Welcome to the Spring 2025 issue of The Slow Camera Exchange. This issue is focused on the theme of archives with Dutch guest writer and historian Adwin de Kluyver contributing some of his work exploring archives and co editing this edition to bring together threads of exploration.

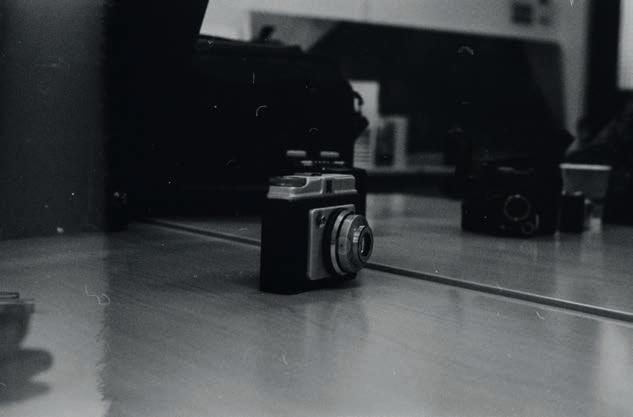

The Slow Camera Exchange (SCE) began by setting up an exchange of cameras from the Cork City Library in 2022. The cameras belonged to Hermann Marbe who passed away in 2018 and the project was initiated by Jess Marbe. Hermann and Jess were not only partners in life, but also creative collaborators, with a fascination in creative expression that usually goes unseen and stories that are often unheard. They loved to work in spaces where participation in the arts is broad and accessible. They viewed creative expression as a right for all. It seems fitting for Hermann’s cameras to be made available for public use through The Slow Camera Exchange.

This is a long term initiative that is supported by ongoing inductions introducing people to the camera

Cork City Libraries are proud to partner with the Slow Camera Exchange along with Cork Film Centre and Creative Ireland. The initiative is now firmly embedded in the library service as we became the first analogue camera lending library in Ireland and possibly Europe. Our camera library consists of over 60 cameras from the Hermann Marbe collection with some being over 100 years old. By lending these cameras to artists and creatives we are proud to continue Hermann’s vision of making the arts and creativity accessible to everyone through creative community engagements.

If you are new to analogue photography you are invited to sign up to the newsletter on the Slow Camera Exchange website and look out for a workshop opportunity hosted in one of the Cork City Libraries as an introduction.

To borrow the cameras as an individual artist you need to be a member of

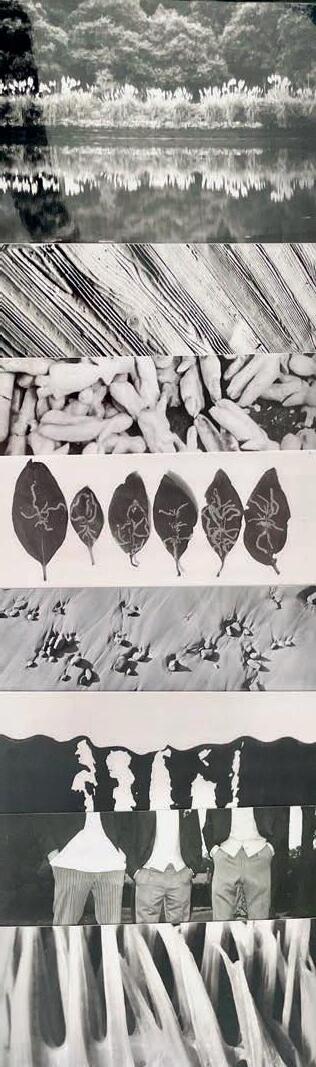

library and also supported by a range of community engagements with the use of the camera kits. Hermann’s eclectic collection of cameras was amassed from trips around the world, to South America, USA, Japan and Europe, where he visited photographic fairs, flea markets and photography shops - some large dealers, others, small businesses with very rare and unusual finds. As well as collecting cameras he gathered lenses and many different optical items and worked within a wide variety of photographic formats and processes. He loved to explore the potential of all types of lenses; from high-end Zeiss systems, to ones used for print reproduction or helicopter surveillance. He was intrigued even by the chance of achieving spectacular images from cheap plastic lenses. He could often be found building, repairing and adapting equipment to help achieve his artistic vision or just to see what unexpected results would emerge. For Hermann, the darkroom was a space of quiet exploration and discovery as images revealed themselves. He worked with standard and experimental film darkroom processes; working with infrared, wet plate, albumen, bromoils, cyanotype, lith prints and emulsions on all sorts of surfaces, from wood to marble. Hermann spent many evening hours in the darkroom crafting the images from negative to a range of surfaces and seeing the carefully planned or the unexpected magic as images emerged in the developing tray.

Jess Marbe

Cork City Libraries and also become a member of the Slow Camera Exchange Club by meeting the guiding criteria for each of the categories and participating In an induction session. This helps to ensure the correct handling and use of the camera collection. Anyone with an interest and some experience in photography is welcome to register for the induction sessions and become a SCE Club member. We also have a library of camera kits that are available for artists and teachers with some experience to borrow to use with groups and this is an important aspect of the project in terms of making the cameras accessible to those with less experience.

Patricia Looney Senior Executive Librarian Cork City Library

As one could imagine with such an interesting collection of cameras Hermann also created an incredible collection of images. The next chapter of The Slow Camera Exchange is to unpack the world of the images Hermann created. This will involve working with images printed in the darkroom and images exposed on 160 undeveloped films. Hermann Marbe work is playful and often captured the essences of relationship between him and his subjects, whether people, objects or environments. He was open, curious and had a sharp eye for details others may miss. He had a special ability to unveil the quirky, magical essence hidden in everyday life. He found humour, joy, irony and beauty in unexpected places in vast quantities. In this new chapter of the Slow Camera Exchange a digital archive will be created including the majority of Hermanns body of work over a period of 18 years.

A partnership has been formed with UCC’s Photo archives, Cork City Libraries and MTU Staff and students across a range of programmes to create the archive and then to bring it to life. MTU through its SATLE funding are supporting this initiative. The idea to have a living archive that supported creativity and learning. It aims to supports creative processes. It also aims to support dialogue processes in learning in fields such as citizenship education, research, coaching, therapy as examples. MTU lecturer Amy Prendergast explains how she feels working with the archive will support the creative processes with her students.

“It’s very important, especially for emerging artists, that they feel a part of a community. Using Herman’s images gifts the artist this understanding and feeling that the human/lived experience is vast- and all is worthwhile and can be valuable. As Rumi said we should ‘welcome’ our ‘joy, depression, meanness… and sorrow.’ Nothing should be rejected or discarded. Using these images as a stimulus also helps to remove or by-pass the paralysing fear of creativity as we are essentially in conversation with another artist who has already begun the dialogue. It is a joy to bring the images to life in all sorts of dialogues”.

Jess Marbe

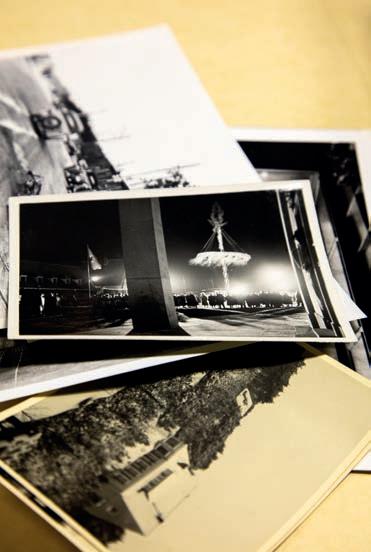

As part of the archiving process the original images have been unboxed and been in a physical sorting process before being catologued and scanned. In the interim there has been space and time to play with the physical printed images.

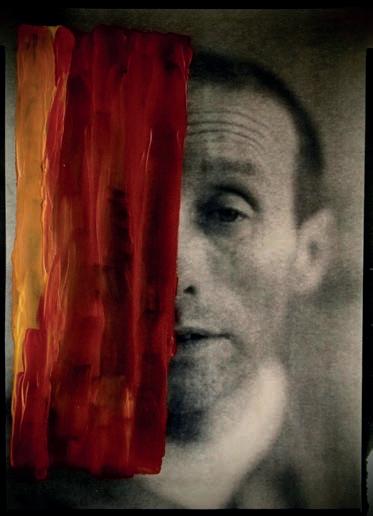

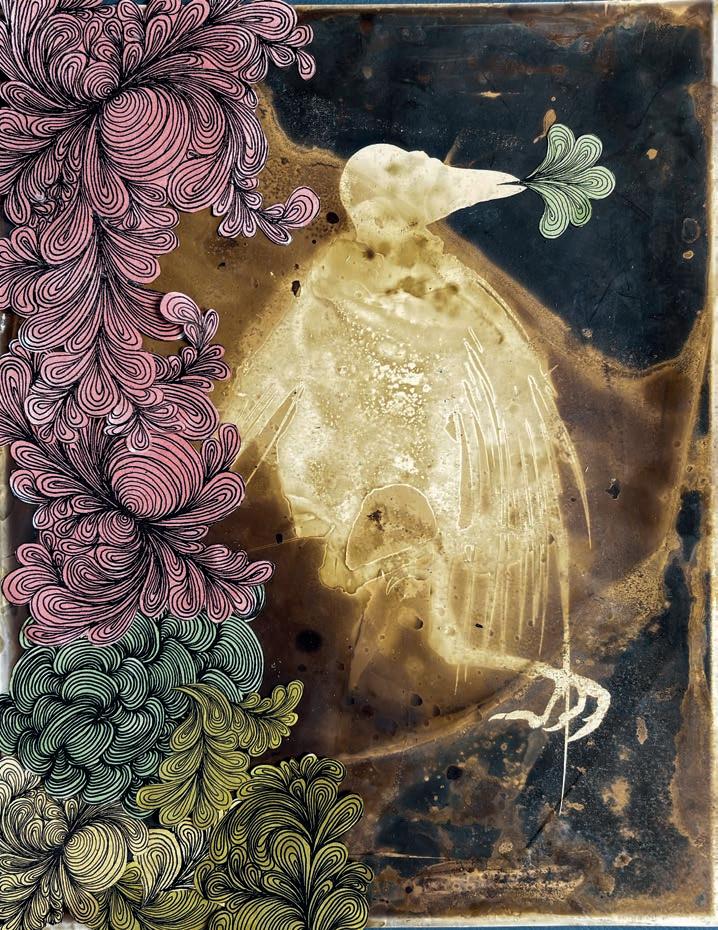

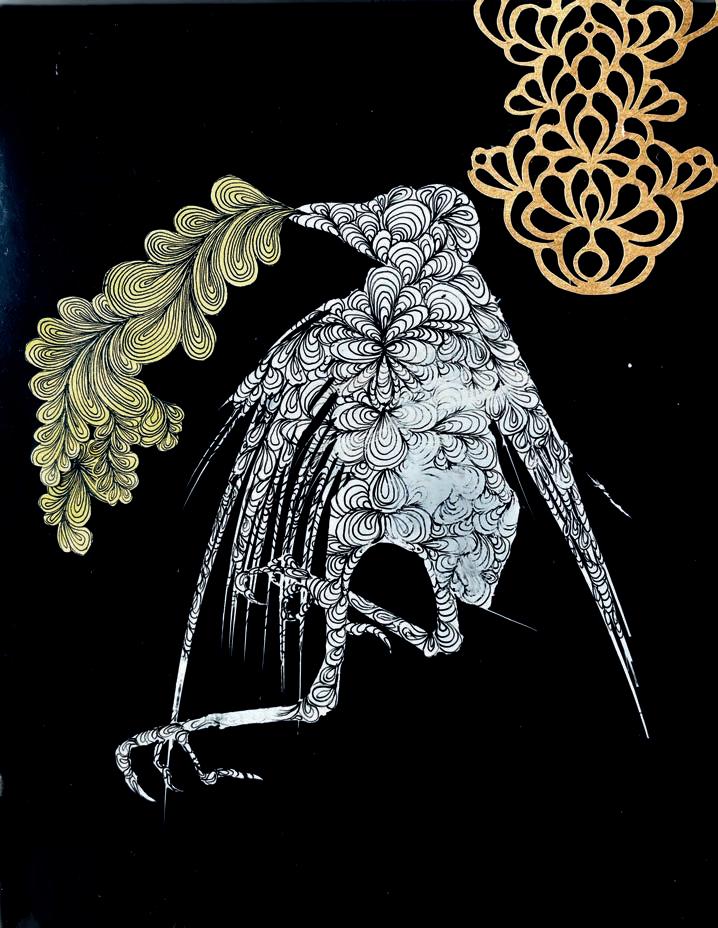

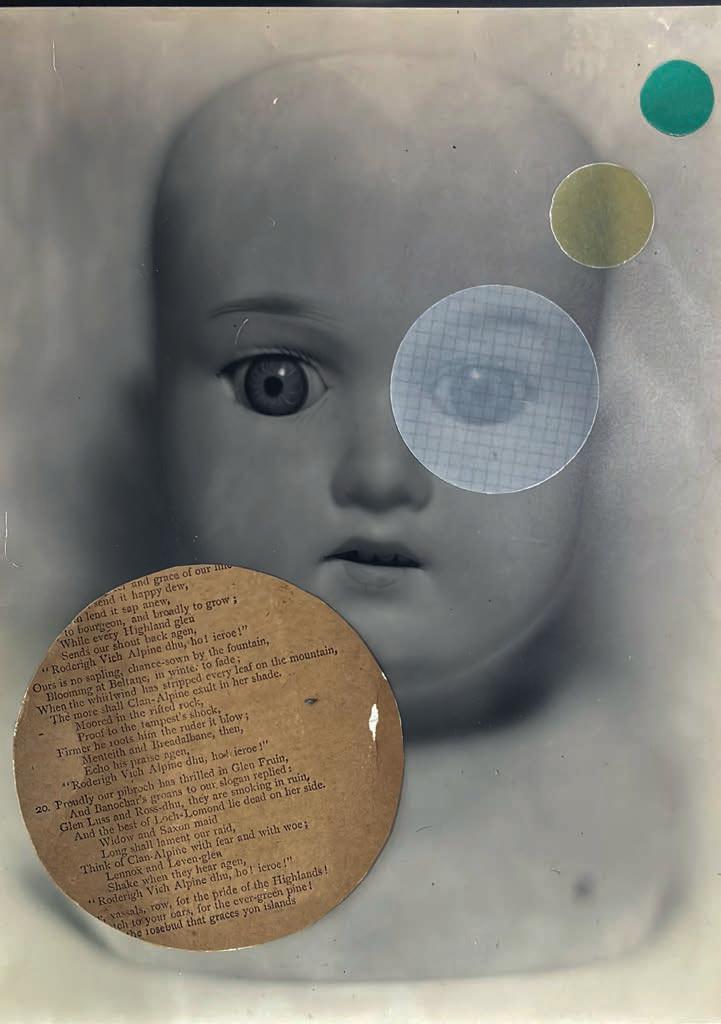

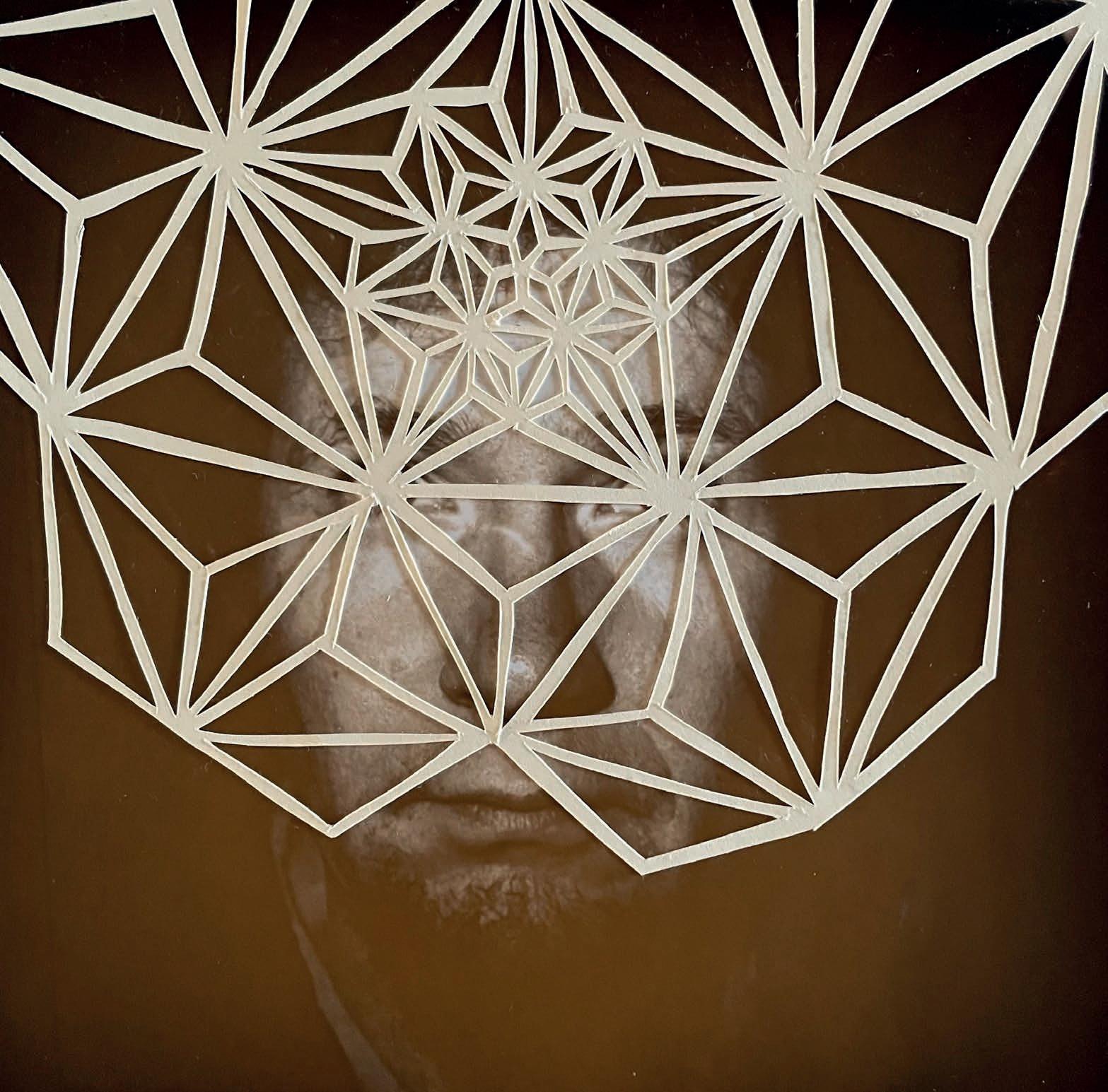

While Hermann Marbe was alive he collaborated on projects with the GASP artists who worked with different drawing and painting processes over images by Hermann. This work was often with the theme of portraiture. This work with the GASP artists continues with their connection to his images in the Crawford Supported Studios based in the campus of Munster Technological University, Crawford College of Art and Design (MTU CCAD)at Grand Parade. During the process the artists choose some original images they would like to collaborate with.

Art therapy Students in MTU CCAD are already starting to work with the images. The images are supporting them to refect and gain insights on their journey with their placements. Other courses that are training artists to work in social and community contacts are facilitating students to make their own toolkits of images to use in their practice. Other course lecturers across several departments are already exploring how the use of the images can support learning and creativity in fields such as outdoor learning, early childhood studies, art teaching, psychotherapy, design thinking, media communications.

These are the first beginnings of creative interactions and experimentation that will help shape how the archive hosting is designed to enable accessibility and useability.

Ahead of the digitisation process of Hermann Marbe’s vast archive, this issue of The Slow Camera Exchange is dedicated to image archives. An archive is not just a repository of materials from the past, it is also a place with a beating heart where present and past, life and death, fact and imagination come together.

In an image archive, we feel the connection with the past. Time and again, we look through the eyes of the photographer and are in a different time and place. A photo archive is a time travel through the imagination of the photographer.

Especially for this issue of The Slow Camera Exchange, Adwin de Kluyver, writer of creative non-fiction and historian, chose a number of angles in which he shows how archive material can inspire new stories, new insights and new works of art.

In his work, the Dutch writer focuses on the thin line between fact and fiction. In the essay ‘Three Stories’, he shows what assumptions the discovery of historical material can generate, and questions whether truth is always preferable to speculation.

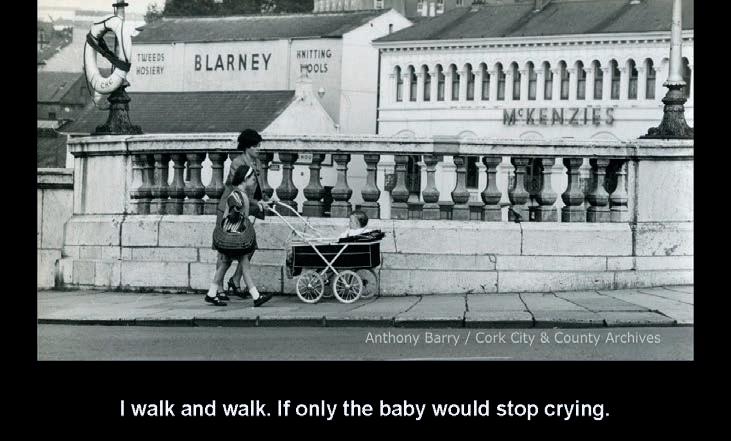

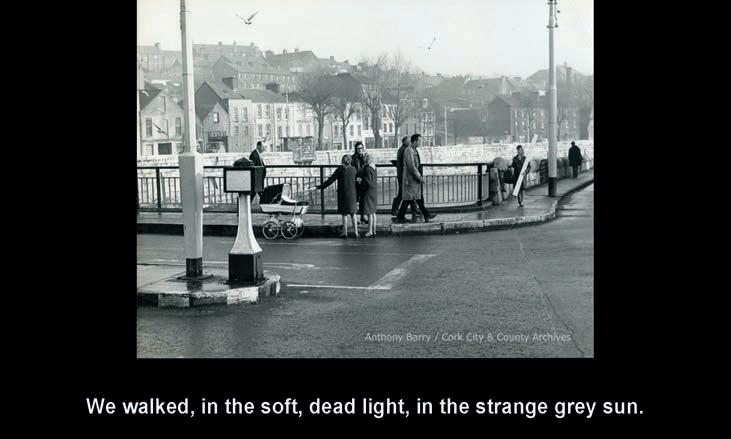

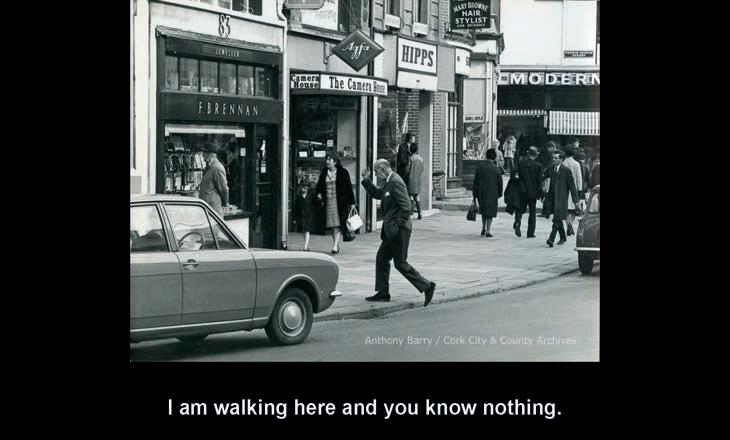

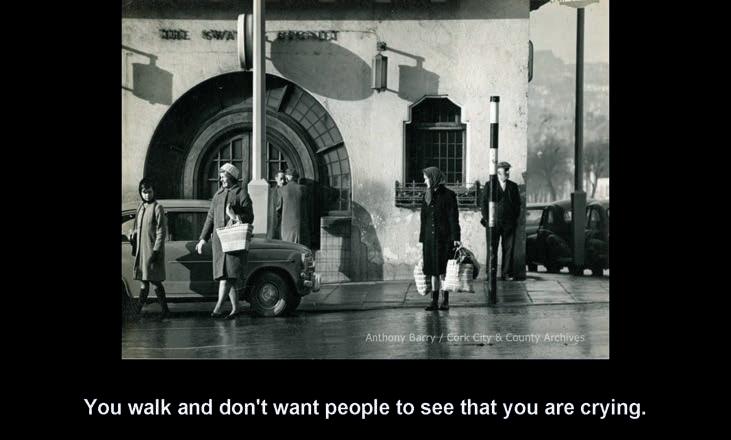

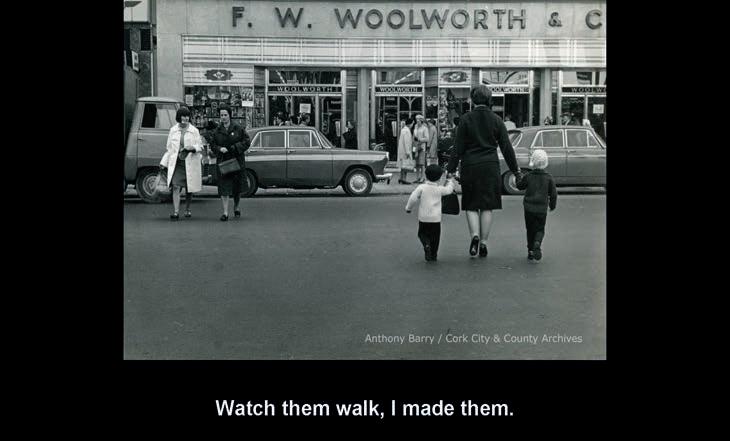

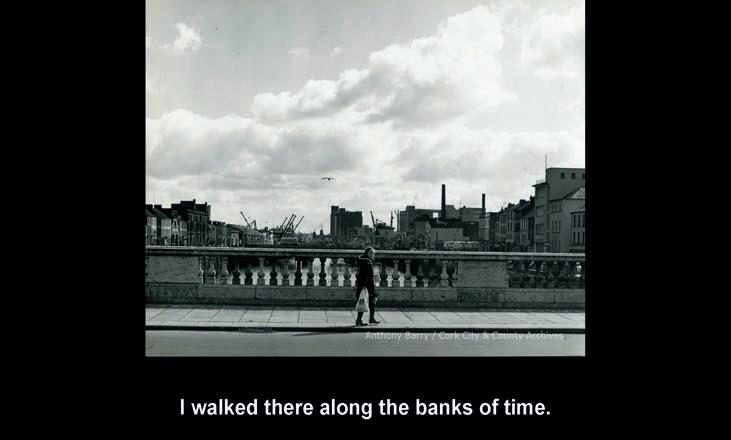

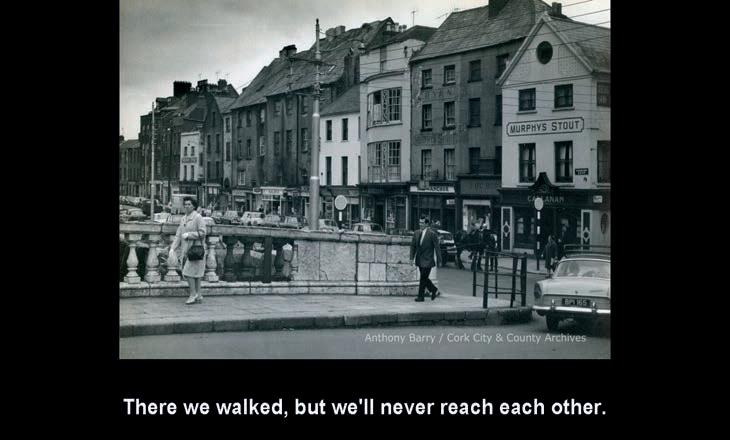

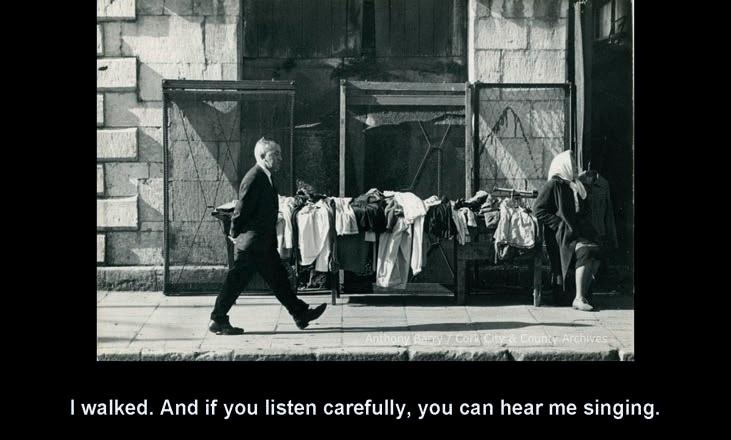

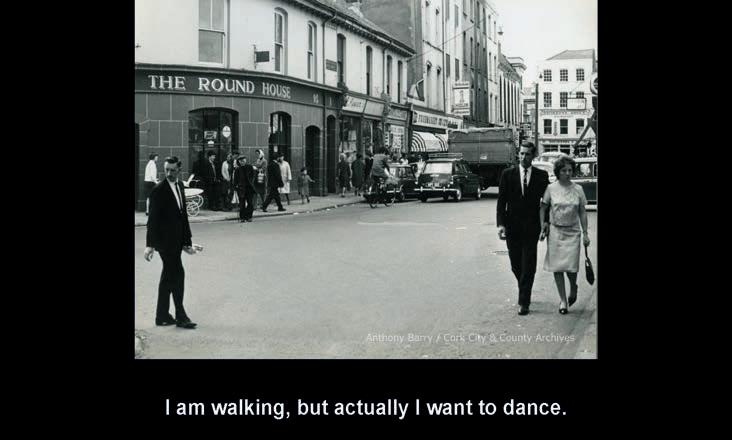

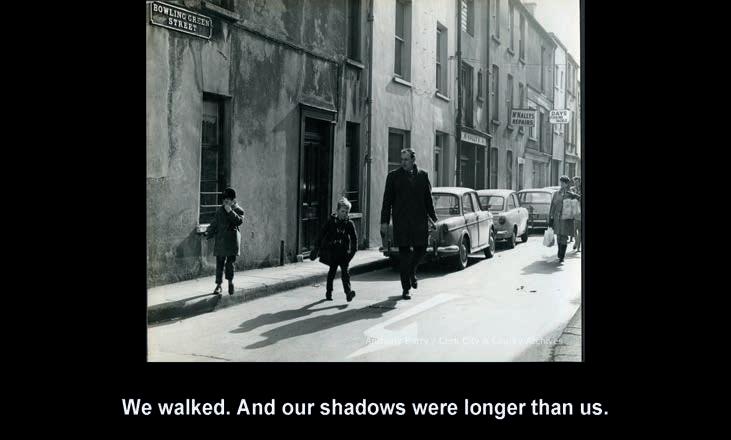

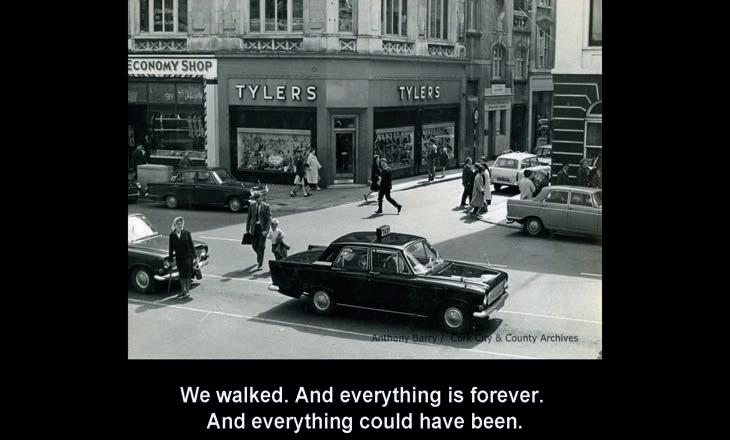

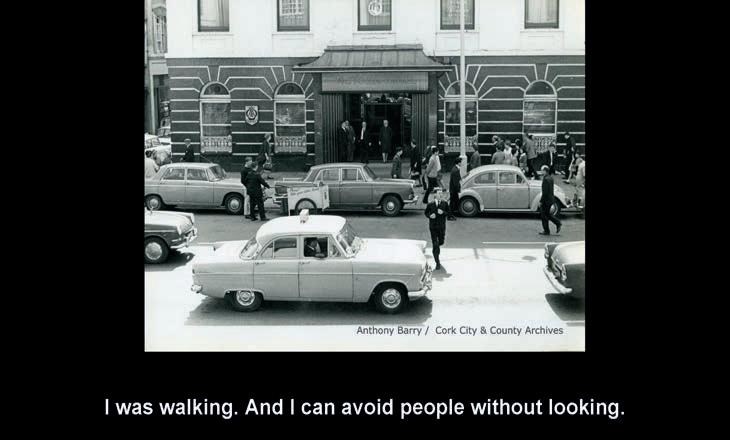

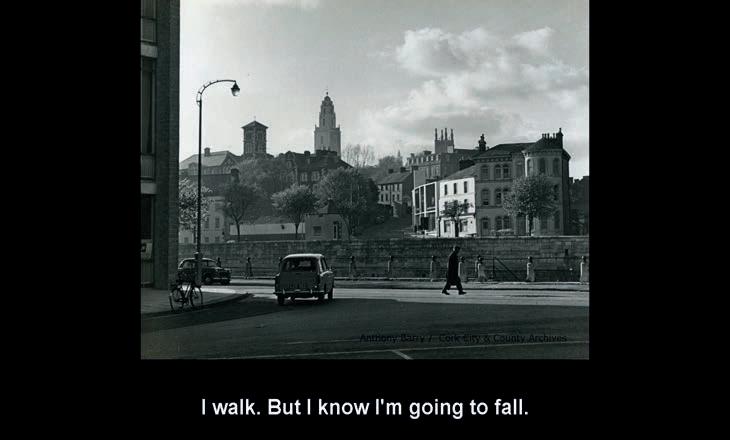

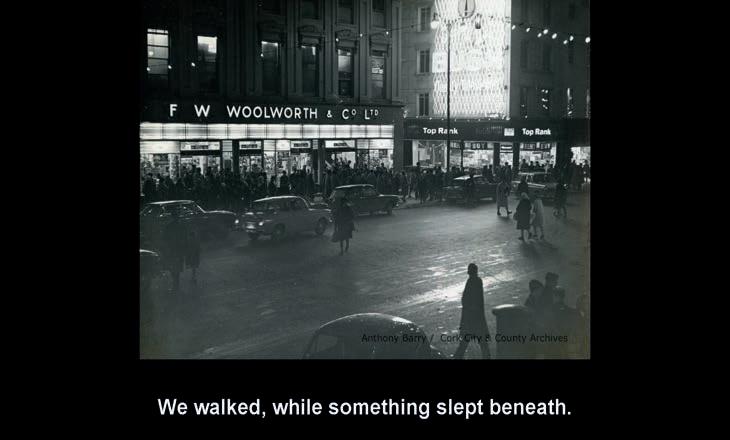

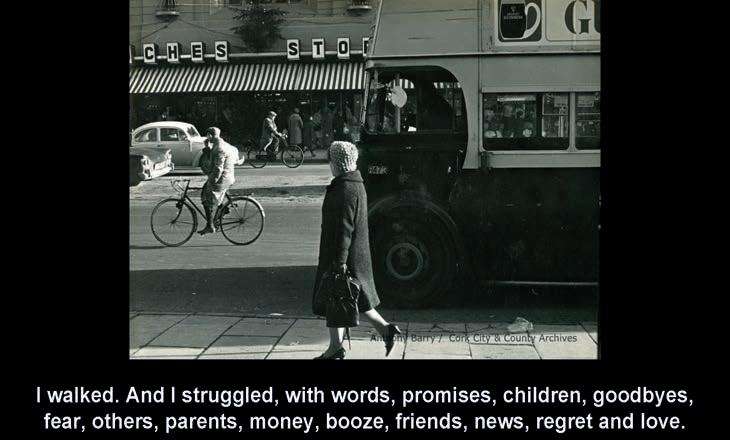

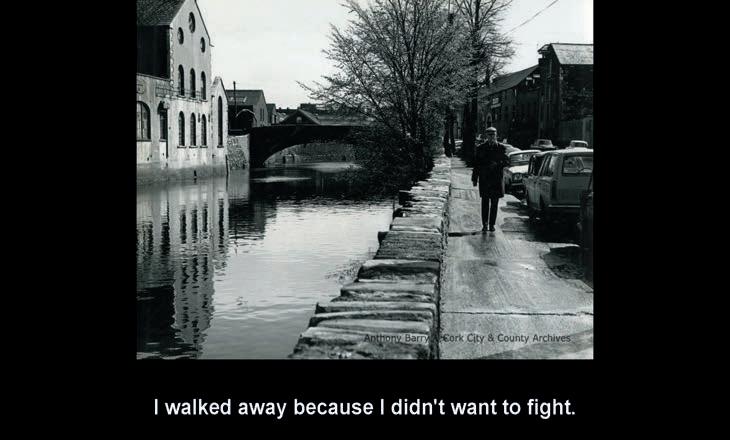

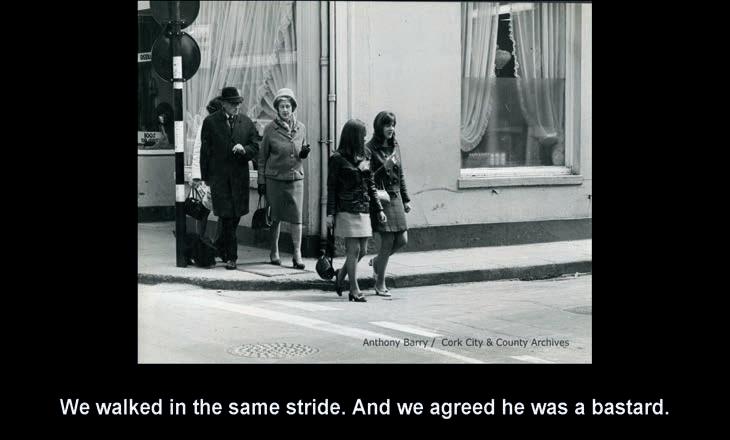

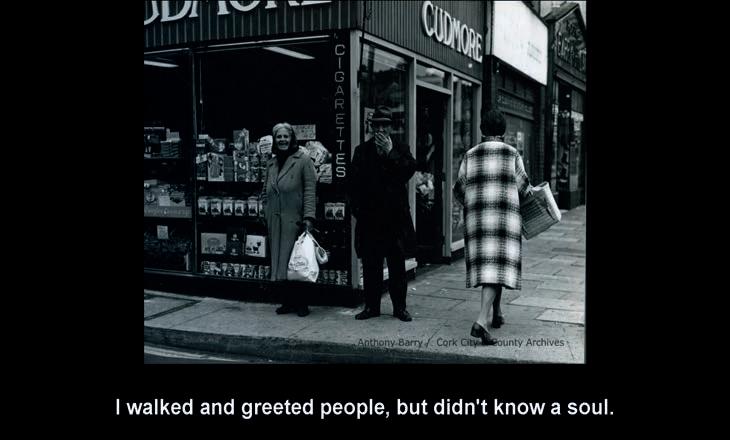

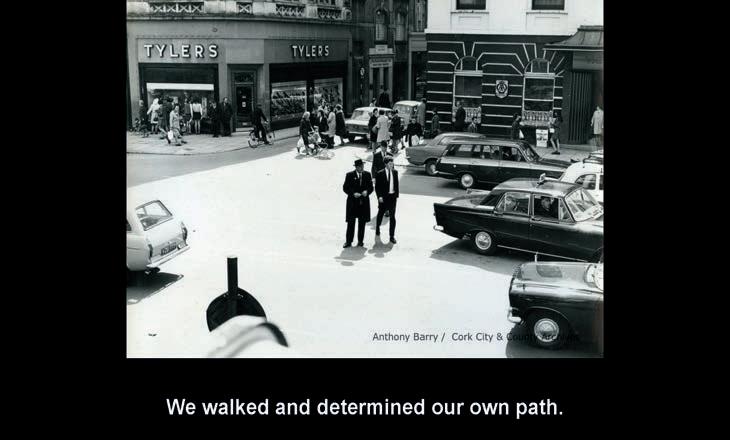

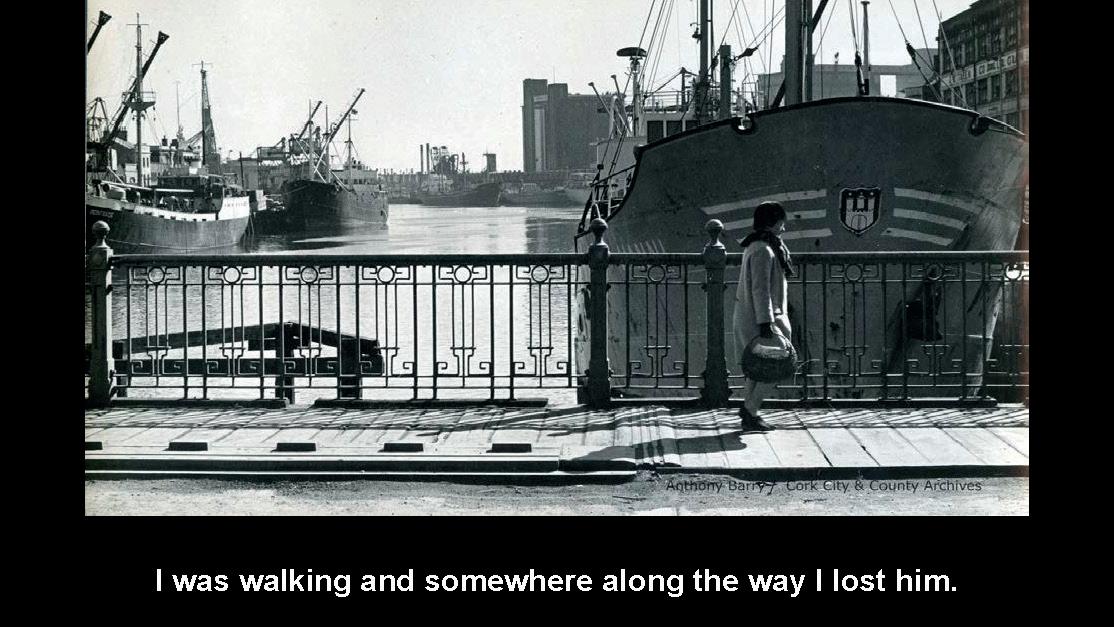

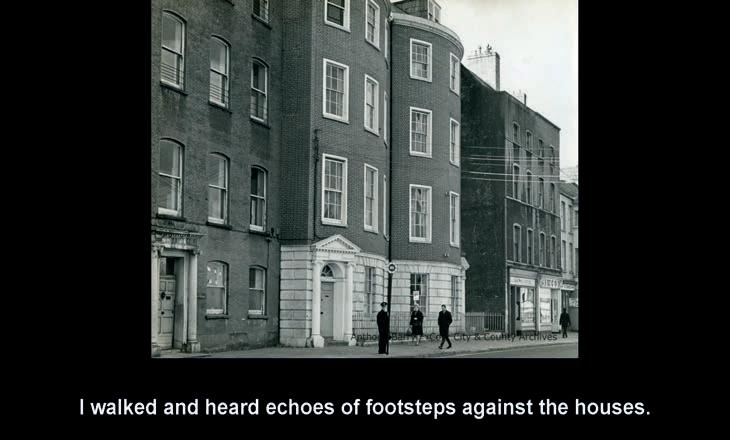

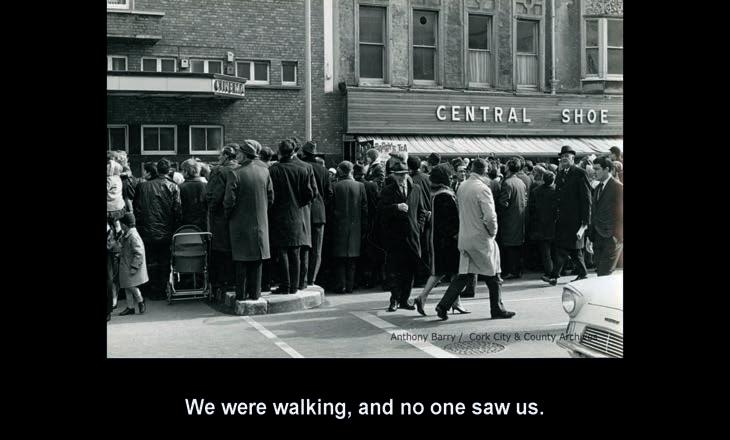

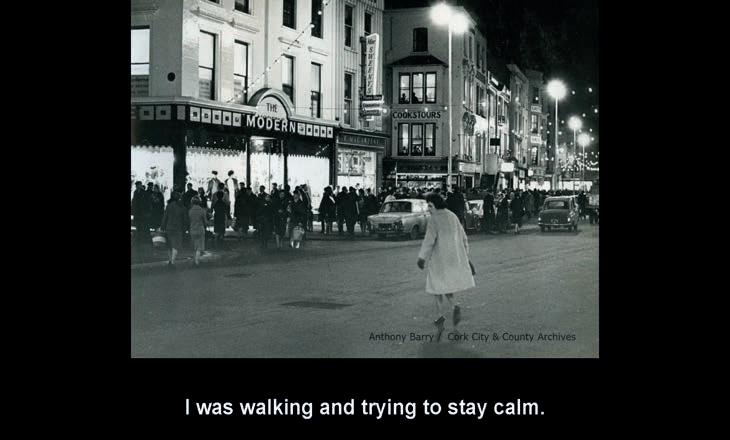

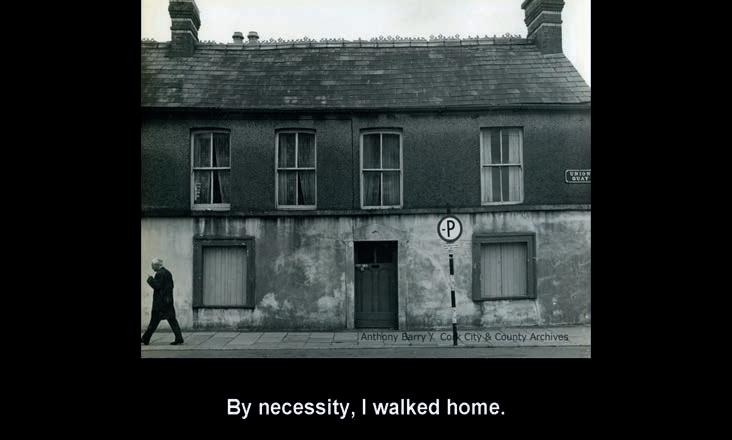

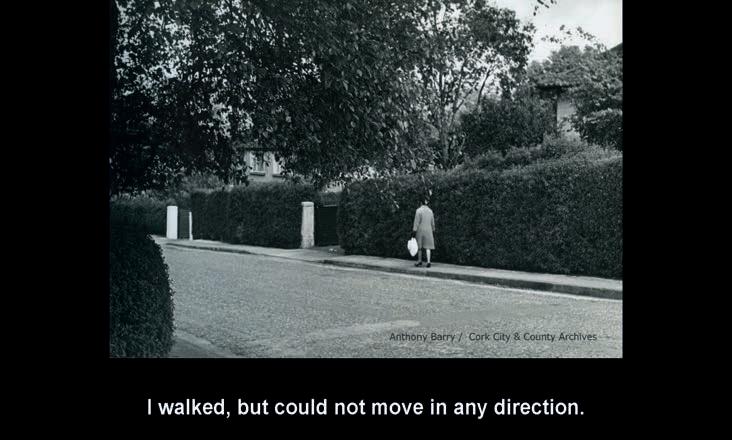

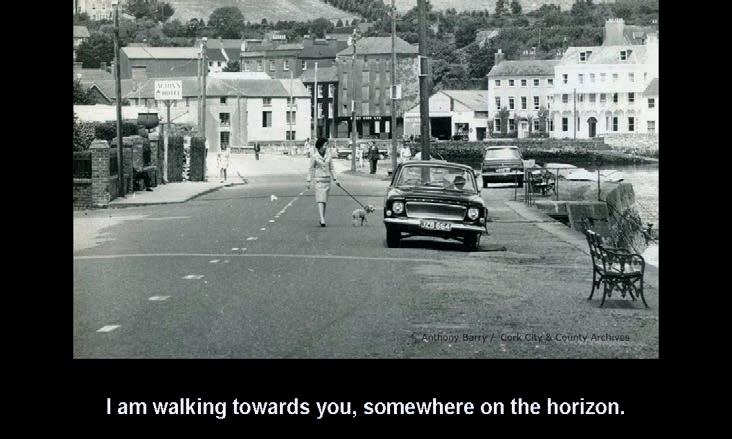

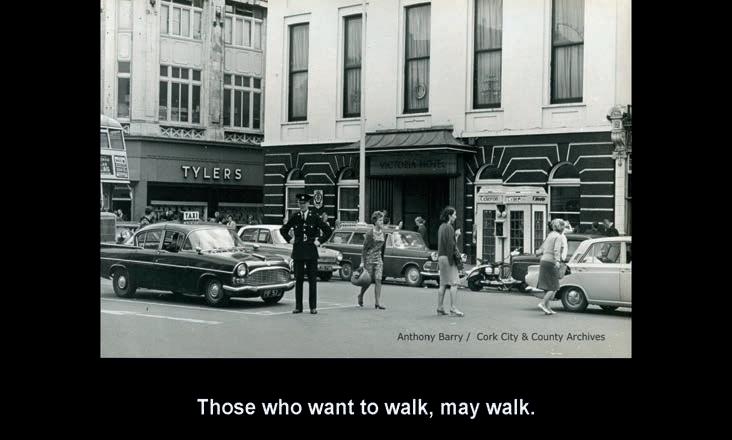

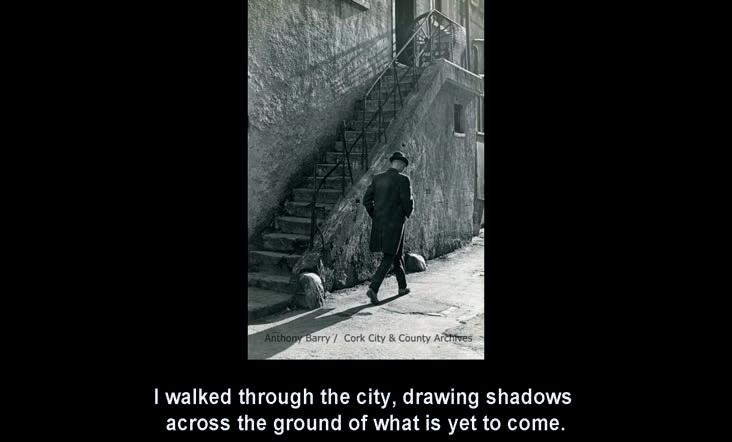

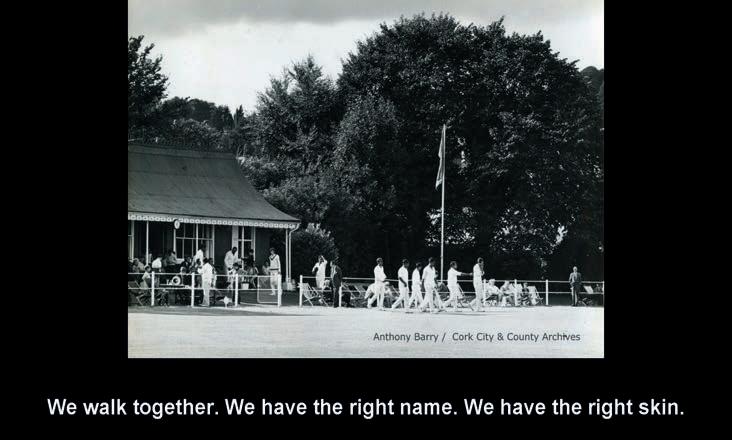

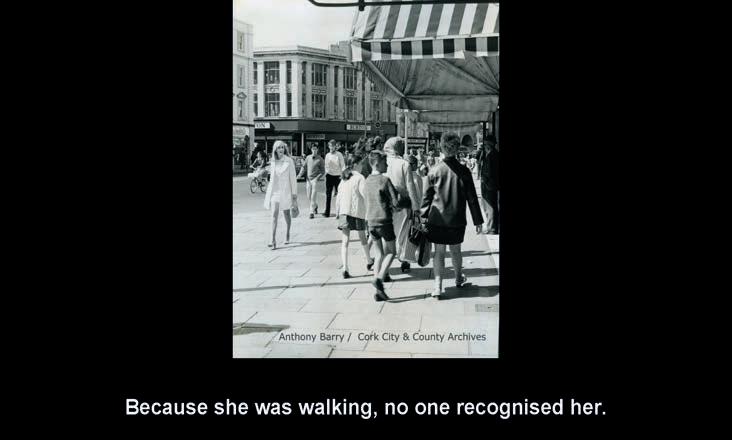

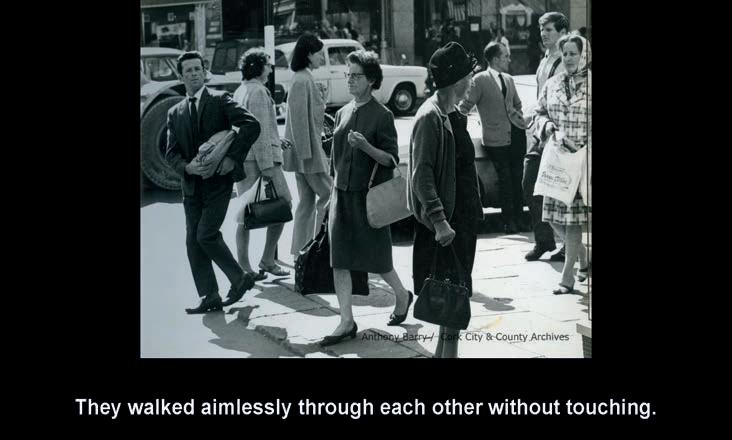

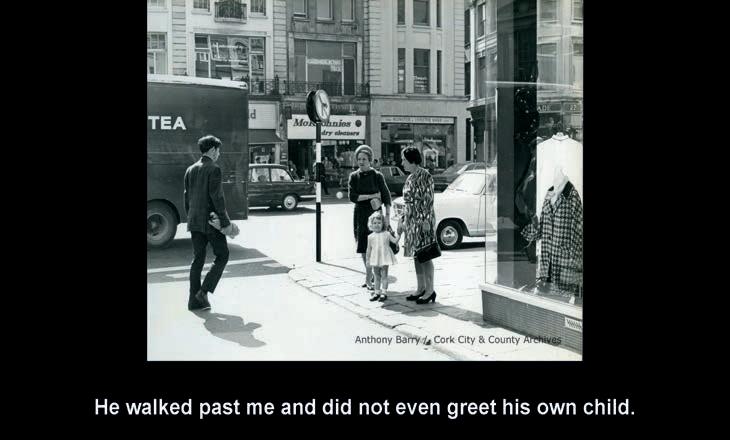

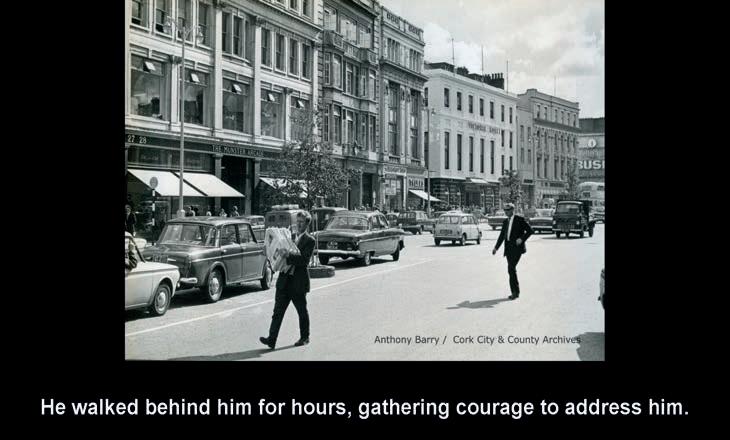

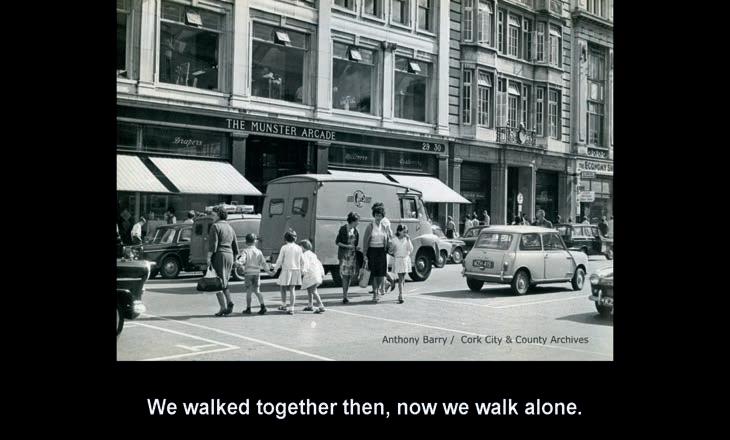

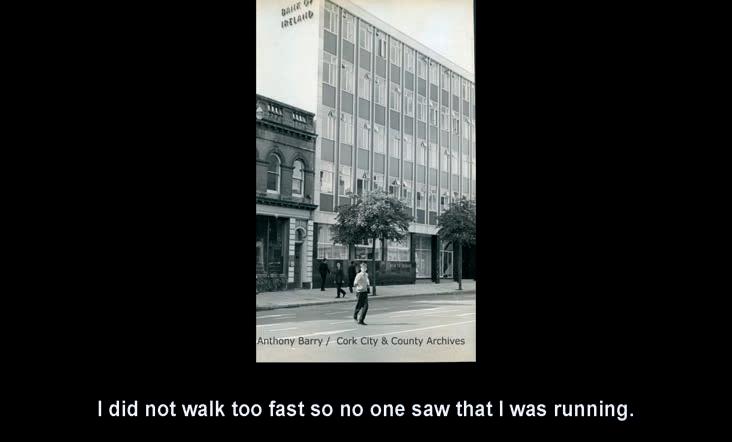

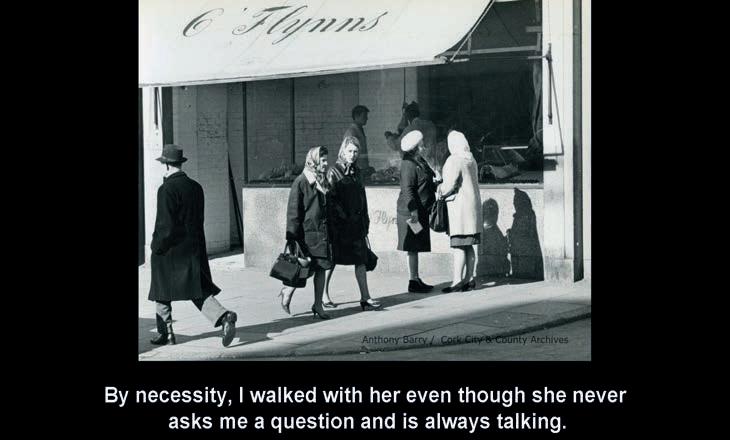

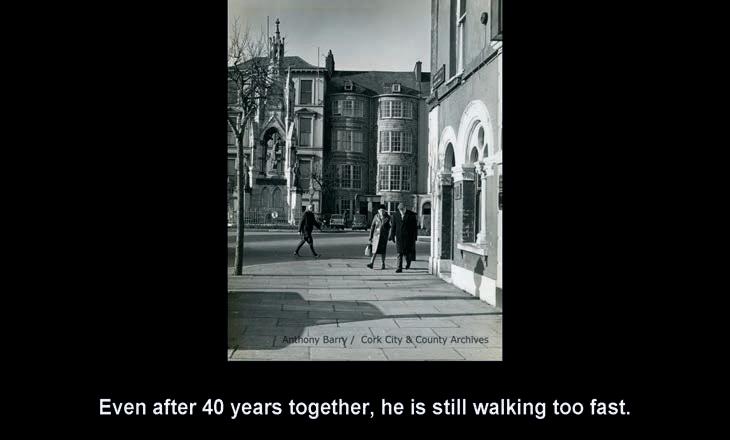

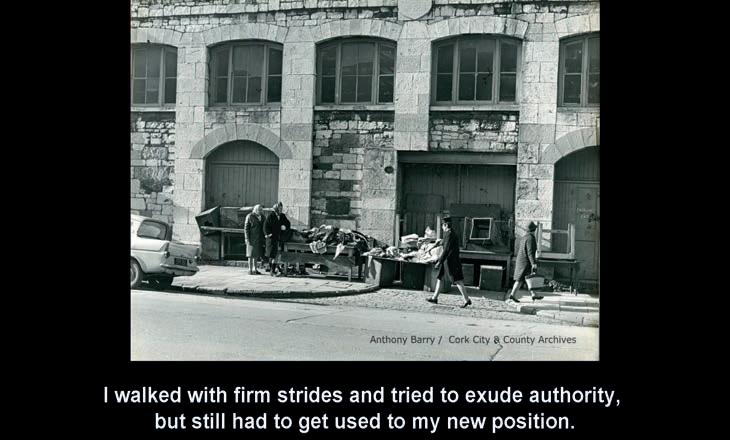

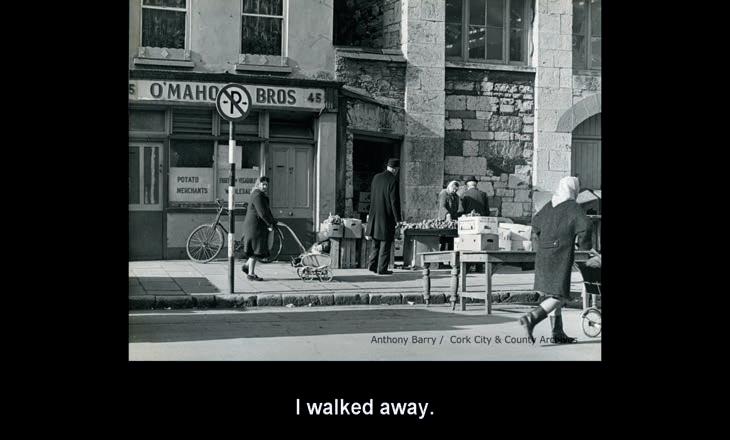

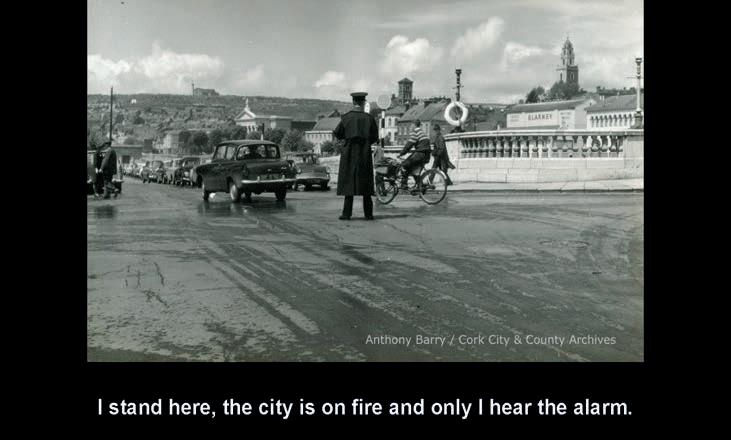

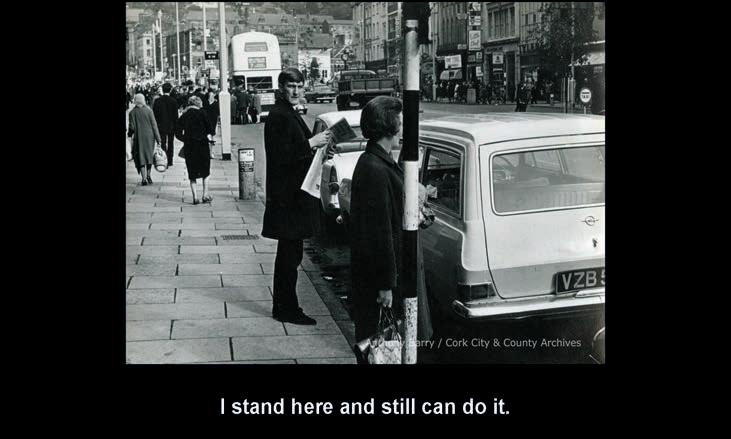

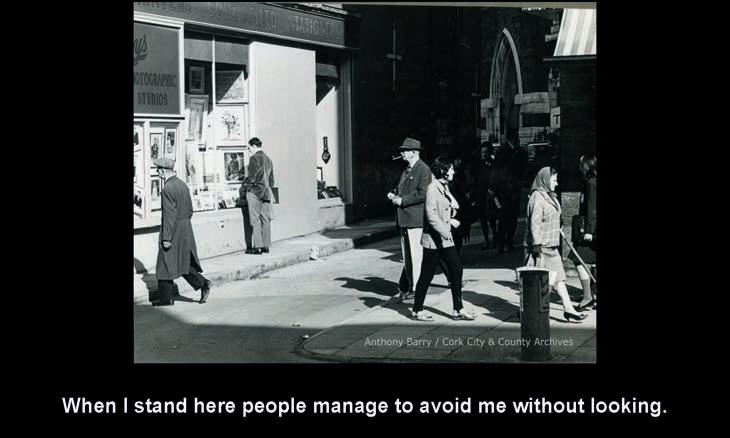

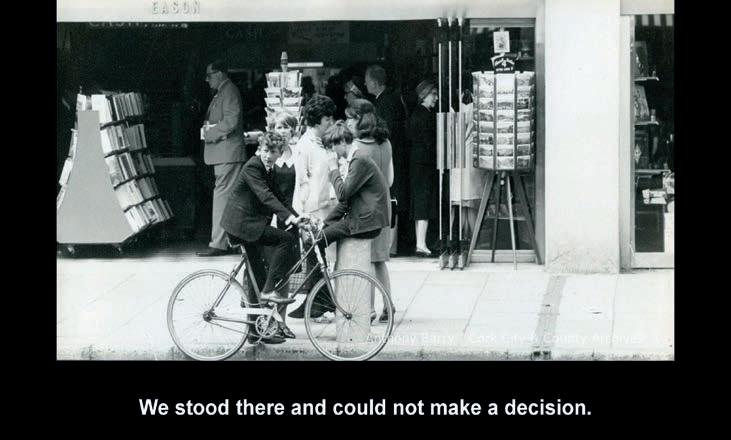

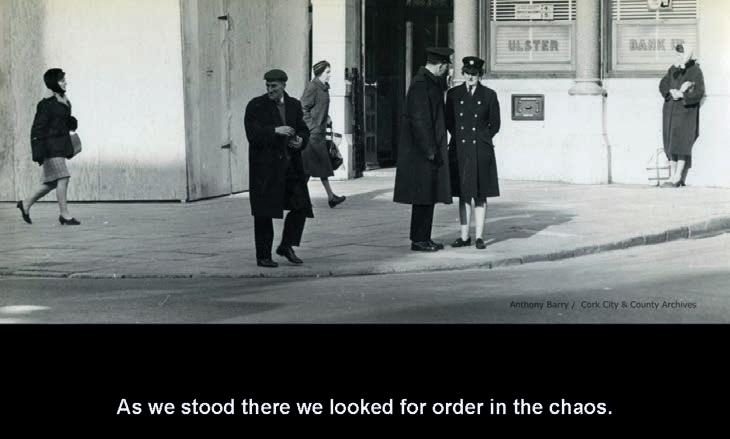

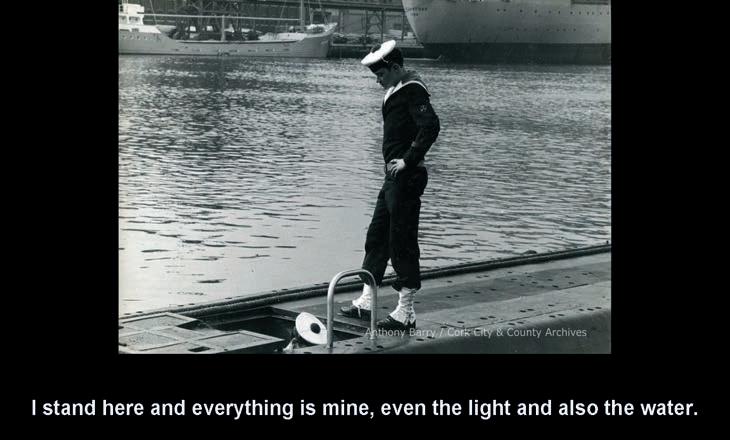

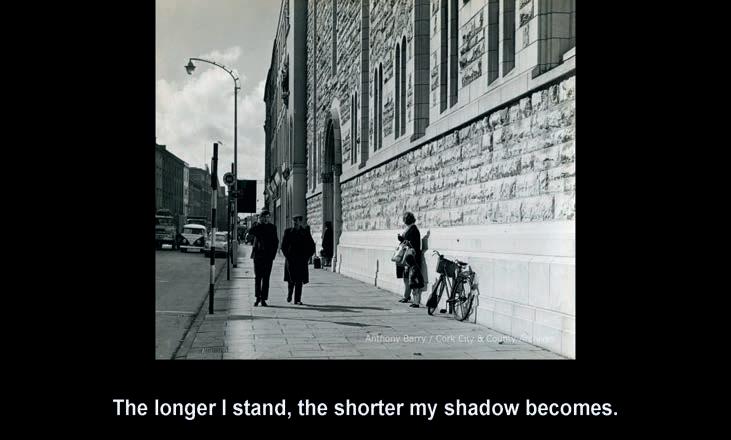

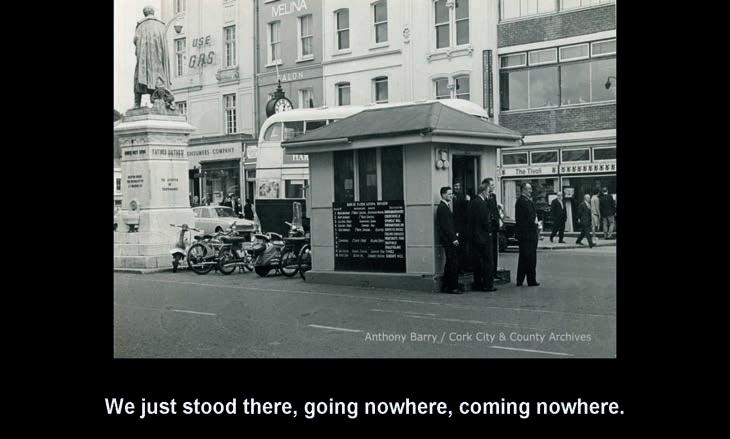

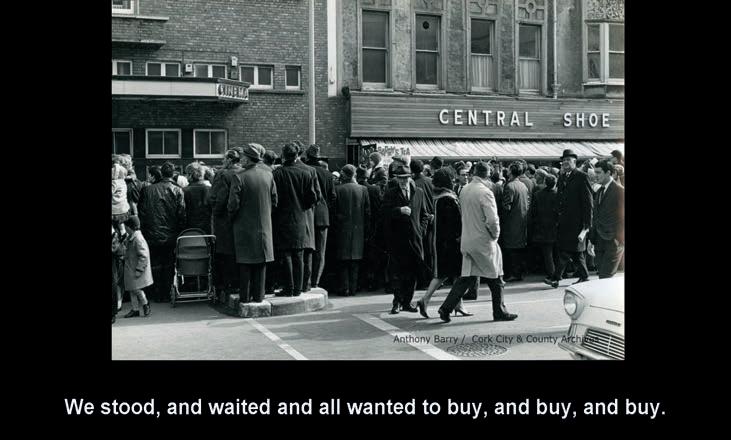

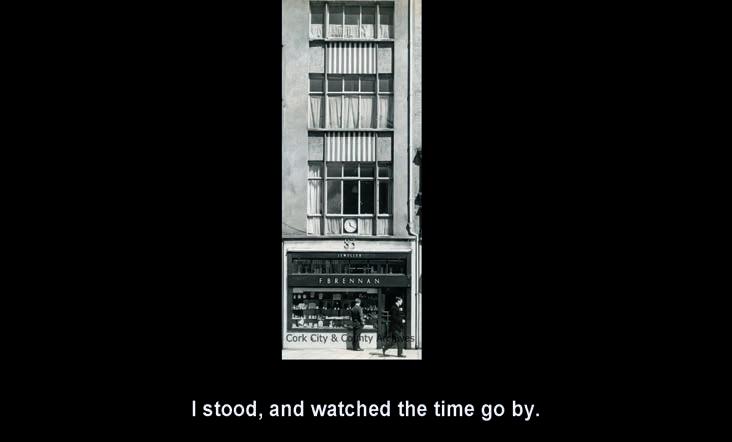

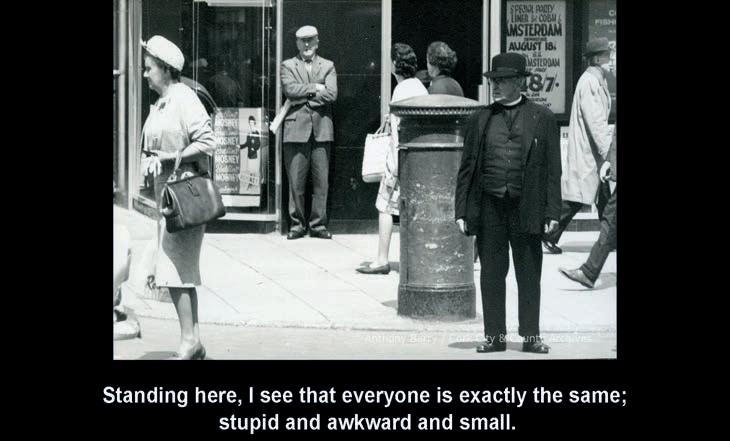

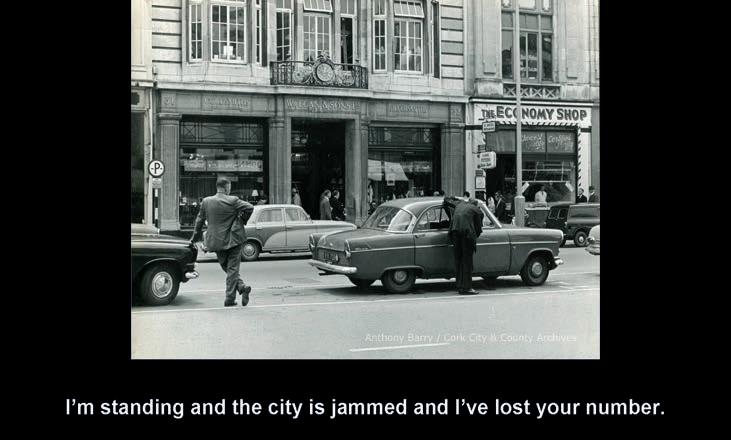

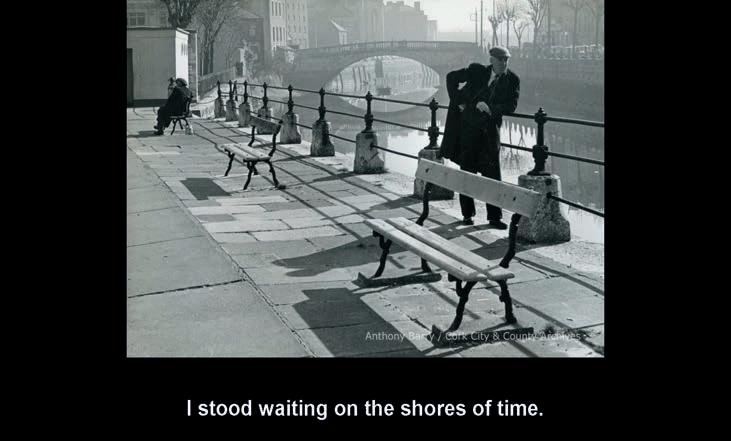

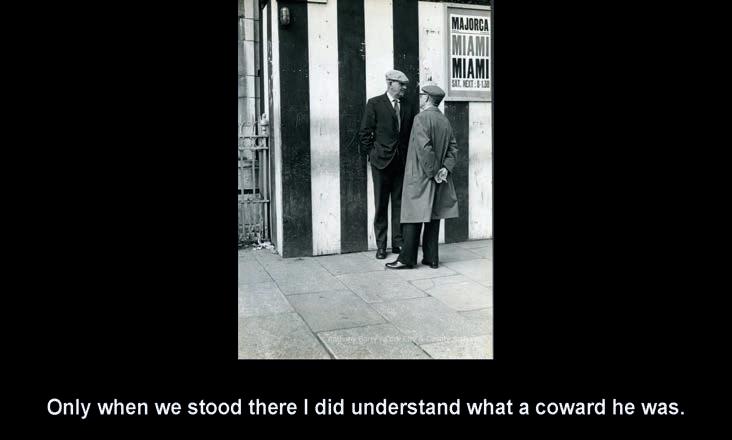

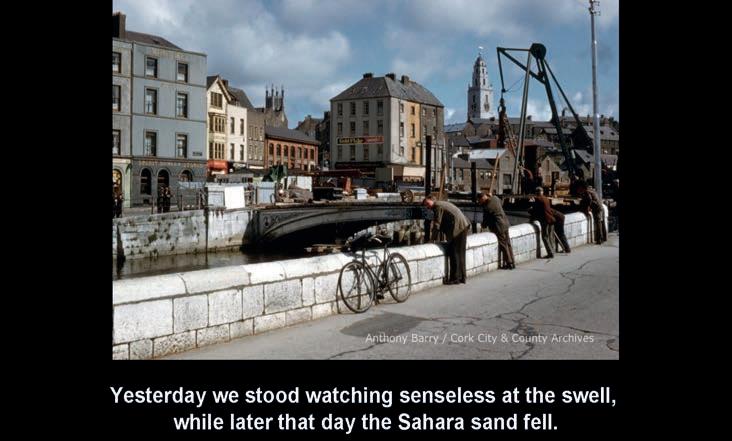

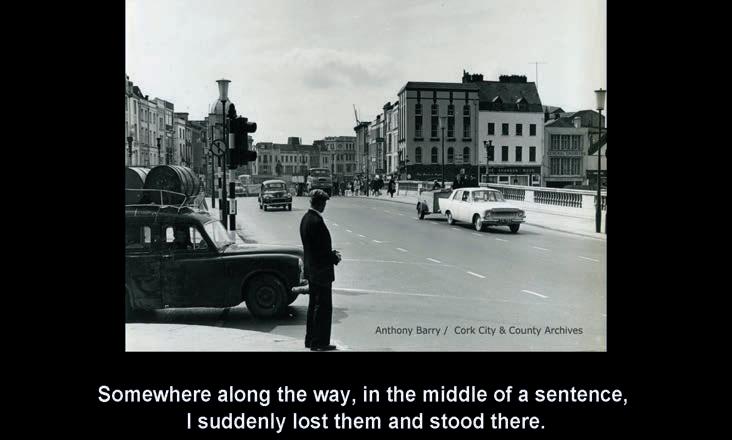

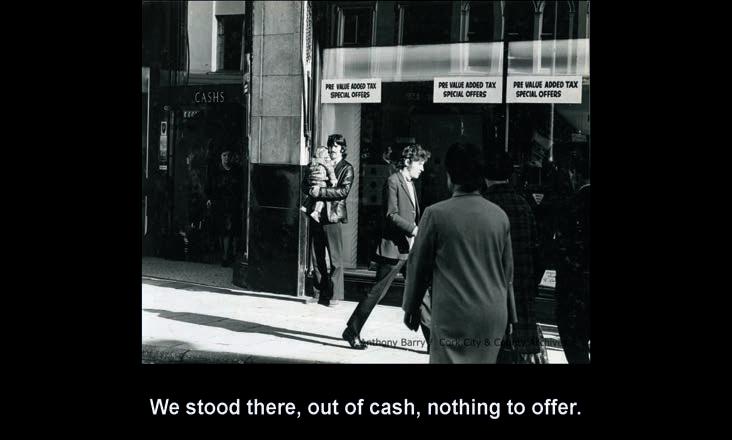

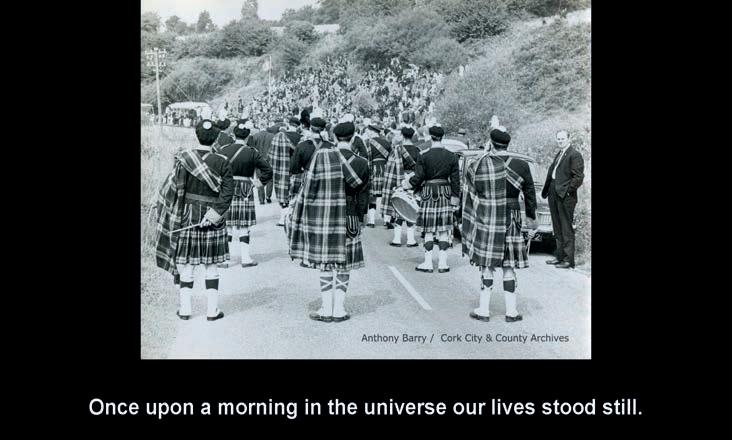

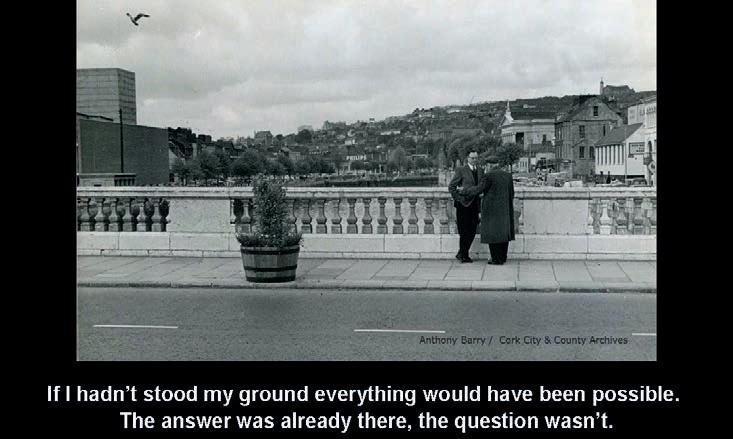

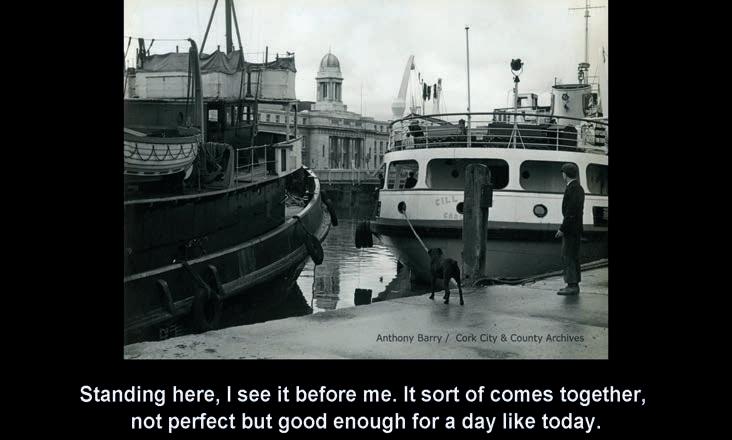

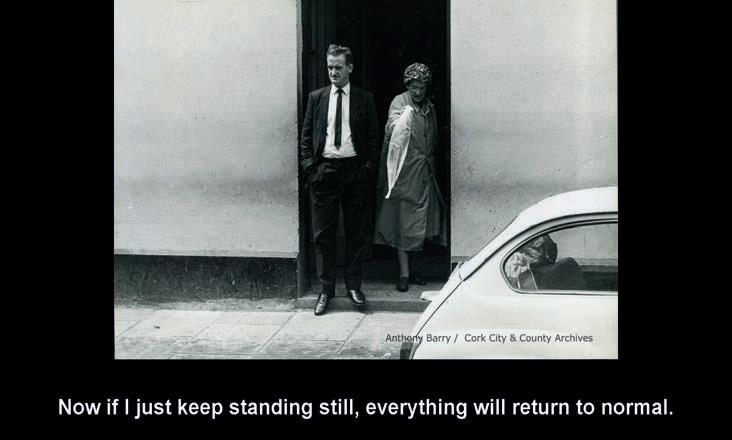

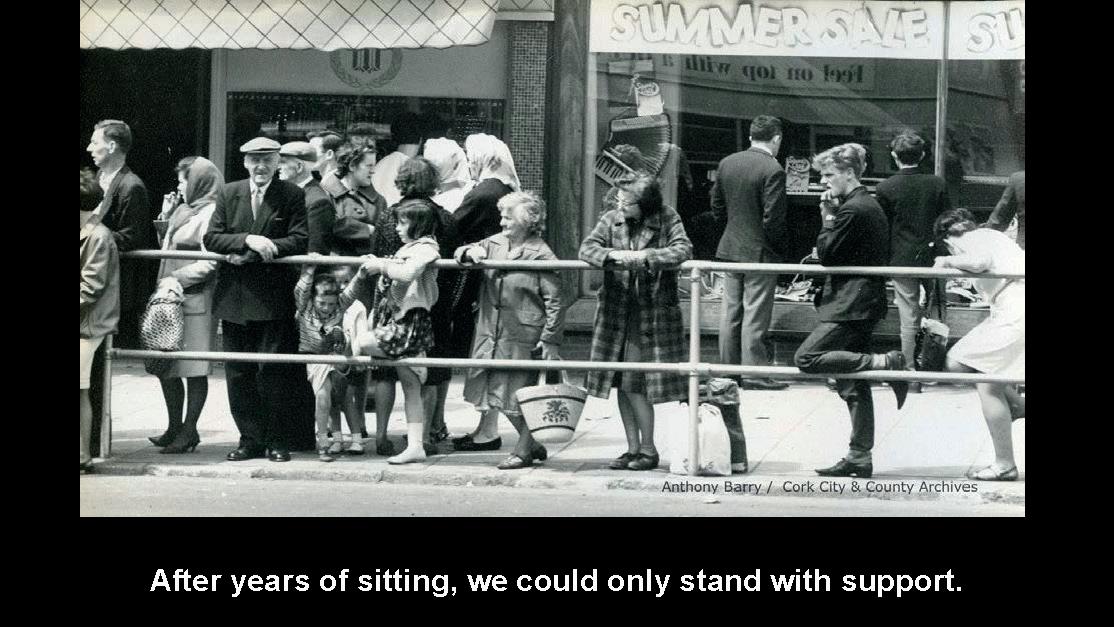

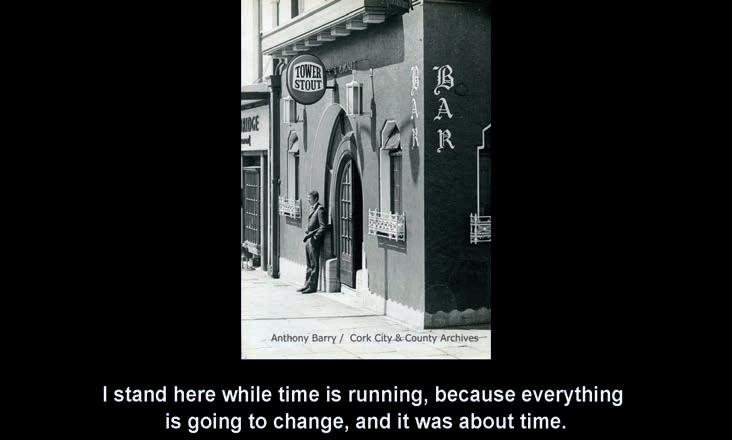

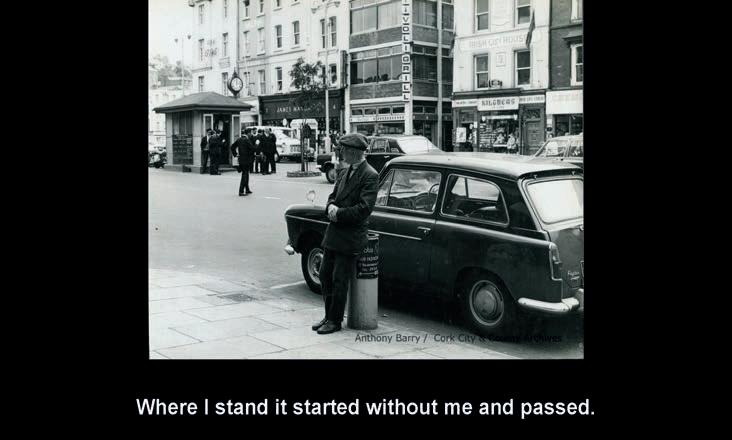

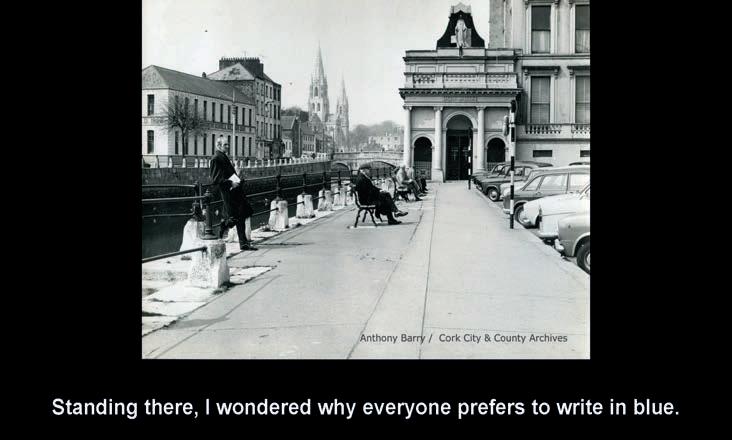

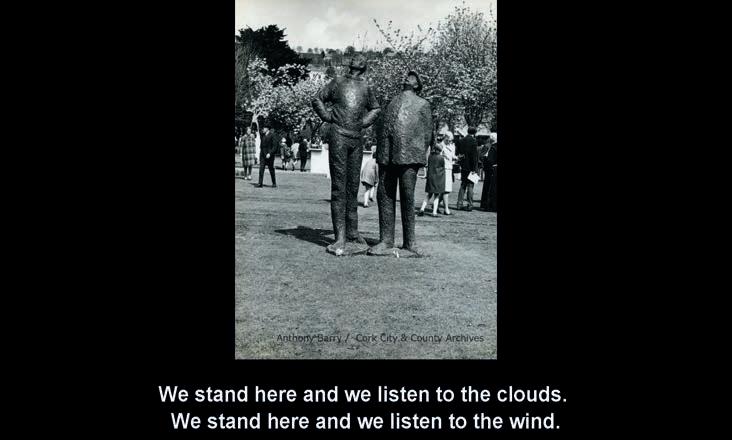

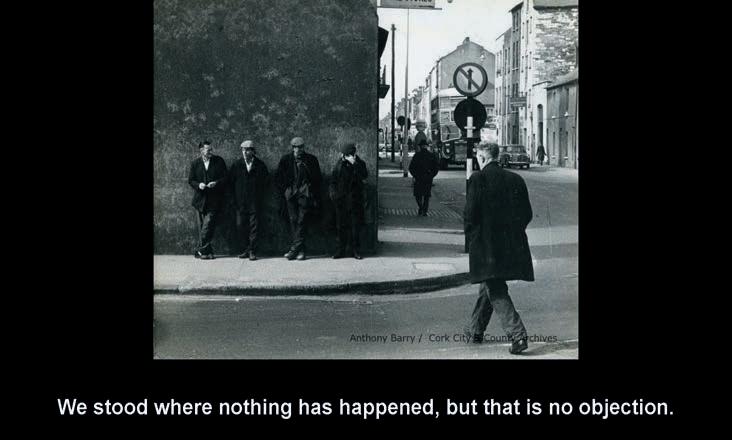

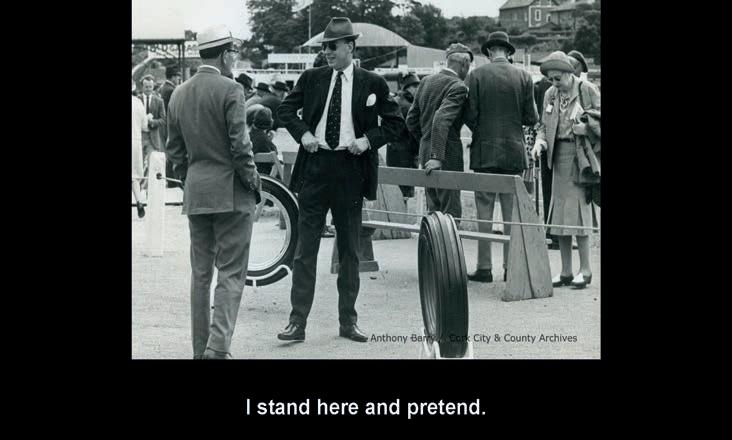

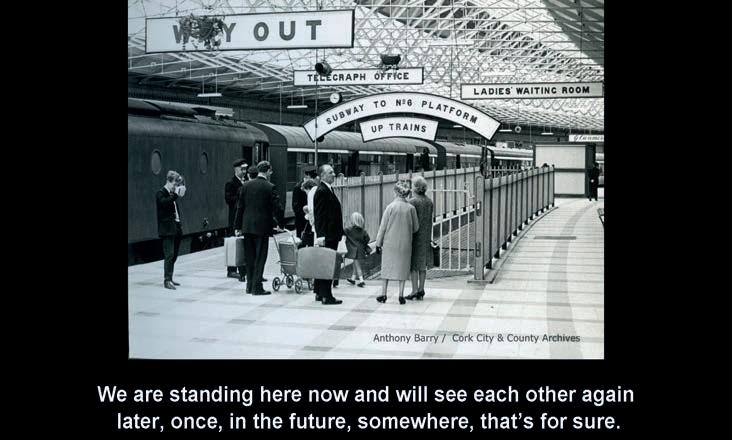

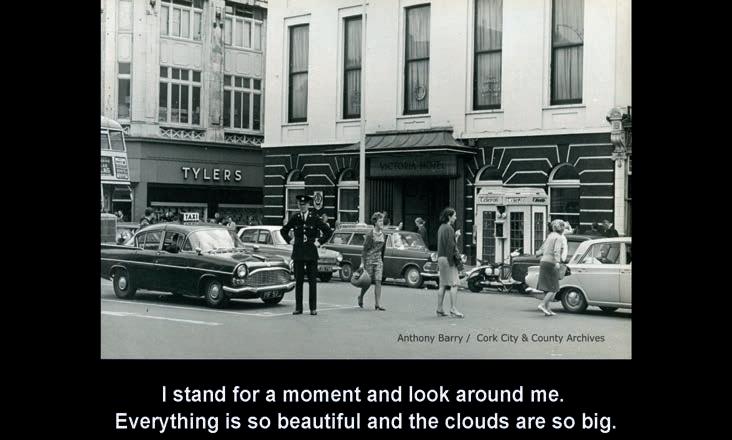

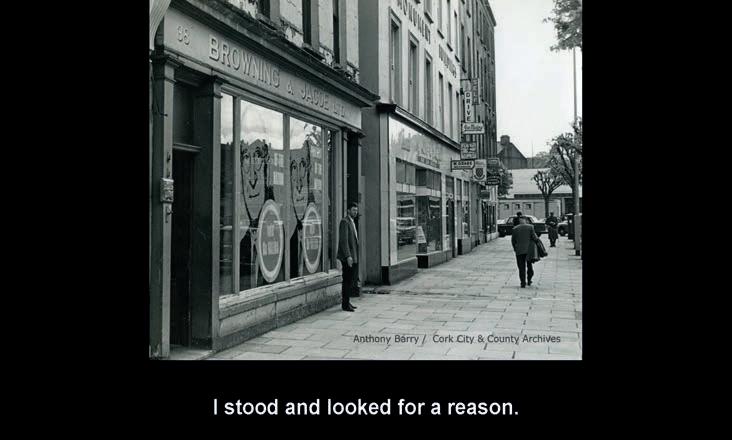

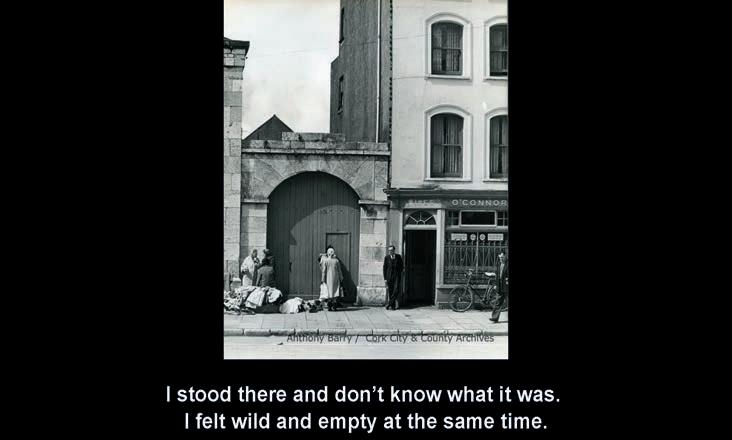

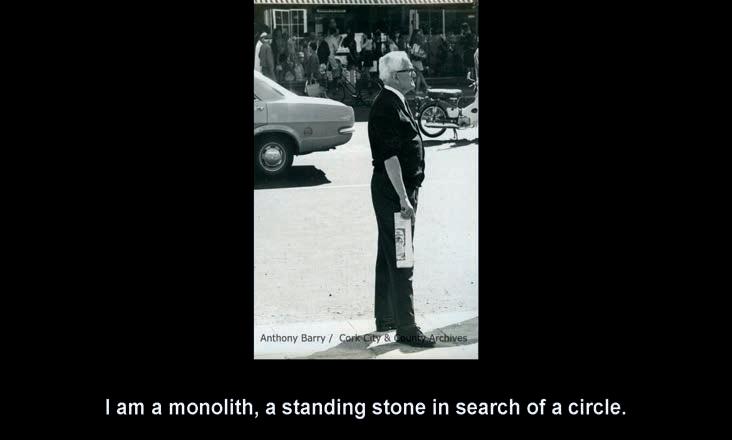

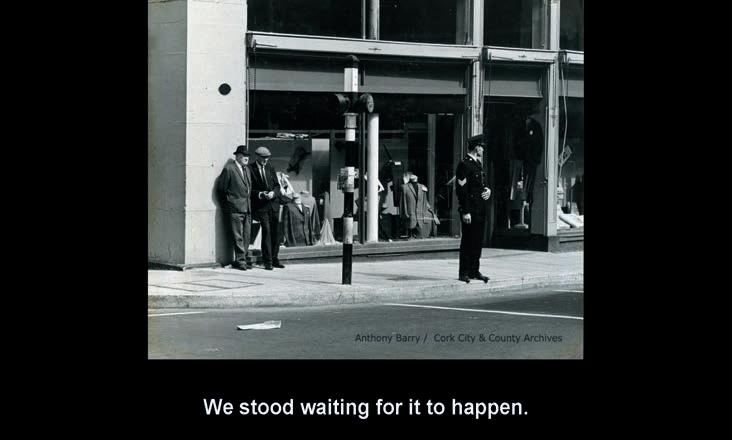

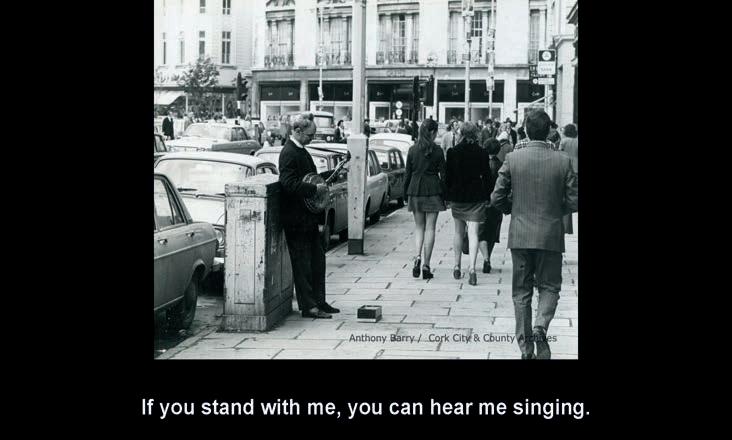

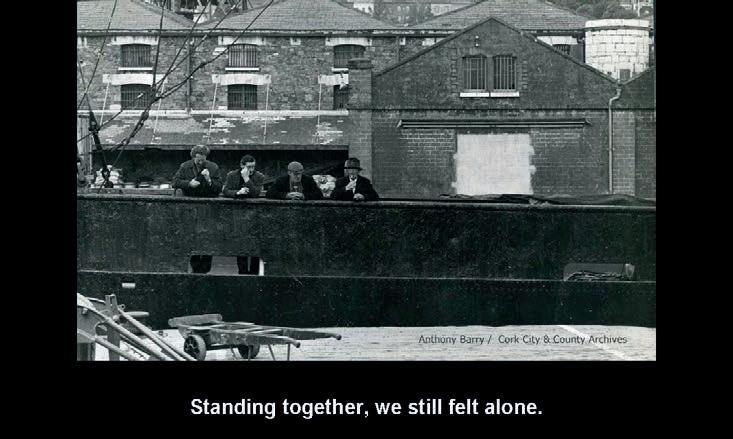

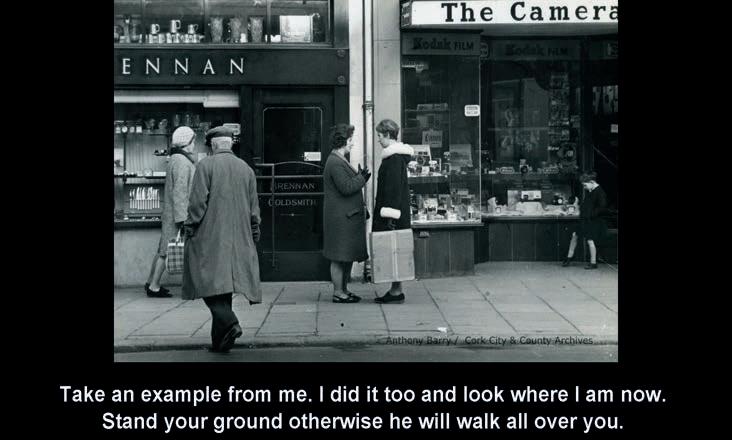

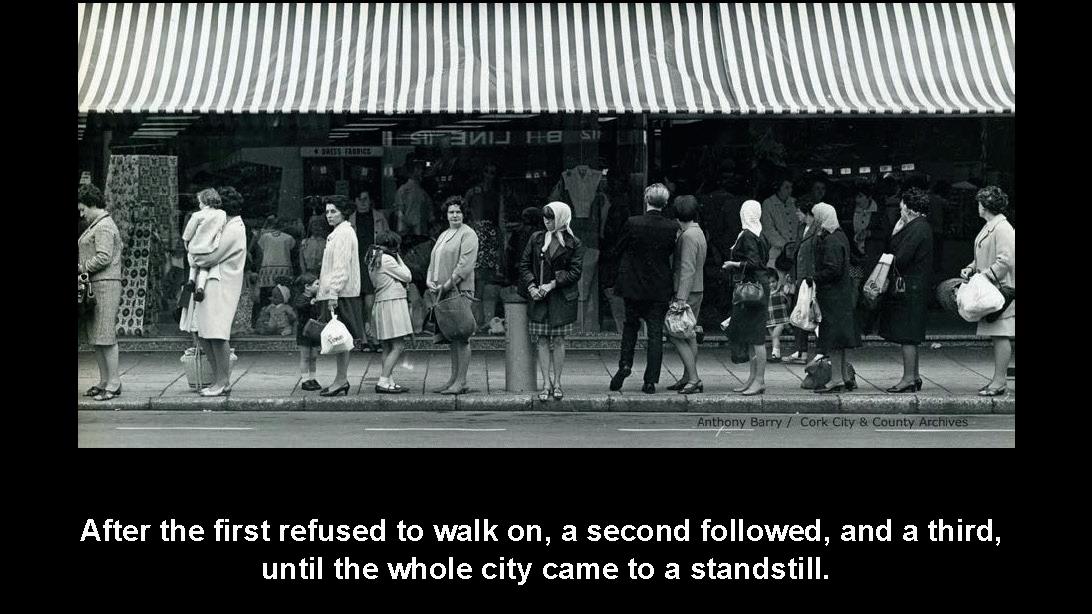

With the diptych ‘Walking / Standing’ he offers an outsider’s view of the collective memory of the city of Cork. The past that everyone thinks they already know is given a new, unpredictable charge through his alien gaze in which he turns anonymous passers-by into the protagonists of their own story. Through texts he gives the anonymous characters in the images a personality and a face. By choosing a different angle in looking at archive materials he wants to offer the viewer a sense of historical sensation, a feeling of brief and direct contact with that distant past.

For this collection of texts and photos De Kluyver used the photographic archive

of former Lord Mayor Anthony Barry (b1901-d1983), a unique collection of photographs taken in person and with great skill by Barry, comprising mainly street scenes of Cork City from the mid 1960s to the early 1970s.

The streets where Anthony Barry took his photographs also recur in Hermann Marbe’s work. They are the same roads over which Hermann walked to work every day. Always one or more cameras in his bag, every day a different view of reality. We now use his amazement and wonder at the seemingly small and everyday to inspire others and share in that experience.

Jess Marbe is a lecturer in MTU CCAD and presents an article about her first experience in working with students to explore Hermann’s photographic archive as a creative pedagogical tool. The workshops were designed to foster dialogue, creative expression and creative critical reflection and to facilitate the students to develop tools and approaches for working with photo images as visual stimuli in their own facilitation practice. The article underscores the potential of photographic archives as a valuable resource for enriching creative pedagogy and fostering deeper connections within educational settings.

Tina Horan and Aideen Cooney visited MTU CCAD during the first phase of the sorting process of the printed images. They selected images that resonated for them to inspire a series of creative writing works that were presented on Cork City Libraries Poetry in the Park in September 2024.

Archivist and visual artist Barbara Diener shows in ‘The Rocket’s Red Glare’ how to connect the personal with the big history in her visual story about the German rocket scientist

Wernher von Braun, who dreamed of a trip to the moon, sold his soul to the devil and developed a long-distance weapon.

Using cameras from The Slow Camera Exchange’s collection, the photographers of the Headway project laid out their very own archive of a place well known to many in Cork but often passed by in a hurry. By slowing down and observing, they both created a whole new view and range of perspectives of the Grand Parade through the eye of each individual and through the lens of the analogue camera.

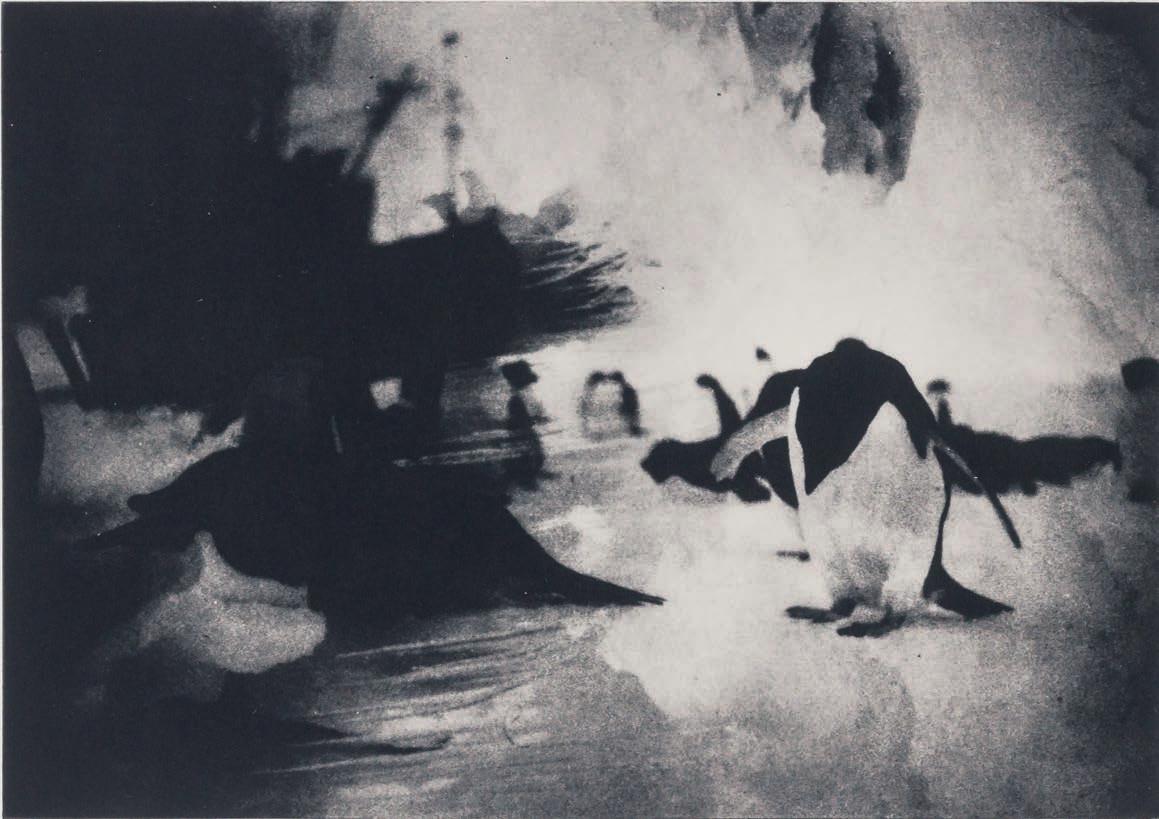

Artist Elize de Beer (who also designed The Slow Camera Exchange magazine and the storytelling game that is inserted in this issue) shares her work with her grandfather’s archive of images of Antarctica made between 1960-1980. For her project Elize manually manipulated her grandfather’s slides; overlaying the landscape, wildlife and man-made influences on the landscape. In this way de Beer connects her family history with the importance that the Antarctic ecosystem has to global environmental concerns.

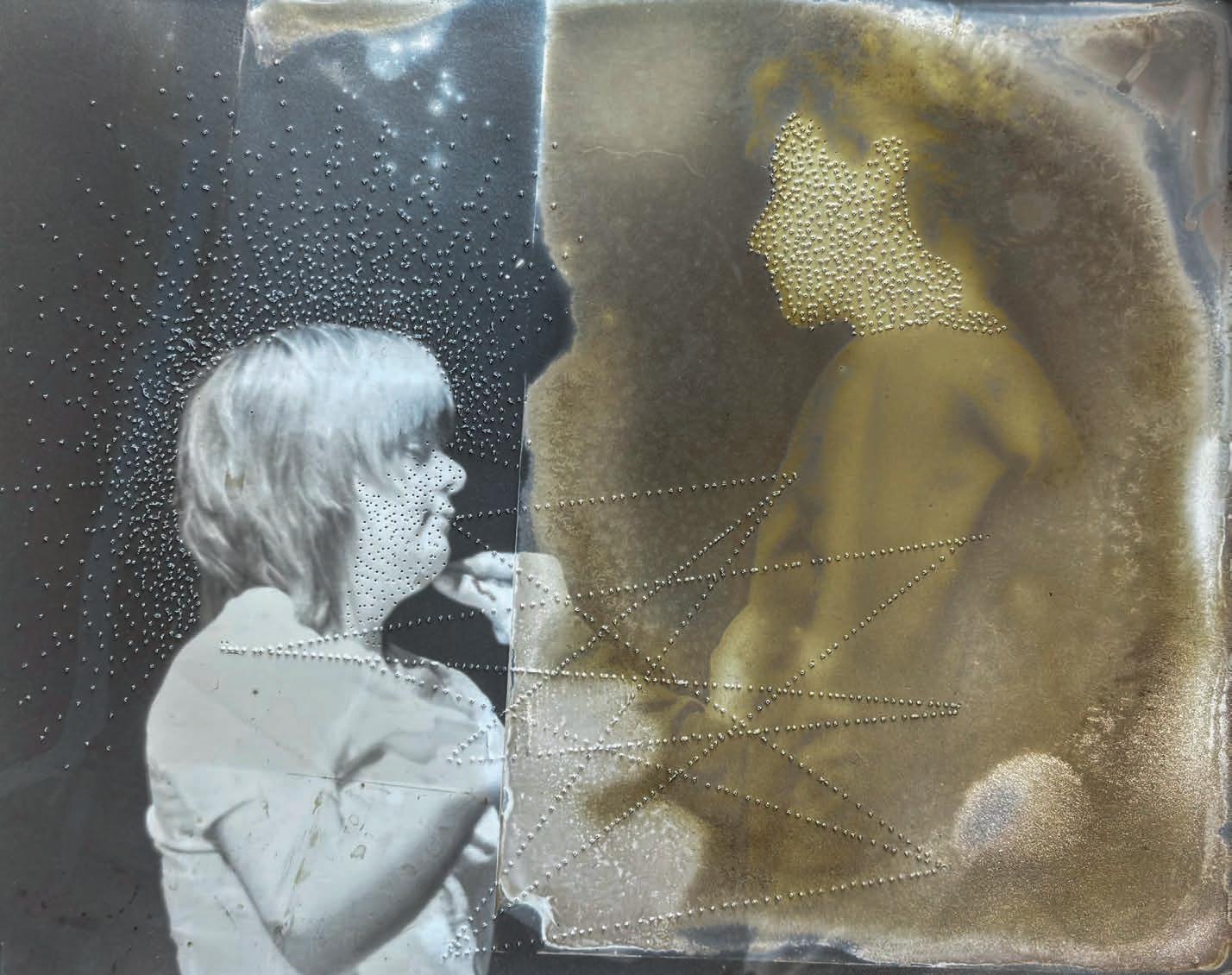

We conclude this theme issue with an artistic reflection by Jess Marbe on her husband’s photographic work. Jess Marbe and Hermann Marbe were creative collaborators when Hermann was alive. This collaboration continues in new forms since his death. In the work, she explores the theme of what it means to co-author work after the death of one partner in the authorship. It reaches for new visual and intuitive dialogue. She shows how you can stitch together then and now, how you don’t always have to fill in gaps, how you can carry the imagination over to a new age. It shows the superpower of the archive.

To honour Hermann Marbe’s playful and curious gaze an additional publication has been created alongside this edition. Jess Marbe and Adwin de Kluyver collaborated to form a storytelling game drawing from the archive. By taking an initial inventory of photographs using four categories - Character, Location, Prop and Wild Cards - new stories are still emerging today supported by game play instructions and prompts. It is a game to play together or alone, with each other or against each other. And suitable for children up to one hundred years old. A downloadable version will be available at a later date on The Slow Camera exchange website; www.theslowcameraexchange.com

Jess Marbe and Adwin de Kluyver

Abutterfly sits still on a leaf. A salamander climbs a branch. A man climbs a tree via a rope ladder. The images are in diaposition on sheets of glass. Black is white and white is black and together they tell a story. But which story? Slowly, I am discovering that you can always give new meaning to images as knowledge of the context changes.

The glass plates were found in the attic of a house in Passage West in 2010. They came from the legacy of William Farr and were passed on by the family to a photographer in Crosshaven 14 years after his death. Three boxes of fragile glass plates told an adventurous story.

William Farr owned a shop with his brother. He participated in dog shows with his bull terrier in his spare time. And he collected LPs by tenor John McCormack. A reclusive man, his neighbours said. Not very talkative, his family said. He rather kept to himself. He died young, in 1996, at the age of 62. Heart problems. Not exactly an adventurous life.

But those were the last decades of his life. In the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s, he sailed as a crew member on a cruise ship. The whole world passed by his porthole. And he would have had an interest in tropical flora, according to his niece. For his parents, he brought a tree from the Far East, a Monkey puzzle tree. It is said to have been the first exotic tree of its kind in the Cork region. The palm tree still stands today on the waterfront in Passage West. The first story was born.

Story 1

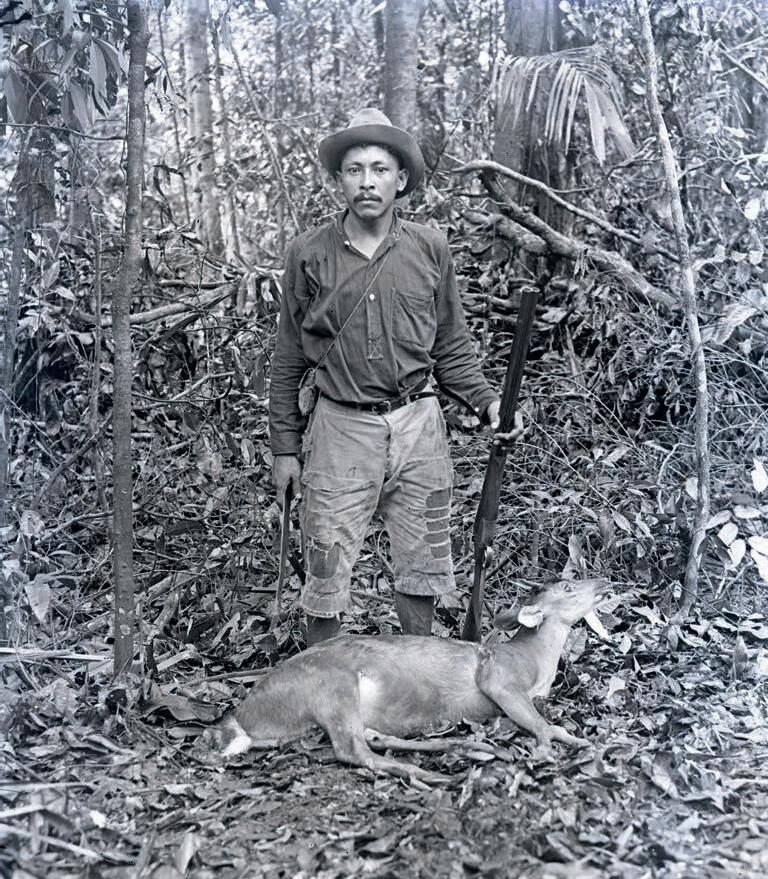

When his ship is in a strange port, William Farr and some other nature lovers head into the rainforest in his spare time. There, he takes photographs of the exotic flora and fauna. Photos of animals and plants unknown in Ireland: a frog, a flower, spiders, caterpillars, flies and a giant beetle. Under a canopy of tent canvas, he determines the plants he has collected.

Later, the family gave me more details. William Farr was a steward on the MS Oriana, the last steam cruise ship of the 20th century. And he was an inveterate bachelor. Of a partner or infatuations, no one knew anything. Back on the mainland in the 1980s and 1990s, he worked in his shop, looked after his dog and travelled to dog shows.

I am researching the cruise ship. Did the crew members of the MS Oriana actually have time to go into the jungle and research flora and fauna? Then I stumble upon a hidden world I knew nothing about. The official advertising slogan for the luxury Oriana cruise liner read ‘Every meal a banquet, every steward a movie star’. The crew members of the Oriana used their own recommendation ‘Every meal a banquet, every steward a queer’.

Homosexuality was still punishable in Ireland and the UK at the time. But cruise ships were sailing oases of freedom in those years. There, homosexual men could be openly

gay, have relationships, behave extravagantly, without anyone disapproving of their sexual orientation, nor their behaviour resulting in imprisonment. Was the man from Passage West on that cruise ship living his dream? Was he who he wanted to be?

His niece sends me a picture of a ceramic plate on which his picture was printed. A souvenir he had made during a visit to Hong Kong. A cheerfully smiling man with wavy hair and a side parting.

I look at a glass plate. There stands an affable smiling man, wavy hair, with a side parting. His foot has been casually placed on a tree stump. His hand rests on a canvas shoulder bag he carries crosswise across his chest. Around him dense vegetation. The next story presents itself. The palm tree still stands today on the waterfront in Passage West. The first story was born.

William Farr is a lover of tales of exploration. At sea, in his sparse spare time, he reads the travelogues in the ship’s library. The tough explorer had hero status at the time and was a popular and attractive role model of masculinity. Together with other male crew members, William, inspired by his heroes, set off into the wilderness at every spare hour. They put on tropical helmets and let locals sail them through the jungle for little money. They camp in tents and fish in the river. A native man shoots a doe for dinner.

Was this plausible? From an earlier study of heroism in the polar regions, I know that in the 20th century it was not uncommon for workers working far from civilisation to sometimes trade exploitation for eploration. In the far north, miners in the Arctic then behaved like polar explorers on weekends. Inspired by travel accounts of explorers and novels by Jules Verne and Jack London, they went into the wilderness on weekends. In their home reports, they told not about their boring, monotonous work, but about their exciting trips in their spare time, just like the explorers they admired. As ordinary boys, they could briefly be part of the story of the great men.

Young men were drawn to the aura of freedom and adventure that surrounded the wilderness. In those days, explorers were considered role models for the youth and were the pride of the country. Workers copied their famous examples in their diaries and memoirs.

Only the extraordinary and extreme made it into the reports. A weekend trip was sometimes described as if it was a month-long survival trip. When in reality, a plate of hot food was ready in the staff canteen in the evening and daily work awaited the next day. Was William Farr such a hobby explorer? Out in the jungle on Sunday with a tropical helmet, serving at the captain’s table on Monday with a bow tie?

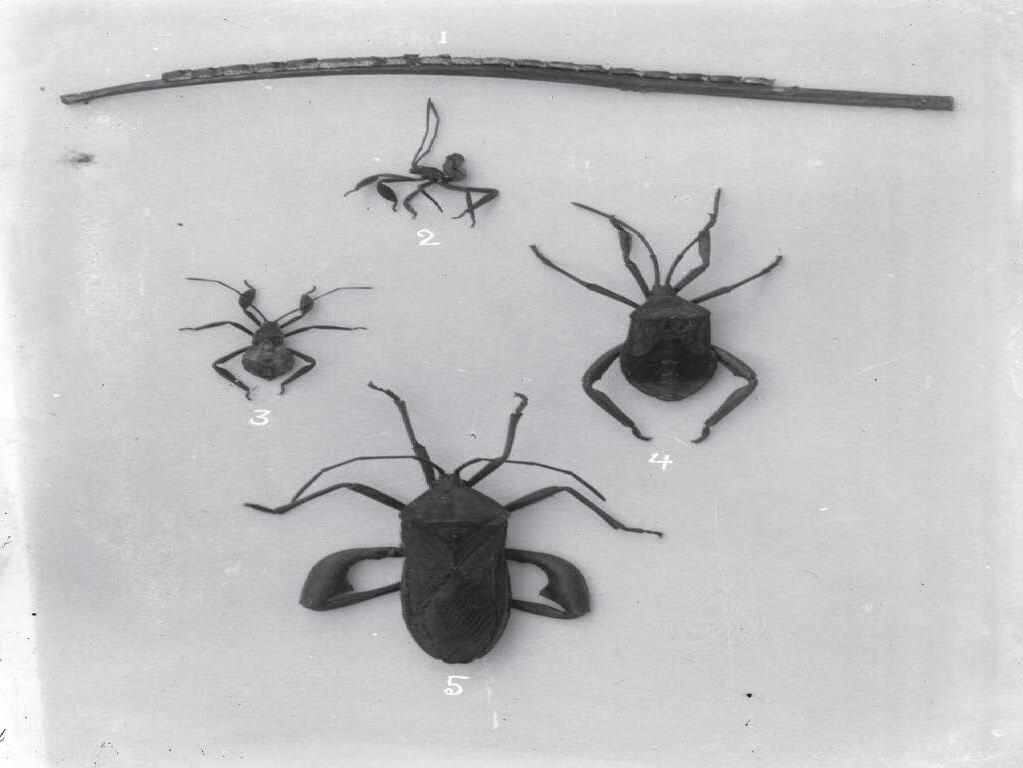

Then there is something else that puzzles me. Why was a world traveller in the 1960s and 1970s still taking photographs on glass plates? The method was by no means user-friendly, especially in the humid rainforest where glass plates hardly dried and the chances of failure were high. Besides, there were much simpler, consumerfriendly cameras available at the time. Point, shoot and done. I discover that one of the boxes of glass plates is labelled. Ilford Special Rapid Plates. As it turns out, the plates in question were no longer being made by the mid-1930s.

Then, in one of the photographs, I see a wooden box standing under a giant tropical tree. The photo has been scanned in high resolution and I manage to zoom in. With some difficulty, I can read the inscriptions and labels on the crate. Oxford University Expedition to British Guiana. There is some more writing on the crate: passenger to Demerara. At 346 kilometres, this is the longest river in the South American country, flowing into the sea near the capital Georgetown.

I find a third story.

The British Guiana expedition takes place between 1929 and 1931. The expedition leader is Richard Hingston, a doctor who participated in the Everest expedition just a few years earlier with Mallory and Irvine, the two mountaineers who never returned from their climb to the highest peak. Hingston did return and then went on an expedition to Greenland. There, in the cold, the idea arose to organise a research trip to the warm tropics as well. In the British colony of Guiana, north of Brazil, they will map the flora and fauna in the treetops. They will sail up the river in canoes. With the help of locals, they build plateaus high in the foliage and record life in the upper layer of the rainforest.

Richard Hingston lived in Passage West. He studied at University College Cork. There, in the archives, they still have a small collection of postcards and letters. In Passage West, the small maritime museum entirely by chance has a temporary exhibition dedicated to the once famous resident. The placards with photos have already come loose from the hanging systems. Half rolled up, they hang askew in the museum space. Fame is fleeting. The exhibition is mainly about the Himalayan expedition. A journey during which Hingston also took photographs on glass plates. Also in a display case is the book published in 1934, the year William Farr was born: A Naturalist in the Guiana Forest. I purchase the book later. Two photographs match the glass plates found. The text also talks about

photography during the expedition.

“,,Anyone working in these damp forests must be prepared for serious photographic disappointment. Snapshotting is quite out of the question in the gloom underneath the canopy. Then the light is not only dim but peculiarly tantalising. Each crevice in the canopy lets in a stream of sunlight which is reflected here and there from leaves like a mirror, and this ruins an exposure for any object standing on the forest floor. The only chance is to wait until the sun is clouded and go in for prolonged exposures. If the lens is turned up towards the sky the invariable result is a conspicuous halation which makes pictures of the tree-roof taken from the ground a matter of extreme difficulty. Each subsequent stage in the preperation of the picture has its particular snag. Films soften in the warm chemical solutions; they stick to aprons in the develop ing tanks and blister or melt in the fixative mixture; they refuse to dry in the humid atmosphere or flying insects man age to stick to them; when finally dried and packed away they make a splendid medium for the growth of moulds. It is important to develop the first thing in the morning when the air temperature is at its lowest. The use of freezing mixtures and hardeners is very necessary and the employment of hypokiller will be found useful. Above all, a fair degree of patience will be called for in order to deal with each snag in succession, and in the end one may be well content if out of every four or five exposures only one happens to be satisfactory.’’

But how did the explorer’s glass plates end up with the shop owner? William Farr lived in Passage West near Horsehead House, the mansion where Richard Hingston grew up, married and had children. William was friends with Richard Hingston Jr, knows James Murphy, Hingston’s biographer. When senior died in 1966 and the house was sold, Farr must have been given the son’s glass plates.

But that was not the only thing William Farr received. A visit to the current caretaker, the photographer at Crosshaven, revealed more artefacts. The glass plates included another camera, a mobile darkroom, a development tank and a collection of film rolls encased in sealed metal tubes, specially made for use in the tropics, shelfable until December 1931, the year the expedition returned.

I now have a third story that could be called the truth, but does that make those other stories redundant fantasy or even a lie?

The trigger for the three stories was the discovery of a small, private archive. Historical images that still had no clear context, only the owner was known. Such an archive is nothing more than a fragmented collective memory, made up of countless image fragments. The pictures were a reminder of moments that were once there, but the meaning is fluid.

According to John Berger, the American art critic and writer, well known from books like ‘About Looking’, ‘Ways

of Seeing’ and ‘Understanding a Photograph’, images are more than mere representations; they are dialogues with history, society and ourselves. When we use archival images to tell creative stories, we end up in an intricate dance of past and present, a symphony of context and imagination. In a story, the archive image serves as a channel to briefly connect the contemporary viewer or reader to that one specific historical moment. Through these images, the story gains authenticity and depth and the reader is invited to step into the shoes of those who lived at the time. The archival image becomes a portal that bridges the time gap and makes it an immersive experience.

Authenticity is a cornerstone of immersive storytelling. John Berger often emphasised how images can evoke a sense of truth and reality, even when embedded in the artist’s fictional vision. Archival images, if used carefully, can lend credibility to a story and anchor it in real events and places. This is not to say that archival images are objective truths - far from it. Berger reminds us that every image is a product of its creator’s perspective and the circumstances in which it was made. Yet that historical connection they evoke gives them a sense of legitimacy that fictional or staged images might lack. In creative storytelling, this authenticity can be a powerful tool to draw the audience into the story and make the story resonate at a deeper level.

In his stories, John Berger often blurred the lines between fact and fiction, reality and imagination. Archival images play

a similar role in creative storytelling, walking the line between documentary evidence and creative reinterpretation. When integrated into fiction, they can create an immersive interplay between the real and the imagined, challenging audiences’ perceptions and encouraging them to question the nature of reality. Berger’s approach to storytelling would celebrate this fusion, recognising that the truth of a story often lies in its ability to evoke a deeper understanding and emotional response, rather than in sticking to factual accuracy. Archival images invite us to look not only with our eyes but also with our minds and hearts, creating a deeper connection with the stories they help tell. They remind us that the past is never really over, but a living, breathing part of our present narratives.

Unintentionally, William Farr thus followed in the footsteps of great explorers. With them, too, facts were secondary to drama; the exciting plot took precedence over the sometimes dull reality. This was a natural fit for the writers. But also for the reading public. That demanded adventurous travelogues. The distinction between true and fictional adventures was diffuse. It was of secondary importance whether the travelogue was realistic; above all, the story had to be believable. And for a while, William Farr’s adventures in the jungle were believable.

We now know that he never literally lived those adventures that way, but perhaps he daydreamed about them,

perhaps he led a different life in his mind than his relatives and neighbours could perceive, fantasised at the glass plates he had been given by the explorer’s son. What is certain: William Farr did sail a ship around the world several times, and after all those voyages he gifted his parents an exotic tree he brought back from the tropics, that is for sure. But thanks to three boxes of glass slides, we now also know that he undoubtedly led a different life on a cruise ship than on the mainland, a life that no one knew anything about. A life that certainly had happy moments. Those moments may not have been on the glass plates, but they were captured in a photo on a porcelain plate from Hong Kong.

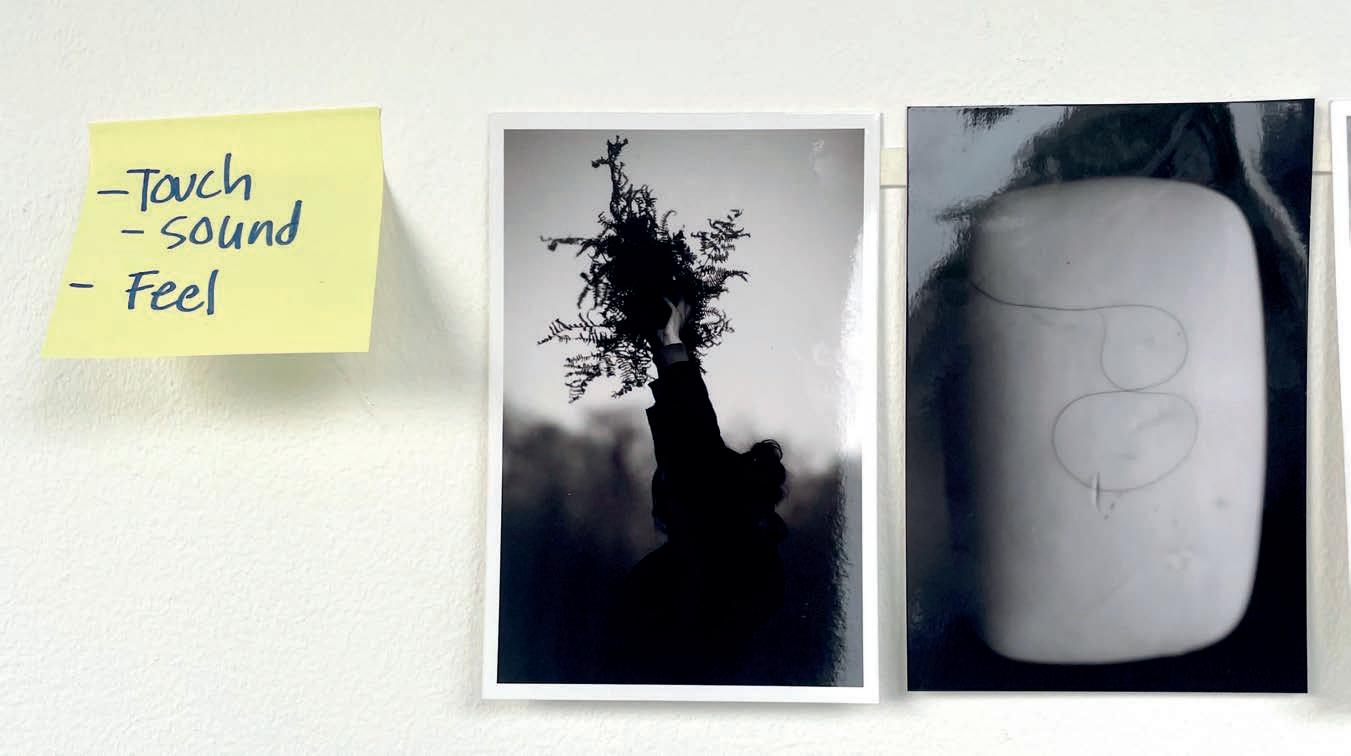

In a world increasingly saturated with words, sometimes images tell the story best. Picture this: a quiet room where a circle of students from diverse backgrounds sits surrounded by an array of evocative photographs—each image a portal to unspoken thoughts, ideas and feelings. This scene unfolds during a workshop in November 2024, where students from MTU Crawford College of Art and Design’s MA in Arts and Engagement and SPA in Eco Arts Practice delved into the art of elicitation of thoughts, concepts, metaphors and emotional resonance through Hermann’s photo prints.

The objective of this workshop was to support students to begin creating tier own collections of images and to develop a toolkit that could be used in their creative facilitation processes to support dialogue, concept development, and creative output.

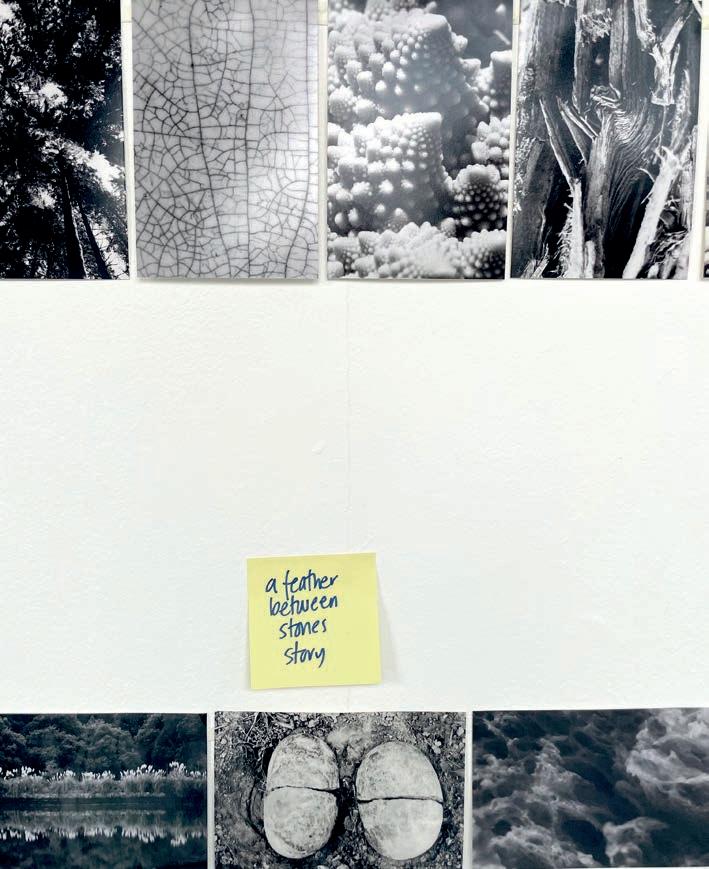

A few days earlier, I had placed a row of images in my office, alternating between those with dark, strong contrasts and those with light, subtle contrasts. This was a playful process, engaging with the aesthetic qualities of the images. Taking a break from the computer screen, I allowed myself to immerse in the images without specific intentions—a momentary respite from thinking and planning.

On the morning of the workshop, I was in the office reflecting on how to begin the session with a group of students from various parts of the country. Each student brought their unique life story, as well as the shared experience of being MA students managing pending assignment deadlines. I wanted to gauge how everyone was feeling upon arrival

to better facilitate their needs and create space for them to reconnect with each other.

Looking at the images on the wall, I considered how difficult it can sometimes be to articulate the full range of our emotions when asked how we’re feeling. Depending on our mood or recent experiences, we might focus on certain feelings and overlook others. I wondered if contrasting images could help express deeper emotional nuances and foster a sense of connection within the group.

To create a welcoming and supportive atmosphere, I arranged a wide variety of images in a circle on the floor before the students entered the room. I asked each student to choose two contrasting images that caught their attention. They were invited to sit with their selected images for a moment and reflect on any resonance between the images and how they felt in that moment. Then, they shared their images and thoughts with each other, if any arose.

For me, as a facilitator, this process emerged from the playful act of placing contrasting images on the wall rather than starting with a cognitive question and designing a methodology around it.

Using playfulness, creativity, and an intuitive connection to the images became the foundation of the workshop process. Students were encouraged to create collections of images they felt drawn to, curating and editing based on perceived connections or resonances. For instance, some students grouped images that evoked themes of journeys

and transitions, such as paths winding through forests or bridges stretching over rivers. Others focused on the interplay of light and shadow, exploring ideas of contrast, liminality, and the spaces between actions or events. They were asked to play, collect, and arrange the images, and then reflect on the themes, questions, and concepts that emerged. Themes such as exploration of the senses, exploration of liminal spaces, the unknown, the in between, the pause, journeys, transitions emerged. Questions like...what it is crux of your story?....what is the moment before the turning/ the telling? the moment before sunrise/ sunset? How do we move between one thing and the next? What happens in the in between spaces? As themes emerged and possible contexts and uses of the image emerged the students found additional images to add to their collections.This process became a flow between the interplay of the cognitive mind and playful intuition. This approach highlights the value of letting images “speak” before engaging the cognitive mind or forming thoughts and concepts.

Together, we reflected on how creating spaces and processes with images can support deeper dialogue and creative flow in facilitation.

Below are some insights gained from this experience:

• “Humans can see and identify with what they see before they can name and articulate it. Images bring us back to the potential of preverbal expression. By zooming in and out, you can gain both micro and macro perspectives.”

• “Images remove the pressure to respond immediately. They might help you realize emotions you hadn’t noticed, offering new insights for yourself and those you share with.”

• “Images evoke an emotive quality that goes beyond verbal expression, allowing you to reveal yourself in a less self-conscious way. They anchor your reflections, providing something tangible to work from instead of grappling with nebulous thoughts.”

This short experience demonstrated the potential of Hermann’s photographic archive to support dialogue and creativity across diverse settings. Images have the power to connect us to ourselves, our stories, the world around us, and each other.

The students continue to work with the images, using them to help explore and share their stories of connection or disconnection with nature, using images to help process articles and concepts connected to eco arts and creative pedagogy and to discover new ways of thinking, expressing, and learning together.

Thanks to students involved in this exploration of the potential of the photo archive.

What are you looking at?

Your veils are thin with sadness

What gives you the right to look at me?

My veils are light with hope

You with your fancy cameras

Shutters of air, breathing in life

You judge me from the outside

White and filled with delicacy

No sense of how rich I am

Holding the lost innocence of childhood

dreams

Sorry if I judged you harshly

Maybe someday I could be your friend?

Dancing in the fabrics of new dreams

Tina Horan & Aideen Cooney

CLIMATE CHANGE US

I’m reminded Hiroshima’s lament of atomic destruction

Her tears still flowing

As we land fill

As we co 2 emit

As we consume

More than we need

More than the earth can offer

Winds picking up speed

Forceful in their reminding

Fires burning our skin

No water to cool us down

Can Hiroshima’s lament

Touch our hearts enough

That we may not continue

To destruct?

Aideen Cooney

My grandad was always amazed by clocks,

The mechanism of little hands, Moving “clock wise” telling us

A particular happening was at a certain time

Punctuality was his most memorable virtue

Always present, ready waiting, Landing, arriving, on time

Dancing on time, in step, in rhythm,

To be one minute late was not good enough

To be one minute early was a disaster

One, two, three, one two, three, Waltzing in time,

A clock in every room of the house

The chimes in keeping with each other

Time to pray, time to sleep, Time to wake, time to kneel, Time to come, time to go, He came, he went,

On time

Tina Horan

I always associated you with lighthouses, You, standing tall and strong

Amidst waters visible and invisible

Your light, guiding my way

With gentle graciousness you lit my path

As I navigated my way

Through this world

You, my safe guard

Ever present through easy and turbulent seas

At times, lost beneath drowning waters

Your light enveloped me

In the midst of breath taking sunny days

I circled you with heart strings of pure delight

You, content to be amidst waters

Clearly knowing and loving your purpose

You lit up my world

You in this life, no longer just a lighthouse

You became my home.

Tina Horan

Slip, sliding, slid

Holding tightly, while letting go

Trusting the propensity of gravity

Feeling the playful joy

Resistance

Holding tightly, praying to let go

Fighting the natural flow

Stuck in limbo

Decisions to make

Which and what way?

You will be held in your landing

Let go!

Aideen Cooney

In the sea she went for peace

Away from the demands of this life

No washing, no folding, no feeding

No listening to sad or happy stories

Just peaceful and easy, swimming

In her own welcoming sea

In her own meditative world

The sea was her hiding place

No one could find her there

Her soul replenished, restored

Her soul returned often

She was at one with the sea

The sea, her soul

Her true home

Tina Horan & Aideen Cooney

From an early age my interest in photography was intertwined with a desire to create an archive. I wanted to capture moments, hide them away and keep them safe forever. My concept of forever at the time was abstract but the motivation to preserve and share photographs has stayed with me through several decades now. If one has access to a camera, which used to be less ubiquitous than it is now, it may just be human nature to want to capture our loved ones and our adventures, but if it is hereditary, I suppose it does run in my family. I remember spending hours pouring over the photo albums my mom had compiled of family vacations, birthdays, reunions, or just my first haircut, my dad and I featuring prominently throughout. My grandfather, who I unfortunately never got to meet, was an avid photographer, as well, and I don’t remember many occasions where a camera wasn’t pointed at me. I suppose I picked up the camera myself to turn it onto the rest of the world in an act of self-defense. Mind you I still succumbed to the temptation of the occasional self-portrait.

Photographic archives are a rich source for multidisciplinary research. Historians use them to piece together events and social trends, while anthropologists and sociologists analyse them for cultural insights. Art historians might study the evolution of photographic techniques and styles, while genealogists and community

historians find personal connections within these visual records. The interpretation of photographs often requires contextual knowledge, as the meaning and significance of an image can shift based on the circumstances of its creation and use.

My interests in photography and archives all came together when I started working on my project The Rocket’s Red Glare. In this series I used the life of instrumental German rocket scientist, Wernher von Braun, to explore the selective way history is told. This series challenges the often dual retelling of significant 20th century events, starting in Nazi-era Germany and culminating in the moon landing. My interest in interpreting this chain of events comes from my own reckoning with history and my complicated German heritage surrounding World War II.

I was born and raised in Germany to an American mother and German father. The latter, who passed away in 2007, was a young boy during World War II. It was hard for him to talk about the war and therefore unclear to me where my family fit into that historical moment. As far as I know my grandfather and uncle did not join the Nazi Party but both fought on the German side. My uncle was 18 when he was wounded during the last days of the war and died shortly after of his injuries.

For this body of work I made my own

photographs traveling to the places significant to von Braun’s life but I also found great reward in sifting through the archival images associated with him. I visited the US Space and Rocket Center in Huntsville, Alabama, which von Braun founded in 1970. It holds his personal archive. I spent hours in the Historical Technical Museum in Peenemünde, Germany, fascinated by the personal photographs I encountered there of soldiers and their families, who had been stationed in Peenemünde to aid von Braun in developing the V2 rocket. I had the privilege of walking on the historical launch pads of Cape Canaveral, Florida, which were utilised as part of the Apollo program, launch pad 34 being the site of the tragic cockpit fire in Apollo 1, during which astronauts Gus Grissom, Ed White, and Roger Chaffee lost their lives.

I photographed these locations with reverence depicting them as the monumental places they once were. In the archives I came across images so striking I knew I needed to use them in some way. It has, for decades now, been part of contemporary documentary practice to integrate archival materials into a project that addresses the often fraught and blurred lines of fact and fiction. I have in turn taken a very complicated and convoluted part of history and expanded our understanding of it by compositing historical images and my own photographs. With this body of work I was at once creating a visual archive of these historical locales as they exist now, altered by time, and I was also recontextualising archival images,changing how we understand them in the context of time, geography and the records about von Braun’s life. I am drawn to the final product of these composites for their ambiguity and potential to take on new and unexpected meanings. For example, by removing a figure from its original context and placing it into a different landscape I merge the two places— Germany and the United States—and the two different timelines to create a new representation through a contemporary lens.

My complex feelings about my heritage are embodied in Wernher von Braun’s story. A Nazi turned NASA scientist, von Braun’s life was filled with as much contradiction as his groundbreaking rockets, which were used as missiles and spacecraft alike. In 1932, Wernher von Braun went to work for the German army, which fell under National Socialist rule the following year. Accounts of the exact year he joined the Nazi party vary, but by 1937 he was the technical director of the Army Rocket Center (Heeresversuchsanstalt) in Peenemünde where the V2 rocket (Vengeance Weapon 2) was created and tested. These missiles, which bombed London, were manufactured in an underground factory by slave laborers who endured horrific conditions if they survived. After Wernher von Braun was brought to the United States under Operation

Paperclip, a controversial government initiative to capture and extract German scientists, much of his Nazi past was classified for decades to celebrate his contribution to the U.S. space race.

Rather than presenting a complete view of this history, I leave intentional holes in the narrative. These gaps serve as questions, looking at how stories pass through generations and how facts are distorted, embellished or undermined. Working with archives, photographic ones in particular, is a meticulous yet profoundly rewarding process that bridges the past and the present, safeguarding collective memories while fostering new understandings of our shared heritage.-

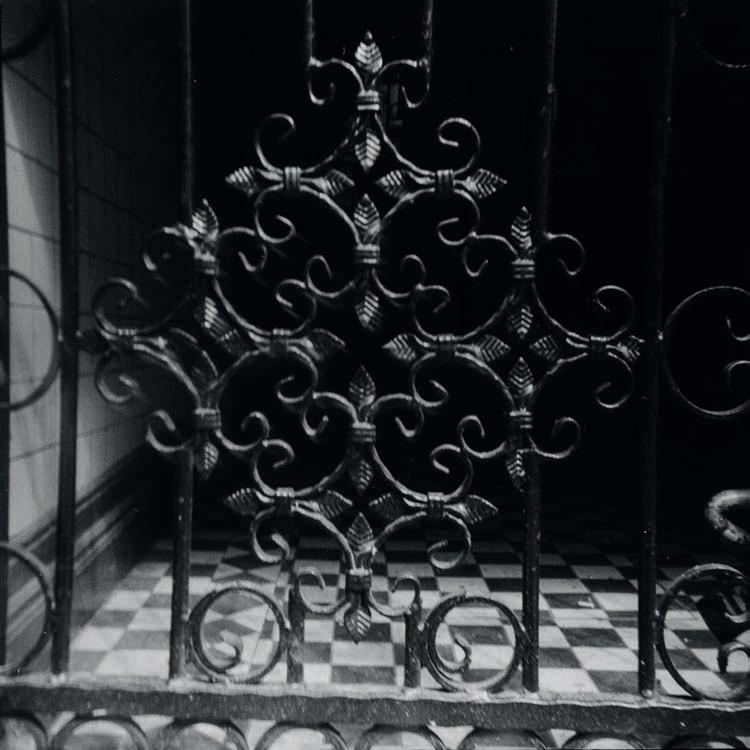

Acquired Brain Injury (ABI) brought us together, and in May 2024, we began a slow, creative exploration of Cork City. Over twenty weeks, we immersed ourselves in the Grand Parade, a public space often hurried through. By choosing to stay, to root ourselves here through analogue photography and conversation, we explored what makes a place come alive. Our project, The Slow Camera Exchange x Headway, offered a chance to inhabit and archive this space consciously, documenting its fleeting qualities without deadlines or goals.

In Cork’s fast-paced, ever-changing cityscape, we found a counter-rhythm—a slower pace that let us observe hints of past lives embedded in building facades, statues, and street details. We discovered that by pausing to observe, by creating our own archive of Grand Parade, we engaged our imaginations in a process that deepened our sense of connection to the city. We asked ourselves: How does moving slowly change our perception of a place? How does lingering instead of passing through shift our sense of the city?

Each journey began with a coffee at Three Fools Café, a lively hub on Grand Parade. From this starting point, we set out with no particular destination,

wandering down Tuckey Street, pausing by an iron gate or an old street name, noticing building renovations or overhead wires crisscrossing above. We laughed at the absurdity of the robot trees—their rough, wooden frames felt out of place and humorously disheveled next to Cork’s living greenery. At the footbridge on Grand Parade’s opposite end, we rested, reflecting on what it means to be at ease here, to feel the pulse of the city.

Our path continued up to South Mall, where stone sculptures created by Headway and Cork Simon Community stand as enduring symbols of Cork’s character, bridging the old and the new. This journey unfolded through spontaneous conversations, snapshots, and reflections captured on film—an analogue archive of our impressions and interactions. Later, back in the The City Library on Grand Parade, we shared our thoughts and photographs, extending our personal archives and reinforcing a shared affection for Cork.

Each participant connected uniquely with the city. Chris, a poet at heart, documented small, vivid details—the quirks of place and people—as his archive of notes and images grew. Eoin, with his humor and artistic eye, gravitated to the new Michael

Collins statue and tree-lined streets, finding quiet encouragement to tune into the birdsong and settle into his surroundings. Finbarr reflected on Cork’s evolving identity, questioning how we might preserve the city’s character while embracing change, adding questions to our collective archive. Ger grounded our exploration in memory, sharing stories of old Cork and its layers of history. Joe moved with openness and curiosity, adding each corner to his own personal archive, as if the project had granted him permission to pause and notice. Justine’s deep appreciation for beauty highlighted the litter marring the streets, sparking her wonder at how anyone could neglect this beloved city. Kristian reminded us of our place on the island itself, anchoring us in Cork’s southern essence.

Throughout, Ailbhe Cunningham encouraged us to slow down and ask questions: How does this place feel? Why does it feel this way? Who shaped it, and for whom? Artem Trofimenko,, with quiet expertise, showed us how to use the film cameras, helping us document each moment carefully and intentionally. In building this archive together, we found ourselves not only recording the city’s physical features but also uncovering the ways in which these details stimulate the imagination,

inviting creativity to reshape our sense of place.

Together, we wove a tapestry of Cork City, each thread unique, each perspective shaped by memory, curiosity, and a renewed sense of place. Through our photographs and zine, we invite you to step into an archive of ephemeral moments, to slow down, and to notice the elements that make any space a place worth inhabiting. In this shared archive, our hope is that each snapshot and story can spark your own imagination and prompt you to create new connections with the spaces around you.

- Carolyn Collier

Rehabilitation Training Officer Headway Ireland. Project Coordinator

Grandparents have a special bond with their grandchildren, the first ones in particular. I remember my grandad teaching me how to use a computer when I was kid in the 90s, before the internet was widely available in domestic settings. Grandad had speech to text software. It didn’t recognise my high-pitched voice as well as it recognised his. He had a large workshop out the back of the house. He made us toys, he fixed his boat, and he built what I can only describe as sculptural installations for his daughter’s wedding cars – one in the shape of a boat, another a horse shoe. To me he was the sort of man who could do anything.

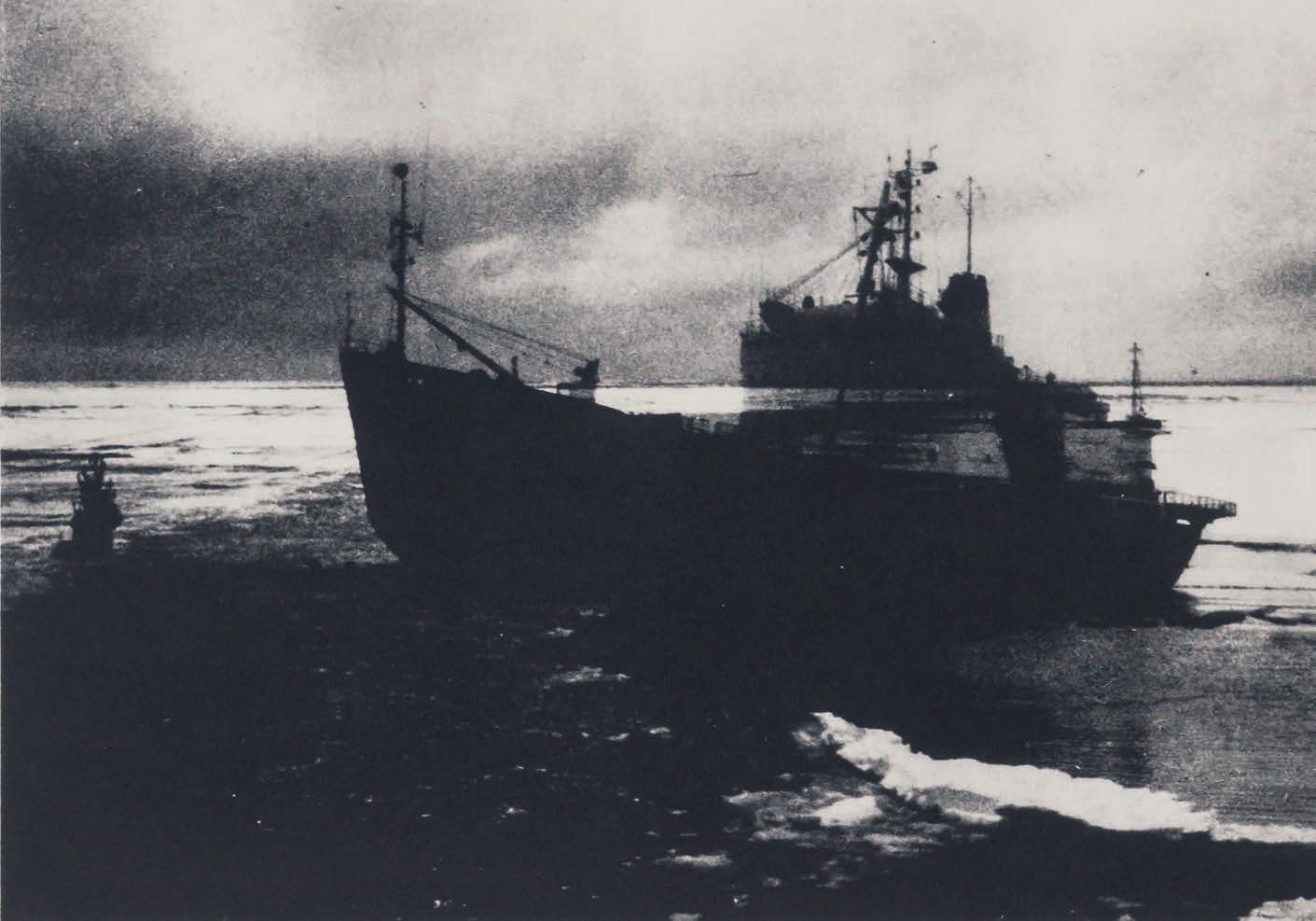

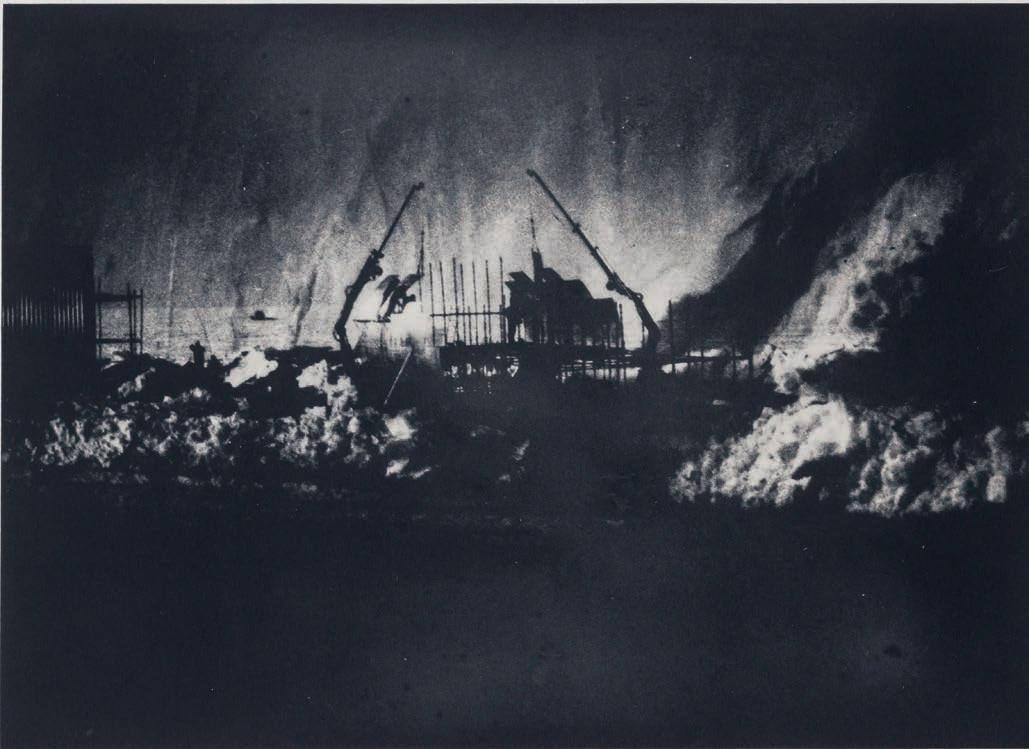

Elize de Beer’s solo exhibition Antarctic Archive is a homage to her own grandfather Willie de Beer. Willie was an engineer and tool maker who worked on South African National Antarctic Programme (SANAP) during the 1970s. As a scientific instrument maker, he was involved in the construction of equipment and research stations on the Antarctic which are still in use today. While there he documented his daily life; he took snapshots of the construction, the already changing landscape, and the natural world. The 1000s of photos were taken by Willie for his own records and exist only on slides. Elize’s parents recently shipped the slides from South Africa to Ireland, this was the starting point of Antarctic Archive.

Discovered in the 1800s the Antarctic was previously known as Terra Australis Incognita: Unknown Southern Land. During the so-called Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration at the end of the 19th Century many died or were injured trying to reach it by boat.

With advancements in technology, an intensive scientific and geographical exploration followed. In 1959 the Antarctic Treaty was signed and it was declared that the Antarctic shall be used for peaceful and scientific purposes only. It wasn’t until 1991 that member nations of the treaty singed the Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty. The Antarctic it was agreed would be set aside as a natural reserve with restrictions to human activity, and all activities relating to Antarctic mineral resources were prohibited, except for scientific research.

What Willie captured in his snapshots was the beginnings of climate change. Studies on the Antarctic then and now help us to make sense of the entire earth system. In 1967 – 57 years ago – earth’s changing climate was modelled for the first time by researcher Syukuro Manabe. It was predicted that temperatures would rise, atmospheric warming would cause ice shelves to disintegrate, and sea levels would rise. As we know, what was studied and discovered then had little impact to negate human or corporate behaviour. We have continued to burn fossil fuels, we have adopted a culture of single use plastics and fast fashion, all in the interests of profit. If this wasn’t reality it would make for the premise of a harrowing horror film.

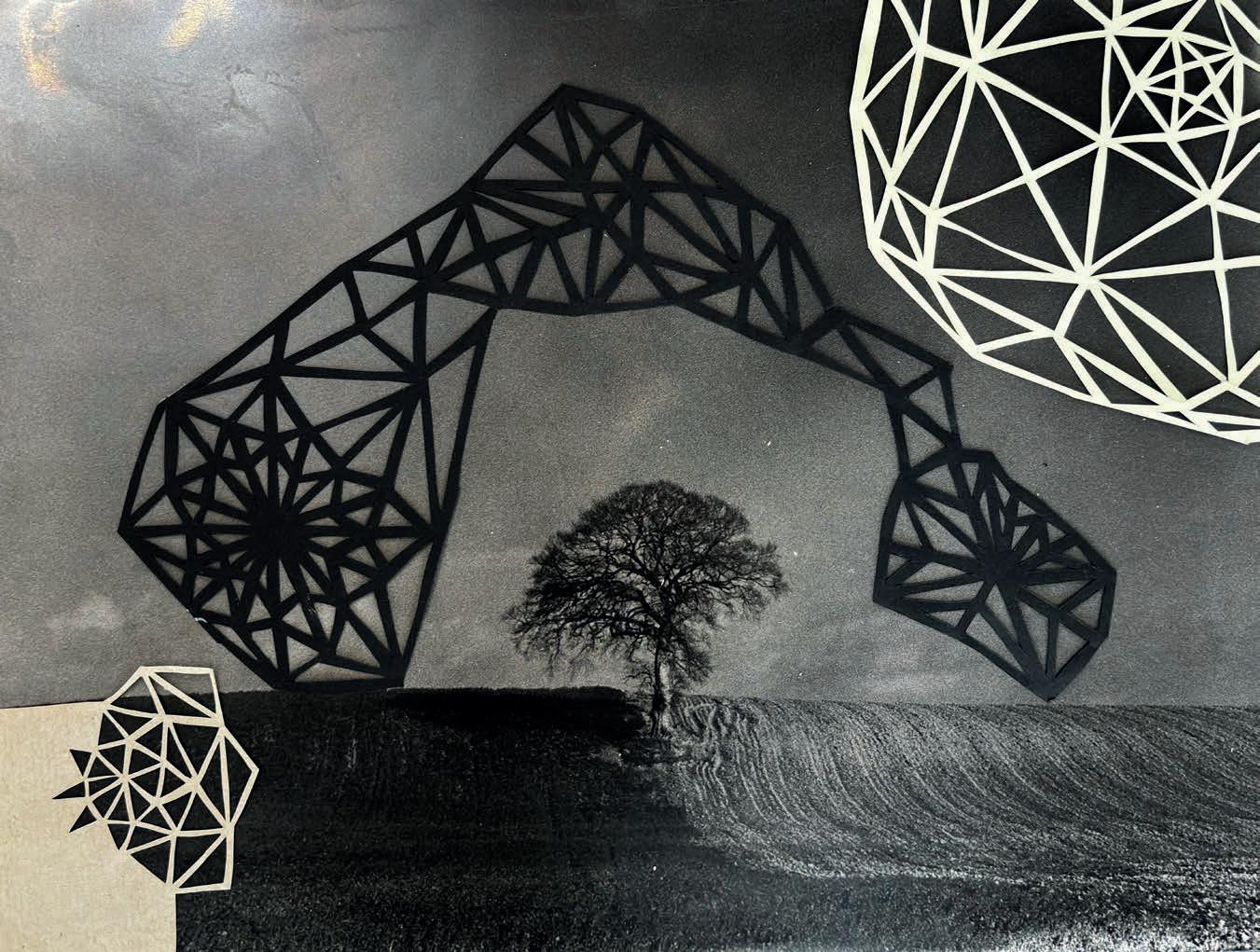

Elize organised her grandfather’s slides into three categories: natural landscape, man elements, and industrial elements. She layered these elements over each other to create photo etchings. Toyobo photopolymer plates were used to preserve the photographic details in the layers. Antarctic Archive III (2024), for example, has three to four layered images consisting of three elements:

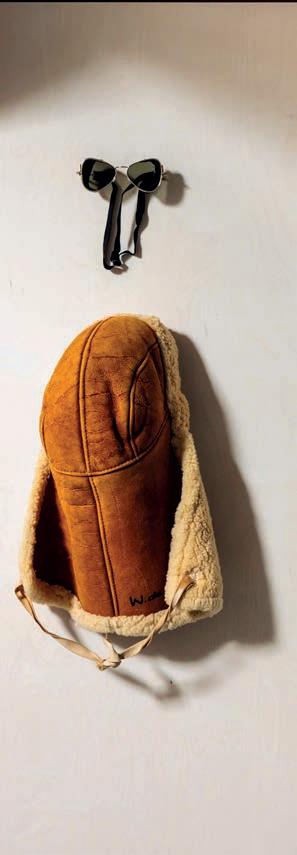

emperor penguins, a ship, and glaciers. As a result of the layering, it is not clear, penguin aside, what you’re looking at. The effect is eery, ominous, and presents a dystopian vision of the Antarctic. Walking into Cork Printmaker’s what you immediately connect with is Elize’s love and admiration for her grandfather. After his death, each of Elize’s siblings and cousins selected an item of his clothing as a keepsake. Elize the eldest grandchild in her family, described her grandfather as a warm, sweet, kind and smart man. He taught her algebra. He had an explorative, creative, process led brain which Elize has inherited. Elize chose his suede fur lined snow hat and snow glasses. They are hung as you enter the space. Willie de Beer is written diligently on the hat.

When exploring shelter types for the Antarctic he created an invertible prototype, a moveable shelter based on a hexagon, which turns in and on itself infinitely. Elize was fascinated by this as a child. The plates Elize used for these photo etchings are sensitive to humidity and heat, Elize spent months testing to get the prints right, and ultimately failed with the plates on the hottest and most humid day of the year. She decided to use the ruined plates to make another sculptural work, her own ‘hexoflex’. Invertible Landscapes (2024) sits in the centre of the room, the plates bear shadowy images of the Antarctic. It does turn in on itself, it’s angular and sharp, it is industrial and an eery reflection of the past.

In Antarctic Archive V (2024) there are people in the foreground, one with arms on hips, and in the background people appear to be marching off in pairs. There is a horizon, and on first glance

there is only sky above, but in fact there are more figures layered on glaciers. In Antarctic Archive IV (2024) a ship is in the foreground – again a horizon is layered with a glacier which cuts out part of the ship, to me reminiscent of what a child would imagine a ghost ship to be, semi translucent moving alone on the horizon. Antarctic Archive I and Antarctic Archive II (both 2024) have structural elements which presumably Willie engineered; they are layered with glaciers, and the effect is a pair of dark images in which the world could be described as burning.

What Elize has achieved in this exhibition is to take a personal narrative: her bond with her grandfather and her admiration for what he did in his work life and the type of man he was; to present on a global topic. The keepsakes she includes – his hat and glasses – draw you in to that relationship, while the prints and sculptural installation draw you out. The images taken between 40 and 50 years ago, when findings were first being presented on climate change, have been transformed by Elize as stark dystopic visions. They reflect what one can only imagine would have been the horror those scientists would have felt presenting their discoveries. Now that we are in this predicted moment – wildfires, catastrophic storms, regular flooding – our climate has undeniably changed, yet we are continuing to prioritise profit, to exist within capitalism, perhaps not seeing an alternative.

Antarctic Archive is presented as part of Cork Printmakers’ 2024 Climate Action Exhibition Programme.

- Emma Dwyer Arts Writer

Installtion imags from Antactic Archive at Cork Printmakers Studio Gallery, 2024.

Paper

Jess Marbe, contributor and co editor, is an artist and educator. She studied at the National College of Art and Design and MTU CCAD, Cork. She has initiated and led local, national and international arts projects and collaborations across art forms and carried out artist residencies in festivals, museums, galleries, both in Ireland and abroad. Jess has been supported by the Arts Council of Ireland through artists bursaries and travel and training awards. Her creative pursuits connect the arts with growing, biking, sustainability and wellbeing. She is interested in the intersection between writing, performance and installation art. She is passionate about the power of the arts to connect and nurture empathy and action. In the last years Jess’s practice has moved closer to home as her motherhood has shaped her practice and interests. She has an increasing passion about well-being sustainable living, biking, growing food and using the arts to imagine with others the future we will create with and leave for our children.

Adwin de Kluyver, contributor and co editor, is a Dutch writer of creative non fiction and a historian. His two books The Northern Dream (2019) and No Man’s Land (2021), a critically acclaimed diptych about the polar regions both received four and five star reviews in national newspapers and were nominated for the Best Dutch Nature Book Award. Last April, his new book The Islands of Good and Evil was published. In it, De Kluyver shows how humans have used islands over the centuries; as laboratories, as locations for natural and social experiments, and as metaphors for the situation in the bigger outside world. The book received raving reviews in national newspapers and was chosen by the Dutch national broadcast network as one of the best non-fiction books of 2024.. Adwin de Kluyver is also a film programmer of a well known art house cinema on a northern Dutch island. There, he organises film festivals around subjects such as nature and sustainability in cooperation with environmental organizations on a regular basis. He also creates exhibitions at the intersection of art and social issues in commission of healthcare organizations.

Tina Horan, contributor, is a Cork based choreographer, mindful movement teacher, maker of short films and a sea swimmer. She runs two dance companies in Cork city, New Moon Youth Dance and Still Waters Adult Dance Company. She teaches all age groups and she loves to work outdoors. Over the last 30 years she has worked on many shows, plays, exhibits with many artists, organisations, schools and universities. Empowering people through dance and movement is her gift. Tina has been crafting written words for decades through songwriting and poetry.

Aideen Cooney, contributor, is originally from Dublin, although her childhood was very much rooted in the rural life of her Grandmother’s farms in both Kilkenny and Roscommon. Cork has been her home for over 15 years. Aideen finds solace in nature and its cyclical rituals whether that is in the heart of the city or the wilder pastures of rural life. She is an Artist, embracing a variety of modalities from paint and poetry films to singing and song writing. Aideen is interested in collaborative practices and her creative work is also strongly influenced by her work as a Senior Art Therapist working in Hospice, where she dances around the thresholds of life and death and finds creative vehicles for expression.

Barbara Diener, contributor, born and raised in Germany, is a lens-based artist currently living and working in Cork City, Ireland. She received her Bachelor of Fine Art in Photography from the California College of the Arts and Masters of Fine Art in Photography from Columbia College Chicago. Her work has been exhibited internationally and her photographs are part of numerous private and institutional collections including

the New Mexico Museum of Art and the Museum of Contemporary Photography. She has participated in several highly competitive artist residency programs among them ACRE in Steuben, WI, and HATCH Projects through the Chicago Artist Coalition. Diener was awarded the Albert P. Weisman Award in 2012 and 2013 and in 2015, 2018, and 2020 she received an Individual Artist Grant from the Chicago Department of Cultural Affairs and Events. Daylight Books published Diener’s first monograph of her body of work Phantom Power in June 2018 and her project The Rocket’s Red Glare was published by Fw: Books in 2023. www.barbaradienerphotography.com

Training

works with diverse groups of people, bringing creative practice to people who do not automatically have access to it. Carolyn draws on her own creative experience - including photography, dance, bookbinding and graphic design. She believes classrooms, in both formal and informal senses, have the potential to become a place that nurtures communities of mutual support; a place where she can promote respect for difference, both culturally and in relation to ability. Carolyn is motivated by an ambition to work with people to find personal meaning in their encounters with creative processes.

de Beer contributor and designer, is a South African visual artist based in Cork, Ireland. Her multidisciplinary practice spans printmaking, books and sculpture and she is a member of Sample-Studios, Cork Printmakers and The National Sculpture Factory. Her work has been shown internationally and nationally. She has artworks in both private and institutional collections, including the OPW, Ireland and the University of Cape Town. De Beer’s expanded print practice uses her dyslexia as a methodology for creating her work. Using her experience of the world, she reimagines written language and the objectivity of books through printmaking, drawing, artist books, zines and sculptures. Her practice looks at ideas of knowledge sharing and hierarchies by exploring archives and libraries,

Cunningham, contributor, is

Architect MRIAI whose practice focuses on the intersetion between researching and doing - actively situating and applying theoretical research within the live context of urban built environments. Working collaboratively with communities of place and interest Ailbhe engages in crossdisciplinary collaboration and participatory knowledge exchange. She recognises the necessity to nurture cross disciplinary collaboration in order to envision resilient, future urban landscapes. Ailbhe is a practice architect at Ample Space and founding member of Cork Community Land Trust (CCLT) and TEST SITE project - each concerned with providing opportunities for creative, diverse and civic engagement in shaping our urban environments.

Artem Trofimenko, photgrapher, is a Cork based artist. In 2018 he graduated from Crawford College of Art and Design with BA Hons in Fine Art. His work was published in Source Magazine Photographic Review in summer 2018. He helped establish Cork Film Centre’s F-stop analogue photography/ darkroom group, where he provides technical darkroom support. He has taken part in numerous exhibitions, including ‘Grá 3x2’ at 3 Walls Gallery Dublin 2019 and the IOVA group show, Dublin 2020 and 2021. During the pandemic he completed a photobook “Tuuli”. In 2021 he received a Visual Arts Agility Award resulting in the photography book ‘Quiddity’ which is in process of publication with Static Age publishers.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

THANKS TO THE FOLLOWING COLLABORATORS

CREATIVE IRELAND

CORK CITY LIBRARIES - PATRICIA LOONEY AND ELIZABETH MCNAMARA

CORK CITY ARTS OFFICE - SIOBHAN CLANCY AND MICHELLE CAREW

CORK FILM CENTRE CHRIS HURLEY

MTU CRAWFORD COLLEGE OF ART & DESIGN

MTU TEACHING AND LEARNING UNIT AND TECHNOLGY ENHANCED LEARNING TEAMS

CORK CITY AND COUNTY ARCHIVES

HEADWAY IRELAND

UCC PHOTO ARCHIVES - BARBARA DIENER

THE DIGITAL ARCHIVING PROJECT IS FUNDED AS PART OF MTU’S ‘STRATEGIC ALIGNMENT OF TEACHING AND LEARNING ENHANCEMENT 2020 FOR THE DEVELOPMENT OF REUSABLE LEARNING RESOURCES.

IF YOU WANT TO FIND OUT MORE

IF YOU WANT TO FIND OUT MORE ABOUT WHAT WE DO, VISIT OUR WEBSITE WWW.THESLOWCAMERAEXCHANGE.COM OR FOLLOW US ON SOCIAL MEDIA: @THESLOWCAMERAEXCHANGE ON INSTAGRAM AND FACEBOOK @SLOWCAMEXCHANGE ON X @SLOWCAMERAEXCHANGE.BSKY.SOCIAL

DESIGNED BY ELIZE DE BEER FRONT COVER: IMAGE BY HERMANN MARBE

FUNDING FROM THE NATIONAL FORUM FOR THE ENHANCEMENT OF TEACHING AND LEARNING IN HIGHER EDUCATION, COORDINATED BY THE MTU TEACHING AND LEARNING UNIT.