THE MARK

ISSUE NO. 1 | WINTER 2020

POLICY

e Mark, a feature magazine published by the students in Menlo-Atherton’s journalism class, is an open forum for student expression and the discussion of issues of concern to its readership. e Mark is distributed to its readers and the students at no cost. e sta welcomes letters to the editor, but reserves the right to edit all submissions for length, grammar, potential libel, invasion of privacy, and obscenity.

Submissions do not necessarily re ect the opinions of all M-A students or the sta of the Mark. Send all submissions to submittothemark@gmail.com

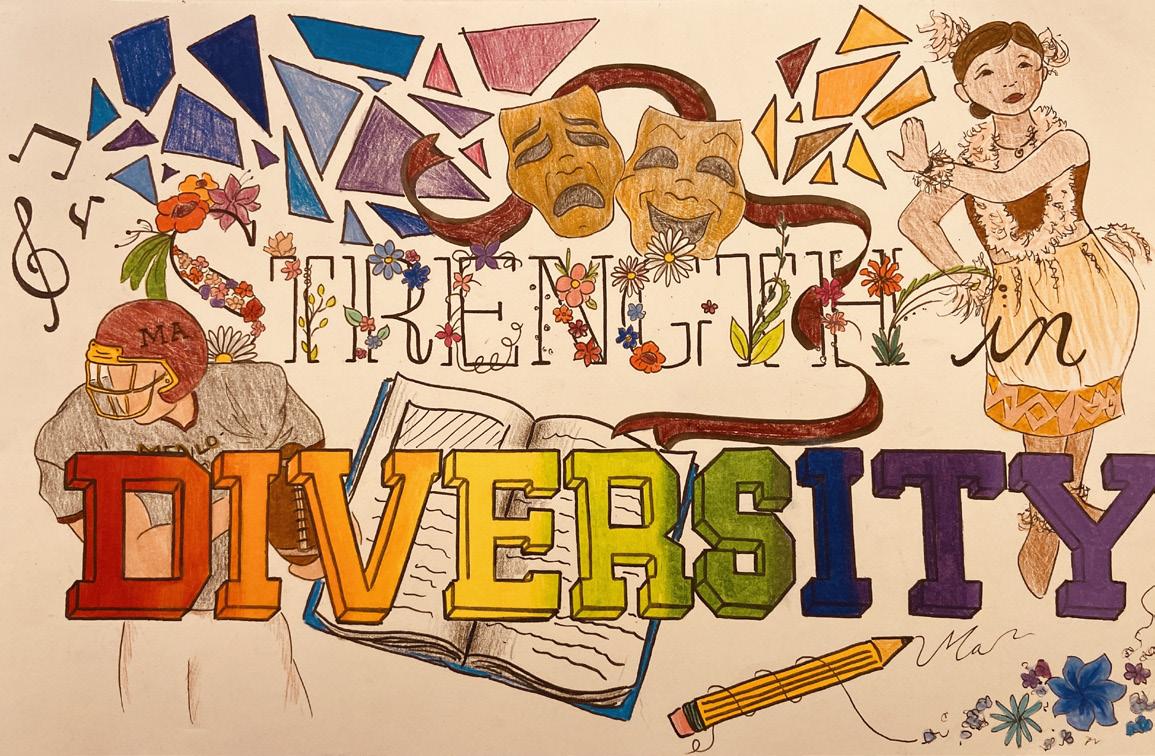

ABOUT THE COVER

is edition of the Mark may look di erent than previous issues. We wanted to create a much longer edition, focusing on student voices in representation. is issue is divided into three sections: past, present, and future. We hope that this magazine sparks meaningful discussion about who we are and who we were will shape who we become.

STAFF

Sarah Marks

Ellie Shepard

Nate Viotti

Nat Gerhard

Toni Shindler-Ruberg

Brianna Aguayo Villalon

Marlene Arroyo Rosas

Brynn Baker

Nate Baxter

Triana Devaux

Lucy Gundel

Alana Hartsell

Chloe Hsy

Izzy Leake

Callista Mille

Antonia Mortensen

Sathvik Nori

Joanna Parks

Zoe Schinko

Isabelle Stid

Karina Takayama

Violet Taylor

Cole Trigg

Maddie Weeks

Katherine Welander

Jane White

Amelia Wu

John McBlair

Editor-in-Chief

Editor-in-Chief

Editor-in-Chief

Managing Editor

Managing Editor Journalism Advisor

3

M-A Back in the Day

Our Teachers as Seniors

Menlo-Atherton’s Race Riots

e Architectural History of M-A

Student Protests rough Time

M-A’s Cultural Club Recipes

Faces of M-A

Bears at Work

Opinion: Serving or Spending?

Gender Neutral Bathrooms: Students Express Cautious Optimism

A Cultural Club for Everyone

Editorial: What Student Representation Is and Isn’t

Opinion: Toxic Masculinity

Broken Promise Land: Students Share Perspectives on Israel

Student Submissions

Verses Issue I: Ghost

Who is Our Rival?

Opinion: End the Stigma. Period.

Weekend Wayfarer

Test-Optional Colleges

You Can Lie on Your College Application... and Get Away With It.

Opinion: College or Culture?

Student Submissions

TAPP: a Program for Teen Parents

More an Traditional College: Students Discuss Post-High School Opportunities

e Future of Public Art in Menlo Park

Faces of M-A

Winter Comics

I

past

illustrated by Karina Takayama

M-A Back in the Day

M-A has changed a lot since it rst opened its doors in 1951. Alumni and teacher interviews detail what M-A was like back in the day.

Mark Baker

Class of 1987, Baker planned the 20 year anniversary for the class of 1987. He has a daughter at M-A as well as a son who recently graduated. He also currently coaches the M-A girls golf team.

“One of the memories that has always been really special about M-A is the spirit. ere were really cool school spirit weeks where each class made parade oats and they cruised them around the track. I was also really lucky to be at M-A with Coach Parks. Every year for his birthday, he would run a mile for each year old he was, and when I was there he was like 60 years old. He would start at 2 a.m. and a lot of people would come out to do it with him. He would use this opportunity to raise money for charity. Towards the end of senior year, there were Powderpu games, where the cheerleaders would play football and they would wear all the football gear. Before the Stanford games, there were BBQ tailgates put on by students with a lot of community spirit. We didn’t have night games because there were no lights; it adds such a cool dynamic to have games with parents and students to come out to play.

“Each class made parade oats and they cruised them around the track.”

Rick Longyear was one of my favorite teachers. He taught biology and was my swim coach. He was passionate about teaching and encouraging students to do the best that we could do whether it be in the pool or in the classroom. Ms. Wimberly was my PE teacher freshman year and she was terri c. Just like today, she was all re, and she doesn’t seem to have changed. My AP Euro teacher, Mr. Baer, was amazing and would take a group of kids to Europe. He was really passionate about sharing his experiences and

life in general with his students. Teachers were passionate about sharing interesting things and expanding the knowledge that they were able to give to kids.

In the early 1980s, when I was at M-A, M-A had gone through some radical changes. In the 70s, and in the early 80s, there were racial riots. At the time there was a much larger African-American population because EPA had a larger African-American population than today. Coach Parks worked hard to unite the African-American and white students at a time when there was a lot of division. I remember an article in the Almanac with Coach Parks walking arm in arm with all the kids, black and white, on the football team as a show of solidarity and unity. It showed that we didn’t really care what goes on outside of school. M-A has always been a really diverse school, we have families from di erent socioeconomic statuses. I think we’ve done a good job understanding people from di erent economic and social backgrounds. Challenge day has taken that a step further. It does a great job breaking down the barriers of the di erences of the groups. I am really proud to say that Menlo-Atherton was a leader as far as high schools go, for a movement towards better equality and less of a divide.

M-A hasn’t changed a lot and I have a lot of respect for the current administration and the work that they do.”

Carlos Aguilar

Class of 1973 and tennis coach at M-A for about 20 years.

“ e overall atmosphere was ne on campus with a bunch of kids from di erent middle schools thrown together for the rst time. e biggest issue at the time was the racial tension. ere was a riot the year before I arrived and one to two more later on and certain bathrooms one didn’t go into for fear of getting beat up. ere were also random attacks in what’s now Pride Hall.

M-A, from when I went there to when I started coaching the boys tennis team in 2001, was the same. A typical public high

school with every type of kid from the area: great students to juvenile delinquents, and everything in between. e biggest di erence between then and now is that now a majority of kids are very serious about their studies. In 2001, the kids on the tennis team would use any excuse to get out of class early. In the last 15 years, kids on my team would do anything not to miss class.

“Certain bathrooms one didn’t go into for fear of getting beat up.”

I just nished 19.5 years of coaching the tennis teams. It was one of the greatest experiences of my life. I met and worked with some amazing young men and women. We had our share of success with the boys winning 15 straight league titles and the girls winning the last six league titles. e kids are what I’ll miss the most.

When I went to M-A, our football and water polo teams were very good and my friends and I enjoyed going to their games.”

Liane Strub

Strub has been at M-A since 1995 and has taught every level of English except for English IV.

“ e one thing I think kind of makes me sad is that I feel like there was a more creative element at M-A back in the day. For example, we had an improv group, which doesn’t exist anymore. We had people who were a lot more artistically inclined, and now everybody’s math and science. So that’s kind of sad because there aren’t as many free spirits.

“Seniors camped out on the green the night before graduation breakfast.”

ere have been lots of really good senior pranks over the years that I really liked. One of my students started the idea where seniors camped out on the Green the night before graduation breakfast. It was so fun. All these little tents across the green. ey had to let the administration know, because they had to go to the janitorial sta and make sure that the sprinklers were turned o . ere was another time they covered the green with pink amingos. A senior prank that is not destructive, but is amusing, is a very cool thing and there hasn’t been one for a long time.

We had a student start something called the Two Pie Club. He was in Safeway late at night and he’s like, ‘I’m so hungry I could eat two pies’ and then he thought, ‘could anyone ever eat two pies?’ We started this contest on Friday afternoons or Friday lunchtime. He would get four pies from Safeway, and you’d have contestants. It got very messy. A couple of times it was like they eat the two pies and then they threw up in the garbage can right after.”

written

by Triana Devaux and Violet Taylor designed by Izzy Leake

Photos from 1966, 1968, 1980, and 1987 M-A yearbooks

G. Back in 1968, a student dresses up with a ri e for the Sadie Hawkins Hoe Down. A C D F E G B

A. Two water polo players from 1980.

B. ese friends smile for the camera in 1987.

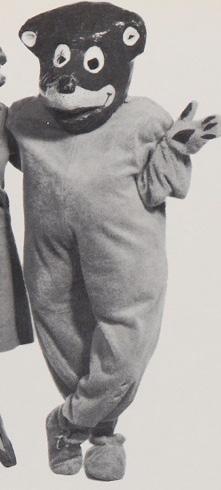

C. e M-A Bear had a di erent look in 1966.

D. A track and eld athelete prepares to throw the shot put in 1968.

E. A Pom Pom Girl strikes a pose in 1966.

F. A group of friends walks down the hallway in 1980.

OUR TEACHERS

1. Mr. Giambruno 2. Mrs. Shepard 3. Mr. Simon 4. Mr. Duarte 5. Mr. Tillson 6. Ms. Keigher 7. Mr. Nelson 8. Mr. Harris 9. Mr. Shen

AS SENIORS

designed by Nate Baxter

Menlo-Atherton’s

RACE RIOTS

Physical education teacher Pamela Wimberly began her teaching career here 52 years ago.

“I was outside with my rst class, on my rst day at Menlo-Atherton, and all of a sudden I saw a garbage can go through the window of what is now the E-wing, the very last classroom. I didn’t know what was going on. It was frightening. I can’t remember how many windows were busted in on campus, but there were a lot of them, rows and rows. e next thing we knew, people were spilling out of the classrooms. Some kids were getting hit and hurt. en, the National Guard had been called in. ere were helicopters above us. And boy, that was like re and fury; it was crazy. But that rst day of school was, I think, very tragic and very surprising to me.”

The racial tensions that led to the series of riots at M-A in the late sixties were a long time brewing. In the decades prior, district lines were redrawn multiple times, pushing black students in and out of Ravenswood, the East Palo Alto (EPA) public high school established in 1958. In the lead

up to the 1966-67 school year, redistricting again divied up Ravenswood students and sent them to various Sequoia Union High School District schools.

The goal of redistricting was to amend funding at Ravenswood. e initial hope was that by bussing minority students out of Ravenswood, schools would, in turn, bus students from their respective, predominantly white, public schools. e problem was that white students never ended up at Ravenswood in any signi cant number. Parents of white children fought to keep their kids in the wealthier public schools, and won. As a result, many of the students at Ravenswood were dispersed to other District schools but not the other way around.

Many EPA parents had initially advocated for this policy, arguing that the problem with keeping kids at Ravenswood was that its funding was inadequate and had an education quality to match.

Russel Rickford documents this in his book, We are an African People: Independent Education, Black Power, and the Radical

Imagination . He invokes the account of Gertrude Wilks, who moved to EPA in 1952 and sent her eldest son, Otis, to Ravenswood. “It soon grew evident that her eldest son was falling by the wayside. Otis was not bringing home homework or showing academic progress. When Wilks shared her concerns with the largely white sta of local schools, she was complimented on her son’s pleasant disposition and cautioned against tutoring him at home; doing so, she was told, would only undermine the e orts of professionals. Conscious of her own rudimentary schooling and ‘crude’ speech and loath to be seen as a meddling, overbearing mother, especially given contemporary concerns about domineering African-American ‘matriarchs’, Wilks relented. ‘You didn’t feel you was qualified,’ she later said, explaining her reluctance to challenge white teachers. en one day during his junior or senior year, Otis made an alarming confession: though he was on track to graduate, he was woefully unprepared for college. Semiliterate at best, he struggled even to complete applications

from entry-level jobs. ‘I am lost,’ he told his mother. ‘I don’t know nothing.’”

Rickford goes on to lament the Ravenswood district as a whole. “East Palo Alto schools had deteriorated signi cantly during the 1950s and ‘60s. As white residents ed, unimpeded by racial discrimination in housing and labor markets, they eased the pressure on educators—most of whom lived outside the community—to uphold academic standards. East Palo Alto’s Ravenswood High, a predominantly black school by the late 1960s, shifted to a vocational emphasis as its course o erings and overall rigor declined. The Ravenswood district itself became a symbol of failure.”

Wilks, outraged by her son’s education, went on to form the Mothers for Equal Education with a small number of community leaders. In 1965, they petitioned for the closure of Ravenswood, on the premise that EPA students would be sent to majority-white schools and attain a better education. While Ravenswood High School wouldn’t o cially close until 1976, the mothers’ demonstrations led partially to the redistricting of black students that resulted in, as put by Louis Knowles of the Stanford Daily, their being “sent against their will” and “su ering for over a year in the oppressive atmosphere of white-dominated halls and classrooms.”

According to some teachers, this is when the trouble started. e rising black population at M-A was increasingly ostracized from their white peers. “Forced to suddenly confront the alien world of rich whites,” Knowles wrote, “they had not become an integral part of the student body, but had remained outsiders to the vast majority of white classmates.”

By the summer of 1967, M-A’s black population had risen to around 350 of 2,050, almost 20% of the student body. In spite of these dimensions, 1966-67 school year didn’t have a single black educator.

Ms. Wimberly, who came to M-A shortly after, remembered the environment. “At that time, you were told what kind of curriculum you were going to take. A lot of minority kids felt like they weren’t being directed towards academics, and they wanted to be able to choose. People overlooked giving everyone a fair chance to do what they wanted to do in the classroom, what courses they needed and wanted to take. M-A didn’t have the o erings they [students] wanted. Students felt that they were not being fairly treated, and so they wanted change.”

e Palo Alto Times documented the following racial tensions through unnamed students.

“I have walked up to white students and smiled and said hello. And they turned around and walked away.”

“ ey don’t like us or the way we talk or our music or anything about us.”

“White students act as if they own the place and are just letting us use it as a favor.”

“ ey [African American students] move in and take over somethinglike a rest room- and it is not safe for a white person to go in there.”

“Some of the teachers don’t like Negro students, but it is not their fault. It is because of the way they were raised.”

“Some of the white students don’t treat us as if we are people. ey look at us as if we were animals.”

e tipping point was a new bussing policy, e ectively excluding the vast majority of black students living on the other side of Bayshore Highway. After the failure of bond proposals, the District Board of Trustees voted to provide bus transportation only to those students living more than two miles from campus. e Board claimed the new policy would save the district a sum of $65,000 annually. Many white students had their own transport, with multiple pages of the yearbook devoted to an annual car show. Lou Ann Bradford, head of the Menlo Park chapter of the African-American Committee for Education, expressed a shared concern. “We need buses for our children. With the rainy season coming on, they’ll get sick. e people up on the hill don’t need them. ey have cars. e poor blacks and poor whites are all su ering.”

e Friday before the rst day of

school, September 15th, 1967, the M-A Black Student Union organized around the bus lot, documented by the Stanford Daily. at afternoon, they successfully stopped one bus loaded with white students leaving from orientation on the grounds by linking arms and surrounding it. e faculty arranged car transportation for the stranded students, and the black students returned to EPA, but not before a police blockade had treated them all as criminal suspects by stopping and searching them “without cause.” Two students, 14 and 16, were arrested. Principal Douglas Murray, on his rst year on the job, asked police to leave, and requested the assistance of parents, a minister, and EPA’s volunteer “Cool-It Squads” to help maintain order.

On Monday morning, September 18th, at 8 a.m., school administrators met with EPA citizens at the school to discuss the lack of transportation. Several black students were invited to attend the conference but then were not allowed to speak. e administration at the meeting denied that the students were ever invited and the students, not allowed to participate, stormed out of the meeting at 9 a.m. to hold what Atherton Police Chief Leroy Hubbard called a black power rally in the football eld bleachers.

Directly after the rally, officials reported the rst set of altercations in the halls during 10:15 a.m. brunch, reportedly sparked by both black and white groups. About 20 black students ran through the hallways, attacking and ghting with white students, according to Chief Hubbard. e police were hastily called in by the administration. eir presence added to the tension, but when the police left before lunch at 1 p.m., ghting broke out again.

e Redwood City Tribune reported that as classes were to resume following the lunch hour, there was a confrontation in the parking lot in which a white student harassed a group of black students. It was broken up by a teacher, but many black students did not return to class. Around 150 walked through the halls in groups, and began to damage the campus.

“ ey came over the loudspeaker and told us to lock ourselves in. We’d never had a lockdown drill. We didn’t even know what that was. But we did have a speaker in the locker rooms, and so they told us we were to hold in silence,” said Wimberly.

e National Guard was called in in full riot gear, and martial law was declared on campus. Classes were dissolved and the Guard evacuated students, escorting them to their

respective homes. Two students, a 15-year-old boy and 17-year-old girl, were arrested. Six students would ultimately be expelled.

e school nurse recorded treating 50 students before she stopped taking names.

Four were for head injuries. ere were 23 more students who were cut on the head and 20 cut or bruised in other places. One boy was taken to the nursing o ce after several of his teeth were kicked in by a crowd of black students. However, Chief Hubbard said that only 15 were reported as injured. ere were no weapons used, he said, “nothing but sts.”

Wimberly said, “At the time, there were the afros that were going on, so they had what were called ‘cape cones.’ So the combs at that time, they were spiked at the end, and so some people were hit in the head with those and hurt.”

One of the students arrested at M-A Monday, 17-year-old Karen Owens, was charged with “helping four other Negro girls beat a 15-year-old Caucasion boy. ey are said to have stomped his prone body with high heels.” She was held at Hillcrest

Juvenile Hall for two weeks before San Mateo County Juvenile Court Judge Melvin Cohn announced “some consideration” of her release. He publicly stated that she was being held until things “cooled o .” James Haugabook, vice president of the South San Mateo County branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), said Cohn was using the girl as a “political hostage” in refusing to release her until conditions were quiet at M-A.

Dave Weber, a white M-A student, was hit on the head with one of the psychedelically painted 50 gallon barrels that served as trash containers.

According to the Tribune, he had cuts on his head, but none of the bitterness you’d expect. “I just happened to be in the way. I can understand why it happened. e Negro students have been on the recieving end so long it had to happen. I’m just surprised it didn’t come sooner.”

Weber’s attitude towards the riots wasn’t re ected across the campus. e word on campus was that some football players wanted to “get” black students after Monday’s violence. According to the M-A Black Student Union,

“50 white boys came over the Willow Road overpass Wednesday morning, armed with baseball bats and bottles and looking for trouble.”

District Superintendent, George P. Cha ey, called a public meeting with the Board of Trustees that Wednesday night. e intended purpose was to rule on the district bussing policy in light of the riots. A proposal to provide bus transportation to students more than 1.5 miles from campus was introduced, which would e ectively permit busing for the East-ofBayshore area. The meeting was scheduled in the Sequoia High School

Auditorium, which had a capacity of 900 people. e eventual audience amassed 1,200, and was largely diverse.

Doug Allen, Black Student Union leader, was recorded by the Tribune as announcing, “ e trouble at M-A started when the Black people of East Menlo Park were singled out to not get buses. The Black Student Union has called for all black students to boycott Menlo-Atherton High until: school administrators have guts enough to handle their problems without the police; the girl arrested for assault during the riot, who is held as a hostage, is released, invasions of our community by whites are stopped [in reference to white students cruising East Menlo Park with baseball bats earlier that day]; and the bus service is restored.” e M-A BSU announced a total of ten demands for ending the boycott, including the abolishment of martial law at M-A, more African American teachers, and hot lunches, which were also cut that year for economic reasons.

e student senate and grievance board of M-A endorsed three of the demands of the BSU and said they would favor a boycott if the Sequoia trustees refused to change the bus boundaries.

Josh Cooney, a white, San Mateo County resident, who was out of jail on bail after being arrested for trespassing at M-A on Monday, denounced Allen, saying that “that speaker is un-American.”

Gertrude Wilks of EPA Mothers for Equal Education stood with the BSU. “We wholeheartedly support all the demands of the Black Student Union. I want to make it very clear we are afraid no longer. I want to be free from the top of my head to the tip of my toes. You’ve de-educated our kids for nine years and now you take away their buses. We will stand together in East Menlo Park and East Palo Alto.” Mothers for Equal Education went on to announce plans for a rally in sympathy with black students at M-A and a demonstration at the San Mateo County Courthouse Monday morning.

Sammy Sawyer, an EPA resident, echoed Wilks’ concerns. “We came here to speak for the mothers whose children have to walk to school in the rain and snow.”

P.E. teacher Pamela Wimberly on her rst day of teaching in the 1960s.

Poster circulated by M-A students in 1967.

“We don’t want no bloodshed in Menlo Park. e only thing we want is an education for Black girls and boys.”

Another EPA resident, Josephine Becks, said that

“We so-called responsible people have no choice but to support the demands of the BSU. You white people have the police and the power to exterminate us, just remember these young people will take a few of you with them.”

Student Frank Merril was against the policy. “Maybe the Negroes need buses, but I don’t see how they can expect to get them when they run down the hall beating whites. ere was a wild mob of Negroes beating whites. I don’t see how the superintendent and principal could watch people getting beaten up and not have called police earlier.”

Several Atherton parents expressed similar sentiments.

“Our children are taught not to ght. Our girls in particular cannot ght. As a consequence you can have 300 Negroes running over 1700 whites.”

“My daughter hasn’t been able to use the bathrooms at M-A for two years because kids get beaten up there.”

“I’m not from the South. I’m a native Californian. I don’t owe them anything. I’ve never done anything to them. Why should we have to subject our children to this kind of thing? We shouldn’t have to teach them to defend themselves in this manner.”

“ is terror has got to be stopped. It didn’t start with the buses, and it won’t end with them.”

Board of Trustees Chairman Dean Watkins announced support of a common concern about reinstating the bussing policy following Monday’s violence. “I have a feeling that even if there had been no change in the bussing policy, the problem at M-A would have arisen. My recommendation is that since I’m not sure the transportation policy is at the heart of the problem, the two-mile limit should remain in e ect.”

Municipal Judge Roy W. Seagraves of Redwood City said that “the tone and timing of these [BSU] demands, and the conditions immediately preceding their presentation render it inappropriate that they be acceded to at this time.”

White students begin to use the buses again a er riots.

M-A’s interracial club early 1970’s.

In direct opposition to his statement was Paul Clarkson, an M-A teacher, who said,

“When the board receives pressure from the white community, you call it the American politics at work. When it comes from the Black community, you call it coercion. If the demands had been submitted to you peacefully, the board would not have granted them.”

Ultimately, the Board of Trustees voted in favor of the new bussing policy. Students would get their buses.

Additional legislation resulted from faculty meetings all day Tuesday and Wednesday, in which teachers and the administration voted against the proposal that police not carry guns on campus. Faculty also ruled the elimination of hall passes and of brunch altogether. e Redwood City Tribune reported that faculty members released the contents of a resolution Wednesday “in which they went on record as recognizing that ‘many student concerns are legitimate’” and “a substantial portion of the faculty was in favor of a stronger resolution, endorsing the majority of the BSU’s demands.”

“We had very exuberant teachers, teachers who were very interested in making sure the students got what they needed, and who listened to students. e community [of the administration and teachers] worked and worked with both communities to try and make things better, to try and improve things within the school,” said Wimberly.

M-A reopened Thursday with sixty uniformed San Mateo County sheri ’s deputies, riot helmeted with guns on their hips and marching onto campus 15 minutes before the start of class. Students who arrived late were escorted to class, and not allowed to speak to any reporters. About half of the 2,038 students were present, but only 150 of the school’s 350 black students showed. 50 black students met at a local park for a boycott meeting, where speeches were held. e Tribune reported that “white students are also staying away, some through fear of violence and some in sympathy of Negro demands. One white student did not attend school ursday because he thought ‘it was important that white students support the Negro boycott.’”

James Haugabook, vice president of the South San Mateo County branch of the

NAACP, said that “conditions at the school would remain incendiary as long as martial law is in e ect.”

District Superintendent George P. Cha ey said the police guard will remain “as long as it is considered necessary for the safety of the students.” One M-A teacher remarked on the police presence, “It is time somebody did something to protect the innocent kids here who get hurt. Some of the things that happened on Monday should not have been tolerated. ere was nothing that teachers could do.” An attending student said, “Hell, it was quiet today, wait until the cops leave and the Negroes come back.”

Wimberly said,“We had an uprising again, maybe a year or so later. But I feel very strongly that the community at MenloAtherton was trying to, not make peace, but make things better. at year, we had nine African American teachers teaching at M-A. To me, that was the most African American teachers that have been here, ever. I think that we have to believe that the majority of people in this country can change, nonviolently. I think that we have to persevere, and get people to believe in themselves, to believe in others.

e model that Martin Luther King had, he was not a violent man, he was not a violent leader. e opposition, though, turned the hoses and the dogs on people. But I don’t think that violence solves things. And he said he had a dream that we would all be free, and that is true, because I lived through the time where I couldn’t go into a restaurant and eat, when I got on a bus and was bullied and called all kinds of names. But

we persevered, we overcame, and freedom came about.

We’ve come a long ways. I see more people mingling with others. e diversity is really sticking out now at M-A, and people beginning to interact with others who are from di erent race groups or ethnicities. People are reaching out to others, and understanding cultural di erences. I think that’s important.

We have a long ways to go, a long ways. e problem a lot of times is that when students come in, especially students from the Ravenswood or Redwood City school district, they might not be totally prepared to go into those classes. I do think that our students of color come in handicapped, a lot of students.

I know my parents, though, when they grew up, they couldn’t go anywhere. My dad was nearly killed in Georgia, because they thought he had brought a white lady with him. So, I see change has come about, but it’s taken time. Lots of time. And, as each generation leaves this earth, the next generation doesn’t remember those things that are behind us, that got us to the point where we were free or where we made change, and all the hardships aren’t known and aren’t remembered.

But what I remember is the locker room. It was scary. We quieted down the girls, everybody was quiet, and we could hear nothing except the helicopters that were ying over, that was it. But everything else was quiet.”

written by Alana Hartsell designed by Ellie Shepard

As the second oldest school in the Sequoia Union High School District (SUHSD), M-A has a long architectural history that spans all the way back to 1951 when the school was founded. rough 68 years of the school’s existence, M-A has gone through many renovations that have shaped it into the school it is today.

e original project was run by general contractor, Peter Sorenson, which included the A, B, C, D, E, S, and J wings, and aside from the S and J wings, all ve of the other wings still stand as original buildings today with some minor renovations through the years. e overall cost of the school was $1.8 million. According to SUHSD Chief Facilities O cer, Matthew Zito, “people were horri ed that it cost that much at the time, compared to the partial renovation of the locker rooms last year, which cost 4 million dollars.”

Aside from the addition of Ayer’s Gym, locker rooms, and a pool in 1955 and some minor renovations throughout the years, M-A went about 40 years without any further renovations to the school. e school was in poor condition after years of little maintenance. e reason for this insu cient maintenance was the fact that SUHSD had four huge schools totaling 5,800 students, and the money that M-A needed simply went to other schools in the district. But ever since 1996, M-A has undergone multiple renovations that transformed M-A’s poor condition to its current campus.

e biggest project has been the G wing renovation, which was completed in 2017. e design includes 21 new classrooms, a new learning center, new food service, new student and sta bathrooms on both oors, a new covered lunch area, and a new courtyard. e building is highlighted by its suspended

bridge, which is held up by a steel frame skeleton, and allows students to walk through the G wing instead of walking around it. According to Zito, “we just took out the bottom classrooms and you walk through it. One of the things that was expensive was actually the suspended bridge because the state over-engineers everything to make sure no one gets hurt in an earthquake, so we have these enormous pillars to suspend that bridge and make sure the G wing is very strong.” All in all, the project cost around $24,670,000, and is part of M-A’s expansion plan to support 2600 students by the year 2020. Instead of creating a double schedule where students start and end at di erent times, the decision was made to add onto the campus in an e ort to be able to support more students.

Another massive re-design of M-A’s campus also came in 2017, the S wing renovation. Before the project, the S wing

was a very small wing that looked a lot like the current M wing. Now it has six new lab rooms, a new food service building, a new courtyard, and new bathrooms. All together, the S wing renovation came in around $17,600,000. e new buildings are very helpful for teachers and students. According to Maria Caryotakis, a chemistry teacher at M-A, “it’s great we have more space because we have had to be on top of each other in classrooms, and the classrooms are more modern and clean.”

Although the S and G wings were the biggest projects, M-A has had plenty of other substantial renovations over the years to keep the campus modern. In 2001, M-A installed a massive pool and turf eld, both of which are still routinely used. ree years later, the new gym was built, and ve years after that, the Performing Arts Center was built, costing around $29 million. Last year,

new locker rooms were installed with the addition of a turf soccer eld instead of the previous grass eld. Finally, also constructed to support the student expansion plan for M-A, there were ve classrooms added to the F wing in 2014.

After a busy couple years of renovation, M-A does not have any immediate, substantial projects in the coming years. However, the room, C-2, is going to be converted from a physics room into a chemistry room this upcoming summer. Steve Bowers and Usha Narayan, of Spencer Associates Architecture, will be running the project. Bowers and Narayan were also the architects that constructed the F wing renovation, and according to Narayan, they were happy to come back to run the C-2 renovation because “both the MAHS and SUHSD sta have been phenomenally cooperative during the design process in

The Architectural History Of M-A

order for us to complete projects that the user is extremely satis ed with.” In addition to the C-2 renovation, Zito is also intrigued with the idea of possibly constructing a brand new building where the grass and secondary parking lot behind the football bleachers are. e building would include a second locker room, a student study center, and more classrooms.

written by Cole Trigg designed by Maddie Weeks

Student Protests Through Time

Menlo-Atherton has seen a recent increase of walkouts in the past few years. M-A students walked ve miles in protest against the Trump Presidency, most making it to University Avenue and a few even reached the 101 highway before returning to M-A (an additional four miles). Ignited by the Trump walkout, Bay Area students have protested against complacency with climate change, gun control, and women’s rights. However, these are not the rst protestors that University Avenue has seen. In the 1970s, students from Stanford University protested against the Vietnam War multiple times. Student protestors provide a vision of idealism to political chaos. While in the past college campuses typically have been agents for change, in recent years, high schoolers have begun to join the charge.

Palo Alto’s Vietnam War protests.

In 2017, M-A students walked out of school as part of the March for Our Lives movement. Students walked down El Camino Real to El Camino Park, meeting with students from other schools.

written and designed by Ellie Shepard photos by Lena Kalotihos and Palo Alto Historical Association

M-A’s Cultural Club Recipes

JEWISH CULTURE CLUB - POTATO LATKES

INGREDIENTS

- 6 large potatoes

- 2 onions, peeled and chopped

- 3 eggs, seperated

- 1 cup matzo meal

- salt, pepper, garlic powder

- 1 teaspoon paprika

- 1 tablespoon baking powder

- 2 cups of oil

Preparing Time 10 MINUTES

Cooking Time 30 MINUTES

Serves 12

DIRECTIONS

Place the potatoes in a cheesecloth and wring, extracting as much moisture as possible. In a medium bowl stir the potatoes, onion, eggs, matzo meal and salt together. In a large heavy-bottomed skillet over medium-high heat, heat the oil until hot. Place large spoonfuls of the potato mixture into the hot oil, pressing down on them to form 1/4 to 1/2 inch thick patties. Once brown on one side, turn and brown the other. Let the latkes drain on paper towels.

FRENCH CLUB - CRÊPES

DIRECTIONS

INGREDIENTS

- 1.5 cups of flour

- 3 eggs

- 3 spoons of sugar

- 2 big spoonfuls of olive oil

- 60 ml of milk

- 5 ml of rum

- 50 grams of melted butter

Place the our in a bowl and then mix it with the eggs, sugar, oil and butter. As you mix it, progressively add the milk. Place the rum progressively in the mixture to perfume it. Cook the crêpes placing a little bit of butter on your frypan under a soft re (from the gas under, around 30% of the way up). Preparing

POLY CLUB - MANGO OTAI

DIRECTIONS

INGREDIENTS

- 8 medium ripe mangoes (5 cups cut fruit)

- 1 carton of mocha mix

- 2 pineapple

- 1 ¼ cups coconut cream

- ¼ cup sugar

- 1 ¼ cups crushed ice

PREPARING TIME 10 MINUTES

COOKING TIME 30 MINUTES

SERVES 12

Peel and shred mangos into a large container or bowl add mangos as many mangos needed, mocha mix use as much of the mix that’s needed for the drink that’s being made in the container, pineapple as many that’s needed for your delicious beverage, coconut chunks from the nearest paci c shops, sugar and crushed ice. Mix with a large spoon to blend ingredients and dissolve sugar.

refrigerate or serve immediately.

*drink must be stirred before serving if it is held in the refrigerator

POLY CLUB - PANI POPO

DIRECTIONS

INGREDIENTS

- 20 frozen dinner rolls depending on size

- 10 oz. coconut milk (1 can)

- 1 cup sugar

PREPARING TIME 10 MINUTES

COOKING TIME 30 MINUTES

SERVES

2O ROLLS

Coat a 9x13 glass baking dish with cooking spray and arrange rolls evenly to thaw (if doing homemade rolls, roll dough into golf-ball size balls and arrange the same way). Cover with plastic wrap sprayed with cooking spray (to keep dough from sticking to the plastic wrap). Allow to rise until doubled in size. is can take 4-5 hours. If you need the rolls to thaw quicker, follow the quick-rise instructions on the frozen roll packaging. Preheat oven to 350-degrees. In a bowl, combine coconut milk and sugar and whisk until sugar is dissolved. Pour about 2/3 of the coconut mixture over the rolls and bake for 20-30 minutes (or according to package/dough recipe instructions) or until golden brown and dough is baked through.Remove from oven and pour remaining coconut mixture evenly over the top of the rolls. e rolls should be sticky and gooey on the bottom. Can be served upside down or right-side up.

written and designed by Sathvik Nori

FACES FACES OF FACES OF

M-A M-A M-A

II

present

illustrated by Karina Takayama

Bears at Work

Jennifer Garnica

Job: Stanford Dining Hall

“I decided to work mainly so that my parents don’t have to worry as much. I try to be independent, and not always depend on them. I balance work and school by picking a good amount of hours and days so I’m not too busy or tired to do my work at school.”

Katia Calderon

Job: Alice’s Restaurant

“Working has a ected me by making me more time e cient. I’ve learned to manage my time between work and school by doing homework during breaks and not letting my school work build up.”

Abel Valencia

Job: Paris Baguette

“I decided to work because I wanted to learn how to be independent and to be responsible. is has also helped me get on the path of adulthood.”

Alvaro Pena

Job: Stanford Dining Hall

“I decided to work because I wanted money that comes from hard work. Work a ects me in a positive way, and it is a good distraction from home. I do my homework in zero and rst period, when I don’t have any classes, to balance school and work.”

“Working has helped me to handle stressful situations, not take things personally, and learn to be more independent overall.”

— Juliette Dignum

Job:

May eld Bakery

“I try to not overthink [my schedule] that much because I’m doing this for my family, and I go to school for myself.”

— Violeta Alvarado

Shake Shack

written by Chloe Hsy and Violet Taylor designed by Chloe Hsy

Job:

Opinion: Serving or Spending?

Every year numerous M-A students participate in service trips to di erent countries. From building schools in Africa, to helping rural villages in Tonga, there is no shortage of opportunities for students to serve across the world. While these trips undoubtedly do some good, both in materially bettering conditions in these countries and giving students perspective on the poverty present in the world, some wonder whether these trips are the most e ective way to spend time and money.

Service trips are a multi-billion dollar industry in America, with numerous for-pro t and nonpro t organizations running trips that encourage people to pay money to travel across the world and give back to those who are less fortunate. Many M-A clubs are solely built around these trips, such as Bears Without Borders and buildOn.

However, for some students, doing service in the local community seems like a more effective use of time and money. Junior Indie Berkes said, “I have been on multiple service trips since 8th grade, and while it is a really good experience, it’s always better to do service in your community, especially when there are places that need help literally a mile away.”

Junior, and founder of Curieus, a club that teaches STEM to underprivileged youth, Rachel Park said, “I feel like a lot of people focus on service overseas when there is so much to be done locally.”

Another concern is that these trips can come off as paternalistic, reinforcing problematic conceptions of western superiority. “With the amount of money it takes to y to another country, it seems like a more e cient use of resources to hire workers in the region who are more skilled,” said junior Andrew Fahey.

Junior Ainsley Gentile said, “I feel like [the cost of the trip] weeds out kids who want to experience this deeper connection with other people around the

Bears

Without Borders is one of the many service organizations at M-A.

world, but don’t get the opportunity because of socio-economic status. It really isn’t fair.”

Nevertheless, almost all students who participate in one of these trips say that the experience was well worth it. Junior Gavin Plume said, “I think

on the outside world. Enabling genuine connections with people elevates the service to a personal level, something that oneday volunteering opportunities often lack.” e many service trips o ered at M-A do have a tangible impact on communities.

“I feel like a lot of people focus on service overseas even though there is so much to be done locally.”

-Rachel Park

[service trips] are so bene cial because they provide aid to communities in need and give M-A students valuable perspective

“It’s really valuable to see where the money you raise is going,” said senior and co-president of buildOn Nayna Siddarth.

“By going to the country, you get attached to the community, and are genuinely interested in seeing the nal result of whatever you are helping with. You can also see the long lasting impact of it on the community... you’re showing them that you genuinely care about helping.”

Fellow co-president Shreya Arora explained, “We’re not just going there and spending money; we’re leaving a community with something that will transform them and leave a lasting impact.”

Siddarth and Arora have traveled to Senegal and Haiti with buildOn. “We helped dig the foundation and put in the rst layers [of the building],” said senior Emily Zurcher, who has been on two buildOn trips. “Half

of our time was spent digging three foot trenches that would later be lled with stones, bricks, and concrete, while the other half was spent mixing said concrete, molding bricks, carrying rocks, and forming rebar chains.” Zurcher also explained that her trip “only started the process. e whole thing takes a few months to a year to build after we leave.” buildOn also does service in the local community first before going overseas. According to Arora, “Throughout the year, we do local service. To do work on a globalscale, rst you need to get to know your community, and help people around you.”

Senior Angela Chan, who travelled to the Kingdom of Tonga with Bears Without

Borders, said that the organization “has a long term vision for Tonga in order to build a strong and genuinely supportive relationship with the community; the [service trip] was an act of spending intentional time with the community of Talafo’ou, in addition to providing resources that would go beyond the two weeks that we were there. Being immersed in a culture and place so di erent than where we live gave us all intentional time to step back and challenge the barriers that stood between each of us.”

written by Sathvik Nori and Sarah Marks

designed by Sathvik Nori

buildOn recently went on a service trip to Haiti to build a school.

Gender Neutral Bathrooms: Students Express Cautious Optimism

e new gender neutral bathrooms in the G-wing are an attempt to provide a safe space for students of all gender identities at M-A. At the beginning of the year, the M-A Chronicle reported frustration among the student body over what some saw as poor implementation by Administration. At the beginning of the year, videos went viral of students peeing on boarded-up urinals. While there is less vandalism now, many students refrain from using the restrooms altogether.

“ e posters were just all torn down within a day,” said Gender-Sexuality Alliance (GSA) members about the day after the launch of their gender-neutral restroom poster campaign.

Junior Austen Dollente, GSA member, said some of the “original

hostility that a lot of students exhibited [has] died down a little bit,” but because of the original impact, “many of us who would actually benefit from the [gender-neutral bathroom] are afraid to use it.”

“Especially at the start of the year, there were a lot of people standing outside the bathroom watching people go in and out,” said Kai Doran, a junior GSA member. “A lot

cautious optimism as the bathrooms became normalized.

“A lot of people have told me that they’re [still] afraid of being harassed or teased because someone noticed them using it.”

At the beginning of the year, Doran said, “[ e Adminsitration] has not been very involved in the educational campaign, but that’s to be expected with the back-to-school chaos. I wouldn’t say they’ve been entirely passive, but they’ve hardly been active either.” Now, Administration “has mentioned the

possibility of getting district funding to add more stalls to it,” said Doran.

Principal Simone Rick-Kennel said, “We have an all-gender single stall student restroom in the gym lobby that was built when we remodeled the locker rooms last year. If we get more money for new construction, then we will build more all-gender restrooms for student use into the plans. New construction will allow us to build them by design versus having to reconfigure already existing restrooms.”

Administrative Vice Principal Stephen Emmi is working directly with the Gender-Sexuality Alliance on the issues surrounding the restrooms and commented that the club is promoting the use of the restrooms. “Some of the students from GSA are doing a poster campaign and they are planning on doing a segment on M-A Today! too,” said Emmi.

“Administration has made it clear that they support us producing posters and videos,” added Doran.

gender restrooms is a pilot, not whether or not we keep them. We de nitely want to have centrally located all-gender restrooms (based on student input) so we’ll evaluate the pilot location and determine whether we make changes to location.”

GSA member Serena Peters said, “Originally, when [other GSA members] and I went to talk to Emmi, the original agreement was to do the bathrooms in the upstairs G-Wing and convert both of them. at didn’t happen, and we don’t know why.”

Peters continued, “Move it

“The original agreement was to do the bathrooms in the upstairs G-Wing and convert both of them.”

Dollente concluded, “I think really, at the end of the day, M-A as a community needs to step up, but I don’t know how you do that. How do you change people’s beliefs about this stu ?”

Doran added, “I think that the bathrooms started a discussion about the rights of trans students and such, but we’re not done yet. It is de nitely a show of acceptance, and means a lot to trans students because a gender-neutral bathroom is just a way to say that we’re welcome here.”

“M-A as a community needs to step up.”

The restrooms continue to have problems and issues that make their usage limited. For instance, a stall lock does not work, the urinals are boarded up, and the restrooms lack disposal for feminine hygiene products, so students who are menstruating cannot use the restroom at all.

“I hear fewer derogatory and hurtful jokes now. But that doesn’t mean the impact from those initial comments and reaction is any less severe.”

Dollente said, “I hear fewer derogatory and hurtful jokes now. But that doesn’t mean the impact from those initial comments and reaction is any less severe.”

Kennel added, “It's hard to know how the whole student body has received the all-gender restroom pilot. I do see students of all genders using them; however, I think students still view it as a male restroom and more male students use them.”

Doran agreed. “Most students seem to still regard it as a male bathroom.”

Senior Nicole Knox said, “I tend to use the girl’s bathroom out of habit. I’ve been using it for four years so it’s more instinctual. I know [the other bathroom] is the gender neutral bathroom, but it still kind of seems like a male bathroom, with more male usage.”

At the beginning of the year, Kennel explained on M-A Today!, “You will nd we have an all-gender pilot. A pilot means we’re trying something new. We’re going to see how it goes.”

Some students were initially confused by her classifying the bathrooms as a pilot, thinking they could be removed at a later point, but in December Kennel clari ed. She said, “ e location for the all-

upstairs. Please move it upstairs. ey put the bathrooms in the most popular place in the school. By putting them there, we’re inconveniencing people and basically shoving it in their faces without any information. Now people are associating the inconvenience of the gender neutral bathrooms with the GSA and the people who use the bathrooms. If it’s upstairs, it’s like ‘Hey, that’s cool, these people have their space. is isn’t really impacting me. ey’re living their lives. ey’re people.’”

“We got a lot of input as to location preferences from GSA members and, also visited the Carlmont all-gender restrooms to get an idea of what we could do, and then gured out where on the M-A campus we could pilot one,” said Kennel.

written

and designed by Antonia Mortensen photographed by Brynn Baker illustrated by Karina Takayama Boarded up urinals in G-wing gender neutral bathroom.

A Cultural Club for Everyone

Dream Club

e Dream Club meets every Wednesday after school in B-20, and welcomes all students from di erent backgrounds and legal statuses. According to advisor Gonzalo Chavez, the Dream Club was created to “empower students from di erent ethnic backgrounds as well as legal statuses in the United States to further their education and career goals post high school graduation.”

e current presidents are senior Elder Lopez and junior Carlos Monterrosa, who have been part of the club since freshman year. e club focuses on community building, looking at political issues, improving public speaking skills, learning about colleges, and promoting cultural events.

BSU

e BSU (Black Student Union) club is run by senior Tuesday Burns. It aims to “connect with other BSU clubs within the Sequoia Union High School District to talk about things we want to change and things we notice around campus.” ey hold events to raise awareness for topics like vaping and nicotine addiction. Moreover, they hold fundraisers and festivities to celebrate holidays such as MLK Day. According to Burns, the club is not just for black students but “a safe community for all.”

POLY Club

e POLY Club is run by president James Pongi. is year the club wants to make sure they embrace Polynesian culture through activities, including “fundraising events, cultural days, and community events.” is year they have participated in club rush, performed at a rally and a senior night, gone canning, and contributed to Trick Or Treat Street. Pongi described the club as a “family.” e club also focuses on making sure each member is on top of their schoolwork.

Mandarin Club

e Mandarin Club meets every other Tuesday in E-13 during lunch. ey plan to celebrate events such as Lunar New Year and educate M-A students about Chinese culture. e club sells a variety of foods such as chow mein and fried rice every year for Chinese New Year and international week. Additionally they run booths with activities like calligraphy. e current leaders of the club are Michaela Fong and Ryan Jiang. e club welcomes any new members who are interested in learning more about the Chinese culture or Mandarin.

Bridge Club

Bridge Club president Lelani Tajimaroa stated that “Bridge Club aims to close cultural and ethnic gaps in the community with English Language Development (ELD) students, through making them feel more included in school and community events.” Bridge Club also plans events for ELD students and other club members, such as a celebration for anksgiving, a potential trip to the Cantor Art Museum, and an ice skating trip.

Jewish Culture Club

e Jewish Culture Club meets Wednesdays at lunch in D-21. Club President Ben Witeck said, “we plan to provide a space in which Jews and non-Jews may celebrate and learn about Jewish heritage in ways that respond to modern times and practices.” e M-A Jewish Culture Club is not a religious organization. Instead, it focuses on learning about Jewish culture, having engaged discussions, and participating in community service. is year the club hopes to plan a day trip to the Jewish Contemporary Museum in San Francisco.

Asian Culture Club

e Asian Culture Club meets on Mondays at lunch in Ms. Choe’s room, G-5. According to president Ben Chang, “Our club talks about politics, pop culture, holidays, food, stereotypes, discrimination, and more. We hold kahoot and jeopardy games discussing the topics.” e club also occasionally sells boba tea at lunch. Anyone is welcome to join the club.

LUMA Club

e LUMA club meets every ursday at lunch in F-18. According to president Paulina Gutierez, the club “hopes to create an environment where Latino students can come together to celebrate our diverse culture through di erent events and activities.” During their meetings they discuss di erent traditions and cultures in Latin America.

Intercambio

Intercambio meets every Wednesday at lunch in D-15. President Valentina Rivera states, “we focus on holidays, traditions and other celebrations and do activities we could do based these topics.” eir goal is to provide a collaboration space for native English speakers and native Spanish speakers to improve their English and Spanish skills. Anyone is welcome to participate in the club at any time, and many teachers encourage their students to join.

French Club

e French Club meets every other Monday in E-15, Ms. Tubiana’s room. President Anttoine Saquet states, “Our club’s purpose is for students to experience French culture during our meetings with lots of French food for everyone to try. We also watch movies together in French.” Any person is welcome to join the club.

written by Marlene Arroyo and Briana Aguayo designed by

Violet Taylor

Un club cultural para todos

Dream club

El Dream Club reúne cada miércoles después de la escuela en B-20, y le da la bienvenida a todos los estudiantes de diferentes origens e estatus legal. Gonzalo Chavez, el maestro consejero del club, dijo que el club fue creado para “empoderar a los estudiantes de diferentes orígenes étnicos así como los estatus legales en los Estados Unidos para continuar realizando sus metas de educación y carrera después de la graduación de la escuela secundaria.” Los presidentes del club este año son Elder Lopez y Carlos Monterrosa, quienes han sido parte del club desde que empezaron la secundaria. El club se enfoca en desarrollando una comunidad, discutiendo asuntos políticos, mejorando las habilidades de hablar en público, aprendendiendo sobre colegios, y promoviendo eventos culturales.

BSU

El BSU (Unión Estudiantil Afroamericana) club es dirigido por Tuesday Burns, una estudiante del grado 12. El club aspira a “conectarse con otros BSU organizaciones dentro del Distrito Escolar de Sequoia y discutir las cosas que quieren cambiar y lo que observan alrededor de la escuela.” Planean eventos enfocados en despertar conciencia sobre temas alrededor del fumando electrónico y la adicción a la nicotina. También organizan recaudaciones de fondos y festividades para celebrar eventos como el Día de MLK. Según Burns, el club no solamente es para estudiantes afroamericanas pero “una comunidad segura para todos.”

Club POLY

El club POLY, o polinesio, es dirigido por James Pongi. Este año quieren asegurarse de mostrar la cultura polinesia con actividades como “recaudaciones de fondos, días culturales, y eventos comunitarios.” Este año han participado en club rush, una noche de seniors, han colectado latas, y contribuido al Trick Or Treat Street. Pongi describe al club como una “familia.” El club también se asegura de que cada miembro ponga su mejor esfuerzo con respeto a los académicos.

Club de mandarín

El club de mandarín se junta en E-13 durante almuerzo el martes cada mes. Planean celebrar eventos como el Año Nuevo Lunar y educar a los estudiantes de M-A sobre la cultura China. Durante Año Nuevo Lunar, el club vende una variedad de comida, como chow mein. También, el club ofrece varias mesas con actividades como la caligrafía. Ryan Jiang y Michaela Fong son los líderes del club. El club espera dar las bienvenidas a miembros nuevos interesados en aprender sobre la cultura china o el idioma mandarín.

Club de cultura judía

El club de Cultura Judía reúne los miércoles en el salón D-21. Según Ben Witeck, presidente del club, “planeamos establecer un espacio para que estudiantes Judíos o no Judíos puedan celebrar y aprender sobre la herencia Judía de una manera que responda a tiempos modernos.” No es un club de religión Judío, sino de la cultura Judía, y el enfoque del club es educación, discusión, y servicio comunitario. Este año escolar, el club desea planear un paseo al Museo Judío Contemporáneo en San Francisco.

Bridge club

La líder del Bridge Club, Lelani Tajimaroa, explica que el “Bridge Club intenta cerrar brechas culturales y étnicos en la comunidad con estudiantes ELD, para hacerlos sentir incluídos en los eventos de la escuela y comunidad.” Bridge Club también planea eventos para estudiantes ELD y los miembros del club como una celebración del Día de Acción de Gracias, un paseo posible al Museo Cantor, y un paseo para patinar en hielo.

Club de cultura asiática

El club de Cultura Asiática reúne los lunes durante el almuerzo en el salón de Ms. Choe, G-5. Según presidente Ben Chang, “Nuestro club habla sobre la política, temas culturales, días festivos, la comida, estereotipos, discriminación y más. Organizamos juegos de Kahoot y Jeopardy sobre nuestros temas.” De vez en cuando, el club también vende té de boba durante el almuerzo. Todos son

bienvenidos al club.

Club LUMA

El club LUMA tiene reuniones todos los jueves durante el almuerzo en el salón F-18. Según la presidenta, Paulina Gutiérrez, el club “espera crear un lugar donde estudiantes latinos puedan juntarse para celebrar nuestra cultura diversa a través de diferentes actividades y eventos.” Durante sus reuniones tienen discusiones sobre las diferentes tradiciones y culturas de Latinoamérica.

Intercambio

Intercambio reúne cada miércoles durante almuerzo en el salón D-15. Presidenta Valentina Rivera explica, “enfocamos en días festivos, tradiciones y otras celebraciones, y creamos actividades que podemos hacer basados en ellos.” La meta del club es aportar un espacio de colaboración para que hablantes nativos del inglés e hispanohablantes mejoren sus habilidades de inglés y español. Todos son bienvenidos a unirse al club en el tiempo que sea, y muchos maestros animan a sus estudiantes a unirse.

Club francés

El club francés reúne cada otro lunes en E-15, el salón de Ms. Tubiana. Presidente Anttoine Saquet describe que “el propósito de nuestro club es que estudiantes experimentan la cultura francesa durante nuestros reuniones con mucha comida francesa para que todos prueben. También miramos películas francesas.” Cualquiera persona es bienvenida a ser parte del club.

por Marlene Arroyo and Briana Aguayo diseño por Violet Taylor

Editorial:

REPRESENTATION STUDENT WHAT IS &

ISN’T

By fth period on November 15th, M-A had reached a boiling point. Over two hundred students left class to protest the proposal to end the policy of teachers handing out graduation diplomas, leaving some classrooms nearly empty. e lunch period before the sit-in, administration held an open forum in the library for students to voice their concerns. e subsequent protest on the Green revealed a build-up of student anger toward the administration stemming from a feeling of being voiceless.

e Mark sta believes that to remedy the crisis of misunderstanding between students and sta , administration should enact consistent and accessible channels of communication; students must use and respect these channels instead of resorting to protest and personal attacks; and we —student journalists —must inform the student body in a timely manner of proposed changes to encourage informed action.

Currently, the Shared DecisionMaking Site Council (SDMSC) is M-A’s formal channel for student representation. According to the M-A website, the SDMSC holds monthly meetings to make “policy decisions for the school” and is where the proposal to end the graduation diploma tradition originated. While any student can attend meetings, only students vetted through leadership, such as class advisors and presidents, are allowed a vote in the council. In total, the student body is allowed four votes.

Of the students interviewed by the Mark sta , few were aware of SDMSC meetings and none have ever been to one. Senior Elonjanae Wilson Banks said, “I’ve heard of meetings where students can go, but I don’t know much about it.”

Among students eligible to vote on the council, two are regular attendees: junior Annika Abdella and senior Angela Chan. None of the students the Mark interviewed seemed to know who their representatives on SDMSC are. Senior Amy Parada said, “I didn’t know about [the SDMSC]. I don’t even know who our class presidents are.”

Clearly, we have a communication de cit. While the SDMSC serves as a decision-making body where students can express their voices, most are woefully unaware of its existence and the topics addressed. Who should students reach out to for their opinions to be considered by representatives in the SDMSC? ere are currently no student names or contact information listed in the representative slots on the SDMSC page of the M-A website. In order to represent the will of the student body, then, voting representatives must resort to guesswork.

Another issue is the assumption that the views held by the student representatives are re ective of those of the entire student body. Chan said that the student representatives are drawn from the Associated Student Body (ASB) advisory board, a group that —apart from each grade’s President and Vice President —is not elected by the student body.

As the M-A Chronicle reported in September, Leadership will discontinue the class president position going forward over concerns of election foul play, meaning there will be no elected student representation under the new model. Last year, a Mark investigation revealed that the lack of security in the voting process allowed for votes from non-M-A students to be included in the nal tally–only 57% of the votes were valid. Additionally, confusion around when the ballot would close resulted in a victory that some suspected was part of a conspiracy.

Last year, Leadership invested in new voting software, but the disrespectful behavior of students plagued the campaign. Amoroso said, “I was thoroughly embarrassed to be the advisor who runs the elections, due to the students slandering their own classmates’ names, starting rumors like people are able to buy their votes, and probably the most disgusting and embarrassing moment —when [a yer with a picture of] two candidates was urinated on in a toilet.”

It’s easy to peg the discontinuation of the class presidency as an attack on student

“Students were

‘upset about being left in the dark and passionate about being heard.’

Read Related Stories:

Who Really Won the Class President Election?

New Election Software Will Ensure Voting Security

Ending the Class Presidency

Students Walk Out in Protest of Graudation Changes

Another Side of the Diploma Controversy

voices, but until the student body can learn to respect the process of democracy, do we deserve to have this voice? Amoroso is not the rst activities director to eliminate class elections. In fact, he revealed that every activities director in recent memory has ridden the school of class elections at some point in their time at M-A.

Student behavior and rhetoric at both the open forum and the sit-in got ugly. e main takeaway of many students’ speeches was “f--- admin” and one student was seen blaming the principal for her suspension while brandishing her middle ngers; a gesture intended for principal Simone RickKennel. In the case of the graduation diploma controversy, Chan said tensions ran high at the open forum during lunch with members of the administration because “it was the rst

Tensions between students and members of the administration ran high at the open forum.

formal opportunity for students to speak directly with sta .” Chan continued, “If

people during the sit-in were mad at admin. I don’t think that admin even knew that so many students wanted to [keep the diploma tradition]. I think they just thought students didn’t really care.” Mimeles explained that a sit-in was the easiest way to organize masses of students to share their opinions. She addressed how at times the sit-in got out of hand, but said it was ultimately a success because in January, the SDMSC voted to keep the tradition.

While a high school is not a proper democracy, the student perspective is a necessary component to a harmonious campus, and open discussion encourages young people to learn self-advocacy skills for the future. In practice, though, democracy is tedious. Few students are willing to endure long meetings discussing budgeting details with administrators, and several students from leadership, though not elected representatives of the student body, have been commendable for their willingness to undergo boredom for the sake of being heard. In fact, M-A’s lack of student-administrator conversation originates from students’ disinterest over time. During the 2017-2018 school year, Kennel and the administration o ered regular open forums called Bear Chats. e forums were discontinued after student interest waned; according to Kennel, “Few students came, and if they did, it was more speci c to their situation that could be addressed via another

performative, and teens can be counted on to go to extremes to make their friends laugh. Here there is an important distinction: at the sit-in, some students

The most effective thing to do is to provide regular avenues for student expression.

took the chance to poke fun at and roast administration, while others took the chance to bring up unrelated issues and concerns because it felt like their one opportunity to be heard. As always, the excitement for student representation should be for the right reasons, not for the thrill of cutting class or to meet up with one’s friends during fth period on a Friday. e sit-in was an important catalyst for the decision to uphold the diploma tradition, but ultimately the most e ective thing to do is to provide regular avenues for student expression.

If the SDMSC is to be accepted as the primary means for student representation in policy decisions, the administration should publicize (a) how the body operates

“The excitement for student representation should be for the right reasons, not for the thrill of cutting class or to meet up with one’s friends during fifth period on a Friday.

anything, I think the open forum revealed the urge that students feel to be heard by the administration and the lack of attention they felt that they had received up to that point.”

Senior Isabelle Mimeles, who helped organize the sit-in, said, “A lot of

channel.”

Surely the enthusiasm for the sitin, though partly from genuine concern over continuing tradition, also arises from the glamour of protest. In any demonstration like the one on the Green, participation becomes

with regards to policy-making and student representation and (b) the topics and proposals on M-A Today!, Canvas, or via emails so that students remain informed. According to Chan, in the case of the graduation diploma proposal, students were “upset about being

left in the dark and passionate about being heard.” Had the administration involved students more in the decision-making process by sending out a school-wide announcement asking for input, perhaps students wouldn’t have felt blindsided and been driven to protest.

e contact information of students who serve on the SDMSC should be published on the SDMSC website, so a variety of students may inform their representatives of their needs. Originally, the student SDMSC representatives were not posted because of a lack of consistent attendance. Students like Abdella and Chan, who have committed to being consistent student voices at the SDMSC this year, should be an example for future representatives.

Moving forward, the journalism sta of both the Chronicle and e Mark commits to having at least one journalist in attendance at future SDMSC meetings. As journalists, we have a responsibility to

inform students on any proposed or enacted changes to their community, which requires more thorough reporting on the SDMSC. We too can do better. Many students rst found out about the proposed changes to the diploma tradition by way of a social media post promoting the protest. With journalistic representation at SDMSC meetings, students will be able to access credible, fact-checked information without worrying they have been kept out of the loop.

is semester, the administration has proposed monthly student town halls led by SDMSC representatives. Kennel described that the meetings will take place during ex time in the PAC “to update students on issues that come up through the SDMSC.” ese town halls are a step in the right direction; their time and place will be accessible to all interested students, and the format of open discussion will promote transparency between parties.

Chan said, “Being one of the few

student reps in SDMSC, there are only so many people we can talk to and things we can say to try to in uence these school-wide decisions.” When the administration expands the open forums to town hall meetings, students should speak up if they are bothered by a policy or a lack thereof. at said, students should also be willing to respect and listen to the concerns of administrators. Chan said students should “understand that the administration is reaching out to them for feedback” in these forums and not “jump to conclusions.”

A democratic system only works when there is a frequented platform for constituents to make their voices heard. Both students and administrators must approach these conversations with empathy and a willingness to compromise; at M-A, a healthy system of representation cannot exist without either.

written by The Editorial Board designed by Toni Shindler-Ruberg

Students sit out during lunch, November 15th. | Credit: Erik Hansen

MASCULINITY TOXIC

a set of behaviors and beliefs that include the following: - Suppressing emotions or masking distress - Maintaining an appearance of hardness

- Violence as an indicator of power

“ at’s so gay.” “Don’t be a pussy.” ese are words that are often thrown around at high school campuses, including M-A. While seemingly harmless, these words have an impact; our society often forces men to act domineering and emotionless, and objectify women. Although recent movements have emphasized how toxic masculinity harms women, what is often left out of the discussion is the e ects toxic masculinity has on men themselves. In a country where men have a suicide rate 3.5 times higher than women– a trend caused by increasing levels of loneliness among teen and middle-aged men – toxic masculinity is quickly becoming a serious issue.

From a young age, boys crave friendship and closeness with other boys. In almost all psychological studies, adolescents between the ages of seven and twelve talk about how much they love and care for those they describe as their “best friends.” However, when these same boys are interviewed as teens something completely di erent happens. When asked, the same kids are hesitant to talk about their male friends and they are distant and isolated from them. Junior Lars Osterberg said “I think a lot of guys are scared to have close friends. Especially when they get to high school,

the culture can be pretty homophobic...even if it’s not by choice, a lot of guys just automatically hide their emotions. For me personally, I feel like I do it naturally because of past experiences I have had.”

An anonymous male senior agreed, saying, “I feel like there is a culture that forces guys to suppress their emotions in front of their male friends. I know that not every male is super emotional, but for those who are, it can often seem hopeless and depressing.”

In our culture, boys are often told to “man-up,” believing that they shouldn’t be sad and that showing emotions is a sign of weakness. According to Mills, “While some guys can handle these pressures without any struggle, others simply can’t.” Unfortunately, this culture causes many men to isolate their feelings making them internally depressed. Ultimately, this can have grave consequences later in life. At the same time when teen boys start to view intimate relationships as “gay” and isolate themselves more, their suicide rate peaks to four times that of girls. In the long run, this emotional isolation leads to serious mental and physical issues, ranging from chronic depression to anxiety and hopelessness. e pressure on boys to act stoic

I know that not every male is super emotional, but for those who are, it can often seem hopeless and depressing. - Anonymous

often leads to impossible expectations that destroy mental well-being and severely harm boys’ psychological development. e problem is further fueled when boys feel pressure to “act di erently,” because they “see others doing it,” according to senior Matthew Bergan. e culture of hyper-masculinity has taken basic traits of humanity, such as displaying emotions, and assigned them as female characteristics even though all humans have emotions. Boys enter a culture that asks them to pretend as if their emotions do not exist and disconnect from the very thing they need the most to help them

the winter