Cover Story

Cover Story

A New Haven activist, Yale doctor, and Yale lawyer won Americans the right to oral contraceptives as part of a liberating––and eugenic––movement. Today, patients and doctors still confront the tension between autonomy and coercion.

Dear readers,

Over the past year, The New Journal has been produced in classrooms, coffee shops, and airplane terminals; between phone calls and snack interludes; sometimes standing, often sitting, occasionally lying on the floor. Untethered to one physical place, this magazine has found a home in idiosyncratic corners and ordinary moments. We, too, have found a home in this magazine. During our final production, hugging each other goodbye in the Silliman seminar room, we realized we would carry an indelible piece of TNJ with us.

In Volume 57, Issue IV of The New Journal, writers hunt for truth. In our cover story, Mia Rose Kohn ’27 untangles the contradictory history of the birth control pill. Exploring suspected accounts of drink spiking, Odelya Bergner-Phillips ’28 uncloaks a darker underside of campus party culture.

We wrote our first letter to you last May, amid nationwide campus protests over the war on Gaza. One year later, the Trump administration has revoked the visas of hundreds of international students, some connected to those protests. The targeting of students based on their background, protest activities, or speech, lends unique urgency to our mission as a magazine. At Tufts University on March 25, plain-clothed officers arrested Rümeysa Öztürk, a Turkish PhD student, as she was walking to Iftar dinner to break her Ramadan fast. Öztürk’s legal team argues that she was detained because of an op-ed she co-wrote in The Tufts Daily supporting pro-Palestine protests on campus.

At the end of our term, we write to you from a world very different than that in which we started. Last year, TNJ covered the U.S.’s first state-mandated ethnic studies elective courses, right here in Connecticut. Two months later, the magazine documented the beginnings of a national refugee resettlement program based on New Haven’s Integrated Refugee & Immigration Services (IRIS). But today, the U.S. Department of Education has urged school districts to eliminate any initiatives promoting diversity, equity, and inclusion or risk losing funding. IRIS recently announced that it would be shuttering its doors in New Haven, reeling from the Trump administration’s budget cuts. As the world shifts, it demands more stories.

In our board’s last issue of The New Journal, join us in looking ahead.

Signed,

Outgoing Managing Board

Maggie, Chloe, Aanika, Sam

Thank you to our donors

Mark Badger Kathrin Lassila

Jean-Pierre Jordan

Aliyya Swaby

Laura Heymann

Jeffrey Pollock

Julia Preston

Armand LeGardeur

Katie Hazelwood

Benjamin Lasman

R. Anthony Reese

Andrew Court

Fred Strebeigh

Peter Phleger

Steven Weisman

David Greenberg

Suzanne Wittebort

Romy Drucker

James Carney

Makiko Harunari

Laura Pappano

Marilynn Sager

Blake Wilson

David Gerber

Daniel Yergin

Barak Goodman

Daniel Brook

Eric Boodman

Stuart Rohrer

Sally Sloan

R. A. Reese

Leslie Dach

Editors-in-Chief

Maggie Grether

Chloe Nguyen

Executive Editor Aanika Eragam

Managing Editor Samantha Liu

Creative Director Alicia Gan

Business Manager Alex Moore

Verse Editors

Ingrid Rodríguez Vila Etai Smotrich-Barr

Senior Editors

Jabez Choi Paola Santos

Viola Clune Kylie Volavongsa

Abbey Kim

Associate Editors

Chloe Budakian

Ben Card

Jack Rodriquez-Vars

Tina Li

Sophia Liu

Hannah Mark

Ashley Choi Calista Oetama

Matías Guevara Ruales Josie Reich

Mia Rose Kohn

Copy Editors

Sara Cao

Lilly Chai

Sophie Molden

Sasha Schoettler

Diego del Aguila Vivian Wang

Sophia Groff

Podcast Editors

Suraj Singareddy

Sawan Garde

Design Editors

Ellie Park

Sophie Lamb

Ashley Zheng

Sarah Feng Vivian Wang

Jessica Sánchez

Photography

Lauren Yee

Colin Kim Gavin Guerrette

Ellie Park

Web Design

Aaliyah Short Kris Aziabor

Caleb Nieh

Members & Directors: Haley Cohen Gilliland • Peter Cooper

• Andy Court • Jonathan Dach • Susan Dominus • Kathrin

Lassila • Elizabeth Sledge • Fred Strebeigh • Aliyya Swaby

Advisors: Neela Banerjee • Richard Bradley • Susan Braudy • Lincoln Caplan • Jay Carney • Joshua Civin • Richard Conniff • Ruth Conniff • Elisha Cooper • David Greenberg • Daniel Kurtz-Phelan • Laura Pappano • Jennifer Pitts • Julia Preston • Lauren Rawbin • David Slifka • John Swansburg • Anya Kamenetz • Steven Weisman • Daniel Yergin

Friends: Nicole Allan • Margaret Bauer • Mark Badger and Laura Heymann • Anson M. Beard • Susan Braudy • Julia Calagiovanni • Elisha Cooper • Peter Cooper • Andy Court • The Elizabethan Club • Leslie Dach • David Freeman and Judith Gingold • Paul Haigney and Tracey Roberts • Bob Lamm • James Liberman • Alka Mansukhani • Benjamin Mueller • Sophia Nguyen • Valerie Nierenberg • Morris Panner

The Adrian Van Sinderen Prize has attracted book collecting fanatics, old and new, since 1957.

Adele Haeg

Yale student veterans learn how to bridge the military and the university. By Dani Klein What Flew In

Across Connecticut, researchers, farmers, and environmentalists grapple with the uncertainty of bird flu. By Sarah Cook On Leaving

After a landmark lawsuit, Yale drastically reformed its leave of absence policies for students with mental health crises. Two years out, how far has it come?

By Kelly Kong

Stories of drink tampering haunt the Yale party scene––but barriers to testing and a culture of silence have made the phenomenon largely untraceable.

By Odelya Bergner-Phillips

A New Haven activist, Yale doctor, and Yale lawyer won Americans the right to oral contraceptives as part of a liberating––and eugenic––movement. Today, patients and doctors still confront the tension between autonomy and coercion.

By Mia Rose Kohn

Sussbauer

Ren Topping

Scoot!

Ireally dislike the bookshelves that are color-coded,” says William Bramwell ’27, with a grimace. He thinks it’s tacky.

Bramwell collects books, but he doesn’t consider himself a book collector. “It’s never been conscious, like ‘I’m a collector,’” he explained.

He does, however, have a collection of twenty-six books, which he’s titled “The Wealth of Ideas: The History of Economic Thought.” That title is a play on Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations, which he has in hardcover, the 1937 edition.

Some collectors spend vast sums hiring curators to color-code their bookshelves. To them, books are like wallpaper: decorative, and purely material. But not to Bramwell—he’s in it for the “wealth of ideas.”

Bramwell started reading about economic theory during the COVID-19 pandemic. He had never taken an economics class before, but after lockdown orders went into effect and the economy collapsed, he started to pay attention to debates over economic policy that were playing out on the news.

Bramwell, then a high school freshman, first read N. Gregory Mankiw’s Principles of Microeconomics, a standard college economics textbook, cover to cover. Next, Aristotle’s Oeconomica. Then it was Locke, then Hegel, Engels, Marx, and Kahneman. Joseph Schumpeter’s History of Economic Analysis became a “constant bedside companion” of his.

Before Bramwell knew it, he “was tumbling down the rabbit hole of economic thought.”

Now Bramwell is a veritable expert on the history of economic theory, even though his education in the field was “self-directed.” When we met to talk about his collection in the nave of Sterling Library, he gave me a lesson on the theory of marginal utility—very useful, if unprompted.

This spring, Bramwell submitted his collection to be considered for Yale’s prestigious Adrian Van Sinderen Book Collecting Prize. Every year, one senior and one sophomore win the 1000 dollar and 700 dollar prizes, respectively.

Aside from the money, there’s clout associated with the prize in the rather insular world of book collecting, but Bramwell wasn’t collecting books in hopes of winning. He found out about the competition two weeks before submissions were due, years after he had started his collection. The past winners I talked to didn’t curate their collections with the objective of winning the cash either. If money and prestige aren’t driving these collectors, then what is?

The eponymous Adrian Van Sinderen, Class of 1910, endowed the prize in 1957. In his New York Times obituary, Van Sinderen is sketched as a “man of wide interests”: he was a businessman and philanthropist, and an accomplished organist. He won two thousand five hundred horse racing ribbons across the U.S. He wrote over thirty books, twenty-five of them about Christmas. He traveled to every U.S. state and national park, and every continent but Antarctica.

Van Sinderen instructed that his prize be awarded to amateur book collectors “not on the basis of the rarity or monetary value of the books, but rather for the imagination and intelligence used by the student in forming his collection.” Recent winning collections include “Nehru, Nehruvianism, Nehrumania,” and “A Compendium of the Allusions of Lemony Snicket.” Evidently, points for whimsy.

Van Sinderen was in his heyday during the Roaring Twenties. During that period, accumulating stuff was how ordinary Americans signaled their status and education level. Consumerism and materialism were booming. It became stylish to own and display books. You didn’t have to read them—just wear them like shoes or a bag, or match them to the upholstery in your sitting room.

Van Sinderen himself was wealthy, make no mistake. He had the money to romp across six continents in his lifetime, which was not easy to do before the airplane.

Perhaps this curious clause in his endowment of the prize about rewarding “imagination and intelligence” over monetary value is a clue to why he established the prize, and why he wanted it to be his legacy here. He funded this prize, instead of paying for a Van Sinderen Tower or a Van Sinderen Hall.

Van Sinderen may have observed that something was disappearing from how America consumed books—that very “imagination and intelligence,” perhaps. And he must have wanted to preserve it, celebrate it, and teach it.

Book collecting might not seem like a practical pastime for college students, who often lack disposable income and bookshelf real estate. Professional book collectors spend inordinate amounts of time and money competing at auction for first editions and signed copies of texts, after them for their “rarity and monetary value.”

Even so, for almost seventy years, the Van Sinderen Prize has attracted bookish undergraduates interested in collecting. They do it for the sake of the intellectual pursuit and find themselves falling down rabbit holes like Bramwell did. It’s rather curious.

For judge Seth Bellamy ’25, “book collecting is not this seamless act of finding an author and buying all their books.” Enrique Vazquez ’23, who won the prize his senior year, agrees that “part of the fun is the hunt”; he’s found some of his favorite books at sales in church basements or antique stores in rural Minnesota. Professional book collectors have bibliographies, like shopping lists for auctions they attend.

Judges evaluate a collection not on the number of books on the list or their value, but on how cohesive the collec tion is. If the aim of a collection is to answer a question put forth by the col lector, then judges evaluate how well the question is answered. As Bellamy explained, collecting is “cultivat[ing] a way of knowing.”

The question that ties Bramwell’s collection together is: How does our economic system function, and why does it function that way?

Harvard, Princeton, and other uni versities have their own versions of the Van Sinderen Prize, and there’s an

annual national book collecting prize awarded by the Antiquarian Booksellers’ Association of America. Enrique Vazquez ’23 won third place in the national competition in 2023.

The question Vazquez asked in his collection “Tales of the Midwestern Northwoods” was: How do I bring a little bit of home with me to Yale?

After moving to New Haven from Minnesota, Vazquez felt like he was “in two separate worlds.” He started collecting books “out of a desire to stay connected to the Midwest.”

The first book Vazquez bought for his collection was environmentalist Sigurd Olson’s Listening Point, set in what is now known as the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness in northern Minnesota, where Vazquez also loves to adventure. “It is tradition to sit at Olson’s point and reflect on one’s

Vazquez started to hunt for more books by outdoorsmen, indigenous peoples, trailblazing women, artists, loggers, and families like his who had captured the beauty of that “listening point.” He wanted to be able to transport himself there when he was in New Haven, far from the northwoods and his family.

Van Sinderen, who traveled to six continents, all fifty states, and every national park in the United States, wrote that “the search for books leads one into strange, interesting, and always delightful worlds.” Van Sinderen found those worlds—real and imagined— while searching for books and in his books themselves. For him, it would be ridiculous to evaluate a collection on the material value of the books assembled: the value of books as worlds themselves transcends the paper, ink, and glue they’re made of.

Otherwise he’d borrow.

Graham Arader ’72, who is 72 years old, won the prize twice and is now one of the foremost rare book and map dealers in the United States. He still has every book from the collections he submitted for the prize when he was a student, not to mention thirty thousand other books in his reference library on American history and cartography.

Arader has made a living on books and maps, yet he admits “95 percent of the reason for the existence of libraries was ended twenty years ago by Google.”

For Arader, the aim of the library— and the aim of book collecting—is the preservation of “material culture,” and for the university, “exciting students by showing them the original work of art in the classroom.”

Vazquez is always thrilled to find marginalia in books he digs up at antique stores. Previous owners of books in Vasquez’s collection left notes in their books about planning future trips, packing lists, or reflections on trails they had trekked. That’s that “material culture.” It

For Vazquez, “books are lived.” Rebecca Romney, a professional book collector who delivered the annual Van Sinderen Prize Lecture this February, said in her presentation: “Book collecting is storytelling, and it’s not just the story of our books but the stories of

Adele Haeg is a first-year in Timothy Dwight College.

By Dani Klein

James, or Jimmy, Hatch ’24 laughed when a Yale professor suggested he apply to Yale as an undergraduate student. Despite his nearly twenty-six years in the U.S. Navy and multiple deployments as a SEAL, he couldn’t believe that Yale would be interested in what he had to say. Hatch had dropped out of high school with a GPA in the “high ones” to join the military. After visiting Yale to give a talk and tour the campus, he wrote and submitted his application, including its two essays, in under an hour. He had low expectations. Yet, in 2019, Hatch matriculated at Yale as a 52-year-old first-year.

Arriving on campus, he was unsure how the community would welcome him.

“I thought I was a monster because I’d been doing what I was doing, I was really good at it, I enjoyed it, and I felt like it was what I should be doing. I was paid to be a criminal,” Hatch said. “I was concerned that people here wouldn’t see the value of that, and in fact, that they would be freaked out by me, but that wasn’t the case.”

Hatch spent four years as a Navy sailor and twenty-two years in the SEAL Teams, during which he served as a parachute instructor and had combat deployments to Bosnia, Afghanistan, and Iraq. He received four Bronze Stars throughout his service, awarded for heroism in combat. In 2009, on a mission to rescue a captured soldier, Hatch was shot in the leg, resulting in injuries that required eighteen surgeries and ended his military career. Hatch was awarded a Purple Heart. Post-traumatic stress disorder,

substance abuse, and a suicide attempt marked his rehabilitation process.

Ten years after his injury, Hatch became the first non-traditional student in Yale’s Directed Studies program for first-years, and he went on to major in humanities. After receiving his bachelor’s degree in 2024, he served as a resource to incoming Directed Studies students, calling himself the “old man with arm tattoos who hands out fliers before the lectures from time to time.” This spring, Hatch became a lecturer for the Jackson School of Global Affairs, teaching a course called “The Impact of War on Its (Willing and Unwilling) Participants.”

To better understand the veteran community at Yale, I talked to fifteen U.S. military service members from five branches of the armed forces—one active duty Marine, a professor who served in the army, and thirteen student veterans in the Eli Whitney Students Program. Founded in 2008, the Eli Whitney program offers adults without bachelor’s degrees who are more than five years out of high school the opportunity to enroll in Yale undergraduate classes full or part-time. The program has doubled in size over the past five years, with twenty-six Eli Whitney students matriculating in 2024, seventeen of them veterans. Yale College is now home to approximately fifty enrolled student veterans. At a moment when elite universities have come under fire from the right for being anti-American, the student veterans who come to Yale grapple with bridging two worlds: the military, and the university.

When veterans enter the higher education market without experience or guidance, they can underestimate their academic potential, which can lead to a phenomenon known as “undermatching.”

Risa Sodi, an Associate Dean of Academic Affairs and Yale’s Director of Advising and Special Programs, said that the admissions office’s greatest challenge with student veterans is urging them to apply to competitive universities. “Sometimes people select themselves out— they just think, ‘I’ll never get into Yale, so I won’t bother applying,’ ” Sodi said.

Yale professor Michael Fotos, who is a founding faculty volunteer with the Warrior-Scholar Project and chairs their Board of Directors, said that veterans’ humility and “gravitas” make them some of the strongest students.

Nearly all of Yale’s Eli Whitney student veterans benefited from specialized programs like Service to School and the Warrior-Scholar Project, which help prepare veterans for college with workshops and counseling. Yale was the first undergraduate college to partner with Service to School.

Brandon Choo ’26, a junior and active duty Marine who most recently served as a scout sniper instructor, enrolled at Yale through the selective Marine Corps Enlisted Commissioning and Education Program. MECEP allows enlisted Marines to become officers while attending a naval ROTC-affiliated college. “I never really thought of an Ivy

League school as a legitimate option for me. It was always kind of like a lofty, faraway place, where the smart people go,” Choo said. “I’m very grateful to all the people who helped me get here.”

Starting in the 2022-2023 academic year, Yale began meeting 100 percent of Eli Whitney students’ demonstrated financial need. Yale also participates in the Yellow Ribbon Program, meaning the university works with the Department of Veterans Affairs to cover some or all college costs not covered by the post-9/11 G.I. Bill, a federal program that subsidizes certain tuition costs for veterans and their families.

Among student veterans, the question of whether they felt prepared for their Yale education is complicated. For some veterans, parts of their military experience mirrored Yale’s academic rigor. A significant portion of Eli Whitney student veterans worked in intelligence, including several students who served as linguists.

According to Robin Dudley ’27, a former Air Force airborne cryptologic language analyst in Mandarin Chinese, her training at the Defense Language Institute was so rigorous that she feels she can now conquer any academic challenge. For Dudley, the Yale undergraduate experience is “a piece of cake in comparison.”

Choo, on the other hand, said that the military and Yale are both demanding but in different ways. “I thought I knew how to manage time very well before I came to Yale, and then I came here, where you have to plan your day down to the nearest thirty minutes every single day for four academic years,” Choo said. “That’s its own type of discipline, but I don’t know if I’d be successful at it had I not had my military experience.”

Niels Newlin ’27 said that Yale’s demands for creative and critical analysis were an adjustment. He served for six years as an Army combat medic, deploying to South Korea during his service, and he grew accustomed to strictly regimented work. In the military, “you’re signing yourself up to not think and just do,” he said.

Patrick McGrath ’26, a Coast Guard veteran, incoming president of the Yale Undergraduate Veterans Society, and current economics major, primarily worked in counter-narcotics operations, participating in high-risk drug busts and seizures in international waters. In high school,

McGrath struggled academically and graduated with few options. He called the academic intensity of Yale far outside his comfort zone and “hands down the hardest thing I’ve ever done in my entire life, by an enormous margin,” but he also enjoys the freedom to budget his own time.

Hatch said he “never got stressed out about exams or grades, or let that control my life. I did study hard, but I didn’t get ridiculous. Nobody was shooting at me, you know what I mean?”

There are similarities between being in a special missions unit and being at Yale, Hatch said: both have rigorous vetting processes and high expectations for their members.

“Yale is in the business of building humans, at least in the undergraduate world. I watched it happen when I was a student: it would take a couple of classes for these kids to understand exactly what the professor needed, and then they’d just start cranking it out,” Hatch said. “Watching that drive, even in a form that seemed decidedly different than the drive I’d needed in my previous life, I could recognize that it was the same drive.”

For Hatch, going from close quarters combat to reading canonical writers like Hobbes, Locke, and Rousseau theorize about the original state of mankind was emotionally jarring. He cried in a professor’s office because of how the reading made him reflect on his military experience.

“I showed up here with some fucking baggage, so to me, I was like, how can any of these people really know what the fuck is going on if they haven’t been in that environment? In war?” Hatch said.

Hatch never wants to embarrass professors because he knows they all genuinely want the best for their students. He has spoken privately with professors after class when they have made incorrect statements about the nature of modern warfare.

“I had a professor say, ‘This kind of combat that happens in The Iliad doesn’t happen anymore—people don’t even see each other, it’s all done by drones.’ And I had to say, ‘That’s not true,’” Hatch said. “The night I got shot, I was ten feet from

the guy who shot me. I looked in his eyes. We see each other all the time, you just don’t hear about it.”

Perhaps the most important thing that service members contribute to campus is their perspective on the enormity of the suffering that occurs as a result of war. John Tesmer ’27, who served as a Russian Linguist in the Air Force, says he has never met a group of people more anti-war than some of the veterans with whom he’s spent time.

“That’s probably the realization of having seen it—you just realize how horrific it is,” Tesmer said. “My personal belief is that war should be avoided at all costs. I don’t think I would have believed that at 18 or 19, before going through experiences that gave me an appreciation for death and destruction at scale.”

Unlike most Eli Whitney students, most Yale undergraduates weren’t even born when the U.S. invaded Iraq in 2003, and most started elementary school nearly a decade after the beginning of the War on Terror.

“I do believe there’s a bubble here, of ‘everything’s gonna be okay,’” Hatch

said. “I also believe that pacifism is great until people want to take your shit and kill your family. I think that’s one of the most difficult things for me to translate here at Yale—it’s hard for me to convey the reality of the threats out there to our country.”

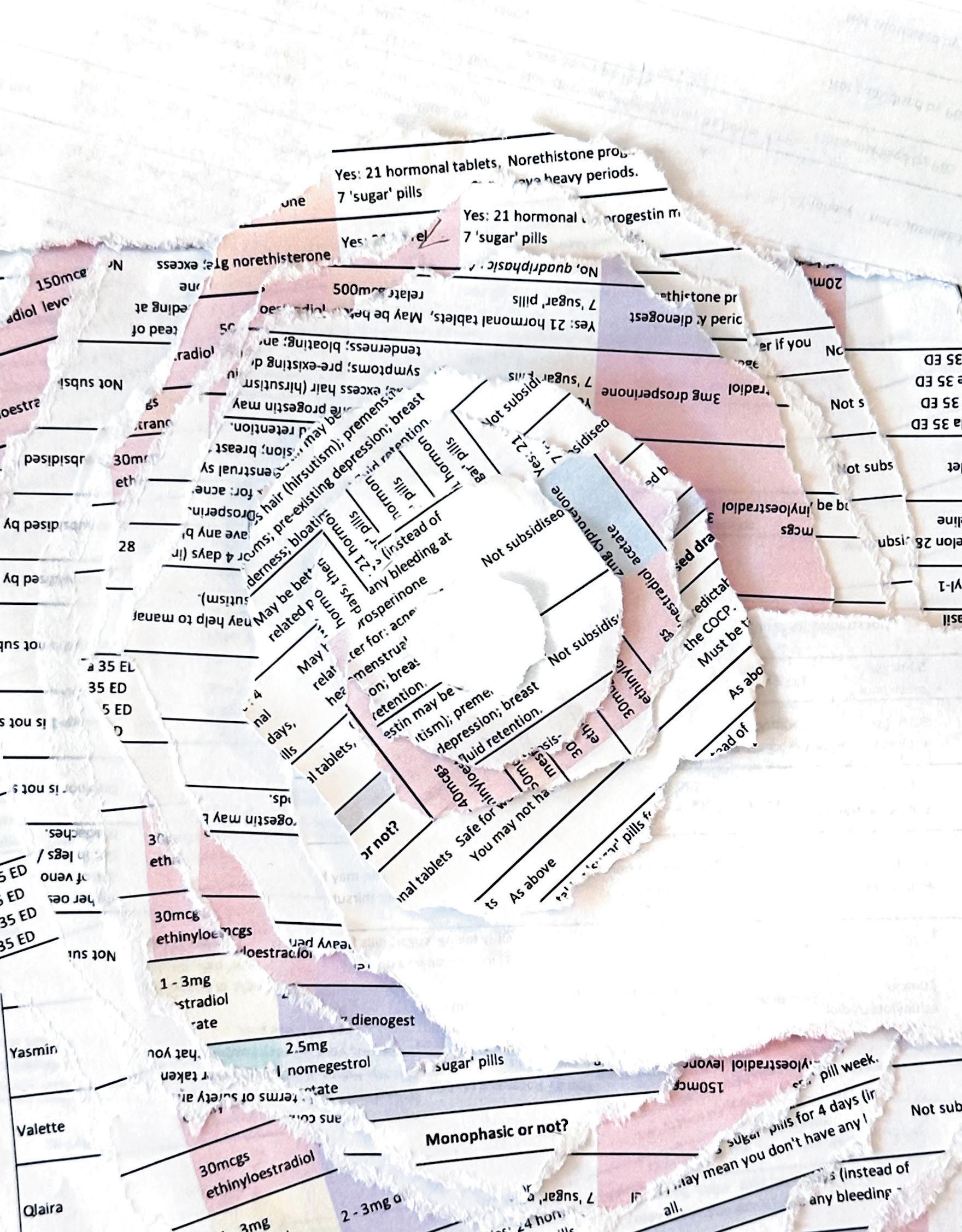

Yale and the military have been closely intertwined for hundreds of years, evidenced by the names etched in the Schwarzman Center Rotunda and the veteran memorial in Hewitt Quadrangle. In past decades, however, Yale’s relationship with the military has been rockier. In the early 1970s, Reserve Officer Training Corps (ROTC) programs withdrew from Yale following failed negotiations to keep the programs on campus in the wake of student protests during the Vietnam War, declining enrollment in ROTC programs, and the University’s decision to stop granting academic credit for ROTCmandated courses.

Yale and peer institutions received backlash to their ban on the ROTC program. Even after the ROTC ban was reversed in 2011, journalist Nathan Harden ’09 criticized Yale for its “steady loss of patriotic ethos over the last forty years,” citing the ROTC ban and the “rabid Vietnam-era anti-military sentiment of the radical Left” as factors that caused Yale’s un-American turn.

In the week after his election to the presidency in 2024, Donald Trump released a video statement in which he vowed to fire “radical Left” accreditors that have allowed colleges to be dominated by “Marxists, maniacs and lunatics,” calling academics at Ivy League schools “obsessed with indoctrinating America’s youth.”

The idea of a student veteran studying at Yale contradicts this image. Associate Director of Yale’s BradyJohnson Program in Grand Strategy Michael Brenes consistently teaches veteran students in the program, which examines large-scale, long-term strategy in issues of political and social change as well as statecraft. Brenes considers the caricature of the Ivy League university as radically anti-America and anti-military reductive.

Coming into Yale after serving for twenty years, former U.S. Army Ranger and Intelligence Analyst Tristan Benz ’27, a Global Affairs major, has encountered

this perceived divide between Yale and the military among his friends. “Some of them look at Yale in a certain political kind of light, and they might assume that I wouldn’t fit in, instead of looking at everything that Yale actually is,” Benz said. “They’re looking at it from a certain perspective that they gather from some media.”

David Allison, an Army veteran, Yale lecturer, and fellow with the Nuclear Security Program, said the people who believe Yale is a bastion of radicalism and criticism of American values have likely never experienced Yale campus life.

“When I think about my soldiers, the soldiers who served under me, I don’t imagine them coming to one of my courses and saying, ‘You’re so different than you were in the military,’” Allison said. “And I’m not getting complaints from undergrads saying, ‘You’re a vicious warmonger.’ There is a lot more overlap than we might anticipate.”

For the vast majority of the 20th century, the U.S. government was almost entirely made up of people who both had military experience and had been through

higher education. According to the Pew Research Center, between 1965 and 1975, at least 70 percent of Congresspeople had experience in the military–largely due to conscription during World War II and the Korean War. Comparatively, that percentage has hovered around 20 percent in the past decade.

“There’s a disconnect between who’s actually fighting the wars and who’s planning the wars,” said Tesmer. “And the people that are planning the wars by and large come from top 25 schools.”

It can be frustrating to observe the separation between the reality of combat zones and the bureaucracy that makes consequential military decisions, especially in the Pentagon, said Paul Lomax ’27, who served in Naval Special Operations and was deployed twice to Afghanistan.

“These are people that aren’t on the front lines, and they’re making the big-time, big-picture decisions in D.C They’re focused on the logistical aspects, and they’re also politicians,” Lomax said. He criticized the U.S.’s withdrawal from Afghanistan as evidence of this disjuncture. “They were just so disconnected

with what was going on on the ground halfway across the world, and a lot of incorrect decisions were made.”

According to Brenes, Yale has a responsibility to give students a human picture of conflict, even if they will never see it up close.

“You will never fully be able to understand what it’s like to be a service member if you’ve never been in that role, but that doesn’t mean that you’re prohibited from studying it or trying to understand it,” Brenes said.

Sometimes that separation is good, Lomax said, and it can allow leaders to make nuanced decisions on consequential issues. However, for other student veterans, it’s essential for traditional students to graduate from Yale with some level of personal connection to the human cost of war.

Thomas Ghio ’26, the outgoing president of the Yale Undergraduate Veterans Society, served in the Air Force as a Tactical Air Control Party, meaning he coordinated airstrikes from the ground.

“A lot of people that come to Yale or schools like Yale become leaders in all kinds of different areas of life, and by having student veterans on campus, it allows them to be exposed to that perspective and and take that with them as they continue their journey and hopefully make a better world for all of us,” Ghio said.

Yale might be the first place that Yalies get to have a real conversation with a veteran, Brenes pointed out.

The landscape of U.S. foreign policy has changed drastically since Hatch first joined the military, to when the U.S. began the War on Terror, to now. Since the end of the Iraq War and the U.S.’s withdrawal from Afghanistan, it’s no longer accurate to assume that any given veteran has deployed overseas or experienced combat. New service members may join the military for education or career opportunities, just as others join due to a sense of duty or patriotism.

Many of the veterans I spoke to mentioned that they had braced themselves for stereotypes about the military at Yale, but they were pleasantly surprised by how students and professors treated them on campus. In fact, multiple students told me their veteran status afforded them higher respect from professors.

Hatch said that the visibility of his military service—in the form of a cane, tattoos covering both arms, and occasionally his service dog—can lend more gravity to his presence on campus.

“There’s a currency to combat and violence,” Hatch said. “If I hadn’t been involved in the special operations world, if I hadn’t served the way that I did, and done the amount of combat deployments that I did, what would make me stand out?”

Hatch’s new class involves reading, discussing, and writing about various literary texts and primary sources that shine light on the experiences of those impacted by war, from civilians to military leaders to soldiers. When the class first began, it struck Hatch that his students

had never met anyone like him—someone who had seen war up close.

The class has hosted several speakers, including a professor from Ukraine and a professor who fled Afghanistan with her child after operating an all-girls school in her neighborhood. Veteran and U.S. Senator Mark Kelly and General Scott Miller are slated to visit the class soon. Facilitating this diversity of perspective is, to Hatch, an act of patriotism.

“If I’m helping you guys, even if you fucking hate the military and disagree with me, if I’m helping you guys, I’m helping our country,” Hatch said. “I truly believe that.”

Hatch has been finding the new class to be a challenging and humbling experience, and the seminar has become

a very tight-knit community. He’s cried reading some of the papers in his class, and he’s been deeply moved by the openness and audacity of some of his students to confront unspoken tensions.

When he looks around at the faces of his students, he worries that they are taking on the weight of the world. While facilitating seminars, he remains vigilant in choosing his words carefully, because, as he said, his job now is “giving these kids ammunition for the fight that they have ahead of them, when they are introduced to this thing called war.” ∎

In the fog before church the cafes are closed, the good grocers also save one in which I know no Spanish and am sorry.

How strange it is to apologize here. Andalusia. Her mute sun is lost on me. Her seasons and signals of seasons have lapsed these six or seven centuries.

I cannot trust Sevilla’s orange trees in their columns on the Feria road. I cannot trust the orange of their oranges.

Lady living here: The locals know they are not to be tasted, or are to be tasted if you fuss to peel and jelly them.

Knowing no better I thank her. I still cannot accept. Not from a jar. I will have the outsides of those oranges bitter as they are. Not the candied rest.

––Netanel Schwartz

Stories of drink tampering haunt the Yale party scene—but barriers to testing and a culture of silence have made the phenomenon largely untraceable.

By Odelya Bergner-Phillips

John ’27 was at a fraternity formal at Noa, a Thai restaurant on Crown Street, in spring 2024.

John is “not the type to get blasted,” he told me, especially when he is out with a date, as he was that night. “I wouldn’t have embarrassed myself like that.”

But he hardly remembers anything from the event.

In fact, by his recollection, the night was a short one. He remembers sharing a drink with one of his friends. He remembers being at the formal for just a few minutes. John was shocked to hear, afterwards, from his friends that he had stayed for the entire event––roughly an hour and a half of his memory gone. He remembers telling his date he had to throw up. He remembers getting into an Uber and making it back to his residential college. “It was there that my body gave out. I couldn’t really move,” John said. His friends had to physically drag him inside until a First-Year Counselor (FroCo) spotted them. Concerned, the Froco called the ambulance. John and the friend with whom he shared the drink ended the night at the Yale New Haven Hospital.

He is not sure what time he checked into the hospital, but believes he left at around 4 a.m., after waking up with a pounding headache on a stretcher in the hospital hallway. “I guess hospitals are pretty busy, and if you have a drunk, you are not going to waste an entire room on them,” he recalled. He wasn’t tested—he doesn’t know exactly why—but his friend was. His friend tested positive for Rohypnol.

Rohypnol, colloquially known as “roofies,” can be odorless and tasteless, and is one of the most commonly used drugs in drink spiking and date rapes, as it can slip undetected into a drink. Like John experienced, Rohypnol, a central nervous system depressant, causes memory loss, vomiting, headaches, and loss of mobility.

To this day, though he did not test himself, John feels certain that the fateful drink he and his friend shared was spiked.

John’s friends told him that for most of the night, before he lost his ability to speak, walk, or even stand, he seemed fine—just drunk—to those around him. Despite his seemingly normal presentation, he believes he was feeling the effects of having been drugged. “There’s a period of time when you seem fine, but you are actually already roofied, and you can’t remember anything before you collapse.”

The next day, after returning home from the hospital, John felt fine, aside from a lingering headache. But this episode had unfolded during finals

period, and he quickly had to regroup and attempt to focus on his studies. As John tried to prepare for his exams, he found himself returning to the confusion that night––a suspected drink spiking with no clear culprit or motive. Categorized as a “date-rape drug,” Rohypnol is commonly used to drug people to facilitate sexual assault. But John was not assaulted, adding to the disturbingly random and senseless feeling—what exactly had happened to him, and why?

I sought to understand the prevalence of experiences like John’s on Yale’s campus: nights out that seemed normal but ended with a blackout, sickness, and memory loss. Dozens of people I spoke to, either in interviews or informally, had a story, believing that they, a friend of theirs, or a friend of a friend had experienced drink spiking. I realized, however, that assessing the prevalence of drink spiking at Yale was not possible and, at this time, largely indeterminable. There is no data available on the number of Yale students roofied, let alone on the number of drink spikings happening in the City of New Haven. At every stage of the phenomenon, physically, medically, and legally, drink spiking enacts a disappearing act—it often goes unknown, undetected, random, and untraceable.

These barriers make drink spiking so difficult to measure and protect against. The tracking procedures that do exist are underutilized, as victims are clouded by either the drugs themselves, which often cause memory loss and impair victims’ ability to advocate for themselves, or by shame and fear that they might be penalized for drinking underage.

Few people wanted to speak publicly about their experience with suspected roofieing. Some felt ashamed about being a victim, and others worried about damage to their professional future should they be named in this piece, particularly in connection with underage drinking. Those who did speak did so only under the condition of anonymity, and are identified as John, Jane, and Jessica.

The last time the Yale Daily News reported about instances of drink spiking on Yale’s campus was in the 2018-2019 academic year. That October, the Yale Daily News covered a drink tampering incident at a suite party in Durfee Hall on Old Campus, after which two female students were hospitalized and one tested positive for Rohypnol. The incident was investigated by the Yale Police Department, but in an article months later, the Yale Daily News reported that no suspect had been identified.

College students are a higher risk group for drink-spiking, a 2017 study found. This past November at Cornell University, the Cornell Police received a report about a female student being coerced by several male students into taking ketamine and possibly other drugs before being sexually assaulted at a fraternity, leading to the fraternity’s temporarily suspension, and the Cornell

Interfraternity Council’s decision to suspended all social activities the following weekend. According to The Guardian, the incident is under investigation, but no further reporting has emerged. Given the public nature of the incident, its communal response and reactions were similarly public, including in an editorial published by The Cornell Daily Sun, spurring dialogue in the Cornell community. At the start of this academic year, the Boston Police Department issued a community alerts warning for college students in the region against the dangers of “scentless, colorless, and tasteless drugs” such as Rohypnol. In California, the state assembly recently passed a law requiring state universities and community colleges to have free and accessible drug testing devices in health centers.

In New Haven, the number of publicly reported cases is sparse––so is the public conversation around drink spiking. The New Haven Police Department hasn’t issued warnings and the state of Connecticut hasn’t passed bills. Yet the lack of news coverage does not align with the magnitude of the topic in casual, campus conversation. Roofieing, particularly in the context of fraternity parties, is normalized in postings on Fizz, an anonymous social app. In December 2024, three posts by Yale students referenced a fraternity’s reputation for roofieing each garnered over two thousand upvotes. One post, from early March, asked: “does anyone know if i can get tested for roofie drugs in my system?”

The five students I interviewed could all name at least one person who thinks they have been roofied. Ava Boston ‘26, Chief of Service of Yale Emergency Medical Services, an undergraduate organization that provides standby coverage to Yale’s campus, noted, “I’ve had friends that this has happened to at Yale, or at least they believe it happened to them… It does happen here, and it’s extremely sad.”

Without large-scale institutional data, students have come up with their own precautions and conceptions of the issue. Recent graduate Amanda Ivatorov ’24 spent her senior year studying drink spiking in the Yale community. She wrote to me that in her freshman year, multiple of her peers were roofied at a fraternity-sponsored, off-campus event. With guidance from two doctors at the Yale School of Medicine, Ivatorov designed a study of the student response to NightCaps, a commercially sold product placed on top of cups to protect against spiking.

Yale students in Ivatrov’s study completed a brief survey before they received a NightCap in February 2023, and were surveyed again in April and May 2023. The majority of respondents expressed worry about roofieing—of the 171 respondents, 60 percent agreed that “At social events on and near Yale’s campus, I am worried about drink spiking.” These results suggest a fear among many students, amplified by the perception that everyone around them has some connection to the issue.

But a true assessment of the prevalence is nearly impossible, as most cases of suspected drink spiking remain unconfirmed and are often either not investigated or unsolved.

“Perhaps Jane’s experience would have been different if someone had recognized her abnormal behavior that night. But drink spiking is essentially impossible to distinguish from normal intoxication, even with common sense and extensive training.”

In Yale’s 2024 Title IX Report on the Higher Education Sexual Misconduct and Awareness, Yale women who experienced sexual assault with penetration involving physical force or inability to consent were asked whether they had been given drugs or alcohol without their knowledge or consent. Some— 8.5 percent—said they suspected it, and another 10.3 percent said they did not know. None of the participants said they were certain.

Why do so many students, who suspect their drinks have been spiked, not get tested?

Some never make it to the hospital or receive medical care at all.

Jane ’28 believes her drink was spiked during a night out at a Yale fraternity earlier this semester. She was out with a group of friends and remembers receiving her last drink of the night—a vodka Sprite. She does not remember what happened next. “You could tell me I cartwheeled out of there and I’d believe you because I just have no clue.”

Like John, much of her knowledge of that night is pieced together from small moments she remembers and what her friends reported to her in the following days. She told me that her friends took her back to her suite, but Jane remembers little from the night. “Apparently the whole way home I couldn’t walk on my own,” she said. “I had to be handed off to someone because I was so unstable with my walking, I was zig-zagging and pulling in different directions.” While she doesn’t remember this walk back to her dorm, she remembers lying on her friend’s floor asking, “Is this real?”

Then, she became “horribly violently ill.” She told me she was throwing up until the late afternoon the next day, and still shaking two mornings later. “I couldn’t eat, I couldn’t drink, I just kept throwing up everything,” she said. “I thought I was dying.”

Jane told me she did not seek medical services or get tested because she felt too sick to get herself to the Yale Health Center. “I didn’t want to have to put on clothes and leave my suite because I was so ill.” After vomiting for hours, throughout the night, and the following day, she still did not understand the extent of her memory loss and strange behavior from the night before—she did not yet suspect that she had been roofied.

Only after talking with friends and doing online research, hours after her incessant illness finally receded, did she begin to suspect she had been roofied. Her reaction to the drink that night had been abnormal. “I know my limits and this was within my limit,” she told me. She had never once been sick or thrown up after a night out. Jane spoke to a friend who also suspected she had been roofied on a different night but—like Jane—had not been tested. Both had had the same symptoms, and both came to assume that their drinks had been spiked. After online research, over a day later, Jane concluded it would have been “too late” or too expensive to get tested, especially after looking into hair follicle testing. Such testing can pick up drugs in the system

longer than a blood or urine sample might, but costs upwards of 150 dollars. According to U.S. Drug Test Centers, one of the largest drug testing facilities in the country, Rohypnol typically passes through the system and is no longer detectable within twenty-four hours. Days later, Jane learned of another friend who had the same reaction after drinking at the same fraternity that same night out.

Perhaps Jane’s experience would have been different if someone had recognized her abnormal behavior that night. But drink spiking is essentially impossible to distinguish from normal intoxication, even with common sense and extensive training. During their training, FroCos are given scenarios about alcohol and drug-related situations. While FroCos are not trained to provide medical care, FroCo Trinity Lee ’25 explained that their training emphasizes looking out for students who seem to be “acting a bit off” or “out of character.”

An Associate Dean of Student Affairs, Tom Adams is Director of Yale’s Alcohol and Other Drugs Harm Reduction Initiative (AODHRI), which is focused on addressing alcohol and drug use on campus through education and programming. Adams wrote that AODHRI primarily works “through educational programming, including the Work Hard, Play Smart course for incoming first-years, the ‘Talking About Alcohol’ guide for Yale College families, and trainings for student leaders including FroCos, CCEs, and Camp Yale Program Leaders.”

Symptoms of a drink spiking may not always manifest in obvious ways. Yale Emergency Medical Services acts as a standby service at Yale events, including First-Year Formal and Senior Masquerade, during which students may be drinking or show up intoxicated. Boston shared that “a misconception about drink spiking is that sometimes people think it tends to be this big, dramatic thing,” whereas “sometimes it just looks like someone has drunk a lot more than they actually have.”

Adams wrote that “in any case where a person has an unexpected reaction to drinking, they should seek medical attention. If they suspect that their drink was spiked, testing is available from a medical professional.”

But testing is often not easily accessible. Hospitals have no standardized way to discern if a drunk patient has also been drugged, nor a protocol to drug-test intoxicated patients. The symptoms for alcohol intoxication and date-rape sedative drugs are the same, according to Dr. Jessica Stetz, an emergency medicine physician at Downstate Health Sciences University Hospital in Brooklyn, New York. “Honestly, you can’t tell the difference,” she said.

Stetz explained that “clinically, it doesn’t really change anything” to know whether a patient has been drugged or is simply intoxicated. There are no reversal agents, she explained, and no particular treatment. “If somebody has normal vital signs, no signs of trauma, and is comfortable, sometimes we just let them sleep it off.” She added that doctors do not test for roofieing since it does not change

their medical management, unless a patient has requested a test and is hoping to collect evidence for a legal case or has told a story that raises particular concern.

Dr. Matthew Griswold, an emergency medicine physician and toxicologist at Hartford Hospital in Connecticut, also said that it can be difficult to distinguish between an intoxicated or drugged patient. Griswold emphasized that without a specific request or a suspicious story reported by the patient or those accompanying them to the hospital, doctors are unlikely to test for roofie drugs. In confusing, late nights out, students arriving at a hospital extremely inebriated, or under the influence of drugs, may not know to request a test, or be lucid enough to do so.

There are tests, Griswold said, that are administered in some cases. A urinalysis conducted in the hospital can indicate “broad classes of drugs,” he explained, but such testing is “very broad strokes,” frequently showing false negatives. If someone is on anti-anxiety medication, for example, that may show up as a positive and not indicate to the physician what specifically the patient has consumed. More specific drug testing is not a part of standard protocol to test intoxicated patients because such tests have to be sent to a large national drug laboratory, and, according to Griswold, could cost several thousand dollars.

Stetz also mentioned a specific test kit used with victims of drug-facilitated sexual assault. The kit requires urine as early as possible from the time of suspected drug ingestion to maximize the amount of drugs detectable in one’s system and thus the test’s effectiveness. It is rarely deemed necessary or used. In the past twenty-five years, Stetz believes she has probably only done one such test.

John ’27 is not sure why he was not tested when he ended up at Yale -New Haven Hospital. While he did not explicitly request testing, he recalled being told that the hospital didn’t have any more tests. He wonders if telling doctors he had taken an edible that night might have influenced their decision not to test. “Maybe they had my best interests in mind and it would have shown up, or maybe they didn’t believe me, or something like that,” he said.

“She did not feel anything at first. ‘And then very soon, I think within like ten to fifteen minutes, both of us completely blacked out.’ ”

Another suspected victim of drink spiking, Jessica ’28, was not tested at Yale-New Haven Hospital, despite her friends’ request on her behalf.

She and her friends had attended a party at a Yale sports house in December 2024. She and a male friend shared a drink, which they got from the student bartender at the party. She did not feel anything at first. “And then very soon, I think within like ten to fifteen minutes, both of us completely blacked out.” The next thing she remembers was waking up early in the morning in a hospital bed.

“The act of drink spiking itself functions as an erasure—erasing John’s, Jane’s, and Jessica’s memories of their experience and stripping them of autonomy.”

Neither she nor her friend remembered the rest of their night, after they got that drink. The rest of the night was recounted to them by their friends. Their friends told Jessica that she seemed “very immobile,” “groggy,” and “not able to move.” She and her male friend, with whom she’d shared the drink, were both told by their friends that they had been throwing up. One of her friends called a FroCo, who subsequently called an ambulance. At the hospital, Jessica’s friend “repeatedly kept trying to tell [the doctors] that they think I had been drugged and they were really not caring about that.” Jessica told me that in the morning, the doctors told her she was “over-intoxicated,” attributing her physical symptoms to her alcohol consumption that night. She was shown the results of a blood test—the only test done—that indicated she had alcohol in her system. A blood test would show the presence of particular drugs if such a specific panel had been requested—as far as Jessica is aware, such panels were not requested, although she is not sure.

After being discharged from Yale New Haven Hospital, Jessica and her male friend returned later that day to request drug testing: “We weren’t going to do much with the information. We were just curious because it was a very weird experience and we wanted to know for our own sake.” She said that hospital staff told them that they didn’t provide such testing. The two of them went to CVS and purchased a home drug test kit for 37.99 dollars, a urine test that purports to identify fourteen drugs, including amphetamines, cocaine, ecstacy, and benzodiazepines.

Both her and her friend’s at-home tests showed a positive for buprenorphine, an opioid. According to American Addiction Centers, mixing such a drug with alcohol is extremely dangerous, causing vomiting and impaired thinking, among other symptoms.

At-home drug tests available for purchase frequently have false negatives, Griswsold explained,

and can also show misleading positives, including as a result of prescribed medications that an individual may already be taking. He also highlighted the high cost of detailed drug testing sent to laboratories, a cost that Jane mentioned being wary of when researching the possibility of getting tested a few days after her suspected drugging. “We’re trying to be really mindful about not spending our patients’ money when unnecessary,” Griswold said, adding that doctors “are not always sure when we send that testing to somebody’s insurance that they will pick it up, in which case [the patients] are on the hook for a huge amount of money.”

Both Stetz and Griswold explained that testing that might pick up Rohypnol, for example, would only be useful for the court of law, detectives, or forensic work, and not for the physicians. Stetz said that if doctors utilize the test kit for drug-facilitated sexual assault, results are not even sent to doctors. They are, instead, stored by law enforcement, according to the state’s rules of evidence.

In a statement, Tim Brown, Director of Communications for Yale Health, wrote that evaluations of intoxicated students at the Acute Care Department at Yale Health include a protocol for alcohol breathalyzer testing to assess the level of intoxication, with further evaluation based on the clinical team’s assessment. Like in the hospital, drug testing is not a part of the standard protocol. Acute Care closes at 10 p.m., meaning late-night emergencies often end up at the hospital, rather than Yale Student Health Services.

Urine drug testing, including testing for Rohypnol, is available, if a student requests it, through Quest labs within Yale Health during regular operating hours. “The half-life of these drugs means they clear the system quickly, making timely testing necessary,” Brown wrote, which means students suspecting they may have been drugged should seek testing as soon as possible. Testing provided in the Student Health or Acute Care at Yale Health, including a standard drug screen and a specific test for Rohypnol, is included in Yale Health’s Basic Student Health Services, and is free for students.

For Jane, however, by the time she was well enough to leave her dorm several days later and had suspected something would be wrong, it would have been too late for a urine test at Yale Health.

More complex forensic drug screenings are not performed at Yale Health, but instead at Yale New Haven Hospital. Brown wrote that they are performed “only in cases where an assault has occurred or is suspected/possible (i.e., the person has no memory of what happened and/or does not have anyone to account for their whereabouts).” In such cases, tests are free of charge. If a patient is not a possible victim of assault, they cannot request extensive forensic drug testing panels. If someone, like John, Jane, or Jessica, wanted to know if they had been drugged, the emergency room would only provide testing for a limited panel of substances. In such cases, patients would be charged for their tests.

For the few victims of roofieing who could confirm they were drugged and might go to the police, crimes often remain unsolved. Rohypnol, along with many other drugs used to facilitate drink spiking, are illegal in the United States under the Controlled Substances Act. Drink spiking is a felony.

But at a party, identifying a drink spiker is nearly impossible. John, who is himself a fraternity member, described the safety mechanisms in place at fraternity parties. Many frats have a member who stays sober the whole time to monitor the party. When working at the bar, John was trained to identify who was drinking shots if one person requested multiple, but he said, “There are so many people that I can’t possibly always make sure that everyone’s okay.” Presidents from four Yale fraternities did not respond to email requests for further comment on safety measures in place.

After a party, identifying a culprit may be just as hard. John was contacted by a detective from the New Haven Police Department––he is not quite sure how they got his name, but knows other students who suspected they had recently been roofied at the same restaurant, Noa, and wondered if they might have come forward to the police. Police records indicate that the detective received the complaint three days after the formal, and began speaking to students within a week. Beyond a conversation with a detective, John never heard any updates on the case: “I don’t think they did anything, to be honest.”

John’s suspicions were essentially correct: police records from the investigation indicated that the investigator “did not develop any suspicion to believe the Noa staff had tampered with the complainant’s drinks or that they had knowingly provided alcohol to the minor complainants.”

Jessica did not consider reporting her suspected drink spiking after receiving positive results on the at-home drug test, because she didn’t think the incident could be feasibly traced back to any one person. “I feel like it would be a lot more mess and drama than we needed,” she said.

In an email, the New Haven Police Department wrote to me that they do “not have any statistical/ data reports available regarding incidents of drink spiking, drink tampering, or date-rape drugs.”

Police records from the investigation into Noa cited individuals declining to speak with investigating police officers out of concern “about being identified and charged for consuming drugs/alcohol as a minor,” or possessing or using a fake ID, a criminal offense in itself. Yale has a medical emergency policy, in which if students request help for themselves or fellow students in medical need, they will not face discipline from the Yale College Executive Committee. Nonetheless, the policy states that this amnesty does not “protect [students] from criminal or civil liability or prevent investigation or other action by federal, state, or local authorities, including Yale Police.” John, Jessica, and Jane were all drinking underage.

The act of drink spiking itself functions as an erasure—erasing John’s, Jane’s, and Jessica’s memories of their experience and stripping them of autonomy. Rohypnol and other drugs used in drink spiking make victims lose awareness, the capacity to make choices in the moment, and to remember what has happened to them. Jessica described the experience as “out of body, because you had no control.”

Without memory or clarity of what actually happened on a night out gone wrong, it’s difficult to tell one’s own story or understand who might be accountable. “I think it’s just hard not to blame yourself when it happens,” Jessica said. “It’s hard not to be like, oh, I should have been more careful about who I took a drink from, or I should have not done this or that.”

Ultimately, there are few protective measures in place. Ivatorov, who surveyed the student body, wrote to me that “It’s alarming that no harm-reduction measures have been standardized or broadly implemented that directly help students protect themselves,” including the NightCaps drink cover that she studied, or other drink testing mechanisms, like tester sticks, which are now required at California State University and California community colleges.

Police records from the investigation into Noa emphasized the importance of testing to substantiate the “belief” that a drink had been drugged. Without proof, the detective ultimately wrote that they had not developed any reasonable suspicion that the “experiences of altered mental status were caused by the malicious actions of another person/s.

In talking to John, Jane, and Jessica, it’s clear that the path to accessing tests is opaque and their availability is unpublicized. Not one of these three students knew that tests were available through Yale—for free. Without more testing and subsequent tracking of cases, it is impossible for students to know for certain what happened to them in frightening nights ending in memory loss and extreme sickness. Testing is also necessary for the Yale community to understand how prevalent this issue––which is certainly present in casual discourse––is in reality.

“Before I was roofied, I didn’t think that what happened to me would happen,” John reflected. Now, he’s more cautious when he drinks. But he’ll never really know what happened to him that night, or why.∎

Odelya Bergner-Phillips is a first-year in Timothy Dwight College.

The men in my ears clacked about The Iliad as I walked. I used to pause my podcasts and take out my earbuds when I went walking down Main Street, in case I saw someone. But today it snowed hard so I could not expect that, so I let them clack on about Greece, and the Greeks, and I laughed silently inside puffed cheeks numbed to the cold.

I turned the corner and began up the hill. Around a slight bend a woman was also walking, coming down. She was far; we walked, both knowing we would pass the other, and uncertain what to do in the interim. This knowledge crushed me like a tight squeeze of the calves, like the muscles in my thighs and in my calves were clamped and all the juices were drying up. My muscles became raisins; the men kept clacking, but I took one earbud out, for politeness; I kept my eyes down and pretended like my mind did not race. What if she spoke a cursory, pithy remark about the weather, about the snow and its falling like little powdered sugars from a donut God breathed on, about the funny little happenstance that two people might walk in such conditions? I needed pith in response. I have often lamented my failures in pith. The men clacked; the raisins dried themselves; I stared down and considered the footprints I knew I was leaving but never turned to see.

We passed each other. She smiled, and I laughed as if she said something pithy, and I stuffed the men back into my right ear and let them clack until I died.

Up the hill the road turns blind for a leftbound walker, so I crossed the street, like always: when coming up from town, you round the bend and cross at the treelog mailbox. And I crossed and began walking on her footprints. I knew they were hers; they were fresh, and it was snowing. They were small,

too, certainly smaller than my too-big expensive winter boots. I stepped in her footprints, stomped over them, clomped on half of one and none of the next. My boots were larger; my strides were longer; I felt a sense of conquest. A terrible, stupid sense of conquest knocked me on the head like an unwinking brick, and I picked it up and stared at it, waiting for it to realize itself.

Across Connecticut, researchers, farmers, and environmentalists grapple with the uncertainty of bird flu.

By Sarah Cook

On a chilly day in January, Jay Joseph stepped outside his backyard in Stonington, CT, to check on his four peacocks. At his feet, he found one of them dead with no sign of injury. He was mystified. Naturally, he turned to the internet. Someone suggested a duck could have broken the peacock’s neck, an explanation that seemed unlikely but plausible to Joseph.

The next day, he found three of his chickens dead. He sent his dead birds to a testing center at the University of Connecticut. The samples came back positive for bird flu.

Within forty-eight hours of the test result, Connecticut’s state veterinarian, Thamus Morgan, arrived at Joseph’s house with two Connecticut Department of Agriculture officials wearing hazmat suits. Within minutes, Joseph’s ducks, chickens, peahens, and peacocks, twenty-three birds in total, were put in gas chambers. “The ball just came down on us,” Joseph said.

He remained puzzled. Did they all need to die? Joseph, a hobby farmer who runs a contractor business, first brought home two peacocks six years ago after seeing the birds during a vacation in Puerto Rico. He grew fascinated by their

through contact with an infected animal. The virus spreads through saliva, nasal secretions, or feces of infected birds, and the symptoms in birds can include fever, coughing, nausea, muscle aches, and pink eye. Among poultry, fatal and highly pathogenic, spreading bird-to-bird, or through contaminated surfaces. According to Rebecca Eddy, Director of Communications for the Department of Agriculture, the mortality rate among domestic poultry is nearly 100 percent.

Given the high pathogenicity of the virus, the current response to a positive bird flu case in the United States and most countries, per standards from the World Organisation for Animal Health, is to kill the entire flock. Although bird flu is most prevalent among wild birds in Connecticut, the birds that are euthanized to stop the spread of bird flu are usually domesticated, like Joseph’s.

“There are a handful of exceptions, but with regard to public health, de-populating free-ranging wild birds is ineffective in addressing most public health issues and can have negative impacts on rare species,” Will Healey, communications director of the Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection, said. “Surveillance and biosecurity measures relative to domestic animals are the best ways to prevent the spread of the virus.”

While H5N1 was first identified in birds in China in 1996, an especially virulent subtype of highly pathogenic avian influenza called clade 2.3.4.4b emerged in North America in 2022 and began spreading rapidly. Since 2022, there have been seventy cases in humans. The risk of spreading between humans remains low. Yet as the virus spreads, it can mutate into more contagious variants, infecting humans at higher rates. Such a mutation

Joe’s and other grocery stores recently placed limits on egg purchases). On the national level, in late February 2025, the Secretary of Agriculture, Brooke Rollins, announced a one billion dollar strategy to take on HPAI, including economic relief for farmers, investments in biosecurity, vaccine import, and support for temporary import of eggs to lower prices. A single bird flu case could wipe out an entire flock––an event which would be particularly detrimental on large poultry farms, like Hillandale Farms in Connecticut, which produces eggs for Eggland’s Best. Large farms disproportionately control egg production (in the U.S., the top five egg companies, which include Hillandale Farms, own about 46 percent of laying hens).

In Connecticut, there have been four confirmed cases of bird flu in backyard flocks: two in 2022 and two in 2025, as well as about eighty-two cases in wild birds since 2022, though none in livestock so far. In the U.S., since 2022, there have been 12,706 wild birds that have tested positive for bird flu, and one hundred sixty-eight million poultry affected. By population, the density of wild bird flu cases is roughly 75 percent greater across the country than in the state of Connecticut.

One case, though, can wipe out an entire farm. Bird flu is not preventable, and there is no current cure. While cases in Connecticut are still low, if the virus spreads, more farms run the risk of seeing what happened to Joseph’s birds: mass selective slaughter.

Indu upadhyaya, a food safety expert at the University of Connecticut, works to educate local residents on biosecurity recommendations for bird flu. As backyard flocks have shot up in popularity since COVID-19, perhaps in response to the ongoing egg shortage, Upadhyaya’s current recommendation to residents is to avoid contact with waterfowl, which can be breeding grounds for HPAI infection.

HPAI in birds can present with sudden death, like Joseph observed, as well as symptoms like swelling, respiratory problems, or uncontrollable diarrhea. If any of these symptoms are present, Upadhyaya recommends sending samples off to Connecticut Veterinary Medical Diagnostic Laboratory. But currently there is no cure or vaccine. According to Upadhyaya, if a positive result comes back, the only option is killing the entire flock, a practice known as culling.

At the federal level, Robert F. Kennedy Jr., Secretary of Health and Human Services, has emphasized biosecurity over culling, arguing birds should not be killed but rather given time to build up immunity. Immunity to bird flu, however, would require prior exposure to a mild strain or vaccination, Upadhaya said. In the U.S., vaccination is not commonly used in backyard or commercial flocks, and birds, regardless of their lifespan, remain susceptible to new infections without controlled exposure or vaccination.

Even with testing centers, Upadhyaya worries that “viruses and bacteria are extremely smart.” There may be even more cases than reported, in animals or in humans. The virus can mutate and reorganize itself in many ways, and it may become more pathogenic in the future.

This uncertainty is making poultry farming, already a difficult profession, even more challenging. Extreme weather caused by climate change has made the job unpredictable. And while chickens are typically thought to be more controllable than crops, with bird flu, farmers could lose their flock any day. “It’s piling on,” Ella Kennen, coordinator at the New Connecticut Farmers Alliance, said.

to raise for eggs, but said that due to the increasing risk of bird flu, the price was 50 percent more than it would have been last year.

Bird flu, to Kennen, remains a looming fear— “the pendulum swinging over your head and you’re just waiting for it to drop that balance.”

At the New Connecticut Farmers Alliance, Kennen works primarily with new farmers in the first ten years of their careers. Though no case of bird flu has been reported in Connecticut livestock, the threat of H5N1 still hangs over farmers. One bird flu case could jeopardize an entire flock, and chickens take time to raise.

If an entire flock of chickens is killed, it could take weeks or months to recover a flock. “Birds get the short shift,” Kennen said. Chickens on farms are labeled as “broilers”—chickens raised for meat—and “layers” raised for eggs. Broilers take about six to ten weeks to mature, but layers need up to six months to reach reproductive maturity. Since the current outbreak began in 2022, 148 million birds in the United States have been ordered to be euthanized, collapsing farmers’ years of work.

It is more costly to buy flocks now, too. Farmers usually purchase pullets, birds almost at reproductive maturity, or day-old birds, and the prices of both are on the rise. Murray Gates, from Artza Mendi Farm in Baltic, Connecticut, recently bought five hundred chickens

For diverse and smaller farms, the economic risk of losing a flock is lower than for industrial poultry farms. For diverse and smaller farms, like most Connecticut farms, Gates explained, risk is spread out among revenue sources. “If you’re a large farm, all of your eggs are in a single basket.” Small farms, though, have less profit and less of a cushion for large losses if a single flock gets wiped out. Most farmers, including Gate, already work multiple jobs on top of farming.

Steadfast Farms in Bethlehem has Connecticut’s only USDA-approved poultry slaughter and processing facility, where they expect to slaughter fifteen thousand to thirty thousand chickens this year for other farmers in the greater New England area. Despite national concerns about bird flu, starting this year, the farm is adding three thousand chickens and 350 turkeys. Aaron McCool, the farm’s director of operations and sales, said the farm has always practiced biosecurity. “Anyone who raises poultry commercially thinks about avian influenza in

the same way that every human thinks about a cold sometime in their life,” McCool said.

Steadfast Farms is also a member of the National Poultry Improvement Plan, or NPIP, which is a program that regularly tests for illnesses such as bird flu and pullorum, diseases which could lead to the farm depopulating its birds. NPIP would provide economic support in case of depopulation.

In recent months, McCool told me that Steadfast Farms has increased their spending on biosecurity necessities by 15 percent. When they suspect a bird is sick, they isolate it from the others and change their boots and outfits between visiting different species.

Still, McCool explained that no matter how much Steadfast Farms spends on biosecurity, they cannot control bird flu outbreaks. “No matter what you do, avian flu is not a preventable disease. All it takes is one duck flying over with a dropping.”

THe connecticut audubon society has twenty-two sanctuaries stretching over three thousand four hundred acres.

Tom Anderson, the director of communications for the Connecticut Audubon Society, told me that H5N1 is not their biggest concern. In the last fifty years, the number of birds in North America has dropped by three billion, or 30 percent, due to construction and domestic cats, along with pesticide use and building collapses. “Avian flu is not even on the radar compared to those others,” Tom assured me. I wondered how he felt about the media attention bird flu gets over these other concerns. Tom defined it as an issue of attention. “Four billion birds dying every year because cats kill them is a big problem. But it’s hard to write or broadcast a news story about that,” he said.

Similarly, at Steadfast Farms, McCool says he is less concerned about bird flu than with feeding people. “Avian influenza is not new, but this national story is new. We always ask why the negative stories about what could happen become so popular, instead of the stories about what these local farms do for their communities, how they give back, and how they serve the people that they feed.”

While bird flu might not be the primary worry for Anderson and McCool, for Joseph, he cannot forget.

After news coverage of his bird flu case, Joseph receives messages from across the country from people asking if he wants them to send him new birds. He appreciates the outreach, but is reminded of the loss of his birds whenever he looks out on his backyard. He took the pump out of the pond where his ducks used to swim and let the pond freeze over. “The backyard is dead now,” he said.∎

Sarah Cook is a senior in Grace Hopper College.

A New Haven activist, Yale doctor, and Yale lawyer won Americans the right to oral contraceptives as part of a liberating—and eugenic movement. Today, patients and doctors still confront the tension between autonomy and coercion.

In the spring of her senior year of high school, Asha Goyal ’27 made an appointment with her doctor at home in Los Angeles, CA Each month of that year, she had spent five days out of commission. She was nauseated. Her temperature fluctuated. She had joint pain, and back pain, and stomach pain. Her period could not be subdued by any amount of Advil or number of hours spent clutching a heating pad to her abdomen. She told her doctor. He told her to tolerate the pain––to wait until she was 25, when her body would “mellow out.” Asha, 18 at the time, did the math: she would spend eighty-four weeks of the next seven years in pain. “That’s nearly two full years of my life that I’m going to be miserable,” she said on the patient table. “And I’m supposed to wait it out?” Her doctor was silent.

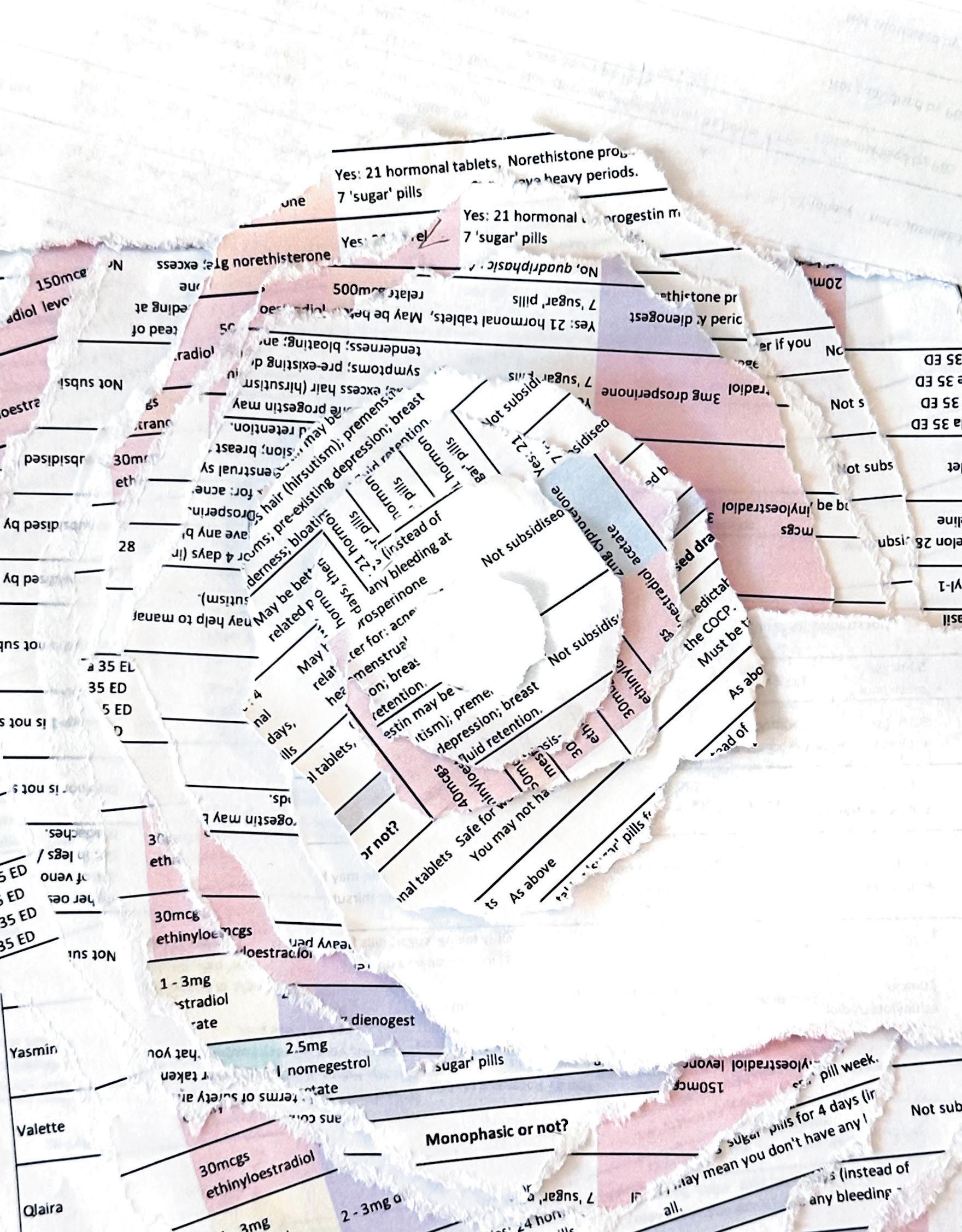

In the absence of satisfying medical advice, Asha’s mother made a common suggestion: might she try a birth control pill to regulate her cycle? Asha figured it was worth a shot. She knew friends who were taking oral contraceptives. Some took pills with both estrogen and progestin—hormones that suppress ovulation and regulate menstrual bleeding––and some took pills with only one of the two hormones. In February 2023, during Asha’s freshman year as a mechanical engineering major at Yale, her new doctor at the Yale Health Center prescribed an estrogen pill.

Then Asha got her period. It lasted fourteen days. Her doctor said to give her body three months to adjust to the pill, and suggested skipping the five placebo pills at the end of her pack, which typically induce a period. But Asha got her period again in April. It lasted thirty-five days, until the end of May. She had worse mood swings, pain, and acne than ever. When Asha went back to her doctor before leaving for her summer study abroad program, her doctor said to give it six months. A week after the appointment, she had another painful, fourteen-day period. “I think I spent like 40 percent of last year bleeding,” Asha says.

She spent about the same proportion of her time crying. Three weeks in, as Asha packed for spring break, she was overcome by a foreign, persistent sadness. She cried through her study abroad

Illustrations by Mia Rose Kohn.