The Mark

Falling into Place

The Mark

About This Issue

In this issue, e Mark celebrates the theme of “Falling Into Place” to acknowledge our community’s gradual return to normalcy. Long-missed scenes of friends at dances and sporting events ll our pages to make readers hopeful for the coming year. As we approach the re-opening date, we continue to provide an open forum for students to advocate for a more just and accepting community. In this issue, we introduce our new editors-inchief and say goodbye to our seniors. Like everything this year, journalism was asked to reinvent itself, and our editors rose to the challenge, worked us to the bone (we hope it was worth it!), won a national prize, and enjoyed the strongest community engagement in recent memory. Seniors, we won’t miss this year, but we will miss you.

Policy

e Mark, a feature magazine published by the students in Menlo-Atherton’s journalism class, is an open forum for student expression and the discussion of issues of concern to its readership. e Mark is distributed to its readers and the students at no cost. e sta welcomes letters to the editor, but reserves the right to edit all submissions for length, grammar, potential libel, invasion of privacy, and obscenity.

Journalism Advisor Volume XII Issue II | Summer 2021

Submissions do not necessarily re ect the opinions of all M-A students or the sta of e Mark. Send all submissions to submittothemark@gmail.com. To contact us directly, email us at themachronicle@gmail.com.

Staff

Brianna Aguayo

Isabelle Stid

Katherine Welander

Jane White

Chloe Hsy

Amelia Wu

Ashley Trail

Kari Trail

Marlene Arroyo

Brynn Baker

Sheryl Chen

Amelie Chwu

Triana Devuax

Kai Doran

Grace Hinshaw

Ellie Hultgren

Abby Ko

Izzy Leake

Ally Mediratta

Sathvik Nori

Mae Richman

Violet Taylor

Cole Trigg

Annie Wagner

David Wagsta

Emily Xi

John McBlair

Editor-In-Chief

Editor-In-Chief

Editor-In-Chief

Editor-In-Chief

Managing Editor

Managing Editor

Layout Editor

Layout Editor

Quarantine Comics: Expectations vs. Reality

designed and illustrated by Ashley Trail

I should try some quarantine hobbies!

We need to reopen schools!

A two-week quarantine isn’t too bad!

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Student Submissions

Elinor Kry (junior)

Elinor Kry (junior)

Nicole Bouthillier (senior)

Carson Reader (senior)

Ashley Trail (senior)

Caption Contest

“What I’m wearing vs. what my mom thinks I’m wearing.”

Stella Kaval (senior)

High Mark

National boba shortage Schoolbackin-pers on

“School.”

Will Davis (junior)

Increase in available vac c ines

Low Mark

Ann’s Coffee Shopcloses

designed by Chloe Hsy illustrated by Ashley Trail

OH THE PLACES THEY’LL STAY... Why M-A Graduates Stay In-State for Four-Year University

While the United States boasts more than 3,000 four-year universities, most of which extend much further than the state we call home, 52.33% of M-A graduates bound for a four-year university remained in-state for school from 2017-2020. e second and third place states pale in comparison, with 5.58% of students attending college in Massachusetts, and 4.67% attending school in New York. is ultimately comes down to California’s warm weather, lower price tag, and the convenience of living closer to home.

To explain these numbers, College Counselor Mai Lien Nguyen said, “Nationally, 50% [of] high school students stay within 500 miles of their hometown when choosing a college, so it would not be unusual for our students to choose colleges

in California. However, in the last ve years, if we were to look at only four-year collegebound M-A graduates, there is an almost 50-50 split between students who remained in California and those who left California. So M-A graduates are slightly higher than the national average for students going outof-state.”

“‘Being close to home is actually really nice and beneficial, especially during the pandemic.’”

very in uential factor in choosing a four-year university.

UC Davis junior Tori Rarick said, “I stayed in-state because it’s much cheaper, and it makes more sense to save that money for graduate school rather than spend a fortune on the same education out of state.”

UC Santa Cruz freshman Karla Lopez added, “I chose to stay in-state for college because it was better for me nancially, especially in terms of transportation to and from college.”

College Counselor Heather Lowe explained that the reason many attend instate universities is largely nancial. She said, “If a student doesn’t qualify for need-based nancial aid, then in-state tuition is the most a ordable. For students who can’t a ord the high cost of paying for housing and a meal plan, commuting to college saves a ton of money. And lastly, another signi cant cost is travel—cutting out the cost of ights is another signi cant way to save on college.”

For instance, UC Berkeley’s yearly tuition is listed at $14,253, while the private New York University’s is posted at $53,308, both excluding room and board. Since these schools have similar levels of prestige, the price tag is often a

Rarick added, “Being close to home is actually really nice and bene cial, especially right now during the pandemic. College is already expensive and by staying in-state I’ve been able to save money on not only tuition, but plane ights or traveling. I can also drive home any weekend if I need to, which has been really nice.”

Similarly, UC Santa Barbara freshman Nancy Lopez said, “I can visit my family whenever I want, and the weather is so perfect.”

A consensus amongst in-state students interviewed was that staying in California did not deprive them of the “sense of adventure” that going out-of-state is usually associated with. For example, UCLA freshman Sophia Wendin said, “I’ve loved staying in California because of the weather and the good food. I’m also in a new city

“‘I’m also in a new city and a different part of California than I grew up in, so it still feels like I’m doing my own thing and getting to know a new place.’”

and a di erent part of California than I grew up in, so it still feels like I’m doing my own thing and getting to know a new place.”

Four-year universities in California have also attracted M-A graduates because many of them are prestigious, or cater to students’

individual preferences. UCLA freshman Joanne Yuh added, “I was okay with going to college far away from home, so the school’s location didn’t really matter to me. So when I compared the colleges I got accepted into, I looked at which school would be the best academic and social choice for me and decided to go to UCLA, which happened to be an in-state school.”

is is a common theme among many students in California because the UC and CSU schools have become more selective and have more generous admission rates for incoming freshmen from California. Forbes reports, “UCs remains a top-rated pick for eligible high school graduates both inside and outside of California. California

lawmakers are sure to continue putting pressure on state schools like UC and CSU to increase in-state enrollment.”

California Polytechnic State University (Cal Poly SLO) freshman Will Hultgren said, “I was expecting to go out-of-state for university, but I got into Cal Poly!”

written and designed by Jane White

Number of Students Attending Each Four-Year University in California (Classes of 17-20)

Check out mabears.org to see which community colleges and out-of-state universities the M-A grads from classes of 2017-2020 attended as well.

CA Lutheran University 1 California Institute of the Arts 1

CSU Bakers eld 1

CSU Cal Poly SLO 51

CSU Cal Poly Pomona 5

CSU Channel Islands 1

CSU Chico 14

CSU Dominguez Hills 1

CSU East Bay 18

CSU Fresno 2

CSU Fullerton 3

CSU Humboldt 5

Number of Students Attending Four-Year Universities

CSU Long Beach 1

CSU Los Angeles 2

CSU Maritime Academy 1

CSU Monterey Bay 2

CSU Northridge 1

CSU Sacramento 5

CSU San Diego State 13

CSU San Francisco State 51

CSU San Jose State 27

CSU Sonoma State 17

CSU Stanislaus 1

What’s the Deal with Cheating?

written by Isabelle Stid

designed and illustrated by Kari Trail

O f102anonymous students polled,81%saidtheycheat more since thestartofdistance learning.

Of 102 anonymous students polled, 81 said that cheating is easier and they have done it more since the start of distance learning. It does not come as a surprise to many that distance learning has led to students cheating more, but the extent to which is still shocking. According to M-A’s academic integrity policy, any form of cheating and plagiarism are not allowed and should be reported to the AVP o ce to be put on the student’s record. It appears, however, that few cases are caught or reported: only ve cases of academic integrity violations were logged in In nite Campus for the 20202021 school year, despite both teachers and students alleging a massive spike in cheating.

Pre-Calculus teacher Manja McMills said, “In a normal school year, I don’t really have much of an issue.” is year, however, she has already caught several students cheating.

43% of students polled did not consider breaking the school’s academic integrity policy “a bad thing to do.”

One student said, “Who is to say what is right or wrong? It’s about playing by the rules, and advancing the best you can with what you got.” Another student said, “If I nesse the teacher then that’s on him, not me.”

One student who did think cheating was morally wrong, but still did it said that “with the societal stress of getting perfect grades, it just seems normal to cheat to do better, but it doesn’t excuse the fact that it is wrong.”

Other students felt that cheating was not wrong and if anything prepares them for the future. One student explained, “In the real world, everything is open note and you can collaborate with other people to nd solutions to problems. Taking tests without resources and the help of others, while it does help individual growth, does not prepare students for what their future will actually look like.”

Teachers, however, had di erent ideas on why students are cheating more. McMills thought the rise in cheating was because “it’s super hard for students to be disciplined right now when they’re at home. And when they have all these things at their ngertips to be able to cheat, I could see how it’s very tempting.”

AP Computer Science teacher Cindy Donaldson thought that the rise in cheating wasn’t “malicious and more just blurred boundaries.” In Donaldson’s mind, to ght the culture of cheating, teachers “need to be very clear about what they consider to be cheating, and what they don’t consider to be cheating. For every assessment, I think it’s really important to state clear boundaries. Because the boundaries are so fuzzy with distance learning… it’s important for teachers to recognize how widespread [cheating] is, and to not pretend it’s not happening.”

If anything, widespread is an understatement: only 11.7% of students polled

Math and science classes are especially susceptible to cheating—McMills, Donaldson, and fellow math teacher Tomiko Fronk all saw a rise in cheating this year. In McMills’ class, students used the AI app Photomath on a test. She discovered it because “the way they solved the problem was just the way a computer would think, and not the way a person would.” Since then, McMills has tried “to create tests where they can’t use Photomath and try to think of new ways to test students.”

Donaldson, on the other hand, learned a few years ago how easy it is for students to cheat and help each other, and decided to change how tests are given in her class. “I generally go on the assumption that everyone is helping each other, and I try to make most of my assessments around that idea, and not try to pretend that they’re not.”

Similarly, another student said “In the real world, you have resources and other people to help you. Why can’t we simulate this in school when we are supposed to be preparing for our life?”

One student explained that in their mind, students are cheating more because “during distance learning, teachers can’t expect students to fully complete the same test with the same rigor as if we were back at school normally. e fact is that people aren’t learning as well but teachers have the same expectations.”

had not broken the school’s academic integrity policy on a test, and 77.7% of students polled thought that cheating is very prevalent at M-A. is matters because studies show that if you think everyone else around you is cheating, you are far more likely to cheat as well.

AVP Nicholas Muys thought that students cheat because “grades become this kind of extra pressurized realm where... students feel the need to cheat to operate within this very complicated system.”

Teachers interviewed believed student stress was the biggest contributor to cheating. McMills said that “I think a lot of it has to do with not the school but the society we live in, the Bay Area. ere’s so much pressure for everyone to feel like they have to be the best and if you don’t get into an Ivy League school that they are a failure, and I always try to tell my students, ‘that’s not the end goal.’”

Students also felt that stress and their workload led to them cheating. One student explained that “ultimately the reason we are doing it is due to our incapability to complete the work the teachers have assigned, so it’s best to tackle the problem at its root.”

Donaldson, who thinks cheating is “widespread everywhere,” uses catching a student cheating as a learning opportunity to discuss bigger issues. “ is is also a lesson about honesty and ethics, and so if the student can walk away having learned something about honesty… to me [teaching that] is part of my job as a teacher.”

Looking at the bigger picture, Muys said he felt that cheating was wrong because “you can’t take somebody else’s idea and call it your own... that has huge consequences, not only to one’s reliability as a source of information but as a participant in the academic and scienti c realm. You can’t do that to somebody else who has worked hard to develop those ideas.” McMills said, “a lot of [cheating] has to do with the teachers, and how helpful the teachers are. I think sometimes when kids are scared of their teachers, they don’t reach out for help as much. When they don’t understand something, I think they panic and they cheat.”

History teacher Ahzha McFadden wanted students to know that “if you go to a teacher and are like, ‘I don’t understand this. Can you help me?’ they’re gonna say yes—that’s literally our job.” McFadden expressed that if students feel overly stressed or overworked they should “go to their teacher...they’re going to be understanding. You’re human. We’re human. We are going to cut you some slack.”

Colorism: Hidden in Plain Sight

“Growing up I’ve noticed that I have darker skin than my siblings and how things are easier for them, like nding the perfect shade of makeup or getting to wear whatever color of clothing they want because their skin color looks ‘better’ with them than mine,” said Junior Gaby Martinez.

Colorism, an issue that occurs throughout various ethnic and racial communities, is de ned as discrimination or prejudice against someone with a darker skin tone, typically within one’s own ethnic community.

English teacher and advisor for M-A’s Black Student Union, Sherinda Bryant said that while racism means “blocking access to institutions because you have the power to do so,” colorism means, “blocking one’s access to a certain thing because of their skin tone. It exists within di erent communities. It’s not just a Black thing; the Latinx community has it, and Middle Eastern people, et cetera. Everybody has been taught to some degree that the lighter you are—the closer you are to white—the more beautiful or more pure you are.”

Joanne Rondilla, a professor of Interdisciplinary Studies and Sociology at San Jose State University and Co-Author of the book Is Lighter Better?, said, “if you come from a racial or ethnic group that has been colonized or was a ected by colonization, then you are a part of a group that has been a ected by colorism.” Although people carry di erent experiences, people with lighter skin tones don’t experience colorism because it speci cally discriminates against darker members of an ethnic community.

Junior Brenda Rivera said, “I think colorism is an issue among many people of di erent ethnic groups because for the most part they see other darker skin colors as ‘dangerous,’ because of long years of history where they have been portrayed negatively.”

Junior Savvanah Prasad said that although she had not experienced colorism at school, these instances can occur casually

with family members. She said, “Older relatives have told me, ‘Oh don’t stay out in the sun too long, you know dark skin isn’t pretty; dark skin is not desired.’”

“If either you were an immigrant or your parents or grandparents were of the immigrant generation, then you grew up with these ideas of colorism, with this idea that lighter is better, and darker skin is not as valued. Oftentimes, that immigrant generation is re ecting the values of their home country,” Rondilla said.

“‘If either you were an immigrant or your parents or grandparents were of the immigrant generation, then you grew up with these ideas of colorism, with this idea that lighter is better, and darker skin is not as valued.’”

In Asian countries like India, skinlightening goes back to centuries ago, even beyond periods of colonialism. Prasad said, “As an Indian, the issue of colorism is sadly a big part of the culture. In India, they have skin lightening and whitening products speci cally made for darker skin women to lighten up their skin in order to be considered beautiful because of the beauty standards in India, the Philippines, South Korea, and many other countries.”

Products like dark spot reducers and other skin-lightening creams have only recently been discontinuehd by some brands owned by the Johnson & Johnson corporation. According to the World Health Organization, “Even in countries where such products have been banned, they are still advertised and available to consumers via the Internet and other means.”

Junior Diana Castro said that when she was younger she struggled with colorism. “I strongly desired a lighter skin color, colored eyes, and straight hair. I think the reason for that is because of what the media has enforced for years upon years. We see it in movies, social media, schools, and history.”

Since then, Castro explained, she has “grown to love my skin tone, and who I am, and what I represent.”

written by Marlene Arroyo and Brianna Aguayo designed by Sheryl Chen

Although many argue that colorism began during times of slavery and colonialism, it goes back further than that.

Dr. Sarah L. Webb, an assistant professor at the University of Illinois and author, explained, “historically, those who’ve attained power and have been able to hoard it have had lighter skin, either through European ancestry or being an upper caste system, depending on where they are from.” us, having a lighter skin color has become a privilege within one’s own ethnic group.

Dr. Webb said that students who face colorism, “have to be willing and have the courage to acknowledge what’s happening to them.” She urged students to, “be willing to ask that question” of whether one was chosen for a certain position over them due to their skin color, and “know that people are going to say, ‘oh, you’re just jealous,’ or ‘you’re being divisive,’ or ‘who cares?’”

Junior Jade Alexander, said that she had experienced a few instances of colorism at school. “Going to a [predominantly] white school from K-8th grade de nitely in uenced how I thought of myself. It wasn’t until 7th grade when I became completely con dent with my Blackness and the color of my skin,” she explained.

She added, “I really think it’s going to take a while for ethnic groups to embrace their Blackness or dark skin in general.”

“Your generation has such an opportunity to continue to push back. When young people understand how much power they have in shifting that dynamic. I believe it’s going to change even more,” Bryant stated.

Colorismo: Oculto a Plena Vista

escrito por Marlene Arroyo y Brianna Aguayo diseño por by Sheryl Chen

“Creciendo, me he dado cuenta de que tengo la piel más oscura que mis hermanos y de que las cosas son más fáciles para ellos, como encontrar el perfecto tono de maquillaje para sus pieles o ponerse el color de la ropa que quieren porque su color de piel parece ‘mejor’ con ellos que con el mío,” dijo Junior Gaby Martínez.

El colorismo, un tema prevalente que ocurre en varias comunidades étnicas y raciales, se de ne como discriminación o prejuicio contra alguien con un tono de piel más oscuro, típicamente dentro de su propia comunidad étnica.

Profesora de Inglés y consejera de la Unión de Estudiantes Afroamericanos en M-A, Sherinda Bryant dijo que mientras “el racismo signi ca bloquear el acceso a las instituciones porque usted tiene el poder de hacerlo.” El colorismo signi ca que “se puede bloquear el acceso a una cosa debido a su tono de piel, que existe dentro de diferentes comunidades. No es una cosa de Afroamericanos, la comunidad de Latinx lo tiene, gente de Oriente Medio, et cetera. Todo el mundo ha sido enseñado a un cierto grado que cuanto más claro eres, más cerca estás del blanco, y más hermoso/a eres o más puro/a eres.”

Joanne Rondilla, profesora de Estudios Interdisciplinarios y Sociología en la Universidad de San José y coautora del libro ¿Claro Mejor? dijo, “si usted viene de un grupo racial o étnico que ha sido colonizado o afectado por la colonización, entonces usted es un grupo que ha sido afectado por el colorismo.” Aunque las personas tienen experiencias diferentes, las personas mas claras no son afectadas por el colorismo porque discrimina especí camente a los miembros más oscuros de una comunidad étnica.

Junior Brenda Rivera dijo, “Yo creo que el colorismo es un problema entre muchas personas de diferentes grupos étnicos porque por gran parte otros ven la piel oscura como ‘peligrosa,’ dado a los años largos de historia donde han sido retratados negativamente.”

Junior Savannah Prasad dijo que aunque no había tenido experiencia con colorismo en la escuela, estas instancias ocurren casualmente con miembros familiares. Ella dijo, “Parientes mayores me han dicho, ‘Oh no te quedes en el sol por mucho tiempo, ya sabes la piel oscura no es bonita, la piel oscura no es deseada.’”

“Si tu eres un inmigrante o tus padres o abuelos eran de la generación inmigrante, entonces creciste con estas ideas de colorismo, con esta idea de que lo claro es mejor, y la piel más oscura no es tan valorada. A menudo, esa generación inmigrante está re ejando los valores de su país de origen,” dijo Rondilla.

“‘Si tu eres un inmigrante o tus padres o abuelos eran de la generación inmigrante, entonces creciste con estas ideas de colorismo’”

En países asiáticos como India, donde el aclaramiento de la piel es común desde hace siglos, incluso más allá de los períodos de colonialismo. Productos como reductores de manchas oscuras y otras cremas para aclarar la piel han sido descontinuados recientemente por algunas marcas de la corporación Johnson & Johnson. Según la Organización Mundial de la Salud, “incluso en algunos países donde tales productos han sido prohibidos, todavía son publicados y están disponibles para los consumidores a través del Internet y otros medios.”

Prasad dijo, “Como India, el tema del colorismo es tristemente una gran parte de la cultura. En India, tienen productos para aclarar y blanquear la piel hechas especí camente para que las mujeres de piel más oscura se aclaren la piel para ser consideradas hermosas para los estándares de belleza en la India, Filipinas, Corea del Sur, y muchos otros países.”

“Deseaba fuertemente un color de piel más claro, ojos de colores y pelo lacio. Creo que la razón de esto es por lo que los medios de comunicación han esforzado por años y años. Lo vemos en películas, redes sociales, escuelas e historia,” dijo Junior Diana Castro. Castro explicó cómo ella ha “crecido a amar mi tono de piel, quién soy, y lo que representó.”

Aunque muchos argumentan que el colorismo comenzó en tiempos de esclavitud, va más allá de períodos del colonialismo. Dra. Sarah L. Webb, autora y profesora asistente de la Universidad de Illinois, explicó, “Históricamente, aquellos que han tenido poder, y que han sido capaces de obtener y conservar el poder, han tenido una piel más clara, ya sea a través de la ascendencia Europea o siendo un sistema de castas superiores, dependiendo de dónde son” han contribuido al colorismo. Por lo tanto, teniendo un color de piel más clara se ha convertido en un privilegio dentro del propio grupo étnico de una persona.

Dra.Webb dijo que los estudiantes que enfrentan al colorismo, “tienen que estar dispuestos y tener el valor de reconocer lo que les está pasando,” y “estar dispuestos a hacer esa pregunta” de si uno fue elegido para una cierta posición sobre ellos debido a su color de piel, y “sabiendo que la gente va a decir, ‘oh, sólo estás celoso/a,’ o ‘estás siendo divisivo/a,’ o a ‘quién le importa?’”

Junior Jade Alexander dijo que había tenido algunos casos de colorismo en la escuela y cómo, “Ir a una escuela blanca de K al 8 grado de nitivamente in uyó en cómo pensé en mí misma. No fue hasta el séptimo grado cuando me volví completamente segura con mi negrura y el color de mi piel.”

Ella agregó, “Realmente creo que va a tomar un tiempo para que los grupos étnicos acepten su negrura o piel oscura en general.”

“Tu generación tiene la oportunidad de seguir luchando. Cuando los jóvenes entienden cuánto poder tienen para cambiar esa dinámica. Creo que va cambiar aún más,” expresó Bryant.

Hate Is A Virus:

How COVID-19 Has Exacerbated Violence Against Asian Americans

Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in China, the increasing hostility towards Asian Americans has become more apparent than ever. As the virus spreads, so have the narratives of xenophobia and intolerance, with many of the violent incidents concentrated in the Bay Area. Now, the discrimination that many Asian

I feel incredibly torn that Asian communities have a target on their backs because of stereotypes, and especially due to unforeseen and unjusti ed hate as a result of the virus, or possibly due to the previous president’s hatred towards the Chinese because they supposedly ‘started the virus.’

”Americans face is in the spotlight of a national discussion.

e violence targeting Asian Americans has struck fear, anger, and anxiety in many communities throughout the country. Hate crimes against Asian Americans have increased by 70% since the start of the pandemic according to the organization Stop AAPI (Asian Americans and Paci c Islanders) Hate.

Even though the general public has become more aware of the racism that Asian Americans face, this has been an issue for a long time.

Senior Aurelia Gemmet-Young said that her family was one of the many that were a ected by anti-Asian racism in the past. “My family has been here for over a hundred years, and we’ve faced a lot of discrimination at that time. My great-grandma was subject to redlining and eventually evicted out of her home because she was Chinese. Both my grandparents were shamed for their native language and the fact that they didn’t blend with the stereotypical American culture. My grandfather was denied jobs as a direct result of his race. My father was ridiculed in school

and called names because of his race.”

To this day, Gemmet-Young can relate to the some of the same discrimination her family faced. “My heritage and food has been made fun of in school, and I’ve been fetishized for my racial (mixed-race) identity.”

Senior Ben Sakamoto believes that the pandemic ultimately motivated the growing animosity towards AsianAmerican communities. “ ere has been an overwhelming amount of Asian-bias in this country for several years, and stereotypes from the pandemic were just the tipping point, which equates to the extreme rise in Asian hate crimes.”

With the uptick in racially-motivated hate crimes, sophomore Nadia Ruiz said, “I feel very unsafe going out. I worry that if I’m in public, someone will start shouting racial slurs at me because it’s so common now. When I read articles about Asian hate crimes, it makes me feel like I could be next. I also worry about my family, and if they’re unsafe. I worry if my grandparents are no longer safe because of the recent crimes against Asian elders.”

“I think that’s what most Asian Americans struggle with; they don’t want to tell people about some racist experience they had because they think no one will care. Racism against Asians wasn’t brought up as often before the pandemic, so people didn’t normalize talking about it.

”Ruiz said that she feels comforted and validated by others sharing their experiences. “It’s horrible, and what angers me is that some people lack empathy and think it’s okay to do these kinds of things. I just think that more people need to realize that the Asian community could use some help and support.” Ruiz said, “I think that’s what

most Asian Americans struggle with; they don’t want to tell people about some racist experience they had because they think no one will care. Racism against Asians wasn’t brought up as often before the pandemic, so people didn’t normalize talking about it.”

“It just destroys me that people have the intention of hurting Asian communities simply because of stereotypes,” Sakamoto said.

Be aware of what’s happening and take action when you can. Recognize the insidious ways we are discriminated against and ght against it when you can. Amplify our voices and validate our struggles. Stand in solidarity no matter what race or ethnicity you belong to, because these attacks are a result of division and fear. Do not allow racists and terrorists to divide us. We are stronger together.

”Ruiz expressed that the best way to help Asian communities is to “educate people… [and] support Asian-owned companies, donate, or even just check in on friends and family to see if they feel safe. Show them that they have your support, and be willing to listen and learn about their experiences.”

Gemmet-Young concluded, “Be aware of what’s happening and take action when you can. Recognize the insidious ways we are discriminated against and ght against it when you can. Amplify our voices and validate our struggles. Stand in solidarity no matter what race or ethnicity you belong to, because these attacks are a result of division and fear. Do not allow racists and terrorists to divide us. We are stronger together.”

written and designed by Amelia Wu

Super Straight: Bigotry is Trending

written by e Editorial Board designed by Katherine Welander

If you’ve been anywhere near social media, especially TikTok, in the past months, you may have heard of the term “super straight.” In a now deleted video, TikToker Kyle Royce said that “straight men like myself get called transphobic because I wouldn’t date a trans woman.” Royce argues that if he identi es as “super straight,” he can no longer be called transphobic because “that’s just my sexuality.” e term is supposed to apply to someone who identi es as heterosexual but chooses not to date trans and non-binary people. In a trollish attempt to pass o a preference as a sexuality, “super straight” not only undermines the idea of sexual orientation, but also actively discriminates against trans people by making their exclusion the de ning characteristic of their “identity.”

“In a trollish attempt to pass o a preference as a sexuality, ‘super straight’ not only undermines the idea of sexual orientation but also actively discriminates against trans people by making their exclusion the de ning characteristic of their ‘identity.’”

e biggest problem with the idea of “super straight” is that it attempts to pass o a preference as a sexuality. Preferences involve a choice. Preferences are case by

case. And preferences have exceptions. Sexual orientation (broadly) does not. Super straight takes a limited personal preference and turns it into a movement to discriminate against trans people.

Royce’s argument that he is “creating” this new sexuality to protect his own preferences is disingenuous because he advertises it to others by asking his audience “Who else is super straight?” In turn, his “preference” becomes a movement against trans people and encourages people to rally and organize against them.

Labels can bring together those who face similar challenges and can be incredibly helpful to build a sense of community for those who need it most. Confusing that bond with a “preference” makes the struggles LGBTQ+ people face seem trivial. Language and labels are political whether we like it or not.

M-A senior Maeson Linnert, who transitioned about two years ago, said, “Maybe they’re not trying to be outwardly transphobic, but it de nitely comes across that way. Because they’re saying, ‘Hey, we just don’t like trans people.’ You can just say that you don’t have a preference for that type of genitalia. at’s a conversation, but to actively go out and say, ‘I don’t like trans people, and a straight person who dates a trans person is not a true straight,’ that feels really weird and o ensive.”

Linnert explained that when saying, “‘I’m not transphobic it’s just my sexuality,’ you’re cutting out the trans women are women, and trans men are men scenario. You are putting trans people into a separate box just because you’re uncomfortable with them.”

According to a Trevor Project survey about LGBTQ youth mental health, over half of trans or non-binary youth have considered suicide at some point in the last year. is, in part, stems from the alienation and discrimination that the trans community has experienced from all directions for years. In early April, legislators in Arkansas overruled the governor’s veto and passed a law prohibiting gender-a rming treatment for transgender youth. e American Civil Liberties Union says that this year alone, 19 other states have considered similar bills.

“‘You’re

cutting out the whole trans women are women, trans men are men scenario, and you are putting trans people into a separate box just because you’re uncomfortable with them.’”

is problem is not absent locally either. Linnert said that he heard from a friend that “this one guy actively referred to me as an “it” jokingly, behind my back.” He added, “I know people are sometimes uncomfortable with me, especially all girl groups, and sometimes all guy groups generally don’t seem to be as comfortable around me. But I haven’t been directly confronted about it. I’ve never been verbally or physically assaulted for it. So in that case, I’m a bit lucky.”

Labels like “super straight” are part of a larger online trolling community of mostly teenage boys. In 2015 the “Apache Attack Helicopter” joke, which started on Reddit, saw people “coming out” as Apache Attack

Helicopters to make fun of those sharing their gender identities. Gender Studies and history teacher Anne Olson said, “I think that societal expectations of masculinity are also contributing to this. When society has such a rigid and unforgiving de nition of masculinity that is so hard to attain, we have to acknowledge that it in uences and impacts the decisions that people make and how they see themselves.”

Olson explained adolescent boys spearheading these kinds of movements is not new. “It is an old phenomenon that we’re seeing, represented in a new way. When I was in college, it was the phrase ‘feminazis,’ that a lot of adolescent boys and young men would use to describe anybody who connected to the feminist movement. e use of “super straight” is just the newest variation of these reactionary trends.”

“‘When I was in college, it was the phrase ‘feminazis,’ that a lot of adolescent boys and young men would use to describe anybody who connected to the feminist movement.’ e use of ‘super straight’ is just the newest variation of these reactionary trends.’”

e majority of people identifying as super straight, making apache attack helicopter jokes, or identifying with any reactionary anti-LGBTQ+ movement shouldn’t be marked as a bigot for all eternity. But they should be aware of the cruelty behind their words and how

demeaning they are to people. You don’t need to be an expert in gender theory who can delve into the complexities of gender and sexuality, but you should treat others with respect, compassion, and realize that “super straight” makes a joke out of people’s very real struggles.

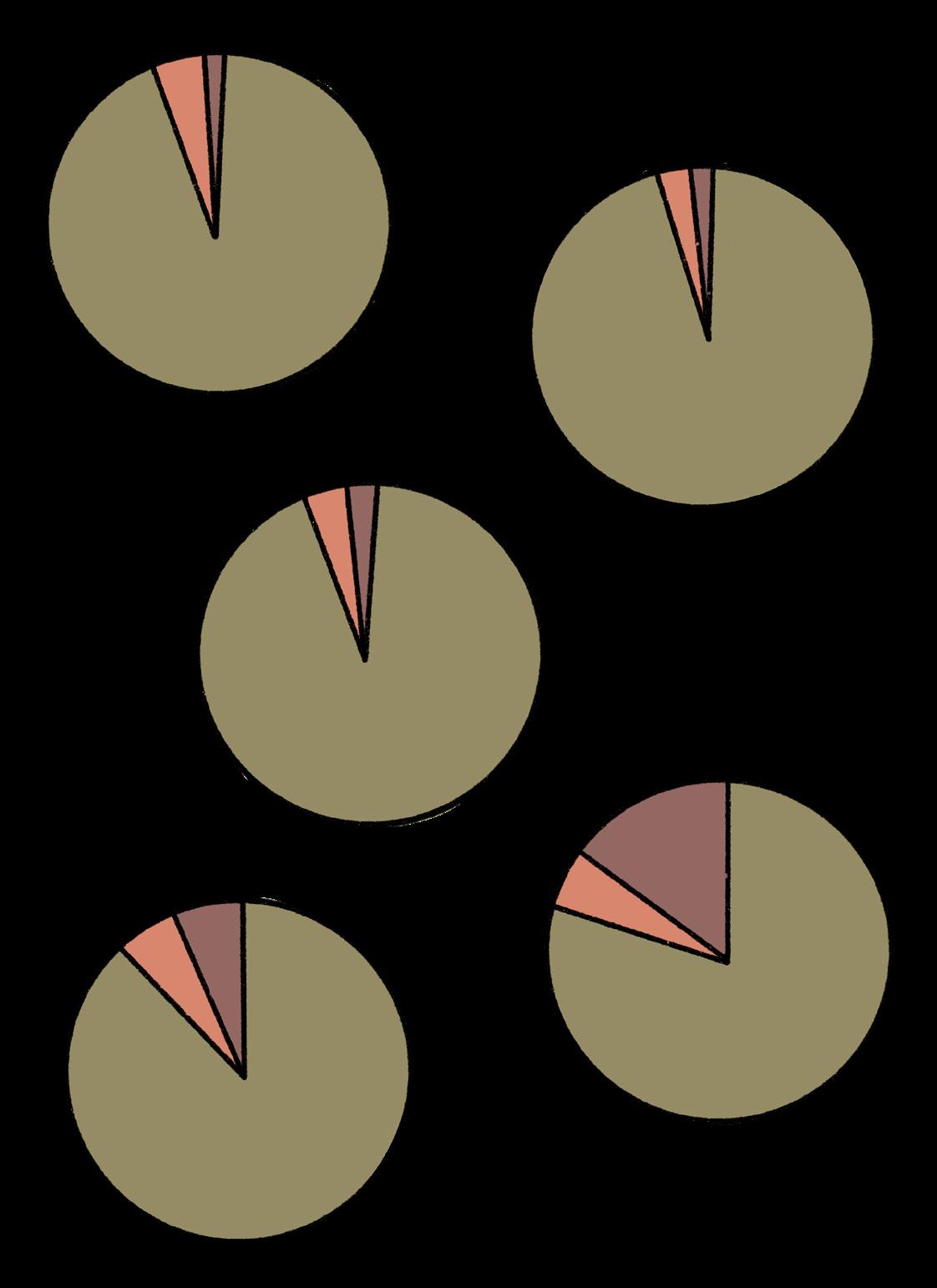

Self-Identification by Generation

Traditionalists (>1946)

Boomers (1946-1964) Generation X (1965-1980) Millenials (1981-1996)

Gen Z (adults) (1997-2002)

Faces M-A

designed by Kari Trail

photographed by Amelia Wu, Isabelle Stid, Christina Mullarkey, and Elinor Kry

Through the Light-Eyed Lens of a Biracial Asian

“But are those really your eyes? ey’re not contacts?”

As a multiracial, naturally light-eyed Asian, I get that a lot. I have my white father’s eyes in my mother’s Chinese face, with dark hair. I am distinctly racially ambiguous; to some I am white, to others I am not, and to too many I am an uncomfortable racial question mark. ere’s this sense that people don’t quite know what to do with me. We like to de ne ourselves, and we especially love to de ne one another in the name of understanding and sharing experiences. We use racial categorizations and labels to make sense of the world, but when someone does not t neatly into one box, the world is unsure of how to respond.

My racial experience is most de ned by a sense of otherness. My identity cannot bring me a sense of belonging. Rather, it leaves me feeling as though I will never belong. When I’m with people of color, I’m the white person, and I need to answer for the sins of every racist, microaggressive white. When I’m with white people, I suddenly become the token minority, the expert on every racial question and experience. No matter where I go, heads will swivel towards me, whenever the “other” racial group (white or BIPOC) is mentioned. Even in a diverse group, I still don’t know which position to take.

I became conscious of my race at a young age, after being constantly asked about it growing up. My parents ensured that I had the right answer; I recall being four years old and fed the mathematical equation that was supposed to de ne me. “You are 50% Chinese, 25% German, 25% Irish,” my dad would say. “And what’s the most important part of that?” “100% American!” I knew to cheer, not knowing how strongly I would doubt it after starting school. is last part was particularly important to my mom because she had immigrated from China. She was always worried about me not tting in with my friends because of my status as a rst-generation American through her. My family’s regular long trips to China, my mother’s insistence on Chinese school every

week, and constant comments from kids at school, all kept me from feeling American. “American” became less of an ethnicity and more of a feeling that can come and go, a belief that changes over time, a fragile notion up for debate by others.

You would think that if I wasn’t quite American, I would then be Chinese. However, in Shanghai, my mother’s hometown, I was not a person but an oddity, more exotic than human.

One of my clearest childhood memories was being at a zoo in China, surrounded by enclosures of exotic animals. A much older stranger approached me, his camera outstretched. Before I could

“In Shanghai, my mother’s hometown, I was not a person but an oddity, more exotic than human.”

say anything, he snapped a photograph. “Your eyes,” he said, by way of explanation and with a smile that made my skin crawl. I stood still, uncomfortable and slightly scared. “Beautiful. And where are your parents from?” Before I could answer, my uncle grabbed me and pulled me away. “Xiansheng, that is a very inappropriate question!” I didn’t understand why it was strange that my father is from America, and my mother from China. Didn’t everyone’s parents have their own countries and hometowns?

After spending the summers of my childhood in China with my mom’s family, I was certain that I looked 100% white, mostly judging by their comments. My mother’s relatives were quick to point out my white features, latching upon anything that set me apart from them.

When I was fourteen, I attended a family reunion in Missouri for my dad’s side of the family. After a lifetime of being told that I looked white, and being fairly naive, I had high hopes for my white family members living in the midwest, somehow

positive that they would recognize me as their own. I recall standing in a sea of blonde hair and fair skin, suddenly conscious of my dark hair and tanned skin. My dad pointed out his cousin and left momentarily. His cousin, unaware of my last name and white half, approached me. “You realize this is the Doran family reunion, right? It’s a private event.” My last name is Doran, but I decided at that moment that I would never t in. I could never truly belong to any group of people, especially not my family. Not only was I humiliated, but I was hurt. When people ask me which race, which side of my family I identify more with, I realize that I don’t feel a sense of belonging to either. My biraciality has led me to constantly contemplate racial questions and identity. Who gets to call themself a person of color? If you’re part white, can you use that label? If a Black and white person is a person of color, is a white and Asian one a person of color? Am I white-passing? Does passing as white every now and again give me white privilege, or is it more accurately described as light-skinned privilege? Is it wrong of me to correct people who assume I’m monoracial? Do I even want to be seen as monoracial? In conversations about race, should I try to listen to other’s experiences, or speak of my own? If the conversation about race is happening in a group of white people, am I obligated to speak and share my experience? If I choose to speak, do I need to give a disclaimer, sorry I’m mixed but...? Do I get to wear the qipao (traditional Mandarin dress) that my Chinese grandparents gave me? How do I respond if someone accuses me of cultural appropriation when I wear a qipao? Is it fair of me to say that I’ve experienced racism when I’m part-white and light-skinned? When I have to check a race box and it only allows me to choose one, which one should I pick?

It is a constant headache, navigating through the world as one who is distinctly other.

My biraciality has made me painfully conscious of every racial encounter and

interaction, as well as where I stand in them. I have spent my life living in dissonance, carrying the weight of dual worlds. And it is exhausting, to never have a racial group to call your own. Having that community is something monoracial people take for granted.

But despite being a racial mis t growing up, I eventually found a community. Other multiracial people are some of the most accepting people I’ve ever met. In a sea of people who largely do not t in with a monoracial group, I nd myself tting in perfectly. I nally feel welcome for who I am in the entirety of my identity, and I cannot say the same of many other communities I’ve been a part of. ere’s this mutual sense of recognition and trust in other’s experiences, as well as how they experience themselves. I can connect with multiracial people in a way that I cannot connect to any of my family, save for my sister.

And for every multiracial person who feels at odds with the world, there’s an acceptance of self that needs to happen outside of a community, although an accepting community can certainly help that process. I grew up speaking two languages (Mandarin Chinese and English) and going back and forth between two countries. Always being seen as an outsider taught me humility and respect in the moments when I was welcomed, it taught me gratitude for the multiracial individuals I’ve connected with, and my sense of self has become stronger through it being challenged. Eventually, I came to realize that I wouldn’t trade my racial identity for anything. Obviously, there’s still discomfort, awkward moments, and comments that are at least a little racist. But I carry within me multiple beautiful cultures, and in the end, I fail to see how this is anything but a gift. I can be both, I can nd ways to celebrate both, even as this concept of “both” causes trouble for me. My eyes are open to more of the world, and for that, I am so grateful.

entomoreof the world,

written by Kai Doran designed by Jane White

Mexican Restaurant Mama Coco Looks Ahead to an Uncertain Future

Enduring a difficult childhood taught owner Omar Piña resilience and perseverance. Now in a global pandemic, he relies on those characteristics more than ever.

written and photographed by Abby Ko designed by Katherine Welander

Mama Coco is just one of many Mexican restaurants in Menlo Park. However, it stands out for its intimacy and unique take on Mexican cuisine. After it opened in 2014, with popular dishes such as empanadas, ceviche de pescado, and queso fundido, the business was an instant hit.

Mr. Piña’s hard work began much earlier than when he rst opened his restaurant. Born in Culiacán, Mexico, and growing up with six other siblings and a single parent, he had to be industrious. He would go to school in the morning, do his homework, and then start working.

“I had my mom, my six siblings, and me,” Mr. Piña said. “But [when] my dad passed away when I was nine years old, my mom had to take care of seven kids by herself. In Mexico you can start to work when you are very little, so I started to work when I was 10 years old. I packaged food for people, and people would give tips to [me].”

“He grew to love what he was doing and ended up serving for eight years in seven different restaurants before starting his own business.”

In 1996, Mr. Piña’s cousin, who had been living in the US for a long time, asked if Piña could come and visit. Mr. Piña was 20 and still in college at the time. When he did end up visiting, he loved the weather. After talking about it with his mother, he moved to Palo Alto and started working as a server at restaurants such as Left Bank and Flea Street Cafe. He grew to love what he was doing and ended up serving for eight years in seven di erent restaurants before starting his own business.

Piña rst thought of opening a restaurant when managers at another restaurant suggested he should. He was skeptical about it at rst, but he soon realized that it was a great opportunity.

“I wanted to open a restaurant where I worked for myself and not someone else,” Mr. Piña explained. “I wanted to make the food that we made in Mexico, too. So I wanted to bring that here and show you my experience.”

Mr. Piña opened his restaurant, Mama Coco, in 2014.

“I was so happy,” he recalls. “I was so proud to do business by myself.”

Since then, Mama Coco has been a hit, garnering great reviews from restaurant critics and loyal customers alike.

One customer wrote that he is a regular at Mama Coco, and chose the restaurant for his anniversary dinner. He said, “You don’t nd many places in Menlo Park that you can visit for both lunch and an elegant dinner.”

Another customer said, “ e food was incredibly good and brought a smile to our face during these trying times.”

ey explained that the sta even provided “a personal note letting us know they appreciated our business.”

“‘I cannot recommend their enchiladas with more enthusiasm. The staff is wonderful, and the owner really cares about the quality of the food and the experience.’”

A third yelp review of Mama Coco reads, “I cannot recommend their enchiladas with more enthusiasm. e sta is wonderful, and the owner really cares about the quality of the food and the experience.”

In fact, Mr. Piña has plans to open a second location. “Otherwise, it will start to feel boring, doing the same stu all of my life… at is why I want to open another one and try to open as many restaurants as I can.”

Mr. Piña’s success hasn’t come without challenges. Menlo Park has become increasingly expensive as rent and employee salaries are becoming more of a worry for him.

“[ e employees] make maybe 18-19 dollars an hour, and it’s hard to pay 3,500 dollars for two bedrooms,” he said.

Mama Coco has struggled just like many other local businesses. Mr. Piña remarked that they do very little outdoor dining and a lot of take-out. He also outlined all of the safety measures they are now taking.

“I want to make sure that our customers are healthy,” he said. “We make sure [our employees] are in good condition and we check our temperatures.”

Even with these issues, Mr. Piña embodies perseverance. “I know I can do it. It’s going to be hard in the beginning, but I know I can do it.”

Sonic Showdown Albums Playlists

Purple Rain, To Pimp a Butter y, Lemonade, Blonde, Ctrl: What do all these names have in common? If you guessed iconic, genre-bending albums from the twentieth century and beyond, then you’d be correct. What, then, makes them so memorable—is it their impressive vocals, attention to detail, sound-mixing, impeccable pacing, or political relevance? Ultimately, it’s a combination of multiple elements, a pattern that has time-and-time again proven the importance of the album as a device for social commentary and thematic exploration.

And yet, despite the timeless quality of our favorite albums, a cultural shift seems to be brewing underway alongside the rise in music streaming: playlists. A new study shows that 40% of modern music listeners opt for playlists over albums. While playlists may grant an individual more freedom over their listening experience, albums often take the form of a treasure hunt. It’s a classic game of risk or reward—you risk the chance of boredom in the hopes of nding that one hidden gem, buried within the mix. Playlists are safe; albums are an adventure.

Besides, playlists–by their very nature–are meant to be forgettable. We add songs, listen to them a whole week straight, and gradually lose interest as our taste expands. Personally, I only end up using old playlists a few years later in retrospect, looking back on (and often laughing at) the songs I listened to during a certain period in time. Some playlists don’t even receive that honor (RIP to my “Summer 2018” playlist that consisted 99% of Rex Orange County songs, you will not be missed).

Albums, on the other hand, are timeless. ey create a cohesive listening experience for the audience, sonically crafting a world for the listener to enter and absorb. e time an artist puts into the organization and theme of their album will always outdo the half-hearted spontaneity of playlist-making.

It would be, however, an incomplete ode to albums without mentioning the brilliant magic of album sequencing. A blend of intricate fade-ins, balanced pacing,

vs

and thematic mixing, sequencing establishes a cohesion between the individual songs, allowing the album to feel like a collective body of work. As one music guide puts it, “Sequencing de nes the relationship between each song. Without good sequencing, your album is just another playlist.” To that point, the best albums convey a sense of narrative, oftentimes establishing an introduction, climax, and conclusion along the way. Good albums include songs that revolve around a speci c theme; great albums utilize sequencing to add the cherry on top.

Frank Ocean’s studio debut Channel Orange sprinkles sound e ects like static, channel sur ng, and mu ed chatter in between songs, e ectively stringing together a diverse tracklist with an overarching cinematic motif. He even went to the extent to add jazzy commercial breaks and jingles throughout the album, re ecting on the fastpaced culture of love and passion in modern society. Taking a similar approach, Solange’s critically acclaimed A Seat at the Table uses seamless fade-ins and fade-outs between tracks, languidly drifting through the songs without disruption. is uidity is speci c to the album experience—it’s incredible to enter a world that expands throughout the course of multiple tracks and, ideally, makes a point by the time you leave.

Moreover, albums have historically been devices for changing social dialogues or the conventions of the music industry. Take, for example, e Beatles’ Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band (1967), one of the rst successful “concept albums” where a single theme uni es the recording as a whole. In this case, the Beatles imagined themselves as a ctitious band, performing a series of eccentric live performances. Or consider Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On (1971), an album that meshed counterculture themes with lyrical falsetto. e Guardian even expressed that Gaye’s eleventh studio album

“ushered in an era of socially aware soul” with a “disillusioned nobility [that] caught the public mood.” As much as an album might wrestle with themes speci c to an artist’s experiences, they can often re ect the times, acting as a testament to the norms, politics, or expectations prevalent within a society’s given era. In this way, a good album can play time-machine, transporting the listener into whatever time period they choose. If escapism is the intention of music–as it is to many of us–then albums e ectively serve that purpose. Feeling wistfully nostalgic? Try Feel Like Makin’ Love by Roberta Flack. Want to enter an Afro Futuristic sonic landscape? e Black Panther soundtrack will do the trick.

at’s not to say playlists can’t be touching or meaningful—I, an avid album enthusiast, often nd myself reaching for my seventeen hour-long playlist of down-toearth indie and funky neo-soul tunes. But when it comes to artistic intention, thematic exploration, and social commentary, albums are always worth your time.

written by Kari Trail

highlights the complexities of the individual.

My two current favorite artists are Phoebe Bridgers (CEO of sadness) and Doja Cat (rapping queen). ough they are on opposite sides of the musical spectrum, I need a combination of their songs to keep me at my best. Listening to an entire Phoebe Bridgers album induces sobbing, and listening to a complete Doja Cat album makes me feel like I’ve shotgunned a hundred energy drinks. A playlist is necessary to balance the vibes out.

While listening to an album can be a breathtaking experience, its intended cohesion o en causes the songs to blend into each other, making it di cult to appreciate their individual greatness.

Listening to others’ playlists gives me the chance to test the musical waters and explore which songs and genres I prefer. ese playlists contain a mesh of whatever musical classi cation you choose and give you direct access to an artist’s most likeable songs, rather than forcing you to weed out the songs you dislike in an album. When in search of new music, I typically use Spotify playlists like Lorem or Indie Pop. Each of these has gi ed me with playlist-worthy songs from artists I typically don’t listen to, like Clubhouse (carefree, bubblegum pop) and Olivia Rodrigo (angsty teenage girl ballads).

My favorite aspect of a playlist is how the ones you make become uniquely yours. Since the start of middle school, I’ve

Spotify and Apple Music allow you to share your playlists with friends, which is not only super convenient for shared musical experiences, but also gives you insight into your friends’ musical tastes. I’ve stalkingly found the playlists of the people I’m interested in and even picked up some new favorite songs from my friends’ accounts, like “Big Toe” and “Dope on a Rope”—both beach goth hits by the Growlers. Playing these songs on my playlist while we are together helps us to celebrate our common taste, but also makes me proud of the perfection that is my personal playlist.

Playlists also capture the mood of a room much more accurately than an album would. My friends and I have wildly di erent tastes, but we are still able to enjoy the music we listen to together because it o en comes from a playlist where we’ve designated songs we all like. On our two a.m. Taco Bell eld trips, we scream our favorite throwbacks together at the top of our lungs, like “God’s Plan” by Drake, famous Canadian.

While albums are polished, personalizing your musical tastes blesses you with the power of choice. Making a re playlist is the closest you’ll ever feel to being a god.

written by Jane White designed and illustrated by Kari Trail

Bear Territory

M-A Sports Return to the Turf

by

designed

Kari Trail

photographed by Bob Dahlberg

ReMARKable Seniors

Sathvik Nori

Violet Taylor

Izzy Leake

Cole Trigg

Brynn Baker

Amelia Wu

Chloe Hsy

David Wagstaff

Kai Doran

Ashley Trail

Kari Trail

Ally Mediratta

Emily Xi

Triana Devaux

designed by Jane White

photographed by Cole Trigg

designed by Chloe Hsy