

“There are some stretches during the game where I’m not super actively playing, but I think even at those points, you’re still actively engaged in the game,” senior baseball player Gus Soedarmono said.

The MLB has tried to speed up pace of play by making defensive shifts illegal, increasing base size and integrating pitch clocks, but highschool baseball has continued with the old rules.

“High school should definitely add a pitch clock,” Soedarmono said. However, some fear the MLB is heading in the wrong direction with its recent use of their new ball and strike challenge system allowing players to challenge balls and strikes, slowing down the game even further.

“It may seem like there is a lot of standing around, but we are always doing something. I think that if we are walking with purpose and not spending five minutes per shot I think the pace of play can stay smooth.”

- DYLAN LIAO (‘26)

Average Time Waiting vs Playing

Total Time (Nine Holes):

Two hours 30 minutes

: Wait Time : Play Time

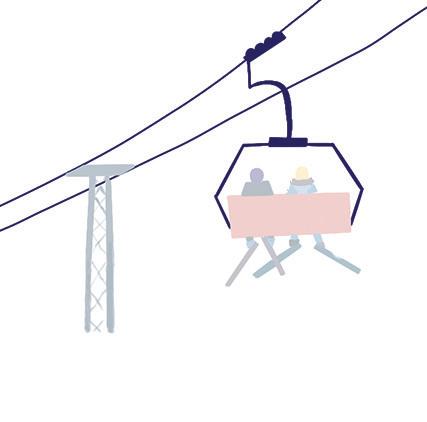

Many competitive Viking students participate in skiing competitions, located in remote mountains far away from Paly. However, very few know of the organization of these snow sports and the efforts made by the athletes.

By FINNEGAN SCHOEBEL and ADI WEINER

Junior Oliver Payne stands on top of Eagle Bowl at Kirkwood Mountain, adrenaline coursing through him as he imagines the path he’s practiced more times than he can count. When the announcer’s megaphone finally calls his name, he pushes off, his poles throwing snow into the air behind him. Cutting across the open mountain, Payne heads for his first launch point — a six foot cliff into a soft landing — following the track he practiced on his previous days exploring the mountain. Throwing himself from the lip, Payne soars through the air, lands cleanly and continues his run.

Many Paly students ski recreationally, heading up to the mountains a few times a year for some casual fun. Payne however, skis with a more competitive goal, as a member of Kirkwood’s Freeride team. Skiing is not just a casual experience, but an integral part of Payne’s identity and sports life, and his commitment towards the sport goes beyond that of most Paly ath-

I need to train for each event every weekend in order to stay at the highest level.

letes.

“My car rides are usually around three and a half to four hours each way up and down from Tahoe,” Payne said. “We basically need to leave immediately after school on Fridays to get there before traffic picks up, otherwise we would be getting into the mountain around midnight.”

While an average or advanced skier may understand the need for the occasional long car trip as a necessary sacrifice for time on the snow, Paly’s most competitive athletes on the slopes are willing to make these drives every single winter weekend. Even worse, these stays are only for a day and a half of training before school mandates return.

Payne and his family are amongst a small but dedicated group of Paly athletes whose sports take place on the mountain. Although relatively large numbers of Paly students ski, whether once a season or embarking on multi-week trips to remote mountains, only a few are highly active and compete in one of ski racing’s main competition formats.

In fact, few of Paly’s casual skiers know much about how skiing competitions really work. Junior Luca Vostrejs, whose family skis multiple times each winter in the Tahoe basin, recognizes his lack of understanding about skiing’s competitive side.

“I started skiing when I was just two years old, and have skied every year since with friends or family,” Vostrejs said. “Even still, I know next to nothing about competitions.”

While the remoteness of competitive skiing — both in the location of mountains and in their rarity — and the relatively few Paly athletes who take part make its relative anonymity understandable, it’s import-

ant to understand the complicated and intriguing competitions that these athletes are spending hours of their time preparing, training and competing for.

These competitions that Payne participates in are held in the Lake Tahoe region and across the country, fostering a niche community dedicated to high level achievement in skiing. Most of Tahoe’s biggest mountains have their own, tightknit competition teams, including Palisades, Sugar Bowl and Kirkwood mountains.