Meredith

Heather

Maree

EXECUTIVE

Brian Knapp

ASSOCIATE

Kari Apted

PHOTOGRAPHER

Michie Turpin

CONTRIBUTING

Chris Bridges

Michelle Floyd

Phillip B. Hubbard

Cullen Johnson

Avril Occilien-Similien

Wendy Rodriguez

David Roten

ILLUSTRATOR

Scott Fuss

Meredith

Heather

Maree

EXECUTIVE

Brian Knapp

ASSOCIATE

Kari Apted

PHOTOGRAPHER

Michie Turpin

CONTRIBUTING

Chris Bridges

Michelle Floyd

Phillip B. Hubbard

Cullen Johnson

Avril Occilien-Similien

Wendy Rodriguez

David Roten

ILLUSTRATOR

Scott Fuss

by BRIAN KNAPP

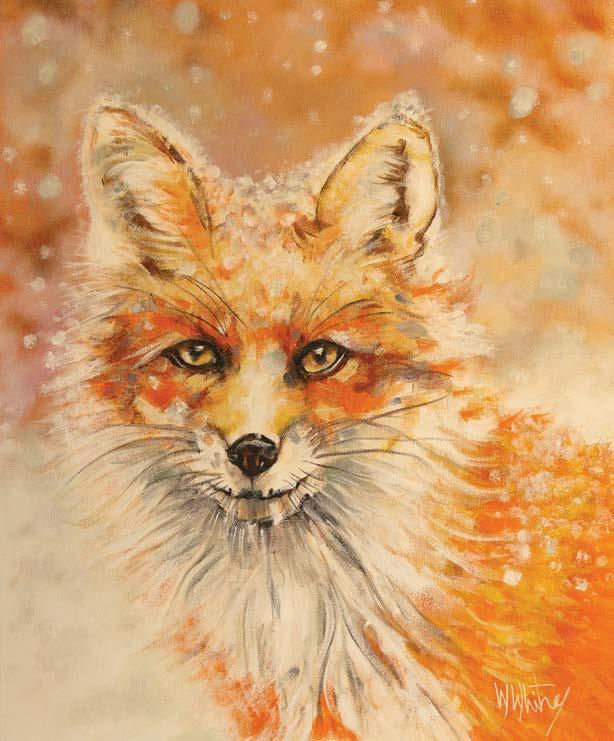

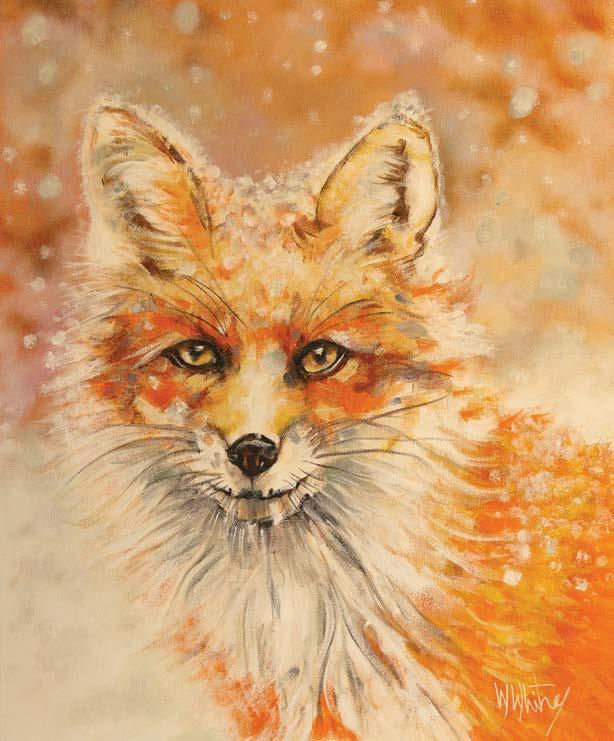

Paintbrushes just seem to belong in Wes Whitney’s hands.

The 69-year-old Fort Worth, Texas, native was born into an Air Force family, which allowed him to see the world at a young age. He lived in Germany, Puerto Rico and in five states, though Covington was always viewed as something of a home base. Whitney’s grandparents moved to the area in the 1970s, and he followed suit in 1995—the same year the Atlanta Braves won their first World Series. His love for art accompanied him wherever he went.

“I’ve basically been painting most of my life,” he said. “My family says I was born with a paintbrush in my hand. I put painting on the backburner for my job. I was a graphic designer for over 45 years. When I retired, I returned to painting full time.”

Whitney did not have to search far and wide for inspiration when he was asked to provide the cover for this issue of The NEWTON Community Magazine. “I love painting wildlife and tried to think of wildlife that’s indigenous to the local

area,” he said. “We’ve had a family of red foxes in the woods in our backyard in the past, so I picked a red fox. Being the winter issue, I put it in a snow scene.” Red foxes, which weigh between eight and 14 pounds, can be found in various habitats across Georgia, including forests, open woodlands and in urban and rural neighborhoods. Whitney spent a total of 12 hours across three days on the painting. “Some paintings,” he said, “just flow better than others.” Some of Whitney’s art can be viewed on display at the Southern Heartland Gallery on The Square. A more complete collection of his work can be found on his website at weswhitneyart.com.

“I paint for the love of it,” he said. “I like to sell paintings, but it’s not a motivating factor. I don’t like to call it a hobby. It’s more just part of my life now.”

A special thank you to Wes Whitney for providing the artwork forthe 2026 winter cover of The NEWTON Community Magazine.

We had the honor of sharing Gary Price’s remarkable story in the 2019 fall issue of The NEWTON Community Magazine. I met him back in November 2019, and I admit, I was intimidated at the time. Up to that point, I’d been nervous to talk with veterans. How could I relate to a Marine, a Vietnam War veteran, a three-time Purple Heart recipient? I have never served in any branch of the military.

Gary’s story stuck with me. He allowed me to see into his time in Vietnam and the impact it has had on his life through images and stories. When Gary talks, he doesn’t mince words. It’s a bit jarring at times, but after seeing and hearing what he has been through, I believe he has earned the right to talk however he wants.

A couple months ago, I had an idea about an art project I wanted to do. That’s when Gary returned to the forefront of my thoughts. I found a way to relate, show my gratitude and hopefully honor him. Most importantly, the project allowed me to reconnect with Gary. It included a few car rides to visit him with my best friend, Scott Fuss, time at peace to be creative and the experience of bringing some joy to a man who has endured so much so that I can be free.

I’ll never forget Gary Price, whose smile is burned into my memory forever.

Have a great day today.

Scott Tredeau

Stories by Kari Apted

Dr. Judy Greer became the first full-tenured female professor at Oxford College and retired after 33 years with the school. At the age of 90, she remains a source of wisdom for former students and an active force in the Oxford community, having lived there for nearly seven decades.

by KARI APTED

Faith, family, fortitude and fitness: words that define the wonderful life of 90-year-old Dr. Judy Greer. She was born in Detroit in 1935, the second daughter of Jamie and Odessa Greer. Her parents were raised in Georgia as farmers. However, after a devastating boll weevil invasion destroyed the cotton industry, Jamie joined dozens of other young local men who decided to move to Michigan to work in the new automobile industry. Odessa died when Greer was just 2 years old.

“My only sister, Doris, was eight years older than I, but my mother was one of seven girls and three boys,” she said. “One of her sisters, Mabel, lived in Cusseta—a small town near Columbus and Fort Benning—and never had children, so a year or two after Mother died, Daddy moved us back down here to live with Aunt Mabel and Uncle Bill.”

Bill and Mabel Zachry raised the girls while Jamie took an opportunity in Florida to work at a new bulk plant for gas and oil production. He visited his daughters often, and they spent summers with him in Florida. Greer recalls a happy childhood, filled with days spent almost entirely outdoors.

“I went hunting with Uncle Bill. I shagged golf balls for him, climbed trees,” she said. “I was a tomboy, and it didn’t bother me a bit. I was never told there was anything I could not do, unless it was unsafe. I don’t think that I would’ve been labeled as a child who needed Ritalin, but I was active all the time.”

Greer even learned to drive when she was 12. Another favorite childhood memory was walking to downtown Cusseta to visit everyone. “I’ve always been oriented toward activity wherever

I was, physical and social activity,” she said. “It took a town to raise a child, and Oxford was also like that when I moved here. Kids could play anywhere. I used to say that you could safely play a game of marbles on Emory Street, but of course, you can’t do that anymore.”

Though she was always naturally gifted in fitness and sports, growing up in Cusseta limited her access to athletics. “We did not have many organized sports in the community or in high school,” Greer said. “We had basketball and some softball but not much.” Basketball was her favorite sport—until she tried tennis. “I never saw a tennis court until I went to LaGrange College in 1953,” said Greer, who attended the school on a work-study program in physical education. While pursuing a bachelor’s degree in English and history, she took lessons to learn to play tennis. “I found out that I liked tennis a lot. Because I had a lot of natural ability for movement, I picked it up very easily, but I had to relearn some of my strokes, which weren’t altogether efficient,” she said. “I had to reteach myself how to play tennis so I could teach others.”

Greer was a serious student who worked hard to fund her own education. During the summer, while her friends went to camp or the beach, she worked at a cattle farm owned by her aunt and uncle in Cleveland. She also worked as a resident assistant on a dorm floor with 16 girls, including the daughter of Virgil Y.C. Eady, the dean at Oxford College. While Greer was visiting the family one weekend, Eady asked her what she planned to do after college. When she told him she was undecided, he invited her to come to Oxford. The school had only been open to female students for four years, but it had reached the point where it was necessary to add a woman professor to the physical education department.

“I came to Emory at Oxford to teach in 1957,” Greer said. “At the time, this was predominantly a men’s college. There were only 40 women in the women’s residence hall.” Eady initially offered Greer a one-year appointment, with the caveat that she must begin working toward her master’s degree. She accepted, and an Emory legend was born. Greer earned her master’s from Auburn University in 1961 and left Emory to teach at Winthrop

College, a four-year program in South Carolina. “Teaching at Winthrop meant I could teach physical education theory, as well as activity courses,” she said. Greer returned to Oxford in 1966 and stayed at the school until her retirement in 1996. She took a two-year leave of absence to earn her doctorate in education, physical education and higher education from the University of Georgia. “My dissertation at UGA was a biographical study of women who had started the women’s physical education program there,” Greer said. “I became interested in the history of sport. I didn’t have as much interest in the scientific part of movement. I was interested in the people who brought physical education into the colleges.”

Greer threw herself fully into her role. “I taught dance, volleyball, badminton and swimming. In many instances, I had to relearn [techniques] myself, but I didn’t spend as much time on them as I spent on tennis,” she said. “Our health and PE division didn’t have a big budget, so we had to cut a lot of corners for equipment and travel, but our intramural program was always so strong. Every student did something, and there

were tests and grades.” Greer commended Emory’s philosophy that athletics were meant for all and worked to involve the community as much as possible. She was instrumental in creating women’s and men’s tennis leagues, running tennis summer camps for kids and hosting women’s and mixed doubles tennis tournaments. Although her students called her Coach Greer, she always considered herself more of a teacher than a coach.

“The fact that you can open another person’s mind to something that they had never had any inkling of before, and you see the light come on or the ball go over the net, that sort of thing, that’s pretty exciting,” she said. Greer also enjoyed mentoring new female faculty members as their presence grew on campus. Many of them became close friends, with their children becoming like nieces and nephews to Greer. She still keeps in touch with many of them. “I always had a circle of friends in the community,” she said. “Very few faculty members lived in places other than Covington, and many lived in a row of houses on Dowman Street that’s still there today.”

Greer, a member of Allen Memorial United Methodist Church since she arrived in Oxford, never married or had children of her own, but she has no regrets. Friends often encouraged her to adopt a dog to keep her company, but she disagreed. “I’ve always loved animals,” she said. “My Uncle Bill raised and trained bird dogs, so I was around dogs all my life, but I didn’t have time to take care of them.” If the walls of her home could speak, they would tell of countless student visits, as they dropped in to hang out with a popular professor who never seemed lonely and dispensed sound advice. Greer has always been involved in the lives of her many nieces and nephews, and framed photos of their times together fill her home.

Travel was another significant part of Greer’s DNA.

“I’ve been to three Olympics: Munich, Barcelona and Atlanta,” she said. “I traveled through Europe over nine weeks one summer. I’ve been to Wimbledon twice, to the French Open and the U.S. Open. The only major tennis event I’ve not gone to is the Australian Open.” In recent years, Greer has had to pick and choose the activities in which she can participate, but she does her best to remain active with her large extended family. Many of her first cousins live nearby and gather for Thanksgiving, as well as for the Greer family reunion held every other Fourth of July.

When Greer walked off the tennis court on her last day at Oxford College, she was struck by a thought: “Where has the time gone?” Thirty years had passed far too quickly. “As I look back on my life, everything I was involved in was always directed toward the betterment of the school and the county itself,” Greer said. “I’ve always been interested in folks and wished that everything would be alright for all of them, at least as right as everything has been for me. I have had a blessed life. I can’t imagine living anywhere else.”

“I was never told there was anything I could not do, unless it was unsafe.”

Dr. Judy Greer

/hyoo mil dē/

noun: the quality of having a modest view of one's value or importance. e

by KARI APTED

When I arrived to interview Dr. Judy Greer, she stepped out on her porch and held the front door open for me. Her brilliant blue eyes and warm smile were as welcoming as her words, inviting me into a home filled with antiques and framed family photos. Once we sat down to talk, the conversation flowed freely, as it often does between southern women. It was as if we had known one another for years rather than moments.

The professor emerita and retired tennis coach showed me a postcard from Oxford College, inviting people to her 90th birthday party in September to celebrate an “Emory legend.” The dictionary defines a legend as “an extremely famous or notorious person, especially in a particular field.” Greer’s quiet humility made it clear that she never sought the spotlight. Ironically, that’s part of what makes her legendary: how she has simply and steadily lived a life of integrity while deeply caring about the people and resources entrusted to her. However, she’s far from an ordinary

person. After all, ordinary people don’t have buildings, scholarships and tennis courts named after them.

Her party was held in the Greer Forum, an expansive social area in the student center that includes an event stage. It was named for her by an alumnus. “Since retirement,” Greer said, “I’ve been very fortunate that people have honored me one way or the other.” Her face lights up when she talks about the Judy Greer Scholarship, another gift to others that bears her name. It was started in 1995 with $25,000 donated by students from Oxford’s class of 1959. “Every 10 years,” Greer said, “we have a formal event to raise money for the scholarship. As of now, between 50 and 60 students have received it. It’s grown wonderfully.” The tennis courts at LaGrange College—her alma mater and the first place the smalltown girl ever saw a tennis court—now bear her name, too.

A sampling of her awards and honors includes an honorary degree from LaGrange College. She became the Atlanta Metro YMCA Volunteer of the Year in 1991 and later served on the founding board of the Covington Family YMCA. Greer was inducted into the Emory Sports Hall of Fame in 1994.

The Covington/Newton County Chamber of Commerce awarded her the

R.O. Arnold award in 2004 for her outstanding community service. She has been recognized by the Points of Light Foundation for her work with senior adults, and in 2019, she was presented with an Outstanding Georgia Citizen certificate honoring “Women Sports Trailblazers” by the Georgia Commission on Women. The Wesley Woods Foundation honored her among its first all-woman group of Heroes, Saints and Legends in September. Other recipients included Billye Aaron and Virginia Hepner.

“All of this is only to say that cumulatively these things have happened,” Greer said. “I didn’t realize I was as involved as I was. I certainly didn’t think any of that was coming my way. I’m very grateful for my life and thankful I’ve been able to be as active as I could be.”

After a tour of her home, where she showed me various photos, awards and tennis memorabilia, it was time to go. Thinking on the drive home, I came to a realization. Despite all the accolades, if you were to ask Greer about her favorite titles, she would likely say “aunt,” “coach,” “teacher” and “friend.” Whatever you choose to call her, Greer’s positive impact on Oxford College, LaGrange College, Newton County and beyond will last for generations.

Addiction, violence and loss once defined Myles Lance. Prison became the place where he found faith, purpose and transformation, along with the desire to reach out to others battling the same demons.

by KARI APTED

Myles Lance had never experienced physical pain like this before. He was in prison—again—and a gang fight had resulted in a cracked jawbone. The injury left him in excruciating pain for days, unable to eat and only able to relieve his thirst by gingerly dribbling water into his swollen mouth. It would be nine days until he had surgery, followed by many more weeks of healing with his mouth wired shut. Lance admits it should have been the turning point in his life.

“I wanted to do better,” he said, “but I wasn’t willing to do better.”

Lance’s life story is a remarkable cycle of wrong choices, new opportunities and the pull of addiction constantly proving stronger. Born in Decatur in 1991, he was the youngest of four children. His father was an alcoholic, but he always provided for his family. “He was a good man,” Lance said, “but he didn’t know how to regulate his emotions.” Lance’s older brothers had a negative influence on him as a child, teaching him how to fight and taking him along to break into houses and cars. The family moved to Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, during Lance’s elementary school years. School was a challenge. He stuttered, and kids called him “M-m-m-Myles.”

“I had a smart mouth,” Lance said. “I got kicked out of public school in fourth or fifth grade and went to a Christian academy through eighth grade.” That was where the first seeds of faith were planted in his young mind. However, it was also where he started selling drugs. The young skateboard fanatic eventually landed back in public school, befriending other skaters who also used drugs. “I started with weed and drinking, then we would steal cough medicine from stores. That led to bigger and harder things, like acid and ’shrooms,” he said. “That lasted until 11th grade, when my parents suddenly decided we were moving back to Georgia.”

Lance’s lawlessness increased. His first arrest was for stealing a car. He only received probation, and his family relocated to Covington. “I hated it. It was so country,” he said with a laugh. Lance missed his high school graduation because he was in jail.

“I was running from my problems but starting to get caught,” he said. Lance got his GED and moved back to South Carolina. When he was 19, during a mushroom trip, Lance believes the Lord spoke to him. “He told me I had a calling, that I would be a preacher one day,” he said. “I said, ‘No way. Never me.’ I got into New Age spirituality and witchcraft instead.” After returning to Georgia, Lance got busted for drug and stolen gun possession. While fighting that case, his best friend was murdered when a gun purchase went wrong. “He died in my arms,” Lance said through tears. Survivor’s guilt followed.

“By the grace of God, I didn’t get shot,” Lance said. “My friends said it should’ve been me and abandoned me. I felt alone. It was like I was in a trance for months. I had a dream where Alex came to me and said it was OK, [that] it wasn’t my fault, [that] he loved me and to take care of my mother.” Lance was puzzled by the last part, until his father died the following year. A year later, his cousin committed suicide. “That’s when my heroin habit started,” Lance said. “I was young. I was angry. I didn’t understand. I fell out with my siblings. I became a mean, malicious person, and that led to a lot of risky behaviors: drunk driving [and] using heroin, meth and cocaine.”

Lance moved to Colorado, where his heroin habit worsened. He later returned to Georgia to live with his mother, but she had to put him out after a month. Lance’s addiction grew to the point that it was incompatible with steady employment, and he entered a years-long cycle of repeated drug sales, fights, arrests and jailtime. His mother secured a restraining order against him. “She said there was a new edge about me that was scary after being in prison, surrounded by evil,” Lance said. Rockdale County’s drug court tried to get him into a recovery program for months, but he would not commit.

(L-R) CAROLYN KELLER, SAMMY KELLLER, KEITH BRITTON, MYLES LANCE, KYRAN LEONARD, TONI TOMPKINS, SHARAE TOMPKINS, ELDER PALACIOS AND CALRETHER LANCE

“My interview for admission was on Aug. 2,” Lance said, “but on Aug. 1, I blew a bunch of money on fentanyl and crack and got busted.” He found himself back in prison. “I detoxed for two weeks,” Lance said. “I didn’t eat for 10 days, but I turned my back on God again and got caught with dope. I was sent to the hole and resentenced. But the Lord was with me. I wrote the judge a letter about my drug problem and needing help. I was very honest and apologized, and it had to be God. The judge suspended everything I had previously done and gave me three straight years in prison. When I went back, I did good for the first couple of days.” Prison, however, was rampant with gang and drug activity, and Lance fell back into his old ways.

“One night I sat down with all these drugs spread out before me to get high,” he said. “I prayed a prayer that I didn’t realize was one: ‘Lord, I can’t do this on my own. Can you please take this from me?’ The next day, I got stabbed bad in a gang fight.” Lance began earnestly seeking the Lord. He read a children’s Bible storybook from front to back and started picking up copies of “Our Daily Bread” and other devotionals. “I was like a sponge soaking up God. My eyes and ears were opened,” Lance said. “A Fugees song called ‘Ready or Not’ kept playing in my mind, and I kept writing ‘ready or not’ constantly. The more I decreased, the more God increased. I was born again, and prison was my refinery.”

Lance began leading prayer meetings and devotionals while incarcerated, earning unexpected respect from everyone, including gang members and people of other faiths. When Lance left prison for the last time, he thought about how his mother always called him “Jonah” in reference to his running from God. “I remembered a Bible verse, Jonah 2:1–2: ‘In my distress I called to the Lord, and he answered me. From deep in the realm of the dead I called for help, and you listened to my cry,’” Lance said. “I kept writing ‘Ready or Not’ because I realized, whether you’re ready or not, all you’ve got to do is make the first move.” He met Toni Tompkins, a woman with a similar story of struggle and redemption, and they started a Facebook page called Ready or Not Ministries. “It has grown into a full-blown ministry,” Lance said. “Through our ministry, we provide services for the homeless and the hopeless and can

help people get into rehab and acquire insurance if they have none.” Lance and Tompkins are now engaged, and he considers her son, Kyran, his own. “We were dope dealers,” Tompkins said. “Now, we’re hope dealers.” The couple works at Twin Lakes Recovery Center in Monroe. They teach Sunday School to kids and teens at New Life Praise Center in Covington.

“In January,” Lance said, “we will be starting growth groups at New Life to help people grow through what they’re going through.” Tompkins elaborated further. “They are for anyone who’s been through any type of trauma who just needs a place to get the Word,” she said. “They can come as they are. We meet them where they’re at.” It represents another step in Lance’s recovery. “God has shown us the purpose for our pain,” he said. “I don’t believe in bad days. Even when I was incarcerated, I was free. Every day is a new chance to spread love.”

“God has shown us the purpose for our pain.”

Myles Lance

“I’ve often prayed for God’s will to be done in my life, but when He begins to move, I don’t always understand it right away.”

Cullen Johnson

As students search for truth in a hostile world filled with temptation, a wave of baptisms revealed the power of planting seeds in fertile, eternal soil.

by CULLEN JOHNSON

“He said to his disciples, ‘The harvest is great, but the workers are few. So pray to the Lord who is in charge of the harvest; ask him to send more workers into his fields.” — Matthew 9:37-38

The last place I ever thought I’d end up was back in high school. It was August 2017—just two months after graduating from the University of Georgia with a bachelor’s degree in business administration—and there I was, walking the halls of my old school again, this time as a teacher. I had attended Young Americans Christian School in Conyers and graduated with the Class of 2013. As a recent college grad, returning to high school wasn’t exactly part of my plan. However, God has a funny way of opening doors that lead to something far greater than anything we could dream up ourselves.

At Young Americans, every student is required to take Bible classes and attend weekly chapel. My job was to teach those classes and help lead those services. The first few months were tough. I was wrestling with my purpose and questioning why God had placed me there, especially in a role I never asked for. Even in my confusion, God was working behind the scenes.

One day, as I was teaching my sixth-grade Bible class, a quiet girl in the back raised her hand and asked, “What is baptism?” I could sense that this was a divine moment. I explained, as clearly as I could, what baptism means and what it represents. Then I asked her, “Do you want to be baptized?” She said, “Yes.”

Feeling led, I turned to the rest of the class and asked, “Does anyone else want to be baptized?” To my surprise, hands shot up all over the room. It was in that moment I realized exactly why God had placed me there.

During my first year of teaching, I had the opportunity to baptize around 30 of my students. Over time, even more made that same decision—through chapels, retreats and everyday classroom conversations. I’ve often prayed for God’s will to be done in my life, but when He begins to move, I don’t always understand it right away. Looking back, I see now that He was teaching me what it truly means to “go and make disciples of all nations.”

The harvest is still great, and the workers are still few. Students today are searching for truth more than ever before. In a world that tells them to “try this, smoke this, drink this,” we need more workers—people willing to till the soil, plant the seed, nurture the crop and gather the harvest God has prepared. Too often, students are pushed to chase careers that store up earthly rewards. What we need are workers who will inspire them to pursue lives that store up eternal ones, encouraging them not to become who the world wants them to be but who God created them to be.

Cullen Johnson serves as the youth pastor and worship leader at Dovestone Church. For information, visit dovestonechurch.com.

Inspired

by her grandmother’s legacy, Jamaica native Paulette Robinson Morrison honors a lifelong call to serve by bringing meals, compassion and ministry to Covington’s disadvantaged.

by MICHELLE FLOYD

Some grandparents pass down jewelry, furniture or family recipes to their grandchildren. Paulette Robinson Morrison’s grandmother passed down a way of life.

A few years ago, Morrison started looking for ways to help community members in need after having moved to Covington in 2017. She had retired from a lifelong career in nursing and wanted to find another way to care for those in need.

“This is a part of me,” said Morrison, who worked as a nurse, a phlebotomist and in home health over the years in Massachusetts and Georgia. “I was gifted for that. That’s all I want to do is help people.”

She often thinks back to life in her native Jamaica, where she grew up with her family and was partially raised by her grandmother. She was kind because she liked feeding all of the people who came to her,” Morrison said. “Whatever food she had, usually from the garden, she would split it up, no matter how small. She helped everyone, especially children. Kids would come over to the house to play, and she wouldn’t make them go home. If she was preparing a meal, she would make sure to give them some, too.”

Whenever her grandmother cooked, Morrison and her family would provide food to the pastor across town. She remembers taking him traditional Jamaican meals with chicken and rice for breakfast and dinner, along with foods from her grandmother’s Irish background and her grandfather’s African heritage.

“I get the passion from there,” said Morrison, who moved from Jamaica to Boston with her mother near the turn of the century. She has now found an avenue through which to assist her current community whenever she can. “That’s my assignment,”

said Morrison, a minister through Sacred Heart Church of Jesus Christ International, which is based in Jamaica and has plans to open a branch in Covington. “I see people around town, and I would offer my help.”

Morrison in 2023 noticed homeless and in-need community members of all ages around the Repairers of the Breach Thrift Center on Washington Street in Covington. At the time, she lived with one of the volunteers who told her about the facility, which provides food, clothing and other items to the disadvantaged. Morrison started visiting the center each week to feed people out of her Chrysler van—rain or shine, hot or cold.

“When I do this, I’m not looking for anything. I’m helping the less fortunate. That’s what the Lord has for me to do.”

Paulette Robinson Morrison

“I don’t want food to go to waste, so I would just go and give it to them,” said Morrison, who found her way to Georgia in 2012, first in Snellville and then in Lithonia. “It makes me feel happy that I can do that.” Sometimes, she would bring pizzas and drinks to them, and other times, she would offer items from her pantry like fruit bars. Morrison has even made them meals like sausage, bacon, grits and biscuits. “They love grits. They would take it, and they’re happy. They’re not rude,” she said, adding that there are usually 15 or more people of all ages each time she visits. “I have a passion for doing this. When I do this, I’m not looking for anything. I’m helping the less fortunate. That’s what the Lord has for me to do.”

Morrison has not yet had a chance to make any Jamaican meals for those she served, but she hopes to do so one day. At one time, she would try to take food weekly. Now, she brings it around town whenever she can. Usually, Morrison collects food on her own, but sometimes, she gets assistance from her family or members of her church. She has even included a friend visiting from Jamaica in her quest to feed those in need around Covington.

“She’s doing a great job, and I encourage her to continue it,” Deany Forbes said. “I do the same in Jamaica. I make food and bring it out. I make cakes around the holidays and take it to the homeless on the streets or to the church.”

Repairers of the Breach CEO Shirley Smith suggests that anyone interested in assisting with meals should contact the center to get on the schedule to drop off donations. Individuals, churches and businesses can sign up throughout the year. “We welcome anybody who wants to serve,” Smith said. The facility hosts a warming shelter, food bank, showers and sitting areas, in addition to boosting the community by providing meals throughout the day, along with necessary food supplies and other items. “We couldn’t do it without people helping,” said Smith, whose facility reaches out to the homeless, elderly and struggling families in the area. “Covington is great about volunteering. We need all the help we can get.”

Morrison revealed that her three children—Melissa McIntosh, Phillip McIntosh and Neckia Madden, all of whom live nearby— and five grandchildren assist her on occasion with rounding up food and hopes they will continue assisting those in need in their own communities. Eventually, she plans for her ministry to find a building from which she can serve others.

“We pray with them and encourage them,” said Morrison, who shares the Bible with the needy whenever she can. “We don’t know what will happen to us one day. We all go through things. I never know what my day will be like one day. I will continue to help.”

Stories by Chris Bridges

Kendarrius Spear’s life may have ended in a 2024 shooting, but his mother made certain the former Alcovy High School basketball star’s legacy would carry forward through a nonprofit organization that bears his name and empowers youth with the same drive and heart he embodied.

by CHRIS BRIDGES

Kendarrius Spear had so much ahead of him.

The Alcovy High School graduate was well on his way in life. With his positive attitude, insatiable work ethic and unflinching desire to excel in all endeavors, Spear was set to make a lasting mark on his community and those who had the pleasure of knowing him.

Everything changed on June 25, 2024.

Spear’s life was tragically cut short when, in the cruelest of ironies, he was shot and killed during a robbery in Lithonia while home from college for the summer. He was 19 years old. Three people were reportedly involved in the incident. However, Spear’s legacy of dedication, kindness and community spirit lives on through the KD Strong Foundation, which was formed in his honor. A driven student and a standout athlete, “KD” at the time of his death was attending Stillman College in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, where he was passionately pursuing his dreams on a full academic and athletic scholarship. Kennethia McKibbenGay knew Spear better than anyone. As his mother, she developed a close bond with her oldest child from the start.

“When he was born, I was still 15,” she said. “I was still a kid myself. We grew up together, so it made our bond even stronger. We were not only mother-son but also in ways, we were brother-sister. KD had a rare kind of kindness. If he wanted to do it, he would set his mind on making it work. He was going to succeed no matter the task.”

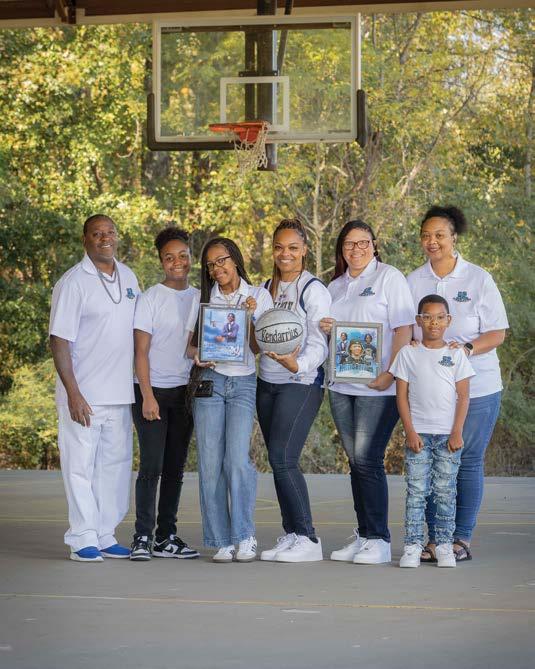

Spear excelled in basketball and developed a love for the game early in life. Not long after his death, his family members took to the court to commemorate the new non-profit organization that now bears his name.

“This foundation is dedicated to keeping KD’s legacy alive by supporting young people in our community, helping them reach their potential and inspiring others like KD inspired us,” Eastside High School athletic director Champ Young said at the time.

“The KD Strong Foundation will provide resources, mentorship and opportunities for young men and women to grow, achieve and make a positive impact on the world around us. Though we feel his absence deeply, KD’s legacy is far from over.”

The KD Strong Foundation’s vision: To create a community where young people have the support, resources and opportunities to succeed, regardless of the challenges they face. By connecting youth with mentorship, academic guidance and essential resources, it aims to transform lives, build futures and foster a spirit of giving back. The nonprofit organization honors Spear’s life by empowering young individuals to achieve their full potential through education, athletics and community engagement. The KD Strong Foundation focuses on providing resources, support and opportunities that foster personal growth, resilience leadership and a commitment to non-violence. Through its programs and initiatives, it strives to inspire and uplift others, ensuring that Spear’s spirit of excellence, kindness and dedication continues to make a positive impact.

The foundation will award a scholarship to a member of the Class of 2026. Several different community activities are associated with the organization, including a trick-or-treat event and a push to donate community giftbag boxes to provide food during the holidays. The KD Strong Foundation adopts a family each year, although sometimes the mission spreads due to the need.

“Last year, we planned to adopt one family,” McKibben-Gay said, “but we ended up with four.” While she has formed a team to assist her with the foundation, Spear’s mother remains the driving force behind it.

“KD always had been very friendly,” she said. “He had the ability to fit in with any group of people he was with. He could walk into room of complete strangers and be completely at ease with everyone there. There are people in different states he connected with. Once, he met someone who said he had no aspirations to go to college or to do anything. He knew Kendarrius because my son was friends with his older brother. Their meeting made him want to go to school.”

The KD Strong Foundation also provides help to those in assisted care homes. In addition, it held “Kicks for a Cause” at Denny Dobbs Park in Covington, where shoes were collected for children in need. More than 150 people attended the event, and 213 pairs of shoes were donated to young people. Spear’s family believes it would have made him proud. Jakai Newton, a lifelong friend who plays basketball at Georgia State University, provided further testimony to the impact Spear had on others. He was the driving force behind “Kicks for a Cause” and presented a $500 check to the foundation.

“It turned out perfect,” McKibben-Gay said.

Spear served as a shining light in the lives of all who knew him. Born to McKibben-Gay and Demaurious Spear on Nov. 16, 2004, he brought joy to his family, including his siblings, Jayden and Kennedy Daniel, his grandparents, Audrey and Anthony Freeman, and his aunt, Britsheny McKibben Bolaji, all of whom played vital roles in supporting his journey. Family members credit several mentors with shaping him into the young man who touched so many others: his uncle, Michael Smith, his cousin, Johnathan Hogan, and his stepfather, David Gay Jr., were pillars in his life, instilling in him the values of integrity, resilience and compassion. Their influence and the unwavering love of his grandparents and aunt helped Spear develop into a leader and a role model, on and off the basketball court.

Even during the immediate aftermath of her son’s death, McKibben-Gay wanted his name to live on. She made that hope possible through the foundation she formed and operates.

“Really, the most important thing was not about honoring his legacy,” she said. “He didn’t have any children, so what was driving us was the mission of empowering and uplifting the youth. That was something that was so important to him.”

For information, visit kdstrongfoundation.com.

(L-R)

ANTHONY FREEMAN, MADISON CARTER, KENNEDY DANIEL, KENNETHIA MCKIBBEN-GAY, AUDREY FREEMAN, QUMARI MCKIBBEN, BRITSHENY BOLAJI

“He could walk into room of complete strangers and be completely at ease with everyone there.”

Kennethia McKibben-Gay

Stories by Phillip B. Hubbard

Bradley Patton teaches golfers of all ages to elevate their respective games. As the director of instruction at Ashton Hills Golf Club, his coaching style blends curiosity and connection with a lifelong passion for progress.

by PHILLIP B. HUBBARD

Bradley Patton was always a competitor at heart, and he channels that part of his personality through golf—a sport he first picked up at 8 years old. Outside of competition, he helps other players improve their games as the director of instruction at Ashton Hills Golf Club in Covington. In this role, the Dover, Delaware, native heads up the club’s golf academy and teaches in various capacities. At the heart of Patton’s passion lies his desire to see the sport he loves continue to progress.

“I really try to grow the game of golf through instruction and helping people from all abilities and levels get better at the game, whether it’s 4-year-olds all the way up to 80-plus-yearold golfers who maybe never touched a club before,” Patton said. “It’s a great way to grow this great game.”

Golf has taken Patton to countless courses all over the country. He played in high school, then at the University of Delaware before he graduated in 2005. He went on to attend the Golf Academy of America in Orlando, Florida, where he earned an associate’s degree in golf complex operations and management. Patton then added a master’s degree in kinesiology, with a concentration in coaching education, to his resume in 2025. He also now holds the distinction as a PGA Class A member in the state of Georgia.

While attending The Golf Academy of America, Patton was afforded a glimpse into his future endeavors. A person approached him during a practice session at one of the tournaments in which he was competing and struck up a conversation, informing Patton that he had not played in roughly six months. Patton provided a few pointers, then learned the anonymous golfer had broken 100 by shooting a 93. Rather than focus on his own round on the way home, Patton instead pondered his impromptu student’s performance.

“I ended up talking to him for two hours. I wanted play-byplay,” Patton said. “I wanted [to hear about] every shot he hit, and he was so excited. His enthusiasm for how well he did … I was more excited for him than I was for how I played, so I talked to an advisor I had at the golf academy and he was like, ‘Well, looks like your career is in coaching.”

Patton today finds himself nearly two decades into coaching others. Every day, he witnesses someone enjoy a light-bulb moment. He compared the complexity of the golf swing to teaching a young child how to drink out of a cup without a lid on it—something Patton currently experiences through his 3-year-old daughter.

“I’m going to continue to learn just so I can improve my coaching and help my students a lot better.”

Bradley Patton

“A lot of times, there’s success,” he said. “Other times, there’s, ‘OK, Lily. Let’s go ahead and change your shirt.’” Watching his students realize how the lessons are improving their technique has proven to be the most rewarding part of his job. “What’s more important to me in a session is that if they can feel their old movement pattern and see that [it] was wrong or incorrect and why it was incorrect,” Patton said. “That’s going to help them with the learning, and they’re going to get the motion down a lot better.”

Education is something of a tradition for Patton on both sides of his family. His father, Robert, was a physics professor, and his mother, Judy, was an elementary school teacher. Patton was one of his father’s students, not in the classroom but on the golf course. In fact, Robert passed his passion for the game onto his son. At an early age, Patton played baseball and soccer all year while also competing as a swimmer. After his family moved closer to a golf course in Delaware, Patton began going with his father. Patton shared that he was “hooked after my first putt” at Maple Dale Country Club. Strengthening his relationship with his father only added to his initial interest.

“He was very active, but he was always on the sidelines, and he was there supporting,” Patton said. “Then this is something that we could be close together, and he was teaching me how to do it. It was definitely a bonding experience with my dad. That was the biggest thing that stood out to me: It further solidified our relationship, and we got a whole lot closer through golf.”

In addition to his father, Georgia-based golf instructors Tom Losinger and Charlie King were pivotal mentors in Patton’s development as a player and coach. Other stops in his coaching journey included GOLFTEC Philadelphia, the Flagler Golf Academy and The Oaks Course. Patton has earned 10 certificates along the way and considers himself a skills-based instructor who helps golfers fine-tune a particular skill they want to refine. Patton still plays competitively on occasion and participates in the Pro-Pro Championship at Sea Island in St. Simons every December. Inquisitiveness remains at the forefront of his pursuits.

“I learn from my students and watching them learn how to move,” Patton said. “Hopefully, they learn a lot from me, too. I definitely learned a lot from my students but also from the PGA through the PGA of America, as well as the master’s degree I just completed. I always liked learning. I’m going to continue to learn just so I can improve my coaching and help my students a lot better.”

For information on Ashton Hills Golf Club, visit ashtonhillsgc.com.

Revisit some of your favorite stories from our past winter issues available on our website.

Stories by Phillip B. Hubbard

Thomas Floyd’s service to the Georgia Department of Natural Resources as a wildlife biologist spans decades, and his research on the elusive amphibian now fuels statewide ecological awareness efforts.

by PHILLIP B. HUBBARD

Thomas Floyd was in fifth grade in 1987, and he was already interested in natural resources. He took a hunter’s education course—a requirement to receive a hunting license at the time—at the Walton Fish Factory, now home to the Wildlife Resources Division. He remembers his father, Don, telling him he might someday work for the Department of Natural Resources. “I scoffed at it and told him that I thought he was wrong,” Floyd said, “and turns out, he was very right.”

Floyd now finds himself 23 years deep into his role as a wildlife biologist for the DNR. One of his specialties involves amphibians and conservation of individual imperiled species.

More specifically, Floyd studies and works with hellbender salamanders, the largest salamander in North America. Completely aquatic and with permeable skin, it is affected by pollutants. Floyd compared it to an “aquatic canary in a coal

mine, if you will, for aquatic ecosystems.” Cool, clean, clear, well-oxygenated waters in shade are the characteristics of the environment in which hellbender salamanders thrive. Typically, in Georgia, they can be found alongside trout. There are ways to maintain such conditions, according to Floyd.

“Water, river or stream buffers are key to maintaining healthy populations or healthy water quality through reduction in sedimentation and other inputs of other pollutants,” he said.

Floyd became interested in the hellbender salamander while completing his undergraduate degree from the University of Georgia’s Warnell School of Forest Resources. He took a natural history of vertebrates class that examined subjects from birds and small mammals to fishes, amphibians and reptiles. Thus, he continued exploring his fascination as part of his graduate degree studies at Clemson University, researching salamanders

“It’s just an incredible species to work with, and every time I capture one, I have a period of fascination while it’s in hand.”

Thomas Floyd

and other herpetofauna, reptiles and amphibians. The lack of data for the hellbender intrigued Floyd, too. “That’s really the impetus for initiating a long-term monitoring project for hellbenders: to develop a data set so that we’ll be able to have something to compare abundances and population statuses in the future with what we currently have today,” he said.

Several initiatives are underway concerning Floyd’s study of the hellbender salamander, one of them the result of a surprise encounter he had during his research. As part of the hellbender survey protocol, Floyd charted a particular stretch of stream that he had studied a handful of times prior to the summer of 2024. In that study, Floyd uncovered just the third documented occurrence of finding mud puppies—three of them, to be exact—along with hellbenders. “It’s odd to think when you’re surveying for something as rare as a hellbender that you could find something that’s probably considered to be [rarer], at least in Georgia,” Floyd said. Following that discovery, an initiative was launched to install

signage in portions of North Georgia that includes diagrams of hellbender salamanders and mud puppies to gather information from the public. Floyd believes finding mud puppies and hellbenders to be more common than many realize. “Occasionally,” he said, “I would think a mud puppy or a hellbender is caught on the end of a fishing line, and those are important observations.”

Some additional observations by Floyd: Hellbenders in Georgia are on the smaller end of the size range, and they undergo metamorphosis. Currently, Floyd is studying museum records and specimens from across the range while comparing them to findings in Georgia. He is also working on a manuscript to include adequate information to draw a definitive conclusion and publish a paper on the subject.

Floyd graduated from Newton High School as part of the Class of 1994, its final graduating class as the only high school in the county. Nothing about his upbringing especially influenced his decision to pursue a career path in wildlife biology, besides his involvement in

Boy Scouts. However, Floyd admitted he was “ignorant” concerning the significance of his hometown to wildlife. In fact, Floyd did not recognize until after his career began that he played in the same dry Indian Creek that Charlie Elliott once did. “It is ironic that Charlie Elliott is from the same area,” Floyd said, “and he’s so eminently important to wildlife conservation in the state.”

Much has transpired in Floyd’s life since his father foreshadowed his career with the Department of Natural Resources. In addition to his studies at Georgia and Clemson, Floyd became a certified wildlife biologist through The Wildlife Society in 2012. He has now invested more than two decades with the DNR. Nevertheless, Floyd remains enthralled with the hellbender salamander and embraces every encounter with the unique amphibian.

“It never gets old to find a hellbender,” he said. “It’s just an incredible species to work with, and every time I capture one, I have a period of fascination while it’s in hand. That’s plain and simple how I’ll characterize it.”

Stories by Avril Occilien-Similien

Bravery and Breakthroughs

With the unwavering support of her family, teachers and community, 8-year-old Kennedy Carlock proves that blindness need not be a barrier to brilliance.

by AVRIL OCCILIEN-SIMILIEN

Kennedy Carlock has already done something extraordinary at just 8 years old—she read her way onto the national stage. A third grader at the Newton County STEAM Academy, she recently earned top honors in the Apprentice Division at the 2025 Braille Challenge Finals, held on the campus of the University of Southern California in Los Angeles. It is the only academic competition of its kind for blind and visually impaired students, celebrating literacy, problem-solving and confidence in Braille. Out of more than 1,300 participants from across five countries, only 50 made it to the finals. Kennedy was one of them.

When asked what she loved most about the experience, she did not hesitate. “I liked making friends,” she said. “I’m feisty.”

That playful spark, accompanied by a grin, says everything about her. Kennedy’s mother, Katie, remembers how early the journey began.

“Kennedy started learning Braille when she was just 3 or 4,” Katie said. “We worked with the Center for the Visually Impaired in Atlanta through a grant to help kids start early, developing pre-Braille skills. That gave her such a strong foundation.” From there, Kennedy entered public school, where she met teachers who refused to let blindness limit her learning. “She had amazing teachers like Stephanie Piazza, who made sure she had everything she needed,” Katie said. “Then she met Miss Ann Summerson, who said from Day One [that] ‘she can do anything.’ And she meant it. She taught Kennedy the entire Braille code, even the Nemeth code for math.”

Summerson was the teacher who first encouraged Kennedy to enter the Braille Challenge—a move that set the stage for what would become one of the Carlock family’s proudest moments.

“From the start, we said, ‘She’s not going to miss out on anything,’” Katie said. “Blind doesn’t mean limited.” Each year, students compete in the regional Braille Challenge—Kennedy had done so for several years—but this was her first time qualifying for the trip to Los Angeles. She came close in 2024 but not quite close enough.

“She got first place at regionals, but the scoring system sent the student with the highest average score instead of the highest single score,” Katie said. “She was disappointed, but honestly, it just made her work harder. This year, she went all the way.” The experience in Los Angeles was less about winning than it was about belonging. “At her current school, she’s the only student who is blind,” Katie said. “At the Braille Challenge, she wasn’t the different one anymore. She was just Kennedy.”

That sense of connection meant everything. Surrounded by peers who use canes, read Braille and adore the same technology she does, Kennedy saw a glimpse of her own future, and it looked bright. She already had a strong support system in place.

“Kennedy’s success is a family affair,” Katie said. “Her grandparents, Jeff and Pam Dugan, are deeply involved, and her

cousin, Evie Baskett, is like a sister. We said from the start she wasn’t going to miss out. She rides rollercoasters. She’s in Girl Scouts. She’s a lunch reporter on her school’s news team. She even has a companion dog named Midnight from Dogs Inc., to prepare her for a guide dog one day.”

Kennedy’s village extends well beyond family. The Covington Lions Club has played a significant role in her journey, gifting her a smart Brailler when she was just 4 and later helping make the trip to California possible. They even had a Lions Club vest made for Kennedy with her name embroidered on it in Braille. The City of Porterdale went a step further, declaring a “Kennedy Carlock Day” in her honor.

“Her win isn’t just hers,” Katie said. “It belongs to every teacher, friend and community member who believed in her.”

Kennedy is not just a strong Braille reader. She loves technology and dives into multiple interests and hobbies. She uses an electronic Braille device called the Chameleon, which lets her type and read Braille simultaneously, loves writing stories and recently starred in a commercial for the American Printing

House for the Blind that demonstrated the organization’s new device: the Monarch. Kennedy is also a musician through the nonprofit Songs for Kids, which helps children and adults with disabilities record and perform original music. Between that, the Girl Scouts and her love for The Baby-Sitters Club book series, Kennedy’s calendar is full, her spirit even fuller. She will move up to the next Braille Challenge division in 2026, which means tougher reading passages, more difficult spelling and even stiffer competition. The Carlocks look forward to the experience.

“She’s determined and strong-willed,” Katie said, “but most of all, she shares her success. She knows how many people helped her get here, and she is thankful.”

From a quiet pre-K classroom to the spotlight of a national competition, Kennedy’s story involves perseverance, community and pure joy—the kind that reminds everyone that ability is not about sight but about vision. She hopes to break the stereotypes that often follow those who are visually impaired.

“We can do stuff,” Kennedy said. Her mother echoed those words with a proud smile and quiet conviction. “That’s exactly it. Blind kids are capable,” Katie said. “They may have to do things differently or use a tool or need you to give directions differently, but there is nothing they can’t do. Sometimes, the only thing that slows Kennedy down is that she’s 8.”

For information on the Center for the Visually Impaired in Atlanta and Dogs Inc. in Palmetto, Florida, visit cviga.org. and dogsinc.org.

“We said from the start she wasn’t going to miss out.”

Katie

Carlock

Stories by David Roten

Mother-daughter duo Nancy and Alexandria Schulz turned a lifelong love of travel and the outdoors into a soul-searching, 14-day pilgrimage across Portugal and Spain.

by

DAVID ROTEN

Nancy Schulz and her daughter, Alexandria, have enjoyed many outdoor adventures together over the years. Even so, they share slightly different versions of one of their first—a family vacation to Germany and Switzerland when Alexandria was just 9 years old and her younger brother was 7. “Mom marched us over this mountain 20 miles in the snow,” she said with a laugh. “Some [miles] in rain, some in snow,” her mother said, offering a good-natured protest. “We got lost,” Alexandria said. “We weren’t lost,” Nancy said. “We were in Interlaken.”

Since those early days, the daring duo has hiked—and sometimes snow skied—in numerous national parks in America and in such faraway places as Costa Rica, New Zealand and multiple countries in Europe. In the spring of 2025, they went on a hike unlike any they had taken before. More than a walk in the park, it was a pilgrimage on hallowed ground. The Camino de Santiago, or “The Way of Saint James,” is a network of caminos (ways, or routes) commemorating the travels of James the Apostle as he evangelized Spain. Every year, thousands of pilgrims come from around the world, taking one of many caminos originating from various points in Spain, Portugal, France and beyond, all leading to one destination in Galicia, Spain—the Santiago de Compostela Cathedral, the traditional resting place of the country’s patron saint.

Alexandria was the first to express an interest in going on the pilgrimage back in 2010. Nancy gradually warmed to the idea,

eventually asking her daughter to accompany her on the trip to commemorate her 70th birthday. The timing was right for 39-year-old Alexandria, who had begun to reevaluate a high-pressure career in consulting and tech while starting to reconnect with her “more creative and arts-focused passions.” Nancy did the research to formulate an itinerary and arrange for overnight accommodations on the Camino Portuguese, the second-most popular route on the Camino de Santiago. Alexandria took a sabbatical from her job and, along with her mother, focused on training and preparation. “You want to train walking for those distances in the gear you’re going to use,” she said. “I was testing out backpacks, hiking poles, socks, shoes. You learn how to handle your blisters, tape your feet.” Mother and daughter arrived in Porto, Portugal, and on May 10, they took the first of many memorable steps on their 14-day, 184-mile pilgrimage on the Camino.

Alexandria carried a backpack containing 15–20 pounds of supplies, including clothes, water bottles, foot care items, phone chargers, an emergency kit, protein, duct tape and Teva sandals for tired feet at day’s end. Nancy elected to have her pack, similarly stocked, transferred by porters from one overnight accommodation—primarily guesthouses and hostels—to the next. Both wore a scallop shell, the iconic symbol of the Camino. A Camino passport, stamped by participating business establishments along the way, would

enable them, upon arrival in Santiago, to receive the cherished Compostela, a certificate of completion of the journey.

Guided by GPS, Nancy and Alexandria pointed toes toward Santiago and pushed off. From Porto, the two followed the Litoral, Coastal and Central routes, tramping over cobblestones, boardwalk and woodlands. “Then, after we crossed over into Spain, we [went] on the Spiritual Variant, which is like the road less traveled,” Nancy said, “and it is spectacularly beautiful.” While on the pilgrimage, she made daily Facebook posts chronicling their Camino experience. An excerpt from May 22: “Despite its name, there are minimal shrines, religious symbols or churches on the Spiritual Variant. Instead, it is filled with the most stunning scenery we have seen thus far … challenging terrain, breathtaking vistas and brilliant hues of vegetation framed by an azure blue sky. We are almost alone on this trail except for the sounds of birds, roosters and baby goats. At one point, we encountered 10 horses grazing on the path. It was magical. Tonight we are staying in a monastery. Each day has been a mixture of wonder and tired feet. Both of us agree that today was the most exhausting filled with the most wonder.”

The trail is a diverse mix of coast and countryside, remote villages and larger cities. Yet every day was the same in its simplicity.

“You get up, eat, walk, eat a little more, go to the bathroom, shower when you get to your destination, sleep and then you do it all over again,” Nancy said. “It’s so simple,” Alexandria said. “All you’re accomplishing is that you need to get from here to there. It helps you to be really present.”

A whole economy has grown up around the trail, from hostels, restaurants, shops and entrepreneurial masseurs to Uber drivers and a host of others—all providing support to the thousands of pilgrims who pass by each year. Sometimes, needed help seems to come out of nowhere. “There’s a saying that ‘The Camino will provide,’” Nancy said. “There were several times where we would get lost and, all of a sudden, somebody would show up and say, ‘You go that way.’” When Nancy and Alexandria finally arrived at the tangible goal of every Camino pilgrim—the magnificent Santiago de Compostela Cathedral—it confirmed, in a surprising way, what they had already learned.

“This whole experience helped me understand how to live in the moment, to really appreciate nature and to appreciate how simple life can be if you just let it,” Nancy said. “When I

walked into the cathedral, I couldn’t even stay. I had to leave because it was so ornate, so opulent, so contrary to what I had felt for two weeks. It was a distraction.”

Though Alexandria had originally been drawn to the pilgrimage by a thirst for adventure, in the end, she had come simply seeking direction for the next chapter of her life. Somewhere along the Camino, she found it. “I just walked away with clarity of like, ‘I’m on the right path,’” she said. “I came back with a goal to do more art and really double down on that.” Nancy’s love of the outdoors, and deep appreciation of different cultures was more than enough to conquer language barriers and doubts of whether she could finish the walk. Now back in the real world, she strives to maintain some sense of the peace and simplicity she experienced on the Camino.

With one more backward glance, Alexandria recounted the moments leading up to the end of their pilgrimage. “Once we got to the point where we could see the steeple and we had to kind of wind through Santiago,” she said, “those final steps felt really special.” After rather miraculously bumping into a fellow pilgrim they had befriended days earlier, it was time to go to the cathedral and receive the treasured Compostela. Alexandria described what she called a shared “spiritual experience” with their newfound friend, Bernie. “We ended up walking into the square together with this stranger from Austria that we had met at the top of a random mountain,” she said. “That’s a very emotional moment, after you’ve come all this way, to then walk into the square together and you’re like, ‘There it is. We did it!’ It kind of takes your breath away.”

“This whole experience helped me understand how to live in the moment, to really appreciate nature and to appreciate how simple life can be if you just let it.”

Nancy Schulz

(NOV. 19, 1934-OCT. 3, 2025)

by BRIAN KNAPP

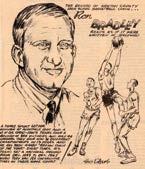

Word reached my ears on a Sunday morning in October that Ronald M. Bradley had completed his race after 90 years, 10 months and 14 days. And what a race it was. I sank into my chair for a few moments, then allowed my initial heartache to turn to gratitude after having been afforded the opportunity to get to know the man who had impacted the lives of so many people in my hometown.

Bradley made a name for himself long before I was born. He enjoyed a standout playing career as a multi-sport athlete at the University of Georgia, where he led the school’s baseball team to back-to-back SEC championships (1954–55), then set out on a remarkable journey from the bench that would span nearly half a century. Bradley started his coaching career at Newton High School, where he guided the boys’ basketball team to 430–68 record, 14 region titles and the 1964 state championship across his first 17 seasons. His run included a national record 129-game home winning streak that still defies belief. Bradley left Newton following the 1974–75 season and went on to coach at several other stops, including George Walton Academy in Monroe and Loganville High School in Loganville. The wins and accomplishments continued to pile up, as monumental success followed him everywhere he went.

Bradley returned to coach Newton for a second time in 2001. I was sports editor of The Covington News at the time, which made it my good fortune to cover the man about whom I had heard so much while growing up here. He exceeded all my expectations in those four years. I had never been around such wisdom. Bradley guided the Rams to three 20-win seasons and two region championships, closing out his second tour at the school with a Final Four appearance in 2005. He proceeded to coaching stints at Greater Atlanta Christian

School in Norcross and Heritage High School in Conyers before calling it a career.

By the time Bradley was done, the numbers were downright staggering. He had compiled a 1,372–413 record, giving him the highest win total of any high school basketball coach in state history. Keep in mind, this says nothing of the successes he enjoyed coaching baseball (158 wins) and football (130 wins). Bradley belongs to seven different halls of fame and drew enough attention for his exploits that he was featured in Sports Illustrated twice. The gymnasium at Turner Lake Park in Covington now bears his name—an honor bestowed upon him by the Newton County Recreation Commission.

I left The Covington News in 2006 and flirted with the idea of writing a book about Bradley, but life became increasingly complicated in my late 20s and I regretfully lost touch with him over the years. In July, I learned that he had lost Jan, the love of his life and wife of 71 years, so news of his own death was not all that unexpected. They were inseparable—she had purportedly missed only five games of the thousands he coached—and anyone who had been around them for any amount of time had to know they would not be kept apart for long. Nevertheless, I felt a deep sense of sorrow with their departures.

Bradley may have crossed the bridge to eternity, but he leaves behind a far-reaching legacy through the children he raised together with Jan and the countless players he coached and mentored. His impact can still be felt on the sidelines, too. Rick Rasmussen, his top lieutenant and eventual successor at Newton, has stitched together a hall-of-fame resume of his own, having led the North Oconee High School boys’ basketball team to consecutive state championships in 2024 and 2025. That apple certainly did not fall from the Bradley coaching tree.

“I didn’t need to be a veterinarian to be with animals.”

Cecilia Fernandez

Cecilia Fernandez channeled her passions into purpose when she created Best Friends Farm, a refuge in Oxford where rescued animals and children with special needs find compassion, connection and community.

by WENDY RODRIGUEZ

Nestled along a quiet backroad in Oxford sits Best Friends Farm, a sanctuary where rescued farm animals find safety, care and unconditional love. Cecilia Fernandez’s lifelong passion was the driving force behind the refuge, which blossomed into a place of healing.

From a young age, Fernandez’s love for animals inspired her dream of becoming a veterinarian. She followed that pursuit and spent time working as a veterinary technician, but one day, what she once thought was her career path changed. Fernandez recalls holding a German Shepherd that was about to be euthanized, heartbroken and crying inconsolably. The pet’s owner looked at her and said gently, “Honey, you’re in the wrong business.” At that moment, upset and disappointed, Fernandez realized that her calling was not in clinical work but in giving a voice to animals which had none and showing them the compassion that she believed they deserved.

“I didn’t need to be a veterinarian to be with animals,” she said.

Fernandez had never experienced farm life firsthand. She spent part of her childhood in Buenos Aires, Argentina, and later in an industrial area of New Jersey, where she often felt out of place. It was not until later that she discovered what felt truly

natural to her: life on a farm. In the early 2000s, Cecilia moved to Georgia, where she met her husband and shared her dream of one day opening a sanctuary. After years of searching, the dream became a reality in 2015 when the family found a five-acre property in Oxford. It would soon become Best Friends Farm, a nonprofit dedicated to rescuing, rehabilitating and caring for animals who have endured neglect or abuse.

Fernandez’s motivations extend far beyond her love for animals. “My other passion, one that has always felt innate, is working with children, especially those with special needs,” she said. Fernandez recalls the moment she realized she could unite her two lifelong pursuits: a love for animals and a belief in their power to bring healing and joy to children with special needs.

After college, Fernandez began teaching special education and now works at a Montessori school in Decatur. It was through that school that her journey as an animal rescuer began. Each year, the students participate in a class project exploring the life cycle of a chicken, from hatching to maturity. At the end of the lesson, the chickens needed homes, and one rooster found his new address with Fernandez. He became the first resident of what would eventually grow into Best Friends Farm.

At the time, the farm was sustained solely by personal funds. However, when Bella, a gentle horse rescued through connections with other animal sanctuaries, arrived at the farm, Fernandez felt a spark of transformation. Bella’s rescue and a growing network of other animal sanctuaries inspired her to take the leap and officially establish Best Friends Farm as a nonprofit organization. That pivotal decision opened the door to community support and fundraising efforts that now sustain the care and rehabilitation of rescued animals while also creating a sanctuary where individuals with special needs can experience the healing power of human-animal connection.

Fernandez shared that one of the farm’s signature fundraisers, an inclusive summer camp, offers fun-filled learning and plenty of time spent with their beloved animals. Campers get hands-on experiences such as brushing horses, feeding chickens and walking the donkey. The camp not only raises essential funds for the farm but also creates a space where children of all abilities can learn compassion, responsibility and the joy of connecting with animals. Beyond serving as a refuge, the farm has become a valuable part of the local community. Through partnerships with Oxford College, students participate in volunteer programs that connect them with the animals and the farm’s mission of empathy and stewardship.

Perhaps the most profound part of this story involves how the farm served as a source of healing for Fernandez herself. She experienced an unimaginable loss in 2022, when her daughter, Sophie, died from a rare form of liver cancer. Sophie had been one of her mother’s biggest supporters, sharing her love for animals while fostering her own dream of becoming a veterinarian. “She was my right hand for the animals,” Fernandez said, “and for the children in the summer camp.” Overwhelmed by grief, Fernandez contemplated leaving behind the farm to which she and Sophie had devoted themselves, united by a mission to offer animals hope and unconditional love. In time, she found strength in honoring her daughter’s spirit. Today, Sophie’s memory lives on through every rescued life, every shared story and even in the farm’s logo. The nonprofit has found renewed purpose by continuing the mission Sophie helped build alongside her family. It stands as a tribute to the love that continues to guide Fernandez’s every step.

Every animal’s story at Best Friends Farm is one of resilience, and every visitor leaves reminded of the power of love, healing and second chances.

“We are driven by a single goal,” Fernandez said, “to do our part in making the world a better place for all.”

For information, visit bestfriendsfarmoxf.wixsite.com/website.

I grew up in Minnesota, the state with the largest population of immigrants from the West African nation of Liberia. One day, I went to a friend’s house to play music. He happened to be dating a Liberian woman, and she made this recipe. Wow, what unbelievable flavor. The meat just fell off

the bone. I had never tasted anything like it. Immediately hooked, I wanted to learn how to make it. What amazes me most about this recipe? Such simple ingredients combine to make so much flavor. There have been times when I have eaten this every day for a week. Enjoy.

• 1 cup vegetable oil

• 1 red onion

• 1 red bell pepper

• 1 green bell pepper

• 1 habanero pepper

• 1 yellow onion, sliced

• 1 tomato, diced

• 1 teaspoon minced garlic

• 1 tablespoon tomato paste

Heat up a large pot and add one cup of vegetable oil. In a blender, puree the red onion, red pepper, green pepper and habanero pepper. Add the mixture to the pot, along with the sliced yellow onion and diced tomato. Season the gravy with five Maggi cubes, one teaspoon of black pepper, one teaspoon of garlic salt, one teaspoon of minced garlic and one tablespoon of tomato paste. Let the gravy cook on medium heat for 20 minutes, stirring often. Turn heat on low, add cooked chicken wings, raw beef and raw shrimp and cook for 10–12 minutes, or until beef and shrimp are cooked through. It should be ready in 12 minutes. Serve meat and gravy on top of hot cooked white rice. Additional Tips: Add as much habanero as you would like. The more you add, the spicier the dish will be. You can add any choice of meat, including beef or pork hotdogs, sausages or fish. Chicken is the only meat that needs to be precooked before adding it to the gravy. Season the meat and gravy to your liking before serving. Ingredients

• 1 teaspoon black pepper

• 1 teaspoon garlic salt

• 5 Maggi seasoning cubes (found online or at African/Caribbean grocery stores)

• 8 oz. raw shrimp, cleaned and deveined

• 5 chicken wings, precooked

• 9 oz. of stew beef, raw

• white rice, cooked