Masthead

Editors-in-Chief

Juju Lane

Mina Quesen

Publisher

Abigail Glickman

Alumni Liasion

Allie Matthias

Managing Editors

Sam Bisno

Sierra Stern

Design Editor

Cathleen Weng Senior Editors

Lauren Aung

Lara Katz

To Our Community

On October 20, we learned of the death of our classmate, Misrach Ewunetie. In the last year, we have mourned the loss of Jazz Chang, Justin Lim, and Kevin Chang. In the face of such tragedy we have chosen to leave the cover of our magazine blank. We cannot faith fully portray the preciousness of life nor the depths of grief on our campus today.

The works within this issue were created before the loss of Misrach.

Our thoughts are with you.

Juju Lane and Mina Quesen Editors in Chief

Junior Editors

Lucia Brown Kate Lee

Anya Miller

Zoey Nell

Charlie Nuermberger

Alexandra Orbuch

Art Director

Emma Mohrmann

Assistant Art Director

Hannah Mittleman

Assistant Design Editors

Vera Ebong Hazel Flaherty

Head Copy Editor

Andrew White Copy Editors

Bethany Villaruz

Noori Zubieta

David Edgemon

Teo Grosu

Events Editor

David Chmielewski

Audiovisual Editor

Christien Ayers

Web Editor

Jane Castleman

Social Chair

Kristiana Filipov

Social Media Manager

Ellie Diamond

This Week: About us:

Mon Tues Wed Thurs

5:00p East Pyne (An)archiving the Carib bean: Matters, Methods, Meanings

4:30p Burr

Mari Carmen Ramírez & Josh T. Franco | Latinx Archives in Context

4:30p ZOOM Being LGBTQIA+ In the Workplace

7:00p Green UCHV Film Forum: Jor dan Peele: Nope (2022)

5:30p Art on Hulfish Artist Conversation: Dawoud Bey

4:30p McCosh Meibutsu and the Formation of Japan’s Artistic Canon

5:00p Art on Hulfish How Museums Are Diversifying Their Collections to Include Black and Brown Artists

Verbatim:

Hungover in a Roman piazza

Futurepopstar/German professor: “What really drew me to Glee was the pregnancy. The prospect of a teen pregnancy.”

Overheard in Gateway Arch gift store

Publichealthaficionado: “James? John? Tony... Anthony. It’s Anthony Fauci.”

7:30p Richardson Brentano String Quartet

Overheard over text Athinker: “iPhone and Android users really do perceive reality differently.”

Overheard on Frist 1st Floor ChristianGroup,to unsuspectingstudent: “Do you want prayer?”

On the porch at Ivy Asophomorewithoverly dilatedpupils: “The way to make friends at Ivy is with cigarettes, ket, or cocaine.”

The Nassau Weekly is Princeton University’s weekly news magazine and features news, op-eds, reviews, fiction, poetry and art submitted by students. Nassau Weekly is part of Princeton Broadcasting Service, the student-run operator of WPRB FM, the oldest college FM station in the country. There is no formal membership of the Nassau Weekly and all are en couraged to attend meetings and submit their writing and art.

5:00p Princeton Neuroscience Institute Artist Conversation: Roberto Behar and Rosario Marquardt

Fri Sat Sun Got Events? Email David Chmielewski at dc70@princeton.edu with your event and why it should be featured.

All Day 185 Nassau Fall 2022 Drawing Classes Show 7:00p Chapel Diwali at the Chapel 7:00p Seminary Chapel Vocal ensemble performance by

11:00a West Windsor Temporary Field Women’s Rugby Game

2:00p McCarter

Princeton Triangle Show: Campelot: It’s In-Tents.

For advertisements, contact Abigail Glickman at alg4@princeton.edu.

Overheard in Murray Dodge MidtermstudierandRoma hater: “Who eats fish in 2022?”

Overheard in dorm Disillusionedromantic: “Having to care about your significant other’s mental state is so exhausting.”

Overheard while watching Breaking Bad BreakingBadfan1: “Who’s piss is that and why do they drink so little water?”

BreakingBadfan2: “That’s Walt and he has cancer!”

Overheard before class CuriousStudent: “What is your book about?”

Professor: “Who even knows.”

Overheard in Roma GirlA: “You called me during chemistry lecture that you should have been at!” GirlB: “I was at Ralph Lauren... I bought the cutest throw blanket...”

Submit to Verbatim

Email thenassauweekly@gmail.com

Read us: Contact us: Join us:

nassauweekly.com thenassauweekly@gmail.com Instagram & Twitter: @nassauweekly

We meet on Mondays and Thursdays at 5pm in Bloomberg 044!

Cure Plant Blindness and Find Community: Meet the Princeton Locals Revitalizing Herrontown Woods

By JUJU LANE

By JUJU LANE

In an overgrown garden in suburban New Jersey, a roost er perches atop a tree stump with his beak open, to let out a crow. A large disco ball rises from the rooster’s back, refract ing the morning sun.

This particular rooster hap pens to be a copper sculpture, in a permanent art installation.

But just imagine if he were a real, live disco rooster—he would probably crow the tune of ABBA’s “Dancing Queen” at dawn. And maybe he does, because in the Botanical Art Garden at Herrontown Woods nature preserve, everything is possible.

There are just two guidelines here: first, be respectful of the earth, but certainly add some

magic of your own if you’re so inclined; second, be sure to call the Botanical Art Garden by its nickname—the Barden—so the locals know you’re one of them.

The Barden is the heart of Herrontown Woods, a 142-acre public arboretum in northeast Princeton, NJ, with three miles of crisscrossing trails. I visited on Sunday in early October, to check its pulse. The Barden was pumping vigorously.

caretaker of Herrontown Woods and curator of the Barden, greeted me like an old friend. He wore a hat with long plush flaps that drooped past his shoulders like bunny ears. “If you find a corner of the Barden that speaks to you,” Thornton told me, “you can make it yours, and create something there. We have a Fairy Garden, and someone’s been working on building Troll Mountain.” He kicked cheerfully at the wood chips beneath him. “It’s all very whimsical!”

Nicole Bergman, a Princeton resident, stood at a rustic kiosk selling hot drinks and baked goods in her monthly pop-up, May’s Barden Café. Proceeds go toward restoration projects in the woods, she said. (Coffee’s three bucks a pop, but Bergman throws in a big smile for free.) Overhead, sunlight glittered through the yellow leaves.

Andrew Thornton, the

Locals mingled around the gazebo, wearing fleece vests and hiking boots, steam spi raling from their travel mugs. The parking lot was full. Two little boys hunched in a repur posed garden shed playing the board game Stratego. A group of volunteers was busy collect ing and cataloging seeds from the native wildflowers in the Barden. “Do you have a label for

A foray into the wilderness of suburbia.

the swamp mallow?” someone asked. “You bet I do!” came the reply.

Among the memos on the Barden’s community posting board: a list of local birds, a flier for a concert by The Chivalrous Crickets, and a sign declar ing, “Our Vision: Herrontown Woods is a preserve where peo ple of all ages explore, enjoy and learn from nature to enrich their lives, and to become its stewards.”

Next to that, a donation box and a bottle of bug spray.

become a vocal advocate of plant literacy at Herrontown.

“I’m trying to bridge the gap between physicians and the natural world,” said Regan, as she marched me through a garden path. Working close ly with Hiltner has given her a whole new perspective. “I call botanists ‘the physicians of the earth’ now,” she said.

Regan also started to recog nize the limits of sporadic vol unteering. “When you go out and do a volunteer day,” she explained, “you go home and then you kind of forget what you learned.”

Have you ever strolled through a New England wood land and admired the drap ing purple blooms of Chinese wisteria in spring, or the vivid flares of burning bush in au tumn? Were you blissfully un aware that these pretty plants are aggressive invasive species?

If this sounds familiar, you may suffer from what Dr. Inge Regan calls “plant blind ness.” But rest assured, Regan and her fellow volunteers at Herrontown Woods are on a mission to provide the cure.

The Friends of Herrontown Woods, a cohort of greenthumbed and eco-minded Princeton locals, gather in the woods every weekend to main tain the trails, restore the native ecosystem, and find ways to en gage the community. They are led by botanist Steve Hiltner, the group’s president.

Inge Regan, who practic es emergency medicine in Princeton, found common ground with Hiltner in the language of science. She has

To provide community members with the lasting skills needed to combat invasive species, Regan launched the Invasive Species of the Month Club in August. The club, which now has 25 members, studies specific invasive species and works in Herrontown’s forest and garden to remove them.

Regan previously suffered from “plant blindness” her self, she said. When she start ed working in the woods, she tried to assist Hiltner by re moving invasive stiltgrass from Herrontown’s Barden. She soon learned the risks of weeding with an untrained eye.

“I’m like, ‘Steve, look, I got all this stiltgrass!’” Regan re counted, gesturing to an imagi nary pile of grass. “And he goes, ‘That’s not stiltgrass! There are twenty different kinds of grasses in here.’” She shook her head in mock exasperation and laughed. “So I had to re-study!”

Regan has come a long way

Sneezing fits of overgrown unruly grass thieves of my senses weed corpses and branches of tar embracing the bare skin of my legs

caressing my ankles

pebbles trip me I trudge forward on chalky sand dirt painting my arms

the sun scorching the bridge of my nose the strip of skin beneath my hairline clutching the space between my dainty silver ring and index finger

I wipe the glaze from my face lift the socks above the red marks on my ankles

I fiddle with the silver my skin soaked erasing the sun’s sketches from my skin but the weeds still puncture my dirt-streaked fabric and embrace me

BATTLE WITH NATURE

By ALEXANDRA ORBUCH

By ALEXANDRA ORBUCH

The Brooklyn Art Salad: Mold, Tulips, and Kale

By MINA QUESEN and GAWON JO

By MINA QUESEN and GAWON JO

Apparently, when the rain falls in New York, the sewage overflows. That is, the overpowering amount of sewage becomes too much for the poor drainage and sanitation system to handle. Unfortunately, the city doesn’t know what to do with it, so they dump it into the nature-born, man-created trash bin that is New York’s harbor. While this might not have much to do with our story today, it is on the shores of this harbor that we begin, stepping into an abandoned military production facility.

The facility is now a biotech lab, like the ones you see in Into the Spiderverse—long,

brightly lit hallways with a maze of red and white pipes attached to the ceilings and observation windows where visitors and supervisors wandering the BioBAT can creepily stare at the scientists from Sweden, who wave back hesitantly when they catch your eye. The BioBAT is a SUNY-funded lab space located in the Brooklyn Army Terminal for start-ups to pursue both business and research endeavors. Our trip, however, is not to focus on the labs but the art space on the first floor where bio-art exhibits fill the white walls and blend scientific research with artistic presentations. Currently, “Vibrant Matter” an exhibit by Yoko Shimizu and curated by Elena Soterakis is on display.

In the bottom of this facility, concrete pillars line the basement, where, long ago during World War II, parts for tanks and other machines of war and destruction were brought in by train or boat. Now it seems eerily empty. The space is almost

cleared out—a pile of dust there, a piece of wood here—and three white lattice-like sheets of paper, each the size of three of our classmates. The paper is not really paper. Or rather, it is paper, in the material sense, but the pattern is that of Luna, a slime mold. This is a gallery space in progress, and as we sit in the half-dark, Elena explains to us that once it fully opens, the basement will be devoid of light except that which is needed to illuminate the bio-art. In some cases, the bioluminescence of the art itself, as the artist works with the bio-material live, will offer the source of light.

As we emerge from the basement, we step into the lobby, which is ever so slightly tilted, giving the room an offkilter effect, which is only enhanced by the crooked lights and the only thing properly 90 degrees from the ground — the chandelier of glass test tubes. This too is a gallery space, but one designed around the use of the lobby as a place where

“The multi-media nature of the work invites viewers to do more than just reflect on what they see: to engage with it through their own experimentation.”

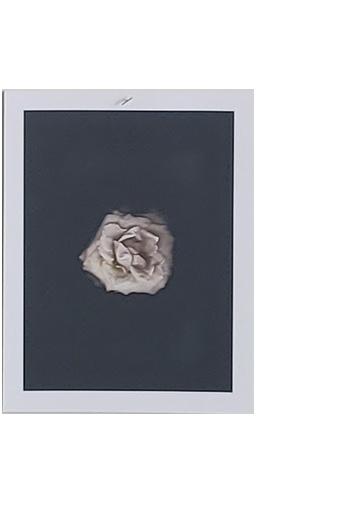

large amounts of equipment, deliveries, and (surprisingly enough) children from BioBAT’s pre-school pass through. None of the artwork is particularly fragile, and most of it is printed on glossy paper featuring black backgrounds with vibrant flowers. The work displayed here is in conversation with the science being practiced and discovered upstairs. Yoko Shimizu, a Japanese artist based in Austria, is a researcher who works at the intersection of biology and art, using each field to build on the other and inviting the audience to look beyond the binary of the artistic and the scientific.

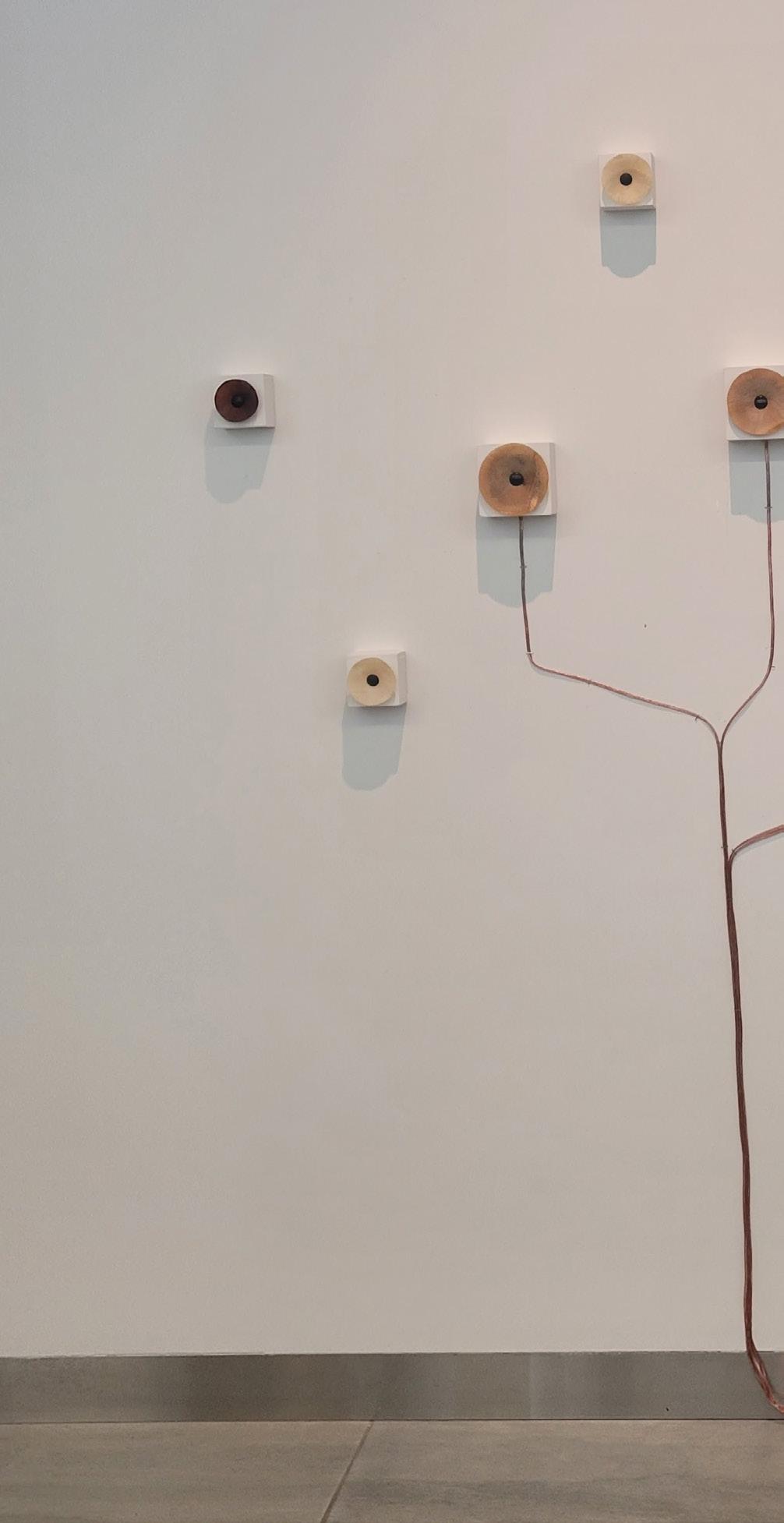

The exhibit utilizes its white space to emulate the lab spaces above. Shimizu’s dissected flowers, bright blooms on black backgrounds, are lined on the walls, pages stuck up with tea pins like notes on a board or subjects pinned down for dissection. Other pieces are framed, joined by large screens playing time-lapse videos on loop. Framed by two industrial pillars is a set-up of mycelium speakers, trailing copper wires

like veins down to an audio port for someone’s phone to play jazz music. The sound is richer, warmer, as it comes through the mycelium. One day, the gravitydefying tulips will hang in front of the massive window in the lobby, completing phase 3 of the gallery’s plan for this exhibit. However, where most galleries focus on framing final pieces and inviting people to engage only with a “finished” product, BioBAT’s exhibit highlighted not only a series of finished experiments and pieces but the process which went into the work’s creation. The multi-media nature of the work invites viewers to do more than just reflect on what they see: to engage with it through their own experimentation. Our tour of the exhibit included in-depth explanations of the scientific process behind each piece, which also included several tables where the supplies to recreate the art were left for the attendees’ own curiosity. At the water-filled flask chandelier, you could fill your own flasks and test tubes with a pipette. At the image-printed leaves,

kale plants were left under a UV lamp and a bottle of iodine was waiting to be used. A screen ran through a video explaining how the image was processed like in a darkroom for photography.

These moments of interactive opportunity are more common in science museums, yet here the invitation to reproduce the work did not diminish the beauty of Shimizu’s creation. Later in the tour, during a glimpse of an upcoming extension of the exhibit, David explained Shimizu’s work to be, by nature, interactive. It is one of the themes she is primarily concerned with. As science and art blend together in the BioBAT, the fusion opens a larger question about the accessibility of art in the first place.

At the Tate Modern Museum in London, where contemporary exhibits accentuate a collection of modern art, the only in-depth explanation of process was in a temporary exhibit about Aboriginal art in Australia where they followed the

I wished that it could always be like this: Jaaskelainen me, the

traditional craftsmen and revealed the processes behind the work’s creation. While highlighting Aboriginal work and highlighting Britain’s colonization of the land, the curation choices create a message which focuses on education and revealing generational knowledge that is passed down. It also in a way diminishes the work in traditional views of art. Art as an idea values originality, the ability to show something never seen before. Suggesting replication in a gallery is to infringe upon the greatness of the work, the reason why the piece exists in a museum space in the first place. For this very reason, I suppose, process is less important than the final piece and to include videos of process is to thus diminish the value. It reveals the disaster that comes before creation and unveils the fact that the artist is just as human as the viewer. The finished product masks the

errors, drafts, and re-boots; it erases the very work that goes into the piece, resulting in the snobbish, “I can do that.”

It’s a tricky outrage that sparks from the saying, “I can do that.” On one level, it’s a lack of recognition of art as a labor and a career, belittling a skilled craft and the work that goes behind it. Yet, BioBAT is asking a question at the root of the insult: Why can’t we do that? And not in the sense of what physically prevents us, but in the unspoken rules of art, why aren’t we teaching process alongside masterpieces? Master studies—a reproduction created to learn from canonical artists—are a crucial element to learning a craft in the first place as an art student. Yet, the budding artist’s grit is seen not in learning technique but in looking at a piece and determining from typically sight alone how to recreate it.

Bio-art challenges this idea. The very nature of science is to

create replicable process and results. Weaving in this concept to the exhibit defies gallery tradition and changes the power dynamic of a passive viewer and a master-created artwork. It also invites art spaces to think about reproduction as a starting ground. To experiment with Shimizu’s techniques are not to recreate perfect reproductions of the work, but to learn the technique and hopefully expand beyond it—to become excited enough about both science and art to continue chasing down new ideas. It opens the question of what the art world may look like and who could be included in it when we think of galleries as thinking and learning spaces as much as showcases of finished work.

Visitors and supervisors wan dering the Nassau Weekly can creepily stare at Mina Quesen and Gawon Jo, who wave back hesitantly when they catch your eye.

BURNING

By SOFIIA SHAPOVALOVAThe words on the page burned her.

Somehow, the decep tively clever arrangement of terms and blank space trans formed a rather abstract con cept into something very real and very powerful inside her as the reader. She could feel the words’ effect blazing in side her, her heart hammering in her chest and her breathing growing more rapid by the sec ond as her eyes raced across the gleaming page. The need to keep on reading was an un yielding wildfire. If she man aged to tear her gaze away for even a moment to remember her surroundings, she could feel herself being pulled back

in just as the heat of the flame demands an intuitive close ness. She could not wrap her mind around precisely how such enchantments were fash ioned. How did a mere mixture of pigments and solvents print ed on wood pulp manage to ignite such scorching emotion within her? How had this book laced with fragments of po ems transcribed by an ancient writer happen to survive all the harsh tests and trials of time to find its way to her hands now? It was, she felt, unexplainable, and tragically so, the incom pleteness of the story leaving her boiling with questions.

She moved her hand to turn the page and marveled at how it seemed like it did so of its own accord. The book had seared a gap between her mind and her body. She had not thought to turn the page at all. Rather, some part of her had intuitively

known that this was the action that needed to be fulfilled in order to satisfy the reader. She thought then that reading, for some, must not be so very dif ferent to drinking or smoking. The urge to devour the book as quickly and wholly as possible was a relentless desire of hers. She craved the literature. The more she read, the more criti cal it was for her to find some thing else to fill her empty soul. At once, she felt herself grow stronger and weaker as the in tensity of her addiction con tinued to amplify. The burn ing never ceased. Yet, it was a pleasant kind of pain—her signature brand of masoch ism. It felt good to simply feel something.

The book in front of her was intoxicating in its subject man ner especially. It so happened to deal with, in the reader’s opinion, the most delicate and

“The need to keep on reading was an unyielding wildfire.”

central of all human matters— love. It hurt her to read the writ er’s longing. To feel the tender warmth of the adoration the writer described and know that such love was only found among the pages. Everything seemed so much less compli cated in the gentle embrace of a book’s cover. It was as if she were looking at life through a filter in which everything was splendidly radiant. The doting worship the writer expressed seemed almost unattainable, and yet, the reader knew that this love had been vastly real in another time and place. That, she thought, was what cut her most of all.

A true love that had been lost.

The writer mourned, and the reader mourned with her. She sensed that no one besides her own self and the writer of the text ever had or ever would un derstand the extent of this love.

For the love had been unknown by whom it had been intended for. It was the love of shadows, always lingering in a curious state of limbo that could be felt but not touched. The read er felt it now, and, as her hand made to move towards the page of its own will again, she want ed nothing more than to touch the love too. To give tangibility to the emotion that made it dif ficult for her to breathe and do anything but keep reading. She felt herself grow hotter, almost uncomfortably so. She realized she was crying too then, the coolness of a teardrop sliding down her chin and making a soft plop on the page showing her just how very real the burn ing was.

How real her pain was.

The urge to devour the Nassau Weekly as quickly and wholly as possible was a relentless desire of Sofiia Shapovalova.

REMEMBRANCE, NOT RECOLLECTION

By ADAM HOFFMANAn unresolved mind might settle upon a lecture given to the American Historical Association by an Ivy League professor as the au thoritative voice on the role and purpose of a historian. So was the case for me. As president of the American Historical Association, Carl L. Becker delivered an address titled “Everyman His Own Historian,” in 1931 with the explicit goal of reducing history “to its lowest terms,” just in the same way a mathematician might simplify a fraction. He concluded that history “is the memory of things said and done.” A histori an “does a bit of historical research in the sources,” to “establish the facts… always in order.” I dare say that I feel unresolved with Becker’s answer. His description of a historian does not align with my ex perience and engagement with the memories of the past. Becker’s historian is at home in musty libraries

and archives; I am most comfortable remember ing the past around a fam ily dining room table or in the pews of my synagogue. Indeed, I am not the type of historian that Becker char acterizes, and it is a func tion of my remembering in concert with others rather than as an isolated individ ual that separates me from him. My history is a collec tive practice.

The individualist char acter of Becker’s history is evident from his argu ment. He illustrates his point with a story about Mr. Everyman, an arche typal American man in the 1930s. Mr. Everyman makes use of the documents he has at hand— a note in his vest pocket—to determine the amount of money he owes Mr. Smith, which, in turn, provokes a memory of his exchange with Mr. Smith. After he compares notes with Mr. Smith, it is revealed that Mr. Everyman did not complete his pur chase, and no money was owed. Though he initially misremembers the series of events, evidence enables Mr. Everyman to set the record straight. Later, he comes to remember that he owes Mr. Brown a debt and proceeds to make a

payment. The method of discovery and conclusion that Mr. Everyman uses to engage “things said and done” certifies him as a historian. “If Mr. Everyman had undertaken these re searches in order to write a book instead of to pay a bill, no one would think of denying that he was a his torian,” Becker says. From start to finish, Becker’s his torian works for himself and by himself, with the ex ception of an instrumental encounter with Mr. Smith. This historian acts as an in dividual and treats the past as relevant to an individu al’s need. “It is… an imag inative creation, a person al possession which each one of us, Mr. Everyman, fashions out of his individ ual experience, adapts to his practical or emotional needs, and adorns as well as may be to suit his aesthetic tastes.” This conception of history can exist as a oneman show.

Mr. Everyman’s experi ence with history is strik ingly different from my own. I believe myself to be a historian at least one night a year when I observe the Passover Seder, the rendition of the Biblical Exodus narrative accord ing to Jewish traditional

rite. On the Seder night, I gather with my family to re member what was said and done by God for the Jewish people in Egypt. According to medieval Jewish philos opher Maimonides, a Jew in the Temple was forbid den from conducting por tions of the Seder alone. Together, my family aims to study the Exodus story and fulfill our Rabbinic obliga tion to “view ourselves as if we, ourselves, left Egypt.”

We decorate our table with faux slave laboring mate rial—an apple cobbler to represent brick mortar and salted water to commem orate tears—and fuss over the meaning of God’s an cient commandments. Our task is to imagine ourselves in the past, regardless of its authenticity. Indeed, at no point in the traditional Haggadah, the Seder guide book, is the reader instruct ed to compare its sequence of events with the records of the Egyptians and at no point do the Haggadah’s au thors attempt to legitimize their historiographical methods. To do so would be to defeat the intention of the Seder night histo rian. On the annual eve ning when I am most con fidently a historian, I join with others to experience a

A writer reflects on history as a collective pursuit in his Jewish tradition.

collective past which might have never even occurred. My history is unthinkable as an individual.

The comparison be tween Becker’s historian and my evening as a histo rian is of course disjoint ed; one is, effectively, a metaphor, and the other, a ritualistic practice. One is troubled to draw any imme diate lessons from the com parison. Luckily then, as literary critic Adam Kirsch has written, there are his torical instances that were captured by historians of Becker’s character and of my tradition. Kirsch pro vides the Jewish War of 66 73 C.E. and the destruction of the Jewish Temple as the paradigmatic case of the two historians coming to a head. The history of these events was transcribed by both Josephus and the Talmudic Rabbis.

Josephus, who chroni cled the events of the Jewish War in his so-titled work, was a Judean trained in the Roman historical methods and can be fairly described as a Becker historian. As Kirsch writes, “Today, all historians derive most of

what they know about these events from Josephus.” The Jewish War is a relatively dry account of the “complex political, military, dynas tic, and religious reasons for the Jewish defeat.” He determines that “the dead ly rivalry between political and religious factions” was the cause of the Jewish War. Though questionably rig orous, he engages in his toriography similar to Mr. Everyday. The Talmudic Rabbis offer a radically dif ferent presentation of the Jewish War. In their repre sentation, the Temple was destroyed because of a spat between two men. A man by the name of Bar Kamza was mistakenly invited to his enemy’s party. After his en emy disinvited and shamed Bar Kamza from the party populated by the Rabbinic elite, Bar Kamza sought re venge on the Jewish people by orchestrating a ploy to frame the Judeans as rebel lious Roman citizens. The result was the destruction of the Temple and Jewish self-rule.

Kirsch summarizes the difference between the two accounts well. “

Interestingly, this is es sentially the same verdict that Josephus delivers, ex cept that, instead of a per sonal dispute over a party invitation, he talks about the deadly rivalry between political and religious fac tions… The Talmud story condenses these complex events into a usable moral lesson. That is how the past turns into living memory, even at the price of falsifi cation.” Josephus prioritiz es the truthfulness of this historical event while the Rabbis prioritize the effect this historical event could have on their audience. In the scheme of things, the two paths end up in very similar places.

Between the com parisons of Mr. Everyman to my family at our Seder and Josephus’s The Jewish War to the Talmudic tale, we can begin to understand the essential difference be tween Becker’s historian and my own. Mr. Everyman steps into the past in order to probe for the truth. His debts and payments depend on the facts of his past loans and purchases. The truth fulness of the past events,

from which the endeavor of history derives its value, can be absolutely settled by Mr. Everyman’s memories and historical evidence. All of his problems would be solved with a time ma chine. The same is not true for my historian. According to Professor Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi, when my his torian “‘remembers,’” it means that “[history] has been actively transmitted to the present generation and that this past has been ac cepted as meaningful.” The Jewish historian finds value in history’s relevance to the present, which can even be divorced from truth. The Jewish historian draws memories from the past to put it on exhibit for others. History is about lessons and morals for the present. The Jewish historian wouldn’t bother with the historiog raphy of Mr. Everyman; she would only care about how others will remember.

What is it that al lows Judaism to become this “vehicle of memory,” as Yerushalmi described

Remember-Reels

by audrey zhangAlight

Pink Punisher butterfly birthday skateboard with fine-tuned wheels, asphalt burn like a meteor impact, tears as briny as Fire Island’s ocean, a phoenix sunset, Blazing sugar by embers that redden the forest, caught between graham crackers, granite benches, an inferno in the rib cage, beneath the eyes, in the hands that guide the torch Over the obsidian-fuschia metal, a ram forged from salt and smoke

Awake

Petrichor from the oribe green ferns, fallen yellow peaches among shamrocks, Memorized banana bread with 85% dark chocolate and sweet walnuts, as warm as dawn parting cherry leaves and mist, A solemn yet sunny French song—naïvité, crinkled notebooks tattooed with grammar rules, dark purple figs outside four window panes in the paws of a raccoon, beneath a velvet navy sky

Afloat

Koi fish dancing beneath lily pads, sipping on green sunlight, goddess dress by golden grass, by roaring seafoam

Rain that drenches and pulls laughter from our bellies beneath the starlight Hot lemon ginger tea in a hand-painted dragon cup, the cool night Pistachio matcha by the sepia photographs, a lullaby of longing, of lost love

Aware

Wire and paper maché molded into a bust with metal fingers and a single paper eye, unseeing, an unintelligible poem of musings never to be sent, unleashed, An almost smile, half-moon marks on the palm, freed like dragonflies in the dusk dust, a hummingbird heart in front of him, the golden hair that captivates—the inexplicable allure

An excited, quiet, contained cheer, unremembered but not unfelt

in recognizing both native and invasive plants. In fact, she re cently taught a class on stilt grass for the Invasive Species club and was delighted by par ticipant feedback.

One woman who attended the session later told Regan it made a real impact on her.

“She was like, ‘I went for a run, and now I see stiltgrass ev erywhere!’” Regan said, “And someone else was like, ‘It’s a si lent invasion!’ Her eye has now been trained.”

Regan is hopeful about the ripple effect of educating peo ple on invasive species. “If we train people, and we’re like, ‘Listen, if you see it, pull it.’

Then you start to care about your own yard.” said Regan.

“Then maybe you talk to your neighbor, ‘Hey, you wanna pull

that stiltgrass you got going?’”

She emphasized how anyone can develop knowledge of their local flora. “It’s learnable,” she said. “Why aren’t we teaching this in local schools?”

shrub and asked if anyone knew what it was. A small boy in bright red sweatpants shout ed, “It’s a fire bush! It’s an inva sive species!” Hiltner grinned. “Well, yes, it’s actually called burning bush.”

Steve Hiltner was scheduled to lead a group hike and invasive species tour through the forest starting at 11am. “Sort of aspi rational timing!” a local man warned me. Finally, around 12:30, Hiltner was ready.

“Okay,” he called, “we’re go ing to trek for about an hour!”

A woman laughed knowing ly. “That’s what you say—it’s al ways two,” she quipped.

Nineteen of us traced the trails behind Hiltner, including three little kids, two big dogs, and a black and white puppy named Plato.

Hiltner pointed to a red

He led us through a stretch of seven acres that had been covered in invasive wisteria. Before eradication efforts, Hiltner said, the wisteria made this area impassible. “This whole forest would eventually have fallen down. You have to go after it like it’s a monster,” he said.

Hiltner believes in precision herbicide application, and he puts the poison directly on the stumps of invasive vines, he told us. “It’s like medicine in the body. You want the medi cine to just do one thing,” he explained.

Near the woodland stream, Hiltner held up a large branch

with red berries. It’s an inva sive species, he said, that hasn’t been identified. “Nobody knows what this is!” he pro claimed. “There’s no name for it! It may be something from Taiwan, but this is a new inva sive and we don’t even know what it is.”

“It’s the Steve-berry!” a wom an called.

Hiltner grimaced, then laughed. “Oh, I don’t think I want to be known for that!”

Like much that goes on at Herrontown Woods, the tour was pretty free-wheeling. “I’m running into too many inter esting things,” Hiltner sighed, with delighted exasperation. “We’re not getting anywhere!”

At one point, he zipped open his backpack to find his favorite “buckthorn blaster” herbicide spray but pulled out two small green fruits. “Ah, pawpaws,” he said. “These are from my

garden.”

We crossed the stream, and a black lab splashed in the water. The owner called to us, “This is her favorite spot in the woods!”

“There are magnetic rocks in there,” Hiltner said, pointing to the stream, “it’s because they contain magnetite.”

“Magnetite is an iron-oxide,” a man commented, to no one in particular.

In a clearing, we came upon a red shed that housed a ping pong table—Inge Regan’s inno vation. Two boys were playing, their laughs reverberating off the trees.

At the end of the hike, Hiltner led us to a rocky outcrop. “See that pretty orange tree over there?” he asked, pointing to a tall trunk sheathed in bright leaves. “That’s all poison ivy.”

His audience ooooh’ed.

“And that tree is dead,” Hiltner concluded, wistfully.

After lingering in the Barden and meeting the Friends (and friends of Friends) of Herrontown Woods on that sparkling autumn day, one thing became clear. The com munity’s experience of this nature preserve is about much more than botany education.

Alistair Binnie, a Princeton local who recently retired, said he hoped to devote more time to volunteering at Herrontown.

“The thing about gardening on your own is that there’s no sense of community about it,” said Binnie, “I think this is an interesting example of a com munity group. Steve has really done a great thing in building this, and letting it evolve in a community-facing kind of way.”

Binnie experiences Herrontown as a unique ref uge of wilderness in a curated town. “Princeton is a pretty but toned-down, highly-organized, almost suffocatingly-structured kind of place,” he said, “so, to have something that’s trying NOT to be that—it’s kind of nice. Nothing like it existed be fore in Princeton, that had the same kind of edginess, the wild ness, to it.”

As Binnie spoke, a toddler wobbled past us, holding a large stick over his head. He

wore a jacket with fabric spikes running up the hood, like a stegosaurus. We watched this minuscule person hurl the stick with all his might at an unas suming shrub.

“He’s a wild thing!” Binnie exclaimed, cracking up. “Small children playing with sticks, what’s not to like?”

Victoria Floor, a writer who has lived in Princeton since 2015, previously served on the Friends of Herrontown Woods board. She sees the preserve as a space that nurtures a sense of play in adults and children alike.

“These are workaholic adults who take themselves very seriously, with very profound careers, looking at things with microscopic vision and preci sion,” said Floor, gesturing to the locals chatting among the wildflowers. “Out here, it’s a place to relax. I think the kids lead the way and show you how easy it is. They’re just curious by nature, and there’s nothing like turning over a log or a stone and looking at the wriggling things underneath. It’s so simple—it’s so intuitive.”

Floor finds philosophical meaning in the complex eco systems of the forest and gar den, particularly in the face of climate change. “Everybody de spairs about the environment,”

she said. “But it’s not a despair ing, tragic feeling around here. In fact, it’s very hopeful.”

“I approach this spiritually,” Floor went on. “It’s so deep and so important, that understand ing it gives me more goose bumps than anything else. When I read about something like soil, I mean, humble soil is so fascinating… And then you read something that says thirty percent of the earth’s soil is be ing depleted every year, and it’s like, AAH!”

Floor believes that this sense of vital, even existential mean ing keeps people connected to wild places like Herrontown.

“It’s that sense of awe on the one hand, and terror on the other,” said Floor, “which is basically what religion al ways offered people, that same sense of awe and terror. And salvation comes best through community.”

Herrontown Woods is root ed in the Princeton community, and its eclectic projects develop from the unique contributions of each community member.

“We’re going to see what comes,” Inge Regan told me. “And we’ll make something with it.”

Before eradication efforts, Juju Lane said, the Nassau Weekly made this area impassible.

translation in wood

it, and create the Jewish historian? How are the two different in practice? The Jewish historian can only fulfill her role in relation to others. If the Jewish histo rian were given a time ma chine, she could only fulfill her mission when she re turned to tell others of her findings. Becker’s historian can fulfill her mission on her own; the truth need not be a group project. Without an audience, Becker’s his torian becomes estranged from history’s meaning and value. Like Walter Benjamin once wrote of an actor who transitions from theater performance to film acting, “his whole self, his heart and soul, is beyond his reach.” The actor feels “estrangement felt before one’s own image in the mir ror. But now the reflected image has become separa ble, transportable.” When history is practiced outside of a community, its impact

is not felt and, therefore, not considered. Only its truth value matters. Contrast that with Yerushalmi’s descrip tion of a Jewish historian as “More than a scholar and writer of history, he feels himself, with some justifi cation, an actor in history.” When individuals recall the story of Exodus in a familial context and as historians, they are entangled with the past. The Jewish historian’s calling is to remember the past before her audience and provoke a reaction. The Jewish demand of histori ans to collectively put histo ry in the present is a mecha nism for remembrance, not recall.

With clear dis tinctions between the two modes of history, we may ask if they might be com patible. With slight adjust ments to the story, we can conceive of Mr. Everyman as a Jewish historian. Say Mr. Everyman continued to share his story with others. Instead of focusing on the veracity of his initial debt claims and his process of

discovery, he highlighted the power of misremem bering as a lesson for life. Mr. Everyman, then, goes further than the Becker historian and becomes a Jewish historian. Though the two historians are not inherently incompatible, they do have an inevitable divergence. Mr. Everyman would not betray the Jewish way of history if he were to only share his misremem brance and neglect to note that he, ultimately, did pay Mr. Brown a payment. The balance of Mr. Everyman’s account would be different and the fate of payment would change, but this would not have any immedi ate or clear relevance to the lessons of misremember ing. Becker’s “superficial and irrelevant accretions” are the Jewish historian’s primary data points. As his tories get retold, it will sure ly be that certain details are left out that come at the cost of accuracy.

The challenge of truthfulness to Jewish history was dealt with by

Professor Marianne Hirsch in her riveting book, The Generation of Postmemory. Her contribution is worth quoting in full. “The ‘post’ in ‘postmemory’ signals more than a temporal delay and more than a location in an aftermath. It is not a concession simply to linear temporality or sequential logic. Think of the many dif ferent ‘posts’ that continue to dominate our intellectual landscape… ‘Postcolonial’ does not mean the end of the colonial but its trou bling continuity, though, in contrast, ‘postfeminist’ has been used to mark a sequel to feminism,” she wrote. Though a Jewish history might not recall a memory with exactness, it does remember that precise memory in a different form.

Raul Hilberg, for example, began researching for his book The Destruction of the

European Jew as a Becker historian. However, accord ing to Hirsch, after identify ing factual errors in the oral histories and testimonies of interviewees, he “deferred to storytelling and to poetry as skills historians need to learn if they are to be able to tell the difficult history of the destruction of the Jews of Europe… Hilberg is recalling a dichotomy be tween history and memory (for him, embodied by po etry and narrative) that has had a shaping effect on the field.”. What Hirsch calls history and memory, I dis tinguish as Becker’s histo rian and a Jewish historian, respectively. The Jewish his torian chiefly desires to cap ture the lessons of the past.

The histories imagined by Becker and the Jewish tradition rhyme. Becker can acknowledge the im perfection of history, but

he cannot come to accept it. History is about the pro cess by which we determine what has been said and done. Memories live in the past. The Jewish tradition, with which I affiliate, pro vides what I believe to be a more comprehensive vi sion of history. History is faulty in its veracity but so is mankind in its morality. By remembering history with others, we can come to build communities and improve ourselves. Becker’s historian, the academic his torian, thinks about histo ry. The Jewish historian, a product of a moralizing tra dition, experiences history. I opt for the latter.

All of the Nassau Weekly’s problems would be solved with a time machine. The same is not true for Adam Hoffman.

comic