Travel Special

On tour in Guatemala – Pattie Boyd

Villa guests from Hell – James Pembroke

Skiing for oldies – Geoffrey Wheatcroft breaks a leg African Dolce Vita – Lisa St Aubin de Terán in Mozambique

Cinema Paradiso – Bologna Film Festival by Hugh Thomson

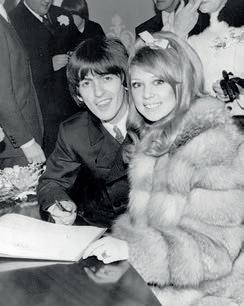

PATTIE BOYD was a well-known model in the 60s, photographed by David Bailey, Terence Donovan and many more. Cast as a schoolgirl in A Hard Day’s Night, she met and married George Harrison, whom she subsequently left to marry Eric Clapton. Today she’s married to Rod Weston and is a photographer, food podcaster and author of a memoir, Wonderful Tonight.

The Anglo-Guyanese novelist, LISA ST AUBIN DE TERÁN, used to be a perpetual traveller but now, in her dotage, she is based on the Thames. She lived in North Mozambique for 19 years and her heart is still there, invested in the community projects she runs with Teran Foundation (www.teranfoundation.org). Her new novel The Hobby is published by Amaurea.

HUGH THOMSON’s many travel books include The Green Road into the Trees about walking across England, which won the first Wainwright Prize. His new novel Viva Byron! imagines what might have happened if the poet had not died an early death in Greece – but instead went to South America with the great last love of his life, Teresa Guiccioli, to help liberate it from the Spanish.

January 2025

Cover: LMPC/Getty Images

Go Away is published by

The Oldie magazine, Moray House, 23/31 Great Titchfield Street, London W1W 7PA

Editor Charlotte Metcalf

Design Caroline Jefford

Advertising Paul Pryde, Jasper Gibbons, Monty Martin-Zakheim

For advertising enquiries, call Paul Pryde on 020 3859 7095

For editorial enquiries, call 020 7436 8801 or email editorial@theoldie.co.uk

James Pembroke – driven mad by rude friends at his Puglia villa – has five tips. Cartoons by Nick Newman

The best type of holiday?

Stay in someone’s villa, either their own or one they have rented. Not only will you save a minimum of £200 a night on hotels, but you’ll enjoy the most stress-free holiday.

Your biggest decision all day will be whether to concentrate on tanning your back or front. During your hosts’ early years of ownership, they’ll have made all the mistakes to ensure they know all the best restaurants, beaches and important cultural sites. They’ll scurry off to the shops, book restaurant tables and organise little tours, all designed to give you the truly relaxing holiday you deserve.

But there are certain things you must do in return.

1. Don’t arrive after midnight

One family recently took two and a half hours to come from the airport

half an hour away. They finally arrived at 1am to enthuse about the fun they’d had, having a drink in the local town which was ‘buzzing’. Then they asked me for a night cap.

As I was showing some other late arrivals to their bedroom, I heard the wife say loudly, ‘Don’t let him palm us off with the worst bedrooms.’

2. Do not be rude about the house and the local area

We fools who have bought abroad and have suffered at the hands of local builders and planners have partly invited you so that you can condone and applaud our absurd decision. Flattery is all we want.

So, don’t announce during dinner that you and your two small children played a game in the car called ‘How we would improve the house if it was ours’. Compliment everything, right

down to the chipped mugs and rusty shower heads.

And heap praise on the local towns, food and people. It might help if you know even a little about where you are. A guest recently asked me, ‘Are we in Southern Italy?’

Even the tiniest enquiry on the flight might have taught him that Brindisi is not parallel with Milan.

Try looking at Wikipedia for three minutes if you can’t be bothered to buy a guidebook.

3. Don’t just hang around –go out for the day

On the fifth day, the host didst tire of the guests, and they did embark on a journey to faraway places with strange-sounding names.

We all need space. It’s delightful that you ‘just love chilling out by the pool, doing nothing’, but you still

want drinks, lunch and, worse, lively conversation. As you’ve done for the last four days.

If the host is daft enough to propose leading an excursion, departing at 10am, please view that as the time to be in your car – not to make coffee or look for beach towels, books or sunglasses.

Why don’t you sluggards ever see that making your hosts and four fellow guests wait in their cars for ten minutes means they have lost 60 minutes between them, just because you were still ‘chilling’ or faffing about for those essential ten minutes between 9.50am and 10am?

And never say you’d like to go back home ten minutes after arriving at the lovingly chosen destination.

Far better to head off unescorted for just a few hours and bitch about the hosts in total freedom, as they will about you.

So we were very excited about his own grande bouffe.

4. Sort the kitty out at the start and buy the hosts dinner

There’s always a meanie in a group.

One guest suggested we each buy and cook a dinner for everyone. He was very helpful suggesting huge joints of veal and royal sea bream when it was our turn.

Out came plates of spaghetti with specs of yellow. ‘Spaghetti al limone.’

He added as a clincher, ‘It’s a Gwyneth Paltrow recipe’.

Solution: all chuck in €100 a head. And no, this doesn’t let you off taking the hosts out to dinner.

5. Don’t make loud offers to help in the kitchen –just get on with it

My least favourite question? ‘Is there anything I can do to help?’

I once replied to a Bambi-eyed 18-year-old, ‘Yes, how kind! Could you wash the salad?’ I might as well have shot her, her mother and Thumper. She fled. How could she not know that salads need making and tables laying?’ Just do something – anything.

The worst crime of all?

Suggesting a barbecue and then disappearing.

My favourite guest asked me, unprompted, where the recycling went and then drove all the bottles to the dump. My least favourite left lunch to sunbathe and then walked past us all clearing up, humming his way to his bedroom. Still, he got his comeuppance: he now edits a magazine for the elderly.

James Pembroke is the publisher of The Oldie and author of Growing Up in Restaurants: The Story of Eating Out

The words ‘guided tour’ alone can put discerning oldies off.

While we enjoy absorbing new cultures, we’ve all experienced standing around a museum or historical site, parched, exhausted and aching, as our oblivious ‘tour leader’ tells us what we already know or bombards us with details we have no hope of retaining –especially at our age.

But, if chosen with care, I am a fan of guided expeditions. I’ve just been on my fifth trip to Turkey with Somewhere Wonderful, a small company, owned and run by Jeremy Seal, respected author, broadcaster and teacher.

With archaelogist, Yunus Özdemir, Jeremy leads cultural tours of around ten guests – all likely to be of a certain age.

Jane

Jeremy and Yunus are a superb double-act; solicitous, without being patronising. They never make the less mobile of us feel the need to get a move on. They gauge immediately if we’re restless.

On this last trip, there were four lawyers, a doctor, an economist and me (a literary agent with an anthropology degree), so you could safely say we were an impatient lot.

We were not bored once. Jeremy and Yunus’s combined knowledge is second to none and they’ve been running their tours for a maximum of 12 people for the last decade.

My most recent trip was to south-east Turkey, where the three great Peoples of the Middle East –Turks, Arabs and Iranians –converge, and where the land’s ancient claimants – Kurds, Armenians and Surianis – have left their mark.

Starting in Diyarbakir, we travelled to Gaziantep via astonishing sites, including neolithic Göbekli Tepe, still being excavated but deemed to be one of the most important archaeological discoveries in human history. To put it in perspective, Göbekli Tepe was 7,000 years old when Stonehenge and the pyramids were under construction.

In the outstanding archaeological museum in Urfa, we saw some of the finest Roman mosaics I’ve ever seen, rescued from Zeugma just before being claimed forever by the waters of the dammed Euphrates.

We visited paradise gardens

conjuring up ancient Persia, and explored the covered market, the best in Turkey, renowned for its regional specialities like isot, flaked chili and fat, juicy sun-dried tomatoes.

But it’s not just what we see and learn that distinguishes these trips. It’s also their bonhomie and sense of adventurousness – good for lone travellers who might not know anyone else.

Whether we’re scrambling over ruins, in a museum, boarding a boat or enjoying a delicious dinner at an authentic local restaurant, Jeremy and Yunus are taking care of us.

We are constantly fed and watered (included in the price), except for wine, which is annoyingly expensive and not always readily available.

Yunus likes his tucker, ensuring a running feast of culinary delights: pistachios, pomegranates, soups, flatbreads topped with spiced lamb mince, smoked aubergine in yoghurt, cheeses, salads, and divine desserts like baklava and kadayif. We’ve eaten in wonderful locations, drunk fragrant coffee made from menengic berries on the banks of the Biblical

Above: on Alettin’s gulet. Bay of Fethiye

Euphrates and enjoyed delightful Turkish hospitality.

A Kurdish curator invited us to his home, where his wife, resplendent in traditional, goldembroidered velvet, cooked us chicken stew, as our lunch’s relatives pecked around us in the garden and a large, apparently fearsome but soppy dog beguiled us.

I’ve been on two gulet trips with Somewhere Wonderful. The gulet is owned and skippered by Jeremy’s pal, Alettin, and comprises seven double cabins. Again, the deal is all in, with fresh, imaginative, delicious meals cooked by Alettin’s wife. Every night, the gulet moors in a different inlet along the Lycian Coast or Turkish Riviera, from where we swim in pristine waters and make expeditions to Roman and Greek theatres or rock tombs, before shopping in coastal towns.

One winter expedition began in Istanbul, where our hotel was a delightful converted tobacco factory, and continued to Capppadocia.

With pristine snow underfoot and dazzling skies overhead, we saw the painted rock churches and an underground city hewn deep into the rock. The trip included a private and thrilling boat trip up the Bosphorus to the mouth of the Black Sea. Another trip took us to the wonderful sites of Ephesus and Aphrodisias.

It’s hard to think of any region which compares with south-east Turkey for the sheer range of culture, cuisine and things to see.

It helps that our guides evidently take such pleasure in touring a little-discovered part of the world they have made their own. I wonder where in this remarkable country – in my view a match for any (when politics, earthquakes or other disasters do not intervene) – Jeremy and Yunus will take us next.

somewherewonderful.com

Jane Conway-Gordon is a literary agent

Supermodel turned photographer Pattie Boyd found new friends in street markets and 3,000-year-old Mayan ruins

The airport in Guatemala City was full of ghoulish deities. Even the T-shirts in the airport shops were emblazoned with ghouls.

I’d arrived the day after the Day of the Dead and All Souls Day. It was also the Kite Festival. Kites were flying above cemeteries to guide spirits back to their families.

I was travelling with my husband, Rod, and two friends. Our Airbnb on the edge of town had the promising name of Casa Velvet. But it was on a noisy main road and had no provisions whatsoever – not even tea or coffee.

Our spirits rose the next day exploring Antigua, arguably Guatemala’s most beautiful city. It’s encircled by volcanoes, notably Fuego, still active and spewing smoke. The town contained beautiful colonial Spanish architecture, brightly painted building and majestic – if crumbling – churches.

The city is laid out on a grid of cobbled streets and we passed

gardens, Christian edifices and Mayan figures with masks and horns.

We came to a vast cathedral, now a preserved UNESCO site. It had suffered an earthquake and stood surrounded by vast chunks of stone that had been heaved in different directions, as if by a vast Cyclops.

It was the day after the American election. We stumbled across the Antigua Bridge Club housed in a Thai restaurant called Thai Wow, run by Gavin, an American.

A mixed bag of people of a certain age, nearly all American, had gathered for their weekly Bridge game, but all everyone wanted to do was argue about Trump’s victory.

We went on to Chichicastenango, Guatemala’s famous, colourful market town. Here trestle tables were piled high with exotic fruits, vegetables and piles of spices.

Outside the main market, vendors were selling fabrics, beaded animals and birds, hats, wooden figures and buckets of chrysanthemums and

roses. On the steps up to the church, people were cooking over open fires.

One vendor, Rosa, twinkling with humour and laughing, persuaded me to buy a beaded dragon by insisting it could be as much a gift for an enemy as for my sister, mother or friend.

We continued to Lake Atitlan, in a massive volcanic crater – certainly the largest lake I’ve ever been on. We were taken by boat to Laguna Lodge, a thatched eco-hotel on the lake’s shore. Unprepared for oldies who relish a stiff drink at the end of a day, there was but one small tin of tonic to soften our four large vodkas. So we resorted to tequila slammers. Otherwise, the hotel was paradise.

Via boat, we visited the lake’s three main villages, Santiago, St Juan and St Marco. Santiago was low key, with a few traders but no tourists.

St Juan was extraordinary, with painted buildings lining cobbled streets down to the lake, under an array of multi-coloured upside-down umbrellas.

Even the ancient cobbles were a cheerful blue, built from stones coloured by furnace slag and ballast from Spanish ships centuries ago. Craftsmen had laid the stones to allow drainage and withstand hurricanes and earthquakes.

St Juan is also known for its artefacts, like its huge painted pots. Women were dyeing, spinning and weaving cotton to make beautiful fabrics and we bought some exquisite handmade scarves. We went on to St Marco to meet Tim, a friend of my nephew and a Guatemalan resident, who roasts coffee beans and sells them to local shops.

From here, we took a short flight to Flores, the starting point for visiting the spectacular worldfamous Mayan site, Tikal.

On the small bus into the jungle to see the ruins, I sat next to a smiling elderly couple of Mayan descent. Though we had no common language, they were happy for me to photograph them. Tikal, deep in the jungle and once the heart of Mayan civilisation, was occupied as far back as 1,000 BC. Most of the construction of its

monumental structures took place between 400 and 300 BC.

The extraordinary city of Tikal was discovered in 1848 and today comprises around 3,000 structures, some astonishingly still intact. In recent years, lodges have been built around the site to accommodate tourists. We stayed in a lodge with

bungalows scattered through landscaped grounds.

It was so deep in the jungle that electricity was still rationed. Power is switched off at 10pm, making oldies’ nightly visit to the bathroom fairly treacherous.

Leaving Flores for Belize was a rather desolate experience. Vehicles are not allowed to cross the border.

So we said goodbye to our car and driver, gathered up our luggage and walked across a short stretch of no man’s land feeling like refugees.

As we continued our journey on through Belize and Mexico, I reflected on what a friendly country Guatemala was – and so rich in culture, history and beauty.

While its world-renowned sites, like Tikal, are attracting more and more tourists, the country still feels somewhat undiscovered. And the towns, though learning to accommodate visitors, continue to feel authentic.

Go now before all that starts inevitably to fade.

Sixties supermodel Pattie Boyd is a photographer and author of a new memoir, Wonderful Tonight

I don’t care what you say. I love Eurostar. I blooming well love it. It’s a wonder of the modern age and –almost always – a joy to travel on.

That’s not to say Eurostar doesn’t wind its passengers up just as much as any cheap, crappy airline does.

Don’t get me started on my seven-hour delay to Rotterdam a month or so ago.

Don’t get me going on Eurostar’s maddening, tone-deaf, bloodyminded refusal to resume services post-Covid from Ashford International. Ashford International?! Was any station less appropriately named?

When it works, though, Eurostar is bliss, and I forgive it everything.

Just think about it: you can get to Amsterdam, Brussels, Paris and Rotterdam direct, in no time, and all manner of other places – such as the ABCD of Antwerp, Bruges, Cologne or Dusseldorf – with just one change.

Thanks to Eurostar, Europe is most

definitely our oyster, be it for a week, a weekend or just for the day. Check-in is easy (well, sort of, more of that later). Time spent hanging around is minimal. There’s no nonsense at security about not being able to take liquids on board. The staff are multi-lingual and helpful. The trains are spotless.

There’s a well-stocked café on board and the loos work. You’re guaranteed a (very comfortable) seat. You walk straight out into the heart of whatever city you arrive in.

Unlike travelling by air, you’re not herded hither and thither like sheep and constantly kept queueing by people who despise you. Stress levels remain resolutely rooted at zero and, usually, Eurostar makes travel a relaxed pleasure, just as it should be.

And you don’t even need to go far to enjoy the benefit. Get off at the first stop, Lille, I say – yes, Lille. Don’t laugh. It’s a wonderful town. And you can have an absolute blast for peanuts, with one-way tickets starting at £38.

It takes just 87 minutes from London St Pancras International to Lille, which is only six minutes longer than it takes me to get from Brighton to St P. Only the other day, it took me exactly four hours from shutting my front door in Skid Row-on-Sea to walking into Room 101 at Grand Hotel Bellevue, Rue Jean Roisin.

Four hours, during which I had a coffee, a very tasty lunch, read the papers, sent some emails, stared out the window at northern France passing by at 185 mph and, well, simply daydreamed.

They recommend you check in an hour before departure. On a quiet day, it’s possible to cut it much finer, with the gate shutting just 15 minutes before the off.

Having had my trip pimped up to Eurostar Premier (£208 one-way), I got there in good time, determined to make the most of their swanky lounge.

Being a complete technophobe and travelling alone, without the through-gritted-teeth good offices of Mrs Ray, I couldn’t for the life of me work out how to get the tickets off my email and into the wallet (whatever that is) of my phone, so that I might scan them at the gate.

Casting feebly around for help, I found a kindly Eurostar lady who laughed when I told her that I was the most stupid person she was

likely to meet all day. Having tried and failed to get me to grasp the complexities of my phone, its settings and the beauty of QR codes (uh?), she quickly agreed that, yes, I was the most stupid person she was likely to meet all day.

She said it nicely, though, and finally conceded that it would be simpler if she just went away and printed a paper ticket.

Whizzing through security and British and French passport controls, I made straight for the lounge. What I found was more a corridor with chairs than an actual lounge and it was already packed with passengers without much to offer us. It had few pastries, a too-complicated coffee machine and a stack of freebie magazines and that was about it.

My tip is to head upstairs where the chairs are both more plentiful and more comfortable, with the added benefit of a juice bar which, apparently, turns into a cocktail bar later in the day.

Eurostar has recently revamped its food and drink offering, overseen by Michelin-starred chef Jérémy Chan, pastry chef Jessica Préalpato and much lauded sommelier, Honey Spencer.

Lunch on board, served soon after departure, was heralded by a very welcome glass of Champagne Fleury Rosé Brut NV with regular top-ups.

The meal itself comprised of a minuscule and rather dreary starter of potato salad with green goddess dressing; an excellent (but, again, tiny) plate of oxtail ragu, horseradish mash and mushrooms; a nugget of decent cheddar with quince jam and some sort of yoghurt and lemon pudding which didn’t grab me.

Although hardly a shirt-popping feast, it filled a gap and was much enjoyed, comparing favourably with anything you’d get at 35,000ft.

We arrived bang on time at 13.27 and, a gentle 15-minute stroll later, I was checking in at Grand Hotel Bellevue, overlooking the very handsome Place du Général-deGaulle, known more usually as La Grand’Place.

It’s a decent spot – quite trad and old-fashioned. I was just thinking how nice it would be with a bit of a refurb when I discovered it had just had one. Heck, I’m only nitpicking.

It’s in a perfect location and boasts a cool cocktail bar on the roof, Le Toit-Terrasse, with a fine cityscape view and tempting cocktails. My pick of the pops is the Fever, a toothsome blend of Santa Teresa Rum, ginger syrup, fresh lime juice and sugar.

Lille has a complicated history. It has been, at different times, part of the Holy Roman Empire, the Burgundian State and Habsburg Spain. It has been occupied by the Dutch and the Germans and besieged by the Austrians.

As a result, the architecture is a bit all over the place, from the glorious Spanish Vieille Bourse to the Flemish Old Town, Belle Époque Opéra de Lille and the Art Deco L’Huitrière, Louis Vuitton shop. And, crikey, there’s so much to do. In little over 24 hours, I managed to take in a cracking performance of Die Fledermaus in the jaw-droppingly exquisite gem that is the Opéra de Lille.

I visited the beautifully curated birthplace/museum of Charles de Gaulle. I spent an hour or so in the gorgeous Palais des Beaux-Arts de Lille, the largest art gallery in France after the Louvre.

I gawped inside the striking Lille Cathedral. I devoured a plate of oysters in La Chicorée and another in L’Atelier Iodé. I had two absolutely belting meals in shabby-chic La Petite Cour and the shiny modern NU Restaurant, just yards from Lille Europe Station.

I had a hoot and, in less than three hours after leaving NU, I was back in London having a 4pm cuppa with a chum.

Jonathan Ray is Drinks Editor at The Spectator and the author of numerous books on wine

We grumble about our railways, believing that the Golden Age of rail travel is long behind us.

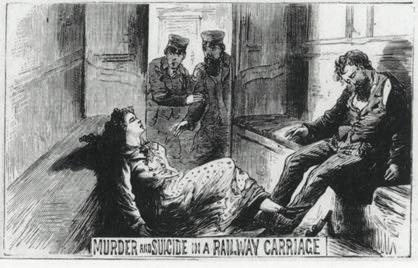

Despite strikes, delays, cancellations and a general slump in the standard of service, it’s worth remembering that, even in the late 20th century, closed compartments, without access to corridors, gave passengers, especially lone travellers, justifiable anxiety – as the extract, below, from Simon Bradley’s book demonstrates.

On 21 September 1871, passengers in a second-class carriage of a Lancashire & Yorkshire Railway train between Wigan and Liverpool overheard an argument in an adjacent compartment, followed by some loud bangs.

When the train stopped at Kirby, the guard and a porter opened the door of the compartment, which had its windows closed and was full of gun smoke. Inside were the bodies of Robert Wanless, a 31-year-old colliery overseer, and his estranged wife, Anne. She had been shot several times by her husband, who had then turned the pistol on himself.

Britain’s first murder of a passenger on a moving train occurred seven years before, on a London suburban train. The victim was a wealthy banker, the killer a young tailor desperate for money.

Suddenly, the humdrum railway compartment presented itself to the public mind as a space of potentially fatal encounters.

The murderer’s subsequent escape to the New World, followed by his capture, trial and public execution, all contributed to make the story one of the sensations of the day.

The Wanless case, the second recorded instance of murder on a British train, created only a modest stir by comparison. The inquest heard that the male subject was a heavy drinker with a jealous nature and a record of threatening violence.

With no suspect on the loose and no mystery about the course of events, the press could find little with which to amplify the marital tragedy.

The trashy Illustrated Police News did its best, placing on its front page an imagined view (pictured above) from within the fatal compartment at the moment the door was opened. Anne Wanless is falsely depicted with her face exposed rather than concealed by the veil of her bonnet, as witnesses described.

One of the passengers was asked at the inquest whether he had tried to communicate with the guard after hearing the suspected gunshots. He replied that he had no means of doing so.

When the jury’s verdict came, it included the recommendation that ‘there ought to be a means of communication between passengers and guards in all trains.’

The issue of internal communication when a train was on the move was a well-worn one by 1871. With braking under the control of driver and guard, the solution required every compartment to be equipped with some apparatus for raising the alarm, so that the train might be stopped for investigation.

Several different systems had been tried by that time, one of which was recommended by the Board of Trade in 1868.

The main problem – an all too familiar one with the various systems – was that its combination of a tuggable rope linked to a bell (for the guard) and gong (for the driver) didn’t work very well. In 1873, the Board quietly dropped its endorsement.

Other systems involved push-buttons linked to an electric bell, and a cord below the carriage floor, reached through a hole between the seats. There was even a proposal for an iron speakingtube running the length of the train, with flexible rubber links between the carriages.

Resolution finally came after the Armagh disaster. It prompted the authorities to demand that continuous automatic brakes be provided on all passenger trains across Britain and Ireland.

Rather than communicating an alarm signal to the driver or guard, the cord could now be made to activate the braking system directly instead. Yet the phrase ‘communication cord’ still lingered in use, an echo of the unsatisfactory systems developed in the 1860s and 1870s.

Bradley’s Railway Guide (left), published by Profile Books (£30), is out now

Glamping? Ugh! Give me a tent and a smelly old sleeping bag any day, says Sam Leith

At home, I sleep swathed in a thick duvet aboard a deep pocket-sprung mattress and rest my weary head on the most luxurious pillows John Lewis has to offer. My linen has a high thread count and smells of White Company Christmas presents.

And, reader, I toss and turn every night like Lady Macbeth.

But put me in a tent in one of those old sleeping bags that smell a bit of hamsters, with nothing between me and the pebbly slope on which my tent is pitched but a half-deflated roll mat and my head on a rolled-up pair of jeans, and I sleep the sleep of the just.

You can keep your six-star slave-built Gulf hotels with their acreage of fluffy towels, white beaches and swim-up bars in azure lagoons. Keep your Mediterranean cruises and your Tuscan villas. It’s a camping holiday for me, every time.

Glamping – of the sort which has enjoyed a huge boom in this country over the last couple of decades – is something I greet with a little suspicion. I, too, can see the attraction of a good solid yurt with a blow heater, a proper bed and duvet and a set of USB ports from which you can charge your phone and run the inevitable fairy lights.

But it’s not exactly camping, is it? Not camping like I have been doing it and you, reader, have been doing it since the 1970s. Not camping as described in Emma Kennedy’s likeable memoir, The Tent, The Bucket and Me. Not camping as Barbara Windsor and Sid James would recognise it, or as my children – who have spent hours playing ‘it’ in confederation with an ad-hoc gang of children on a campsite, or amused themselves decorating pebbles with felt-tip pens – would recognise it.

For me, austerity is part of the

appeal. The point of camping, in my view, is not to pretend you’re in a hotel. Camping should be cheap.

You should travel light. For happiness, you do not want a portable kitchen, a gazebo, a rack of chef’s knives, a fancy four-ring stove with overhead grill, adjustable table and set of six folding dining chairs, inflatable double-mattress with duvet and all that malarkey.

You don’t want – and, for God’s sake, you can find these in camping shops – collapsible kitchen cupboards. Simplicity is the thing. A one-pot dish – a bean chilli, or a potato-and-pea curry, say – tastes the more ambrosial for having been cooked squatting on your hunkers beside a single blue tin of camping gas in a fold-out stand.

I’m no Luddite, though. I embrace, as we all should, the miraculous new technologies of the pop-up tent, or of the six-man which a single person can carry.

The tents that we grew up with were nearly impossible to put up (all those clanking aluminium poles, those fly-sheets and buttons). They were so heavy that you needed at least one more person to carry a tent of any given size than it could accommodate. And remember how, if the flysheet so much as brushed the inner tent, frigid water would cascade into your sleeping area?

Tents are not only more waterproof than they used to be, but they are cheaper. You need only visit a big branch of Cotswold Camping or Black’s to have your faith in human progress restored. These days, you can stroll into the wilderness with your accommodation for the night in one hand, weighing little more than an umbrella. Freedom!

My hunch is that, even though it’s nicer to camp in the warm south, it’s

Northern Europeans who take the most pleasure in camping. We are still half in love with the austerities of the Reformation – and we show it by spending our leisure time making it harder to be comfortable than we do our working weeks. The compromise we make with the counterReformation is to go to the warm south, now and again, to do it.

For the last decade, my family and I have spent two or three weeks every summer in a blissful little campsite by a burbling river in the Cevennes. I won’t name it, because then you’ll all turn up and ruin it.

There’s nothing to do but read, swim and potter into Florac for an ice-cream, your days given rhythm by buying bread, preparing and washing up your meals, and the passage of the sun across the sky.

When it rains – which won’t usually happen more than once a fortnight – it gets on with it. There will be an astonishing, terrifying, apocalyptic thunderclap from what

seems to be a blue sky. A few fat drops will fall. Then, for an hour or two, the campsite is Bangladesh in the monsoon. Camping stoves, deckchairs, unattended children – all are swept into the river. But then, bang, the sun comes out again and within an hour everything is bone-dry and it’s as if it has never happened. When the weather is against you in England or (shudder) in Scotland, you have a problem. You’re damp. You’re cold. The tent fills with mud. The tent’s damp. The tent’s cold. You wriggle into your sleeping bag. Your sleeping bag is damp. Your sleeping bag is cold. The drizzle continues. Patches of the campsite become Passchendaele, and stay that way. Your wife books herself into a hotel. Depending on how you’ve performed over the previous 24 hours, she may or may not let you accompany her. And yet adversity is what bonds us. On a jolly kids-and-parents weekend with other parents from school, I forged unbreakable

Keep your Mediterranean cruises and Tuscan villas. It’s a camping holiday for me, every time

alliances with the other dads attempting to barbecue frankfurters in a storm, while rainwater poured off the hoods of our macs.

I’ve helped my wife dry out our nephew’s tent in a muddy field after his half-open water bottle fell over at 3am. I’ve bailed out of a field in the small hours of the morning after a posse of angry farmers in LandRover Defenders, lamping for rabbits, have woken us with roaring engines and full-beam headlights. Stuck in my tent in an Isle of

Wight downpour, I’ve peed into an empty prosecco bottle at a music festival. This is the stuff of which memories are made.

And, just sometimes, there’s a gap in the rain. Sleeping under canvas not only connects us to our hunting fathers, way back in human history. It can produce moments of peace and beauty like nothing else.

You spend the middle of the day watching beams of sun lancing across a forest clearing redolent of the smell of pine and mulch.

You drowse before sleep, sitting on a log with a glass of red wine, staring into the still glowing embers of a campfire. Or you step out of your tent at dawn onto a meadow glittering with dew, unroll your pillow and pull it onto your legs. And bliss it is, in that dawn, to be alive.

Sam Leith is literary editor of The Spectator and author of The Haunted Wood: A History of Childhood Reading

In November 1979, probably because of my fragile position as a director in the emerging Australian film industry, I was asked if I was interested in a ‘cultural’ visit to Russia. I was accompanied by an Australian actor and an official from Canberra, both of whom expressed enthusiasm for the Russian system of government.

Moscow was freezing. We were met at the shabby airport – which I’m sure has now been redesigned to international standards – by a middle-aged, chain-smoking official, who looked quite like Mr Khrushchev, and a young driver who resembled Rudolf Nureyev.

We were taken to a huge hotel, the Odessa, where, despite an apparent absence of guests, we were told two of us had to share a room. We tossed a coin and I shared a spartan room with the actor.

The following morning, I woke early with jet lag and decided to go for a walk.

Despite some voluble but

incomprehensible protests from a uniformed guard, I went out into the city. It was a cold, bright morning as I walked through the empty streets down to the river.

Returning after an hour or so, the hotel was in chaos. I was surrounded by a group of men and quizzed, in English, by the Khrushchev lookalike.

‘Where did I go?’ ‘Who did you meet?’ and so on.

They all seemed to realise eventually that nothing sinister was involved and the group drifted away.

The Khrushchev clone lit yet another cigarette. I commented that he was a heavy smoker and that smoking was bad for his lungs. ‘Who told you that?’ he replied, clearly doubting the validity of the information.

A tour around Moscow with two young female English-speaking guides was fascinating. There were remarkably few pedestrians, although there didn’t seem to be any stores or shops that would attract clients. Even the massive Victorian GUM department store sold only badges of Lenin and Stalin.

Oddly, despite the intense cold, ice-cream sellers (with only one flavour – vanilla) were on a few streets and, more oddly, there were a number of men dispensing glasses of champagne from small wagons that resembled hot dog stalls.

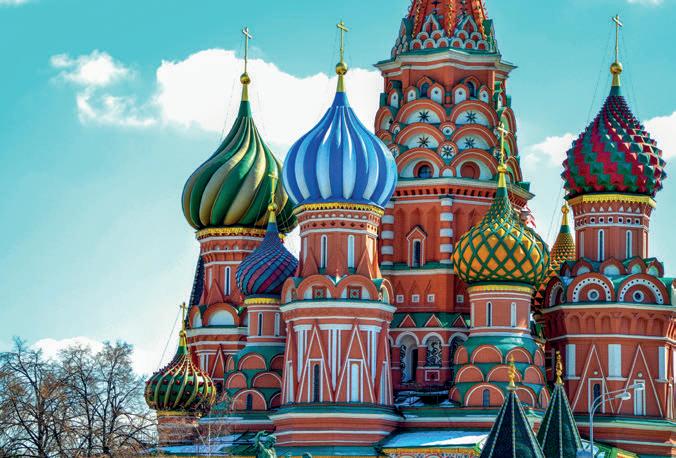

We saw the Kremlin and the extraordinary St Basil’s Cathedral (pictured above), though were not allowed inside either. I was told that Stalin issued orders for this bizarre, colourful 16th-century church to be

demolished, but that bureaucrats had managed to find excuses to delay the destruction – until finally Stalin’s death presented a reprieve.

On our first night at the hotel, I was handed an immense menu in the sparsely populated dining room. I hungrily flicked through the pages and ordered. The waiter carefully wrote down my order then said in guttural movie-Russian English, ‘We haff not got zeez things’.

Further, they had no ‘things’ at all. I had to settle for a glass of kvass – an unappealing drink, which I believe was made from bread and sugar.

The next morning, when there was nothing for breakfast, I somehow managed a call to the Australian Consulate. They didn’t seem surprised to hear from me. I was invited to dinner the next night.

The Consulate was in a magnificent old house that had belonged to a theatrical producer prior to the revolution. I asked the Consul why there was no food in the hotel and where did he get hold of the impressive meal we were demolishing?

He replied that he had no idea why the Moscow hotels were short of food but – perhaps – there was a transport problem. The Consulate brought their food in from Finland.

A few nights later, with the young lady interpreter, I attended a production of Aida in a vast theatre.

The audience seemed to consist largely of North Korean military personnel. Just before the interval, the interpreter nudged me and whispered, ‘Follow me, no matter where I go’.

The lights came on shortly after this command. The interpreter leapt from her seat and ran up the wide aisle toward the lobby. I followed her as she dashed through the lobby and up two flights of an elaborate staircase.

At the top, she rushed to a set of huge double doors and pushed them open. I followed her into a vast room on which tables were laden with masses of caviar and all kinds of delicacies. By the time the Korean army arrived, both of us had dined.

A couple of days later, it was announced we would not be flying to St Petersburg, as promised, but to Odessa, in Ukraine. No explanation for the change was offered. I was fascinated to realise that our bizarre Russian experiences did not dim

enthusiasm for the Communist political system by my two Australian travelling companions.

The two-hour flight to Odessa was in an old plane with canvas seats. The other passengers were all uniformed soldiers. There was no in-flight service but the interpreter thoughtfully brought some biscuits and water. She read Pravda during the flight. I pointed to some headlines and asked what the news items were. All were reports of official speeches. I asked about news of everyday life and naively suggested, ‘Traffic accidents, robberies, murders and so on’.

The girl was shocked: ‘Who would want to read about such things? Who would want to read bad news?’

Odessa was an attractive if rather decrepit city. Many grand but derelict

I was surrounded, and quizzed by a Khrushchev lookalike

houses were strung along the seafront. As we stood at the top of the Potemkin Stairs (pictured), famous for starring in Battleship Potemkin (1925), an elderly couple approached me and asked, in English, which country I had come from.

Before I could reply, they were curtly chased away by the Khrushchev lookalike.

The highlight of my Russian visit was a production of Don Giovanni in Odessa’s magnificent 19th-century

opera house. The packed audience, clearly all local residents, were captivated by the music and singing, and rewarded the cast with fervent applause and yells of delight.

In my Odessa hotel, not a shared room, I woke up in the middle of the night to find one of the young interpreters sitting on the end of my bed. ‘You are a nice boy, Bruce,’ she said. I thanked her but suggested she return to her own room. She stood up quietly and left.

Just before leaving Moscow for Sydney, I told the interpreters I would send them a postcard from Australia. Both became agitated and said this was not to be done as it would cause problems for them.

Problems? A postcard of Sydney Harbour? Those young women, like me, would now be in their 80s. They would have seen a lot of changes in Russia in the past 40 years –culminating in the tragedy of the invasion of Ukraine.

Bruce Beresford directed the Oscar-winning film Driving Miss Daisy (1989)

Lisa St Aubin de Terán tried – and failed – to bring tourism to her home on a virgin beach in Mossuril

I grew up in London as a mixed-race child with a nagging curiosity about my African roots.

At 40, I promised myself that at 50 I’d go to Mali and set up a chain of libraries (a win-win situation, as most of the books would get stolen but still circulate widely).

But then I fell in love with Mees van Deth, who’d chucked in filming to pioneer luxury tourism on a virgin beach opposite the 1,000-year-old Mozambique Island. I ditched my Mali plan and became his groupie.

After camping for months on the lagoon’s edge, feasting on lobster, staring at the Indian Ocean while lolling on powdery sand, I woke up one day, like a restless Happy Valley dweller, to ‘another f**king day in Paradise’. I had to find something to do, especially as I tend to wake up at 4am, write for a couple of hours and then have the whole day free.

Mossuril District is 1,300 square miles and had no secondary school, 98% unemployment with 85% of its 110,000 souls under 25. A library was out. Sixteen years of civil war had destroyed a lot of infrastructure.

Nearby Cabaceira was full of lovely, friendly Makua people, with grinding poverty and bad diets lurking behind their smiles.

We leased a magnificent but ruined Portuguese Naval Academy to convert into the training college. Some 47 villagers rebuilt it, while a second team tackled termite hills, the giant Ficus growing out of the ballroom’s walls, and a yellow acacia rooted in the well.

A bigger problem was the spitting cobras and tiny, deadly coral snakes in the historic rubble. No one was bitten, but we lost days as everyone took off screaming each time anything remotely like a snake was spotted. Once scattered, the work force rarely returned before lunch.

They always materialised as our cooks heaped more than 100 plastic plates with mealy-maize, fish and beans. Despite only having 67 workers, dozens of extras always joined the queue.

Meanwhile, Mees and I lived in a safari tent, adding a palm-thatched sitting room with furniture lugged in from Nampula in our trusty Land Rover. I found hundreds of hand-cut limestone blocks stashed under a Baobab and made a mosaic floor.

long green serpent slithered along the thatch directly above her. It dangled in graceful curves, swaying slightly each time she tossed her lacquered hair.

Her husband spotted it and started gurgling so wildly that, embarrassed, she cut their visit short.

When the college was restored, Mees and I moved into the ballroom with two tiny bush babies. At night, they leapt and wailed and hid by day inside places like my handbag, Mees’s hat and the printer.

We shared our splendid room with Al Pacino, a severely maladjusted orange baboon I’d bottle-fed since he was about three days old. Pacino (with a striking resemblance to the star) required round-the-clock nursing. He lived strapped onto my hip until he became too heavy and was relegated to my left foot.

So, given the area’s enormous tourism potential, and with Mees already setting up his lodge, we decided to start a community college of tourism.

There are loads of magic wands out here – our village chief’s is made from a lion’s tail. But you can’t wave one to cut through gruelling Portuguese red tape. Months of bureaucracy, kowtowing and schlepping 160 miles to Nampula city followed.

As Mees developed Coral Lodge, we set up Terán Foundation, a charity to help the local community help itself. We were the only foreigners, apart from Falcão. A former Portuguese mercenary, he settled in nearby Chocas-Mar where, when sober enough, he ran a little bar. Word spread and visitors started arriving at our make-shift home. A Dutch engineer arrived with his dainty wife, who descibed her snakephobia while a

We also shared our room with Al Pacino, a severely maladjusted orange baboon

Pacino screamed hysterically whenever I left him. So we went around like conjoined twins for his first five months. But he was so jealous and possessive that we built him a pergola to live in before he killed any of the staff or students he’d started biting.

From May 2005, my youngest daughter, Lolly, headed a team of 15 international volunteers and six teachers to help teach 53 villagers about tourism, hygiene and the 3 Rs. The hardest thing for the students to grasp was what tourism actually was.

‘So no one is forcing them or chasing them, but people actually choose to go and sleep in a strange place surrounded by strangers and pay for that?’

‘Why? What is wrong with them?’

‘Don’t they have witch doctors in their villages?’

And the students found the idea of peeing or doing a ‘major necessity’ inside a house disgusting. They explained:

‘When Charifo, Lord of our ancestors, provides endless beaches, why sully your own home?

‘Not even animals do that! And you want us to don those rubber

things and stick our hand in and clean it!’’

Leading by example, I cleaned countless loos. Dozens of our former students still find it gross, but they humoured me.

By 2010, 150 locals had tourism diplomas and another 80 had graduated from our agricultural faculty, which we started because you could have died of scurvy, such was the lack of fresh vegetables.

Coral Lodge opened and a few hotels followed. But I felt like Monty Python’s sergeant major marching up and down the square alone, as the rush of like-minded investors we’d envisaged failed to arrive. Tourism simply didn’t take off as we’d hoped.

Many of our graduates left the village to find work – even though they have a horror of leaving home.

We closed the college but kept Sunset Boulevard, a training restaurant and backpackers’ pension

in the district capital. Over the years, 200 volunteers have ventured out to help us. My son, Alex, and eldest daughter, Iseult, have dropped their anchors in Mozambique.

My half-sister’s DNA shows that she is 26% Mozambican. Every time I walk down the Ramp of Slaves to catch the local dhow ferry, I imagine our ancestor being dragged down the same ramp in chains to be sold into slavery. Maybe that’s why I feel so bound to Mossuril.

Or maybe it’s because of my lovely garden that rolls down to the beach. Or being surrounded by people who love life, look out for each other and whose poverty has, coincidentally, made this one of the few unpolluted places on the planet.

With hindsight, I see that our College of Tourism gave local youths more of a sense of self-esteem and filled in gaps in their basic education rather than any actual tourism-

training. Besides, only working hands-on in the hospitality sector really leads to the silver service we aimed for.

Yet, today, in a place with virgin beaches and up to 90% unemployment, tourism is slowly but surely taking off. There are 500 new holiday homes in Chocas-Mar and about a dozen new B&B’s.

A crowded beach full of deckchairs and sunshades isn’t my idea of paradise, but it can put a lot of food on plates.

And, as a visitor, albeit a longterm one, I don’t feel it’s for me to decide the shape of things to come.

www.teranfoundation.org

Lisa St Aubin de Terán’s latest novel is The Hobby

Paul Canham and his wife have been on more Oldie tours than anyone else. He adores his seasoned travel companions

Lunching outdoors with a group of oldie travellers at Villa Cetinale on a cloudless November day, I found myself musing upon what it is about Oldie trips that brings me and my wife Dawn back time after time.

We’ve just done our 50th trip in little over a decade – record-holders.

In 2012, I first mooted an Oldie trip to Dawn: ‘The good news is I have booked a holiday, a wine tasting trip to Burgundy. The bad news, it’s with The Oldie – so we will probably be with a bunch of crusties.’ How wrong I was. Some we met became, – and remain – good friends.

The trip did get off to a somewhat inauspicious start. A ten-hour coach trip from central London to La Maison du Chateau in Cry, with lunch in Calais, turned into a 14-hour marathon, with two brief comfort breaks. The 18 unhappy travellers were still waiting aboard our coach at Folkestone when we should have been departing Calais.

Eventually arriving at Cry at 10.30pm, Dawn started plating up the buffet left out for us: Quiche Lorraine, a dressed salad, and tarte tatin to follow. A tired and irritable group of strangers tucked in.

Minutes passed, and someone piped up, ‘This quiche tastes a bit odd.’ The quiche was rhubarb tart, the tarte tatin a caramelised onion tart! The ice was broken.

A week of wonderful visits, meals and wine tastings later, the return schedule having been suitably amended, we enjoyed a night in Rheims with champagne tasting followed by an eat-what-you-like dinner. The next day, following lunch at the restaurant in Calais which we’d missed on our outward journey, we arrived in London at 6pm.

In the early years, the accommodation and dining experience were occasionally hit and miss. But the company and places visited were invariably excellent.

They were made memorable by the occasional tendency of an oldie traveller to go off-piste. In Lecce, following a visit to the cathedral, one

traveller stayed on for Mass without telling anyone. In Paris, en route to Tours, another got lost at Gare du Nord, causing all of us to miss our connecting train from Gare Montparnasse. The Oldie sorted things out excellently.

In Vienna, after a rather too good evening out, someone forgot their room number in our apart-hotel. Only after 30 minutes of watching me try various floors and rather too many doors for comfort, did they finally recall where it was.

The oldies are occasionally forgetful, but always of independent mind and can-do spirit. So ‘herding cats’ often comes to mind when they are free to roam.

Of course, today anyone can visit pretty much anywhere independently. But to do it on an Oldie holiday, with like-minded travellers, offers an opportunity to get below the surface, to visit places and meet people independent travellers would be hard-pressed to find.

We’ve been to the Baron Six

They can be forgetful, but always have a can-do spirit

collection in Amsterdam. We came face to face with Doubting Thomas’s digit in a reliquary in Santa Croce in Rome. There were canapés in Palestrina with Prince Barberini.

There was the unexpected delight of Pol Roger Winston Churchill Reserve 1997 at Chateau Langoa Barton, provided by Eva Barton – all thanks to our fellow traveller Serena Soames knowing the family.

Having a Spanish sister-in-law, I was delighted last year when Oldie publisher, James Pembroke, asked us to curate an Oldie trip to central Spain. James bravely agreed to let it be to a less travelled part of Spain, Extremadura, a poor and primarily rural region, home to the Dehesa (think cork oaks and Pata Negra pigs). It was our 40th trip and our 40th wedding anniversary.

It was at the time of the King’s Coronation. Thanks to the influence of our sister-in-law’s family, we were able to take-over a small bar-restaurant in Guadalupe where we all watched the Coronation, followed by lunch.

I am often asked which is my favourite trip. I honestly cannot say. So many have had memorable moments and allowed us to meet people with wonderful stories.

We will always remember Peter Cobb, who captained the UK’s first Nuclear Submarinem HMS Dreadnought. He was so quiet and unassuming that I had to drag from him the story of how he held the record for the fastest underwater crossing from Rosyth to Singapore.

Occasionally a sense of entitlement leads some to treat Oldie staff as servants and fellow travellers with disdain.

But they are rare. Most are kind, excellent companions for a week of delicious food and wine, and expertly curated tours.

Oldie editor, Harry Mount, once said, ‘Oldies are travellers, not tourists.’ I will drink to that.

Sign up for one of our trips on theoldie.co.uk/courses-tours

Even though most oldies have spent half their lives without them, it becomes increasingly difficult remembering how we coped before mobiles.

Today we rely on them when late, lost, stranded or in similar stressful situations. Yet it was precisely the lack of that instant fix that could lead to extraordinary adventures and certainly honed our now dwindling capacity for initiative.

In the late 90s, I made documentaries in Africa. Early one morning, I’d flown into Uganda’s capital, Kampala, to make a BBC film in Kapchorwa, a remote northern region. After a long day procuring permits, booking transport and making arrangements, I set out with Okulu, a local driver, to pick my Zimbabwean crew from Entebbe airport. He’d been briefed by Philip, his boss – so I sank into my seat and quickly dozed off.

I wake with a jolt. We are driving along an empty country road. I look at my watch. We should have been at Entebbe half an hour ago.

‘Where’s the airport?’ I ask.

Okulu nods, smiling broadly. I repeat myself slowly. He still doesn’t understand.

‘Airport?’ I repeat, panic rising. ‘Airport!’

‘Ah, airport!’ he laughs, relieved. ‘It is very far.’

‘How far?’

‘Oh, very, very far.’

‘Stop the car,’ I shout.

Okulu doesn’t understand immediately, but when he does, he brakes so suddenly that we both lurch forward. There is a noise of metal rattling.

‘Okulu, where exactly are we going?’

Philip had not made him understand that we were to pick up the crew. We are well on the way to Kapchorwa, now two hours the wrong side of Kampala.

‘Turn round fast,’ I yell.

Okulu switches on the engine. It sputters and dies. Fifteen minutes later Okulu ventures out from under the bonnet with two chunky bits of oily metal. Night is falling fast, thick as a blanket. We need a telephone, a town. He doesn’t understand. I wave my arms and yell, ‘Town! Town!’ Anything is better than being here in the middle of nowhere.

We push the brute of the vehicle to the side of the road and I heave my luggage out of the back seat. A white woman lugging her bags along this rural road is a rare sight and so the first pick-up that passes stops immediately. Okulu and I climb up into the back among sacks of maize with six farmworkers who stare at me with friendly curiosity.

We reach a scruffy little town, where we

When Charlotte Metcalf ’s car broke down in pre-mobile Africa, she depended on the kindness of strangers

trawl busy streets full of kiosks selling everything from soap, biscuits and Fanta to sewing machines and car parts. Oil lamps flicker. One vendor knows a mechanic; another fetches a pick-up truck. Focusing on the car, we fail to find a telephone. Three men armed with spanners and rags arrive. We climb into the commandeered pick-up and return to the broken car.

We bowl along in companionable silence under an inky sky, the breeze whipping my hair, which makes the mechanics giggle sympathetically. I feel a surge of gratitude towards these strangers. Would people in England ever be this generous and helpful?

We reach the car and the men set to work. After half an hour, there’s a pile of twisted metal on the road. Hopeless. By now I am demented. What if my crew leaves the airport to look for me? They have no way of getting hold of me. We drive back to the town and finally find the only public telephone. It needs a card. A man in the queue offers one for a wedge of dollars that he counts agonisingly slowly. At around $50, this is one of the most expensive calls I’ll ever make.

I’m alone in the middle of nowhere with my luggage.

Yet I feel safe; even content

I connect to the car hire company but a woman informs me Philip has just left. I beg her to run after him. She succumbs to my desperate entreaties with an irritable sigh. I wait, worried that the card will run out of credit.

Then I hear footsteps and Philip is on the line, calm and helpful. He was on his way home but offers to drive straight to the airport instead. I hand the phone to Okulu, so Philip can tell him what to do next but Okulu hangs up before I know what’s been arranged. I dial back but now the lines to Kampala are busy.

There’s nothing for it but to follow Okulu. We pick up my bags again and trudge to a garage on the edge of town. It’s shut for the night. Okulu signals me to stay. There’s nowhere to sit. So I resign myself to standing in the dark forecourt for the next few hours.

Okulu leaves in search of a towtruck and then I’m alone in the middle of nowhere with my luggage. Yet I feel

safe; even content. There’s nothing to do except admire the stars. It’s really quite relaxing.

A few cars drive by and slow down, surprised to see me alone in the dark. Word filters round and soon cars drive into the forecourt to look at me. One, full of men, stops.

‘Are you alright?’ asks the driver, eyeing me quizzically.

‘Oh yes, I’m having a wonderful time,’ I answer.

He grins broadly at my sarcasm. ‘Do you need help?’

‘No, I’m waiting for people.’

‘Here? In the dark?’

I shrug and grin like a lunatic as the men laugh uproariously.

‘Well, if you’re sure you’re OK,’ he says doubtfully and drives off.

Minutes later, he returns. ‘Are you certain you don’t need help? Water? Food?’ His face is kind, concerned. ‘I can drop you somewhere?’

I am glad it’s here we’ve broken down. I’d have been far more anxious in other parts of Africa; certainly in England. We have a bit of cheerful banter and the men leave, promising to come back and check on me.

Eventually Okulu arrives with a tow-truck and the car. In the car is the food I’d bought earlier which we spread out on the bonnet and devour. Okulu then stretches out on the car’s back seat, his legs outside of the open door. He snores mightily. I walk to where I can see the road better and squat down. It’s cold now – so I occasionally stand up and pace. At last, a car sweeps up, containing my crew.

Our reunion was so hysterically joyous that I judged it worth all the drama preceding it. I felt so grateful and well-disposed towards the Ugandans for their kindness that the film was one of the most enjoyable I’ve ever made and even won some awards.

We do all seem to have been a lot less selfish, less inward-looking and generally nicer when engaging more fully with the people around us.

Looking back at my documentaries , I now think they’d have been less interesting, had I spent time, as we all do nowadays, checking my phone and connecting with people elsewhere.

Yes, a mobile enables us to call for instant help, but at the cost of discovering the best in people.

Charlotte Metcalf is The Oldie’s supplements editor and author of Walking Away, a book about her time making films in Africa

Spaghetti

Hugh Thomson loves the gentler pace, cheaper tickets and old movies at the annual Bologna Film Festival

I’ve always liked the idea of film festivals more than the reality.

All that queuing and pressure for tickets for some hyped new film you won’t get into unless you happen to know somebody from the studio.

But at the Bologna Film Festival, there’s none of the razzmatazz and paparazzi of Cannes or Venice or Berlin. As befits the city’s distinguished calm, this is an altogether more peaceful festival.

It brings considerable advantages – not least because tickets are cheap and you can get in to any movie you want, as they have a civilised queuing at the door system which always seems to yield returns on the day. And an even more civilised half price for over-65s.

It’s partly because this is a festival

exclusively of old movies, often ones which have been specially restored for the occasion. And that’s another great advantage, in that time has filtered out all the froth of films that have just been released and you’re left with only the really good stuff.

Il Cinema Ritrovato, ‘Retrieved Cinema’, sounds better in Italian –just as ‘Ti tengo d’occhio, ragazza!’ is such a brilliant subtitled translation for ‘Here’s looking at you, kid.’

There’s nothing quite like being under the stars and a midnight sky at the Piazza Maggiore in the very centre of the city with an audience of thousands – and a few fireflies – watching the screening of some old classic.

When I was there, they showed

the 50th anniversary restoration of Coppola’s great masterpiece The Conversation, a film all about recording sound. It was fun to have the urban city noises of Bologna –sirens and passing conversazione – blending into the complicated soundtrack of the actual film.

The cinemas are all relatively close together in the historic centre of the city, with a well-designed hub at the Cineteca di Bologna.

There’s an international crowd of old movie buffs like myself –embarrassingly, I remember seeing The Conversation when it first came out, having bunked off school to do it. Is there any greater pleasure than watching a film when you’re playing truant? But there’s also a younger crowd attracted by the lure of old

analogue prints, just like vinyl, and by the affordability of it all compared to your average film festival.

Charged up with excellent doppio espresso and something from a pasticceria, festival-goers can wander in a delighted daze from movie to movie, starting first thing in the morning. It’s a long time since I’ve seen four films in a single day – if ever. It’s more likely to be four films in a month. But rather like getting stuck into a box set, once you get used to the metabolic change, it starts to come easily.

I also found myself getting attuned again to the benefits of cinema-going. There are several films which I know,

if watching on a small screen, I would have got bored and given up. In the comfort of a cinema, I stuck at it and recouped the rewards. That intriguing revisionist early seventies Western McCabe and Mrs Miller had all the occasional longueurs one might expect of Robert Altman but concomitant rewards if you stayed.

Just the names of the cinemas are alluring: the Modernissimo, the Scorsese and Mastroianni theatres of the Lumière, the Jolly and the Arlecchino, with open-aired screenings in the Piazzetta Pasolini.

And then there’s the food. Not just ragù Bolognese – please don’t call it a ‘sauce’, considered a solecism locally – but also graminga clasica, a delicious sausage dish served at Da Bertonis, a regular favourite for cinema-goers as it happens to be beside one.

The house red wine is so cheap at a tenner a bottle, it would be silly just to have a glass even if you risk sleeping through that next silent classic. Although that could be a shame as some of the silent films have piano accompaniment, as with the revelatory early Marlene Dietrich movies they were screening in a Dietrich season.

These ran the gamut from the early German films to her late memorable appearance in Orson Welles’s Touch of Evil and her famous last line: ‘He was some kind of a man... What does it matter what you say about people?’

I was staying in the long-arcaded street of Via San Felice, which is a dead ringer for the set Orson Welles used in that film. I could imagine Charlton Heston skulking in the deep shadows as I headed home.

Along with the Dietrich season, there was a showcase of the (to me) unknown director Anatole Litvak. His film on post-war Germany was startling for its documentary

realism. There were also strands celebrating black and gay cinema.

Around 400 films are usually screened – so there really is something for everybody. Since the festival was started in 1986, they’ve had time to fine-tune the organisation and expand the amount of screening venues, including a spectacular new one underground below the Piazza Maggiore, in case it rains for the big, free outdoor screenings.

I went for just a couple of days, which did me fine as a spring break, but some friends attended for the full week and considered me lightweight.

As they might have said in Mean Streets, shown in a fabulous new print overseen by Scorsese himself to preserve details in the blacks otherwise crushed by digital versions, you won’t get to be a ‘made man’ – or woman – unless you put in your time working the screens.

There may not be starlets on red carpets. But intriguing directors like Wim Wenders and Alexander Payne introduce old movies they feel have been great influences on them in a charming and personal way. Payne talked about the movies that inspired him to make The Holdovers. Online streaming can sometimes give the illusion that the whole of movie history is out there at the click of a button. But, as others have pointed out, there are surprising gaps in the online catalogue for all sorts of copyright or commercial reasons – gaps that a festival like Bologna triumphantly fills.

It’s part of a growing trend –Perugia likewise has a smaller festival with the charming name of il cinema fuori moda, ‘out of fashion cinema’; ie films that are old.

oldie rates

l Festival Pass

An inclusive €120 pass is discounted to €60 for over-65s, or €30 for students.

Booking opens two weeks before the festival (21-29 June, 2025)

How much more enjoyable to watch a real film print being beautifully screened in an Italian cinema, or under the sky, with a salted pistachio cremino from the corner gelateria, than to be sitting at home wondering what Uber Eats to order while everyone talks over the movie or – even worse –munches Pringles.

And do people turn off their mobile phones when watching movies at home? I rest my case.

I’ve already booked my flights for next year’s festival.

Hugh Thomson is an awardwinning travel writer. His latest book is Viva Byron!

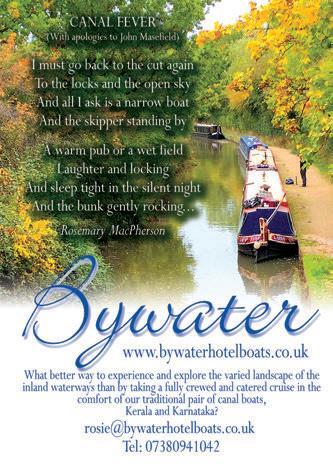

To advertise, contact Monty on 0203 8597093 or via email MontyZakheim@theoldie.co.uk scc rate £48+vat. The copy deadline for our next issue is 16th December 2024

Geoffrey Wheatcroft got a bargain hip replacement –thanks to a skiing accident in the French Alps

‘You ’ave a new ’eep!’

I’d just been turned onto my back when I heard the surgeon’s stirring words. We all know people who’ve waited months or even years for a hip replacement. One friend recently gave up and paid £13,000 to have hers done.

My hip replacement was effected within 24 hours for a trifling sum, although I wouldn’t necessarily recommend my method.

My eight-day skiing holiday in St-Martin-de-Belleville had begun badly, with two charming compatriots, Matt and Ellie, rescuing me after a tumble in falling snow – for which I never really thanked them properly. But after that it was plain schussing, and on my last morning I thought I’d have one more session in the sunshine.

My skiing is straightforward and uncompetitive. Some years ago, I skied the famous Inferno run at Mürren, where a huge race is held every January, finishing in not quite twice the time the professionals take.

So, on that last morning I was merely pottering down into Méribel when I fell for no obvious reason. A helpful skier summoned the mountain ambulance, which took me down to Méribel’s Cabinet Medical, which summoned an ambulance to the hospital in Albertville.

There I learnt that I’d fractured my femur. To repair it would mean giving me a prosthetic hip, done the next day with expedition and efficiency. I chose an epidural – so was conscious from the waist up.

Lying on my left side, I couldn’t see anything, but I could hear, and awe-inspiring it was to listen to the electric drill – which seemed like a hammer and chisel – and then the electric saw, chopping up my bones.

After this successful, painless procedure came two days of mental torment, with nothing to read, watch or listen to. All my belongings were in my hotel bedroom. So I stared at a blank wall while waiting for them to be packed and sent by taxi.

When my things did arrive, a pair

of embroidered velvet slippers was missing and a shopping bag full of cheese and terrines from the marvellous charcutier in St Martin.

As I prodded the unappetising slabs of cod I was given, I thought how wonderful it could be if I had those goodies to supplement my diet.

And it turned out that the book I’d brought with me was Jonathan Steinberg’s Life of Bismarck, a formidable work but not quite what I wanted as I lay there disconsolate. Oh, for The Code of the Woosters. This might sound like a sob-story, but it has a heroine, heroes, a happy ending and a moral. The heroine is Sally Muir, my wife and nanny. Years ago, I took her to St-Martin, hoping she’d share my enthusiasm, but after two hours on skis, she said, ‘Never again.’ While sad for me then, this

The £280 I paid Staysure was the best money I ever invested

time she was at home and able to coordinate everything needed.

Having already told me to get a GHIC (said gee-hick) card which replaced the European health card after Brexit, she informed them of my plight, and gee-hick took over, settling my medical account.

I’d grumbled to myself at the price of my holiday insurance. As it proved, the £280 I paid Staysure was the best money I ever invested: full insurance and gee-hick are my story’s moral. Once Sally had alerted Staysure, they arranged my brilliant repatriation.

The hero is Simon, my medical assistant, who arranged my hospital discharge and then returned with two ambulance drivers, who took us to Geneva Airport. At Gatwick, Simon handed me over to an ambulance and two very jolly Londoners, Lee at the wheel, Joe at the back.

There was an awkward moment when Joe gave a histrionic cry, ‘Oh God, no! Lee, you know what? We’ve got an Arsenal supporter here.’

For a moment, I thought these two Spurs fans might stop and deposit me on the A303, but they relented and drove me to my front door in Bath.

Thanking them profusely, I said I hoped that Spurs would win all their remaining games, except against Arsenal (the last wish was granted).

When I explained to people why I was on crutches, I saw a faraway look, as if to say ‘At your age?’ Well, I’m 78, and my role model is the late Peter Lunn, a fascinating figure who spent an eventful life in SIS, and was still skiing at 90 when I met him in Mürren.

At the Royal United Hospital in Bath, my amiable orthopaedic consultant examined me and the C-rays, complimented his French colleagues on a first-rate job, and said, as a keen skier himself, that he hoped I’d soon be back on the piste.

That’s what I hope myself. What otherwise is the point of my new eep?

Geoffrey Wheatcroft is author of Churchill’s Shadow: The Life and Afterlife of Winston Churchill