The Pacific Sentinel is a monthly student-run magazine at PSU. We seek to uplift student voices and advocate on behalf of the underrepresented. We analyze culture, politics, and daily life to continually take the dialogue further.

We offer a space for writers and artists of all skill levels to hone their craft, gain professional experience, and express themselves. We are inspired by publications such as The New Yorker and The Atlantic. We advocate for the underrepresented and the marginalized.

We are always looking for new students to join our contributor team as we can’t do it without your help. If you’re interested in working with us, visit our website at pacsentinel.com or contact our Executive Editor at editor@pacsentinel.com

DRAKOWSKI

ariana protsman is a graduate student in the book publishing program at portland state university. she is a lover of books, emo music, and hikes involving waterfalls.

becca moss enjoys spending time at her apartment with the fire going and talking rin out of adopting a fourth cat. she graduates this june from portland state university book publishing program and does not know where she will end up and is very much freaking out about it. she is a proud dog mom and will never stop talking about her german shepard.

rin kane is obsessed with her three cats and frequently has to be talked out of getting a fourth. she is also a graduate student in the book publishing program at psu and can be found at shows, stocking up on books about small-space gardening, talking endlessly about getting a criterion channel account without actually doing it, and thrifting throw pillows.

kaitlyne bozzone is a grad student in the book publishing program at psu. she loves discovering new music in her niche genres of choice, sharing pics of her pets, and anything lavender flavored. you can often find her exploring bookstores around portland or rambling excitedly about the various tv shows she’s watching.

kara herrera enjoys anime, PC games, jigsaw puzzles, zoology, D&D, and books. She’s a second-year book publishing student, and has surprisingly really liked learning about book data management and operations. She loves to write about gender crit and yap about post-colonialism, and in general just always has something to say about the media she’s consuming

aj adler likes sleeping (lol), endlessly watching youtube and anime, and her cat (except when he tries to climb her legs /cry). she’s in her final year of graduate school in the book publishing program. she likes writing about art and culture. her comparative literature undergrad degree has to be useful for something, after all.

shaan bir is an Economics undergraduate at Portland State with a strong interest in Labor Economics. He enjoys writing about economic issues that shape our society. Outside of work, he can be found enjoying his coffee at local Portland shops, weightlifting or bicycling outside the city.

ian drazkowski likes to cook breakfast, read speculative fiction, play RPGs and watch baseball. He is a production editor at Ooligan Press and is pursuing his MA in book publishing. As you read this, he is probably sitting on the couch with Terra (his pitbull mix), Spotify daylist playing in the background, either reading, writing, or building a D&D character.

Welcome to our April issue! We are finally in the spring term. The sun may or may not be shining while you are reading this, but one thing is certain: sunshine will be coming soon. Either way, I am happy to be presenting this issue as we chug through midterms and through life in general.

We have a very unique issue for April, with some more lighthearted pieces, as well as some more intense critiques of the world around us. For media reviews, AJ comes back to share a bit about their heritage, as well as a personal affinity and appreciation for the 1998 film “The Prince of Egypt” during Passover. We also see Kara’s return with an evaluation of the 2015 anime “Assassination Classroom,” and how it is not only an excellent watch but also a critique of the Japanese education system. Our talented designer Kaitlyne provides an analysis and opinion of the latest season of “Yellowjackets,” lamenting what could have been and what should have been.

Regarding the news and what is going on in the world around Portland, we have a few perspectives. Shaan returns with a view of the art scene around Portland and how unique and important it is to our community. Rin returns as well with an evaluation of tariffs and its cult-like following as this issue becomes more and more heated. We have a new voice this issue, Ian, who expresses views and opinions of the syntax of the United States and how we should take a closer look at our government.

I hope you enjoy the articles as much as I did. Additionally, I hope each caused you to think and formulate your own opinions as well. I look forward to seeing you in the May issue.

Onward and upward,

Ariana Protsman

BY IAN DRAZKOWSKI

The United States of America is an empire, not a nation. This distinction isn’t just semantic — it is essential to understanding how politics have become so fractured in the U.S.

Protests against DOGE are popping up all over Portland. Meanwhile, concerned parents in Appalachia and the Deep South are rallying at school board meetings to ban books and take controversial material out of their kids’ curricula. How did our “one nation under God” get here?

Theories abound, but asking why and how we’re fragmented ignores an essential part of the equation: just how united were these United States to begin with?

In “American Nations: A History of the Eleven Rival Regional Cultures of North America,” Colin Woodard posits that American nationalism is based on a myth, and a relatively recent one at that. The World Wars necessitated unity among the American people to face common external threats. The emergence of mass media made it easier to promote this unity narrative and Cold War ideological dogmatism created a lasting incentive for the government to perpetuate and propagandize the American nationalist identity.

There are many problems with nationalism: it fosters xenophobia, hinders diplomacy and leads to policies like Trump’s tariffs which have been disastrous for markets both foreign and domestic. In legitimate nation-states these downsides are, at least partially, countered by increased unity, productivity and cooperation. The problem is, of course, America isn’t a nation-state at all and thus hardly experiences any of these benefits.

Americans use the words “nation” and “country” interchangeably to mean the highest autonomous political body, or the broadest category of citizenry. This is troublesome, because many non-American English speakers use the word “state” to describe this same concept. Of course, this introduces confusion because we use “state” to mean a subdivision of the country — what others might call a “province” or “territory.” So “state” either means a subdivision of a country, which is necessarily not the broadest political body, or it is explicitly the word which describes the broadest political body.

Was that confusing? Of course it was. It’s infuriating. Hence why we should instead use the political science terminology, no matter how pretentious it makes us sound. So, without further ado, here are some definitions (source: me, a guy who got a BA in political science five years ago and is very excited to finally be using it):

A nation is a large group of people who share a common identity based on shared factors such as culture, history, language, ethnicity, and/or religion. Notice how there is no reference to territory or political autonomy in this definition. In other words, England, Wales, Scotland and Ireland are nations. The United Kingdom is not. Catalonia, Kurdistan, Palestine, the Tamil people and Tibet are all nations, though they may not be recognized as independent political entities nor do they necessarily have an easily distinguished physical territory.

The terms “country” and “state” are closely related, but carry different connotations. Both are political entities with defined territory, government, autonomy, and the ability to enter independently into international relations. “State,” however, refers more to the institutions — the governmental systems and bureaucracies — whereas “country” usually applies more holistically to the physical land and the people.

Then there’s the scary one: “Empire” refers to a political unit which pulls multiple nations, countries, and/or states under one sovereign authority. The subsidiary nation-country-states might still possess the ability to govern themselves and engage in diplomacy, but that ability is limited and ultimately subject to the empire’s discretion.

One would be hard-pressed to argue that America isn’t an empire. There are clearly defined nations under the control of the federal government. Hawaii. Puerto Rico. Need I say more?

Someone could make a more feasible argument that there exists an American nation, it just isn’t the only nation under the U.S. umbrella. This is an understandable thought, but it doesn’t hold up to scrutiny.

Of the factors that determine nationhood — culture, history, language, ethnicity and religion — the people of the continental United States only really share a language, and even that is up for debate considering unique dialects in places like New Orleans and Appalachia.

Perhaps the most glaring falsehood in the nationalist narrative is the myth of America as an ethnic melting pot. Sure, there are places that see a great deal of ethnic and cultural blending — New York and the major cities of the West Coast being the primary examples. Most of America, however, has been dominantly populated and/ or controlled along obvious ethnic lines.

In the era of globalization it is difficult to say that any modern country is ethnically homogenous. So, in determining nationhood, we look at the proportionally dominant ethnicities and the identities of the original settlers, and under this microscope we see vast discrepancies. East Anglians settled New England and Cascadia. The mountainous West was settled largely by Germans and Scandinavians. Rural Englishmen settled in Virginia and, with their compatriots from the Caribbean plantation colonies, the Deep South. Spaniards and Latinos were the “original” settlers of the Southwest, the Dutch settled New York (originally New Amsterdam). Both the

Pacific Northwest and California were settled by East Asian people at the same time as the initial European pioneers.

Each of these groups brought their own religions, cultures and values, and from those unique foundations grew distinct nations. New England and New York (or New Netherlands as Woodard calls it) have generally allied with each other on political issues to advocate for communalism and a robust government. These northern nations have been summarily opposed by the Deep South for the vast majority of the last 250 years. Which of these sides has been in control has largely been determined by who can persuade Appalachia, the Midlands and Virginia (or Tidewater, per Woodard) to join them.

One would be hardpressed to argue that America isn’t an empire.

This political dance has grown and branched over the centuries, and a full encapsulation of the unique identities, values and policy preferences of the various nations is beyond the scope of this article. The point is this: there is no singular American culture. The empire was born to defend these budding nations from would-be conquerors, and perpetuated for convenience and greed.

The sensible follow-up is to ask why we still need an empire at all, and whether the disparate American people would be better served by smaller regional governments. For fear of being put on some kind of list, I’ll save the secession talk for another forum. Instead, we must let this history inform our approach to politics and to change-making. Consensus at the federal level is near impossible because voters don’t share one culture or nationality. Instead, we must focus our efforts at the regional level, where we are likely to find large groups of like-minded people with the common interests and willpower to shape our society into the best version of itself.

For further reading, see Joel Garreau’s “The Nine Nations of North America” which laid the foundations for Woodard’s “American Nations”. Also check out Bill Bishop’s “The Big Sort” and David Hackett Fisher’s “Albion’s Seed.”

BY KARA HERRERA

Although hardly an isolated case amidst the plethora of popular anime, “Assassination Classroom” initially presents a bizarre, almost farcical premise: a yellow, octopus-resembling creature destroys part of the moon and threatens to do the same to the Earth—that is, unless a particular class of 14-year-old students can manage to assassinate him before their graduation in March. What at first seems like nonsensical outlandishness belies a robust critique of standardized education and the ways in which personal freedom, potential, and creativity are stifled by it.

Initially extorting the Japanese government in order to act as homeroom teacher for a class at Kunugigaoka Junior High, Koro-sensei (a pun on korosenai—“unable to kill”) spends an entire academic year attempting to teach twenty-eight students math, literature, science, social studies, and English (as a foreign language). In addition to also coaching in the art of how to successfully assassinate himself and save the Earth, Koro-sensei attempts to educate the students of Class 3-E on how to succeed in an education system that has up until now abandoned them.

In most Japanese schools, students are assigned a homeroom that they stay in for the duration of their entire school life. At Kunugigaoka Junior High School, Class 3-E is the lowest ranked—a remedial homeroom if you will. Like many other schools, the students at KJH are placed in classrooms according to their aptitude. This is taken even a step further, as Class 3-E is placed in a building isolated from the main campus on top of a difficult-to-get-to mountain, and the students are given disadvantages at the cultural festival, field trips, facilities, etc. The reason for the different treatment is the principal’s utilitarian ideology regarding education. According to studies done on Japanese ants, about 20% of them are diligent workers, 60% are ordinary workers, and 20% are lazy workers. Taking this information, Principal Gakuho Asano utilizes to push one classroom of students to the very bottom of the school social hierarchy; this creates a frantic fear and desperation in the rest of the students to avoid getting places in the bottom class, and it creates, as he describes,a 95:5 rule, where 95% of the student body comprises of diligent workers, and only 5% will be “worthless”.

Back in 2015, The reported that the suicides for kids aged under increases sharply August-September, April... because those coincide with the new school terms.

This setting and context seems a little silly to us perhaps; obviously extreme educational methods like what the principal enacts are harmful and unethical—that’s what I imagine a lot of us would first think when examining this approach. However, the danger in this school model lies in its apparent effectiveness.

While much of what happens in KJH is exaggerated fiction, it is based on some truth of how cutthroat and brutal the real-life Japanese system is. The entrance exams that students need to take to get into high schools and universities are extremely rigorous, and directly dictate the trajectory of people’s lives. Back in 2015, The Japan Times reported that the amount of suicides for kids aged 18 and under increases sharply during AugustSeptember, and early April; why? Because those two periods coincide with the beginning of new school terms. These are disturbing facts, yet why has such a system been in place for so long? The answer is that it does produce an increase in efficient and productive additions into the country’s workforce. How many times have you seen a blogger, a YouTuber, a streamer, or an online article that describes “Japanese efficiency,” or comments on how Japan is living in the future? When these harmful models still produce the desired effect in some

amount of aged 18 and sharply during August-September, and early those two periods beginning of terms.

way, it’s hardly a wonder that they aren’t dispatched or made to change. Yet it is also hardly strange to see fiction and art go about critiquing what is so damaging about the current system either.

“Assassination Classroom” displays its critique through very exaggerated levels of drama and events. And it touches on many different facets of educational discourse. For example, one plot point focuses on a new PE teacher arriving at Class 3-E and how he utilizes violence as a teaching method. Another plot point centers on how parents place the burden of their regrets about the past onto their children. Even the principal, who is the antagonist for most of the story, is revealed to have once been an idealistic teacher who turned to utilitarianism once one of his own students committed suicide. All the students in 3-E as well, each have a unique and personal reason why and how they ended up in 3-E; a major theme of the story being that when education is tailored to the individual, all students can succeed.

It is that final theme that makes “Assassination Classroom” a relevant piece, even for us in America, which has a very different educational system than Japan. Of course, our academic year is different, our homeroom model is different, and we

don’t place as much emphasis on entrance exams. However, I think there is common ground with the idea of sacrificing individualism in order to produce standardized results. Moreover, there is also a similar thread of how strong social pressure, ostracization, and bullying that stems from school performance has an extremely negative effect on self-confidence and mental health, to the point of even endangering students.

“Assassination Classroom” is very goofy, slapstick, and full of layered puns; yet it offers a very pointed assessment and rebellion against the status quo of creating cookie-cutter graduates—a thought that more people should internalize.

Uprising Muse

Dahmer Does Hollywood Amigo the Devil

Caeser on a TV Screen The Last Dinner Party

Mantra Bring Me the Horizon

Mary on a Cross Ghost

Gilded Lily Cults

Slave Yeah Yeah Yeahs

Leave the City

Twenty One Pilots

Long Live (Taylor’s Version) Taylor Swift

A House in Nebraska Ethel Cain

President Gas The Psychedelic Furs

BY STAFF

With May fast approaching, here is a hand-picked list of events coming up. Prices vary from free entry to discounted student tickets. See our online version at pacsentinel.com for more information.

Mini Sledgehammer 36-Minute Writing Contest

April 29, 2025, 5:30 p.m.

Bold Coffee & Books

1755 SW Jefferson St

Portland, OR 97205

Portland Cinco de Mayo Fiesta

May 2-5, 2025, 11:00 a.m.

Tom McCall Waterfront Park

98 SW Naito Pkwy

Portland, OR 97204

First Thursdays in the Pearl

May 1, 2025, 5-9 p.m.

Gallery Opening, Vendors, Performances

NW 13th & Irving Portland, OR 97209

First Friday Art Walk in East Side Art District

May 2, 2025, 6-9 p.m.

Free Entry

Art Openings, Performances, Live Music at 23 Independent Galleries, Shops, and Studio

Rose City Rollers & Disco Night

May 2, 2025, 7-11 p.m.

Hangar at Oak Amusement Park

SE Oaks Park Way

Portland, OR 97202

Japanese American Museum of Oregon

May 4, 11:00 a.m.- 4 p.m

Free First Sundays

411 NW Flanders St. Portland, OR 97209

S2: Small and Self Publishing Faire

May 17th, 11:30-8pm

BOLD Coffee and Books

1755 SW Jefferson St, Portland, OR 97205

Entry is FREE

BY KAITLYNE BOZZONE

For the titular girls soccer team of Showtime’s “Yellowjackets,” there’s no escaping the Wilderness, and no season has exemplified that as much as season three. But fans aren’t necessarily loving the twists and turns the show is taking.

We are far removed from what many online consider the golden age of television. Eight to ten episode seasons releasing every few years can’t exactly hold a candle to the classic format of twenty-two episodes every year like clockwork, nor the sort of fanbases those shows could generate. Still, “Yellowjackets” felt like an outlier: a star-studded cast of talented actors, a compelling mystery, complex and fascinating character dynamics, as well as thoughtful and diverse LGBT representation made the now seven-time Emmy nominated series feel like a dream come true for TV fans.

But now, in the shadow of the season three finale, fans aren’t loving the direction “Yellowjackets” has taken, and it’s easy to see why. The plot was easy to describe in the first and even second seasons: a high school girls’ soccer team went missing in the wilderness, and the terrible things they did to survive come back to haunt them twenty-five years later. Season three starts to shift this a bit.

Now, it seems as though the writers have moved away from the idea of the girls collectively losing their minds, placing the blame of the violence in the wilderness squarely on the shoulders of two of the main characters: Lottie Matthews and Shauna Shipman.

Lottie was always going to take on this role, her delusions and hallucinations serving as the catalyst for the girls’ belief in the Wilderness (capital W this time) as a spiritual force, providing for them in their desperate need, though at a price. Shauna, too, was a complex and morally gray character from the start, someone who clearly wanted to be a good person but was bogged down by jealousy and resentment toward her best friend, Jackie, whom the subtext shows she was clearly in love with.

Here serves your official spoiler warning for all three seasons.

Jackie’s death at the end of season one sends Shauna spiraling, and the more trauma she endures, the larger the gap between her and the rest of the girls becomes. Lottie’s relationship with

the Wilderness and her insistence in what the girls owe it is a consistent factor in driving wedges in the rest of the group throughout season two as well.

Grief stirs violence in Shauna, and the girls’ need for survival in the dead of winter and increasing belief in Lottie and the Wilderness stir violence in the rest of them, too. All of them, collectively, participate in a hunt targeting one of their teammates that results in the death of someone completely innocent: their deceased coach’s pre-teen son, Javi. The aftermath of this death is devastating for them all, particularly Shauna, who must butcher Javi to feed the team, and Travis, Javi’s older brother.

The violence of season three is not the violence of survival but of vengeance and anger

Season three opens in summer, the violence and grief simmering low and merely a story to tell in remembrance of all they’d been through—for everyone but Shauna, whose rage has only grown. The violence of season three is not the violence of survival but of vengeance and anger, led in large part by Shauna.

Everything seems to line up perfectly; so where do the problems lie? Quite simply, season three feels as though the slow-burn loss of morality the team was facing throughout the first two seasons has dwindled away in the comfort of summer, and only Shauna and Lottie are left to stew in the crazy. Logically, it makes sense; narratively, it feels unsatisfying, and like a complete departure from the setup of the premise in the first place. If the blame for all of the misfortune and trauma belongs to only two girls, why would the rest of the surviving team defend or protect those two? Why would the guilt of what Shauna and Lottie have done haunt them twenty-five years later?

“Yellowjackets” is.. interested in the specific unraveling of young women when faced with trauma, mental illness, a lack of grounding in society, and the way that trauma manifests years down the line... this show shouldn’t have clear cut morally “good” and “bad” characters.

Placing the blame on two girls doesn’t work for the multi-faceted story they’ve set up—characters who started as interesting and complex are re duced to cartoonishly evil or obnoxiously crazy.

I can’t help but think of all the TikToks ranking fans’ favorite characters in anticipation of the new sea son, lists that feel more like a moral purity stack up than an interest in the truly interesting and dan gerous characters the show has provided thus far. Social media users have ranked comic relief, with mostly unimportant male characters as their favor ites just because they aren’t the “evil” women the show chooses to focus on. But is that a problem of the characters or the writers, or of the fans not un derstanding the material they’re watching?

“Yellowjackets” is a horror show, interested in the specific unraveling of young women when faced with trauma, mental illness, a lack of grounding in society, and the way that trauma manifests years down the line. The fact of the matter is that this show shouldn’t have clear cut morally “good” and “bad” characters. It shouldn’t be bending to the whims of “fans” who don’t seem to be interested in the show for what it truly is. What comes out of that is messy writing.

I don’t think season three is heinous. But I do think it’s lost its footing somewhere along the way. I hope the writers learn from it, and I hope season four lets all of my evil women lose their minds and shine.

BY RIN KANE

In the strange theater of 21st century American politics, tariffs have taken center stage. Since February 1st, the country has been embroiled in an ever-escalating global trade war with multiple countries retaliating against the Trump administration’s sanctions. Before we dive into the events of the last few months, let’s first clarify what a tariff is. According to CNN, a tariff is a tax on goods bought and imported from a foreign country, “typically structured as a percentage of the value of the import and can vary based on where the goods are coming from and what the products are.”

In theory, tariffs should protect domestic industries from foreign competition by making imported goods more expensive, thus encouraging consumers to buy local. In practice, they often raise prices for consumers, provoke retaliation, and rarely achieve long-term industrial rejuvenation.

In fact, it could be argued that the current administration has thrown away any semblance of protecting American industries and dollars in favor of an intense flavor of nationalism that smacks of attempting to bully its way into re-establishing America’s understanding of itself as a global leader and economic powerhouse.

So how did this all start? On February 1st, President Trump announced an executive order that would impose 10 percent tariffs on China and 25 percent tariffs on Canada and Mexico, citing undocumented immigration and drug trafficking as reason enough to declare a national emergency. The order was met with immediate pushback, causing Trump to suspend the Canada–Mexico tariffs for 30 days while the emergency was evaluated. Since that day, things have rapidly escalated. China predictably announced a mass of countermeasures against American imports as soon as the first executive order was signed. On February 10th, Trump imposed a minimum 25 percent tax on steel imports and raised aluminum tariffs to match. Then, on March 4th as the 30 day suspension passed, Trump implemented his promised tariffs against Mexico and Canada, while simultaneously doubling tariffs on Chinese imports to 20 percent. All three countries initiated retaliatory measures. On March 12th, the steel and aluminum tariffs went into effect. The European Union retaliated with a number of measures, including the threat of a 50 percent tax on American whiskey, causing Trump to threaten a 200 percent tariff on European wine, champagne and spirits. Eventually, April 2nd saw Trump implement a 34 percent tax on China, a 20 percent tax on the EU, 25 percent on South Korea, 24 percent on Japan and 32 percent on Taiwan.

After mass panic over a recession and an economic collapse, Trump announced a 90 day suspension of all reciprocal tariffs, with the exception being those on China. The pause was meant to be celebrated, but economist Joe Brusuelas isn’t convinced that it’s enough to reverse the coming recession. In an interview with CNN, Brusuelas said, “‘many [clients] are going to choose just to leave the products

at the docks — they don’t have the cash reserves to pay the tax,’ he said. ‘So, we’re going to see dislocation across the economy driven by an adverse supply shock.’”

In a cult, the central narrative isn’t debated—it’s accepted. Followers are drawn to the clarity, the absolutes, and the emotional gratification of “us versus them.” This same dynamic has emerged in modern tariff politics. Politicians rally their base by portraying tariffs as a form of economic self-defense—a shield against globalism, foreign invaders, and the perceived theft of national greatness.

Facts—like economic data showing job losses, rising consumer costs, or retaliatory damage to domestic exporters—are waved away. The cult doesn’t need proof. It needs belief.

Cult movements often grow in times of fear or uncertainty — and trade anxiety is fertile ground. The pace of globalization, the rise of China, the decline of manufacturing jobs, and the COVID-19 pandemic all fed a sense of national vulnerability. Tariffs, in this light, offer an emotionally satisfying answer: close the gates, protect our own, punish the cheaters.

Tariffs are not inherently evil. Used carefully, they can play a role in strategic industries or as leverage in negotiations. But when they become a belief system, they stop being tools and start becoming traps.

In that sense, we should be wary of any policy that becomes sacred, any leader who sells emotion over evidence, and any movement that replaces dialogue with doctrine. Trade is complex. So is the world. And the solutions we need won’t come from chants and flags—they’ll come from thought, effort, and, perhaps, a little humility.

Portland’s Art Scene thrives on transformation and isn’t confined to Museums. In a city where coffee shops act as art galleries and skateparks are spaces for graffiti art, art can be defined as a creative cult, rooted in its belief and constantly in flux.

Drawing inspiration from her mother’s charcoal creations, Daniellea’s collection “True Happiness Will Find You in the End” delves into the boundless possibilities of abstract forms, exhibited at Stumptown Coffee, Portland, until April 15th. Stumptown Coffee Roasters has always supported Portland’s local art scene, and their collaborations with artists like Daniellea Gatt (pictured) show how much they value creativity.

images by author BY SHAAN BIR

Gatt’s abstract work perfectly fits Stumptown’s focus on celebrating the city’s unique culture. By featuring her art in the cafe and hosting events, Stumptown gives Gatt a platform to share her vision while helping to strengthen the local arts community. Gatt’s collection explores abstract forms and possibilities, which match Stumptown’s commitment to creative expression. Through this partnership, Gatt and Stumptown are keeping Portland’s art scene vibrant and full of opportunities for local artists. Find more of Gatt’s work @yella1.

Portland’s Pearl District hums with artistic energy, where sleek architecture meets a diverse gallery scene. From contemporary installations to timeless works, each space offers a unique lens into the city’s evolving creative identity. Showcasing everything from painting and sculpture to photography and mixed media, the district fosters a strong sense of community, making it a vital stop for art lovers and curious wanderers alike. Blackfish Gallery opened as a cooperative art venue in Portland in 1979. The impulse for establishing a new gallery originated from the fact that, at the time, there were insufficient galleries to service the area’s numerous artists. The gallery’s origins can be traced back to 1978 when a group of artists eager to help one another professionally envisioned a one-of-a-kind concept – a gallery owned and managed solely by its artists. The original group leased an empty shop at 325 N.W. Sixth Street and created the gallery a year later, using their work, abilities, and ingenuity. The gallery is now located at 938 NW Everett Street.

Blackfish has represented prominent Oregon and Washington artists such as Paul Missal. In a conversation with artist Dede Lucia, she shared how each Blackfish project is rooted in three guiding goals: to present compelling visual art infused with thoughtful ideas; to support artists whose work challenges commercial norms; and to engage diverse audiences through exhibitions that speak to broad, relevant themes. This mission echoes throughout the Pearl, where art doesn’t just decorate walls – it sparks dialogue, invites reflection, and builds connection.

As of April 2025, Blackfish Gallery is presenting “Connections,” a captivating new series by artist Philip Stork. With a restrained palette of monochromatic pastels and pencils, Stork explores the unseen threads that bind us – visually interpreting the cellular networks and subtle forces that shape our world. His large black–and–white compositions offer striking contrasts, while soft tonal shifts create a sense of visual harmony and depth.

Stork’s work evokes both microscopic and expansive realms, inviting viewers to reflect on the environments they inhabit and those beyond their

immediate experience. Through a nuanced interplay of line and tone, “Connections” gently urges us to consider the foundational links in nature, society, and self.

This exhibition marks a bold new chapter in Stork’s artistic journey – one defined by introspection, experimentation, and transformation.

To view more of his work, visit storkartportfolio. com. Inquiries: storkpjs56@gmail.com.

At Blackfish Gallery, artists Hannah Theiss and Noah Alexander Isaac Stein present two deeply introspective exhibitions that explore the intangible realms of memory and spiritual transformation.

In “Qualia,” Hannah Theiss assembles fragmented materials into haunting compositions that reflect the instability of memory, particularly in the context of trauma. Her use of transparency and absence captures the fragility of remembrance, while sudden bursts of color release deeply buried emotion. Theiss’s work invites viewers to confront the voids within their recollections, forming brief, poetic links to the past self.

Meanwhile, in “Luminous Fire from a Broken Machine,” Noah Alexander Isaac Stein turns to fire as a symbol of transformation, of destruction giving way to creation. His expressive use of oil and cold wax mediums creates layered, textured

surfaces that suggest spiritual intensity and emotional catharsis. Through this process-focused approach, Stein aims to create a space where the viewer can encounter something universally human: hope, transcendence, and healing potential.

Together, these exhibitions offer a powerful reflection on what it means to remember, to feel, and to transform.

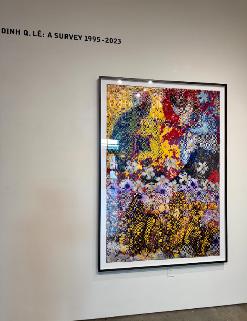

The Elizabeth Leach Gallery presents “Dinh Q. Lê: A Survey 1995–2023,” a posthumous tribute to the late Vietnamese–American artist, who passed away in April 2024. This exhibition spans three decades of Lê’s influential career, showcasing photographs, photo–weavings, and sculptures that reflect his enduring exploration of memory, identity, and the legacy of war. Lê, whose work was first exhibited at the gallery in 1998, used photography to navigate the complexities of East–West identity and Buddhist philosophy. Removed from the commercial spotlight of New York, his Portland exhibitions became quiet meditations on history and personal narrative.

With “A Survey,” the gallery honors Lê’s singular voice and the profound impact of his visionary practice.

More than 30 years ago, Portlanders built their own Skatepark under the Burnside Bridge – known as the ‘Burnside Skatepark’. It’s a pretty amazing work of street art. Jacque Rheingans, a Skateboarding Coach for SkateLikeAGirl Portland, and a Geology student at Portland State, describes it as a DIY (do-it-yourself) and mentions that the space has its unique energy and transition. She recalls it as “Made by Skaters, for Skaters.” According to Jacque, Burnside was the very first fully DIY skatepark to ever be built. It gave skaters a space to express their creativity through the design of the park as well as the annual paintings. Every year, the park is repainted with a new theme by a skater who goes by the name Jaymeer, who has been designing the art for Burnside skatepark for the past thirty years, with some recent themes including desert, jungle, ocean, and current space. The Art

at Burnside plays a major role in bringing the community together and turning it into a destination for skaters across the globe.

Alex Long, a sophomore at Ida B. Wells High School, loves to skate and mentioned that the City of Portland was going to be demolishing the Skatepark due to safety concerns of the Burnside Bridge collapsing over the Skatepark, due to an earthquake. Alex plans on attending Oregon State University after finishing high school. The Burnside Skatepark was constructed around support columns beneath the east side approach to the bridge. The three replacement choices do not require columns in this region, allowing the skate park to stay intact and functional after construc tion. The Retrofit choice, on the other hand, would require tearing down the skatepark and replacing or strengthening all the existing columns.

Portland’s Art Scene reminds us that creativity isn’t just found in expensive pieces in museums. Sometimes it can be found in the most unexpected places – under a bridge, in filth. Places like Burnside Skatepark convey that the most important art is built through rebellion. While the City of Portland debates demolishing the Burnside Skatepark, some might view this infrastructure planning as an oppression against free art and to erase something that exists without permission. But creativity is something that can be lost, always

BY AJ ADLER

I’m going to state right now: I’m not very religious. I don’t observe kosher. I don’t go to the synagogue. I wouldn’t even call myself Jewish most of the time. However, one holiday my family and I have always celebrated together was the Passover Seder. I have memories of my dad reading from the Haggadah and my sister and I following along. My dad would skip around so that it didn’t last until midnight (not an exaggeration), but without exception we read the story of how Moses freed the slaves from Egypt.

I’ve always considered the story of Moses to be a sort-of origin story for the Hebrews. According to the Torah, the Hebrew people have been around for much longer, however, this is the story where the Hebrews band together as a group, the ten commandments are introduced, the promise of the Promised Land is fulfilled, and God does the most for the Hebrews out of any holiday tale. (God isn’t even really around in Purim.) Needless to say, the story of Moses and Passover in general is a Big Deal in the Jewish community. Which is why it’s so important to many Jews (including me) that “The Prince of Egypt” got it right.

First, and most important, “The Prince of Egypt” is respectful to the source material. Like in any adaptation, there are differences. The original story was in many ways bare bones. The movie fleshed out the relationships and characterizations from the Torah. They also don’t censor anything. Slavery is slavery. Death is death. There’s no attempt to take it out or minimize the impact it has. The movie, from what I’ve read, is also fairly accurate about Ancient Egypt. The creators took a trip to Egypt and researched Ancient Egyptian archaeology and hieroglyphs. While many aspects of Ancient Egypt in the movie are exaggerated or altered slightly to set a tone and narrative, all of the artwork is sourced from the research the creators did. Not only does the effort show that the creators cared about making the movie right, but it also means that a lot of experts in both Judaism and Egyptology don’t have many issues with how the subject of their livelihoods is portrayed.

Second, it’s a good movie. The artwork is beautiful. It was some of the last hand-drawn artwork in an animated movie, and the effort paid off. I especially love the use of color and shading. The narrative is also gripping in a way that (forgive me God) the original wasn’t. As I mentioned, most of the

For Moses, it’s also a story about reclaiming an identity that was taken from him and reckoning with what his adopted family did to his people.

relationships are much more fleshed out than they are in the Torah. Moses’s Pharaoh brother wasn’t even named in the original. The movie instead puts their relationship at the forefront. It’s two brothers who love each other but are irreparably separated through duty. For Moses, it’s also a story about reclaiming an identity that was taken from him and reckoning with what his adopted family did to his people. All of the main characters are emotionally complex and go through character development throughout the movie. The songs are great too. They are both entertaining, set the tone, and give context to plot points in the story.

Jewish families don’t have a lot of movies they can watch during the holidays. Having this one movie that not only surpassed the stigma of being a religious movie, but is also widely accepted as one of the best adaptations of the genre is truly a miracle. This movie gracefully represents an entire community’s hope for good Jewish films. Still, if movie studios wanted to start making other top-notch Jewish movies, I wouldn’t be opposed.

I’m currently enjoying the recent resurgence of 2010’s culture and fashion, especially since it is being viewed as “nostalgia.” As someone who was a chevron-clad statement necklace wearing high schooler through the 2010’s, I see no nostalgia, but rather a more embarrassing time for my fashion tastes. However, seeing it through the lens of various social media users who are fantasizing about Coachella fits with flower crowns and dream catchers, I do feel the slightest happiness at those memories.

I’ve become completely obsessed with “Veronica Mars.” Who can resist a juicy teen drama, especially when it’s paired with a conspiracy-filled murder mystery? Not me! The fact that it also contains one of the most elite enemies-to-lovers romances in television ever certainly helps, too.

I’m currently enjoying the sunshine, semi-catching up on my reading list, season 2 of “The Valley,” and redecorating my apartment! I’m also about to start my first garden box of the spring and am so excited about all the incoming veggies and flowers.

ian drazkowski

I’m reading everything Samantha Shannon has ever written. Currently on A Day of Fallen Night–great characters. Priory of the Orange Tree was an instant fave. As for music, this time of year I always find myself listening to Sammy Rae & The Friends.

I’m enjoying the Sun and went to Seattle for Spring Break. I enjoyed the Pike Place Market and the city itself. I’m currently a part of a Healthcare Economics Research Study at PSU. When I’m not at school or work, I plan on hiking and enjoying this weather during any breaks I get. Other than that, I’m currently listening to Suki Waterhouse and Sydney Ross Mitchell.