THESYDNEYCHALMERS

Journal of the School of History and Philosophy of Science

MANAGING EDITORS

Laura Sumrall

Gemma Lucy Smart

Alexander Pereira

REIVEW TEAM

Patrick Dawson

Caitrin Donovan

Arin Harmann

Paddy Holt

Claire Kennedy

Samuel Lewin

Eamon Little

Gemma Lucy Smart

Laura Sumrall

Alexander Pereira

DESIGN

Joseph Matthews

The Sydney Chalmers is the undergraduate journal of the School of History and Philosophy of Science at the University of Sydney. It is a publication of The Incommensurables: the History and Philosophy of Science club at the University of Sydney. Funding for The Sydney Chalmers comes from the School of History and Philosophy of Science, and a Student Life Grant through the Faculty of Science at the University of Sydney. Special thanks to Alan Chalmers, Hans Pols and Debbie Castle.

© 2019 School of History and Philosophy of Science, University of Sydney. Apart from any fair dealing permitted according to the provisions of the Copyright Act, reproduction by any process or any parts of any work may not be undertaken without written permission from the individual author and the School of History and Philosophy of Science, University of Sydney. Enquiries should be addressed to the editors. The statements or opinions expressed in the articles in The Sydney Chalmers are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the School of History and Philosophy of Science, University of Sydney.

THE SYDNEY CHALMERS

Journal of the School of History and Philosophy of Science

University of Sydney

2019 ISSUE 1

Contents

The Incommensurables

From the Editors

Gemma Lucy Smart and Laura SumrallEarly History of History and Philosophy of Science at the University of Sydney

Alexander Pereira

Alan Chalmers Profile

Alexander Pereira

Undergraduate Showcase

Mungo Man: science, the media and the meaning of Aboriginality

Pola Cohen

Global Mental Health: a remedy for “medical imperialism”?

Clara Mills

The Galileo Affair: an analysis of Bellarmine’s letter to Foscarini

Bettina Chan

The Raven’s Paradox: does context determine the relevance of evidence?

Julian Ubaldi

Mental Health Interventions in Aboriginal Communities: suicide in the Tiwi Isalands

Pola Cohen

Is Psychology Really a Science? A critical examination of the ongoing use of significance tests in psychology

Roanna Vohralik

From the Editors

Welcome to the inaugural edition of The Sydney Chalmers.

It’s been a pleasure and a process to develop an undergraduate journal with The Incommensurables and the School of History and Philosophy of Science at the University of Sydney. Since its inception, our history and philosophy of science society The Incommensurables has been a small home for undergraduate and graduate students interested in critical studies of science. We’re mostly a social club, so it was a real treat to be able to provide an opportunity for undergraduate students to showcase their excellent work in a more formal way through this journal.

We’d like to extend our thanks to all the contributors, especially for their patience through the long editorial process. We thank the postgraduate cohort in the School of History and Philosophy of Science for their hard work during the review process. Special shout out to Alexander Pereira for stepping in to write the retrospective pieces that front our publication.

We would also like to express our gratitude for the unending support of the staff of the School of History and Philosophy of Science, especially Head of School Hans Pols and School Manager Debbie Castle. We couldn’t have done it without you. The funding that made this publication possible came in the form of a Student Life Grant through the Faculty of Science.

Most importantly, our thanks go to Alan Chalmers for his assistance with this publication, for allowing us to use his namesake, and for writing the book that started it all.

Enjoy!

Gemma Lucy Smart and Laura SumralEarly History of History and Philosophy of Science at The University of Sydney

Alexander Pereira“Over the past three decades, the various attempts which have been made at the University of Sydney to facilitate interdisciplinary studies in the history, philosophy and social studies of science and technology have provided a sorry tale of missed opportunities, misfortune, and the inevitable problems which arise when there is no back-up to a single staff-member employed to teach an undergraduate course.” – Ian Langham (1983).1

The early days of the University of Sydney’s then Unit for the History and Philosophy of Science (HPS) were characterised by quiet struggles with an uncertain identity. Both this quietness and insecurity were born of HPS’ position at the fringes of the science faculty, burdened with establishing its place and securing resources against a backdrop of fluctuating departmental enthusiasms, turbulent politics, funding woes, and internecine warfare in the neighbouring school(s) of philosophy. HPS began

as an optimistic but lonely chimera. The story begins with a call from the Australian Association of Scientific Workers (AASW) in 1941 for New South Wales students to be:

“…given some general course which would teach them the correct approach to science. Such a course might take the form of instruction in the scientific method based on examples from the history of science.”

And later, in 1943: “To secure the wider application of science and the scientific method for the welfare of society, to promote the interests of science and to maintain the status of the scientific worker.” 2

The AASW applied sustained pressure after the project was sidelined due to the war and it was spearheaded locally in 1944 by Dr R.E.D. Makinson, a lecturer in physics, and Dr Ilse Rosenthal Schneider, then a tutor in the

German department. This led to a series of lunchtime lectures in 194546 on the ‘History and Methods of Science’.3 Ilse Rosenthal Schneider had completed a PhD in physics and philosophy under Albert Einstein before fleeing Nazi Germany for Australia.4 With her contribution to those lectures, she aimed to “counteract the bad effects of too specialised a training”, “stimulate the interest in this most fascinating and so important subject” and hoped that her lectures “may lead to the permanent addition to the syllabus of ‘History and Philosophy of Science.”5,6

It appears those lectures did not continue and what followed was a period of dormancy, before an energetic awakening. In 1953, a newly formed HPS committee launched a successful bid to institute an official HPS course in the Faculty of Science. These began as private study units for third year students. Lecturers were a motley group of invited speakers, often turning over each year, and in 1959 the committee first suggested that a permanent Senior Lecturer post be introduced to helm the course. However, it took six years for the job to be formally advertised and another twenty before the role

was finally filled.7 This was an early example of a lack of bureaucratic energy which translated into a lack of departmental momentum. The HPS committee were partly to blame, too – it appears they were parochial in their hesitance to look beyond Australia for a suitable applicant. So, a string of temporary lectureships composed the interim period, which included figures such as Hugh Lacey, Louise Crossley, and Alan Chalmers. These were tenuous appointments at the most junior rung of pay. An official university document later described Louise Crossley as an “exploited temporary Senior tutor”8, another early hint at the demanding and pernicious costs of running HPS –a theme that would loom over the following decades.

Ian Langham, with a nearly complete PhD in HPS from Princeton, took the post in 1974 after Alan’s brief stint, again employed at the most junior level. Ian inherited a turbulent academic landscape. The preceding year had seen the infamous rupturing of the philosophy department into two uneasy (and confusingly titled) schools: The Department of General Philosophy, housing the controversial schism-fuelling

course on Feminism; and The Department of Traditional and Modern Philosophy, housing staff who thought the course was doing violence to academia9. In 1979, the department of General Philosophy invited Ian Langham to make his HPS course available to its students, securing the only formal association between HPS and the Arts Faculty10. HPS at Sydney was confined to the sciences. Ian’s own struggles with the bureaucracy are on display in the above epigraph. Alan Chalmers notes that:

“A major problem for Ian was the incongruity of the HPS lectureship insofar as it was not attached to any department. As a resul, there was no ready access to the normal procedures for making course additions and changes and the like.”11

Ian became the first permanent head of the program, and then in 1983, the first to fill the prophesied position of Senior Lecturer, twenty years after the job was advertised. This was tragically short-lived – Ian Langham died suddenly in 1984, aged 41.

Alan Chalmers was seconded from his own Senior Lectureship in the Department of General

Philosophy to return to HPS and run the course after Ian. The move became permanent in 1985.12 Alan reflects on his time at HPS in illuminating first-person detail in the accompanying profile. It is worth mentioning one of Alan’s most enduring contributions here: his book published in 1976 What is this thing called science?. Alan’s introduction to the philosophy of science, geared towards undergraduates and interested neophytes, had an extraordinarily powerful reach, both locally and internationally, and the book has influenced the structure of introductory HPS courses ever since. Alan’s own experience at

Image: Ian Langham of History and Philosophy of Science. Image courtesy of Debbie Castle.

HPS appear to have mirrored Ian Langham’s and Louise Crossley’s – helming the ship is a taxing job. Alan retired in 1999 at his earliest convenience but has continued to research ever since.

Some themes emerge across this half-century. Alison Turtle argues that the early days of HPS at the University of Sydney were marred by “a variety of mishaps and strategic blunders”, particularly due to a dependence on an oftenuninterested Science Faculty, HPS’ inability to forge connections with neighbouring Arts and Humanities departments, and a general streak of “non-innovation” that saw decades of undergraduate-only courses overseen by a single staff appointment. 1 But the story so far suggests that this was not from a lack of internal effort. Those entrusted with running and developing HPS were burdened with navigating departmental politics and having to justify why an interdisciplinary subject enmeshed in the humanities should exist at all in the Faculty of Science, let alone be given more resources, when adjacent schools were already providing similar programs. Regarding the bureaucratic powers-that-be, Turtle writes in 1987 that “Sydney’s policy

towards HPS has…been neither of committed aloofness, nor of realistic investment in the growth and development of the discipline”.2 For Turtle, other Australian HPS units flourished as Sydney stagnated.

Plenty has changed. This narrative of a downtrodden, low-profile, quietly struggling unit glosses over the many wins and developments no doubt made during that long half-century, by many figures not mentioned in this retrospective. Alan Chalmers, too, concedes that his account of HPS’ growth as “straightforward, onwards, and upwards” is too simplistic.3 But the present story does connect common themes of uncertainty about HPS’ place, worth, and identity. And there is now an undeniable sense of momentum within (the recentlypromoted to ‘School’ of) HPS at Sydney that feels more striking after learning of those early trials and tribulations. We now have many permanent staff appointments; some pulled from the international pool, others homegrown, all dominant in their sub-fields. We are about to recruit another. We have a robust honours and postgraduate program that attracts international attention, an enthusiastic Faculty

of Science, and world-renowned specialties in the philosophies of biology, medicine, and early modern histories of science. HPS Professor Peter Godfrey-Smith wrote an article earlier this year discussing Australia’s impressively “outsized” influence on philosophy,4 and one could comfortably argue that Sydney has had a similarly outsized influence on HPS. Alan’s What is this thing called science? is just one powerful example of that. HPS is often thought to flourish precisely because it has many feet in many scholarly doors, and that certainly seems the case now – but the tale of the early days of HPS at Sydney demonstrates how tenuous and unbalanced this situation can be.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Hans Pols, Maureen O’Malley, Peter Godfrey-Smith, and Michael Devitt for directing me to illuminating resources that were very helpful in the writing of this piece, and Amelia Scott for proofreading. In particular, I’m indebted to Alison Turtle and Alan Chalmers for their own pieces on the history of HPS at the University of Sydney.

1. Notes written by Ian Langham in support of the proposal to establish a Centre for Science, Technology and the Human Prospect within the University of Sydney; in possession of Professor R.M. MacLeod, University of Sydney. From: Alison Turtle, “History and Philosophy of Science at the University of Sydney: A case-study in non-innovation,” Historical Records of Australian Science, 7 no.1, (1987), 27.

2. Turtle, “History and Philosophy of Science at the University of Sydney,” 28.

3. Ibid.

4. “Biography of Ilse Rosenthal Schneider,” Rosenthal Schneider, Ilse (1891-1990), from Trove National Library of Australia, accessed November 2019, https://trove.nla.gov.au/ people/1305190?c=people.

5. Ilse Rosenthal Schneider, “Notes and Correspondence,” Isis, 36 (1946), 132.

6. Ilse Rosenthal Schneider, “Notes and Correspondence,” Isis, 37 (1947), 76.

7. Turtle, “History and Philosophy of Science at the University of Sydney,” 29.

8. Ibid.

9. James Franklin and George Thomas, Corrupting the Youth: A History of Philosophy in Australia, (Macleay Press, 2012).

10. Turtle, “History and Philosophy of Science at the University of Sydney,” 30.

11. Alan Chalmers, “The Beginnings of History and Philosophy of Science at the University of Sydney: Some Personal Reflections by Alan Chalmers,”, speech presented in April 2018.

12. Chalmers, “The Beginnings of History and Philosophy of Science at the University of Sydney,” 2018.

13. Turtle, “History and Philosophy of Science at the University of Sydney,” 28.

14. Turtle, “History and Philosophy of Science at the University of Sydney,” 27.

15. Chalmers, “The Beginnings of History and Philosophy of Science at the University of Sydney,” 2017.

16. Peter Godfrey-Smith, “Australian Philosophy,” Retrieved November 2019 from, https:// aeon.co/essays/why-does-australia-have-an-outsized-influence-on-philosophy.

Alan Chalmers Profile

Alexander PereiraAlan Chalmers was born in Bristol, England, in 1939. He began his academic career locally at the University of Bristol, earning a Bachelor of Science in physics in 1961, followed by a Master of Science in 1964, this time from the University of Manchester. Both degrees were in Physics. Alan then changed gears to explore a burgeoning interest in the historical and philosophical foundations of physics. He attended the University of London to study the History and Philosophy of Science, and in 1971, was awarded a PhD for his dissertation on James Clerk Maxwell’s theory of electromagnetism.

Alan won a post-doctoral Fellowship at the University of Sydney in that same year. He became enamoured with the city, began lecturing in School of Philosophy, and eventually took up a brief stint helming the Faculty of Science’s then modest HPS course for a few years before Ian Langham took the realms permanently in 1974. Alan was promoted to a Senior Lectureship in the newly (and controversially) established School

of General Philosophy. During this time, he wrote and published What is this thing called science? which became a go-to resource for introductory HPS courses the world over.

He returned permanently to the Faculty of Science in 1986 as Director of, and Professor in, the HPS unit. Alan directed the program until his retirement in 1999. Alan then continued with his work, free from the shackles of university politics, via funded research positions at Flinders University and the Center of Philosophy of Science at the University of Pittsburgh. Alan became a Fellow of the Australian Academy of Humanities in 1998, and in 2003, was awarded a Centenary Medal by the Australian Government for “Services to the Humanities in the area of History and Philosophy of Science”. He remains an Honorary staff member in the School for the History and Philosophy of Science here at the University of Sydney.

Alan reflects on his time at HPS below in a speech he presented at an event

in April 2018, which celebrated the promotion of HPS from a ‘Unit’ to a ‘School’ in the Faculty of Science.

permanent. I was offered and accepted the position in General Philosophy.”

The Fortuitous Birth of What is this thing called science?

“Ian Langham was unable to take up his new position immediately and I was employed to fill in until he was able to do so. I was the HPS lecturer for the second half of 1973. During that time there was a strike in the Philosophy Department triggered by attempts to introduce a course on Feminism. Whilst the strike was mainly an Arts Faculty affair it spread into the Science Faculty because I felt obliged to join it…An outcome of the strike was the splitting of Philosophy into two separate departments, the Department of General Philosophy and the Department of Traditional and Modern Philosophy, staffed, roughly speaking, by those comfortable, in the former case, and those that were not comfortable, in the latter case, with the new feminism course. In order that the two departments should have a viable number of staff each of them was allocated a three year lectureship, only one of which was to become

“Since the permanence of my job depended on the fortunes of General Philosophy I put much effort into my introductory course on Epistemology and Philosophy of Science for first year undergraduates. I supplied detailed notes for the students, each of the five hundred copies of the thirty pages requiring one turn of the handle of the Roneo machine, a predecessor of the photocopiers we now take for granted. When, a year or so down the track, I learnt that at least two other Australian universities were using my lecture notes I was flattered. An editor at Queensland University Press had a different, more pragmatic, response. Sensing that my lecture notes was a marketable commodity he leant on me to turn them into a book. I eventually succumbed to the pressure he exerted. As a result, the first edition of What is this thing called science? was published in 1976.”

The Chalmers Years

“In 1985 I was seconded from General Philosophy into the Science Faculty to run the HPS course. The arrangement eventually became permanent. I was fortunate that Arnold Hunt was Dean of the Faculty of Science at the time. Once I had settled into my new job he encouraged me to plan for an expansion of the HPS courses. Eventually plans for a third year course, in addition to the existing second year course, were approved by the relevant Science Faculty committee and also by the Faculty of Arts where I had another strong supporter in Sybil Jack, then Dean of that Faculty. There remained the question of staff to teach the now-approved courses. In those days the Vice Chancellor (John Ward at the time) played a much more active role in everyday academic affairs than nowadays. In particular, it was he who signed off on additions to staff in departments throughout the university. Late in 1987 that situation was about to change. Centralised power was about to be devolved at the end of the year to five sub units of the University, with each overseeing its own affairs including staffing

allocations. I did not have high hopes of a sympathetic response to a request for additional staff once that change had occurred. In mid-December, 1987, The Dean of Science, the Dean of Arts and the Senior Lecturer in History and Philosophy of Science (that is, Hunt, Jack and myself) arranged a meeting with the Vice-chancellor at which we urged him to approve an additional HPS lectureship. He ruled in our favour, and the decision to advertise a new HPS lectureship was authorised.”

“The new appointee was Michael Shortland who had a PhD from the University of Leeds. He was extremely pro-active and ambitious. His energy was akin to a rapidly rotating fly-wheel, it being my job to try to engage it with the University mechanisms. We worked effectively, if not always comfortably, as a team with the result that in the first three years of the extended HPS programme, the number of students enrolled in the programme had trebled. By that time we had a case for an additional lectureship that was too strong to be ignored. I should note that in the early years of the extended programme Michael

Shortland and I were dependent on support from a number of staff in the Science and Arts Faculties who were prepared to have their courses included on a list of options that comprised one quarter of the third year requirements. I won’t mention names because to identify those I can remember would be unfair to those that I can’t.”

“In 1994 we appointed Nicolas Rasmussen from the USA to a lectureship, thereby initiating the move towards the strength in history and philosophy of biology and medicine that has become one of the hallmarks of HPS at Sydney University. It also started our practice of snaring promising young HPS scholars from overseas. The transfers were not all one way. In 1997 two HPS students, Suman Seth and David Munns, who were able to take advantage of the Honours and Masters courses in HPS by then in place, won PhD scholarships in the USA, one at Princeton and the other at Johns Hopkins. Both have since prospered in academic positions in the States. Their success proved to be signs of things to come.”

Enough is Enough

“The rise of the fortunes of HPS was not all as straightforward, onwards and upwards as my account might suggest. There were trials and disappointments and the going could be very taxing. Just ask my partner, Sandra. As the twentieth century drew to a close I had had enough of University politics. I retired in November, 1999 on the very first day that it became financially viable to do so. My engineering brother was puzzled by my answer to his question of what I would do after retirement, but I am sure the current HPS staff will know exactly what I meant. I informed my brother that I would be getting on with my work. And that is precisely what I have done. Since retiring I have been able to devote myself to research and take advantage of ARC grants that I have been able to apply for as an honorary member of staff. While my period of employment at the University of Sydney required me to struggle hard to keep my head above turbulent waters the general flow of those waters has set me down on a rather pleasant island.”

Image: Alan Chalmers and then undergraduate student Amelia Scott at the 2017 celebration of History and Philosophy of Science becoming a formal School.

Mungo Man: science, the media, and the meaning of Aboriginality.

Pola CohenIn 1974, scientists uncovered a human skeleton at Lake Mungo, in western New South Wales. The remains were labelled ‘Lake Mungo 3’ (LM3), colloquially known as Mungo Man. Mungo Man was removed from the traditional lands of the Muthi Muthi, Paakantji and Nygiampa to a facility in Canberra, where he was originally carbon dated to be at least 30,000 years old – the oldest human remains found in Australia.1 This essay will explore the complex interplay between scientists, media and politicians following a 1990s attempt to sequence fragments of Mungo Man’s DNA. Section One will explain the study itself and contextualise it in the evolutionary debate of its time. Section Two will turn to the responses in the scientific community and the media, exploring how the two industries interacted to shape the debate. Section Three will discuss the politicisation of the Mungo Man findings in disputes over Aboriginal rights and how this reshaped the focus of later studies of LM3. Section Four will consider the ethical problems with scientific use of Aboriginal DNA. The complex layers

of meaning embedded in Mungo Man’s genetic identity draw together science, politics and Aboriginality, demonstrating the entanglement of science and society, and the need for scientists to consider the potential for their work to be misunderstood and misused.

Section One: Mungo Man and the Debate over Human Evolution.

By the 1990s, two major theories offered competing explanations of human origins, which are key to understanding the debate over Mungo Man. According to the Recent Out of Africa theory, Homo sapiens evolved from Homo erectus exclusively in subSaharan Africa. They left it 100,000 to 200,000 years ago and colonised the rest of the world over the intervening millennia, wiping out other species like the Neanderthals.2 In contrast, the Regional Continuity theory (or Multi-regionalism) posits that our Homo erectus ancestors left Africa two million years ago and evolved into

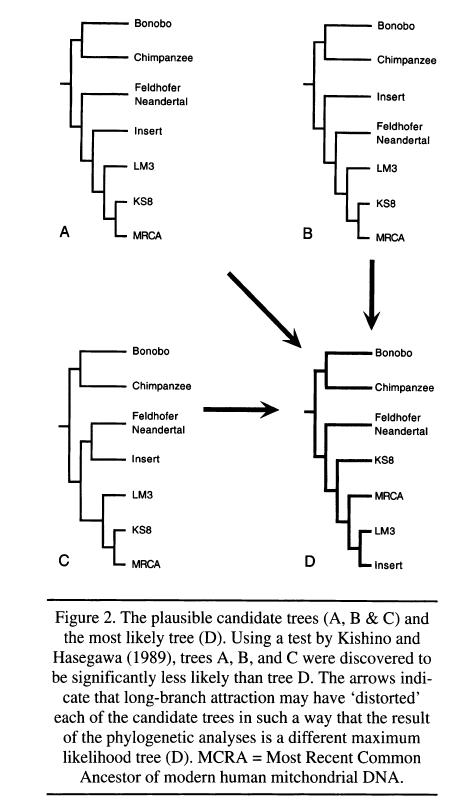

Homo sapiens simultaneously across different parts of the globe, with interbreeding guaranteeing genetic and morphological similarity between different peoples.3 Colin Groves and Alan Thorne, members of the team who uncovered the LM3 remains in 1974, were each strong proponents of one of these theories – Groves supported Recent Out of Africa, whilst Thorne argued for Multiregionalism.4 In 1995, doctoral student Gregory Adcock brought Mungo Man into the debate in a study undertaken with Thorne’s supervision. His team extracted mtDNA from LM3’s bone fragments, comparing it to a reference mtDNA insert sequence (a remnant of an extinct mtDNA lineage found in some living humans’ 11th chromosome), as well as mtDNA from other ancient remains, a range of living Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal humans, and other primate species. The extracted mtDNA grouped with the insert sequence. From this, the authors concluded that it was possible that LM3’s lineage diverted from modern humans before our MRCA (most recent common ancestor), meaning that modern humans may have evolved in Australia independently of the evolution of all humans alive today (see Figure 1). This appears to challenge the Out of Africa theory.5 Their 2001 paper set out the study’s

conclusions tentatively: despite media reports to the contrary, the authors did not say that human life originated in Australia, and they retained the possibility that LM3 was an ancestor of modern Aboriginal Australians (issues I will return to later). Instead, the paper claimed to challenge the recent Out of Africa model of evolution, supporting Regional Continuity Theory instead.6 Nevertheless, the study ultimately stimulated an intensification of the human origins debate.

Section Two: The Scientific and Media Responses

The scientific community’s response to Adcock’s findings was, for the most part, somewhat sceptical. This was partly due to methodological concerns. Given the technology available in the 1990s, successfully extracting mtDNA from 40,00060,000-year old remains (the posited age at the time) seemed somewhat unlikely. Smith et al. pointed out that Lake Mungo’s humid environment was unlikely to have preserved mtDNA for that period at all.7 Indeed, other researchers had failed to assign a biological sex to the LM3 skeleton because of the fragmented nature of the DNA remnants. Furthermore,

Figure 1. Adcock, Gregory J., Elizabeth S. Dennis, Simon Easteal, Gavin A. Huttley, Lars S. Jermiin, W. James Peacock, and Alan Thorne. ‘Lake Mungo 3: A Response to Recent Critiques’. Archaeology in Oceania 36, no. 3 (2001): 170–74. ‘Insert’ refers to the mtDNA sequence inserted into some modern humans’ 11th chromosome, a remnant of an extinct mtDNA lineage.

despite the original paper’s strong assertions that great care was taken to avoid contaminating samples during their research, the LM3 remains had been handled and studied multiple times over more than twenty years – the mtDNA supposedly extracted from LM3 could have actually been a combination of damaged ancient DNA and contaminants from previous studies.8 Concerns were also raised over Adcock’s conclusions. For example, LM3’s grouping alongside the insert sequence may have been due to homoplasy – convergence in characteristics over time, independent of common ancestors.9 Responding to Adcock’s paper, Cooper et al. ultimately dismissed any challenge to the Out of Africa theory, as the paper’s phylogenic trees still showed a clear distinction between Neanderthals and modern humans, which makes the interbreeding aspect of the Multiregionalism theory unlikely (see Figure 1).10 Groves points out that LM3’s distinct mtDNA doesn’t necessarily point to an entirely different lineage of humans.11 Rather, at any point in the past there have been multiple women with distinct mtDNA alive, but the variation between mtDNA decreases because mtDNA is not passed on to male children. LM3 may represent a genetic lineage that did not survive to the present, but this does not mean

that his entire population was replaced. Groves concluded that Adcock et al.’s “conclusions, relatively restrained though they are compared to the way in which the news media reported them, cannot be accepted.”12

As Groves implied, Australia’s mainstream media disseminated the Adcock paper’s conclusions with far less cynicism – and often, with a poor understanding of the science. Many articles (though not all) represented the results as conclusive in the evolutionary debate. For example, The Australian asserted that Mungo Man was part of “a group of Aboriginal people whose genetic line has vanished from the Earth,” and that this made the Out of Africa theory untenable, without any reference to other scientists’ critiques.13 Brisbane’s Courier Mail also claimed that the study “potentially blows away the ‘Out of Africa’ theory,” instead supporting Multi-regionalism – though it briefly alluded to one unconvinced archaeologist near the end of its article on the findings.14 Several other articles suggested that, in light of the new findings, scientists now thought that humans originated in Australia: one begins, “if Adam and Eve existed, Australia could have been their Garden of Eden, genetic analysis suggests” – despite the fact that the

genetic analysis had suggested nothing of the sort.15 Much of the media’s insights into the science came from anthropologist Alan Thorne – the aforementioned proponent of Multiregionalism, and one of the key authors on the Adcock paper. In statements to various news outlets, Thorne expressed his Multi-regionalist position with more conviction than a scientific journal would allow: “a simplistic Out of Africa model is no longer tenable.”16 This, perhaps, explains the subsequent escalation of the debate within the scientific community. As well as some of these journalists having a limited understanding of the probabilistic nature of science, scientists themselves were making strong claims about their findings in the media. The media coverage then seems to have intensified the strength of scientific critiques of the original research, as in Groves’ and Cooper et al.’s work, above. The very interaction of scientists and journalists appears to have escalated the controversy over Adcock et al.’s conclusions.

Section Three: the Politicisation of Mungo Man’s mtDNA.

One strand of media coverage proposed that Mungo Man’s mtDNA meant that Aboriginal peoples had

also colonised and wiped out an earlier race in Australia, bringing it into an historical-anthropological debate over the evolutionary origins of Aboriginal people. These journalists’ interpretation of the data is, to some extent, plausible: they inferred that if Mungo Man was not related to modern Aboriginal people, then his ‘race’ must have somehow died out and been replaced by the ancestors of modern Aboriginals. This would mean that Aboriginal people were not the first Australians. It is worth noting that Thorne clearly argued against this view in his media interviews – he stated that Mungo Man was “definitely among the ancestors of modern Aborigines” and expressed similar sentiments in various other statements to the press, basing this view on morphological similarities between Mungo Man and modern Aboriginal people.17 Nonetheless, the idea that Aboriginal people weren’t ‘first’ took hold in conservative newspapers like The Australian. An article published in January 2001, titled “Modern Aborigines ‘not the First Australians’ - MUNGO MAN,” exemplifies this approach. The article assumed Adcock et al.’s findings to be conclusive, and presented them alongside other evidence which could suggest multiple waves of immigration to Australia, such as the relatively recent

arrival of dingoes and stylistic changes in rock art.18 It implied that later waves of immigration – presumably the ancestors of contemporary Aboriginal peoples – wiped out previous occupants. If this is the case (or so the article seems to suggest), then the history of Aboriginal peoples is re-cast as a narrative of colonisation, rather than of being colonised. All of the scientists quoted in this article disagree with its interpretation of the data, making similar claims that replacement of one population by another is over-simplistic and not supported by the data. Nevertheless, the article concludes that “something significant definitely occurred” involving multiple waves of migration to Australia.19 The Australian was not alone in these kinds of assertions – the Sun-Herald, too, said that “later arrivals from Africa killed off Mungo’s version of modern man just as we continue to kill each other today.”20 This kind of media coverage served to delegitimise Aboriginal peoples’ indigeneity and downplay the significance of colonisation, by suggesting that contemporary Indigenous Australians’ ancestors had done the same thing to earlier peoples as Europeans had done to them.

These questions over the nature of Aboriginality brought Mungo Man’s DNA into the political arena. To give

some context, in the early-to-mid20th century anthropologist Joseph Birdsell had put forth the “trihybrid theory” of human origins in Australia. He postulated three successive waves of immigration with distinct morphologies, the first 40,000 years ago and the most recent 15,000 years ago, with each new wave “colonising” the last.21 Historian Keith Windshuttle continued to support this theory into the 21st century, arguing that Aboriginal rights movements had deliberately repressed the trihybrid idea in order to support pan-Aboriginal rhetoric.22 In actuality, the trihybrid theory draws almost exclusively on flawed craniological evidence, lacks any evidence for its assertion that Australia was once populated by ‘pygmies,’ and has not held up to DNA testing.23 Its disappearance was not due to ‘repression’ by Aboriginal activists, but the weight of scientific counterevidence. Groves – Thorne’s academic rival in the evolutionary debate – argued that the trihybrid theory, along with other hypotheses of pre-Aboriginal Australians, was simply the political fodder of the far right. For proponents of these views, however, Mungo Man’s mtDNA is proof that “Aborigines were not the first possessors of Australia so the land doesn’t really belong to them

and the whites needn’t feel too bad about dispossessing them.”24 Groves asserted that the 2001 findings fed into the rhetoric of parties like One Nation, and allowed Prime Minister John Howard to refuse to apologise for the Stolen Generations.25 Members of the political right did continue to draw on Adcock et al.’s findings to support conservative positions in Aboriginal affairs. For example, in 2015 Liberal Democrat David Leyonhjelm took a stance against constitutional recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians on the grounds that they may not have been the first cultures in Australia.26 This way of questioning Aboriginal peoples’ status as the ‘first’ Australians in order to dispute legislative changes is highly reminiscent of Windshuttle’s own argument, which effectively aimed to challenge Native Title rights.27 Of course, Aboriginal peoples’ rights to Country, or to recognition in the Constitution, have little to do with ancient DNA. The important and indisputable point is that they were here before European invasion, that Europeans took the land and eroded their cultures by force, and that the land has never been ceded to white Australia. Nevertheless, this use of the Mungo Man findings by Leyonhjelm and others demonstrates the broader potential for the misunderstanding

and misuse of scientific findings to support political agendas.

By the time of Leyonhjelm’s comments, however, a growing body of evidence seemed to confirm that Adcock et al.’s 2001 study had been deeply flawed. In 2011, the first full-genome study using Aboriginal bio-matter found strong evidence that modern Aboriginal people are the direct descendants of the oldest humans known to have lived in Australia.28 They concluded that “Aboriginal Australians likely have one of the oldest continuous population histories outside sub-Saharan Africa today,” clearly contradicting views like Leyonhjelm’s and Windshuttle’s.29 Of course, Adcock et al. conceded that Mungo Man could have been a direct ancestor of modern Aboriginals whose mtDNA lineage happened to die out.30 Indeed, as mentioned above, Thorne asserted that modern Aboriginal people were certainly descended from Mungo Man’s people, given their morphological similarities.31 However, later studies suggested that the mtDNA extracted from Mungo Man was actually contamination from scientists handling the remains.32 An attempted replication of the original study in 2016 – using superior technology – was unable to extract any recoverable mtDNA from the

LM3 remains, other than evidence of contamination from five different Europeans.33 Interestingly, the 2016 paper contextualised Adcock et al.’s findings within the debate over Aboriginal people’s origins, rather than global evolutionary theory (although they do note that their own findings are consistent with the Out of Africa hypothesis). The politicisation of Adcock et al.’s findings therefore seems to have transmitted back into the scientific meaning of the data, to the point that the political debate became the focus of the scientific controversy itself

Section Four: Science, Ethics, and Indigenous Biomatter.

It is worth noting that the entirety of this debate – in both the media and the scientific community – drew only on Western frameworks, to the exclusion of Aboriginal knowledges. Both the Out of Africa theory and Regional Continuity theory are incommensurable with Aboriginal beliefs about their origins. Dreaming stories, according to archaeologist Martin Porr, “imply that people are so intimately connected to Country that they are one and the same, and thus neither ‘arrived’ nor came from somewhere else.”34 The scientific

debate was therefore largely irrelevant to Mungo Man’s own people. Indeed, when the Adcock study was overturned in 2016, Muthi Muthi Elder Mary Pappin told the press that she “didn’t think Australian Aborigines weren’t the first people” in Australia.35 The apparent DNA evidence of preAboriginal people meant little to these Aboriginal people – DNA did not change their identity or connection to Country. This is troubling, as it shows that the use of Aboriginal bio-matter in the supposedly neutral, universally beneficial enterprise of science, is incommensurable with Aboriginal knowledges and therefore does not benefit Aboriginal people in the same way as non-Aboriginal people. Even more concerning, it seems that Adcock et al. may not have received consent from Aboriginal people to study the LM3 remains – despite the scientists’ claims to the contrary.36 One article at the time reported that Elders were shocked by the lack of consultation over the use of their ancestor’s remains, having only found out about the study the day before its findings were published.37 Reardon and TallBear have previously raised similar criticisms regarding the scientific use of indigenous DNA in America.38 They describe a conflict between the Havasupai people, who had given

consent for their biological materials to be used for diabetes research that could directly benefit the tribe, and teams of scientists who appropriated that DNA for a range of other studies on the grounds that advancing scientific (i.e. Western) knowledge is an intrinsic good. In this instance, the Havasupai people had little to gain from the research and much to lose. As in Mungo Man’s case, DNA research “alters the parameters of indigeneity” in a way that may jeopardise land claims or asserting indigenous rights.39 While scientists used Mungo Man to investigate questions situated in Western frameworks of knowledge, the Traditional Owners of Lake Mungo were campaigning for his remains to be returned home.40 Scientists’ faith in their own knowledge system and their belief that science is an objective good arguably blinds them to its socio-political impact and its cultural exclusivity.

Conclusion

Debates over Mungo Man’s mtDNA make it clear that science cannot claim to be disconnected from society or from politics. Its reputation as a factgenerating enterprise gives science a powerful role in the political arena, as was made clear in Windshuttle’s

and Leyonhjelm’s use of scientific theories to dispute Aboriginal rights. Likewise, although science can generate interesting and important insights into who we are as human beings, using indigenous data to do so is problematic. This is so in the Mungo Man case because this kind of Western knowledge has little bearing on Aboriginal self-understandings, and because it raises ethical concerns over consent and ownership of ancestral DNA, as well as questions about who science is for. Aboriginal people had little to gain from these DNA studies. By the time Mungo Man was finally repatriated in 2017, what began as a scientific controversy had become highly politicised, warped by media misrepresentations and by scientists’ exaggerations of the certainty of their findings. Although the remains are now back on Country, the concerns this controversy raises over the potential for scientific findings to be misunderstood and distorted remain pressing issues in contemporary science reporting. The manipulation of Mungo Man’s mtDNA to delegitimise Indigenous Australians’ claims to land and sovereignty shows the potential for science to be turned from a valueneutral search for truth to an attack our society’s most vulnerable people.

1. Jim M. Bowler and Alan G. Thorne, “Human remains from Lake Mungo: discovery and excavation of Lake Mungo III,” The Origin of the Australians, eds. R.L. Kirk and A.G. Thorne (Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies, 1976), 127-38. In the 1990s, another study dated Mungo Man to 60,000 years old. This was disputed, and consensus is now at 42,000 years.

2. Martin Porr, “Lives and Lines: Integrating Molecular Genetics, the Origins of Modern Humans, and Indigenous Knowledge,” in Long History, Deep Time: Deepening Histories of Place, eds. Ann McGrath and Mary Anne Jebb (Canberra: ANU Press, 2015), 203-220.

3. Gregory J. Adcock, Elizabeth S. Dennis, Simon Easteal, Gavin A. Huttley, Lars S. Jermiin, W. James Peacock, and Alan Thorne, “Mitochondrial DNA Sequences in Ancient Australians: Implications for Modern Human Origins,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 98 no. 2 (2001): 537–42; Colin Groves, “Australia for the Australians,” Australian Humanities Review, June 1, 2002, http://australianhumanitiesreview.org/2002/06/01/australia-for-theaustralians/.

4. Leigh Dayton, “Mungo Man,” ABC Science, January 1, 2001, http://www.abc.net.au/ science/articles/2001/01/01/2813404.htm.

5. Adcock et al., “Mitochondrial DNA Sequences in Ancient Australians.”

6. Ibid.

7. Colin I. Smith, Andrew T. Chamberlain, Michael S. Riley, Chris Stringer, and Matthew J. Col, “The Thermal History of Human Fossils and the Likelihood of Successful DNA Amplification,” Journal of Human Evolution 45 no. 3 (2003): 203-217.

8. Alan Cooper, Andrew Rambaut, Vincent Macaulay, Eske Willerslev, Anders J. Hansen, Chris Stringer, Gregory J. Adcock, Elizabeth S. Dennis, Simon Easteal, Gavin A. Huttley, et al., “Human Origins and Ancient Human DNA,” Science 292 no. 5522 (2001): 1655–56.

9. Ibid.

10. Ibid.

11. Colin Groves, “Lake Mungo 3 and His DNA,” Archaeology in Oceania 36 no. 3 (2001): 166–67.

12. Ibid.

13. Leigh Dayton, “DNA Clue to Man’s Origin - How Mungo Man Has Shaken the Human Family Tree,” The Australian, 2001.

14. Brendan O’Malley, “Mungo Man Climbed out of a Different Gene Pool,” The Courier Mail, 2001.

15. Bronwyn Hurrell, “Aussie Eden Theory; Mungo Man Sheds Light on Evolution,” Herald Sun, 2001.

16. Leigh Dayton, “DNA Clue to Man’s Origin - How Mungo Man Has Shaken the Human Family Tree,” The Australian, 2001.

17. Bronwyn Hurrell, “Aussie Eden Theory; Mungo Man Sheds Light on Evolution,” The Herald Sun. Also see Frank Walke, “When It Comes to the Bare Bones, We’re Fair Dinkum,” The Sun-Herald, January 14, 2001; and Penny Fannin, “Mungo Jumbo,” The Age, January 13, 2001.

18. Unknown Author, “Modern Aborigines `not the First Australians’ - MUNGO MAN,” The Australian, 2001.

19. Ibid.

20. Walke, “When It Comes to the Bare Bones, We’re Fair Dinkum.”

21. Keith Windshuttle and Tim Gillin, “The Extinction of the Australian Pygmies,” June 1, 2002, http://quadrant.org.au/opinion/history-wars/2002/06/the-extinction-of-theaustralian-pygmies/.

22. Ibid.

23. Joe Dortch and Michael Westaway, “Who We Should Recognise as First Australians in the Constitution,” The Conversation, March 13, 2015, http://theconversation.com/who-weshould-recognise-as-first-australians-in-the-constitution-38714; Groves, “Australia for the Australians.”

24. Groves, “Australia for the Australians.”

25. Ibid.

26. Louise Yaxley, “Leyonhjelm Questions If Aboriginal People Were First Occupants of Australia,” ABC News, June 25, 2015, http://www.abc.net.au/news/2015-06-25/davidleyonhjelm-raises-doubts-over-aboriginal-occupants/6572704.

27. Dortch and Westaway, “Who We Should Recognise as First Australians in the Constitution.”

28. Morten Rasmussen, Xiaosen Guo, Yong Wang, Kirk E. Lohmueller, Simon Rasmussen, Anders Albrechtsen, Line Skotte, Stinus Lindgreen, Mait Metspalu, Thibaut Jombart, et al., “An Aboriginal Australian Genome Reveals Separate Human Dispersals into Asia,” Science 334 no. 6052 (2011): 94–98.

Ibid.

30. Adcock et al., “Mitochondrial DNA Sequences in Ancient Australians.”

31. Walke, “When It Comes to the Bare Bones, We’re Fair Dinkum.”

32. Iain Davidson, “FactCheck: Might There Have Been People in Australia Prior to Aboriginal People?” The Conversation, June 30, 2015, http://theconversation.com/factcheck-mightthere-have-been-people-in-australia-prior-to-aboriginal-people-43911.

33. H. Heupink, Sankar Subramanian, Joanne L. Wright, Phillip Endicott, Michael Carrington Westaway, Leon Huynen, Walther Parson, Craig D. Millar, Eske Willerslev, and David M. Lambert, “Ancient MtDNA Sequences from the First Australians Revisited,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 113 no. 25 (2016): 6892–97.

34. Porr, “Lives and Lines.”

35. Dani Cooper, “New DNA Technology Confirms Aboriginal People as First Australians,” ABC News, June 7, 2016, http://www.abc.net.au/news/science/2016-06-07/dnaconfirms-aboriginal-people-as-the-first-australians/7481360.

36. Adcock et al., “Mitochondrial DNA Sequences in Ancient Australians.”

37. Trudy Harris, “Mungo Mad - Search for the Origin of Man,” The Australian, 2001.

38. Jenny Reardon and Kim TallBear, “‘Your DNA Is Our History’: Genomics, Anthropology, and the Construction of Whiteness as Property,” Current Anthropology 53 no. S5 (2012): S233-245.

39. Ibid.

40. Miki Perkins, “The Long Way: Fire and Smoke for Mungo Man and the Ancestors on Their Road Home,” The Age, November 17, 2017, https://www.theage.com.au/national/ victoria/the-long-way-fire-and-smoke-for-mungo-man-and-the-ancestors-on-their-roadhome-20171116-gzn45a.html.

Global Mental Health: a remedy for “medical imperialism”?

Clara MillsThe push for Global Mental Health (GMH) – made over recent decades by international bodies such as the World Health Organisation (WHO) – has been labelled by some critics as a form of “medical imperialism” and “epistemicide”.1 They argue that calls to increase ‘mental health literacy’ globally are in reality calls for the world to firmly subscribe to Western understandings of mental health and implicitly renounce other, perhaps more locally appropriate, “ways of knowing and responding to distress”.2 There are concerns that this will lead to the loss of alternative knowledge sources; that it will pathologize natural responses to different, perhaps unstable and less wealthy, environments; and “erode kinship-based and indigenous systems of support”.3 However, these feared damages from GMH have to an extent already been incurred through the forces of classical imperialism. The export of 19th-and 20th-century Western understandings of mental illness can be seen, concretely, in the institution of asylums across European empires; these asylums are,

in some cases, still in use today.4 The foundations of many present mental health services outside the West have been “organically linked” to this imperial practice.5 India represents a particularly grave example of this: a burdensome imperial asylum system has been recycled post-independence due to resource scarcity and thus remains the nation’s largest public provider whilst an unregulated private sector fills the gaps for alternatives such as community-based care.6 This formative influence has even been recognised in countries that never directly experienced imperialism directly such as Thailand.7 Thus, if Western approaches to mental health have already had such a defining impact on existing services in many countries, could elements of the GMH movement – particularly its focus on providing community-based services – in fact, help repair some of the damage done by classical imperialism? Rather than reject the GMH movement as simply imperialist, it could be seen as a vehicle for

adapting the systems established by classical imperialism to better serve local communities. For example, affected countries could be aided in moving on from services based on outdated Western practices that have since been disavowed as “ineffective and inhumane” and in violation of the largely post-imperial concept of human rights.8 This would primarily be argued with regard to one of the major aims and ‘Grand Challenges’ of the GMH movement: the provision of effective Community-Based Mental Health Services (CBMHS).9 There is significant consensus that CBMHS are more effective and humane than institutionalisation and thus have been regarded as a necessary forefront of mental health services in the West since the 1970s. Additionally, CBMHS are likely more amenable to “kinship-based and indigenous systems of support” and better able to integrate local knowledge and treatment.10 In this way, communitybased services have the potential to repair some of the epistemological damage of imperialism by facilitating the reintegration of local alternatives to Western treatments. At the very least, they represent a more humane alternative to recycling imperial imports such as asylum-based care. This essay will explore the impact

of classical imperialism on the development of mental health services in four South Asian countries and assess whether this has produced a reliance on an asylum-style system at the expense of alternatives such as CBMHS. The chosen nations – India, Singapore, Thailand and Nepal –embody a range of socio-economic conditions as well as imperial experiences. India and Singapore both experienced direct imperial rule under the British; however, this rule lasted more than a decade longer in Singapore during a vital period of global change following the Second World War. Neither Thailand nor Nepal experienced direct rule within their modern borders; however, Thailand directly sought Western influence in the development of their services from at least the 19th century whilst Nepal was largely uninfluenced until the mid-20th century. This selection of case studies intends to demonstrate how extensively Western influence affected the development of mental health systems in some non-Western countries, even those never directly subjugated by a Western power. From this basis, it is argued that much of the feared epistemological damage of the GMH movement has already been incurred and that some of GMH’s ‘Grand Aims’ should,

in fact, be pursued to remedy this –particularly in countries burdened by mental health institutions based upon outdated Western practices.

India

India has faced a unique set of challenges in providing effective mental health services: it’s not only burdened by poverty, inequality and insufficient resources to fund basic services, but the Indian state also attempts to unite an array of diverse groups with diverse needs, and historic rivalries, across the entire subcontinent that it spans. British imperial rule in India has been a topic of extensive academic interest both in exacerbating the aforementioned challenges and in establishing the foundation for its modern mental health system which continues in poor condition.11 It should be noted that the effectiveness of India’s mental health system does vary across the state, as did the impact of imperial rule, particularly in areas where it was indirect, such as the princely states. Nevertheless, the influence of the British Raj echoed across the subcontinent: for example, on a national level, the 1912 Indian Lunacy Act – an imperial relic – remained India’s guiding mental health legislation until 1987.12

India’s system of asylums was also a direct product of British Raj, which erected the first of these in Calcutta in 1787. 13 Many asylums built under imperial rule are still in use, with some remaining unchanged since.14 Originally, asylum admissions were initiated only by British and, earlier, East India Company officials, but these institutions were later adopted by local communities and families as a means to shift the burden of care of “non-productive members” onto the governing system – a practice that still continues today.15 In the last decades of British rule there were calls to reform this system and to at least raise conditions close to the standards in England. The poor state of India’s asylums was illuminated in 1943 through the findings and recommendations of the Bhore Committee, set up to address these issues.16 However, there were neither the financial resources nor “political inclination” for the British to act on most recommendations, and following India’s independence in 1947 these issues were dwarfed by the demands of state-building following the horror of partition.17 Consequently, India was left with an asylum system, deemed ineffective and inhumane even by the standards of the time, as its major public mental health service.

This system remained the primary public service until the 1970s when Indian psychiatrists sought influence from, and collaborated with, the World Health Organisation and other international institutions, in what they considered to be an essential marker of modernisation.18 Indian psychiatrists also sought training in Western institutions and imported their curricula. However, these new Western practices were then privatised during an era of neoliberal reforms.19 This reportedly poorly regulated private sector has become “the de facto face of community care” whilst the poor majority’s primary access to public mental health care remains the outdated mental hospitals, that are generally avoided “due to their association with custodial care and human rights abuse”.20 In this case, some Indians have returned to older healing practices, but others are still involuntarily admitted by burdened communities and families into hospitals.21 This de facto division of services could potentially produce conceptions of mental health in India that diverge along class lines, with those able to afford private services being socialised into Western ideas whilst poorer people sustain local or imperial knowledge. Overall, British rule in India undoubtedly had a formative effect on its existing

mental health services. The reliance on recycled imperial asylums during a particularly resource-scarce postindependence period appears to have embedded these institutions into India’s public system and community practice – eroding “kinship-based and indigenous systems of support” and contributing to “epistemicide” –whilst CBMHS largely remain a luxury for the minority that can afford it.22 The case of India demonstrates how deeply Western approaches to mental health have already diffused into some non-Western contexts through classical imperialism. Furthermore, it presents a case in which the GMH movement, through its focus on CBMHS provision, could foster the reintegration of local knowledge into the public health system or, at least, support the movement away from outdated Western practices such as asylum care Singapore

Singapore’s imperial experience was significantly different to India’s and has ultimately allowed it to develop a more effective and humane mental health system. For one, Singapore was utilised as a centre for trade rather than primarily an area of extraction,

leaving it in a better economic position post-independence. Additionally, independence wasn’t gained until 1959, more than a decade after India – and thus, Singapore had sufficient time to reap some of the benefits of a changed global context. As a citystate, Singapore is also conceivably more easily governed. The first asylum was built by the British in 1841: though more than fifty years after India’s it had similarly meagre conditions, such as poor sanitation that resulted in high fatality rates.23 However, following World War Two – and a brief period of Japanese rule – the British approached Singapore and its other colonial possessions differently. Decolonisation had become a major concern of the U.S. and the United Nations, established in 1945, and Britain’s power and resources had been damaged by the war; therefore, maintaining an empire was increasingly unfeasible. As a result, Britain had a vested interest in aiding the development of viable institutions in its colonies and establishing good relations, in order to maintain influence and access in various world regions. Thus, during the 1940s and 50s Britain sought to modernise the institutions of the future Singaporean state, including its mental health services.24 This meant a reduction of the role of asylums and

instead a focus on the development of Community Based Mental Health Services (CBMHS).25 Five outpatient clinics were established in Singapore during the 1950s – the first in 1953, six years before self-rule.26 Following independence, Singapore sent future psychiatrists to London for training, and in 1983 received aid from the UK in setting up the state’s first Master of Medicine (Psychiatry) at the National University.27 Through these means, Singapore kept abreast with successive developments and rewrites in the Western mental health system it had inherited. Singapore’s modern mental health services have, like India’s, been based primarily on Western practices imported through classical imperialism; and as such, much of the feared epistemological damage of GMH has already been incurred. However, Singapore’s later decolonisation and more favourable economic conditions have allowed these imported institutions to be better reformed to contemporary standards and for CBMHS to be established as common practice over asylum-based care.28 Thus, Singapore’s mental health services are not only already based on Western practices but also already aligned with significant aims of the GMH movement.

Neither Thailand nor Nepal experienced direct imperial rule within their modern-day borders, however, the development of mental health services in Thailand was heavily influenced by British imperial practices in Singapore. Thailand’s Siamese Kings, reportedly, “pursued an active policy of adopting Western knowledge and techniques” from the mid-19th century.29 This policy adoption coincided with a major enlargement of the asylum system across the British Empire.30 Thailand’s first asylum was built in November 1889 and was inspired by ‘The Lunatic Asylum’ in Singapore, which King Rama V visited in 1871.31 In 2019, Thailand plans to celebrate “one hundred and thirty years of psychiatry” as it dates its inception to the building of this Western-style asylum.32 Before its establishment, Thai treatment of mental illness was based in traditional Siamese medicine such as “local herbs and Thai massage” and only rarely involved custodial-style care.33 Although no other asylums were built until 1937, between 1889 and 1909 detention, along with these traditional medicines, became a “primary treatment method” and reportedly a “Western-influenced administration system was also implemented”. 34

Much as in Singapore, Thai doctors sought training in Western institutions, though much earlier: training began from 1927, with the first course in psychiatry was “devised in 1933”.35 This led Thai doctors to import contemporary Western practices themselves, such as fever therapy in 1937 and later CBMHS. Thailand’s first CBMHS facility opened in 1964, along with a “rehabilitation village” and the introduction of day facilities at its first asylum.36 Thus, though never directly colonised, Thailand’s leaders voluntarily chose to develop their mental health systems in line with the West, based on British practices in South Asia. As this was voluntarily pursued, it continued from its initial base in asylum-centred care to CBMHS and, at least initially, incorporated traditional medicines rather than supplanting them. Like Singapore, Thailand also had the resources to maintain and develop its voluntarily imported services in response to changes in accepted practices; and as a result, its services similarly already align with some of the aims of the GMH movement such as the provision of CBMHS.

Nepal

Unlike in India, Singapore and Thailand, specific services targeting mental health were only officially established in Nepal in the late 20th century – after successive advances in Western approaches to humane and effective treatment. As a result, CBMHS were set up before mental hospitals and remain the primary source of public care.37 Before the first outpatient service was set up in 1961, public services were available only “in a general hospital setting”.38 Nepal’s first mental hospital was established only in 1984, and even then was “organisationally integrated with mental health outpatient facilities”.39 As “the poorest country in South Asia” this development was also likely influenced by Nepal’s practical limitations in resourcing different forms of care.40 This economic situation – along with the 1996- 2006 internal conflict that displaced and killed thousands – has frustrated the development of mental health services across the country.41 The majority of Nepal’s services are centred in its capital, Kathmandu, whilst many of its districts remain without official support. However, this disparity, paired with the delayed development of public services, has meant that “traditional healers and/

or religious leaders [remain] a primary source of mental health treatment”.42 Overall, the absence of direct imperial rule – in combination with economic and political factors – has meant adoption of Western practices in Nepal primarily occurred postdeinstitutionalisation. Thus, CBMHS have been prioritised over mental hospitals and traditional healing practices have survived, remaining a key source of care.

Conclusion

These histories demonstrate how significantly Western understandings of mental health have already influenced the institutions of many non-Western countries through the impacts of classical imperialism, even in countries never directly controlled by a Western power. This foundational influence is seen most clearly in the contrast of India and Nepal’s services: resource scarcity has frustrated the development of mental health services in both countries, however, as Nepal was unburdened by an imperial-asylum system its current public services still embody a mix of modern Western practices and local practices. Conversely, in India poor economic conditions impeded efforts

to move on from an outdated and inhumane asylum system imported under British Raj. Historically, service withdrawal has created new problems: in the West “re-institutionalisation” saw the closure of asylums lead to an increased prison population as ex-patients struggled without care. Therefore, the provision of effective and humane alternatives to inherited imperial systems are necessary. In cases such as India, the push for Global Mental Health could potentially offer a remedy to some of the damage already inflicted by “medical imperialism” if focused on aiding the development of public networks that provide community-based care, even if it cannot reverse the “epistemicide” begun under classical imperialism.43

1. Derek Summerfield, “How scientifically valid is the knowledge base for global mental health?” British Medical Journal 336 no. 7651 (2008): 992-994, at 992; China Mills, “Decolonizing Global Mental Health,” in Decolonizing Global Mental Health: The Psychiatrization of the Majority World (Taylor and Francis Group, 2014), 122-23.

2. Mills, “Decolonizing Global Mental Health,” 123, 128-29.

3. Mills, “Decolonizing Global Mental Health,” 129; Summerfield, “How scientifically valid is the knowledge base for global mental health?” 993.

4. Sanjeev Jain, Alok Sarin, Nadja van Ginneken, Pratima Murthy, Christopher Harding, and Sudipto Chatterjee, “Psychiatry in India: Historical Roots, Development as a Discipline and Contemporary Context,” in Mental Health in Asia and the Pacific, eds. H. Minas and M. Lewis (Springer Science + Business Media: New York, 2017), 54.

5. Jain et al., “Psychiatry in India: Historical Roots,” 41.

6. Saiba Varma, “Disappearing the asylum: Modernizing psychiatry and generating manpower in India,” Transcultural Psychiatry 53 no. 6 (2016): 783-803, at 788.

7. Alex Cohen, “A Brief History of Global Mental Health,” in Global Mental Health: Principles and Practice, eds. Alex Cohen, Harry Minas, Vikram Patel, and Martin J. Prince. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), 7.

8. Cohen, “A Brief History of Global Mental Health,” 8.

9. Pamela Y. Collins, Vikram Patel, Sarah S. Joestl, Dana March, Thomas R. Insel, Abdallah S. Daar, Isabel A. Bordin, E. Jane Costello, Maureen Durkin, Christopher Fairburn, et al., “Grand Challenges in Global Mental Health,” Nature 475 no. 7354 (2011): 27-30; Cohen, “A Brief History of Global Mental Health,” 8.

10. Mills, “Decolonizing Global Mental Health,” 129.

11. James Mills, “Modern psychiatry in India: The British role in establishing an Asian system, 1858 – 1947,” International Review of Psychiatry 18 no. 4 (2016): 333-343, at 333.

12. Idem, 334, 343.

13. Idem, 336.

14. Idem, 343.

15. Idem, 341.

16. Jain et al., “Psychiatry in India: Historical Roots,” 42, 44.

17. Ibid.

18. Mills, “Modern psychiatry in India,” 343; Jain et al., “Psychiatry in India: Historical Roots,” 47, 52; Varma, “Disappearing the asylum,” 787.

19. Varma, “Disappearing the asylum,” 788; Ashutosh Varshney, “India’s Democracy at 70: Growth, Inequality and Nationalism,” Journal of Democracy 28 no. 3 (2017): 41-51, at 44-45.

20. Jain et al., “Psychiatry in India: Historical Roots,” 51, 55.

21. Varma, “Disappearing the asylum,” 784.

22. Mills, “Decolonizing Global Mental Health,” 10.

23. Kah Seng Loh, Ee Heok Kua, and Rathi Mahendran, “Mental Health and Psychiatry in Singapore: From Asylum to Community Care,” in Mental Health in Asia and the Pacific, eds. H. Minas and M. Lewis (Springer Science + Business Media: New York, 2017), 196.

24. Idem, 194.

25. Idem, 199.

26. Idem, 199-200.

27. Idem, 201.

28. Idem, 93.

29. Kitikan Thandaudom, Nattakorn Jampathong, and Pichet Udomratn, “One Hundred Thirty Years of Psychiatric Care in Thailand: Past, Present, and Future,” Taiwanese Journal of Psychiatry 32 no. 1 (2018): 9-27, at 10.

30. Sally Swartz, “The Regulation of British Colonial Lunatic Asylums and The Origins of Colonial Psychiatry, 1860–1864,” History of Psychology 13 no. 2 (2010): 160-77; Mills, “Modern psychiatry in India,” 334.

31. Thandaudom, Jampathong, and Udomratn, “Psychiatric Care in Thailand,” 10-11; Loh, Kua, and Mahendran, “Mental Health and Psychiatry in Singapore,” 196.

32. Thandaudom, Jampathong, and Udomratn, “Psychiatric Care in Thailand,” 10-11.

33. Idem, 10.

34. Idem, 11.

35. Idem, 11.

36. Idem, 12.

37. Tapas Kumar Aich, “Contribution of Indian psychiatry in the development of psychiatry in Nepal,” Indian Journal of Psychiatry 52 no. 7 (2010): 76-79, at 76.

38. Aich, “Contribution of Indian psychiatry in the development of psychiatry in Nepal,” 76.

39. Aich, “Contribution of Indian psychiatry in the development of psychiatry in Nepal,” 76. See also: The World Health Organization Assessment Instrument for Mental Health Systems (WHO-AIMS) Report on Mental Health Systems in Nepal (2006), iv.

40. Nagendra P. Luitel, Mark JD Jordans, Anup Adhikari, Nawaraj Upadhaya, Charlotte Hanlon, Crick Lund, and Ivan H Kompro, “Mental Health care in Nepal: current situation and challenges for development of a district mental health care plan,” Conflict and Health 9 no. 3 (2015): 1-11, at 3.

41. Ibid.

42. Luitel et al., “Mental Health care in Nepal,” 5.

43. Summerfield, “How scientifically valid is the knowledge base for global mental health?” 992; Mills, “Decolonizing Global Mental Health,” 122-23.

The Galileo Affair: An Analysis of Bellarmine’s Letter to Foscarini

Bettina ChanWith the invention of the telescope, the ability to observe celestial motion was vastly expanded. Galileo’s observations of celestial bodies provided an exemplar of the far-reaching impact of this expanded view and its demand for new understandings of the cosmos. In Galileo’s view, many of his observations, including the phases of Venus, demanded that Copernicus’ heliocentric system be taken as physical reality. Galileo’s propositions soon grew well beyond mere intellectual speculation and were perceived as threats to religious authority. In 1611, allegations against Galileo began to arise. He was accused of teaching knowledge that contradicted the prevailing interpretation of Holy Scriptures. In response, Cardinal Roberto Bellarmine, a Jesuit, was made responsible for the investigation of Galileo’s publications. He wrote a letter addressed to another cleric and outspoken supporter of the heliocentric system named Foscarini, to elucidate flaws in the Copernican account and to provide arguments against Galileo’s interpretation of the Copernican system1. This article

provides an analysis of Bellarmine’s distinction between Copernican’s theory as a mathematical model and as a description of physical reality. It also discusses how he upheld the authority of the church through rational argumentation while attempting to preserve Galileo’s theories as merely suppositional.

For modern readers, Bellarmine, views might be understood in terms of instrumentalism. Instrumentalism, proposed by Dewey and Popper in the 20th century, is a school of thought that understands scientific theories as useful and suppositional tools, rather than absolutely true descriptions of reality. 2 Instrumentalists hold that theories are only useful in explaining and predicting phenomena3. Similarly, Bellarmine contended that Copernican theories were merely mathematical hypotheses. In the letter, Bellarmine said:

‘For there is no danger in saying that, by assuming the Earth moves and the sun stands still, one saves all of the appearances

better than by postulating eccentrics and epicycles; and that is sufficient for the mathematician. However, it is different to want to affirm that in reality the sun is at the center of the world and only turns on itself, without moving from east to west, and the earth is in the third heaven and revolves with great speed around the sun; this is a very dangerous thing, likely not only to irritate all scholastic philosophers and theologians, but also to harm the Holy Faith by rendering Holy Scripture false.’ 4

He drew clear distinctions between wanting to affirm cosmological reality and wanting to formulate mathematical laws to predict observable phenomena. He made reference to Plato’s notion of ‘saving the phenomena’. This might be sufficient for mathematicians like Copernicus because it is plausible to claim that one theory is better than the other in terms of mathematical prediction. Yet, Bellarmine held that this was still rather different from describing reality since one shall have the authority of the Holy Scriptures in mind while considering it. Any case where scriptures were contradicted becomes very dangerous because they were divine and were considered to be infallible but open to fallible interpretation.

Bellarmine adopted an approach such

that cosmological theories should be aligned with Holy Scriptures. The distinction between scriptures and their interpretation is important such that fidelity to the authority of the Church can be maintained. He said:

‘The Council prohibits interpreting Scripture against the common consensus of the Holy Fathers…, you will find all agreeing in the literal interpretation that the sun is in the heavens…’ 5

Part of the reason why Bellarmine insisted that reinterpretation would be rejected was the Protestant Reformation, which had destabilised the authority of the Roman Catholic Church. Reinterpretation of the scripture would harm the Church’s credibility and Bellarmine did not want to exacerbate the challenge to Catholic scriptural authority. To strengthen his point, Bellarmine quoted Solomon, who was wise and inspired by God himself, to support his argument: ‘The sun rises and the sun sets, and hurries back to where it rises.’ 6 It was unreasonable for a man as wise as him to make claims contrary to the truth. Therefore, the church could not tolerate interpretation contrary to the Holy Fathers and commentators because it would be heretical.

Furthermore, to consolidate the

church’s authority with regards to true demonstrations and reason, Bellarmine said:

‘If there were a true demonstration…, then one would have to proceed with great care in explaining the Scriptures that appear contrary, and say rather that we do not understand them than that what is demonstrated is false.’ 7

Bellarmine did not insist that Galileo abandon Copernicanism outright. Instead, he provided an exception to his claim. He said that if true demonstrations were provided, the church would inevitably re-interpret the scriptures. However, he thought that demonstrations were difficult to provide and in such circumstances, one should follow the interpretation of the Holy Fathers.8 By doing so, Bellarmine was trying to defend reason. As Augustine had it, ‘in [reason] we are made unto the image of God.’

9 He emphasized that the Scriptures were divine, yet their interpretation was human. Thus if reason points towards a reinterpretation, the church would reinterpret the relevant verses to align with new claims.10 Not only did he defend human reason; he also defended the church’s privilege to represent it. Bellarmine, as a church official, set out the requirements for the demonstration himself and

the standards by which it would be satisfied.11 This reasserted the authority of the Catholic Church as the institution able to adjudicate contradictions between scriptural interpretation and philosophical propositions instead of natural philosophers or astronomers like Galileo.

In conclusion, this article has demonstrated Bellarmine’s instrumentalist approach by drawing a distinction between utilising Copernican theories in a mathematical model and them being truly descriptive of reality. The Protestant Reformation played an important role in his approach because it was crucial at this time to uphold the authority of the Catholic Church. Lastly, the article explained why Bellarmine did not reject Galileo immediately by referring to the importance of reasoning to the Church authorities.

1. Ofer Gal, The Birth of Modern Science: Chapter 3. The University of Sydney, 2018.

2. Ibid.

3. Anjan Chakravartty, “Scientific Realism,” in Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2017 Edition), ed. Edward N. Zalta. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/scientific-realism/ (Retrieved 8 January 2019).

4. Maurice A Finocchiaro, ed., The Galileo Affair: A Documentary History (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1989) .

5. Ibid.

6. Ecclesiastes 1:5 (NIV).

7. Maurice A Finocchiaro, ed., The Galileo Affair: A Documentary History (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1989).

8. Ibid.

9. Ofer Gal, The Birth of Modern Science: Chapter 7. The University of Sydney, 2018.

10. Maurice A Finocchiaro, ed., The Galileo Affair: A Documentary History (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1989).

11. Ibid

The Raven’s Paradox: Does Context Determine the Relevance of Evidence?