1874 ~ 2024

1874 ~ 2024

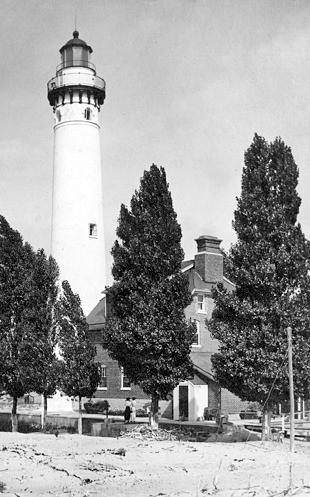

The 107’ tall Little Sable Point Lighthouse is one of the tallest in Michigan and its light can be seen as far as 19 miles out in Lake Michigan. The light is open for climbing - if you’re up for the 130 stairs that is. The view at the top is worth it!The lighthouse is open Tuesday-Sunday 10 am- 5 pm, and it costs $8 for adults to climb and $5 for children (17 and under - min. 40” tall).

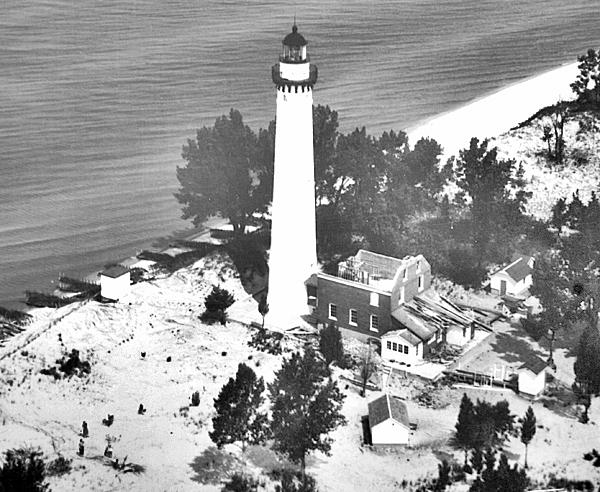

Courtesy of the National Parks Service

Born in 1832 on an Ohio farm, Orlando Metcalfe Poe would gain recognition for both military and engineering accomplishments. Immediately following his 1856 West Point graduation, where he had excelled in mathematics and finished sixth in his class, he was appointed to the Corps of Topographical Engineers (which would later merge with the Corps of Engineers) in Detroit. His survey work of the Great Lakes ended when the Civil War began.

Poe’s skills helped him become a trusted member of Major General George B. McClellan’s staff. His principal wartime duties included surveying positions, sketching routes and preparing maps of battlefields. Despite his contributions to Union successes in Ohio, West Virginia and Washington, D.C., Poe’s career suffered when McClellan fell out of favor. He did not receive the brigadier general’s rank he expected and was transferred to the Western Theater. Prior to 1864, when Union armies moved southeast from Chattanooga, Tenn. into Georgia and the Carolinas, the Western Theater was primarily a geographic designation for the area east of the Mississippi River and west of the Appalachian Mountains. Union movements there forced the Confederacy to

defend major rivers leading to the agricultural heartland of the South and would turn the tide of the war. As Poe’s talents became known, he would rise to the position of Major General William Sherman’s Chief Engineer. In his memoirs, Sherman wrote of “Poe’s special task of destruction.” Not only did Poe carry out the order to burn Atlanta in 1864, he also built the roads and bridges that made Sherman’s March to the Sea possible. At the end of the war, he was named brevet brigadier general. Since no system of medals existed at the time, the brevet rank, meaningless in terms of real authority, served to recognize gallant conduct or other meritorious service.

In 1865, with the war over, Poe became Engineer Secretary of the Lighthouse Board and supervised building projects. By 1870, he was promoted to Chief Engineer

of the Upper Great Lakes Lighthouse District. In this capacity, Poe was responsible for all lighthouse construction and designed the “Poe style” tower with a gentle taper from bottom to top. These Italianate structures feature graceful embellishments such as masonry gallery support corbels and arch-topped windows found more often on religious buildings or grand homes than lighthouses. He did not skimp on costs. His Spectacle Reef Lighthouse in the treacherous waters of Lake Huron at the eastern end of the Straits of Mackinac was the most expensive construction project of its day.

Four years and eight tow-

ers later, newly appointed General of the Army Sherman had Poe rejoin his staff as an aide-de-camp. In that capacity, he advised on engineering and security for four transcontinental railroad lines. Upon Sherman’s retirement in 1884, Poe returned to the Great Lakes. His final years were spent designing locks for the Soo Canal. Upon completion in 1896, the largest shipping lock in the world opened at Sault Ste. Marie, Mich. Eight hundred feet long and 100-feet wide, it was given his name. This work helped grow the shipping industry in the area and facilitated the development of the U.S. steel industry. Great Lakes commerce grew once large ore-carrying vessels from mining regions bordering Lake Superior gained access to the lower Great Lakes and Atlantic seaboard. Unfortunately, he did not live long enough to see the Poe Lock open. Erysipelas, brought on by injuries suffered while inspecting the Soo Locks, caused his death in Detroit Oct. 2, 1895. The epitaph on his simple marker in Arlington National Cemetery

includes the following verse from Psalms: “Mark the perfect man and behold the upright for the end of that man is peace.” Orlando Poe is responsible for much peace and prosperity. Au Sable Light Station is only one of his remarkable towers that continue to guide mariners safely along the shores of Lakes Superior, Michigan and Huron. Although rebuilt in 1968, ships still pass securely through a Poe Lock. Without the steady hand and vision of Orlando Poe, the Great Lakes would likely have played a very different role in our nation’s history. We are proud to preserve this site and tell his story.

By Sharon Hallack The Oceana Echo Community Correspondent

This year marks the 150th anniversary of Oceana County’s Little Sable Point lighthouse, located just south of the iconic Silver Lake Sand Dunes on a small piece of land that juts out into Lake Michigan. Originally named Petite Pointe Au Sable (“Little Point of Sand” in French) and renamed Little Sable Point Light Station in 1910, is known affectionately by locals as “Little Point Sable.” When Michiganders hold up their left hand to show people where they are from, one can visualize where the lighthouse is located in relation to the rest of West Michigan - at the base of most people’s pinky finger, or the “little point of sand,” its location is named after.

It’s hard to believe, but even after 15 decades of standing sentinel over the shoreline in Western Oceana County, she still stands tall and proud, against all forces of nature, safely guiding vessels of every size on Lake Michigan, and is a point of reference for landlubbers and pilots alike.

In honor of this important anniversary, Sable Points Lightkeepers Association (SPLKA) will host a special celebration at the lighthouse Saturday, Aug. 17 beginning at 10 a.m. with an official State of Michigan dedication ceremony, followed by an open house-style event. From 10 a.m. to 3 p.m. visitors can choose to take the 130 steps to the top, enjoy family fun games and activities and tour a U.S. Coast Guard boat!

An interesting part of Little Point Sable’s history is that while the lighthouse still lit the way for those on the big lake, it sat uninhabited, unloved and underappreciated from the mid-1950s to the late 1990s. About that time, four local women, Yvonne Kessler, Claire Dennison, Marcia Walsworth and Mort (Maureen) Wiegand, started saying to one another, “We should figure out how to get the lighthouse fixed up and opened to the public.”

“We went to Pete LundBorg, the Silver Lake State

was a lot of scraping, painting and repairing to do, said Carl Wiegand. “I used a chain wrapped around the handrail to get the old paint off that. My son Dean and I built the wooden decks located at ground level and around the doorway. We brought all the electrical up to date, repairing loose plaster and replacing window glass. We had a pretty regular group of about 20 volunteers.” The lighthouse officially re-opened for public tours in 2006.

Mort was the Lighthouse Seekers’ first president, serving from 1999 to 2009. Carl has served in that role since 2009. From four ladies with an interest in opening the light to visitors, the group has grown to a membership between 50 to 75 people.

In 2010, a Federal Coastal Zone Management grant allowed the construction of a paved pathway, affording even more visitors the opportunity to tour this historic landmark. Then, in 2014, a Michigan Historic Site marker was placed and dedicated at the site.

Annually, between 15,000 and 20,000 visitors make the trip to the top and are amazed at the history of this beautiful structure and its breathtaking view. Mort, a dedicated local historian, has kept an annual binder containing each year’s activities ever since. When she could no longer store the many binders in their home, she donated them to SPLKA, where they are now housed at their Ludington offices.

Park Manager at the time, and asked what we had to do. We had been having meetings, were gathering members and called ourselves the ‘Lighthouse Seekers’ group. He asked us how much money we had, and I said $35,” laughed Mort. The group gained momentum when they contacted SPLKA (formed in 1987) and became part of their association.

“Pete was really the main push. He contacted the state and the Coast Guard to get clearance,” remembers Wiegand. Once the group was given the go-ahead, a six-year restoration project began. There

For those wanting to enjoy more lighthouse history, the Wiegands invite people to visit the Oceana County Historical Museum Complex located at 5809 Fox Road in Mears Saturdays and Sundays through Labor Day from 1-4 p.m. Along with multiple buildings and unique exhibits related to all sorts of Oceana history, be sure to visit the “Lighthouse Corner.” There one will find several original items used at Little Point Sable, including the original lighthouse door, a vintage gas-powered generator used to recharge the batteries that lit the lighthouse keeper’s house, gas lanterns, a handheld telescope and a lighthouse keeper’s hat, among other related artifacts. Visitors can also view a nearly 10-foot scale model of the Little Sable Point lighthouse built by Carl in 1999. “One-inch

equals one-foot,” Carl said proudly.

The building of a lighthouse at its present location came about following several shipwrecks near that area of Lake Michigan. The United States Congress approved funding in 1872, however, due to accessibility issues, the light station wasn’t completed until 1874. The original quarters included a two-story structure that housed the keeper and assistant keeper and their families, with each family living on a separate floor. In 1911, dormers were added, making the quarters a three-story house. Afterward, the house was split into a “south side” used by the keeper and his family, and a “north side” was used by the assistant and his family.

According to an “Office of Engineer’s Ninth LightHouse District” rendering of 1909, the lighthouse sat 154 feet from the water. The property also included a stable built in 1889 and later an oil house and coal/ wood shed in 1902.

The light station tower was painted white in 1899 (to make it more visible to ships during the day) and remained that way until 1977, when the Coast Guard decided not to keep painting it in order to reduce maintenance. The tower was sandblasted, removing the many coats of paint and revealing the red brick that is seen today. Little Sable is the oldest remaining brick tower on the Great Lakes.

Hank Vavrina was the last official “keeper” of the lighthouse. He and his wife, Henrietta, served from 1948-1954 until the light was electrified in December 1954. The accompanying lighthouse keeper’s quarters were torn down in the late 1950s, after the house had fallen into disrepair and had become a site for vandalism.

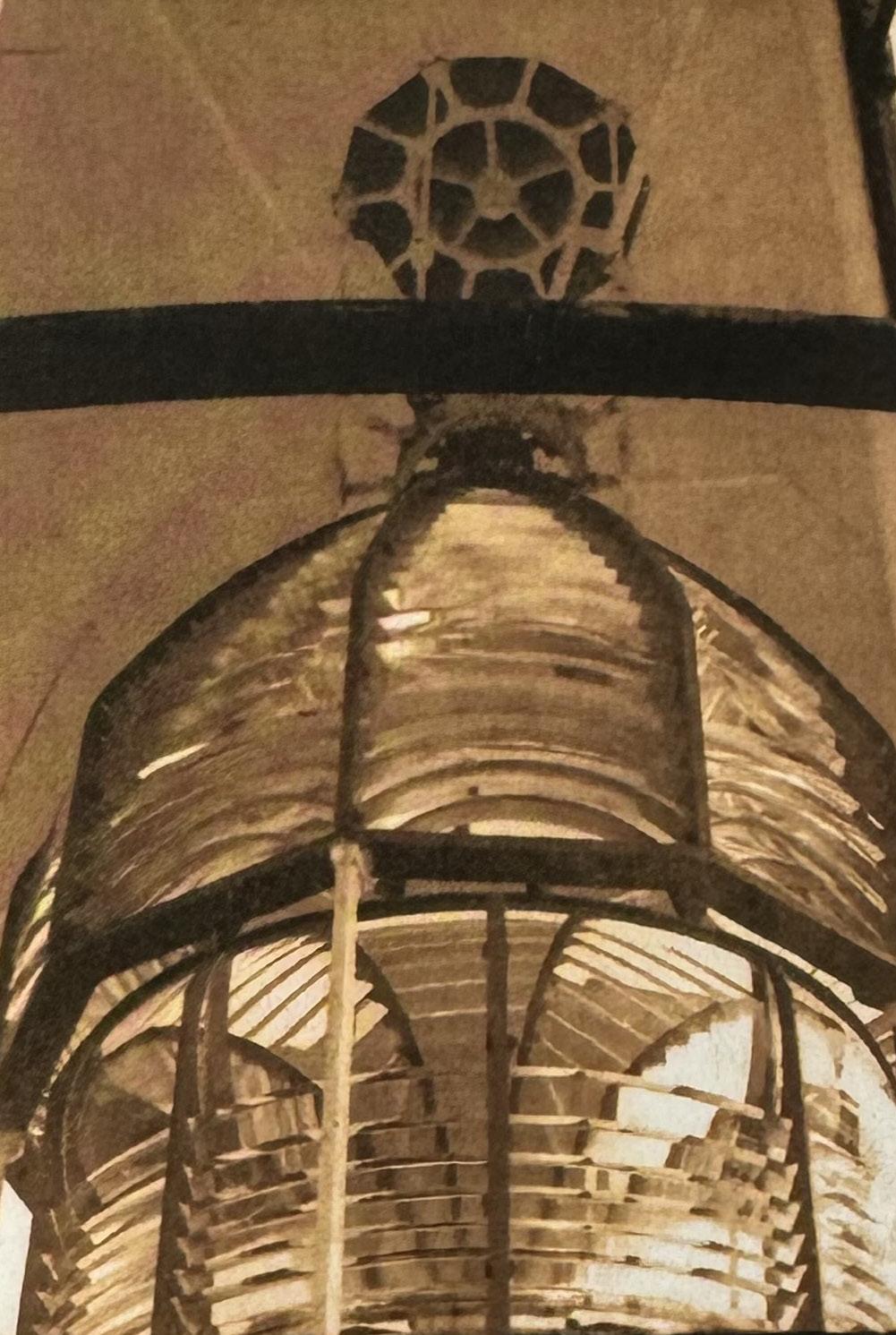

The original third-order Fresnel lens, manufactured in France, is still in use and sits 108 feet up in the lantern room. The term “third-order” refers to the light’s size and focal length, or range. Little Sable Point’s range is reportedly 17-19 miles. The lighthouse is currently owned by the Coast Guard and sits on property owned by the State of Michigan.

(Almquist) Tennant, was part of the Lighthouse Seekers prior to her passing and shared many memories of living there as a child. “There were no trees around the lighthouse in the 1920s,” Wiegand said. “Alice said she and her three siblings could run around and play and her father would keep track of them from the top of the lighthouse. He was a single father. His wife, Alice’s mother, left them shortly after being stationed there. She couldn’t stand the seclusion.”

Hank Vavrina, a widower, was the father of two young daughters and the last lighthouse keeper at Little Point Sable. While stationed there, he met Henrietta “Pinky” Harkenrider, the mother of two sons who lived in Hart. They were later married at the Flora-Dale Resort in Silver Lake. “All four kids lived at the lighthouse and attended Wilson School,” Mort recalls.

The Wiegands are still enjoying being involved with the Lighthouse Keepers group and intend to stay involved as long as they can. The group holds three official meetings each year: in April, July and September. They also host monthly beach clean-ups on the beach from June to September on the first Monday of every month at 9 a.m.

When asked what the main questions visitors ask are, Mort said with a smile, “How many steps to the top? How tall is it? and “When was it built?”

They are looking forward to joining the entire SPLKA community Saturday, Aug. 17 from 10 a.m. to 3 p.m. for the 150th anniversary celebration. “We will have a table with information on how to join our group, and one of Pinky’s sons, Jerry Harkenrider, is planning to be there as well.”

The Wiegands have lived in Mears their entire lives and knew the last two lightkeeper’s families who lived at the lighthouse, the Almquists and the Vavrinas.

Lighthouse keeper Almquist’s daughter, Alice

Visitors are welcome to visit and tour the lighthouse Tuesdays through Sundays, 10 a.m. to 5 p.m., from May to September. A charming 1965 Avion “Gift Trailer” is available on site, offering more information and souvenirs for purchase.

Anyone interested in becoming a “Lighthouse Seekers” member or a SPLKA member should contact them at 231-845-7417 or visit www.splka.org.

James Davenport (1873 – 1879)

Gabriel Bourissau (1879 – 1885)

Lawrence Kilmurry (1885 – 1886)

George Buttars (1886 – 1890)

Joseph Hanson (1890 – 1899)

Joseph Arthur Hunter (1899 – 1922)

Wallace S. Hall (1922 – 1923)

Lewis N. Allard (1923 – 1924)

Charles Lennis (1924 – 1930)

Arthur Almquist (1930 – 1935)

Daniel E. Martin (1935 – 1939)

William E.H. Kruwell (1939 – 1941)

William c. Kincaide (1941 – 1945)

Raymond Robinette (1945 – 1948)

Henry Vavrina (1948 – 1954).

John Carley (1874 – 1878)

Fred W. Teachout (1878 – 1879)

James Lasley (1879 – 1880)

F.G. Bourissau (1880 – 1881)

Bertram M. Jones (1881 – 1882)

Antony Gauthier (1882)

Lawrence Kilmurry (1882 – 1885)

John F. Cumming (1885 – 1886)

John Millidge (1886 – 1888)

Robert Wixson (1888 – 1889)

Belden J. Margeson (1889 – 1890)

Joseph A. Hunter (1890 – 1899)

George W. Chamberlin (1899 – 1910)

Gertrude Helen Hunter (1910)

Guy Patterson (1910 – 1922)

John J. Hahn (1922)

Henrik G. Olsen (1922 – 1925)

Arthur S. Almquist (1925)

Royal G. Peterson (1925)

Frederick W. Leslie (1925 – 1927)

Edward R. Ledwell (1926 – 1931)

Alvin R. Anderson (1931 – 1933)

Frank R. Winkle (at least 1935)

Henry Vavrina (1939 – 1942)

W. O’Connor (1942 – 1943)

Raymond Robinette (1943 – 1945)

Willis G. Chance (1945)

Henry Vavrina (1945 – 1948)

James Bellows (1948 – 1954).

Tower height - 107 feet

Top of lantern - 115 feet

Approximately 120 feet from ground to top of roof

Range of kerosene light - 19 miles

Range of electric light - 17 miles

Tower owner - US Coast Guard

Land owner - State of Michigan

Oldest remaining “brick” tower on the Great Lakes

This model lighthouse, at right, is scaled in inches to feet (one inch equals one foot). It stands at 10-feet tall and was constructed and donated by Carl and Maureen Wiegand of Mears, Mich. to the Oceana County Historical &GenealogicalSocietyMuseum.Itiscurrently on display at the Mears Museum Complex.

By Steve Gunn The Oceana Echo Community Correspondent

To some people, old Lake Michigan lighthouses may seem like useless relics from another era.

But Oceana County’s Little Sable Point Lighthouse is far from being an abandoned or irrelevant structure.

Thousands of tourists visit the old lighthouse every year, and it’s staffed throughout the summer by volunteer keepers who greet visitors, provide historic information and keep the structure clean.

The beach near the lighthouse is also the site of a popular weekly concert series in the summer.

It’s a special building with a strong connection to the past that remains a vital part of the local recreational scene. It’s located on the southern end of the beautiful Silver Lake State Park, so people can enjoy the natural beauty of the area, like the famous sand dunes, while also getting a taste of our maritime heritage and a great view of the lake from the top of the lighthouse.

That’s why local officials are excited about celebrating its 150th anniversary this summer. A special ceremony marking the sesquicentennial is scheduled for Saturday, Aug. 17 from 10 a.m. to 3 p.m. at the lighthouse.

There will be a special state of Michigan tribute for the role the lighthouse played in Lake Michigan shipping over the years, and for the work that’s been done to maintain it. There will also be a U.S. Coast Guard presence, and lots of family-oriented crafts and games.

“It will be more of a kids’ event,” said Jack Greve, executive director of the Sable Points Lighthouse Keepers Association, which leases the structure from the state and maintains it. “We really want to draw the interest of young families.”

There is a lot of history behind the old lighthouse, which used to play a crucial navigational role for ships and boats traveling up and down the shoreline.

It was constructed after the completion of two

lighthouses further north along the shoreline – the Point Betsie Lighthouse in Frankfort (1858) and the Big Sable Lighthouse in Ludington (1867).

One major reason for constructing a lighthouse at the site was the shallow water in the area, according to Greve. That problem was illustrated by the 1871 beaching of a ship called the Pride.

“The lighthouse was a way of saying, don’t go in there, don’t wreck your boat,” Greve said.

The finished structure stood 115 feet in the air and became the tallest lighthouse in Michigan, according to the Michigan Bed and Breakfast Association.

The lighthouse cast a constant white light, which flashed brighter at regular intervals and was visible 19 miles into the lake.

The lighthouse still emits a beacon into Lake Michigan every night, under the management of the U.S. Coast Guard, but is no longer considered an official navigational guide.

The light is still useful for boats out on the lake, and a few years back, when an unmanned kayak was spotted in rough waters, officials sent someone to the top of the lighthouse to see if they could spot a person in distress.

More than anything, however, the historic structure has become a popular destination point for visitors.

Every year, about 16,000 to 18,000 people pay to enter the lighthouse, Greve said. There are no guided tours, but historic information is available.

The lighthouse is open to the public Tuesdays through Sundays from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. during the summer season. This year, it opened May 21 and will close Sept. 8.

Admission is $5 for students 17 and under, and $8 for adults. There is a 40-inch minimum height requirement to enter the structure.

The summer concerts are on Wednesday nights and sometimes draw as many as 60 people in good weather, according to Greve.

“It’s a pretty big draw,” Jody Johnston, manager of Silver Lake State Park, said about the lighthouse. “Here at the park, it is secondary to our ORV area and the dunes, but it is definitely on people’s lists to go to that area and see the lighthouse.”

Some visitors are interested in learning about the past, but many simply want to climb to the top of the tower, which is not easy, considering its 130 steps up a winding staircase.

“I get winded going up,” Greve said. “There are platforms and resting areas along the way, but it’s not an easy task.”

“It’s a little physically demanding,” Johnston added.

By Caleb Jackson The Oceana Echo Community Correspondent

Oceana County owes a debt to Little Sable Point lighthouse that could probably never be fully realized. It is the light of her third-order Fresnel lens, penetrating 19 miles into the darkness over the lake, that helped safely guide lumber ships at night in the early days of our history. The Little Sable Point of today continues to be a major tourist pull for our region, along with the dunes upon which it stands. This light is maintained by SPLKA, the Sable Points Lighthouse Keepers Association, who regard Little Sable Point as “easily the busiest” of their lights, and it is that fact that her lens still shines that makes her unique among lighthouses today. Little Sable Point is one of the eight lighthouses in Michigan whose Fresnel lens is still in operation, and one out of a mere 80 nationwide.

The light has undergone some changes over the years. Initially, the tower was a bare brick, but sailors complained about its visibility, so in the year 1900, it was whitewashed. A number of keepers and their families lived in the house. Eventually, the tower would be electrified. With the light running on electricity, a keeper was no longer needed and soon, the house would be torn down. Fifteen years after that, the tower was sandblasted, returning it to its original red brick walls. This happened in 1975, three quarters of a century after it was initially whitewashed.

It is perhaps easy to take the lives of lighthouse keepers for granted. To us, it is something solitary and unknown. However, there are a surprising number of sources to tell us about the keepers of Little Sable Point. One of those sources are the journals of Arthur Hunter, brought to us by Vinetta B. Ling. Hunter was the longest keeper of the light for 32 years, serving from 1890 to 1920. Prior to this, he was the assistant keeper to Joseph Hansen for nine years.

Ling was connected to the Hunters via marriage. Her aunt married Herbert Hunter, the son of Arthur and Gertrude Hunter. During Ling’s time growing up in Oceana County, she would often visit the old lighthouse keeper on holidays, after he had retired from the light. She has received Arthur Hunter’s journals and collected them into three books, “What These Walls Could Tell,” “Keeper of the Light,” and “The Waves Still Roll.”

On the back of the first book, she gives us a bit of insight into what the daily life of a lighthouse keeper was like. The night was divided into two watches. Hunter would often climb the stairs in the evening to take the first watch. He would switch off with his assistant around 2 a.m. At the top of the tower, he could

read or write letters, or if it wasn’t a school night, his children could accompany him. Ling writes, “each morning, burners were changed, lens and clock works cleaned and polished, stairs swept and windows washed.”

Hunter would often make daily trips into Mears to pick up mail and supplies, and in the spring, most of the rooms in the tower were whitewashed. “If a horn was heard from the inspector’s boat,” Ling wrote, “all else came to a halt, and everyone worked to make sure the place was clean and in order for the inspection.” It was a busy life, and maybe not quite as lonely as one might imagine. Each and every spring, the Hunter family would go over the sand dunes to collect huckleberries and arbutus flowers, as Arthur’s wife Gertrude would send the arbutus to friends and family.

Another source of information regarding life in the house can be found in volume one of the Oceana County Historical & Genealogical Society’s history of Oceana. There, Alice Almquist, whose father was a keeper in the 1930s, tells us what it was like for her:

“The first thought that comes to me of memories of Little Point Sable Lighthouse, is remembering the isolation of it. In seasons other than summertime, we saw no one.

Our coal and other fuel was delivered by the lighthouse tender which anchored off shore and then used a small boat to bring the supplies to the beach. Planks were laid on the beach to the house and the coal was chuted in our basement by wheelbarrow. At this time the library was also delivered. I remember the good books we were able to read in the winter time. Oh yes, the lighthouse tenders had names of flowers. I remember Sumac, Hyacinth and Marigold.

The house had three stories. We two girls had our room in the third story. It had a big walk-in closet with a window on the end. We used to put on plays. This closet was our dressing room.

Sometimes geese would fly into the light and break their necks. I remember one time seeing five geese roasting in a huge black pan my mother had. I liked stormy days when the waves of Lake Michigan were high, to run along the beach with the wind blowing my hair and of course, I was barefoot. When I first had wheatena cereal it reminded me of that wet beach sand. One time my sister and I made a wooden platform of material found on the beach. We spent some nights sleeping on this platform. It was wonderful to hear the ripple of the waves. We did use lots of citronella - our defense against mosquitoes.

We were walking two miles to school at Silver Lake when our school house

burned down. We had to finish the year in the wood shed. The next year we walked two and a half miles farther to the Willson School. The road along the channel is now quite high above the channel. When I lived in that area the road was level with the channel and when the water was higher than normal it washed over the road and sometimes we got stuck. There was about a half mile of planking from the lighthouse to get to the place where the ground was more firm. We had a gate at the end of the plank road to keep the public off. You couldn’t meet anyone, as to get off the planks would mean getting stuck in the sand. There was a lot of brass to polish and lamps and even dustpans. It was nice looking at the hills at night and seeing the rays of the revolving light of the lighthouse swept over the hills at the same time listening to the whippoor-wills. There was no foghorn in this lighthouse. We lived in the Little Point Sable Lighthouse for the first time in the twenties. My dad tells me that, when he couldn’t find us, he would climb all those steps to see if he could find us. He could! These steps had a lacy cut-out work to them. [They still do.] When we had visiting day, sometimes the ladies with high heels would get them caught in these steps.

The boat house wasn’t in use so my dad had it moved up by the house. We used it as a summer kitchen. Sometimes the Coast Guard from Grand Haven would come up and set out nets in Lake Michigan and spend the night with my dad in the summer kitchen. We had some good fish as a result. We had our basement full of canned fruits and vegetables; also apples. Winter evenings we would have apples and popcorn while our mother would take words out of the paper for us to spell. Oh yes, the mailbox was a mile and a half away.”

Although it no longer stands, the keeper’s dwelling must have been magnificent. It was a 12-room, two-and-a half-story building, built and expanded to accommodate the keepers’ growing families. And it seems that what once qualified as family time for the Hunters was actually a form of punishment for the Almquists, as her parents would make her and her sister go pick huckleberries if they misbehaved.

It is easy to visit a lighthouse and imagine the dark and brooding keepers that books and movies seem to portray. This summer, however, I suggest an alternative. If anyone finds themselves climbing the staircase at Little Sable Point, you should try to imagine the bright and vibrant lives that filled the place not too long ago: the hardworking keepers, their dedicated wives and their energetic children climbing the stairs to hear a bedtime story from their father before they turn in for the night.

It stands beside the inland sea, That massive tower of white That lifts on high the friendly gleam Of Little Sable’s light.

The keeper climbs the winding stair The monster wick to trim, And rub the lamp that in the night His light shall not be dim.

Sunset sees the light begin; And oe’r the sea it shines about, Revolving with its signal flash ‘Til sunrise turns it out.

The people on Benona’s hills And they who live on Golden farm Rejoice to see the Hunters light Which guides the ships and saves from harm.

Tonight beside the Sable’s glen On the shore of Golden sand The friend of ships and friend of men Shall watch the sea and land.

Getaway

Used with permission from Kraig Anderson

Take a look at a map of Lake Michigan, and you will see three prominent “bumps” along its eastern shore. Point Betsie, the northernmost of these bumps, received a lighthouse in 1858, and Big Sable Point, the next bump going south, got its lighthouse nine years later. In 1871, the Lighthouse Board noted that “a simple inspection of the chart of Lake Michigan” would demonstrate that a third-order, lake-coast light was needed on the third bump, Little Sable Lighthouse, which protrudes farther west than the other two bumps. In early records, this point was referred to by its French name, Petite Pointe au Sablé, which translated means Little Sand Point.

Complying with the Lighthouse Board’s request for funds, Congress appropriated $35,000 for the lighthouse on June 10, 1872. Over 40 acres of what was public land were set aside by President Ulysses S. Grant the following month, and a working party arrived at the site the following April. The crew first built a dock for landing material and provisions, followed by temporary buildings for their accommodations and for protecting the construction material. By July, more than 100 piles had been driven into the sand and topped off by a timber grillage to serve as a foundation for the tower. A cofferdam was then built in the sand so that the ground water could be pumped out and cement could be poured over the grillage.

With the foundation in place, work began on the brick tower, which slowly grew to a height of roughly 100 feet. Atop the tower, a decagonal lantern room was installed to house a third-order Fresnel lens, manufactured by Sautter & Co. of Paris, France. This lens was different than most in that its lower and center sections were fixed, while its upper section, made up of ten bull’s-eye panels, revolved once in five minutes to produce a flash every thirty seconds. Brackets supporting the upper section of the lens were connected to a pedestal that revolved atop chariot wheels. Every eleven hours, the keepers had to wind up a ninety-pound weight that was suspended between the tower’s inner and outer walls and powered the revolving mechanism.

A covered way connected the base of the tower to a twelve-room, two-and-a-half-story dwelling built for the light’s two resident keepers. The tower and dwelling were both left their natural red brick color. James Davenport, who was transferred from his position of assistant keeper at Waugoshance Lighthouse to be the first head keeper at Little Sable Point Lighthouse, activated the light atop the tower upon the opening of navigation in 1874. John Carley served as the station’s first assistant keeper.

Lighthouse

and

wife,

The first of several shipwrecks recorded in the station’s logbook was entered by Keeper Davenport on Aug. 6, 1875 when the schooner Black Hawk ran aground on the point. Keeper Davenport noted “crew all saved.” Records of shipwrecks near the station were numerous in the late 1880s, when western Michigan provided much of the lumber for Chicago and other growing ports on the Great Lakes.

A circular iron oil house, capable of holding 360 gallons, was built 100 feet northeast of the tower in 1893, and a decade later, a brick oil house with a metal roof and door was added. In 1900, the tower was painted white to set it off from the surrounding dunes, and in 1911, dormers were added to the top story of the dwelling, greatly expanding its living space.

Joseph Arthur Hunter served as head keeper at Little Sable Lighthouse from 1899 to 1922, longer than any other keeper. On Dec. 9, 1904, while driving his team of horses along a road, Hunter encountered his first car. Keeper Hunter was a Wesleyan Methodist and took his religion seriously. In 1905, he heard a speech he thought would convince anyone to be a prohibitionist and the following year he voted for prohibition. Keeper Hunter would patrol the beach near the lighthouse, gathering anything that washed ashore. By 1922, he had salvaged enough shingles and lumber to build his retirement home.

On May 22, 1926, Congress passed an act authorizing the Secretary of Commerce to sell unused portions of the lighthouse reservations at Big Sable and Little Sable to the State of Michigan for public park purposes. The area near Little Sable Point Lighthouse, which includes numerous sand dunes, is now part of Silver Lake State Park.

Henry Vavrina was serving as assistant keeper to William Kruwell in November 1940, when the Armistice Day Storm struck the area. Wind gusts of ninety-two mph whipped up thirty-foot waves that hammered the eastern shore of Lake Michigan. The lake freighters William B. Davock and Anna C Minch foundered off Little Sable Point, taking down fifty-six crewmembers with them. The Canadian freighter Novadoc, bound from Chicago to Montreal with a load of carbon coke, ran aground just north of the point, but all but two of its crew of nineteen were able to survive by going below decks. The men were saved by Clyde Cross, captain of the tug The Three Brothers, who braved mountainous seas to reach the freighter. After being rescued, Captain Steip of the Novadoc handed Captain Cross a roll of bills as a token of his gratitude. Captain Cross leaned back against the bulkhead of his tug, eyed the money, and replied, “Hell no, captain. Glad to be of service.” A Coast Guard board of inquiry was held to determine if its Ludington station was negligent in not reaching the Novadoc before the tug. Keeper Kruwell testified that conditions prevented the crew at Ludington

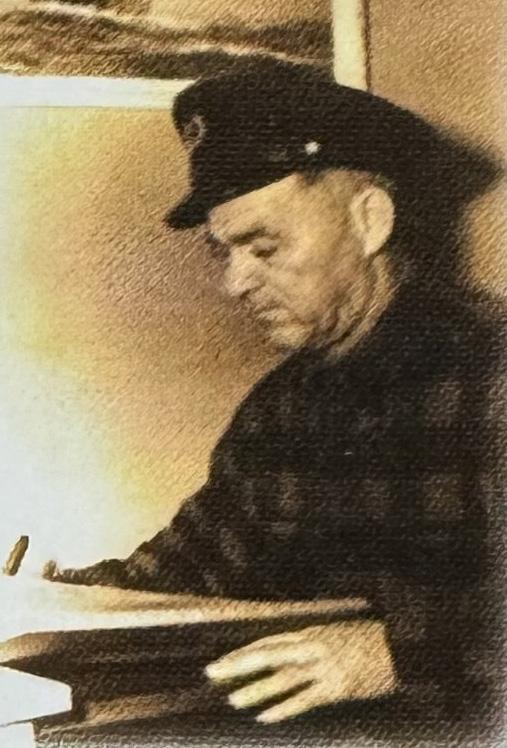

The third order Fresnel lens, above left, is very rare. It emits a constant white light, but would also flash a brighter light at fixed intervals. The flash was produced by the rotation of the top part of the lens, powered by a weight-driven clockwork mechanism. Little Sable Point keeper Henry Vavrina can be seen taking notes, above right. • Photos courtesy of OCH&GS

from responding sooner.

After Keeper Vavrina lost his wife before World War II, he raised their two daughters at the lighthouse, where he was known by many in the area as a fine cook. In 1947, Keeper Vavrina hosted a large party at the lighthouse, treating his guests to a dinner that included homemade rolls, pies, and other treats served on freshly pressed linen cloths. This was quite the feat for the keeper, considering the station had no electricity. In 1949, Keeper Vavrina married Elizabeth Harkenrider, a local divorcée who had two young sons. It was hard for many to understand why it took so long for electricity to reach the station as nearby towns had power, but whenever anyone mentioned this to Keeper Vavrina, he told them to not stir the pot. He enjoyed his little lakeside paradise and rightly knew that it would disappear when electricity arrived. Before being electrified, Little Sable Lighthouse was reportedly the last lighthouse on the Great Lakes using an incandescent oil vapor lamp.

Henry Vavrina was promoted to head keeper of Little Sable Lighthouse and served in this capacity from 1948 until 1954, one year after the station was electrified and automated. The pavement around the lighthouse was in poor condition as shown in this photograph taken in 1951. Keeper Vavrina transferred to Big Sable Lighthouse, where he served another decade before retiring. No longer needed, the handsome brick dwelling at Little Sable was torn down in 1958, leaving the tower alone on the beach. The tower was sandblasted in 1974 to eliminate the need for regular painting.

In 2005, the Michigan Department of Natural Resources leased the lighthouse to the Big Sable Point Lighthouse Keepers Association. The 25-year lease allowed the group to open the tower to the public for the first time since the late 1940s. An organization known as the Little Sable Point Lighthouse Seekers was formed in 1999 with the goal of opening the tower, but after exhausting many options to reach their objective, they reached out to the Big Sable group for help in 2002. Big Sable Point Lighthouse Keepers later changed their name to Sable Points Lighthouse Keepers Association to reflect their expanding role in overseeing multiple lighthouses.

In 2010, a Federal Coastal Zone Management grant funded the completion of a paved pathway through the dunes to the lighthouse, making the trek to the tower much easier. Little Sable Point lighthouse was deactivated in 2014.

James Davenport, the first lighthouse keeper at Little Sable Point, was the grandson of a Native American chief, Chief Waubojeeg.

The original light was produced by a lamp with three concentric wicks which initially burned lard oil, but later burned kerosene. A lens made of hand-ground glass prisms intensified the light so it could be seen for 19 miles out into the lake.

J. Arthur Hunter was the longest serving lighthouse keeper. He started in 1890 as assistant keeper and was promoted to head keeper in 1899. In 1905 he put glass insulators on a stool he used while on watch in the tower, to prevent being struck by lightning. He retired in 1922.

From February 15 to March 17, 1906, the light shone steadily instead of flashing because the clockwork mechanism was being repaired.

The original name of the lighthouse was Petite Pointe au Sable, French for Little Point of Sand. In 1910 the official name was changed to Little Sable Point Light Station.

Also in 1910, Little Sable Point had a woman, Mrs. H. Gertrude Hunter, J. Arthur Hunter’s wife, as assistant keeper for one month.

In 1935, W. Owen Martin, age 25, son of lighthouse keeper, Daniel E. Martin, fought a raging fire in a second story bedroom of the lighthouse. Owen was assisted by his father, the assistant keeper, and the 12th District Assistant Superintendent of Lighthouses. He managed to extinguish the fire and later was taken to the hospital for treatment of smoke inhalation.

The Sable Points Lighthouse Keepers Association (SPLKA) works to preserve and promote Big Sable Point Lighthouse, Ludington North Breakwater Lighthouse, Little Sable Point Lighthouse and the White River Light Station. Each season, SPLKA places education about the importance of lighthouses in Michigan at the forefront for more than 40,000 guests.

With this 2024 season, SPLKA’s Executive Director, Jack Greve, hopes to inform lighthouse goers that this year has included some subtle but impactful operational changes: “To align SPLKA with the state parks and other stakeholders, service animals will now be welcome with their handler to enter all main-level public spaces. This includes video rooms, main-level historical displays, and gift shop spaces.”

Service animals will not be allowed to climb any towers and should not be left alone. “We reviewed policies at other lighthouses in Michigan and have looked inwardly at SPLKA’s safety measures in the tower. Having a service animal in any lighthouse tower produces additional challenges for any evacuation plan.”

Additionally, SPLKA is allowing up to 10 guests in a tower at any time, only two less than the previous allowance of 12 in recent years. “While reviewing policies state-wide and at our own sites, reducing the number in the tower will make for a safer and less-crowded experience while climbing and descending over 100 steps.”

To combat overcrowding this season, SPLKA has also extended its hours to better serve its guests. “Post Covid, SPLKA has been open six days per week, Tuesday through Sunday, from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m.,” Greve said, adding that they tried something new this season, being open seven days per week in July at the Big Sable Point and Ludington North Breakwater Lighthouses. Additionally, the Ludington North Breakwater will have sunset climbs available during the Ludington beach bonfires, and the White River Light Station will have regular season hours through Oct. 28.

Big Sable Point opened May 7, and the others opened May 21. Adults climb for $8, students (17 and under) for $5, and veterans, active-duty and reserve service members climb for free. All climbers must be 40-inches to climb, able to climb on their own and wear shoes that connect at the heel (no flip-flops allowed).

For any questions, please call SPLKA’s office at (231) 845-7417.

By Andy Roberts

The Oceana Echo Community Correspondent

SHELBY — The 150th anniversary of the Little Sable Point lighthouse, which will be celebrated Saturday, Aug. 17, is a happy occasion for folks like Dave Dietrich. Dietrich is the great-great-nephew of James Davenport, the first keeper of the lighthouse. The event will, though, present a slight travel issue for Dietrich.

Dietrich, 83, has a brass plaque set into a marble block, marking the grave’s occupant as a lighthouse keeper, that he’s planning to add to Davenport’s grave in Mackinaw City; Davenport’s final post was at the McGulpin Lighthouse there. Dietrich said the National Lighthouse Association has been encouraging the placement of such plaques of late because they view the old lighthouse keepers as “heroes of the light” and believe they should be recognized in death.

This is all well and good, and Dietrich made the trip to Mackinaw City this week with his wife, Mary Jo. Of course, after he made the reservations for his trip, he shared his plan with the Sable Point Lighthouse Keepers Association, and director Jack Greve told Dietrich, “We’d sure like to have that (plaque) during that celebration.”

That slightly changed Dietrich’s plan. He planned to bury the plaque in the ground on the trip, but instead took a photo of the plaque next to the gravesite, then brought it back for the celebration. He said he and Mary Jo may return to Mackinaw City in September as part of a celebration of their wedding anniversary, at which time he will actually put the plaque in the ground.

Davenport took the Little Sable post in 1874 as soon as the lighthouse was operational, after being transferred from Waugoshance Lighthouse in the Upper Peninsula, which was surrounded by water. That was a move Dietrich describes as “like going

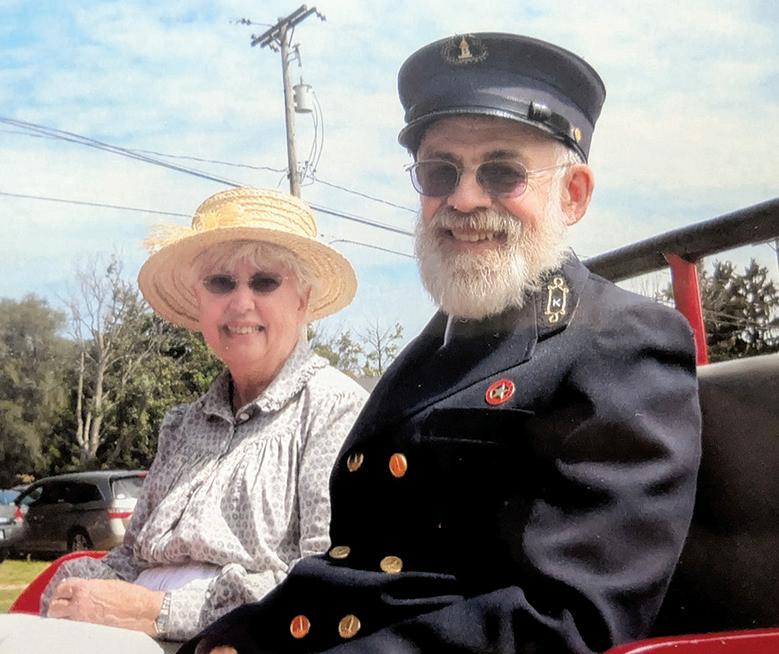

Dave Dietrich plans to bury this plaque, above left, adjacent to the gravesite of his great-great-uncle, James Davenport, in Mackinaw City this fall in tribute to his service as keeper of multiple lighthouses, including Little Sable Point. Dietrich and his wife Mary Jo, above right, can be seen with Dave in full lighthouse keeper uniform.

from a shack to a palace.” Waugoshance, always a less aesthetically pleasing lighthouse than Little Sable Point, still exists, but is now in a ruined state, having been used for U.S. Navy bombing practice during World War II. Reportedly, the lighthouse is likely to fall into the lake at some point, and a 2021 MLive article stated that a nonprofit devoted to preventing that fate had dissolved.

This is in stark contrast to Little Sable Point, which, despite closing in the 1950s, remains well-maintained and is the centerpiece of the beach at Silver Lake State Park. The lighthouse closed at that time because the availability of electricity and automation negated the need for a keeper. The house next to the lighthouse was designated for the keeper and their family to live in and proved useful to the Davenport family, as James and his wife Madeline had

10 children. The house, though, was torn down upon the lighthouse’s closure; as Dietrich said, “the Coast Guard is not into real estate. They’re into saving people out on the lake.”

Dietrich, of course, never met Davenport, who died in 1891, but briefly knew James’ nephew Albert in his youth. He also lived with his grandmother, Elsie Davenport (James’ great-niece), until he was 16, when Elsie passed away. Elsie was a lighthouse kid as well; her father Albert entered the family business and was a lighthouse keeper too, and Elsie was born at Rawley Point Lighthouse in Wisconsin, where her father was stationed at the time. Albert’s career in lighthouse keeping ended, as it happens, at the Pierhead Light station in Pentwater.

It wasn’t until later that Dietrich became enthralled with his family history of lighthouse keep-

cold soft drinks. Enjoy one of our delicious pizzas or order a sub

your cravings. Headed to the dunes? We got you covered! See us for all your dune needs including gas, flags, mounting brackets, ORV and State Park Stickers. You can also find camping supplies, automotive, marine oils & additives, spark plugs and parts for emergency repairs.

Conveniently located at the center of Silver Lake with close proximity to all of your favorite attractions! GET TO THE POINTE!

ing, and in 2002, while living in suburban Chicago, he began volunteering his time at the Big Sable Point lighthouse in Ludington, where he gave tours. Aware that Little Sable Point was being restored with an eye toward reopening it, Dietrich’s goal was to begin working there. And so he did, once the Little Sable Point lighthouse reopened a few years later. He’s continued to do so ever since - he even met his current wife, Mary Jo, through that work, as she was also a volunteer there, and moved to Shelby - though due to obligations at home, he hasn’t been able to this year.

Dietrich’s first wife, May Bennett, who passed away in 2009, was what Dietrich calls “an amateur genealogist,” and became interested in helping Dietrich dive into his family history. She was able to trace his line back to the late 1700s and found that Dietrich has a very small amount of Native American ancestry through James Davenport’s mother, Susan Des Carreaux (pronounced de-CROY), a member of the Chippewa tribe. Des Carreaux, like many of the Davenport family members of the age, is buried on Mackinac Island.

Dietrich has very few artifacts from Davenport, though he does possess an old compass, which he inherited from his parents. The compass would’ve been used by nautical navigators to find their way in a time before GPS.

Most of his family’s lighthouse history is available to him through the Little Sable Point structure - “it’s a government building. Anything that was in there belonged to Uncle Sam at the time (it closed),” Dietrich said - which still has the old Third-Order Fresnel lens that once alerted ships to the nearby presence of land. The lens is one of very few that is still operational.

“We’re very thankful that we’re able to keep it, because most lighthouses, the Coast Guard has required them to dismantle it and put it in museums,” Dietrich said of the lens, noting the Big Sable Point’s Fresnel lens is now in Ludington’s Maritime Museum.

A painting Dave Dietrich created of the Little Sable Point lighthouse, above, as it would’ve appeared during its heyday, when it was painted white and the keeper’s house still stood next to it.

Dave said he very much enjoys his volunteer work and feels connected to his family history when taking guests up and down the stairs of the lighthouse. So devoted is he to spreading the history of lighthouses that he makes sure guests hear about the old Fresnel lens at Little Sable Point, even if at first their only interest is making it to the top of the stairs and seeing the remarkable view.

Dave is also an artist, a skill he says he got from his grandmother that paired nicely with his background in architecture. He used that skill years ago to paint a beautiful image of the Little Sable Point lighthouse as it appeared during its heyday, when it was painted all white (the Coast Guard stripped the paint in the 1970s). He also included the old residence next to the lighthouse in the painting, using a black-and-white photograph and what he knew of the old house to paint it the correct color. Dietrich said he used a magnifying glass while doing the painting, and the care he used shows in the final product, which is on display in the home he shares with Mary Jo, along with a few other works of his.