SEE THROUGH THE NOISE

© MACIEK NABRDALIK

ALEXANDRA BOULAT 4

ALI ARKADY 6 STRAPPADO

ANUSH BABAJANYAN 8 TROUBLED HOME

ASHLEY GILBERTSON 10 WHISKEY TANGO FOXTROT

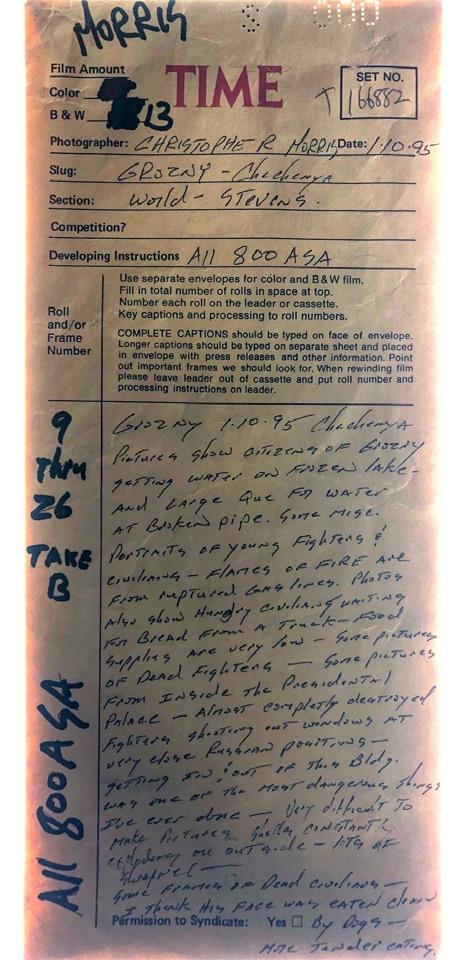

CHRISTOPHER MORRIS 12 ON CHECHNYA

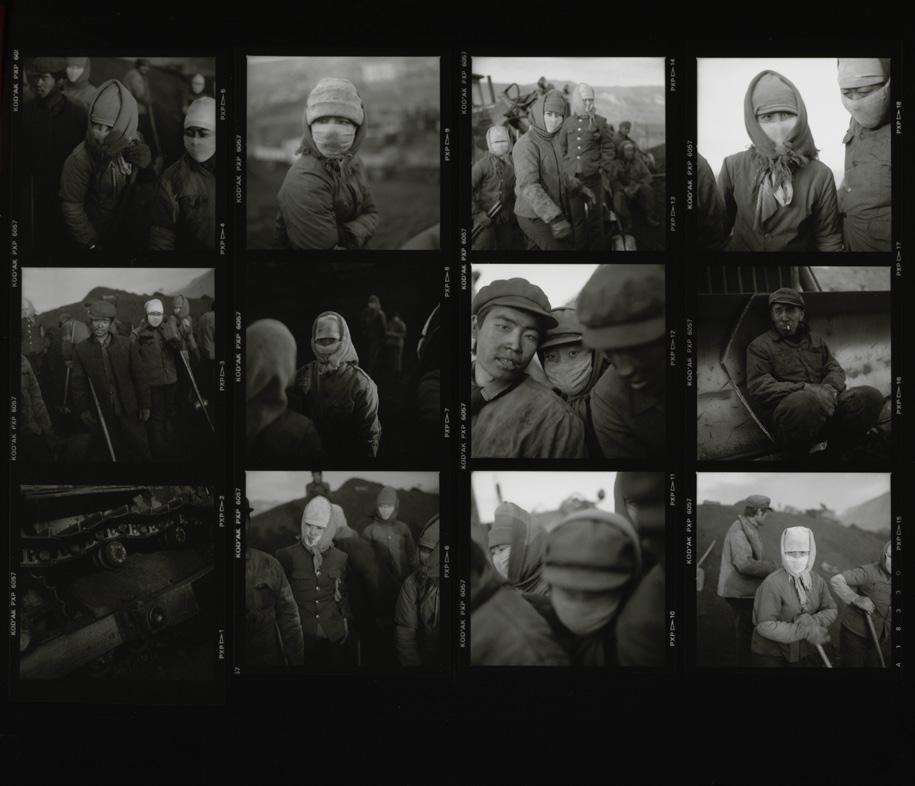

DANIEL SCHWARTZ 14 THE GREAT WALL OF CHINA (1987-1988)

DANNY WILCOX FRAZIER 16 LOST NATION

ED KASHI 18 AGING IN AMERICA

ERIC BOUVET 20 UKRAINE: WAR DIARY

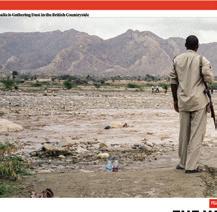

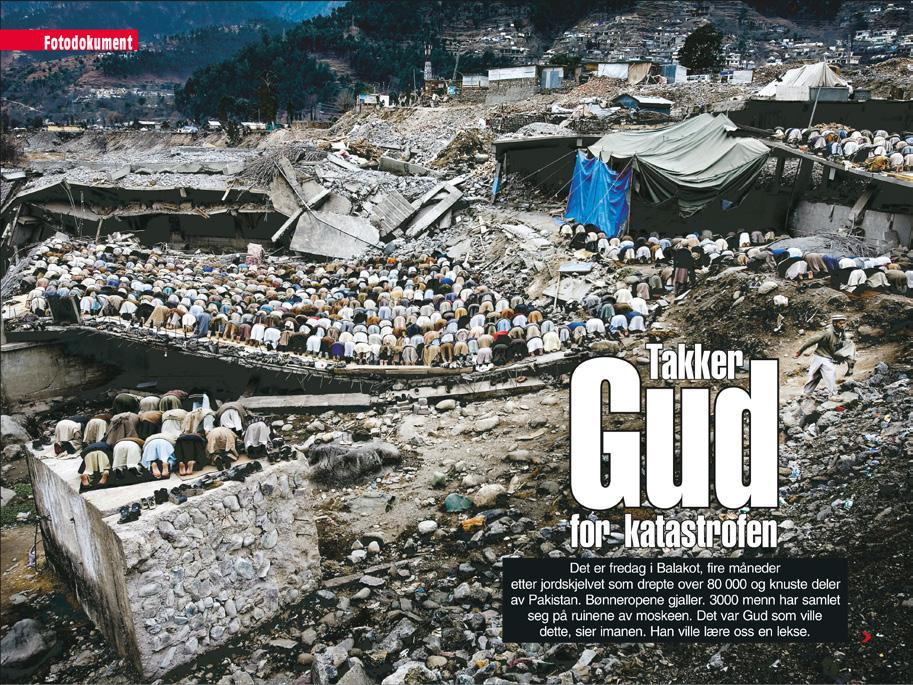

ESPEN RASMUSSEN 22 EARTHQUAKE IN KASHMIR

FRANCO PAGETTI 24 VEILED ALEPPO

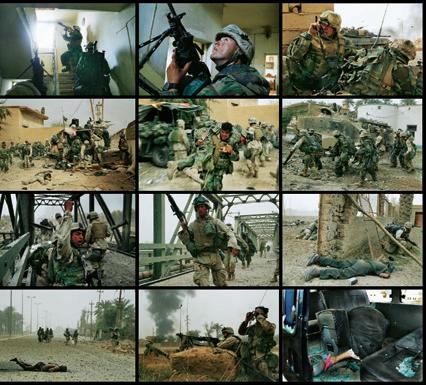

GARY KNIGHT 26 INVASION: THE BATTLE FOR DYALA BRIDGE, IRAQ

ILVY NJIOKIKTJIEN 28 BORN FREE

JOHN STANMEYER 30 SIGNAL

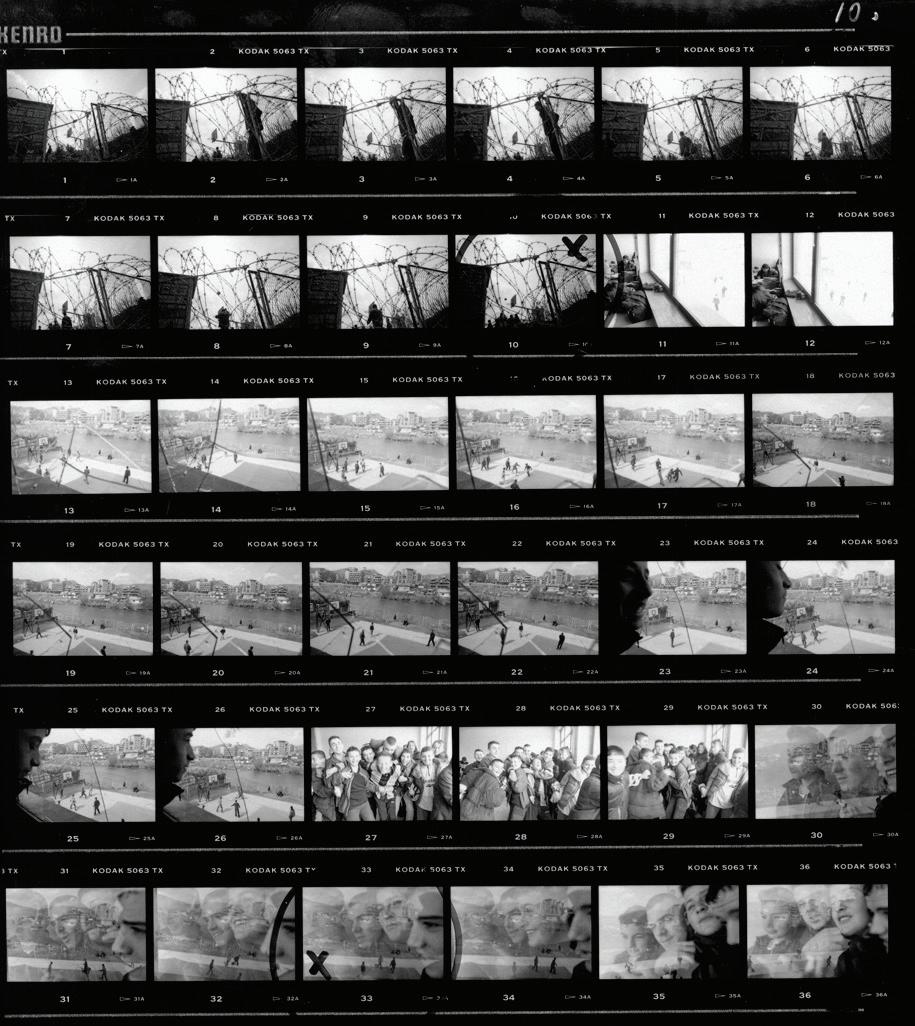

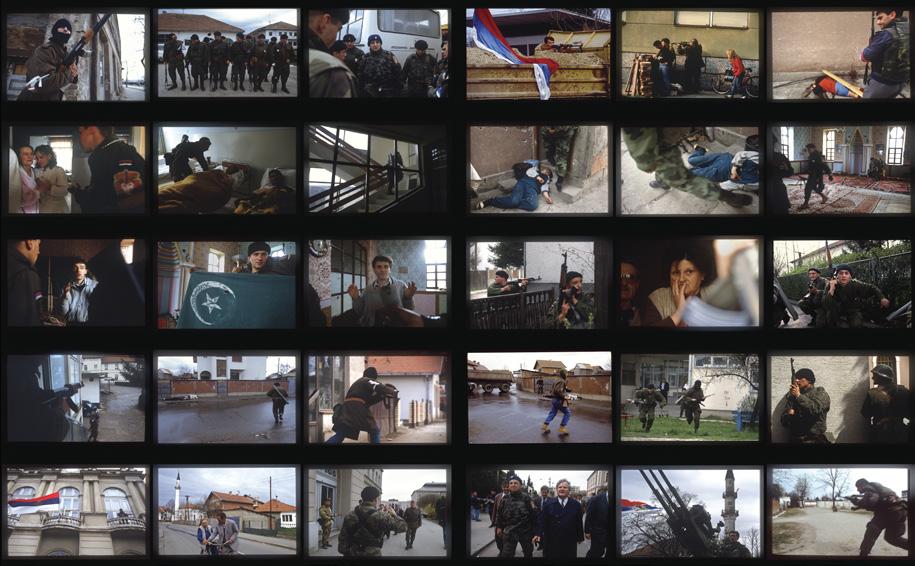

JOACHIM LADEFOGED 32 MITROVICA, KOSOVO

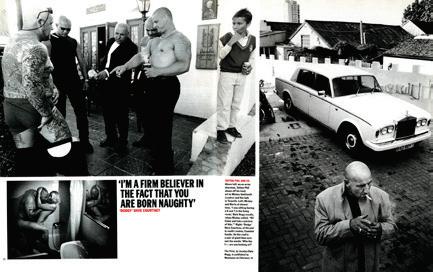

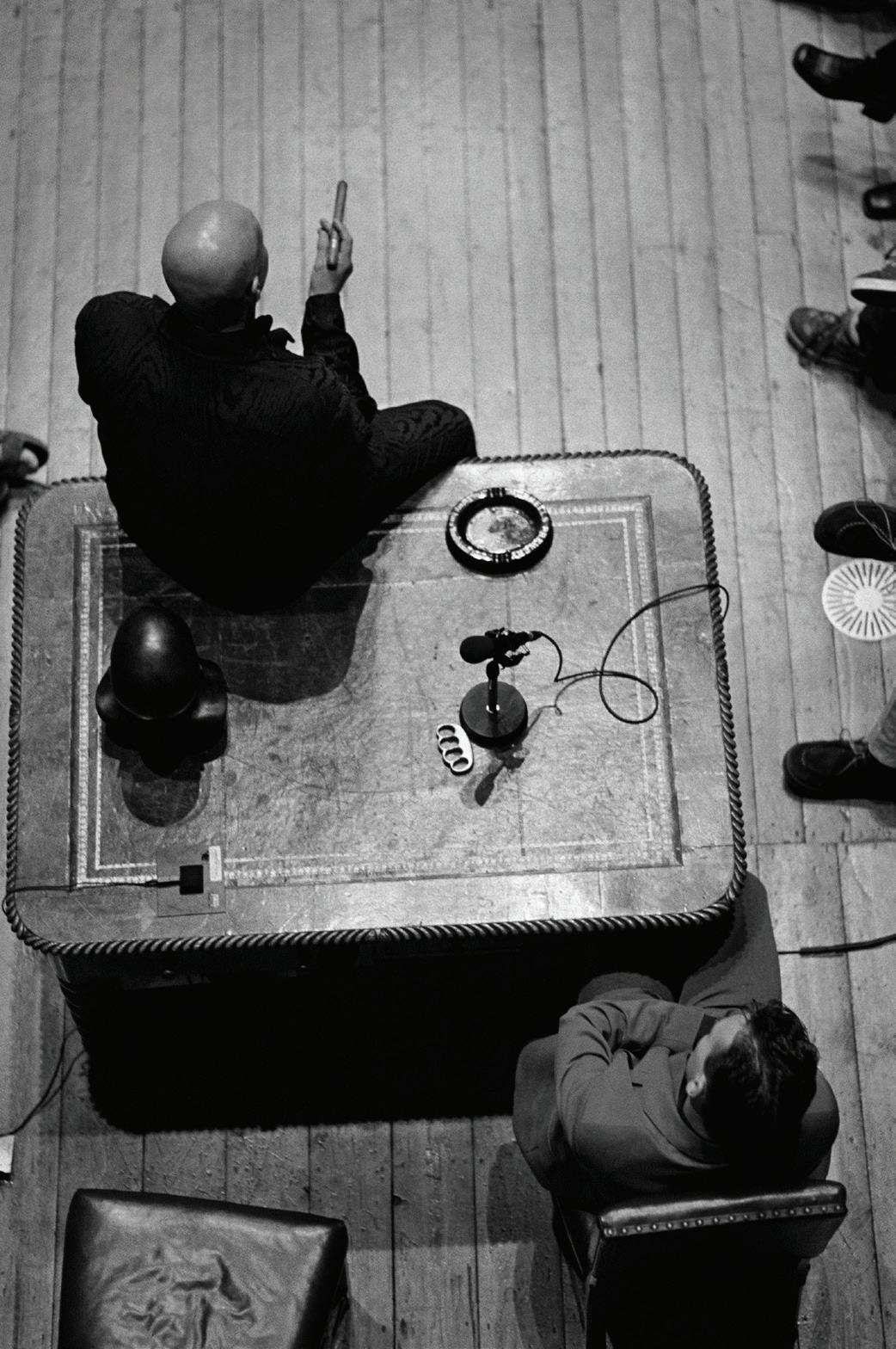

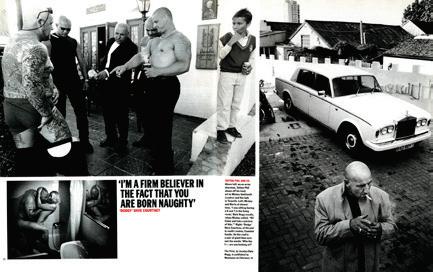

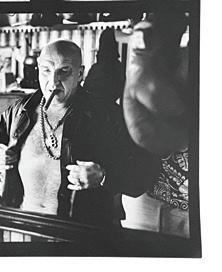

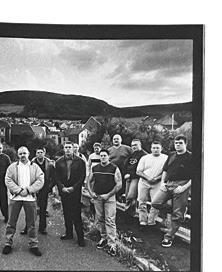

JOCELYN BAIN HOGG 34 THE FIRM

LINDA BOURNANE ENGELBERTH 36 DIARY FROM ALGERIA

MACIEK NABRDALIK 38 LESBOS

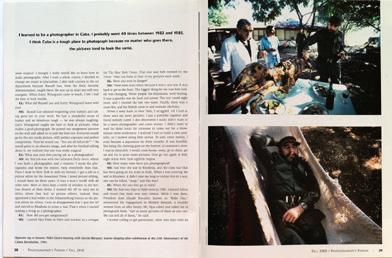

MAGGIE STEBER 40 ON HAITI

NICHOLE SOBECKI 42 A CLIMATE FOR CONFLICT

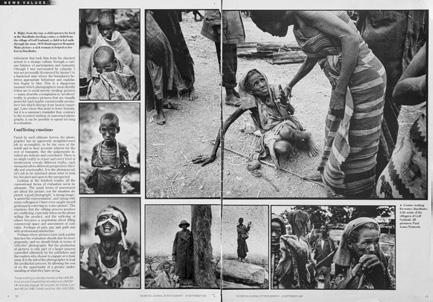

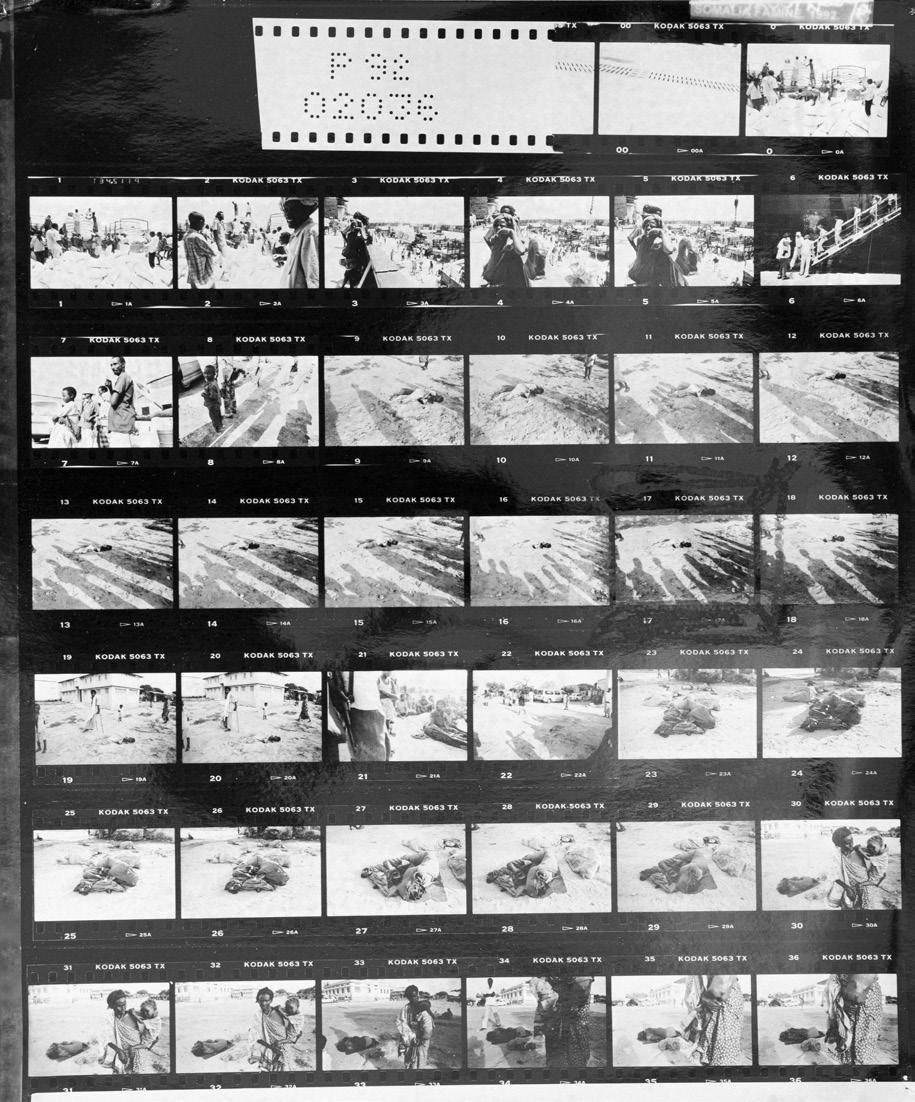

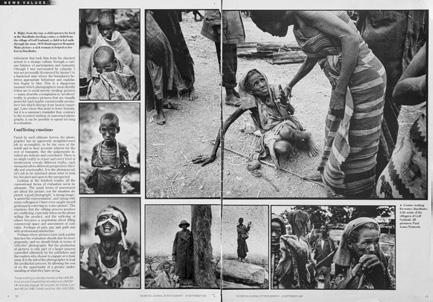

PAUL LOWE 44 A FAMINE IN SOMALIA

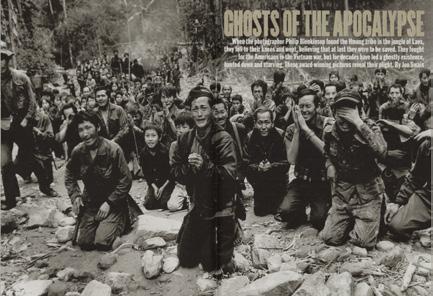

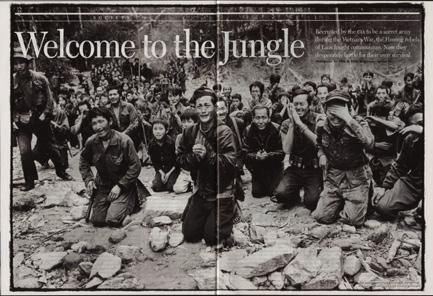

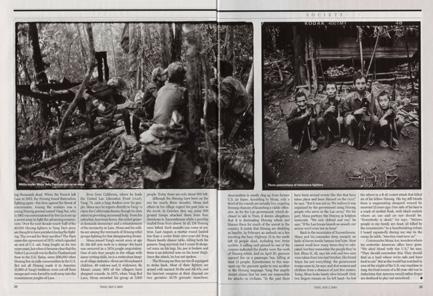

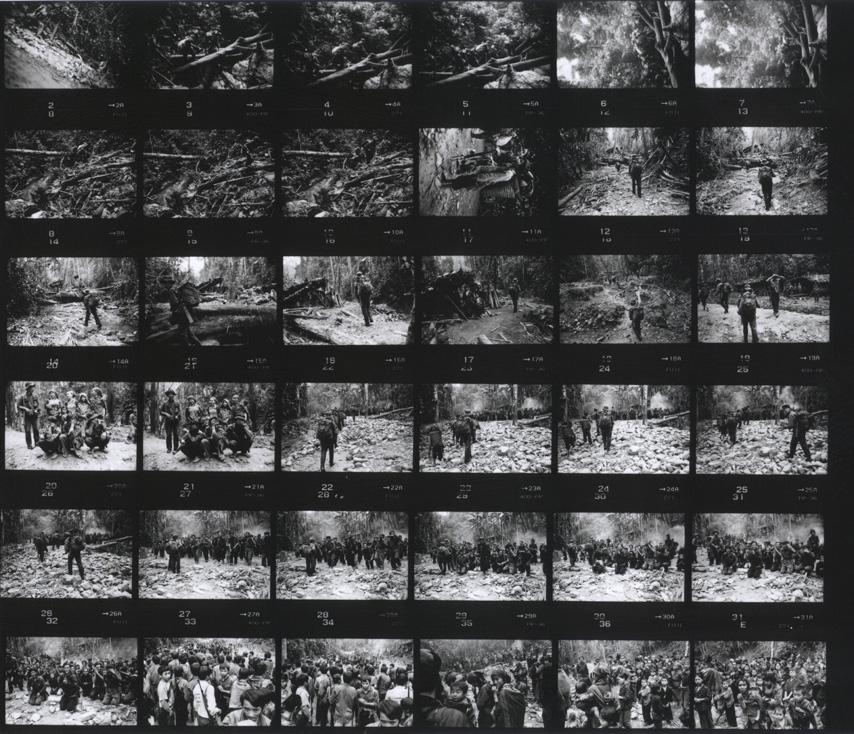

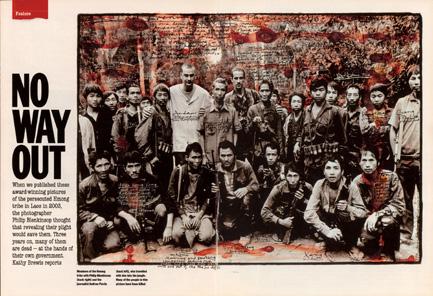

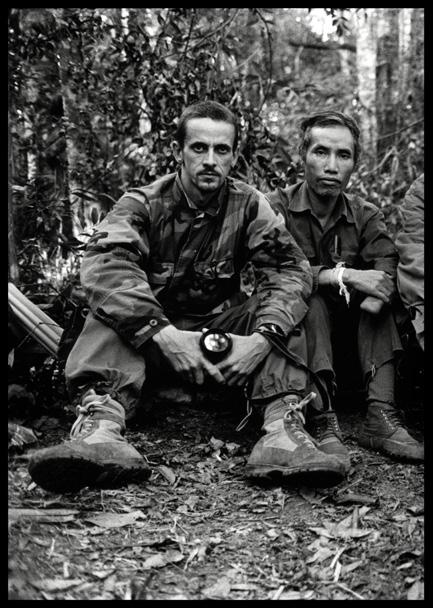

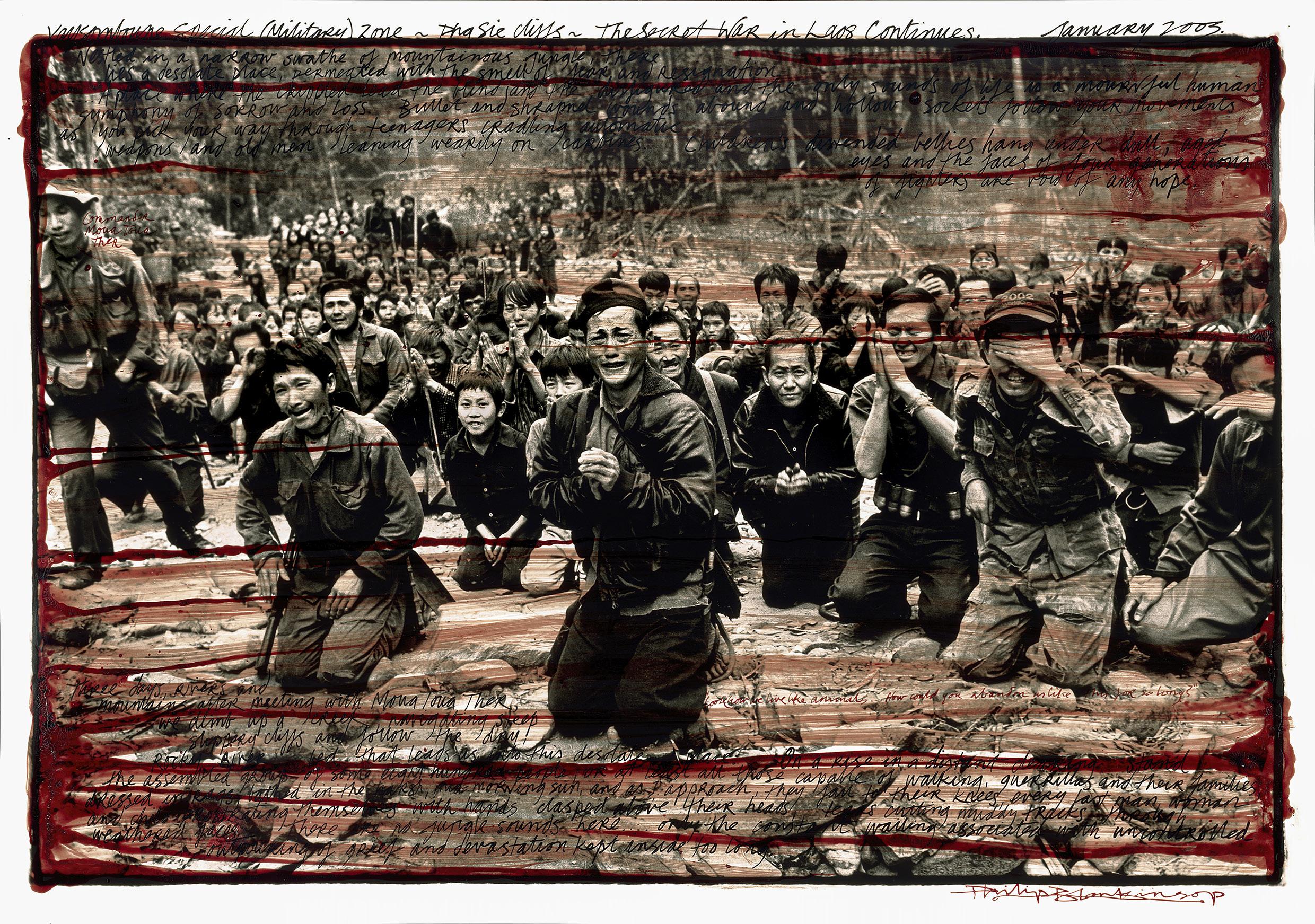

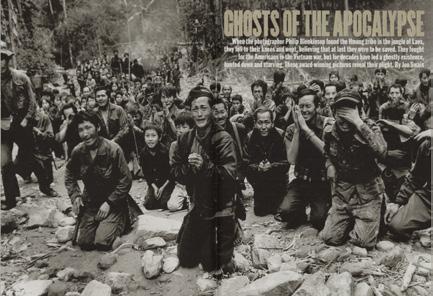

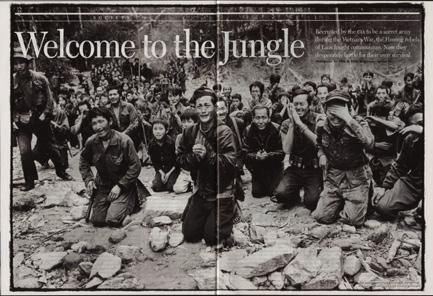

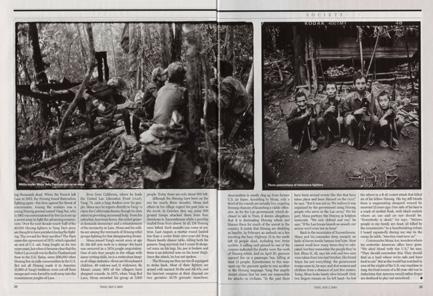

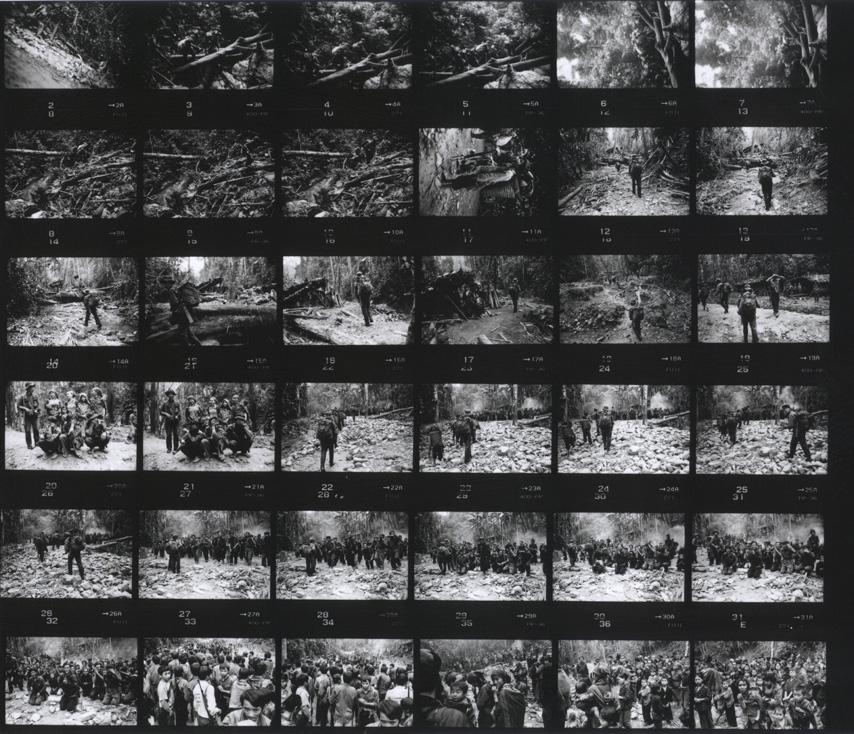

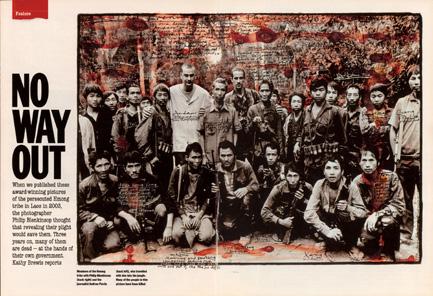

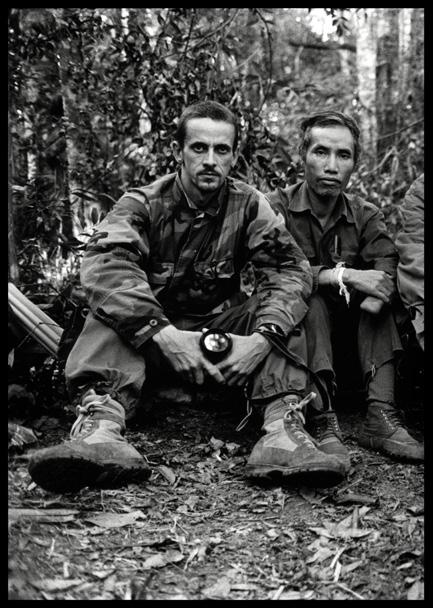

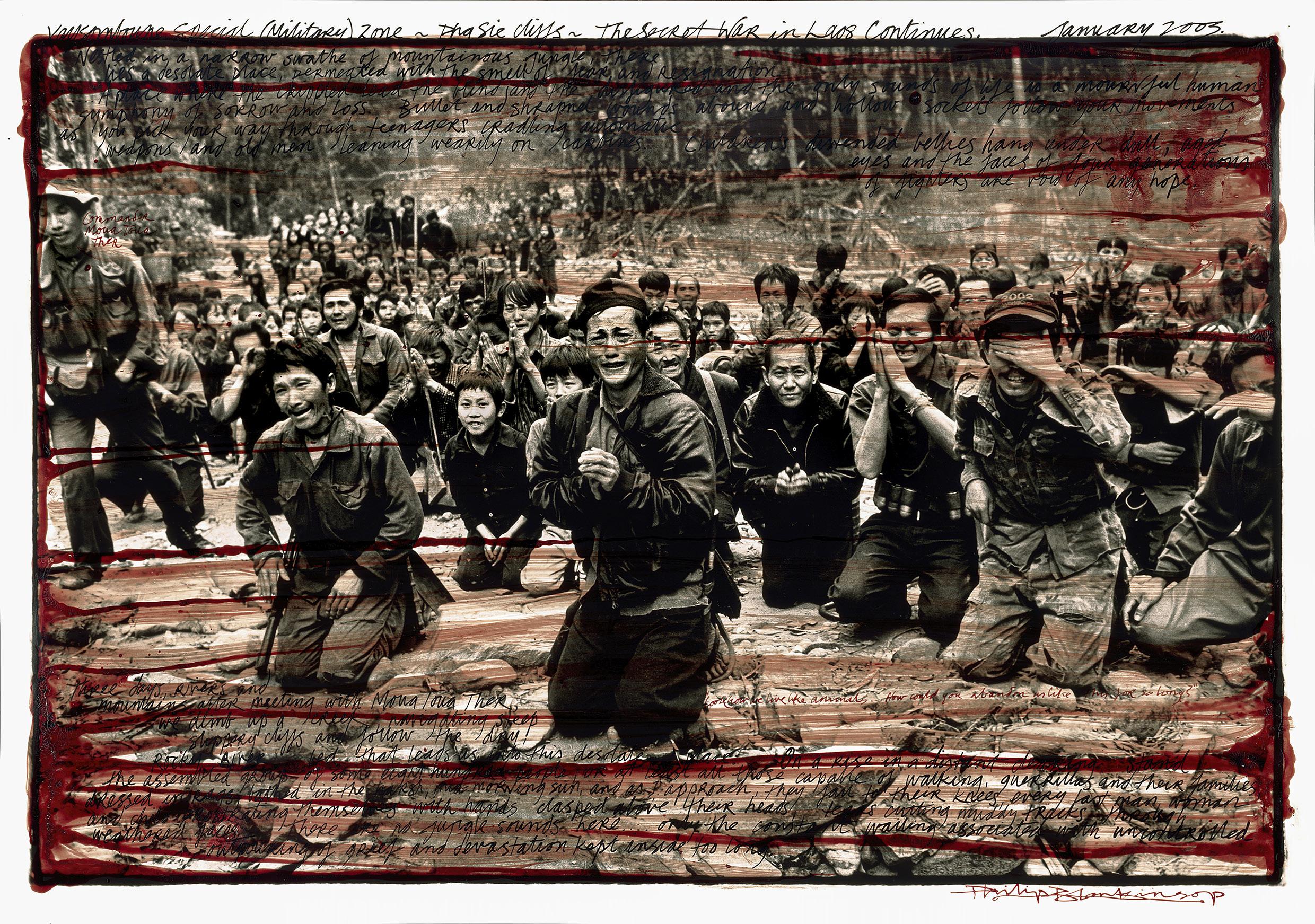

PHILIP BLENKINSOP 46 HMONG IN LAOS

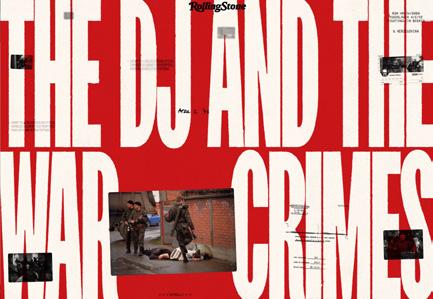

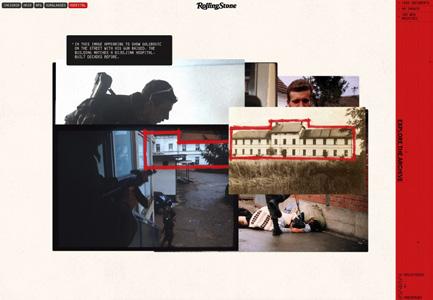

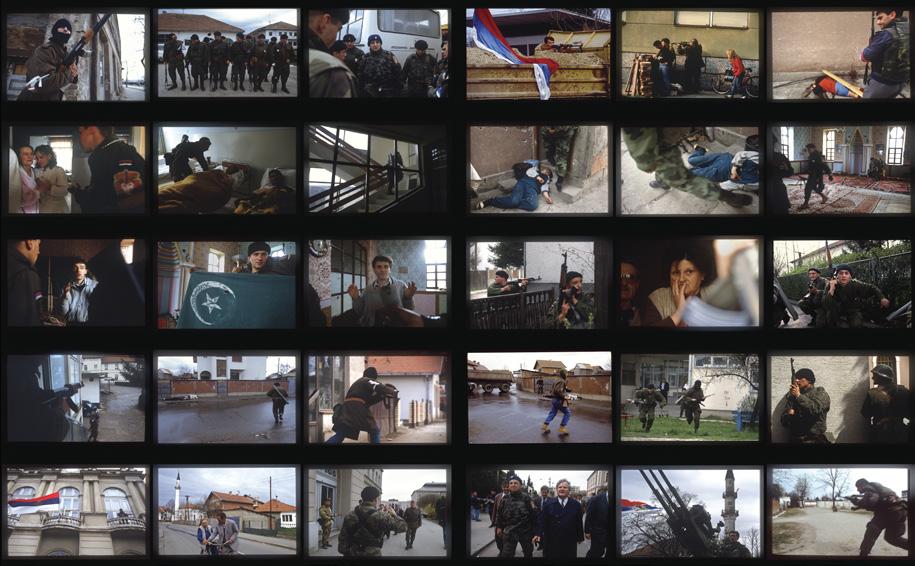

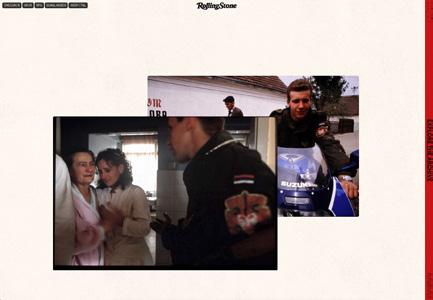

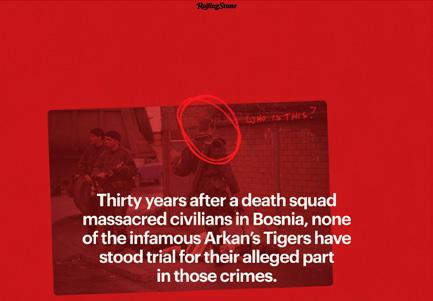

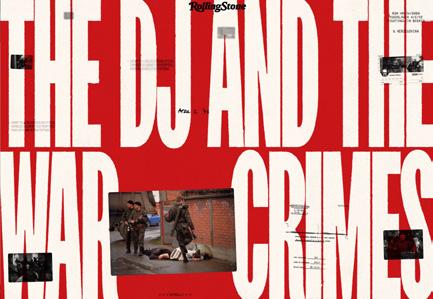

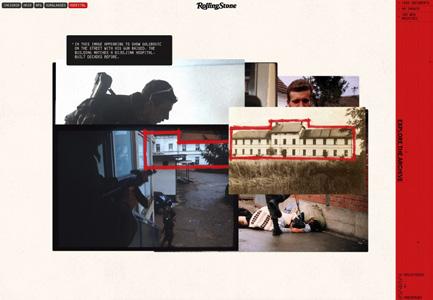

RON HAVIV 48 WAR CRIMES IN BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA

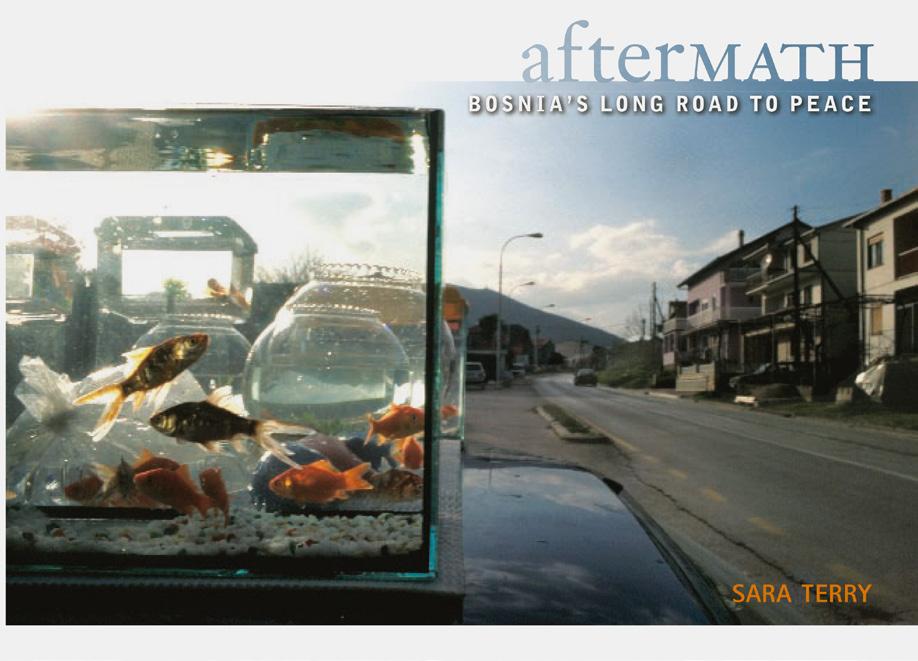

SARA TERRY 50 AFTERMATH

SEAMUS MURPHY 52 THE REPUBLIC

STEFANO DE LUIGI 54 KENYA DROUGHT

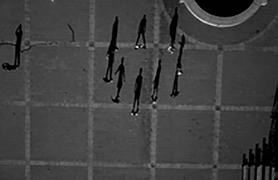

TOMAS VAN HOUTRYVE 56 BLUE SKIES

ZIYAH GAFIC 58 QUEST FOR IDENTITY

SEE THROUGH THE NOISE

The dawn of the digital era enabled the creation of VII on the 8th of September 2001. Three days later, Al Qaeda attacked the United States. In the following months, while the burning dust of the Twin Towers still choked New York, all seven founding members documented the violence that followed. In the ensuing years, as the narrative of the new century was being written, they photographed the invasion and occupation of Iraq, the wars in the Middle East, and the chaos that smothered an unjust world. The name VII became synonymous with courageous and impactful photojournalism.

VII went small and photographer-owned. The photographers believed in the power and energy of intimate collective effort at a time when corporations were acquiring smaller photo agencies and consolidating what had been a rich and diverse ecosystem into giant conglomerates. VII was created to give its members independence and enhance their ability to work on stories that mattered in partnership with the world’s leading press. It created new opportunities the photographers could not imagine. But the digital revolution that enabled the growth of VII also precipitated a catastrophic loss in revenue for its clients in the press.

Photojournalism means taking risks; it requires initiative, resourcefulness, empathy, and courage. It also involves trust, imagination, collaboration, and partnership. Publications and the photo agencies that served them were once

essential partners in the life of a photojournalist. But trying to sell the news to a public that expects it for free means the press has fewer resources to deploy independent photographers and commission original work. Consequently, the media and photo agencies now have less impact and influence on the production of visual journalism. So, what next?

Anticipating the shrinking space the media would occupy in the lives of photographers, The VII Foundation was created to innovate and lead in the non-profit arena, unlimited by the constraints of the editorial marketplace. One of its objectives is to train and support photographers as they continue scrutinizing a world in turmoil and hold those who crave power to account. Ours is a world where leaders regard facts as optional, human rights as an inconvenience, and where it is increasingly difficult to differentiate between artifice and truth. Even the word truth is hard to explain — and is best defined by being the opposite of something — falsehood.

This is the first collective exhibition by VII in Arles, and it marks the acquisition of VII by The VII Foundation earlier this year. The photographs on these walls are among the most significant images of the events and issues they portray. They are an enduring testament to the importance to our fragile societies of a bold form of journalism that is free of artifice and falsehood, and that is an essential pillar of The VII Foundation.

Production & Curation: Ziyah Gafic / Gary Knight / Yonola Viguerie

Editor: Amber Maitland

Co-producer: Marianne Tollié

Graphic Design: Enes Huseinčehajić

Printing Labs: BlackBOX Sarajevo / ateliershl, Arles

ALEXANDRA BOULAT

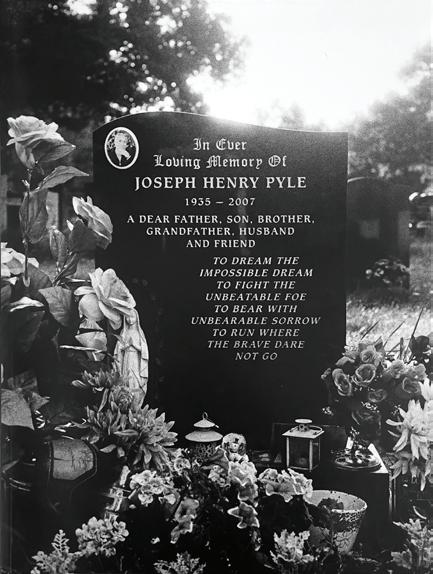

ALEXANDRA BOULAT 1962 – 2007

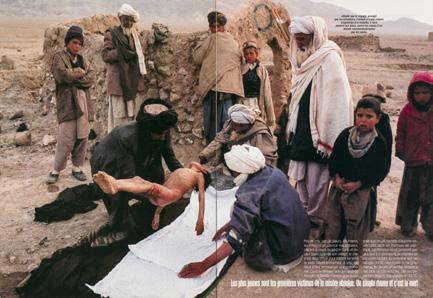

Alexandra Boulat, with her friends John Stanmeyer and Gary Knight, was an early driving force behind the creation of VII. Born into a distinguished photography family, she was an artist before she chose to work as a photojournalist and war photographer. She was one of the most influential photographers to document the Balkan wars, paving the way for many female photographers who followed. She spent much of her professional life focusing on the impact of war on women; she was the architect of one of the most deliberate, focused, and militant bodies of work on the victims of conflict and injustice of our time. She once said, “You can show a war without showing a gun”, a maxim illustrated powerfully by her poignant and devastating photograph in this exhibition. At the time of her premature death in 2007, she was elected a Chevalier de l’ordre des Arts et des Lettres.

COURTESY OF ASSOCIATION PIERRE & ALEXANDRA BOULAT ©

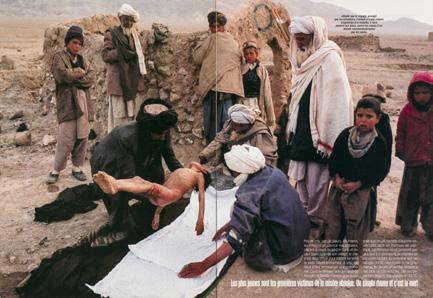

JEROME DELAY

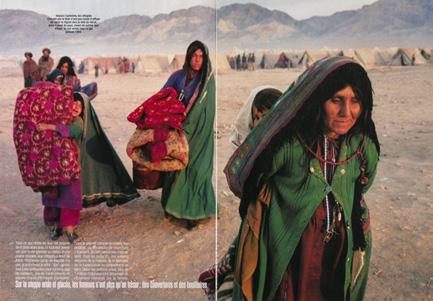

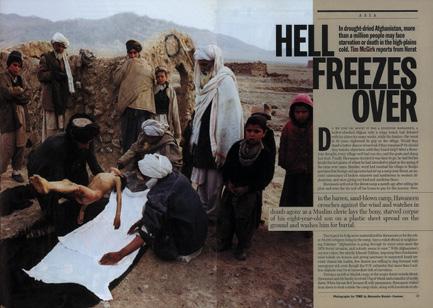

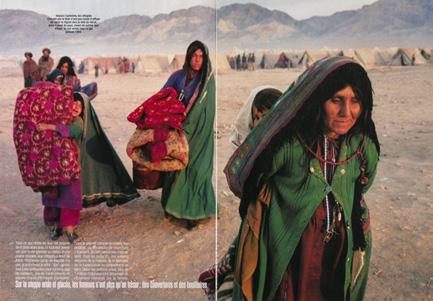

Preparations for the funeral of an 8-year-old child who died of cold in Herat Marsak refugee camp. His two uncles prepare the body before bringing him to the camp cemetery under the eyes of a few of his family members. 30,000 internally displaced people live in miserable conditions in a camp a few kilometers away from Herat, Western Afghanistan. Because of the draught and the war raging on several fronts in Afghanistan, one million people face a humanitarian disaster all over the country. Near Herat, Western Afghanistan, February 15, 2001.

Preparations for the funeral of an 8-year-old child who died of cold in Herat Marsak refugee camp. His two uncles prepare the body before bringing him to the camp cemetery under the eyes of a few of his family members. 30,000 internally displaced people live in miserable conditions in a camp a few kilometers away from Herat, Western Afghanistan. Because of the draught and the war raging on several fronts in Afghanistan, one million people face a humanitarian disaster all over the country. Near Herat, Western Afghanistan, February 15, 2001.

ALI ARKADY STRAPPADO

Are the good guys any better than the bad guys?

my body to carry on filming. had to concentrate on being journalist.” He had been filled with optimism the first time that he “embedded” with the Emergency Response Division, unit under Iraq’s interior ministry, as it rooted out insurgents in the city of Fallujah last year. One of its commanders was Sunni, the other Shi’ite, and they were close friends. Arkady regarded this as story of hope, an example of how the country might overcome the sectarian violence that has bathed it in blood since the American-led intervention against Saddam in 2003. “They were heroes to

Ali Arkady (b. 1982, Iraq) is an artist, photographer, and filmmaker. In 2017, Arkady had to flee Iraq with his family when his life was threatened after he photographed Iraqi armed forces committing war crimes. He sought refuge in Europe, where he was granted asylum and subsequently built a new life. His photographs of war crimes in Iraq were published worldwide by international media and put pressure on the Iraqi government to acknowledge the crimes committed by their soldiers. For this work, Arkady won the prestigious Bayeux Calvados-Normandy Award for War Correspondents in 2017 and the Free Press Unlimited Most Resilient Journalist Award in 2019 for his exceptional courage and persistence. Now an educator and mentor, he counsels young journalists from troubled parts of the world on staying safe while reporting stories that threaten to upend their lives as his was.

kicking his legs as he suffocated.”

that occasion Arkady watched in silent horror, too shocked to take pictures.

‘heroes’ were doing things that would never have believed possible,” he says.

decided to go

against

for

and the entreaties of his

he returned to

wanted him to be

in

front.

The nightmare intensified. By late November, soldiers had recaptured the village of Qabr Al-Abd from Isis and several young men were arrested. Arkady took pictures of them, only to hear later that they too had been executed.

“Far from ‘heroes’, they were sadistic torturers, rapists and killers making a mockery of Geneva conventions”

Civilians began pouring out of former Isis territory, including dozens of men. Among them was Mahdi Mahmoud, farmer, and his 16-year-old son, who was suspected of belonging to Isis. When Arkady walked into the interrogation room he saw Mahmoud hanging from the ceiling with his arms extended behind him, his back weighed down with pallet of water bottles as the soldiers beat him. Arkady took photographs and recorded video. “Nobody tried to stop me.” Mahmoud’s son was being questioned next door — he was eventually killed. The father survived. “I thought to myself, ‘What is this you are doing? Filming torture? And why do they let me film it?’ He reached the conclusion that, for them, “it was just normal” and that they had “lost all idea of right and wrong”. In any case, they did not expect Arkady to publish his footage. “So said to myself, ‘You must carry on.’ Foreign correspondents were covering fighting in the area but would follow Iraqi forces only by day. By night, Arkady was left alone with them to chronicle crimes, accompanying them on raids of civilian homes. The soldiers were constantly looking for money to steal and pretty women to

“It was clear that my life would be in danger as soon as I published evidence of these war crimes”

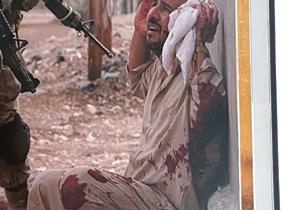

Over many months, the photographer Ali Arkady bore witness to the brutality of our allies in Iraq. Now, as victory is declared over Isis in Mosul, he risks his life to reveal the truth Matthew Campbell reports INHUMAN TREATMENT shepherd whose son had fought for Isis is tortured by the Iraqi military during operations in Mosul, 2016 The Sunday Times Magazine 15 The Sunday Times Magazine One man hangs from the ceiling, arms stretched at an impossible angle behind him, moaning in agony. Another kneels in the sand, then leaps up, trying to flee, begging for his life. Two men run after him, shooting. He falls, his body twitching at each bullet. The video looks like the handiwork of Isis, which relishes posting horrors online. What makes these atrocities even more shocking that they were carried out not by the bearded extremists of the caliphate but by the Iraqi government’s Americantrained security forces. Ali Arkady, prizewinning Kurdish photographer, has risked his life by publishing what amounts to evidence of war crimes by our allies in the fight against terror. “It is important for the world to see what they are doing. want to stop them doing more of it,” says Arkady in an interview with The Sunday Times after fleeing Iraq with his wife and daughter. He in Europe but did not want us to say where: wanted man in his homeland, he has received death threats since smuggling his photos out of the country. A compact, diminutive figure with melancholic eyes and gentle smile, Arkady, 36, has lived his whole life in the shadow of war. One of his earliest memories is of dog eating body on street in Khanaqin, his home town in northeastern Iraq, during the dictator Saddam Hussein’s savage campaign against Kurds. But Iraq’s latest, bloody convulsions and the scenes Arkady chronicled as photographer have left greater mark on his soul. On two occasions, he was compelled to participate in beatings of prisoners, crossing the line from observer to unwilling accomplice — “a very, very bad thing”, he admits, that has left him consumed by guilt over how his sense of morality was drowned by the will to survive. He watched as prisoners he believes to have been innocent were cut with knives, suffocated with plastic bags or hanged by their arms from the ceiling as interrogators screamed at them to confess their allegiance to Isis. “I will never get the images out of my mind,” says Arkady, speaking at the home of friends. “Each day, the camera felt heavier and heavier in my hand. By the end, could barely hold it. had to take my heart out of

me,” Arkady says. “I thought that maybe these two would heal all the divisions between Sunni and Shia.” He set up a Facebook page called — with touch of irony — “Happy Baghdad” and posted short video on about the two officers, entitled “liberators not destroyers”. Captain Omar Nazar, the Sunni, and Sergeant Haider Sada, the Shi’ite, were thrilled by this unusually positive attention. In October last year, they invited Arkady to join them on the front line in the northern city of Mosul. But as the trusted photographer gained more access to the soldiers and their daily routine, darker narrative emerged: far from “heroes”, the officers he had befriended were sadistic torturers, rapists and killers who made mockery of the Geneva conventions. As government forces tightened the noose around the Islamic State’s last Iraqi enclave, another of the commanders, Captain Thamer Al-Douri, confided in him that he had personally executed many prisoners. “He told me that at first he would shoot them in the arms and legs,” Arkady says. “But after his brother, who was also soldier, was killed in fighting, he started to kill.” He invited Arkady to watch him dispatching prisoners — the photographer declined. Then, one day, Al-Douri summoned Arkady to witness him questioning young suspected Isis member called Ali. He placed plastic bag over his head and beat him repeatedly, commanding him to proclaim the Isis oath of allegiance. Arkady was handed Al-Douri’s mobile phone to provide light from the torch app. “The young man kept saying he didn’t know the oath of allegiance, then the plastic bag went back over his head. He was

On

“My

He

home

break. Then,

all his instincts

father, who never

photographer,

the

“There was this voice

my head telling me had to go back even did not want to. wanted to document the fight against the Islamic State, the biggest story in Iraq.”

in cold blood An execution, above, captured on an raqi soldier’s phone. A mother pleads in vain for troops to release her son, below no mercy The shocking moment suspect is stabbed behind the ear — technique apparently learnt from US troops The Sunday Times Magazine 16 The Sunday Times Magazine rape. On one occasion, captain arrested a man and then told the wife that he would be killed unless she promised “to do something” with him. She agreed. But by then, her husband was already dead. Men, too, were raped, according to Arkady. In December, he photographed the torture of two young brothers whom he believes had nothing to do with Isis. They were beaten. Then soldier stabbed one of them repeatedly behind the ear with knife: he boasted that was a technique he had learnt from American “experts”. Another soldier shoved his finger into one of the man’s eyes. In the morning, soldier told Arkady that the brothers had been tortured to death and showed him a video of their bodies. Arkady asked for a copy, which the soldier sent to him on WhatsApp. Another video showed the kneeling man and his futile attempt to flee. To Arkady’s disgust, the executioners turned out to be Nazar and Sada. As things degenerated, the soldiers asked Arkady to join in the torture. “They were torturing guy in the kitchen. Sada tells me, ‘Everyone hitting him, but you are not — hit him!” Arkady replied that he was journalist, not a soldier: “I can shoot pictures but not hit people.” Sada glowered in silence at Arkady. “I was afraid. thought maybe he would ask me if was on their side or not. I had seen lot of things already. was in a dangerous situation. slapped the guy. Not very hard. Sada was very happy. felt better.” The same thing happened on another occasion. “I don’t like what did. And if the same thing happened again, like to think that now would say no. just want to be honest about everything that happened.” With people being brutalised and butchered each day, Arkady had come to feel only provisionally alive, with the sense that he too could fall victim to the killers at any moment. This feeling was reinforced one evening as he was photographing soldier dragging suspects off the back of truck. The soldier saw him and, putting pistol against his head, asked him what he was doing. “I thought he was going to kill me,” Arkady recalls. “I said, ‘I’m with Omar [Nazar]!” Nazar was sitting in car a few feet away, watching. But he said nothing. The soldier eventually let him go. But Arkady realised it was time to get out. “I told them had to get home because my daughter was ill,” he recalls. He left Iraq. “It was clear that my life would be in danger as soon as published the evidence of these war crimes.” His wife, an arts student, carried single suitcase out of the country and his four-year-old daughter took just one toy. A rkady had always wanted to be an artist, like his father. But when he got his first digital camera in 2006, another passion took over. After graduating in 2010, his photographs began to attract attention. He exhibited his work in Dubai, Georgia and Germany. He got assignments with NGOs, including the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees; and in 2014 he was among five photographers selected out of 150 applicants by the VII Photo agency’s mentor programme for new talents. He began working for foreign publications including Der Spiegel in Germany to Le Monde in France. He talks nostalgically about the days when he exhibited pictures of his home town at gallery in Baghdad — now he has achieved renown for much darker fare. The images he published in May prompted fury in Iraq, which accused him of being a thief and liar who had fabricated evidence, encouraging soldiers to stage mock torture sessions. But Arkady insists: “It’s all real, all my work is real. Nobody can seriously

fear and loathing troops from the emergency esponse division crowd around to intimidate their captive dark times scenes reminiscent of sis videos, blindfolded prisoner is filmed, above. a gag used to muffle the screams, below © ALI ARKADY

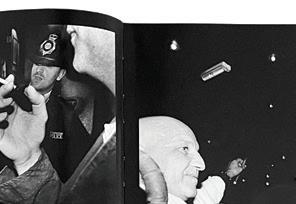

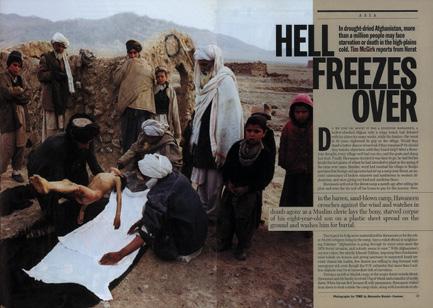

Mahdi Mahmud is hung by rope from the roof of the hallway by the Iraqi Reconnaissance Unit as part of his torture and interrogation. Mahdi Mahmoud was displaced from Mosul with his family to his village. He and his 16-year-old son Ahmad were arrested upon arrival. They were tortured for more than an hour and later released. Two weeks later, Ali Arkady was told that the Intelligence Regiment arrested Ahmad Mahdi and executed him with a group of detainees near Qabr al-Abd village, Hammam al-Alil, South Mosul. Iraq, November 23, 2016.

Mahdi Mahmud is hung by rope from the roof of the hallway by the Iraqi Reconnaissance Unit as part of his torture and interrogation. Mahdi Mahmoud was displaced from Mosul with his family to his village. He and his 16-year-old son Ahmad were arrested upon arrival. They were tortured for more than an hour and later released. Two weeks later, Ali Arkady was told that the Intelligence Regiment arrested Ahmad Mahdi and executed him with a group of detainees near Qabr al-Abd village, Hammam al-Alil, South Mosul. Iraq, November 23, 2016.

ANUSH BABAJANYAN TROUBLED HOME

In November 2020, a few days after the ceasefire that ended what came to be known as the 44-Day War, I was driving with a friend towards Stepanakert, the capital of Nagorno-Karabakh. We were chatting and processing the events of the recent days, but it was mostly a calm ride. Suddenly the mood shifted. My friend began talking about his devotion to the Armenian people and our land. With increasing emotion, he spoke about those who love and serve their country, and those who do not; about patriotism. I told him that in all these years that I had been returning to Nagorno-Karabakh, patriotism was never the reason. It was partly because Armenians, like me, live there. But there was also a straightforward and clear knowledge that I had to do it, that the story of this place and its people had not been told enough, and that wanted to tell it.

During those few days and in the aftermath, covered stories in Stepanakert, Martakert, Mataghis and Herher. I was struck by how familiar this place was to me, yet still so unknown. On the second day, we got to Martakert through a dense fog and stopped by a military post at the entrance to the town. After a short conversation with the soldiers there, we heard an order to take cover in the trenches. I ended up sitting for several minutes across from two soldiers: a young conscript named Harut and an older lieutenant named Vahe. The three of us did not talk, but listened to the distant shelling as I photographed them waiting and smoking. They had a particular look in their eyes and would see the same gaze in the eyes of many in the following years. It spoke of determination and of living in this particular moment. But most of all, I felt a question in their gaze. I think it mostly began with “why.”

As an impressionable young exchange student, Anush Babajanyan (b. 1983, Armenia) was given her first camera by her host mother in the United States when she was in high school. Documenting her year abroad evolved into photographing her homeland of Armenia, expanded into Central Asia, and eventually took her across the world. Focusing on the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict in Autumn 2020 and its aftermath on her doorstep, Anush has also been working on an environmental project on water in Central Asia, for which she won a World Press Photo award this year.

The disputed region of Nagorno-Karabakh, known as Artsakh to Armenians, has seen decades of conflict, with fighting between Armenian and Azerbaijani forces. In 1994, after six years of war, a ceasefire was reached, but violence continued along the line of contact between the unrecognized republic of NagornoKarabakh, populated by ethnic Armenians, and Azerbaijan. Until the autumn of 2020, the largest escalation was the Four-Day War that took place in April 2016.

The first time traveled to Nagorno-Karabakh for work was during this conflict. On April 2, the night before left, I paced back and forth outside our home in the suburbs of Yerevan. I hadn’t told anyone about my plan to go. Somehow, I was alone in this. I called an Armenian editor to ask whether he needed a photographer and felt comforted when he told me he was already there, and to call him when got there. But on that trip, and on most of my subsequent trips to the region, going alone has allowed me to fully immerse myself in the place and the people I meet. cherish the beautiful, meditative six-hour drive.

On one of these drives, it occurred to me that did not grow up in Artsakh, but grew up with it. In the late 1980s, I remember riding in a bus with my mom past Freedom Square in Yerevan, which was packed with people calling for the reunification of NagornoKarabakh with Armenia. They were chanting, “Miatsum!” (“Unite!”). During the First Karabakh War, which overlapped with the fall of the Soviet Union, we went for years without regular heating or electricity. As a child, knew that this had something to do with resources being directed towards the war.

On that trip in April 2016, was not particularly afraid. have come to realize that if I do not know something, do not know how to fear it. And I did not know war, not directly. I was naturally worried about leaving my children (then four and seven), but I had a definite feeling that this was my job to do. My country was at war. was not a war photographer, but Artsakh was an exception. I grew up with it.

After the war, I shifted quite intuitively towards working with mothers and large families. In a way, was pursuing my own “why.” I often think about the ways in which motherhood has shaped my career, both in its limits and its expansiveness. Motherhood has given me access to a deeper level of emotion, and I find that emotion when am working with parents in Artsakh.

To encourage population growth, the government of the Republic of Artsakh has introduced certain policies, such as providing a home to families after the birth of their fifth or sixth child. would devote most of my subsequent trips to visiting these families, returning to them over the years and documenting their lives.

The Ayaryans in Martakert are one of the first families I met. Eduard and Susanna are a strong parenting couple, and their children are especially warm and welcoming. During one of my trips, we climbed a hill above Martakert together, staying there and feeling the beauty until it got dark.

I also spent a lot of time with the Babayans in Stepanakert. We met in 2017 and continued to work together in the following years, during and after the 2020 war. Liana and Gegham had nine children when I met them, and in August 2017, I photographed Liana in the Stepanakert maternity hospital where their tenth child, Movses, was born. Gegham is a religious man, both loving and strict with his children. They have managed to keep things together so well with all their kids through these turbulent years.

Now, at the beginning of 2022, the situation in Nagorno-Karabakh is still unclear. I return when I can, always running along the edge between the familiar and the unknown. Each of my trips to this land has brought me closer to the known.

Anush Babajanyan, excerpt from A Troubled Home, February 2022

© JOHN STANMAYER

The ruined auditorium of the House of Culture in Shushi. It was shelled in the first days of October 2020, during the 44-Day War in Nagorno-Karabakh. Shushi, Nagorno-Karabakh, October 16, 2020.

The ruined auditorium of the House of Culture in Shushi. It was shelled in the first days of October 2020, during the 44-Day War in Nagorno-Karabakh. Shushi, Nagorno-Karabakh, October 16, 2020.

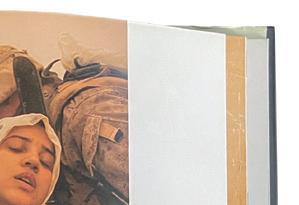

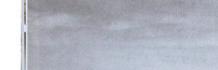

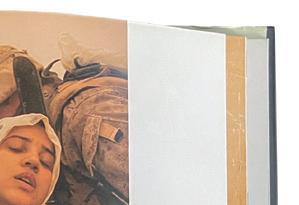

ASHLEY GILBERTSON WHISKEY TANGO FOXTROT

Ashley Gilbertson (b. 1978, Australia) arrived in Iraq in 2002, a year before the US invasion, with no job and no assignments, and stayed there until 2008. Ashley photographed the occupation in its darkest and most violent moments as Iraq descended into unimaginable chaos. He made some of the most iconic images of the war; he also made some of the most ironic. The photograph in this exhibition is drawn from the euphemistically named monograph Whiskey Tango Foxtrot.

War, the old saying goes, is seven parts boredom and one part terror. A soldier mans a post for hours on end, with only the crickets to liven his night. Life in the village carries on, the distant armies no more troubling than the clouds on the horizon. Then, in a flash, all is changed: lives are upended, bodies wrecked, futures destroyed.

But the old formula, while true in a sense, misses war’s most singular aspect: its ability to evoke a wider range of human experiences than any other human endeavor. Heroism, cowardice, joy, deceit, brotherhood, violent death. A nineteen-yearold from upstate New York discovers an unknown capacity for courage as he pulls a fallen comrade from a mosque. A young Iraqi woman feels her life dissolve as she cradles her blinded son. All in an afternoon, all in a flash.

War may be a peculiar mix of boredom and terror, but within those horrifying moments lies the whole galaxy of the human condition.

The photographs displayed here depict the full range of human experience called up by the war in Iraq. Ashley Gilbertson, a gifted and fearless photographer, has plunged into this darkest and most ferocious of battlegrounds and found beauty and horror and honor and truth. Scan the faces captured in these pages, of Iraqis and Americans, and of the predicaments they have found themselves in, and see and feel — in your gut — what it really means to be a human being in the middle of a place as tormented and dynamic as Iraq is today.

Dexter Filkins, from the introduction to Whiskey Tango Foxtrot, 2007

© AVA PELLOR

A U.S.

Marine slides down the marble handrail in Saddam Hussein’s extravagant palace built in his hometown of Tikrit. The enormous Palace contained rugs and antiquities worth hundreds of thousands of dollars before being looted by Iraqis and U.S. soldiers. Tikrit, Iraq, 2003.

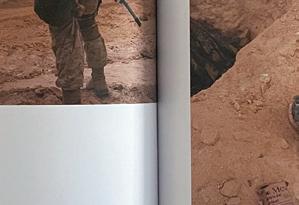

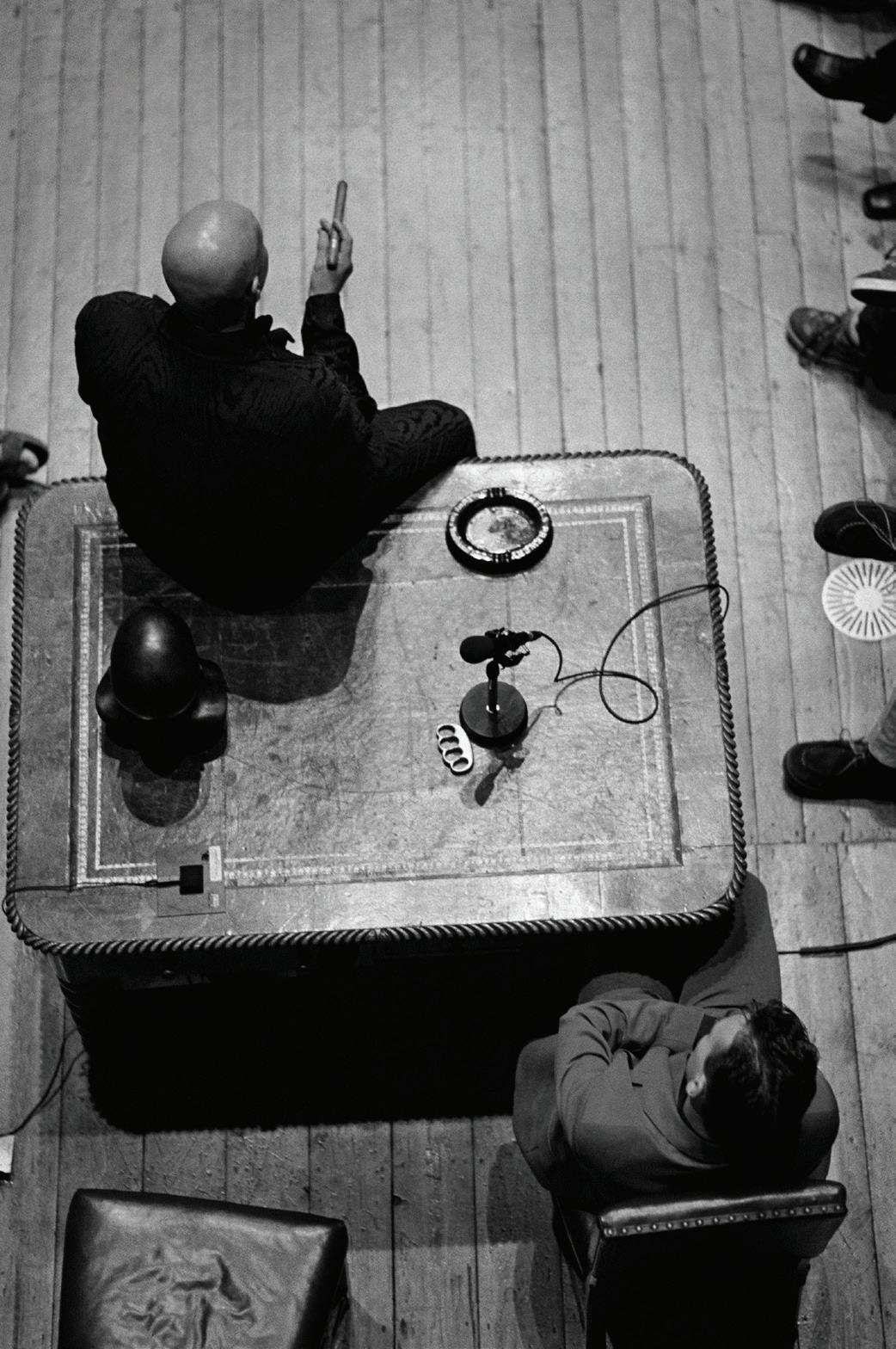

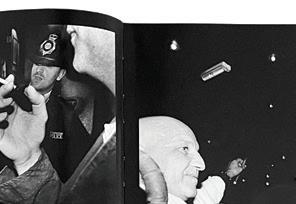

CHRISTOPHER MORRIS ON CHECHNYA

Christopher Morris (b. 1958, USA) is one of the most influential photographers of the 20th century and one of the most celebrated visual chroniclers of war. Morris re-invented and reimagined what was possible with the language of political photography for a generation of photographers and editors while working for TIME magazine during the George W. Bush Administration in the United States, but his colleagues hold him in the highest regard for his visceral and poetic war photography. His career, however, has defied the narrow confines of conflict and politics. An Italian fashion magazine commissioned him after seeing his photographs of Republicans in America, and that led to further work with celebrities and world leaders eager to receive similar unorthodox photographic treatment.

© CHRISTOPHER MORRIS

© CHRISTOPHER MORRIS

A Chechen fighter escapes out the front door of the Presidential Palace. He has a long and exposed run out in the open until he can reach cover. Grozny, Chechnya, January 1995.

A Chechen fighter escapes out the front door of the Presidential Palace. He has a long and exposed run out in the open until he can reach cover. Grozny, Chechnya, January 1995.

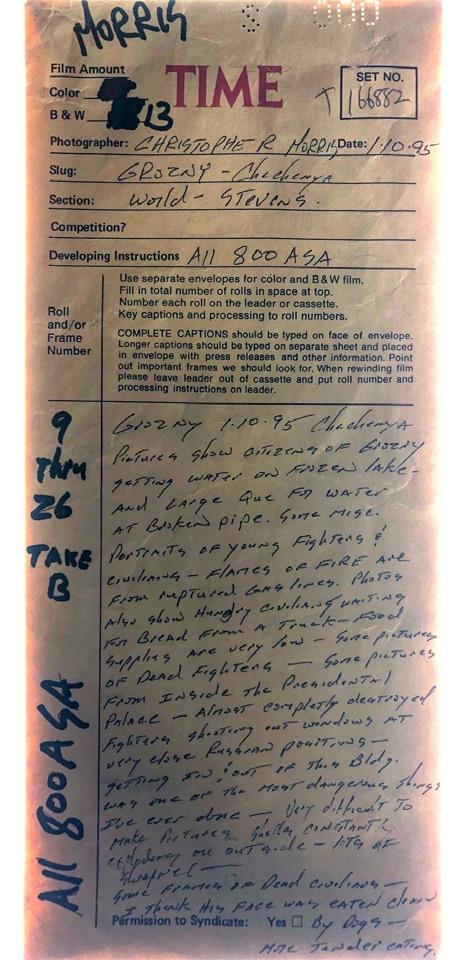

DANIEL SCHWARTZ

THE GREAT WALL OF CHINA (1987-1988)

Daniel Schwartz (b. 1955, Switzerland) is an enigmatic photographer, documentarian, and artist, and the author of six monographs, including a personal record of his Central Asian travels that incorporates an account of 3,000 years of the region’s history. A prodigious reader and researcher, his photographic projects are driven by rigorous study, disciplined control of craft and technique, and ascetic and monastic practices seemingly at odds with the outcomes, which are spontaneous, responsive, and ephemeral.

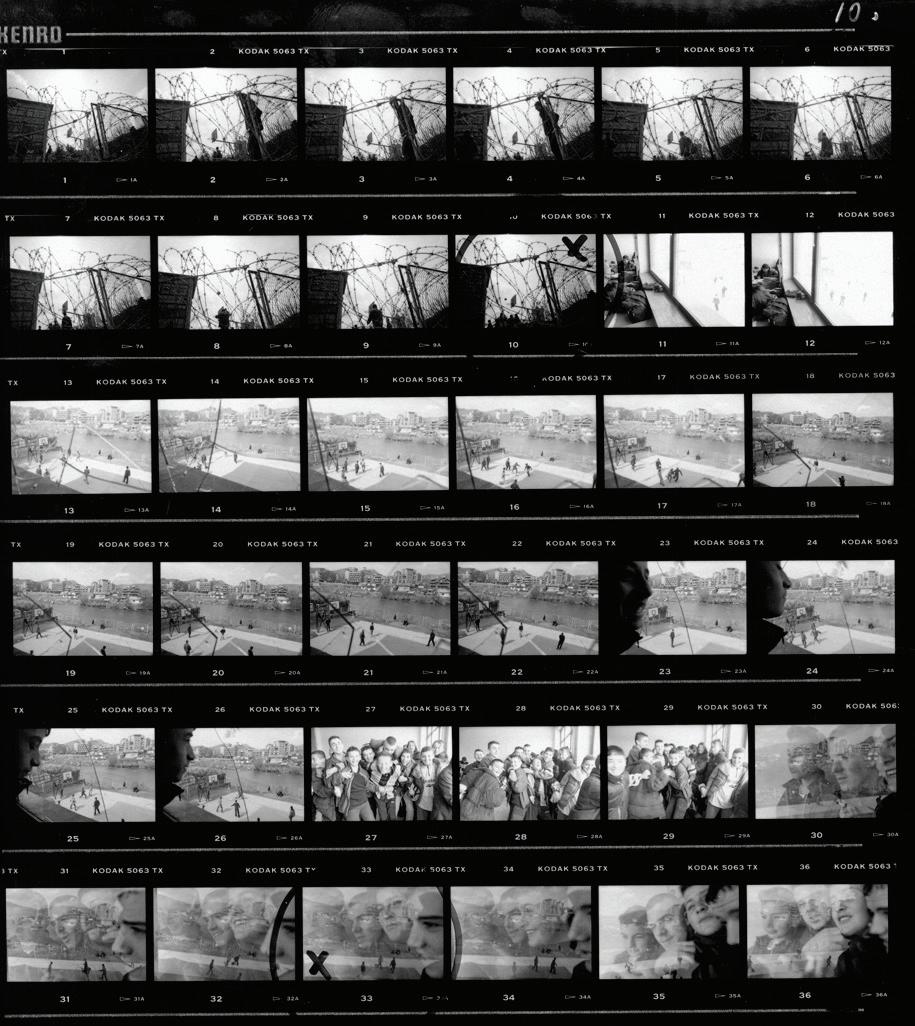

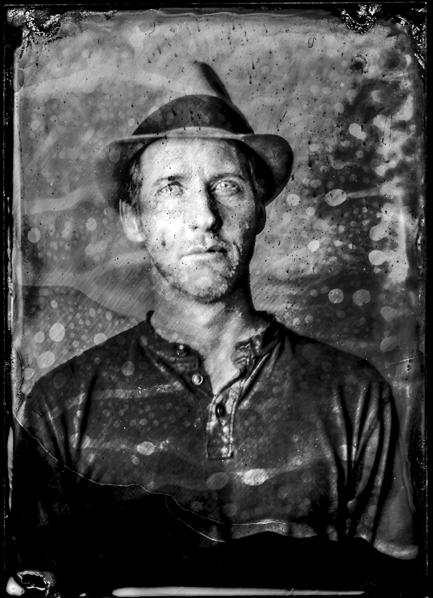

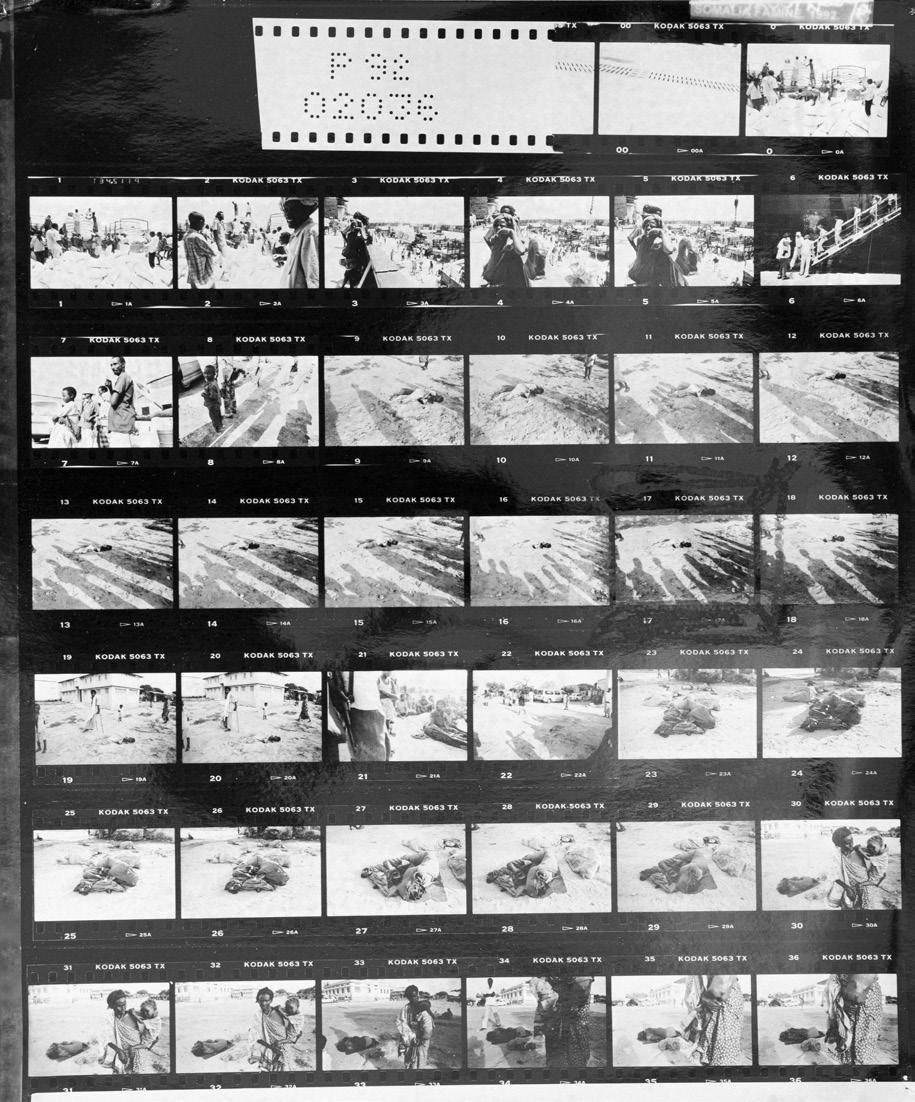

The “masked coal worker” (negative PRC87/2-351.7) became an iconic image, but not because wanted it to be. The photograph is part of a series taken during my forbidden journey along the Great Wall of China in 1987-1988, and in 1988 it was chosen as key visual for the Rencontres Internationales de la photographie d’Arles. I did not go to Arles then, but I was told that the poster with the photograph was everywhere. The masked coal worker and other portraits were my contribution to the collective exhibition Chine, shown in the Commanderie Sainte-Luce. The exhibition print and four other copies sent to the Rencontres’ publicity agency in Paris for the festival’s promotion materials were never returned. So I had to make replacement copies for a solo exhibition that toured Europe in 1990-1991. The print included in the VII exhibition See Through the Noise is one of them.

Between 2018 and 2020, undertook an archive research project in view of the exhibition Tracings (Museum of Art, Lucerne, Switzerland, September 30, 2023 – February 4, 2024), as well as toward the forthcoming book Tracings: Photography and Thought (Thames & Hudson). In that context, I made a final edit of the coal photographs created in November 1987 in the sprawling mining district of Datong, Shanxi province, at the heart of which lies the Yungang Buddhist cave complex.

The edit, titled Undermining Buddha, consists of a series of 24 gelatin silver prints, some of them multi-exposure composite prints. It brought to Iight a frame (negative PRC87/2-351.9) that had actually never looked at — the frame that directly follows the “iconic” image. That frame, No. 7, had fulfilled all the criteria important for me back then, and its subsequent selection by the Rencontres as a key visual had seemed further proof of its quality. Since then, the only copy of the 1988 poster that I have hangs in my darkroom. That photograph had acquired its own life. But the blessing had become somewhat of a curse. was blind to the other 11 of the roll film’s frames — with the exception of No. 11, which I had included in a quadriptych with the “iconic” image and two frames from another film.

It is in the nature of the contact sheet that it provides the indisputable context of space and time of every frame captured, together with the realization that each exposure is a record of irretrievable loss. But if nothing remains the same after the moment of the exposure or disappears altogether, something, mechanically or unconsciously, may also be netted in a frame at the instant of its creation; something that emerges much later, and in retrospect appears to be still potent and declarative. It is the cognition that a most difficult but rewarding task for a photographer is the scrupulous review of one’s images with an unbiased and self-critical eye.

Emerging from the contact sheet 35 years after it was captured and printed, the solitary coal worker frame, No. 9, shows an assertive directness (precisely because the woman does not look at you), and it reveals a strength that the “iconic” image does not possess. On the other hand, its discovery did not take anything away from the mystery of the frame that had obtained a privileged place in my work in the first place. The masked smile still holds fond memories of miners and laborers working the loading stations, of donkey cart drivers and coal pickers, all of whom were engaged in incredibly hard and dangerous work; in stark contrast to bureaucrats and security officers, they had welcomed the young, somewhat intrepid foreign photographer. And by being so generous and letting him take their pictures, they allowed him to project himself in a romantic succession of John Thomson, whose Illustrations of China and Its People (Sampson Low, Marston, Low, and Searle; Vols. & II, 1873, Vols. III & IV, 1874) had been a great inspiration during his complicated journey along the Great Wall and which contains a sequence of plates depicting coal mining in the mighty Wu-Shan Gorge.

Daniel Schwartz, May 2023

© PHILIP BLENKINSOP

Daniel Schwartz, May 2023

© PHILIP BLENKINSOP

Coal worker, Yungang Yun loading station, Datong. Shanxi province, China, 20 November 1987.

Coal worker, Yungang Yun loading station, Datong. Shanxi province, China, 20 November 1987.

DANNY WILCOX FRAZIER LOST NATION

COWBOY JOHN: SUICIDE AND THE RURAL GHETTO

Ten years ago, lost thanks to GPS, I drove past a Minuteman ballistic missile site, down a long dirt driveway, and ended up on what Julie Long, John Neumann’s girlfriend, described as a “broke down horse and cattle ranch.” Eight straight years of drought brought me to the badlands of South Dakota, a region rooted in the romantic folklore of the American West. The Neumann Ranch took in all forms of drifters; the disenfranchised, dirt-poor, and mentally ill: veterans, addicts, criminals. No judgment from John; instead, welcome and whiskey. checked the box on several of John’s prerequisites.

John Neumann shot himself on June 9, 2019. He left behind a six-month-old son, Stetson, and fiancée, Tabatha Swartz. John is the cowboy under the busted pickup in my most well-known photograph from the Great Plains. John was proud of that image. It was recognition that his life, with all its rusty edges and broken bumpers, was also something beautiful.

Suicide is personal, part of my life since I was a teenager. Rural America is seeing a dramatic rise in suicides, the rate now 25% higher than in cities. Factors pushing the increase in rural communities include poverty, low income, underemployment, isolation, neglect, lack of access to mental health care, and the stigma that mental health treatment has in rural culture.

John suffered from ankylosing spondylitis, a chronic inflammatory disease where the immune system mistakenly attacks healthy joints. “John was always hurting because of his joints,” says Tabatha. John and Tabatha tried to get John to specialists who could help, but the waiting list was a year for the one doctor in their region. John was spending $600 a month for insurance so that he could receive medical care that was 12 months out of reach. “It was very physically painful for John, and he had tried different ways to control the pain, but we weren’t rich. John was just waiting, just waiting all the time, and he was tired of it,” Tabatha says. “There was no access to the care John needed. Maybe down the road [there would have been], but John didn’t wait long enough.”

Documentary photographer and filmmaker Danny Wilcox Frazier (b. 1970, USA) focuses his work on marginalized communities in and outside the United States. His work is centered on the Midwest and his home state of Iowa and is born from a commitment and love for his neighbors and community. He photographs people struggling to survive the economic shift that has devastated rural communities throughout the parts of America disparaged and misunderstood by so many in the USA and abroad.

With his photographs from Iowa, Frazier documented those individuals continuing to live traditional lives in rural communities across the state; people challenged economically but often unwavering in their conviction to stay. His work acknowledges isolation and neglect while also celebrating resilience, perseverance, and strength. Frazier is the director of the Daily Iowan Documentary Workshop and advises photographers and filmmakers at the University of Iowa’s independent college news organization, The Daily Iowan.

While trying to understand John’s death is a heartbreaking daily reality for Tabatha and all those who love John, there are many complex societal issues that led to his suicide.

In the remote communities surrounding the badlands of South Dakota, which includes the Neumann Ranch, access to health care and the money to pay for it are real barriers. The system failed John. “It was all about pain for the most part, physical and mental,” says Tabatha. “John’s body hurt so much, he didn’t want to be here.” Maybe if the care that John needed were readily available, his pain could have been managed. Maybe if our society valued access to health care for all, no matter wealth, race, or location, suicides like John’s would fall in number. Until we work together to find solutions for those outside of the ultra-wealthy ranks, the impact of wealth consolidation will continue to take loved ones, like John, from us all.

© JUSTIN MCKIE

Danny Wilcox Frazier, 2020

John Neumann works on an old pickup truck at Neumann Ranch, a place his girlfriend Julie Long calls a broken-down horse and cattle ranch. John took his life on June 9, 2019, in part due to the lack of medical care in his remote region on the Great Plains of the United States. Rural America is seeing a dramatic rise in suicides. Studies show that the rate of suicide in rural counties is 25 percent higher than major metropolitan areas. Cactus Flat, South Dakota, 2008.

John Neumann works on an old pickup truck at Neumann Ranch, a place his girlfriend Julie Long calls a broken-down horse and cattle ranch. John took his life on June 9, 2019, in part due to the lack of medical care in his remote region on the Great Plains of the United States. Rural America is seeing a dramatic rise in suicides. Studies show that the rate of suicide in rural counties is 25 percent higher than major metropolitan areas. Cactus Flat, South Dakota, 2008.

ED KASHI AGING IN AMERICA

for a world filled exclusively with leisure, was the first step toward blowing apart the traditional extended family. Decades after the first Florida migration, we are paying dearly for the price of Eden.

Of course, an age-segregated society is completely unnatural. It defies all the innate impulses of clan, family, hierarchy, and survival. That’s probably why as a society we are continually searching for ways to reinvent the social order and find alternatives to the traditional extended family. After several years of working on this project, it dawned on me that what Ed and were documenting wasn’t a series of isolated groundbreaking programs or individual life stories. We were witnessing the evolution of new communities that are evolving to meet the needs of the elderly. Whether it is foster families for senior citizens or geriatric wards in prisons, RV clubs for widows and widowers or multigenerational daycare centers, these situations are actually variations on the family portrait. They represent a reconfiguration of community.

With these extended years there is a huge range of experience, attitude and ability. Then there’s the health issue, separating the vital from the prone, self-sufficient from the dependent, the young-old from the old-old. These differences dictate which version of old each person inhabits and at what time.

A powerhouse of energy and creativity, Ed Kashi (b. 1957, USA) is a photojournalist and filmmaker dedicated to documenting the social and geopolitical issues that define our times. In addition to photography and filmmaking, Kashi is an educator and leading voice in photojournalism, documentary photography and visual storytelling. Together with his wife, Julie Winokur, he embarks on long-term projects that delve into questions that explore our essential humanity. “Aging in America” took eight years to complete, and resulted in a traveling exhibition, documentary film, website and book.

AGING IN AMERICA: THE YEARS AHEAD

We live in an age-segregated society. Teenagers leave home as early as possible, young families rear their children in relative isolation, and retirees seclude themselves in senior ghettos (albeit ghettos with golf courses and gatekeepers). The workplace is dominated by twenty-year-old techno-wizards who drive our race to the future, while retirement communities forbid grandchildren as permanent residents because they disrupt the pace of life.

Mobility, which is a uniquely American ethos, has sent us ricocheting from coast to coast, creating our own communities rather than being tethered to family, class, or tradition. As a result, we have chosen to leave our birth families behind, choosing instead to congregate with our peers. As a result, we have created a world where the generations inhabit separate, parallel universes, and rarely the twain shall meet. In fact, the generations have become so alienated that a journey into the world of our elders is like venturing through foreign territory.

Ed and I first became aware of this phenomenon when we had children. When our son was born, I realized I suffered from zero exposure to babies, and I joined the legions of modern women who read books to decipher motherhood. Then came the rude awakening that our previous social lives were banished to the realm of nostalgia. It quickly became apparent that we were also alienated from the universe of elders. We had no one over 50 in our immediate circle and we were sorely lacking mentors. Our children barely had any exposure to an entire generation, and every time we did interact with a man who had silver hair and wrinkles, our daughter would say, “Poppy,” the

name she calls her one surviving grandfather. In the meantime, across the country, my 77-year-old father had started spending winters with his girlfriend in Florida, where the only young people he interacted with were serving him meals or renting him irons.

Aging in America has taken us into what psychologist Mary Pipher calls “Another Country,” the world of our elders. We have charted this foreign landscape in an attempt to create a visual topography of its peaks and valleys. We have come to discover that it has its own look and feel, which is distinct from our middle-aged lives, and completely removed from America’s youth

culture. We have also tried to understand how the universe of our elders became so remote.

I used to blame youthful arrogance and selfishness for the disenfranchisement of our elders. I assumed that young people just weren’t willing to assume the responsibility of caring for their parents and grandparents, and this was a result of an alarming plague of disrespect. But have come to realize that our elders set the whole dynamic in motion. They are largely responsible for the way our culture has evolved. The advent of the retirement community, where elders choose to leave their offspring behind in exchange

Our lives have been altered by immersing ourselves in this work. It has taken a psychic toll at times, and then rewarded us tenfold by expanding our perceptions to include the whole life cycle, not just the part we inhabit or the youth-driven culture that confronts us daily. Unlike working in foreign countries, even impoverished or war-torn ones, this project has forced us to confront our own mortality every day. It has been a tutorial in how to live one’s life, and what to avoid.

Life comes. Life goes. And in between is this majestic arc of experience. We happen to be living at a time when the arc’s final curve has been given a graceful extension. We’re still struggling to figure out what to do with it. We hope that by sharing this work, we will be able to impart a greater acceptance for the aging process. Growing older is not the domain of the elderly; they don’t have a monopoly on this phase of life.

Aging in America is a celebration of individuals who have unique lives and fears, dreams and concerns. It is filled with personal histories that have brought these people to their own place in the pantheon of old age. Through these individual stories we are able to draw parallels to our own lives while peering through the window at universal themes.

Ultimately, our whole society is paying dearly for our elders’ independence. And when the time comes for them to seek assistance, which is happening in record numbers, their lives are so removed from the rest of us that it’s virtually impossible to close the gap. A large proportion of elders opt to be cared for by strangers rather than “burden” their own children, which would be unheard of in other cultures. On the other side of the scale, the baby boomers are grappling with the responsibility of aging parents, which conflicts directly with their careers and the demands of parenting their own children.

©

TOMAS VAN HOUTRYVE

Julie Winokur, excerpt from Aging in America, 2003

Maxine Peters, 90, passes away at home surrounded by her family, friends, and hospice aides, after a long battle with Parkinson’s Disease and dementia. In many parts of rural America people still live and die, the old-fashioned way. The Hospice Care Corporation, based in West Virginia, sends health workers into rural homes to make sure that people can meet a dignified end, surrounded by their families and loved ones. Gladesville, West Virginia, October 9, 2000.

Maxine Peters, 90, passes away at home surrounded by her family, friends, and hospice aides, after a long battle with Parkinson’s Disease and dementia. In many parts of rural America people still live and die, the old-fashioned way. The Hospice Care Corporation, based in West Virginia, sends health workers into rural homes to make sure that people can meet a dignified end, surrounded by their families and loved ones. Gladesville, West Virginia, October 9, 2000.

ERIC BOUVET UKRAINE: WAR DIARY

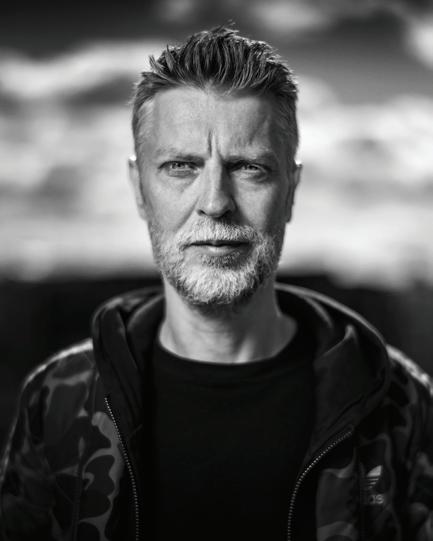

Eric Bouvet (b. 1961, France) lives and works on the edge. When he is not carrying 20kgs of 8x10 large format film cameras on his back to the highest Alpine peaks, he is a tireless photographer of conflict, social upheaval, politics, and culture. His photographic oeuvre is one of the most diverse in VII. Eric is a photographer’s photographer lauded by his colleagues for his courage, humanity, and humility for over 42 years in some of the most aggressive and violent territories, from the fall of the Berlin Wall to the war in Ukraine.

UKRAINE 2022 THE SHAME

The first scene, in the no-man’s-land between Poland and Ukraine, was left without image. How many are they? Hundreds of eyes peering through the mesh of fence topped with barbedwire. walk up this chain of frightened beings against the grain, first shock, incomprehension. The two guards accompanying me order me to keep moving without stopping. Without photos, there’s no proof, so we will have to do with words. Stacked together in the cold, they huddle together to keep some heat in the night that is about to lower its dark, icy curtain. They are not animals, just humans, but they were not born white, just black. Most of these African students, like everyone else, are fleeing war. Not just this war, but another one, that of their own country. But already the border guard, contemptuous, is saying to them: “Go get a gun and fight.” On the border, February 28.

THE EXODUS

Thousands are fleeing. Coming from all over, they are there, clumped together, carrying packages, suitcases, children, animals, pulling their parents and grandparents. The platforms are packed, and so are the trains. Mostly women, children, and the elderly, as men are no longer allowed to leave the country. Alone, many of them stand haggard on the platform, watching the train disappear into the distance, taking with it the promise of elsewhere for their loved ones. At the end of the platform, a man staring into the water murmurs, “This may be the last time I see him.” He has just left his child. Kyiv, March 5.

THE EVACUATION

Just two planks to leave hell. A thousand people from Irpin, Boutcha, and the surrounding area ventured, on foot, towards this long straight line, sometimes bombarded, sometimes under the yoke of snipers, to reach this life-saving passage. It is a narrow gully under the destroyed bridge over the river. Everything is black, an amalgam of soot, gunpowder, earth, dirt, concrete, and iron.

Dragged in blankets, carried at arm’s length, huddled in wheelbarrows, the old people from the hospice were evacuated thanks to the strength and courage of a few. The fear in their eyes cannot be described. A son carrying his mother shouts to anyone who would listen: “There are dead people everywhere.” Like the others, shocked by the sight of human misery all around me, I pay no attention to it. As it turned out, the man’s words were true. Irpin, March 6 to 10.

THE DISAPPEARANCE

Hanna will die this afternoon. She will leave behind a 14-yearold boy and two daughters aged 12 and 10. Yet that morning, her husband was still begging her to leave with their children. But Hanna doesn’t want to, for Olga, her mother, an old woman who can no longer walk. She cannot leave her, even though her block of flats, where the family lives in one shared room, is on the front line. An underprivileged neighborhood, a neighborhood where people tell you to “go where? Where to? Why? This is our home.” Olga has stayed in this flat, with her cat and her tears as her only company. The father, after burying his wife, fled with his children. Olga will shout before leave her: “My neighbors are accusing me of killing my daughter.” Irpin, Sunday, March 13.

A BREEZE OF FREEDOM

I meet up with a Ukrainian friend, Vasyl, who is leading a rescue team at the front. He takes me on board his convoy of over four hundred military personnel. We cross northwards in pursuit of the retreating Russian troops. As we pass through the villages, the convoy is greeted by shouts of joy, tears, and thanks. Inevitably, I am reminded of the images of the American liberators on the roads of France in 1944. I am the only one to witness this convoy of freedom. The soldier driving my vehicle had tears in his eyes: “I love my country, we’re going to win this war for the freedom of all these people.” Poroskoten, Friday, April 3.

THE HORROR

The pain of a mother who, a few days after burying her daughter, must comply with the instructions of the forensic police and attend her exhumation in order to undergo an autopsy. This is what it takes to document future war crimes trials. There are many men and women who have to recognize their loved ones by a piece of clothing, a piece of jewelry or a pair of shoes, buried in a hurry, some in a garden, some in a field. Tatiana was killed by a large-caliber shot fired from a tank positioned more than 500 meters away. After passing through two fences and the wall of her house, the child, crouching in a corner to protect herself, was mortally wounded. She was 10 years old. “I want all their children to be killed!” cried out the mother as she left the cemetery. Borodianka, Monday, May 2.

RESILIENCE

The Ukrainian army has just retaken the north of Kharkiv, on the eastern front, pushing the Russians back towards the border, some ten kilometers away. All that remains after their passage is a land of desolation. Villages bombed, looted. However, little by little, the inhabitants returned. They are even “happy” to be home again, even if the roofs have been ripped open and the walls are miraculously holding. They know, however, that the Russians may come back. There is no more running away. Despite the kidnappings of men of whom the villagers have no news, despite the daily bombings that sow random death, despite the thefts, despite the crimes, despite the rapes. They sit in the sun, serene. This exasperates a young army lieutenant: “Can you believe it, they’re coming back under the bombs to pick up their fucking potatoes...” Prudyanka, north of Karkhiv, Friday, May 13.

Eric Bouvet, diary extracts, Ukraine, 2022

ans, repris armes. Arrivé février non loin d’Irpin, une banlieue de capitale. est d’engagés volontaires. suis leur entraînement express. Lors demande accompagner refuse. Les journalistes sont pas accéder aux combats. Cela

ALviv, plus grande ville l’ouest pays, toutes vêtements provenance de Pologne, transitent par centre heures sur 24, jours bibliothèque municipale, confection. gigantesques métiers tisser servent confectionner filets de combat. Les petites mains résistance airent tous classes d’âge, leurs fascinant voir peuple qu dresse pour défendre liberté faisant bloc derrière Zelensky. disent plupart citoyens recouvertes d’un monticule de leurs courses, promènent leur Ceux des quartiers plus © CERISE BOUVET

BORODIANKA, police criminelle

peut s’assimiler censure. décide donc raconter frontière avec Pologne, une beaucoup réfugiés partent gare de Kyiv. Là-bas, foule, bousculade panique. Sur quais, très peu policiers, juste quelques contrôleurs qui pas surchargés. Certaines scènes sont déchirantes. père pose d’adieu. Depuis février, hommes 60 AIrpin, nord-ouest capitale, sur détruit tout début mars par Ukrainiens pour ralentir sont transportés brouette dans draps servant petite valise, voire un simple dos. Leur enfant sous bras, millions de réfugiés franchie. L’exode plus n’est pas fini.

pas les moyens partir. puis, campagne, entend, au loin, les bruits guerre. les champs… Autant traces Des nuages de fumée noire obscurcissent l’horizon. Tueries, viols, saccages, crimes guerre… j’ai assisté l’humiliation publique trois hommes, ligotés poteaux, pantalons baissés sur chevilles. Début les premiers charniers sont découverts des centaines de corps de civils déterrés. Tout près, police nationale sont appelés par les habitants. Un cadavre va-vite, fond son jardin… Parfois, les familles doivent ellespour faire gagner du temps aux équipes d’investigation. raison d’une dizaine de rendez-vous par dépouilles, enroulées dans des simples couvertures, sont en état emportent, dans leurs véhicules, les corps morgue plus mort côtés, dans cercueil. Dignité solidarité. vie Depuis l’invasion russe, les Ukrainiens invitent médias qui est l’appellation russe.

Le 24 février, l’armée de Vladimir Poutine envahit l’Ukraine. Pour Polka, le photographe Eric Bouvet est retourné dans le pays où il couvert, en 2014, la révolution de Maïdan. Pendant plus de deux mois, il documenté les conséquences du plus important conflit en Europe depuis la Seconde Guerre mondiale. L’exode, les destructions, les crimes de guerre… mais aussi la mobilisation d’une population, civile et paramilitaire, engagée derrière son président. Un reportage sur les conditions de survie des Ukrainiens, à un moment où le front était inaccessible pour la presse. Reportage photo et texte Eric Bouvet pour Polka Magazine AUX ABORDS D’IRPIN, UKRAINE, LE 25 AVRIL. Le nouveau cimetière on l’appelle dans les environs, accueille de nombreuses tombes fraîches au milieu d’une forêt de pins. Photos Eric Bouvet VII pour Polka Magazine. Page suivante. GARE DE KYIV, Légende Dio repelist, nihici quatur, cullectam, sint seque cullectam, sint seq cullectam, sint cullectam, sint seq cullectam, sint par Parfois, les familles exhument elles-mêmes leur proche pour accélérer les investigations C première quarante carrière front. Dès que Poutine lancé son ensive l’Ukraine, pays. 2014, j’ai rencontré Kyiv* nombreux citoyens pro-européens se battaient informaticien nommé Vasyl. Aujourd’hui âgé

UKRAINE CARNET DE GUERRE

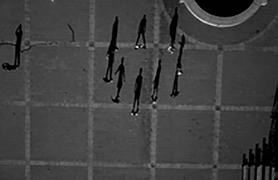

The new cemetery outside of the city in the middle of the woods. Irpin, Ukraine, April 25, 2022.

The new cemetery outside of the city in the middle of the woods. Irpin, Ukraine, April 25, 2022.

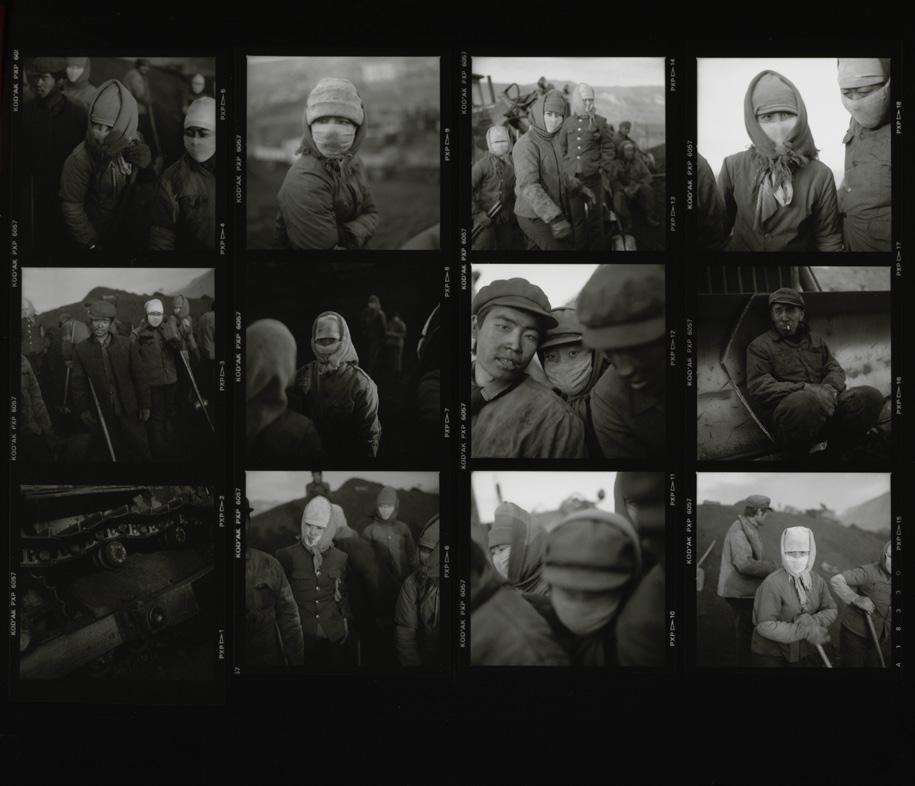

ESPEN RASMUSSEN EARTHQUAKE IN KASHMIR

Espen Rasmussen (b. 1976, Norway) grew up steeped in news — both of his parents worked for newspapers. When his mother worked the night shift at the local paper as a designer, his father, a reporter and editor, brought his children along to events that he had to cover live, like fires and other emergencies. In some ways, it was inevitable that Espen would become a journalist. He lives close to Oslo, Norway, and works as a photo editor and producer at the The Hub, the online magazine and long-format desk at Norway’s biggest newspaper VG, but his relatively placid desk job is punctuated by long stints abroad photographing and immersing himself in communities at the extremes of life: refugees struggling to survive across the globe for his project TRANSIT; workers grinding out an existence in the Rust Belt of the USA for Hard.Land; and violent right-wing extremists in America and Europe for White Rage.

Rasmussen lectures in photography at universities, frequently gives presentations at photo festivals, and appears before a wide range of other audiences.

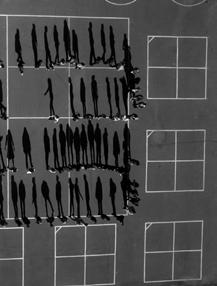

This image is important to me for many reasons. My report from Pakistan was one of the first international stories I did that really managed to break through the noise and reach a wider audience, in no small part with the help of the award in World Press Photo. It is also important for me because I think it shows a resistance and a will to survive in a situation that is almost impossible — most homes and infrastructure in this area were destroyed by the earthquake, but people managed to continue. This image, think, shows how important belief can be in people’s lives and in the wish to survive.

Espen Rasmussen, June 2023

© ESPEN RASMUSSEN

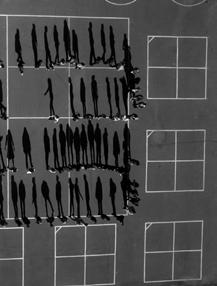

Over 3,000 people gather for Friday prayers at the ruins of the main mosque, one of the towns worst hit by the Kashmir earthquake. Three months after the October 2005 earthquake that devastated parts of Kashmir, hundreds of thousands of people were still homeless, many living in tents and collapsed buildings, facing icy winter conditions in the mountains. Balakot, Kashmir, January 27, 2006.

Over 3,000 people gather for Friday prayers at the ruins of the main mosque, one of the towns worst hit by the Kashmir earthquake. Three months after the October 2005 earthquake that devastated parts of Kashmir, hundreds of thousands of people were still homeless, many living in tents and collapsed buildings, facing icy winter conditions in the mountains. Balakot, Kashmir, January 27, 2006.

FRANCO PAGETTI VEILED ALEPPO

Franco Pagetti (b. 1950, Italy) started his celebrated professional life as a chemist and “accidentally,” in his words, became a fashion photographer after a friend asked him to work as her assistant. After working in fashion for Vogue and other magazines in Italy, in the late 1990’s he pivoted and focused on conflict, first in South Sudan and, shortly afterwards, Afghanistan, where he met Gary Knight, James Nachtwey, John Stanmeyer and Ron Haviv for the first time. He committed himself to documenting the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq with distinction and soon brought his colorful and charismatic personality to VII. He returned to the fashion world to work for Dolce & Gabbana at the behest of Domenico Dolce and worked on numerous high-profile campaigns. This work from Syria is imbued with the sensibilities of both his fashion and conflict photography; it’s where all the creative and cultural influences of his life in photography converge.

cleaning and drying into the bliss of wearing is, in such circumstances, almost inconceivable. In both instances the hung-out washing stands as a billboard advertising humankind’s amazing capacity for persistence.

Walking through the old neighborhoods of any city with decent weather, you suspect the sheets hung out to dry might be the unofficial national flags. Actually, the weather doesn’t even need to be half-decent. Nothing is so depressingly expressive of my native land (England) as the sight of laundry hanging out wetly for days on end, going from soaking to soggy to damp — and back to soaking without having achieved the mythical goal of dryness. And then there are cities where the air pollution is so bad that drying quickly turns into its near-anagram, dirtying. Escape from the samsara wash-cycle of

So they strike multiple chords, Franco Pagetti’s series of photographs from Syria, Veiled Aleppo, the sheets are no longer laundry at all. Perhaps they never were — and yet still they sway and blow as flimsy proof of the reliance of everyday life in the face of near-total ruination. The opposite of screens around a site where construction is in progress, these sheets demarcate areas of almost completed destruction. Their practical function is, presumably, to offer cover from sniper fire (the ever-present danger of which is suggested in one image by an advertisement featuring a row of painted eyes). The flimsiness of the protection is in striking contrast to the sturdiness of buildings and metal shutters — except that, in the face of the sustained onslaught of modern weaponry, concrete and steel are scarcely more resilient than cloth. The buildings are often reduced to bulky poles holding up the washing lines (which, I’m guessing, once served as phone or power lines).

Going back to the earlier mention of flats, it is a point of military honor never to lose or surrender the regimental standard or colors — but an immaculate flat is valued less highly than one that displays the price paid for its continued survival. Ideally the standard is reduced almost to rags as proof of valor, testament to sacrifices made in order to retain it. In some instances these ragged emblems are stained with the blood of those who

died preserving them. Moving from the martial to the domestic, bloodied sheets are sometimes displayed after a wedding night as twin proofs: that the bride was a virgin and that the marriage has been consummated. Our thoughts are urged in this direction by Pagetti’s deliberate use of the word “veiled,” hinting at both the lithe appeal of orientalist erotic fantasy — as in, the dance of the even veils — and the subordination of women that is an intractable feature of Islamic fundamentalism.

The difficulty posed by Syria for the United States is how to intervene and militarily support attempts to oust a dictator (and establish democracy) while not abetting that which is inimical to the continued progress of the species (militant Islam). The alternative — to do nothing — is, as the saying goes, to leave the rebelshanging out to dry. Amazingly, Pagetti’s pictures seem to illustrate this difficulty: at first glance the viewer could be forgiven for thinking that one of the pictures shows an improvised version of the Stars and Stripes. But it’s not, of course. It’s the stripes and stripes, the visual equivalent of being stuck between a rock — of which there is no shortage — and a hard place.

So perhaps these veils are best regarded as symbols of the pictures themselves, of the death throes not of a city but of film, of the days when prints and contacts — contact sheets — hung in the studio so that the photographer could see what had been captured or missed: evidence of things seen and unseen.

Geoff Dyer, “Franco Pagetti: Aleppo, Syria, 19 February 2013,” See/Saw: Looking at Photographs 2010-2020 (Graywolf Press 2021)

©

SARAH SHATZ

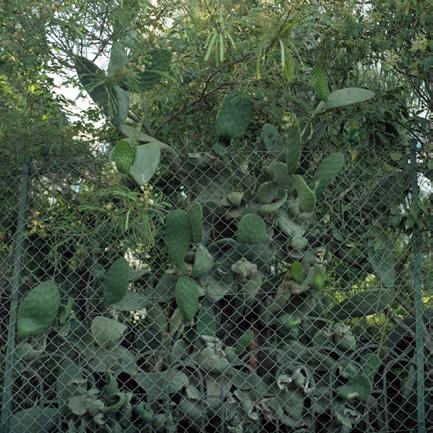

In the past, residents hung curtains to protect the family’s privacy, to protect the home from wind and sand storms, and to protect from the heat. Now the curtains protect them from Bashar Assad’s snipers, and are visible in all the frontlines in the city. Salah Aldin neighborhood front line, Aleppo, Syria, February 10, 2013.

In the past, residents hung curtains to protect the family’s privacy, to protect the home from wind and sand storms, and to protect from the heat. Now the curtains protect them from Bashar Assad’s snipers, and are visible in all the frontlines in the city. Salah Aldin neighborhood front line, Aleppo, Syria, February 10, 2013.

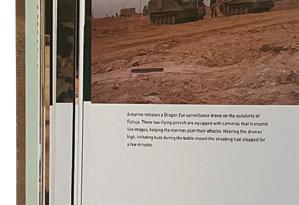

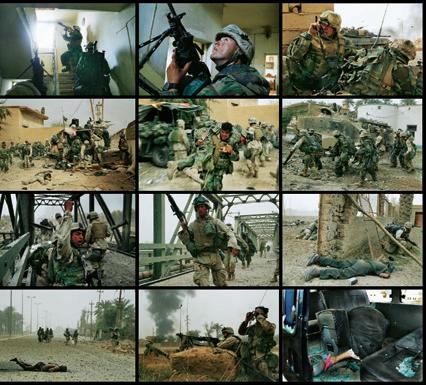

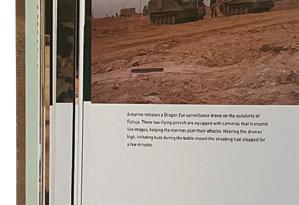

GARY KNIGHT INVASION: THE BATTLE FOR DYALA BRIDGE, IRAQ

An essay on war photography originally written by Geoff Dyer in response to the War/Photography exhibition curated by Anne Wilkes Tucker at the Museum of Fine Art, Houston in November 2012. Dyer has recently written a history of photography called See/Saw: Looking at Photographs 20102020 (Graywolf Press 2021). This essay is used with the kind permission of the author.

Susan Sontag’s book Regarding the Pain of Others concludes with a discussion of Jeff Wall’s huge photograph Dead Troops Talk (A Vision after an Ambush of a Red Army Patrol, near Moqor, Afghanistan, Winter, 1986). “Exemplary in its thoughtfulness and power”, this image of a “made-up event” was constructed in Wall’s studio. “The antithesis of a document”, the picture’s effectiveness derives, in other words, from the fact that it is a fiction.

But what effect does this have, in turn, on combat photographs that are documents? Are they diminished or enhanced by comparison with Wall’s mock-up?

Consider, for example, Peter van Agtmael’s well-known photograph of a line of US troops sheltering from the downdraft of a helicopter in a rocky grey landscape in Nuristan, Afghanistan, in 2007. Its compositional resemblance to Wall’s image suggests that the fictive can set a standard of artistic authenticity to which the real is obliged to aspire — and can still, accidentally, achieve. At the same time, its similarity to W. Eugene Smith’s shot of Marines sheltering from an explosion on Iwo Jima in 1945 testifies to its place in the heroic tradition of documentary photography.

situational terms he is the least important figure there; in every other way, he is the most important figure in the picture, its unavoidable focus.

The dead man is also the epicentre of the remarkable stillness of the picture, a stillness that emanates from and converges on him. (The slight blurring of the leg and foot of the soldier walking across the scene shows that a relatively slow shutter speed was enough to capture everyone else with near-perfect clarity.) There is a lot of activity — a lot going on and a lot to be done — but there is almost no movement. There is thus a kind of double stillness: the stunned stillness that comes after a battle and the stillness of oil painting, a stillness that does not stop time (as happens in fast-shutter-speed photography) but contains it. Oil paintings imaginatively recreate the swirl of action and battle with the steadiness of observation the painter would bring to bear on a still life (a bowl of fruit, say, or flowers). Photography can record actual combat but only with the kind of urgency and blur of Capa’s famous picture of a Republican soldier being killed in the Spanish Civil War or — for disputed reasons — his shots of the D-Day landings. Only in the aftermath of extreme violence can the twin strengths of photograph and oil painting be combined in this single extended moment.

It is not at all unusual for news photographs to echo the paintings of the past, either deliberately or accidentally. In 1967 John Berger famously pointed out the similarities between the photograph of the corpse of Che Guevara and Rembrandt’s painting of The Anatomy Lesson of Professor Tulip. A year later James Louw photographed Martin Luther King’s friends and associates on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, after he had been shot.

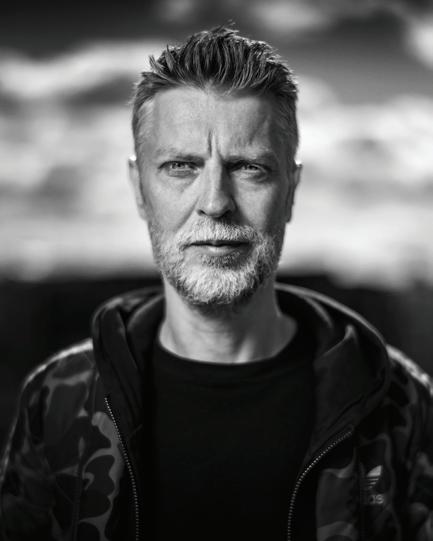

As an aspiring young photojournalist in South East Asia in the 1980’s, Gary Knight (b. 1964, UK) supplemented his meager picture sales by selling his own blood. In the Balkans, he developed his career working on the frontlines in that violent civil war, where he met lifelong friends Alexandra Boulat, Ron Haviv, Christopher Morris, and James Nachtwey, who, with Antonin Kratochvil and John Stanmeyer all became founding members of VII Photo Agency. Crisscrossing the globe for Newsweek and building networks everywhere, he saw the demise of the traditional photo agency model and the early signs of decline in print media. His determination and vision led to the creation of VII. As CEO of The VII Foundation and VII Academy, he leads a team which supports fiercely independent journalism and trains and mentors a new generation of journalists in the Majority World, who are best placed to tell their communities’ stories to the world.

April 7, 2003: 0430 wake up, pack the car, squeeze a foil envelope of peanut butter into my mouth, drink a mouthful of warm water, fold my laundry and drive to 20 yards short of the bridge.

An APC is parked on the left of the bridge, mortars on the right. Outgoing 155’s light up the palm grove on the north side of the river, mortars and machine guns take care of the residential area on the left. The usual cocktail of overwhelming firepower before an assault. I guess they are going for an infantry assault on the bridge sometime soon. see mortars on the right and wander over to take some photographs.

Iraqi 155’s walk towards our position, rows of exploding shells moving in a line until they land right on top of us, metal flying everywhere, confusion: incoming and outgoing, it all feels like incoming it’s so damned loud and so close. A Marine APC explodes 10 yards away; the turret flies in the air like a plastic toy. I run across the road through a cloud of dust and black diesel smoke. 2 dead Marines on the ground, the wounded crying for help. Marines not wounded swarm the area. The tension and anger rise. Enrico and I photograph.

Kilo and India companies start to move, run for the bridge, step over the dead boy covered in flies that Jack shot last night and span the holes in the floor with boards. Grunts charge the northern banks. Everyone is shouting, and bullets cut through the clouds of smoke and dust.

Iraqis in every possible death pose litter the street, fried to a crisp with their clothes burned off, rigor morticed, some intact

— delicately pierced by a sniper round or exploded and melon red, fresh, bleeding. The road is filled with shards of metal, and concrete from destroyed buildings — like a lava field it’s hard to walk without twisting your ankle. It’s quiet now and the pain and violence are overwhelming.

Shrapnel and concrete crunch underfoot as the Marines move house to house. An old grey-haired civilian is lying slumped with his head resting against the steering wheel of his truck, he looks like my grandfather Dick, the difference being that Dick died of a stroke and didn’t end up losing the back of his head. I imagine his wife waiting for him to return from work.

We reach the end of the block, bridgehead for the Division now secured. Kilo takes the open ground and digs into the dirt on the west side of the road, India is still moving through the palm grove on the east. Marine snipers take up positions on either side to hit anyone coming our way.

Heavy air strikes and artillery north of us, very close. A blue minivan approaches from that direction, the snipers fire warning shots, and it turns away. A white pickup approaches, the snipers kill the driver, a soldier in uniform, fair game. The blue minivan returns, the sniper’s fire warning shots but the grunts open up simultaneously with everything they have, the minivan bursts like a cherry, Captain Norton screams “Ceasefire — wait for the snipers” but it’s too late. Five civilians are bleeding to death, isolated.

Gary Knight, Journal entry, “Invasion: The Battle for Dyala Bridge”

It reminds us, also, that George Bernard Shaw’s appeal to photographic proof still holds good, in a battered and shop-worn (as opposed to photoshopped) sort of way, despite the challenge of digital. Shaw said that he would willingly exchange every painting of the crucified Christ for a single snapshot of Him on the cross. “That,” as Magnum photographer Philip Jones Griffiths insisted, “is what photography has got going for it.”

Or is this to miss an important point about Wall’s work, namely its relationship not to photography as traditionally conceived — as a kind of visual stenography — but to the imaginative ambition and reach of history painting? Sontag herself describes Wall’s intentions as “the imagining of war’s horrors (he cites Goya as an inspiration), as in nineteenth-century history painting and other forms of history-as-spectacle.” If van Agtmael’s photograph falls short of the epic scale of this ambition then we can turn to a picture taken by Gary Knight in Iraq in April, 2003. The photograph is actually part of a sequence recording the battle for Diyala Bridge. All of the pictures have the kind of immediacy we associate with photojournalism from Capa and Smith in the Second World War, to Larry Burrows and Don McCullin in Vietnam. Taken together they make up a visual narrative of combat and its aftermath with which we have become wrenchingly familiar. At its heart, however, is a single photograph that contains the larger story of which it is part.

Knight himself has provided a vivid account of the terrifying context in which the picture was made: “This was at the start of the invasion. We were at the Diyala Bridge, which had to be taken by the Marines so they could get into Baghdad. They were the lead battalion, the ones who went on to pull down the statue of Saddam. The opposition were shelling us. It was terrifying – both the actual shelling, and the anticipation of it. It comes in waves so you can see it moving in your direction. One had exploded in the tank. If it had landed on top or a couple of feet over, I would have died.”

In the dead centre of the picture a soldier is pointing — directing our attention — to the corpse that everyone else, with the possible exception of the soldier advancing towards the camera on the extreme left, seems determined to ignore. Understandably: in

It’s a picture of instantaneous journalistic and historic importance but the way three arms are raised, pointing in the direction of the presumed assassin — not, as in Knight’s Diyala Bridge picture, at the victim — mirrors the three brothers in Jacques-Louis David’s Oath of the Horatii (1784).

This, surely, was not in Louw’s mind at the time he took the picture. The parallels, however, are not merely visual. As art historian Hugh Honour writes in Neo-Classicism, David chose to depict “a moment not mentioned by any historian... in which the highest Roman virtues were crystallized in their finest and purest form. This was the moment of the oath when the three youths selflessly resolved to sacrifice their lives for their country.” Or, as King had put it in a speech the night before his assassination, “Like anybody, would like to live a long life. Longevity has its place. But I’m not concerned about that now. I just want to do God’s will.”

While the Louw picture instantly recalls David’s, Knight’s suggests a generalised memory of several paintings without quite superimposing itself on any one in particular. (The overall colour of the picture — a sandy, dusty, light brown that extends to and dulls the glow of the sky — is like the default hue of any numbers of paintings of atrocities, battles and assorted barbarisms in the middle-east: the Orient, as Delacroix and his contemporaries conceived it).

The centre foreground of Napoleon on the Battlefield of Eylau (1808) by David’s pupil Antoine-Jean Gros is dominated by a heap of corpses, around which the rest of the figures are arranged, but the fit is far from exact. Paintings of various scenes and battles from the American Civil War — Charles Prosper Sainton’s Pickett’s Charge, Battle of Gettysburg (1863), say — provide only rough templates. Knight’s Diyala Bridge photograph quotes from an actual event but not from an identifiable painting. It combines the documentary immediacy and evidential power of the best photojournalism with the epic grandeur of history painting.

Geoff Dyer, “The jarring reality and artful beauty of photography,” Los Angeles Times, April 20, 2013

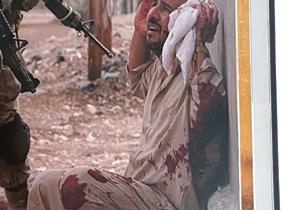

© ALIZÉ DE MAOULT

Lance Corporal Andrew Julian Aviles from the 3rd Battalion 4th Marines lies behind his destroyed Amtrak a few meters from Dyala Bridge. Our position had been subject to an intense artillery barrage, and a shell had entered the Amtrak through the top hatch. It killed Aviles and Corporal Jesus Medellin. Others were injured. Dyala Bridge, near Baghdad, Iraq, April 7, 2003.

Lance Corporal Andrew Julian Aviles from the 3rd Battalion 4th Marines lies behind his destroyed Amtrak a few meters from Dyala Bridge. Our position had been subject to an intense artillery barrage, and a shell had entered the Amtrak through the top hatch. It killed Aviles and Corporal Jesus Medellin. Others were injured. Dyala Bridge, near Baghdad, Iraq, April 7, 2003.

ILVY NJIOKIKTJIEN

BORN FREE

Ilvy Njiokiktjien (b. 1984, The Netherlands) is an independent photographer and multimedia journalist who has worked all over the world and spent twelve years returning regularly to South Africa for Born Free. She is drawn to stories that show the experiences of distinct communities or groups, in part due to her own unusual background: she spent her childhood living with her large family on a clipper — a merchant sailing ship — moored in Maarssen, the Netherlands, the daughter of a half-Chinese father and Dutch mother who rarely discussed their families’ immigrant heritage. Her own experiences of being somehow different to the then largely-homogenous Dutch community around her drives her to seek out the stories of both otherness and belonging in those she photographs.

JUST TWO PEOPLE CONNECTED