T HE V

T HE VA RSI T Y

Vol. CXLVI, No. 2

21 Sussex Avenue, Suite 306 Toronto, ON M5S 1J6 (416) 946-7600

thevarsity.ca thevarsitynewspaper @TheVarsity the.varsity the.varsity The Varsity

MASTHEAD

Medha Surajpal editor@thevarsity.ca

Editor-in-Chief

Chloe Weston creative@thevarsity.ca

Creative Director

Sophie Esther Ramsey managingexternal@thevarsity.ca

Managing Editor, External

Ozair Chaudhry managinginternal@thevarsity.ca

Managing Editor, Internal

Jake Takeuchi online@thevarsity.ca

Managing Online Editor

Nora Zolfaghari copy@thevarsity.ca

Senior Copy Editor

Callie Zhang deputysce@thevarsity.ca

Deputy Senior Copy Editor

Ella MacCormack news@thevarsity.ca

News Editor

Junia Alsinawi deputynews@thevarsity.ca

Deputy News Editor

Emma Dobrovnik assistantnews@thevarsity.ca

Assistant News Editor

Ahmed Hawamdeh opinion@thevarsity.ca

Opinion Editor

Medha Barath biz@thevarsity.ca

Business & Labour Editor

Shontia Sanders features@thevarsity.ca

Features Editor

Sofia Moniz arts@thevarsity.ca

Arts & Culture Editor

Ridhi Balani science@thevarsity.ca

Science Editor

Caroline Ho sports@thevarsity.ca

Sports Editor

Aksaamai Ormonbekova design@thevarsity.ca

Design Editor

Brennan Karunaratne design@thevarsity.ca

Design Editor

Kate Wang photos@thevarsity.ca

Photo Editor

Simona Agostino illustration@thevarsity.ca

Illustration Editor

Jennifer Song video@thevarsity.ca

Short-Form Video Editor

Emily Shen emilyshen@thevarsity.ca

Front End Web Developer

Sataphon Obra sataphon.ob@gmail.com

Back

Vacant utm@thevarsity.ca

UTM Bureau Chief

Vacant utsc@thevarsity.ca

UTSC Bureau Chief

Matthew Molinaro grad@thevarsity.ca Graduate Bureau Chief

Vacant publiceditor@thevarsity.ca

Raina Proulx-Sanyal

Cover: Chloe Weston

The Varsity acknowledges that our office is built on the traditional territory of several First Nations, including the Huron-Wendat, the Petun First Nations, the Seneca, and most recently, the Mississaugas of the Credit. Journalists have historically harmed Indigenous communities by overlooking their stories, contributing to stereotypes, and telling their stories without their input. Therefore, we make this acknowledgement as a starting point for our responsibility to tell those stories more accurately, critically, and in accordance with the wishes of Indigenous Peoples.

ANNUAL VIC BOOK SALE

Thousands of well-priced books across all subject areas

Location: In Old Vic, 91 Charles St. (Museum Subway Exit), Toronto

Dates & Times:

Thu Sept 18 – 2–7 PM (First day: Admission $5, Students free with ID)

Fri Sept 19 – 10 AM–7 PM

Sat Sept 20 – 11 AM–5 PM

Sun Sept 21 – 11 AM–5 PM

Mon Sept 22 – 10 AM–7 PM

Payment: Cash & cards accepted

Proceeds: Support Victoria University Library & Students

Contact: vic.booksale@utoronto.ca | tinyurl.com/vicbooksale

"Redrum"

Ashley Wong Varsity Contributor

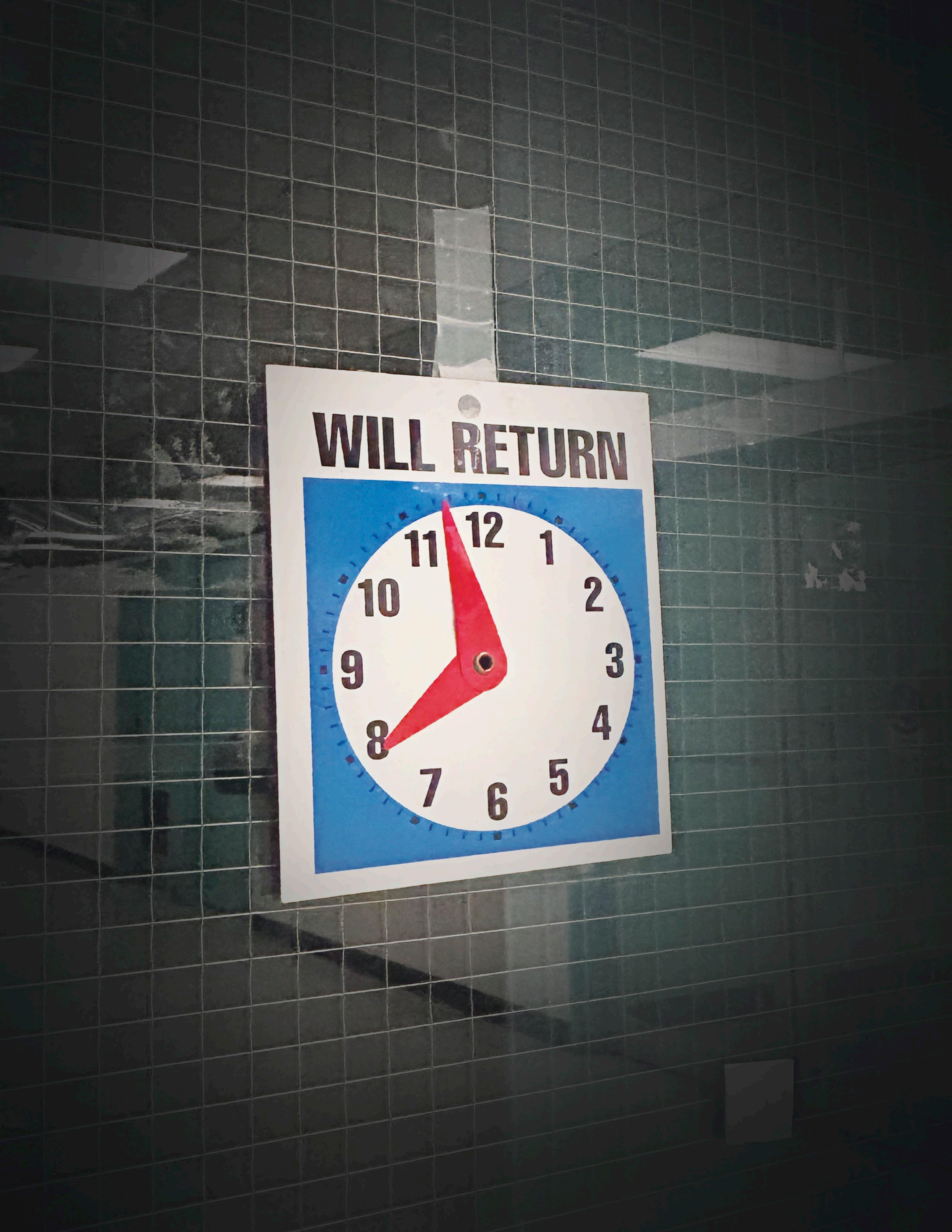

ACROSS

1. ______ Torrance (protagonist of The Shining)

5. City with an archipelago of artificial islands shaped like a palm tree

6. Take in

7. “______ Johnny!” (famous quote of 1-across)

8. Muscles worked on a “pull day,” for short

DOWN

1. Ancient Palestinian region

2. Cancel, as a mission

3. Accessories for Superman and Batman

4. DIY purchases

5. Author Roald of Matilda

Arif muznamars@thevarsity.ca

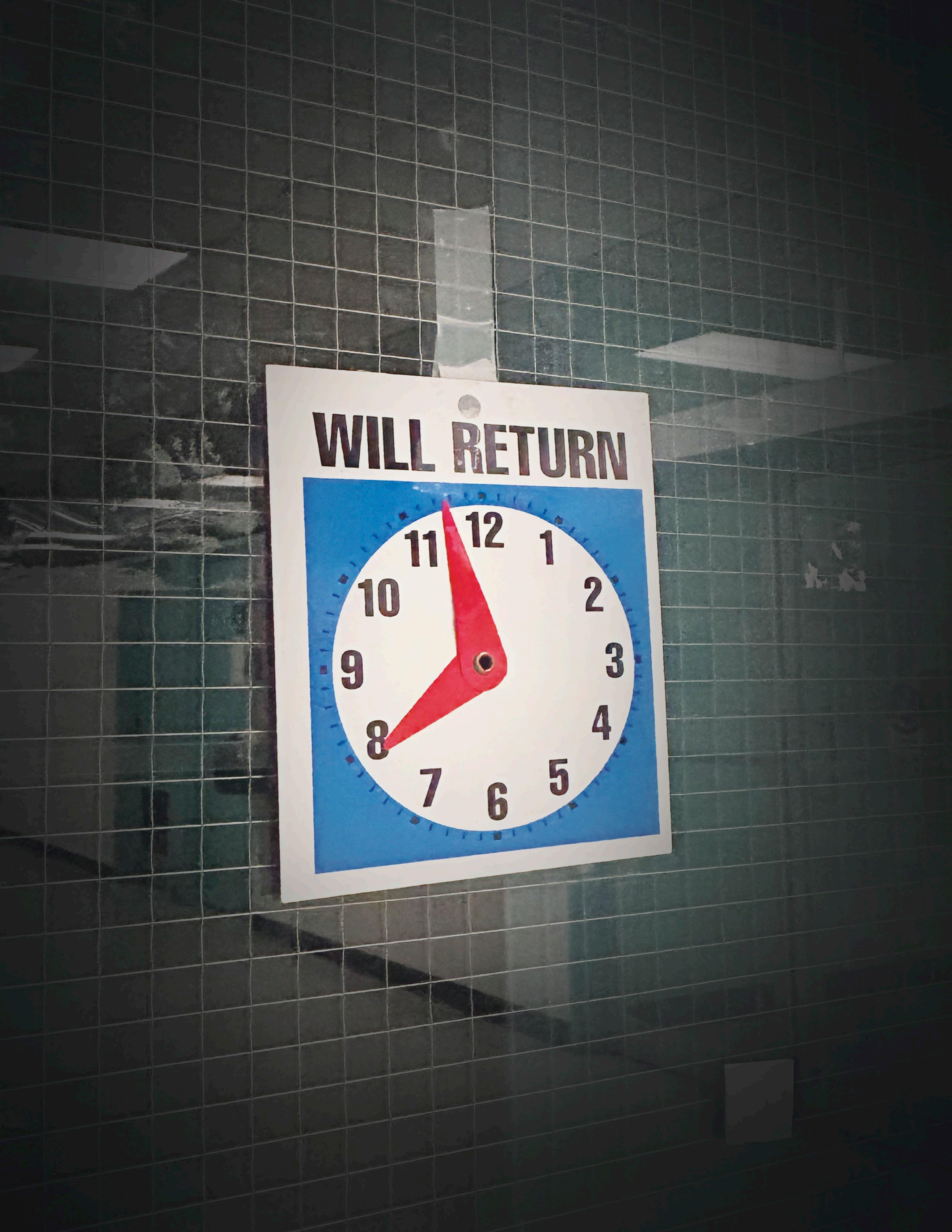

Part-time student association was full-time out of office this summer

Student fees withheld from association

Emma Dobrovnik and Ella MacCormack Assistant News Editor, News Editor

The Association of Part-Time Undergraduate Students (APUS) offices and emails have been closed since April 25, covering the entire summer academic session, despite membership more than doubling to 14,000 students during the period.

APUS has not completed the 2024–2025 or the 2023–2024 audit, and the 2022–2023 audit was only finalized in June. The university withholds APUS’ yearly student fees, totalling around two million dollars, until the association submits its audit to the Governing Council (GC).

The association also did not promote events, summer hours, or general meetings via social media, and could not be reached at the email addresses or phone numbers listed on their website.

Out of office, digitally and physically

Every executive and staff member was emailed this summer — some multiple times — but The Varsity did not receive a response until hours before the weekly print publication ended on September 7, when a joint statement arrived from APUS President Jaime Kearns, Vice-President External Shanti Dhoré, and Vice-President Internal Dianne Acuna.

Emails to APUS’ president, info clerk, office & information coordinator, and events & outreach coordinator all triggered the same automated reply, stating that the Sidney Smith offices were closed as of April 25 and directing inquiries to the president’s email. The messages gave no reopening dates.

As recently as September 2, the info clerks and office & information coordinator still had the same automatic replies.

APUS’ listed office hours at Sidney Smith and North Borden Building are Monday to Friday, 10:00 am to 6:00 pm. As of September 5 — four days

until two

delayed audits are submitted to U of T

into the fall semester — both offices remained closed. A representative from the Arts & Science Student Union said they had not seen any activity at the Sidney Smith office since May.

On September 4, The Varsity found the North Borden office door unlocked and the lights off. A package delivered on July 2 still sat unopened at the Spadina Crescent office. The tap was dripping.

The joint statement did not address APUS’s absence from its office or its lack of email responses. President Kearns wrote separately to The Varsity, “We can understand how it may have been hard for folks to get in touch with us, but we request that the Varsity contacts us through our APUS accounts and not our personal email or social media accounts to respect privacy as they are not publicly advertised.”

Missing audits

APUS has not completed its audits for the past two fiscal years. The GC withholds each year’s student fees until it receives the approved audit. The 2022–2023 audit was only finalized this June and uploaded publicly in early September, while this article was being written.

In the joint statement, APUS executives wrote, “At our August 2025 board meeting, the board made a recommendation to adopt the Fiscal 2023 audited financial statements. At the Special General Meeting held in September 2025, the Fiscal 2023 audited financial statements were ratified. Auditors were also appointed to conduct the Fiscal 2024 audit and that is currently underway. Fiscal 2025 will be conducted after that.”

The Varsity was unable to attend the Special General Meeting on August 28 and did not receive a response to requests for meeting minutes or a meeting recording. Neither has been uploaded to APUS’ website.

When asked whether the delayed audits had affected APUS’ operations, the statement read:

“At this time, the UofT administration has released APUS some of the membership fees… Throughout the last year, we have notified both our board and membership at general meetings of the financial constraints APUS continues to experience, but when approving proposed budgets, we will continue to prioritize servicing our membership.”

APUS’s mandatory membership dues are $13.65 for part-time students in the fall, winter, and summer terms. Its most recent 2022-2023 audit lists $2,314,380 in total revenue, which includes health and dental insurance fees.

Summer work

APUS’ Instagram feed has been inactive since March 13. Historically, the association has hosted socials, general meetings, and workshops during the summer, but this year it was also absent from this year’s UTSU Clubs Fair.

On May 7, winter semester part-time students received the APUS newsletter, which stated: “we’ll return for the Summer 2025 terms after a brief hiatus.”

The next newsletter was on July 9, announcing a $250 summer bursary program and the upcoming August Special General Meeting. The final summer newsletter came on August 21, giving notice for the general meeting and promoting the Canadian Federation of Students (CFS) Ontario’s Food Experience Survey, and “Hands Off Our Education!” campaign. These updates were only shared via the APUS newsletter.

In response to questions about its activity over the summer, APUS executives wrote the following in the joint statement:

“This summer, the following was provided to our membership: bursaries, [Canadian Federation of Students Ontario General Meeting] CFS OGM, Special General Meeting, and the laptop loan program. In addition, at our monthly board meetings, our board is updated on the advocacy

work and programming to our membership, along with the financial status of our organization. In addition, there are other committees that meet throughout the year as well including the Finance Committee.

Members of the APUS Board and Executives attended CFS meetings namely Skills, the Ontario Circle of First Nations, Metis and Inuit Students stand alone conference and RISE.

Throughout the year our memberships’ part-time voices are further represented as we also attend other UofT committees ie, [Council of Student Services] COSS, Hart House etc.”

The Hart House Board of Stewards has historically only met from September to April.

Three of APUS’s four executives also hold separate roles within CFS Ontario: Kearns served as Circle of First Nations, Métis and Inuit Students Constituency Commissioner; Dhoré was Local 97 representative; and Jennifer Coggon chaired the Part-Time and Continuing Education Caucus.

APUS staff, executives, and honorariums Kearns has been APUS president since 2019, despite graduating from U of T in 2020. When asked about the length of her presidency, the statement replied: “APUS annual elections, as mandated by our membership and reflected in our bylaws, took place earlier in the year, where executive and board positions were open. Elections are held and conducted in a democratic manner. All APUS members are eligible to seek nominations.”

When asked if the APUS executives and staff were paid during the summer, APUS wrote: “All democratically elected executive committee members receive a small honorarium as stipulated in the APUS bylaws and policy.”

Executives receive $800 per month, while staff are paid either $28.91 per hour or an annual salary, with the member services coordinator paid $52,941.98, and the executive director paid $65,000–$70,000.

Students move into new Oak House residence after two-week delay

“It was a bit chaotic,” said a first-year from Vietnam

Junia Alsinawi Deputy News Editor

On September 6, students moved into the new Oak House residence on Spadina Avenue and Sussex Avenue after a two-week delay. On August 22, a day before the original move-in, residents received an email stating that move-in would be pushed “about a week” due to “last minute construction delays.” After this email, the move-in was further delayed to September 6, as reflected by the Oak House website.

Students who could delay their arrival were offered a $500 credit, and their room and meal plan fees were adjusted to reflect the delay. Students unable to delay their arrival were provided with temporary residence at Parkside Student Residence or CampusOne.

In a statement sent to The Varsity, Janice Johnson, executive director, Student Housing & Residence Experience, wrote, “We are in frequent communication with the affected students, housing all of them at other student residences if they wish and providing the full orientation experience as well as supports and activities in their temporary accommodations.”

Even with students now living in the building, Oak House has ongoing construction. The residence’s website currently reads, “Please be advised that a few areas and features will still require some extra touch ups following movein day.”

“We regret the disappointment, frustration and added stress caused by the delay. Our full focus is on this matter, with the academic success of our students the top priority,” Johnson wrote in her statement to The Varsity

“We made every effort to have everything ready. At the final inspection on Aug. 22, however, we determined more construction work was needed.”

Oak House was developed by the university in partnership with The Daniels Corporation, a Toronto-based builder and developer. When asked about what specific construction work was still needed, both media relations teams declined to comment.

A smooth move-in day

On move-in day, students pulled suitcases and carts loaded with bags through the lobby of Oak House, where music played from speakers and smiling residence staff helped them check in. The Varsity spoke to students moving in to find out how the delay has impacted them.

“I commuted from home…[in] Markham,” said Matthew Scott, a first-year social science student, who said he was still able to attend his orientation week despite the disruption.

For second-year history student Rory McGreth, the delay was not a problem. “I wasn’t even going to be here anyways,” he said.

Jocelyn Luong, a first-year life sciences student from Vietnam, spent the two-week delay with family members who live in Toronto.

“It was unfortunate. Obviously, I hoped to come here a bit early before school starts… I kind of wanted to get adjusted, unpack everything, get everything ready before class. It is what it is.”

For Luong, moving in after classes had started, “was a bit chaotic. I had to commute a lot, but it was okay overall, because I have my relatives’ support.”

BREAKING: Director of Indigenous Student Services departs following findings of sexual harassment

External investigation into seven allegations found “several years” of sexual harassment

Junia Alsinawi Deputy News Editor

Content warning: this article discusses sexual harassment.

Michael White is no longer the director of Indigenous Student Services and the First Nations House after an investigation found that he had sexually harassed an employee over several years, The Toronto Star reported on August 31.

On August 18, the university’s director of workplace investigations, Hana Saleem, sent a letter to the complainant notifying her of White’s departure and stating that his actions were “inconsistent with the expectations that the university has for employees in leadership positions” and a breach of U of T’s policy on sexual violence and sexual harassment. The Star did not publish the complainant’s name, “due to the nature of her allegations.”

When asked if White was fired, a spokesperson from U of T said it is unable “to share details regarding personnel matters for reasons of confidentiality and people’s privacy.”

Included in the letter shared with the Star was a summary of an external investigation done by Robin Parker of Paradigm Law Group, which detailed years of sexualized and inappropriate comments made to the complainant by White. The summary also says that White did not respect workplace boundaries, sharing details of his intimate life with the complainant and contacting her outside of work. The investigator said that the complainant alleged that she felt “uncomfortable and unsafe, especially as it continued after she told him to stop numerous times.”

The complainant, who resigned from the university in part due to her discomfort in the workplace environment, raised seven allegations against White. Of these, Parker’s investigation found one substantiated, four “partially substantiated,” and two “unsubstantiated.”

The substantiated allegation against White was that, “between Sept 2022 and September 2024, the Respondent made a series of inappropriate comments by comparing the Complainant to the likeness of women he was either in a romantic relationship with or was sexually attracted to …”

The summary noted that White did not deny making these comments, “as part of a personal exchange,” but “denied the frequency alleged by the Complainant, and denied that he intended the comments in a sexual way,” however “The investigator found that the Respondent made personal comments about the Complainant with sufficient frequency to affect her comfort and ease at work.”

On September 5, White posted a full statement on Facebook, in which he expressed remorse for his conduct, writing, “Regardless of my intentions, my words and actions were inappropriate, and I regret the harm I caused.”

“I’ve had much time to reflect on and learn from this experience,” White wrote, adding, “The investigation itself lasted the better

part of a year. I was placed on leave during that time, leaving the organization without Indigenous leadership and creating disruption for staff, students, and the broader community.”

White also reiterated that six of the seven allegations were either unsubstantiated or not fully substantiated, writing, “I accept full responsibility for my actions. However, I reject attempts to distort the truth.”

In an email to The Varsity, White confirmed that he was terminated from his position at the university.

White, who graduated from U of T with a B.A. in anthropology in 2005, has spent the last eight years working at the university, first as a Special Projects Officer, Indigenous Initiatives, supporting the university’s truth and reconciliation efforts. In May 2020, White took on the role of Director of First Nations House and Indigenous Student Services.

The Star reported that the complainant said she “decided to speak up because she wants other women to know they have the right to feel safe in the workplace and shouldn’t tolerate sexual harassment.”

“Hey, no paper towels?!” Waste reduction pilot program replaces paper towels with hand-dryers across 224 UTSG washrooms

As of August, paper towel dispensers across 224 UTSG washrooms are no longer being restocked under a waste reduction pilot initiative. In an effort to reduce the environmental impact of campus operations, paper towel dispensers will no longer be restocked at major campus buildings like Robarts Library, being replaced with energy-efficient hand dryers. Promoting the initiative are the “Hey, no paper towels?!” posters plastered onto dispensers in the affected bathrooms.

This initiative was spearheaded by the Student Leadership Subcommittee (SLS) of the President’s Advisory Committee on the Environment, Climate Change, and Sustainability (CECCS) in partnership with the Facilities and Services (F&S) Caretaking team.

U of T’s waste reduction goals

In an email to The Varsity, Harshit Gujral, a fourth-year computer science PhD student and former co-chair of the SLS, wrote that the paper waste reduction could save up to 407 metric tons of greenhouse gas emissions per year.

According to the 2024 UTSG waste audit report, a total of 321,262 kilograms of paper towel and tissue waste was generated on campus, with 289,013 kilograms sent to landfill.

If you or someone you know has been affected by sexual violence or harassment at U of T:

Visit safety.utoronto.ca for a list of safety resources.

Visit svpscentre.utoronto.ca for information, contact details, and hours of operation for the tri-campus Sexual Violence Prevention & Support Centre. Centre staff can be reached by phone at 416-978-2266 or by email at svpscentre@utoronto.ca.

Call Campus Safety Special Constable Service to make a report at 416-978-2222 (for U of T St. George and U of T Scarborough) or 905-569-4333 (for U of T Mississauga)

Call the Women’s College Hospital Sexual Assault/Domestic Violence Care Centre at 416-323-6040

Call the Scarborough Health Network Sexual Assault and Domestic Violence Care Centre at 416-495-2555

Call the Assaulted Women’s Helpline at 1-866-863-0511

“Some congratulated us on collaborating across the secretariat to make this sustainable change happen, whereas others are not very happy because the paper towel is gone. I think if students knew that SLS [started this initiative] to avoid approximately 71 tons of paper towels incinerated annually, they’d support this initiative,” wrote Gujral.

According to him, F&S had attempted a similar initiative before the pandemic, but it was largely unsuccessful because of the belief that hand-dryers are less hygienic.

The pilot’s website reads, “research indicates no significant difference in the spread of bacteria between using hand dryers and paper towels.” CECCS cites five studies to support this statement — although three of the studies were funded by Dyson, a hand dryer production company.

In fall 2024, members of the SLS reviewed the potential of paper waste reduction, and by November 2024, voted to make this initiative a top priority. The pilot received strong support from UTSG’s Sustainability Office, the Governing Council, and the Research and Operations subcommittees of CECCS.

Everyone we talked with supported our initiatives, but they shared with us some real systemic bottlenecks.”

Reflecting on this support, Gujral wrote, “I thought getting the university to agree to any sustainable change would require lots of persuasion on the part of SLS. I was wrong.

Student’s heated response to hand-dryers While student perspectives on this initiative are still being collected through a feedback form, the pilot has already received mixed reactions.

The research on the hygiene of paper towels compared to hand dryers has been inconclusive or inconsistent in the results, and many of the major studies were industrysponsored. Studies funded by the European Tissue Symposium favour paper towels; studies funded by Dyson favour hand dryers. While the paper towel waste reduction pilot is SLS’s most recent initiative, the subcommittee has led several other successful projects promoting sustainability and campus health. For example, SLS previously introduced biodegradable soaps and cleaning products to reduce the environmental and health impacts of harmful chemicals.

SIMONA AGOSTINO/THE VARSITY

Mashiyat Ahmed Varsity Contributor

UTGSU VP External Seema Allahdini on leave, predecessor Jady Liang hired in interim

President Amir Moghadam says Allahdini on leave of absence until January

The University of Toronto Graduate Students’ Union (UTGSU) has hired Jady Liang as the interim Vice President (VP) External, following VP External Seema Allahdini’s decision to take an unpaid leave of absence, which began on August 18.

In an email to The Varsity, UTGSU President Amir Moghadam wrote that Allahdini’s leave is set to end on December 31, “with the potential for her to return earlier or later depending on circumstances.” Moghadam also wrote that the “specifics” of the leave of absence “are personal and private to Seema.”

In the same email, Moghadam explained that Liang was chosen for the interim role following “a very comprehensive and thorough hiring process conducted by a hiring committee appointed by the Board of Directors.”

The hiring committee unanimously recommended Jady Liang, the 2024–2025 VP External, and finalized her appointment at the August 18 Board of Directors (BOD) meeting.

In an email to The Varsity, Liang wrote that as interim VP External, she will continue Allahdini’s efforts working to develop a UTGSU Sexual Violence and Harassment Policy, publish the Cost of Living Survey report, update the UTGSU Issues Policy, and launch a campaign against Ontario Bill 33.

“My goal is to ensure a smooth transition while continuing to advocate strongly for graduate students.”

Liang has been involved in the UTGSU for

several years, previously serving on the Board of Directors for the 2023–2024 academic year.

In November 2023, Liang was appointed to the role of interim VP External after Neelofar

Junia Alsinawi Deputy News Editor

Ahmed resigned following allegations of harassment and violation of union bylaws.

The following year, Liang was formally elected UTGSU’s VP External, launching the UofT Grad Thrive mental health campaign in October 2024. Under Liang’s leadership, the campaign implemented a peer support initiative, pet and art therapy programming, and a mental health grant.

UTGSU VP External acts as the union’s primary liaison with external groups to advocate for student interests across a wide range of issues and increase accessibility to outside resources. This role also acts as the executive representative to the Canadian Federation of Students (CFS), a role which, as Liang wrote, she will use to “strengthen student advocacy at both the provincial and national levels.”

Before serving as VP External, Allahdini was a research and campaigns assistant with the union, and worked as a project manager and program coordinator with the Women’s Support Network of York Region.

Moghadam wrote that Allahdini “brought a wealth of non-profit management experience and deeply cared about underrepresented student populations.” Allahdini did not respond to The Varsity ’s request for comment.

Emergency grant and food security levy dominate UTGSU summer

Directors also discuss U-Pass, change Division 1 election procedure

The University of Toronto Graduate Students’ Union (UTGSU) met in July and August to implement an emergency grant fund, plan for GradFest, begin collecting a survey to implement a new food security levy, and plan for long-term success. UTGSU Board of Directors (BOD) members also discussed the resignation of interim Director of Division 1 Aditi Kolluru and the unpaid leave of absence of Vice President (VP) External Seema Allahdini.

Adoption of Policy O6.3: emergency grant fund

President Amir Moghadam reviewed the proposal for an emergency grant fund, the result of work done by Governance Committee chairs VP Internal Dominic Shillingford and Executive Director Corey Scott. Ultimately, the motion sought to immediately adopt the policy within the UTGSU Policy Handbook so that students could access resources as soon as possible. The motion carried. The grant provides “up to $1,000 in financial support for graduate students facing unexpected emergencies beyond their control,” such as family emergencies, cases of gender based violence, sudden loss of income, and medical crises. To be eligible to receive grant funding, a student must be a UTGSU member in good standing, apply for the grant within six weeks of the emergency,

demonstrate significant financial need, and be unable to receive aid from other emergency funds, such as the School of Graduate Studies Emergency Fund.

GradFest, fare capping, and U-Pass VP Graduate Life, Eliz Shimshek, offered remarks on her coordination of GradFest, noting that over 200 students had signed up within the first day on Rubric. Shimsek reminded the BOD of the need for as much help as possible for volunteering, postering, and coordinating departmental orientations.

The executive team then led a discussion of long-term plans for UTGSU. President Moghadam emphasized the lack of sustained action across

election cycles and his aim to work on a five-year plan, presented across the union at various levels. VP Academics Nicholas Silver informed members of his ongoing work with 10 university student unions to form a GTA transit coalition. Among the objectives are fare capping and developing a U-Pass, with the prospective hire of a dedicated executive associate to streamline engagement for the campaign.

Division 1 directors

The board approved a by-election timeline for Division 1: Humanities directors and reduced the required nominators for the role from 15 to five, in response to Division 1’s struggles to run candidates.

In the by-election proposal, directors appointed public policy graduate student Harmanbeer Sandhu as Chief Returning Officer and approved a nomination period between September 15–25, a campaign period between September 29 to October 8, and a voting period between October 6–8.

Food security levy fee

In research conducted by the union of over 2,500 graduate students, 61 per cent cannot afford balanced, nutritious meals, 57 per cent are food insecure, 28 per cent skip meals to save money, and seven per cent have gone days without eating. UTGSU’s 2024–2025 collaboration on weekly lunch programs regularly sold out.

Moghadam requested that the BOD support the collection of signatures for a referendum on a food security levy fee of up to $5.00 a term. Such a levy would go towards funding emergency food relief, subsidized meal programs, cultural food programs, kitchen infrastructure, and partnerships with community organizations.

Executive Director Scott pointed out that the survey covered both doctoral and master’s, funded and unfunded, and domestic and international students, while including students who did not experience either housing or food insecurity.

When asked by Director Valentyna Kundas about support for students at either Scarborough or Mississauga campuses, Moghadam expressed that the focus had primarily been on St. George campus. The motion carried.

Liang: “My goal is to ensure a smooth transition while continuing to advocate strongly for graduate students.” CORINNE LANGMUIR/THEVARSITY

Matthew Molinaro Graduate Bureau Chief

Editorial September 9, 2025

thevarsity.ca/section/opinion opinion@thevarsity.ca

Editorial: What can be learned from Gertler’s broken legacy

The Varsity reflects on President Meric Gertler’s 12-year term

After nearly 12 years in the role, Meric Gertler stepped down as president of U of T, with Melanie Woodin, the previous Dean, Faculty of Arts & Science, succeeding him as U of T’s new president.

For Woodin to make good on her promise to “deepen U of T’s contribution to human, social and economic well-being,” the Editorial Board feels that it is imperative that we not only reflect on Gertler’s legacy, but learn from it.

Therefore, as we usher in the Woodin presidency, we want to better understand Gertler’s place within our community’s history. Most importantly, we want to understand where he went wrong and what lessons new U of T leadership can take from his tenure.

It’s hard to deny that Gertler’s administration played a key role in elevating U of T’s global profile, as U of T remains internationally revered as a leading global higher education institution. However, Gertler’s leadership was far from perfect. Notable moments during his presidency include the faculty controversies surrounding Robert Reisz and Jordan Peterson, fossil fuel divestment campaigns, Canadian Union of Public Employees (CUPE) labour protests, and, most recently, mass student movements protesting the genocide in Palestine.

In tracking Gertler’s response to key events over the past decade, The Varsity ’s Editorial Board believes that Gertler’s priority has not been the well-being of students and faculty, nor has it been the preservation of civil discourse. Instead, we feel as though he has placed the institution’s reputation, revenue generation, and funding models above all else.

An international institution

Gertler’s emphasis on the university’s global standing is perhaps most clearly reflected in U of T’s expanding international presence. U of T ranked 21st among universities worldwide in 2024. In 2025, Times Higher Education gave the university a score of 91.8 for its international outlook.

U of T’s international presence was reflected in the increase in international students over Gertler’s tenure. International students made up 30 per cent of the graduate and undergraduate population across all three campuses in the 2023–2024 academic year — nearly two and a half times more compared to 2012 numbers, before he took office, when they accounted for 13.97 per cent.

As the number of international students has increased during Gertler’s tenure, so have international student tuition fees, which have risen by a steep 84 per cent during his tenure. Tuition accounts for 65 per cent of the university’s total revenue, of which international student tuition alone contributes to 42 per cent — despite representing 30 per cent of the student population.

The fact that U of T continues to charge international students upwards of $60,000 per year, despite calls from the University of Toronto Students’ Union and the International Student Advocacy Network to reduce tuition — especially during Canada’s cost of living crisis — suggests to us that the university would prefer to reap the reputational and financial benefits of a large international student body without addressing the financial struggles and well-being of those students.

The Editorial Board believes that the duty to keep U of T financially afloat should not fall primarily on students. International students should not be used as a crutch to

compensate for the government’s shortcomings. If Gertler’s administration wanted U of T to be seen as a global institution, it should have acknowledged the students’ demands and addressed the root cause of this flawed funding model. Instead of succumbing to government funding cuts, the U of T president must stand alongside advocates to mobilize against a provincial government that continues to defund education.

In an interview with Times Higher Education in October 2022, Gertler referred to Peterson as a “provocateur extraordinaire.” Despite student calls for his removal, Gertler justified Peterson’s continued affiliation in the interview, and said: “if we are doing the right thing, we should be creating a platform to debate the positions that somebody like Professor Peterson would bring to the public realm, and that’s what we did.” But our Editorial Board argues that it’s one thing to protect the academic

3902. In January 2020, CUPE 3902 called on the university to open negotiations about salary increases, and no agreement was reached until January 2021.

In a November 2023 CBC article, Gertler expressed concerns about how Ford’s cuts would affect the way Ontario universities are perceived globally. Still, after nearly five years of silence, he did not acknowledge how such cuts would affect students and faculty.

In 2022, CUPE 3261 would go on strike as well, due to disputes over an increase in contract staff who earn less than non-contract workers, have fewer health care benefits, and have less job tive agreement with the university only “72 hours

The agreement came a day after CUPE 3261 held a campaign in front of Sidney Smith called “Good Jobs U of T” to raise awareness about job tions. The university’s decision to cut the pay and benefits of the university’s caretaking staff began

The Varsity Editorial Board

It is also difficult to reconcile these cuts as the university’s operating revenue increased from $2.16 billion in the 2015–2016 academic year, to $3.52 billion in the 2024––2025 academic year. With this under consideration, we are forced to ask how the university could not afford to increase, let alone maintain, its staff’s salaries?

Gertler repeatedly failed to address the concerns of faculty and staff until he was pushed into a corner by the accumulation of years of petitions, open letters, and strikes. As such, it is clear to us that he did not lead U of T with concern for the community, as leading with care would be reflected in union negotiations and the proper treatment of staff.

Mental health on campus

While U of T is known for its academic rigour, it also carries a reputation for overworking students and providing little support to help them manage the pressure. U of T students have often relied on online forums to express concerns about their well-being due to the lack of accessible mental health services.

Three students died by suicide at the Bahen Institute of Science and Technology from 2018–2019. In 2020, another student died by suicide off-campus. Although Gertler expressed condolences and implemented policies for better student support, U of T’s mental health support model remains police-based. Student advocacy groups have called on U of T to defund campus police and implement “anti-carceral community safety initiatives.”

In a 2019 letter to

students, faculty and staff, Gertler outlined several steps the university would take in response to the suicides. These included calling on the provincial government to increase funding for mental health resources, instructing the Expert Panel on Undergraduate Student Educational Experience to consider mental health issues in its decisions, and coordinating with Toronto health services to support student care. Physical guard rails were also added to the Bahen Institute in 2019 to prevent further attempts.

Despite these new policies, in September 2019, a UTM student was handcuffed by Campus Safety while seeking mental health support and was escorted to a hospital via police vehicle, which Gertler’s administration only addressed in a 2022 Campus Safety report.

In subsequent years, many student unions and organizations have called on the university to defund the police-based model or at least implement models with de-escalation techniques for mental health crises.

A 2024 Campus Safety Report announced that Mental Health Acts — characterized as responses to students experiencing a mental health crisis — increased from 56 incidents in 2023 to 89 incidents in 2024. The same report found that only four officers participated in the optional “Mental Health and Violence Risk Workshop,” and five in the “Scenario Based Mental Health and De-Escalation Training,” all while 23 officers attended “Preparedness and Protest Management Training,” highlighting the priorities of many of the officers. By providing mental health training as an optional module for Campus Safety, there is no way students can trust that officers are equipped with this skill. Campus Safety is one of the few resources offered to students by the administration in times of immediate crisis, and the Editorial Board believes that having supplementary mental health training instead of essential mental health training is an oversight. Gertler’s policies ultimately ring hollow to us when precisely investigated, simply an illusion of care.

Student calls for divestment

Postsecondary institutions have long been hubs for social movements, and U of T is no exception. Climate advocacy groups on campus, such as Toronto350 and UofT350, have been campaigning for fossil fuel divestment since 2012.

In 2016, Gertler’s administration published a report that rejected their recommendations, which directed the University of Toronto Asset Management Corporation (UTAM) to adopt more ethical investment policies that “determin[e] investment worthiness on a firmby-firm rather than industry-wide basis.”

After years of protests and rallies, including those by advocacy groups like Climate Justice UofT, Gertler announced in 2021 that the university would divest from the four billion dollars in fossil fuel investments remaining with UTAM at that time.

However, three months prior to the divestment commitments, UTAM — which was created to manage U of T’s endowment, expendable funds investment pool, and pension plan — transferred the management of its pension fund to the University Pension Plan (UPP), a joint pension plan across several Ontario universities. We believe this move was a strategic effort to relocate the funds into a business structure that would obscure the public details of these investments, making it more difficult for students to hold the university accountable for the 10.2 billion dollar pension fund it transferred to the UPP.

Finally, it’s impossible to discuss the Gertler administration without addressing the pro-Palestine encampment on King’s College Circle, the People’s Circle for Palestine — one of the longest-running pro-Palestine encampments at a Canadian university.

Gertler categorically condemned the October 7 attacks in a formal statement on October 18. Meanwhile, with Israel’s invasion of Gaza, and the genocide that followed, Gertler maintained that the university would retain “neutrality on issues of scholarly debate.”

In light of its promises to civil discourse and “neutrality,” we believe that the university should never have threatened police action against students protesting genocide via a court injunction, a view made clear in our June 2024 Editorial.

We are especially perplexed by the dismissal of former UTSC Imam, Omar Patel, for allegedly sharing an anti-Israel Instagram story, which Patel denies. When Patel was let go, there was no transparent investigation — distancing the university from controversy rather than engaging Muslim students and the wider U of T community.

Reisz continues to be employed, Peterson got a slap on the wrist, yet Patel was forced out with no further statement. This inconsistency baffles us.

Rather than aligning with student demands, the university has historically ignored student social justice movements until increased federal and institutional support.

The South African divestment movement at U of T began in 1983, but the first major protest for full divestment on campus took place on March 4, 1987, when students occupied President George McConnell’s office after unsuccessful negotiations. It was not until an optional request from the Canadian government to divest from companies involved in segregation or pay inequality in 1988 that McConnell’s administration finally divested.

By eventually joining much of the world in divesting from South African apartheid, U of T contributed to the pressure that led to the end of the apartheid regime. With the privilege of hindsight, U of T knows it made the right decision to listen to its students and divest from injustice.

The International Court of Justice has warned Israel to comply with the Genocide Convention, and human rights organizations, such as Amnesty International, concluded that Israel is committing genocide in Gaza. Why should the university wait to side with the overwhelming student voice for justice and peace? How much longer must U of T remain complicit in genocide?

Melanie Woodin and Gertler’s legacy U of T is a public institution, an educational home for thousands of students and staff, and yet Gertler has led U of T like a business.

Gertler is a skilled businessman — he increased U of T’s revenue and raised our international presence. Gertler also knows how to maintain the university’s reputation: staying silent to appease donors and the government, leaving negotiations to the 11th hour, and implementing ultimately performative policies.

Being president of U of T is no small task. However, the president represents more than the operational and business side. The president represents and serves the faculty and student body, and it seems to us that Gertler has neglected the human aspect of being president.

Gertler’s exploitation of international students, passivity with violent professors, attacks on unions, inadequate mental health strategy, and indifference towards the genocide of Palestinians in Gaza, were not only avoidable mistakes, but lessons to learn from. Melanie Woodin, as you begin your tenure as president, we must ask: will your presidency be a continuation of Gertler’s legacy, or will it mark a shift towards justice for our staff, students, and wider global community?

OLIVIA MAR/THE VARSITY

September 9, 2025

thevarsity.ca/category/science science@thevarsity.ca

The hidden fungi inside insects

What fungi in the guts of insects reveal about ecosystems

Sumhithaa Sriram Varsity Contributor

When you think of fungi, you might picture mushrooms sprouting from forest floors, mould creeping over leftover bread, or maybe even Penicillin — a common antibiotic derived from fungal moulds. But there’s a strange fungus you have probably never heard of, one that doesn’t grow in soil or food but thrives deep inside the guts of aquatic insect larvae and immature insects, called nymphs, that live in aquatic ecosystems.

These fungi, known as Trichomycetes, live inside the guts of mayflies, stoneflies, and other freshwater insects. Notably, these fungi are completely dependent on their insect hosts, deriving all their nutrients from them; in return, they may benefit their hosts, harm them, or leave them unaffected.

These microscopic fungi have existed quietly within insects around the world for more than 200 million years. Yet, they have largely remained scientific wallflowers due to population changes, difficulty in culturing, and limitations in molecular biology resources and technologies.

Hidden signals in the insect gut

Freshwater ecosystems are under threat due to urbanization. As cities grow, they send stormwater runoff — which often carries excess nutrients, sediments, heavy metals, and other pollutants — into lakes, rivers, and streams. This disrupts the delicate chemical balance of local ecosystems. In addition to runoff, urbanization introduces chemical pollutants through industrial discharge and household waste. These pollutants cause physical habitat disruptions such as altered flow patterns, channelization — changing a river or stream’s flow by building artificial channels — and the removal of vegetation.

Scientists need reliable ways to detect when these ecosystems are becoming stressed or degraded, because early detection allows for intervention, restoration, and policy development before irreversible damage occurs.

That’s where bioindicators come in. These are organisms whose survival and community composition are tightly linked to specific environmental conditions and thus make them sensitive indicators of ecological change.

Environmental scientists have long used benthic insect larvae and nymphs as bioindicators because they are sensitive to pollution and are extremely easy to collect. But here’s the catch: many

could zoom in further, all the way into their gut, and find something even more sensitive to pollution than benthic insects?

This question drives my research in the Wang Lab — led by Yan Wang, an Assistant Professor at U of T’s Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology. The Wang Lab is where I first learned about Trichomycetes, igniting my passion for these fungi.

Trichomycetes are obligate symbionts — meaning they can’t survive without their insect hosts. They’re deeply intertwined with their host’s biological composition and health. If environmental stressors affect the insects — say, by changing the chemistry of the stream water — those changes might show up even more clearly in their gut-dwelling fungi. In other words, Trichomycetes could serve as ultra-sensitive bioindicators, offering a warning system for ecological disruption.

Mapping a microscopic world

To test this idea, I began collecting aquatic insects from two urban stream systems in the GTA: the Rouge National Urban Park Stream and the Highland Creek Watershed. These streams offer fantastic comparative models as the Highland Creek stream flows through areas affected by urban development, while the Rouge Park stream remains in a more conserved area, making them ideal case studies for tracking the effects of environmental stress on diverse ecosystems.

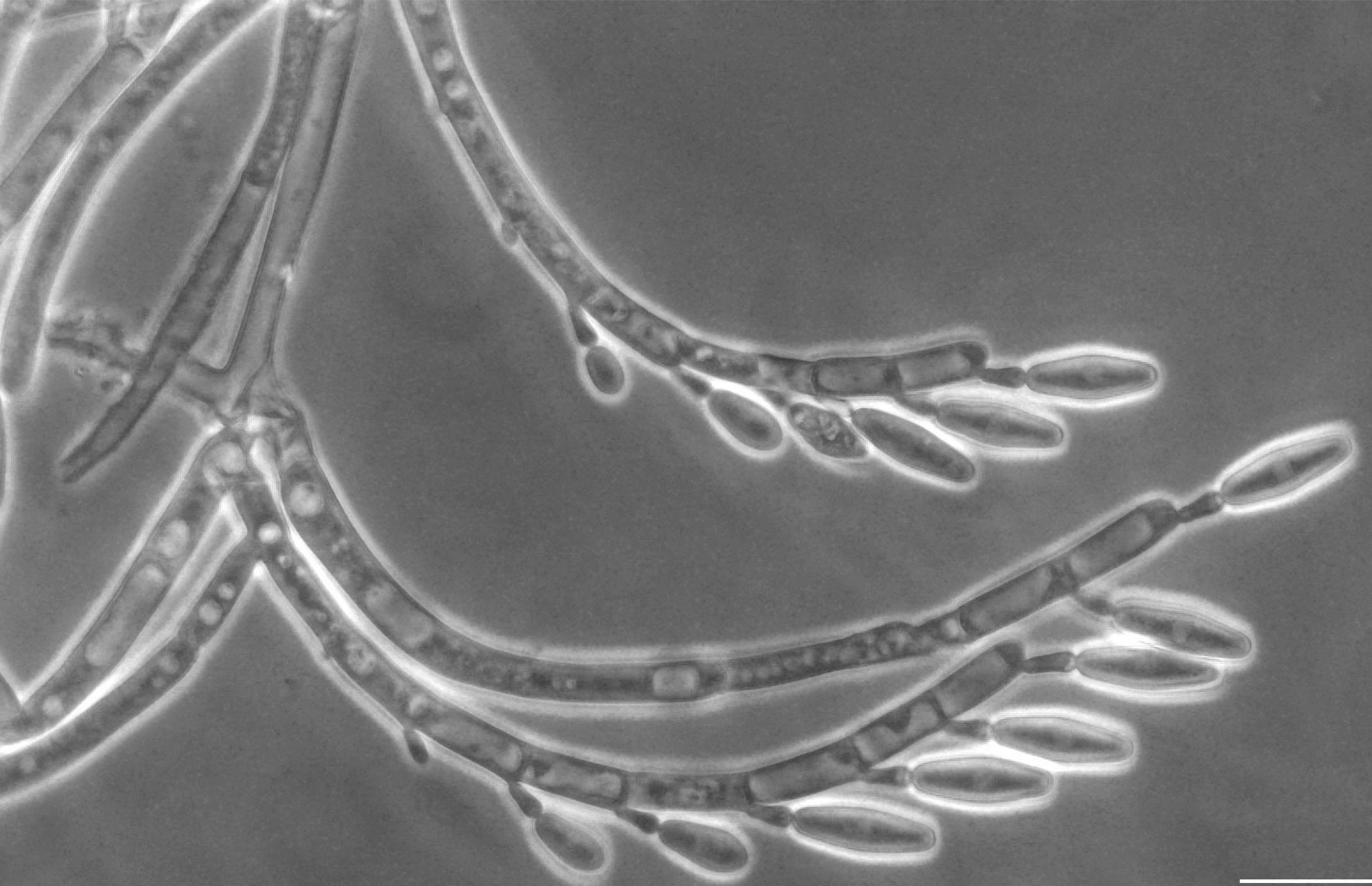

After collection, each insect was carefully dissected under a microscope, and their gut tissue was teased apart in search of fungal filaments. Some samples were identified using morphological keys, which are guides that help identify the exact species of fungi based on their physical features. Others were sent for DNA sequencing, specifically targeting the 28S rRNA gene region. Gene regions are specific stretches of DNA that code for particular molecules or functions. 28S rRNA codes for part of the ribosomal RNA structure, which is crucial for making proteins.

In this case, the 28S rRNA gene is useful because it evolves slowly and remains mostly unchanged in ancient fungal groups like Trichomycetes. This stability makes it a reliable marker for identifying and classifying fungi at a deeper evolutionary level.

This process went on for three years, wherein we made some amazing discoveries. And recently, something unexpected happened.

Among the samples of aquatic insects, we dis-

complete set of DNA — had never before been documented. The genome of this fungus, which is still being analyzed, represents not only a new data point but also a reminder of how much microbial biodiversity remains hidden in urban streams. Like so much microbial biodiversity research, the work on understanding this new species is also ongoing.

Patterns in the prevalence

Through this work, we’re beginning to notice patterns: certain Trichomycetes species appear more frequently in cleaner, less disturbed sites. Others may be tolerant of, or even thrive in, water with high levels of dissolved solids or metal concentrations. We are also finding that the diversity of Trichomycetes tends to drop in polluted or heavily urbanized streams, suggesting that their presence or absence in the water could reflect ecosystem quality on a very fine scale.

To better understand these correlations, we measure variables such as pH level, temperature, total dissolved solids (TDS), levels of urbanization close to the freshwater ecosystems, and metal concentrations at each collection site.

Over time, this dataset could reveal new insights into how environmental stressors influence not just insects or fungi individually, but entire ecological networks, from streams to stomachs. By tracking shifts in composition of species in the system and environmental variables like heavy metals or nutrient levels, these indicators can reveal cascading effects on food webs, microbial communities, and ecosystem health.

A window into ecosystem health

What excites me most is that we’re only scratching the surface. There’s still so much we don’t know about Trichomycetes, like how they establish symbiosis, how they interact with other microbes, and

Imagine a future in which Trichomycete surveys are part of routine water-quality monitoring; imagine being able to detect pollution not just from chemical tests, but from changes in the microbial communities inside a mayfly’s gut.

This is the kind of imaginative, fine-scale science that could transform how we manage and protect freshwater environments. Unlike traditional methods that rely on momentary snapshots of water chemistry, gut microbiota reflect cumulative exposure and biological responses to stressors over time. This makes them sensitive, integrative indicators of ecosystem health.

By incorporating bioindicators like Trichomycetes into ecosystem health assessments, we could catch subtle, early-warning signs of ecological degradation before they escalate — improving our ability to intervene, restore, and conserve aquatic systems with greater precision and foresight.

Following my gut

Looking back, I think my fascination with insects and nature started much earlier than university. As a child, I used to collect tiny bugs and water critters from puddles and streams, inspecting them with wonder and curiosity. I didn’t know it then, but that early fascination would one day guide me toward a career in ecological research and lead me to a fungal world hidden inside the gut of an insect.

Sometimes, we’re told to ignore our gut feelings. But for me, following mine opened up a world of science I never knew existed. If there’s one message I would share with the next generation of curious minds, it’s this: trust your instincts, stay curious, and don’t be afraid to explore what others overlook.

Sometimes, the answers to big questions can be found in the smallest places!

Smittium culicis, a species of Trichomycetes with a 20 μm scale bar. Image captured on a compound microscope. SUMHITHAA SRIRAM/THEVARSITY

Sumhithaa Sriram collecting insects in a stream at the Rouge National Urban Park.

Developmental biology goes virtual A Canadian-led initiative aims to simulate human development using computational models

Parmin Sedigh Varsity Contributor

As written in the well-known textbook Developmental Biology, “One of the critical differences between you [as an embryo] and a machine is that the machine is never required to function until after it is built.”

Yet, scientists are turning to machines to help them model and understand the very thing machines don’t have to do — develop and evolve their function.

Our understanding of human development continues to grow, but these findings often remain disparate and disconnected from the bigger picture of development. For one a variety of model systems help make discoveries, from mice to fruit flies, each focusing on a few specific cell types or a single organ system.

To better understand this complexity, scientists have been turning to computational models.

The Virtual Human Development Consortium (VHD) — an international group led by scientists at U of T and the University of British Columbia (UBC) — is contributing to this modelling effort by building “a computer-based simulator of human embryonic development.”

The VHD, alongside other groups around the world, is attempting to bring together developmental findings and knowledge across many tissues, experimental models, and scales with the help of experimental, theoretical, and computational biologists.

The project was founded in 2021 by Maria Abou Chakra, a research associate in the Bader lab at U of T, and Nozomu Yachie and Nika Shakiba — a professor and assistant professor, respectively, from UBC. The VHD is still in the early stages but the group has ambitions of making the virtual simulator a reality with the help of this community.

Models: what are they good for?

Creating theoretical models of biological phenomena has a decades-long history, spanning

disciplines from ecology to immunology. Nowadays, much of the theoretical work involves coding behind the computer, explains Abou Chakra, in an interview with The Varsity.

Modelling can take many forms and have many goals, but Abou Chakra explains her preferred approach: “We try to simplify things and try to capture [biological processes] with as few steps as possible. So if you can capture 90 per cent of the phenomenon with one or two rules, why would you add all the complexity that you think exists? [...] Complexity doesn’t always mean accuracy.”

Abou Chakra doesn’t see these research models as the endpoint but rather a way of opening up new avenues of research. “It shouldn’t just answer a question and end there. Is it also generating a new question for us? [...] Did it open up a new window that we have to explore?” This exploration can come in many forms, including collaborations with experimental biologists.

To illustrate this, Abou Chakra brings up her work on a digital cell model. She began by looking at the current literature on what defines a cell, settling, for the time being, on rules around cell death, cell size, and the cell cycle. But throughout this process, she discovered a gap in scientific knowledge: how does the rate of cell division change early in human development?

“What I couldn’t find was the rate of the slowdown [of cell division]: was it linear, gradual, abrupt, or exponential?” This eventually led to “proposing a whole new mechanism for the cell cycle, which not only controls cell numbers but [...] also regulates the diversity of cell types,” explains Abou Chakra.

Once a model is created, scientists can make tweaks or disturb the system and observe the effects. Does a disturbance to one of the model’s rules result in a disease we see in humans? Bingo — there’s a new avenue of research to explore further.

This feature is particularly helpful in ethically thorny areas of research, many of which exist in the world of development. For instance, there are

guidelines and regulations on culturing human embryos in the lab for longer than two weeks for several reasons, including fears of the embryos gaining the ability to feel pain. This has earned the two- to four-week time period the name “the black box” of development.

Models don’t share these ethical limitations and can shine some predictive light, at the very least, on this developmental time point.

Challenges

that lie ahead

One of the biggest barriers to overcome with such an ambitious project — which spans three continents and nine countries — is to secure a thriving community with active participation. Building community and bridging gaps in communication between biologists and theoreticians from a variety of backgrounds has been a focus of the VHD from the beginning.

In an interview with The Varsity, Sidhartha Goyal, an associate professor at the U of T Physics Department and member of the VHD, said he joined “mostly because [he has] good friends there and… good science happens… because we work with people we enjoy working with.”

Goyal’s lab applies physics to many biological contexts. In a recent project led by Mehrshad Sadria — currently a machine learning scientist at the American Altos Labs with senior authors Goyal and Gary Bader — a professor at U of T in the Department of Molecular Genetics and the principal investigator at the Bader Lab — they created the artificial intelligence (AI) model Fatecode.

Using information about the genes that interact with a certain cell type, Fatecode can accurately predict which genes regulate the cell’s identity. Finding these regulatory genes traditionally requires a long and arduous process, which Fatecode could help simplify in the future.

But with AI comes all sorts of questions, including those around explainability, which is scientists’ ability to explain why a model is making the predictions that it is. Goyal thinks our approach to explaining things may change altogether.

As models become increasingly complex, it becomes harder for scientists to fully understand the reasoning behind their predictions. Some models may intentionally be kept simple, but others won’t.

“As a physicist, as a scientist, I’m always obsessed [with] what can I explain? [But] what we call an explanation may genuinely change [...] now that we can go from data to prediction without having the middle layer sorted out enough,” said Goyal.

We may find this lack of understanding acceptable in some situations, where the ultimate answer is all we care about. But beyond humans’ inherent want for explanations, not being able to understand why a model comes to a certain conclusion could cloud scientists’ ability to discern when the model’s conclusions are bogus.

Both Abou Chakra and Goyal also stressed that AI alone can’t replace modelling efforts and that modelling is more than just plugging data in and getting a prediction out. “It’s like saying, I’m going to pick one microscope to look at things, only one way to look at things,” says Goyal.

AI is great at making predictions based on vast amounts of data, for instance, but if the data inputted into the model is faulty or biased, the predictions will be too. AI is a tool in the toolbox, not the toolbox itself.

Rather, the toolbox consists of a wide variety of computational and experimental tools and, more importantly, the expertise of the interdisciplinary team at the VHD who continue to tackle the unanswered questions of developmental biology. “It’s this united front that needs to happen,” as Abou Chakra aptly put it.

At its core, the VHD is about removing barriers through bringing together disparate fields, isolated experiments, or sparking new collaborations. This electric mixture of sciences and people brings a whole new dimension of research to developmental biology and shows the importance of collaboration in science as a whole.

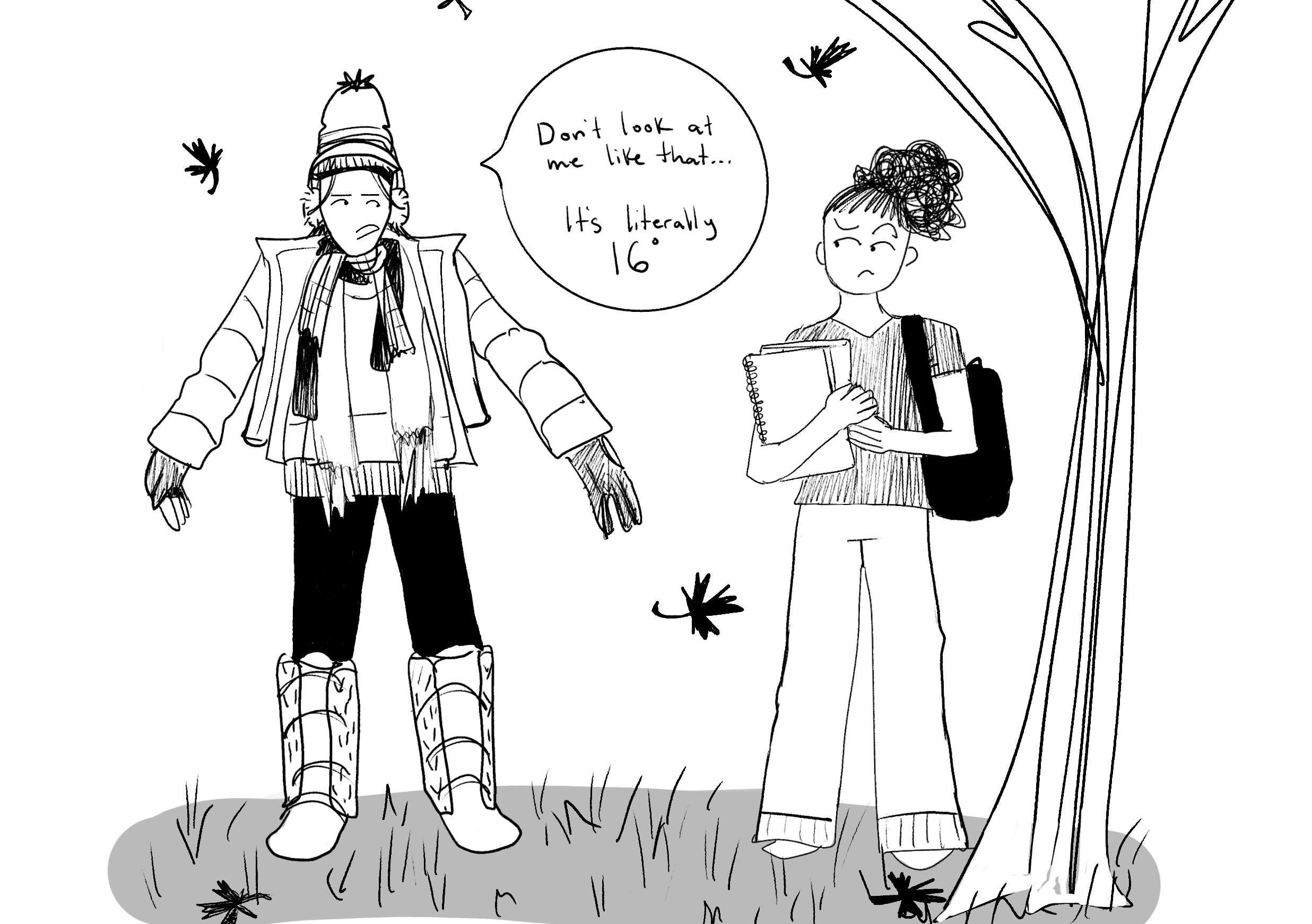

Shifting lives through languages

How multilingualism and code-switching make you fluent in more than words

merely an effort to adapt to my diverse range of environments, or a harmful way of compromising my authentic self. I wasn’t sure whether the two were one in the same.

During the stillness of the pandemic lockdown, I was chatting and laughing on a late-night call with my high school friends. At some point, my mother walked into my room and began talking to me — without thinking, my accent shifted. I exaggerated my T’s and D’s, and rolled my R’s, sounds that my friends on the phone certainly weren’t used to. They laughed, taken aback by these unexpected changes in my voice. “You sound completely different,” I remember them saying. To them, my Urdu cadence felt foreign compared to the Americanized style of speech I had used with them.

This was the first time I was called out for code-switching, a term I didn’t even know existed until a few months later. That moment became a window into a phenomenon I had been unconsciously practicing for years: ‘unrolling’ my R’s for school presentations, slowing down my speech with teachers, and thickening my American accent when I needed to project confidence.

It was only with my South Asian friends that I’d let Urdu words pepper my speech, which felt like reintroducing a sense of familiarity, as warm as my mother’s hug, to my spoken language, which had begun to feel split.

I came to realize that this constant switching of linguistic gears wasn’t just a cute quirk I occasionally caught myself doing. I became torn between whether my code-switching was

I asked myself these questions when I stepped foot on the U of T campus over a year ago. Was code-switching a survival skill, a hidden cost of belonging, or a subtle tool of oppression? Could it be all three at once?

Defining code-switching

Code-switching can be defined as the conscious or unconscious shift in language, accent, tone, or behaviour to align with different social settings.

Linguists have long studied how bilinguals have transitioned smoothly between languages, but code-switching extends beyond that. It can be the decision to smooth out your hair before a job interview, or to leave your religious pendant at home, ‘just this once.’

These are subtle negotiations made to meet the expectations of others, not just random choices for self-presentation. They reveal the pressure and costs of social acceptance.

As a 2023 University of California, Berkeley article puts it, code-switching functions as a strategic “chameleon effect ” that allows people to adapt to different social environments by shifting their speech, behaviours, and therefore how they present their identities to others. Like a chameleon blending into its surroundings, these changes can go unnoticed by those around them.

This constant practice of adapting can be both helpful and harmful, depending on how and when you use it. For some, code-switching can be used to exercise agency and strength. “[W]hen I choose to code-switch strategically, I see it as adaptability and a strength of my linguistic capabilities,” wrote Rayn Lakhani, a second-year peace, conflict and justice student, in an email to The Varsity.

For others, like second-year architecture student Obiajulu Udemgba, code-switching can feel like a form of personal erasure in favour of social acceptance. “I now mourn the elements of my cultural identity that I feel I may never get back,” Udemgba told me. “I no longer have what most would call a Nigerian accent. This seems to help my palatability when answering the cellphone or working in public services; however, it has also extinguished the linguistic element of my cultural identity that once deeply defined me.”

Personal perspective

As a Pakistani who has lived in five countries, I’ve never had the certainty of a single accent. In the US, I learned to adopt an American rhythm from my peers and teachers, which helped me blend in at school.

When I moved back to Pakistan, relatives and friends teased me when my American accent crept into my Urdu. They’d call me the burger, sometimes even the gora pakora — slang terms meaning I was too Western for my own good, or that I was a brown kid trying to act white.

Code-switching wasn’t something I planned to do; instead, it acted as a means of social survival. With friends, it allowed us to bond through shared dialects and humour; with professors, it seemed to make me ‘polished’ — I was a brown kid who could negate it with my English words.

Between being made fun of by my Pakistani friends and being praised for seeming polished in the US, I became conflicted about whether code-switching was entirely good, bad, or some muddy blend of both. Was I simply performing a different ‘self’ for different audiences? Was it possible that, by adapting, I could create the truest expression of my identity?

In my freshman year at U of T, I expected the school’s diversity to ease the burden I had begun to feel about constantly code-switching. Instead, I found new layers of contradictions in deciding whether codeswitching was harmful or helpful.

I conversed with students who spoke about ‘standard’ English as if it were morally superior, while accents carried negative presumptions.

Throughout my interviews with U of T students, I learned

Eishaal Khan

Varsity Contributor

CHLOE WESTON/THEVARSITY

that for many students, code-switching is a tool to navigate an academic system that privileges certain norms of speech and behaviour. Diversity is celebrated, but the irony is that codeswitching, often practiced by students who embody that diversity, can end up reinforcing linguistic homogeneity.

Student perspectives

Second-year English and political science student Pilar Amparo Dominguez wrote in an email to The Varsity that she felt like she was “received more positively as an international student if [she spoke] English with a standard North American accent.” Otherwise, she was immediately differentiated and met with “questions about [her] background.”

This othering is what makes some people feel obligated to code-switch. However, for Daniel Park, a second-year Korean-Canadian Rotman Commerce student, code-switching isn’t about assimilation, but negotiation. When different cultures come together, being ‘Canadian’ becomes about being “tolerant, accepting, and inclusive,” he said.

Lakhani took a more ambivalent view, seeing code-switching at U of T as an “iceberg.”

“On the surface, [code-switching] can promote inclusion because it allows people from diverse backgrounds to connect and collaborate more easily,” wrote Lakhani. “But at a deeper level, it almost feels as though students must conform to dominant narratives of speaking and being. So on an outer level, it feels like a smoother way of promoting diversity, but at the same time, concealing the pressures it takes for many students to belong.”

Gabriela Quiroga, a second-year environmental studies and political science student, who has lived in Colombia, Chile, Sweden, and now Canada, described how accents are the dominant form that her code-switching takes.

During an Uber ride with her friends, Quiroga recounts slipping into her Brazilian accent out of fatigue, saying her friend “teased [her] a little bit because of it.” But this teasing was only friendly, since Quiroga’s friend is Filipina and “has a Spanish background.” Quiroga explained that when there’s a similar cultural context, she feels more comfortable showing both aspects of her life. “It depends really on where my friends are from. If they have sort of a Latin background… I feel a bit more comfortable code-switching, and I feel like I do it automatically.”

Dominguez also described how highlighting accents in her code-switching practice allows her to connect with people of similar cultural backgrounds.

“Speaking with a Filipino accent makes it very easy to befriend other Filipinos,” she wrote, “especially those working at the coffee shops on campus. I have seen how they more easily warm up to me even if I’m just speaking English with an accent.”

Arhaan Lulla, a third-year student study-

ing criminology and political science, noticed that even his politics seemed to shift with his tongue: speaking Hindi, he felt “more conservative;” in English, “more liberal.” His experience reveals how code-switching extends beyond the phonetics of accents or grammar, and into how we think.

Professional pressures and double-edged swords

While classrooms demand more subtle forms of code-switching, professional spaces seem to require it more dauntingly. Second-year public health and psychology student Pinar Ari recounted how she avoids disclosing her cultural identity in job interviews until after she gets hired because you can never “guarantee that there won’t be any other factors… involved in the hiring other than my skills.” Ari alludes to her fear of biases that employers might have about characteristics like ethnicity or cultural background, which are irrelevant to one’s work skills.

For many students — myself included — an English vocabulary and accent have become professionalized since they are often associated with success in academic and professional settings. Having the ‘right’ language, vocabulary, and even mannerisms can get you into rooms you might otherwise never have known existed. Code-switching can thus act as a coat of armour in professional spaces. It’s a way of gaining validity with people who don’t share our cultures or languages. But armour is heavy, and constantly taking it off and putting it back on can make us fatigued, hypervigilant, and burnt out.

Lulla echoed the frustration that comes with overthinking how you’ll translate what you want to say before you say it. “If you’re just concerned about sounding a particular way, the entire point [of what you’re trying to say] is gone.” For him, clarity matters more than the sense of ‘prestige’ that comes with speaking a Westernized accent or vocabulary. I agree with Lulla — accents should be spoken with confidence, not erased out of fear.

What bothers Lulla most is the performative aspect he and his friends take on when they code-switch. When his friends moved from Bombay to Canada, they “developed an accent” which Lulla admits became irritating for him,

because it felt “like they’re putting up a show.”

Lakhani contended with Lulla’s frustration at this sense of contradiction and inauthenticity that comes from constantly code-switching. “When I choose to code-switch strategically, it feels like power. But when it’s forced, it feels like loss.”

Dominguez offered that “code-switching to fit in with the majority population could be a loss of diversity.” At the same time, she acknowledged that code-switching can also “reflect an individual’s skill and journey moving from culture to culture… As long as the code-switching isn’t a result of shame then it can showcase diversity of life experience as well.”

For many students, code-switching acts as a double-edged sword.

Cultural closeup

For South Asian students like me, slipping Urdu or Hindi slang into English conversations is a signal of cultural closeness, a shorthand that says we understand each other.

In conversations that extend beyond this subtle South Asian closeness, our slang often gets lost in translation. Lulla laughed about trying to explain jhuttha — a South Asian slang term which in this context meant once someone bites your food, you can’t finish it — to those unfamiliar, explaining that “there’s just no English equivalent.” For him, code-switching in English means the absence of entire South Asian concepts and thus moments of closeness.

For me, in those rare spaces with friends who share the same language or accent, the urge to overthink and perfect our words disappears. What’s left is a kind of relief: the freedom to simply speak, unmeasured and unperformed.

I think back to that call with my friends, when my mother walked in, and my speech changed when I talked to her. Back then, it felt like a harmful slip; a failure to conceal two divided selves I held inside. Now, I read that moment differently. Rather than a loss of one or another identity, it was evidence that identity isn’t singular; it shifts and multiplies.

In the end, Lulla said that “people should be comfortable in the way that they speak, in terms of their accents, because that will help them out in the long term. If you’re insecure about the way you speak, you’re not going to be able to communicate your thoughts.”

At U of T, code-switching has been both a gift and a burden. It has taught me how to navigate classrooms and peers fluidly, but it has also left me wondering where my cultural and linguistic performance ends and I begin. Maybe code-switching can never be deemed wholly good or wholly bad. Like a painter reaching for a new brush or palette, we shift tones to express different truths. But I think institutions like U of T have a long way to go in creating an academic space where students don’t have to code-switch to belong. Ari recalled how her parents once asked her to help them “get rid of their accents.” She pushed back: “Why would you want to? Your accent is proof you speak more than one language. That’s something to be proud of.”

Arts & Culture

September 9, 2025

thevarsity.ca/category/arts-culture arts@thevarsity.ca

Have you seen Rainbow on Mars?

Exploring theatre beyond sight in Devon Healey’s groundbreaking work

Alyssa Scocco Varsity Contributor

Have you seen Rainbow on Mars? I’m not sure that I have either — at least, I wouldn’t use those words. Rainbow on Mars is a play that challenges our assumption that vision must be our primary sense for watching a performance, even though it’s in the name of the act.

How are we to discuss experiences of theatre and dance without centring sight? At Ada Slaight Hall from August 14–20, playwright, performer, and Associate Professor of Disability Studies at Ontario Institute for Studies in Education (OISE), Devon Healey, asked us to try.

Developed over the last five years with co-directors Nate Bitton and Mitchell Cushman, Rainbow on Mars is a multidisciplinary work of theatre and ballet that calls on audiences, both blind and sighted, to question the primacy of vision in our world. Inspired by the way Healey’s writing caters to perception beyond sight alone, choreographer Robert Binet and apprentice dancers from the National

Ballet of Canada create movement sequences with such emotional clarity that they can be — perhaps even best — appreciated without sight.

Immersive Descriptive Audio

The most revolutionary element of Rainbow on Mars is also that which makes it accessible to visually impaired audiences: Immersive Descriptive Audio (IDA). Conceived by Healey, IDA acts as so much more than an accessibility feature. It is a central character as ‘The Voice’ (Vanessa Smythe), and is the philosophical centre of the production.

Unlike described-video-esque audio description, which coldly narrates visuals as they appear on the surface, IDA captures the experience of seeing, in a way not even vision can truly rival.

The IDA’s lush, poetic descriptions often felt more evocative than the visuals themselves, translating the external form of ballet into internal, embodied emotion. It proposes that to understand a dance, one must not just see it, but feel what it might be like to inhabit it.

This practice, developed with Binet, builds a parallel to the visual experi-

As a dancer myself, the highlight of my experience was listening to how The Voice described the ballet sequences. It did not name steps or describe their appearance predictably or intuitively. Rather, Smythe described the experience of dancing: the tug of energy between bodies in the space, the texture and breath of the movement.

The Voice captured the feeling of choreography more effectively than my eyes could, as if I were dancing each phrase myself. And because these descriptions were evocative rather than prescriptive, I left with a sense that, should 100 random people be given this audio, they would imagine 100 vastly different variations of the same steps, unified not by accuracy but by a shared emotional resonance.

Rainbow on Mars: the premise

The narrative follows Iris (Healey), a young woman hurled out of her old life and into a disorienting new world upon being diagnosed with a mysterious and incurable ailment affecting her vision. The performance details Iris’s journey into blindness, the relationships she builds, and her inter-

sight, and we are immediately informed through both the audio and visual design that this reality is limiting and hollow.

As a further nod to Plato’s Allegory, shadows dance across the walls thanks to the massive chandelier-like structure that hangs over the space. Equally chilling is the following doctor’s office scene, staged with cold exaggeration. Clinical voices and sterile gestures captured the disorienting mix of care and alienation that defines so many medical encounters for disabled people.

Other moments, however, felt less fully realized. The ensemble known as ‘The Sads’, meant to trap Iris in their winding, despairing choreography, did not achieve the weight they seemed to promise. Their fluid, classical phrasing created a sense of entanglement, but the dread never fully materialized.

I longed for a more contemporary vocabulary with more suspension, more collapse, more melting of time. I don’t believe that the classical ballet vocabulary used contains the full range to embody the lethargy and suffocation viscerally enough. By contrast, the dancers’ portrayal of blind joy in the flowing white slips was luminous and playful, offering an example of the efficacy that The Sads lacked.

TIFF review: In Search of the Sky

Unspoken connections in Jitank Singh Gurjar’s new film

Content Warning: This article has mentions of ableism.

In Search of the Sky — a new film from director Jitank Singh Gurjar — follows an older couple in rural India as they care for Naran (Nikhil Yadav), their adult son who has a developmental disability. While Vidya, Naran’s mother (Meghna Agarwal), spends her time at home with Naran, his father, Jasrath (Raghvendra Bhadoriya), hauls bricks to support the family because he can no longer make enough money as a musician.